Abstract

The etiologies and prevalence of sporadic, postlingual-onset, progressive auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) have rarely been documented. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the prevalence and molecular etiologies of these cases. Three out of 106 sporadic progressive hearing losses turned out to manifest ANSD. Through whole exome sequencing and subsequent bioinformatics analysis, two out of the three were found to share a de novo variant, p.E818K of ATP1A3, which had been reported to cause exclusively CAPOS (cerebellar ataxia, areflexia, pes cavus, optic atrophy, and sensorineural hearing loss) syndrome. However, hearing loss induced by CAPOS has never been characterized to date. Interestingly, the first proband did not manifest any features of CAPOS, except subclinical areflexia; however, the phenotypes of second proband was compatible with that of CAPOS, making this the first reported CAPOS allele in Koreans. This ANSD phenotype was compatible with known expression of ATP1A3 mainly in the synapse between afferent nerve and inner hair cells. Based on this, cochlear implantation (CI) was performed in the first proband, leading to remarkable benefits. Collectively, the de novo ATP1A3 variant can cause postlingual-onset auditory synaptopathy, making this gene a significant contributor to sporadic progressive ANSD and a biomarker ensuring favorable short-term CI outcomes.

Introduction

Auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) is a type of hearing loss characterized by electrophysiological findings of an impaired or absent response in auditory brainstem responses (ABR), despite evidence of intact outer hair cell function as supported by the presence of cochlear microphonics and/or detectable otoacoustic emission (OAE). Subjects with ANSD have varying degrees of hearing losses; however, they generally present poor speech recognition that is disproportionate to the degree of hearing loss and difficulty hearing in noise1–3. The etiologies of ANSD are highly diverse, including hypoxia, infection, kernicterus, cytotoxic oncologic drug, and genetic factors4,5.

As for prelingual genetic ANSD, there seems to be less diversity compared with postlingual-onset genetic ANSD. Only a few genes have been associated with prelingual genetic ANSD, including autosomal recessive OTOF (DFNB9; the otoferlin gene, NM_001287489) and PJVK genes (DFNB59; the pejvakin gene, NM_001042702)6–9. GJB2 and mitochondrial 12SrRNA mutations have also been reported to be related to this phenotype10–13. Among them, OTOF mutations occupy a major part of prelingual ANSD in many Caucasian populations14. The predominance of OTOF mutations has also been established in Koreans as they were reported to account for up to 85% of the Korean population with prelingual ANSD with normal cochlear nerve15. As for postlingual-onset ANSD, a lot of syndromic forms that cause sensory and motor neuropathy have been documented in adults with ANSD, including Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease2,16,17, Friedreich’s ataxia18,19, deafness-dystonia-optic neuropathy (DDON) syndrome20, autosomal dominant optic atrophy (ADOA)21,22, and AUNX1 due to mutations in apoptosis-inducing factor23,24. However, there are not many reported genes related to non-syndromic, progressive ANSD with postlingual onset. Only mutations from DIAPH3 as the cause of AUNA125,26 have been anecdotally reported from familial ANSD cases, leaving a substantial portion of non-syndromic and sporadic forms of ANSD still unanswered with respect to the molecular etiology. SLC17A8 encoding VGLUT3, if altered, has been shown to cause ANSD in mice27,28; however, to date, phenotypes of ANSD have not been reported in human subjects with SLC17A8-induced hearing loss29,30.

Herein, we aimed to explore the molecular etiology of three unrelated subjects manifesting sporadic, progressive ANSD with postlingual onset. We identified that sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) in CAPOS syndrome (OMIM #601388), comprising of cerebellar ataxia, areflexia, pes cavus, optic atrophy, and hearing loss31–37, can fit into the category of ANSD and manifest in a non-syndromic manner.

Results

Diagnosis of ANSD

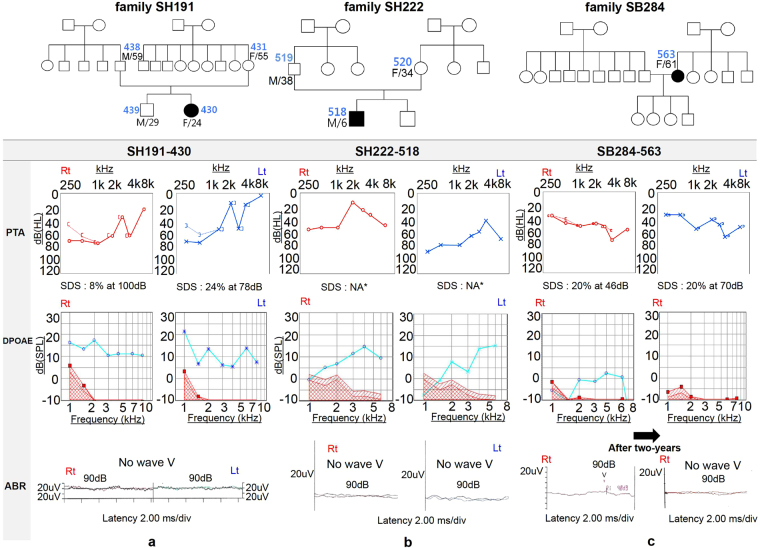

Among the 106 postlingually deafened subjects with moderate or higher degree of sporadic SNHL, at least three (3/106, 2.8%) unrelated subjects were documented to have ANSD (Fig. 1). The cochlear nerve in these subjects did not show any significant anatomic alterations.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees and audiological phenotype of the three probands. Pure tone audiograms of three ANSD subjects display moderate to severe sensorineural hearing loss, with poor speech discrimination score. DPOAE responses are observed, whereas ABR waveforms are absent or abnormal (a) SH191-430, (b) SH222-518, and (c) SB284-563. The patient SB284-563 shows detectable wave on ABR at 90 dB stimulus on the right ear and no response in both OAE and ABR after two-years. (PTA pure tone audiometry; SDS speech discrimination score; DPOAE distortion product optoacoustic emission; ABR auditory brainstem response; NA not available).

Molecular Genetic Testing and Delineation of Causative variant from the three subjects

We performed whole exome sequencing (WES) in three probands with sporadic ANSD and identified the most convincing causative variant using the bioinformatics filtering process that has previously been described38. This analytic step and the number of remaining candidates filtered at each step are listed (Table 1). Candidate variants were validated by standard Sanger sequencing and segregation study.

Table 1.

Filtering process of whole exome sequencing data obtained from three auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder subjects.

| Process | Detail | SH191-430 | SH222-518 | SB284-563 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Raw VCF | 537259 | 547209 | 525943 |

| 2 | Annotated variants | 261067 | 492276 | 525943 |

| 3 | Exonic variants | 12707 | 12839 | 24328 |

| 4 | Rare variants(ExAC & KRGDB < 0.01) | 973 | 1010 | 1021 |

| 5 | Not reported or Flagged SNP | 451 | 443 | 459 |

| 6 | Inheritance pattern with high-quality variants and cut-off | 165 | 120 | 186 |

| - De novo or dominant (MAF < 0.005) | 137 | 101 | 160 | |

| - Autosomal recessive- homozygote (MAF < 0.0005) | 6 | 7 | 7 | |

| - Autosomal recessive- compound heterozygote (MAF < 0.005) | 22 | 12 | 19 | |

| 7 | Additional information(SIFT, PP2, GERP score, CLINVAR) | 1* | 1* | 0 |

*c.2452 G > A: p.E818K of the ATP1A3 gene (NM_152296.4, NP_689509.1, OMIM *182350).

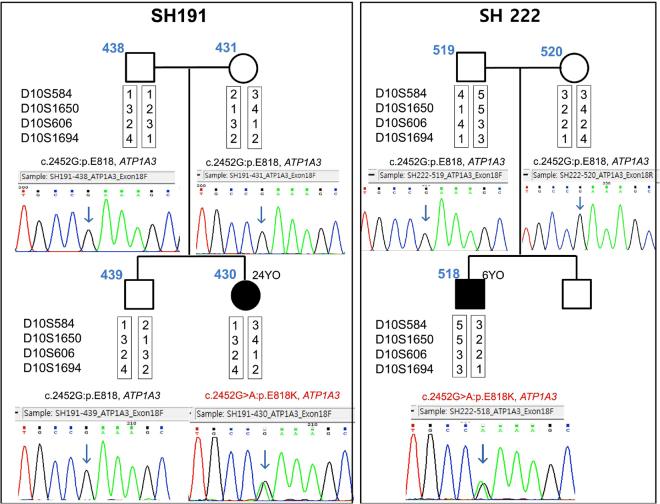

Interestingly, one heterozygous missense variant, c.2452 G > A: p.E818K of the ATP1A3 gene (NM_152296.4, NP_689509.1, OMIM *182350), located on chromosome 19q13.2 and classified as ‘pathogenic’ according to CLINVAR (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/)39, was detected in two (SH191-430 and SH222-518) of the three ANSD subjects (Fig. 2). This variant was not detected from unaffected parents, indicating a de novo occurrence of an autosomal dominant variant, p.E818K, in both families (families SH191 and SH222) (Fig. 2). The paternity in these two families was confirmed by genotyping the four short tandem repeat (STR) markers, ensuring a de novo occurrence of p.E818K (Fig. 2). This p.E818K variant has previously been reported in a known CAPOS syndrome, comprising of cerebellar ataxia, areflexia, pes cavus, optic atrophy, and SNHL27–30. This variant has not been detected in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC; 121,412 alleles) and the Korean Reference Genome Database (KRGDB; 1,244 alleles). However, in the SB284 family, no convincing variants were found.

Figure 2.

De novo occurrence of the causative variant. De novo occurrence of p.E818K of ATP1A3 in families SH191 and SH222 is shown. Sanger sequencing traces of parents and probands are all provided. None of the parents (SH191-438, 431 and SH222-519, 520) from two families carry the variant residue, while the single heterozygous variant is noticed from both probands (SH191-430 and SH222-518). The results from reconstructed haplotypes derived from genotype results of four STR markers exclude non-paternity in families SH191 and SH222.

Detailed medical history and clinical phenotype of three ANSD subjects

The first proband (SH191-430) was a 24-year-old woman that manifested SNHL when she was a teenager. Her SNHL was compatible with typical ANSD, as shown in Fig. 1a. Her pure tone audiogram (PTA) showed a reverse sloping configuration. Temporal bone computed tomography (TBCT) and internal auditory canal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed that she had an intact cochlear nerve without any other anatomical abnormalities. She–along with her mother–denied any neurologic episodes, such as dystonia, ataxia, and visual disturbance. Detailed neurologic examination by an experienced neurologist confirmed the absence of co-morbid neuropathy, except for nearly absent deep tendon reflex (DTR). A detailed fundus examination and visual acuity test of SH191-430 did not reveal any abnormality, and SH191-430 refused to take visual evoked potentials (VEP). Until further examination, her SNHL had been classified as non-syndromic ANSD.

The second proband (SH222-518) was a 6-year-old boy when he first visited the ENT clinic. He successfully passed the newborn hearing screening test, which was performed with automated ABR, suggesting that his SNHL was not congenital. His development had not been noteworthy, except his experience of two acute episodes of neurologic symptoms and signs, including lethargy, instability while sitting, ataxia, dysarthria, visual disturbance with dancing nystagmus, and hearing loss after febrile illness at the age of 3 and 5 years. His SNHL was entirely compatible with ANSD, considering a detectable OAE response without ABR response (Fig. 1b). At that time, the findings from cerebrospinal fluid tapping and MRI were normal. He recovered steadily from all symptoms with minimal neurologic sequelae, mild temporal pallor in color fundus photography (Supplementary Fig. S1), and normal response in VEP. However, his SNHL deteriorated over time.

The third proband (SB284-563) was a 61-year-old female. Her SNHL started in her early thirties. Like the first proband, she did not have any neurologic abnormalities, except hearing loss. She had moderate hearing loss on PTA, 45 dB on the right and 40 dB on the left, with a disproportionately low word recognition score of 20%, bilaterally. In line with this finding, she showed a detectable ABR wave only at 90 dB stimulus on the right ear, despite the presence of a positive OAE response back in 2014, which indicated that her SNHL was compatible with ANSD. Two years later, both her OAE and ABR responses disappeared (Fig. 1c).

The neurologic features of these three ANSD subjects are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview neurologic features of three probands related with CAPOS syndrome.

| Subject | SH191-430 | SH222-518 | SB284-563 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | M | F |

| Current age | 24 | 6 | 61 |

| Onset of hearing difficulty | 10’s | 3 years | 30’s |

| CAPOS related feature at acute episode | |||

| - Age at episodes | − | 3 and 5 years | − |

| - Trigger | − | fever | − |

| - Ataxia | − | + | − |

| - Abnormal eye movement | − | + (opsoclonus) | − |

| - Dysarthria | − | + | − |

| - Dysmetria | − | + | − |

| - Dysphagia | − | − | − |

| - Visual disturbance | − | + | − |

| - Tremor | − | − | − |

| - Seizure | − | − | − |

| Findings at latest examination | |||

| - Gait | normal | slightly ataxic | normal |

| - Areflexia | + | + | − |

| - SSEP (somatosensory evoked potential) | normal | (not available) | normal |

| - NCS (nerve conduction velocity) | normal | normal | normal |

| - Pes cavus | − | − | − |

| - Optic atrophy | − | + | − |

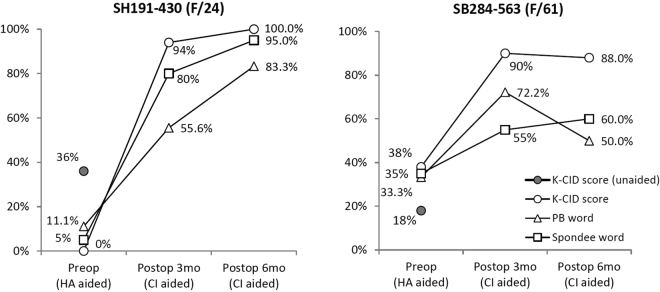

Short term follow-up results after cochlear implantation

Two adult ANSD subjects (SH191-430 and SB 284-563) underwent cochlear implantation (CI) since they were unable to benefit from hearing aids. The first subject (SH191-430) had the highest difficulty in speech discrimination with hearing aid, especially with background noise. She scored worse on the Korean version of the Central Institute of Deafness (K-CID) test with hearing aid, which decreased from 36% without hearing aid to 0% with hearing aid. Both subjects had CI on the right ear after getting replicable, albeit not perfect, waveforms on trans-tympanic electrically evoked ABR (EABR) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Both subjects showed striking progress in speech recognition, scoring 90–94% on K-CID without visual cue at 3 months postoperatively (Fig. 3). Evaluation of the speech performance at 6 months postoperatively displayed continuous improvement in this subject (SH191-430) carrying p.E818K of ATP1A3 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Pre- and postoperative cochlear implant speech performance. Both cochlear implantees show markedly increased performance on speech evaluation with K-CID as well as on PB and spondee word scores during the first three postoperative months. SH191-430 continues to display improvement in speech performance over the next three months, while improvement of SB284-563 slows down during the period. (K-CID Korean version of the Central Institute of Deafness; PB word phonetically balanced word; HA hearing aid; CI cochlear implant).

Discussion

The etiologies of ANSD are highly diverse; approximately 40% of cases have an underlying genetic basis5, whereas relatively a small number of variants has been evaluated to cause postlingual ANSD. We, for the first time, discovered that a de novo variant of ATP1A3 could be a prevalent and important etiology of sporadic ANSD with postlingual onset.

The ATP1A3 gene has been reported mainly in association with alternating hemiplegia of childhood (AHC, AHC2, OMIM #614820) and rapid-onset dystonia Parkinsonism (RDP, DYT12, OMIM #128235)35,40–42. Among various ATP1A3 mutations, two variants, p.D810N and p.E815K, have been found recurrently in more than 50% of patients with AHC, while no distinct mutations have been found in patients with RDP35. A different variant of this gene, p.E818K (c.2452 G > A), which has not been detected in the context of two main diseases associated with ATP1A3, has been reported to cause the third allelic disorder, CAPOS syndrome without exception in several reports31–37. CAPOS syndrome was first described in 1996 by Nicolaides et al. in a British family43. To date, this single variant has been identified exclusively from all nine unrelated CAPOS families, as described previously with 100% frequency. Unlike the previous two diseases, SNHL with sudden onset and progressive nature is a distinctive disabling feature of CAPOS syndrome. However, there has not been a rigorous study on the type of SNHL thus far.

The second subject, SH222-518, had passed the newborn hearing screening test by automated ABR; however, his hearing impairment was initiated and became prominent with a definite progression through two febrile events. Together with accompanying symptoms and signs, such as ataxia and visual disturbance, the detection of p.E818K in ATP1A3 led to the diagnosis of CAPOS syndrome. Different variants of this gene have been reported to cause RDP and AHC, without the companion of hearing or visual disturbance31,35. On the other hand, the first subject, SH191-430, who shared the same p.E818K variant, denied any neurological symptoms, except areflexia that was elucidated only after a rigorous neurological examination by an expert neurologist. This subject would have been classified as non-syndromic without a comprehensive neurologic examination by an expert. This is not surprising considering that there have been some reports showing subjects with CAPOS syndrome exhibiting mild symptoms resulting in recovery with minimal residual ataxia during walking and standing on one foot31. This implicates that extensive history taking and rigorous neurologic examination would be an essential part in the diagnosis of postlingual and progressive ANSD.

Our present study reports the tenth CAPOS family (SH222) and the 27th CAPOS patient (SH222-518) in the literature. This is the first report of a CAPOS allele in Koreans. High mutability of this residue, as shown by frequent de novo occurrence of p.E818K (c.2452 G > A) of ATP1A3 both in Caucasians31 and in Koreans, indicates that the effect of this mutational hotspot is not limited to certain populations but would rather be global. This is noteworthy because other allelic disorder of ATP1A3, RDP, has also been reported to be frequently caused by de novo variants44. Indeed, with the advent of next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, recent studies using NGS have elucidated the important role of de novo variants in several important neurological disorders45–47. To date, it is unclear exactly why de novo variants frequently arise in ATP1A3. Recently, the rate of de novo mutations has been reported to be heavily influenced by the age of the father48; however, that study failed to account for all de novo cases. There might be a genetic context in ATP1A3 favoring the occurrence of de novo variants, awaiting further clarification. Our present study also unveils that a phenotypic spectrum related to p.E818K of ATP1A3 can be extended to include nearly non-syndromic postlingual ANSD, not limited to the canonical CAPOS syndrome.

ATP1A3 encodes the α3 catalytic subunit of Na+/K+ ATPase (NKA), which is a membrane-bound transporter using ATP to transport three Na+ outwards in exchange for two K+ into the cell, resulting in a negative transmembrane potential. Regarding the contribution of NKA on hearing, it has mainly been studied in relation to endocochlear potentials (EP). The inhibitors of NKA, such as ouabain, are known to reduce EP49,50. There are four α isoforms identified in vertebrates51,52. NKAα1 has been identified in the strial marginal cell, and NKAα2 in the lateral wall fibrocyte of the stria vascularis, which is the source of EP50,53. Indeed, heterozygous deletion of NKAα1 or NKAα2 in mice resulted in the reduction of EP and progressive, age-dependent hearing loss54. Accordingly, the ATP1A2 gene (encodes NAKα2), which has previously been reported to be the genetic cause of familial hemiplegic migraine type 2 (FHN2, OMIM #602481), has recently been reported to be associated with progressive hearing loss with migraine55. Specifically, co-segregation of a novel variant, c.571 G > A, in the ATP1A2 gene with migraine and hearing loss in a family was shown, although the pathogenic potential of the c.571 G > A variant was not confirmed. Contrastingly, the α3 isoform is rather neuron-specific, albeit being co-expressed with ubiquitous α1 in most neurons56–58. NKAα3 is known to play an important role in the rapid restoration of increased intracellular Na+ concentration after high neuronal activity in the nervous system56,59. Therefore, disrupted NKAα3 activity leads to a failure in regaining the resting membrane potential after excitatory activity, and it has been proposed to cause paroxysmal neurologic events observed in two main ATP1A3-related syndromes34,35,60. Several experimental studies evaluated the pump activity as well as the effect of pathologic variants of ATP1A3. They showed that these mutations caused a reduction in catalytic activity and a failure to generate pump current. This finding is consistent with the inability to bind to K+ ions and a reduction in the Na+ affinity for activating phosphorylation61.

Nonetheless, the exact role of NKAα3 in hearing and how mutations in ATP1A3 cause hearing loss have not been fully elucidated to date. In a study focusing on the NKAα expression pattern in Organ of Corti and the neuronal element of cochlea, it has been demonstrated that NKAα3 is expressed abundantly in the membranes of type I afferent terminals that are in contact with the inner hair cells, spiral ganglion somata, and medial efferent terminals contacting the outer hair cells50. NKAα1 has been identified in the supporting cells neighboring the inner hair cells, and NKAα2 has not been detected in either the organ of Corti or spiral ganglion50. This expression pattern of NKAα3 in the cochlea has been shown to be compatible with an observation in which perfusion of ouabain, a specific inhibitor of NKAα3 in the cochlea, directly administered through the round window in gerbil, resulted in a reduced or completely abolished compound action potential but did not reduce EP50,62,63. This suggests that NKAα3 may have a more direct role in the regulation of signal transmission in the synapses with hair cells and spiral ganglion cells, rather than having a contribution to generate EP. Therefore, it is possible for the alteration of NKAα3 to lead to the clinical and laboratory features compatible with ANSD.

ANSD is a heterogeneous disorder that may result from various etiologies and different lesion sites, ranging from the inner hair cells and synapses to auditory nerve and central cortex. Inherent from such pathologic characteristics of ANSD, the behavioral threshold measures are not consistent with other measures of auditory function, such as ABR and speech understanding scores. Furthermore, it poses a challenge when choosing an appropriate method of auditory rehabilitation and predicting the outcome4,64,65. Due to the uncertainties of outcomes after CI, it is important to select patients who are expected to have good results from CI. EABR is widely used to evaluate the integrity of auditory pathway and predict the outcome of CI66–68. Among the various subtypes of ANSD classified by their predominant lesion, auditory synaptopathy has been reported to have excellent CI results, and EABR is typically present in this subtype3,21,65,69–71. However, the interpretation of waveforms is somewhat subjective, and preoperative trans-tympanic EABR is not consistently reliable for predicting the outcome of CI72. It is not unprecedented to benefit significantly from CI even in cases without any detectable responses from both preoperative trans-tympanic and postoperative intracochlear EABR tests73,74. Therefore, genetic diagnosis that enables precise localization of the pathologic site in the auditory pathway has been recognized to be very important.

Mutations in the OTOF gene, a causative gene of auditory synaptopathy, may cause a dysfunction in Ca2+-triggered exocytosis of a neurotransmitter in the ribbon synapses of the inner hair cells75–77. Therefore, a direct electrical stimulation of the spiral ganglion cells with CI bypassing the main lesion can restore well-synchronized neural responses that propagate through the intact auditory nerve. Another ANSD with good results on CI is a syndromic ANSD accompanied by autosomal dominant optic atrophy (ADOA, OMIM #165500) due to OPA1 variations11,21,64. Although the specific function of the OPA1 gene regarding hearing has not been fully elucidated to date, detailed assessment with trans-tympanic electrocochleography and electrically-evoked response following CI indicated that the site of the lesion is at a terminal portion of auditory nerve fibers with the potential to progress proximally at advanced stages11. OPA1 mRNA and protein were found in the hair cells as well as in the neuronal fibers innervating the inner hair cells, ganglion cells of the cochlea, and vestibular organ78. This is significantly overlapped with the expression site of the ATP1A3 protein, NKAα3. Although the function of NKAα3 has not been fully revealed, we can postulate from the expression pattern of this protein that the main pathologic lesion site would be a synapse between the inner hair cells and the afferent nerve fibers, or at most spiral ganglion neurons. If the lesion is mainly the former, then we can expect good CI results, similar to the ANSD associated with OTOF and OPA1. In accordance with this expectation, one (SH191-430) of our two ANSD subjects carrying p.E818K (c.2452 G > A) of ATP1A3 underwent CI and showed excellent performance at 3 and 6 months after CI, although longer observation is needed (Fig. 3). The third subject (SB284-563), whose causative variants were not identified, also underwent CI and showed successful outcome. Therefore, it can be deduced that the main pathology of ANSD in this subject may be limited to either pre-synaptic area or synapsis itself, rather than the nerve itself or a more central lesion.

What merits further attention is that the ATP1A3 gene is expressed not only in the synapse, but also in the spiral ganglion. Although the spiral ganglion neuron is electrically simulated by CI, possible progressive degeneration of the spiral ganglion neuron could still occur due to a disruption in the function of ATP1A3. In such a case, the best functional outcome of CI observed at the short-term follow-up may decrease over time. Therefore, a continuous follow-up of CI over a longer period is mandatory. Conversely, earlier stimulation of the spiral ganglion cell neuron by CI may retard or attenuate the degeneration of the neuron. This perspective has already been applied for the interpretation of discrete CI outcomes related to mutations of TMPRSS3, which is a representative gene expressed in the spiral ganglion neuron79–81. The outcomes of CI performed earlier in life due to rapid loss of residual hearing caused by more pathologic TMPRSS3 mutations was favorable, while the result from late implantees carrying TMPRSS3 mutations was not as favorable as the expectation81. Given the similarity of the expression site between ATP1A3 and TMPRSS3, a long-term follow-up of CI performance is warranted to better determine if the current benefit from CI decreases over time.

The exact frequency of post-lingual onset ANSD is still unknown. The prevalence of ANSD has been reported mainly in pediatric groups, ranging from 2% to 15% of children with permanent SNHL82–86. Although the prevalence of ANSD among the post-lingual SNHL has not been reported separately, the proportion of adult patients among the entire ASND population has been mentioned in some studies. Sininger and Oba reported that 25% of ANSD patients experienced their first symptoms after the age of ten1; other studies by Starr et al. and Berlin et al. showed that in 12~20% of cases, onset was experienced in adulthood, most of whom had multiple neuropathies due to Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease2,87. In our present study, three patients (2.8%) out of 106 sporadic cases of postlingual moderate and more degree of SNHL were diagnosed with ANSD. This prevalence is markedly lower when compared with the pediatric group. It is likely that many post-lingual patients with hearing difficulty did not undergo enough audiological and electrophysiological tests to fully confirm ANSD. Moreover, this may be even further underestimated because OAE response, which was once considered a prerequisite, might have been absent or disappeared over time2,88–90. In our study, the disappearance of OAE response from the third subject, SB284–563, over a period of 2 years (Fig. 1) supports this speculation.

In our present study, the single de novo variant, p.E818K of ATP1A3, accounted for two of the three (2/3, 67%) postlingual-onset ANSD, suggesting that this specific variant of ATP1A3 could be a significant contributor to postlingual-onset ANSD, not only in Koreans but also in other populations. Moreover, an evaluation of postlingual-onset ANSD subjects should require a comprehensive neurologic examination and meticulous history taking to ensure that no episodes of ataxia and visual disturbance triggered by a fever go unnoticed. Molecular genetic testing of this particular variant, p.E818K of ATP1A3, can be helpful to delineate ANSD cases which are related to subtle cases of CAPOS syndrome.

Conclusions

Here, we showed that recurring de novo mutation of ATP1A3 can cause progressive ANSD with postlingual onset and with either absence or presence of syndromic features. This confirms that ATP1A3 is an important and prevalent causative gene for progressive ANSD with postlingual onset. The presence of this variant can potentially serve as not only an etiologic biomarker, but also as a prognostic biomarker that allows for the identification of a subset of postlingual-onset ANSD subjects who can significantly benefit from CI, at least during a short-term follow-up period.

Material and Methods

Ethical considerations and subject evaluation

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of Seoul National University Hospital (IRBY-H-0905-041-281) and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB-B-1007-105-402). Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study. Written informed consent for child participants was obtained from their parents or guardians. All methods in this study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Medical and developmental histories were collected for 106 sporadic patients recruited between 2010 and 2017, who showed postlingual-onset, moderate or higher degree of SNHL. Syndromic cases were excluded. The audiometric evaluation with PTA, OAE, and ABR were carried out for the clinical diagnosis of ANSD. Internal auditory canal MRI and TBCT were also performed to identify anatomically intact cochlear nerve and any other anatomical abnormalities related to hearing loss. Comprehensive neurologic evaluation was performed by a neurology specialist to see if there is any accompanied neuropathy. The diagnostic criteria for ANSD as described by Rapin et al. were applied; (1) understanding of speech worse than predicted from the degree of hearing loss on their behavioral audiograms; (2) recordable otoacoustic emissions and/or cochlear microphonic; and (3) absent or atypical auditory brain stem responses91.

Molecular genetic analysis

DNA preparation and whole-exome sequencing

Whole blood (10 ml) was obtained from two probands and, if possible, their siblings and parents for the segregation study. Genomic DNA samples were extracted from the peripheral blood via standard procedures, as previously described92, and were subjected to WES. A SureSelect 50 Mb Hybridization and Capture kit was used for WES, and sequencing was performed using a HiSeq2000. The read length for the paired-end reads was 100 bp.

Detection of single-nucleotide variants and insertion/deletion polymorphisms

The reads were aligned with the human genome reference sequence (hg19) as proposed by Burrows-Wheeler Aligner, version 0.7.593 with the “MEM” algorithm. We used SAMTOOLS version 1.2 for sorting and indexing the SAM/BAM files94. Picard-tools version 1.127 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard) was used to mark duplicates. We used the IndelRealigner and BaseRecalibrator from Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) version 3.1-395 based on known single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions/deletions (indels) from the Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (dbSNP, build138), Mills, and 1000 G gold standard indel b37 sites and 1000 G phase I indel b37 sites for realigning the reads and base recalibration. The targeted gene variants were called using the Unified Genotyper in GATK and also were recalibrated by GATK based on dbSNP138, Mills indels, HapMap, and Omni and filtered at 99.0 truth sensitivity level. Finally, we used ANNOVAR to annotate the variants96.

Filtering process to identify candidate variants

We went through the filtering process as previously described38. In brief, we selected the variants in the coding region and with allele frequencies of <0.01, which were reported in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC; 121,412 alleles; http://exac.broadinstitute.org) and the Korean Reference Genome database (KRGDB; 1,244 alleles; http://152.99.75.168/KRGDB). Then, we filtered out the variants reported in dbSNP138, but included flagged SNPs. We chose the variants that were matched with one of the three possible inheritance patterns that could be possible in the sporadic form of genetic hearing loss. They were filtered to discard any variants with false-positive results based on minor allele frequency (MAF) cut-off 97 and with variant allele frequency (VAF) of heterozygosity of less than 0.3; however, the criteria were selectively adjusted to be less than 0.1 when a variant was located in a homologous locus or a gene with a pseudogene or homologous between family members. Finally, the scores of SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/), PolyPhen2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) and GERP (http://mendel.stanford.edu/SidowLab/downloads/gerp/) and CLINVAR (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/)39 were used to assess the pathogenicity of candidates.

Confirmation of paternity

To exclude non-paternity, genotypes of four unlinked STR markers (D10S584, D10S1650, D10S606, and D10S1694) from family members were analyzed, using a previously described method98. The four STR markers were chosen because they were shown in a previous study to be hypervariable and informative among Koreans98. A definite haplotype was reconstructed based on the information from parental sample and siblings.

Data availability

All data, whether generated or analyzed during this study, were included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI15C1632 and HI17C0952 to B. Y. Choi).

Author Contributions

B.Y.C. and K.H. wrote the manuscript. B.Y.C., D.O., S.L., J.H.H., M.Y.K., H.P., J.L. and E.Y. performed the experiments. B.Y.C., K.H., C.L., M.K.P., N.K., W.P., J.M.K., J.W.K., J.H.C. and S.H.O. analyzed the data. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-16676-9.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sininger, Y. & Oba, S. In Auditory Neuropathy: a new perspective on hearing disorders (eds Yvonne Sininger & Arnold Starr) Ch. 2, 15–35 (Singular Thomson Learning, 2001).

- 2.Starr A, Picton TW, Sininger Y, Hood LJ, Berlin CI. Auditory neuropathy. Brain. 1996;119:741–753. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.3.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rance, G. & Starr, A. Pathophysiological mechanisms and functional hearing consequences of auditory neuropathy. Brain. 138, 3141–3158, doi:3110.1093/brain/awv3270. Epub2015 Oct 3112. (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Harrison, R. V., Gordon, K. A., Papsin, B. C., Negandhi, J. & James, A. L. Auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) and cochlear implantation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 79, 1980–1987, doi:1910.1016/j.ijporl.2015.1910.1006 Epub 2015 Oct 1917 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Manchaiah, V. K., Zhao, F., Danesh, A. A. & Duprey, R. The genetic basis of auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD). Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 75, 151–158. doi:110.1016/j.ijporl.2010.1011.1023. Epub2010 Dec 1021 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Yasunaga S, et al. A mutation in OTOF, encoding otoferlin, a FER-1-like protein, causes DFNB9, a nonsyndromic form of deafness. Nat Genet. 1999;21:363–369. doi: 10.1038/7693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varga R, et al. Non-syndromic recessive auditory neuropathy is the result of mutations in the otoferlin (OTOF) gene. Journal of medical genetics. 2003;40:45–50. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez-Ballesteros M, et al. Auditory neuropathy in patients carrying mutations in the otoferlin gene (OTOF) Hum Mutat. 2003;22:451–456. doi: 10.1002/humu.10274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delmaghani, S. et al. Mutations in the gene encoding pejvakin, a newly identified protein of the afferent auditory pathway, cause DFNB59 auditory neuropathy. Nat Genet. 38, 770–778. Epub 2006 Jun 2025. (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Cheng X, et al. Connexin 26 variants and auditory neuropathy/dys-synchrony among children in schools for the deaf. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;139:13–18. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santarelli, R. et al. Audiological and electrocochleography findings in hearing-impaired children with connexin 26 mutations and otoacoustic emissions. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 265, 43–51. Epub 2007 Aug 2014. (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Thyagarajan D, et al. A novel mitochondrial 12SrRNA point mutation in parkinsonism, deafness, and neuropathy. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:730–736. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200011)48:5<730::AID-ANA6>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Q, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of a Chinese patient with auditory neuropathy associated with mitochondrial 12S rRNA T1095C mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;133A:27–30. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Ballesteros, M. et al. A multicenter study on the prevalence and spectrum of mutations in the otoferlin gene (OTOF) in subjects with nonsyndromic hearing impairment and auditory neuropathy. Hum Mutat. 29, 823–831, doi:810.1002/humu.20708 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Chang, M. Y. et al. Refinement of Molecular Diagnostic Protocol of Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder: Disclosure of Significant Level of Etiologic Homogeneity in Koreans and Its Clinical Implications. Medicine (Baltimore). 94, e1996, doi:1910.1097/MD.0000000000001996 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Kovach MJ, et al. A unique point mutation in the PMP22 gene is associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and deafness. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1580–1593. doi: 10.1086/302420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starr, A. et al. Pathology and physiology of auditory neuropathy with a novel mutation in the MPZ gene (Tyr145->Ser). Brain. 126, 1604–1619, Epub 2003 May 1606 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Satya-Murti S, Cacace A, Hanson P. Auditory dysfunction in Friedreich ataxia: result of spiral ganglion degeneration. Neurology. 1980;30:1047–1053. doi: 10.1212/WNL.30.10.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez-Diaz-de-Leon E, Silva-Rojas A, Ysunza A, Amavisca R, Rivera R. Auditory neuropathy in Friedreich ataxia. A report of two cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67:641–648. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(03)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brookes, J. T. et al. Cochlear implantation in deafness-dystonia-optic neuronopathy (DDON) syndrome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 72, 121-126. Epub 2007 Oct 2015. (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Huang, T., Santarelli, R. & Starr, A. Mutation of OPA1 gene causes deafness by affecting function of auditory nerve terminals. Brain Res. 1300:97–104., 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.1008.1083. Epub2009 Sep 1013 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Namba K, et al. Molecular Impairment Mechanisms of Novel OPA1 Mutations Predicted by Molecular Modeling in Patients With Autosomal Dominant Optic Atrophy and Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder. Otology & neurotology: official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2016;37:394–402. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang QJ, et al. AUNX1, a novel locus responsible for X linked recessive auditory and peripheral neuropathy, maps to Xq23-27.3. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e33. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.037929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zong, L. et al. Mutations in apoptosis-inducing factor cause X-linked recessive auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder. J Med Genet. 52, 523–531, doi:510.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102961. Epub 102015 May 102918 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Kim TB, et al. A gene responsible for autosomal dominant auditory neuropathy (AUNA1) maps to 13q14-21. J Med Genet. 2004;41:872–876. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.020628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoen, C. J. et al. Increased activity of Diaphanous homolog 3 (DIAPH3)/diaphanous causes hearing defects in humans with auditory neuropathy and in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA107, 13396–13401, doi:13310.11073/pnas.1003027107. Epub 1003022010 Jul 1003027112 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Seal, R. P. et al. Sensorineural deafness and seizures in mice lacking vesicular glutamate transporter 3. Neuron. 57, 263–275, doi:210.1016/j.neuron.2007.1011.1032. (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Ruel, J. et al. Impairment of SLC17A8 encoding vesicular glutamate transporter-3, VGLUT3, underlies nonsyndromic deafness DFNA25 and inner hair cell dysfunction in null mice. Am J Hum Genet. 83, 278–292, doi:210.1016/j.ajhg.2008.1007.1008 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Thirlwall AS, Brown DJ, McMillan PM, Barker SE, Lesperance MM. Phenotypic characterization of hereditary hearing impairment linked to DFNA25. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:830–835. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.8.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryu, N. et al. Screening of the SLC17A8 gene as a causative factor for autosomal dominant non-syndromic hearing loss in Koreans. BMC Med Genet. 17:6, 10.1186/s12881-12016-10269-12883 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Demos MK, et al. A novel recurrent mutation in ATP1A3 causes CAPOS syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosewich, H., Weise, D., Ohlenbusch, A., Gartner, J. & Brockmann, K. Phenotypic overlap of alternating hemiplegia of childhood and CAPOS syndrome. Neurology. 83, 861–863, doi:810.1212/WNL.0000000000000735. Epub 0000000000002014 Jul 0000000000000723 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Heimer, G. et al. CAOS-Episodic Cerebellar Ataxia, Areflexia, Optic Atrophy, and Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Third Allelic Disorder of the ATP1A3 Gene. J Child Neurol. 30, 1749–1756, doi:1710.1177/0883073815579708. Epub0883073815572015 Apr 0883073815579720 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Potic, A., Nmezi, B. & Padiath, Q. S. CAPOS syndrome and hemiplegic migraine in a novel pedigree with the specific ATP1A3 mutation. J Neurol Sci. 358, 453–456, doi:410.1016/j.jns.2015.1010.1002. Epub2015 Oct 1013 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Sweney, M. T., Newcomb, T. M. & Swoboda, K. J. The expanding spectrum of neurological phenotypes in children with ATP1A3 mutations, Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood, Rapid-onset Dystonia-Parkinsonism, CAPOS and beyond. Pediatr Neurol. 52, 56–64, 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.1009.1015. Epub2014 Oct 1013 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Maas, R. P., Schieving, J. H., Schouten, M., Kamsteeg, E. J. & van de Warrenburg, B. P. The Genetic Homogeneity of CAPOS Syndrome: Four New Patients With the c.2452G > A (p.Glu818Lys) Mutation in the ATP1A3 Gene. Pediatr Neurol. 59:71–75.e1, 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2016.1002.1010. Epub 2016 Mar 1017 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Duat Rodriguez, A. et al. Early Diagnosis of CAPOS Syndrome Before Acute-Onset Ataxia-Review of the Literature and a New Family. Pediatr Neurol. 71:60–64, 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.1001.1009. Epub2017 Jan 1025 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Kim NK, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals diverse modes of inheritance in sporadic mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss in a pediatric population. Genetics in medicine: official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2015;17:901–911. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Landrum MJ, et al. ClinVar: public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44:D862–868. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozelius, L. J. Clinical spectrum of disease associated with ATP1A3 mutations. Lancet Neurol. 11, 741–743, doi: 710.1016/S1474-4422(1012)70185-70180. Epub72012 Aug 70182 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Rosewich, H. et al. The expanding clinical and genetic spectrum of ATP1A3-related disorders. Neurology. 82, 945–955, doi:910.1212/WNL.0000000000000212. Epub 0000000000002014 Feb 0000000000000212 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Panagiotakaki, E. et al. Clinical profile of patients with ATP1A3 mutations in Alternating Hemiplegia of Childhood-a study of 155 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 10:123, 10.1186/s13023-13015-10335-13025 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Nicolaides P, Appleton RE, Fryer A. Cerebellar ataxia, areflexia, pes cavus, optic atrophy, and sensorineural hearing loss (CAPOS): a new syndrome. Journal of medical genetics. 1996;33:419–421. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.5.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Post B, Tijssen OL. MAJ. Juvenile rapid-onset dystonia parkinsonism due to a ‘de novo’ mutation in the ATP1A3 gene. J Pediatr Neurol. 2009;7:171–173. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gauthier, J. & Rouleau, G. A. De novo mutations in neurological and psychiatric disorders: effects, diagnosis and prevention. Genome Med. 4, 71, 10.1186/gm1372. eCollection 2012 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Riant, F. et al. De novo mutations in ATP1A2 and CACNA1A are frequent in early-onset sporadic hemiplegic migraine. Neurology. 75, 967–972, doi:910.1212/WNL.1210b1013e3181f1225e1218f (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.DeJesus-Hernandez M, et al. De novo truncating FUS gene mutation as a cause of sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Human mutation. 2010;31:E1377–1389. doi: 10.1002/humu.21241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kong, A. et al. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father’s age to disease risk. Nature. 488, 471–475, doi:410.1038/nature11396 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Konishi T, Mendelsohn M. Effect of ouabain on cochlear potentials and endolymph composition in guinea pigs. Acta oto-laryngologica. 1970;69:192–199. doi: 10.3109/00016487009123353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLean, W. J., Smith, K. A., Glowatzki, E. & Pyott, S. J. Distribution of the Na,K-ATPase alpha subunit in the rat spiral ganglion and organ of corti. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 10, 37–49, 10.1007/s10162-10008-10152-10169. Epub12008 Dec 10112 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Blanco G, Mercer RW. Isozymes of the Na-K-ATPase: heterogeneity in structure, diversity in function. The American journal of physiology. 1998;275:F633–650. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.5.F633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vergara, M. N., Smiley, L. K., Del Rio-Tsonis, K. & Tsonis, P. A. The alpha1 isoform of the Na+/K+ ATPase is up-regulated in dedifferentiated progenitor cells that mediate lens and retina regeneration in adult newts. Exp Eye Res. 88, 314–322, doi: 310.1016/j.exer.2008.1007.1014. Epub 2008 Aug 1018 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Wangemann, P. Supporting sensory transduction: cochlear fluid homeostasis and the endocochlear potential. J Physiol. 576, 11–21. Epub 2006 Jul 2020 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Diaz, R. C. et al. Conservation of hearing by simultaneous mutation of Na,K-ATPase and NKCC1. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 8, 422–434. Epub 2007 Aug 2004. (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Oh, S. K. et al. A missense variant of the ATP1A2 gene is associated with a novel phenotype of progressive sensorineural hearing loss associated with migraine. Eur J Hum Genet. 23, 639–645, doi:610.1038/ejhg.2014.1154. Epub2014 Aug 1020 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Azarias, G. et al. A specific and essential role for Na,K-ATPase alpha3 in neurons co-expressing alpha1 and alpha3. J Biol Chem. 288, 2734–2743, doi:2710.1074/jbc.M2112.425785. Epub 422012 Nov 425729 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Hieber V, Siegel GJ, Fink DJ, Beaty MW, Mata M. Differential distribution of (Na, K)-ATPase alpha isoforms in the central nervous system. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1991;11:253–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00769038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McGrail KM, Phillips JM, Sweadner KJ. Immunofluorescent localization of three Na,K-ATPase isozymes in the rat central nervous system: both neurons and glia can express more than one Na,K-ATPase. J Neurosci. 1991;11:381–391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00381.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akkuratov, E. E. et al. Functional Interaction Between Na/K-ATPase and NMDA Receptor in Cerebellar Neurons. Mol Neurobiol. 52, 1726–1734, doi:1710.1007/s12035-12014-18975-12033. Epub12014 Nov 12038 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Benarroch, E. E. Na+, K+ -ATPase: functions in the nervous system and involvement in neurologic disease. Neurology. 76, 287–293, doi:210.1212/WNL.1210b1013e3182074c3182072f. (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Heinzen, E. L. et al. Distinct neurological disorders with ATP1A3 mutations. Lancet Neurol. 13, 503–514, doi:510.1016/S1474-4422(1014)70011-70010 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Schmiedt RA, Okamura HO, Lang H, Schulte BA. Ouabain application to the round window of the gerbil cochlea: a model of auditory neuropathy and apoptosis. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology: JARO. 2002;3:223–233. doi: 10.1007/s1016200220017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang LE, Cao KL, Yin SK, Wang Z, Chen ZN. Cochlear function after selective spiral ganglion cells degeneration induced by ouabain. Chin Med J (Engl). 2006;119:974–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moser, T. & Starr, A. Auditory neuropathy–neural and synaptic mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol. 12, 135–149, doi:110.1038/nrneurol.2016.1010 Epub2016 Feb 1019 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Rance, G. & Barker, E. J. Speech perception in children with auditory neuropathy/dyssynchrony managed with either hearing AIDS or cochlear implants. Otol Neurotol. 29, 179–182, doi:110.1097/mao.1090b1013e31815e31892fd (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Kim AH, et al. Role of electrically evoked auditory brainstem response in cochlear implantation of children with inner ear malformations. Otology & neurotology: official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2008;29:626–634. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31817781f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Walton, J., Gibson, W. P., Sanli, H. & Prelog, K. Predicting cochlear implant outcomes in children with auditory neuropathy. Otol Neurotol. 29, 302–309, doi:310.1097/MAO.1090b1013e318164d318160f318166 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Gibson WP, Sanli H. Auditory neuropathy: an update. Ear Hear. 2007;28:102S–106S. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3180315392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Breneman AI, Gifford RH, Dejong MD. Cochlear implantation in children with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder: long-term outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2012;23:5–17. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.23.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Starr A, et al. A dominantly inherited progressive deafness affecting distal auditory nerve and hair cells. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2004;5:411–426. doi: 10.1007/s10162-004-5014-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Santarelli R, et al. Presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms underlying auditory neuropathy in patients with mutations in the OTOF or OPA1 gene. Audiological Medicine. 2011;9:59–66. doi: 10.3109/1651386X.2011.558764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nikolopoulos TP, Mason SM, Gibbin KP, O’Donoghue GM. The prognostic value of promontory electric auditory brain stem response in pediatric cochlear implantation. Ear Hear. 2000;21:236–241. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200006000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mason JC, De Michele A, Stevens C, Ruth RA, Hashisaki GT. Cochlear implantation in patients with auditory neuropathy of varied etiologies. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:45–49. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200301000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jeon, J. H. et al. Relationship between electrically evoked auditory brainstem response and auditory performance after cochlear implant in patients with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder. Otol Neurotol. 34, 1261–1266, doi:1210.1097/MAO.1260b1013e318291c318632 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Beurg M, et al. Calcium- and otoferlin-dependent exocytosis by immature outer hair cells. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1798–1803. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4653-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roux I, et al. Otoferlin, defective in a human deafness form, is essential for exocytosis at the auditory ribbon synapse. Cell. 2006;127:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yasunaga, S. et al. OTOF encodes multiple long and short isoforms: genetic evidence that the long ones underlie recessive deafness DFNB9. Am J Hum Genet. 67, 591–600 Epub 2000 Jul 2019 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Bette, S., Zimmermann, U., Wissinger, B. & Knipper, M. OPA1, the disease gene for optic atrophy type Kjer, is expressed in the inner ear. Histochem Cell Biol. 128, 421–430. Epub 2007 Sep 2008 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Eppsteiner RW, et al. Prediction of cochlear implant performance by genetic mutation: the spiral ganglion hypothesis. Hearing research. 2012;292:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fasquelle, L. et al. Tmprss3, a transmembrane serine protease deficient in human DFNB8/10 deafness, is critical for cochlear hair cell survival at the onset of hearing. J Biol Chem. 286, 17383–17397, doi:17310.11074/jbc.M17110.190652. Epub 192011 Mar 190621 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Chung J, et al. A novel mutation of TMPRSS3 related to milder auditory phenotype in Korean postlingual deafness: a possible future implication for a personalized auditory rehabilitation. Journal of molecular medicine. 2014;92:651–663. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rance G. Auditory neuropathy/dys-synchrony and its perceptual consequences. Trends Amplif. 2005;9:1–43. doi: 10.1177/108471380500900102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodriguez Dominguez FJ, Cubillana Herrero JD, Canizares Gallardo N, Perez Aguilera R. [Prevalence of auditory neuropathy: prospective study in a tertiary-care center] Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2007;58:239–245. doi: 10.1016/S0001-6519(07)74920-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Foerst, A. et al. Prevalence of auditory neuropathy/synaptopathy in a population of children with profound hearing loss. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 70, 1415–1422. Epub 2006 Mar 1430. (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 85.Sanyelbhaa Talaat, H., Kabel, A. H., Samy, H. & Elbadry, M. Prevalence of auditory neuropathy (AN) among infants and young children with severe to profound hearing loss. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 73, 937–939, doi:910.1016/j.ijporl.2009.1003.1009. Epub2009 May 1015 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.Vignesh, S. S., Jaya, V. & Muraleedharan, A. Prevalence and Audiological Characteristics of Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder in Pediatric Population: A Retrospective Study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 68, 196–201, doi:110.1007/s12070-12014-10759-12076. Epub12014 Aug 12012 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Berlin CI, Hood LJ. & K., R. On renaming auditory neuropathy as auditory dys-synchrony: implications for a clearer understanding of the underlying mechanisms and management options. Audiol Today. 2001;13:15–17. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Berlin CI, Hood L, Morlet T, Rose K, Brashears S. Auditory neuropathy/dys-synchrony: diagnosis and management. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2003;9:225–231. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Deltenre P, et al. Auditory neuropathy with preserved cochlear microphonics and secondary loss of otoacoustic emissions. Audiology. 1999;38:187–195. doi: 10.3109/00206099909073022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Starr A, et al. Cochlear receptor (microphonic and summating potentials, otoacoustic emissions) and auditory pathway (auditory brain stem potentials) activity in auditory neuropathy. Ear Hear. 2001;22:91–99. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200104000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rapin I, Gravel J. “Auditory neuropathy”: physiologic and pathologic evidence calls for more diagnostic specificity. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2003;67:707–728. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(03)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim, S. Y. et al. Prevalence of p.V37I variant of GJB2 in mild or moderate hearing loss in a pediatric population and the interpretation of its pathogenicity. PloS one 8, e61592, 10.1371/journal.pone.0061592 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 25, 1754–1760, doi:1710.1093/bioinformatics/btp1324. Epub 2009 May 1718 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25, 2078–2079, doi: 2010.1093/bioinformatics/btp2352. Epub2009 Jun 2078 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303, doi:1210.1101/gr.107524.107110. Epub 102010 Jul 107519 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Wang, K., Li, M. & Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e164, doi:110.1093/nar/gkq1603. Epub 2010 Jul 1093 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.Shearer, A. E. et al. Utilizing ethnic-specific differences in minor allele frequency to recategorize reported pathogenic deafness variants. Am J Hum Genet. 95, 445–453, doi:410.1016/j.ajhg.2014.1009.1001. Epub2014 Sep 1025 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 98.Kim SY, et al. Strong founder effect of p.P240L in CDH23 in Koreans and its significant contribution to severe-to-profound nonsyndromic hearing loss in a Korean pediatric population. J Transl Med. 2015;13:263. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0624-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data, whether generated or analyzed during this study, were included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).