Abstract

Identifying modifiable correlates of good quality of life (QoL) in adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is of paramount importance for intervention development as the population of adults with ASD increases. This study sought to examine social support and perceived stress as potential modifiable correlates of QoL in adults with ASD. We hypothesized that adults with ASD without co-occurring intellectual disabilities (N=40; ages 18–44) would report lower levels of social support and QoL than typical community volunteers who were matched for age, sex, and race (N=25). We additionally hypothesized that social support would buffer the effect of perceived stress on QoL in adults with ASD. Results indicated that adults with ASD reported significantly lower levels of social support and QoL than matched typical community volunteers. In addition, findings showed significant direct effects of social support and perceived stress on QoL in adults with ASD. Social support did not buffer the effect of perceived stress on QoL. Interventions that teach adults with ASD skills to help them better manage stress and cultivate supportive social relationships have the potential to improve QoL.

Keywords: ASD, Asperger’s, high-functioning autism, intervention, friendship, social inclusion, quality of life, stress

Introduction

A large wave of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the early part of the century is currently on the precipice of adulthood (Newschaffer et al., 2005), but we know little about how to promote optimal functioning and quality of life (QoL) for individuals with ASD throughout the life course (Gerhardt and Lainer, 2011). Research to date has sufficiently and broadly characterized outcomes for adults with ASD as relatively poor in that most adults with ASD experience lifelong challenges with living independently, finding and sustaining employment, and establishing friendships and romantic relationships (for reviews, see: Levy and Perry, 2011; Magiati et al., 2014; Steinhausen et al., 2016). In addition, many individuals with ASD have poor objective and subjective QoL and well-being in adulthood (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2016; Helles et al., in press; Hong et al., 2016). While research is emerging on factors that are either longitudinally or cross-sectionally associated with better outcomes and functioning (Levy and Perry, 2011; Magiati et al., 2014; Steinhausen et al., 2016), we still lack a clear picture of modifiable factors that may promote positive outcomes and QoL in adulthood for individuals with ASD. Moreover, identification of modifiable correlates of positive outcomes and QoL will enable testing of longitudinal models or targeted treatment that could provide clear evidence for a causal pathway (Hill, 1965). As such, continued investigation of modifiable correlates of outcomes and QoL in adults with ASD is needed.

A growing body of evidence replicated in three separate samples indicates that high perceived stress, which refers to the degree to which individuals appraise situations in their life as stressful (Cohen and Janicki-Deverts, 2012), is associated with poorer social functioning and QoL in adults with ASD both with and without co-occurring intellectual disabilities. These studies found that, in adults with ASD, higher perceived stress was associated with greater autism symptom severity (Hirvikoski and Blomqvist, 2015), greater social disability (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2015; Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2017), and lesser QoL (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., in press; Hong et al., 2016). Notably, all associations were medium to large (Cohen, 1988), with correlation coefficients and standardized betas ranging from 0.39–0.59, and all three studies used the Perceived Stress Scale to measure perceived stress (Cohen and Williamson, 1988). As such, although causal ordering remains unclear because of a lack of longitudinal data in all three datasets, high perceived stress may impede optimal QoL and for adults with ASD. Yet, we know little about factors that may help adults with ASD better manage stress, and in turn, improve QoL.

Historically, a large body of research has identified high social support as a factor that may protect against the deleterious effects of high perceived stress on poorer health and well-being. This body of literature focused on the general population of individuals without developmental disabilities indicates that social support may ameliorate, or buffer, the potential detrimental effects of high perceived stress on poorer overall health and well-being (Cohen and McKay, 1984; Cassel, 1976; Cobb, 1976). This “stress buffering hypothesis” suggests that social support moderates the effect of perceived stress on a number of indicators of health and well-being (Cohen and McKay, 1984). This hypothesis is supported by large epidemiological studies conducted in the 1970s and 1980s in both the United States and Scandinavia that identify reductions in medical risk factors and risk of mortality (e.g., high blood pressure, high cholesterol) of as much as 50% among those individuals with high levels of social support (for review, see: Ditzen and Heinrichs, 2014). Indeed, findings from a recent meta-analysis suggest that the impact of increased social support on health and well-being may be larger than that of other health-promoting factors such as increasing physical activity or reducing smoking and alcohol consumption (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). Importantly, it is possible that better health and well-being make it possible to maintain more positive social supports suggesting a potential bidirectional relationship (Ditzen and Heinrichs, 2014). Interventions tested in the general population suggest that increasing social support can improve health and increase well-being (Kirby et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2010).

Although a direct effect of social support on health and well-being is relatively consistently found in the literature, social support may not be enough to overcome the negative impact of significant stress on QoL. For example, research suggests that individuals with very high levels of distress and neuroticism may not experience the same stress buffering benefits of social support as those with more moderately elevated symptoms, while they may still experience a direct effect of social support on health and well-being (Landerman et al., 1989; Park et al., 2013). Similarly, for adults with schizophrenia, who often have limited interactions with others and share many social communicative and neurocognitive similarities with adults ASD without co-occurring intellectual disabilities (Eack et al., 2013a), social support may have a direct effect rather than an indirect effect on health and well-being (Buchanan, 1995). Thus, it may be that social support is beneficial in its own right for adults with high distress or limited social engagement even though it does not buffer the impact of high perceived stress on poorer health and well-being.

Social support may be a pertinent correlate of QoL for adults with ASD. Individuals with ASD experience marked impairments in social communication and social cognition that are diagnostic of ASD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Because of these challenges with social communication and social cognition, it may be more difficult for individuals with ASD to establish supportive social relationships than it is for the general population, and these social interactions may be stressful (First et al., in press; Hirvikoski and Blomqvist, 2015). However, it is important to note that individuals with ASD are likely to still derive benefit from social support even if some social situations are more stressful. Unfortunately, there is some evidence that indicates that social support may be limited in individuals with ASD. For example, individuals with ASD report less social inclusion (Symes and Humphrey, 2010; Howlin et al., 2013), and lower levels of social support (Humphrey and Symes, 2010) than their peers without ASD. In addition, lower levels of social inclusion and support are likely associated with poorer outcomes and functioning in adulthood. For instance, Renty and Roeyers (2006) found that adults with ASD who had lower levels of perceived social support also had lower levels of overall QoL. A recent study additionally found that greater loneliness is associated with decreased life satisfaction and self-esteem in adults with ASD (Mazurek, 2014). However, while it appears as though perceived stress is similarly associated with QoL in adults with ASD as in the general population (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2015; Hirvikoski and Blomqvist, 2015; Hong et al., 2016), it remains unclear whether social support has similar beneficial effects for stress management for adults with ASD.

This study aimed to characterize group differences between adults with ASD and typical community volunteers in social support and QoL. Additionally, we aimed to explore both a direct effect of perceived stress on QoL and a potential stress buffering, or moderating, effect of social support on the relationship between perceived stress and QoL in adults with ASD and typical community volunteers. Based on these aims, we hypothesized that adults with ASD would have lower levels of social support and lower levels of QoL than typical community volunteers. We also hypothesized that there would be a significant, negative association of perceived stress on QoL for both adults with ASD and typical community volunteers. Finally, we hypothesized that social support would moderate the association between perceived stress and QoL such that the effect of higher levels of perceived stress on lower levels of QoL would be lessened for individuals with higher levels of social support.

Method

Participants

We recruited 40 participants with ASD from an active comparative effectiveness study of two psychosocial treatments, Cognitive Enhancement Therapy (CET) and Enriched Supportive Therapy (EST), for adults with ASD (Eack et al., 2013b). Both CET and EST involve an emotion management component in either an individual or group counseling context. These interventions are hypothesized to affect stress and social support in some way, but it is not expected that either of these treatments alone will normalize stress or social support in this population because neither treatment is designed to directly target stress or social support.

All participants with ASD who were enrolled in this clinical trial were sent letters with information about the current study, and the first forty who responded to the letter and who met eligibility criteria were enrolled. Eligibility criteria included meeting expert clinical opinion and research criteria for ASD based on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (Lord et al., 2000) or Autism Diagnostic Interview-R (Lord et al., 1994), age 18–55, and an IQ > 80 as assessed by the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; Wechsler, 2008). Participants were recruited for this clinical trial from local ASD clinics, universities, self-advocate groups, parent advocate groups, and special interest groups (e.g., anime club).

We recruited an additional cohort of 25 typical community volunteers matched to the ASD group for age, biological sex, and race. These participants had no current psychiatric disability, as confirmed through the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (First et al., 2002) and had no history of cardiovascular disease or other major medical disorders. These participants were recruited through a database of participants who had served as typical community volunteers in previous autism and schizophrenia studies.

Demographic characteristics of participants with ASD and typical community volunteers are presented in Table 1. Most participants were male, of European American descent, and in their mid-twenties. Although the average full-scale IQ of the sample of adults with ASD was above average (M = 106.53, S.D. = 15.33), fewer than half were employed (n = 19), fewer than one quarter had completed college (n = 9), and fewer than one fifth (n = 7) were living independently. In addition, all of the participants who were employed were working in jobs that were not commensurate with their education and intellectual ability. Adults with ASD and typical community volunteers did not differ significantly with regard to sex, race, age, or IQ, suggesting that group matching was successful. As expected, adults with ASD and typical community volunteers did differ significantly in terms of employment, education, and independent living.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

| Variable | ASD | Control | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| (N = 40) | (N = 25) | ||

| Age, M (SD) | 24.20 (6.95) | 24.84 (3.69) | .673 |

| Full-scale IQb, M (SD) | 106.53 (15.33) | 110.60 (14.67) | .293 |

| Male, N (%) | 90.00 (36) | 84.00 (21) | .743 |

| European American, N (%) | 82.50 (33) | 68.00 (17) | .295 |

| Employedc, N (%) | 47.50 (19) | 84.00 (21) | .007 |

| College Graduate, N (%) | 22.50 (9) | 60.00 (15) | <.001 |

| Lives Independentlyd, N (%) | 17.5 (7) | 88.00 (22) | .005 |

Note. ASD = autism spectrum disorder, M = mean, SD = standard deviation, N = number, IQ = intelligence quotient

Fisher’s exact test or independent t-test, two-tailed, for significant differences between adults with ASD or typical community volunteers.

Based on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised

Based on any paid employment

Lives either alone or with non-relatives

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

This study was approved as a separate study from the larger intervention study by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, and all data and information collected were treated confidentially and complied with the policies and procedures governing research set forth by the University. All participants completed informed consent procedures prior to testing.

Measures

Independent Variable: Perceived Stress

Perceived stress was measured with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983) which consists of 10 items that are rated on a 5-point Likert scale where higher scores are indicative of greater perceived stress (possible range = 0–40). Questions include items such as: “In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly?”; “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and ‘stressed’?”; “In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?”; and “In the last month, how often have you been angered because of things that were outside of your control?” Cronbach’s alpha reliability ranges from .78 to .91 in numerous national surveys in the typically developing population (Cohen and Janicki-Deverts, 2012; Cohen and Williamson, 1988), and other research has found strong reliability in a mixed-IQ group adults with ASD (α = .76; Hong et al., 2016). Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was .87 for participants with ASD and .89 for typical community volunteers.

Moderator Variable: Social Support

Perceived social support was measured using the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (Cohen et al., 1985), a 40-item, self-report inventory. Items are rated on a 4-point scale where higher scores are indicative of more perceived social support (possible range = 0–120). Items are counterbalanced for social desirability in that half are negative statements and half are positive statements. Negative statements are reverse coded for analyses. Questions assess the degree to which participants believe that others would offer social support when they are facing adversity and include items such as: “When I feel lonely, there are several people I can talk to”; “There are several different people I enjoy spending time with”; “If I were sick, I could easily find someone to help me with daily chores”; and “There is someone who takes pride in my accomplishments.” Internal consistency of the ISEL in the general population of people without disabilities ranges from .88 to .90 (Cohen et al., 1985). Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was .94 for participants with ASD and .96 for typical community volunteers.

Dependent Variable: QoL

Quality of life was measured using the brief version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (Skevington et al., 2004), the WHOQOL-BREF, which is psychometrically similar to and correlates highly with domain scores on the longer version of the instrument (Skevington et al., 2004; WHOQOL Group, 1998). The WHOQOL-BREF contains 26 items which are measured on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating better QoL (possible range = 0–100). Items include questions that assess QoL in the domains of physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment such as: “Do you have enough energy for everyday life?”; “How often do you have negative feelings such as blue mood, despair, anxiety, or depression?”; “How satisfied are you with your ability to perform your daily living activities?”; and “Do you have enough money to meet your needs?” This study used a total sum score of QoL, which was a mean of scores across the four domains of the WHOQOL-BREF. Previous research confirms strong internal consistency (α = .71 to .82) in adults with ASD and also finds that adults with ASD are able to accurately report their own subjective QoL on the WHOQOL-BREF in that their ratings are comparable to ratings by their mothers (Hong et al., 2016). Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was .84 for participants with ASD and .88 for typical community volunteers.

Covariates

Age was recorded on the day of data collection based on participant report.

Full-scale intelligence quotient (IQ) was determined using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 2008).

Sex was recorded on the day of data collection based on participant report.

Treatment exposure was broken down by the intervention time point as 0 (baseline), 9 months, 18 months, and 30 months (18 months of treatment plus 12 months of follow-up) of treatment and was recorded because all individuals with ASD enrolled in this study were also participants in an intervention trial. Treatment exposure was used as a covariate to account for any impact treatment had on the primary study variables.

Analyses

Preliminary analyses ensured that parametric tests were appropriate. Missing data were imputed using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm, which results in less biased parameter estimates than mean or regression imputation (Honaker et al., 2011; Schafer and Graham, 2002). Preliminary analyses also included the calculation of zero-order Pearson’s correlation coefficients to determine bivariate relationships between variables of interest.

The relationship between perceived stress and QoL was examined using hierarchical multiple linear regression predicting QoL from perceived stress, using separate models for adults with ASD and typical community volunteers. Demographic characteristics were entered into the model in the first step in order to account for their impact on QoL, and then perceived stress and social support were entered into the model in the second step to test for direct effects. Next, in order to test the moderating effects of social support on the relationship between perceived stress and QoL, a perceived stress x social support interaction term was entered in the third step of the regression model. Perceived stress and social support were centered for the purpose of the interaction analysis in order to reduce the risk of multicollinearity (Marquardt, 1980). All analyses were conducted using R version 3.2.0 (R Core Team, 2015).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Analyses ensured that measures met assumptions for parametric testing. Age was positively skewed (skewness statistic = 1.31), and was thus transformed using winsorization procedures for two data points (both individuals with ASD) at the top of the distribution. Missing data were imputed using the EM algorithm for the WHOQOL-BREF (10.0% missing), which were missing because the WHOQOL-BREF was not collected for four adults with ASD who participated in an early pilot of the CET intervention.

Group Differences in Perceived Stress, Social Support, and QoL

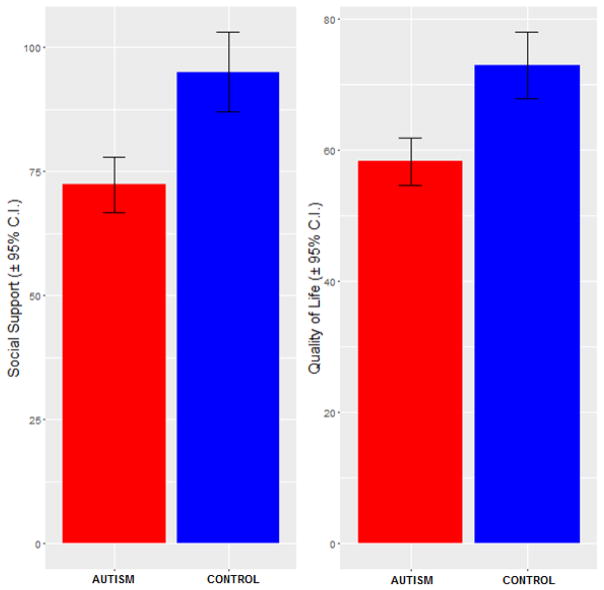

Adults with ASD reported significantly lower levels of social support, F(1, 63) = 23.95, p < .001, and significantly lower levels of QoL, F(1, 63) = 24.41, p < .001, than typical community volunteers. Mean scores, and their corresponding standard deviations, as well as Cohen’s d effect size of the magnitude of between-group differences, are presented in Table 2, and results are graphically displayed in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Results of One-Way Analysis of Variance for Variables of Interest by Group

| Variable | ASD | Control | Possible Range | F | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Mean | S.E. | Mean | S.E. | ||||

| Social Support | 72.35 | 2.88 | 95.04 | 3.63 | 0–120 | 23.95*** | 1.25 |

| Quality of Life | 58.26 | 1.84 | 72.88 | 2.32 | 0–100 | 24.41*** | 1.26 |

Note. ASD = autism spectrum disorder. Possible range refers to the full range of possible scores on the measure, not the range of scores for participants in this study.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Figure 1.

Group Differences between Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Typical Community Volunteers on Social Support and Quality of Life

Prediction of QoL based on Perceived Stress and Social Support

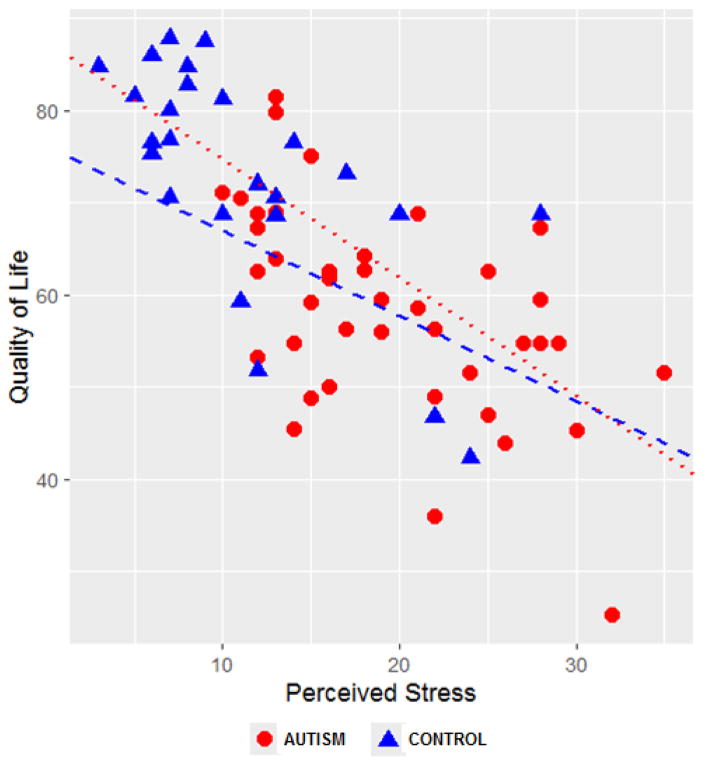

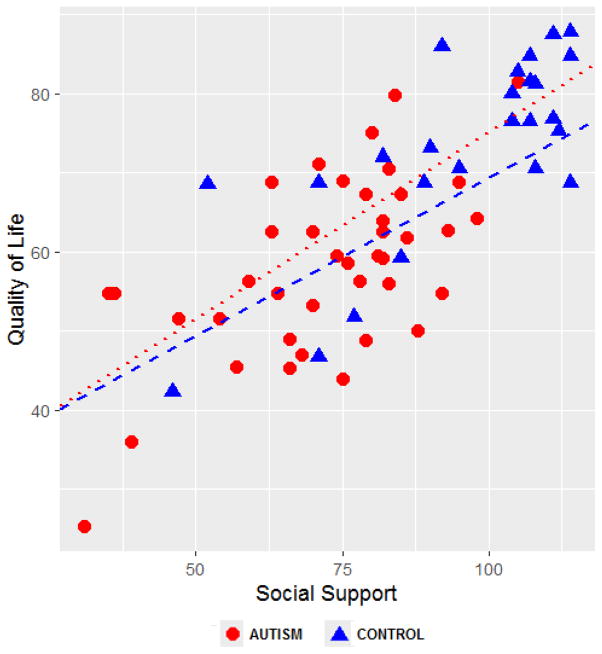

Our regression models (Table 3) accounted for 56% and 62% of the variance in QoL for adults with ASD and typical community volunteers, respectively. There was a significant, negative direct effect of perceived stress on QoL for adults with ASD, B = −.61, t(33) = −2.48, p < .05, but not for typical community volunteers, B = −.43, t(19) = −1.04, p = .31, when controlling for age, sex, full-scale IQ, and treatment exposure. We also identified a significant, positive direct effect of social support on QoL for adults with ASD, B = .27, t(33) = 2.88, p = .01, and typical community volunteers, B = .39, t(19) = 2.74, p < .05, when controlling for age, sex, full-scale IQ, and treatment exposure. These associations are displayed graphically in Figures 2 and 3, which display the direct effect associations between perceived stress and QoL (Figure 2) and social support and QoL (Figure 3) for adults with ASD and typical community volunteers.

Table 3.

Results of Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses Predicting Quality of Life from Perceived Stress and Social Support in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (N = 40) and Typical Community Volunteers (N = 25)

| Predictor (Outcome: QoL) | ASD | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β | SE | β | SE | |

| Step 1 | ||||

| Age | −.16 | .27 | −.05 | .67 |

| Sex | −.27 | 6.16 | −.06 | 6.60 |

| Full-scale IQ | .03 | .13 | .41 | .17 |

| Treatment exposure | .16 | .09 | -- | -- |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Perceived stress | −.37* | .23 | .23 | .41 |

| Social support | .42** | .09 | .61* | .14 |

| R2 Change | .47** | .45** | ||

| Step 3 | ||||

| Perceived stress x social support | −.06 | .01 | .08 | .02 |

| R2 Change | .00 | .00 | ||

| R2 | .56 | .62 | ||

| N | 40 | 25 | ||

Note. ASD = autism spectrum disorder, β = standardized beta, SE = standard error, IQ = intelligence quotient

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Figure 2.

The Association between Perceived Stress and Quality of Life in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Typical Community Volunteers

Figure 3.

The Association between Social Support and Quality of Life in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (N = 40) and Typical Community Volunteers (N = 25)

We found no significant moderation effect of social support on the association between perceived stress and QoL in either adults with ASD, B = −.01, t(32) = −.38, p = .71, or typical community volunteers, B = .01, t(18) = 0.37, p = .72.

Discussion

This study investigated the association between perceived stress and social support and QoL in adults with ASD. We first hypothesized that adults with ASD would have lower levels of social support and lower levels of QoL than typical community volunteers. We then hypothesized that there would be a significant, negative association between perceived stress and QoL for both adults with ASD and typical community volunteers. Finally, we hypothesized that social support would buffer, or moderate, the effect of perceived stress on QoL in adults with ASD and typical community volunteers.

Consistent with prior research (Howlin et al., 2013; Humphrey and Symes, 2010; Symes and Humphrey, 2010), results indicated that adults with ASD have significantly lower levels of social support and QoL than typical community volunteers. The size of these differences were large (Cohen, 1988), with Cohen’s d values of 1.25 and 1.26 for social support and QoL, respectively. Clinically significant differences in QoL between adults with ASD and typical community volunteers were evident, such that typical community volunteers had scores on the WHOQOL-BREF that were above the cutoff for good quality of life while adults with ASD had scores on the WHOQOL-BREF that were below the cutoff for good quality of life. Of note, the size of effect across all analyses indicates that lower levels of social support and QoL may differentiate adults with ASD from typical community volunteers. Findings also indicate that both perceived stress and social support are likely to be independently and substantially associated with on QoL in adults with ASD.

Although we found that greater perceived stress was associated with lower QoL in adults with ASD, perceived stress was not significantly associated with QoL in typical community volunteers. We additionally found that higher levels of social support were associated with higher levels of QoL in both adults with ASD and typical community volunteers. The large effect sizes (Cohen, 1988) for perceived stress and social support on QoL in adults with ASD and a large effect of social support on QoL in typical community volunteers, indicates a strong linear association between perceived stress and social support and QoL, especially in adults with ASD. This indicates that, although adults with ASD report higher perceived stress and lower social support than typical community volunteers, adults with ASD are likely derive benefit from social support given the identified significant association between social support and QoL. In addition, our overall model that took into account perceived stress, social support, age, sex, FSIQ, and treatment exposure explained 56% of the variance in QoL in adults with ASD and 62% of the variance in QoL in typical community volunteers. This finding highlights the importance of perceived stress and social support in QoL and provides strong support that improving these malleable factors through targeted treatment for adults with ASD may indeed improve QoL.

Contrary to our hypotheses, our data did not reveal a buffering effect of social support on the relationship between perceived stress and QoL in either adults with ASD or typical community volunteers. This was unexpected given the large body of research in the general population that finds a buffering effect of social support on the association between perceived stress and well-being (Cohen and McKay, 1984; Cassel, 1976; Cobb, 1976). Our inability to replicate findings of a stress buffering effect of social support found in previous research in our typical community volunteer group is likely due to reduced variance in both perceived stress and social support within our typical community control group, as well as the small sample size of the typical community volunteer group. Findings in adults with ASD align with research that suggests that social support may not buffer the association between perceived stress and QoL for individuals who experience significant distress (Landerman et al., 1989) and new research that finds that participation in social activities does not moderate the association between perceived stress and QoL in adults with ASD (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., in press). It possible that adults with ASD do not know how or when to utilize available social supports, and they may not find social support as effective as a stress reliever because of a combination of well-documented difficulties with social interaction that are characteristic of ASD (Klin et al., 2007) and awareness of one’s own social difficulties, especially in higher functioning adults with ASD (Sperry and Mesibov, 2005).

Our results highlight the extent to which adults with ASD experience lower levels of social support and lower levels of QoL than typical community volunteers. While a relatively large body of research indicates that adults with ASD have few friendships and social relationships (e.g., Howlin et al., 2013; Mazurek, 2014; Renty and Roeyers, 2006; Orsmond et al., 2013), our finding that adults with ASD report significantly lower levels of social support than typical community volunteers indicates that adults with ASD are aware of their limited social connectedness. Notably, while other studies have identified relatively high levels of QoL in adults with ASD compared to population norms (Hong et al., 2016), recent studies that focus on QoL in adults with ASD have not compared QoL in adults with ASD to matched controls (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2016; Helles et al., in press; Hong et al., 2016; Renty and Roeyers, 2006). Thus, findings from the present study that adults with ASD without co-occurring intellectual disabilities experience significantly lower levels of QoL than typically community volunteers, and lower levels of QoL than other mixed-IQ samples of adults with ASD (Hong et al., 2016) expand this recent literature on QoL by offering group comparisons. It also suggests strong construct validity of the WHOQOL-BREF for identifying expected lower levels of QoL in adults with ASD without co-occurring intellectual disabilities.

This study has a number of limitations that may affect the generalizability of results. The primary limitation of this study is that data are cross-sectional, and findings thus cannot address causal relationships. The effects identified by this research are likely bidirectional such that poor QoL can lead to stress and social withdrawal. Future studies should assess bidirectional effects of perceived stress, social support, and QoL in order to tease out causality. Second, the findings of this study are based on a sample of adults with ASD who have relatively intact cognitive functioning and who were capable of participating in a group-based longitudinal intervention program. These adults with ASD have also achieved independence in employment and living environment at higher rates than other samples of adults with ASD (Anderson et al., 2014; Howlin et al., 2004; Seltzer et al., 2011) and thus represent a different population of affected adults than those that have been well-characterized in the literature. Thus, participants are not representative of all adults with ASD, especially those with greater cognitive and communicative difficulties and more challenging behaviors, for whom results could be even more relevant. Third, participants with ASD in the present study were also participants in a clinical trial of two psychosocial treatments (CET and EST), one of which is group-based (CET), for adults with ASD. While neither intervention is designed to specifically target high perceived stress and low social support, both interventions may have had a non-trivial impact on results even though our analyses controlled for exposure to treatment. Finally, co-occurring disorders, including anxiety, were not fully assessed and could have impacted findings.

In spite of these limitations, a number of conclusions can be drawn from the findings of this study. Of note, this study corroborates a growing body of evidence that suggest that high levels of perceived stress are significantly associated with poorer QoL in adults with ASD (Hirvikoski and Blomqvist, 2015; Hong et al., 2016). It also expands the current literature in that it indicates that adults with ASD report lower levels of social support and QoL than typical community volunteers. In addition, findings indicate that lower levels of social support are associated with lower levels of QoL in adults with ASD. These findings, along with similar findings published in other studies (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2015; Hirvikoski and Blomqvist, 2015; Hong et al., 2016; Renty and Roeyers, 2006), highlight the need to develop and assess treatments and services that are designed to help adults with ASD better handle stress and develop more supportive social networks. Testing such interventions could provide information about a causal association between perceived stress and social support and QoL. However, findings from this study indicate that high perceived stress and low social support have a differential impact on QoL in adults with ASD, and thus should be separately targeted with treatments and services. Psychosocial interventions for adults with ASD geared towards improving QoL should focus explicitly on teaching adults with ASD strategies to lower perceived stress and increase social support. Both perceived stress and perceived social support have been shown to be modifiable through targeted interventions designed for the general population (Kirby et al., 2006). Interventions that teach generalizable skills to help adults with ASD lower stress and increase social support might help adults with ASD to achieve better QoL.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the NIH (MH-85851, MH-95783, P30HD003352, T32HD007489); Autism Speaks, (5703 and 8568); Department of Defense (AR100344); and Pennsylvania Department of Health. We are extremely grateful to the individuals with autism spectrum disorder who participated in this study; without their generous support and commitment, our research would not be possible.

Footnotes

Dr. Bishop-Fitzpatrick, Dr. Mazefsky, and Dr. Eack have no conflict of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Lauren Bishop-Fitzpatrick, Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI.

Carla A. Mazefsky, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA

Shaun M. Eack, University of Pittsburgh, School of Social Work, Pittsburgh, PA

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DK, Liang JW, Lord C. Predicting young adult outcome among more and less cognitively able individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:485–494. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Hong J, Smith LE, et al. Characterizing objective quality of life and normative outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorder: An exploratory latent class analysis. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2016;46:2707–2719. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2816-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Mazefsky C, Minshew NJ, et al. The relationship between stress and social functioning in adults with autism spectrum disorder and without intellectual disability. Autism Research. 2015;8:164–173. doi: 10.1002/aur.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Minshew NJ, Mazefsky C, et al. Perception of life as stressful, not biological response to stress, is associated with greater social disability in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2017;47:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2910-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Smith LE, Greenberg JS, et al. Participation in recreational activities moderates the relationship between perceived stress and quality of life in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research. doi: 10.1002/aur.1753. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan J. Social support and schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Archives of psychiatric nursing. 1995;9:68–76. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(95)80003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassel J. The contribution of the social environment to host resistance. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1976;104:107–123. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic medicine. 1976;38:300–314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciencies. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D. Who’s Stressed? Distributions of Psychological Stress in the United States in Probability Samples from 1983, 2006, and 20091. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2012;42:1320–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of health and social behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, McKay G. Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In: Baum A, Taylor SE, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of psychology and health. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, et al. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: Theory, research and application. The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: SS, SO, editors. The Social Psychology of Health. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ditzen B, Heinrichs M. Psychobiology of social support: The social dimension of stress buffering. Restorative neurology and neuroscience. 2014;32:149–162. doi: 10.3233/RNN-139008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Bahorik AL, McKnight SAF, et al. Commonalities in social and non-social cognitive impairments in adults with autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2013a;148:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, et al. Cognitive Enhancement Therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorder: Results of an 18-month feasibility study. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2013b;43:2866–2877. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1834-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First J, Cheak-Zamora NC, Teti M. A qualitative study of stress and coping with transitioning to adulthood with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Family Social Work (in press) [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt P, Lainer I. Addressing the needs of adolescents and adults with autism: A crisis on the horizon. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2011;41:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Helles A, Gillberg IC, Gillberg C, et al. Asperger syndrome in males over two decades: Quality of life in relation to diagnostic stability and psychiatric comorbidity. Autism. doi: 10.1177/1362361316650090. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AB. The environment and disease: Association or causation? Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1965;58:295–300. doi: 10.1177/003591576505800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvikoski T, Blomqvist M. High self-perceived stress and poor coping in intellectually able adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2015;19:752–757. doi: 10.1177/1362361314543530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M. Amelia II: A program for missing data. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Smith LE, et al. Factors associated with subjective quality of life of adults with autism spectrum disorder: Self-report versus maternal reports. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46:1368–1378. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2678-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, et al. Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Moss P, Savage S, et al. Social outcomes in mid- to later adulthood among individuals diagnosed with autism and average nonverbal IQ as children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:572–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N, Symes W. Perceptions of social support and experience of bullying among pupils with autistic spectrum disorders in mainstream secondary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education. 2010;25:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby ED, Williams VP, Hocking MC, et al. Psychosocial benefits of three formats of a standardized behavioral stress management program. Psychosomatic medicine. 2006;68:816–823. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000238452.81926.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klin A, Saulnier CA, Sparrow SS, et al. Social and communication abilities and disabilities in higher functioning individuals with autism spectrum disorders: The Vineland and the ADOS. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:748–759. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landerman R, George LK, Campbell RT, et al. Alternative models of the stress buffering hypothesis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1989;17:625–642. doi: 10.1007/BF00922639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy A, Perry A. Outcomes in adolescents and adults with autism: A review of the literature. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5:1271–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, et al. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Lecouteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magiati I, Tay XW, Howlin P. Cognitive, language, social and behavioural outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review of longitudinal follow-up studies in adulthood. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt DW. You should standardize the predictor variables in your regression models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1980;75:87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek MO. Loneliness, friendship, and well-being in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2014;18:223–232. doi: 10.1177/1362361312474121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newschaffer CJ, Falb MD, Gurney JG. National autism prevalence trends from United States special education data. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e277–e282. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond GI, Shattuck PT, Cooper B, et al. Social participation among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1833-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Kitayama S, Karasawa M, et al. Clarifying the links between social support and health: Culture, stress, and neuroticism matter. Journal of Health Psychology. 2013;18:226–235. doi: 10.1177/1359105312439731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Renty JO, Roeyers H. Quality of life in high-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder: The predictive value of disability and support characteristics. Autism. 2006;10:511–524. doi: 10.1177/1362361306066604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Taylor JL, et al. Adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. In: Amaral DG, Dawson G, Geschwind DH, editors. Autism Spectrum Disorders. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial: A report from the WHOQOL Group. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13:299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry LA, Mesibov GB. Perceptions of social challenges of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2005;9:362–376. doi: 10.1177/1362361305056077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhausen HC, Mohr Jensen C, Lauritsen M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the long-term overall outcome of autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2016 doi: 10.1111/acps.12559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symes W, Humphrey N. Peer-group indicators of social inclusion among pupils with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) in mainstream secondary schools: A comparative study. School Psychology International. 2010;31:478–494. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale® 4th Edition (WAIS®-IV) Harcourt Assessment; San Antonio, TX: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:551–558. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams VP, Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Lane JD, et al. Video-based coping skills to reduce health risk and improve psychological and physical well-being in Alzheimer’s disease family caregivers. Psychosomatic medicine. 2010;72:897–904. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181fc2d09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]