Abstract

Background

For patients waitlisted for a deceased-donor kidney, hospitalization is associated with a lower likelihood of transplantation and worse posttransplant outcomes. However, individual-, neighborhood-, and regional-level risk factors for hospitalization throughout the waitlist period and specific causes of hospitalization in this population are unknown.

Methods

We used United States Renal Data System Medicare-linked data on patients waitlisted between 2005 and 2013 with continuous enrollment in Medicare Parts A & B (n=53 810) to examine the association between annual hospitalization rate and a variety of demographic, clinical, and social factors. We used multi-level multivariable ordinal logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (OR).

Results

Factors associated with significantly increased hospitalization rates among waitlisted individuals included older age, female sex, more years on dialysis prior to waitlisting, tobacco use, PRA>0, public insurance or no insurance at ESRD diagnosis, more regional acute care hospital beds, and urban residence (all p<0.05). Among patients’ dialysis-dependent when waitlisted, individuals with arteriovenous fistulas were significantly less likely than individuals with indwelling catheters or grafts to be hospitalized (OR=0.79 and 0.82, respectively, both p<0.001). The most common causes of hospitalization were complications related to devices, implants, and grafts; hypertension; and sepsis.

Conclusion

Individual- and regional-level variables were significantly associated with hospitalization while waitlisted, suggesting that personal, health-system, and geographic factors may impact patients’ risk. Conditions related to dialysis access and comorbidities were common hospitalization causes, underscoring the importance proper access management and care for additional chronic health conditions.

Introduction

Hospitalization while waitlisted for kidney transplantation is associated with poorer posttransplant outcomes1. In addition, hospitalization is associated with a lower likelihood of receiving a transplant among waitlisted patients2,3. Furthermore, hospitalization may add to increased Medicare costs, making it important to identify potentially modifiable factors. Despite the clinical and economic importance of pretransplant hospitalizations, factors associated with hospitalization throughout the waitlist period and causes of hospitalization have not been described in depth or included regional or neighborhood level factors.

It is important to consider individual- (eg, age, body mass index (BMI)) and regional-level (eg, neighborhood poverty, United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) region, rural vs. urban) factors because both contribute to healthcare utilization and health outcomes but may require different approaches to prevent or modify these outcomes4–6. Individual- (eg, socioeconomic status (SES)), and regional-level (eg, UNOS region, dialysis center) variables impact individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) from diagnosis to transplantation—there are variations in disease incidence6, referral for evaluation for kidney transplant7, placement on the waitlist8, time spent on the waitlist9,10, and receipt of an organ9,11 across levels of neighborhood and other geographic regions. Thus, both types of factors may impact the likelihood of hospitalization while waitlisted.

Hospitalization rate while waitlisted may serve as a surrogate for overall health; for other medical conditions, hospitalization is associated with severity of illness and lower quality of life12–14. However, hospitalization may also be an indicator of poor access to primary or preventive care15,16. The first step towards identifying which hospitalizations are preventable is to understand the causes of hospitalizations. However, hospitalization causes for individuals waitlisted for kidney transplant have not previously been described. This study’s purpose was to evaluate demographic, medical, and geographic factors associated with hospitalization while waitlisted for kidney transplantation and to describe the causes of hospitalization in this population.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Data Sources

The analysis included all adults (aged 18+ years) waitlisted for first renal allograft between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2013 who had continuous coverage by Medicare Parts A and B while waitlisted. Patient data came from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). Demographic and clinical information came from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medical Evidence form (CMS-2728), which is completed at the start of ESRD treatment. Transplant data came from the UNOS forms completed at the time of waitlisting and at transplantation. Hospitalization data were from CMS claims data. We linked American Community Survey (ACS) neighborhood poverty and education data (2005–2010); Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care data on acute care hospital beds per 1000 residents (2012), primary care physicians (PCPs) per 100 000 residents, and nephrologists per 100 000 residents (both 2011) per hospital service area (HSA)17; and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) county classification of rural-urban continuum (2013)18 to patients by residential zip code collected at ESRD diagnosis or time of CMS-2728 completion. A 1st quarter 2013 crosswalk file was used to link zip codes to counties and a 2012 crosswalk file was used to link zip codes to HSAs.

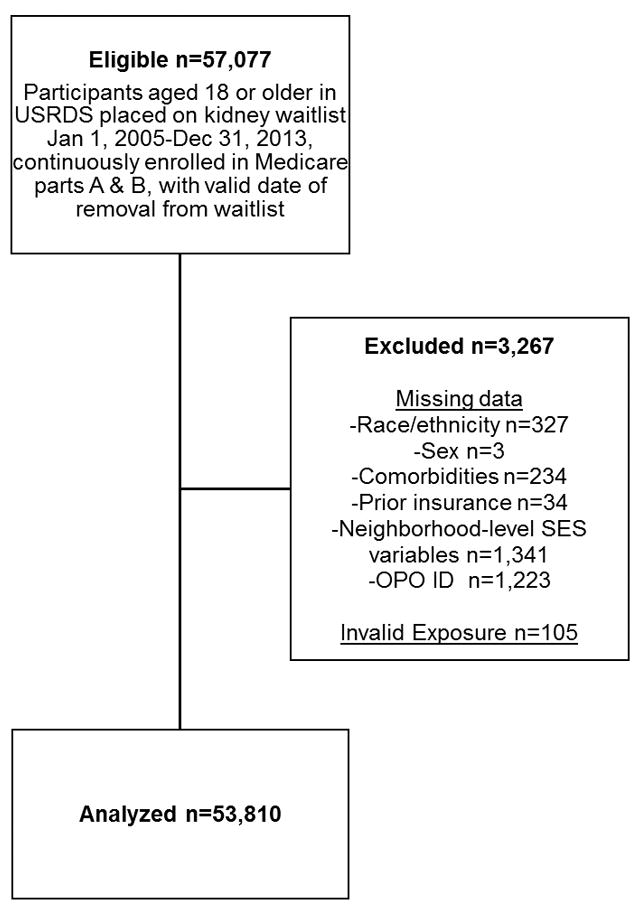

For inclusion, we considered 57 077 adults placed on the waitlist for first deceased-donor kidney transplant between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2013 with continuous Medicare coverage while waitlisted. This included both patients with ESRD and patients with CKD who were preemptively waitlisted. Patients were excluded if they were missing key information or had invalid hospitalization data. Exclusions by cause are outlined in Figure 1. The final study population included 53 810 individuals.

Figure 1.

Inclusion flow chart for study population of United States Renal Data System Patients 2005–2013.

Study Variables

The primary outcome was annual hospitalization rate after being waitlisted. Study participants were followed from the date of waitlisting until death, 30 days prior to transplant (deceased or living), removal from the waitlist for other reasons, or the end of the study period (December 31, 2013). Follow-up time was defined as the time from waitlisting until either transplant or removal from the waitlist due to death, inactivation, or other causes. Hospitalization rate was calculated as the number of hospitalizations per year while waitlisted up to 30 days prior to transplant, to exclude hospitalization associated with the transplant operation. Hospitalization rates were categorized as: no hospitalizations per year, >0–2 hospitalizations per year, and >2 hospitalizations per year.

The primary diagnosis for each hospitalization was assessed for up to an individual’s first 30 hospitalizations. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s Clinical Classification Software was used to categorize ICD-9 codes19. They were examined based on first-level categorization (most general), third-level (more detailed) categorization, and ICD-9-level (most detailed) categorization of diagnosis codes.

Demographic and medical factors during were the main exposures of interest. Individual-level variables included recipient race/ethnicity, age at waitlisting, peak panel reactive antibody (PRA), sex, blood type, willingness to accept an expanded donor criteria organ, years of dialysis prior to waitlisting, ESRD/CKD cause, BMI, history of cancer, smoking status, dialysis access type at first dialysis session, insurance at ESRD start or preemptive waitlisting, and employment at ESRD start or preemptive waitlisting. Race/ethnicity was categorized as nonHispanic white, nonHispanic black, Hispanic white, Hispanic black, Asian, and other races/ethnicities. Peak PRA was defined as the PRA listed as peak, the highest PRA listed, or, if both were missing, was imputed as zero (n=12). ESRD/CKD cause was categorized as diabetes, hypertension, kidney-related causes (ie, IgA nephropathy, polycystic kidney disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, or other types of glomerular nephritis), and other causes (eg, tumor, infection, uncategorized, etc.). Dialysis access type was categorized as arteriovenous fistula (AVF), arteriovenous graft, indwelling catheter, peritoneal, or other. Insurance and employment at ESRD diagnosis or preemptive waitlisting (ie, ESRD start) were assumed individual-level proxies of SES. Insurance and employment at ESRD start or preemptive waitlisting were obtained for everyone based on USRDS data. Employment was categorized as employed full-time, employed part-time, unemployed, retired, and other (included homemakers, students, medical leave of absence, and other).

Neighborhood area-level socioeconomic variables of neighborhood poverty and neighborhood education were calculated based on ACS data. Neighborhood poverty was estimated by the percentage of households with an annual income below the federal poverty level in each 5-digit zip code area and classified as <15%, 15–30%, and >30% of households below the federal poverty line. Neighborhood education was estimated by the percentage of adults with less than a high school level education in each 5-digit zip code area. It was dichotomized into areas with <85% of adults having graduated from high school and areas with ≥85%.

Larger area-level healthcare access-related variables used included acute care hospital beds per 1000 residents, PCPs per 100 000 residents, and nephrologists per 100 000 residents per HSA, all of which were categorized into above or below their median values (2.069, 70.3, and 2.27, respectively). In addition, whether an individual lived in an urban or rural area was dichotomized in accordance with the USDA’s groupings of metro (ie, urban) and nonmetro counties18.

Data Analysis

Chi-square and ANOVA tests were used to test for differences between baseline characteristics by hospitalization rate. We used multi-level ordinal logistic regression models with clustering of transplant centers within OPOs and random intercepts for both (SAS GLIMMIX) to estimate the odds ratios (OR) for the association between covariates and an increase in hospitalization rate. That is, the odds of either going from no annual hospitalizations to >0 annual hospitalizations or from 0–2 to >2 annual hospitalizations while waitlisted. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance at ESRD start or preemptive waitlisting, ESRD/CKD cause, BMI, cancer history, cigarette smoking, prior transplant, blood type, PRA, year of waitlisting (to account for differences in time at risk), years on dialysis prior to waitlisting, willingness to accept an expanded donor criteria organ, neighborhood poverty, and neighborhood education.

Because not all preemptively waitlisted individuals were dialysis-dependent, model 2 analyzed dialysis-dependent individuals in a model adjusted for the same variables as model 1 plus dialysis access type.

To assess for the association between healthcare capacity, healthcare access, and region and hospitalization, model 3 was adjusted for the same variables as model 1 plus acute care hospital beds, primary care physicians, and nephrologists per HSA and urban vs. nonurban county, and UNOS region.

As a sensitivity analysis, we studied 2 alternate parameterizations of hospitalization. First, we categorized hospitalization rate as a dichotomous variable. Second, we examined the average annual days hospitalized, which was categorized as 0, >0 to <5.25 (the median annual days hospitalized for those who were hospitalized), and ≥5.25. For the dichotomous categorization of hospitalization, 3 multi-level logistic regression models were used. For average annual days hospitalized, 3 multi-level ordinal logistic regression were used.

All models used complete case analysis. Analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC). p values of <0.05 were considered significant. The Emory University Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB00038140).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

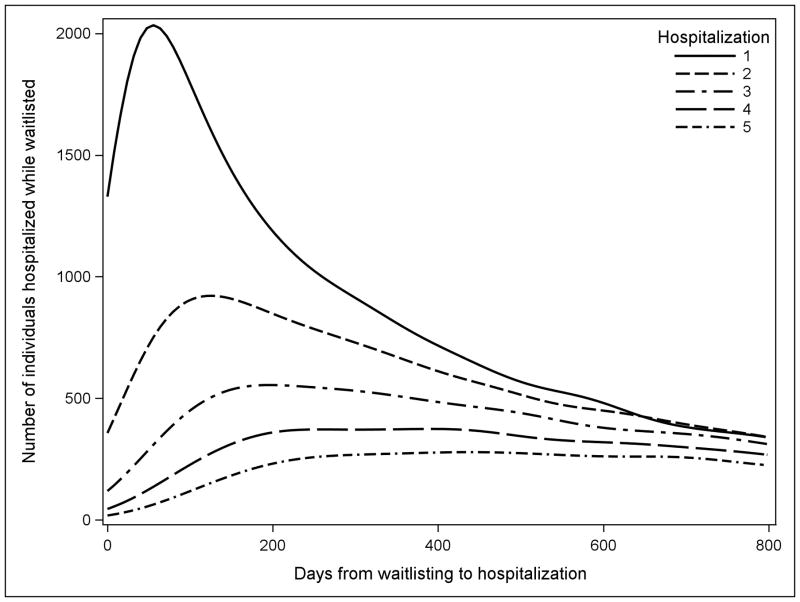

Overall 53 810 adults waitlisted for deceased-donor kidney transplant were included in this analysis, of whom 31 488 were hospitalized at least once (58.5%). Among those hospitalized while waitlisted, median time to first hospitalization was 286 days, to second hospitalization was 464 days, and to third hospitalization was 603 days (Figure 2). Individuals were waitlisted for a median of 1092 days (interquartile range (IQR): 451–1541). During the study period, 17 639 individuals were removed from the waitlist after receiving a deceased-donor transplant (32.8%), 5346 were removed after receiving a living donor transplant (9.9%), 5459 were removed from the waitlist because their condition deteriorated and they were no longer eligible for transplant (10.1%), and 9231 died while waitlisted for transplant (17.2%). Individuals who were black Hispanic, black nonHispanic, and white Hispanic race/ethnicity were most likely to be hospitalized while waitlisted (64.3%, 61.8%, and 60.9%, respectively vs. 55.2% for white nonHispanic, p<0.001). Most patients lived in an urban area (84.0%). Study variables stratified by hospitalization rate are presented in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Histogram of time to hospitalization after waitlisted for first 800 days of time on waitlist. First hospitalization for each individual is represented by the solid line and second through fifth hospitalizations are overlaid as various patterned lines. Most hospitalizations for individuals who will be hospitalized occur in roughly the first 2 years of waitlisting, and individuals hospitalized more than once are more likely to have these subsequent hospitalizations begin in this same period.

Table 1.

Distribution of individual- and neighborhood-level study variables stratified by hospitalization rate among patients with continuous Medicare coverage waitlisted for kidney transplant in the United States, 2005–2013.

| Variable | Overall | Hospitalizations/year | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0< and <=2 | >2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| n=53 810 | N=22 322 | N=22 058 | N=9430 | ||

| Age at Waitlisting (Mean, SD) | 54.5 (13.22) | 53.9 (13.66) | 54.7 (12.93) | 55.5 (12.75) | <0.001 |

| Female | 20 449 (38.00) | 7901 (35.40) | 8638 (39.16) | 3910 (41.46) | <0.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Asian | 2714 (5.04) | 1213 (5.43) | 1205 (5.46) | 296 (3.14) | <0.001 |

| Black Hispanic | 199 (0.37) | 71 (0.32) | 83 (0.38) | 45 (0.48) | |

| Black nonHispanic | 17 467 (32.46) | 6678 (29.92) | 7731 (35.05) | 3058 (32.43) | |

| Other | 863 (1.6) | 337 (1.51) | 402 (1.82) | 124 (1.31) | |

| White Hispanic | 9925 (18.44) | 3885 (17.40) | 4477 (20.3) | 1563 (16.57) | |

| White nonHispanic | 22 642 (42.08) | 10 138 (45.42) | 8160 (36.99) | 4344 (46.07) | |

| Blood type | |||||

| A | 17 628 (32.76) | 8002 (35.85) | 6562 (29.75) | 3064 (32.49) | <0.001 |

| B | 7893 (14.67) | 3067 (13.74) | 3430 (15.55) | 1396 (14.8) | |

| AB | 2176 (4.04) | 1119 (5.01) | 693 (3.14) | 364 (3.86) | |

| O | 26 113 (48.53) | 10 134 (45.4) | 11 373 (51.56) | 4606 (48.84) | |

| BMI | |||||

| Underweight | 1838 (3.42) | 789 (3.53) | 702 (3.18) | 347 (3.68) | <0.001 |

| Normal weight | 14 140 (26.28) | 6102 (27.34) | 5553 (25.17) | 2485 (26.35) | |

| Overweight | 16 702 (31.04) | 7029 (31.49) | 6799 (30.82) | 2874 (30.48) | |

| Obese | 21 130 (39.27) | 8402 (37.64) | 9004 (40.82) | 3724 (39.49) | |

| ESRD/CKD Cause | |||||

| Diabetes | 23 580 (43.82) | 8466 (37.93) | 10 117 (45.87) | 4997 (52.99) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 13 609 (25.29) | 6097 (27.31) | 5595 (25.36) | 1917 (20.33) | |

| Kidney-related | 10 277 (19.10) | 4888 (21.90) | 3990 (18.09) | 1399 (14.84) | |

| Other | 6344 (11.79) | 2871 (12.86) | 2356 (11.54) | 1117 (12.21) | |

| History of Cancer | 1656 (3.08) | 675 (3.02) | 657 (2.98) | 324 (3.44) | 0.080 |

| Tobacco Smoker | 2865 (5.32) | 1077 (4.82) | 1177 (5.34) | 611 (6.48) | <0.001 |

| PRA | |||||

| 0 | 33 918 (63.03) | 14 841 (66.49) | 13 151 (59.62) | 5926 (62.84) | <0.001 |

| >0 and ≤80 | 15 711 (29.20) | 6088 (27.27) | 7013 (31.79) | 2610 (27.68) | |

| >80 | 4181 (7.77) | 1393 (6.24) | 1894 (8.59) | 894 (9.48) | |

| Years on Dialysis at Waitlisting | |||||

| 0 | 1043 (1.94) | 525 (2.35) | 360 (1.63) | 158 (1.68) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 20 859 (38.76) | 9361 (41.94) | 8174 (37.06) | 3324 (35.25) | |

| 2 | 14 049 (26.11) | 5699 (25.53) | 5916 (26.82) | 2434 (25.81) | |

| 3+ | 17 859 (33.19) | 6737 (30.18) | 7608 (34.49) | 3514 (37.26) | |

| Access type | |||||

| AVF | 6824 (12.68) | 3185 (14.27) | 2830 (12.83) | 809 (8.58) | <0.001 |

| Catheter | 27 136 (50.43) | 11 578 (51.87) | 10 971 (49.74) | 4587 (48.64) | |

| Graft | 1260 (2.34) | 466 (2.09) | 574 (2.6) | 220 (2.33) | |

| Peritoneal | 5696 (10.59) | 2522 (11.30) | 2251 (10.2) | 923 (9.79) | |

| Other/unknown | 12 893 (23.96) | 4570 (20.47) | 5432 (24.63) | 2891 (30.66) | |

| Listing year | |||||

| 2005 | 5482 (10.19) | 2121 (9.50) | 2095 (9.5) | 1266 (13.43) | <0.001 |

| 2006 | 5968 (11.09) | 2223 (9.96) | 2457 (11.14) | 1288 (13.66) | |

| 2007 | 6006 (11.16) | 2058 (9.22) | 2644 (11.99) | 1304 (13.83) | |

| 2008 | 5960 (11.08) | 2038 (9.13) | 2742 (12.43) | 1180 (12.51) | |

| 2009 | 6121 (11.38) | 1922 (8.61) | 2900 (13.15) | 1299 (13.78) | |

| 2010 | 6166 (11.46) | 1910 (8.56) | 2982 (13.52) | 1274 (13.51) | |

| 2011 | 5727 (10.64) | 2173 (9.73) | 2658 (12.05) | 896 (9.5) | |

| 2012 | 5861 (10.89) | 2910 (13.04) | 2318 (10.51) | 633 (6.71) | |

| 2013 | 6519 (12.11) | 4967 (22.25) | 1262 (5.72) | 290 (3.08) | |

| Insurance at ESRD Start | |||||

| Employer/Private | 9816 (18.24) | 4386 (19.20) | 3807 (17.26) | 1723 (18.27) | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 15 476 (28.76) | 5627 (25.21) | 6773 (30.71) | 3076 (32.62) | |

| Medicare | 14 035 (26.08) | 5770 (25.85) | 5702 (25.85) | 2563 (27.18) | |

| No insurance | 9430 (17.52) | 4258 (19.08) | 3816 (17.3) | 1356 (14.38) | |

| Other | 5053 (9.39) | 2381 (10.67) | 1960 (8.89) | 712 (7.55) | |

| Percent of households below poverty line | |||||

| <15% | 5173 (9.61) | 2087 (9.35) | 2177 (9.87) | 909 (9.64) | <0.001 |

| 15–30% | 36 744 (68.28) | 15482 (69.36) | 14899 (67.54) | 6363 (67.48) | |

| >30% | 11 893 (22.10) | 4753 (21.29) | 4982 (22.59) | 2158 (22.88) | |

| Adults with HS diploma | |||||

| ≥85% | 25 816 (47.98) | 11 120 (49.82) | 10 221 (46.34) | 4475 (47.45) | <0.001 |

| <85% | 27 994 (52.02) | 11 202 (50.18) | 11 837 (53.66) | 4955 (52.55) | |

| Willing to accept expanded criteria organ | 30 677 (57.01) | 12 540 (56.18) | 12 654 (57.37) | 5483 (58.14) | 0.002 |

| Urban residence (vs. rural)1 | 44 929 (84.00) | 18 347 (82.62) | 16 999 (84.68) | 9583 (85.52) | <0.001 |

| Hospital beds per 1000 HSA residents (mean, SD)2 | 2.18 (0.80) | 2.17 (0.79) | 2.18 (0.79) | 2.21 (0.81) | <0.001 |

| PCPs per 100 000 HSA residents (mean, SD)2 | 73.78 (20.81) | 73.63 (20.31) | 73.68 (21.24) | 74.26 (20.99) | 0.022 |

| Nephrologists per 100 000 HSA residents (mean, SD)2 | 2.46 (1.20) | 2.42 (1.18) | 2.47 (1.20) | 2.51 (1.23) | <0.001 |

| Average LOS (mean, SD) | 5.8 (5.6) | N/A | 5.2 (5.61) | 7 (5.45) | <0.001 |

All values N (%) unless otherwise specified. Percentages may not sum to 100% because of rounding. 1Missing for 319 subjects. 2Missing for 117 subjects.

Abbreviations: hosp/yr, hospitalizations per year; SD, standard deviation; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HS, high school; HSA, hospital service area; LOS, hospital length of stay; PCPs, primary care physicians; PRA, panel reactive antibody.

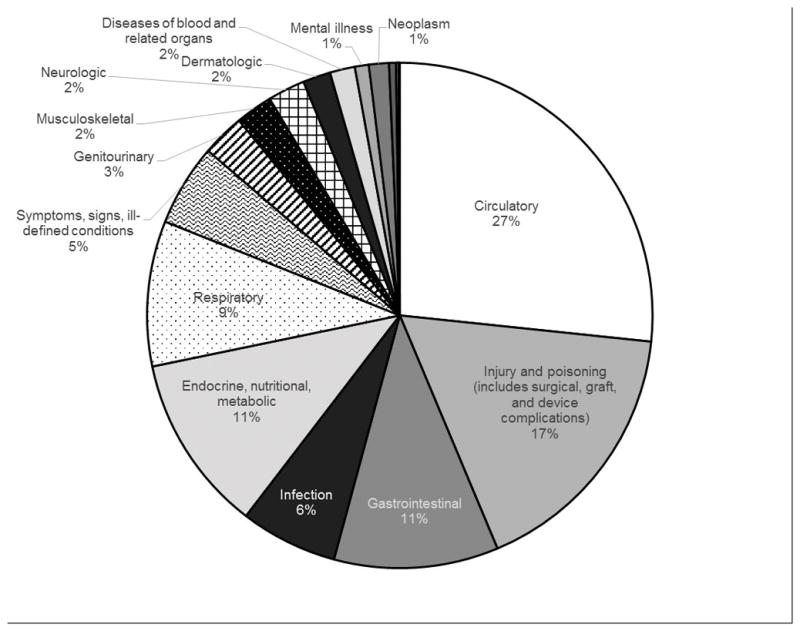

There were 157 859 hospitalizations during the study period, of which primary diagnoses were obtained for 156 007. The median hospitalization rate among patients waitlisted for kidney transplantation was 0.4 (IQR 0–1.4, mean 1.2, Table 2). The most common level-1 diagnosis category causes of hospitalization were for diseases of the circulatory system, injuries and poisonings (category includes surgical, medical, device, and graft complications), and endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (26.7%, 17.0%, and 11.3% respectively, Figure 3). The most common level-3 diagnosis category causes of hospitalization were complication of device, implant, or graft; hypertension; and septicemia (12.2%, 6.1%, and 5.8%, respectively, Table 3).

Table 2.

Annual hospitalization rates by UNOS region among patients with continuous Medicare coverage waitlisted for kidney transplant in the United States, 2005–2013. (SD=standard deviation. IQR=interquartile range)

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1.19 (2.71) | 0.4 (0–1.4) |

| UNOS Region | ||

| 1 | 1.53 (3.63) | 0.5 (0–1.9) |

| 2 | 1.28 (2.34) | 0.4 (0–1.6) |

| 3 | 1.15 (2.67) | 0.4 (0–1.3) |

| 4 | 1.17 (2.58) | 0.4 (0–1.4) |

| 5 | 1.10 (2.36) | 0.3 (0–1.2) |

| 6 | 0.81 (2.87) | 0.0 (0–0.9) |

| 7 | 1.33 (2.80) | 0.4 (0–1.6) |

| 8 | 1.16 (2.55) | 0.3 (0–1.3) |

| 9 | 1.29 (2.40) | 0.5 (0–1.6) |

| 10 | 1.29 (3.13) | 0.3 (0–1.5) |

| 11 | 1.11 (3.18) | 0.3 (0–1.3) |

Figure 3.

Level-1 primary diagnoses for the cause of hospitalizations of waitlisted individuals during study period (2005–2013). The primary cause of hospitalizations for waitlisted individuals was complications of a device, implant, or graft.

Table 3.

Top 50 most common level-3 primary ICD-9 diagnoses for hospitalization causes of waitlisted individuals during study period.

| Diagnosis category | Overall frequency (n, %) |

|---|---|

| Complication of device, implant, or graft | 17 894 (12.17) |

| Hypertension with complications and secondary hypertension | 8919 (6.07) |

| Septicemia (except in labor) | 8495 (5.78) |

| Congestive heart failure; nonhypertensive | 8231 (5.60) |

| Pneumonia (except that caused by TB or STD) | 6268 (4.26) |

| Complications of surgical procedures or medical care | 4661 (3.17) |

| Coronary atherosclerosis and other heart disease | 4129 (2.81) |

| Rehabilitation care; fitting of prostheses; and adjustment of devices | 3757 (2.56) |

| Hyperpotassemia | 3654 (2.49) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 3639 (2.48) |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | 3282 (2.23) |

| Other fluid and electrolyte disorders | 3259 (2.22) |

| Diabetes with other manifestations | 3052 (2.08) |

| Nonspecific chest pain | 2779 (1.89) |

| Respiratory failure | 2616 (1.78) |

| Diabetes with neurological manifestations | 2117 (1.44) |

| Acute cerebrovascular disease | 2061 (1.40) |

| Cellulitis and abscess | 2003 (1.36) |

| Diabetes with circulatory manifestations | 1951 (1.33) |

| Peripheral and visceral atherosclerosis | 1723 (1.17) |

| Deficiency and other anemia | 1612 (1.10) |

| Other circulatory disease | 1527 (1.04) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1328 (0.90) |

| Gangrene | 1242 (0.84) |

| Other liver diseases | 1218 (0.83) |

| Other and unspecified lower respiratory disease | 1213 (0.83) |

| Peritonitis and intestinal abscess | 1171 (0.80) |

| Other central nervous system disorders | 1151 (0.78) |

| Hemorrhage of gastrointestinal tract | 1118 (0.76) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1117 (0.76) |

| Urinary tract infections | 1098 (0.75) |

| Peri; endo; and myocarditis; cardiomyopathy (except that caused by TB or STD) | 1046 (0.71) |

| Pleurisy; pleural effusion | 1046 (0.71) |

| Gastritis and duodenitis | 918 (0.62) |

| Abdominal pain | 872 (0.59) |

| Diverticulosis and diverticulitis | 832 (0.57) |

| Obstructive chronic bronchitis | 832 (0.57) |

| Diabetes with ketoacidosis or uncontrolled diabetes | 818 (0.56) |

| Other and unspecified gastrointestinal disorders | 815 (0.55) |

| Intestinal obstruction without hernia | 812 (0.55) |

| Other diseases of kidney and ureters | 807 (0.55) |

| Other disorders of stomach and duodenum | 781 (0.53) |

| Heart valve disorders | 779 (0.53) |

| Diabetes with renal manifestations | 740 (0.50) |

| Fracture of neck of femur (hip) | 715 (0.49) |

| Syncope | 713 (0.48) |

| Fracture of lower limb | 699 (0.48) |

| Hemorrhage from gastrointestinal ulcer | 695 (0.47) |

| Hypovolemia | 676 (0.46) |

| Fever of unknown origin | 657 (0.45) |

The most common ICD-9 codes of the cause of hospitalizations were 996.73 (“Other complications due to renal dialysis device, implant, and graft”, 4.1% of hospitalizations), 486 (“Pneumonia, organism not otherwise specified (NOS)”, 3.5%), 403.91 (“Hypertensive chronic kidney disease, unspecified, with chronic kidney disease stage V or end stage renal disease”, 3.2%), 038.9 (“Septicemia, NOS”, 3.1%), and 996.62 (“Infection and inflammatory reaction due to other vascular device, implant, and graft”, 2.8%). In addition, 1.2% of all hospitalizations were attributed to “infection and inflammatory reaction due to peritoneal dialysis catheter” (ICD-9 code 996.68).

Risk Factors for Hospitalization

During the study period, 58.5% of individuals were hospitalized at least once. In unadjusted analyses, compared to their respective referent categories (Table 4) black nonHispanic, black Hispanic, and white Hispanic race/ethnicity, female sex, older age, public insurance at diagnosis of ESRD/prelisting, diabetes as cause of ESRD/CKD, obese BMI, tobacco use, more years of dialysis at time of waitlisting, elevated PRA, living in a zip code with higher adult education, living in a zip code with higher rates of household poverty, willingness to accept an expanded donor criteria organ, urban residence, higher per capita acute care hospital beds, higher per capita PCPs, and higher per capita nephrologists were all significantly associated with increased hospitalization while waitlisted (all p<0.05, data not shown). Asian race, no insurance or other insurance type at waitlisting, AB or A blood type, and intrinsic kidney disease as cause of ESRD/CKD were all associated with decreased hospitalization while waitlisted (all p<0.05, data not shown, ref. groups in Table 4).

Table 4.

Estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for associations between parameters and increase in hospitalization rate category (0 to >0 hospitalizations/year or 0–2 to >2 hospitalizations/year) from multi-level ordinal logistic regression models with clustering by transplant center and OPO.

| Parameter | Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Model 1 N=53 810 |

Model 2 (dialysis-dependent) N=52 760 |

Model 3 (regional health resources) N=53 495 |

||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age (Ref. ≤40) | ||||||

| 41–55 | 1.079 | (1.024, 1.137) | 1.094 | (1.037, 1.153) | 1.080 | (1.025, 1.138) |

| 56–69 | 1.163 | (1.101, 1.228) | 1.185 | (1.121, 1.252) | 1.166 | (1.104, 1.231) |

| 70–90 | 1.123 | (1.040, 1.212) | 1.154 | (1.068, 1.248) | 1.124 | (1.041, 1.214) |

| Female (Ref. Male) | 1.120 | (1.080, 1.160) | 1.110 | (1.071, 1.151) | 1.121 | (1.082, 1.162) |

| Race/ethnicity (Ref. White nonHispanic) | ||||||

| Black nonHispanic | 1.007 | (0.964, 1.052) | 1.006 | (0.963, 1.051) | 0.986 | (0.943, 1.031) |

| Black Hispanic | 1.015 | (0.776, 1.328) | 1.022 | (0.781, 1.338) | 0.988 | (0.755, 1.294) |

| White Hispanic | 0.837 | (0.791, 0.886) | 0.838 | (0.792, 0.887) | 0.824 | (0.779, 0.873) |

| Asian | 0.759 | (0.700, 0.823) | 0.760 | (0.700, 0.824) | 0.754 | (0.695, 0.818) |

| Other | 0.909 | (0.792, 1.043) | 0.917 | (0.797, 1.055) | 0.907 | (0.789, 1.044) |

| BMI (Ref. normal) | ||||||

| Underweight | 1.017 | (0.926, 1.118) | 1.023 | (0.931, 1.125) | 1.017 | (0.926, 1.118) |

| Overweight | 0.996 | (0.953, 1.040) | 1.002 | (0.959, 1.047) | 0.995 | (0.952, 1.039) |

| Obese | 1.031 | (0.988, 1.076) | 1.04 | (0.997, 1.086) | 1.029 | (0.986, 1.073) |

| Years on dialysis at waitlisting (Ref. 0) | 1.193 | (1.170, 1.217) | 1.18 | (1.154, 1.207) | 1.193 | (1.17, 1.216) |

| ESRD Cause (Ref. Other) | ||||||

| Diabetes | 1.417 | (1.340, 1.499) | 1.420 | (1.342, 1.503) | 1.417 | (1.340, 1.499) |

| Hypertension | 0.958 | (0.903, 1.017) | 0.962 | (0.906, 1.022) | 0.954 | (0.899, 1.013) |

| Kidney disease | 0.898 | (0.845, 0.955) | 0.904 | (0.850, 0.962) | 0.899 | (0.845, 0.956) |

| Cancer history | 1.091 | (0.992, 1.200) | 1.105 | (1.004, 1.216) | 1.092 | (0.993, 1.201) |

| Tobacco smoker | 1.328 | (1.235, 1.429) | 1.327 | (1.233, 1.429) | 1.331 | (1.237, 1.432) |

| Insurance at ESRD start (Ref. Private) | ||||||

| Medicaid | 1.461 | (1.388, 1.539) | 1.489 | (1.413, 1.569) | 1.469 | (1.395, 1.547) |

| Medicare | 1.274 | (1.207, 1.343) | 1.296 | (1.228, 1.368) | 1.278 | (1.211, 1.348) |

| Other | 0.940 | (0.879, 1.005) | 0.945 | (0.883, 1.011) | 0.943 | (0.882, 1.008) |

| None | 1.083 | (1.023, 1.147) | 1.075 | (1.014, 1.138) | 1.086 | (1.026, 1.150) |

| PRA (Ref. 0) | ||||||

| >0 and ≤80 | 1.076 | (1.036, 1.118) | 1.076 | (1.035, 1.118) | 1.079 | (1.038, 1.120) |

| >80 | 1.375 | (1.289, 1.467) | 1.370 | (1.283, 1.463) | 1.379 | (1.292, 1.471) |

| Listing year (Ref. 2013) | ||||||

| 2005 | 4.753 | (4.396, 5.139) | 4.560 | (4.166, 4.991) | 4.763 | (4.404, 5.151) |

| 2006 | 4.743 | (4.394, 5.119) | 4.650 | (4.285, 5.047) | 4.744 | (4.394, 5.121) |

| 2007 | 5.115 | (4.741, 5.518) | 5.108 | (4.726, 5.522) | 5.109 | (4.735, 5.514) |

| 2008 | 5.030 | (4.662, 5.428) | 5.093 | (4.714, 5.501) | 5.013 | (4.646, 5.411) |

| 2009 | 5.785 | (5.363, 6.239) | 5.860 | (5.429, 6.326) | 5.798 | (5.375, 6.254) |

| 2010 | 5.941 | (5.509, 6.406) | 6.006 | (5.566, 6.481) | 5.945 | (5.512, 6.412) |

| 2011 | 4.627 | (4.286, 4.996) | 4.637 | (4.291, 5.009) | 4.653 | (4.309, 5.025) |

| 2012 | 3.116 | (2.885, 3.367) | 3.119 | (2.885, 3.372) | 3.121 | (2.889, 3.373) |

| Blood Type (Ref. O) | ||||||

| AB | 0.663 | (0.608, 0.724) | 0.660 | (0.604, 0.721) | 0.660 | (0.604, 0.721) |

| A | 0.824 | (0.794, 0.855) | 0.824 | (0.794, 0.856) | 0.823 | (0.793, 0.854) |

| B | 0.999 | (0.952, 1.048) | 0.999 | (0.951, 1.049) | 0.996 | (0.948, 1.045) |

| Percent of households below poverty line (Ref. <15%) | 0.970 | (0.933, 1.010) | 0.969 | (0.931, 1.009) | 0.988 | (0.947, 1.031) |

| ≥85% adults with HS diploma (Ref. <85%) | 1.020 | (0.974, 1.067) | 1.015 | (0.969, 1.062) | 1.020 | (0.974, 1.068) |

| Willing to accept expanded criteria organ | 0.966 | (0.928, 1.005) | 0.963 | (0.925, 1.003) | 0.964 | (0.926, 1.003) |

| Dialysis access type (Ref. catheter) | ||||||

| AVF | 0.791 | (0.751, 0.834) | ||||

| Graft | 0.960 | (0.862, 1.070) | ||||

| Peritoneal | 1.031 | (0.974, 1.092) | ||||

| Other | 1.032 | (0.976, 1.091) | ||||

| Urban county of residence (Ref. rural) | 1.185 | (1.124, 1.249) | ||||

| Hospital beds ≤2.069/1000 persons (Ref. >2.069) | 0.926 | (0.888, 0.966) | ||||

| PCPs ≤70.3/100 000 persons (Ref. >70.3) | 1.007 | (0.968, 1.047) | ||||

| Nephrologists ≤2.27/100 000 persons (Ref. >2.27) | 1.022 | (0.984, 1.062) | ||||

| UNOS region (Ref. 11) | ||||||

| 1 | 1.448 | (0.892, 2.352) | ||||

| 2 | 1.247 | (0.943, 1.648) | ||||

| 3 | 1.113 | (0.854, 1.451) | ||||

| 4 | 1.181 | (0.874, 1.594) | ||||

| 5 | 1.109 | (0.852, 1.445) | ||||

| 6 | 0.819 | (0.565, 1.189) | ||||

| 7 | 1.192 | (0.890, 1.596) | ||||

| 8 | 1.027 | (0.741, 1.425) | ||||

| 9 | 1.357 | (0.986, 1.867) | ||||

| 10 | 1.083 | (0.823, 1.426) | ||||

Abbreviations: AVF, arteriovenous fistula; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HS, high school; HSA, hospital service area; LOS, hospital length of stay; PCPs, primary care physicians; PRA, panel reactive antibody; Ref., referent group.

In model 1, female sex, older age, public insurance or no insurance at diagnosis of ESRD/prelisting, diabetes as cause of ESRD/CKD, tobacco use, more years of dialysis at time of waitlisting, and PRA >0 were all significantly associated with increased hospitalization while waitlisted (all p<0.05, Table 4). Asian or white Hispanic race, intrinsic kidney disease as cause of ESRD/CKD, and blood type A or AB were all associated with increased hospitalization while waitlisted (all p<0.05, Table 4).

Dialysis-dependent Group Analysis

The 98.1% of individuals in the population were dialysis-dependent at waitlisting (n=52 760). Compared to individuals preemptively waitlisted without dialysis, dialysis-dependent individuals were more likely to be hospitalized while waitlisted (OR=1.38, p<0.0001, data not shown). In model 2, which included dialysis access type, individuals with AVF were significantly less likely to be hospitalized than individuals with indwelling catheters (OR=0.79, p<0.001, Table 4). Individuals with arteriovenous grafts or on peritoneal dialysis were not significantly less likely to be hospitalized than those with indwelling catheters (ORs=0.96 and 1.03, p=0.46 and 0.27, respectively, Table 4).

Regional Geographic Characteristics and Healthcare Resources

Median hospitalization rate among patients waitlisted for a kidney transplant varied across UNOS region from 0 to 0.5 (Table 2). However, in the fully adjusted model (model 3) including UNOS region, region was not significantly associated with hospitalization (Table 4). Living in an urban area compared to a more rural area was associated with hospitalization (OR=1.18, p<0.001, Table 4). Living in an HSA with lower than the median number of acute care hospital beds per 1000 residents was associated with lower likelihood of hospitalization (OR=0.93, p<0.001), but fewer per capita PCPs and nephrologists were not associated with hospitalization (Table 4).

Sensitivity Analysis

In the sensitivity analysis, dichotomizing hospitalization (ever vs. never) and measuring hospitalization as days hospitalized per year yielded similar results to the use of 3 categorizes of hospitalization rate. The only estimate to change direction and significance was in model 3 with hospitalization dichotomized. In that model, the estimate of the OR of increased hospitalization category for a black nonHispanic individual compared to a white nonHispanic individual was 1.10 (p<0.001), whereas it was 0.99 (p=0.535) with hospitalization rate categorized into 3 groups (Table 4). No other estimates changed in both direction and significance.

Discussion

In this study of US adults waitlisted for deceased-donor kidney transplantation, almost 60% of individuals were hospitalized while on the waiting list during the 9-year study period. Though the causes were diverse, hospitalizations related to dialysis access, underlying cardiovascular disease, and infections were common. There was also multiple individual- and area-level variables that were associated with a greater likelihood of higher hospitalization rate while waitlisted. Hospitalization is common among individuals waitlisted for kidney transplant and is associated with numerous modifiable risk factors, which suggest that interventions to decrease potentially preventable admissions in this population may be appropriate.

Hospitalization for waitlisted individuals has documented associations with negative outcomes, including higher mortality while waitlisted3, lower likelihood of receiving a transplant2 and higher likelihood of posttransplant complications20. In addition, hospitalizations may increase total medical costs 21. Therefore, it is important to develop interventions for waitlisted individuals to prevent hospitalization. Many of the common causes of hospitalization for waitlisted individuals, such as graft complications, heart failure exacerbation, and diabetes-related issues, were expected given the existing comorbidities of waitlisted individuals. Furthermore, some common causes of hospitalization, such as pneumonia, may be more common among patients with CKD/ESRD21. However, we could not determine whether some hospitalizations were preventable. Ronksley et al, have begun exploring the possibilities for assessing preventable hospitalizations among nondialysis-dependent patients with CKD16. Yet when applied to a dialysis-dependent ESRD population, many indicators they consider (eg, hyperkalemia) center on the quality of dialysis and adherence to dialysis rather than the overall ambulatory care quality. An alternative set of indicators and benchmarks would be necessary for patients waitlisted for kidney transplantation.

Our work identified both modifiable and nonmodifiable factors associated with hospitalization during the entire waitlist period. Two modifiable dialysis-related factors associated with greater likelihood of hospitalization were years on dialysis prior to waitlisting and dialysis access type. In a previous study by our group that examined hospitalizations during the first year on the waitlist, years on dialysis prior to waitlisting was a significant risk factor3. Longer time on dialysis prior to waitlisting may negatively impact an individual’s health status by the time they are waitlisted because of the physiologic burden of dialysis. There is ongoing work to encourage equitable and early evaluation of individuals for transplantation22, and our study supports this endeavor. Initial dialysis access type was also a significant risk factor for hospitalization, with individuals with indwelling catheters faring worse than those with AVF, as expected based on known risks of catheter use23,24. This indicates that preemptive placement of an AVF may be an effective method of preventing hospitalizations. An additional modifiable risk factor we identified was tobacco smoking, which was associated with a substantially increased risk of hospitalization. Prior studies have linked tobacco consumption posttransplant to negative cardiovascular and graft-related outcomes25,26, and our study suggests that pretransplant tobacco cessation remains an important goal for all patients.

Some variables that were associated with increased hospitalization rate may be proxies for other factors, such as PRA. PRA>0 was associated with a significantly increased risk of hospitalization, indicating that more highly sensitized individuals had a higher likelihood of hospitalization than less sensitized individuals. PRA increases in individuals who receive multiple prior transfusions or other exposures to foreign antigens. Among dialysis patients, those with more comorbidities may be more likely to be selected for transfusion27, suggesting that these individuals may be sicker at baseline. Unfortunately, this also increases the likelihood of alloimmunization and the difficulty of finding a suitable organ match28 and leaves these individuals waiting longer for an organ.

Unadjusted analyses suggested differences in hospitalization rate between UNOS regions, but after controlling for clustering by transplant center and OPO and adjusting for the degree of rurality of individuals’ counties of residence, there were no persistent significant differences between UNOS regions. In the U.S., the OPO region where a patient resides is a significant factor in time spent on the waitlist29. In our study, the significant association between increased hospitalization and urban counties was also demonstrated in the increased likelihood of hospitalization in HSAs with higher numbers of hospital beds per capita. In a posthoc analysis, rural residence was associated with shorter length of stay, suggesting that individuals waitlisted for transplant who live in rural areas may experience less severe acute illness than their urban counterparts. Interestingly, outpatient resources as measured by PCPs and nephrologists per capita were not significantly associated with hospitalization, and thus the potential for prevention of hospitalization by increasing outpatient resources is unclear.

There were multiple other factors that we found were associated with hospitalization among patients waitlisted for a kidney transplant, including race, public insurance at ESRD diagnosis (a marker of low SES), and female sex. Racial disparities in kidney transplantation are well documented 30,31. However, in this study after adjusting for covariates, black individuals were not more likely to be hospitalized while waitlisted. We added to prior work by documenting that white Hispanic and Asian individuals were significantly less likely to be hospitalized while waitlisted. Like racial disparities in hospitalization, SES-related disparities in hospitalization while waitlisted are consistent with what is known about other kidney transplant-related outcomes among low SES individuals, including higher waitlist mortality and increased posttransplant morbidity and mortality (Reviewed in 32). These differences may be because despite eligibility for Medicare coverage, low SES individuals with ESRD may face geographic33 and other barriers that contribute to decreased survival among ESRD patients34. The disparities we observed in hospitalization by sex (ie, females more likely to be hospitalized) are more difficult to explain. Possible hypotheses include greater issues with nonadherence35,36, less guideline-based care by healthcare providers35, or greater severity of illness37.

This study has multiple strengths. This is the first study to examine the detailed causes of hospitalization while waitlisted for kidney transplant and to assess for potential risk factors for hospitalization while waitlisted. We had a large study population, which allowed us to analyze hospitalization causes across multiple regions and many covariates, including a detailed assessment of racial/ethnic groups. Furthermore, USRDS data have high follow-up rates38, making our dataset nearly complete with regard to key exposures and outcomes.

There are limitations of this study. Because we needed complete hospitalization records during the study period, our study population was limited to individuals with continuous Medicare parts A and B coverage, which may have caused a selection bias. This was also an observational study, and there may be unmeasured variables confounding the measured associations. Furthermore, for some variables, such as neighborhood poverty, BMI, and dialysis access type, we only had access to 1 measurement, and these variables may have changed over the study period. In addition, our dataset did not include preventive care measures or baseline health status among waitlisted individuals. The study relied upon billing codes to analyze the cause of hospitalization, a common yet limited method, and as such may be biased by coding errors or trends. Compared with prior work by our group3, for this study we utilized a rate of number of hospitalizations per year rather than a rate of days hospitalized per year because we were interested in frequency of hospitalization. In our sensitivity analysis we analyzed days hospitalized per year and had similar findings.

This study is the first that we are aware of to examine the causes of hospitalization while waitlisted for kidney transplant and their association with potential risk factors throughout the waitlist period. We report that hospitalization is common and associated with conditions linked to CKD, dialysis, and related comorbidities. However, it is difficult to determine which of these hospitalizations may have been preventable through improved outpatient management or other interventions. We also report that geographic, demographic, and SES-related factors remain risk factors for hospitalization, even after adjusting for other variables, but that potentially modifiable risk factors, such as duration of dialysis prior to waitlisting, dialysis access type, and smoking may also play a role. Further studies should identify markers of preventable hospitalization for this population to better assess preventive care quality and should determine if targeting modifiable risk factors reduces hospitalization among individuals waiting for kidney transplantation.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by Bristol Myers Squibb Grant #IM103-326 (R.E.P.). The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way, should be official policy or interpretation of the US government.

This work was supported in part by Bristol Myers Squibb Grant #IM103-326 (R.E.P. and A.B.A.) The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way, should be official policy or interpretation of the US government. The data on primary care physician, nephrologist, and acute care hospital access set forth in this publication was obtained from The Dartmouth Atlas, which is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute, under award number UL1TR001086 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Abbreviations

- ACS

American Community Survey

- AHRQ

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- AVF

arteriovenous fistula

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- HSA

hospital service area

- IQR

interquartile range

- NOS

not otherwise specified

- OPO

organ procurement organization

- OR

odds ratio

- PCP

primary care physician

- PRA

panel reactive antibody

- SES

socioeconomic status

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- USDA

United States Department of Agriculture

- USRDS

United States Renal Data System

Footnotes

Authorship: KLN, and REP designed the study. ABA, SOP, RJL, and RZ provided subject-area expertise that was essential for the intellectual content of the work. KLN, conducted the analysis. All authors provided feedback on the analytic methods and interpretation of results. KLN wrote the manuscript. All authors read, edited, and revised the manuscript. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lynch RJ, Zhang R, Patzer RE, Larsen CP, Adams AB. Waitlist hospital admissions predict resource utilization and survival after renal transplantation. Ann Surg. 2016;264(6):1168–1173. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman KL, Fedewa SA, Jacobson MH, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between hospitalization and kidney transplantation among waitlisted end-stage renal disease patients. Transplantation. 2016;100(12):2735–2745. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch RJ, Zhang R, Patzer RE, Larsen CP, Adams AB. First-year waitlist hospitalization and subsequent waitlist and transplant outcome. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(4):1031–1041. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1973;51(1):95–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vart P, Gansevoort RT, Joosten MM, Bultmann U, Reijneveld SA. Socioeconomic disparities in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(5):580–592. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholas SB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Norris KC. Socioeconomic disparities in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22(1):6–15. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patzer RE, Plantinga LC, Paul S, et al. Variation in dialysis facility referral for kidney transplantation among patients with end-stage renal disease in Georgia. JAMA. 2015;314(6):582–594. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patzer RE, Amaral S, Wasse H, Volkova N, Kleinbaum D, McClellan WM. Neighborhood poverty and racial disparities in kidney transplant waitlisting. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(6):1333–1340. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis AE, Mehrotra S, McElroy LM, et al. The extent and predictors of waiting time geographic disparity in kidney transplantation in the United States. Transplantation. 2014;97(10):1049–1057. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000438623.89310.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellison MD, Edwards LB, Edwards EB, Barker CF. Geographic differences in access to transplantation in the United States. Transplantation. 2003;76(9):1389–1394. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000090332.30050.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill JS, Hendren E, Dong J, Johnston O, Gill J. Differential association of body mass index with access to kidney transplantation in men and women. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(5):951–959. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08310813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niewoehner DE. The impact of severe exacerbations on quality of life and the clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 2006;119(10 Suppl 1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynolds MR, Morais E, Zimetbaum P. Impact of hospitalization on health-related quality of life in atrial fibrillation patients in Canada and the United States: results from an observational registry. Am Heart J. 2010;160(4):752–758. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mapes DL, Lopes AA, Satayathum S, et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Kidney Int. 2003;64(1):339–349. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, et al. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274(4):305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ronksley PE, Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, et al. Potentially preventable hospitalization among patients with CKD and high inpatient use. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(11):2022–2031. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04690416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. [Accessed April 5 2017];The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/. Updated 2017.

- 18.United States Department of Agriculture. [Accessed April 4 2017];Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/documentation/. Updated May 8 2017.

- 19.Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM [computer program] Rockville, MD: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch RJ, Zhang R, Patzer RE, Larsen CP, Adams AB. Waitlist Hospital Admissions Predict Resource Utilization and Survival After Renal Transplantation. Annals of surgery. 2015 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sibbel S, Sato R, Hunt A, Turenne W, Brunelli SM. The clinical and economic burden of pneumonia in patients enrolled in Medicare receiving dialysis: a retrospective, observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0412-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patzer RE, Paul S, Plantinga L, et al. A randomized trial to reduce disparities in referral for transplant evaluation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(3):935–942. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xue H, Ix JH, Wang W, et al. Hemodialysis access usage patterns in the incident dialysis year and associated catheter-related complications. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(1):123–130. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldman HI, Kobrin S, Wasserstein A. Hemodialysis vascular access morbidity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(4):523–535. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V74523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valdes-Canedo F, Pita-Fernandez S, Seijo-Bestilleiro R, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular events in renal transplant recipients and clinical relevance of modifiable variables. Transplant Proc. 2007;39(7):2239–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jardine AG, Gaston RS, Fellstrom BC, Holdaas H. Prevention of cardiovascular disease in adult recipients of kidney transplants. Lancet. 2011;378(9800):1419–1427. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61334-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitman CB, Shreay S, Gitlin M, van Oijen MG, Spiegel BM. Clinical factors and the decision to transfuse chronic dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(11):1942–1951. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00160113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanhehco YC, Berns JS. Red blood cell transfusion risks in patients with end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2012;25(5):539–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2012.01089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vranic GM, Ma JZ, Keith DS. The role of minority geographic distribution in waiting time for deceased donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(11):2526–2534. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sequist TD, Narva AS, Stiles SK, Karp SK, Cass A, Ayanian JZ. Access to renal transplantation among American Indians and Hispanics. Am J Transplant. 2004;44(2):344–352. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patzer RE, Pastan SO. Measuring the disparity gap: quality improvement to eliminate health disparities in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(2):247–248. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patzer RE, McClellan WM. Influence of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status on kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(9):533–541. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Axelrod DA, Dzebisashvili N, Schnitzler MA, et al. The interplay of socioeconomic status, distance to center, and interdonor service area travel on kidney transplant access and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(12):2276–2288. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04940610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward FL, O’Kelly P, Donohue F, et al. The influence of socioeconomic status on patient survival on chronic dialysis. Hemodial Int. 2015;19(4):601–608. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manteuffel M, Williams S, Chen W, Verbrugge RR, Pittman DG, Steinkellner A. Influence of patient sex and gender on medication use, adherence, and prescribing alignment with guidelines. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23(2):112–119. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Granger BB, Ekman I, Granger CB, et al. Adherence to medication according to sex and age in the CHARM programme. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(11):1092–1098. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villar E, Remontet L, Labeeuw M, Ecochard R. Effect of age, gender, and diabetes on excess death in end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(7):2125–2134. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006091048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.United States Renal Data System. About USRDS. https://www.usrds.org/Default.aspx. Updated 2017.