Abstract

Background and Aims: Angiogenesis is an important pathological process during progression of plaque formation, which can result in plaque hemorrhage and vulnerability. This study aims to explore non-invasive imaging of angiogenesis in atherosclerotic plaque through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) by using GEBP11 peptide targeted magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis.

Methods: The dual-modality imaging probe was constructed by coupling 2, 3-dimercaptosuccinnic acid-coated paramagnetic nanoparticles (DMSA-MNPs) and the PET 68Ga chelator 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N, N', N''-triacetic acid (NOTA) to GEBP11 peptide. The atherosclerosis model was induced in New Zealand white rabbits by abdominal aorta balloon de-endothelialization and atherogenic diet for 12 weeks. The plaque areas in abdominal artery were detected by ultrasound imaging and Oil Red O staining. Immunofluorescence staining and Prussian blue staining were applied respectively to investigate the affinity of GEBP11 peptide. MTT and flow cytometric analysis were performed to detect the effects of NGD-MNPs on cell proliferation, cell cycle and apoptosis in Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). In vivo MRI and PET imaging of atherosclerotic plaque were carried out at different time points after intravenous injection of nanoparticles.

Results: The NGD-MNPs with hydrodynamic diameter of 130.8 nm ± 7.1 nm exhibited good imaging properties, high stability, low immunogenicity and little cytotoxicity. In vivo PET/MR imaging revealed that 68Ga-NGD-MNPs were successfully applied to visualize atherosclerotic plaque angiogenesis in the rabbit abdominal aorta. Prussian blue and CD31 immunohistochemical staining confirmed that NGD-MNPs were well co-localized within the blood vessels' plaques.

Conclusion: 68Ga-NGD-MNPs might be a promising MR and PET dual imaging probe for visualizing the vulnerable plaques.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, GEBP11 peptide, Magnetic nanoparticles, Multimodality imaging.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality worldwide and 17.5 million people died from CVD in 2012, representing 31% of all global deaths 1. Atherosclerotic plaque rupture with thrombosis is responsible for the vast majority of heart attacks and strokes 2. The plaque stability is mainly determined by its macroscopic structure and microscopic composition 3. The vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque, characterized by immune cells infiltration, necrotic core, lipid pools, spotty calcification and intra-plaque neovascularization, is prone to rupture suddenly and cause a fatal event 4. Thus, there is a considerable need for early detecting and accurately stratifying patients with high risk of CVD.

The traditional anatomic imaging techniques such as X-ray angiography (CAG) or coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) can detect the plaque morphology and provide an ideal strategy for therapeutic interventions 5. Some advanced imaging modalities, including intravascular ultrasonography (IVUS) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are able to provide higher resolution images with in-depth analysis about plaque composition 6. All these techniques are more dependent on contrast analysis, rather than reflecting the cellular and molecular mechanism by which a stable plaque becomes more vulnerable 7. Molecular imaging provides an invaluable tool to identify the biological aspects of atherosclerotic plaque in real-time 8.

Pathological angiogenesis of the vessel wall is a consistent feature of atherosclerotic plaque development and progression of the disease 8, 9. The angiogenic microvessels not only provide an additional gateway for immune cells to infiltrate into plaques, but also lead to intraplaque hemorrhage 10, 11. A variety of studies demonstrate that increased density of plaque microvessel is an independent risk factor for plaque rupture and inhibition of plaque angiogenesis provides a therapeutic strategy to stabilize atherosclerotic lesions 12-14. Therefore, more effective targeting moieties are urgently needed for molecular imaging and targeted therapy of angiogenesis in atherosclerosis. We previously screened a nine-amino acid cyclic peptide (CTKNSYLMC, GEBP11) via phage display technology by co-culturing tumor cells SGC-7901 with Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) 15. GEBP11 peptide holds high affinity and specificity to neovascularization of endothelial cells and is of great value in monitoring angiogenesis processes in vivo 16-18. We hypothesized that GEBP11 peptide can serve as a target molecule for visualization of vulnerable plaque in vivo by monitoring the process of angiogenesis.

Herein, we conjugated GEBP11 peptide to Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles and radiolabeled with 68Ga. The physicochemical characteristics, magnetic properties, binding affinity and cytotoxicity of 68Ga-NGD-MNPs were investigated in this study. Positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance (MR) dual-modality imaging methods were applied to analyze 68Ga-NGD-MNPs distribution, pharmacokinetics and targeting efficacy in rabbit atherosclerotic model.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal studies were performed according to a protocol approved by the Chinese PLA General Hospital Animal Care and Use Committee. Thirty male New Zealand white rabbits, weighing ~3.0 kg were fed an atherogenic diet containing 1% cholesterol. After 3 weeks, the rabbits underwent abdominal aorta balloon de-endothelialization. Each rabbit was anesthetized using an intravenous mixture of ketamine (5 mg/kg) and xylazine (35 mg/kg) 19. A 5-Fr sheath was inserted into the right iliac artery and a 4.0 mm × 15 mm angioplasty balloon was advanced into the abdominal aorta. The balloon was inflated with a 50% mixture of contrast agent and saline and then pulled back three times at 14 atm. Rabbits were fed with atherogenic diet for additional 12 weeks prior to being divided into various study groups.

Twelve-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (Vital River, Beijing, China) were maintained in the PLA animal facility and used to detect the potential toxicity, biodistribution and immunogenicity of the nanoparticles, respectively.

Cell culture

The cell lines Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and EAhy926 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection center (Menassas, USA) and cultured in M200 basal culture medium supplemented with low serum growth supplement, obtained from Gibco biosciences (Grand Island, USA).

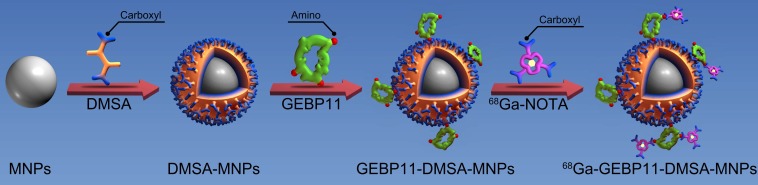

Preparation of NGD-MNPs

Firstly, Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) with average diameters between 8 nm and 12 nm were synthesized by thermal decomposition of iron (III) acetylacetonate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) in the presence of oleic and oleylamine as surfactant 20. Secondly, ligand exchange reaction of oleic acid for meso-2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) was adopted to transform hydrophobic MNPs into hydrophilic ones as reported previously 21. After that, GEBP11 peptide was attached to DSMA-MNPs via amide bond formation between the carboxyl of DMSA and amine group of GEBP11 peptide in the presence of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) 22. Briefly, 5 mg of EDC (10 mg/mL) and 5 mg NHS (10 mg/mL) were mixed in 10 mL aqueous solution of DMSA-MNPs (1 mg/mL) at room temperature. After 30 min, 12 mg GEBP11 (10 mg/mL) was slowly added to the mixture and the reaction solution was continuously stirred for 12 h at 4 ℃. The GEBP11-DMSA-MNPs were collected by centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 20 min and the supernatant was discarded. Finally, 1 mg of EDC (10 mg/mL), 0.5 mg NHS (10 mg/mL) and 1 mg NOTA (Macrocyclics, Dallas, USA) were mixed in 10 mL borate saline buffer (pH=8.4, 20 mg/mL) at room temperature. After 30 min, 5 mL GEBP11-DMSA-MNPs (1 mg/mL) were added. After 4 h at room temperature, the resultant NOTA-GEBP11-DMSA-MNPs (NGD-MNPs) were collected by centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 20 min and stored at 4 ℃. The surplus sample was lyophilized for long-term storage.

Radiolabeling with 68Ga

68GaCl3 (1110 MBq) was eluted from a 68Ge/68Ga generator using 0.05 M HCl. NGD-MNPs (1 mg) was dissolved in water (1 mg/mL) and 500 μL of 68GaCl3 (600 MBq) was added. Finally, we adjusted the pH to 3.7 using sodium acetate (1.25 M). Then, the reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The radiolabeling efficiency was measured by radio-thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using a 1:1 mixture of 10% ammonium acetate and methanol as the developing solvent system. The product was collected by centrifuging at 13,000 rpm for 5 min and sterilized through a 0.22 μm Millipore filter for later use 23.

Characterization of NGD-MNPs

The morphology and size distribution of DMSA-MNPs and NGD-MNPs were characterized by transmission electronic microscopy (TEM, JEM-2100, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. The hydrodynamic diameters and Zeta potentials of these particles were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS, Zetasizer Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK) equipped with 4 mW He-Ne laser (λ = 633 nm). The magnetic properties of powder samples were analyzed in a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM JDM-13, China).

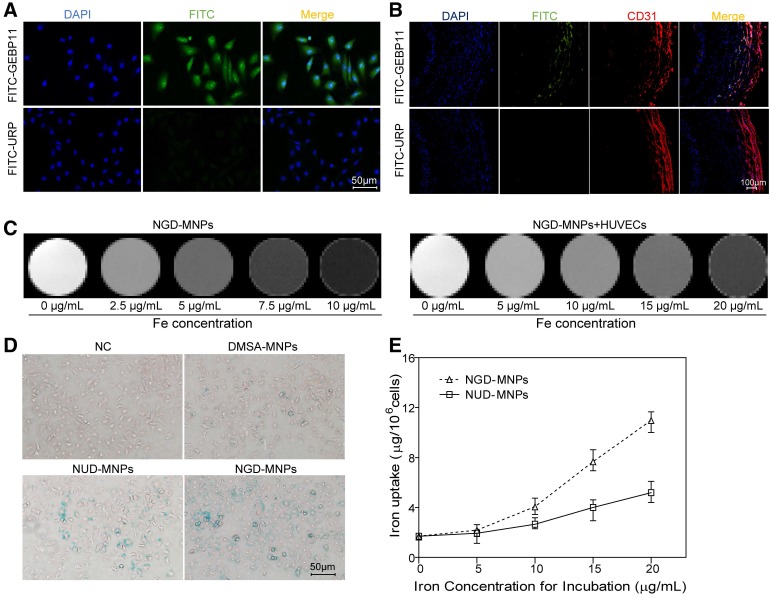

Immunofluorescence staining of GEBP11 in cells and plaque tissue

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and EAhy926 cells (ATCC, Rockville, USA) were prepared as described previously 24, 25. An in vitro cell chemical hypoxia model was established by adding 300 μM cobalt chloride (CoCl2) to culture medium and cells were harvested after 4 h. The binding affinity and specificity of GEBP11 were assessed by cell immunofluorescence studies. The cells, after hypoxia treatment, were incubated with FITC-GBPE11 (1 mg/mL) for 30 min, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and washed by PBS as described above. Nuclei were stained by 4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 3 min. The cells were imaged by a confocal fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) using filters specific for DAPI and FITC. An unrelated peptide (URP, CNLKNTHHC) was used as negative control.

The plaque tissue from rabbits before nanoparticle injection was processed routinely into paraffin and sectioned. The tissue sections were dewaxed, rehydrated and heat-induced antigen was retrieved in citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0). After incubating overnight with a goat anti-rabbit CD31 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and FITC-GEBP11 peptide at 4 °C, the slides were washed and incubated with DyLightTM 488-conjugated Donkey Anti-Mouse IgG as secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature. Nuclei were stained by 4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 3 min. The sections were imaged by an Olympus FV 10i confocal fluorescence microscope.

In vitro MR imaging

To determine the relaxivity, NGD-MNPs were diluted in 500 μL distilled water at various concentration levels (0, 2.5, 5, 7.5 and 10 μg/mL) and then transferred to 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. High resolution T2-weighted MRI scans were acquired using an 8-channel wrist joint coil on a 3.0 T MRI system (Siemens, Germany). The imaging parameters were as follows: field of view (FOV) 120 mm, base resolution 384 × 384, slice thickness 3 mm, multiple echo times (TE) 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140 ms, repetition time (TR) 2000 ms. T2 relaxation rates were plotted against iron concentrations in the particle dilutions. The relaxivity was determined by a linear fit.

Cell culture and cell MR imaging

To reveal the T2-signal decay value of the HUVECs treated with NGD-MNPs, 1×105 HUVECs were seed onto sterile 24-well plates and incubated overnight in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. When the cells reached 70-80% confluency, HUVECs chemical hypoxia model was prepared as described previously. Fresh M200 complete medium supplemented with different concentrations of NGD-MNPs (0, 5, 10, 15 and 20 μg/mL) were added to the culture plates. The cells were incubated with nanoparticles for 6 h and washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4). The cells were detached by trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), suspended in 500 μL 0.5% agarose gel and then transferred to 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. MR images were acquired using a 3.0 T MRI system with the same parameters mentioned above.

Prussian blue staining and iron uptake assay

To confirm the cellular uptake of nanoparticles, 1×106 HUVECs were incubated with NGD-MNPs at a concentration of 20 μg/mL for 6 h. The cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. After removing the fixative, 1 mL of solution containing 5 wt% potassium ferrocyanide and 10 vol% HCl were added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. After washing with distilled water three times, the cells were counterstained with nuclear fast red solution (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) for 3 min. Images were obtained under Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

The quantitative analysis of iron content internalized by HUVECs was determined by an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS, Shimadzu Corp, Kyoto, Japan). 1×106 HUVECs were treated with CoCl2 as described above and then incubated with nanoparticles (20 μg/mL) for 6 h. The cells were lysed with 200 μL of concentrated HCl and the lysate was transferred into a micro reaction tube. After an appropriate dilution of lysate with distilled water, intracellular iron content was measured by AAS.

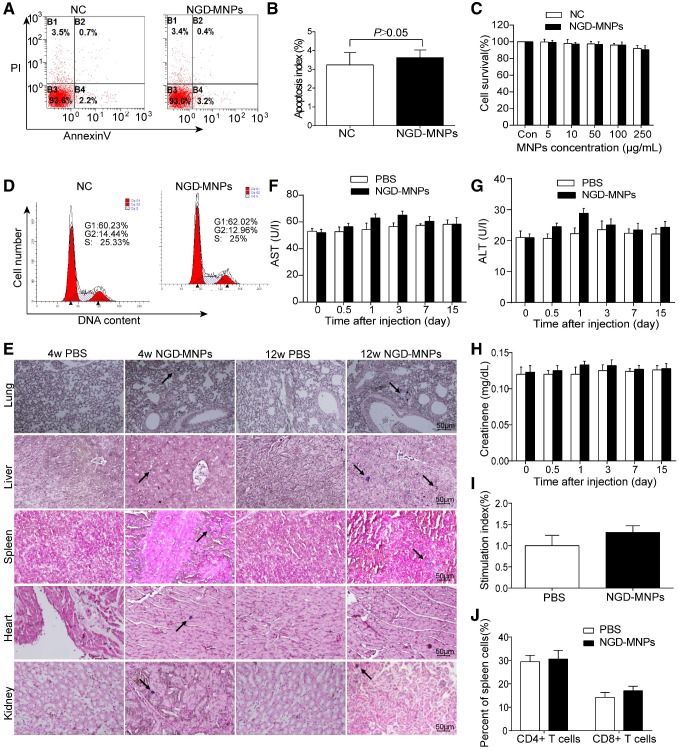

Cytotoxicity assay of nanoparticles

MTT assay was used for cell viability study. 1×104 HUVECs were seed in 96-well plates under different concentrations of NGD-MNPs (0, 5, 10, 50, 100 and 250 μg/mL). After 48 h incubation, the relative cell viability was assessed by MTT assay. 20 μL MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h. The formazan crystal was dissolved in 150 μL DMSO completely and then the plates were read on a Microplate Reader at 490 nm wavelength (TECAN, Switzerland).

The cell cycle and apoptosis were analyzed by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). 1×105 HUVECs were seed in sterile 24-well plates and incubated with NGD-MNPs at a concentration of 20 μg/mL for 48 h. Cells were washed with PBS, harvested with trypsinization and then treated with a set of reagents provided by the CycleTESTTM PLUS DNA Reagent Kit (BD biosciences, San Diego, USA). Nuclei were then stained with a 50 μg/mL PI solution for 30 min at 4 ℃ in the dark. The distributions of cell-cycle phases were analyzed by flow cytometry. Treated or untreated cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V (eBioscience, San Diego, USA) for the apoptosis tests.

Mice (n=3/group) received 4 intravenous injections of 200 μL PBS or NGD-MNPs (20 mg Fe/kg/injection) in two weeks. 4 weeks and 12 weeks after the last injection, mice were euthanized and the spleen, liver, lungs, heart and kidneys were harvested for histopathological analysis.

Mice (n=3/group) received a single intravenous injection of 100 μL PBS or NGD-MNPs (5 mg Fe/kg/injection). At several time points (0, 0.5, 1, 3, 7 and 15 day) after the administration of the NGD-MNPs, mice were euthanized and 3 mL blood sample was sent to the clinical laboratory of Xijing hospital for alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and creatinine assay.

Immunogenicity assay of nanoparticles

Mice (n=3/group) received 3 intravenous injections of 100 μL PBS or NGD-MNPs (5 mg Fe/kg/injection) every two weeks. Mice were euthanized 10 days after the last immunization 26. T lymphocyte proliferation was determined by the MTT assay. Briefly, 1×104 spleen cells isolated from the vaccinated mice were seeded in 96-well plates and stimulated with the NGD-MNPs (10 μg/mL) for 48 h. 20 μL MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h. The formazan crystal was dissolved in 150 μL DMSO completely, followed by measurement of the optical density (OD) value using a microplate reader. The stimulation index (SI) was calculated as follows: SI = (OD of stimulated culture)/(OD of unstimulated culture). SI > 2 was considered significant 27.

Relative proportions of CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells in the spleen cells of mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. Briefly, 1×106 splenocytes were cultured in complete RPMI-1640 alone or co-cultured with NGD-MNPs (10 μg/mL) for 4 h. 10 μL of FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD8 antibody (Ebioscience, San Diego, USA) and PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD4 antibody (Ebioscience, San Diego, USA) were incubated with the spleen cells in a 200 μL volume for 20 min at room temperature. The spleen cells were washed twice with PBS and resuspended in 500 μL PBS for flow cytometry.

Blood retention time and biodistribution of nanoparticle

Mice (n=3/group) received a single intravenous injection of 100 μL NGD-MNPs (5 mg Fe/kg/injection). At different time points (0.1, 2, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h) after the injection, 3 mL of blood sample was collected to obtain serum immediately. Then iron contents in serum were determined by a fast sequential AAS (Shimadzu Corp, Kyoto, Japan) and analyzed to calculate a half-life period.

Mice (n=3/group) received a single intravenous injection of 100 μL PBS or NGD-MNPs (5 mg Fe/kg/injection). At several time points (0.5, 7 and 15 days) after the injection, mice were euthanized and the spleen, liver, lungs and kidneys were harvested for Prussian blue staining analysis.

Intravascular and ultrasound imaging

IVUS was carried out after administration of 20 μg nitroglycerin using a 40 MHz catheter (Atlantis SR Pro, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) and an automatic pullback device at 0.5 mm/s. All IVUS images were obtained at 30 frames/s and recorded on high-resolution super VHS videotapes.

In vivo PET/MR imaging

PET/CT scans were performed on a Biograph 64 HR PET-CT (Siemens, Germany). 68Ga-NGD-MNPs or 68Ga-NUD-MNPs (52.4 MBq in 500 μL) were respectively injected into rabbits under anesthesia via a marginal ear vein. A 10 min static scan was acquired at 60 min. The images were reconstructed by a two-dimensional ordered-subsets exception maximum algorithm. For each PET/CT scan, regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn over the vassal wall, muscle, liver and kidneys on the decay-corrected whole-body coronal images.

MRI was performed on the 3.0 T MRI system with a knee coil before and 4 h after intravenous administration of NGD-MNPs (5 mg Fe/kg body weight). The parameters were as follows: field of view (FOV) 80 mm, base resolution 192 × 192, slice thickness 1 mm, multiple echo times (TE) 114 ms, repetition time (TR) 3500 ms. The T2-weighted signal change of the plaque was calculated by using the following formula: (SIpre-SIpost)/SIpre × 100%, where SIpre and SIpost were the signal intensity of the plaque before and after administration of the nanoparticles, respectively.

Histology staining

After the MR images were acquired, the plaque tissues were processed routinely into paraffin and sectioned. The tissue sections were dewaxed, rehydrated and heat-induced antigen was retrieved in citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0). After incubation overnight with goat anti-rabbit CD31 primary antibody (dilution 1:100) at 4 °C, the slides were washed and incubated with mouse anti-goat IgG (dilution 1:200, Zymed) as secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature. After washing again with PBS, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin (Zymed) was incubated for 10 min. Subsequently, CD31 location was visualized by 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution for 3 min and counterstained by hematoxylin for 2 min. Then tissues were dehydrated, mounted and photographed for Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) evaluation. Prussian blue staining was performed to the serial sections as described above.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). SPSS17.0 (SPSS Inc, USA) and Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, USA) were used to perform the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A two-tailed P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characterization of nanoparticles

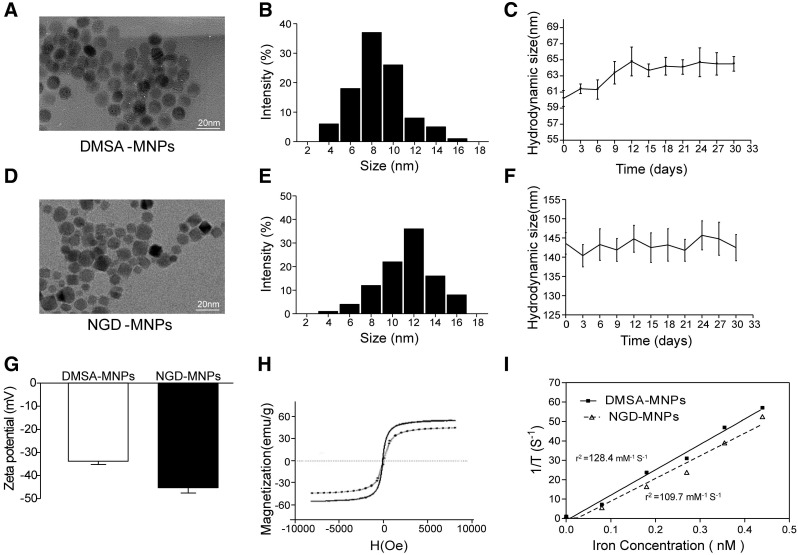

The schematic structures of 68Ga-GEBP11-DMSA-MNPs are shown in Fig. 1. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showed DMSA-MNPs and NGD-MNPs with average iron core sizes of 10 nm and 12 nm, respectively (Fig. 2A, D). Both the DMSA-MNPs and NGD-MNPs had a narrow size range (Fig. 2B, E). The results of DLS revealed that the NGD-MNPs dispersed in distilled water had a hydrodynamic diameter of 130.8 nm ± 7.1 nm, larger than 63.2 ± 4.1 nm of the DMSA-MNPs (Fig. 2C, F). Zeta potential of MNPs was -33.7 ± 1.5 mV, which changed to -45.2 mV ± 2.3 mV after coupling with NOTA (Fig. 2G). The magnetic properties of DMSA-MNPs and NGD-MNPs measured by VSM showed that the two kinds of particles were superparamagnetic and the saturation magnetization of DMSA-MNPs was 58.1 emu/g, larger than 47.6 emu/g of NGD-MNPs (Fig. 2H). The relaxivity (r2) of NGD-MNPs was calculated to be 109.7 mM-1s-1, slightly lower than that of DMSA-MNPs (128.4 mM-1s-1) (Fig. 2I). The MRI results showed that the T2 relaxation time was significantly affected by NGD-MNPs and there was a strong linear correlation between the nanoparticle concentration and the signal intensity change. As expected, HUVECs treated with NGD-MNPs showed a gradual MR signal decay with increasing concentration of iron (Fig. 3C).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram depicting the structure and manufacture of 68Ga-NOTA-GEBP11-DMSA-MNPs (68Ga-NGD-MNPs).

Figure 2.

The characterizations of MNPs. (A, D) TEM micrograph (the scale bar is 20 nm). (B, E) The size distribution of MNPs. (C, F) The hydrodynamic diameters and dispersive stability of MNPs measured by DLS. (G) The zeta potential of MNPs measured by DLS. (H) The magnetization curves of MNPs. (I) The relaxivities (r2) of MNPs.

Figure 3.

The binding affinity of GEBP11 peptide and NGD-MNPs to HUVECs. (A) Immunofluorescence images of FITC-labeled GEBP11 peptide or un-related peptide (URP) incubated HUVECs (the scale bar is 50 μm). (B) Confocal images showing GBEP11 peptide ligand and CD31 expression in plaque region (the scale bar is 100 μm). (C) The T2 weighted MR images of NGD-MNPs or HUVECs after incubation with NGD-MNPs at various iron concentrations. (D) Prussian blue staining images of HUVECs after incubation with MNPs (the scale bar is 50 μm). (E) Iron uptake curves of HUVECs.

Cellular uptake of nanoparticles

The targeting ability of GEBP11 peptide was examined by confocal laser microscopy. Fluorescence signals from cellular cytoplasm could be easily detected in HUVECs (Fig. 3A). In addition, we found high binding affinity of GEBP11 peptide to EAhy926 cells after hypoxia treatment by immunofluorescence staining study (Fig. S1). GEBP11 peptide was well co-localized with CD31-positive plaque neovascularization and vasa vasorum in the plaque section (Fig. 3B). After Prussian blue staining, the intra-cytoplasmic inclusions containing MNPs presented as dense blue stained vesicles under light microscopy. Prussian blue staining results showed that the iron uptake of HUVECs increased significantly in NGD-MNPs group compared with that in DMSA-MNPs group or unrelated peptide control group (NRD-MNPs) (Fig. 3D). The quantitative evaluation of the cellular uptake of MNPs is in agreement with that observed with Prussian blue staining and the cellular iron loading increased with the dosage of MNPs (Fig. 3E).

Cytotoxicity assay of nanoparticles

Intracellular nanoparticle accumulation might induce cell death or apoptosis. TUNEL staining result revealed that there was no significant increase in cell apoptosis between NGD-MNPs group and negative control group (3.9% vs 3.0%, P > 0.05) (Fig. 4A, B). MTT assay demonstrated that the HUVECs incubated with different concentrations (5, 10, 50, 100 and 250 μg/mL) of NGD-MNPs exhibited no significant difference in cell viability compared with negative control groups (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4C). It is clear that NGD-MNPs produced no significant effect on cell cycle of HUVECs after 48 h treatment (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4D). Prussian blue staining of major organs showed iron agglomeration at 1 and 3 months after multiple dose administration of NGD-MNPs, but we found no structural or histopathological changes in any of the tissues (Fig. 4E). We found transient and moderate increases in ALT, AST and creatinine levels 1 day after NGD-MNPs injection as compared to controls, while the levels nearly fell back to baseline at 15 days post-treatment (Fig. 4F, G and H).

Figure 4.

Biocompatibility and immunogenicity of NGD-MNPs. (A) The flow cytometry assay and (B) the apoptosis index of HUVECs after incubation with NGD-MNPs. (C) The cell viability of HUVECs after incubation with NGD-MNPs at various iron concentrations. (D) The cell cycle of HUVECs after incubation with NGD-MNPs. (E) Representative Prussian blue staining of major visceral organs (heart, lungs, liver, spleen and kidneys) harvested from mice at 4 or 12 weeks after injection of NGD-MNPs or PBS (the scale bar is 50 μm). (F) Blood samples were collected from PBS or NGD-MNPs treated groups at different time points, and serum concentrations of AST, (G) ALT and (H) CREAT were analyzed. (I) Splenocytes from the immunized mice were incubated with NGD-MNPs for 2 days and then measured by the MTT assay to calculate the SI. (J) Splenocytes were isolated from immunized mice 10 days after the last immunization and the relative percentages of CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Immunogenicity assay of nanoparticles

Splenic lymphocytes were sorted from mice immunized with NGD-MNPs or PBS and analyzed using a proliferation assay. The SI value of the NGD-MNPs immunized group (1.313 ± 0.09) was higher than that of the PBS control group, but the difference was not significant. These results indicate that NGD-NPs do not strongly stimulate T-cell proliferative response in mice (Fig. 4I). The percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets in spleen cells were slightly higher in mice immunized with NGD-MNPs than that immunized with PBS, but the difference was not significant (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4J). These flow cytometry assays demonstrated that the NGD-MNPs have little influence on the activation of T cells.

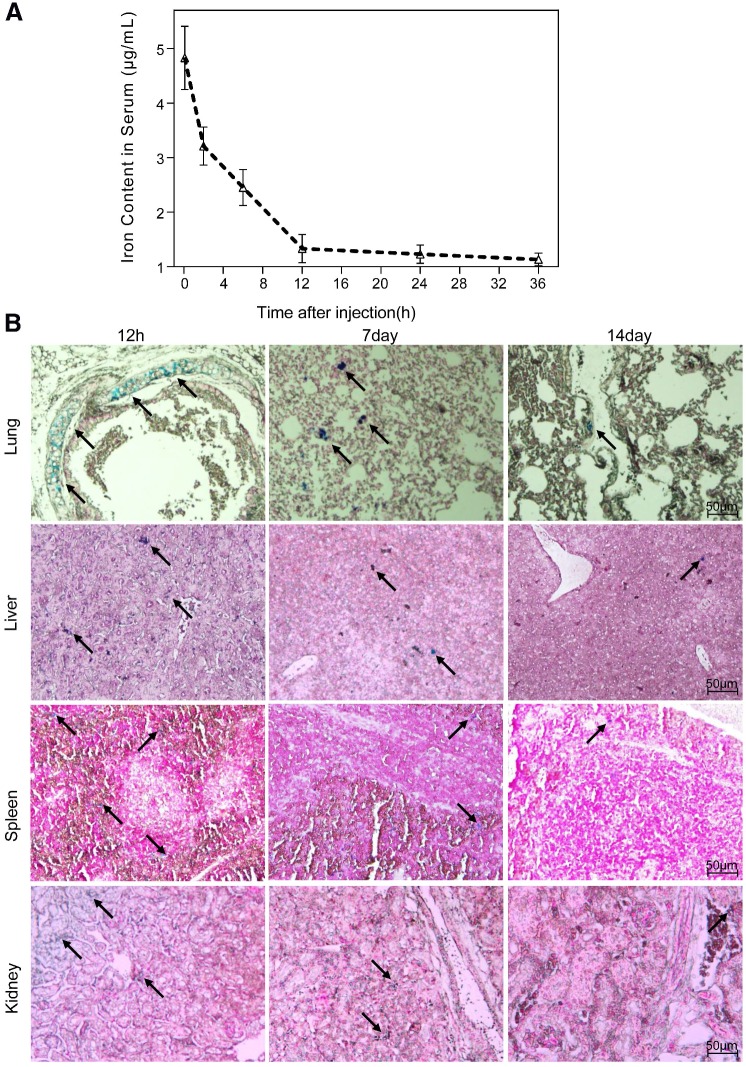

Blood retention time and biodistribution of nanoparticles

The half-life period of the nanoparticles, calculated from the iron content in the serum of mice, was 6.2 h (Fig. 5A). The biodistribution of the nanoparticles in vivo was evaluated by Prussian blue staining of major organs sectioned at different time points after a single intravenous administration. We observed a preferential accumulation of nanoparticles in liver, lungs, kidneys and spleen rather than in heart or brain. Overall, the clearance process of nanoparticles in tissue lasted for 15 days, which was much slower than that in serum. The temporal biodistribution varied according to the different organ. There was a greater reduction of nanoparticle in kidneys and lungs than in liver and spleen (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Biodistribution of NGD-MNPs in mice. (A) Blood retention time of NGD-MNPs in mice. (B) Representative Prussian blue staining of major visceral organs (lungs, liver, spleen and kidneys) harvested at 12 h, 1 week and 2 weeks after injection of NGD-MNPs (the scale bar is 50 μm).

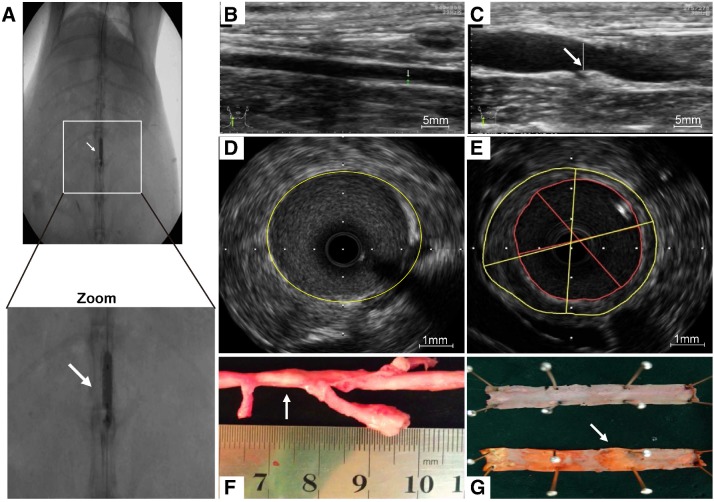

Intravascular and ultrasound imaging

As a consequence of abdominal aorta balloon de-endothelialization (Fig. 6A), vessel enlargement and plaque formation were observed compared to control group by ultrasound imaging (Fig. 6B, C). Meanwhile, an eccentric plaque with hypoechoic region was observed in the IVUS image, whereas no obvious atherosclerotic plaque was observed in control group (Fig. 6D, E). Extensive yellow-white plaques were observed at the injured site of rabbit abdominal aorta on a macroscopic image (Fig. 6F). The lipid-rich plaques were observed by oil red O staining compared to control group (Fig. 6G).

Figure 6.

Atherosclerotic lesions. (A) Abdominal aorta balloon denudation model. (C) Representative ultrasound images show the vessel enlargement and plaque formation 8 weeks after injury, (B) but not in control group. (E) Representative intravascular ultrasound images show a greater plaque burden and plaque eccentricity, (D) but not in control group. (F) An advanced plaque was observed at the injured site of rabbit abdominal aorta. (G) Representative macroscopic image shows the lipid-rich plaque by oil red O staining.

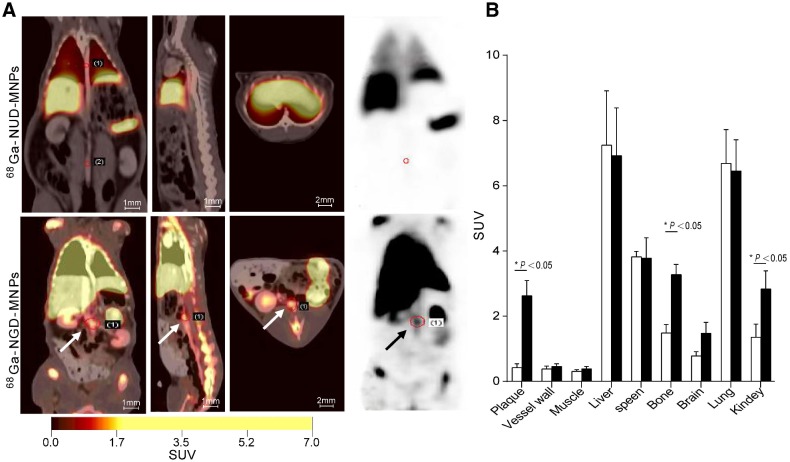

In vivo PET/CT and MR imaging

The targeting efficacy of 68Ga-NGD-MNPs in atherosclerotic plaque was evaluated with static scans. The uptake of probe in plaque tissue and major organs were quantified based on ROI analysis of the PET images (Fig. 7A). The plaque was clearly visible with high contrast relative to background at 60 min after 68Ga-NGD-MNPs injection. Predominant uptake of 68Ga-NGD-MNPs was also visualized in the lungs, liver and kidneys. Meanwhile, there was little plaque uptake in 68Ga-NUD-MNPs control group. Standard uptake value (SUVs) of 68Ga-NGD-MNPs was higher than 68Ga-NUD-MNPs in atherosclerotic abdominal aorta (SUVmax = 2.34 vs 0.47, P < 0.05) (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

In vivo PET imaging study. (A) The PET images of rabbits 2 h after 68Ga-NGD-MNPs or 68Ga-NUD-MNPs injection. (B) Quantification of PET images. Plaque in 68Ga-NGD-MNPs group exhibited significantly greater mean standardized uptake value (SUV) than control group.

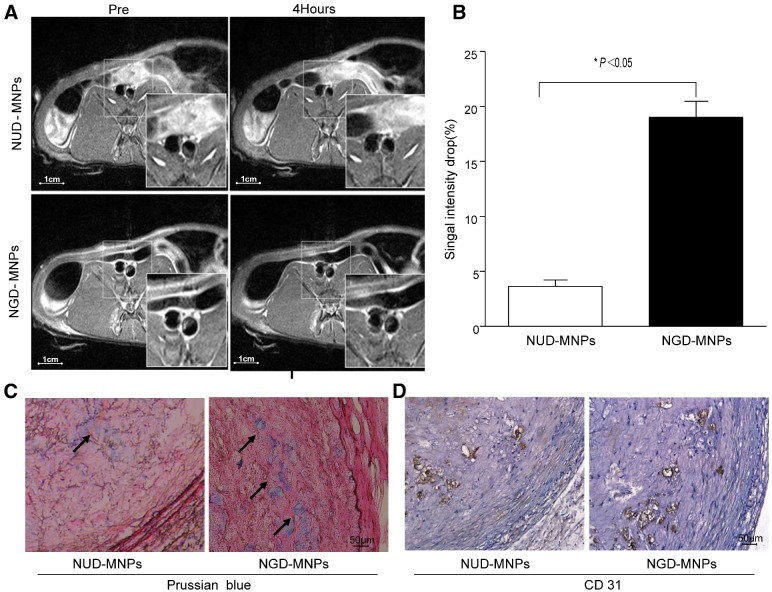

MRI was performed before and 4 h after nanoparticle administration. It was clearly observed that T2 signal intensity of plaque regions in NGD-MNPs group was affected compared to NUD-MNPs group. NGD-MNPs can effectively reduce the T2 relaxation time and consequently produce negative enhancement effects on T2-weighted images (Fig. 8A). Signal intensity in MR imaging of plaque declined by 17.5% 4 h post-injection in NGD-MNPs group compared to 3.68% in control group (P < 0.05, Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

In vivo MR imaging study. (A) The MR images of abdominal aorta before and 4 h after NGD-MNPs or NUD-MNPs injection (the scale bar is 1 cm). (B) Comparison of the relative signal intensity change (NENH%) in the T2-weighted images of abdominal arterial wall before and 4 h after NGD-MNPs or NUD-MNPs injection. (C) Prussian blue staining images show the accumulation of NGD-MNPs or NUD-MNPs in the plaque tissues extracted from rabbits. (D) CD31 immunohistochemistry images were recorded for showing the co-localization of CD31 and NGD-MNPs in the corresponding tissues (the scale bar is 50 μm).

Histology

Immunohistochemical analyses showed that a large number of nanoparticles deposited in plaque lesions in NGD-MNPs group compared to NUD-MNPs group (Fig. 8C). Moreover, Prussian blue and CD31 immunohistochemistry serial section staining further confirmed that NGD-MNPs were well co-localized with plaque microvasculature (Fig. 8D).

Discussion

Despite recent therapeutic developments, cardiovascular disorder remains a worldwide health challenge and causes a remarkable need for early diagnosis and sequential treatment. Because morphological imaging has some limitations in early diagnosis of vulnerable plaque, molecular imaging has emerged as a novel tool to identify molecular and cellular events critical for the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Accumulating evidence has linked plaque angiogenesis with progressive atherosclerotic disease and acute lesion instability 9, 28, 29. The plaque microvasculature can act as conduits for cellular and soluble lesion components (such as lipid, cytokines, and growth factors) 30. Moreover, the fragile structure of the neovasculature is prone to leakage and therefore promotes intra-plaque hemorrhage 31, 32. As mentioned above, molecular imaging approaches will be critical for monitoring angiogenesis processes in diseases, as well as evaluating physiological consequences of the therapeutic intervention. In this study, we have synthesized and evaluated a GEBP11 peptide-targeted imaging probe for angiogenesis molecular imaging with PET/MRI.

The essence of molecular imaging is the interaction between probes and targeted markers. The targeting ability of the imaging probe is the primary issue of molecular imaging. Successful molecular imaging relies on probes with high affinity, sensitivity and specificity. Peptides containing the integrin-binding motif Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) can image newly formed microvessels in both tumor tissue and atherosclerotic plaque 12, 33-36. In spite of the promising results, some researchers hypothesized that the RGD peptide might lack specificity for endothelial cells as macrophages can also express αvβ3 integrin in atherosclerotic plaque 37. Our previous results confirmed that GEBP11 peptide exhibits high affinity to tumor vasculature. In the present study, we clarified that GEBP11 peptide could selectively target endothelial cells rather than macrophages by immunofluorescence staining. The in vitro cell immunofluorescence results showed strong evidence of specific GEBP11 peptide ligand expression in HUVECs. The Prussian blue staining demonstrated a significant increase of 68Ga-NGD-MNPs uptake in the plaque with the maximum value at 60 min after the injection of the nanoprobe.

Another challenge for the in vivo imaging is that the size of imaging probe should be accurately controlled. The aorta endothelial tight gap junction associated with the plaque is approximately 20 nm in mice 38. On the other hand, circulating MNPs less than 10 nm of diameter will be quickly eliminated by renal clearance, while the particles greater than 200 nm are inclined to be captured by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) 39. Hence, we designed NGD-MNPs, of which inorganic core size is very close to 10 nm and the hydrodynamic diameter is only 130.8 nm ± 7.1 nm. This disparity is attributed to the interaction between coating materials and solvent molecule. Compared with DMSA-MNP, hydrodynamic size of the nanoparticles expressed an increase after their conjugation with GEBP11 peptide and NOTA, but hydrodynamic size of NGD-MNPs could be well controlled under 150 nm by altering the ratio of GEBP11 to DMSA-MNPs. In our previous study, we found that one DMSA-coated nanoparticle could be conjugated with approximately 4 GEBP11 peptides 40. The change of zeta potential indicated a successful conjugation between nanoparticles and the other segments. Our results revealed that NGD-MNPs had a long blood circulation time, resulting in more opportunities for the interaction between ligands and NGD-MNPs.

The toxicity of magnetic nanoparticles is one of the most important issues that needs further investigation. Emerging studies suggest that DMSA-MNPs have good biocompatibility for MR imaging both in vitro and in vivo 41-45. In spite of the greater uptake of nanoparticles mediated by GEBP11 peptide, rare detectable cytotoxic effect was observed in cells and tissues assays. Furthermore, biochemical analysis (AST, ALT and CREA) verified that NGD-MNPs had little effect on these important biological functions of normal rats and showed good biocompatibility for further biomedical application. Immunogenicity is another significant concern for biologic drugs as it can affect both safety and efficacy 46. In this study, we found that NGD-NPs did not strongly stimulate T-cell proliferative response in mice. The immune response might depend not only on the chemical structure of GEBP11 peptide on the nanoparticle surface, but also on extrinsic factors, such as MNP dose and the MNPs coating modification.

Molecular imaging relies on various imaging technologies, each approach presents advantages and weaknesses. PET provides high sensitivity and allows quantitative measurements, albeit with relatively limited spatial resolution. MRI is good at representing anatomical information, but has limitations for analysis of molecular events. Using hybrid imaging methods allows combination of the benefits of different imaging platforms 3. The combination of MRI contrast agent DMSA-MNPs and the positron emitter 68Ga complements each weakness and maximizes strengths of these two imaging modalities. The macrocyclic chelator NOTA was selected to interact with 68Ga because it allows for highly efficient radiolabeling under mild conditions to ensure the biological activity of targeting molecules 47. Iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) have been widely used not only as negative contrast agent for MR imaging, but also as an effective carrier for peptides to prolong their circulation half-life 48. The increased cellular uptake of NGD-MNPs confirmed that the chemical conjugation with DMSA-MNPs and NOTA exerted no detrimental effect on the bioactivity of GEBP11 peptide. GEBP11 peptide has ability to facilitate cellular uptake of nanoparticles.

The PET images showed that predominant uptake of 68Ga-NGD-MNPs was visualized in the plaque, lungs, liver and kidneys. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that the probe is metabolized through the liver and kidneys. The Prussian blue and CD31 immunohistochemistry were used to further evaluate the targeting specificity of NGD-MNPs. The co-localization of NGD-MNPs with CD31 is consistent with PET/MR images. The signal change of PET/MR images could serve as a surrogate marker of microvascular density in atherosclerotic plaques. NGD-MNPs may provide a useful tool to assess the atherosclerotic plaque burden and severity.

Despite these encouraging results, there are still some limitations in our research. GEBP11 peptide receptor on vascular endothelial cell is still unclear, but several candidate receptor molecules have been obtained. Further work is underway to provide a detailed structural understanding of the interaction between GEBP11 peptide and its ligand. Whether the probe of NGD-MNPs can serve as a therapeutic intervention vector still requires further investigation.

Conclusions

We developed a novel PET/MR dual-modality imaging probe (NGD-MNPs) for noninvasive assessment of angiogenesis in atherosclerotic plaque in this study. NGD-MNPs could selectively accumulate within the plaque vasculature and was suitable for in vivo molecular imaging of progressive plaque angiogenesis formation with high specificity and sensitivity.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1 shows the binding affinity of GEBP11 peptide to EAhy926 cells. Immunofluorescence images of FITC-labeled GEBP11 peptide or un-related peptide (URP) incubated EAhy926 cells (the scale bar is 50 μm).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research Program of China (2016YFA0100903), the National Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists of China (.81325009) and National Nature Science Foundation of China (81227901, 81530058, and 81570272) and Innovation Team Grant of Shaanxi Province (No.2014KCT-20).

Abbreviations

- AAS

atomic absorption spectrophotometer

- CAG

coronary X-ray angiography

- CCTA

coronary computed tomography angiograpy

- CoCl2

cobalt chloride

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DAPI

4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- DMSA-MNPs

2, 3-dimercaptosuccinnic acid-coated paramagnetic nanoparticles

- EDTA

trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention

- 68Ga-NUD-MNPs

68Ga-NOTA-unrelated peptide-DMSA-MNPs

- 68Ga-NGD-MNPs

68Ga-NOTA-GEBP11-DMSA-MNP

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- IVUS

intravascular ultrasonography

- MNPs

magnetic nanoparticles

- MR

magnetic resonance

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- SUVs

standard uptake values

- TLC

radio-thinlayer chromatography

- TEM

transmission electronic microscopy

- UPR

unrelated peptide

- TR

repetition time

- TE

echo times

References

- 1.Bucerius J, Hyafil F, Verberne HJ, Slart RH, Lindner O, Sciagra R. et al. Position paper of the Cardiovascular Committee of the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) on PET imaging of atherosclerosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;43:780–92. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libby P. Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2004–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1216063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goel S, Miller A, Agarwal C, Zakin E, Acholonu M, Gidwani U. et al. Imaging Modalities to Identity Inflammation in an Atherosclerotic Plaque. Radiol Res Pract. 2015;2015:410967. doi: 10.1155/2015/410967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah PK. Biomarkers of plaque instability. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16:547. doi: 10.1007/s11886-014-0547-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waxman S, Ishibashi F, Muller JE. Detection and treatment of vulnerable plaques and vulnerable patients: novel approaches to prevention of coronary events. Circulation. 2006;114:2390–411. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beller GA. Imaging of vulnerable plaques: will it affect patient management and influence outcomes? J Nucl Cardiol. 2011;18:531–3. doi: 10.1007/s12350-011-9412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falk E, Nakano M, Bentzon JF, Finn AV, Virmani R. Update on acute coronary syndromes: the pathologists' view. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:719–28. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quillard T, Libby P. Molecular imaging of atherosclerosis for improving diagnostic and therapeutic development. Circ Res. 2012;111:231–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyle B, Caplice N. Plaque neovascularization and antiangiogenic therapy for atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2073–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreno PR, Purushothaman KR, Fuster V, Echeverri D, Truszczynska H, Sharma SK. et al. Plaque neovascularization is increased in ruptured atherosclerotic lesions of human aorta: implications for plaque vulnerability. Circulation. 2004;110:2032–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143233.87854.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parma L, Baganha F, Quax PHA, de Vries MR. Plaque angiogenesis and intraplaque hemorrhage in atherosclerosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.04.028. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winter PM, Neubauer AM, Caruthers SD, Harris TD, Robertson JD, Williams TA. et al. Endothelial alpha(v)beta3 integrin-targeted fumagillin nanoparticles inhibit angiogenesis in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2103–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000235724.11299.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gossl M, Herrmann J, Tang H, Versari D, Galili O, Mannheim D. et al. Prevention of vasa vasorum neovascularization attenuates early neointima formation in experimental hypercholesterolemia. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;104:695–706. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0036-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vries MR, Quax PH. Plaque angiogenesis and its relation to inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque destabilization. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2016;27:499–506. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang S, Lin T, Ding J, Pan Y, Dang D, Guo C. et al. Screening and identification of vascular-endothelial-cell-specific binding peptide in gastric cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 2006;84:764–73. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Chen J, Yang B, Qiao H, Gao L, Su T. et al. In vivo MR and Fluorescence Dual-modality Imaging of Atherosclerosis Characteristics in Mice Using Profilin-1 Targeted Magnetic Nanoparticles. Theranostics. 2016;6:272–86. doi: 10.7150/thno.13350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu L, Yin J, Liu C, Guan G, Shi D, Wang X. et al. In vivo molecular imaging of gastric cancer in human-murine xenograft models with confocal laser endomicroscopy using a tumor vascular homing peptide. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:891–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Hu H, Liang S, Yin J, Hui X, Hu S. et al. Targeted radiotherapy with tumor vascular homing trimeric GEBP11 peptide evaluated by multimodality imaging for gastric cancer. J Control Release. 2013;172:322–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayase M, Woodbum KW, Perlroth J, Miller RA, Baumgardner W, Yock PG. et al. Photoangioplasty with local motexafin lutetium delivery reduces macrophages in a rabbit post-balloon injury model. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:449–55. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun S, Zeng H, Robinson DB, Raoux S, Rice PM, Wang SX. et al. Monodisperse MFe2O4 (M = Fe, Co, Mn) nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:273–9. doi: 10.1021/ja0380852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roca AG, Veintemillas-Verdaguer S, Port M, Robic C, Serna CJ, Morales MP. Effect of nanoparticle and aggregate size on the relaxometric properties of MR contrast agents based on high quality magnetite nanoparticles. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:7033–9. doi: 10.1021/jp807820s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gauthier MA, Klok HA. Peptide/protein-polymer conjugates: synthetic strategies and design concepts. Chem Commun (Camb); 2008. pp. 2591–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu B, Li X, Yin J, Liang C, Liu L, Qiu Z. et al. Evaluation of 68Ga-labeled MG7 antibody: a targeted probe for PET/CT imaging of gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8626. doi: 10.1038/srep08626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen B, Cao S, Zhang Y, Wang X, Liu J, Hui X. et al. A novel peptide (GX1) homing to gastric cancer vasculature inhibits angiogenesis and cooperates with TNF alpha in anti-tumor therapy. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hui X, Han Y, Liang S, Liu Z, Liu J, Hong L. et al. Specific targeting of the vasculature of gastric cancer by a new tumor-homing peptide CGNSNPKSC. J Control Release. 2008;131:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang XJ, Lu X, Lei YF, Yang J, Yao M, Lan HY. et al. Cellular immunogenicity of a multi-epitope peptide vaccine candidate based on hepatitis C virus NS5A, NS4B and core proteins in HHD-2 mice. J Virol Methods. 2013;189:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olugbile S, Villard V, Bertholet S, Jafarshad A, Kulangara C, Roussilhon C. et al. Malaria vaccine candidate: design of a multivalent subunit alpha-helical coiled coil poly-epitope. Vaccine. 2011;29:7090–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat Med. 2003;9:653–60. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleiner M, Kummer M, Mirlacher M, Sauter G, Cathomas G, Krapf R. et al. Arterial neovascularization and inflammation in vulnerable patients: early and late signs of symptomatic atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;110:2843–50. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146787.16297.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–9. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmadi A, Leipsic J, Blankstein R, Taylor C, Hecht H, Stone GW. et al. Do plaques rapidly progress prior to myocardial infarction? The interplay between plaque vulnerability and progression. Circ Res. 2015;117:99–104. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Finn AV, Gold HK, Tulenko TN. et al. Atherosclerotic plaque progression and vulnerability to rupture: angiogenesis as a source of intraplaque hemorrhage. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2054–61. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000178991.71605.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lal H, Verma SK, Foster DM, Golden HB, Reneau JC, Watson LE. et al. Integrins and proximal signaling mechanisms in cardiovascular disease. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009;14:2307–34. doi: 10.2741/3381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winter PM, Morawski AM, Caruthers SD, Fuhrhop RW, Zhang H, Williams TA. et al. Molecular imaging of angiogenesis in early-stage atherosclerosis with alpha(v)beta3-integrin-targeted nanoparticles. Circulation. 2003;108:2270–4. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093185.16083.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burtea C, Laurent S, Murariu O, Rattat D, Toubeau G, Verbruggen A. et al. Molecular imaging of alpha v beta3 integrin expression in atherosclerotic plaques with a mimetic of RGD peptide grafted to Gd-DTPA. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78:148–57. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winter PM, Caruthers SD, Zhang H, Williams TA, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Antiangiogenic synergism of integrin-targeted fumagillin nanoparticles and atorvastatin in atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1:624–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laitinen I, Saraste A, Weidl E, Poethko T, Weber AW, Nekolla SG. et al. Evaluation of alphavbeta3 integrin-targeted positron emission tomography tracer 18F-galacto-RGD for imaging of vascular inflammation in atherosclerotic mice. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:331–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.846865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Briley-Saebo KC, Cho YS, Shaw PX, Ryu SK, Mani V, Dickson S. et al. Targeted iron oxide particles for in vivo magnetic resonance detection of atherosclerotic lesions with antibodies directed to oxidation-specific epitopes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:337–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, Wang Y, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Advances of cancer therapy by nanotechnology. Cancer Res Treat. 2009;41:1–11. doi: 10.4143/crt.2009.41.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su T, Wang Y, Wang J, Han D, Ma S, Cao J. et al. In Vivo Magnetic Resonance and Fluorescence Dual-Modality Imaging of Tumor Angiogenesis in Rats Using GEBP11 Peptide Targeted Magnetic Nanoparticles. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2016;12:1011–22. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2016.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mejias R, Gutierrez L, Salas G, Perez-Yague S, Zotes TM, Lazaro FJ. et al. Long term biotransformation and toxicity of dimercaptosuccinic acid-coated magnetic nanoparticles support their use in biomedical applications. J Control Release. 2013;171:225–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monge-Fuentes V, Garcia MP, Tavares MC, Valois CR, Lima EC, Teixeira DS. et al. Biodistribution and biocompatibility of DMSA-stabilized maghemite magnetic nanoparticles in nonhuman primates (Cebus spp.) Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011;6:1529–44. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qin J, Li K, Peng C, Li X, Lin J, Ye K. et al. MRI of iron oxide nanoparticle-labeled ADSCs in a model of hindlimb ischemia. Biomaterials. 2013;34:4914–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hou Y, Liu Y, Chen Z, Gu N, Wang J. Manufacture of IRDye800CW-coupled Fe3O4 nanoparticles and their applications in cell labeling and in vivo imaging. J Nanobiotechnology. 2010;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen W, Cao Y, Liu M, Zhao Q, Huang J, Zhang H. et al. Rotavirus capsid surface protein VP4-coated Fe(3)O(4) nanoparticles as a theranostic platform for cellular imaging and drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shankar G, Arkin S, Cocea L, Devanarayan V, Kirshner S, Kromminga A. et al. Assessment and reporting of the clinical immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins and peptides-harmonized terminology and tactical recommendations. AAPS J. 2014;16:658–73. doi: 10.1208/s12248-014-9599-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Velikyan I, Maecke H, Langstrom B. Convenient preparation of 68Ga-based PET-radiopharmaceuticals at room temperature. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:569–73. doi: 10.1021/bc700341x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cormode DP, Skajaa T, Fayad ZA, Mulder WJ. Nanotechnology in medical imaging: probe design and applications. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:992–1000. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1 shows the binding affinity of GEBP11 peptide to EAhy926 cells. Immunofluorescence images of FITC-labeled GEBP11 peptide or un-related peptide (URP) incubated EAhy926 cells (the scale bar is 50 μm).