Abstract

Background and objectives

Genetic heterogeneity and phenotypic variability are major challenges in familial nephronophthisis and related ciliopathies. To date, mutations in 20 different genes (NPHP1 to -20) have been identified causing either isolated kidney disease or complex multiorgan disorders. In this study, we provide a comprehensive and detailed characterization of 152 children with a special focus on extrarenal organ involvement and the long-term development of ESRD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We established an online-based registry (www.nephreg.de) to assess the clinical course of patients with nephronophthisis and related ciliopathies on a yearly base. Cross-sectional and longitudinal data were collected. Mean observation time was 7.5±6.1 years.

Results

In total, 51% of the children presented with isolated nephronophthisis, whereas the other 49% exhibited related ciliopathies. Monogenetic defects were identified in 97 of 152 patients, 89 affecting NPHP genes. Eight patients carried mutations in other genes related to cystic kidney diseases. A homozygous NPHP1 deletion was, by far, the most frequent genetic defect (n=60). We observed a high prevalence of extrarenal manifestations (23% [14 of 60] for the NPHP1 group and 66% [61 of 92] for children without NPHP1). A homozygous NPHP1 deletion not only led to juvenile nephronophthisis but also was able to present as a predominantly neurologic phenotype. However, irrespective of the initial clinical presentation, the kidney function of all patients carrying NPHP1 mutations declined rapidly between the ages of 8 and 16 years, with ESRD at a mean age of 11.4±2.4 years. In contrast within the non-NPHP1 group, there was no uniform pattern regarding the development of ESRD comprising patients with early onset and others preserving normal kidney function until adulthood.

Conclusions

Mutations in NPHP genes cause a wide range of ciliopathies with multiorgan involvement and different clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Nephronophthisis (NPH); Nephronophthisis related ciliopathy; Joubert-like syndromes; Senior-Løken syndrome; Bardet-Biedl syndrome; Congenital oculomotor apraxia; COACH syndrome; Mainzer-Saldino syndrome; NEPHREG registry; Adolescent; Genetic Heterogeneity; Prevalence; Cross-Sectional Studies; Nephronophthisis, familial juvenile; Kidney Diseases, Cystic; Homozygote; Kidney Failure, Chronic; Mutation; Registries; Ciliopathies

Introduction

Familial nephronophthisis (NPH) is a major cause of pediatric ESRD. It shows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern with an estimated incidence of 1:50,000 (1–6). The clinical presentation as well as the genetic background are highly variable, with mutations identified in 20 different genes (NPHP1 to -20) so far (1,7,8). A homozygous deletion of NPHP1 is by far the most frequent genetic cause, accounting for 27%–62% of cases in patients (9–12). Recently, modern sequencing techniques accelerated the unraveling of further genetic causes, but still, about 60% of patients with NPH remain genetically unclassified (13). Nephrocystins, the proteins encoded by the NPHP genes, localize to the primary cilium, and mutations result in an impaired ciliary function, classifying NPH as a ciliopathy (1,14–17).

The disease phenotype may be limited to the kidneys or can be associated with extrarenal organ involvement (e.g., liver, pancreas, central nervous system, eyes, and bones). Several well described complex syndromes encompass the range of kidney involvement with NPH, including Senior–Løken syndrome; Joubert syndrome; cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, oligophrenia, ataxia, coloboma, hepatic fibrosis [COACH] syndrome; Jeune syndrome; Meckel–Gruber syndrome, and others (1,15,18,19). Because of its rather unspecific clinical presentation and the significant overlap with other ciliopathies, an early diagnosis of NPH is challenging (20–22).

Within the last 20 years, scientific efforts have brought tremendous progress for the molecular understanding of NPH. However, despite this constantly increasing knowledge, the diagnostic and therapeutic management of NPH is still largely opinion based. This obvious discrepancy is a common problem for most rare diseases (23). Prospective data on the natural disease course are limited, especially concerning the deterioration of kidney function and the evolution of extrarenal manifestations. Therefore, we established an online-based multicenter observational registry for NPH and related ciliopathies (www.nephreg.de). The Nephronophthisis Registry (NEPHREG) aims to characterize the phenotypic and genetic spectrum as well as obtain longitudinal data regarding extrarenal organ involvement of patients carrying NPHP gene mutations. These data are of particular importance to provide robust genotype-phenotype correlations, an improved clinical management, and personalized counseling to patients and their families. At the same time, the registry will serve as an important source for future clinical trials assessing the efficacy and safety of potential treatments.

Here, we present the genetic and phenotypic data of 152 children from the NEPHREG.

Materials and Methods

Study Cohort

Those eligible were children with suspected isolated NPH or NPH-related ciliopathies due to either the clinical presentation or the presence of pathogenic NPHP mutations. The clinical diagnosis of NPH was on the basis of at least two of the following criteria: (1) characteristic clinical course with polyuria/polydipsia, (2) CKD, (3) kidney ultrasound or biopsy suggestive of NPH, and (4) pedigree compatible with autosomal recessive inheritance. The diagnosis of Senior–Løken syndrome was on the basis of the presence of NPH in association with retinitis pigmentosa. Congenital oculomotor ataxia was diagnosed due to typical eye movements and ataxia. Neurologic criteria for Joubert syndrome were on the basis of the presence of a molar tooth sign on magnetic resonance imaging or the clinical diagnosis. COACH syndrome was diagnosed if additional hepatic fibrosis and/or ocular coloboma were found. Jeune and Mainzer–Saldino syndromes were diagnosed on the basis of typical skeletal malformations. Complex phenotypes featuring multiple organ malformations, including NPH, that did not fit one of the mentioned criteria were considered unclassified.

All patients and/or their parents/guardians gave written informed consent. Personalized data got pseudonymized and underwent a manual quality assurance process by the central data quality manager, who verified the data plausibility before incorporation into the NEPHREG data repository. The NEPHREG has been approved by the ethics committees of each contributing center and is kept in full accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Genetic Testing

Because of the study design, different approaches in genetic testing were performed (Supplemental Figure 1). In most patients presenting with a typical phenotype for juvenile NPH, a PCR-based gel electrophoresis for detection of a homozygous NPHP1 deletion was performed. In others, targeted Sanger sequencing on the basis of the patient’s phenotype was done. In a subset of patients, next generation sequencing–based approaches, such as whole-exome sequencing or a multigene panel, were performed as described in Supplemental Material and elsewhere (24,25).

Clinical Assessment and Definitions

Kidney function was assessed using the eGFR according to the Schwartz formula, with a coefficient of 0.55 in the case of creatinine determination with the Jaffe method or 0.413 in the case of enzymatic creatinine measurement. CKD was defined by an eGFR <90 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and ESRD was defined by an eGFR<15 ml/min per 1.73 m2, the start of dialysis, or renal transplantation. Polyuria was defined as >2000 ml/m2 body surface area per day. Hepatosplenomegaly was defined either by clinically enlarged organs on palpatory examination and/or ultrasound. Kidney volume was assessed by the measurement of the maximum length of the kidney (L; centimeters) and the orthogonal anterior-posterior diameter (D; centimeters) and width (W; centimeters) of each kidney. Kidney volume was calculated as 0.5×L×D×W (milliliters).

Statistical Analyses

Categorical parameters are given as numbers and percentages of patients. Results for continuous variables are expressed as means±SD. Comparisons of patients with NPHP1 versus patients without NPHP1 were performed using the chi-squared test. The level of statistical significance was predefined as P<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the link www.vassarstats.net.

Results

Data of 176 patients were provided from 22 participating German, Austrian, and Dutch pediatric nephrology centers. Among those patients, 152 (86 boys) met the criteria of at least one complete and validated dataset; 126 (82%) were patients with sporadic cases, and a positive family history and/or parental consanguinity were documented in 26 (17%) patients/24 families. The mean observation time was 7.5±6.1 years. The mean age at last follow-up was 14.0±6.6 years.

Genetic Analyses

Monogenetic defects were identified in 97 of 152 (64%) patients. In 89 patients, these mutations affected different NPHP genes. Mutations in the remaining eight patients presenting with an NPH phenotype were found in BBS7 (n=2), BBS4, PKHD1, MKS1, AHI1, POC1B, and UMOD, reclassifying them as non-NPH (Supplemental Figure 2). A detailed listing of all NPHP mutations, including 14 novel mutations, is provided in Supplemental Table 1.

For further analysis, we stratified the cohort into children with NPHP1 (n=60) and all others (n=92). Whenever possible, we further classified the children without NPHP1 according to their gene defect.

Initial Clinical Presentation

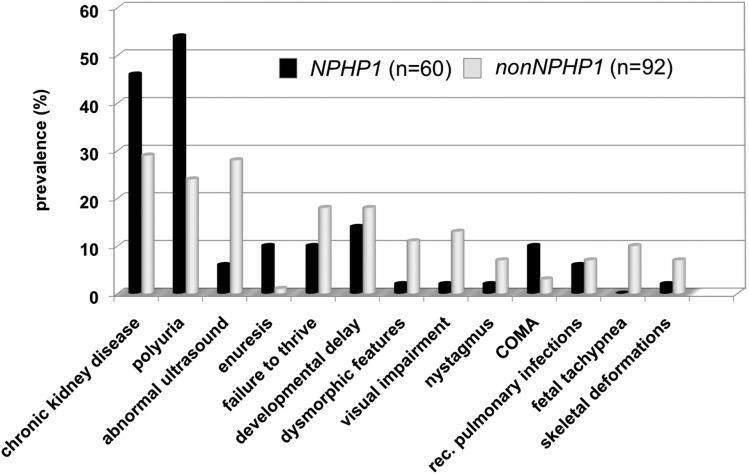

At initial clinical presentation, there was a significant difference between the NPHP1 group and the remaining patients (Figure 1). Whereas in one half of the children with NPHP1, polyuria (54%) or CKD (46%) led to diagnosis, the main signs and symptoms of patients without NPHP1 were less specific, including dysmorphic features (11%), failure to thrive (18%), developmental delay (18%), visual impairment (12%), or fetal tachypnea (10%).

Figure 1.

Chronic kidney disease and polyuria are the clinical hallmarks for NPHP1 patients while the main signs and symptoms for children with other NPHP mutations can be manifold. Initial clinical presentation leading to the diagnosis of nephronophthisis (NPH) or NPH-related ciliopathies in the Nephronophthisis Registry. Although in one half of the children with NPHP1, polyuria (54%) or CKD (46%) led to diagnosis, the main signs and symptoms of children without NPHP1 were less specific, including dysmorphic features (11%), failure to thrive (18%), developmental delay (18%), visual impairment (12%), or fetal tachypnoe (10%). However, the latter symptoms presented significantly earlier, mostly within the first year of life, whereas the first signs of urinary-concentrating defects usually did not become obvious before the age of 4–6 years old. COMA, congenital oculomotor apraxia.

Kidney Disease Phenotype

Reduced urinary concentrating capacity and CKD represent the clinical hallmarks of NPH. Still, polyuria was only reported in 38 of 60 (63%) patients with NPHP1, and it was reported even less often in all others. Proteinuria was found in up to 32% of patients with NPHP1 (19 of 60) but almost exclusively in the scenario of ESRD. Thus, proteinuria developed secondary to advanced glomerulosclerosis rather than representing an NPH-specific feature. Hematuria was a rare finding (Table 1). Anemia was detected in 104 of 152 (68%) patients. In most patients (90 of 104), anemia was associated with advanced CKD (mean eGFR =25 ml/min per 1.73 m2). However, in 14 individuals—including six patients with NPHP1 and six patients with Joubert/COACH phenotype—CKD-independent anemia was observed (eGFR>45 ml/min per 1.73 m2).

Table 1.

Phenotypic presentation of 152 children with suspected isolated nephronophthisis or nephronophthisis-related ciliopathies in the Nephronophthisis Registry

| Phenotype | NPHP1, n=60 | All Genotypes Other Than NPHP1, n=92 | NPHP3, n=4 | NPHP4, n=5 | NPHP5/IQCB1, n=5 | NPHP6/CEP290, n=5 | NPHP11/TMEM67, n=6 | IFT140, n=4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney | ||||||||

| Onset of renal symptoms, yr | 3–16 | 0–7 | 6–14 | 13–25 | 7–17 | 2–15 | 3–16 | |

| Polyuria, % | 63 | 36 | 50 | 60 | 40 | 20 | 17 | 0 |

| Urinary concentrating deficiency, % | 40 | 26 | 25 | 40 | 40 | 20 | 17 | 0 |

| Proteinuria, % | 32 | 39 | 25 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 17 | 75 |

| Hematuria, % | 18 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anemia, % | 88 | 55 | 100 | 80 | 80 | 60 | 50 | 50 |

| Failure to thrive, % | 20 | 26 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 33 | 0 |

| Growth retardation, % | 28 | 32 | 50 | 60 | 0 | 60 | 33 | 50 |

| Liver | ||||||||

| Onset of liver symptoms, yr | 10–13 | 0–10 | - | - | - | 1–3 | 8 | |

| Total, % | 8a | 41a | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 25 |

| Hepatosplenomegaly, % | 3 | 29 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Elevated liver enzymes, % | 5 | 27 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 25 |

| Cholestasis, % | 0 | 10 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 |

| Thrombopenia, % | 3 | 11 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 |

| Ascites, % | 0 | 3 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Esophageal varices, % | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 |

| Hepatic pruritus, % | 2 | 2 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 |

| CNS | ||||||||

| Onset of neurologic symptoms, yr | 1–12 | - | 6 | 9 | 0–1 | 0–3 | 8 | |

| Total, % | 25b | 47b | 0 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 83 | 25 |

| Developmental delay, % | 19 | 40 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 83 | 25 |

| Seizures, % | 7 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ataxia, % | 8 | 21 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 80 | 83 | 0 |

| Cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, % | 3 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 0 |

| Muscle weakness, % | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 |

| Microcephaly, % | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Eyes | ||||||||

| Onset of eye symptoms, yr | 1–17 | 9 | - | 0–1 | 0–7 | 0–1 | 1–9 | |

| Total, % | 41 | 55 | 25 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 83 | 100 |

| Visual impairment, % | 23c | 41c | 25 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 75 |

| Nystagmus, % | 12 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 33 | 75 |

| COMA, % | 10 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| Night blindness, % | 2 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| Retinitis pigmentosa, % | 5 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 20 | 0 | 100 |

| Visual field restriction, % | 5 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Astigmatism, % | 17 | 12 | 25 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 17 | 0 |

| Strabism, % | 8 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 33 | 0 |

| Cataract, % | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Coloboma, % | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 |

For practical reasons, we stratified the cohort into children with NPHP1 (n=60) and children without NPHP1 (n=92). Cell contents are the percentages of participants in a given column (genotype) for which the symptom listed in the row header was reported or the ranges of ages over which these symptoms initially presented. Whenever possible, we further classified the children without NPHP1 according to their gene defect. CNS, central nervous system; COMA, congenital oculomotor apraxia.

Statistical significance: liver involvement was significantly more frequent in the non-NPHP1 group compared with the NPHP1 cohort (41% versus 8%; P<0.001).

Statistical significance: presence of neurologic symptoms was significantly more frequent in the non-NPHP1 group compared with the NPHP1 cohort (47% versus 25%; P<0.01).

Statistical significance: visual loss was significantly more frequent in the non-NPHP1 group compared with the NPHP1 cohort (41% versus 23%; P=0.02).

Kidney Ultrasound

A typical ultrasound presentation of small to normal-sized kidneys with increased echogenicity and a loss of corticomedullary differentiation (26) was observed in 119 of 152 (78%) children, including 47 of 60 (78%) patients with NPHP1. Cystic lesions were only detected in 73 of 144 (51%) children. Although in most patients with NPHP1, cysts developed late in the disease course (12.3±3.9 years), most children carrying NPHP3 or NPHP6/CEP290 mutations presented cysts already at a young age (NPHP3: 0, 7, and 8 years and NPHP6: 0, 1, 3, and 7 years).

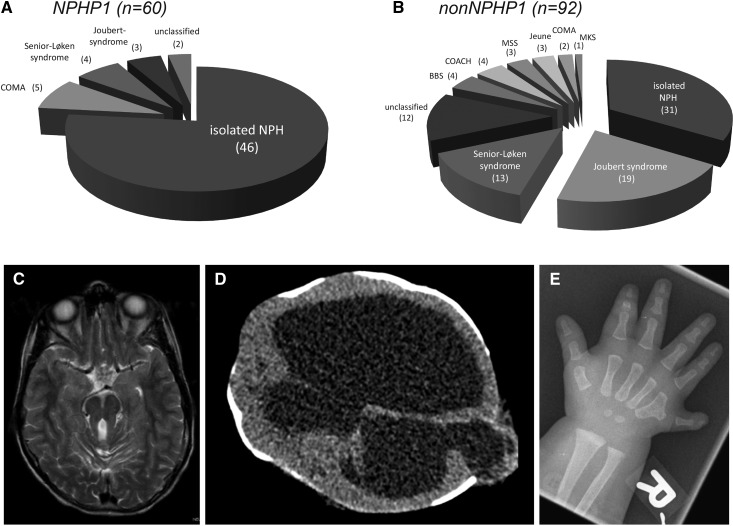

Extrarenal Manifestations

Overall, 77 of 152 (51%) patients presented with isolated NPH. The remaining children exhibited NPH-related ciliopathies, namely Joubert/COACH syndrome (n=26; 17%), Senior–Løken syndrome (n=17; 11%), congenital oculomotor apraxia (n=7; 5%), Bardet–Biedl syndrome (n=4; 3%), skeletal disorders (n=6; 4%), or Meckel–Gruber syndrome (n=1; <1%). Fourteen children displayed complex disorders that could not be classified yet. In the NPHP1 group, 77% (46 of 60) presented with an isolated NPH compared with 34% (31 of 92) in the non-NPHP1 group (Figure 2). Liver involvement was more frequent in the non-NPHP1 group (41% versus 8%; P<0.001). The same applied to the presence of neurologic symptoms (47% versus 25%; P<0.01) and visual impairment (41% versus 23%; P=0.02), although there was no significant difference detectable between the two groups regarding all ophthalmologic affections (55% versus 41%; P=0.10) (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Isolated NPH is the typical phenotype of most NPHP1 patients while complex NPH-related ciliopathies are abundant in the nonNPHP1 group. Frequency of clinically defined nephronophthisis (NPH)-related ciliopathies in the Nephronophthisis Registry with respect to the presence/absence of an NPHP1 deletion. Isolated NPH is more frequent in (A) the NPHP1 group than in (B) children without NPHP1. Nevertheless, in 25%, a homozygous NPHP1 deletion led to a neurologic phenotype as well. (C) Axial magnetic resonance image of a child with Joubert syndrome showing the typical cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, resulting in a positive molar tooth sign. (D) Cerebral magnetic resonance image of a child with Meckel–Gruber syndrome (MKS) showing severe brain malformations: occipital encephalocele and massively enlarged cerebrospinal fluid compartments. (E) An x-ray of a postaxial hexadactyly in a child with Bardet–Biedl syndrome (BBS). COACH, cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, oligophrenia, ataxia, coloboma, hepatic fibrosis; COMA, congenital oculomotor apraxia; MSS, Mainzer–Saldino syndrome.

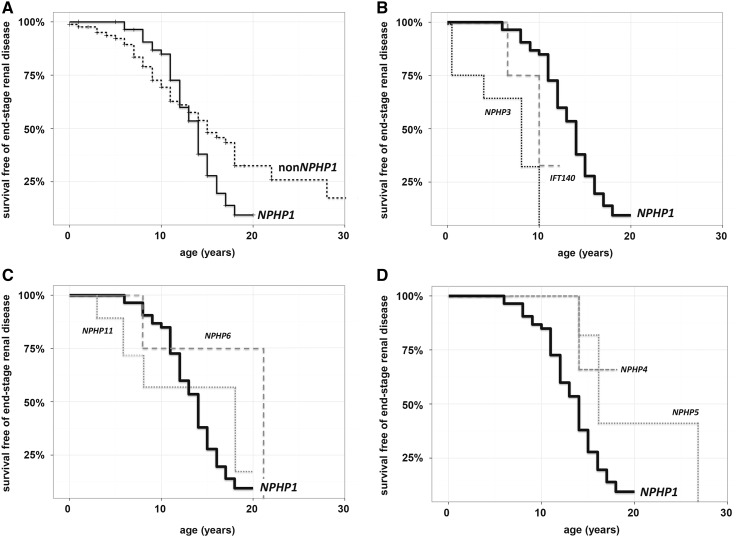

Kidney Function

Overall, 90 (58%) patients developed ESRD during the observation period. Within the NPHP1 cohort, 38 (63%) children presented juvenile NPH, with ESRD at a mean age of 11.4±2.4 years. Only five patients with NPHP1 reached ESRD beyond the age of 15 years (17.0±1.41 years old), and ESRD younger than the age of 5 years was not observed. Seventeen (28%) patients with NPHP1 did not reach ESRD yet (mean age =11.4±5.2 years old), but 16 of 17 exhibited significantly reduced eGFR. In contrast, 52% (47 of 90) of the non-NPHP1 cohort did not develop ESRD yet, with 31% (28 of 90) preserving normal kidney function so far (eGFR>90 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Seven (8%) children without NPHP1 presented infantile NPH, with ESRD at a mean age of 2.1±1.07 years. Twenty-seven (30%) patients without NPHP1 developed juvenile NPH, and eight (9%) had adolescent NPH. Age at ESRD is displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Onset of ESRD is depending on the underlying genotype. Survival free of ESRD among children with NPHP1 and without NPHP1 in the Nephronophthisis Registry. Kaplan–Meier analysis of kidney survival highlights the difference between children with NPHP1 (n=58) and children without NPHP1 (n=85). (A) Although in 90% of children with NPHP1, kidney function declined rapidly between 8 and 16 years of age, within the children without NPHP1, there was no uniform pattern regarding the development of CKD. (B) Although most children with NPHP3 and children with IFT140 developed ESRD in infancy or early childhood, in children with NPHP4 and children with NPHP5/IQCB1, (D) ESRD only occurred late within the second decade of life. (C) The data on children with NPHP6/CEP290 and children with NPHP11/TMEM67, however, were inconclusive, including patients with early as well as late ESRD.

Genotype-Phenotype Correlation

NPHP1 (n=60).

Mutations in NPHP1 usually led to juvenile NPH with polyuria starting around the age of 6 years, typical ultrasound findings, and a progressive loss of eGFR. CKD was observed in all but one patient, with the majority of children developing ESRD between 11 and 13 years of age. Of note, this also applied to patients with initially no obvious signs of involvement of the kidneys. These children still developed CKD at a mean age of 10.1±2.8 years and reached ESRD at a mean age of 12.8±1.5 years. Extrarenal involvement was less frequent in NPHP1 compared with non-NPHP1. However, we observed visual impairment in 23%, neurologic symptoms in 25%, and hepatic involvement in 8% of the patients with NPHP1. Only in a small subset did NPHP1 mutations lead to complex ciliopathies, such as Joubert syndrome (n=3) or congenital oculomotor apraxia (n=5) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genotype-phenotype correlation of 89 children in the Nephronophthisis Registry carrying mutations in various ciliary genes

| Genotype | Senior Løken | Joubert | COACH | COMA | Jeune/MSS | CKD | Age at ESRD, yr (1) | Liver Involvement | Ocular Involvement | CNS Involvement | Airways Involvement | Skeletal Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPHP1, n=60 | 7 | 5 | — | 8 | — | 98 | 11.4±2.4 (n=43) | 8 | 41 | 25 | 8 | 2 |

| NPHP3, n=4 | — | — | — | — | — | 100 | 0.7; 4; 8; 10 (n=4) | 100 | 25 | — | 50 | — |

| NPHP4, n=5 | — | — | — | — | — | 100 | 14 (n=1) | — | — | 20 | — | — |

| NPHP5/IQCB1, n=5 | 100 | — | — | — | — | 100 | 14; 16; 16; 27 (n=4) | — | 100 | 20 | — | — |

| NPHP6/CEP290, n=5 | — | 100 | — | — | — | 60 | 7; 21 (n=2) | — | 100 | 100 | 40 | — |

| NPHP11/TMEM67, n=6 | — | 33 | 33 | 17 | — | 67 | 3; 6; 8; 18 (n=4) | 100 | 83 | 83 | — | — |

| IFT140, n=4 | — | — | — | — | 100 | 100 | 7; 10 (n=2) | 25 | 100 | 25 | — | 100 |

Cell contents are the percentages of participants in a given row (genotype) for which the phenotype listed in the column header was observed or the ages (as means±SD or lists of individual ages) at which ESRD developed. COACH, cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, oligophrenia, ataxia, coloboma, hepatic fibrosis; COMA, congenital oculomotor apraxia; MSS, Mainzer–Saldino syndrome; CNS, central nervous system; —, 0% of patients.

NPHP3 (n=4).

The phenotype of all patients with NPHP3 was characterized by a combination of NPH with congenital hepatic fibrosis. Three of four patients presented progressive CKD as the cardinal sign, whereas hepatic fibrosis was diagnosed coincidentally due to concomitant hepatomegaly and/or elevated liver enzymes. In comparison with most other patients with NPH, ESRD occurred at younger ages (Table 2), and the development of kidney cysts was observed early.

NPHP4 (n=5).

The clinical presentation of most patients with NPHP4 was restricted to a kidney phenotype of a urinary concentrating defect and CKD. Despite the rather old age of these patients (12.0±4.4 years), only one developed ESRD (14 years old) so far, suggesting a later onset and/or slower progression compared with other NPHP defects. Extrarenal symptoms were scarce. Nevertheless, in one patient, severe developmental delay was reported.

NPHP5/IQCB1 (n=5).

Senior–Løken syndrome was the typical clinical picture of patients with NPHP5/IQCB1 featuring Leber congenital amaurosis or progressive retinitis pigmentosa in combination with NPH. Although visual impairment usually became obvious within the first year of life, kidney cysts and ESRD developed only during late adolescence. Neurologic symptoms, such as developmental delay and seizures, were reported in one patient; hepatic pathologies were not observed.

NPHP6/CEP290 (n=5).

Patients with NPHP6/CEP290 presented with Joubert syndrome, characterized by a cerebellar vermis hypoplasia and clinical ataxia. Additionally, four of five children were born blind, and one lost vision at 7 years of age. CKD was present in three of five patients, leading to ESRD in two (at 7 and 21 years old, respectively). No hepatic involvement was documented. Two children reported a history of recurrent airway infections.

NPHP11/TMEM67 (n=6).

Patients with NPHP11/TMEM67 displayed variable phenotypes ranging from Joubert syndrome (two of six), COACH syndrome (two of six), and isolated NPH (one of six) to congenital oculomotor apraxia in combination with elevated liver enzymes (one of six). Hepatic fibrosis was found in all children. Ophthalmologic symptoms were reported in 83% (five of six), and visual impairment was reported only in 50% (three of six). CKD was prevalent in four of six patients, with all four displaying cystic lesions and resulting in ESRD.

IFT140 (n=4).

IFT140 mutations have been described to cause skeletal ciliopathies, like Mainzer–Saldino syndrome (27) or syndromic/nonsyndromic retinal dystrophy (28). So far, we were able to identify four patients carrying IFT140 mutations, all featuring skeletal abnormalities, like phalangeal cone–shaped epiphyses (three of four) or asphyxiating thoracic hypoplasia (two of four). Characteristic for Mainzer–Saldino syndrome, all four presented retinal dystrophy manifesting as progressive loss of vision before the age of 10 years old. CKD was observed in all patients, but so far, only two developed ESRD (7 and 10 years old). Kidney cysts were not an obligatory feature; hepatic or neurologic involvement was also not an obligatory feature.

Discussion

High genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity poses a major challenge for clinicians dealing with NPH and related ciliopathies. Although various observational studies and case series have been published before, most of them focused on the genetic rather than the phenotypic presentation (12,13,15,29–31). Prospective data on the natural course of these diseases are limited, especially concerning the deterioration of kidney function and the evolution of extrarenal manifestations. We, therefore, initiated a study of 152 children—among them, a high percentage (49%) of NPH-related ciliopathies—allowing detailed insights into extrarenal organ involvement caused by NPHP mutations.

Despite the tremendous advances in molecular genetics of NPH-related ciliopathies, 60% of patients remain genetically unexplained (7,13). In our cohort, monogenetic defects were identified in 64% of patients, including 14 novel mutations (Supplemental Table 1). The high number of children with NPHP1 mutations might be due to a selection bias, because some centers only reported on genetically solved patients, and routine molecular analysis was limited to NPHP1 until recently. Nevertheless, a detection rate of 39% for homozygous NPHP1 deletions is in line with earlier results (5,9–13,29). The remaining mutations affected only six additional NPHP genes (NPHP3–6 and -11 and IFT140). Because of the registry structure of the study and because not all patients have been tested for all 20 NPHP genes, we cannot fully rule out the possibility that some patients carry mutations in rare NPHP genes that have not been detected yet. However, it is more likely that, in a limited cohort of 152 patients, we did not identify mutations in extremely rare NPHP genes, because the detection rates are very low, ranging between 0.1% and 0.7% (13).

The strength of the registry approach is the detailed focus on the clinical phenotype, including various renal and extrarenal symptoms that have never been asked for in detail before. So far, extrarenal pathologies have been reported in 10%–15% of patients with NPH (15). However, we observed a prevalence of 10%–40% for the NPHP1 group and even 40%–60% in the non-NPHP1 group. Especially in patients with NPHP1, hepatic and neurologic pathologies have been considered rarities so far (18). Thus, it seems noteworthy that 8% of children with NPHP1 presented hepatic symptoms, 19% showed developmental delay, and in 7%, epileptic seizures were reported. In accordance with these observations, Chaki et al. (32) reported neurologic pathologies in 24 of 235 NPHP1 families, and Soliman et al. (33) described a neurologic phenotype in four of 20 patients with NPHP1, mainly characterized as Joubert-like syndromes.

Hence, children with NPHP1 who initially presented an isolated neurologic phenotype were of special interest. We were able to identify eight such patients (three with Joubert syndrome and five with congenital oculomotor apraxia), confirming that homozygous NPHP1 deletions can result in primarily neurologic phenotypes (34,35). Additionally, supporting the observation of Parisi et al. (34), none of our patients with Joubert syndrome showed fetal tachypnea, which otherwise is a typical feature. Irrespective of the primary isolated neurologic presentation, all patients developed ESRD in the long run, which implies that, in the scenario of a homozygous NPHP1 deletion, development of ESRD is inevitable. Furthermore, for the NPHP1 group, we observed a very rapid development of ESRD between 8 and 16 years of age, thereby confirming previous data from a small case series (21).

Interestingly, reduced urinary concentrating capacity and polyuria—usually considered typical hallmarks of juvenile NPH—were only reported in one half of the patients with NPHP1. One possible explanation might be insufficient attention paid to this rather subtle symptom in the scenario of progressive CKD. Nevertheless, polyuria is not a consistent clinical feature in NPH. Pronounced iron-resistant and CKD-independent anemia has been proposed to be an early feature of juvenile NPH (30,36). In our cohort, only 14 individuals—including six children with NPHP1 and six patients with Joubert/COACH syndrome—presented anemia before developing advanced CKD. In all others, anemia was associated with CKD stages 4 and 5.

Because of the naturally limited number of patients and an up to now restricted access to modern sequencing techniques, data on NPHP3 to -20 mutations are still insufficient to generate solid genotype-phenotype correlations. Nevertheless, some trends seem to emerge. Different genetic defects of NPHP3 have been reported to result in either adolescent-onset (37,38) or more often, infantile NPH (31,39). Furthermore, liver involvement is a common finding in patients with NPHP3 (13,38). Thus, including our results, we recommend a detailed liver examination in all patients with infantile NPH and consideration of NPHP3 whenever NPH is associated with congenital liver fibrosis. In contrast, NPHP4 mutations should be considered in patients with isolated juvenile or adolescent NPH in whom a homozygous NPHP1 deletion has been excluded (32).

Early-onset blindness is a key feature of both NPHP5/IQCB1 and NPHP6/CEP290 mutations. In patients with NPHP5/IQCB1, the phenotype is usually limited to a Senior–Løken syndrome made up of Leber congenital amaurosis and juvenile NPH (40,41). Neurologic abnormalities are not common (32). However, one of our patients presented significant developmental delay, reduced emotional control, and seizures. Because his also affected older brother showed no neurologic signs at all, it remains unclear whether the neurologic symptoms are related to the NPHP5/IQCB1 defect. In contrast, NPHP6/CEP290 mutations can cause a large variety of multivisceral pathologies ranging from isolated NPH to lethal Meckel–Gruber syndrome (42–45). Our patients with NPHP6/CEP290 all presented the typical features of Joubert syndrome, which is referred to as the most common clinical manifestation (32,42,43). CKD was not an obligatory feature, and neither was hepatic involvement, which seems to be extremely rare in patients with NPHP6/CEP290 (32).

The unifying characteristic of patients with NPHP11/TMEM67 is hepatic fibrosis (32,46). Apart from that, the clinical picture can be highly variable. Two of our patients have to be highlighted. The first patient is an 8-year-old boy carrying two missense mutations who presented with congenital oculomotor apraxia and elevated liver enzymes. To our knowledge, this is the first description of the NPHP11/TMEM67 mutations being a cause of congenital oculomotor apraxia. The second patient presented with typical Joubert syndrome but without liver involvement. However, only one heterozygous NPHP11/TMEM67 splice site mutation was identified, with no second disease-causing gene mutation. Thus, it remains unclear whether the clinical picture is caused by a compound heterozygous condition with an unidentified second mutation or whether this patient carries additional mutations in another gene.

Considering the pathogenic effect of NPHP mutations on primary cilia, one could expect a comparable effect on motile cilia as well. Motile cilia are mainly expressed in the upper airway epithelium, and disorders of motile cilia function result in recurrent respiratory tract infections as well as restrictive lung disease. However, in our cohort, only a few patients reported recurrent ear and/or upper airway infections (eight of 152), and numbers are still too small to draw conclusions. Further investigations are needed to answer the questions of whether NPHP mutations have a direct effect on motile cilia and whether this could be disease causing.

The phenotypic spectrum of ciliopathies caused by NPHP gene mutations is highly variable, and neither gene locus heterogeneity nor the nature of mutations can fully explain the clinical variety observed in affected individuals—sometimes even within the same family. Therefore, clinical registries, such as the NEPHREG, are of outstanding importance to provide longitudinal data that can help clinicians in counseling affected patients and their families. Beyond that, the NEPHREG supplies a clinical platform that may inform new therapeutic approaches to be tested in clinical trials with a collaborative network.

Disclosures

C.B. is an employee of Bioscientia. All other authors have no financial disclosures regarding this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating patients. Also, we thank the following colleagues for contributing their patients: Bärbel Lange-Sperandio, Martin Koemhoff, Michael van Husen, Ludwig Patzer, Dominic Müller, Lutz Weber, and Johannes Stoffels. Furthermore, we thank Sabine Kollmann for her help on data analysis. Finally, we thank all Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Nephrologie members for their helpful feedback and continuous support.

This study was supported by German Federal Government Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Förderkennzeichen grant 01GM1515A.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “A Perspective on Inherited Kidney Disease: Lessons for Practicing Nephrologists,” on pages 1914–1916.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.01280217/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.König J, Ermisch-Omran B, Omran H: Nephronophthisis and autosomal dominant interstitial kidney disease (ADIKD). In: Pediatric Kidney Diseases, 2nd Ed., edited by Geary DF, Schaefer F, Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 369–386, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fanconi G, Hanhart E, von ALBERTINI A, Uhlinger E, Dolivo G, Prader A: [Familial, juvenile nephronophthisis (idiopathic parenchymal contracted kidney)]. Helv Paediatr Acta 6: 1–49, 1951 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith C, Graham J: Congenital medullary cysts of the kidneys with severe refractory anemia. Am J Dis Child 69: 369–377, 1945 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saunier S, Salomon R, Antignac C: Nephronophthisis. Curr Opin Genet Dev 15: 324–331, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildebrandt F, Zhou W: Nephronophthisis-associated ciliopathies. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1855–1871, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pistor K, Olbing H, Schärer K: Children with chronic renal failure in the Federal Republic of Germany. I. Epidemiology, modes of treatment, survival. Arbeits- gemeinschaft für Pädiatrische Nephrologie. Clin Nephrol 23: 272–277, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf MT: Nephronophthisis and related syndromes. Curr Opin Pediatr 27: 201–211, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macia MS, Halbritter J, Delous M, Bredrup C, Gutter A, Filhol E, Mellgren AEC, Leh S, Bizet A, Braun DA, Gee HY, Silbermann F, Henry C, Krug P, Bole-Feysot C, Nitschké P, Joly D, Nicoud P, Paget A, Haugland H, Brackmann D, Ahmet N, Sandford R, Cengiz N, Knappskog PM, Boman H, Linghu B, Yang F, Oakeley EJ, Saint Mézard P, Sailer AW, Johansson S, Rødahl E, Saunier S, Hildebrandt F, Benmerah A: Mutations in MAPKBP1 cause juvenile or late-onset cilia-independent nephronophthisis. Am J Hum Genet 100: 323–333, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antignac C, Arduy CH, Beckmann JS, Benessy F, Gros F, Medhioub M, Hildebrandt F, Dufier JL, Kleinknecht C, Broyer M, Weissenbach J, Habib R, Cohen D: A gene for familial juvenile nephronophthisis (recessive medullary cystic kidney disease) maps to chromosome 2p. Nat Genet 3: 342–345, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konrad M, Saunier S, Heidet L, Silbermann F, Benessy F, Calado J, Le Paslier D, Broyer M, Gubler MC, Antignac C: Large homozygous deletions of the 2q13 region are a major cause of juvenile nephronophthisis. Hum Mol Genet 5: 367–371, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saunier S, Calado J, Benessy F, Silbermann F, Heilig R, Weissenbach J, Antignac C: Characterization of the NPHP1 locus: Mutational mechanism involved in deletions in familial juvenile nephronophthisis. Am J Hum Genet 66: 778–789, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hildebrandt F, Otto E, Rensing C, Nothwang HG, Vollmer M, Adolphs J, Hanusch H, Brandis M: A novel gene encoding an SH3 domain protein is mutated in nephronophthisis type 1. Nat Genet 17: 149–153, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halbritter J, Porath JD, Diaz KA, Braun DA, Kohl S, Chaki M, Allen SJ, Soliman NA, Hildebrandt F, Otto EA; GPN Study Group : Identification of 99 novel mutations in a worldwide cohort of 1,056 patients with a nephronophthisis-related ciliopathy. Hum Genet 132: 865–884, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fliegauf M, Benzing T, Omran H: When cilia go bad: Cilia defects and ciliopathies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 880–893, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hildebrandt F, Attanasio M, Otto E: Nephronophthisis: Disease mechanisms of a ciliopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 23–35, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hildebrandt F, Benzing T, Katsanis N: Ciliopathies. N Engl J Med 364: 1533–1543, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simms RJ, Hynes AM, Eley L, Sayer JA: Nephronophthisis: A genetically diverse ciliopathy. Int J Nephrol 2011: 527137, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf MT, Hildebrandt F: Nephronophthisis. Pediatr Nephrol 26: 181–194, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benzing T, Schermer B: Clinical spectrum and pathogenesis of nephronophthisis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 21: 272–278, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gusmano R, Ghiggeri GM, Caridi G: Nephronophthisis-medullary cystic disease: Clinical and genetic aspects. J Nephrol 11: 224–228, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hildebrandt F, Strahm B, Nothwang HG, Gretz N, Schnieders B, Singh-Sawhney I, Kutt R, Vollmer M, Brandis M: Molecular genetic identification of families with juvenile nephronophthisis type 1: Rate of progression to renal failure. APN Study Group. Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Pädiatrische Nephrologie. Kidney Int 51: 261–269, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salomon R, Saunier S, Niaudet P: Nephronophthisis. Pediatr Nephrol 24: 2333–2344, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolignano D, Nagler EV, Van Biesen W, Zoccali C: Providing guidance in the dark: Rare renal diseases and the challenge to improve the quality of evidence. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 1628–1632, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoff S, Halbritter J, Epting D, Frank V, Nguyen TM, van Reeuwijk J, Boehlke C, Schell C, Yasunaga T, Helmstädter M, Mergen M, Filhol E, Boldt K, Horn N, Ueffing M, Otto EA, Eisenberger T, Elting MW, van Wijk JA, Bockenhauer D, Sebire NJ, Rittig S, Vyberg M, Ring T, Pohl M, Pape L, Neuhaus TJ, Elshakhs NA, Koon SJ, Harris PC, Grahammer F, Huber TB, Kuehn EW, Kramer-Zucker A, Bolz HJ, Roepman R, Saunier S, Walz G, Hildebrandt F, Bergmann C, Lienkamp SS: ANKS6 is a central component of a nephronophthisis module linking NEK8 to INVS and NPHP3. Nat Genet 45: 951–956, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou W, Otto EA, Cluckey A, Airik R, Hurd TW, Chaki M, Diaz K, Lach FP, Bennett GR, Gee HY, Ghosh AK, Natarajan S, Thongthip S, Veturi U, Allen SJ, Janssen S, Ramaswami G, Dixon J, Burkhalter F, Spoendlin M, Moch H, Mihatsch MJ, Verine J, Reade R, Soliman H, Godin M, Kiss D, Monga G, Mazzucco G, Amann K, Artunc F, Newland RC, Wiech T, Zschiedrich S, Huber TB, Friedl A, Slaats GG, Joles JA, Goldschmeding R, Washburn J, Giles RH, Levy S, Smogorzewska A, Hildebrandt F: FAN1 mutations cause karyomegalic interstitial nephritis, linking chronic kidney failure to defective DNA damage repair. Nat Genet 44: 910–915, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blowey DL, Querfeld U, Geary D, Warady BA, Alon U: Ultrasound findings in juvenile nephronophthisis. Pediatr Nephrol 10: 22–24, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perrault I, Saunier S, Hanein S, Filhol E, Bizet AA, Collins F, Salih MA, Gerber S, Delphin N, Bigot K, Orssaud C, Silva E, Baudouin V, Oud MM, Shannon N, Le Merrer M, Roche O, Pietrement C, Goumid J, Baumann C, Bole-Feysot C, Nitschke P, Zahrate M, Beales P, Arts HH, Munnich A, Kaplan J, Antignac C, Cormier-Daire V, Rozet JM: Mainzer-Saldino syndrome is a ciliopathy caused by IFT140 mutations. Am J Hum Genet 90: 864–870, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bifari IN, Elkhamary SM, Bolz HJ, Khan AO: The ophthalmic phenotype of IFT140-related ciliopathy ranges from isolated to syndromic congenital retinal dystrophy. Br J Ophthalmol 100: 829–833, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halbritter J, Diaz K, Chaki M, Porath JD, Tarrier B, Fu C, Innis JL, Allen SJ, Lyons RH, Stefanidis CJ, Omran H, Soliman NA, Otto EA: High-throughput mutvaation analysis in patients with a nephronophthisis-associated ciliopathy applying multiplexed barcoded array-based PCR amplification and next-generation sequencing. J Med Genet 49: 756–767, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ala-Mello S, Kivivuori SM, Rönnholm KA, Koskimies O, Siimes MA: Mechanism underlying early anaemia in children with familial juvenile nephronophthisis. Pediatr Nephrol 10: 578–581, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson MA, Cross HE, Cross L, Helmuth M, Crosby AH: Lethal cystic kidney disease in Amish neonates associated with homozygous nonsense mutation of NPHP3. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 790–795, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaki M, Hoefele J, Allen SJ, Ramaswami G, Janssen S, Bergmann C, Heckenlively JR, Otto EA, Hildebrandt F: Genotype-phenotype correlation in 440 patients with NPHP-related ciliopathies. Kidney Int 80: 1239–1245, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soliman NA, Hildebrandt F, Otto EA, Nabhan MM, Allen SJ, Badr AM, Sheba M, Fadda S, Gawdat G, El-Kiky H: Clinical characterization and NPHP1 mutations in nephronophthisis and associated ciliopathies: A single center experience. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 23: 1090–1098, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parisi MA, Bennett CL, Eckert ML, Dobyns WB, Gleeson JG, Shaw DW, McDonald R, Eddy A, Chance PF, Glass IA: The NPHP1 gene deletion associated with juvenile nephronophthisis is present in a subset of individuals with Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 75: 82–91, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caridi G, Dagnino M, Rossi A, Valente EM, Bertini E, Fazzi E, Emma F, Murer L, Verrina E, Ghiggeri GM: Nephronophthisis type 1 deletion syndrome with neurological symptoms: Prevalence and significance of the association. Kidney Int 70: 1342–1347, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stokman M, Lilien M, Knoers N: Nephronophthisis. In: GeneReviews, edited by Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJH, Bird TD, Ledbetter N, Mefford HC, Smith RJH, Stephens K, Seattle, WA, University of Washington, 2016, pp 1993–2017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Omran H, Fernandez C, Jung M, Häffner K, Fargier B, Villaquiran A, Waldherr R, Gretz N, Brandis M, Rüschendorf F, Reis A, Hildebrandt F: Identification of a new gene locus for adolescent nephronophthisis, on chromosome 3q22 in a large Venezuelan pedigree. Am J Hum Genet 66: 118–127, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olbrich H, Fliegauf M, Hoefele J, Kispert A, Otto E, Volz A, Wolf MT, Sasmaz G, Trauer U, Reinhardt R, Sudbrak R, Antignac C, Gretz N, Walz G, Schermer B, Benzing T, Hildebrandt F, Omran H: Mutations in a novel gene, NPHP3, cause adolescent nephronophthisis, tapeto-retinal degeneration and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Genet 34: 455–459, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tory K, Rousset-Rouvière C, Gubler MC, Morinière V, Pawtowski A, Becker C, Guyot C, Gié S, Frishberg Y, Nivet H, Deschênes G, Cochat P, Gagnadoux MF, Saunier S, Antignac C, Salomon R: Mutations of NPHP2 and NPHP3 in infantile nephronophthisis. Kidney Int 75: 839–847, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Otto EA, Loeys B, Khanna H, Hellemans J, Sudbrak R, Fan S, Muerb U, O’Toole JF, Helou J, Attanasio M, Utsch B, Sayer JA, Lillo C, Jimeno D, Coucke P, De Paepe A, Reinhardt R, Klages S, Tsuda M, Kawakami I, Kusakabe T, Omran H, Imm A, Tippens M, Raymond PA, Hill J, Beales P, He S, Kispert A, Margolis B, Williams DS, Swaroop A, Hildebrandt F: Nephrocystin-5, a ciliary IQ domain protein, is mutated in Senior-Loken syndrome and interacts with RPGR and calmodulin. Nat Genet 37: 282–288, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stone EM, Cideciyan AV, Aleman TS, Scheetz TE, Sumaroka A, Ehlinger MA, Schwartz SB, Fishman GA, Traboulsi EI, Lam BL, Fulton AB, Mullins RF, Sheffield VC, Jacobson SG: Variations in NPHP5 in patients with nonsyndromic leber congenital amaurosis and Senior-Loken syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 129: 81–87, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coppieters F, Lefever S, Leroy BP, De Baere E: CEP290, a gene with many faces: Mutation overview and presentation of CEP290base. Hum Mutat 31: 1097–1108, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valente EM, Silhavy JL, Brancati F, Barrano G, Krishnaswami SR, Castori M, Lancaster MA, Boltshauser E, Boccone L, Al-Gazali L, Fazzi E, Signorini S, Louie CM, Bellacchio E, Bertini E, Dallapiccola B, Gleeson JG; International Joubert Syndrome Related Disorders Study Group : Mutations in CEP290, which encodes a centrosomal protein, cause pleiotropic forms of Joubert syndrome. Nat Genet 38: 623–625, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leitch CC, Zaghloul NA, Davis EE, Stoetzel C, Diaz-Font A, Rix S, Alfadhel M, Lewis RA, Eyaid W, Banin E, Dollfus H, Beales PL, Badano JL, Katsanis N: Hypomorphic mutations in syndromic encephalocele genes are associated with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nat Genet 40: 443–448, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bergmann C: Educational paper: Ciliopathies. Eur J Pediatr 171: 1285–1300, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Otto EA, Tory K, Attanasio M, Zhou W, Chaki M, Paruchuri Y, Wise EL, Wolf MT, Utsch B, Becker C, Nürnberg G, Nürnberg P, Nayir A, Saunier S, Antignac C, Hildebrandt F: Hypomorphic mutations in meckelin (MKS3/TMEM67) cause nephronophthisis with liver fibrosis (NPHP11). J Med Genet 46: 663–670, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.