Key Points

Question

Does the addition of an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor to chemoradiation improve survival outcomes for patients with esophageal cancer?

Findings

This phase 3 randomized clinical trial compared survival for patients receiving cetuximab plus platinum, taxane, and radiation therapy to the same chemoradiation regimen alone. No significant improvement in survival was seen in patients receiving cetuximab.

Meaning

The addition of EGFR inhibition to concurrent chemoradiation therapy did not improve survival outcomes for esophageal cancer patients.

This randomized clinical trial examines the effect of the addition of EGFR inhibition to chemoradiation on survival outcomes for patients with esophageal cancer.

Abstract

Importance

The role of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibition in chemoradiation strategies in the nonoperative treatment of patients with esophageal cancer remains uncertain.

Objective

To evaluate the benefit of cetuximab added to concurrent chemoradiation therapy for patients undergoing nonoperative treatment of esophageal carcinoma.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A National Cancer Institute (NCI) sponsored, multicenter, phase 3, randomized clinical trial open to patients with biopsy-proven carcinoma of the esophagus. The study accrued 344 patients from 2008 to 2013.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to weekly concurrent cisplatin (50 mg/m2), paclitaxel (25 mg/m2), and daily radiation of 50.4 Gy/1.8 Gy fractions with or without weekly cetuximab (400 mg/m2 on day 1 then 250 mg/m2 weekly).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Overall survival (OS) was the primary endpoint, with a study designed to detect an increase in 2-year OS from 41% to 53%; 80% power and 1-sided α = .025.

Results

Between June 30, 2008, and February 8, 2013, 344 patients were enrolled. This analysis used all data received at NRG Oncology through April 12, 2015. Sixteen patients were ineligible, resulting in 328 evaluable patients, 159 in the experimental arm and 169 in the control arm. Patients were well matched between the treatment arms for patient and tumor characteristics: 263 (80%) with T3 or T4 disease, 215 (66%) N1, and 62 (19%) with celiac nodal involvement. Incidence of grade 3, 4, or 5 treatment-related adverse events at any time was 71 (46%), 35 (23%), or 6 (4%) in the experimental arm and 83 (50%), 28 (17%), or 2 (1%) in the control arm, respectively. A clinical complete response (cCR) rate of 81 (56%) was observed in the experimental arm vs 92 (58%) in the control arm (Fisher exact test, P = .66). No differences were seen in cCR between treatment arms for either histology (adenocarcinoma or squamous cell). Median follow-up for all patients was 18.6 months. The 24- and 36-month local failure for the experimental arm was 47% (95% CI, 38%-57%) and 49% (95% CI, 40%-59%) vs 49% (95% CI, 41%-58%) and 49% (95% CI, 41%-58%) for the control arm (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.66-1.28; P = .65). The 24- and 36-month OS rates for the experimental arm were 45% (95% CI, 37%-53%) and 34% (95% CI, 26%-41%) vs 44% (95% CI, 36%-51%) and 28% (95% CI, 21%-35%) for the control arm (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.70-1.16; P = .47).

Conclusions and Relevance

The addition of cetuximab to concurrent chemoradiation did not improve OS. These phase 3 trial results point to little benefit to current EGFR-targeted agents in an unselected patient population, and highlight the need for predictive biomarkers in the treatment of esophageal cancer.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00655876

Introduction

Despite recent advances in the outcomes of many solid malignant abnormalities, the treatment of patients with esophageal cancer has remained a considerable therapeutic challenge. With over 400 000 deaths annually worldwide, and often advanced disease at presentation, most of these patients are treated with nonoperative approaches.1

In 1991, the results of RTOG 8501 established the standard of care for the nonoperative treatment of esophageal cancer.2,3 The combination of cisplatin, fluorouracil, and radiotherapy led to significantly improved survival compared with radiotherapy alone. Over the past 25 years, researchers have attempted to improve on these outcomes by examining novel treatments including radiation dose escalation, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and the development of novel systemic therapies.4,5

Recent efforts have attempted to exploit biologic differences that may exist between normal and malignant cells to develop tumor-specific therapies. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) transduction network with its role in cell-cycle progression, angiogenesis, metastasis, and inhibition of tumor cell apoptosis is a prime target.6 Preclinical models suggested synergy between EGFR inhibitors, chemotherapy, and radiation.7 Clinical trial data has documented improved outcomes in patients with advanced colorectal adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck.8

With EGFR overexpression noted in more than 50% of esophageal cancers, investigators from Brown University Oncology Group and the Greenebaum Cancer Center at the University of Maryland assessed the feasibility of the addition of cetuximab with chemoradiation for locally advanced esophagogastric cancer.8 Those pilot data reported a 76% clinical complete response, a one-year overall survival rate of 70%, and a favorable toxic effects profile compared with other contemporary chemoradiation approaches.9

Phase 2 trials in locally advanced esophageal cancer have also demonstrated encouraging results of combining platinum-based agents with weekly paclitaxel.10 In contrast to 5–fluorouracil-containing regimens, the ease of administration and decreased gastrointestinal toxic effects were key advantages with platinum and paclitaxel therapy.11

Taken together, these data provided the rationale for the initiation of an intergroup phase 3 trial, RTOG 0436, led by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG), now NRG Oncology, to evaluate the addition of cetuximab to paclitaxel, cisplatin, and radiation therapy for patients with esophageal cancer who are treated without surgery.

Methods

Eligibility

Eligibility criteria included histologically confirmed squamous cell cancer (SCC) or adenocarcinoma of the esophagus or gastroesophageal (GE) junction. Workup required endoscopic evaluation and computed tomographic (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen; positron emission tomography (PET)/CT was recommended but not required. Tumor extension into the stomach was characterized using the Siewert classification.12,13 Tumors arising from the distal esophagus and involving the esophagogastric junction, or starting at the esophagogastric junction and involving the cardia (Siewert type I or II),12,13 were eligible. All registered patients had to be considered for definitive therapy without planned surgical intervention.

Eligibility also included stages T1N1M0; T2 to T4, any N, M0; and any T, any N, M1a according to the 2002 (6th edition) staging criteria of the American Joint Commission on Cancer.14 A Zubrod performance status between 0 and 2; a caloric intake of 1500 kcal/d or more; and adequate hematologic, renal, and hepatic function (defined as: absolute neutrophil count of ≥1500 cell/m3, platelets ≥100 000 cell/m3, hemoglobin of ≥8 g/dL, creatinine ≤1.5 mg/dL, bilirubin ≤1.5 times the upper limit of institutional normal [ULN], and a serum aspartate aminotransferase concentration ≤3 times the ULN) were also required. (to convert hemoglobin grams per deciliter to deciliters, multiply by 10; to convert creatinine milligrams per deciliter to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4). Patients presenting with evidence of tracheoesophageal fistula, or invasion of the primary tumor into the trachea or major bronchi, were ineligible. After institutional review board approval at each site, patient written informed consent were obtained. Consenting procedures included participation in the clinical trial, completion of the quality of life assessments, and permission to collect pathology, blood, and urine samples for future analysis. Participants were not compensated. The Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) evaluated the trial at predefined time points for accrual, toxic effects, and outcome. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 1.

Treatment Plan

Randomization was stratified by histology (adenocarcinoma vs SCC), tumor size (<5 cm vs ≥5 cm), and celiac lymph node status (present vs absent). The systemic regimen on the experimental arm included: weekly cisplatin dose at 25 mg/m2, paclitaxel at 50 mg/m2, and cetuximab with a dose of 400 mg/m2 the first week followed by a weekly dose of 250 mg/m2. The control arm had the same dose and schedule of cisplatin and paclitaxel. Radiation therapy on both arms mandated CT-based 3-dimensional treatment planning. The clinical target volume (CTV) included all gross tumor with a proximal and distal margin of 4 cm and a 1-cm radial margin, as well as the regional lymphatics. The planning target volume (PTV) margins were 1 to 2 cm beyond the CTV, and dose delivered to the entire PTV was 50.4 Gy in 28 1.8-Gy fractions. Normal tissue-dose constraints included spinal cord (50 Gy to up to 5 cm), cardiac (50 Gy to up to one-third of the heart volume), and liver (35 Gy to up to one-half of the organ volume). Lung dose constraints based on the GTV size and percent of lung receiving more than 20 Gy were also provided. Follow-up endoscopy was required for all patients 6 to 8 weeks after therapy completion. A biopsy was required to document pathologic evidence of residual disease if any suspicious areas were noted in endoscopic findings. Patients found to be clinically free of disease were not required to undergo biopsy of normal-appearing mucosa and were considered to have a clinical complete response (cCR). All patients were followed clinically every 4 months for 2 years, and then annually.

Statistical Considerations

The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS). Secondary endpoints included local failure (LF), toxic effects, cCR, quality of life (QoL), and quality-adjusted survival. The QoL endpoints will be reported separately. The OS and LF analyses were performed under intention to treat of eligible patients. Safety and cCR analyses were limited to eligible patients starting treatment. Overall survival failure was defined as death owing to any cause and measured from randomization to death or last follow-up. Local failure was defined as residual cancer on posttreatment biopsy findings or biopsy-proven recurrent primary disease and measured from randomization to failure or last follow-up. Nonprotocol surgery to the primary site with gross residual disease was considered an LF as of the surgery date. Patients with no viable disease or microscopic residual disease at nonprotocol surgery were censored for LF as of the surgery date.

Patients were stratified by the factors previously described and randomized 1:1 to the experimental and control arms using Zelen15 modified permuted block randomization. The sample size was based on the primary hypothesis of a 29% reduction in the hazard rate of death with cetuximab, corresponding to an increase in 2-year OS from 41% to 53% and a hazard ratio (λexp/λcont) of 0.71 in favor of the cetuximab arm. Assuming an exponential distribution and constant hazards, 400 patients were required to reach 281 OS events, with 80% statistical power, a 1-sided α of 0.025, 4.5 years of accrual, 2 years of follow-up, and 4 interim analyses (57, 113, 169, and 225 OS events). Allowing for a 5% or lower ineligibility rate, the final target accrual was 420 patients.

Owing to concerns regarding potential differential responses to cetuximab based on histologic analysis, the trial design included required interim analyses of cCR within histology. Assuming a control arm cCR of 40% and a 1-sided α of 0.10, 150 patients would provide 84% power to detect an absolute increase of 20%. An observed 12% increase would be sufficient to achieve this and was the criteria for continuation of accrual for a given histologic result. To address safety concerns of cetuximab combined with chemoradiation, the rate of unacceptable adverse events (AEs), (defined as grade ≥4 nonhematologic toxic effects ≤90 days from the end of therapy reported as definitely, probably, or possibly related to treatment) was analyzed for the first 25 and 50 evaluable patients in the experimental arm. All AEs were scored with National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Toxicity Criteria (version 3). A rate of 35% or higher was considered to be unacceptable. Using the Fleming method with an α of 0.05, early stopping would occur if 10 or more of the first 25 or 25 or more of the first 50 patients experienced unacceptable toxic effects,16 providing 85% power for concluding an unacceptable AE rate of 35% or higher. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc). Patient OS was estimated univariately by the Kaplan-Meier method17 and the distribution between arms compared with a stratified log-rank test, using the previously described stratification factors.18 The Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to analyze the effects of factors, in addition to treatment.19 Local failure was estimated by the cumulative incidence method20 and the distribution between arms was compared with a stratified log-rank test.18 The cCR rates between treatment arms within histologic analysis were evaluated using a Fisher exact test. The OS exploratory analyses were done comparing treatment arms for patients with and without a cCR.

Results

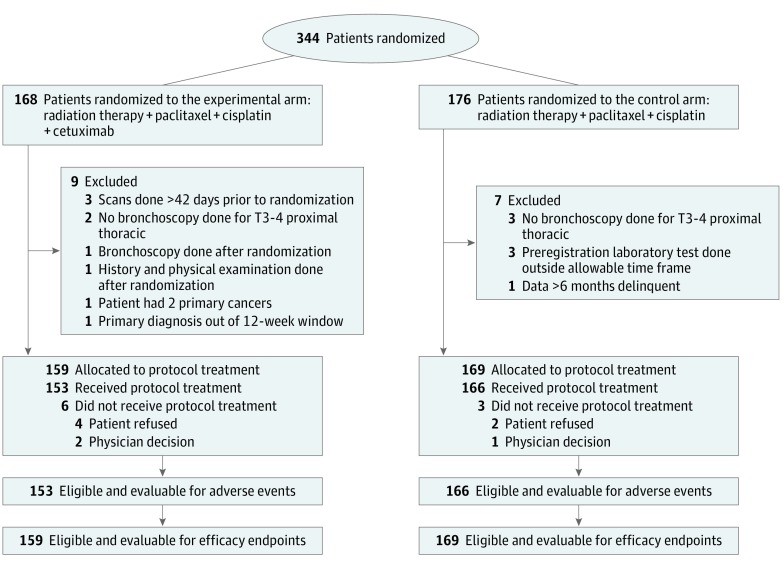

Between June 30, 2008, and February 8, 2013, 344 patients were enrolled. This analysis used all data received at NRG through April 12, 2015. Sixteen patients were ineligible (Figure 1), resulting in 328 evaluable patients, 159 in the experimental arm and 169 in the control arm. Patient demographics and tumor characteristics were evenly distributed between treatment arms (Table 1). The PET-CT staging was equally distributed between both arms. The planned interim analysis of the first 150 patients with adenocarcinoma failed to identify a significant increase in cCR; as such, adenocarcinomas were no longer enrolled after May 2012. Patients with SCC were accrued until January 2013. In January 2013, accrual was temporarily suspended when the results of the United Kingdom SCOPE 1 trial failed to document a benefit of the addition of cetuximab to chemoradiation in a similar cohort of patients.21 Although 3 OS events short, the third planned primary endpoint interim analysis of the RTOG 0436 trial was performed. Based on all available data, the RTOG DMC recommended that 0436 stop further accrual. Following discussions with the NCI, the study permanently closed on February 8, 2013. Follow-up was continued to report the outcomes for the patients who had been enrolled.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Table 1. Patient and Tumor Characteristics for All Eligible Patients.

| Patient or Tumor Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| RT + Chemo + Cetuximab (n = 159) | RT + Chemo (n = 169) | Total (n = 328) | |

| Age, median (range) [Q1-Q3] | 65 (39-87) [57-72] | 63 (32-85) [57-70] | 64 (32-87) [57-71] |

| ≤49 | 8 (5.0) | 10 (5.9) | 18 (5.5) |

| 50-59 | 41 (25.8) | 52 (30.8) | 93 (28.4) |

| 60-69 | 55 (34.6) | 64 (37.9) | 119 (36.3) |

| 70-79 | 48 (30.2) | 35 (20.7) | 83 (25.3) |

| ≥80 | 7 (4.4) | 8 (4.7) | 15 (4.6) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 130 (81.8) | 146 (86.4) | 276 (84.1) |

| Female | 29 (18.2) | 23 (13.6) | 52 (15.9) |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.2) | 5 (1.5) |

| Asian | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.2) | 4 (1.2) |

| Black or African American | 19 (11.9) | 22 (13.0) | 41 (12.5) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| White | 130 (81.8) | 140 (82.8) | 270 (82.3) |

| More than 1 race | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Unknown | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.8) | 6 (1.8) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 5 (3.1) | 9 (5.3) | 14 (4.3) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 145 (91.2) | 153 (90.5) | 298 (90.9) |

| Unknown | 9 (5.7) | 7 (4.1) | 16 (4.9) |

| Zubrod performance status | |||

| 0 | 70 (44.0) | 88 (52.1) | 158 (48.2) |

| 1 | 80 (50.3) | 70 (41.4) | 150 (45.7) |

| 2 | 9 (5.7) | 11 (6.5) | 20 (6.1) |

| T stage (clinical) | |||

| T1 | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.4) | 7 (2.1) |

| T2 | 27 (17.0) | 31 (18.3) | 58 (17.7) |

| T3 | 121 (76.1) | 124 (73.4) | 245 (74.7) |

| T4 | 8 (5.0) | 10 (5.9) | 18 (5.5) |

| N stage (clinical) | |||

| N0 | 54 (34.0) | 59 (34.9) | 113 (34.5) |

| N1 | 105 (66.0) | 110 (65.1) | 215 (65.5) |

| M stage (clinical) | |||

| M0 | 134 (84.3) | 147 (87.0) | 281 (85.7) |

| M1a | 25 (15.7) | 22 (13.0) | 47 (14.3) |

| Cancer lesion size, cma | |||

| <5 | 71 (44.7) | 77 (45.6) | 148 (45.1) |

| ≥5 | 88 (55.3) | 92 (54.4) | 180 (54.9) |

| Histologic findingsa | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 100 (62.9) | 103 (60.9) | 203 (61.9) |

| Squamous cell | 59 (37.1) | 66 (39.1) | 125 (38.1) |

| Celiac nodes statusa | |||

| Present | 28 (17.6) | 34 (20.1) | 62 (18.9) |

| Absent | 131 (82.4) | 135 (79.9) | 266 (81.1) |

Abbreviations: Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; RT, radiation therapy.

Stratification factor.

Treatment Tolerance and Toxic Effects

Early stopping rules were not met at the predefined interim toxic effects analyses. At final analysis, treatment-related nonhematologic grade 4 or higher adverse events (AEs) occurring 90 days or less from the end of therapy were 15.7% (24 of 153; 95% CI, 10.8%-22.3%) for the cetuximab arm, well below the 35% threshold for early study closure. Treatment-related grade 3 or higher AEs are reported in Table 2. The grade 3 or higher hematologic toxic effects were 45% in the experimental and 44% in the control arm. The incidence of grade 1, 2, and 3 acniform rash was 26%, 29%, and 6%, respectively, for patients receiving cetuximab, vs 1% grade 1 for those not. Grade 3 or higher gastrointestinal toxic effects were 44% vs 36%. There were 6 (4%) patients on the cetuximab arm that experienced grade 5 toxic effects possibly attributed to protocol therapy; 2 cardiac-related deaths, 1 renal failure, 1 fatal pulmonary complication, 1 esophageal perforation, and 1 death not otherwise specified [NOS]—failure to thrive. Two (1%) patients experienced grade 5 toxic effects in the control arm, possibly attributed to protocol treatment, 1 sudden death NOS, and 1 other death from infection.

Table 2. Number of Patients With a Grade 3 or Higher Adverse Event by Category, Term, and Grade—Definitely, Probably, or Possibly Related to Protocol Treatmenta.

| Category (Term) | RT + Chemo + Cetuximab (n = 153) | RT + Chemo (n = 166) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Grade | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Overall highest grade, No. (%) | 71 (46) | 35 (23) | 6 (4) | 83 (50) | 28 (17) | 2 (1) |

| Allergy/immunology | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Hypersensitivity | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Blood/bone marrow | 45 | 24 | 0 | 52 | 21 | 0 |

| Hemoglobin decreased | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 36 | 8 | 0 | 35 | 6 | 0 |

| Lymphopenia | 8 | 14 | 0 | 13 | 16 | 0 |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 22 | 8 | 0 | 21 | 3 | 0 |

| Cardiac general | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiac disorder | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Myocardial ischemia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constitutional symptoms | 24 | 3 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 20 | 2 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Fever | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Weight loss | 8 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sudden death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Dermatologic/skin | 16 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Acne | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | 63 | 5 | 0 | 58 | 2 | 0 |

| Acquired tracheoesophageal fistula | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Anorexia | 14 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 0 |

| Colitis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dehydration | 34 | 1 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 11 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 18 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Enteritis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Esophagitis | 17 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 19 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 12 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Hemorrhage/bleeding | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Esophageal hemorrhage | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatobiliary/pancreas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cholecystitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Infection | 16 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Infection [other] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pneumonia (with normal or grade 1-2 ANC) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sepsis | ||||||

| With normal or grade 1 to 2 ANC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| With unknown ANC | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Metabolic/laboratory findings | 24 | 9 | 0 | 27 | 2 | 0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Alkaline phosphatase increased | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Hypernatremia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 8 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypocalcemia | 7 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 5 | 5 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypomagnesemia | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 13 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal/soft tissue | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Muscle weakness | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Neurologic | 5 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain | 11 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 2 | 0 |

| Chest wall pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Esophageal pain | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain (other) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Pulmonary/upper respiratory | 6 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Adult respiratory distress syndrome | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumonitis | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Respiratory disorder | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Renal/genitourinary | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Renal failure | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Vascular | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Vascular access complication | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; chemo, chemotherapy; RT, radiation therapy.

Adverse events were graded with CTCAE version 3.0. All grade 4 and 5 AEs are shown and only grade 3 AEs are shown if 5% or higher in either arm.

It is important to note that more grade 5 AEs were reported to be possibly attributed to protocol treatment with cetuximab (6 vs 2). Three of these 6 events were noted early in the accrual period, and involved patients older than 75 years. An interim toxicity analysis revealed an increased toxic effects profile for patients ages 75 years or older regardless of treatment arm. As a result, the DMC and the NCI approved an amendment to limit eligibility to patients younger than 75 years, which was implemented in July 2011, and after which there were no differences in grade 5 treatment-related toxic effects between arms.

eTables 1A and B in Supplement 2 summarize the findings of the modality-specific treatment reviews. Notably, 138 (87%) of 159 patients in the experimental arm and 148 (88%) of 169 in the control arm had radiation tumor volume contours scored acceptable according to protocol. One hundred nine (69%) patients treated in the experimental arm and 127 (75%) in the control arm received chemotherapy per protocol, with dose modifications in 87 (55%) and 85 (50%), respectively.

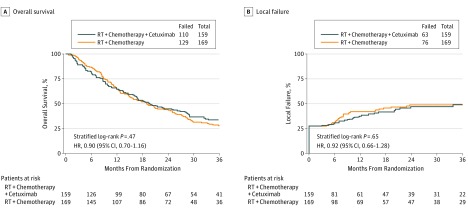

Survival

With a median follow-up of 18.6 months (range, 0.1-74.5 months) for all 328 patients, and 42.7 months for 89 surviving patients, there was no statistically significant difference in OS between the treatment groups (stratified log-rank P = .47; HR [λexp/λcont], 0.90; 95% CI, 0.70-1.16) (Figure 2A). The estimated 24- and 36-month OS for the experimental arm was 44.9% (95% CI, 36.9%-52.5%) and 33.8% (95% CI, 26.4%-41.4%), respectively. The 24- and 36-month OS for patients treated on the control arm was 44.0% (95% CI, 36.4%-51.4%) and 27.9% (95% CI, 21.2%-35.0%), respectively. With 328 of the 400 planned evaluable patients, and specifically only 239 of the required 281 OS events, the power to detect the hypothesized increase in OS was reduced from 80% to approximately 74%. The proportional hazards assumption was met.

Figure 2. Overall Survival and Local Failure by Treatment Arm.

A, Overall survival by treatment arm (n = 328). B, Local failure by treatment arm (n = 328).

Table 3 presents the OS multivariable analysis. Zubrod performance status of 0, T1 and/or T2 primary tumors, and tumors smaller than 5 cm were all associated with improved OS. Notably, histologic analysis results did not impact OS because patients with adenocarcinoma had a median OS of 19.7 months (2-year OS, 43.4%; 95% CI, 36.4%-50.2%) vs 19.0 months (2-year OS, 46.2%; 95% CI, 37.2%-54.7%) for those with SCC (log-rank, P = .23). Forty-four patients had surgery for residual (n=26) or recurrent disease (n = 18) (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Table 3. Overall Survival in 328 Patients: Multivariate Cox Proportional Analysisa.

| Adjustment Variables | Comparison | Adjusted HR (95% CI)b | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm | RT + chemotherapy vs RT + chemotherapy + cetuximab | 0.84 (0.65-1.09) | .18 |

| Zubrod performance status | 0 vs 1/2 | 1.48 (1.14-1.91) | .003 |

| T stage | T1/T2 vs T3/T4 | 1.55 (1.07-2.26) | .02 |

| Cancer lesion size | <5 cm vs ≥5 cm | 1.50 (1.15-1.97) | .003 |

| Histology | Squamous cell vs adenocarcinoma | 1.15 (0.88-1.51) | .30 |

| Celiac nodes | Absent vs present | 0.95 (0.68-1.31) | .74 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; RT, radiation therapy.

The model was built after adjusting for treatment arm, histologic findings, celiac nodes, and cancer lesion size.

Hazard Ratio: a hazard ratio of 1 indicates no difference between the 2 subgroups. The variables were coded such that a HR greater than 1 indicates an increased risk of death for the second level of the variables listed.

P value from χ2 test using the Cox proportional hazards model.

Response Assessment

Regardless of findings of histologic analysis, the posttherapy endoscopic assessment failed to identify a difference in the cCR rate based on the treatment delivered (56.3% for the experimental vs 57.9% for the control arm; Fisher exact test, P = .66). The protocol-specified interim cCR analysis of the first 150 evaluable patients with adenocarcinoma failed to reveal a significant increase with cetuximab, with a cCR of 52.7% for those treated in the experimental arm vs 53.9% for controls (Fisher exact test, P = .62). Similarly, patients with SCC receiving cetuximab had a cCR rate of 59.3% vs 64.4% receiving control therapy (Fisher exact test, P = .78).

Patients who achieved a cCR after therapy had improved OS compared with those with residual disease (log-rank P < .001; HR (λcCR/λres), 0.46; 95% CI, 0.35-0.60) (eFigure in Supplement 2). The estimated 24- and 36-month OS with cCR was 59.9% (95% CI, 52.2%-66.8%) and 43.3% (95% CI, 35.6%-50.6%), respectively, compared with 30.0% (95% CI, 22.2%-38.1%) and 18.1% (95% CI, 11.8%-25.4%), respectively, for those with residual disease.

Local Failure

The 24- and 36-month LF for patients treated on the experimental arm was 47.0% (95% CI, 38.3%-56.6%) and 49.1% (95% CI, 39.9%-59.2%), respectively, and for controls, was 48.8% (95% CI, 40.8%-57.5%) and 48.8% (95% CI, 40.8%-57.5%), respectively (stratified log-rank P = .65; HR(λexp/λcont), 0.92; 95% CI, 0.66-1.28) (Figure2B). There were 47 patients deemed clinically to have residual disease but who did not undergo biopsy based on treating physician discretion. These patients were more likely to have worse performance status, more advanced tumors, and regional nodal involvement.

Discussion

The NRG RTOG 0436 trial failed to demonstrate a survival improvement for patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer treated with concurrent weekly cisplatin, paclitaxel, and daily radiation plus cetuximab compared with those treated with concurrent chemoradiation alone. The median and 2-year OS of 19.7 months and 45% associated with cetuximab was similar to the 19 months and 44% achieved on the control arm. The results also failed to identify any improvement in cCR or LF associated with the addition of cetuximab.

The decision to terminate accrual early was driven by the concurrent publication of the United Kingdom SCOPE 1 phase 2/3 trial. SCOPE 1 investigated the addition of cetuximab to a cisplatin and flouropyrimidine-based chemoradiation treatment scheme.21 The experimental regimen included 2 cycles of induction systemic therapy followed by concurrent chemoradiation with or without cetuximab. Recruitment was halted after a planned interim analysis revealed that futility criteria had been reached during the phase 2 study phase. The percentage of patients failure free at 24 weeks was worse for the cetuximab arm (66% vs 77%), and the addition of cetuximab was associated with an inferior OS (22 months vs 25.4 months; HR, 1.53; P = .03).

An important difference between this study and the RTOG 0436 trial was the use of induction chemotherapy on SCOPE 1. The authors noted that patients who received cetuximab were twice as likely to have discontinued therapy without receiving any of the planned radiation (19% vs 8%), and as a result, cautioned against intensified treatment strategies that risk delivery of proven treatment approaches. Given the OS decrease associated with the addition of cetuximab, it was suggested that the combination of EGFR inhibition and chemoradiation had an inhibitory antitumor effect. The REAL 3 study similarly revealed an OS decline and decrease in delivered systemic therapy associated with the addition of panitumumab in patients with esophagogastric malignant abnormalities.22 While the RTOG 0436 trial failed to document an OS improvement associated with cetuximab and chemoradiation, it did not show any evidence of reduced efficacy compared with standard therapy.

The toxic effects profile of both arms of the RTOG 0436 trial does provide support for a weekly systemic therapy regimen that uses a platinum with taxane combination rather than fluorouracil. These results add to the growing body of literature that supports the use of this chemotherapy combination. The use of a platinum/taxane in combination with radiation continues to gain acceptance based on its favorable toxic effects profile, ease of administration, and efficacy results. A similar regimen was used in the CROSS trial in the neoadjuvant setting for both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell histologies.10

While the debate over the role of surgery in this patient population continues, it is important to note that this trial was specifically designed to test the addition of cetuximab in the nonoperative setting. Given that consensus does not exist regarding the use of tri-modality therapy, this study included patients who were deemed to be medically unfit for surgery as well as those whose treating physicians supported a nonoperative approach. This is highlighted by the fact that 44 (13%) of 328 patients ultimately did undergo resection for residual and/or recurrent disease.

The results of the NRG Oncology RTOG 0436 trial are consistent with other phase 3 studies that have failed to demonstrate OS improvements with the addition of EGFR inhibition to concurrent chemoradiation regimens for various solid tumors.23 Taken together, these trial results highlight the need to identify prognostic variables that may provide insight into which patient populations will benefit from EGFR inhibition. Esophageal tumors with mutation of the p53 gene have been associated with a decrease in response to chemotherapy and radiation, and inferior OS.24 The mutation of the membrane protein KRAS has been suggested as a key determinant of responsiveness to EGFR inhibition.25,26 As such, the prospective collection of tissue and blood specimens was purposely considered in the trial design.

Limitations

Patients were included regardless of EGFR expression. Further research may be warranted to identify prognostic variables that may provide insight into potential populations with esophageal disease that could benefit from an EGFR inhibitor. Owing to the number of events that had occurred at the time of reporting the results, statistical power for the hypothesized improvement in OS was reduced from the designed 80% to 74%. However, the stopping of accrual and early reporting was recommended by the oversight DMC, based on futile results from another phase 3 clinical trial and evaluation of the RTOG 0436 third planned interim analysis of OS.

Conclusions

The addition of EGFR inhibition to concurrent chemoradiation failed to improve the OS for locally advanced esophageal cancer treated nonoperatively. The continued effort to identify populations of patients with molecular overexpression of potential targets will ultimately improve the ability to refine the treatment approach in this challenging disease.

Trial protocol

eTable 1a. Radiation Therapy Planning Review

eTable 1b. Chemotherapy/Targeted Agent Review

eTable 2. Reported Surgery in Follow-up for All Patients

eFigure. Overall Survival by Clinical Disease Status (n=303)

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper JS, Guo MD, Herskovic A, et al. ; Radiation Therapy Oncology Group . Chemoradiotherapy of locally advanced esophageal cancer: long-term follow-up of a prospective randomized trial (RTOG 85-01). JAMA. 1999;281(17):1623-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herskovic A, Martz K, al-Sarraf M, et al. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in patients with cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(24):1593-1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelsen DP, Winter KA, Gunderson LL, et al. ; Radiation Therapy Oncology Group; USA Intergroup . Long-term results of RTOG trial 8911 (USA Intergroup 113): a random assignment trial comparison of chemotherapy followed by surgery compared with surgery alone for esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3719-3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minsky BD, Neuberg D, Kelsen DP, et al. Final report of Intergroup Trial 0122 (ECOG PE-289, RTOG 90-12): Phase II trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus concurrent chemotherapy and high-dose radiation for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43(3):517-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang SM, Bock JM, Harari PM. Epidermal growth factor receptor blockade with C225 modulates proliferation, apoptosis, and radiosensitivity in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 1999;59(8):1935-1940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harari PM, Huang SM. Epidermal growth factor receptor modulation of radiation response: preclinical and clinical development. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2002;12(3)(suppl 2):21-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: 5-year survival data from a phase 3 randomised trial, and relation between cetuximab-induced rash and survival. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(1):21-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safran H, Suntharalingam M, Dipetrillo T, et al. Cetuximab with concurrent chemoradiation for esophagogastric cancer: assessment of toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70(2):391-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. ; CROSS Group . Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(22):2074-2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honing J, Smit JK, Muijs CT, et al. A comparison of carboplatin and paclitaxel with cisplatinum and 5-fluorouracil in definitive chemoradiation in esophageal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(3):638-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis NJ, Noble F, Bailey IS, Kelly JJ, Byrne JP, Underwood TJ. The relevance of the Siewert classification in the era of multimodal therapy for adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109(3):202-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szántó I, Vörös A, Gonda G, et al. [Siewert-Stein classification of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction]. Magy Seb. 2001;54(3):144-149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene FL; American Joint Committee on Cancer . American Cancer Society. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th ed New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zelen M. The randomization and stratification of patients to clinical trials. J Chronic Dis. 1974;27(7-8):365-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming TR. One-sample multiple testing procedure for phase II clinical trials. Biometrics. 1982;38(1):143-151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(282):457-481. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50(3):163-170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox D. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34(2):187-220. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalbfleisch J, Prentice R. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York: John Wiley & Sons. KalbfleischThe Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crosby T, Hurt CN, Falk S, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with or without cetuximab in patients with oesophageal cancer (SCOPE1): a multicentre, phase 2/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):627-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waddell T, Chau I, Cunningham D, et al. Epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine with or without panitumumab for patients with previously untreated advanced oesophagogastric cancer (REAL3): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):481-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ang KK, Zhang Q, Rosenthal DI, et al. Randomized phase III trial of concurrent accelerated radiation plus cisplatin with or without cetuximab for stage III to IV head and neck carcinoma: RTOG 0522. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):2940-2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimada H, Shiratori T, Takeda A, et al. Perioperative changes of serum p53 antibody titer is a predictor for survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Surg. 2009;33(2):272-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lièvre A, Bachet JB, Boige V, et al. KRAS mutations as an independent prognostic factor in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(3):374-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lièvre A, Bachet JB, Le Corre D, et al. KRAS mutation status is predictive of response to cetuximab therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):3992-3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

eTable 1a. Radiation Therapy Planning Review

eTable 1b. Chemotherapy/Targeted Agent Review

eTable 2. Reported Surgery in Follow-up for All Patients

eFigure. Overall Survival by Clinical Disease Status (n=303)