Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a highly prevalent disorder leading to heart failure, stroke, and death. Enhanced understanding of modifiable risk factors may yield opportunities for prevention. The risk of AF is increased in subclinical hyperthyroidism, but it is uncertain whether variations in thyroid function within the normal range or subclinical hypothyroidism are also associated with AF.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and obtained individual participant data from prospective cohort studies that measured thyroid function at baseline and assessed incident AF. Studies were identified from MEDLINE and EMBASE databases from inception to July 27, 2016. The euthyroid state was defined as thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) 0.45–4.49mIU/l, and subclinical hypothyroidism as TSH 4.5–19.9mIU/l with free thyroxine (fT4) levels within reference range. The association of TSH levels in the euthyroid and subclinical hypothyroid range with incident AF was examined using Cox proportional hazards models. In euthyroid participants, we additionally examined the association between fT4 levels and incident AF.

Results

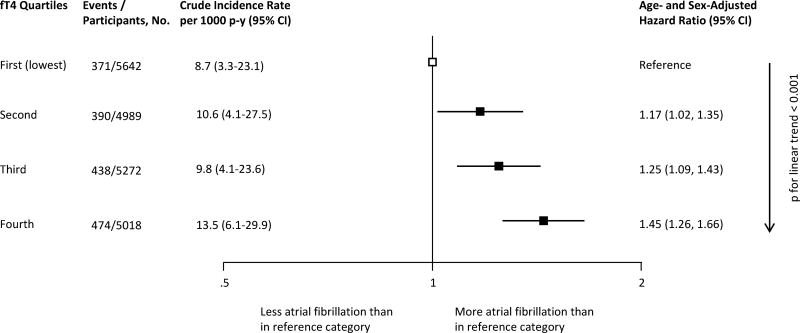

Of 30,085 participants from 11 cohorts (278,955 person-years of follow-up), 1,958 (6.5%) had subclinical hypothyroidism, and 2,574 individuals (8.6%) developed AF during follow-up. TSH at baseline was not significantly associated with incident AF in euthyroid participants or those with subclinical hypothyroidism. Higher fT4 levels at baseline in euthyroid individuals were associated with increased AF risk in age- and sex-adjusted analyses (hazard ratio=1.45; 95% confidence interval, 1.26–1.66, for the highest quartile vs the lowest quartile of fT4, p for trend ≤0.001 across quartiles). Estimates did not substantially differ after further adjustment for preexisting cardiovascular disease.

Conclusion

In euthyroid individuals, higher circulating fT4 levels, but not TSH levels, are associated with increased risk of incident AF.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, subclinical hypothyroidism, thyroid stimulating hormone, free thyroxine

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) affects more than 30 million individuals worldwide, and its prevalence and incidence is increasing globally.1 AF leads to significant morbidity and mortality,2 and increases the risk of stroke, heart failure, and subsequent hospitalizations.3 Identification of modifiable risk factors and potentially reversible causes is crucial for prevention and treatment of AF. Overt hyperthyroidism is a recognized risk factor for AF,4 and measurement of thyroid function is recommended in the initial evaluation of patients with AF.5 Subclinical thyroid dysfunction, which is defined as abnormal thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels with free thyroid hormone concentrations within the reference range, is common, with up to 9% of the adult population being affected by subclinical hypothyroidism and 2–3% by subclinical hyperthyroidism.6, 7 The risk of AF is increased in subclinical hyperthyroidism, especially when TSH levels are lower than 0.10mIU/l.8, 9

Subclinical hypothyroidism increases the risk of cardiovascular events,10 but its association with incident AF risk remains uncertain.9, 11–13 Variations in thyroid hormone levels within the reference range have been associated with adverse cardiac events, and recent studies have suggested that higher free thyroxine (fT4) levels lead to an increased risk of heart failure and sudden cardiac death in euthyroid individuals.14, 15 Data from observational studies on the association between thyroid function within the reference range and the incidence of AF are conflicting.11, 16, 17

Therefore, we aimed to examine the risk of AF in individuals with thyroid function within the normal range and subclinical hypothyroidism by performing an individual participant data (IPD) analysis of prospective cohort studies. An IPD analysis might help clarify the conflicting results of previous studies; it is considered the methodological gold-standard for summarizing evidence from observational studies and to analyze the impact of age, sex, and thyroid medication in subgroup analyses, as it is not affected by potential aggregation bias from study-level meta-analyses (ecological fallacy).18, 19 This approach allows also a uniform definition of thyroid function and adjustments of similar confounders with the aim of reducing heterogeneity across studies.

Methods

This IPD analysis was conducted according to the predefined protocol registered on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42016043906). Reporting conformed to the PRISMA-IPD statement.20

Data Sources and Study Selection

We conducted a systematic literature review of published articles in the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases, from inception to July 27, 2016, on the association between TSH and AF events, without language restriction (Supplemental Methods 1). We also performed a manual literature search, in which we reviewed expert papers in the field, screened bibliographies from retrieved articles, and requested data from cohorts participating in the Thyroid Studies Collaboration.8, 10, 21, 22 Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to improve comparability and quality of the studies. We included only full-text published longitudinal cohort studies that assessed thyroid function at baseline (serum TSH and fT4), and that had a euthyroid control group and prospective follow-up of AF events. We excluded studies that included only participants with overt thyroid dysfunction (abnormal TSH and fT4 levels), only participants that took thyroid-altering medications (anti-thyroid drugs, thyroxine, or amiodarone), or that assessed only postoperative AF events. Two authors (C.B. and C.F.) independently screened references for eligibility; discrepancies were resolved in consultation with a third author (N.R.). Agreement between reviewers was 98.6% for first screening phase (titles and abstracts, kappa= 0.66), and 95.0% for the second screening phase (full-text screen, kappa=0.83).

Two authors (C.B. and C.F.) rated the methodological quality of the included studies based on individual criteria of the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (Supplemental Methods 2).23

Institutional review boards approved all studies, and written informed consent was granted by all participants. The sponsors had no role in the design, analysis or reporting of the study.

Data Extraction

We contacted investigators from included studies and requested prespecified IPD on baseline thyroid function (TSH and fT4), demographic characteristics (age, sex, race), cardiovascular and AF risk factors (blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, total cholesterol, smoking), preexisting cardiovascular disease, history of AF, and medication use at baseline (thyroid-altering medications including thyroxine, anti-thyroid medication, lithium, amiodarone, glucocorticoids, iodine, aspirin, furosemide; cardiovascular medications such as antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs) for each participant (see Supplemental Table 1 for definition of baseline covariates in the included studies). Data on AF outcomes were collected. We checked data for consistency and completeness, excluded unrealistic data points, and contacted authors of the cohorts to clarify variable definitions. For two studies for which authors could not share IPD (one cohort due to legal constraints,24 and another one9 due to prohibitive costs; Table 1), we looked for published aggregate data on the association between thyroid function and AF, so we could perform sensitivity analyses that included these studies.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Study | Description of Study Sample |

No. * | Age, Median (Range), y † |

Women, No. (%) |

Cardio- vascular Disease, No. (%) ‡ |

Endogenous Subclinical Hypo- thyroidism, No. (%) § |

Medication Users during Follow-up, No. (%)‖ |

Follow-up # | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Thyroxine | Anti- thyroid medication |

Start, y | Duration, Median (IQR), y |

Person- Years |

AF events, No. (%) |

|||||||

| United States | ||||||||||||

| Cardiovascular Health Study13 | Community-dwelling adults with Medicare eligibility in 4 US communities | 3,328 | 73 (64–98) | 1917 (57.6) | 845 (25.4) | 436 (13.1) | 308 (9.5) | NA | 1994–1995 | 11.7 (7.0–18.1) | 32,632 | 886 (26.6) |

| Health ABC Study25 | Community-dwelling adults with Medicare eligibility in 2 US communities | 2,346 | 74 (69–81) | 1143 (48.7) | 625 (27.1) | 270 (11.5) | 114 (4.9) | 2 (0.1) | 1997 | 8.1 (7.4–8.3) | 16,155 | 201 (8.6) |

| Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study26 | Community-dwelling men aged 65 years or older in 6 US clinical centers | 678 | 72 (65–91) | 0 | 135 (19.9) | 45 (6.6) | 18 (2.7) | 0 | 2000–2002 | 12.6 (11.2–13.1) | 7,668 | 62 (9.1) |

| Europe | ||||||||||||

| Bari Study27 | Outpatients with heart failure followed up by Cardiology Department in Bari, Italy | 268 | 65 (21–92) | 55 (20.5) | 103 (38.4) | 23 (8.6) | 22 (8.2) | 8 (3.0) | 2006–2008 | 1.3 (0.6–1.9) | 339 | 14 (5.2) |

| Leiden 85-plus Study28 | All adults aged 85 years living in Leiden, the Netherlands | 432 | 85 (85–85) | 281 (65.1%) | 166 (38.4) | 27 (6.3) | 5 (1.2) | 3 (0.7) | 1997–1999 | 5.5 (2.7–9.0) | 1,575 | 44 (10.2) |

| SHIP29** | Adults living in Western Pomerania, Germany | 2,339 | 45 (20–85) | 1191 (50.9) | 100 (4.3) | 12 (0.5) | 172 (7.4) | 8 (0.3) | 1997–2001 | 11.5 (11.1–12.1) | 22,006 | 40 (1.7) |

| InChianti Study30 | Community-dwelling adults aged 65 years or older living in Tuscany, Italy | 1,051 | 71 (21–103) | 581 (55.3) | 123 (11.7) | 26 (2.5) | 17 (1.6) | 2 (0.2) | 1998 | 9.0 (8.3–9.2) | 8,453 | 14 (1.3) |

| Rotterdam Study16 | Inhabitants of Ommoord (The Netherlands) aged ≥ 55 years | 1,607 | 68 (55–93) | 975 (60.7) | 412 (25.6) | 91 (5.7) | NA | NA | 1990–1993 | 15.5 (11.4–16.9) | 20,892 | 226 (14.1) |

| PROSPER Study31 | Community-dwelling elderly with high cardiovascular risk in The Netherlands, Scotland and Ireland | 5,334 | 74 (69–83) | 2,645 (49.6) | 2,356 (44.2) | 384 (7.2) | 57 (1.1) | 11 (0.2) | 1997–1999 | 3.3 (3.0–3.5) | 16,529 | 496 (9.3) |

| EPIC-Norfolk Study32 | Adults aged 40 to 79 years living in Norfolk, England | 11,642 | 58 (39–78) | 6,181 (53.1) | 442 (3.8) | 607 (5.2) | NA | NA | 1995–1998 | 17.0 (16.1–18.0) | 137,861 | 575 (4.9) |

| Australia | ||||||||||||

| Busselton Health Study33 | Adults living in Busselton, Western Australia | 1,060 | 46 (18–81) | 539 (50.9) | 54 (5.1) | 37 (3.5) | 20 (1.9) | 1 (0.1) | 1981 | 14.0 (14.0–14.0) | 14,840 | 16 (1.5) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Overall | 11 Cohorts | 30,085 | 69 (18–103) | 15,508 (51.6) | 5,371 (17.9) | 1,958 (6.5) | 733 (2.4) | 35 (0.1) | 1981–2008 | 16.6 (10.7–18.7) | 278,955 | 2,574 (8.6) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Studies where IPD were not available | ||||||||||||

| Framingham Heart Study9 | Adults aged ≥ 60 years from Framingham, USA | 1,759†† | ≥ 60 (NA) | 1037 (59.0) | NA | 183 (10.4) | NA | NA | 1978–1980 | 10.0 (NA) | NA | 156 (8.9) |

| Rotterdam Study Cohorts I, II and III24‡‡ | Adults aged ≥ 55 years for Cohort II and ≥ 45 years for Cohort III from Ommoord, The Netherlands | 8,740 | 63 (45–105) | 5010 (57.3) | NA | 722 (8.3) | NA | NA | 2000–2001 Cohort II, 2006–2008 Cohort III | 6.8 (3.9–10.9) | 61,935 | 403 (4.6) |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation of Cancer; Health ABC Study, Health Aging and Body Composition Study; InChianti, Invecchiare in Chianti; IPD, individual participant data; IQR, Interquartile Range (25th–75th percentiles); NA, Data not Available; PROSPER, Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk; SHIP, Study of Health in Pomerania; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; y, Years

We excluded from our analyses participants with prevalent atrial fibrillation at baseline, missing outcomes for atrial fibrillation, subclinical hyperthyroidism and overt thyroid dysfunction, and intake of thyroxine or antithyroid medication at baseline.

We excluded participants younger than 18 years.

Cardiovascular disease at baseline was defined as known history of stroke, transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, coronary angioplasty, or bypass surgery.

We used a common definition of subclinical hypothyroidism, TSH 4.5 mIU/L to 19.9mIU/L and normal free thyroxine level, but TSH cutoff values varied among the previous reports from each cohort, so numbers are different than in the original articles. To analyze only endogenous subclinical hypothyroidism, we excluded 253 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study, 207 in the Health ABC Study, 43 in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study, 15 in the Bari study, 12 in the Leiden 85+ study, 107 in the Study of Health in Pomerania, 21 in the Invecchiare in Chianti Study, 26 in the Rotterdam study, 188 in the PROSPER study, 301 in the EPIC-Norfolk study, and 4 in the Busselton Health study because they used thyroid medication at baseline.

We had no data on thyroid medication use during follow-up for 481 participants in the Study of Health in Pomerania, and all participants in the EPIC-Norfolk and the Rotterdam study. 91 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study did not have information on thyroxin during follow-up, and information on antithyroid medication during follow-up was missing for all patients of the Cardiovascular Health Study. 5 persons took both thyroxine and anti-thyroid medication during the course of follow-up.

For all cohorts, we used the maximal follow-up data that were available, which may differ from previous reports of some cohorts. For the Cardiovascular Health Study, we set the baseline for our analysis to the year 5 visit of the original cohort because free thyroxine was measured at the year 5 visit.

SHIP includes participants from Pomerania, where an iodine supplementation program began in the mid-1990s. This shifted the distribution of TSH values towards the left in its first years, which lowered TSH values in the population of the SHIP Study during baseline examinations in 1997–2001.

Number of participants with euthyroidism and subclinical hypothyroidism. Participants with subclinical hyperthyroidism are not listed here, since they were not included in our sensitivity analysis or in the aggregate data from this cohort.

Data on characteristics of 8740 participants included in the longitudinal analysis by Chaker et al.24 was obtained through contact with the authors. Individual participant data of 1,602 participants was available for Rotterdam Study Cohort I (see above).

Thyroid Function Testing

In line with our previous analyses8, 10, 21 and based on an expert consensus meeting of the Thyroid Studies Collaboration (International Thyroid Conference, Paris, France, 2010), expert reviews,34, 35 and previous large cohorts,13, 36 we used uniform cutoff levels of TSH to define thyroid dysfunction and optimize the comparability of the included studies. Similar to previous studies, euthyroidism was defined as a TSH level from 0.45 to 4.49mIU/L and further subdivided into five categories: 0.45–0.99mIU/l; 1.00–1.49mIU/l; 1.50–2.49mIU/l; 2.50–3.49mIU/l; and 3.50–4.49mIU/l.37

Subclinical hypothyroidism was defined as a TSH level between 4.5–19.9mIU/L with fT4 levels in the reference range, and was further subdivided into subclinical hypothyroidism with mildly elevated TSH 4.50–6.9mU/l, moderately elevated TSH 7.0–9.9mIU/l, and markedly elevated TSH 10.0–19.9mIU/l.10 In some cohorts, we also included participants with missing fT4 measurements and a TSH within the range for subclinical hypothyroidism in the main analyses (Table 2), because most people with TSH levels in this range have subclinical rather than overt thyroid dysfunction.7 We performed a sensitivity analysis, with exclusion of individuals with missing fT4 values.

Table 2.

Definition of Subclinical Hypothyroidism and Atrial Fibrillation Events

| Study | Cohort TSH and fT4 Reference Range |

Definition of Subclinical Hypothyroidism in IPD Analysis | AF Events – Methods of Ascertainment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| United States | |||

| Cardiovascular Health Study | TSH 0.45–4.50 mIU/L, fT4 9–22 pmol/L | TSH ≥4.5 mIU/L & TSH <20mIU/L, normal fT4 0.7–1.7 ng/dL (9–22 pmol/L) or missing fT4 (0/436, 0%) | Self-report, annual ECGs, ICD-9 coded AF on hospital discharge |

| Health ABC Study | TSH 0.1–4.4 mIU/L, fT4 10.3–23.2 pmol/L | TSH ≥4.5 mIU/L & TSH <20mIU/L, normal fT4 0.8–1.8 ng/dL (10.3–23.2 pmol/L) or missing fT4 (195/270, 72%) * | Minnesota-coded ECGs at baseline and at year 4 follow-up, ICD-9 coded ambulatory and inpatient AF diagnoses from CMS data |

| Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study | TSH 0.55–4.78 mIU/L, fT4 9–24 pmol/L | TSH ≥4.5 mIU/L & TSH <20mIU/L, normal fT4 0.7–1.85ng/dL (9–24pmol/L) or missing fT4 (0/46, 0%) | ECG at baseline, self-report, AF diagnoses from medical records every 4 months |

| Europe | |||

| Bari Study | TSH 0.35–5.50 mIU/L, fT4 9–23.2 pmol/L | TSH ≥4.5 mIU/L & TSH <20mIU/L, normal FT4 0.7–1.8 ng/dL (9–23.2 pmol/L) or missing fT4 (0/23, 0%) | ICD-9 coded AF on hospital discharge |

| Leiden 85+ Study | TSH 0.3–4.8 mIU/L, fT4 13–23 pmol/L | TSH ≥4.5 mIU/L & TSH <20mIU/L, normal fT4 1.0–1.8ng/dL (13–23 pmol/L) or missing fT4 (1/27, 3.7%) | Minnesota-coded annual ECGs |

| Study of Health in Pomerania | TSH 0.25–2.12 mIU/L, fT4 8.3–18.9 pmol/L | TSH ≥4.5 mIU/L & TSH <20mIU/L, normal fT4 0.64–1.47ng/dL (8.3–18.9 pmol/L) or missing fT4 (0/12, 0%) | Minnesota-coded ECGs at baseline, year 5 and year 10 follow-up |

| Invecchiare in Chianti Study | TSH 0.46–4.68 mIU/l, fT4 9.9–28.2 pmol/L | TSH ≥4.5 mIU/L & TSH <20mIU/L, normal fT4 0.77–2.19ng/dL (9.9–28.2pmol/L) or missing fT4 (0/26, 0%) | ECGs at baseline, 3 year, 6 year and 9 year follow-up |

| Rotterdam Study | TSH 0.4–4.0 mIU/L, fT4 11–25 pmol/L | TSH ≥4.5 mIU/L & TSH <20mIU/L, normal fT4 0.9–1.9ng/dL (11–25pmol/L) or missing fT4 (29/91, 31.9%) | ECGs at baseline, year 2 and year 7 follow-up, ICD-10 coded AF diagnoses from GP records and hospital discharge |

| PROSPER Study | TSH 0.45–4.50 mIU/L, fT4 12–18 pmol/L | TSH ≥4.5 mIU/L & TSH <20mIU/L, normal fT4 0.9–1.4 ng/dL (12–18pmol/L) or missing fT4 (211/384, 54.9%) † | Minnesota-coded annual ECGs |

| EPIC-Norfolk | TSH 0.4–4.0 mIU/L, fT4 9–20 pmol/L | TSH ≥4.5 mIU/L & TSH <20mIU/L, normal fT4 0.7–1.6ng/dL (9–20 pmol/L) or missing fT4 (0/607, 0%) | Self reported intake of drugs used for AF treatment at baseline (digitalis and VKAs), ICD-10 coded AF on hospital discharge |

| Australia | |||

| Busselton Health Study | TSH 0.4–4.0 mIU/L, fT4 9–23 pmol/L | TSH ≥4.5 mIU/L & TSH <20mIU/L, normal fT4 0.7–1.8ng/dL (9–23 pmol/L) or missing fT4 (1/ 37, 2.7%) | Minnesota-coded ECGs at baseline and at year 14 follow-up |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; ECG, electrocardiogram; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation of Cancer; fT4, free thyroxine; GP, general practitioner; ICD, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; IPD, individual participant data; PROSPER, Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone, VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

fT4 was measured only in participants with TSH ≥ 7.0 mIU/L or TSH in this cohort

fT4 was measured only in participants with TSH ≥4.5mIU/l in this cohort

Study-specific cut-offs were used for fT4 (Table 2) because intermethod variation is greater for these measurements than in TSH assays;10 participants were categorized in fT4 quartiles.

We excluded those with overt thyroid dysfunction or thyroid hormone values that suggested non-thyroidal illness (low TSH and fT4 levels) or subclinical hyperthyroidism, as we have already published these results (this previous publication was based on a smaller number of studies, as new data became available since its publication in 2012).8 To restrict our analysis to patients with endogenous values of thyroid function, participants on thyroid medication (thyroxine, anti-thyroid medication) at baseline were excluded (Supplemental Figure 1), while those initiating thyroid medications during follow-up were included in the main analyses.8 Additional sensitivity analyses excluding users of thyroid medication during follow-up were performed.

Outcomes

The outcome was incident AF; participants with pre-existing AF at baseline were excluded from all analyses. The ascertainment of AF included electrocardiograms (ECG) during follow-up (9 studies), self-report, diagnostic codes, and review of medical records depending on the cohorts (Table 2). As AF ascertainment by self-report and review of medical records might be less specific, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding studies with AF diagnosis without ECG review. Any type of AF (paroxysmal, persistent, permanent) was considered.

Statistical Analyses

Differences in baseline characteristics of participants with euthyroidism and those with subclinical hypothyroidism were compared using a chi-squared test or Student’s t-test, as appropriate. Crude incidence rates for AF per 1000 person-years were calculated using an inverse variance random-effects meta-analysis of log incidence rates, and point estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were exponentiated to obtain the incidence rates. An IPD analysis was conducted using a one-step approach.18 A Cox proportional hazard regression analysis using random-effects (shared-frailty) by cohort was used to describe the association between incident AF and TSH or fT4.38 The proportional hazards assumption was met. For the analysis with TSH as the explanatory variable, euthyroid participants within the TSH category from 3.50–4.49mIU/l were used as the reference group. The reference group was chosen according to the assumption of a S-shaped association between TSH and the risk of AF based on previous findings.11, 14 All TSH categories were analyzed in a single model. Following the recent publications of studies indicating an association between fT4 levels in the reference range and major adverse events including AF14, 24 and stroke,22 we also conducted a secondary analysis (not prespecified in the study protocol) of the association between fT4 in the euthyroid range and AF; study-specific quartiles of fT4 were computed, and the lowest fT4 quartile was the reference group. Only participants with both TSH and fT4 levels within the reference range were included in the secondary analysis.

The main analyses of both the association between TSH or fT4 and incidence of AF were adjusted for age and sex.10 In a following step, additional adjustment was done for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, including systolic blood pressure, current or former smoking, diabetes mellitus, total cholesterol and prevalent cardiovascular disease (multivariable adjusted analysis); as some of these risk factors might be mediators in the relationship between thyroid hormones and incidence of AF, the age- and sex-adjusted model was considered the main analysis. Whenever there was an indication of a linear association, we calculated p for linear trend for the main and multivariable adjusted analysis. Because data were not available in all cohorts, we also performed sensitivity analyses additionally adjusted for 1) antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medication and 2) body mass index. Additional sensitivity analyses 3) included all individuals regardless of intake of thyroid medication (thyroxine or anti-thyroid medication), so participants with thyroid medication use at baseline were added to this sensitivity analysis, 4) excluded participants who took amiodarone at baseline (or studies which did not provide this information), 5) excluded participants who took any other medications that might alter thyroid function (amiodarone, lithium, glucocorticoids, iodine, aspirin, furosemide) at baseline, 6) excluded those having received thyroid medication during follow-up (or studies that did not provide this information), 7) excluded studies in which no ECGs were used to diagnose AF, 8) excluded studies with >5% lost to follow-up, and 9) excluded a study that tested thyroid function an average of 3.4 years before incident AF was first assessed.26 For analyses of the association between TSH levels and the risk of AF, we also performed sensitivity analyses that 10) excluded participants whose fT4 measurements were missing, 11) were restricted to individuals with persistent thyroid function state, i.e. included only those with thyroid function measurements that remained in the same category (euthyroidism or subclinical hypothyroidism) during follow-up thyroid function testing, and 12) excluded a study29 conducted in a region where an iodine supplementation program was initiated a few years before the study was started, leading to a shift of TSH values towards lower levels in this population during the baseline examination.39 All sensitivity analyses were prespecified in our protocol, with the exception of 4), 9), 11), and 12).

To examine potential sources of heterogeneity, we conducted predefined subgroup analyses similar to those in our previous studies,8, 10 which considered age, sex, race, the prevalence of cardiovascular disease. In an additional analysis, individuals with thyroxine use at baseline were included and a subgroup analysis stratified on thyroxine use at baseline was performed. P-values to test for interaction in the subgroup analyses were derived from Wald tests.

We analyzed the association between continuous concentrations of TSH or fT4 and AF. For the association between TSH and AF, a 4-knot restricted cubic spline was used with knots at TSH levels of 1.0mIU/l, 2.5mIU/l, 4.5mIU/l, and 10mIU/l, to represent three categories within the reference TSH range, as well as categories of subclinical hypothyroidism with mild to moderately elevated TSH and markedly elevated TSH levels.10 Hazard ratios were compared to a reference value of 3.5mIU/l, according to the lower bound of the cut-off used for our reference category. For the association between continuous concentrations of fT4 within the reference range and AF, we expressed fT4 in standard deviation units centered around the mean to make fT4 values comparable across studies. For this analysis, we used a 1-knot restricted cubic spline with the knot placed at the median value of fT4 in standard deviation units, which resulted in the best model fit. Spline regression analyses were adjusted for age and sex. We calculated a p for non-linear trend using a likelihood ratio test comparing the models with and without the TSH or fT4 splines, respectively. This analysis was not prespecified in our protocol. Statistical significance was tested two-sided and p-values <0.05 were judged significant. We used inverse variance random-effects meta-analysis to combine the summary estimates of our IPD analysis with results from two studies that provided only aggregate data. We used a funnel plot to assess for potential publication bias of the association between fT4 levels within the reference range and the risk of AF, considering the estimates of the highest quartile of fT4 compared to the lowest quartile. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.1 (StataCorp. 2015. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

Of the 1,418 identified reports, 14 prospective studies met our eligibility criteria (Supplemental Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 2). Among those, 6 studies9, 13, 14, 16, 24, 31 were published and 8 cohorts25–30, 32, 33 offered previously unpublished data. As two of the studies included the same population, we contacted 13 cohorts and asked them to share IPD. Of these, 11 international cohorts (from Europe, the United States and Australia) agreed to provide IPD and we added summary estimates of 2 studies that did not provide IPD in random-effects models as sensitivity analyses.

After exclusion of participants with thyroxine and anti-thyroid medication use at baseline, 30,085 individuals were included in the final analysis (Supplemental Figure 1). Among included participants, median age was 69 years at inclusion, 51.6% were women, 28,127 individuals were euthyroid, and 1,958 (6.5%) had endogenous subclinical hypothyroidism. Median follow-up ranged from 1.3 to 17 years across the different studies, adding up to 278,955 person-years of follow-up; during this time, 2,574 individuals (8.6%) developed incident AF. Thyroid medication use (thyroxine and anti-thyroid medication) during follow-up varied from 1.2–11.2% in the various studies (Table 1). Compared to participants with euthyroidism, those with subclinical hypothyroidism were older, more likely to be female or affected by comorbidities including cardiovascular disease or diabetes (Supplemental Table 3).

Overall study quality was high; all included studies scored 6 points or higher on the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. All cohorts were community-based, and two27, 32 cohorts did not use ECG review to diagnose AF. Length of follow-up was more than five years, except for two studies,27, 31 and loss of follow-up was lower than 5% in 6 studies (Supplemental Table 4).

Thyroid stimulating hormone within the Reference Range and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation

Crude incidence rates are presented in Figure 1. In age- and sex-adjusted analyses, there was no association between TSH levels in the reference range and risk of AF (Figure 1). When analyzing continuous concentrations of TSH, the risk of AF increased with low normal TSH levels and slightly decreased with higher TSH levels (but remaining close to a hazard ratio [HR] of 1.0) compared to the reference level of 3.5mIU/l (Supplemental Figure 3). Sensitivity analyses yielded similar results (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 5), and no significant interaction was found when analyses were stratified according to sex, age, or previous cardiovascular disease. In the analysis with additional inclusion of individuals with thyroxine use at baseline, point estimates were higher among thyroxine users than among those not on thyroxine in a subgroup analysis, however without statistical significance likely because of the limited number of thyroxine users (n=1146, Supplemental Table 6).

Figure 1.

Association between thyroid stimulating hormone and the risk of atrial fibrillation. Participants who used thyroid hormones at baseline were excluded. CI, confidence interval; p-y, person-years; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Table 3.

Main and Sensitivity Analysis of the Association between Thyroid Stimulating Hormone within the Reference Range and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation

| TSH level (mlU/l) | 0.45–0.99 | 1.00–1.49 | 1.50–2.49 | 2.50–3.49 | 3.50–4.49 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events / Persons |

HR (95% CI) |

Events / Persons |

HR (95% CI) |

Events / Persons |

HR (95% CI) |

Events / Persons |

HR (95% CI) |

Events / Persons |

HR (95% CI) |

|

| All available cohorts | ||||||||||

| Age- and sex-adjusted | 372/5665 | 1.10 (0.92–1.31) | 492/6275 | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | 893/9990 | 1.04 (0.89–1.22) | 412/4391 | 0.94 (0.79–1.12) | 190/1806 | ref. |

| Multivariable adjusted analysis* | 370/5611 | 1.07 (0.89–1.28) | 487/6199 | 0.99 (0.84–1.18) | 882/9841 | 1.02 (0.87–1.19) | 410/4336 | 0.92 (0.78–1.10) | 187/1777 | ref. |

| Further adjustments of multivariable models* | ||||||||||

| Plus antihypertensive and lipid lowering medication | 357/4924 | 1.06 (0.88–1.27) | 469/5699 | 0.98 (0.83–1.17) | 862/9297 | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) | 405/4138 | 0.94 (0.78–1.12) | 180/1703 | ref. |

| Plus BMI | 356/4911 | 1.07 (0.89–1.29) | 466/5682 | 0.99 (0.84–1.18) | 855/9257 | 1.02 (0.87–1.20) | 403/4120 | 0.94 (0.79–1.13) | 179/1696 | ref. |

| Medication affecting thyroid function | ||||||||||

| Including all regardless of thyroid medication use † | 399/5920 | 1.10 (0.92–1.31) | 516/6437 | 1.05 (0.89–1.24) | 925/10226 | 1.06 (0.91–1.23) | 432/4533 | 0.96 (0.81–1.14) | 200/1914 | ref. |

| Excluding thyroid medication use at BL and/or FUP ‡ | 370/5552 | 1.10 (0.91–1.32) | 483/6217 | 1.01 (0.85–1.21) | 881/9902 | 1.04 (0.88–1.22) | 393/4305 | 0.93 (0.78–1.11) | 173/1722 | ref. |

| Excluding users of amiodarone § | 367/5639 | 1.09 (0.91–1.30) | 490/6254 | 1.03 (0.87–1.21) | 889/9958 | 1.04 (0.89–1.22) | 408/4380 | 0.94 (0.78–1.11) | 190/1795 | ref. |

| Excluding users of other drugs affecting thyroid function ‖ | 241/4536 | 1.21 (0.96–1.53) | 302/4815 | 1.12 (0.89–1.40) | 531/7364 | 1.13 (0.91–1.40) | 222/3059 | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | 103/1273 | ref. |

| Thyroid function | ||||||||||

| Excluding participants with missing values of fT4 # | 288/4808 | 1.10 (0.89–1.34) | 365/4983 | 1.01 (0.83–1.22) | 650/7561 | 1.01 (0.85–1.21) | 289/3097 | 0.90 (0.74–1.10) | 147/1314 | ref. |

| Including only participants with persistent thyroid function state ** | 62/905 | 0.96 (0.61–1.51) | 102/1304 | 1.04 (0.68–1.60) | 214/2237 | 1.20 (0.81–1.80) | 78/985 | 0.91 (0.59–1.41) | 27/314 | ref. |

| Excluding studies | ||||||||||

| Excluding studies with AF diagnosis without ECG review †† | 282/3912 | 1.13 (0.92–1.39) | 356/3651 | 1.05 (0.86–1.27) | 683/5517 | 1.11 (0.93–1.33) | 334/2673 | 1.00 (0.82–1.21) | 147/1094 | ref. |

| Excluding studies with >5% lost to follow-up ‡‡ | 236/3100 | 1.05 (0.83–1.33) | 324/4515 | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | 574/7851 | 1.03 (0.83–1.28) | 233/3407 | 0.89 (0.71–1.13) | 99/1354 | ref. |

| Excluding MrOS Study §§ | 364/5595 | 1.10 (0.92–1.32) | 477/6144 | 1.03 (0.87–1.23) | 874/9752 | 1.06 (0.90–1.25) | 402/4254 | 0.96 (0.81–1.14) | 182/1749 | ref. |

| Excluding SHIP Study ‖‖ | 343/4046 | 1.10 (0.92–1.32) | 483/5775 | 1.02 (0.86–1.21) | 891/9820 | 1.04 (0.89–1.22) | 412/4359 | 0.94 (0.79–1.12) | 190/1800 | ref. |

Abbreviations: AF, Atrial Fibrillation; BMI, Body Mass Index; BL, Baseline; CI, Confidence Interval; E, events; ECG, Electrocardiogram; fT4, free Thyroxin; FUP, Follow-up; HR, Hazard Ratio; MrOS, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study; P, participants; ref., reference; SHIP, Study of Health in Pomerania; TSH, Thyroid Stimulating Hormone

Adjusted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure, current and former smoking, diabetes, total cholesterol, and prevalent cardiovascular disease at baseline.

For this sensitivity analysis, we added a total of 1177 thyroid medication users (thyroxin or anti-thyroid drugs) to the overall sample: 253 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study; 207 in the Health ABC Study; 43 in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study; 15 in the Bari Study; 12 in the Leiden 85+ Study; 107 in the Study of Health in Pomerania; 21 in the Invecchiare in Chianti Study; 26 in the Rotterdam Study; 188 in the PROSPER Study; 301 in the EPIC-Norfolk Study; and, 4 in the Busselton Health Study.

The number of thyroid medication users (thyroxin or anti-thyroid drugs) during follow-up are indicated in Table 1

A total of 123 participants who took amiodarone were excluded for this sensitivity analysis of the association between TSH and AF: 2 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study; 3 in the Health ABC Study; 1 in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study; 79 in the Bari Study; 1 in the Leiden 85+ Study; 1 in the Study of Health in Pomerania; 6 in the Invecchiare in Chianti Study; 6 in the Rotterdam Study; 23 in the PROSPER Study; 1 in the EPIC-Norfolk Study. Information on amiodarone use was not available in the Busselton Health Study.

A total of 7,786 participants who took other medications that could alter thyroid levels (corticosteroids, amiodarone, iodine, lithium, aspirin, furosemide) were excluded for this sensitivity analysis: 1,634 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study; 881 in the Health ABC Study; 245 in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study; 251 in the Bari Study; 56 in the Leiden 85+ Study; 299 in the Study of Health in Pomerania; 122 in the Invecchiare in Chianti Study; 151 in the Rotterdam Study; 3,199 in the PROSPER Study; 948 in the EPIC-Norfolk Study.

A total of 311 participants were excluded for this analysis: 22 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study; 5 in the Leiden 85+ Study; 1 in the InChianti Study; 282 in the Rotterdam Study; and 1 in the Busselton Health Study had missing measurements for fT4. In participants in the Health ABC study, fT4 was measured only in participants with TSH ≥7.0 mIU/L (therefore, no fT4 measurement in 2270 participants) and, in the PROSPER Study, fT4 was measured only in participants with TSH <0.45mIU/l or TSH ≥4.5mIU/l (therefore, no fT4 measurement in 4220 participants)

Persistent thyroid function state was defined as persistent category (euthyroidism, subclinical hypothyroidism) from baseline to follow-up thyroid function test. Follow-up thyroid function was measured in the Cardiovascular Health Study, Leiden 85-plus Study, PROSPER Study, Study of Health in Pomerania, and the Busselton Health Study.

The Bari and EPIC-Norfolk studies were excluded.

The Cardiovascular Health Study, MrOS Study, SHIP Study, InChianti Study, and Busselton Health Study were excluded.

In the MrOS Study, thyroid hormones were measured an average of 3.4 years before other baseline characteristics were assessed.

SHIP includes participants from Pomerania, where an iodine supplementation began in the mid-1990s, which shifted the distribution of TSH values towards the left during the first years, and lowered TSH values in the population in the SHIP Study during the baseline examinations in 1997–2001.

Subclinical Hypothyroidism and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation

Compared to the reference level of 3.50–4.49mIU/l, subclinical hypothyroidism was not associated with incident AF in age- and sex-adjusted analyses, with a HR of 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.74–1.14) for a TSH level of 4.5–6.9mIU/l, a HR of 1.02 (95% CI, 0.73–1.41) for a TSH level of 7.0–9.9mIU/l, and a HR of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.61–1.47) for a TSH level of 10.0–19.9mIU/l (Table 4). The results remained similar in sensitivity analyses (Table 4 and Supplemental Table 7), and analyses stratified by sex, age, previous cardiovascular disease, and thyroxine use at baseline showed no significant interaction (Supplemental Table 8). Adding overall relative risks (HRs not reported) of one study from which we were not able to obtain IPD9 yielded similar results for the association between subclinical hypothyroidism and AF (HR was 1.07, 95% CI, 0.72–1.58).

Table 4.

Main and Sensitivity Analysis of the Association between Subclinical Hypothyroidism and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation

| TSH level (mlU/l) | 3.50–4.49 | 4.5–6.9 | 7.0–9.9 | 10.0–19.9 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events / Participants |

HR (95% CI) |

Events / Participants |

HR (95% CI) |

Events / Participants |

HR (95% CI) |

Events / Participants |

HR (95% CI) |

|||

| All available cohorts | ||||||||||

| Age- and sex-adjusted | 190/1806 | ref. | 149/1384 | 0.92 (0.74–1.14) | 44/383 | 1.02 (0.73–1.41) | 22/191 | 0.94 (0.61–1.47) | ||

| Multivariable adjusted analysis* | 187/1777 | ref. | 149/1365 | 0.91 (0.74–1.14) | 43/377 | 0.95 (0.68–1.33) | 22/189 | 0.93 (0.60–1.44) | ||

| Further adjustments of multivariable models* | ||||||||||

| Plus antihypertensive and lipid lowering medication | 180/1703 | ref. | 146/1316 | 0.92 (0.74–1.14) | 41/363 | 0.92 (0.66–1.30) | 22/176 | 0.95 (0.61–1.48) | ||

| Plus BMI | 179/1696 | ref. | 144/1307 | 0.92 (0.74–1.15) | 41/362 | 0.93 (0.66–1.31) | 22/176 | 0.96 (0.61–1.49) | ||

| Medication affecting thyroid function | ||||||||||

| Including all regardless of thyroid medication use † | 200/1914 | ref. | 162/1521 | 0.91 (0.74–1.12) | 47/457 | 0.92 (0.67–1.26) | 33/254 | 1.09 (0.75–1.57) | ||

| Excluding thyroid medication use at BL and/or FUP‡ | 173/1722 | ref. | 111/1208 | 0.89 (0.70–1.13) | 35/296 | 1.27 (0.88–1.83) | 12/120 | 1.07 (0.60–1.93) | ||

| Excluding users of amiodarone | 190/1795 | ref. | 148/1376 | 0.92 (0.74–1.14) | 44/377 | 1.02 (0.74–1.42) | 20/183 | 0.89 (0.56–1.42) | ||

| Excluding users of other drugs affecting thyroid function § | 103/1273 | ref. | 81/891 | 1.08 (0.81–1.44) | 27/243 | 1.29 (0.84–1.97) | 11/118 | 1.15 (0.62–2.14) | ||

| Thyroid function | ||||||||||

| Excluding participants withmissing values of fT4‖ | 147/1314 | ref. | 124/997 | 0.98 (0.77–1.24) | 40/339 | 1.02 (0.71–1.45) | 22/185 | 0.98 (0.62–1.54) | ||

| Including only participants with persistent thyroid function state # | 27/314 | ref. | 10/159 | 0.70 (0.34–1.44) | 4/84 | 0.55 (0.19–1.57) | 6/43 | 1.70 (0.70–4.12) | ||

| Excluding studies | ||||||||||

| Excluding studies with AF diagnosis without ECG review ** | 147/1094 | ref. | 131/951 | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) | 33/245 | 0.95 (0.65–1.39) | 19/132 | 1.02 (0.63–1.65) | ||

| Excluding studies with >5% lost to follow-up †† | 99/1354 | ref. | 60/992 | 0.78 (0.56–1.07) | 22/280 | 1.10 (0.69–1.74) | 8/130 | 0.76 (0.37–1.57) | ||

| Excluding MrOS Study ‡‡ | 182/1749 | ref. | 148/1351 | 0.95 (0.76–1.18) | 43/374 | 1.03 (0.74–1.43) | 22/188 | 0.96 (0.62–1.50) | ||

| Excluding SHIP Study §§ | 190/1800 | ref. | 149/1374 | 0.92 (0.74–1.14) | 44/382 | 1.02 (0.73–1.41) | 22/190 | 0.94 (0.61–1.47) | ||

Abbreviations: AF, Atrial Fibrillation; BMI, Body Mass Index; BL, Baseline; CI, Confidence Interval; ECG, Electrocardiogram; fT4, free Thyroxin; FUP, Follow-up; HR, Hazard Ratio; MrOS, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study; ref., reference; SHIP, Study of Health in Pomerania; TSH, Thyroid Stimulating Hormone

Adjusted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure, current and former smoking, diabetes, total cholesterol, and prevalent cardiovascular disease at baseline.

Thyroid medication was defined as thyroxin or anti-thyroid drugs.

The numbers of thyroid medication users during follow-up are indicated in Table 1.

Other medications that could alter thyroid levels: corticosteroids, amiodarone, iodine, lithium, aspirin, furosemide.

A total of 311 participants were excluded for this analysis: fT4 measurements were missing for 22 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study, 5 in the Leiden 85+ Study, 1 in the InChianti Study, 282 in the Rotterdam Study, and 1 in the Busselton Health Study. In participants of the Health ABC study, fT4 was measured only in those with TSH ≥ 7.0 mIU/L (therefore, no fT4 measurement in 2270 participants); in the PROSPER Study, fT4 was measured only in participants with TSH <0.45mIU/l or TSH ≥4.5mIU/l (therefore, no fT4 measurement in 4220 participants).

Persistent thyroid function state was defined as persistent category (euthyroidism, subclinical hypothyroidism) from baseline to follow-up thyroid function test. Follow-up thyroid function was measured in the Cardiovascular Health Study, Leiden 85-plus Study, PROSPER Study, Study of Health in Pomerania, and the Busselton Health Study.

The Bari and EPIC-Norfolk studies were excluded.

The Cardiovascular Health Study, MrOS Study, SHIP Study, InChianti Study, and Busselton Health Study were excluded.

In the MrOS Study, thyroid hormones were measured an average of 3.4 years before atrial fibrillation was first assessed.

SHIP includes participants from Pomerania, where an iodine supplementation began in the mid-1990s, which shifted the distribution of TSH values towards the left during the first years, and lowered TSH values in the population in the SHIP Study during the baseline examinations in 1997–2001.

Free Thyroxine within the Reference Range and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation

Crude incidence rates are shown in Figure 2. Among the 30,085 individuals included in our study, 20,921 were included in the analysis of the association between fT4 and AF, having both their TSH and fT4 within the reference range. In those individuals, higher fT4 levels at baseline were associated with increased risk of AF in age- and sex-adjusted analyses, with a HR of 1.17 (95% CI, 1.02–1.35) in the second quartile, a HR of 1.25 (95% CI, 1.09–1.43) in the third, and a HR of 1.45 (95% CI, 1.26–1.66) in the fourth quartile compared to the first (lowest) quartile of fT4 levels (p for trend across fT4 levels ≤0.001) (Figure 2). When modeled as a continuous variable, increasing fT4 levels within the reference range were associated with an increased risk of AF (Supplemental Figure 4). In analyses with multivariable adjustment for age, sex, systolic blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, total cholesterol, and prevalent cardiovascular disease at baseline, HRs remained similar. Further adjustments for antihypertensive, lipid lowering medication, and BMI did not significantly change the results. Sensitivity analyses yielded similar results (Table 5 and Supplemental Table 9). Risks were similar when all individuals regardless of thyroid medication use at baseline were included, or after excluding studies without AF diagnosis by ECG review,27, 32 or when excluding a study26 that started follow-up of incident AF an average of 3.4 years after baseline thyroid function was measured. Estimates did not change substantially after we added the aggregate results from a study that did not provide IPD.24

Figure 2.

Association between quartiles of free thyroxine within the reference range and the risk of atrial fibrillation. The reference range for TSH was defined as 0.45–4.49mIU/l. For fT4, we used study-specific cutoff values. Participants who used thyroid hormones at baseline were excluded. CI, confidence interval; fT4, free thyroxine; p-y, person-years; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Table 5.

Main and Sensitivity Analysis of the Association between Quartiles of Free Thyroxine within the Reference Range and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation *

| fT4 quartile | First quartile |

Second quartile |

Third quartile |

Fourth quartile |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events / Participants |

HR (95% CI) |

Events / Participants |

HR (95% CI) |

Events / Participants |

HR (95% CI) |

Events / Participants |

HR (95% CI) |

P for trend |

|

| All available cohorts | |||||||||

| Age- and sex-adjusted | 371/5642 | ref. | 390/4989 | 1.17 (1.02–1.35) | 438/5272 | 1.25 (1.09–1.43) | 474/5018 | 1.45 (1.26–1.66) | ≤0.001 |

| Multivariable adjusted analysis † | 367/5551 | ref. | 384/4912 | 1.16 (1.00–1.33) | 429/5198 | 1.19 (1.04–1.37) | 472/4947 | 1.39 (1.22–1.60) | ≤0.001 |

| Further adjustments of multivariable models† | |||||||||

| Plus antihypertensive and lipid lowering medication | 358/4949 | ref. | 368/4526 | 1.12 (0.97–1.30) | 415/4693 | 1.15 (1.00–1.32) | 450/4494 | 1.31 (1.14–1.50) | ≤0.001 |

| Plus BMI | 354/4928 | ref. | 366/4507 | 1.13 (0.98–1.31) | 410/4669 | 1.15 (1.00–1.33) | 447/4469 | 1.33 (1.16–1.53) | ≤0.001 |

| Medication affecting thyroid function | |||||||||

| Including all regardless of thyroid medication use ‡ | 380/5731 | ref. | 429/5194 | 1.18 (1.03–1.36) | 447/5466 | 1.29 (1.12–1.48) | 487/5089 | 1.43 (1.25–1.63) | ≤0.001 |

| Excluding thyroid medication use at BL and/or FUP § | 355/5533 | ref. | 390/4969 | 1.15 (1.00–1.33) | 407/5105 | 1.25 (1.08–1.44) | 467/4966 | 1.46 (1.27–1.67) | ≤0.001 |

| Excluding users of amiodarone ‖ | 369/5626 | ref. | 391/4969 | 1.18 (1.03–1.36) | 437/5265 | 1.25 (1.09–1.44) | 468/4998 | 1.44 (1.25–1.65) | ≤0.001 |

| Excluding users of other drugs affecting thyroid function # | 236/4676 | ref. | 250/4183 | 1.13 (0.95–1.36) | 288/4359 | 1.30 (1.10–1.55) | 301/4114 | 1.44 (1.21–1.70) | ≤0.001 |

| Excluding Studies | |||||||||

| Excluding studies with AF diagnosis without ECG review ** | 257/2710 | ref. | 282/2331 | 1.24 (1.05–1.47) | 293/2545 | 1.21 (1.02–1.43) | 300/2354 | 1.39 (1.18–1.64) | ≤0.001 |

| Excluding studies with >5% lost to follow-up †† | 174/3517 | ref. | 181/3202 | 1.12 (0.91–1.37) | 211/3306 | 1.27 (1.04–1.55) | 237/3202 | 1.44 (1.18–1.75) | ≤0.001 |

| Excluding MrOS Study ‡‡ | 361/5475 | ref. | 373/4837 | 1.15 (1.00–1.33) | 424/5126 | 1.24 (1.07–1.42) | 457/4864 | 1.43 (1.24–1.64) | ≤0.001 |

| Aggregate data | |||||||||

| Including aggregate data of the Rotterdam Study Cohorts I, II, and III §§ | 402/7186 | ref. | 428/6545 | 1.15 (1.01–1.32) | 473/6812 | 1.22 (1.07–1.39) | 533/6545 | 1.45 (1.27–1.65) | 0.017 |

Abbreviations: AF, Atrial Fibrillation; BMI, Body Mass Index; BL, Baseline; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; CI, Confidence Interval; ECG, Electrocardiogram; fT4, free Thyroxin; FUP, Follow-up; HR, Hazard Ratio; MrOS, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study; ref., reference; SHIP, Study of Health in Pomerania; TSH, Thyroid Stimulating Hormone.

This analysis was restricted to normal thyroid function (TSH and free thyroxine in the reference range). From the overall sample, we excluded 9164 participants for this analysis because their fT4 measurements were missing or their thyroid function was outside the reference range: 479 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study; 59 in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study; 32 in the Bari Study; 137 in the Leiden 85+ Study; 125 in the Study of Health in Pomerania; 42 in the InChianti Study; 365 in the Rotterdam Study; 897 in the EPIC-Norfolk Study; and, 57 in the Busselton Health Study. In participants of the Health ABC Study, fT4 was measured only in TSH ≥ 7.0 mIU/L, so we excluded all 2346 participants for this analysis. In the PROSPER Study, fT4 was measured only in participants with TSH <0.45mIU/l or TSH ≥4.5mIU/l, so, 4625 participants were excluded from this analysis. The first quartile was the lowest one.

Adjusted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure, current and former smoking, diabetes, total cholesterol, and prevalent cardiovascular disease at baseline.

A total of 559 participants with thyroid medication use (thyroxin or anti-thyroid drugs) at baseline were additionally added for this analysis: 167 participants in the CHS; 33 of the MrOS; 9 in the Bari Study; 5 in the Leiden 85+ Study; 85 in the SHIP; 16 in the InChianti Study; 9 in the Rotterdam Study; 8 in the PROSPER Study; 224 in the EPIC-Norfolk Study; and 3 in the Busselton Health Study.

A total of 348 participants were on thyroid medication during follow-up: 139 participants in the CHS; 11 in the MrOS; 15 in the Bari Study; 3 in the Leiden 85+ Study; 156 in the SHIP; 13 in the InChianti Study; 2 in the PROSPER Study; and 9 in the Busselton Health Study.

A total of 63 participants who took amiodarone were excluded for this sensitivity analysis of the association between fT4 and AF: 1 participant in the CHS; 1 in the MrOS; 57 in the Bari Study; 3 in the InChianti Study; and 1 in the EPIC-Norfolk Study. Information on amiodarone use was not available in the Busselton Health Study.

We excluded a total of 3,589 participants with intake of other medications that could alter thyroid levels (corticosteroids, amiodarone, iodine, lithium, aspirin, furosemide) for this analysis: 1,395 participants in the CHS; 215 in the MrOS Study; 220 in the Bari Study; 33 in the Leiden 85+ Study; 286 in the SHIP; 111 in the InChianti Study; 103 in the Rotterdam Study; 348 in the PROSPER Study; and 878 in the EPIC-Norfolk Study.

The Bari and EPIC-Norfolk studies were excluded. We excluded a total of 10,981 participants from this sensitivity analysis: 236 participants in the Bari Study, and 10,745 in the EPIC-Norfolk Study.

The Cardiovascular Health Study, MrOS Study, SHIP Study, InChianti Study, and Busselton Health Study were excluded.

In the MrOS Study, thyroid hormones were measured an average of 3.4 years before the first assessment of atrial fibrillation.

Individual participant data were not available from the study by Chaker et al., which included aggregate results from the Rotterdam Study Cohorts I, II, and III.24 For this sensitivity analysis, we excluded individual participant data from the Rotterdam Study Cohort I (1244 participants with 171 events) that we had obtained from an earlier publication16 in order to avoid duplicate participants

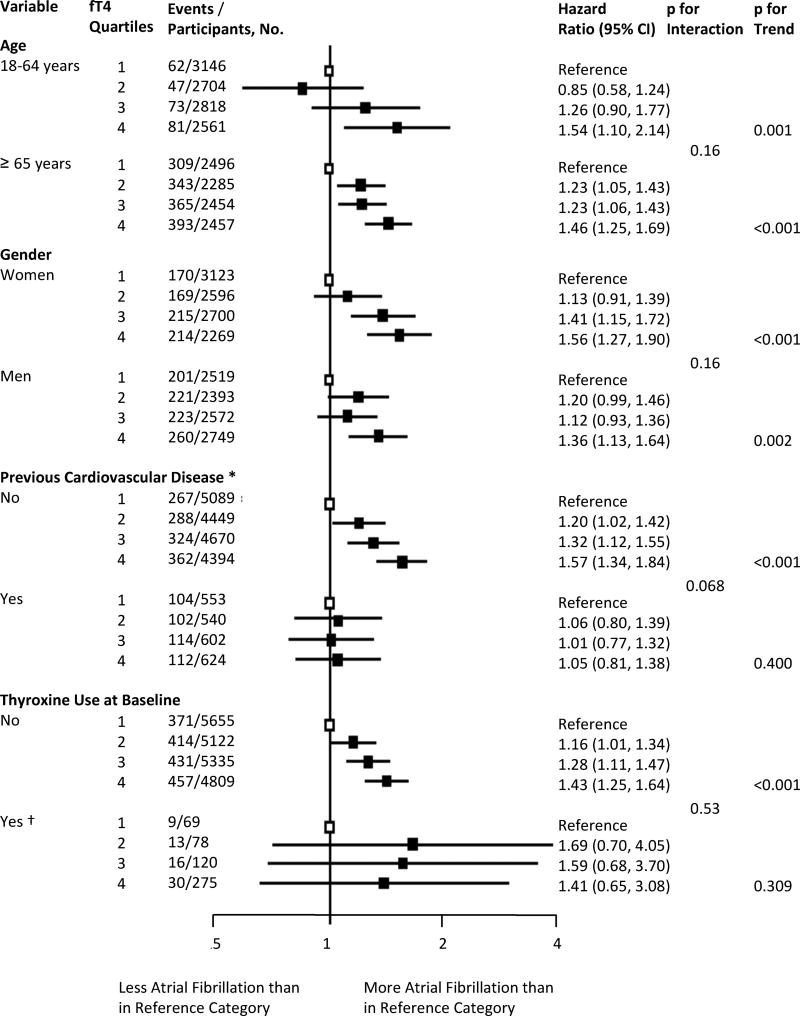

Stratified results are presented in Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 10. Compared to those without known cardiovascular disease, participants with previous cardiovascular disease showed no association between fT4 levels and AF risk. However, this finding might be affected by selection bias due to exclusion of participants with prevalent AF at baseline. Risks did not differ substantially according to age, sex, and race. In an additional analysis including thyroxine users, risks were similar irrespective of thyroxine intake at baseline.

Figure 3.

Stratified analyses for the association between quartiles of free thyroxine within the reference range and risk of atrial fibrillation. We defined the reference range for TSH as 0.45–4.49mIU/l and used study-specific cutoff values for fT4; the first fT4 quartile was the lowest one. The p for trend refers to a linear trend. CI, confidence interval; fT4, free thyroxine, TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

* Previous cardiovascular disease was defined as a history of stroke, transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, coronary angioplasty, or bypass surgery.

† 542 participants with available fT4 measurements and normal thyroid function were on thyroxine at baseline: 167 participants in the CHS; 33 in the MrO2; 6 in the Bari; 5 in the Leiden 85+ Study; 76 in SHIP; 11 in the InChianti Study; 9 in the Rotterdam Study; 8 in the PROSPER Study; 224 in the EPIC-Norfolk Study; and, 3 in the Busselton Health Study.

Assessment of Potential Publication Bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plot did not suggest publication bias for the association between fT4 within the reference range and the risk of AF (Supplemental Figure 5).

Discussion

Our IPD analysis including 30,085 individuals from 11 prospective cohorts showed no association between TSH levels within the reference range or subclinical hypothyroidism and risk of AF. In euthyroid individuals, we found a significant increase in the risk of AF with increasing fT4 levels within the reference range. Risks did not differ significantly by age and sex.

To our knowledge, our study is the first IPD analysis of prospective cohorts on the association between thyroid function in the reference range or subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of AF. Our study was strengthened by its large sample size, which allowed us to assess risks in subgroups by TSH levels in the normal range. Furthermore, our results were robust across all sensitivity analyses. By conducting an IPD analysis, our results are free of potential aggregation bias found in study-level meta-analyses,18 and we could explore the impact of age, sex, and thyroid medication in subgroup analyses. This approach also enabled us to standardize definitions of predictors and outcomes, use uniform adjustments for potential confounders to reduce heterogeneity across studies, and include unpublished data to increase robustness of our results and power to detect associations. IPD analyses are the ideal approach to aggregating evidence by pooling estimates from multiple studies.19

Our study confirmed previous results from two recent prospective population-based studies that found an increased risk of AF in higher fT4 levels in euthyroid individuals, while TSH levels were not associated with AF.14, 24 Similar results were shown in a cross-sectional study that included older adults.17 Recently, a large Danish retrospective register study of more than half a million individuals found a linear increase in risk of incident AF with decreasing TSH levels, resulting in a protective effect of subclinical hypothyroidism on AF compared to the euthyroid state. Participants in the high-normal euthyroidism subgroup defined as TSH of 0.2–0.4mIU/l with thyroxine levels in the reference range had a higher AF risk (incident rate ratio 1.12, 95% CI, 1.03–1.21) compared to low normal euthyroidism, defined as TSH 0.4–5.0mIU/l.11 However, the investigators chose different TSH cut-off values than used in our and other studies,8, 9, 13, 16, 17 and defined the TSH range 0.2–0.4mU/l as high normal euthyroidism (which was defined as subclinical hyperthyroidism in our study); strictly speaking, risk of AF within the euthyroid range with a TSH of 0.4–5.0mU/l has not been investigated. In contrast to the Danish study, we identified no significant association between subclinical hypothyroidism with AF, but our results showed a similar trend across higher TSH levels. However, the Danish study was based on retrospective administrative data, which has inherent drawbacks, including potential confounding by indication (TSH was not randomly ordered by general practitioners) and no ECG confirmation of AF. In contrast, the results of the Framingham Heart Study aligned with ours, where no association between TSH levels above the reference range and the risk of AF was found among 5069 participants during a 10-year follow up.12

Thyroxine is one of the most frequently prescribed drugs in the United States (almost 120 million prescriptions are dispensed annually)40 and prescriptions continue to rise, even for individuals with TSH levels below 10mIU/l.41 Although our primary analyses focused on endogenous thyroid function, we also examined thyroxine users in stratified analyses. These results remained consistent with higher AF risk with increasing FT4 levels; our data also showed that the majority of thyroxine users had a fT4 level in the highest quartile. However, the subgroup of individuals on thyroid replacement therapy at baseline was comparatively small in our study (n=1146), which precludes a meaningful interpretation of the AF risk associated with thyroxine therapy. Further studies are needed to evaluate whether our findings apply to this subgroup.

Our study has several limitations. First, we did not pre-specify our analysis of the association between fT4 and AF risk in the protocol; because two prospective cohorts, published after we completed our protocol, found a significant association between fT4 in the euthyroid range and incident AF,14, 24 we decided to explore AF risk according to fT4 levels. Our robust results have confirmed these previous findings. Second, AF can be paroxysmal or asymptomatic, and real incident date for AF might have been missed in the cohorts that diagnosed AF solely by ECG review during study visits. Therefore, we might have substantially underestimated the true incidence of AF in our study and introduced non-differential misclassification of outcomes, which would result in an underestimation of the association. Third, only five of the included studies provided data on follow-up thyroid function measurements, so data on the evolution of thyroid function over time was limited, which applies to most published large cohorts.13, 16, 25 This limitation mainly affects the analysis of individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism, who might reverse to normal thyroid function or progress to overt thyroid dysfunction. However, a sensitivity analysis including only participants with persistent thyroid function during follow-up thyroid function measurements yielded similar estimates. Fourth, despite the large number of individuals we included in our analysis, important subgroups of interest (such as participants with high TSH levels or individuals on thyroxine therapy at baseline) were small, and analyses restricted to these subgroups were underpowered. Fifth, we could not obtain IPD from two studies that met our inclusion criteria. Therefore, we performed sensitivity analyses adding the published aggregate results from these two studies,9, 24 which yielded similar results. We could not add the aggregate results of the association between TSH in the reference range and AF published in the study by Chaker and colleagues, because they used different TSH cut-offs by subdividing TSH into quartiles.24 Sixth, we were not able to include time-updated variables in our analyses due to limited availability. Seventh, the definition of some of the baseline covariates including cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus were heterogeneous across different cohorts. Finally, our study included mainly Caucasians and younger participants were few (median age 69 years), which reduces the generalizability of our findings to other populations.

The mechanism for the association between thyroid function and AF may be explained by the effects of thyroid hormones on the cardiovascular system. Thyroid function in the high range leads to an increase in vascular resistance, cardiac contractility, heart rate and left ventricular mass.42 Thyroid hormone levels in the high range have been shown to be arrhythmogenic43 and increase the frequency of atrial premature beats,44 which in turn is a risk factor for AF.45 These effects may explain the observation of an increased risk of AF in subclinical hyperthyroidism8 but not subclinical hypothyroidism. Due to the negative feedback, a negative log-linear relationship exists between fT4 and TSH with disproportionately larger changes in TSH concentrations than those of fT4.46 Therefore, TSH would be expected to be more sensitive than fT4 to predict outcomes. However, circulating fT4 is peripherally converted to the biologically active triiodothyronine, which binds on nuclear receptors and mediates gene expression with consecutive effects on end-organs, whereas TSH is a marker of pituitary effects of thyroid function.47 In contrast to the positive association between fT4 and AF, we did not find an association between TSH levels in the reference range and AF, and this pattern of a positive association between fT4 but not TSH values in the reference range has also been shown for other adverse cardiac outcomes including congestive heart failure14 and sudden cardiac death,15 as well as for blood pressure.48 These results of the effect of normal thyroid function on the heart are in contrast to the findings of a statistically significant inverse association between TSH levels within the reference range and dementia, whereas no significant association between fT4 levels in the normal range and rates of dementia was found in this study,14 suggesting that thyroid hormone metabolism and action differs between target organs such as the heart and brain because of differences in deiodinase activity and thyroid hormone receptor expression;47 these differences may explain why some clinical phenotypes are associated with fT4 only, some with TSH only, and others with both. These findings are also consistent with the observation that fT4 concentrations may differ even among euthyroid persons with the same TSH values:49 individuals with higher fT4 values have higher cardiac exposure to thyroid hormones and are consecutively at a higher risk of AF, which is reflected by the findings of our study. Levels of fT4 might be an additive risk factor for adverse cardiac outcomes; however, before making recommendations for fT4 screening in euthyroid individuals, further (ideally randomized) studies are needed to assess benefits and harms of fT4 screening.

In conclusion, our IPD analysis of prospective cohorts showed that fT4 levels within the high-normal range were associated with increased risk of incident AF, but incident AF events did not increase across TSH categories within the euthyroid range or in subclinical hypothyroidism. Further studies are needed to investigate whether these results apply to thyroxine users, which might entail a careful evaluation of the risks and benefits of current target thyroid hormone concentrations for thyroid replacement therapy.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What Is new?

Subclinical hyperthyroidism is associated with increased risk of atrial fibrillation, but the association with thyroid function in the normal range or subclinical hypothyroidism is unclear.

We performed an individual participant data analysis investigating the association between thyroid function within the normal range or subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of atrial fibrillation, including more than 30,000 participants from 11 prospective cohort studies.

Our study showed that higher free thyroxine levels were associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation in euthyroid persons, whereas thyroid stimulating hormone levels were not.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Given the high prevalence of atrial fibrillation and its potentially disabling clinical outcomes, identification of modifiable risk factors is important.

Free thyroxine levels might add to further assessment of atrial fibrillation risk

Further studies need to investigate whether these findings apply to thyroxine-treated patients, who often have higher circulating free thyroxine levels than untreated participants, to assess whether treatment goals should be modified.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of all studies, study participants, investigators, staff from all participating studies, and participating general practitioners, pharmacists, and other health-care professionals. We thank Hendrika Anette van Dorland for her help with data preparation and Kali Tal for her editorial suggestions.

Participating Studies of the Thyroid Studies Collaboration

United States: Cardiovascular Health Study; Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study; Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study; United Kingdom: EPIC-Norfolk Study; the Netherlands: Leiden 85-plus Study; PROSPER Study; Rotterdam Study; Italy: Invecchiare in Chianti (InCHIANTI) Study; Bari Study; Germany: Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP); Australia: Busselton Health Study.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF 320030-138267 and 320030-150025) and partially supported by a grant from the Swiss Heart Foundation (principal investigator: Prof. N. Rodondi). The Cardiovascular Health Study was supported by contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086, and grants U01HL080295 and U01HL130114 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with an additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Further support was provided by R01AG023629 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at CHS-NHLBI.org. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) contract numbers N01-AG-6-2101, N01-AG-6-2103, N01-AG-6-2106; NIA grant R01-AG028050; and, NINR grant R01-NR012459. The NIA funded the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study, reviewed the manuscript, and approved its publication. The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study is supported by National Institutes of Health funding. The following institutes provide support: the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research under the following grant numbers: U01 AG027810, U01 AG042124, U01 AG042139, U01 AG042140, U01 AG042143, U01 AG042145, U01 AG042168, U01 AR066160, and UL1 TR000128. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) provides funding for the MrOS Sleep ancillary study, "Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men," under the following grant numbers: R01 HL071194, R01 HL070848, R01 HL070847, R01 HL070842, R01 HL070841, R01 HL070837, R01 HL070838, and R01 HL070839’. The Leiden 85-plus Study was partly funded by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports. The Rotterdam Study is funded by Erasmus MC and Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands; the Netherlands Organization for the Health Research and Development (ZonMw); the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE); the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science; the Dutch Ministry for Health, Welfare and Sports; the European Commission (DG XII); and, the Municipality of Rotterdam. Data from the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) was provided by the Community Medicine Research Network of the University of Greifswald, Germany, which is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01ZZ9603, 01ZZ0103, 01ZZ0701). The original PROSPER study was supported by an unrestricted, investigator-initiated grant obtained from Bristol-Myers Squibb. The EPIC-Norfolk study was supported by research grants from the Medical Research Council UK and Cancer Research UK.

C. Baumgartner’s work is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (P2BEP3_165409). Dr. Westendorp is supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NGI/NWO 911-03-016). Dr. T.-H. Collet’s research is supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (P3SMP3-155318, PZ00P3-167826). Dr. R.P. Peeters has received lecture and consultancy fees from Genzyme B.V.

Role of the Sponsor

None of the sponsors had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, except for: 1) The National Institute on Aging that funded the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study, reviewed the manuscript and approved its publication; and 2) this manuscript was reviewed by CHS for scientific content and consistency of data interpretation with previous CHS publications.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Susan R. Heckbert received modest research grant support from NIH grants U01HL130114 and HL080295. David J. Stott and Nicolas Rodondi received significant research funding from the European Union FP7 for the Thyroid Hormone Replacement for Subclinical Hypothyroidism (TRUST) trial. The other authors report no conflicts.

Author Contributions

Drs Baumgartner and Rodondi had full access to all data of the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of data analysis.

Study concept and design: Rodondi, Cappola, Bauer, Gussekloo.

Data acquisition: Rodondi, Gussekloo, Bauer, Bremner, Cappola, Ceresini, den Elzen, Heckbert, Heeringa, Iacoviello, Khaw, Luben, Macfarlane, Magnani, Stott, Westendorp, Walsh, Peeters, Dörr, Völzke.

Data analysis and interpretation: Baumgartner, Collet, da Costa, Rodondi, Bauer, Floriani, Collet.

Drafting the manuscript: Baumgartner, Rodondi, Feller.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Aujesky, Bauer, Bremner, Cappola, Dörr, Ceresini, Collet, da Costa, den Elzen, Feller, Floriani, Macfarlane, Gussekloo, Heckbert, Heeringa, Iacoviello, Khaw, Luben, Magnani, Peeters, Stott, Völzke, Walsh, Westendorp.

Statistical analyses: Baumgartner, da Costa, Collet, Rodondi.

Secured funding: Rodondi, Bauer, Gussekloo, Khaw, Westendorp, Walsh, Cappola, Ceresini, Peeters.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Baumgartner, Rodondi.

Study supervision: Rodondi.

References

- 1.Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, Singh D, Rienstra M, Benjamin EJ, Gillum RF, Kim YH, McAnulty JH, Jr, Zheng ZJ, Forouzanfar MH, Naghavi M, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray CJ. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014;129:837–847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98:946–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, Mathewson FA, Cuddy TE. The natural history of atrial fibrillation: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in the Manitoba Follow-Up Study. Am J Med. 1995;98:476–484. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woeber KA. Thyrotoxicosis and the heart. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:94–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207093270206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, Jr, Conti JB, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Murray KT, Sacco RL, Stevenson WG, Tchou PJ, Tracy CM, Yancy CW American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice G. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e1–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:526–534. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, Hannon WH, Gunter EW, Spencer CA, Braverman LE. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:489–499. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collet TH, Gussekloo J, Bauer DC, den Elzen WP, Cappola AR, Balmer P, Iervasi G, Asvold BO, Sgarbi JA, Volzke H, Gencer B, Maciel RM, Molinaro S, Bremner A, Luben RN, Maisonneuve P, Cornuz J, Newman AB, Khaw KT, Westendorp RG, Franklyn JA, Vittinghoff E, Walsh JP, Rodondi N. Subclinical hyperthyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:799–809. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawin CT, Geller A, Wolf PA, Belanger AJ, Baker E, Bacharach P, Wilson PW, Benjamin EJ, D'Agostino RB. Low serum thyrotropin concentrations as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in older persons. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1249–1252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodondi N, den Elzen WP, Bauer DC, Cappola AR, Razvi S, Walsh JP, Asvold BO, Iervasi G, Imaizumi M, Collet TH, Bremner A, Maisonneuve P, Sgarbi JA, Khaw KT, Vanderpump MP, Newman AB, Cornuz J, Franklyn JA, Westendorp RG, Vittinghoff E, Gussekloo J. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. JAMA. 2010;304:1365–1374. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selmer C, Olesen JB, Hansen ML, Lindhardsen J, Olsen AM, Madsen JC, Faber J, Hansen PR, Pedersen OD, Torp-Pedersen C, Gislason GH. The spectrum of thyroid disease and risk of new onset atrial fibrillation: a large population cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e7895. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim EJ, Lyass A, Wang N, Massaro JM, Fox CS, Benjamin EJ, Magnani JW. Relation of hypothyroidism and incident atrial fibrillation (from the Framingham Heart Study) Am Heart J. 2014;167:123–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cappola AR, Fried LP, Arnold AM, Danese MD, Kuller LH, Burke GL, Tracy RP, Ladenson PW. Thyroid status, cardiovascular risk, and mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295:1033–1041. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cappola AR, Arnold AM, Wulczyn K, Carlson M, Robbins J, Psaty BM. Thyroid function in the euthyroid range and adverse outcomes in older adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1088–1096. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaker L, van den Berg ME, Niemeijer MN, Franco OH, Dehghan A, Hofman A, Rijnbeek PR, Deckers JW, Eijgelsheim M, Stricker BH, Peeters RP. Thyroid Function and Sudden Cardiac Death: A Prospective Population-Based Cohort Study. Circulation. 2016;134:713–722. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heeringa J, Hoogendoorn EH, van der Deure WM, Hofman A, Peeters RP, Hop WC, den Heijer M, Visser TJ, Witteman JC. High-normal thyroid function and risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2219–2224. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gammage MD, Parle JV, Holder RL, Roberts LM, Hobbs FD, Wilson S, Sheppard MC, Franklyn JA. Association between serum free thyroxine concentration and atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:928–934. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ. 2010;340:c221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altman DG. Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables. BMJ. 2001;323:224–228. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7306.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, Tierney JF Group P-ID. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD Statement. JAMA. 2015;313:1657–1665. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gencer B, Collet TH, Virgini V, Bauer DC, Gussekloo J, Cappola AR, Nanchen D, den Elzen WP, Balmer P, Luben RN, Iacoviello M, Triggiani V, Cornuz J, Newman AB, Khaw KT, Jukema JW, Westendorp RG, Vittinghoff E, Aujesky D, Rodondi N. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction and the risk of heart failure events: an individual participant data analysis from 6 prospective cohorts. Circulation. 2012;126:1040–1049. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]