Abstract

Introduction

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a highly prevalent vaginal polymicrobial disorder commonly encountered in women of childbearing age. Therapy with only recommended antibiotics results in low cure rates and unacceptably high recurrence rates. The use of probiotics as a complementary approach for use with antibiotics for the treatment of BV remains unclear. This review aims to assess the efficacy of lactobacilli administered intravaginally in conjunction with antibiotics for the treatment of BV.

Methods and analysis

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in The Cochrane Library, Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews, Medline/PubMed and Embase will be used to search for articles from database inception to November 2016. Randomised controlled clinical trials using lactobacilli administered intravaginally in conjunction with antibiotics to treat BV will be included. Primary outcome will be the BV cure rate. The recurrence rate will be examined as secondary outcome. Two reviewers will independently select trials and extract data from the original publications. The risk of bias will be assessed according to the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. We will perform data synthesis using the Review Manager (RevMan) software V.5.2.3. To assess heterogeneity, we will compute the I2 statistic.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will be a review of published data and it is not necessary to obtain ethical approval. Findings of this systematic review will be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews 2014: CRD42014015079.

Keywords: genitourinary medicine, microbiology, bacteriology, urogynaecology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There are no existing reviews about the use of probiotics administered intravaginally as a complementary approach to antibiotic treatment of BV.

This systematic review includes studies on participants of all ages diagnosed with BV based on Amsel’s criteria or the Nugent score, regardless of whether they are symptomatic or asymptomatic.

Two reviewers will independently select trials eligibility to be included in this review, extract data on different variables and assess risk of bias.

Our review would be limited by variation in treatment frequency, courses of treatment and the quality of each randomised randomised controlled trial in this area.

Our review and meta-analysis intends to combine the results of different studies that have comparable effect sizes to be computed. However, it may be that we will only obtain a small sample size and limited number of studies, which might influence the validity and reliability of the conclusions.

Introduction

Description of the condition

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a highly prevalent vaginal polymicrobial disorder, affecting 5%–58% women of childbearing age in different parts of the world.1 2 Whether symptomatic or asymptomatic, BV increases the risks for pelvic inflammatory disease, subsequent infertility and preterm delivery, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV transmission.3–7 Previous studies have shown that a complex and high population of the lactobacilli in vaginal microbiota are regarded as protective against BV, which is typified by a profound overgrowth of vaginal anaerobic bacteria.8 9

Description of the intervention

Both the killing and growth inhibiting activities of antibiotics are important towards suppressing anaerobes in the vagina.10 However, therapy only with recommended antibiotics, including metronidazole or clindamycin, results in low cure rates (10%–15%) and unacceptably high recurrence rates (up to 80%).11 These low rates are possibly due to an inability of the host to restore the lactobacilli-dominated vaginal flora, making the use of Lactobacillus probiotics a promising treatment and prevention strategy. Moreover, repeated antibiotic exposure increases the risk of the emergence of resistant strains.12 13

How the intervention might work

Probiotics, defined as live microorganisms, intend to have a health benefit when administered in adequate amounts. As previously reported, probiotics can potentially replace antibiotics as a safer prophylactic for recurrent urinary tract infections and do help to restore the normal intestinal flora for antibiotic-associated diarrhoea.14–16 The presence of Lactobacillus spp is a major determinant of normal vaginal microbial flora. Hence, lactobacilli are usually used as probiotics to treat BV, which would presumably maintain or restore the vaginal microecology through competition for nutrients, inhibition of epithelial and mucosal adherence of pathogens or stimulation of host immunity. The ability of lactobacilli to colonise vaginal epithelial cells depends on the route of delivery. Vaginally inserting capsules may be an effective way to regenerate the local lactobacilli of women.17 18

Why it is important to perform this review

Previous reviews have focused on specific patient populations or probiotics themselves and have not included the latest randomised controlled trials (RCTs).19–21 A 2009 Cochrane review on the treatment of BV with probiotics has not separated the conventional antibiotics used in conjunction with probiotics administered intravaginally from other probiotic preparations and trial methodologies.22 Additionally, this review included participants that were coinfected with other STIs and diagnosed with BV, regardless of the diagnostic method used.22 Most studies suggested that there was insufficient evidence to recommend probiotics for the treatment of BV.19 21 However, the result may be due to the heterogeneity among the routes of delivery and methodologies of treatment. Until now, the effectiveness of probiotics as a complementary approach for use with antibiotics for treatment of BV remains unclear.

Objectives

The objective of the study is to systematically review and, if possible, perform a quantitative meta-analysis to determine the efficacy of a single strain or cocktail of lactobacilli administered intravaginally in conjunction with antibiotics for the treatment of BV.

Methods

This protocol has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, registration number CRD42014015079. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines will be used to construct this systematic review protocol.23

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

The inclusion criteria will be as follows: (1) the article is reported in English; (2) if the data subsets are published in more than one article, only the latest subset is included and (3) parallel RCTs.

The following studies will be excluded: (1) case reports; (2) publications that are not in English and (3) insufficient data to be extracted or calculated from the original article.

Types of participants

Participants of all ages diagnosed with BV based on Amsel’s criteria or the Nugent score,24 regardless of whether she is symptomatic or asymptomatic, will be included. Analyses of the trials based on Amsel’s criteria will be performed separately from those based on the Nugent score. Patients coinfected with other STIs will be excluded.

Types of interventions

Parallel RCTs that compare probiotics administered intravaginally in conjunction with antibiotics therapy with a concurrent control group receiving no treatment, a placebo or a different probiotic/antibiotic or probiotic/antibiotic dose will be eligible.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome will be the BV cure rates in each treatment group. According to the guidelines from the US Food and Drug Administration, verification of the BV cure should be conducted between 21 and 30 days after the initiation of therapy, with cure defined as an absence of Amsel’s criteria and a Nugent score <3. Secondary outcome will be the recurrence rate of BV, defined as the presence of ≥3 per Amsel’s criteria or a Nugent score of ≥7.24 Discrepancies will be resolved through discussion by the review team.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in The Cochrane Library, Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews, Medline/PubMed and EmbasE will be used to search for articles from database inception to November 2016.

Other sources

The scope of the computerised literature search will be enlarged on the basis of the reference lists of retrieved articles.

Search strategy

Table 1 presents the search strategy for Medline.

Table 1.

Medline search strategy

| Search items | |

| 1 | randomized controlled trial |

| 2 | controlled clinical trial |

| 3 | randomized |

| 4 | trial |

| 5 | or/1–4 |

| 6 | bacterial vaginosis or BV/ |

| 7 | bacterial vaginitis or BV/ |

| 8 | or/6–7 |

| 9 | drug therapy/ |

| 10 | treatment/ |

| 11 | antibiotics/ |

| 12 | or/9–11 |

| 13 | probiotics/ |

| 14 | Lactobacillus/ |

| 15 | or/13–14 |

| 16 | 5 and 8 and 12 and 15 |

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

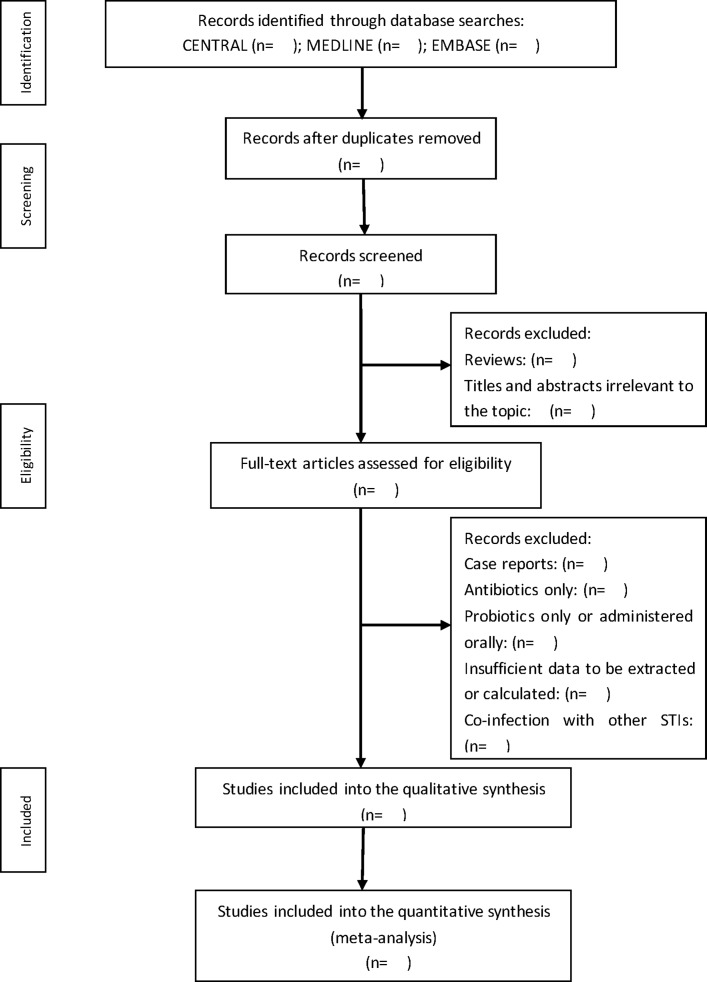

Two authors, LM and YS, will independently screen the search results using titles and abstracts. Duplicates and reviews will be removed from the database. Reviewers will then go through the full text to determine whether they meet the inclusion criteria. Studies will be excluded if they used antibiotics or probiotics only and if their patients were coinfected with other STIs. Discrepancies will be resolved by a third reviewer, JS. The selection of the study is summarised in a PRISMA flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the search for eligible studies on the probiotics administered intravaginally as a complementary therapy in combination with antibiotics for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors, LM and ZZ, will independently assess and extract the study data according to a data extraction form that includes basic details (name of the authors, publication date, country, sample size), participant details (age, underlying symptomatology), diagnostic standards (Amsel’s criteria or Nugent score) and intervention details (genus of the probiotics, dose and duration of the probiotics and antibiotics) and outcomes (cure rates of BV, recurrences rates of BV, vaginal lactobacilli colonisation, restoration of a normal vaginal microbiota, occurrence of side effects). Extracted data will be checked by WS and disagreements will be resolved through discussion. If necessary, a further reviewer, JS, will provide the final judgement.

Risk of bias assessment

Two independent reviewers, WS and LM, will apply the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool to assess random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, clinicians and outcome assessment. In addition, we have assessed the incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, funding and potential for conflict of interest associated with the individual trials. The risk of bias will be rated using predetermined criteria as follows: low, high or unclear.

Measures of treatment effect

This will be carried out using the RevMan Analyses statistical package in Review Manager V.5.1 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011). We will calculate the OR for dichotomous data and weight mean difference (MD) for continuous data with associated 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

For the cure rate of BV, the unit of analysis will be defined as 21 and 30 days after the initiation of therapy. For the recurrence rate of BV, 3 months and 6 months following the intervention will be considered as short-term and long-term follow-up, respectively.

Addressing missing data

We will attempt to obtain any missing data by contacting the first or corresponding authors or coauthors of an article via phone, email or post. If we fail to receive any necessary information, the data will be excluded from our analysis and will be addressed in the Discussion section.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The heterogeneity between trial results will be evaluated using a standard X2 test with a significance level of p<0.1. To assess heterogeneity, we plan to compute the I2 statistic, which is a quantitative measure of inconsistency across studies. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, whereas I2 values of ≥50% indicate a substantial level of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If possible, funnel plots will be used to assess the presence of potential reporting biases. A linear regression approach will be used to evaluate funnel plot asymmetry.25

Data synthesis

This will be carried out using the RevMan Analyses statistical package in Review Manager V.5.1. For dichotomous outcomes, we will derive the OR and 95% CI for each study. Where there is heterogeneity (I2 >75%), a random-effect model will be used to combine the trials to calculate the relative risk (RR) and 95% CI, using the DerSimonian-Laird algorithm in The Meta for Package, a meta-analysis package for R.

Other study characteristics and results will be summarised narratively, if the meta-analysis cannot be performed for all or some of the included studies.

Sensitivity analyses

We will conduct sensitivity analyses to explore the robustness of the findings regarding the study quality and sample size. Sensitivity analyses will be showed in a summary table.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses will be based on the probiotic genus, participant ages, different control interventions and study settings. To investigate whether any observed differences between subgroups is statistically significant, meta-regressions will be conducted to compare the ratio of relative risks.

Confidence in cumulative evidence

To describe the strength of evidence for included data, we will use the Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook to incorporate summary assessments into broader measures to ensure the judgements about bias risk, consistency, directness, precision and publication bias.26 Quality of evidence will be identified as high (the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect), moderate (the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different), low (the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect) or very low (the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect).

Discussion

BV is a very common and relevant clinical problem, with a significant adverse impact on women’s health. We aim to analyse the efficacy and safety of probiotics administered intravaginally combined with antibiotic therapy for the treatment of BV. In theory, antibiotics can break down the overgrowth of vaginal anaerobes and formation of biofilm. Consequently, probiotics administered intravaginally will adhere to and colonise vaginal epithelial cell surfaces. We expect that our review will provide accurate data for effective policy-making. Furthermore, this review will improve our understanding of treatment of BV with antibiotics and probiotics.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval is not required because this systematic review will use published patient data. Findings of this systematic review will be published in a peer-reviewed journal and updates will be conducted if there is enough new evidence that may cause any change in review conclusions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance provided byXiaohai Wu (librarian) in conducting the literaturesearch.

Footnotes

Contributors: JS is the guarantor. LM and JS contributed to the conception of this review. LM drafted the manuscript of the protocol and JS revised it. LM and JS developed the search strategies and WS and ZZ will implement them. LM, YS, WS and ZZ will screen the potential studies, extract the data and assess quality. In case of disagreement between the data extractors, JS will advise on the methodology and will work as the arbitrator. LM will complete the data synthesis. All authors have approved the final version for publication.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 30972819). The funders had no role in the protocol design, data collection and analysis plan, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. This fund covers the expenses including the use of the databases, printing of the papers and communication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.Walker J, Hocking JS, Fairley CK, et al. . The prevalence and incidence of bacterial vaginosis in a cohort of young Australian women In:Conference proceedings of the International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research Quebec, Canada, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenyon C, Colebunders R, Crucitti T. The global epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209:505–23. 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dingens AS, Fairfortune TS, Reed S, et al. . Bacterial vaginosis and adverse outcomes among full-term infants: a cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:278–86. 10.1186/s12884-016-1073-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leitich H, Kiss H. Asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis and intermediate flora as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007;21:375–90. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen CR, Lingappa JR, Baeten JM, et al. . Bacterial vaginosis associated with increased risk of female-to-male HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort analysis among African couples. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001251 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haggerty CL, Totten PA, Tang G, et al. . Identification of novel microbes associated with pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility. Sex Transm Infect 2016;92:441–6. 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atashili J, Poole C, Ndumbe PM, et al. . Bacterial vaginosis and HIV acquisition: a meta-analysis of published studies. AIDS 2008;22:1493–501. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283021a37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamont RF, Sobel JD, Akins RA, et al. . The vaginal microbiome: new information about genital tract flora using molecular based techniques. BJOG 2011;118:533–49. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02840.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, McCormick J, Bocking A, et al. . Importance of vaginal microbes in reproductive health. Reprod Sci 2012;19:235–42. 10.1177/1933719111418379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oduyebo OO, Anorlu RI, Ogunsola FT. The effects of antimicrobial therapy on bacterial vaginosis in non-pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;3:CD006055 10.1002/14651858.CD006055.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hay P. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009;22:82–6. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32832180c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. . High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect Dis 2006;193:1478–86. 10.1086/503780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomusiak A, Strus M, Heczko PB. Antibiotic resistance of Gardnerella vaginalis isolated from cases of bacterial vaginosis. Ginekol Pol 2011;82:900–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stapleton AE, Au-Yeung M, Hooton TM, et al. . Randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of a Lactobacillus crispatus probiotic given intravaginally for prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:1212–7. 10.1093/cid/cir183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hempel S, Newberry SJ, Maher AR, et al. . Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2012;307:1959–69. 10.1001/jama.2012.3507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su J, Ma L, Yan D, et al. . An E. coli strain and its preparation method used to treat intestinal microflora disorders. National invention patent; (2012), patent number: 2012ZL201110117270.7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomusiak A, Strus M, Heczko PB, et al. . Efficacy and safety of a vaginal medicinal product containing three strains of probiotic bacteria: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial. Drug Des Devel Ther 2015;9:5345–54. 10.2147/DDDT.S89214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ya W, Reifer C, Miller LE. Efficacy of vaginal probiotic capsules for recurrent bacterial vaginosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:e1–e6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mastromarino P, Vitali B, Mosca L. Bacterial vaginosis: a review on clinical trials with probiotics. New Microbiol 2013;36:229–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang H, Song L, Zhao W. Effects of probiotics for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis in adult women: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2013;289:1225–34. 10.1007/s00404-013-3117-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falagas M, Betsi GI, Athanasiou S. Probiotics for the treatment of women with bacterial vaginosis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2007;13:657–64. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01688.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senok AC, Verstraelen H, Temmerman M, et al. . Probiotics for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Cochrane DB Syst Rev; (2009):CD006289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forsum U, Hallén A, Larsson PG. Bacterial vaginosis-a laboratory and clinical diagnostics enigma. APMIS 2005;113:153–61. 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm1130301.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. . GRADE guidelines: rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:401–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.