Abstract

Despite therapeutic advancements, there has been little change in the survival of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Recent results suggest that cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) drive progression of this disease. Here, we report that autophagy is upregulated in HNSCC-associated CAFs where it is responsible for key pathogenic contributions in this disease. Autophagy is fundamentally involved in cell degradation, but there is emerging evidence that suggests it is also important for cellular secretion. Thus, we hypothesized that autophagy-dependent secretion of tumor-promoting factors by HNSCC-associated CAFs may explain their role in malignant development. In support of this hypothesis, we observed a reduction in CAF-facilitated HNSCC progression after blocking CAF autophagy. Studies of cell growth media conditioned after autophagy blockade revealed levels of secreted IL-6, IL-8 and other cytokines were modulated by autophagy. Notably, when HNSCC cells were co-cultured with normal fibroblasts they upregulated autophagy through IL-6, IL-8 and bFGF. In a mouse xenograft model of HNSCC, pharmacological inhibition of Vps34, a key mediator of autophagy, enhanced the antitumor efficacy of cisplatin. Our results establish an oncogenic function for secretory autophagy in HNSCC stromal cells that promotes malignant progression.

Keywords: Secretory Autophagy, Tumor Microenvironment, Tumor Associated Fibroblast, HNSCC, unconventional protein secretion

Introduction

As the fifth most common cancer worldwide, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is a leading global health burden (1). HNSCC causes significant morbidity and mortality, associated with intensive treatment protocols and a five-year survival rate of less than 50% (2). Despite therapeutic advancements, the survival rate has remained relatively unchanged for the last forty years. A better understanding of the biology of the disease is necessary for improving these dismal outcomes.

In the past decade, the tumor microenvironment’s role in promoting cancer progression and resistance to therapy has gathered great attention (3). Cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) form the predominant non-malignant cell type in the HNSCC microenvironment. Studies in our lab and others have demonstrated the critical role CAFs play in facilitating HNSCC progression (4). CAFs promote HNSCC progression by secreting growth factors, remodeling the extracellular matrix, and potentiating therapy resistance (5). HNSCC cells symbiotically communicate with CAFs through secreted factors (6); however, little is understood of the activation and biology of CAFs.

The survival-promoting pathway of autophagy is upregulated in many cancer types, including HNSCC. Autophagy serves to capture and degrade intracellular components for homeostasis, metabolism, and cell survival. Initiation of autophagy centers around the phosphorylation of the Beclin-1/Vps34 complex, which initiates the nucleation of an autophagosome (7). Autophagy-related gene product (Atg8) mammalian homologue LC3 is cleaved and lipidated (the lipidated form denoted as LC3-II), and is incorporated into the autophagosome membrane, serving as the most widely recognized marker of the autophagosome (8). SQSTM1 or p62, acts as a molecular shuttle, to target ubiquinated cargo to the autophagosome (9). The autophagosome is trafficked to the lysosome. LC3-II in the autophagosome is rapidly degraded upon fusion with the lysosome. In order to accurately determine the levels of LC3-II undergoing rapid degradation, it is essential to inhibit the degradative enzymes in the lysosome thus inhibiting autophagic flux. Chloroquine (CQ) neutralizes the acidity in the lysosome, inactivating the enzymes and preventing the degradation of the autophagosome (10,11).

There are a number of ongoing clinical trials investigating the role of autophagy inhibition in several cancer types, both as a stand-alone therapy and as an adjuvant to conventional therapeutic regimens. Accumulating evidence indicates the improvement of anticancer regimens by adjuvant autophagy inhibition (12). However, these studies are limited by the high doses of hydroxychloroquine, an orally available modification of CQ, with no clinically viable alternatives (13). Promisingly, advances in the understanding of the autophagic pathway over the last decade have resulted in small molecule inhibitors that specifically target autophagy, such as SAR405, which targets Vps34 (14).

Although paradigmatically a degradation pathway, a growing appreciation for a novel role of autophagy in cellular secretion has been reported (15). Secretory autophagy is involved in the export of a variety of cellular cargoes. This includes inflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-18 (16,17); granule contents from Paneth, mast, goblet, and endothelial cells (18–21); as well as release of intracellular pathogens (22). Additionally, high levels of basal autophagy correlate with a unique secretory profile when compared to cancer cells with lower levels of autophagy (23).

We set out to investigate the role of autophagy in HNSCC patient-derived CAFs, and discovered a high basal level of autophagy compared to NFs derived from the same anatomic location. Mitigating autophagy significantly reduced CAF-induced HNSCC progression. We further assessed the role of autophagy on HNSCC tumor growth. Treatment with Vps34 inhibitor, SAR405, attenuated xenograft growth. Further, autophagy inhibition potentiated the effects of standard of care therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Reagents

HNSCC and tonsil or uvulopalatoplasty explants from cancer-free patients were collected with written consent from patients under the auspices of the University of Kansas Medical Center Biospecimen Repository Core Facility. All protocols for collection and use were approved by the Human Subject Committee at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Primary fibroblast explants were established using our previously described protocol (4), and all fibroblast lines used were cultured for no more than 12 passages. In all experiments, results presented are from fibroblasts derived from a minimum of 2 patient explants.

Well characterized HNSCC cell lines (UM-SCC-1 (a gift from Dr. Tom Carey, University of Michigan), OSC19 (a gift from Theresa Whiteside, University of Pittsburgh), HN5, (a gift from Dr. Jeff Myers, MD Anderson), were used in this study (24). Established cell lines authenticated by STR profiling at Johns Hopkins in 2015 using the Promega Geneprint 10 kit and analyzed using Genemapper v4.0 software. All cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Corning, Corning, NY) with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) without antibiotics. Cells were incubated at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2.

Chloroquine diphosphate salt, 4-nitroquinoline N-oxide (4-NQO), IL-6, IL-8 and bFGF were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. SAR405 was obtained through APExBIO (Houston, TX). Cisplatin was obtained from Fresenius Kabi (Lake Zurich, IL).

Antibodies used: LC3 A/B (#12741), Beclin-1 (#4122), phospho-p70 S6K (Thr389) (#9205), Stat3 (#9139), phospho-Stat3 (Tyr705) (#9145) from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA); β-tubulin from Sigma-Aldrich; p62 (SQSTM1, M01) from Abnova (Taipei, Taiwan); Vimentin (#6260) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX); neutralizing antibodies, IL-6 (6708), IL-8 (6217), and secondary anti-rabbit IgG Dylight 680 (#35568), anti-rabbit IgG Dylight 488 (#35553), and anti-mouse IgG Dylight 800 (#35521) from ThermoFisher (Waltham, MA). Hoescht 33342 was used as nuclear counter stain (ThermoFisher).

Primer sequences used: mTOR (F: GGCCGACTCAGTAGCAT; R: CGGGCACTCTGCTCTTT); SOX2 (F: ACGGAGCTGAAGCCGCC; R: CTTGACGCGGTCCGGGCT); β-ACTIN (F: AGGGGCCGGACTCGTCATACT; R: GGCGGCACCACCATGTACCCT), all obtained from ThermoFisher.

Control (#44236), siBECN1 (#29797), and siFGF-2 (#39446) siRNA was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Electron Microscopy

Tissues were processed at KUMC Electron Microscopy research lab facility. Tissue samples were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M cacodylate buffer, and postfixed in 1.5% osmium tetraoxide. Samples were embedded in resin-propylene oxide and allowed to cure. Tissues were sectioned using a diatome diamond knife on a Leica UC-7 ultra microtome at 80 nm thickness. Sections were collected on 200 mesh copper grids, and samples imaged using a J.E.O.L. JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope at 100KV.

Immunoblotting

Whole-cell lysates were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer and a mixture of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Minitab, Roche). Lysates were sonicated on ice, debris removed by centrifugation, and supernatants stored at −80 °C. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide 12% gels were used to separate proteins, and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-Cor) in a 1:1 mixture with PBS 1% Tween-20 (PBST). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight in 1:1 blocking buffer to PBST. Primary antibodies were detected using DyLight conjugated secondary antibodies. Protein bands were detected using Li-Cor odyssey protein imaging system and quantified using ImageJ software (v. 1.50i).

Immunofluorescent Imaging

Cells were plated at a low confluence (10,000 cells per well) in 8-well chamber slides (Thermo Fisher). Methanol (70%) was used to fix cells. Triton-x (0.5%) in PBS was used as a permeablization buffer. Cells were blocked with a 2% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) solution. For paraffin sections, paraffin was removed by xylene, and section was rehydrated by ethanol titration. Antigen was retrieved using sodium citrate solution. Both cells and tissue sections were then incubated overnight in primary antibody (1:100 concentration in 2% BSA) at 4 °C. Dylight (488-anti rabbit; 550-anti-mouse) conjugated secondary antibodies were used, and hoescht staining following manufacturer’s instructions for nuclear detection. Slides were mounted with coverslip in vectashield mounting media. Images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 inverted microscope with a Photometrics Coolsnap HQ2 camera. LC3 puncta per cell of at least 30 cells in each experimental arm were identified by blinded observer at 20x magnification.

Conditioned Media Collection

CAFs (3×105 cells/well in 60mm dish) were plated in 10% FBS DMEM, and were treated with 20 μM Chloroquine for 6 h or vehicle control (H2O). Following drug treatment, cells were washed 2 times with serum free media, and then conditioned media was collected over 24 h in serum free DMEM. Following conditioned media collection, cell lysates were harvested for immunoblot to confirm autophagy inhibition by assessing LC3 levels. Conditioned media supernatants were clarified by centrifugation and stored for no more than 2 weeks at 4°C.

CAFs (3×105 cells/well in 60mm dish) were plated in 10% FBS DMEM, and were transfected with 100 nM siBeclin-1, siATG7 or siControl (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) containing lipofectamine-2000 (ThermoFisher) liposomes in Opti-MEM for 4 h. Media was changed to 10% FBS DMEM overnight, and conditioned media collection began the next day for 24 h in serum free DMEM. Following conditioned media collection, cell lysates were harvested for immunoblot to confirm siBECN knockdown. Conditioned media was clarified by centrifugation and stored for no more than 2 weeks at 4 °C.

Proliferation

HNSCC cells were seeded in triplicate (2000 cells/well, 96-well plate). After cells had adhered, various experimental conditions were applied for 72 h duration. Cell viability was assessed using CyQuant proliferation kit (life technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For irradiation experiments, plates were exposed to gamma radiation (J.L. Shepherd and Associates Mark I Model 68A cesium-137 source irradiator; dose rate = 2.9 Gy/min).

Invasion & Migration

Cell invasion and migration was assessed using transwell Boyden chamber system. HNSCC cells were seeded in 8 μm pore inserts for migration. For invasion, a layer of diluted (2 mg/mL) growth factor reduced matrigel (Corning) in DMEM was placed in the insert. HNSCC cells in serum-free media were seeded onto matrigel. The inserts were placed in triplicate holding-wells containing treatment conditions for 24 h. Cells were also plated in experimental conditions in parallel to assess viability using CyQuant. The number of cells that moved to other side of membrane was counted after fixation and staining with Hema3 Kit (Fisher). The number of invading or migrating cells was normalized to cell viability.

Cytokine Array

Cytokine array (C5) was obtained from RayBiotech (Norcross, GA) and conditioned media from CAFs was analyzed following the manufacturer’s instructions.

PCR

HNSCC cells were CFSE (ThermoFisher) labeled following manufacturer’s protocol. CFSE labeled HNSCC cells were co-cultured in a 1:1 ratio with unlabeled NFs for 72 h. Cells were harvested by trypsinization and FACS sorted using BD FACSAria IIIu. RNA was extracted from harvested cells using TRIzol reagent (Fisher) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was subjected to DNAse digestion prior to cDNA preparation using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). PCR products were resolved on agarose gel and imaged. Densitometric analyses were performed with ImageJ (v1.50i). PCR array (PAHS-176ZD, Qiagen) was used to identify differences between NFs and co-cultured NFs, and read using CFX96 Real-Time System (Biorad, Hercules, California).

Co-culture Proliferation Assay

HNSCC cells were CFSE (ThermoFisher) labeled following manufacturer’s protocol. CFSE labeled HNSCC cells were co-cultured in 1:1 ratio with unlabeled CAFs for 72 h. Cells were harvested by trypsinization and labeled HNSCC cells were counted using Attune NxT Flow Cytometer (Life Technologies).

In vivo Experiments

All experiments were approved by the institutional review board at the University of Kansas Medical Center. To assess biomarker modulation by chloroquine, 100 μL of HNSCC (UM-SCC-1, 0.5×106) alone or admixed with CAFs (0.5×106) were injected into the right flank of athymic male mice (n=3/group). After tumors were allowed to form, chloroquine was administered by oral gavage (162 mg/kg) for three days (25). Tissue was processed for electron microscopy.

To assess autophagy inhibition in combination with cisplatin, 100 μL of admixed HNSCC (UM-SCC-1, 0.5×106) and CAFs (0.5×106) were injected into the right flank of athymic female mice. Mice (n=9/group) were treated with cisplatin (3 mg/kg i.p. 1x/week), chloroquine (162 mg/kg oral gavage, 5 days/week) or SAR405 (50 μL intratumoral injection of 10 μM SAR405 in PBS, concentration determined based on in vitro IC50, 5 days/week). Tumor diameters were measured by a blinded observer using Vernier calipers in two perpendicular dimensions as previously described (4). Tumors were excised and processed for electron microscopy.

To assess progression of autophagy in developing tumor, 4-NQO (100 ppm in sterile drinking water ad libitum (26)) was administered for 16 weeks to C3H mice. Mice were then given sterile drinking water for 3 weeks, and tongues were excised.

The Cancer Genome Atlas Data Analysis

TCGA head and neck cancer (HNSC) cohort gene expression RNAseq data downloaded using UCSC Xena Browser (http://xena.ucsc.edu). Expression levels of BECN1 or MAP1LC3B were designated as high or low in relation to median expression of gene-level transcription estimates (log2(x+1) transformed RSEM normalized count). This was matched to clinical survivorship data from TCGA HNSC Phenotype data downloaded from UCSC Xena.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Non-parametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests were used to assess significance in all experiments, and Kruskal Wallis test for comparison of multiple groups. For in vivo study, one-way analysis of variance test was employed to assess the level of significance in tumor volumes between treatment arms. For TCGA survivorship comparison, log rank (Mantel-Cox) test assessed differences between curves. All statistical calculations were performed on Graphpad Prism Software (version 6.03), with significance determined by p<0.05.

Results

CAFs demonstrate High level of Basal Autophagy

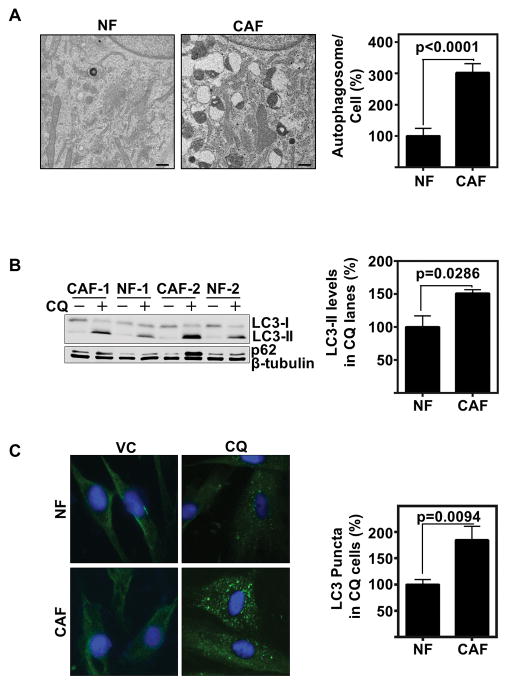

Our lab and others have identified the significant role CAFs play to enhance HNSCC progression (4). CAF-induced progression was significantly greater than NF-induced progression. To better understand the underlying biology of CAFs, we assessed CAFs compared to NFs by electron microscopy and identified a significantly enhanced vesicular architecture of the cancer associated fibroblasts compared to normal fibroblasts (Fig 1A, and low magnification in Supplemental Fig 1A). The vesicular electron-dense morphology led us to question if CAFs had a heightened level of basal autophagy compared to NFs (27). As such, we assessed autophagy marker LC3, which is enzymatically conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine during autophagic flux to LC3-II, and the autophagy shuttling protein, p62 (8). To evaluate basal autophagy, comparative LC3-II levels were assessed between NF and CAFs with and without the autophagic flux inhibitor, CQ. By immunoblot (Fig 1B, and Supplemental Fig 1B), we identified CAFs have significantly greater LC3-II (p=0.0286), although p62 was a bit more variable in expression. LC3-II expression was validated by visualizing and quantification of autophagic puncta by immunofluorescence of LC3 (p=0.0094) (Fig 1C and low magnification images in Supplemental Fig 1C). Therefore, we concluded CAFs have an increased rate of basal autophagy compared to NFs.

Figure 1. CAFs have greater basal autophagic flux than NFs.

(A) Electron microscopy exhibits highly vesicular architecture of CAFs with heterogeneous electron dense and electron poor organelles compared to NFs. Scale bars represent 0.5 μm. Graph depicts percent autophagosomes/fibroblast relative to NF. Autophagosomes were counted in a total of 36 fibroblasts from each group including 4 explants each from HNSCC or cancer-free subjects. Error bars represent ± SEM.

(B) Representative immunoblot of CAFs compared with NFs with and without CQ (20 μM for 6 h) for LC3 protein conversion and p62. Graph depicts percent cumulative density of LC3 levels in CQ treated lanes relative to NF, in 4 explants each of HNSCC or cancer-free subjects. LC3-II levels were normalized to β-tubulin levels. Error bars represent ± SEM.

(C) Representative immunofluorescent of LC3 (green) puncta, Hoechst nuclear stain (blue), comparing NF with CAFs with and without CQ (80 μM for 2 h) (60x magnification). Cumulative results of LC3 puncta per cell counted by a blinded observer of at least 30 cells each of NFs and CAFs. The experiment was repeated 3 times using 3 explants each from HNSCC or cancer-free subjects. Error bars represent ± SEM.

Mitigation of CAF autophagy decreases HNSCC progression in vitro

We hypothesized CAF autophagy facilitates tumor progression. As we previously identified a role of CAF secreted factors on HNSCC progression, we began by establishing autophagy inhibited conditioned media. To do this, we inhibited autophagy using chloroquine, which inhibits lysosomal degradation of the autophagosome (28). Following chloroquine inhibition, cells were washed to remove excess extracellular chloroquine, and conditioned media was then collected. To confirm autophagy inhibition over the entirety of conditioned media collection, CAF lysates were harvested following collection and assessed for LC3-II conversion by immunoblot as an indicator of autophagic flux inhibition (Supplemental Fig 2A). Since serum starvation could potentially induce autophagy in CAFs, we evaluated the extent of autophagy induction upon 24 h serum starvation compared to baseline autophagy in serum containing media. Our data demonstrate that 24 h of serum starvation had little effect on the extent of autophagy in CAFs compared to that in 10% serum containing media. The comparison of 10% FBS DMEM (complete media) and 24 h of serum starvation on autophagic flux is demonstrated in Supplemental Fig 2B. Additionally, to confirm there was negligible remaining chloroquine in the conditioned media, we devised a control where chloroquine was only administered for 5 minutes, washed off, and then conditioned media was harvested in a similar fashion. This five-minute treatment did not induce LC3-II conversion observed by immunoblot, and did not influence HNSCC migration compared to vehicle control (Supplemental Fig 2C, D).

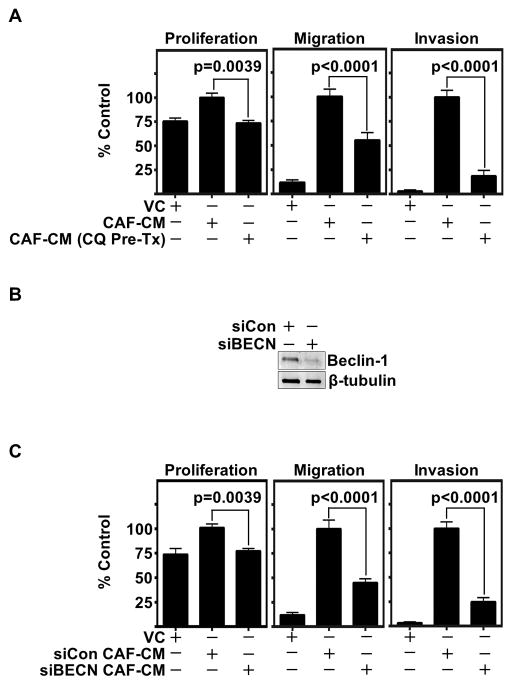

We assessed autophagy inhibited CAF conditioned media (CAF-CM) and found autophagy inhibition significantly decreased HNSCC migration, invasion and proliferation (Fig 2A and Supplemental Fig 2E). To validate our observations, we inhibited autophagy in CAFs by siRNA knockdown of Beclin-1, an upstream regulator of autophagy (29). Successful knockdown at conditioned media endpoint was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Fig 2B, Supplemental Fig 2F). Again, significant reductions in HNSCC migration, invasion, and proliferation were observed following knockdown of autophagy (Fig 2C). Further, these findings were validated by siRNA knockdown of Atg7 (30), which demonstrated a significant decrease in HNSCC migration and invasion (Supplemental Fig 2G, H). These findings demonstrate that CAF autophagy-dependent secretion promotes HNSCC progression.

Figure 2. CAF autophagy inhibition significantly decreases CAF-facilitated HNSCC progression in vitro.

(A) CAFs pretreated with CQ (20 μM for 6 h) were washed extensively to remove excess chloroquine and then conditioned media (CM) was collected with and without CQ pre-treatment. HNSCC (OSC19) migration, invasion, and proliferation are significantly reduced in CAF autophagy inhibited CM. Graph depicts cumulative results from three independent experiments including triplicate treatments, using CAFs derived from two HNSCC patients. Migration and invasion experiments were normalized to cell viability. Error bars represent ± SEM.

(B) Representative immunoblot confirming Beclin-1 knockdown throughout CAF-CM collection.

(C) Significant reduction observed in HNSCC migration, invasion, and proliferation with Beclin-1 knockdown CAF-CM (siBECN) compared to Control siRNA (siCon). Graph depicts combined results of at least three trials per experiments plated in triplicate using at least two different CAF patient samples. Migration and invasion experiments normalized to cell viability. Error bars represent ± SEM.

Autocrine and paracrine IL-6 and IL-8 regulate CAF autophagy

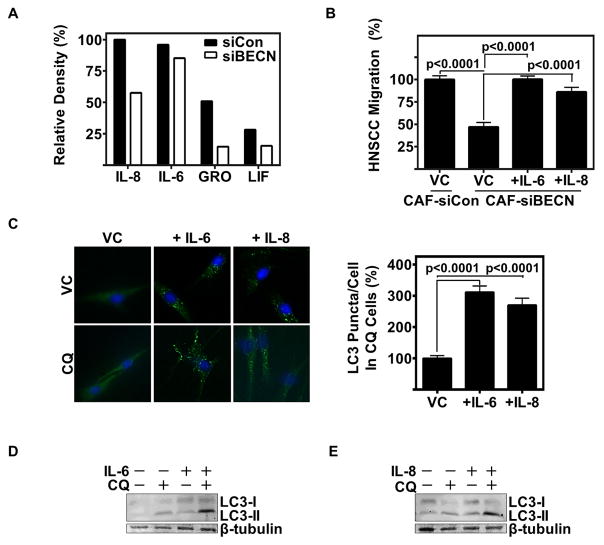

Recently, a growing appreciation for the role of the autophagic machinery in cellular secretion has been reported (31). Our data indicate an autophagy regulated secretome that influences HNSCC progression in vitro. A cytokine array was used to identify changes in CAF secreted factors following autophagy inhibition. By siRNA knockdown of Beclin-1, we observed a significant decrease in a number of CAF-secreted cytokines (Fig 3A), most notably being IL-8 and IL-6. Reconstitution of IL-6 and IL-8 in autophagy impaired CAF-CM restored CAF-CM-induced HNSCC migration (p<0.0001) (Fig 3B). Therefore, autophagy in part regulates the secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 from CAFs, facilitating HNSCC migration.

Figure 3. CAFs secrete IL-6 and IL-8 through autophagy, which further induce autophagy in an autocrine pathway.

(A) Relative density of top 4 cytokines recognized on cytokine array of CAF-CM with Beclin-1 siRNA knockdown (siBECN) or Control siRNA (siCon).

(B) Reconstitution of HNSCC (UM-SCC-1) migration in Beclin-1 knockdown CAF-CM with recombinant IL-6 (10 ng/mL) and IL-8 (80 ng/mL); data cumulative of two trials plated in duplicate using different CAF patient samples.

(C) Representative IF of NF treated with vehicle control (water), IL-6 (10 ng/mL), or IL-8 (80 ng/mL) for 24 h with and without CQ (80 μM for last 2 h of cytokine treatment) (20x magnification). Graph depicts cumulative results of LC3 puncta per cell counted by a blinded observer of at least 30 cells per experimental arm in three separate experiments. Error bars represent ±SEM.

(D&E) Representative immunoblot of NF treated with (D) IL-6 (10 ng/mL), or (E) IL-8 (80 ng/mL) for 24 h with and without CQ (20 μM for last 6 h of treatment).

Previous reports have demonstrated a role for IL-6 in promoting autophagy (32). As such, we investigated the autocrine effects of IL-6 and IL-8 on autophagy in normal fibroblasts (NFs). Interestingly, we observed a significant increase in LC3 puncta per cell in NFs treated with IL-6 or IL-8 (p<0.0001) (Fig 3C and Supplemental Fig 3A). This finding was validated by assessing LC3-II levels using immunoblotting (Fig 3D, E). Both IL-6 and IL-8 induced LC3-II, indicating an induction of autophagy. It has been well established that HNSCC secretes IL-6 and IL-8 (33), and this may be one method by which the tumor modulates the surrounding stroma. Neutralizing antibodies to IL-6 and IL-8 mitigated HNSCC induction of autophagy in NFs (Supplemental Fig 3B). This induction of autophagy in fibroblasts may occur through paracrine stimulation of IL-6 and IL-8 by HNSCC, and autocrine factors from activated fibroblasts.

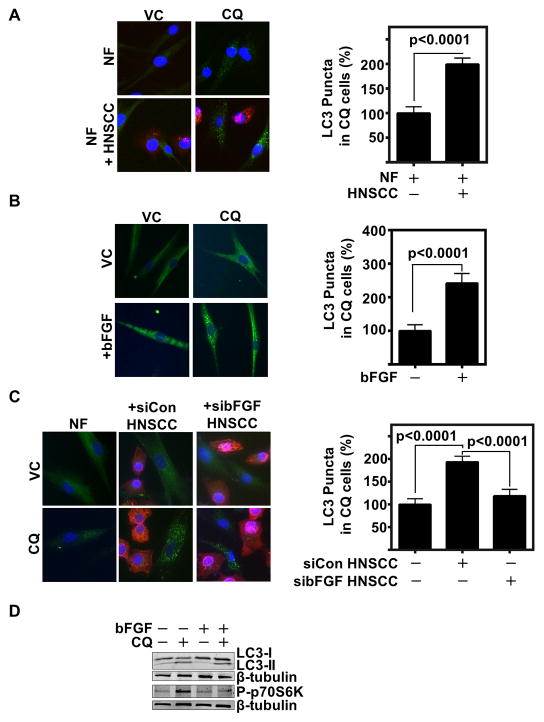

HNSCC factors induce head and neck fibroblast autophagy

With CAFs having a significantly greater level of basal autophagy than NFs, we sought to identify if HNSCC promotes CAF autophagy. We co-cultured NFs with HNSCC, and observed an increase in LC3 puncta per cell (Fig 4A and Supplemental Fig 4A). Other studies in our lab have identified a role of HNSCC secreted bFGF in inducing CAF activation through FGFR signaling. Therefore, we hypothesized bFGF may be a causative factor in the induction of CAF autophagy. There was a significant increase in LC3 puncta in NFs treated with bFGF (p<0.0001) (Fig 4B, and Supplemental Fig 4B). This indicated HNSCC secreted bFGF, as well as IL-6 and IL-8 promoted CAF autophagy. Therefore, to confirm this induction, we co-cultured HNSCC and NF with siRNA to bFGF in the HNSCC cells. We demonstrate that inhibiting HNSCC secreted bFGF limits HNSCC induced fibroblast autophagy (Fig 4C, and Supplemental Fig 4C). Additionally, treatment of NFs with recombinant bFGF also increased IL-6 and IL-8 secretion (Supplemental Fig 4D).

Figure 4. HNSCC induces CAF autophagy through paracrine secretion of bFGF.

(A) Representative IF of NFs in a 1:1 co-culture with HNSCC (HN5) with and without CQ (80 μM for 2 h) with cytokeratin 14 HNSCC label (red), LC3 (green) and hoescht (blue) nuclear stain (20x magnification). Graph depicts cumulative results of LC3 puncta per cell counted by a blinded observer of CQ treated wells in at least 20 cells per group, results cumulative of three experiments using two different NF patient samples and presented relative to NF.

(B) Representative IF of NF with and without bFGF (100 ng/mL for 24 h) with CQ flux inhibition (80 μM for final 2 h of bFGF treatment), LC3 (green), hoescht nuclear (blue) (20x magnification). Graph depicts cumulative results of LC3 puncta per cell counted by blinded observer of NF +/− bFGF + CQ in at least 20 cells per group, and results are cumulative of three experiments using two different NF patient samples.

(C) Representative IF of NF, or NF co-cultured with either control siRNA transfected HNSCC (HN5) (siCon) or bFGF siRNA transfected HNSCC (sibFGF) in a 1:1 ratio. CQ (80 μM for 2 h) was used to inhibit flux. LC3 (green) and hoescht (blue) are visualized at 20X magnification. Graph depicts cumulative results of LC3 puncta counted per cell in CQ treated wells of at least 39 cells per group, and presented relative to NF alone.

(E) Representative immunoblot of bFGF (100 ng/mL for 24 h) with and without CQ (20 μM for 6 h) treated NF of LC3 and phospho-p70S6K (Thr389).

To further determine the mechanism of fibroblast autophagy by HNSCC, we used PCR-based microarray analyses of various molecular regulators including transcription factors to identify signaling pathways upregulated when NFs were co-cultured with HNSCC. SOX2 and FGFR2 were highly upregulated in co-cultured NFs compared to NFs alone (Supplemental Fig 4E). Intriguingly, SOX2 transcriptionally represses mTOR, thereby inducing autophagy (34). SOX2 is a downstream target of bFGF. Therefore, we interrogated the role of FGFR signaling in HNSCC mediated SOX2 induction in NFs using pan FGFR inhibitor AZD-4547 (35). We validated the microarray finding by RT-PCR and observed an induction of SOX2 in NFs upon co-culture with HNSCC, which corresponded with a decrease in mTOR mRNA levels (Supplemental Fig 4F and G). Further, FGFR inhibition restored SOX2 levels (Supplemental Fig 4G). Further, we found that stimulation of fibroblasts with recombinant bFGF decreased phospho-p70S6K levels which is a signaling intermediate down-stream of mTOR (Fig 4D). This corresponded with an increase in LC3-II cleavage in NFs. HNSCC conditioned media activation of phospho-STAT3, a transcription factor downstream of FGFR, and LC3-II protein levels were inhibited with FGFR inhibition (Supplemental Fig 4H). These results suggest that HNSCC induces autophagy in CAFs through paracrine signaling, including bFGF, IL-6, and IL-8.

Mitigation of HNSCC autophagy decreases HNSCC progression in vitro

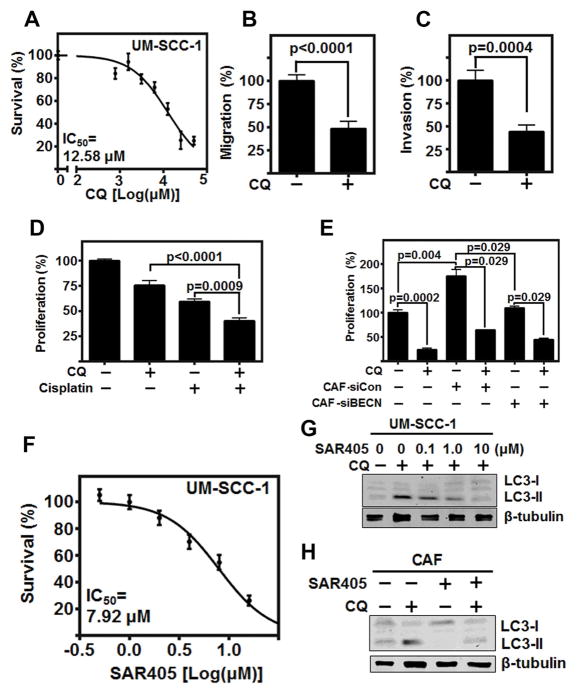

In HNSCC, increased levels of autophagy marker LC3 is associated with reduced overall survival (36). However, no studies have examined the therapeutic potential of autophagy inhibition in HNSCC. CQ, and it’s clinically relevant derivative hydroxychloroquine (37), have been assessed in a number of cancer types, but not HNSCC. We identified that CQ significantly inhibited the proliferation, migration (p<0.0001), and invasion (p=0.0004) of HNSCC cells (Fig 5A, B, & C, and Supplemental Fig 5A). Further, CQ potentiated the effects of cisplatin in combination treatment (Fig 5D). Additionally, the combination of CQ and radiation (3 Gy) also demonstrated a potentiated effect (Supplemental 5B). These data indicate the therapeutic potential of direct autophagy inhibition in HNSCC.

Figure 5. Autophagy inhibition significantly reduces HNSCC progression observed by in vitro models.

(A) CQ reduces HNSCC (UM-SCC-1) proliferation with IC50=11.51 μM over 72 h. (B&C) CQ mitigates HNSCC (UM-SCC-1) (B) migration and (C) invasion at IC50 concentration. Migration and Invasion normalized to cell viability, and graph depicts three experiments plated in duplicate.

(D) Combination of CQ (IC50) and Cisplatin (4 μM) significantly reduces HNSCC (UM-SCC-1) proliferation over 72 h graph depicts three experiments plated in triplicate.

(E) CFSE labeled HNSCC (HN5) proliferation over 72 h co-cultured in 1:1 ratio with CAFs with and without pre-treatment of Beclin-1 siRNA knockdown, and with and without CQ (IC50) throughout 72-hour co-culture. Graph depicts results of two separate experiments using two different CAF patient samples, plated in duplicate

(F) SAR405 reduces HNSCC proliferation with IC50=7.92 μM over 72 h, graph depicts three experiments plated in triplicate.

(G) Representative immunoblot of increasing doses of SAR405 with and without CQ flux inhibition (20 μM for 6 h). Experiment repeated twice.

(H) Representative immunoblot of 1.0 μM SAR405 on CAF with and without CQ flux inhibition (20 μM for 6 h). Experiment repeated twice. All error bars represent ±SEM.

To better delineate the effects of autophagy inhibition in the tumor cells compared to autophagy inhibition in CAFs, we established a co-culture assay of both cell types by labeling HNSCC cells with CFSE. Following a 72 h co-culture, HNSCC proliferation was determined by flow cytometry of labeled cells. This allowed for individual assessment of CQ treatment, and/or Beclin-1 knockdown in CAFs (Fig 5E). As observed with our previous proliferation study, CQ treatment of cancer cells alone significantly reduced HNSCC proliferation (p=0.0002). Addition of CAFs significantly increased HNSCC proliferation (p=0.004), which was ameliorated by both knockdown of Beclin-1 in CAFs (p=0.029) and the use of CQ (p=0.029). This further established the role of CAF autophagy in promoting HNSCC proliferation, which can be therapeutically mitigated.

In the clinic, high doses of chloroquine are required to inhibit autophagy, limiting its clinical utility (38). To overcome this, recent understanding of the autophagic pathway has led to the development of highly specific small molecule inhibitors of autophagy, such as SAR405 (14), which inhibits Vps34, a class III PI3K unique to autophagy (39).

As such, we investigated the therapeutic potential of SAR405 in HNSCC cell lines. Although a relatively high IC50 (7.92 μM), was required to limit HNSCC proliferation (Fig 5F and Supplemental Fig 5C), SAR405 significantly inhibited LC3-II conversion at a low concentration, (0.1 μM) (Fig 5G). Additionally, SAR405 did not significantly reduce CAF proliferation (Supplemental 5D); however, CAF autophagy as assessed by LC3-II conversion was significantly limited at low concentration of inhibitor (1 μM) (Fig 5H). Thus, we assessed the therapeutic relevance of limiting HNSCC progression in combination therapy using the standard of care, cisplatin, with SAR405. The low concentration of SAR405 (1 μM) necessary to limit autophagic flux enhanced the effect of cisplatin (4 μM) in combination therapy (p<0.0001) (Supplemental Fig 5E).

Combination therapy significantly reduces HNSCC tumor volume

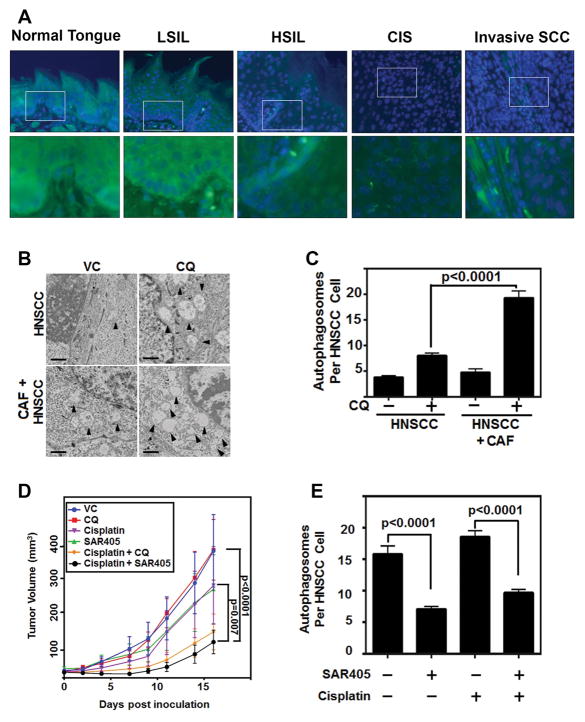

Given the promising results observed in vitro, we sought to assess autophagy inhibition in murine models of HNSCC. To better understand autophagy through the progression of this disease, we used a 4-NQO carcinogen induced model of HNSCC, and assessed the tongues in various stages of disease progression (26). By interrogating this model, we were able to observe that scant LC3 puncta could be identified in the normal tongue epithelium, but there was significant LC3 puncta in dysplastic and cancerous tissues (Figure 6A). This further supported the therapeutic potential of targeting autophagy in HNSCC.

Figure 6. Autophagy inhibition significantly reduces HNSCC progression in vivo.

(A) Representative IF images of LC3 (green) puncta in 4-NQO induced HNSCC model progression from normal tongue epithelium, low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), carcinoma in situ (CIS), and invasive squamous cell carcinoma (Invasive SCCa) at 20x magnification, top, and 60x magnification, bottom. Arrowheads depict LC3 puncta accumulation. Blue is nuclear stain. White box indicates area of 60x image.

(B) Representative electron microscopy images of sections from CAF and HNSCC (UM-SCC-1) injected subcutaneously into nude male mice. CQ (162 μg/mL oral gavage) treatment significantly enhanced autophagosome accumulation.

(C) Autophagosomes per cell were counted by blinded observer from at least 48 cells from two different mice per treatment group.

(D) Autophagy inhibition potentiates standard of care therapy. 1:1 admixture of CAF & HNSCC (UM-SCC-1) were injected subcutaneously in nude female mice. Mice were treated with cisplatin (3 mg/kg i.p. 1x/week), chloroquine (162 mg/kg oral gavage, 5 days/week) or SAR405 (50 μL intratumoral injection of 10μM SAR405 in PBS) (n=9/group). Tumor volumes were assessed by a blinded observer.

(E) Autophagosomes counted by blinded observer of at least 13 cells from two different mice per treatment group of Vehicle control, SAR405, Cisplatin, and combination Cisplatin & SAR405.

To assess CQ dosing, we conducted a small pilot study of HNSCC alone or HNSCC and CAFs inoculated in a 1:1 admixture subcutaneously in athymic mice. CQ caused the accumulation of autophagosomes in the tumor cells, which was observed to significantly increase in the CAF & HNSCC cohort (p<0.0001) (Fig 6B, C, and more examples of counted autophagosomes in Supplemental Fig 6).

To assess autophagy inhibition in combination with current standard of care, cisplatin, HNSCC were inoculated in a 1:1 admixture subcutaneously in athymic mice. Mice were treated with autophagy inhibitors CQ or SAR405 and/or cisplatin. With the addition of autophagy inhibitor SAR405 to cisplatin therapy, there was a significant reduction in tumor volume when compared to SAR405 alone, cisplatin alone, or untreated mice (Fig 6D). Chloroquine and cisplatin combination treatment reduced tumor volume, but the reduction was not as significant as the more specific inhibitor, SAR405. Additionally, by electron microscopy, we were able to observe the significant reduction in autophagosomes per cell due to SAR405 therapy (Fig 6E). This indicates the use of targeted autophagy inhibition will potentiate the efficacy of current therapy.

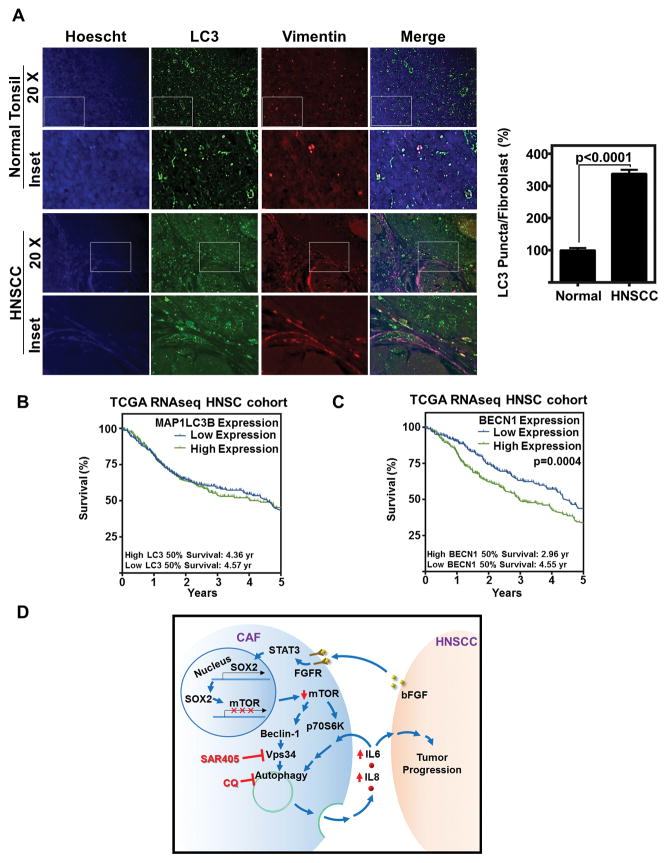

Therefore, to understand the role of autophagy in patient tissue, we assessed patient sections for autophagosomes. Pathologic immunohistochemistry identification of autophagy markers in patient tissue has given mixed results, with some studies indicating a favorable outcome with increased expression of autophagic markers and others indicating an unfavorable outcome (36,40). We identify that LC3 puncta were significantly increased in HNSCC fibroblasts as compared to normal specimens from cancer-free patients (Fig 7A).

Figure 7. Autophagy is overexpressed in patient fibroblasts, and overexpression of autophagy initiator, BECN1, is correlated with poor survival.

(A) Representative IF of LC3 (green) vimentin (red), or hoesct (blue) in normal tonsil from cancer free patients and HNSCC. Graph depicts LC3 puncta/fibroblast (as determined by vimentin positivity in spindle shaped cells) of 12 fibroblasts from 10 each of cancer-free and HNSCC patients (120 fibroblasts per group) and normalized to normal tonsil, error bars represent ±SEM.

(B) LC3 (MAP1LC3B) overexpression does not significantly correlate with survival. Data downloaded from TCGA HNSC cohort, and stratified by median MAP1LC3B RNA expression (RSEM). High expression was determined by primary tumor patient samples that had greater expression than median (Log2 Expression RSEM) (High Expression n=283; low expression n=283).

(C) BECN1 overexpression correlates with poor patient survival. Data downloaded from TCGA HNSC cohort, and stratified by median BECN1 RNA expression (RSEM). High expression was determined by primary tumor patient samples that had greater expression than median (0.00525 Log2 Expression RSEM) (High Expression n=283; low expression n=283).

(D) Schematic representation of the mechanism of autophagy induction in CAFs by HNSCC that facilitates HNSCC progression.

Finally, we assessed the TCGA database for expression levels of known autophagy regulators and their correlation with patient survival. Although expression of LC3 (MAP1LC3B) did not correlate with differences in patient survival (Fig 7B), there was a profound decrease in survival when the upstream initiator of autophagy, Beclin-1 (BECN1) was overexpressed (p=0.0004) (Fig 7C). In vitro, overexpression of Beclin-1 is a potent inducer of autophagy (29). These data, combined with our combination therapy data, indicate that autophagy inhibition with standard of care would likely improve outcomes for HNSCC patients. In summary, we have identified a role for secretory autophagy in the supporting stromal CAFs, which enhances HNSCC progression (Fig 7D).

Discussion

Reciprocal communication between cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment sustains and enables cancer progression. For the past decade, the contribution of stromal cell secreted factors to the progression of cancer has been appreciated (3), however the underlying secretory machinery involved remains enigmatic. We observed that CAFs in culture appear phenotypically different from NFs from the same anatomic location, displaying a highly vesicular architecture. This led us to question what fundamental biologic mechanisms account for the cancer-promoting secretory profile. In this study, we observe that primary patient-derived CAFs sustain an increased level of basal autophagy as compared to NFs from cancer-free patients. This is the first observation of enhanced fibroblast autophagy from primary CAFs-derived from patient stroma, and corroborates recent observations of breast cancer cells inducing autophagy in skin fibroblasts, and a Drosophila melanogaster tumor model where microenvironmental autophagy was observed (41,42).

While autophagy is conventionally a degradation pathway, recent reports of a role for autophagy in unconventional cellular secretion (31) prompted us to investigate the role for CAF autophagy in secreting tumor-promoting factors. By collecting CAF conditioned media under autophagy inhibition through both upstream knockdown of Beclin-1, Atg7 and downstream lysosomal inhibition using chloroquine, we observed significant phenotypic differences in cancer progression in vitro. This indicated CAF autophagy modulates secreted factors important for tumor progression. Using a cytokine array, we identified IL-6 and IL-8 as being autophagy modulated in their secretion, consistent with previous observations of autophagy controlled secretion of these factors in other systems. IL-6 and IL-8 are elevated systemically in patients with HNSCC (33), have been associated with resistance to targeted therapy (43), and are known to be secreted from stromal fibroblasts found in a number of cancer types (44). This is the first report linking CAF tumor-promoting cytokine secretion with autophagy. Interestingly, IL-6, and IL-8 are among a plethora of factors associated with the senescence associated secretory phenotype (45). We observed that primary CAF lines demonstrate rapid proliferation despite autophagy. Our data also demonstrate that knockdown of Beclin-1 mitigated secretory autophagy and consequently reduced the levels of IL-6 and IL-8 in CAFs. Thus, reduced IL-6 and IL-8 secretion on inhibition of autophagy coupled with the rapid proliferation of these fibroblasts leads us to the conclusion that this is not a replication induced senescent phenomenon. Recent reports indicate a role for autophagy controlled amino acid secretion by microenvironment cells of pancreatic cancer (46). Our data corroborate this finding and unveil a role for tumor microenvironment autophagy in altering secreted factors.

By co-culturing NFs from cancer free patients with HNSCC cells, an increase in fibroblast autophagy was observed. The list of known physiologic autophagy inducers is short (47), with amino acid/glucose starvation and reactive oxygen species being some of the only understood natural inducers. HNSCC metabolically outcompeting CAFs for extracellular nutrients may play a role in inducing CAF autophagy (48). However, assessment occurred in a short 24 h timeframe in high glucose DMEM, which likely indicates this is not a starvation or nutrient depletion phenomenon. We identified IL-6, IL-8, and bFGF, known HNSCC secreted factors, are all at least in part responsible for CAF autophagy. This corroborates recent findings in a Drosophila tumor model that IL-6 secretion from the tumor promotes stromal autophagy (42). We demonstrate HNSCC secreted bFGF activates STAT3, induces the transcription of SOX2, which inhibits mTOR transcription (34). As mTOR represses autophagy (50), SOX2 inhibition of mTOR conferred increased autophagy in the fibroblasts in our system. The dynamics of CAF autophagy regulation are even more complex when taken into account our observation that autophagy promoting IL-6 and IL-8 are also secreted through autophagic machinery.

There is extensive evidence in literature demonstrating that both chemotherapeutic drugs and radiation promote cytoprotective autophagy in tumor cells (51). Despite multiple studies in a variety of cancer cell types, investigations into the therapeutic potential of autophagy inhibition in HNSCC is lacking (52). Our results provide evidence for the first time of autophagy inhibition as having therapeutic potential in HNSCC. The largest limitations to autophagy treatment in clinical trials has been the high doses required of chloroquine, which may fail to achieve intratumoral concentrations sufficient to limit autophagy, and a lack of accepted methodology for monitoring autophagy in patients’ tumors to confirm successful inhibition (53). As such, a large body of research is investigating potential small molecule inhibitors of autophagy, and few have been discovered (54). SAR405 is one such inhibitor that specifically targets PI3K class III, of which the only recognized member is Vps34, an upstream autophagy regulating kinase. We observed that low doses of SAR405 (1.0 μM or less) were sufficient to limit HNSCC and CAF autophagy in vitro. This may provide a feasible therapeutic alternative to chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for clinical autophagy inhibition. The potentiated effects of HNSCC standard of care, cisplatin, with SAR405 in vivo were profound and give hope for future combinational therapy.

In summary, we demonstrate enhanced basal autophagy in CAFs which facilitates the secretion of tumor promoting factors, notably IL-6 and IL-8. HNSCC paracrine secretion of IL-6, IL-8 and bFGF is at least in part responsible for the promotion of CAF autophagy, which is further maintained through IL-6 and IL-8 autocrine feedback. Amelioration of HNSCC autophagy by both chloroquine and SAR405 give indication to the potential therapeutic value of combinatorial targeting of autophagy with HNSCC standard of care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

This study was supported in part by the University of Kansas Cancer Center under CCSG P30CA168524; an NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award grant (UL1TR000001, formerly UL1RR033179) awarded to the University of Kansas Medical Center and an internal Lied Basic Science Grant Program of the KUMC Research Institute (to S. M. Thomas); grant R01CA182872 (to S. Anant); grants R01AA020518, U01AA024733, P20GM103549 & P30GM118247 (to W.X. Ding); and the KUMC Biomedical Research Training Program (to J. New). We acknowledge support from the University of Kansas (KU) Cancer Center’s Biospecimen Repository Core Facility staff for helping obtain human specimens and for performing histological work. Immunofluorescence microscopy was supported by the Smith Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (NIH U54 HD 090216). The Flow Cytometry Core Laboratory which is sponsored, in part, by the NIH/NIGMS COBRE grant P30GM103326. The KUMC Electron Microscopy Research Lab facility is supported, in part, by NIH COBRE grant P20GM104936 and S10RR027564.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJM, Brakenhoff RH. The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1423–37. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wheeler SE, Shi H, Lin F, Dasari S, Bednash J, Thorne S, et al. Tumor associated fibroblasts enhance head and neck squamous cell carcinoma proliferation, invasion, and metastasis in preclinical models. Head & neck. 2014;36:385–92. doi: 10.1002/hed.23312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergers G, Hanahan D. Modes of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:592–603. doi: 10.1038/nrc2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis MP, Lygoe KA, Nystrom ML, Anderson WP, Speight PM, Marshall JF, et al. Tumour-derived TGF-beta1 modulates myofibroblast differentiation and promotes HGF/SF-dependent invasion of squamous carcinoma cells. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:822–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Y, Klionsky DJ. Physiological functions of Atg6/Beclin 1: a unique autophagy-related protein. Cell Res. 2007;17:839–49. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. The EMBO Journal. 2000;19:5720–8. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White E. The role for autophagy in cancer. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:42–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI73941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klionsky DJ, Abdelmohsen K, Abe A, Abedin MJ, Abeliovich H, Acevedo Arozena A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition) Autophagy. 2016;12:1–222. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizushima N, Yoshimorim T, Levine B. Methods in Mammalian Autophagy Research. Cell. 2010;140:313–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White E. The role for autophagy in cancer. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015;125:42–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI73941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eng CH, Wang Z, Tkach D, Toral-Barza L, Ugwonali S, Liu S, et al. Macroautophagy is dispensable for growth of KRAS mutant tumors and chloroquine efficacy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113:182–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515617113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ronan B, Flamand O, Vescovi L, Dureuil C, Durand L, Fassy F, et al. A highly potent and selective Vps34 inhibitor alters vesicle trafficking and autophagy. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:1013–9. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ktistakis NT, Tooze SA. Digesting the Expanding Mechanisms of Autophagy. Trends in cell biology. 2016;26:624–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupont N, Jiang S, Pilli M, Ornatowski W, Bhattacharya D, Deretic V. Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1beta. Embo j. 2011;30:4701–11. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narita M, Young AR, Arakawa S, Samarajiwa SA, Nakashima T, Yoshida S, et al. Spatial coupling of mTOR and autophagy augments secretory phenotypes. Science. 2011;332:966–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1205407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cadwell K, Liu JY, Brown SL, Miyoshi H, Loh J, Lennerz JK, et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature. 2008;456:259–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ushio H, Ueno T, Kojima Y, Komatsu M, Tanaka S, Yamamoto A, et al. Crucial role for autophagy in degranulation of mast cells. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2011;127:1267–76. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torisu T, Torisu K, Lee IH, Liu J, Malide D, Combs CA, et al. Autophagy regulates endothelial cell processing, maturation and secretion of von Willebrand factor. Nat Med. 2013;19:1281–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel KK, Miyoshi H, Beatty WL, Head RD, Malvin NP, Cadwell K, et al. Autophagy proteins control goblet cell function by potentiating reactive oxygen species production. Embo j. 2013;32:3130–44. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerstenmaier L, Pilla R, Herrmann L, Herrmann H, Prado M, Villafano GJ, et al. The autophagic machinery ensures nonlytic transmission of mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E687–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423318112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraya AA, Piao S, Xu X, Zhang G, Herlyn M, Gimotty P, et al. Identification of secreted proteins that reflect autophagy dynamics within tumor cells. Autophagy. 2015;11:60–74. doi: 10.4161/15548627.2014.984273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin CJ, Grandis JR, Carey TE, Gollin SM, Whiteside TL, Koch WM, et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines: established models and rationale for selection. Head Neck. 2007;29:163–88. doi: 10.1002/hed.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou Y, Ling Y-H, Sironi J, Schwartz EL, Perez-Soler R, Piperdi B. The autophagy inhibitor chloroquine overcomes the innate resistance to erlotinib of non-small cell lung cancer cells with wild-type EGFR. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2013;8(6):693–702. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31828c7210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang XH, Knudsen B, Bemis D, Tickoo S, Gudas LJ. Oral cavity and esophageal carcinogenesis modeled in carcinogen-treated mice. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2004;10:301–13. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0999-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eskelinen EL. Maturation of autophagic vacuoles in Mammalian cells. Autophagy. 2005;1:1–10. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.1.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Y-p, Hu L-f, Zheng H-f, Mao C-j, Hu W-d, Xiong K-p, et al. Application and interpretation of current autophagy inhibitors and activators. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34:625–35. doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, Brown K, Kempkes B, Hibshoosh H, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–6. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanida I, Mizushima N, Kiyooka M, Ohsumi M, Ueno T, Ohsumi Y, et al. Apg7p/Cvt2p: A novel protein-activating enzyme essential for autophagy. Molecular biology of the cell. 1999;10:1367–79. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.5.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ponpuak M, Mandell MA, Kimura T, Chauhan S, Cleyrat C, Deretic V. Secretory autophagy. Current opinion in cell biology. 2015;35:106–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delk NA, Farach-Carson MC. Interleukin-6. Autophagy. 2012;8:650–63. doi: 10.4161/auto.19226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Z, Malhotra PS, Thomas GR, Ondrey FG, Duffey DC, Smith CW, et al. Expression of proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines in patients with head and neck cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 1999;5:1369–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S, Xia P, Ye B, Huang G, Liu J, Fan Z. Transient activation of autophagy via Sox2-mediated suppression of mTOR is an important early step in reprogramming to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:617–25. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gavine PR, Mooney L, Kilgour E, Thomas AP, Al-Kadhimi K, Beck S, et al. AZD4547: an orally bioavailable, potent, and selective inhibitor of the fibroblast growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase family. Cancer research. 2012;72:2045–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang JY, Hsi E, Huang YC, Hsu NC, Chu PY, Chai CY. High LC3 expression correlates with poor survival in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Human pathology. 2013;44:2558–62. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang ZJ, Chee CE, Huang S, Sinicrope FA. The Role of Autophagy in Cancer: Therapeutic Implications. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2011;10:1533–41. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gewirtz DA. The Challenge of Developing Autophagy Inhibition as a Therapeutic Strategy. Cancer research. 2016;76:5610–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kihara A, Noda T, Ishihara N, Ohsumi Y. Two Distinct Vps34 Phosphatidylinositol 3–Kinase Complexes Function in Autophagy and Carboxypeptidase Y Sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;152:519–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Wang C, Tang H, Wang M, Weng J, Liu X, et al. Decrease of autophagy activity promotes malignant progression of tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 2013;42:557–64. doi: 10.1111/jop.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Balliet RM, Rivadeneira DB, Chiavarina B, Pavlides S, Wang C, et al. Oxidative stress in cancer associated fibroblasts drives tumor-stroma co-evolution: A new paradigm for understanding tumor metabolism, the field effect and genomic instability in cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3256–76. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katheder NS, Khezri R, O’Farrell F, Schultz SW, Jain A, Rahman MM, et al. Microenvironmental autophagy promotes tumour growth. Nature. 2017;541:417–20. doi: 10.1038/nature20815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fletcher EV, Love-Homan L, Sobhakumari A, Feddersen CR, Koch AT, Goel A, et al. EGFR inhibition induces proinflammatory cytokines via NOX4 in HNSCC. Molecular cancer research : MCR. 2013;11:1574–84. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagasaki T, Hara M, Nakanishi H, Takahashi H, Sato M, Takeyama H. Interleukin-6 released by colon cancer-associated fibroblasts is critical for tumour angiogenesis: anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody suppressed angiogenesis and inhibited tumour–stroma interaction. British Journal of Cancer. 2014;110:469–78. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coppe JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Munoz DP, Goldstein J, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS biology. 2008;6:2853–68. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sousa CM, Biancur DE, Wang X, Halbrook CJ, Sherman MH, Zhang L, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells support tumour metabolism through autophagic alanine secretion. Nature. 2016;536:479–83. doi: 10.1038/nature19084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg H, Xia H-g, Yuan J. Pharmacologic agents targeting autophagy. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015;125:5–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI73937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang CH, Qiu J, O’Sullivan D, Buck MD, Noguchi T, Curtis JD, et al. Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell. 2015;162:1229–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knowles LM, Stabile LP, Egloff AM, Rothstein ME, Thomas SM, Gubish CT, et al. HGF and c-Met participate in paracrine tumorigenic pathways in head and neck squamous cell cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009;15:3740–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan K-L. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–41. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sui X, Chen R, Wang Z, Huang Z, Kong N, Zhang M, et al. Autophagy and chemotherapy resistance: a promising therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e838. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sannigrahi MK, Singh V, Sharma R, Panda NK, Khullar M. Role of autophagy in head and neck cancer and therapeutic resistance. Oral diseases. 2015;21:283–91. doi: 10.1111/odi.12254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poklepovic A, Gewirtz DA. Outcome of early clinical trials of the combination of hydroxychloroquine with chemotherapy in cancer. Autophagy. 2014;10:1478–80. doi: 10.4161/auto.29428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solitro AR, MacKeigan JP. Leaving the lysosome behind: novel developments in autophagy inhibition. Future medicinal chemistry. 2016;8:73–86. doi: 10.4155/fmc.15.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.