Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) remains a leading cause of cancer-related death in children and young adults. Since the 1960s, improvements in the treatment of children with ALL have led to 10-year survival rates now exceeding 85%.1 Philadelphia-like (Ph-like) ALL is characterized by a gene expression profile similar to that of BCR-ABL1 positive (Ph+) ALL but lacking the BCR-ABL1 oncogene and similarly, patients experience poor outcome.2–4 Ph-like ALL is associated with a range of genetic alterations, particularly rearrangements, which activate cytokine receptor and kinase signalling.2–4 In 2011, the Australian and New Zealand Children’s Haematology/Oncology Group (ANZCHOG) completed enrolment of patients to a minimal residual disease (MRD) intervention clinical trial, known as ALL8 (clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: ACTRN12607000302459). Children were stratified to high-risk regimens based on several criteria, including treatment failure or high MRD at day 79.5 Overall, 46 children with precursor B-ALL relapsed, and surprisingly 72% (33/46) of these patients were classified as medium-risk.6 In this retrospective study of ALL8, the frequency of patients with Ph-like ALL and their attendant genomic lesions were studied, and clinical outcomes were compared to those of non Ph-like B-ALL patients. The incidence of Ph-like ALL was 11.7%, where the majority of these children were reported to be of Caucasian ethnicity and stratified as being either standard- or medium-risk. Significantly, 57.8% (11/19) of Ph-like ALL patients subsequently relapsed compared to 16% (26/143) who were not Ph-like, with significantly inferior event-free and overall survival (P< 0.0001 and P=0.003, respectively).

Six hundred and fifty-six patients aged between one and eighteen years were evaluated for eligibility on the ANZCHOG ALL8 trial from 2002–2011. Ethical approval was obtained from each institutional Human Research Ethics Committee and parents or legal guardians gave written, informed consent. Two hundred and forty-five patients, selected on the basis of sample accessibility, were available for Ph-like ALL screening (Online Supplementary Figure S1). The mean age at diagnosis (6.4 yrs vs. 5.6 yrs, P=0.02) and higher white cell counts (WCC) (P<0.001), were significantly different between those available for analysis and those patients excluded, with the studied group also having a higher number of patients over ten years of age (23% vs. 16%) (Online Supplementary Table S1). Risk groups were similar in each cohort and, overall, event-free and relapse-free survival were not significantly different between both groups (Online Supplementary Figure S2).

The criteria for stratification to the high-risk group, based upon Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (BFM) protocols, were the presence of BCR-ABL1 or MLL t(4;11) translocation; poor prednisolone response at day eight; failure to achieve remission by day 33 or high MRD (>5 ×10−4) at day 79 (Table 1A). Standard- and medium-risk patients received the same standard BFM four-drug induction chemotherapy regimen including a prednisolone pre-phase and intrathecal methotrexate. In addition to the four-drug protocol, high-risk patients received a further three novel intensive blocks of chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplant (SCT) in most cases.5 All BCR-ABL1 positive patients also received imatinib.

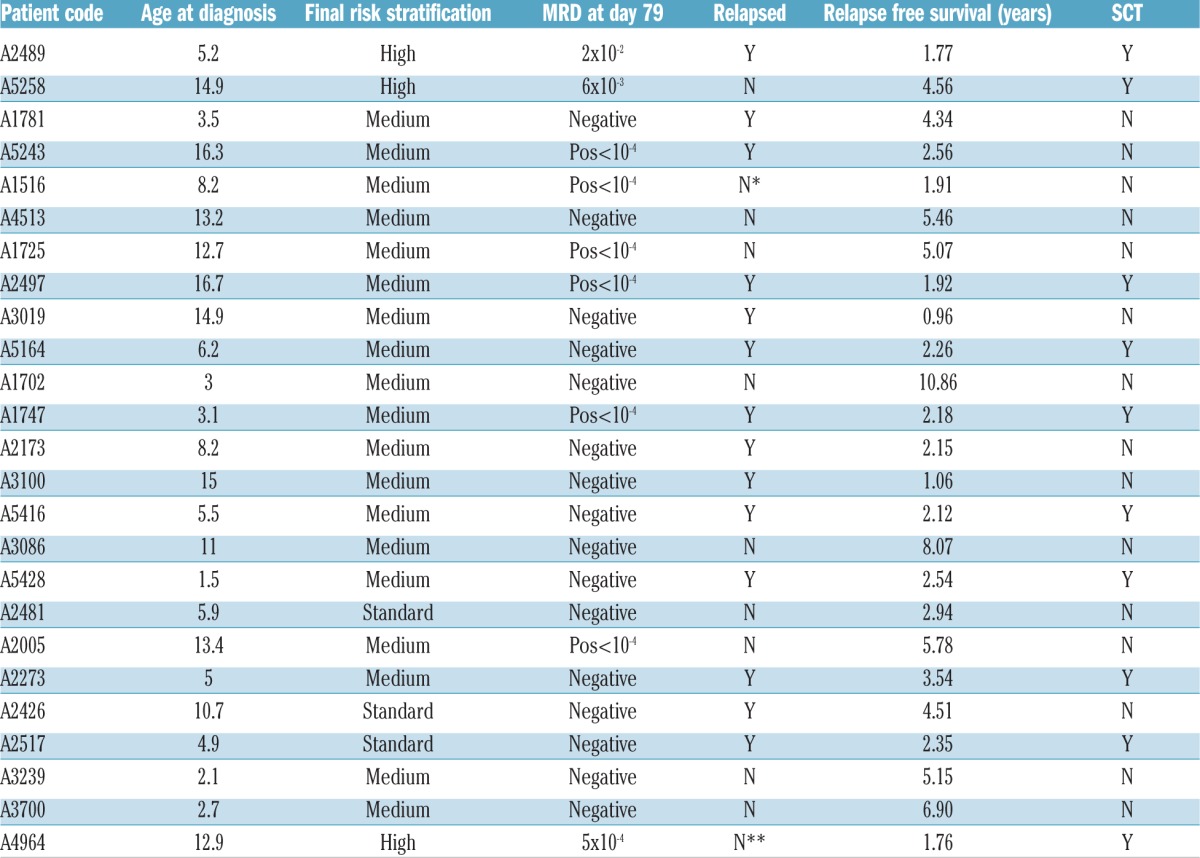

Table 1A.

Age, MRD, risk stratification, relapse status (A), rearrangements and variants of patients (B) identified with Ph-like ALL and P2RY8-CRLF2.

Determination of Ph-like ALL has differed between cohorts. European studies have favored the term BCR-ABL1-like ALL and have used hierarchical clustering (HC) of an Affymetrix gene expression array based on a probe set of 110 genes designed to detect major pediatric ALL subtypes.3 In contrast, US studies have used a TaqMan Low Density Arrays (TLDA) based approach consisting of either eight or fifteen genes selected by Prediction Analysis for Microarrays (PAM) analysis.7,8 While there is overlap, the HC model identifies a greater proportion of patients as having a BCR-ABL1-like signature, but this approach does not directly identify causative fusions.9,10 Based on the US approach, we have designed a custom TLDA using nine genes to identify patients with Ph-like ALL.7,11

The TLDA was used according to manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) to determine Ph-like status. Genes were selected based upon prior reports8 with CRLF2, PDGFRB, ABL1, ABL2 and EPOR also included to aid identification of potential fusions (Online Supplementary Methods). Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) followed by Sanger sequencing was performed using a panel of 30 known fusions on all TLDA positive cases and those with high CRLF2 gene expression.4 Cases with high CRLF2 expression were also subjected to fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) to confirm IGH-CRLF2 fusions. Illumina TruSeq stranded library preparation for messenger ribonucleic acid sequencing (mRNA seq) on the Illumina NextSeq or HiSeq platforms was performed on all TLDA positive and high CRLF2 cases, with the sole exception being that of a case with low RNA quality (Online Supplementary Methods). Patients were classified as having Ph-like ALL if a sample was TLDA positive.

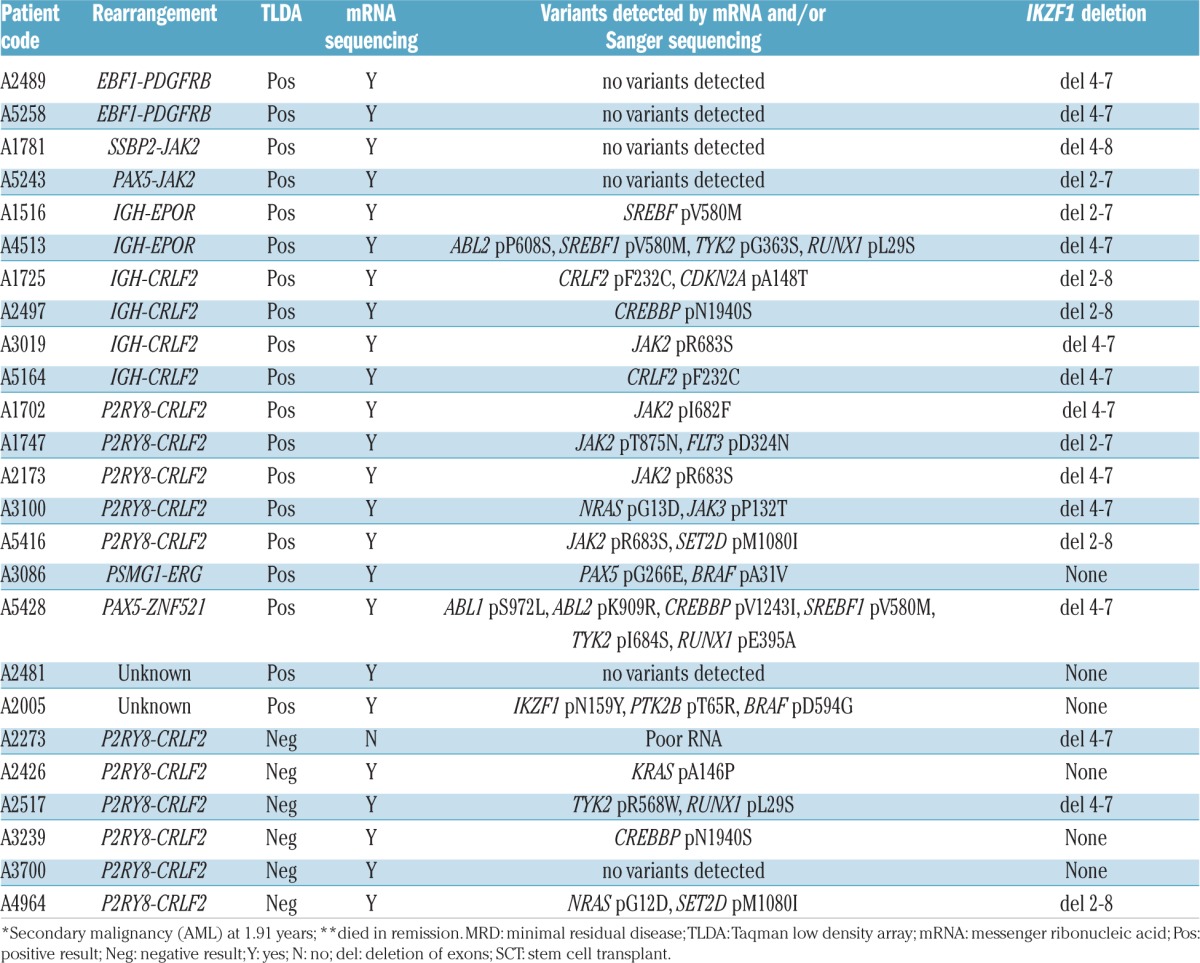

Cytokine or kinase activating lesions have been identified in the majority of childhood and adolescent/young adults (AYA) with Ph-like ALL.12 Of the 245 childhood BALL patients evaluated, eight patients were identified as being BCR-ABL1 positive and 75 had an ETV6-RUNX1 fusion, leaving 162 available for Ph-like screening. Nineteen patients (11.7%) were identified as having Ph-like ALL, as determined by TLDA. Rearrangements were identified in 17/19 patients (Table 1B).

Table 1B.

Age, MRD, risk stratification, relapse status (A), rearrangements and variants of patients (B) identified with Ph-like ALL and P2RY8-CRLF2.

Previous reports have suggested 27–60% of Ph-like ALL patients harbor rearrangements of CRLF2, with 50% of these demonstrating concomitant mutations in JAK1 or JAK2.4,13 Similarly, the majority of ALL8 Ph-like ALL cases (9/19, 47%) harbored CRLF2 rearrangements (CRLF2r), with 77.7% (7/9) demonstrating concomitant JAK2 or CRLF2 mutations. While there is some conjecture, the majority of studies have demonstrated CRLF2 overexpression is significantly associated with poor outcome.14,15 Importantly, 77.7% (7/9) of ALL8 Ph-like ALL patients with a CRLF2r, subsequently relapsed. Interestingly, a further six TLDA negative patients harbored CRLF2r. Of these patients three relapsed, and two subsequently underwent SCT. A fourth patient received a SCT but died in remission. The remaining identified fusions included EBF1-PDGFRB and IGH-EPOR (n=2), PAX5-JAK2, SSBP2-JAK2, PAX5-ZNF521 and PSMG1-ERG in one patient each (Table 1B).

IKZF1 deletions are shown to be significantly associated with relapse risk in both Ph+ and Ph-like ALL, with the frequency reported to be between 27% and 69% in Ph-like ALL cases.3,12,13 Of note, the ALL8 cohort included B-ALL patients in all risk stratifications, whereas other studies only included high-risk patients, potentially limiting comparisons between groups.3,12,13 Herein, IKZF1 deletions were significantly associated with Ph-like ALL (84% vs. 14%, P<0.0001). One Ph-like ALL patient, for whom a fusion was not identified, harbored an IKZF1 p.N159Y mutation detected by mRNA seq and validated in genomic DNA by PCR and Sanger sequencing.

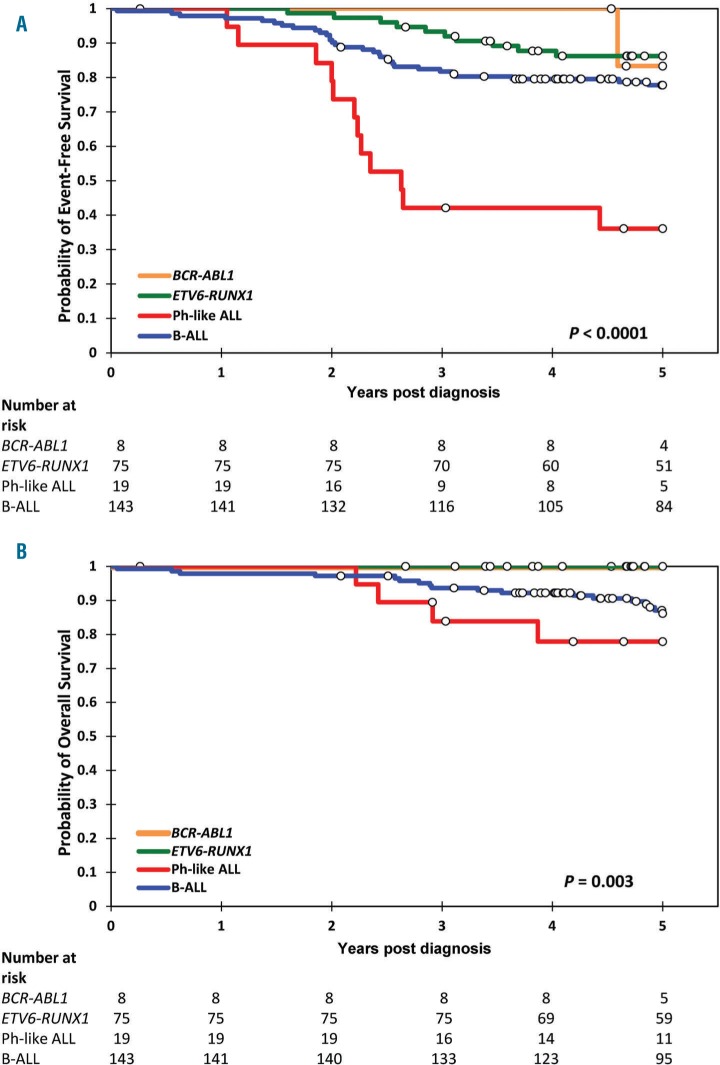

Most studies of patients with Ph-like ALL have demonstrated significantly inferior outcomes, which may be improved with treatment intensification.3,4,12 In contrast to patients enrolled on Total Therapy XV, a study of risk-directed therapy based on MRD wherein no significant differences in outcome were reported,13 the ALL8 Ph-like ALL cohort demonstrated significantly inferior event-free (P<0.0001) and overall survival (P=0.003; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Children with Ph-like ALL have inferior survival outcomes compared to other B-ALL patients. Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank statistic of A) event free survival and B) overall survival at five years post diagnosis. Children with Ph-like ALL are shown in red, BCR-ABL1+ patients in orange, ETV6-RUNX1 in green and the remaining BALL children in blue. The number of patients at risk for the different B-ALL subtypes is shown below the graph at each year.

On the ALL8 protocol, only two patients with Ph-like ALL had a final high-risk classification (both EBF1-PDGFRB) as a result of high MRD at day 79. One non Ph-like P2RY8-CRLF2 patient was also restratified to high-risk as a result of day 79 MRD. All three cases had IKZF1 deletions; one relapsed and a second died in remission. On ALL8, 72% (8/11) of patients classified as Ph-like ALL relapsed within six months of completing their two years of maintenance therapy (average time to relapse 2.1 years). At five years, the overall survival of Ph-like cases was 78% (15/19), indicating that many patients were salvaged by further therapy or SCT,5 but their survival rate was still significantly inferior to other B-ALL sub-groups. Similar to that observed in Total Therapy XV, ALL8 patients with Ph-like disease were twice as likely to undergo SCT.13

Herein, we demonstrate that despite a risk adjusted treatment approach, there remained a high rate of relapse among children in the ANZCHOG ALL8 study who were retrospectively identified as Ph-like. Of note, the MRD risk stratification used in this protocol did not identify all Ph-like ALL cases as high-risk. Finally, rapid identification of Ph-like disease may guide therapeutic intervention with rationally targeted therapies based on patient specific driving genomic lesions. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are increasingly utilized in patients with ABL-class fusions, with current and future trials likely to inform drug efficacy in the case of other targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Tissue Bank of the Children’s Research Institute for their assistance.

Footnotes

Funding: National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia (APP1057746, APP1044884); Channel 7 Children’s Research Fund, Adelaide, SA, Australia; Leukaemia Foundation, Australia; Cancer Council of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia; Beat Cancer, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

Information on authorship, contributions, and financial & other disclosures was provided by the authors and is available with the online version of this article at www.haematologica.org.

References

- 1.Pui CH, Pei D, Campana D, et al. A revised definition for cure of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2014; 28(12):2336–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mullighan CG, Su X, Zhang J, et al. Deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(5):470–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Den Boer ML, van Slegtenhorst M, De Menezes RX, et al. A subtype of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with poor treatment outcome: a genome-wide classification study. Lancet Oncol. 2009; 10(2):125–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts KG, Morin RD, Zhang J, et al. Genetic alterations activating kinase and cytokine receptor signaling in high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(2):153–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall GM, Dalla Pozza L, Sutton R, et al. High-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first remission treated with novel intensive chemotherapy and allogeneic transplantation. Leukemia. 2013;27(7):1497–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karsa M, Dalla Pozza L, Venn NC, et al. Improving the identification of high risk precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients with earlier quantification of minimal residual disease. PLoS One. 2013; 8(10):e76455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reshmi SC, Harvey RC, Roberts KG, et al. Targetable kinase gene fusions in high-risk B-ALL: a study from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood. 2017;129(25):3352–3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey RC, Kang H, Roberts KG, et al. Development and validation of a highly sensitive and specific gene expression classifier to prospectively screen and identify B-Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) patients with a Philadelphia chromosome-like (“Ph-like” or “BCR-ABL1-Like”) signature for therapeutic targeting and clinical intervention. Blood. 2013;122(21):826. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boer JM, Marchante JR, Evans WE, et al. BCR-ABL1-like cases in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a comparison between DCOG/Erasmus MC and COG/St. Jude signatures. Haematologica. 2015;100(9):e354–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boer JM, Steeghs EM, Marchante JR, et al. Tyrosine kinase fusion genes in pediatric BCR-ABL1-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncotarget. 2017;8(3):4618–4628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts KG, Gu Z, Payne-Turner D, et al. High frequency and poor outcome of Philadelphia chromosome-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(4):394–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts KG, Li Y, Payne-Turner D, et al. Targetable kinase-activating lesions in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371(11):1005–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts KG, Pei D, Campana D, et al. Outcomes of children with BCR-ABL1-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with risk-directed therapy based on the levels of minimal residual disease. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3012–3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, Chen IM, et al. Rearrangement of CRLF2 is associated with mutation of JAK kinases, alteration of IKZF1, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, and a poor outcome in pediatric B-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(26):5312–5321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Veer A, Waanders E, Pieters R, et al. Independent prognostic value of BCR-ABL1-like signature and IKZF1 deletion, but not high CRLF2 expression, in children with B-cell precursor ALL. Blood. 2013;122(15):2622–2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.