Abstract

Background

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) and Non-tuberculosis Mycobacterium (NTM) infections differ clinically, making rapid identification and drug susceptibility testing (DST) very critical for infection control and drug therapy. This study aims to use World Health Organization (WHO) approved line probe assay (LPA) to differentiate mycobacterial isolates obtained from tuberculosis (TB) prevalence survey in Ghana and to determine their drug resistance patterns.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted whereby a total of 361 mycobacterial isolates were differentiated and their drug resistance patterns determined using GenoType Mycobacterium Assays: MTBC and CM/AS for differentiating MTBC and NTM as well MTBDRplus and NTM-DR for DST of MTBC and NTM respectively.

Results

Out of 361 isolates, 165 (45.7%) MTBC and 120 (33.2%) NTM (made up of 14 different species) were identified to the species levels whiles 76 (21.1%) could not be completely identified. The MTBC comprised 161 (97.6%) Mycobacterium tuberculosis and 4 (2.4%) Mycobacterium africanum. Isoniazid and rifampicin monoresistant MTBC isolates were 18/165 (10.9%) and 2/165(1.2%) respectively whiles 11/165 (6.7%) were resistant to both drugs. Majority 42/120 (35%) of NTM were M. fortuitum. DST of 28 M. avium complex and 8 M. abscessus complex species revealed that all were susceptible to macrolides (clarithromycin, azithromycin) and aminoglycosides (kanamycin, amikacin, and gentamicin).

Conclusion

Our research signifies an important contribution to TB control in terms of knowledge of the types of mycobacterium species circulating and their drug resistance patterns in Ghana.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-017-2853-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Prevalence survey, Ghana, Line probe assay, Drug resistance, MTBDRplus, NTM-DR

Background

Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for about 28% of the estimated 9.6 million of all notified tuberculosis (TB) cases in 2014. The TB menace is further aggravated by the emergence of drug resistant strains which is a setback in TB control efforts. In Ghana, TB still poses a major public health concern with a total of 14,668 cases reported in 2014 [1]. The Ghana National TB prevalence survey was conducted from March – December, 2013 to obtain useful estimates of TB prevalence within the time period. The adjusted prevalence of smear positive pulmonary TB and bacteriologically confirmed TB among adults aged 15 years and above were 111 (95% CI 76–145) per 100,000 population and 356 (95% CI 288–425) per 100,000 population respectively (personal communication with the programme manager for the National TB Control Programme, Ghana, unpublished data). Isolation of many Nontuberculous Mycobacterium (NTM) during the survey necessitated further investigations. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) and Non-tuberculosis Mycobacterium (NTM) infections differ clinically, making rapid identification and drug susceptibility testing (DST) very critical for infection control and drug therapy [2]. The use of simple, rapid and efficient tools for mycobacterial differentiation and DST such as World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed line probe assay (LPA) is much needed especially in developing countries with high TB burden and preponderance of environmental mycobacteria [3]. One of such commercially available LPA is the GenoType Mycobacterium Assays (Hain Lifescience, Nehren, Germany) which have demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in many studies for differentiating between species of MTBC and NTM as well as determining the presence of mutations in genes associated with drug resistance [4–6]. This study therefore sought to use LPA to differentiate mycobacterial isolates and thereafter determine their resistance to anti-mycobacterial drugs. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study in Ghana to genotype and determine DST patterns of both MTBC and NTM strains obtained from a nationwide TB prevalence survey.

Methods

Study design and population

This study was a follow-up to the National TB prevalence survey conducted from March–December, 2013 to determine the actual burden of TB in adult population (≥ 15 years) in Ghana. The survey was cross sectional and community-based in 98 clusters in two strata (urban, rural) which were selected by stratified multistage cluster sampling based on probability proportional to size. All participants were screened using an interview about symptoms and chest X-ray as recommended by WHO [7]. A total of 8298 participants were eligible for sputum examination, of whom 8126 (98%) submitted at least one sputum specimen and 7706 (93%) submitted two sputum specimens. This current study was done using culture positive mycobacterial isolates identified from the prevalence survey. Additional file 1 represents the map of Ghana showing the study sites (clusters).

Laboratory procedures

All laboratory investigations were carried out in a Pathogen Level 3 (P3) Laboratory.

Culture and identification

Equal volumes of commercially available Sodium hydroxide-N-acetyl L-cysteine (NaOH-NALC)-Mycoprep (BD Diagnostic System, Sparks, MD, USA) was added to sputum in a 50 ml centrifuge tube. The mixture was vortexed and allowed to stand for 15 min at room temperature. Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) [pH = 6.8] was added up to the 50 ml mark and centrifuged at 3000 g at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant was discarded to obtain sediment which was reconstituted with 2 ml of PBS (pH = 6.8). An aliquot (0.5 ml) of reconstituted sediment was inoculated into two tubes of Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT) and incubated in the BACTEC MGIT 960 (BD Diagnostic System, Sparks, MD, USA) for a maximum of 42 days. Once a tube flagged positive in MGIT, smear was prepared and Ziehl Neelsen (ZN) stained for the presence or absence of acid fast bacilli (AFB). Additionally, a portion of the positive culture was inoculated onto blood agar plates by streaking to check for contamination. All the positive mycobacterial isolates obtained were broadly identified as Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) and Non-tuberculosis mycobacterium (NTM) using BD MGIT™ TBc Identification Test Kit (BD Diagnostic System, Sparks, MD). The test detects the MPT64 antigen which is highly specific for MTBC. The test and interpretation of the results was done according to manufacturer’s instructions [8]. All negative test samples were suspected NTM and confirmed using GenoType Mycobacterium CM and GenoType Mycobacterium AS (Hain Lifescience Nehren, Germany).

Line Probe Assay (LPA)

The LPA procedure consisting of DNA extraction, master mix preparation, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and reverse hybridization were performed in separate rooms. All the assays (GenoType MTBC; GenoType Mycobacterium CM; GenoType Mycobacterium AS; GenoType MTBDRplus, GenoType NTM-DR) were run according to manufacturer’s instructions [9–13]. Quality control of all the tests were ensured by using H37Rv strain and nuclease free water as positive and negative control markers respectively.

DNA extraction

The boiling (heat killing) method of DNA extraction was used. About 0.5 ml of thawed suspension of isolates was dispensed into a 1.5 ml screw capped micro centrifuge tubes. The tubes were placed in a heating block at 90 °C for about 1 h to disrupt the cell wall and release DNA into solution. The solution was allowed to stand for about 15 min without any form of shaking in order that the disrupted cells will settle down in the tubes. Next, the supernatant containing the mycobacterial DNA was carefully transferred into different tubes using Pasteur pippette and kept at −20 °C until used for PCR.

Multiplex amplification with biotinylated primers

Briefly, 10 μl of Amplification Mix A (AM-A) consisting of 5 μl 10× buffer, 2 μl MgCl2, 3 μl of molecular grade water and 0.2 μl (1 U) Taq DNA polymerase was mixed with 35 μl of Amplification Mix B (AM-B) made up of nucleotides, biotinylated primers and dye. Then, 5 μl of extracted DNA sample was added to the master-mix in another room. PCR amplification was done with the thermocycler set at the following cycling conditions: one cycle at 95 °C for 15 min, followed by ten cycles at 95 °C and 58 °C for 30 s and 2 min respectively. This was followed by another round of 20 cycles at 95 °C, 53 °C and 70 °C for 25, 40 and 40 s respectively before a final single cycle at 70 °C for 8 min.

Reverse hybridization

Hybridization was carried out with the GT-Blot 48® automated hybridizer (Hain Lifescience Nehren, Germany) in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions. Pre-heated hybridization and stringent buffers, diluted conjugate and substrate solutions, rinsing and sterile distilled water were placed into their respective colour-coded slots in the GT-Blot 48®. Then suction heads were placed into corresponding colour-coded solutions. Equal volumes (20 μl) of denaturing reagent and amplicons were mixed together in wells of a tray placed in the GT-Blot 48® and allowed to stand for 5 min at 25 °C. After denaturation, the test strips with sample identification numbers written on them were placed into corresponding wells. The automated process of dispensing and aspirating various solutions was set in a sequential order: hybridization, stringent wash, rinsing, conjugate, rinsing, sterile distilled water, substrate, sterile distilled water. The strips were then dried using the heating systems in the GT-Blot 48®.

Evaluation and interpretation of results

The fully dried strips were scanned using GenoScan® (Hain Lifescience, Nehren, Germany) which generated an automated read-out of the band patterns. The strips were pasted on evaluation sheets included in the kit. The final results on the read-out were verified manually with the naked eye.

Statistical analysis

All the data collected were entered into Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, USA) for analysis. Results were presented in tables and graphs showing frequencies and percentages. Fisher’s exact test was applied to determine association between socio-demographic characteristics, with p ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The main study (Assessing tuberculosis disease prevalence in Ghana through a population based survey) obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR) [FWA 00001824; IRB 00001276].

Results

Background characteristics

Out of 361 culture positive mycobacterial isolates, 159 (44%) and 202 (56%) were obtained from male and female participants respectively. Based on the BD MGIT™ TBc Identification Test Kit, 165 (45.7%) were identified as MTBC whiles 196 (54.3%) were suspected to be NTM. The mean age of culture positive participants were 47.4 years and 45.9 years for MTBC and NTM respectively. Background characteristics of participants from whom mycobacterial isolates were obtained have been summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants from whom mycobacterial isolates used in the study were obtained (N = 361)

| Characteristic | MTBC | p value | NTM | p value | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | N (%) | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 91 (55.2) | 0.0001 | 68 (34.7) | 159 (44.0) | |

| Female | 74 (44.8) | 128 (65.3) | 0.0001 | 202 (56.0) | |

| Age group | |||||

| 15–24 | 25 (15.2) | 33 (16.8) | 58 (16.1) | ||

| 25–34 | 22 (13.3) | 35 (17.9) | 57 (15.8) | ||

| 35–44 | 22 (13.3) | 31 (15.8) | 53 (14.7) | ||

| 45–54 | 31 (18.8) | 22 (11.2) | 53 (14.7) | ||

| 55–64 | 23 (13.9) | 20 (10.2) | 43 (11.9) | ||

| 65+ | 42 (25.5) | 0.63 | 55 (28.1) | 0.63 | 97 (26.8) |

| TB Historya | |||||

| Yes | 6 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.7) | ||

| No | 159 (96.4) | 196 (100) | 355(98.3) | ||

MTBC Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, NTM Non-tuberculous mycobacterium

aParticipants who have been diagnosed with TB and treated prior to the prevalence survey

Differentiation of MTBC (GenoType MTBC)

Out of 165 MTBC isolates differentiated, 161 (97.6%) were identified as M. tuberculosis while 4 (2.4%) were M. africanum. Other members of MTBC such as M. bovis and M. microti that has been reported to cause disease in humans were not identified (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of MTBC species differentiated by GenoType MTBC Assay (N = 165)

| MTBC species | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| M. tuberculosis | 161 | 97.6 |

| M. africanum | 4 | 2.4 |

| M. bovis | 0 | 0.0 |

| M. microti | 0 | 0.0 |

MTBC Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, M. tuberculosis Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. africanum Mycobacterium africanum, M. bovis Mycobacterium bovis, M. microti Mycobacterium microti

Drug susceptibility testing of MTBC (GenoType MTBDRplus)

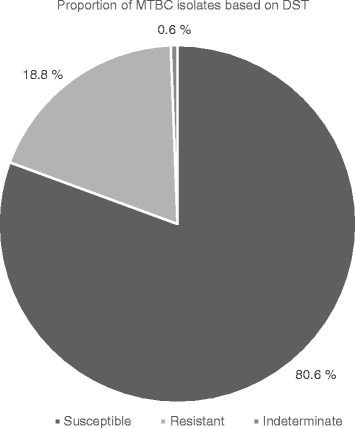

Out of 165 MTBC isolates, 133 (80.6%) were susceptible to both isoniazid (INH) and rifampicin (RIF), 31 (18.8%) were resistant to either INH or RIF while the DST status of the remaining 1 (0.6%) could not be determined (assay yielded an indeterminate result) (Fig. 1). The resistance pattern was 18/165 (10.9%), 2/165 (1.2%) and 11/165 (6.7%) for INH monoresistance, RIF monoresistance and multi-drug resistance-MDR (resistant to both INH and RIF) respectively. One out of two RIF monoresistant isolates had mutations in codon 530–533 resulting in the absence of wild type band (WT8) without the presence of the corresponding mutation band whiles the other showed no mutation in the wild type but MUT 3 (S531 L) mutation (Table 3). For INH monoresistant isolates, mutations in katG MUT1 (S315 T1)-only was the most frequent, making up 14/18 (77.8%) while the remaining 4/18 (22.2%) had mutations in inhA MUT1 (C15T) with the absence of corresponding WT1 (−15/−16). None of the INH monoresistant isolates had mutations in both katG and inhA. The most frequent mutations found in MDR isolates were D516V [6/11 (54.5%)], S315 T1 [10/11 (90.9%)] and T8C [6/11 (54.5%)] in the rpoB, katG and inhA respectively. Other mutations in rpoB included S531 L 1/11 (9.1%) and H526Y 3/11(27.3%) (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Drug resistance patterns of MTBC isolates (N = 165). Susceptible: isolates that are susceptible to both isoniazid and rifampicin. Resistant: isolates that are resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampicin. Indeterminate: isolate whose resistance profile to isoniazid or rifampicin could not be determined by the GenoType MTBDRplus

Table 3.

Specific gene mutations in resistant strains

| Gene locus | Band | Gene region/mutation | aRIF monoresistant | bINH monoresistant | cMDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpoB | |||||

| WT1 | 506–509 | ||||

| WT2 | 510–513 | ||||

| WT3 | 513–517 | d1 | |||

| WT4 | 516–519 | ||||

| WT5 | 518–522 | ||||

| WT6 | 521–525 | ||||

| WT7 | 526–529 | d3 | |||

| WT8 | 530–533 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MUT1 | D516V | 6 | |||

| MUT2A | H526Y | d3 | |||

| MUT2B | H526D | ||||

| MUT3 | S531 L | 1 | 1 | ||

| katG | |||||

| WT | 315 | d11 | d4 | ||

| MUT1 | S315 T1 | 14 | 10 | ||

| MUT2 | S315 T2 | ||||

| inhA | |||||

| WT1 | −15/−16 | d4 | d1 | ||

| WT2 | −8 | d1 | |||

| MUT1 | C15T | d4 | d1 | ||

| MUT2 | A16G | ||||

| MUT3A | T8C | 6 | |||

| MUT3B | T8A |

WT wild type band, MUT mutant band, RIF rifampicin, INH isoniazid, MDR multi-drug resistance

aIsolates with mutation(s) in the rpoB gene and none in the inhApro or katG gene

bIsolates with mutation(s) in the inhApro region and/or in the katG gene, with no mutation in the rpoB gene

cIsolates with mutations in the rpoB gene and inhApro and/or katG gene

dNumber of isolates that had presence of mutation band and the absence of corresponding wild type band

Differentiation of NTM (GenoType Mycobacterium CM/GenoType Mycobacterium AS)

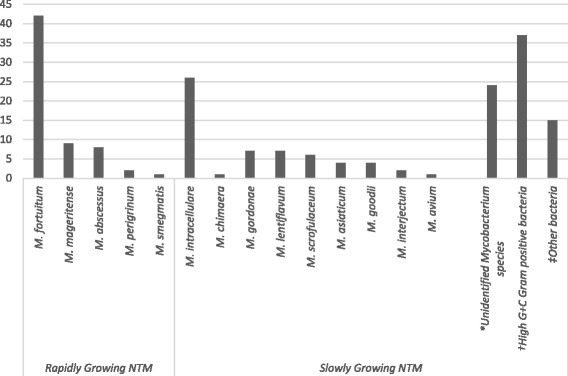

Out of 196 isolates suspected to be NTM, 120 (61.2%) were identified completely to the species level. Among these were M. fortuitum 42 (21.4%), M. intracellulare/ M. chimaera 27 (13.8%), M. mageritense 9 (4.6%), M. abscessus 8 (4.1%), M. gordonae 7 (3.6%), M. lentiflavum 7 (3.6%), M. scrofulaceum 6 (3.1%), M. asiaticum 4 (2.0%), M. goodii 4 (2.0%), M. interjectum 2 (1.0%), M. perigrinum 2 (1.0%), M. avium 1 (0.5%) and M. smegmatis 1 (0.5%). The remaining 76 (38.8%) could not be identified completely using both GenoType CM and GenoType AS. Based on individual band pattern and the use of interpretation chart from the kit manufacturer, these isolates were only identified as Mycobacterium species 24 (12.2%) and High G + C Gram positive bacterium 37 (18.9%) whiles the remaining 15 (7.7%) did not correspond to any of the band patterns described in the interpretation chart (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Identification of species among suspected NTM isolates. M. fortuitum = Mycobacterium fortuitum; M. mageritense = Mycobacterium mageritense; M. abscessus = Mycobacterium abscessus; M. perigrinum = Mycobacterium perigrinum; M. smegmatis = Mycobacterium smegmatis; M. intracellulare = Mycobacterium intracellulare; M. chimaera = Mycobacterium chimaera; M. gordonae = Mycobacterium gordonae; M. lentiflavum = Mycobacterium lentiflavum; M. scrofulaceum = Mycobacterium scrofulaceum; M. asiaticum = Mycobacterium asiaticum; M. goodii = Mycobacterium goodii; M. interjectum = Mycobacterium interjectum; M. avium = Mycobacterium avium; N = number of isolates tested. *Mycobacterium species that could not be identified to the species level. †Members of a group of gram-positive bacterium with high guanine and cytosine content. ‡Group of bacteria that were neither mycobacteria nor high G + C gram-positive bacteria according to assay kit manufacturer’s instructions

Drug susceptibility testing of NTM (GenoType NTM-DR)

Thirty six NTM isolates comprising M. avium complex (M. avium-1; M. intracellulare/ M.chimaera-27) and M. abscessus complex (M. abscessus subsp. abscessus − 2; M. abscessus subsp. massiliense-6) species were susceptible to both macrolides (clarithromycin, azithromycin) and aminoglycosides (kanamycin, amikacin, gentamicin) when DST was performed (Table 4).

Table 4.

Gene mutations in NTM species

| Species/Subspecies | erm(41)a | rrld | rrse | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C28b | T28c | WT | MUT | WT | MUT | |

| M. avium | 1 | 1 | ||||

| M.intracellulare | 26 | 26 | ||||

| M. chimaera | 1 | 1 | ||||

| M. abscessus subsp. abscessus | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| M. abscessus subsp. massiliense | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||

| M. abscessus subsp. bolletti | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note: The probes erm(41) C28 and erm(41) T28 are only relevant for M. abscessus subsp. abscessus and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii, but not for M. abscessus subsp. massiliense. Due to deletions in the erm(41) gene of M. abscessus subsp. massiliense the gene is nonfunctional, leading to macrolide sensitivity in spite of a developed erm(41) T28 band (except for strains with an additional rrl mutation)

WT wild type probe comprises the most important resistance region of the rrl and rrs genes, MUT mutation probes detect the most common resistance-mediating mutations in rrl and rrs genes

aThe erm(41) gene is examined for detection of resistance to macrolides (Clarithromycin or azithromycin) and is only present in members of the M. abscessus complex

bThe erm(41) C28 probe detects a genotype that carries a C at position 28 of the erm(41) gene. When the erm(41) C28 probe stains positive, this indicates that the tested strain is sensitive to macrolides (except for strains with an additional rrl mutation)

cThe erm(41) T28 probe detects a genotype that carries a T instead of a C at position 28 of the erm(41) gene. When the erm(41) T28 probe stains positive, this indicates that the tested strain is resistant to macrolides

dThe rrl gene is examined for detection of resistance to macrolides (clarithromycin or azithromycin)

eThe rrs gene is examined for detection of resistance to aminoglycosides (kanamycin, amikacin, gentamicin)

Discussion

This study primarily set out to differentiate species of mycobacterial isolates obtained from TB prevalence survey in Ghana and to determine their resistance to some antimycobacterial drugs using commercially available LPA, the GenoType Mycobacterium Assays (Hain Life sciences, Nehren, Germany). The background data shows that culture positive MTBC isolates were higher in male participants 91 (55.2%) than females 74 (44.8%) [p < 0.001] which is consistent with reports from other studies [1, 14, 15]. Unlike MTBC, more isolates from females than males were identified as NTM which is consistent with report by Limo et al. [16]. A vast majority of MTBC isolates were identified as M. tuberculosis with very few M. africanum. This finding agrees with reports from many parts of the world [1, 14, 17]. The absence of M. bovis among isolates especially those collected from the northern and upper regions was unexpected since consumption of raw milk and pastoral activities are very common in these areas. Getahun and colleagues reported similar findings from their study in Ethiopia [18]. Determining drug resistance profile of mycobacterial isolates is very critical for effective management of the disease they cause. As expected, over 80% isolates were susceptible to both isoniazid and rifampicin because of the community-based study population from whom these isolates were obtained. Prevalence of drug resistance has been reported to be relatively low in community-based studies compared to health facility-based studies. In this study, INH monoresistance (10.9%) was relatively higher than RIF monoresistance (1.2%) which is consistent with general observation although the reverse has been reported from a study in India where out of 279 smear positive samples, 29 (10.4%) and 62 (22.2%) showed INH monoresistance and RIF monoresistance respectively [19]. Eleven out of 165 (6.7%) MTBC isolates were resistant to both INH and RIF, and thus met the definition of MDR-TB, a potential threat to public health considering the study population involved. However, taking into account the small sample size (N = 165) involved, this finding could not be generalized. An MDR rate of 2.2–2.5% have been reported in previous studies in Ghana [6, 20, 21]. Recently, WHO recommended that rifampicin resistant TB (RR-TB) patients should be given the same treatment regimen as MDR-TB [1]. Common mutations associated with RIF rpoB (D516V, H526Y and S531 L) and INH katG (S315 T) resistance found in our study compares with what exists in other settings [22–24]. In this study, more than half (61%) of the isolates suspected to be NTM were identified to the species level although other studies have reported as high as over 80% species level identification of NTM using GenoType Mycobacterium CM and GenoType Mycobacterium AS [25, 26]. The remaining isolates which were identified only as Mycobacteria species and High G + C Gram positive bacteria as well as those whose band pattern did not correspond to the interpretation chart could be identified through sequencing. NTM-DR determines M. avium complex and M. abscessus complex resistance to macrolides and aminoglycosides. In addition, the assay enables differentiation between M. intracellulare and M. chimaera as well as identification of subspecies of M. abscessus. Infections caused by these NTM are difficult to treat and the various species and subspecies within the complexes differ in drug resistance and treatment outcomes [27]. Our study had some limitations. Firstly, the lack of phenotypic testing to compare with the molecular testing used in this study. Secondly, our inability to test resistance to the other first line drugs as well as second line drugs. Lastly, though some of the most pathogenic NTM were identified by the kit, some could still not be completely identified to the species level.

Conclusions

Our study showed that the predominant mycobacterium species causing TB in Ghana is M. tuberculosis. Resistance against isoniazid and rifampicin are commonly associated with mutations in the katG (Ser315Thr) and rpoB (Asp516Val) respectively. Diverse species of NTM including M. avium complex and M. abscessus complex were identified. Besides, all species and subspecies of M. avium complex and M. abscessus complex respectively were susceptible to macrolides (clarithromycin, azithromycin) and aminoglycosides (kanamycin, amikacin and gentamicin). Our research signifies an important contribution to TB control in terms of knowledge of the types of mycobacterium species circulating and drug resistance patterns in Ghana.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all study participants as well as staff involved in the TB prevalence survey. Samuel Ofori Addo was supported by a WACCBIP-World Bank ACE Masters/PhD fellowship (ACE02-WACCBIP: Awandare). Part of this work was used for his MPhil Thesis.

Funding

The study was funded by Afrique One Consortium (Wellcome Trust - WT087535MA), Afrique One-ASPIRE (107753/A/15/Z) and the Ghana National Tuberculosis Programme (funded by the Global Fund).

Availability of data and materials

Data used for this study is available on request.

Abbreviations

- AFB

Acid fast bacilli

- AM-A

Amplification Mix A

- AM-B

Amplification Mix B

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- DST

Drug susceptibility testing

- FWA

Federal wide assurance

- INH

Isoniazid

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- LPA

Line probe assay

- MDR-TB

Multi-drug resistance Tuberculosis

- MGIT

Mycobacterium Growth Indicator Tube

- MTBC

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex

- NaOH-NALC

Sodium hydroxide-N-acetyl L-cysteine

- NMIMR

Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research

- NTM

Non-tuberculosis Mycobacterium

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- RIF

Rifampicin

- RR

Rifampicin Resistant

- TB

Tuberculosis

- WHO

World Health Organization

- ZN

Ziehl-Neelsen

Additional file

Map of Ghana showing study areas. Each of the 98 clusters (activity centres) are shown in red dots across the 10 regions in Ghana. (JPEG 1202 kb)

Authors’ contributions

KKA came out with the study design and contributed reagents and materials. Supervised the laboratory work and contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. SOA performed the laboratory work, contributed to the manuscript writing and data analysis. GIM assisted with the laboratory analysis and manuscript writing. LM contributed to data analysis and editing of the manuscript. FAB contributed to the study implementation by providing reagents and equipment. All authors read and approved the final manuscript before submission.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The main study (Assessing tuberculosis disease prevalence in Ghana through a population based survey) obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR) [FWA 00001824; IRB 00001276].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-017-2853-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Kennedy Kwasi Addo, Phone: (+233) 243 334 869, Email: kaddo@noguchi.ug.edu.gh.

Samuel Ofori Addo, Email: soaddo@noguchi.ug.edu.gh.

Gloria Ivy Mensah, Email: gmensah@noguchi.ug.edu.gh.

Lydia Mosi, Email: lmosi@ug.edu.gh.

Frank Adae Bonsu, Email: fabonsu@gmail.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2015, Geneva, Switzerland. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/191102/1/9789241565059_eng.pdf. Accessed 7 Oct 16.

- 2.Kwon Y-S, Koh W-J. Distinguishing between pulmonary tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(6):633. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony R, Cobelens FGJ, Egwaga SM, Goh KS, Narayanan PR, Ridderhof J, et al. Molecular line probe assays for rapid screening of patients at risk of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). WHO expert group report. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safianowska A, Walkiewicz R, Nejman-Gryz P, Chazan R, Grubek-Jaworska H. Diagnostic utility of the molecular assay GenoType MTBC (HAIN Lifescience, Germany) for identification of tuberculous mycobacteria. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2009;77(6):517–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russo C, Tortoli E, Menichella D. Evaluation of the new GenoType Mycobacterium Assay for identification of mycobacterial species. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:334–339. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.334-339.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asante-Poku A, Otchere ID, Danso E, Mensah DD, Bonsu F, Gagneux S, et al. Evaluation of Genotype MTBDRplus for rapid detection of drug resistant tuberculosis in Ghana. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(8):954–959. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . Tuberculosis prevalence surveys: a handbook. 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. p. 324. [Google Scholar]

- 8.BD MGIT™ TBc Identification Test Product Insert. Becton, Dickinson and Company. Sparks, MD, USA. www.puls-norge.no/media/283214/tbcid-brosjyre.pdf

- 9.Instructions for Use for GenoType Mycobacterium MTBC. http://www.hain-lifescience.de/include_datei/kundenmodule/packungsbeilage/download.php?id=981. Accessed on 10 Aug 2017.

- 10.Instructions for Use for GenoType Mycobacterium MTBDRplus. http://www.hain-lifescience.de/include_datei/kundenmodule/packungsbeilage/download.php?id=936. Accessed on 10 Aug 2017.

- 11.Instructions for Use for GenoType Mycobacterium CM. http://www.hain-lifescience.de/include_datei/kundenmodule/packungsbeilage/download.php?id=776. Accessed on 10 Aug 2017.

- 12.Instructions for Use for GenoType Mycobacterium AS. http://www.hain-lifescience.de/include_datei/kundenmodule/packungsbeilage/download.php?id=72. Accessed on 10 Aug 2017.

- 13.Instructions for Use for GenoType Mycobacterium NTM-DR. http://www.hain-lifescience.de/include_datei/kundenmodule/packungsbeilage/download.php?id=981. Accessed on 10 Aug 2017.

- 14.Yeboah-Manu D, Asante-Poku A, Bodmer T, Stucki D, Koram K, Bonsu F, et al. Genotypic diversity and drug susceptibility patterns among M. tuberculosis complex isolates from south-western Ghana. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurniawati F, Sulaiman SAS, Gillani SW. Study on drug-resistant tuberculosis and tuberculosis treatment on patients with drug resistant tuberculosis in chest clinic outpatient department. Int J Pharm Sci. 2012;4(2):733–737. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Limo J, Bii C, Musa ON, Galgalo T, Mutua D, Nkirote R, et al. Infection rates and correlates of non-tuberculous mycobacteria among tuberculosis retreatment cases in Kenya. Prim J Soc Sci. 2015;4(7):1128–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Živanović I, Vuković D, Dakić I, Savić B. Species of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and non-tuberculous mycobacteria in respiratory specimens from Serbia. Arch Biol Sci Belgrade. 2014;66(2):553–561. doi: 10.2298/ABS1402553Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Getahun M, Ameni G, Kebede A, Yaregal Z, Hailu E, Medihn G, et al. Molecular typing and drug sensitivity testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated by a community-based survey in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:751. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2105-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rufai SB, Kumar P, Singh A, Prajapati S, Balooni V, Singh S. Comparison of XPERT MTB/RIF with line probe assay for detection of rifampin-monoresistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(6):1846–1852. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03005-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owusu-Dabo E, Adjei O, Meyer C, Horstmann R, Enimil A, Kruppa T, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug resistance, Ghana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(7):1170–1172. doi: 10.3201/eid1207.051028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeboah-Manu D, Asante-Poku A, Ampah KA, Kpeli G, Danso E, Owusu-Darko K, et al. Drug susceptibility pattern of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Ghana; correlation with clinical response. Mycobac Dis. 2012;2:107.

- 22.Barnard M, Albert H, Coetzee G, O'Brien R, Bosman M. Rapid molecular screening for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in a high-volume Public Health Laboratory in South Africa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(7):787–792. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200709-1436OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacoma A, Garcia-Sierra N, Prat C, Ruiz-Manzano J, Haba L, Roses S, et al. GenoType MTBDRplus assay for molecular detection of Rifampin and Isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains and clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(11):3660–3667. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00618-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haas WH, Schilke K, Brand J, Amthor B, Weyer K, Fourie PB, et al. Molecular analysis of katG gene mutations in strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex from Africa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1601–1603. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mäkinen J, Marjamäki M, Marttila H, Soini H. Evaluation of a novel strip test, GenoType mycobacterium CM/AS, for species identification of mycobacterial cultures. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:481–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh AK, Maurya AK, Umrao J, Kant S, Kushwaha RAS, Nag VL, et al. Role of GenoType mycobacterium common mycobacteria/additional species assay for rapid differentiation between Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and different species of non-tuberculous mycobacteria. J Lab Physicians. 2013;5(2):83–89. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.119863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kehrmann J, Kurt N, Rueger K, Bange F-C, Buer J. GenoType NTM-DR for identifying Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies and determining molecular resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 2016; doi:10.1128/JCM.00147-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data used for this study is available on request.