Significance

Absolute zero resistance of superconducting materials is difficult to achieve in practice due to the motion of microscopic Abrikosov vortices, especially when external currents are applied. Even a partial resistance reduction via vortex immobilization by microscopic material imperfections is the holy grail of superconductivity research. It is commonly believed that the dissipation increases with applied magnetic field since the number of vortices increases as well. Through the example of molybdenum–germanium superconducting nanostrips, we show that resistive losses due to vortex motion can actually be decreased by applying an increasing applied magnetic field parallel to the current. This surprising recovery of superconductivity is achieved through “vortex crowding”: The increased number of vortices impedes their mutual motion, resulting in straight, untwisted vortices.

Keywords: parallel magnetic field, reentrant superconductivity, vortex, nanostrips

Abstract

The motion of Abrikosov vortices in type-II superconductors results in a finite resistance in the presence of an applied electric current. Elimination or reduction of the resistance via immobilization of vortices is the “holy grail” of superconductivity research. Common wisdom dictates that an increase in the magnetic field escalates the loss of energy since the number of vortices increases. Here we show that this is no longer true if the magnetic field and the current are applied parallel to each other. Our experimental studies on the resistive behavior of a superconducting Mo0.79Ge0.21 nanostrip reveal the emergence of a dissipative state with increasing magnetic field, followed by a pronounced resistance drop, signifying a reentrance to the superconducting state. Large-scale simulations of the 3D time-dependent Ginzburg–Landau model indicate that the intermediate resistive state is due to an unwinding of twisted vortices. When the magnetic field increases, this instability is suppressed due to a better accommodation of the vortex lattice to the pinning configuration. Our findings show that magnetic field and geometrical confinement can suppress the dissipation induced by vortex motion and thus radically improve the performance of superconducting materials.

Vortex dynamics determine the electromagnetic responses of almost all practically important superconductors. Abrikosov vortices are created by the magnetic field penetrating a type-II superconductor, each carrying a single flux quantum surrounded by circulating supercurrents (1). Understanding the electromagnetic properties of superconductors in applied magnetic fields is crucial for the majority of superconducting applications. If an electric current, , is applied to the superconductor with a magnetic induction , the associated Lorentz force can induce motion of the vortices if it is greater than the vortex pinning force due to defects. (2) The vortex motion in turn leads to dissipation and breakdown of the zero-resistance state. Another practically important situation is when the magnetic field and the current are parallel, for example in force-free superconducting cables (3). A tacit assumption is that in this case there will be no electric losses as vortices are typically aligned with the magnetic field, resulting in a zero Lorentz force configuration. However, previous experiments on superconductors in parallel magnetic fields are still controversial. Namely, an electric field and, correspondingly, dissipation appear along the field/current direction (4–16). Moreover, the superconducting critical current appears to increase with the magnetic field (4–8, 15). Surprisingly, an instantaneous electric field opposite to the field/current direction was reported (9, 11, 12, 16). A number of theories were proposed to elucidate these phenomena (13, 17–32), including flux cutting (19, 30, 33, 34), helical normal/superconducting domains (35, 36), and helical vortex flow (13, 31). However, the vortex behavior responsible for the observed dissipation in a parallel magnetic field is still under debate (14, 28, 30, 31).

All of the abovementioned experiments and theories focus on macroscopic samples with dimensions much larger than the superconducting coherence length. On the other hand, when the dimensions of the sample become comparable to the superconducting coherence length, the subtle interplay of vortex lattice confinement and pinning may lead to new behavior. Here, we investigate this nontrivial problem by carrying out experimental and theoretical investigations on superconducting strips with thicknesses comparable to the superconducting coherence length in parallel magnetic fields. We show that the resistance of the superconducting thin strips first increases with a parallel magnetic field and then surprisingly drops back to zero at higher magnetic fields, indicating a reentrance to the superconducting state. This resistive behavior exhibits strong dependences on temperature, current, and strip thickness, which cannot be understood with any existing theory. Using large-scale, 3D time-dependent Ginzburg–Landau (TDGL) simulations (37, 38), we demonstrate that the observed resistive behavior is due to unwinding of twisted vortices (i.e., at about 10–20% of the second critical field) (Fig. 1B). Further increase of the magnetic field results in straightening of vortices and increase in their constitutive pinning, leading to reduced dissipation.

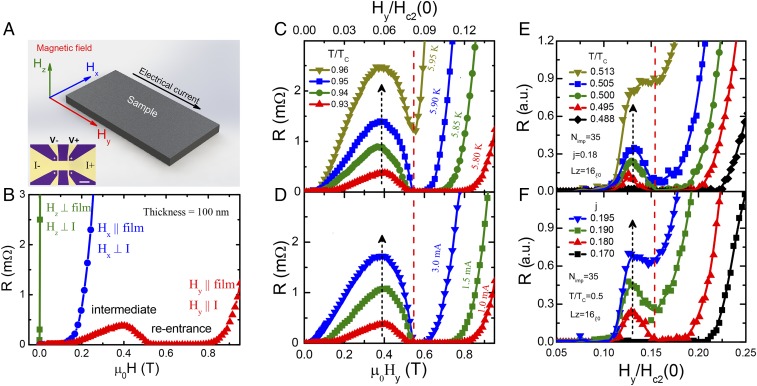

Fig. 1.

Temperature- and current-dependent parallel magnetic-field–induced reentrant superconductivity. (A) Schematics of the superconducting MoGe film in a triple-axis vector magnet. The out-of-plane magnetic field is perpendicular to both the film plane and the current direction. The in-plane magnetic field is parallel to the film plane and perpendicular to the current direction. The in-plane magnetic field is parallel to both the film plane and the current direction. The electrical current is applied parallel to the direction. A, Bottom Left Inset shows a photo of the micropatterned MoGe strip. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (B) Magneto-resistance measured at K for a -nm-thick sample under magnetic fields in three orthogonal directions x (blue), y (red), and z (green), respectively. The resistance curve for the parallel field () shows a resistant state at intermediate fields and a reentrance of the superconducting state at higher fields. (C–F) Experimental results (C and D) and TDGL simulations (E and F) for the parallel field-dependent resistance at various temperatures (C and E) and at different currents (D and F). The zero-field superconducting critical temperature and zero-temperature upper critical field are K and T, respectively. Other simulation parameters, impurity density and sample thickness, are and (nm is zero-temperature coherence length).

Sample Configuration

The experiments were carried out on Mo0.79Ge0.21 (MoGe) superconducting thin strips with weak intrinsic vortex pinning (39). Fig. 1A shows the schematic of the sample orientation with respect to the magnetic field and the electrical current. The orientation of the magnetic field with respect to the sample was carefully aligned in a triple-axis vector magnet. The detailed field alignment procedures can be found in SI Appendix. In this work, we mainly focus on the rarely investigated configuration of a parallel magnetic field () and current in the sample plane. Fig. 1A, Bottom Left Inset shows the micropatterned MoGe strip.

For more details on the sample preparation, see Materials and Methods.

Results and Discussion

Parallel Magnetic-Field–Induced Reentrant Superconductivity.

The magneto-resistance of a sample with thickness of nm is shown in Fig. 1B for magnetic fields applied in the three orthogonal directions with respect to the applied current and at a temperature of K ( K). The green curve (with squares) in Fig. 1B corresponds to results for the out-of-plane magnetic field (perpendicular to the current). The resistance increases immediately with the magnetic field at very low fields due to the penetration of vortices, which are driven by the Lorentz force and the weak intrinsic vortex pinning in MoGe (39). When a magnetic field is applied in the sample plane (but perpendicular to the electrical current), the increase of the resistance with magnetic field is slower compared with that for the out-of-plane magnetic field. Correspondingly, the zero-resistance state persists up to fields of T, as shown by the blue (with circles) curve in Fig. 1B. The zero-resistance state is due to confinement effects induced by the surface barrier, whose effect is stronger in thinner samples (40). Most previous investigations on superconducting vortex motion were conducted in the above two sample/field configurations while the Lorentz force-free configuration in the parallel field was largely overlooked, especially in confined superconductors. The behavior corresponding to the magnetic field applied parallel to the applied electrical current ( direction) is illustrated by the red (with triangles) curve in Fig. 1B. Here, the magneto-resistance first increases with at an even slower rate than that for . With further increase of , the resistance rapidly drops to zero (below the detectable resistance sensitivity of ), resulting in a reentrance to the superconducting state.

Cordoba et al. (41) recently observed a reentrant dissipation-free state in W-based wires and TiN-perforated films. In that work, the magnetic field and applied current are perpendicular to each other in the maximum Lorentz-force configuration and the reentrant dissipation-free state is due to arrested vortex motion by self-induced collective traps. This effect cannot explain our observed resistance behavior in parallel magnetic fields, where the Lorentz force is supposed to be absent. Furthermore, enhancement of superconductivity by a parallel magnetic field in an ultrathin Pb film and a 2D electron gas at the interface of LaAlO3/SrTiO3 was reported in ref. 42. The enhancement was attributed to the increase of the mean-field critical temperature with increasing parallel magnetic field. Although enhanced superconductivity could lead to a gradual reduction of the dissipation, in our sample, the mean-field critical temperature decreases with magnetic field parallel to the current as demonstrated by the R-T curves in SI Appendix, Fig. S4.

The emergence of a low-dissipation state in our superconducting thin strips under a parallel magnetic field is truly surprising and cannot be explained by any existing theories developed for macroscopic samples. For example, the helical vortex structures, as proposed for macroscopic superconducting wires or slabs (13, 31, 35, 36), cannot be formed due to the reduced sample thickness with highly confined vortices. Also, the result cannot be described by the flux cutting effect (19, 30, 33, 34), since it would require a very large current to produce a sufficient transverse magnetic field to tilt the vortices. Moreover, the current-induced magnetic field (self-field) can be safely neglected in our experiment at currents mA.

Suppression of Vortex Motion by Parallel Fields.

The resistance–temperature curves in semilog plots show apparent kinks, indicated by the arrows in Fig. 2A and those in SI Appendix, Fig. S4. The dissipation behavior below the kink, compared with the rapid drop above the kink, can be attributed to vortex motion. At zero field, the dissipation is due to the motion of vortices and antivortices, which nucleate at the opposite outer boundaries and move toward the middle of the sample where they annihilate (43). The temperature range for the transition below the kink at the intermediate field T is wider than those measured at T and T. This indicates that the vortex motion is first enhanced with and then is significantly suppressed at higher fields. This is consistent with the resistance behavior shown in Fig. 1B for the parallel magnetic-field dependence measured at a fixed temperature. The dissipation transition induced by vortex motion (below the kink) measured with a current of mA (Fig. 2A) is more obvious compared with that measured at a lower current (see SI Appendix, Fig. S4B for corresponding measurement at mA). This behavior is consistent with vortex motion driven by a Lorentz force, since higher currents produce stronger driving forces. Our observed dissipation state at intermediate most likely originates from vortex motion and the reentrant superconducting state could be ascribed to the suppression of vortex motion in a parallel-field configuration. results. These are discussed in detail below. This vortex crowding effect means that a higher concentration of vortices can actually impede their motion.

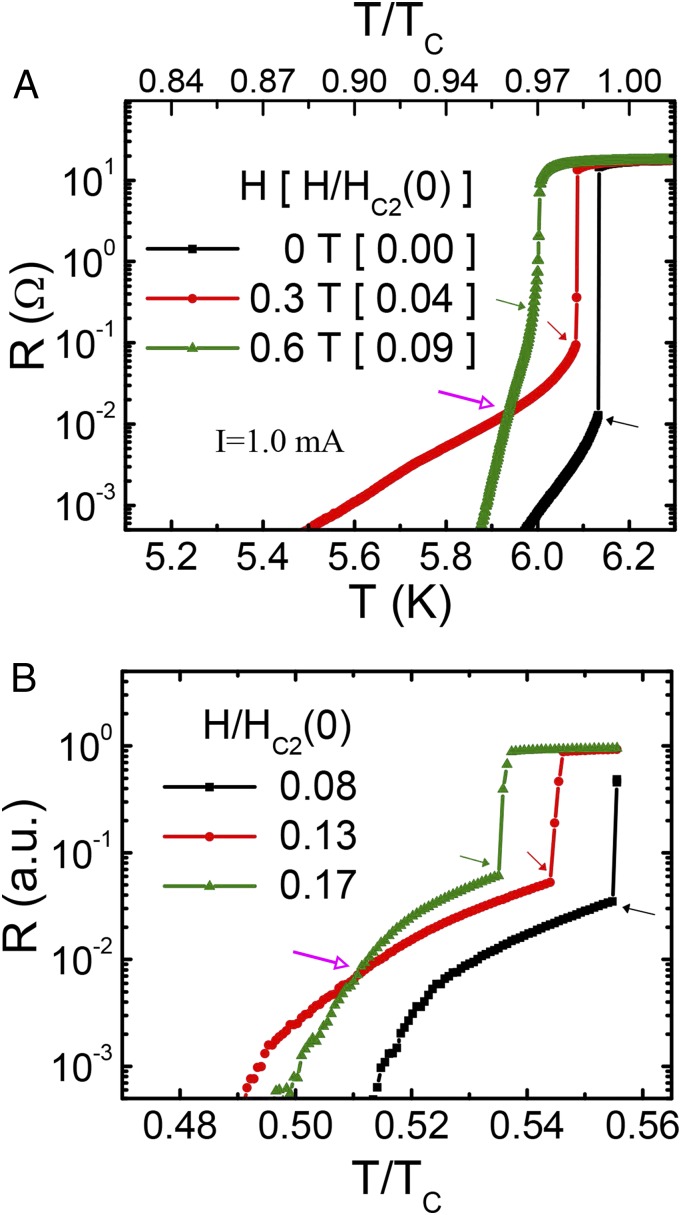

Fig. 2.

Temperature dependence of vortex motion-induced resistance behavior. (A) The temperature dependence of the resistance under parallel magnetic fields of T (black square), T (red circle), and T (green triangle) obtained with an applied current of mA. The main panel in A is a semilog plot and Inset shows the corresponding linear plot. The resistive states below the kinks shown by arrows are typical features originating from vortex motion. (B) Simulation results for the temperature dependence of the voltage (magneto-resistance) at different magnetic fields ( in the dissipationless, Lorentz-free regime; in the intermediate resistive regime; and in the reentrant regime). The simulations are conducted using a current density of and for a typical system size with inclusions.

Our measurements shown in Fig. 1B for the HI configuration indicate almost immediate breakdown of zero-resistance superconductivity, which would occur in relatively clean samples with small (but finite) concentration of point defects. In a parallel field, and in the absence of point disorder, vortex lines would be perfectly parallel to the applied field. Accordingly, the absence of a Lorentz force on the vortices should yield exceedingly high critical currents, which cannot lead to the observed intermediate dissipation state and reentrant superconducting states in an ideally pure sample. However, in the presence of point disorder with finite concentration for a real sample, vortices can locally bend to accommodate the pinning sites, which results in the creation of a Lorentz force from the driving current. Consequently, vortex motion and resistive dissipation appear at a much smaller current density than that in the absence of disorder.

Model and TDGL Simulations.

To rationalize the experimental results and obtain insight into the behavior of superconducting currents in applied parallel magnetic fields, we performed large-scale vortex dynamics simulations based on the TDGL equation (Materials and Methods). In most of the simulations, the sample size was in the field direction (), with strip width ( direction) of . The strip thickness is nm, using zero-temperature coherence length nm of MoGe estimated from the critical temperature vs. magnetic-field phase diagram (44). The sample was periodic in the field direction (). Superconductor/vacuum boundary conditions for the superconducting order parameter , , were imposed at the surfaces in the shorter transverse direction () to simulate the same thickness as in the experiment. The transverse size in the direction was chosen to be large enough such that the system behavior becomes insensitive to it, while maintaining a manageable computation time (Materials and Methods).

Fig. 1E shows our simulation results of the vortex dynamics for the parallel field-dependent resistance at a fixed driving current () and at different temperatures, while Fig. 1F is simulated at fixed temperature () and at different driving currents. In both cases, the in-plane parallel field, , is increased and the resulting dissipation, measured in the voltage drop across the sample, is shown. These results agree well with the experimental data shown in Fig. 1 C and D.

In our model, we hypothesize that this phenomenon is related to a more optimal accommodation of the vortex lattice to disorder at low fields and straightening of the flux lines at high fields. A subsequent increase of the magnetic field results in a breakdown of the dissipation-free state and recovery of the resistive state due to vortex crowding, the mutual repulsion of vortices, and the geometric confinement by the sample boundaries results in straightening of the vortex configuration and mitigation of the bending due to defects. As indicated by Fig. 1 E and F, the vortex dynamics behavior under parallel magnetic fields is strongly dependent on temperature and current. To further validate our hypothesis, we conducted experimental measurements and TDGL simulations at various temperatures and currents. The results are shown in Fig. 1 C–F. Remarkably, in faithful agreement between experiments and theoretical simulations, our results show an increase in temperature leads to narrowing of the reentrant superconducting field range and a slight decrease of the onset field. In other words, when the temperature rises, the resistance (or, equivalently voltage, which is proportional to the resistance) in the intermediate resistive state increases, while the field range of the reentrant low-dissipation state shrinks, as shown in Fig. 1 C (experiment) and E (TDGL simulation). With further increasing temperature, the state becomes always resistive, although the voltage–magnetic-field dependence is strongly nonmonotonic (brown inverse triangle curves in Fig. 1 C and E). The effect of the applied current on the reentrant superconductivity phenomena is shown in Fig. 1 D (experiments) and F (TDGL simulation). When increasing the current, the intermediate resistance state in parallel magnetic fields is gradually enhanced while the magnetic-field range of the reentrant low-resistance state shrinks.

Fig. 2B shows the temperature dependence of the resistance/voltage at three different applied parallel fields: in the dissipationless, Lorentz-free regime(black), in the intermediate resistive regime (red), and in the reentrant regime (green). Again, the behavior agrees very well with the observed behavior in the experiment (Fig. 2A). We note that we chose the zero-temperature coherence length as the unit length, which results in a temperature-dependent linear coefficient in the TDGL equation. As a reference point, we fixed this coefficient to be (or ), resulting in a lower temperature than the experimental value. However, this allows us to change the temperature without altering the physical dimensions of the system and, at the same time, to obtain a reasonably large voltage signal. A direct reproduction of the experiments is impractical, since the linear coefficient in the temperature range of is about 20 times smaller and thus the voltage signal will be much noisier and more statistics would be required, making the simulations unfeasible.

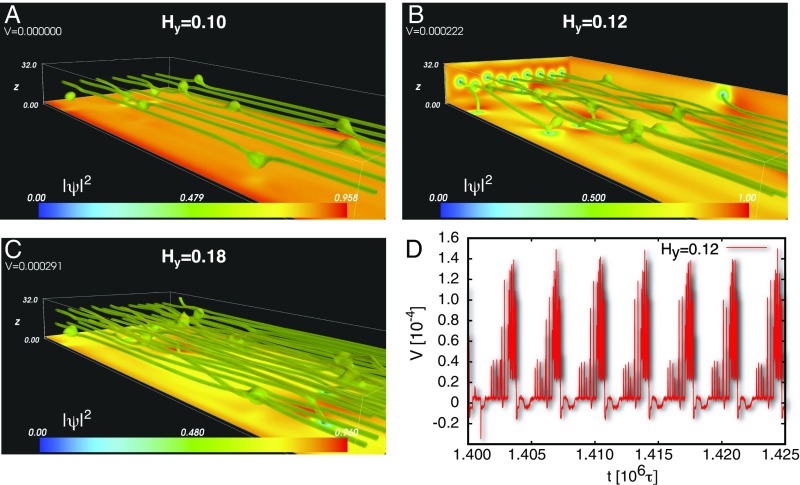

For an intuitive understanding of the underlying processes resulting in the reentrance behavior, we studied the vortex dynamics at different fields. Snapshots highlighting the vortex configurations in the three distinctive regimes are shown in Fig. 3 A–C. At relatively small magnetic fields, individual vortex lines are able to “optimize” deformations and accommodate to the given pinning sites (Fig. 3A) without the need to bend much. In this situation, the Lorentz force is not sufficient to overcome the pinning force and shows no dissipation. Increasing the magnetic field results in a larger number of deformed vortex lines (Fig. 3B). In the presented situation the vortex density becomes so large that vortices need to bend more at the pinning sites to be close to their equilibrium position (which would be an Abrikosov lattice without disorder). Due to this bending, the Lorentz force becomes larger than the pinning force and vortices start to move; i.e., the system becomes dissipative. The finite thickness of the sample initially allows the twisted vortices to unwind by bending toward the surfaces and to move in opposite directions at the two opposing surfaces. If the field is increased even further (Fig. 3C), the vortex density becomes even larger. In this case, the vortices do not have room to bend much more and instead, they straighten due to vortex crowding. As a result, dissipation is suppressed and the voltage or magneto-resistance is decreased, constituting the reentrance region. When the magnetic field is above a certain value , the critical current becomes lower than the applied current, leading to the emergence of the high-field resistive state.

Fig. 3.

Time dependence of the vortex matter. (A–D) Isosurfaces of the order parameter magnitude illustrating snapshot vortex configuration in a rectangular sample for different magnetic fields in units of the zero-temperature upper critical field . The green isosurface for shows both tubes around vortex cores and blobs around pinning centers. Randomly distributed point defects (large green blobs) result in distorted vortex lines (green tubes). (A) in the pinned state where the vortex density is low and vortices are mostly parallel to the direction. (B) in the periodic regime where vortices perform a helical motion along the surfaces. (C) in the intermediate, low-resistance regime, where the vortex density is high such that the vortex realigns with the axis and the resistance shows reentrance behavior. D shows the time evolution of the voltage (or magneto-resistance) in the periodic regime corresponding to B. The time is measured in units of the Ginzburg–Landau time.

The time dependence of the voltage in the intermediate resistive state is shown in Fig. 3D (see Movie S3 for better visualization). In this resistive state, the overall dynamics are characterized by a periodic and relatively slow evolution of the vortex lines, resulting in a small voltage and fast reconnection/breakup events manifested by sharp spikes in the voltage time curve. However, the timescale of these oscillations is on the order of a few picoseconds (Materials and Methods), such that a direct measurement is difficult. In the experiment, only the average voltage (dc measurement) is measured. All other plots of simulation data show voltage values averaged over long time intervals in steady-state regimes.

We attribute this phenomenon to the subtle interplay between two competing factors that determine the vortex dynamics in superconducting nanostrips: geometrical confinement of vortices, leading to an increase of the critical current, and the distortion of vortex lines by point disorder, resulting in a finite Lorentz force and subsequently leading to a decrease of the critical current. This interplay is strongly dependent on temperature and current as shown in Fig. 1 C–F. In fact, increasing the temperature reduces the superconducting condensation energy and pinning forces induced by point defects and thus enhances the intermediate dissipation states. Meanwhile, increasing the current also increases the driving force, which leads to enhancements of the intermediate dissipative states.

Effect of Strip Thickness and Defect Concentration.

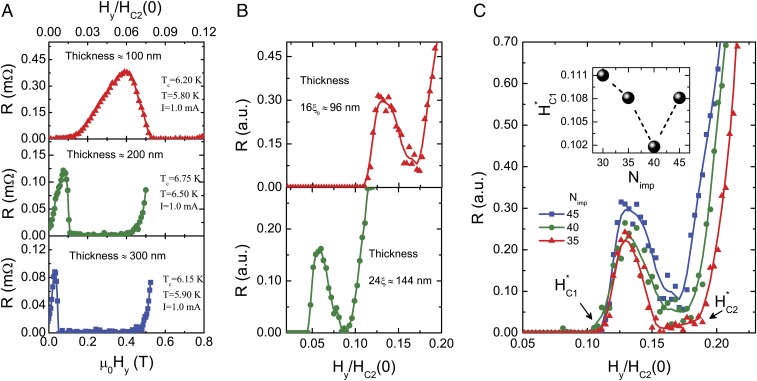

In our model, the vortex bending induced by finite point defects in a confined sample is the key for illustrating the parallel field-induced dissipation state at intermediate fields and the reentrant superconducting state at higher fields. The vortex bending effect is expected to be sensitive to the sample thickness. To examine the effect of sample thickness, we fabricated MoGe strips with thicknesses ranging from nm to nm. Fig. 4A shows the experimental results for samples with thicknesses of nm (Top), nm (Middle), and nm (Bottom). Increasing the thickness leads to a significant decrease of the reentrant superconducting onset field. In other words, the dissipation states and reentrant superconducting states emerge at lower fields for thicker samples. For the thinnest sample with thickness of nm, we did not observe the reentrant superconductivity effect at any of the tested temperatures or currents (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). The most likely explanation is that the reentrance field of the -nm sample is higher than the upper critical field or beyond the highest experimentally accessible . The effect of strip thickness can also be repeated by our TDGL simulation, as shown in Fig. 4B, which further confirms our hypothesis that the novel resistive state originates from motion of twisted/distorted vortices and the reentrance of the superconducting state is induced by vortices straightening at higher parallel magnetic fields. The simulations confirm that the onset field of the intermediate resistive region decreases with thickness, its width becomes smaller, and the maximum dissipation in this region decreases.

Fig. 4.

Effect of strip thickness and defect concentration. (A) Parallel field-dependent resistance for samples with thickness of nm (Top), nm (Middle), and nm (Bottom). The corresponding sample and measurement parameters are listed in the keys. (B) TDGL simulation result of the dissipation voltage for two samples with different thicknesses: and . The concentration of defects in both samples is similar, indicated by the higher number of impurities in the thicker sample. (C) Simulation results for the parallel field dependence of the voltage (magneto-resistance) at fixed temperature and applied current . The different curves show the dependence on the disorder (measured in the number of spherical impurities). Increase in the number of defects results in an overall increase of the voltage. C, Inset shows the nonmonotonic dependence of the lower critical-field onset, , of the resistive state as function of the number of impurities in the sample in a fixed-size system.

Since the appearance of the resistive state at lower fields is related to the local bending of vortices by point defects, it is clear that the reentrance should depend on the concentration of defects in the sample (Fig. 4C). Although it is difficult to investigate the effect of defect concentration experimentally, our TDGL simulation clearly indicates that there is an optimal defect concentration (about 35–40 impurities in the simulated system), where the critical field , when the sample first becomes resistive, is the smallest (Fig. 4C, Inset). Furthermore, at this optimal concentration, the reentrance region is most pronounced with lowest intermediate resistance values and largest “second critical field,” , (Fig. 4C) above which the resistance starts to increase with the magnetic field again. This can be understood as follows: If the concentration is low, we are close to the Lorentz force-free state with higher (Movie S1). In contrast, if the concentration is too high, the effect of defects does not allow for an intermediate straightening of the vortices and decrease of the Lorentz force (Movie S2) and therefore the system becomes resistive at without a reentrance region. Increasing the number of defects has a similar effect to increasing the temperature and narrows the reentrant domain. These observations support our hypothesis that further increase in the number of vortices leads to straightening of vortices and decrease of the Lorentz force.

There are multiple roles of disorder (point defects) in superconductors. First, defects locally suppress superconductivity, which reduces the upper critical fields. Second, defects act as vortex pinning centers, which prevents vortex motion and increases the superconducting critical current (45). Here, we investigate a third important consequence of defects in confined superconductors, namely the distortion or bending of vortex lines. The first two effects of defects do not change with the orientation of the magnetic field. However, the third effect, namely the local bending of vortex lines at defects, plays a crucial role in a parallel magnetic-field configuration as they lead to finite Lorentz forces, which can destroy the dissipationless state of a superconductor. This behavior is in stark contrast to a perpendicular field configuration, where point pinning impedes vortex motion and increases the critical current.

Conclusion

We discovered a unique reentrant behavior of superconductivity in nanostrips placed in a parallel magnetic field. In experiments on MoGe samples, the magneto-resistance first increases with magnetic field, but at higher fields reduces to zero, such that superconductivity is recovered. This effect is strongly temperature dependent and can lead to a suppression of resistance below the measurable threshold over a range of a few kilogausses. We elucidated the vortex dynamics and magneto-resistance behavior in the framework of large-scale, 3D TDGL simulations. Our simulations revealed the mechanism for the observed behavior: The intermediate resistive state is due to a vortex instability leading to an unwinding of twisted vortex configurations. Upon increasing the magnetic field, these instabilities are suppressed and the resistance drops due to a higher vortex concentration, leading to straightening of the vortex lines. An important factor in this interpretation is the presence of a small amount of defects in the system: Without defects, vortices would simply align with the current until thermal fluctuations bend them and the resulting Lorentz force will lead to a resistive state. This would happen at relatively high fields. The agreement between experiments and simulations on the evolution of the resistance as a function of magnetic field, temperature, electrical current, and sample thickness indicates the close relevance of our simulations to the experimental data and validates our model.

Materials and Methods

Sample Fabrication and Measurement.

Films of -nm thickness were sputtered from a MoGe alloy target onto silicon substrates with an oxide layer. The samples were patterned into -m-wide microbridges, using photolithography. Transport measurements were carried out using a standard dc four-probe method with a Keithley 6221 current source and a Keithley 2182A nanovoltmeter. The electrical current flows horizontally along the long length of the microbridge. The applied magnetic field is precisely aligned along the electrical current direction in a triple-axis vector magnet. A detailed process of the field alignment can be found in SI Appendix.

Simulation Parameters.

For details on the algorithm and definition of all parameters, see ref. 37. The 3D TDGL equations

| [1] |

| [2] |

were solved numerically by an implicit finite-difference method. Here is the superconducting order parameter, is the vector potential corresponding to the applied magnetic field along the direction, is the current density and is the scalar potential, , is the temperature, and is critical temperature. Note that in this scaling the zero-temperature coherence length is the unit of length, the second critical field is the unit for the field, and the depairing current density for is given by . Here we used for the unit of current and the GL depairing current .

The benchmark system has the dimensions , , ( nm) with open boundary conditions in directions and periodic boundary conditions in directions. The used computational mesh has grid points. The size and open boundary conditions in the direction are crucial for the confinement of the strip and for the study of the thickness dependence in reproducing the experimental system. The overall behavior is controlled by this smallest dimension of the system. For larger sizes (above ), the behavior does not depend much on the thickness and the related boundary condition. Also, increasing the size or changing to periodic boundaries in the direction has no qualitative effect on the system’s behavior. An external dimensionless current density of is applied in the direction and the dimensionless magnetic field, , is changed between and [in units of ]. The linear coefficient is set to ().

Disorder is introduced by spherical defects with , corresponding to a normal region with , and diameter , due to its efficient pinning behavior (46). of those are randomly distributed in the simulation cuboid. The system is evolved over million time steps of length , where is the GL time—for MoGe this is given by ps. After an initial relaxation period, the magnetic field is ramped from to in steps. Before each ramping step, the voltage response is averaged over time steps. The final magneto-voltage curves are then averaged over typical disorder realizations.

The simulations were performed on Nvidia Tesla K20X GPUs. A magneto-voltage curve for a single disorder realization needs about 20 h real simulation time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division. The simulation was supported by the Scientific Discovery through Advanced Computing program funded by US DOE, Office of Science, Advanced Scientific Computing Research and Basic Energy Science, Division of Materials Science and Engineering. L.R.T. and Z.-L.X. acknowledge support through National Science Foundation Grant DMR-1407175. Use of the Center for Nanoscale Materials, an Office of Science user facility, was supported by the DOE, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1619550114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Abrikosov AA. On the magnetic properties of superconductors of the second group. Sov Phys JETP. 1957;5:1174–1182. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson PW, Kim YB. Hard superconductivity: Theory of the motion of Abrikosov flux lines. Rev Mod Phys. 1964;36:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsushita T, Kiuchi M, Otabe ES. Innovative superconducting force-free cable concept. Supercond Sci Technol. 2012;25:125009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sekula ST, Boom RW, Bergeron CJ. Longitudinal critical currents in cold-drawn superconducting alloys. Appl Phys Lett. 1963;2:102–104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cullen GW, Cody GD, McEvoy JP. Field and angular dependence of critical currents in sn. Phys Rev. 1963;132:577–580. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cullen GW, Novak RL. Effect of fast neutron induced defects on the current carrying behavior of superconducting Nb3Sn. Appl Phys Lett. 1964;4:147–149. [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeBlanc MAR, Belanger BC, Fielding RM. Paramagnetic helical current flow in type-II superconductors. Phys Rev Lett. 1965;14:704–707. [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeBlanc MAR. Pattern of current flow in nonideal type-II superconductors in longitudinal magnetic fields. Phys Rev. 1966;143:220–223. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walmsley DG. Force free magnetic fields in a type II superconducting cylinder. J Phys F Met Phys. 1972;2:510–528. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicholson J, Sikora P. Flux flow in type II superconducting wires in longitudinal magnetic fields. J Low Temp Phys. 1974;17:275–286. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walmsley DG, Timms WE. Flux flow in longitudinal geometry. J Phys F Met Phys. 1977;7:2373–2380. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cave JR, Evetts JE. Static electric potential structures on the surface of a type II superconductor in the flux flow state. Philos Mag B. 1978;37:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsushita T, Ozaki S, Nishimori E, Yamafuji K. A nonequilibrium themodynamic effect on a flux distribution in a superconductor under a longitudinal magnetic field. J Phys Soc Jpn. 1985;54:1060–1065. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clem JR, Weigand M, Durrell JH, Campbell AM. Theory and experiment testing flux-line cutting physics. Supercond Sci Technol. 2011;24:062002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irie F, Matsushita T, Otabe S, Matsuno T, Yamafuji K. Critical current density of superconducting NbTa tapes in a longitudinal magnetic field. Cryogenics. 1989;29:317–320. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsushita T, Shimogawa A, Asano M. Observation of structure of electric field on the surface of superconducting Pb–In slab under a longitudinal magnetic field. Physica C Supercond. 1998;298:115–121. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clem J. On the breakdown of force-free configurations in type-II superconductors. Phys Lett A. 1975;54:452–454. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clem JR. Spiral-vortex expansion instability in type-II superconductors. Phys Rev Lett. 1977;38:1425–1428. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brandt E. Continuous vortex cutting in type II superconductors with longitudinal current. J Low Temp Phys. 1980;39:41–61. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clem J. Steady-state flux-line cutting in type II superconductors. J Low Temp Phys. 1980;38:353–370. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandt EH. Flux-line instability in a pin-free superconducting cylinder with longitudinal current. Phys Rev B. 1982;25:5756–5760. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clem JR, Perez-Gonzalez A. Internal-magnetic-field distribution at the critical current of a type-II superconductor subjected to a parallel magnetic field. Phys Rev B. 1986;33:1601–1610. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pérez-González A, Clem JR. Flux-line-cutting effects at the critical current of cylindrical type-II superconductors. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1990;42:4100–4104. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.42.4100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsh GE. Flux flow and flux cutting in type-II superconductors carrying a longitudinal current. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1994;50:571–574. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.50.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genenko YA. Magnetic self-field entry into a current-carrying type-II superconductor. II. Helical vortices in a longitudinal magnetic field. Phys Rev B. 1995;51:3686–3695. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.51.3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aranson I, Gitterman M, Shapiro BY. Onset of vortices in thin superconducting strips and wires. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1995;51:3092–3096. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.51.3092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shvartser M, Gitterman M, Shapiro B. Dynamics of helical vortices in a superconducting wire. Physica C Supercond. 1996;264:204–212. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruiz HS, Badía-Mjaos A, Lopez C. Material laws and related uncommon phenomena in the electromagnetic response of type-II superconductors in longitudinal geometry. Supercond Sci Technol. 2011;24:115005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiz HS, Lopez C, Badia-Majos A. Inversion mechanism for the transport current in type-II superconductors. Phys Rev B. 2011;83:014506. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell AM. Flux cutting in superconductors. Supercond Sci Technol. 2011;24:091001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsushita T. Longitudinal magnetic field effect in superconductors. Jpn J Appl Phys. 2012;51:010111. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Genenko YA, Troche P, Hoffmann J, Freyhardt HC. Chain model for the spiral instability of the force-free configuration in thin superconducting films. Phys Rev B. 1998;58:11638–11651. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell A, Evetts J. Flux vortices and transport currents in type II superconductors. Adv Phys. 1972;21:199–428. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blamire MG, Evetts JE. Critical cutting force between flux vortices in a type-II superconductor. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1986;33:5131–5133. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.33.5131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ezaki T, Irie F. On the resistive state of current-carrying rods of type 2 superconductors in longitudinal magnetic fields. J Phys Soc Jpn. 1976;40:382–389. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ezaki T, Yamafuji K, Irie F. Flux flow in a current-carrying cylinder of type 2 superconductor in a longitudinal magnetic field. J Phys Soc Jpn. 1976;40:1271–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sadovskyy I, Koshelev A, Phillips C, Karpeyev D, Glatz A. Stable large-scale solver for Ginzburg–Landau equations for superconductors. J Comput Phys. 2015;294:639–654. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwok WK, et al. Vortices in high-performance high-temperature superconductors. Rep Prog Phys. 2016;79:116501. doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/79/11/116501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang M, Kunchur MN, Hua J, Xiao Z. Evaluating free flux flow in low-pinning molybdenum-germanium superconducting films. Phys Rev B. 2010;82:064502. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bean CP, Livingston JD. Surface barrier in type-II superconductors. Phys Rev Lett. 1964;12:14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Córdoba R, et al. Magnetic field-induced dissipation-free state in superconducting nanostructures. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1437. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeffrey Gardner H, et al. Enhancement of superconductivity by a parallel magnetic field in two-dimensional superconductors. Nat Phys. 2011;7:895–900. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Latimer ML, Berdiyorov GR, Xiao ZL, Peeters FM, Kwok WK. Realization of artificial ice systems for magnetic vortices in a superconducting MoGe thin film with patterned nanostructures. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;111:067001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.067001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Latimer ML, Berdiyorov GR, Xiao ZL, Kwok WK, Peeters FM. Vortex interaction enhanced saturation number and caging effect in a superconducting film with a honeycomb array of nanoscale holes. Phys Rev B. 2012;85:012505. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blatter G, Feigelman M, Geshkenbein V, Larkin A, Vinokur VM. Vortices in high-temperature superconductors. Rev Mod Phys. 1994;66:1125. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koshelev AE, Sadovskyy IA, Phillips CL, Glatz A. Optimization of vortex pinning by nanoparticles using simulations of the time-dependent Ginzburg-Landau model. Phys Rev B. 2016;93:060508. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.