Abstract

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are more common among boys than girls. The mechanisms responsible for ASD symptoms and their sex differences remain mostly unclear. We previously identified collapsin response mediator protein 4 (CRMP4) as a protein exhibiting sex-different expression during sexual differentiation of the hypothalamic sexually dimorphic nucleus. This study investigated the relationship between the sex-different development of autistic features and CRMP4 deficiency. Whole-exome sequencing detected a de novo variant (S541Y) of CRMP4 in a male ASD patient. The expression of mutated mouse CRMP4 S540Y, which is homologous to human CRMP4 S541Y, in cultured hippocampal neurons derived from Crmp4-knockout (KO) mice had increased dendritic branching, compared to those transfected with wild-type (WT) Crmp4, indicating that this mutation results in altered CRMP4 function in neurons. Crmp4-KO mice showed decreased social interaction and several alterations of sensory responses. Most of these changes were more severe in male Crmp4-KO mice than in females. The mRNA expression levels of some genes related to neurotransmission and cell adhesion were altered in the brain of Crmp4-KO mice, mostly in a gender-dependent manner. These results indicate a functional link between a case-specific, rare variant of one gene, Crmp4, and several characteristics of ASD, including sexual differences.

Introduction

Since Leo Kanner first reported ‘autistic disturbances of affective contact’ in eight males and three females with symptoms of what would later be called autism1, it has been well established that a consistent feature of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in humans is male predominance. The ratio of males to females ASD is generally around 4:12, although the ratio reported ranges from 1.33:1 to 15.7:1. In addition, the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network conducted a multi-site, population-based study in the United States that revealed an increase in the ratio of males to females among 8-year-old children with ASD over the past 10 years3. This ratio increased from 4.25:1 in children born in 1994 to 4.54:1 in children born in 1998 and to 4.65:1 in children born in 2000. To date, hundreds to thousands of genes have been considered as autism candidates or susceptibility genes in autism gene databases4. While some of these genes, including SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains 1 (SHANK1), retinoic acid-related orphan receptor alpha (RORA) and methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2), are reported as possibly involved in the male predominance of ASD5–7, there is still a lack of definitive information regarding the genes or mechanisms underlying this sex difference. The increasing male to female ratio in ASD may lead to the hypothesis that the regulation of genes related to sex difference in ASD is affected by biological or environmental exposures (e.g. exposure to hormones or endocrine disruptors), making males more susceptible to the disorder8, although there may be other possibilities including the expanding diagnostic criteria of ASD, which lead to the ascertainment of a greater number of boys with high functioning autism9,10.

Our previous proteomics studies identified collapsin response mediator protein 4 (CRMP4), also called DPYSL3, a member of the CRMP family (CRMP1–5), as a protein exhibiting sex-associated differences in expression during differentiation of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the hypothalamus11. In addition, the expression of Crmp4 mRNA in the hypothalamic sexually dimorphic nucleus on post-natal day 0 (PD0) was altered in females treated with androgen during the late pre-natal stage11, indicating that Crmp4 expression is sex-steroid dependent in the rat, at least in this specific brain region.

It was previously reported that a missense variant in the CRMP4 gene was found, in addition to four other de novo variants, in an ASD proband from the Simons Simplex Collections12. In the present study, we identified another likely pathogenic missense variant in the CRMP4 gene in a male with ASD using exome sequencing. Although such variants in CRMP4 appear to be very rare, they may provide clues to the pathways and mechanisms responsible for the male dominance of ASD symptoms. In addition, through the assessment of behaviour as well as gene expression in Crmp4-knockout (KO) mice of both sexes, we examined the role of Crmp4 dysfunction in ASD pathogenesis.

Results

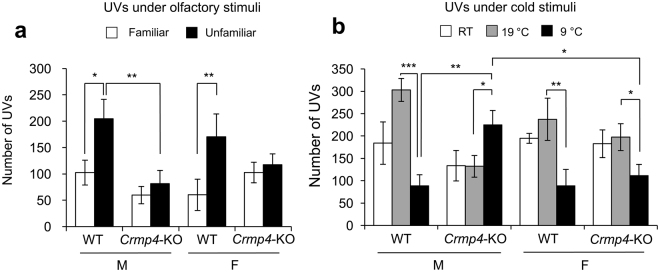

De novo variant of CRMP4 (DPYSL3) in sporadic autism case

As a part of the efforts to identify genes involved in the pathogenesis of ASD, the Central Ohio Registry for Autism (CORA)13 was initiated to enroll isolated cases and multiplex families with one or more children diagnosed with ASD. Detailed clinical phenotyping, including family history and psychological testing, and molecular studies were performed according to the institutional guidelines. We undertook exome sequencing in 72 families in which there appeared to be an isolated, sporadic case of ASD. In patient A379, we detected a de novo cytosine to adenine transversion at nucleotide 1622 of the human full length cDNA (c.1622C > A, an arrow in Fig. 1), which leads to the change of a serine to a tyrosine at amino acid position 541 (p.Ser541Tyr) of the CRMP4 protein [NM_001197294.1 (DPYSL3):c.1622C > A:p.(Ser541Tyr); NC_000005.9:g.146778646G > T]. DPYSL3 is also called CRMP-4, CRMP4, dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 3 (DRP-3, DRP3), LCRMP, TUC4, Unc-33-like phosphoprotein, ULIP and Ulip-1. In the patient, no other damaging de novo variants were found. The C to A transition in CRMP4 was not present in the parents (Fig. 1) or siblings (data not shown).

Figure 1.

de novo variant of CRMP4 in sporadic autism case. A downward arrow indicates the mutated residue (C > A). This mutation resulted in a change in the amino acid sequence of CRMP4 (S541Y). Nucleotides are shown in coloured, single-letter codes.

The variant is in a highly conserved region of the predicted protein (GERP++5.47)14 and is predicted borderline deleterious by SIFT (0.07)15 and probably damaging by Polyphen2 (0.992)16. Further, it is predicted to be deleterious by both of the ensemble-based scores MetaSVM and MetaLR (0.142 and 0.566, respectively)17, which integrate additional functional prediction and conservation scores, as well as allele frequency. This rare variant is not reported in either the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) database or the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD). The Human Splicing Finder predicts the creation of an exonic splicing silencer and potential alteration of splicing. Both the adaptive boosting (ADA) and random forest (RF) method scores, from the database of human SNVs within splicing consensus regions (dbNSFP-dbscSNV), also predict splice alteration (0.977 and 0.712, respectively; PMID: 25416802).

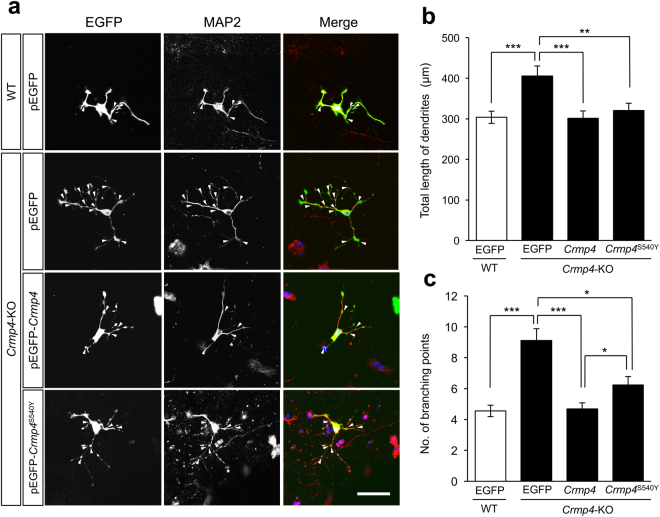

Effect of Crmp4-KO, Crmp4 and Crmp4S540Y on the dendritic morphology of cultured hippocampal neurons

We and others have previously reported that the deficiency of Crmp4 affects dendritic morphology18,19. In addition, there have been several recent reports demonstrating altered dendritic development in ASD mouse models20,21, leading us to focus on dendritic development in the present study. To examine the functional consequences of the missense variant found in the ASD patient, we studied the dendritic arborisation in cultured hippocampal neurons which are routinely used for analysis of dendrites. In this study, primary hippocampal neurons from male animals were used to assess the general effects of Crmp4 or Crmp4 S540 expressions on dendritic growth. We compared WT hippocampal neurons with Crmp4-KO hippocampal neurons transfected with a construct expressing Crmp4 S540Y that contains a point mutation in the homologous site of S541 in human CRMP4 or WT Crmp4 (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Effect of Crmp4 or Crmp4 S540Y gene expression on the dendritic arborisation of cultured hippocampal cells. S540Y mutation in mouse Crmp4 gene is homologous to S541Y in human CRMP4 gene found in the ASD patient. Representative images of cultured hippocampal cells from wild-type (WT) mice transfected with control (pEGFP) vector, those from Crmp4-KO mice transfected with pEGFP vector, those from Crmp4-KO mice transfected with pEGFP-Crmp4 vector, and those from Crmp4-KO mice transfected with pEGFP-Crmp4 S540Y (a). Cultured cells were fixed at DIV-3 (3 days in vitro) with 4% paraformaldehyde and then immunocytochemically stained with antibodies against MAP2 (red) and EGFP (green). Nuclei were stained with Höechst 33258 (blue). The total length of MAP2- and EGFP-double labelled dendrites and the number of the dendritic branching (arrow heads) were measured for each double labelled neuron. Scale bar: 50 µm. Bar graphs showing the average of total dendritic length (b) and the average of the number of dendritic branches (c). n = 81, 71, 82, and 61 for WT neurons transfected with pEGFP, Crmp4-KO neurons transfected with pEGFP, Crmp4-KO neurons transfected with pEGFP-Crmp4, and Crmp4-KO neurons transfected with pEGFP-Crmp4 S540Y, respectively, from at least three independent experiments. Bars indicate mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (*p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc tests).

As shown in Fig. 2b and c, the total length of dendrites and the number of branching points (arrowheads in Fig. 2a) were significantly increased in neurons derived from Crmp4-KO mice transfected with the control pEGFP vector than in those derived from WT mice transfected with the same control vector or in those derived from Crmp4-KO mice transfected with pEGFP-Crmp4 (p < 0.001). The total dendritic length of each double-labelled neuron derived from Crmp4-KO mice transfected with pEGFP-Crmp4 S540Y did not differ significantly from those derived from Crmp4-KO mice transfected with pEGFP-Crmp4 and those derived from WT mice transfected with pEGFP (Fig. 2b). However, neurons derived from Crmp4-KO mice transfected with pEGFP-Crmp4 S540Y showed significantly greater numbers of dendritic branching points than those derived from Crmp4-KO mice transfected with pEGFP-Crmp4 (Fig. 2c, p < 0.05), although they had less branching points than the neurons derived from Crmp4-KO mice transfected with pEGFP (p < 0.05). These cell culture studies demonstrate that the S540Y mutation in the mouse Crmp4 gene, which is homologous to S541Y in the human CRMP4 gene, results in a partially reduced CRMP4 function in suppressing dendritic branching.

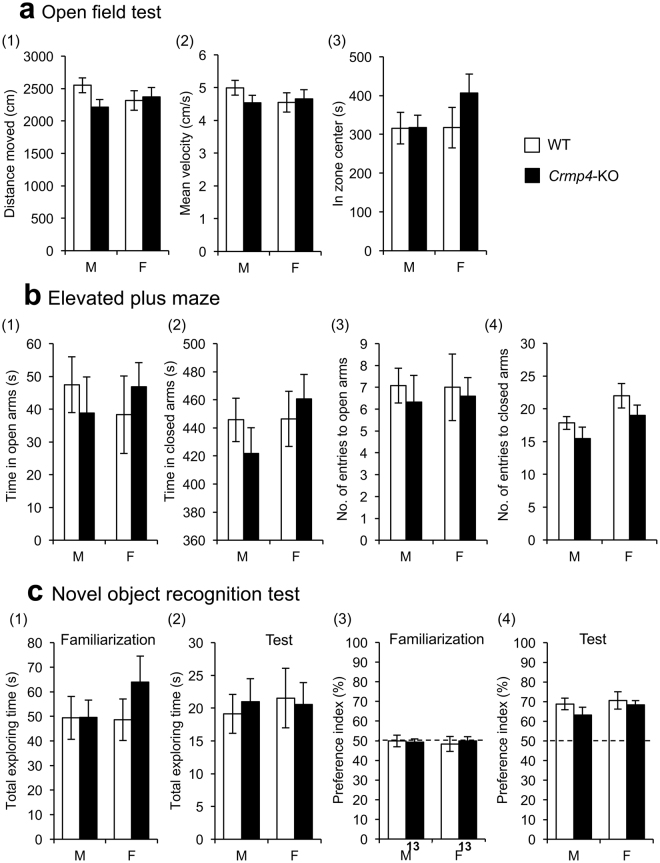

Crmp4-KO mice demonstrate normal activities and responses in the open-field test, elevated plus maze, and novel object recognition test

To examine the general characteristics of Crmp4-KO mice, KO mice and their WT littermates were subjected to several behavioural tests. Specifically, we focused on behaviors in young or adolescent mice because we speculated that early behavioral deficits in these Crmp4-KO mice might link better to ASD-like phenotypes that are apparent in childhood. Testing was performed sequentially on the same cohort of animals at approximately one week intervals with the least invasive (upsetting) tests performed first. Initially, open field tests were performed at 4 weeks of age. Two-way ANOVA revealed that there were no significant differences by genotype and sex and no interaction between these two factors (genotype × sex) in the distance moved (Fig. 3a-(1)), velocity (Fig. 3a-(2)), or time spent in the central region (Fig. 3a-(3)) in the open-field test. Elevated plus maze test was further performed at 4 weeks of age to assess the anxiety levels of the mice. Data showed no significant differences regarding the time spent in open (Fig. 3b-(1)) and closed (Figs. 3b-(2)) arms and in the number of entries to open (Fig. 3b-(3)) and closed (Fig. 3b-(4)) arms. These results suggest that Crmp4-KO mice of both sexes have normal locomotive activity and anxiety levels as assessed by the testing modality.

Figure 3.

Behavioural phenotypes of wild-type (WT) and Crmp4-KO mice. (a) Open-field test for 20 min with total distance moved (1), mean velocity (2) and total time spent in the central zone (3). Male WT, n = 17; male Crmp4-KO, n = 15; female WT, n = 12; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 14. (b) Elevated plus maze (distance from floor = 60 cm) comprising two open arms (27.5 × 4.5 cm) and two closed arms made of clear Plexiglas (27.5 × 4.5 × 14 cm) extending from a central (4.5 × 4.5 cm) platform for 10 min. The time spent in open (1) and closed (2) arms and the number of entries to open (3) and closed (4) arms in the elevated plus maze test. Male WT, n = 11; male Crmp4-KO, n = 10; female WT, n = 9; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 12. (c) Novel object recognition test to assess memory acquisition and retention performance. Total duration of exploring the objects during familiarisation (1) and test (2) phases of the novel object recognition test. Preference index, which expresses the ratio of the amount of time spent exploring novel object during familiarisation (3) and test (4) phases. Male WT, n = 13; male Crmp4-KO, n = 17; female WT, n = 13; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 13. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

The novel object recognition test at 5 weeks of age showed that the total exploration time in the familiarisation phase (Fig. 3c-(1)) as well as in the test phase (Fig. 3c-(2)) was not significantly different between genotypes and sexes and that there was no interaction between these two factors (two-way ANOVA). These data indicate that exploration behaviour towards inanimate objects is unaffected by Crmp4 deletion in both sexes, although female Crmp4-KO mice tended to spend more time exploring during the familiarisation phase (Fig. 3c-(1)). In addition, the amount of time spent exploring the same objects (‘I’ and ‘II’ in Supplementary Fig. S1) did not differ between genotypes nor between sexes during the familiarisation phase (Fig. 3c-(3)). In the test phase, WT and Crmp4-KO mice of both sexes spent more time exploring the novel object (denoted by ‘III’ in Supplementary Fig. S1) than the familiar one (Fig. 3c-(4)), with no significant differences in the time between genotypes and sexes. These results indicate normal abilities of Crmp4-KO mice of both sexes in short-term memory acquisition.

The precise behavioural data and their results from statistical analysis are all shown in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

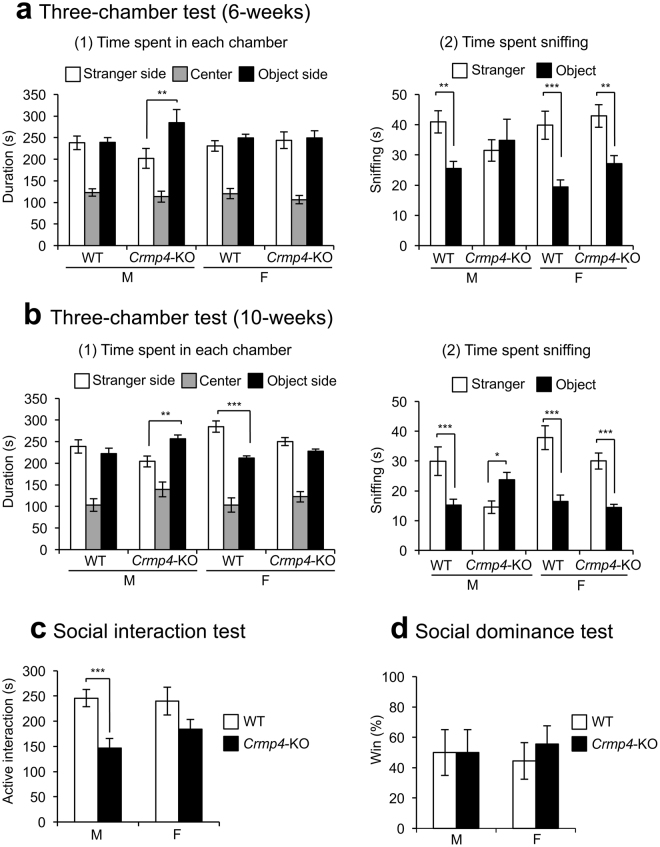

Male Crmp4-KO mice demonstrate decreased social behaviour in social contact but not in social dominance

The three-chamber test at 6 weeks of age revealed that only Crmp4-KO males stayed for a significantly longer time in the ‘object side chamber’ than in the ‘stranger side chamber’ (Fig. 4a-(1), p < 0.01). WT mice of both sexes and Crmp4-KO females spent more time sniffing the stranger mouse than the novel object (Fig. 4a-(2)). These differences are significant by post hoc PSDL test, but the differences in male WT and female Crmp4-KO mice did not survive correction for multiple testing, such as Bonferroni correction (for p-values from multiple comparison, see Supplementary table S2). The time spent sniffing the novel object versus the stranger mouse was not significantly different in Crmp4-KO males (Fig. 4a-(2)).

Figure 4.

Social behaviours in wild-type (WT) and Crmp4-KO mice. (a and b) The three-chamber test performed at 6-weeks [(a), male WT, n = 11; male Crmp4-KO, n = 10; female WT, n = 11; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 12] and 10-weeks [(b), male WT, n = 10; male Crmp4-KO, n = 8; female WT, n = 9; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 11]. The testing apparatus comprised two sides and one centre chamber (19 × 40 × 22 cm, each) divided by two doors (11.5 cm wide). An age-matched unfamiliar C57BL/6N WT mouse of the same sex (stranger) enclosed in a wire cage (φ82 × 93.1 mm) was placed behind the partition in one side chamber (stranger side chamber) and an empty wire cage (novel object) was placed behind the partition in the other side chamber (object side chamber) of the three-chambered apparatus. Time spent in each chamber (1) and time spent sniffing stranger and novel object (2). (c) Social interaction test to assess active interaction time in 10 min. Male WT, n = 15; male Crmp4-KO, n = 17; female WT, n = 12; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 17. (d) The tube test to show the difference in social dominance between WT and Crmp4-KO mice. An age-matched pair of unfamiliar mice (one WT and one Crmp4-KO) of the same sex and similar body weight (within 5% difference) was placed into opposite ends of a clear acrylic tube and simultaneously released. The test ended when one mouse completely retreated from the tube, who was assigned a score of zero (loser). The remaining mouse was assigned a score of one (winner). Male WT, n = 6; male Crmp4-KO, n = 6; female WT, n = 8; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 8. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (three-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc tests).

Since the three-chamber test at 6 weeks of age suggested possible differences between genotypes, we further performed the same experiment using a separate cohort of older mice (10 weeks of age, Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table S1, and S2). The results showed that WT females spent a significantly longer time in the ‘stranger side chamber’ than in the ‘object side chamber’ (Fig. 4b-(1), p < 0.001), whereas Crmp4-KO males spent a significantly longer time in the ‘object side chamber’ than in the ‘stranger side chamber’ (Fig. 4b-(1), p < 0.01). The time sniffing the stranger mouse was significantly longer than that sniffing the novel object in WT mice of both sexes and in Crmp4-KO females (Fig. 4b-(2), p < 0.001). Conversely, Crmp4-KO males spent a significantly longer time sniffing the novel object than the stranger mouse (Fig. 4b-(2), p < 0.05).

We further investigated social behaviours of Crmp4-KO mice using social interaction test at 6 weeks of age (Fig. 4c). Crmp4-KO mice spent a significantly shorter time in active interaction than WT littermates (WT and Crmp4-KO, 243.28 ± 13.75 and 169.74 ± 13.03 s, respectively), as determined by two-way ANOVA. Post-hoc comparison revealed that Crmp4-KO males displayed significantly less active interaction than WT males (p < 0.001, Fig. 4c, left bars); however, Crmp4-KO females did not differ significantly from WT females in active interaction (Fig. 4c, right bars). The results obtained from the three-chamber and social interaction tests indicate a decreased social behaviour in Crmp4-KO males.

The tube test was performed at 6 weeks of age to examine social dominance (Fig. 4d). Both WT and Crmp4-KO mice had equal winners, indicating that the decreased social activities observed in Crmp4-KO mice are unlikely to be due to altered social dominance. It is also unlikely that the decreased social interaction in Crmp4-KO males arose from an aversion to novelty because social dominance and exploration towards novelty did not differ between WT and Crmp4-KO mice of either sex (Figs 3c and 4d).

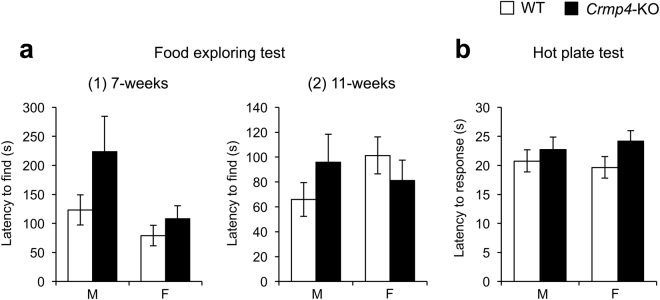

Crmp4-KO mice exhibit normal olfactory function at 7 and 11 weeks of age

We also tested the olfactory function in mice using the food exploring test at 7 and 11 weeks of age because an olfactory deficit would interfere with social behaviour (Fig. 5a). Although Crmp4-KO males required more time to find food than mice in other test groups at 7 weeks of age (Fig. 5a-(1)), there were no significant differences, as determined by two-way ANOVA (Supplementary Table S1). The food exploring test in 11-week-old mice also revealed no significant differences in the olfactory function between genotypes and sexes (Fig. 5a-(2), Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 5.

Food exploring and hot plate tests. (a) Food exploring test at 7-weeks [(1), male WT, n = 15; male Crmp4-KO, n = 15; female WT, n = 12; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 16] and 11-weeks [(2), male WT, n = 11; male Crmp4-KO, n = 15; female WT, n = 10; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 15] to measure time needed to find buried food. (b) Hot plate test to assess acute pain sensitivity to a thermal stimulus. The time needed to respond with a hind paw lick, paw shake or jump was measured. Male WT, n = 21; male Crmp4-KO, n = 16; female WT, n = 26; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 24. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Crmp4-KO mice show normal pain sensitivity

Next, to assess pain sensitivity, the hot plate test at 55 °C was performed at 8 weeks of age (Fig. 5b). The time required to respond to thermal stimulation did not differ significantly between WT and Crmp4-KO mice of either sex.

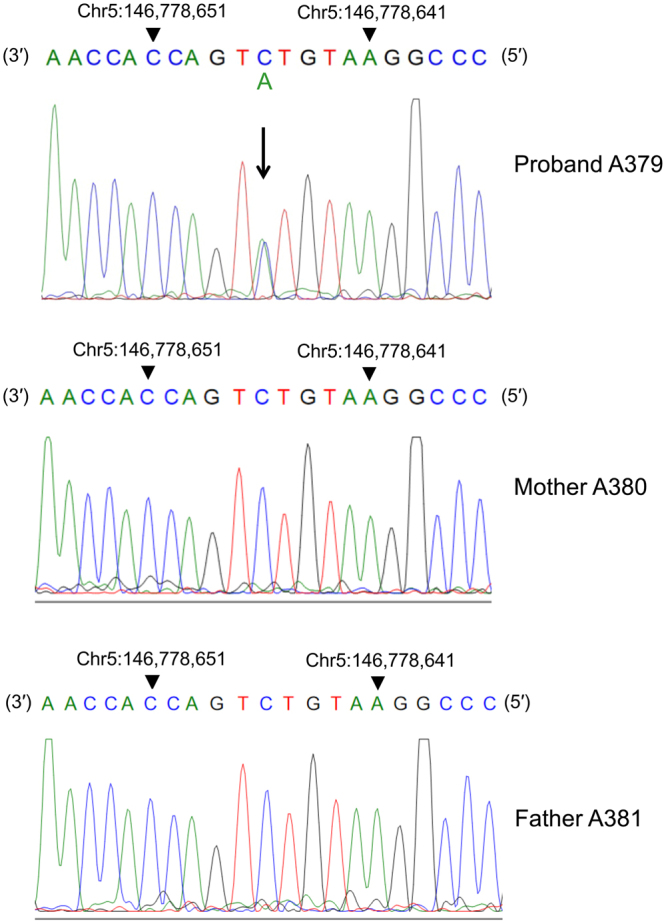

Familiar and unfamiliar beddings induced different emission of ultrasonic vocalisations (UVs) in WT but not in Crmp4-KO pups

An association has been proposed between the patterns of sensory differences and core deficits of ASD22. Sensory differences are now included in the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD23. The emission of UVs by mouse pups is a social behaviour that shows attachment to the mother. In addition, UVs are the incidental by-product of normal physiological responses to sensory stimulation in neonatal mice24. The experiments of UVs were performed at PD7 because previous studies have shown that C57/BL6 mice pups produce more UVs at PD7 than at any other postnatal stage25,26.

The number of UVs emitted by pups under two different smell stimuli, familiar and unfamiliar nest bedding, was counted (Fig. 6a). Three-way ANOVA showed that exposure to unfamiliar bedding induced significantly more UVs than that to familiar bedding (p < 0.01) and that Crmp4-KO pups produced significantly less UVs than WT pups (p < 0.05). In addition, two significant interactions (genotype × bedding and genotype × sex, p < 0.05 each) were identified. The number of UVs produced by WT pups of both sexes was significantly greater during exposure to the unfamiliar bedding than during exposure to the familiar bedding (males and females, p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively, Fig. 6a), as reported by previous studies27–29. In contrast, the number of UVs emitted by male and female Crmp4-KO pups did not differ significantly between familiar and unfamiliar bedding (Fig. 6a). These results suggest that while WT pups of both sexes could discriminate between the smell of familiar and unfamiliar bedding, Crmp4-KO pups of both sexes could not discriminate well between these two bedding types. It is also possible that the pups could retain this ability but did not change their behaviour. In addition, a significant difference in the number of UVs between WT and Crmp4-KO pups in response to unfamiliar bedding was shown in males but not in females (p < 0.01, Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

Ultrasonic vocalisations (UVs) emitted by mouse pups under different sensory stimuli. (a) Mean numbers of UVs emitted from wild-type [WT (male, n = 11: female, n = 12)] and Crmp4-knockout pups (male, n = 14: female, n = 16) were compared under exposure to familiar and unfamiliar nest bedding (b) and under exposure at 23 °C [room temperature, RT (male WT, n = 8; male Crmp4-KO, n = 8; female WT, n = 13; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 6)], 19 °C (male WT, n = 11; male Crmp4-KO, n = 15; female WT, n = 14; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 16), and 9 °C (male WT, n = 13; male Crmp4-KO, n = 14; female WT, n = 12; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 10). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (three-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc tests).

Male Crmp4-KO pups showed significant abnormalities in thermal perception compared with WT pups

Because some human ASD patients are reported to have abnormalities in thermal detection30,31, we examined the thermal perception in Crmp4-KO mice using UV emissions at PD7 (Fig. 6b). Three-way ANOVA revealed that the number of UVs was significantly affected by temperature (p < 0.001, Supplementary table S1), and it also showed two significant interactions (genotype × temperature and genotype × sex × temperature). As shown in Fig. 6b, when male WT pups were kept at 9 °C, they produced significantly fewer UVs than those kept at 19 °C (p < 0.001). Similarly, the number of UVs was greater at 19 °C than at 9 °C in female WTs and Crmp4-KOs (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively). Surprisingly, in contrast to other animal groups, the number of UVs was greater at 9 °C than at 19 °C in Crmp4-KO males (p < 0.05).

In addition, no significant differences were observed in the number of UVs emitted at RT, 19 °C or 9 °C between female WT and Crmp4-KO pups. However, significant differences were found in the number of UVs between male WT and Crmp4-KO pups when they were kept at 9 °C (p < 0.01). The significant difference was also found in the number of UVs emitted at 9 °C between male and female Crmp4-KO pups (p < 0.05).

Altered and sexually dimorphic expression of genes related to neural excitation and inhibition in Crmp4-KO mice

We examined the mRNA expression of Crmp4 and several genes for receptors, synthetic enzymes for neurotransmitters and transporters, most of which have been implicated in relation to ASD, such as glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and dopamine receptor genes32–34. The expression of serotonin transporter (SERT) mRNA was additionally examined in the raphe nucleus where it is reported to be associated with human ASD susceptibility35. In addition, we examined the mRNA expression of genes related to cell adhesion, such as Ncam1 and N-cadherin, because they are involved in establishing neural connectivity36. The samples for real-time RT-PCR were collected from mice at 8 weeks of age, since abnormal social behaviors were detected at 6 and 10 weeks of age by three chamber test. The gene expressions with significant differences among animal groups are listed in Table 1, and p-values for multiple comparisons are shown in Supplementary Table S3. The gene expressions with no significant differences are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

Table 1.

Gene expressions with significant differences among groups in adults.

| Brain region | Genes | F-statistics, degree of freedom, and p-values for two-way ANOVA | Expression levels | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For each factor and interaction | Fold differences | Male | Female | ||||||||

| Genotype | Sex | Genotype × Sex | WT vs. Crmp4-KO (Crmp4-KO/WT) | Male vs. Female (Female/Male) | WT | Crmp4-KO | WT | Crmp4-KO | |||

| Olfactory bulb | GluR2 | F(3,12) = 3.013, p = 0.072 | F(1,12) = 5.843, p = 0.032 | F(1,12) = 1.215, p = 0.292 | F(1,12) = 1.981, p = 0.185 | 1.969 | 1.352 | 0.532 ± 0.188 | 0.564 ± 0.141 | 0.472 ± 0.122 | 0.952 ± 0.120* |

| VGluT1 | F(3,12) = 16.871, p < 0.001 | F(1,12) = 36.167, p < 0.001 | F(1,12) = 11.327, p = 0.006 | F(1,12) = 3.117, p = 0.103 | 1.389 | 0.833 | 0.815 ± 0.025† | 1.009 ± 0.062* | 0.585 ± 0.028 | 0.935 ± 0.053* | |

| VGluT2 | F(3,12) = 3.191, p = 0.063 | F(1,12) = 1.300, p = 0.276 | F(1,12) = 5.707, p = 0.034 | F(1,12) = 2.566, p = 0.135 | 1.116 | 1.266 | 0.849 ± 0.051 | 0.803 ± 0.029† | 0.920 ± 0.170 | 1.172 ± 0.032 | |

| GABAAα1 | F(3,12) = 62.224, p < 0.001 | F(1,12) = 78.549, p < 0.001 | F(1,12) = 45.705, p < 0.001 | F(1,12) = 62.418, p < 0.001 | 1.642 | 1.455 | 1.367 ± 0.120 | 1.459 ± 0.059† | 1.259 ± 0.051 | 2.854 ± 0.126* | |

| GABAAγ2 | F(3,12) = 11.147, p = 0.001 | F(1,12) = 20.106, p = 0.001 | F(1,12) = 1.439, p = 0.253 | F(1,12) = 11.894, p = 0.005 | 1.524 | 1.118 | 1.274 ± 0.112 | 1.410 ± 0.194† | 0.978 ± 0.059 | 2.021 ± 0.126* | |

| GABABR1 | F(3,12) = 7.722, p = 0.044 | F(1,12) = 16.841, p = 0.001 | F(1,12) = 4.138, p = 0.065 | F(1,12) = 2.184, p = 0.165 | 1.839 | 1.342 | 0.182 ± 0.010 | 0.285 ± 0.068† | 0.204 ± 0.036 | 0.424 ± 0.012* | |

| VGAT | F(3,12) = 7.897, p = 0.004 | F(1,12) = 12.939, p = 0.004 | F(1,12) = 1.182, p = 0.298 | F(1,12) = 9.570, p = 0.009 | 1.426 | 1.113 | 0.317 ± 0.029 | 0.335 ± 0.057† | 0.249 ± 0.015 | 0.476 ± 0.018* | |

| Ncam1 | F(3,12) = 7.576, p = 0.004 | F(1,12) = 20.543, p = 0.001 | F(1,12) = 2.124, p = 0.166 | F(1,12) = 0.012, p = 0.913 | 1.839 | 1.342 | 1.214 ± 0.043 | 1.573 ± 0.051* | 1.085 ± 0.096 | 1.462 ± 0.113* | |

| N-cadherin | F(3,12) = 2.283, p = 0.131 | F(1,12) = 6.782, p = 0.023 | F(1,12) = 0.007, p = 0.936 | F(1,12) = 0.061, p = 0.809 | 1.321 | 0.913 | 1.178 ± 0.067 | 1.385 ± 0.041 | 1.149 ± 0.153 | 1.400 ± 0.035 | |

| Hippocampus | GluR1 | F(3,12) = 3.793, p = 0.040 | F(1,12) = 1.031, p = 0.330 | F(1,12) = 0.916, p = 0.357 | F(1,12) = 9.431, p = 0.010 | 1.171 | 0.861 | 0.544 ± 0.066 | 0.999 ± 0.121*† | 0.860 ± 0.164 | 0.550 ± 0.114 |

| GluR2 | F(3,12) = 2.857, p = 0.086 | F(1,12) = 6.301, p = 0.029 | F(1,12) = 0.106, p = 0.750 | F(1,12) = 2.874, p = 0.118 | 1.505 | 1.055 | 0.227 ± 0.061 | 0.469 ± 0.044* | 0.343 ± 0.022 | 0.400 ± 0.101 | |

| VGluT1 | F(3,12) = 1.942, p = 0.177 | F(1,12) = 5.266, p = 0.041 | F(1,12) = 0.169, p = 0.666 | F(1,12) = 0.365, p = 0.557 | 1.160 | 0.973 | 0.916 ± 0.079 | 1.017 ± 0.042 | 0.850 ± 0.073 | 1.031 ± 0.047 | |

| GABAAα1 | F(3,12) = 3.623, p = 0.045 | F(1,12) = 3.983, p = 0.069 | F(1,12) = 5.771, p = 0.033 | F(1,12) = 1.116, p = 0.312 | 1.211 | 1.265 | 0.194 ± 0.010 | 0.215 ± 0.010† | 0.224 ± 0.010 | 0.291 ± 0.041 | |

| GABABR1 | F(3,12) = 3.548, p = 0.048 | F(1,12) = 0.379, p = 0.549 | F(1,12) = 10.185, p = 0.008 | F(1,12) = 0.078, p = 0.784 | 1.071 | 1.514 | 0.135 ± 0.008 | 0.144 ± 0.008† | 0.204 ± 0.034 | 0.220 ± 0.027 | |

| N-cadherin | F(3,12) = 2.266, p = 0.133 | F(1,12) = 5.333, p = 0.040 | F(1,12) = 1.074, p = 0.321 | F(1,12) = 0.392, p = 0.543 | 0.948 | 1.126 | 1.028 ± 0.046 | 0.939 ± 0.037 | 1.118 ± 0.032 | 1.096 ± 0.083 | |

| Cortex | VGluT2 | F(3,12) = 3.920, p = 0.037 | F(1,12) = 5.273, p = 0.040 | F(1,12) = 6.351, p = 0.027 | F(1,12) = 0.135, p = 0.719 | 0.735 | 0.712 | 0.136 ± 0.021 | 0.100 ± 0.009 | 0.097 ± 0.012 | 0.071 ± 0.007 |

| GABAAγ2 | F(3,12) = 5.557, p = 0.013 | F(1,12) = 14.229, p = 0.003 | F(1,12) = 0.018, p = 0.896 | F(1,12) = 2.425, p = 0.145 | 0.667 | 1.011 | 0.097 ± 0.013 | 0.077 ± 0.006 | 0.113 ± 0.011 | 0.064 ± 0.004* | |

| GABABR1 | F(3,12) = 5.623, p = 0.012 | F(1,12) = 7.181, p = 0.020 | F(1,12) = 7.752, p = 0.017 | F(1,12) = 1.937, p = 0.189 | 0.773 | 0.765 | 0.115 ± 0.012† | 0.081 ± 0.008* | 0.080 ± 0.006 | 0.069 ± 0.007 | |

| Ncam1 | F(3,12) = 9.911, p = 0.001 | F(1,12) = 29.650, p < 0.001 | F(1,12) = 0.011, p = 0.919 | F(1,12) = 0.071, p = 0.795 | 0.671 | 1.008 | 1.227 ± 0.085 | 0.839 ± 0.068* | 1.255 ± 0.084 | 0.827 ± 0.060* | |

| N-cadherin | F(3,12) = 20.827, p < 0.001 | F(1,12) = 6.446, p = 0.026 | F(1,12) = 53.076, p < 0.001 | F(1,12) = 2.960, p = 0.111 | 0.484 | 1.276 | 1.105 ± 0.121 | 0.592 ± 0.029* | 1.498 ± 0.117 | 0.667 ± 0.070* | |

Asterisks indicate significant differences between WT and Crmp4-KO mice of same sex (*p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc tests). Dagger indicates significant difference between male and female mice of the same genotype († p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s PLSD post-hoc tests). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Crmp4 mRNA expression was not detected in Crmp4-KO mice and it was not significantly different between male and female WT adults in the olfactory bulb (OB), hippocampus, and cortex (Supplementary Table S4). We found significant differences by genotype, sex, or interaction of these factors in GluR1, GluR2, VGluT1, VGluT2, GABAAα1, GABAAγ2, GABABR1, VGAT, Ncam1 and N-cadherin mRNA expressions (two-way ANOVA) (Table 1). However, Crmp4 deficiency-dependent effects in mRNA expression of these genes varied depending on the sex and brain region.

In the OB, GluR2 mRNA expression in Crmp4-KO females was significantly higher than in WT females. VgluT1 and Ncam1 mRNA expressions in the OB were significantly higher in Crmp4-KO mice of both sexes than in WT mice of the same sex. In addition, VgluT1 mRNA expression was significantly lower in WT females than in WT males. VgluT2 mRNA expression was significantly higher in Crmp4-KO females than in Crmp4-KO males. GABAAα1, GABAAγ2, GABABR1, and VGAT mRNA expressions were significantly higher in Crmp4-KO females than in WT females and Crmp4-KO males. A significantly higher N-cadherin expression in the OB was observed in Crmp4-KO mice than in WTs, but post-hoc comparison did not show any significant differences among the groups.

In the hippocampus, GluR1 mRNA expression was significantly higher in Crmp4-KO males than in WT males and Crmp4-KO females. Crmp4-KO males also showed higher GluR2 mRNA expression than WT males. Two-way ANOVA revealed that VgluT1 mRNA expression was significantly higher in Crmp4-KO mice than in WTs; however, post-hoc tests did not show significant differences among the groups. GABAAα1 and GABABR1 mRNA expressions were significantly higher in Crmp4-KO females than in Crmp4-KO males. N-cadherin mRNA expression was significantly lower in Crmp4-KO mice than in WT mice, but post-hoc tests did not show significant differences among the groups.

In the cortex, VgluT2 mRNA expression was significantly lower in Crmp4-KO mice than in WT mice, but post-hoc tests did not show significant differences among the groups. GABAAγ2 and GABABR1 mRNA expressions were significantly lower in Crmp4-KO mice than in WT mice. Post-hoc tests revealed that GABAAγ2 mRNA expression was significantly lower in Crmp4-KO females than in WT females and that of GABABR1 was significantly lower in Crmp4-KO males than in WT males. GABABR1 mRNA expression was significantly lower in WT females than in WT males. Ncam1 and N-cadherin mRNA expressions were significantly lower in Crmp4-KO mice than in WT mice of the same sex. Gene expression levels of SERT in the raphe and serotonin receptors (5HT1A, 5HT2A, and 5HT7) and dopamine receptors (D1R and D2R) in the OB, hippocampus, and cortex did not significantly differ between Crmp4-KO and WT mice of either sex (Supplementary Table S4).

Discussion

The association of damaging single-nucleotide variants and small insertion/deletion variations has been identified in a subset of ASD patients using massively parallel DNA sequencing37. In addition, exome sequencing has verified the causative de novo variants in 6–16% of ASD38–41. These methods have revealed hundreds of rare genetic variants that cause various symptoms associated with ASD. However, the relationship between rare ASD-associated variants and the pathogenesis of ASD remains poorly understood. A previous comprehensive study has discovered a de novo missense variant in CRMP4 in an ASD proband12. In the present study, we found a de novo damaging variant in CRMP4 in a boy diagnosed with ASD, and we further revealed that the mutation induces altered CRMP4 function on dendritic branching. In addition, based on our finding of the human CRMP4 mutation, we provide evidence that deficiency of the murine Crmp4 gene and protein results in behavioural and sensory perceptual alterations related to human autistic behaviours in the animal. Surprisingly, most behavioural deficits in Crmp4-KO mice were more evident in males than in females. Moreover, compared with WT mice, Crmp4-KO mice showed significant changes in the expression of genes related to excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission as well as in genes contributing to cell adhesion.

Decreased active interaction is a core behavioural deficit relevant to ASD42. In mouse models, the active interaction of the animal with a stranger is thought to be a core paradigm to test autistic behaviour43. The three-chamber and social interaction tests in our study indicated decreased social behaviour in male Crmp4-KO mice. In addition, the reduced emission of UVs from mouse pups on isolation to unfamiliar clean materials has been regarded as a behavioural alteration related to ASD44,45. We found that Crmp4-KO mice produced significantly decreased emission of UVs on exposure to unfamiliar clean bedding than WT mice. These results indicate that some behavioural characteristics relevant to ASD were observed in Crmp4-KO mice, some of which had a clearly male predominance.

Sensory disorders have also been reported to be considerably related to the core deficits of ASD22. In 2013, sensory differences, hyper- or hypo-reactivity, were added to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ASD. In our study, we examined the responses of pups and adults to four kinds of sensory stimuli using the food exploring, hot plate and UV emission tests under olfactory (familiar and unfamiliar nest odours) and cold stimuli. The food exploring and hot plate tests showed that Crmp4-KO and WT adults have similar olfactory function and pain sensitivity. However, Crmp4-KO pups differently responded on exposure to olfactory and cold stimuli. Crmp4-KO pups, particularly males, could not discriminate well between familiar and unfamiliar beddings. In addition, abnormal thermal sensitivity was found at a low temperature (9 °C, Fig. 6b) in male Crmp4-KO pups.

The mechanism causing these behavioural and sensory alterations in Crmp4-KO mice, most of which had a male dominance, remains uncertain. However, our gene expression analysis may provide a clue. As shown in Table 1, Crmp4 deficiency altered the mRNA expression of eight genes related to neurotransmission among those examined: GluR1, GluR2, VgluT1, VgluT2, GABAα1, GABAAγ2, BAGABR1, and VGAT. Previous studies have indicated the contributions of GluR1 and GluR2 in ASD33,46,47; these receptors are members of the AMPA-type receptor family that mediates fast excitatory transmission. VgluT1 and VgluT2 have an important role in glutamate transportation in the synaptic vesicle membrane. The mRNA expressions of glutamatergic neurotransmission related genes were increased in the OB and hippocampus in Crmp4-KO males, females, or both male and females than in WT mice of the same sex (Table 1). We also observed a female-specific increase in the mRNA expression of genes associated with inhibitory transmission, such as GABAAα1, GABAAγ2, GABABR1, and VGAT in the OB and of GABAAα1 and GABABR1 in the hippocampus of adult Crmp4-KO mice (Table 1). Increased glutamatergic neurotransmission can lead to an increased activity of excitatory neurons. In contrast, increased GABA neurotransmission would lead to suppression of neuronal activity. Therefore, in the OB and hippocampus of males, Crmp4 deletion may possibly give rise to an increased ratio of excitation/inhibition, which has been proposed to be a key pathophysiological mechanism contributing to ASD48,49.

However, in the cortex, GluR1 and GluR2 mRNA expressions were not increased and GABAAγ2 and GABABR1 mRNA expressions were significantly decreased in Crmp4-KO mice than in WT mice. In addition, the number of genes with altered expressions due to Crmp4 deletion differed among brain regions. These results suggest regionally different effects of Crmp4 deletion on neurotransmission.

In contrast, although treatments targeting a specific molecular component of the glutamatergic system are likely to benefit only a subset of the ASD population, glutamatergic medication has been used in the treatment of ASD50, supporting the involvement of the glutamatergic system in ASD pathogenesis. However, Purcell et al. have reported that ASD patients exhibit elevated expression of GluR146, while Ramanathan et al. found hemizygous deletion of GluR2 gene in an ASD patient51. The role of GluRs in ASD pathogenesis still remains controversial. In some mouse models with targeted mutations in candidate genes for ASD, abnormal expression of GluR1 and GluR2 was also reported. Schmeisser et al. have demonstrated that genetic deletion of ProSAP1/Shank2, one of the famous mouse models of ASD, results in an early brain-region-specific upregulation of ionotropic glutamate receptors at the synapse52. A mouse model of Fragile X syndrome is sometimes used in studies of ASD. Pilpel et al. have reported that a mouse model of Fragile X syndrome (Fmr1 KO2) displays a significantly lower AMPA to NMDA ratio than WTs at 2 weeks of post-natal development but not at 6–7 weeks of age53. Combining these data with our present data leads to a hypothesis that the time-, region- and gender-dependent changes in gene expressions associated with glutamatergic as well as GABAergic transmission induced by Crmp4 deletion could be involved in processes underlying the pathogenesis of some features of human ASD.

CRMP4 is a member of the CRMP family of proteins (CRMP1–5) which are thought to regulate cell proliferation, migration, neuronal differentiation and signal transduction through their interaction with tubulin and actin54–56. Our previous proteomics study on the sexually dimorphic nucleus (AVPV) in the hypothalamic area, a region thought to be critical for generating the pre-ovulatory GnRH/LH surge in females, identified CRMP4 as a protein exhibiting sex-based differential expression during sexual differentiation of the nucleus11, although Crmp4 function in the sexual differentiation of AVPV remains unclear. Some studies have shown that CRMP4 negatively regulates axonal growth57–60, while others have shown its positive regulation of axonal elongation61,62. In addition, CRMP4 is involved in dendrite formation18,19,63. In our study, we confirmed that CRMP4 suppresses the length of dendrites and number of dendritic branches (Fig. 2). Real-time qRT-PCR analysis revealed significant changes in Ncam1 and N-cadherin mRNA expressions, two of the factors that play important roles in cell adhesion and dendritic growth36. Furthermore, CRMP4 is known to functionally interact with RhoA58,61, which has significant effects on axon elongation and spine morphogenesis64. NMDA-induced calpain activation leads to degradation of CRMP465, which may contribute to the alteration of spine density66. A regulatory role of CRMP4 has been demonstrated during the migration of neuroblastoma cells through the binding with chondroitin sulfate in the extracellular matrix of the cortical plate67. Interestingly, S541 in CRMP4, which was mutated into Y541 in the de novo variant of our ASD patient, has been reported to be phosphorylated68. Because phosphorylation is critical for functions of CRMPs, the mutation in CRMP4 may impair its suppressive role in dendritic branching, as shown in Fig. 2.

On the other hand, Crmp4 mRNA expression in the three brain regions tested were not significantly different between sexes. This is not surprising because our previous study found that the sex-differential expressions of CRMP4 and Crmp4 mRNA was seen only when the sex differentiation occurs in the sexual dimorphic nucleus of the hypothalamus11. Since the expression of Crmp4 mRNA in adult brain is very weak69, the different effects on gene expression and social behavior between male and female Crmp4-KO mice might be the result of the difference during neural network formation. Collectively, these observations indicate that CRMP4 plays important roles as one of the convergent regulators in neural network formation and that its dysfunction may lead to abnormalities in gene expression resulting in abnormal behaviours in mice. In addition, the regulatory role for CRMP4 in neural network formation are consistent with the hypothesis that CRMP4 disruption might contribute to ASD symptoms.

In summary, we found a damaging de novo missense CRMP4 mutation in a male ASD patient. We also found that Crmp4-KO mice have abnormalities that are relevant to some phenotypes of human ASD. Accumulating evidence from previous and present studies on CRMP4 suggests that a disturbance in the regulatory function of CRMP4 in forming neuronal networks is an important aspect underlying some characteristics of ASD, including sexual differences. Our findings provide CRMP4 as a novel candidate gene contributing to ASD and shed new light on the role of CRMP4 in sex differences.

Methods

Case study of an ASD patient and whole-exome sequencing

Patient A379 and his parents were enrolled in the CORA following voluntary written informed consent as part of a human subjects research protocol approved by the Nationwide Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board as required by 32 CFR 219 of the US Department of Health and Human Services and AFI 40-402 of the US Air Force. The patient (A379 in Fig. 1) is a 16-year-old Caucasian male diagnosed at age 5 years with an ASD. The history of the patient and method for exome sequencing are provided in Supplementary Information.

Animals

WT and Crmp4-KO mice18 were generated by mating Crmp4 +/− heterozygotes backcrossed onto the C57BL/6N background for at least 10 generations. Genotyping of the Crmp4 allele was performed as previously described18. All the mice were weaned on PD21 and were housed in groups of 2–4 per cage, segregated by sex, in a room with a 12 h/12 h light–dark cycle (light on at 7:00 AM, off at 7:00 PM) and the temperature was maintained at 23 ± 1 °C. Food and water were available ad libitum. The plan for the use and care of the animals and methods were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use and Ethical Committee of the University of Tokyo and Toyo University. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Primary cultures of hippocampal cells from WT and CRMP4-KO mice and CRMP4-KO cells transfected with either CRMP4 or CRMP4S540Y expression vector

Primary culture was performed as previously reported19. In this study, to assess the general effects of Crmp4 or Crmp4 S540 expressions on dendritic growth, only male animals were used for primary culture. In addition, we used hippocampal pyramidal neurons because they are routinely used to examine the effects on neurite outgrowth. Crmp4 (pEGFP-Crmp4 vector) and Crmp4 S540Y (pEGFP-Crmp4 S540Y) expression vectors were constructed as described in Supplementary Information.

Either pEGFP-Crmp4, pEGFP-Crmp4 S540Y or pEGFP-N (provided by H. Okado, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science) vector was transfected into the cultured hippocampal cells removed from Crmp4-KO mice using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) on day in vitro 1 (DIV-1). Hippocampal cells were fixed on DIV-3 with 4% paraformaldehyde and then immunocytochemically stained as previously descried19. The total length of dendrites and number of branching points were estimated on MAP2-positive dendrites of each neuron with EGFP labelling.

Behavioural experiments

All the behavioural experiments were performed from 1:00 PM to 5:00 PM in the behaviour-testing room. Mice at PD7 were tested for UVs. The cages containing the mice were transferred to the behaviour-testing room 30 min before commencement of the first trial.

Open-field test

The open-field test was performed as previously described70, with minor modifications. Each mouse (male WT, n = 17; male Crmp4-KO, n = 15; female WT, n = 12; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 14) was placed in the corner of the open-field apparatus (50 × 50 × 32 cm, Muromachi Kikai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) facing the wall. Each subject was given a 20-min test. The total distance travelled (cm), velocity (cm/min) and time (s) spent in the centre (35 × 35 cm, inner square) were determined using the Noldus Ethovision system (Noldus, Leesburg, VA, USA).

Elevated plus maze test

The elevated plus maze test was performed as previously described71, with minor modifications. Each mouse (male WT, n = 11; male Crmp4-KO, n = 10; female WT, n = 9; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 12) was tested on an elevated plus maze. Briefly, a mouse was placed on the central platform facing a close arm and allowed to freely traverse the maze for 10 min. The time spent in each arm and the number of arm entries (70% of mice in an arm) were measured.

Novel object recognition test

The novel object recognition test was performed, as previously described72. Each mouse (male WT, n = 13; male Crmp4-KO, n = 17; female WT, n = 13; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 13) was individually habituated to the open-field box with 10 min of exploration in the absence of objects 24 h before starting the familiarisation phase. The protocols for the novel object recognition test and figures of the objects are provided in Supplementary Fig. S1 and its legend.

Three-chamber test

The three-chamber test was performed as previously described71, with minor modifications. Each tested mouse at 6 weeks of age (male WT, n = 11; male Crmp4-KO, n = 10; female WT, n = 11; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 12) or at 10 weeks of age (male WT, n = 10; male Crmp4-KO, n = 8; female WT, n = 9; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 11) was individually placed in the centre chamber and allowed to freely explore all three chambers for 10 min while movement was video-recorded. The time spent in each chamber and that spent sniffing were measured.

Social interaction test

The social interaction test was performed, as previously described73. Each mouse (male WT, n = 15; male Crmp4-KO, n = 17; female WT, n = 12; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 17) was maintained in social isolation for 1 week by placing one mouse/cage under the same conditions as described above. On the experimental day, after a 10-min habituation to the sound-attenuating chamber, an age-matched, unfamiliar C57BL/6N WT mouse of the same sex and similar body weight (within 5%) was placed in the corner of the cage. The duration of active interaction behaviours such as sniffing, mounting and chasing was measured.

Tube test for social dominance

Thirty WT and Crmp4-KO mice (six males and nine females in each group) were tested, as previously described73. Each pairing was performed twice for a total of 30 matches. The winning percentage was calculated for each group.

Food exploring test

The food exploring test was performed, as previously described74, with minor modifications. Each mouse at 7 weeks of age (male WT, n = 15; male Crmp4-KO, n = 15; female WT, n = 12; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 16) or at 11 weeks of age (male WT, n = 11; male Crmp4-KO, n = 15; female WT, n = 10; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 15) was deprived of food for 18 h before testing, while water was freely available. A piece of a food pellet (0.5 g) was buried beneath clean bedding of about 0.5 cm at the centre of the cage. A mouse was placed in the corner of the cage and the time required to find the food was determined.

Hot plate test

The hot plate test was performed, as previously described75. Each mouse (male WT, n = 21; male Crmp4-KO, n = 16; female WT, n = 26; and female Crmp4-KO, n = 24) was placed on a heating apparatus maintained at 55 °C. The time until the first hind-paw response was determined. The paw response was defined as a paw lick, a foot shake or jumping. A cutoff time of 60 s was used.

Measurement of UVs emitted by mouse pups under different sensory stimuli

UV assessment of WT (male, n = 11; female, n = 12) and Crmp4-KO (male, n = 14; female, n = 16) littermates at PD7 was performed under familiar or unfamiliar odour, as previously reported27.

Next, we examined UVs emitted by WT and Crmp4-KO pups in response to thermal change. We used WT and Crmp4-KO pups of both sexes and isolated them at RT, 19 °C or 9 °C. Each pup (male WT, n = 8; female WT, n = 13; male Crmp4-KO, n = 8; female Crmp4-KO, n = 6) was isolated from the nest in a clean plastic case at RT. Other pups (WT male, n = 24; WT female, n = 26; male Crmp4-KO, n = 29; female Crmp4-KO, n = 26) were isolated from the nest in a clean glass beaker maintained at 19 °C or 9 °C. In each test, UVs were recorded for 5 min.

Real-time qRT-PCR

Complete description is provided in Supplementary Information.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For statistical comparisons, one-, two- or three-way ANOVA followed by Fischer’s protected least significant difference (PLSD) test, Bonferroni correction, Sidak correction, and Tukey HSD test were conducted. The binomial test was used for the tube test. In all analyses, p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. For direct pairwise comparisons, Student’s t-test was applied.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful for the contributions of all participants and their families. The authors would like to thank Dr. David Cunningham for his kind support for making the genome sequencing figure. The authors would also like to thank Dr. K. Ikeda and Dr. M. Tanaka (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science) for their technical advice on the social interaction test for mice. We thank Dr. H. Okado (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science) for providing the pEGFP-N vector. This work was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 25430042 and 16K07034 to R. Ohtani-Kaneko, Grant Number 25-7107 to Atsuhiro Tsutiya, and Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research in a Priority Area from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture to Yoshio Goshima (17082006). This work was also partly supported by The INOUE ENRYO Memorial Grant (TOYO University) to R. Ohtani-Kaneko. Supports for the human patient sequencing and CORA registry were provided by the United States Air Force Department of Defence (FA7014-09-2-0004 and FA8650-12-2-6359) to Gail E. Herman.

Author Contributions

A.T. and R.O.K. designed the mouse research and interpreted data. A.T. and Y.N. performed experiments using mice and analysed the data. E.H.K. and G.E.H. carried out clinical human studies with patients. B.A.K., D.C., P.W., and G.E.H. performed gene sequencing of patients with ASD and interpreted the sequencing data. M.N. and Y.G. jointly directed the project. A.T., G.E.H., and R.O.K. wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-16782-8.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fombonne E. Epidemiological surveys of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders: An update. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33:365–382. doi: 10.1023/A:1025054610557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen, D. L. et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ65, 10.15585/mmwr.ss6503a1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.O’Roak BJ, et al. Recurrent de novo mutations implicate novel genes underlying simplex autism risk. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5595. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato D, et al. SHANK1 Deletions in Males with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:879–887. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu VW, Sarachana T, Sherrard RM, Kocher KM. Investigation of sex differences in the expression of RORA and its transcriptional targets in the brain as a potential contributor to the sex bias in autism. Mol Autism. 2015;6:7. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KC, et al. MeCP2 Modulates Sex Differences in the Postsynaptic Development of the Valproate Animal Model of Autism. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:40–56. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8987-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baron-Cohen S, et al. Why are autism spectrum conditions more prevalent in males? PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumberg SJ, et al. Changes in prevalence of parent-reported autism spectrum disorder in school-aged U. S. children: 2007 to 2011–2012. Natl Health Stat Report. 2013;65:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Idring S, et al. Changes in prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in 2001–2011: findings from the Stockholm youth cohort. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:1766–1773. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2336-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwakura T, et al. Collapsin response mediator protein 4 affects the number of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive neurons in the sexually dimorphic nucleus in female mice. Dev Neurobiol. 2013;73:502–517. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iossifov I, et al. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2014;515:216–221. doi: 10.1038/nature13908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith RM, Banks W, Hansen E, Sadee W, Herman GE. Family-based clinical associations and functional characterization of the serotonin 2A receptor gene (HTR2A) in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2014;7:459–467. doi: 10.1002/aur.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davydov EV, et al. Identifying a high fraction of the human genome to be under selective constraint using GERP++ PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:e1001025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adzhubei IA, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong C, et al. Comparison and integration of deleteriousness prediction methods for nonsynonymous SNVs in whole exome sequencing studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:2125–2137. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niisato E, et al. CRMP4 suppresses apical dendrite bifurcation of CA1 pyramidal neurons in the mouse hippocampus. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72:1447–1457. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsutiya A, et al. Deletion of collapsin response mediator protein 4 results in abnormal layer thickness and elongation of mitral cell apical dendrites in the neonatal olfactory bulb. J Anat. 2016;228:792–804. doi: 10.1111/joa.12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montani C, et al. The X-Linked Intellectual Disability Protein IL1RAPL1 Regulates Dendrite Complexity. J Neurosci. 2017;37:6606–6627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3775-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng N, Alshammari F, Hughes E, Khanbabaei M, Rho JM. Dendritic overgrowth and elevated ERK signaling during neonatal development in a mouse model of autism. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyd BA, et al. Sensory features and repetitive behaviors in children with autism and developmental delays. Autism Res. 2010;3:78–87. doi: 10.1002/aur.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm01. (2013).

- 24.Scattoni ML, Crawley J, Ricceri L. Ultrasonic vocalizations: a tool for behavioural phenotyping of mouse models of neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fish EW, Sekinda M, Ferrari PF, Dirks A, Miczek KA. Distress vocalizations in maternally separated mouse pups: modulation via 5-HT(1A), 5-HT(1B) and GABA(A) receptors. Psychopharmacology. 2000;149:277–285. doi: 10.1007/s002130000370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemasson M, Delbé C, Gheusi G, Vincent JD, Lledo PM. Use of ultrasonic vocalizations to assess olfactory detection in mouse pups treated with 3-methylindole. Behav Process. 2005;68:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsutiya A, Nishihara M, Goshima Y, Ohtani-Kaneko R. Mouse pups lacking collapsin response mediator protein 4 (CRMP4) manifest impaired olfactory function and hyperactivity in the olfactory bulb. Eur J Neurosci. 2015;42:2335–2345. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moles A, Kieffer BL, D’Amato FR. Deficit in attachment behavior in mice lacking the mu-opioid receptor gene. Science. 2004;304:1983–1986. doi: 10.1126/science.1095943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wöhr M. Effect of social odor context on the emission of isolation-induced ultrasonic vocalizations in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse model for autism. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:73. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duerden EG, et al. Decreased sensitivity to thermal stimuli in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: relation to symptomatology and cognitive ability. J Pain. 2015;16:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yasuda Y, et al. Sensory cognitive abnormalities of pain in autism spectrum disorder: a case-control study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2016;15:8. doi: 10.1186/s12991-016-0095-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Krom M, et al. A common variant in DRD3 receptor is associated with autism spectrum disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uzunova G, Hollander E, Shepherd J. The role of ionotropic glutamate receptors in childhood neurodevelopmental disorders: autism spectrum disorders and fragile x syndrome. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2014;12:71–98. doi: 10.2174/1570159X113116660046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pizzarelli R, Cherubini E. Alterations of GABAergic signaling in autism spectrum disorders. Neural Plast. 2011;2011:297153. doi: 10.1155/2011/297153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veenstra-VanderWeele J, et al. Autism gene variant causes hyperserotonemia, serotonin receptor hypersensitivity, social impairment and repetitive behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5469–5474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112345109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansen SM, Berezin V, Bock E. Signaling mechanisms of neurite outgrowth induced by the cell adhesion molecules NCAM and N-cadherin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3809–3821. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8290-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dong S, et al. De novo insertions and deletions of predominantly paternal origin are associated with autism spectrum disorder. Cell Rep. 2014;9:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iossifov I, et al. De novo Gene disruptions in children on the autistic spectrum. Neuron. 2012;74:285–299. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neale BM, et al. Patterns and rates of exonic de novo mutations in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2012;485:242–245. doi: 10.1038/nature11011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Roak BJ, et al. Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature. 2012;485:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature10989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanders SJ, et al. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature. 2012;485:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Happe F, Ronald A. The ‘fractionable autism triad’: a review of evidence from behavioural, genetic, cognitive and neural research. Neuropsychol Rev. 2008;18:287–304. doi: 10.1007/s11065-008-9076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silverman JL, Yang M, Lord C, Crawley JN. Behavioural phenotyping assays for mouse models of autism. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:490–502. doi: 10.1038/nrn2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mosienko V, Beis D, Alenina N, Wöhr M. Reduced isolation-induced pup ultrasonic communication in mouse pups lacking brain serotonin. Mol Autism. 2015;6:13. doi: 10.1186/s13229-015-0003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wöhr M, Roullet FI, Hung AY, Sheng M, Crawley JN. Communication impairments in mice lacking Shank1: reduced levels of ultrasonic vocalizations and scent marking behavior. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Purcell AE, Jeon OH, Zimmerman AW, Blue ME, Pevsner J. Postmortem brain abnormalities of the glutamate neurotransmitter system in autism. Neurology. 2001;57:1618–1628. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.9.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Essa MM, Braidy N, Vijayan KR, Subash S, Guillemin GJ. Excitotoxicity in the pathogenesis of autism. Neurotox Res. 2013;23:393–400. doi: 10.1007/s12640-012-9354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gatto CL, Broadie K. Genetic controls balancing excitatory and inhibitory synaptogenesis in neurodevelopmental disorder models. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2010;2:4. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rubenstein JL. Three hypotheses for developmental defects that may underlie some forms of autism spectrum disorder. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:118–123. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328336eb13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fung LK, Hardan AY. Developing Medications Targeting Glutamatergic Dysfunction in Autism: Progress to Date. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:453–463. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramanathan S, et al. A case of autism with an interstitial deletion on 4q leading to hemizygosity for genes encoding for glutamine and glycine neurotransmitter receptor subunits (AMPA2, GLRA3, GLRB) and neuropeptide receptors NPY1R, NPY5R. BMC Med Genet. 2004;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmeisser MJ, et al. Autistic-like behaviours and hyperactivity in mice lacking ProSAP1/Shank2. Nature. 2012;486:256–260. doi: 10.1038/nature11015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pilpel Y, et al. Synaptic ionotropic glutamate receptors and plasticity are developmentally altered in the CA1 field of Fmr1 knockout mice. J Physiol. 2009;587:787–804. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fukata Y, et al. CRMP-2 binds to tubulin heterodimers to promote microtubule assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:583–591. doi: 10.1038/ncb825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Charrier E, et al. Collapsin response mediator proteins (CRMPs): involvement in nervous system development and adult neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Neurobiol. 2003;28:51–64. doi: 10.1385/MN:28:1:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosslenbroich V, et al. Collapsin response mediator protein-4 regulates F-actin bundling. Exp Cell Res. 2005;310:434–444. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alabed YZ, Pool M, Ong Tone S, Fournier AE. Identification of CRMP4 as a convergent regulator of axon outgrowth inhibition. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1702–1711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5055-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alabed YZ, Pool M, Ong Tone S, Sutherland C, Fournier AE. GSK3 beta regulates myelin-dependent axon outgrowth inhibition through CRMP4. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5635–5643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6154-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagai J, et al. Crmp4 deletion promotes recovery from spinal cord injury by neuroprotection and limited scar formation. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8269. doi: 10.1038/srep08269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nagai J, Takaya R, Piao W, Goshima Y, Ohshima T. Deletion of Crmp4 attenuates CSPG-induced inhibition of axonal growth and induces nociceptive recovery after spinal cord injury. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2016;74:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khazaei MR, et al. Collapsin response mediator protein 4 regulates growth cone dynamics through the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:30133–30143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.570440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tan M, et al. CRMP4 and CRMP2 Interact to Coordinate Cytoskeleton Dynamics, Regulating Growth Cone Development and Axon Elongation. Neural Plast. 2015;2015:947423. doi: 10.1155/2015/947423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cha C, et al. CRMP4 regulates dendritic growth and maturation via the interaction with actin cytoskeleton in cultured hippocampal neurons. Brain Res Bull. 2016;124:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Woolfrey KM, Srivastava DP. Control of Dendritic Spine Morphological and Functional Plasticity by Small GTPases. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:3025948. doi: 10.1155/2016/3025948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kowara R, Ménard M, Brown L, Chakravathy B. Co-localization and interaction of DPYSL3 and GAP43 in primary cortical neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363:190–193. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andres AL, et al. NMDA receptor activation and calpain contribute to disruption of dendritic spines by the stress neuropeptide CRH. J Neurosci. 2013;33:16945–16960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1445-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Franken S, et al. Collapsin response mediator proteins of neonatal rat brain interact with chondroitin sulfate. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3241–3450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mertins P, et al. Proteogenomics connects somatic mutations to signalling in breast cancer. Nature. 2016;534:55–62. doi: 10.1038/nature18003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsutiya A, Ohtani-Kaneko R. Postnatal alteration of collapsin response mediator protein 4 mRNA expression in the mouse brain. J Anat. 2012;221:341–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Umemori J, et al. ENU-mutagenesis mice with a non-synonymous mutation in Grin1 exhibit abnormal anxiety-like behaviors, impaired fear memory, and decreased acoustic startle response. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:203. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weidner KL, Buenaventura DF, Chadman KK. Mice over-expressing BDNF in forebrain neurons develop an altered behavioral phenotype with age. Behav Brain Res. 2014;268:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Isono T, et al. Amyloid-β25–35 induces impairment of cognitive function and long-term potentiation through phosphorylation of collapsin response mediator protein 2. Neurosci Recearch. 2013;77:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sato A, et al. Rapamycin reverses impaired social interaction in mouse models of tuberous sclerosis complex. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1292. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mitsui S, et al. A mental retardation gene, motopsin/neurotrypsin/prss12, modulates hippocampal function and social interaction. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:2368–2378. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hikida T, Kitabatake Y, Pastan I, Nakanishi S. Acetylcholine enhancement in the nucleus accumbens prevents addictive behaviors of cocaine and morphine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6169–6173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631749100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).