Abstract

Herpesviruses possess a genome-pressurized capsid. The 235-kilobase genome of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is by far the largest of any herpesvirus, yet it has been unclear how its capsid, which is similar in size to those of other herpesviruses, is stabilized. Here we report a HCMV atomic structure consisting of the herpesvirus-conserved capsid proteins MCP, Tri1, Tri2, and SCP and the HCMV-specific tegument protein pp150—totaling ~4000 molecules and 62 different conformers. MCPs manifest as a complex of insertions around a bacteriophage HK97 gp5–like domain, which gives rise to three classes of capsid floor–defining interactions; triplexes, composed of two “embracing” Tri2 conformers and a “third-wheeling” Tri1, fasten the capsid floor. HCMV-specific strategies include using hexon channels to accommodate the genome and pp150 helix bundles to secure the capsid via cysteine tetrad–to-SCP interactions. Our structure should inform rational design of countermeasures against HCMV, other herpesviruses, and even HIV/AIDS.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a member of the Herpesviridae family and β-herpesvirinae subfamily, is a leading cause of congenital defects (1, 2) and a major contributor to life-threatening complications in immunocompromised individuals such as AIDS (3, 4) and organ-transplant patients (5, 6). Yet HCMV’s ability to establish relatively nontoxic lifelong latency in hosts (7), its high seroprevalence (>90% in some populations) (8), and its large genetic capacity (9) are characteristics shared among herpesviruses that together give them an advantage over other viral vectors as tools for the development of gene delivery vehicles (10), oncolytic vectors (11), and vaccines against not just herpes-viruses, but even HIV/AIDS (12, 13).

A double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) virus, HCMV’s 235-kb genome is twice the size of that of chickenpox-causing varicella zoster virus and >50% larger than that of the cold sore–causing herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) (14), two common human α-herpesviruses. Despite enclosing a much larger genome, the size of the HCMV capsid is similar to that of HSV-1 (as well as those of other herpes-viruses) (15); both have an icosahedrally ordered nucleocapsid with triangulation number (T) = 16, composed of 12 pentons, 150 hexons, and 320 triplexes. Thus, the high capsid pressure in HSV-1 (up to 20 atm) (16) resulting from tightly packed, electrostatically repulsive genomic material must be a condition further exacerbated in HCMV. Evidence from biochemical and structural studies suggests that the β-herpesvirus–specific tegument protein pp150 contributes to a netlike tegument density layer enclosing—and therefore perhaps stabilizing—the C-capsid to facilitate the formation of infectious virions (17–19).

Nonetheless, the exact mechanism through which capsid stability is achieved has remained unclear in the absence of an atomic description of HCMV particles. At more than 2000 Å in diameter, the sheer size of herpesviruses and the potential fragility associated with such large molecular assemblies present tremendous obstacles for high-resolution reconstructions (20, 21). Despite recent successes in high-resolution studies of macromolecular complexes (22–24) and smaller viruses (25–27), the highest-resolution reconstructions of α-, β-, and γ-herpesvirus particles have so far been 6.8 (28), 6 (19), and 6 Å (29), respectively—none of which are adequate for reliable de novo atomic modeling of the viral capsid. In this study, by using an improved sample preparation strategy and electron-counting cryo–electron microscopy (cryoEM), we obtained a three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of HCMV at 3.9-Å resolution and derived atomic models for the capsid and tegument protein pp150.

CryoEM reconstructions and the HCMV atomic model

CryoEM imaging with the HCMV envelope intact magnifies inherent challenges posed by low signal-to-noise ratios and a depth-of-focus gradient through specimens. On the other hand, purified HCMV capsids are intrinsically fragile and present severely reduced structural homogeneity. Neither circumstance is ideal in pursuing a high-resolution cryoEM reconstruction. To overcome these limitations, we added detergent to purified intact particles immediately before grid freezing to partially solubilize the pleomorphic viral envelope and prevent sample aggregation, thereby ensuring the preservation of capsid structures and associated tegument proteins for high-resolution cryoEM imaging.

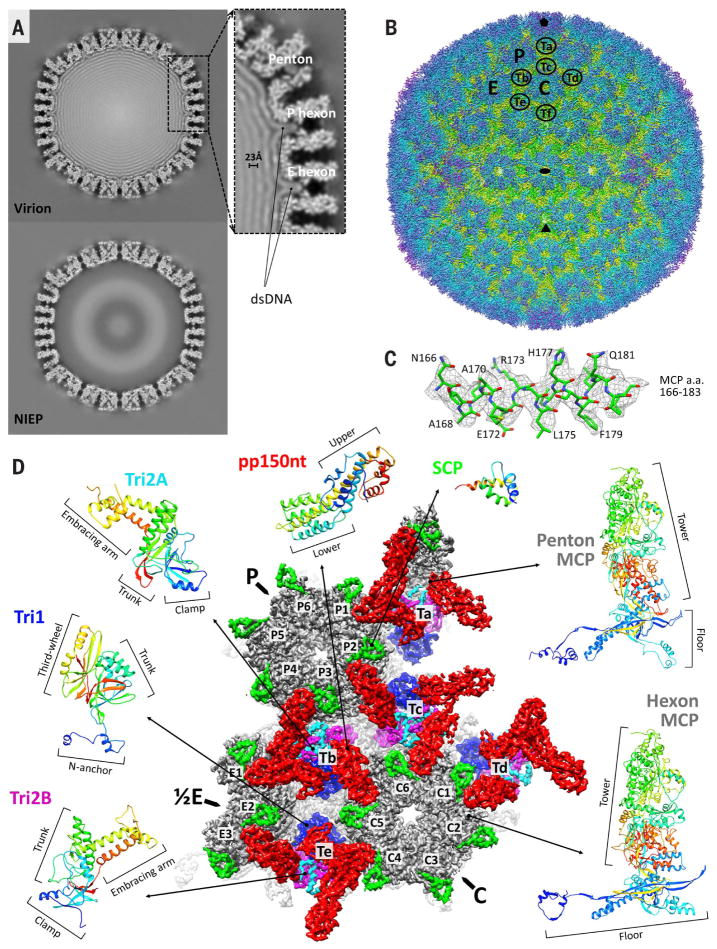

Two types of particles can be identified in the resulting images: DNA-containing and DNA-devoid, corresponding to virions and noninfectious enveloped particles (NIEPs), respectively (fig. S1). A comparison of reconstructions of these two particle types at 15-Å resolution reveals concentrically packaged dsDNA manifesting as multiple concentric density shells contoured against the inner surface of the capsid (Fig. 1A). Consistent with its markedly larger genome compared with all other human herpesviruses, HCMV’s DNA layers are more densely packed, having a ~23-Å interlayer distance versus the 25- to 26-Å spacing in HSV-1 (30) and Kaposi’s sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV, a γ-herpesvirus) (29). Unexpectedly, DNA density was observed to contour even the narrow interior confines of the capsid’s hexon channels (Fig. 1A, inset)—a feature not observed in HSV-1 or KSHV, and perhaps indicative of the space premium and massive pressures within the HCMV capsid.

Fig. 1. CryoEM reconstruction and atomic modeling of HCMV.

(A) Central slices of HCMV virion (top) and noninfectious enveloped particle (NIEP, bottom) reconstructions at 15 Å. The inset shows a 23-Å dsDNA interlayer distance and dsDNA density within hexon channels. (B) Radially colored HCMV reconstruction at 3.9-Å resolution viewed along a twofold axis. Fivefold, threefold, and twofold axes are denoted by a pentagon, triangle, and oval, respectively. P (peripentonal), C (center), and E (edge) denote hexons and Ta to Tf denote triplexes that together contribute to an asymmetric unit. (C) Density map (mesh) and atomic model of an MCP helix illustrate side chain features. A, alanine; E, glutamic acid; F, phenylalanine; H, histidine; L, leucine; N, asparagine; Q, glutamine; R, arginine; a.a., amino acids. (D) Asymmetric unit colored by protein subunit type. MCPs (gray) make up pentons and hexons. Triplexes are heterotrimers composed of Tri1 (blue) and a Tri2A (cyan)–Tri2B (magenta) dimer. SCPs (bright green) bind to all MCPs, whereas pp150 tegument proteins (red) cluster above triplexes. Rainbow ribbon models show individual proteins and conformers (blue N terminus through green and yellow to red C terminus). pp150nt, N-terminal one-third of pp150.

Next, we sought to achieve a high-resolution structure of the tegument-coated HCMV capsid. We first obtained a 4.5-Å 3D reconstruction (fig. S2, A to C) by combining 60,000 particle images collected from more than 3800 photographic films. However, we deemed the degree of confidence and coverage with which we could accurately build an atomic structure to be insufficient for our goals. We subsequently used direct electron-counting techniques (then newly introduced) to record 12,000 movies and obtained a new reconstruction at 3.9-Å resolution by combining 39,600 particle images from this data set (Fig. 1B, fig. S2C, and Movie 1). The resulting density map features well-resolved side chains consistent with this resolution (Fig. 1C and figs. S3 to S7).

Movie 1. The HCMV capsid at 3.9 Å.

A fly-in perspective of the radially colored HCMV reconstruction density map.

We then derived atomic models for all four capsid proteins that together make up the HCMV capsid shell and for the N-terminal one-third of pp150 (pp150nt), a capsid-associated tegument protein. The HCMV capsid structure is an assembly of 60 asymmetric units. An asymmetric unit contains 16 copies of major capsid protein (MCP), which account for the bulk of the protein-aceous capsid and exist in penton and hexon capsomers of five and six subunits, respectively. Hexons further exist in three subtypes, designated C (center), P (peripentonal), and E (edge) in reference to their positions relative to the capsid’s icosahedral symmetry. Each asymmetric unit contains a C hexon, P hexon, one-half of an E hexon, and one-fifth of a penton. Additionally, an asymmetric unit contains 16 copies of smallest capsid protein (SCP) that sit atop each MCP; five and one-third heterotrimeric triplexes (Ta, Tb, Tc, Td, Te, and one-third of Tf, located at the threefold axis), each composed of a triplex monomer protein Tri1 (also known as minor capsid binding protein) coupled with two dimer-forming conformers of triplex dimer protein Tri2 known as Tri2A and Tri2B (also known as minor capsid proteins); and 16 copies of pp150 molecules that cluster in groups of three above each triplex (Fig. 1B). Our atomic models accounted for all 16 conformers of MCP in an asymmetric unit, 16 conformers of SCP, five conformers of Tri1, 10 conformers of Tri2 divided between Tri2A and Tri2B, and 15 conformers of pp150nt (Fig. 1D). We were unable to model triplex Tf and its three associated molecules of pp150, because icosahedral averaging destroys the region's density as a result of symmetric mismatching at threefold axes.

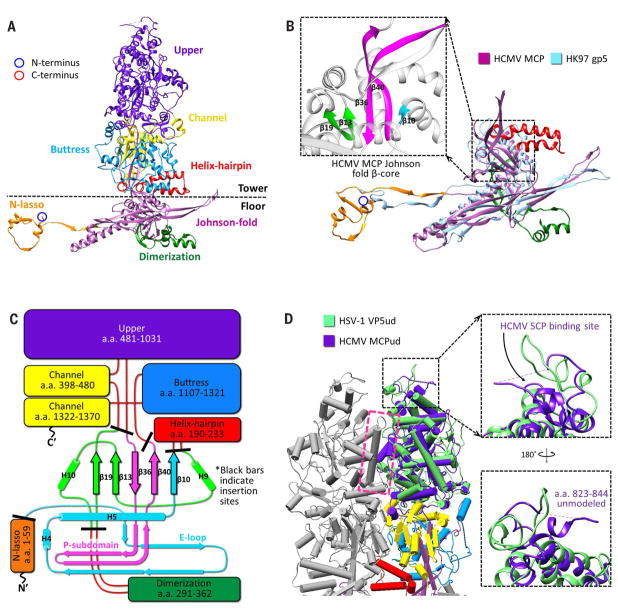

MCP structure and tower features

At 1370 amino acids in length, MCPs are enormous proteins. Each MCP is folded into seven distinct domains: upper (residues 481 to 1031), channel (398 to 480 and 1322 to 1370), buttress (1107 to 1321), helix-hairpin (190 to 233), dimerization (291 to 362), N-lasso (1 to 59), and Johnson fold (60 to 189, 234 to 290, 363 to 397, and 1032 to 1106) (Fig. 2A and Movie 2). The lattermost domain is named after a characteristic fold first identified in bacteriophage HK97 gp5 (31), later found in the major capsid proteins of other DNA bacteriophages (32, 33) and herpesviruses (34), and now modeled atomically in a herpesvirus in our HCMV MCP model (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. MCP organization and structure.

(A) Canonical hexon MCP colored and labeled by domain. N-and C-termini in ribbon models are henceforth marked with blue and red circles, respectively. (B) MCP floor region (purple) superposed with HK97 gp5 (light blue) illustrates common usage of the Johnson fold. The inset shows the MCP Johnson fold domain’s β-core, colored as in (C). (C) Schematic of MCP organization relative to a canonical Johnson fold. Black bars indicate HCMV MCP domain insertion sites. Johnson fold N-, α-, and β-elements (33) are colored cyan, green, and magenta, respectively. The E-loop and P-subdomain are contained within the N- and β-elements, respectively. H’s indicate helices. (D) Pipe-and-plank depictions of adjacent hexon MCP towers show extensive interactions at a helix-loop interface (magenta box). Superposing HSV-1 VP5 upper domain (VP5ud, green) and HCMV MCP upper domain (MCPud, purple) reveals similarities in secondary and tertiary structure, with differences pronounced at the upper SCP-binding loop regions (insets). Other colors are as in (C).

Movie 2. HCMV major capsid protein.

Atomic model of the major capsid protein colored by domain. The rainbow color scheme that initially appears progresses from the N terminus (blue) to the C terminus (red).

A prominent feature of viruses that use Johnson folds is a five-stranded β-core within the fold that serves as an organizational hub of the major capsid protein (31, 33) (Fig. 2B, inset, and fig. S8, A to F). With the exception of the N-lasso domain (itself an extension of the Johnson fold domain’s N element), all other domains of the MCP can be understood as simply modular insertions into the peripheral loops of the Johnson fold β-core (Fig. 2C). The MCP domains can further be organized into two regions: a tower region composed of the upper, channel, buttress, and helix-hairpin domains, which makes up the penton and hexon capsomer protrusions, and a floor region composed of the N-lasso, dimerization, and Johnson fold domains.

Extensive interactions exist between the tower regions of adjacent MCPs in a capsomer (Fig. 2D). Within the upper domain, the bulk of interactions occur at the interface of a long, exposed helix and a loop region from its neighboring MCP’s upper domain (Fig. 2D, magenta box), corroborating observations from the crystal structure of the HSV-1 MCP (VP5) upper domain (referred to as VP5ud), the only other herpesvirus capsid atomic structure in existence (35). A structural alignment of the VP5ud model to our HCMV MCP model’s upper domain reveals the two to be highly similar in secondary and tertiary structure, with an abundance of helices in conserved orientations. Differences are more pronounced in loop regions, in particular at the top of the upper domains where SCP binding occurs (Fig. 2D, insets).

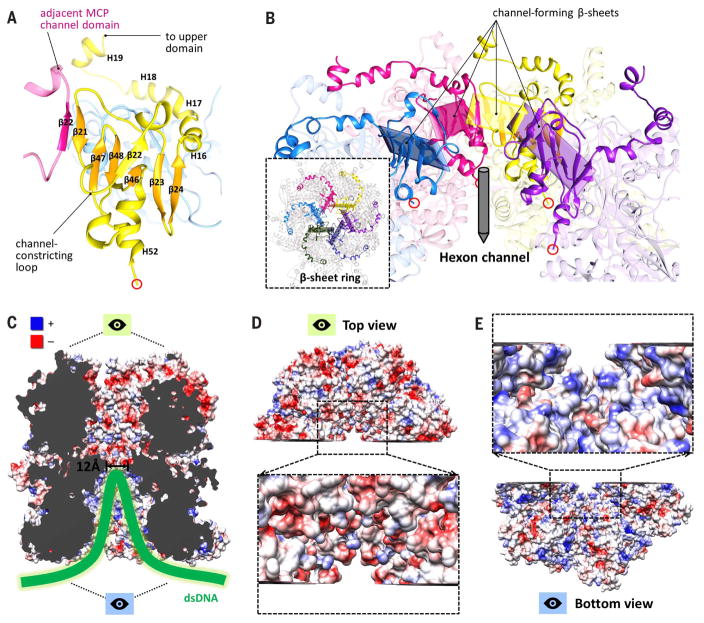

Descending the tower, the channel domain presents an interesting arrangement in hexons, where six β-strands from the channel domain of one MCP are augmented by a β-strand (β22) from an adjacent MCP’s channel domain to form a seven-stranded β-sheet angled toward the interior of the hexon channel (Fig. 3A). Together, six such β-sheets come together to form a β-sheet ring, connected by six constricting loops that descend from each β-sheet, constituting the narrowest region of the hexon channel (Fig. 3B). This “daisy chain” arrangement is possible because each constricting loop is flanked by β21 and the augmenting β22, which participates in an adjacent β-sheet. We presume that this constricted region, with an internal diameter measured at ~12 Å, is responsible for preventing DNA forced into the lower hexon channels from escaping the capsid altogether.

Fig. 3. Features of the hexon channel.

(A) β-sheet augmentations between neighboring channel domains result in six β-strands from one MCP channel domain interacting with β22 from an adjacent channel domain to form a seven-stranded β-sheet. (B) Six seven-stranded β-sheets form a daisy chain–like β-sheet ring (inset) around the hexon channel, connected by six constricting loops that define the narrowest region of the channel. (C) Electrostatic surface rendering of a clipped hexon channel. Blue and red denote positive and negative charge, respectively. (D) Top view of (C), showing that upper channel regions are predominantly negatively charged. (E) Bottom view of (C), showing that DNA-accommodating lower channel regions are predominantly positively charged.

An electrostatic surface rendering of residues lining the hexon channel further reveals a substantial difference in the properties of residues above and below the channel’s constricted region (Fig. 3C). Residues above the constriction are demonstrably more negative in charge (Fig. 3D) than residues below the constriction, which overall tend to be positively charged (Fig. 3E). This makes sense because the lower hexon channel is the DNA-accommodating region, and positive residues should accommodate the packing of negatively charged DNA better than negative residues, which would only serve to hinder packing through repulsion. These results support our interpretation of DNA-packed hexon channels as a means for HCMV to simultaneously package its large genome and alleviate extreme capsid pressure, thereby improving capsid stability.

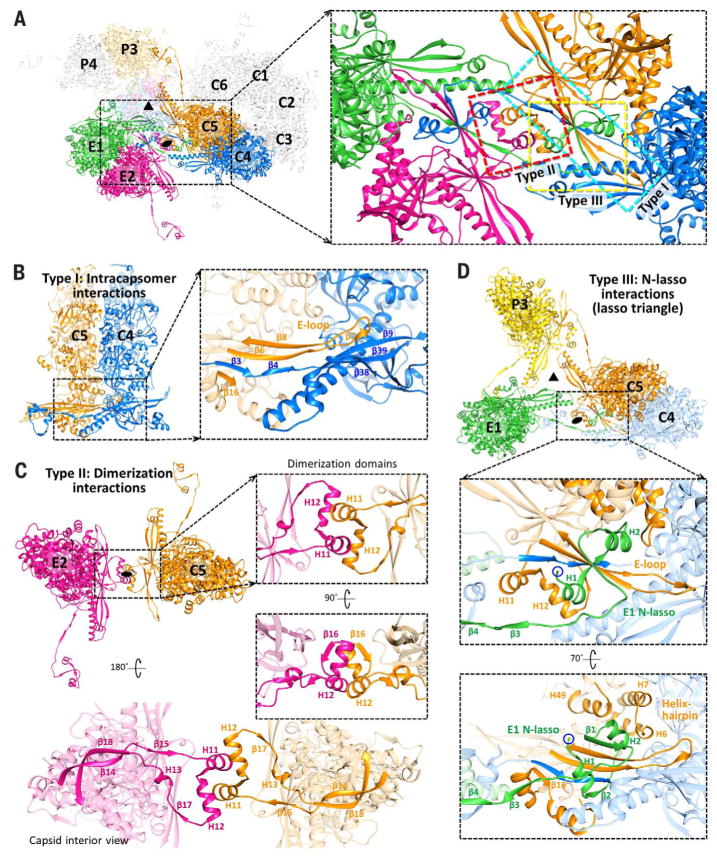

Capsid floor–defining MCP-MCP interactions

Within the floor region, three notable types of MCP-MCP interactions contribute to the structural integrity of the HCMV capsid shell (Fig. 4A). Type I interactions are intracapsomer interactions that occur between adjacent MCPs within a capsomer and are dominated by two sets of β-sheet augmentations. An archetypal type I interaction is illustrated between C4 and C5 MCPs in Fig. 4B. β-strands from C5’s dimerization domain (β16) and the E-loop of its Johnson fold domain (β6 and β8) are joined by two β-strands from C4’s N-lasso domain (β3 and β4) to form a five-stranded β-sheet. Similarly, a β-strand from C5’s E-loop (β7) joins three β-strands from C4’s E-loop (β9) and Johnson fold domain’s P-subdomain (β38 and β39) to form a four-stranded β-sheet. Conversely, type II interactions are intercapsomer dimerization interactions that feature quasi-equivalent interactions between two pairs of helices in the dimerization domains of MCPs across local twofold axes. Type II interactions are illustrated by E2 and C5 MCPs (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4. Three classes of capsid floor–defining interactions.

(A) Overview of MCPs from C, E, and P hexons. Local threefold (triangle) and twofold (oval) axes are indicated. The inset shows the three major types of MCP-MCP interactions (boxed), subsequently illustrated in detail. (B) Intracapsomer interactions (type I) occur between adjacent MCPs within a capsomer and consist of two sets of floor region β-sheet augmentations (inset). (C) Dimerization interactions (type II) are intercapsomer interactions that occur between MCP dimerization domains across a local twofold axis. Insets show quasi-equivalent helix interactions between two dimerization domains. (D) N-lasso (type III) interactions are facilitated by an MCP N-lasso (green) that extends and lashes around the E-loop (orange) and N-lasso neck (blue) of two MCPs located diagonally across a local twofold axis (upper inset). Three pairs of N-lasso interactions form an enclosed lasso triangle around the local threefold axis. E1’s N-lasso also augments the existing β-sheet from C5 and C4’s type I interaction to form a seven-stranded β-sheet complex (lower inset). Helices from C5’s helix-hairpin (H6 and H7) and buttress (H49) domains form a helix bundle with E1 N-lasso’s H2, further securing E1’s N-lasso.

Unlike type I and II interactions, type III interactions occur among three MCPs and are characterized by the lassoing action of the N-lasso domain, which extends out and lashes around an E-loop and an N-lasso neck from two MCPs located diagonally across a local twofold axis. Three sets of N-lasso interactions form an enclosed triangle around local threefold axes, creating a “lasso triangle.” E1, C4, and C5 MCPs illustrate a type III N-lasso interaction, and E1, C5, and P3 MCPs illustrate the lasso triangle (Fig. 4D). E1’s N-lasso encircles C5’s E-loop and the neck of C4’s N-lasso, both of which also participate in type I interactions. In addition to lashing these two elements, E1’s N-lasso also contributes two β-strands (β1 and β2) that augment the existing five-stranded β-sheet from C4 and C5’s type I interaction to form a seven-stranded β-sheet complex (Fig. 4D, lower inset). Thus, type III interactions build on and likely lend increased stability to type I intracapsomer interactions. Lastly, a small helix bundle formed from E1 N-lasso’s helix H2, two helices from C5’s helix-hairpin domain (H6 and H7), and a helix from C5’s buttress domain (H49) further secure the E1 N-lasso in place.

MCP adaptations at the fivefold axis

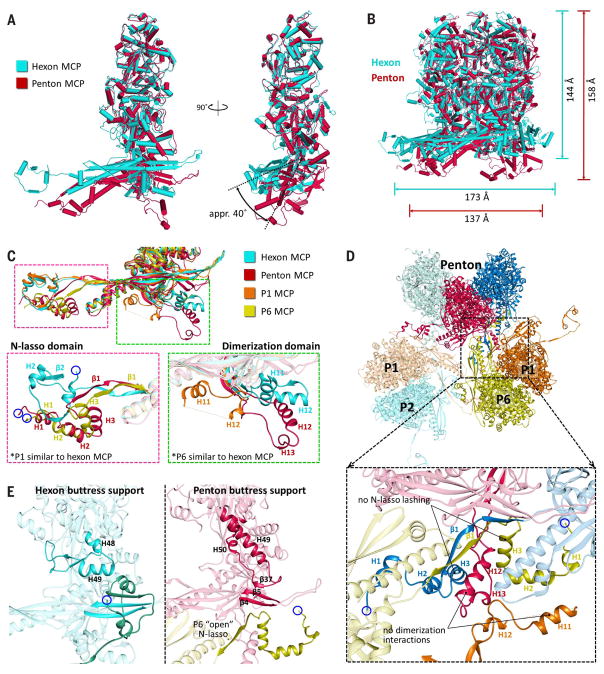

MCPs adjust to variations in capsid geometry at fivefold vertices by adopting conformational changes. A comparison of hexon and penton MCPs reveals a contracted and rotated penton MCP floor region relative to that of hexon MCP, whereas their tower regions are highly similar (Fig. 5A). Pentons thus have a more “closed umbrella” shape in comparison with hexons and accordingly have a smaller diameter but greater height (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. MCP adaptations at the fivefold axis.

(A) Superposing hexon MCP (teal) and penton MCP (burgundy) reveals a contracted and rotated penton MCP floor region relative to hexon MCP. (B) Superposing hexons and pentons reveals that pentons have a more “closed umbrella” shape relative to hexons. (C) Superposed canonical hexon MCP, penton MCP, P1, and P6 reveal similar floor regions with differences at the N-lasso and dimerization domains. Penton MCP and P6 adopt an “open” N-lasso conformation (magenta inset), whereas penton MCP and P1 adopt distinctive extended conformations of the dimerization domain (green inset). (D) Overview of penton, P1, P2, and P6 MCPs. The inset demonstrates how, because of local geometry changes near the fivefold axis, penton MCPs participate in neither N-lasso lashing nor dimerization interactions with surrounding hexon MCPs. (E) Comparison of buttress supports of hexon and penton MCP buttress domains. A hexon buttress support, akin to a flexed elbow, contains two helices that support the MCP tower and clamps a neighboring MCP’s N-lasso (left). Penton MCPs are not lashed by P6’s open N-lasso; a penton buttress support extends its elbow to form a long helix reaching to the MCP floor, where it contributes β37 to the floor’s E-loop β-sheet complex while supporting the penton tower (right).

In addition to differences in domain orientation, penton MCPs also exhibit several notable local conformation changes. Specifically, the penton MCP N-lasso adopts an “open” configuration, effectively eliminating its lassoing ability (Fig. 5C, magenta insets), whereas the dimerization domain exists in an extended configuration that differs from the compact fold of its canonical hexon counterpart (Fig. 5C, green insets). As such, the penton MCP neither lashes an adjacent P1 (hexon) MCP, nor does it establish quasi-equivalent interactions with a (different) P1 MCP’s dimerization domain (which itself also adopts a distinctive configuration). The P6 (hexon) MCP, whose N-lasso would normally lash a penton MCP in a traditional lasso triangle, adopts an open N-lasso as well. Thus, pentons neither lash adjacent hexons, nor are they lashed by adjacent hexons, nor do they participate in dimerization interactions with surrounding hexons (Fig. 5D). This lack of type II and III interactions at pentons likely accounts for the documented vulnerability of pentonal vertices in herpesvirus capsids (36, 37).

Lastly, in the absence of a canonical P6 N-lasso and type III interactions to stabilize the penton MCP floor’s type I β-sheet complex, an element that we term the “buttress support” from MCP’s buttress domain provides reinforcement. In hexon MCPs, the buttress support consists of two helices (H48 and H49) and a flexible loop region, and it acts as a flexed “elbow” resting on a neighboring MCP’s N-lasso (Fig. 5E, left panel), so that it serves as both a clamp for the N-lasso and a structural support for the MCP tower. In penton MCPs, the elbow is extended as the two helices combine into a long helix (H49) that reaches down to the floor of the penton MCP (Fig. 5E, right panel), where it contributes β37 to type I β-sheet interactions. There, β37’s augmentation with the penton MCP floor enhances type I β-sheet interactions in the absence of a lashing canonical N-lasso from P6 and simultaneously cements the lower end of the buttress support to the MCP floor, thereby facilitating additional structural propping of the penton tower.

Triplex structure and roles in capsid architecture

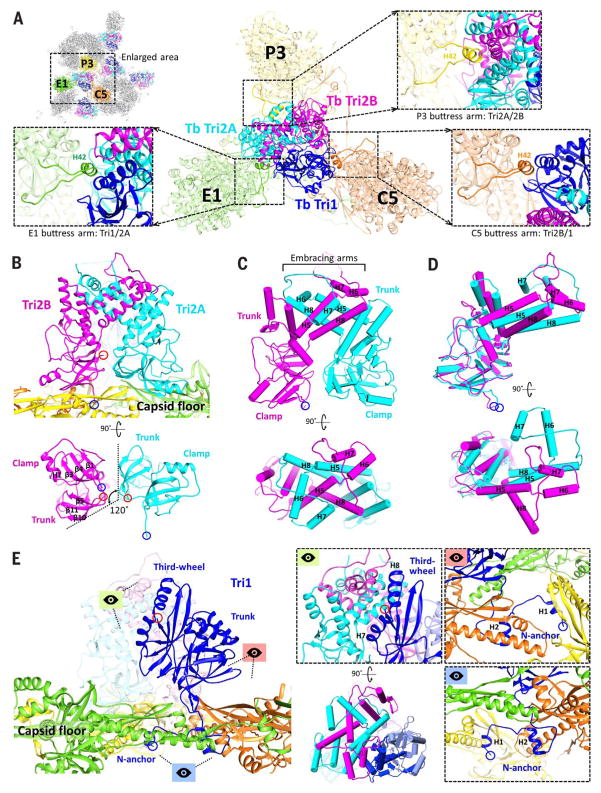

Triplexes are heterotrimers consisting of two dimer-forming Tri2 protein conformers, Tri2A and Tri2B, coupled with a Tri1 protein (Movie 3). Triplexes sit atop the MCP N-lasso triangle (Fig. 6A) and play an important role in the capsid’s architecture by plugging the large voids in the capsid floor between capsomers.

Movie 3. HCMV triplex proteins.

An overview of Tri1, Tri2A, and Tri2B, including a comparison of Tri2A and Tri2B, and an illustration of how the heterotrimeric triplex is composed from its constituent proteins. The rainbow color scheme that appears temporarily for each protein progresses from the N terminus (blue) to the C terminus (red).

Fig. 6. Triplex structure and interactions with MCP.

(A) Overview of Tb triplex and its surrounding MCPs. Insets show MCP buttress arms that clamp the upper junction regions of the triplex proteins. (B) Tri2A and Tri2B form dimers that interact closely with the capsid floor. Their bottom views reveal similar clamp and trunk domain footprints, albeit rotated 120° about each other. (C) Pipe-and-plank depictions of Tri2 dimer in profile and top views, illustrating the helix bundle formed from the embracing arm domains of Tri2A and Tri2B. (D) Superposing Tri2A and Tri2B reveals nearly identical clamp and trunk domains but highlights conformational differences in their embracing arms. (E) Tri1’s main mass exhibits little contact with the capsid floor compared with Tri2 dimer. Instead, Tri1 secures Tri2 dimer to the capsid through a latch-and-anchor function. Tri1’s third-wheel domain wedges into Tri2’s embracing arms, latching Tri1 to Tri2 dimer (green perspective; the pipe-and-plank depiction shows this at a rotation of 90°). Meanwhile, Tri1’s N-anchor penetrates the capsid floor to anchor the complete triplex to the capsid shell (red and blue perspectives).

Both conformers of Tri2 exhibit three domains: clamp (residues 1 to 88), trunk (89 to 187 and 286 to 306), and embracing arm (188 to 285), which are named to reflect their structural roles in the triplex (Fig. 1D). Clamp domains are the primary elements through which the Tri2 dimer establishes contact with the floor regions of adjacent capsomers (Fig. 6B). In doing so, the Tri2 dimer reinforces MCP-MCP interactions in the vicinity of the lasso triangle. Trunk domains are structural elements whose key role is to support the helix-laden embracing arm domains, through which Tri2A and Tri2B “embrace” each other to form a large helix bundle that clasps the Tri2 dimer together (Fig. 6C). Superimposing Tri2A and Tri2B reveals that their clamp and trunk domains are nearly identical, whereas their embracing arms exist in markedly different spatial configurations (Fig. 6D).

Tri1 similarly has three domains, including an N-anchor (residues 1 to 44), trunk (45 to 168), and “third-wheel” (169 to 290) domain (Figs.1D and 6E). But whereas Tri2A and Tri2B have clamp domains that interact extensively with the floor regions of surrounding MCPs, the bulk of Tri1 exhibits considerably less contact with the capsid floor. Instead, Tri1 functions largely as a latch-and-anchor protein that secures the Tri2 dimer in place. In keeping with our imagery, Tri1’s third-wheel domain wedges its helices into the helix bundle formed from Tri2 dimer’s embracing arms, thereby latching Tri1 to the dimer (Fig. 6E, green perspective). Meanwhile, Tri1’s N-anchor penetrates the capsid floor and extends along the inner surface of the capsid shell, anchoring Tri1 and, by extension, the entire triplex to the capsid floor (Fig. 6E, red and blue perspectives). Lastly, the extensive triplex-MCP interactions at the capsid floor are complemented topside by three helix-containing buttress arms that extend from the buttress domains of three adjacent MCPs (Fig. 6A, insets). These rest on the triplex, further clamping the triplex in place while creating an additional point of support for their respective MCP towers.

In the greater context of the capsid’s global structure, the triplex forms the centerpiece of the lock unit, which is a conceptual means of encompassing the complete set of intricate molecular interactions found within the HCMV capsid. Each lock unit is composed of six MCPs from three different capsomers and features three pairs of type I interactions, three pairs of type II interactions, and one lasso triangle—all organized around a triplex that not only reinforces MCP-MCP interactions about the lasso triangle, but also plugs what would otherwise be a large perforation in the capsid floor at local threefold axes (fig. S9A and Movie 4). Six lock units interact in overlapping fashion to constitute a group of six (GOS), at the center of which sits a hexon (fig. S9B). Because each MCP is included in two lock units and directly interacts with four lock units including its own, each lock unit interacts with all lock units in its GOS except the far opposite unit. GOSs overlap so that each lock unit takes part in the makeup of three GOSs, allowing an individual lock unit to interact directly with nine distinct lock units (fig. S9C). From a global perspective, lock units are a capsid organizational schema that helps illustrate the highly interwoven nature of the structural proteins that come together to constitute the HCMV capsid.

Movie 4. Interactions of the HCMV lock unit.

An overview of the three classes of MCP-MCP interactions that characterize the capsid floor and the role of the triplex in securing the capsid floor. Purple, yellow, red, orange, pink, and green indicate hexon MCPs. Blue, cyan, and magenta indicate triplex proteins.

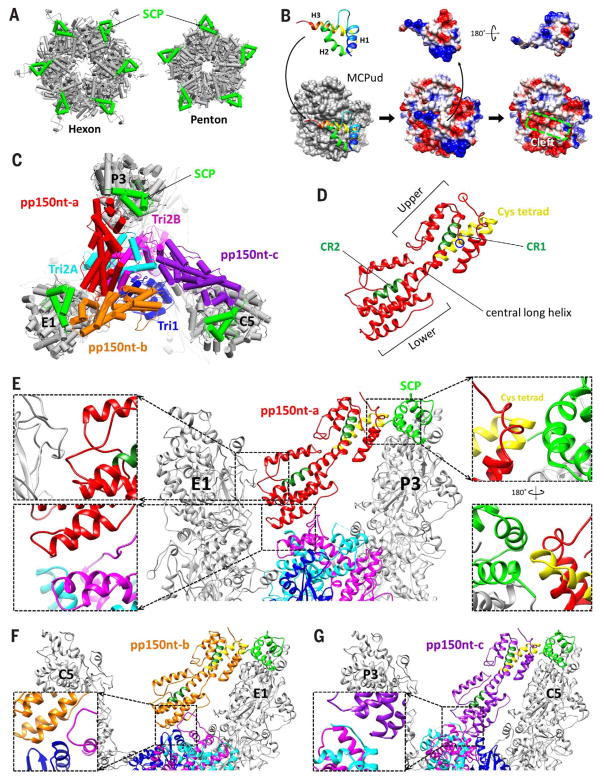

SCP structure and interactions with MCP

The 75–amino acid UL48.5 gene product known as the SCP is the smallest of the HCMV capsid proteins and also the smallest of all its functional homologs in human herpesviruses. Unlike in HSV-1, where SCPs bind only hexon MCPs (38), SCPs in HCMV bind both penton and hexon MCPs so that each MCP is bound by exactly one SCP. Both penton and hexon SCPs exhibit nearly identical globular structures, and both sit atop MCP upper domains at the outer circumference of their respective capsomers, exhibiting similar interactions with their underlying MCPs (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7. SCP and securing tegumental pp150 to the capsid.

(A) SCPs (bright green) ring the outer circumference of both hexon and penton capsomers. (B) SCP interacts with the underlying MCPud primarily through SCP’s C-terminal helix and loop (left). Electrostatic potential surfaces of SCP (center and right), SCP-bound MCPud (center), and MCPud (right) reveal a shallow cleft atop MCPud (green box) into which SCP inserts. (C) Three pp150 conformers—pp150nt-a (red), pp150nt-b (orange), and pp150nt-c (purple)—cluster on each triplex and extend toward the SCPs atop nearby MCPs, shown here at Tb triplex. (D) Ribbon model of pp150nt, showing that it is organized into upper and lower helix bundles. Green residues denote β-herpesvirus–conserved regions CR1 and CR2, and yellow residues denote the primate CMV–conserved cysteine (cys) tetrad. (E to G) Profile views of the interactions of pp150nt-a, -b, and -c with capsid proteins, respectively. Interactions between pp150nt-a’s upper end and the capsid occur through a cysteine tetrad–to-SCP interaction [(E), right insets], which is maintained in all conformers. Interactions between pp150nt’s lower end and the capsid vary among conformers. pp150nt-a’s lower end interacts with a neighboring MCP’s tower [(E), top left inset] and underlying Tri2A and Tri2B [(E), bottom left inset], whereas the lower ends of pp150nt-b and pp150nt-c interact exclusively with Tri1 and Tri2B [(F), inset] and Tri2A and Tri2B [(G), inset], respectively.

Our modeling efforts successfully resolved 63 of the 75 amino acids of SCP (residues 13 to 75), revealing a structure characterized by three helices connected by short loops (Fig. 7B). In all SCP copies in our density map, the density for residues 1 to 12 degrades from highly disordered to completely invisible toward the N terminus, suggesting that this fragment is inherently flexible—and thus not resolved in cryoEM structures obtained by averaging tens of thousands of individual viral particles. Indeed, a previous mutagenesis study of HCMV SCP found that the deletion of residues 1 to 11 had no effect on SCP binding to MCP (39). The same study also found residues 56 to 75 to be required for SCP-to-MCP binding. This is consistent with our results, which show that SCP’s H3 (residues 57 to 72) and C-terminal loop (residues 73 to 75) serve as the main interacting residues between SCP and MCP, inserting into a shallow cleft in the MCP upper domain (Fig. 7B, green box).

Tegumental pp150 structure and capsid binding

Three pp150 molecules—conformers a, b, and c—cluster on each triplex and extend toward the top of three nearby MCPs, contributing to the netlike layer of tegument densities that enmesh HCMV capsids (Fig. 7C). The atomic model constructed for pp150nt (the N-terminal one-third of pp150, residues 1 to 285) confirms that it is predominantly helical (19), with a series of roughly parallel helices arranged in upper and lower bundles joined by a central long helix (Fig. 7D). The remainder of pp150 was invisible in our reconstructed density map, again suggesting that the region exhibits flexibility and/or lacks a fixed orientation, which is consistent with data showing that pp150’s N-terminal residues 1 to 275 alone are sufficient for pp150-to-capsid binding (17). Several conserved regions in the N-terminal 275 residues have also been identified, including a 27–amino acid cysteine tetrad conserved across all primate CMVs and two regions known as conserved regions 1 and 2 (CR1 and CR2) that are conserved among β-herpesviruses (17). Our model reveals the cysteine tetrad and CR1 to be in pp150nt’s upper helix bundle, whereas CR2 is in the lower helix bundle (Fig. 7D and fig. S10, A and B).

Interactions between pp150nt and the capsid occur at pp150nt’s upper and lower ends and reveal how pp150 works to secure the HCMV capsid (Fig. 7E and Movie 5). At the upper end, all three conformers of pp150nt rest primarily on the SCPs of nearby MCPs in identical fashion through a maintained cysteine tetrad–to-SCP interaction (Fig. 7E, right insets). In contrast, interactions that cement the lower end of pp150nt to the capsid are far less specific and differ among conformers, as necessitated by the fact that pp150’s underlying triplex does not exhibit perfect threefold symmetry. At most triplexes, the lower end of pp150nt conformer a (pp150nt-a) interacts with Tri2A, Tri2B, and the side of an adjacent MCP’s upper domain (Fig. 7E, left insets), whereas the lower ends of pp150nt-b and pp150nt-c interact exclusively with Tri1 and Tri2B (Fig. 7F) and Tri2A and Tri2B (Fig. 7G), respectively. Consistent with the higher degree of interaction specificity at the upper end, pp150nt’s upper helix bundle contains more conserved elements in CR1 and the cysteine tetrad and exhibits greater structural uniformity across the three pp150nt conformers than the lower helix bundle (fig. S10C). Interestingly, although CR2 is in the lower helix bundle, its location is on the central long helix that forms part of the upper helix bundle and on which 18 residues of the cysteine tetrad are also found.

Movie 5. Interactions of HCMV tegument protein pp150 and capsid.

An overview of pp150nt’s upper- and lower-end interactions with capsomer protrusions and the underlying triplex, respectively. Variations in pp150nt lower-end interactions with the underlying triplex are shown for different pp150nt conformers.

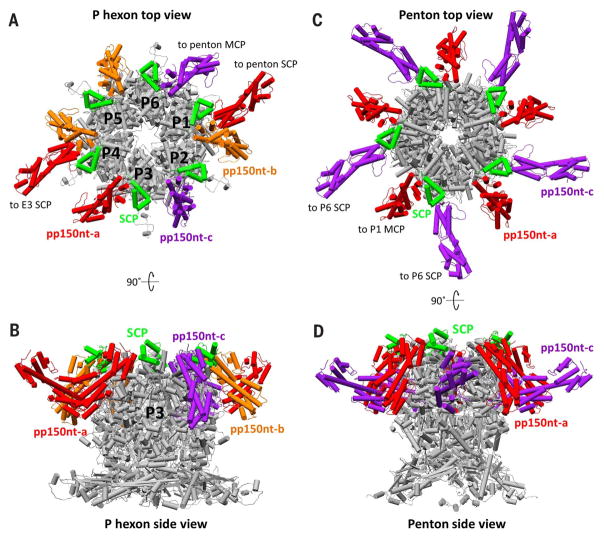

Although the lock unit is a concept readily applicable throughout the herpesviruses, pp150 in HCMV seems to be an adaptation that specifically allows HCMV to cope with the pressure of its exceptionally large genome. Whereas other human herpesviruses exhibit auxiliary tegument proteins that bind exclusively to pentons and peripentonal triplexes [UL17 and UL25 in HSV-1 (30, 40, 41) and ORF32 and ORF19 in KSHV (42)], pp150 is globally bound to all capsomers and triplexes in HCMV. We posit this as consequence of the fact that HSV-1 and KSHV, possessing high capsid pressures but smaller genomes, can manage with structural reinforcements limited to their pentonal vertices, which we demonstrated lack both type II dimerization and type III N-lasso lashing interactions. Indeed, atomic force microscopy studies of HSV-1 have shown that UL25 binding at pentons considerably increases the mechanical stiffness of the capsid (43). But the vastly greater pressures in HCMV that result from a similar-sized capsid containing a substantially larger genome occupying every last cubic angstrom of space—as evidenced by smaller DNA interlayer distances and DNA-filled hexon channels—require more robust methods to stabilize the capsid than simply penton reinforcement, necessitating the recruitment of pp150 at hexons as well (Fig. 8, A to D). Our structures reveal the specific nature of SCP’s role in pp150’s recruitment, illustrating how pp150nt binds capsomer protrusions through a well-defined cysteine tetrad–to-SCP interaction, which incidentally accounts for why pp150 loss-of-function HCMV mutants can be rescued by pp150 from primate CMV (in which cysteine tetrad is conserved), but not from nonprimate CMV (44). Thus, the strengthening of the DNA-containing capsid by pp150 relies on its interaction with a mediator protein that has no apparent structural role itself and is the least conserved capsid protein across Herpesviridae subfamilies—the 8-kDa HCMV SCP.

Fig. 8. Hexon and penton stabilization by pp150nt.

(A) Top view of a P hexon and its interacting SCP and pp150nt molecules, showing that a P hexon is stabilized by eight copies of pp150nt. (B) Side view of (A). (C) Top view of a penton and its interacting SCP and pp150nt molecules, showing that a penton is stabilized by 10 copies of pp150nt. In addition to the five pp150nt molecules associated with each penton SCP, five pp150nt-c molecules from five surrounding P6 SCPs also interact with each penton MCP. These peripentonal pp150nt-c conformers represent a special case normally seen only with pp150nt-a, where the lower helix bundle interacts directly with an MCP tower in addition to an underlying triplex. (D) Side view of (B).

Discussion

Like herpesviruses, dsDNA bacteriophages contain tightly packaged genomes and are highly pressurized, often with capsid internal pressures in the tens of atmospheres (45, 46). Both classes of virus inject their genomes into host cells by using a pressure-driven DNA ejection strategy, despite likely billions of years of evolution separating eukaryotic viruses and bacteriophages (16). Likewise, maintaining capsid structural integrity under such pressured conditions is a common challenge faced by herpesviruses and dsDNA bacteriophages, and the solution is necessarily an architectural one. Since the Johnson fold was first discovered in bacteriophage HK97 (31), many dsDNA viruses have been found to use the fold as a core structural motif, though often with elaborations—presumably to enhance capsid stability—that seem to correlate in complexity with the physical size and organizational complexity of the virus (47). In some viruses, these elaborations manifest as domains that insert into the Johnson fold, as exemplified by phage P22 (48). Others, such as lambda phage, recruit an auxiliary protein to stabilize the capsid (49). Among viruses whose atomic structures are known, HK97 represents perhaps the most optimized solution, achieving a highly stable capsid through covalent bonds cross-linking a simple MCP that is merely 282 amino acids in length (31). The HCMV structure presented here contributes an example at the other extreme: a 1300-Å-diameter capsid with T = 16 icosahedral symmetry that uses (i) an enormous 1370–amino acid MCP consisting of six domain insertions elaborating the archetypal Johnson fold to establish the capsid’s basic chassis, (ii) auxiliary triplex heterotrimers to stabilize its MCP floor, and (iii) a network of helix bundles from the auxiliary tegument protein pp150 to further secure its outmost regions.

Beyond providing a framework to understand mechanisms of capsid stabilization in the large family of herpesviruses in general and HCMV in particular, the HCMV atomic structures presented here also hold promise for the rational design of therapeutic strategies. Since the 1970s, tremendous efforts have been invested in the development of live-attenuated HCMV vaccines, with little success. Our structure should allow a more precise, structure-based mutagenesis approach in developing effective live-attenuated mutants suitable for vaccination against HCMV and potentially other herpesviruses. Additionally, recent studies have shown rhesus cytomegalovirus to be effective as a persistent vector in not just controlling but clearing simian immunodeficiency virus in rhesus macaques (12, 13). These ground-breaking advances have inspired researchers to develop vaccines against HIV by using an analogous strategy. Because wild-type HCMV cannot be used as a vector for HIV vaccine development given its virulence, the central issue of this approach is the construction of appropriate live-attenuated HCMV vectors. The HCMV atomic model should prove invaluable in this effort. These findings thus will have profound impacts on the development of new strategies for therapeutic intervention against both HCMV and HIV infections.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

Human fibroblast MRC-5 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were infected with HCMV strain AD169 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 to 0.5 when cells reached ~80 to 100% confluence. At 7 days postinfection with roughly 80% of the cells lysed, the culture media was collected and centrifuged at 10,000g for 12 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was collected and then centrifuged at 80,000g for 1 hour to pellet HCMV particles. The pellet was resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (10mM PBS, pH 7.4) and further purified by centrifugation through a 15 to 50% (w/v) sucrose gradient at 100,000g for 1 hour. The light-scattering band of virus particles was collected, diluted with PBS, and then pelleted at 80,000g for another hour.

HCMV particles (virions and NIEPs) have a pleomorphic viral envelope and a particle diameter ranging from 2000 to 3000 Å, which presents a problem in obtaining thin enough samples when preparing cryoEM grids (see Ewald sphere curvature “depth of focus” problem below). Since the pleomorphic envelope and the majority of nonordered tegument proteins it envelops manifests as noise and increased thickness in our single-particle cryoEM reconstruction of the nucleocapsid, it is desirable to remove them before preparing the cryoEM grids. Thus, to reduce both noise and viral particle size while still maintaining nucleocapsid integrity, we added NP-40 detergent at a 1% final concentration to purified intact HCMV particles to partially solubilize the viral envelope (fig. S1). Immediately after, aliquots of 2 μl of this treated sample were transferred to Quantifoil grids (2/1), which had previously been baked overnight by exposure to a strong electron beam. The grids were then blotted for 20 s in an FEI vitrobot with 100% humidity and plunged into liquid ethane. Sample-containing grids were subsequently kept in liquid nitrogen storage.

CryoEM imaging

CryoEM imaging was performed with an FEI Titan Krios electron microscope operated at 300 kV and liquid nitrogen temperature, using the image acquisition software Leginon (50, 51). Before cryoEM data collection, the electron microscope was carefully aligned to minimize beam tilt with coma-free alignment. Note that our project was begun in 2011 when direct electron-counting technology was not yet commercially available. For this reason, cryoEM data recorded on both photographic films and a direct electron detector was used in our effort to obtain a reconstruction of sufficient resolution for atomic model building.

The initial set of cryoEM images were recorded on Kodak SO163 films with a dosage of ~25 e−/Å2 at 47,000× nominal magnification and defocus values between 2.0 and 2.5 μm. A total of 3800 films were recorded and digitized using Nikon Super CoolScan 9000 ED scanners at 6.35 μm per pixel (corresponding to 1.351 Å per pixel at the sample level). Magnification was calibrated using a catalase crystal sample, giving a specimen pixel size of 1.39 Å per pixel. Despite tremendous effort and time invested, we were only able to push the resolution to 4.5 Å from this initial set of film data.

When the direct electron-counting camera eventually became available (52), we decided to take advantage of this cutting-edge technology to record a second set of cryoEM data. Movies from this set were recorded using a Gatan K2 Summit direct electron detection camera operated in counting mode at a nominal magnification of 18,000×. Using a catalase crystal sample, the magnification was calibrated to 31,120×, giving a pixel size of 1.61 Å per pixel on the specimen. The dose rate of the electron beam was set to ~7 electrons per physical pixel per second on camera, giving a corresponding dosage of ~2.7 e−/Å2/s on specimen. Image stacks were recorded at 4 frames per second (giving a per frame dose rate of 1.75 e− per physical pixel) for 14 s, and a total of 12,000 movies were ultimately captured from two grids from a whole month of imaging.

Image processing and 3D reconstruction

From the over 3800 micrograph films of cryoEM images we obtained and manually scanned—a laborious process that took hundreds of man hours—defocus values and astigmatism parameters for each micrograph were determined using CTFFIND (53). Individual particle images (1280 × 1280 pixels) were boxed out automatically using the autoBox program in the IMIRS package (54), then checked manually using the boxer program in EMAN (55) to keep only well-separated, artifact-free particles. With the resulting 60,000 particle images, each individually screened, we proceeded to obtain a reconstruction of the HCMV particle at 4.5-Å resolution (fig. S2, A to C) with IMIRS. Building reliable atomic models at this resolution for capsid proteins as complex as those found in HCMV proved to be difficult. Thus, despite our 4.5-Å reconstruction being the highest resolution yet of a herpesvirus, and despite the sheer effort it took to obtain this reconstruction, we desired to push an even higher resolution with the end goal of producing higher fidelity atomic models.

For the movies obtained via direct electron counting from our second imaging session, drift correction was carried out between frames in each image stack using the UCSF software suite (52). Two types of final images were produced. The first type, with a total dose of ~40 e−/Å2, was generated by merging all frames (56 frames) of each image stack together. These were used for the determination of defocus values and astigmatism parameters, again with the program CTFFIND. The second type, with a total dose of ~24 e−/Å2 and used to carry out further data processing, was generated by merging the first 36 frames of each image stack. From the 10,264 movies ultimately processed, a total of 50,500 particle images (1024 × 1024 pixels) were selected, once again using autoBox from IMIRS initially and then checked manually in EMAN. From these particle images, initial particle orientation and center parameters were determined, and using IMIRS, the initial 3D reconstruction was obtained, computed using a graphics processing unit (GPU) set-up running eLite3D (56). Projection models obtained from the initial reconstruction were then used to refine initial particle orientation and center parameters to produce improved 3D reconstructions. After multiple iterative refinements in which astigmatism in the CTF correction was incorporated at each iteration, we achieved a final reconstruction with a resolution of 3.9 Å, obtained from 39,600 particles (Fig. 1, B and C). The effective resolution of our map was assessed with the 0.5 criterion of the reference-based Fourier shell correlation (FSC) coefficient (Cref = 0.5 or FSC = 0.143), as defined by Rosenthal and Henderson (57) (fig. S2C). Lastly, the map was deconvolved by a temperature factor of 100 Å2 to enhance higher resolution features, and the final reconstruction was filtered to 3.9-Å resolution by low pass filtering with a cosine-shaped cutoff of 11 Fourier pixels (full width at half max). To further evaluate our map quality, a local resolution map was produced for the density surrounding an asymmetric unit using ResMap (58) (fig. S3).

On a related note, the large number of particle images required to produce our 3.9-Å reconstruction is a result of what is known as the Ewald sphere curvature (or “depth of focus”) problem. Essentially, the Fourier transform of a cryoEM image corresponds to the sum of the Fourier values on two spheres in reciprocal space (59, 60), but most reconstruction methods, including IMIRS used here, are based on the Central Projection Theorem, which assumes that the two spheres are flat, as a single degenerated central section of the 3D Fourier transform of the original object. Such treatment imposes a resolution limit in resulting 3D reconstructions if the particles do not have rotational symmetry (such as ribosomes). As this limiting effect is a function of both electron voltage and particle size (sample thickness) (60, 61), our use of a 300-kV accelerating voltage helped alleviate the problem somewhat, but the colossal ~2000-Å particle size of HCMV remained a sizeable hurdle. Fortunately, in the presence of rotational symmetry, as is the case in our study with an icosahedral virus, the limiting effect can be gradually removed by imposing symmetry during 3D reconstruction. This utilizes structural information near the central region of the particle (i.e., “good” information) to average out the compromised structural information contributed by the top and bottom of the particle (i.e., “bad” information) beyond the depth of focus of the microscope, where the effects of Ewald sphere curvature are the greatest. For this reason, the net result of ignoring the effects of Ewald sphere curvature in large icosahedral virus reconstructions is similar to introducing an additional envelope damping function (i.e., the so-called “B-factor”) to high-resolution structural information. Indeed, as shown in our study, the total number of particle images needed for near-atomic resolution structural determination is considerably increased, despite recording particle images with a direct electron-counting camera, which yields a relatively high signal-to-noise ratio.

Atomic-model building, refinement, and 3D visualization

Our initial attempts to atomically model HCMV using the first 4.5-Å reconstruction were met with enormous obstacles and resulted in mixed success. The main challenge lay in density quality, which progressively deteriorated at larger radii from the capsid center. Whereas large side chains were fairly well-resolved in MCP floor regions as distinct density protrusions from the main chain (fig. S2B), smaller side chains were sometimes indistinguishable from the main chain’s Cα bumps, and much less from each other. This condition was only exacerbated moving up toward the MCP tower regions. Furthermore, main chain density was often compromised, frequently appearing broken or “branched” in instances, giving an illusion of multiple possible main chain traces. Nevertheless, when it became apparent that 4.5 Å was to be the maximum attainable resolution of our initial film-based reconstruction, we began what would become a year-long effort of modeling with the 4.5-Å map.

In determining the main chain traces of the capsid proteins, we used EMAN to produce several versions of density maps filtered with different B-factors showing local regions around our target proteins. Maps were filtered to either better show low density threshold features (i.e., side chain densities) at the expense of main chain connectivity, or to better emphasize main chain connectivity at the expense of finer features. As automated Cα-building programs were out of the question for a map of this resolution, we utilized the Marker utility found in the UCSF Chimera tool suite (62) to first trace possible main chain paths through the density. Ambiguous breaks and “branches” were left unconnected such that these could be revisited after all confident main chain segments were traced and built. Chimera marker files and the filtered cryoEM density maps were then imported into the crystallographic program COOT (63) for further analysis.

We then began constructing Cα models following our marker trace files using the manual Baton_build utility in COOT. Observable main chain residue bumps in the density were used as reference points to approximate Cα positions. After Cα backbones of all confident main chain segment traces were built, previously unconnected main chain ends in ambiguous regions were analyzed to determine the final correct trace, relying on several levels of constraints. These included: the linearity of the protein; secondary structure predictions of the protein obtained from prediction servers JPRED (64) and Phyre2 (65), which we used to cross-reference helices and β-sheets visible in our density and traced in our main chain segments; and the protein amino acid sequence, which we cross-referenced with our Cα segments and density features to locate large side chain features that served as “landmarks” to evaluate the accuracy of our trace. Upon determining a complete main chain trace, a refined Cα model was rebuilt for model-able regions of the protein, and amino acid registration was accomplished by virtue of landmark side chain features. We thus worked out coarse models for most regions of the MCP, Tri1, Tri2A, and Tri2B proteins in our initial modeling attempt. Of note, the MCP upper domain trace was determined referencing HSV-1’s VP5ud model (35), which we fitted into our HCMV density map. Finally, at 4.5-Å resolution, attempts to perform large-scale refinement of our atomic models yielded highly inconsistent results. Consequently, we refined these first models completely by hand using the Regularization utility in COOT.

Soon after concluding our major modeling efforts on the 4.5-Å map, we gained access to the aforementioned direct electron-counting camera, at which point we decided to endeavor a second imaging session to attempt a higher resolution density map from which we could perhaps improve our atomic models. The resulting 3.9-Å density map obtained from our second round of imaging and reconstruction was drastically improved. On a qualitative level, densities at the capsid floor versus outer regions were much more consistent in side chain resolution and main chain connectivity (figs. S4 to S7). With the new 3.9-Å map, we validated our initial models and importantly, the accuracy of our main chain traces in regions that were previously resolved through constraint-based deduction. The new map also affirmed that our residue registration using the 4.5-Å map was mostly correct across all modeled proteins, but contained occasional errors involving localized registration shifts of a few amino acids. These errors were corrected, and several regions previously left unmodeled in the 4.5-Å attempt due to poor density quality were modeled in this attempt. As before, we opted to leave regions with sub-optimal density quality as gaps in the atomic model, as opposed to approximating poly-Ala traces. Notable regions/proteins that we were able to successfully model using the improved 3.9-Å map—and which we attempted, but were unsuccessful in using the 4.5-Å map—included: the N-anchor of Tri1; upper loop regions in the embracing arms of Tri2A and Tri2B; and the C-terminal 63 residues of the 75 residue SCP as well as the N-terminal one-third of pp150 tegument protein, both situated at the outer extremes of the capsid.

The 3.9-Å map permitted us to refine our improved full-atom models using real space refinement in Phenix (66). After multiple rounds of refinement, the final coordinate file was submitted along with the EM density map to the Worldwide Protein Data Bank. Lastly, atomic models and densities in figures were visualized and rendered in Chimera, and movies were recorded using the Animations utility in Chimera.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. CryoEM imaging of HCMV particles. Image recorded using a Gatan K2 Summit direct electron detector shows two types of particles in our sample preparation: DNA-containing and DNA-devoid, corresponding to infectious virion and noninfectious enveloped particles (NIEPs), respectively. Scale bar denotes 100 nm.

Figure S2. Reconstructions of HCMV particles and resolution assessment. (A) Radially colored 4.5-Å resolution reconstruction of HCMV obtained from film images, viewed along a threefold axis. fivefold, threefold, and twofold axes are indicated by a pentagon, triangle, and oval, respectively. (B) Close-up views of MCP floor region helical density (mesh) from the 4.5-Å reconstruction superposed with ribbon and stick MCP models in left and right panels, respectively. (C) Comparison of resolution assessments of the initial 4.5-Å film-based reconstruction (black curve) and subsequent 3.9-Å reconstruction (blue curve) obtained from direct electron detection imaging. Resolutions were determined using a reference-based FSC coefficient criterion of 0.143.

Figure S3. Local resolution assessment. Local resolution heat maps of density slices through an asymmetric unit, rendered using ResMap (58). The red through blue color scheme corresponds to regions of relative low through high resolution.

Figure S4. Density map and atomic model of MCP. Insets correspond to zoomed-in views of boxed regions and illustrate residue features in the density map (mesh).

Figure S5. Density map and atomic model of Tri1. Insets correspond to zoomed-in views of boxed regions and illustrate residue features in the density map (mesh).

Figure S6. Density maps and atomic models of Tri2 conformers. (A) Tri2A density map and ribbon model. (B) Tri2B density map and ribbon model. Insets in (A) and (B) correspond to zoomed-in views of boxed regions and illustrate residue features in the density map (mesh).

Figure S7. Density maps and atomic models of SCP and pp150nt. (A) SCP density map and ribbon model. (B) pp150nt density map and ribbon model. Insets in (A) and (B) correspond to zoomed-in views of boxed regions and illustrate residue features in the density map (mesh).

Figure S8. A comparison of Johnson fold topologies. (A–C) Schematics depict the Johnson fold organization of HCMV MCP, HK97 gp5, and BPP-1 MCP, respectively. Johnson fold N-, α-, and β-elements are colored cyan, green, and magenta, respectively. HCMV MCP and HK97 gp5 share a similar arrangement of Johnson fold elements, while BPP-1 MCP utilizes a different permutation of Johnson fold elements (33). Black bars in (A) indicate sites of HCMV MCP domain insertions. Black bar in (B) indicates site of I-domain insertion in phage P22 (48). (D–F) Ribbon models of HCMV MCP, HK97 gp5, and BPP-1 MCP, respectively, colored by Johnson fold element as in (A–C). Insets depict their respective Johnson fold β-cores.

Figure S9. Lock unit interactions and global capsid organization. (A) A lock unit is comprised of six MCPs organized around a central triplex. Each lock unit includes a complete set of all interactions found within the HCMV capsid, including three pairs of type I interactions (blue), three pairs of type II interactions (red), and three pairs of type III interactions forming one lasso triangle (yellow), upon which the triplex sits. (B) Lock units are arranged in six overlapping units such that each hexon is at the center of a lock unit group-of-six (GOS). Each MCP is included in two lock units and directly interacts with four lock units. Thus, a lock unit interacts with all lock units within its GOS except the far opposite unit. Intersecting lock unit boundaries denote direct interactions. (C) A global view of GOSs reveals that each lock unit (filled hexagons) takes part in three GOSs (blue, teal, and green GOSs not shown for simplicity). Individual lock units are thus able to interact with nine unique lock units—four from each of three GOSs, overlap between GOSs not counted. Concatenated rings representing HK97’s covalent chainmail are superposed on overlapping GOSs for comparative reference.

Figure S10. Conserved regions and conformers of pp150nt. (A) Schematic showing the amino acid sequence and secondary structure of pp150nt. Lines represent loops, and pink cylinders represent helices. β-herpesvirus-conserved regions CR1 and CR2 are boxed in green, while the primate CMV-conserved cysteine tetrad is boxed in yellow. (B) Rainbow ribbon model (blue at the N terminus through green and yellow to red at the C terminus) of pp150nt with labeled helices. (C) Structural alignment based on Cα positions of the three pp150nt conformers associated with the Tb triplex reveals a greater degree of structural similarity at the upper helix bundle compared to the lower helix bundle.

Acknowledgments

Our research has been supported in part by grants from the NIH (GM071940, DE025567, and AI094386) and NSF (DMR-1548924). We acknowledge the use of instruments at the Electron Imaging Center for Nanomachines supported by the University of California–Los Angeles and by instrumentation grants from NIH (1S10RR23057 and 1U24GM116792) and NSF (DBI-1338135). We thank H. Zhu for providing AD169 HCMV virus stock, X. Zhang and S. Shivakati for assistance with tissue culture, W. H. Hui for assistance with cryoEM data collection, B. K. Zhou for scanning some of the films, and X. Zhang for help with the refinement of atomic models. The cryoEM density map and atomic coordinates of models reported here are deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank and the Protein Data Bank with accession codes EMD-8703 and 5VKU, respectively. Z.H.Z. conceived the project; X.Y. and Z.H.Z. designed the experiments; X.Y. prepared the samples; X.Y., J.Jia., and Z.H.Z. recorded and processed the EM data; J.Jih, X.Y., and Z.H.Z. built the atomic models; J.Jih, X.Y., and Z.H.Z. analyzed and interpreted the models; J.Jih and X.Y. prepared the illustrations and media; Z.H.Z., X.Y., and J.Jih wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Vancíková Z, Dvorák P. Cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals—a review. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2001;1:179–187. doi: 10.2174/1568005310101020179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler SP. Congenital cytomegalovirus screening. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:1105–1106. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200512000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lerner CW, Tapper ML. Opportunistic infection complicating acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Clinical features of 25 cases. Medicine. 1984;63:155–164. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoover DR, et al. Clinical manifestations of AIDS in the era of pneumocystis prophylaxis. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1922–1926. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312233292604. doi:10.1056/NEJM199312233292604; 7902536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Bij W, Speich R. Management of cytomegalovirus infection and disease after solid-organ transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:S32–S37. doi: 10.1086/320902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramanan P, Razonable RR. Cytomegalovirus infections in solid organ transplantation: A review. Infect Chemother. 2013;45:260–271. doi: 10.3947/ic.2013.45.3.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rook AH. Interactions of cytomegalovirus with the human immune system. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:S460–S467. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.Supplement_3.S460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20:202–213. doi: 10.1002/rmv.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mocarski ES, Courcelle CT. In: Fields Virology. Knipe DM, et al., editors. Vol. 2. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 2629–2674. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen JK, Frim DM, Isacson O, Breakefield XO. Herpesvirus-mediated gene delivery into the rat brain: Specificity and efficiency of the neuron-specific enolase promoter. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1993;13:503–515. doi: 10.1007/BF00711459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Zhang X. Oncolytic HSV as a vector in cancer immunotherapy. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;651:279–290. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-786-0_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen SG, et al. Profound early control of highly pathogenic SIV by an effector memory T-cell vaccine. Nature. 2011;473:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature10003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen SG, et al. Immune clearance of highly pathogenic SIV infection. Nature. 2013;502:100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature12519. doi:10.1038/nature12519; 24025770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davison AJ, et al. The human cytomegalovirus genome revisited: Comparison with the chimpanzee cytomegalovirus genome. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:17–28. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhella D, Rixon FJ, Dargan DJ. Cryomicroscopy of human cytomegalovirus virions reveals more densely packed genomic DNA than in herpes simplex virus type 1. J Mol Biol. 2000;295:155–161. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer DW, Huffman JB, Homa FL, Evilevitch A. Herpes virus genome, the pressure is on. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:11216–11221. doi: 10.1021/ja404008r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baxter MK, Gibson W. Cytomegalovirus basic phosphoprotein (pUL32) binds to capsids in vitro through its amino one-third. J Virol. 2001;75:6865–6873. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6865-6873.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu X, et al. Biochemical and structural characterization of the capsid-bound tegument proteins of human cytomegalovirus. J Struct Biol. 2011;174:451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai X, et al. The smallest capsid protein mediates binding of the essential tegument protein pp150 to stabilize DNA-containing capsids in human cytomegalovirus. PLOS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003525. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leong PA, Yu X, Zhou ZH, Jensen GJ. Correcting for the ewald sphere in high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. Methods Enzymol. 2010;482:369–380. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)82015-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Zhou ZH. Limiting factors in atomic resolution cryo electron microscopy: No simple tricks. J Struct Biol. 2011;175:253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amunts A, et al. Structure of the yeast mitochondrial large ribosomal subunit. Science. 2014;343:1485–1489. doi: 10.1126/science.1249410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu P, et al. Three-dimensional structure of human γ-secretase. Nature. 2014;512:166–170. doi: 10.1038/nature13567. doi:10.1038/nature13567; 25043039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merk A, et al. Breaking cryo-EM resolution barriers to facilitate drug discovery. Cell. 2016;165:1698–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veesler D, et al. Atomic structure of the 75 MDa extremophile Sulfolobus turreted icosahedral virus determined by CryoEM and X-ray crystallography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5504–5509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300601110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu X, Jiang J, Sun J, Zhou ZH. A putative ATPase mediates RNA transcription and capping in a dsRNA virus. eLife. 2015;4:e07901. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sirohi D, et al. The 3.8 Å resolution cryo-EM structure of Zika virus. Science. 2016;352:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5316. doi:10.1126/science. aaf5316; 27033547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huet A, et al. Extensive subunit contacts underpin herpesvirus capsid stability and interior-to-exterior allostery. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:531–539. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai X, et al. CryoEM and mutagenesis reveal that the smallest capsid protein cements and stabilizes Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus capsid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E649–E656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420317112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou ZH, Chen DH, Jakana J, Rixon FJ, Chiu W. Visualization of tegument-capsid interactions and DNA in intact herpes simplex virus type 1 virions. J Virol. 1999;73:3210–3218. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3210-3218.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wikoff WR, et al. Topologically linked protein rings in the bacteriophage HK97 capsid. Science. 2000;289:2129–2133. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fokine A, et al. Structural and functional similarities between the capsid proteins of bacteriophages T4 and HK97 point to a common ancestry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7163–7168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502164102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X, et al. A new topology of the HK97-like fold revealed in Bordetella bacteriophage by cryoEM at 3.5 Å resolution. eLife. 2013;2:e01299. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker ML, Jiang W, Rixon FJ, Chiu W. Common ancestry of herpesviruses and tailed DNA bacteriophages. J Virol. 2005;79:14967–14970. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14967-14970.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowman BR, Baker ML, Rixon FJ, Chiu W, Quiocho FA. Structure of the herpesvirus major capsid protein. EMBO J. 2003;22:757–765. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newcomb WW, et al. Structure of the herpes simplex virus capsid. Molecular composition of the pentons and the triplexes. J Mol Biol. 1993;232:499–511. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zandi R, Reguera D. Mechanical properties of viral capsids. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2005;72:021917. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.021917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou ZH, et al. Assembly of VP26 in herpes simplex virus-1 inferred from structures of wild-type and recombinant capsids. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:1026–1030. doi: 10.1038/nsb1195-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lai L, Britt WJ. The interaction between the major capsid protein and the smallest capsid protein of human cytomegalovirus is dependent on two linear sequences in the smallest capsid protein. J Virol. 2003;77:2730–2735. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2730-2735.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conway JF, et al. Labeling and localization of the herpes simplex virus capsid protein UL25 and its interaction with the two triplexes closest to the penton. J Mol Biol. 2010;397:575–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.043. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.043; 20109467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toropova K, Huffman JB, Homa FL, Conway JF. The herpes simplex virus 1 UL17 protein is the second constituent of the capsid vertex-specific component required for DNA packaging and retention. J Virol. 2011;85:7513–7522. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00837-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai X, Gong D, Wu TT, Sun R, Zhou ZH. Organization of capsid-associated tegument components in Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol. 2014;88:12694–12702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01509-14. doi:10.1128/JVI.01509-14; 25142590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sae-Ueng U, et al. Major capsid reinforcement by a minor protein in herpesviruses and phage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:9096–9107. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.AuCoin DP, Smith GB, Meiering CD, Mocarski ES. Betaherpesvirus-conserved cytomegalovirus tegument protein ppUL32 (pp150) controls cytoplasmic events during virion maturation. J Virol. 2006;80:8199–8210. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00457-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kindt J, Tzlil S, Ben-Shaul A, Gelbart WM. DNA packaging and ejection forces in bacteriophage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13671–13674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241486298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evilevitch A, Lavelle L, Knobler CM, Raspaud E, Gelbart WM. Osmotic pressure inhibition of DNA ejection from phage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9292–9295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1233721100. doi:10.1073/pnas.1233721100; 12881484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou ZH, Chiou J. Protein chainmail variants in dsDNA viruses. AIMS Biophys. 2015;2:200–218. doi: 10.3934/biophy.2015.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rizzo AA, et al. Multiple functional roles of the accessory I-domain of bacteriophage P22 coat protein revealed by NMR structure and CryoEM modeling. Structure. 2014;22:830–841. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.04.003. doi:10.1016/j.str.2014.04.003; 24836025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lander GC, et al. Bacteriophage lambda stabilization by auxiliary protein gpD: Timing, location, and mechanism of attachment determined by cryo-EM. Structure. 2008;16:1399–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carragher B, et al. Leginon: An automated system for acquisition of images from vitreous ice specimens. J Struct Biol. 2000;132:33–45. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suloway C, et al. Automated molecular microscopy: The new Leginon system. J Struct Biol. 2005;151:41–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li X, et al. Electron counting and beam-induced motion correction enable near-atomic-resolution single-particle cryo-EM. Nat Methods. 2013;10:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mindell JA, Grigorieff N. Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2003;142:334–347. doi: 10.1016/S1047-8477(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liang Y, Ke EY, Zhou ZH. IMIRS: A high-resolution 3D reconstruction package integrated with a relational image database. J Struct Biol. 2002;137:292–304. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00014-x. doi:10.1016/S1047-8477(02)00014-X; 12096897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ludtke SJ, Baldwin PR, Chiu W. EMAN: Semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J Struct Biol. 1999;128:82–97. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X, Zhang X, Zhou ZH. Low cost, high performance GPU computing solution for atomic resolution cryoEM single-particle reconstruction. J Struct Biol. 2010;172:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.05.006. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2010.05.006; 20493949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosenthal PB, Henderson R. Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:721–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.07.013. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2003.07.013; 14568533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kucukelbir A, Sigworth FJ, Tagare HD. Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nat Methods. 2014;11:63–65. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wan Y, Chiu W, Zhou ZH. 2004; International Conference on Communications, Circuits and Systems; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers; 2004. pp. 960–964. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou ZH. Atomic resolution cryo electron microscopy of macromolecular complexes. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2011;82:1–35. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386507-6.00001-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.DeRosier DJ. Correction of high-resolution data for curvature of the Ewald sphere. Ultramicroscopy. 2000;81:83–98. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3991(99)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Drozdetskiy A, Cole C, Procter J, Barton GJ. JPred4: A protein secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W389–W394. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. CryoEM imaging of HCMV particles. Image recorded using a Gatan K2 Summit direct electron detector shows two types of particles in our sample preparation: DNA-containing and DNA-devoid, corresponding to infectious virion and noninfectious enveloped particles (NIEPs), respectively. Scale bar denotes 100 nm.

Figure S2. Reconstructions of HCMV particles and resolution assessment. (A) Radially colored 4.5-Å resolution reconstruction of HCMV obtained from film images, viewed along a threefold axis. fivefold, threefold, and twofold axes are indicated by a pentagon, triangle, and oval, respectively. (B) Close-up views of MCP floor region helical density (mesh) from the 4.5-Å reconstruction superposed with ribbon and stick MCP models in left and right panels, respectively. (C) Comparison of resolution assessments of the initial 4.5-Å film-based reconstruction (black curve) and subsequent 3.9-Å reconstruction (blue curve) obtained from direct electron detection imaging. Resolutions were determined using a reference-based FSC coefficient criterion of 0.143.

Figure S3. Local resolution assessment. Local resolution heat maps of density slices through an asymmetric unit, rendered using ResMap (58). The red through blue color scheme corresponds to regions of relative low through high resolution.

Figure S4. Density map and atomic model of MCP. Insets correspond to zoomed-in views of boxed regions and illustrate residue features in the density map (mesh).

Figure S5. Density map and atomic model of Tri1. Insets correspond to zoomed-in views of boxed regions and illustrate residue features in the density map (mesh).

Figure S6. Density maps and atomic models of Tri2 conformers. (A) Tri2A density map and ribbon model. (B) Tri2B density map and ribbon model. Insets in (A) and (B) correspond to zoomed-in views of boxed regions and illustrate residue features in the density map (mesh).