Abstract

Rationale

Intercellular uncoupling and Ca mishandling can initiate triggered ventricular arrhythmias. Spontaneous Ca release activates inward current which depolarizes membrane potential (Vm) and can trigger action potentials in isolated myocytes. However, cell-cell coupling in intact hearts limits local depolarization and may protect hearts from this arrhythmogenic mechanism. Traditional optical mapping lacks the spatial resolution to assess coupling of individual myocytes.

Objective

We investigate local intercellular coupling in Ca-induced depolarization in intact hearts, using confocal microscopy to measure local Vm and intracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca]i) simultaneously.

Methods and Results

We used isolated Langendorff-perfused hearts from control (CTL) and HF mice (HF induced by trans-aortic constriction). In CTL hearts, 1.4 % of myocytes were poorly synchronized with neighboring cells and exhibited asynchronous Ca2+ transients (AS). These AS myocytes were much more frequent in HF (10.8% of myocytes, p<0.05 vs. CTL). Local Ca waves depolarized Vm in HF but not CTL hearts, suggesting weaker gap junction coupling in HF-AS vs. CTL-AS myocytes. Cell-cell coupling was assessed by calcein fluorescence recovery after photobleach (FRAP) during [Ca]i recording. All regions in CTL hearts exhibited faster calcein diffusion than in HF, with HF-AS myocyte being slowest. In HF-AS, enhancing gap junction conductance (with rotigaptide) increased coupling and suppressed Vm depolarization during Ca waves. Conversely, in CTL hearts, gap junction inhibition (carbenoxolone) decreased coupling and allowed Ca-wave-induced depolarizations. Synchronization of Ca wave initiation and triggered action potentials were observed in HF hearts and computational models.

Conclusions

Well-coupled CTL myocytes are effectively voltage-clamped during Ca waves, protecting the heart from triggered arrhythmias. Spontaneous Ca waves are much more common in HF myocytes and these AS myocytes are also poorly coupled, enabling local Ca-induced inward current of sufficient source strength to overcome a weakened current sink to depolarize Vm and trigger action potentials.

Keywords: Heart failure, triggered activity, synchronization, Ca handling, gap junction, fluorescent recovery after photo-bleaching, extrasystole, premature ventricular contraction, premature ventricular beats, arrythmia

Subject Terms: Arrhythmias, Basic Science Research, Calcium cycling/Excitation-Contraction Coupling, Electrophysiology

INTRODUCTION

In the heart, cardiomyocytes are mechanically and electrically coupled to produce coordinated contractions. However, in pathological conditions, ill-timed propagation of ectopic ventricular beats can contribute to fatal arrhythmias.1–3 Non-electrically driven Ca release can be a critical factor in the development of ventricular focal excitations, especially in heart failure (HF),4,5 where Ca handling dysfunction is common.6–8 Indeed, in HF there is increased diastolic sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca leak and Ca waves that are proarrhythmic.5,8–12 Diastolic SR Ca leak via ryanodine receptors (RyRs) can lead to propagating Ca waves in myocytes.12–14 These Ca waves drive extrusion of Ca from the myocyte via Na+/Ca2+ exchange (NCX) current (INCX) that causes membrane potential (Vm) depolarization and delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs). If of sufficient magnitude, these DADs may trigger an action potential (AP) in the myocyte and potentially triggered activity or premature ventricular contraction (PVC) in the whole heart.9–14 Therefore, myocytes with spontaneous Ca release will present unsynchronized Ca dynamics to neighboring myocytes, but also may generate electrical asynchrony.

Detailed analysis of DADs and Ca-triggered APs has been largely conducted in isolated myocytes and has been mechanistically informative.10,11,15–17 However, in the intact heart, myocytes are electrically coupled to many neighbors, and that can greatly influence the effect that the Ca-dependent INCX has on local Vm. Indeed, a single myocyte undergoing a Ca wave may produce a local inward INCX that would tend to depolarize itself and its neighbors, as a current source. But the large number of myocytes to which that cell is attached and electrically coupled, creates a significant current sink that may distribute that current source so broadly in space that the local depolarization, even in the initiating myocyte, is minimal.

A quantitative theoretical consideration of this issue by Xie et al.1 estimated the number of local myocyte DADs that would need to be synchronized to induce a PVC. The myocyte number in the normal heart model was very large, but the conditions associated with HF (e.g., increased NCX, reduced IK1 and gap junction uncoupling)11,18–23 decreased the number of myocytes required to overcome the normal source-sink mismatch that prevents a single myocyte Ca wave from triggering a PVC. Parallel whole heart optical mapping experiments with micro-injection of norepinephrine to induce locally synchronized SR Ca release under different HF-related conditions were in qualitative agreement with these modeling predictions.24,25 However, the spatial resolution of whole heart optical mapping, as is typically used to study these arrhythmogenic events,24–28 does not allow observation of local [Ca]i or Vm at the level of single myocytes.

Several groups have used confocal [Ca]i imaging of small groups of myocytes in the intact heart, and this allows the spatial resolution to measure individual myocyte behavior within a syncytium.29–33 We developed a confocal imaging platform capable of simultaneous [Ca]i and Vm measurements in individual myocytes within intact Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts. This set-up also allows simultaneous measurement of [Ca]i and direct measurements of local cell-cell-coupling via calcein fluorescence recovery after photobleach (FRAP).

We observed occasional individual myocytes in the heart that did not synchronize with all other visible myocytes during pacing-induced activation, and these asynchronous or rogue myocytes often exhibited independent spontaneous Ca transients (as waves). These Ca asynchronous myocytes were much more common in hearts in which HF had been induced by trans-aortic constriction. We hypothesized that these Ca asynchronous myocytes contribute to electrical asynchrony, especially in conditions such as HF. In control (CTL) hearts, myocytes exhibiting asynchronous Ca waves were well coupled to their neighbors, such that no depolarization was detectable during Ca waves. In contrast, asynchronous Ca waves in HF myocytes caused substantial depolarization during Ca waves (including in nearby cells), but these cells were only poorly coupled with neighboring myocytes. We conclude that regions with poorly coupled HF myocytes may allow local Ca-induced inward currents to overcome normal source-sink mismatching to propagate depolarization and triggered action potentials.

METHODS

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis and adhered to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Experiments were conducted on normal adult male C57BL/6 mice (CTL: n=15) and mice in which HF had been induced by 8 weeks of transverse aortic constriction (TAC) by previously established techniques (HF: n=14).34 HF progression was verified by echocardiographic analysis and heart weight to body weight ratios upon cardiac excision. The HF mice used exhibited ~50% reduction in ejection fraction and fractional shortening, and wall thickening (Online Figure I).

Ca-Vm coupling study in intact heart

A custom-made Langendorff system was positioned on an Olympus FluoView™ 1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA). Hearts from CTL (n=9) and HF (n=8) mice were superfused and retrogradely perfused via the aorta with oxygenated normal Tyrode’s solution (NT; in mmol/L: 128.2 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.19 NaH2PO4, 1.05 MgCl2, 1.3 CaCl2, 20.0 NaHCO3, and 11.1 glucose, and gassed with 95% O2−5% CO2; pH=7.35±0.05), In most experiments the sino-atrial node and atrio-ventricular node was intentionally crushed to slow the intrinsic heart rate.

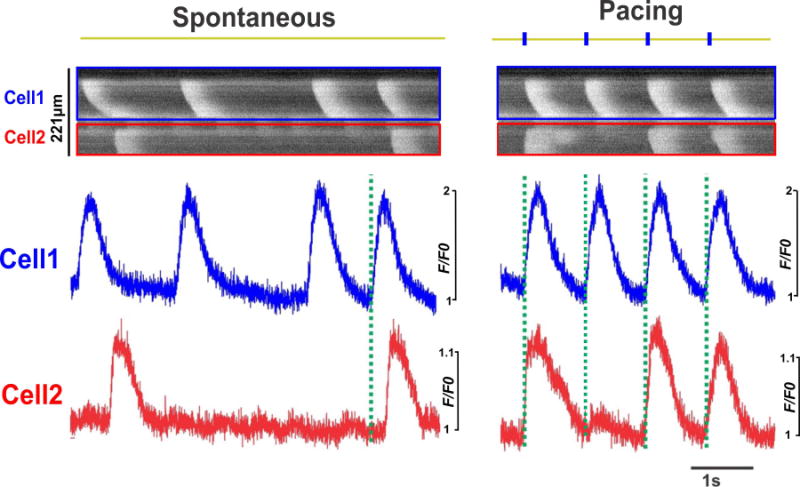

Hearts were simultaneously stained with the Vm indicator RH237 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA; 10 μmol/L) and the Ca indicator Fluo-8 AM (Teflab, Austin, TX; 10 μmol/L) to investigate the Ca-Vm coupling at room temperature. Blebbistatin (Abcam Biochemicals, Cambridge, MA; 10–20 μmol/L) was used to eliminate motion artifacts during imaging. After 10~20 min stabilization of the heart, 4 field-of-view images under 40×/1.3 N.A. oil-immersion objective, pin-hole of 100nm, were acquired randomly from different areas on the ventricular free wall epicardium to evaluate the occurrence cardiomyocytes with asynchronous Ca waves. For such cells, line-scan mode imaging was then used under 60×/1.42 N.A. oil-immersion objective (0.414 μm/pixel) with scanning speed 2 μs/pixel for both Vm (excited at 559nm; emission at >700nm) and Ca (excited at 488nm; emission at 525±20 nm) channels. As the fluorescent intensity for RH237 decreases upon depolarization, these signals were displayed inverted (except as indicated). A typical simultaneous recording is presented in Figure 1A where action potentials (APs: red) and Ca transients (CaTs: gray) were well-coupled as indicated by time-aligned signals.

Figure 1. Ca asynchronous myocytes in the intact hearts.

A). Confocal 2D and line scan images of Langendorff perfused intact mouse heart simultaneously stained with Fluo-8 AM (gray) and RH237 (red). Integrated signals from line scan images show precise time alignment of beat-to-beat AP and Ca transients. B). Images of intact hearts simultaneously stained with Calcein AM (green) and Rhod-2 AM (gray). Line scan imaging showed no effects of Ca transients on calcein fluorescence. C & D). An asynchronous myocyte (cell 3,yellow arrow) showed spontaneous Ca waves, while adjacent myocytes (cells 1, 2, 4 & 5) synchronously follow the heart rhythm. E). Asynchronous myocytes were detected under baseline condition in both groups of hearts. The percentage of AS cells was calculated as number of AS cells normalized to total cells in the field of view. In HF hearts 10.8% of the 1,204 cells monitored were asynchronous (130 HF-AS). In CTL hearts only 1.4% of the 1,143 myocytes observed were asynchronous (16 CTL-AS myocytes); p<0.05 by Fisher’s exact test.

Validation of the recording methods is shown in Online Figure II–III. Recording of Vm and [Ca]i was sequential (9 ms delay). During separate excitation, there was negligible interference between Fluo-8 AM and RH237 signals (Online Figure II) indicating lack of crosstalk between these signals during experiments. Typical recordings of CaT under different pacing frequency and premature ventricular contractions detected in the individual myocytes from the intact heart are presented in Online Figure III.

Fluorescence recovery after photo-bleaching (FRAP) in intact hearts to functionally assess gap junction coupling

Similar to the Ca-Vm study, isolated CTL (n=6) and HF (n=6) mouse hearts were also superfused and retrogradely perfused with oxygenated NT and stabilized for 10~20 min, but in this case hearts were stained with Rhod-2 AM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA; 10 μmol/L; excited at 559nm; emission at 595±15nm) to assess [Ca]i dynamics and Calcein AM (TEFLabs, Austin, TX; 10 μmol/L; excited at 488nm; emission at 525±20nm) to assess function of gap junctions (indicated by the recovery of calcein fluorescence in bleached myocytes).35,36 A representative control recording (Figure 1B) shows no change in the calcein channel (green) during beat-to-beat CaTs imaged with Rhod-2 AM channel (gray). FRAP experiments were conducted similar to those by Abbaci et, al.36 Briefly, 4 time sequence 2D-images (40×/1.3 N.A. oil-immersion objective: 512×512 pixels at resolution of 0.621μm/pixel) were acquired to measure baseline fluorescence (interval of 15s). Calcein photo-bleaching was conducted on a target myocyte via argon ion laser (488 nm) at 100% power for 100s. Imaging demonstrated that bleach was well-confined to that myocyte in the x-y plane. Despite restricted confocal illumination, slight bleach in one or two adjacent myocytes beneath the target cell (in the z-direction) cannot be ruled out. While this may limit estimates of diffusion coefficients, the effects are similar across all FRAP experiments, and should not influence relative FRAP. A time lapse series was then acquired to record calcein FRAP in the target myocyte using 1% power at indicated time intervals for CTL and HF hearts (200–300 cycles). Detailed analyses are described in supplemental materials.

ECG recordings

ECG was recorded by a pair of 4mm Ag/AgCl pads during the stabilization time before loading the dyes in this study.

Experimental protocol

In both the Ca-Vm coupling study and gap junction FRAP experiments, the gap junction uncoupler carbenoxolone (CBX; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; 25μmol/L)32 or Ik1 blocker BaCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; 5 μmol/L)37 were delivered by aortic perfusion into hearts. The gap junction modifier rotigaptide (ZP123; 50nmol/L), which is reported to increase gap junctional conductance,38,39 was perfused into HF hearts. Ca-Vm coupling experiments were also conducted on the isolated myocytes.

Cardiomyocyte isolation, staining and confocal imaging

Cardiac ventricular myocytes were isolated from adult male C57bL/6 mice (CTL, n=2) as previously described.40 Briefly, hearts were removed and retrogradely Langendorff perfused with type 2 collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ) to isolate cardiac ventricular myocytes, with gradual [Ca]o increase to 1 mmol/L at room temperature. Freshly isolated myocytes were plated on laminin-coated glass cover slip for 15 min before dye loading (with 10 μmol/L Fluo-8 AM for 15 min followed by 20 min wash out in Tyrode’s). Cells were then stained with 10 μmol/L RH237 for 5 min and washout. Imaging was then applied under 60×/1.42 N.A. oil-immersion objective using Olympus FluoView™ 1000 confocal microscopy system. All settings are as described in Ca-Vm intact heart study.

Computational modeling

We use our previous detailed stochastic AP and Ca handling myocyte model, with ~20,000 individually stochastic SR junctional SR Ca release units per myocyte, and 10,000 myocytes in a 2-dimensional array (1.5 × 1.5 cm) coupled via physiological gap junctional conductance.41–43 Some of the rabbit model parameters were adjusted to reflect HF phenotype (e.g. reduced levels of some K+ currents, increased NCX and increased RyR sensitivity) and increased SERCA2 activity to mimic mouse vs. rabbit differences and spontaneous Ca-transients in some cells. Further model details are presented in the Online Supplement.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are shown as mean±SEM. Fisher’s exact test and one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc tests were applied where appropriate. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Technical limitations

We did not perform photo-bleaching of myocytes adjacent to asynchronous myocytes because subsequent bleaching of a neighboring cell would complicate results and interpretation. Thus, FRAP measurements in both asynchronous and adjacent cells were not performed. As with most Ca/Vm imaging in intact hearts, quantitative calibration of Vm and [Ca]i was not possible, therefore we cannot compare absolute baseline diastolic Vm or [Ca]i levels of AS with SY cells.

RESULTS

Asynchronous Ca release in failing ventricular myocardium

In the intact heart, healthy ventricular myocytes are normally well coupled and exhibit well-synchronized local electrical activity (AP) and Ca transients (CaTs; Figure 1A). However, a small number of myocytes (even in CTL hearts) exhibited asynchronous CaTs which appeared not to affect neighboring myocytes. Such rogue cells could be single asynchronous myocytes, coupled asynchronous myocytes, or whole areas of asynchronous myocytes. Figure 1C shows consecutive 2D confocal images of CaTs recorded from the intact ventricle, with a Ca asynchronous myocyte (cell3) highlighted by a yellow box. Figure 1D is a line scan image along the green dotted line through five neighboring cells in Figure 1C. Individual myocyte spatially integrated CaTs are shown for the asynchronous myocyte (cell3) and the adjacent myocyte that is synchronized with the other neighboring myocytes (cell4). Cell 3 presented spontaneous Ca waves (arrows in Figure 1C and 1D) while the neighboring cells (both in the longitudinal and transverse directions) were at the overall rhythm. Such Ca asynchronous (AS) ventricular myocytes were observed in both CTL and HF mouse hearts but with dramatically different incidence. Only 1.4% of myocytes in fields studied were Ca asynchronous in CTL hearts while 10.8% of cells were Ca asynchronous in HF hearts (Figure 1E).

Ca waves cause depolarization in asynchronous myocytes only in HF hearts

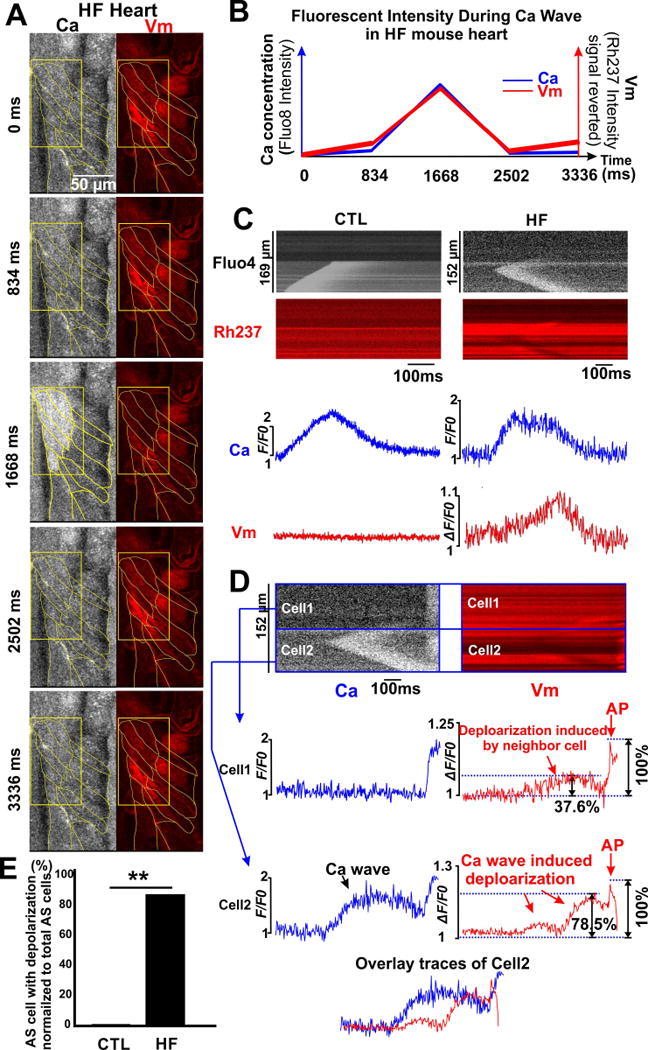

Importantly, in CTL hearts, spontaneous Ca waves in asynchronous myocytes did not result in detectable local Vm depolarizations (presumably because Vm in those myocytes was effectively clamped by gap junctional coupling to the neighboring myocytes). However, in HF, we observed two distinct types of Ca waves: one occurred without Vm changes (like CTL) and the other associated with detectable Vm depolarizations. Figure 2A is a series of consecutive 2D images where the decrease of RH237 fluorescence (depolarization) was detected in the same cells simultaneous with increased [Ca2+]i (measured with Fluo-8) during spontaneous and synchronized Ca waves. The signal from a selected cluster of myocytes (yellow box) in Figure 2A, was integrated, normalized and plotted in Figure 2B, for both [Ca2+]i and Vm. Even at the low scan rate attainable in 2D, the changes coincide in time. A full recording is in the Online Video.

Figure 2. Ca waves induce depolarization of membrane potential in HF hearts.

A). 2D confocal image captured Ca wave-induced Vm depolarization in the intact hearts. At time point 1668 ms, spontaneous Ca release is indicated by increased Fluo-8 fluorescent intensity (white) simultaneously with Vm depolarization (decrease of RH237 fluorescence, red). B). Fluorescent intensity of each signal in A) was integrated and plotted vs. time. C). Line scan of asynchronous (AS) myocytes exhibiting Ca waves in CTL and HF hearts. Depolarization was only observed in HF (n=23) but not WT hearts. D). HF-AS cells not only depolarize themselves, but also neighboring cells. Such depolarization was greater in the AS cell (cell2: 78.5% of its AP amplitude) vs. neighbor cell1 (37.6% of its AP amplitutde). E). None of the observed CTL-AS cells exhibited depolarization during Ca waves, whereas 87.5% of the HF-AS cells oberved exhibited detectable depolarization as Ca waves occured.

To increase temporal resolution for such Ca waves and Vm depolarizations, we used line scanning (Figure 2C–D). The CTL myocyte in Figure 2C (left) exhibits a clear Ca wave, but no detectable depolarization, while the HF myocyte (right) exhibits a Ca wave that induced a clear depolarization which peaks with some delay. This suggests that Vm depolarization was induced by the Ca wave. Such Ca wave-induced Vm depolarization was only observed in Ca AS myocytes in HF hearts (not in CTL hearts). These Ca-induced depolarizations were seen in the majority of HF-AS myocytes (87.6% in HF-AS cells vs. 0% in CTL-AS, p<0.01, Figure 2E). It should be emphasized that in contrast to the intact heart, in isolated myocytes, Ca waves always induced Vm depolarization, in CTL and HF groups (Online Figure IV). This agrees with previous isolated myocyte studies, where SR Ca release drives an inward INCX to initiate delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs).9,11,15 This inward INCX surely occurs in both cases in Figure 2C, but in CTL the inward current is well-absorbed by the cells to which it is coupled via gap junctions. Conversely, the HF myocytes may have weaker gap junctional coupling, allowing local depolarization.

In another HF heart (Figure 2D) asynchronous Cell2 exhibits a Ca wave that does not propagate at all to Cell1. However, the consequent depolarization in Cell2 does propagate to Cell1. Moreover, this depolarization is sufficient to trigger an AP in both myocytes near the end of this trace (manifest also on the Ca trace as a spatially synchronous Ca transient). Note that the depolarization level in Cell1 (prior to the AP) is only around half of that seen in Cell2, when normalized to AP peak vs. diastole (i.e. 78.5% of AP level in the AS Cell2 vs. 37.6% in neighboring Cell1). We conclude that these AS HF myocytes have significant, yet reduced coupling to neighboring cells.

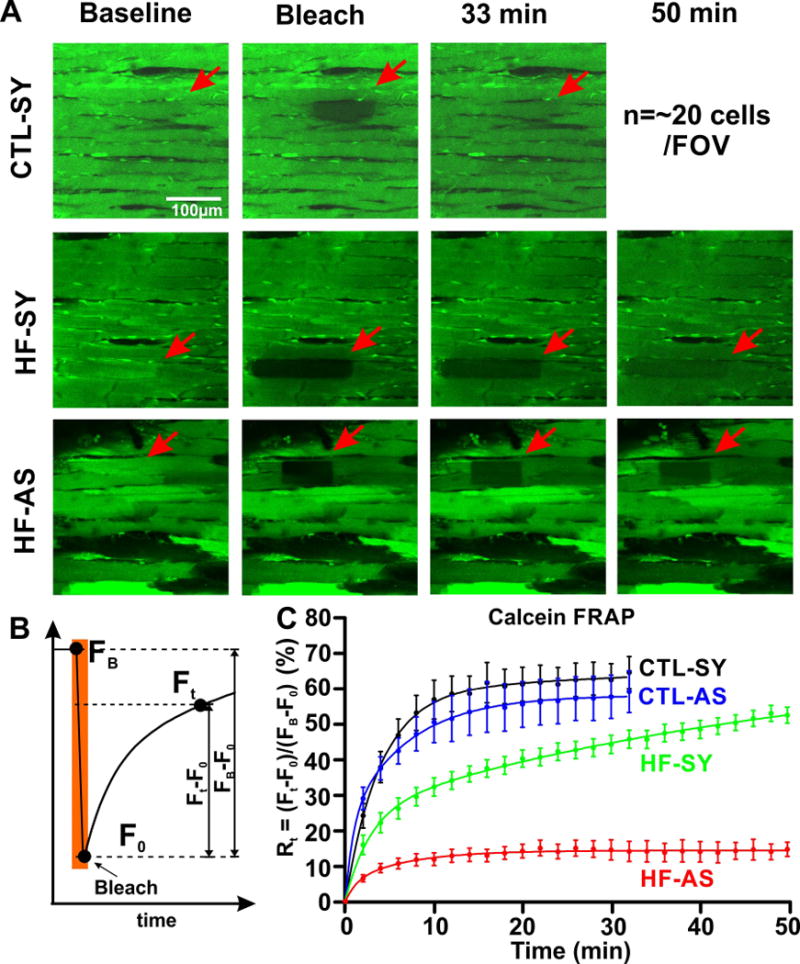

Ca asynchronous myocytes in HF hearts are poorly, but reversibly coupled via gap junctions

To directly measure gap junction coupling in identifiable asynchronous HF myocytes we measured [Ca]i and FRAP of calcein simultaneously. Figure 3A shows photobleach of a synchronous myocyte in a CTL heart (indicated by arrow in Bleach panel). In CTL hearts, calcein FRAP in synchronous myocytes recovered rapidly (halftime t½ ~3–4 min) and was complete by 30 min (CTL-SY; Figure 3A–C). This was also true for asynchronous myocytes in CTL hearts (CTL-AS). In contrast, in HF hearts, even synchronous myocytes took >45 min (HF-SY), and asynchronous HF myocytes (HF-AS) had severely limited overall FRAP (Figure 3C). The mean extent of recovery from the groups are compared in Figure 3C & 4C. Despite slower rate, HF-SY cells eventually recovered comparably to CTL hearts (CTL-SY; ns); whereas the extent of FRAP in HF-AS myocyte was much lower. This suggests that there may be gradations in coupling among myocytes in a region, with HF-AS myocytes being the most isolated.

Figure 3. Gap junction FRAP experiments in the WT and HF intact hearts.

A). Representative images of WT normal myocytes (CTL-SY) and HF normal (HF-SY) and asynchronous myocytes (HF-AS) at baseline condition, right after photo-bleaching and 33 and 50 min later. Full time course of Calcein FRAP for CTL hearts is 33 min (200 images at 10 s steps) and for HF hearts is 50 min (300 recordings at 10s steps).B). Calcein FRAP protocol indicates fluorescence prior to bleach (FB) at end of bleach (F0; bleach extent was 50-60% of FB for each case) and during recovery (Ft). C) Recovery time course Rt was calculated as (Ft-F0)/(FB –F0) for CTL-SY (n=14, black), CTL-AS (n=10, blue), HF-SY (n=8, green) and HF-AS (n=10, red) myocytes. Total recovery was only significantly different for HF-AS myocytes among the groups measured here. Overall recoveries for CTL-SY, CTL-AS and HF-SY were to 88%, 84% and 85% of FB, respectively. The incomlplete recovery is likely due in part to bleach of calcein trapped in organelles (e.g. mitochondria), which would not recover during FRAP.

Figure 4. CBX reduces cell-cell coupling in CTL hearts and ZP123 rescued weakened coupling in HF hearts.

A). Representative images of a CTL-SY myocyte, treated with CBX (CTL-SY+CBX) and a HF-AS myocyte treated with ZP123 (HF-AS+ZP123), at times indicated. B). CBX dramatically attenuated calcein FRAP recovery in CTL-SY myocytes (CTL-SY+CBX, n=8). FRAP time course for CTL-SY from Figure 3B is incuded for comparison. At right, ZP-123 enhanced calcein FRAP in both HF-SY (HF-SY+ZP123, n=7, green) and HF-AS cells (HF-AS+ZP123, n=9, red). HF-SY and HF-AS curves from Figure 3B are included for comparison. C). Total calcein FRAP recovery at steady state are shown for the groups indicated were compared (as described in text). D) Predominant time constant (τ) of FRAP for the groups shown (further analysis is in Online Figure V).

To test whether this variable coupling can be modulated acutely by reagents known to influence gap junction coupling, we also measured calcein FRAP in CTL-SY myocytes treated with the gap junction blocker CBX (25 μM).32 Figure 4A–B shows that CBX reduced FRAP dramatically in CTL-SY myocytes, reaching only the steady state level seen in HF-AS myocytes (Figure 4B–C). We also tried to promote coupling in HF hearts using rotigaptide (ZP123, 50nM), which has been reported to enhance gap junctional conductance.38,39 Figure 4A–B shows that ZP123 restored FRAP kinetics in both HF-SY and even HF-AS myocytes back to a level comparable to CTL-SY myocytes (Figure 4B–C). This suggests that the poor coupling in HF myocytes could be acutely restored, even in HF-AS myocytes.

In addition to calcein FRAP extent, we analyzed FRAP kinetics by fitting either a single or bi-exponential curve to each record (selected by unbiased goodness of fit). Online Figure VA shows the FRAP data normalized by final recovery amplitude. Most CTL heart myocytes (11 of 14) were best fit with a single exponential, but some required a second slow component (Online Figure VB). In contrast, in the 3 groups of HF hearts shown, most required a bi-exponential fit. For all bi-exponential fits (CTL and HF) the slower component τ (4–30 min) was dominant, and the fast τ (1–2 min) was a minor fraction and similar among groups; Online Figure VC–D). The dominant slow time constant was much faster for CTL myocytes (5 min) than any of the HF groups (23–29 min; Figure 4D).

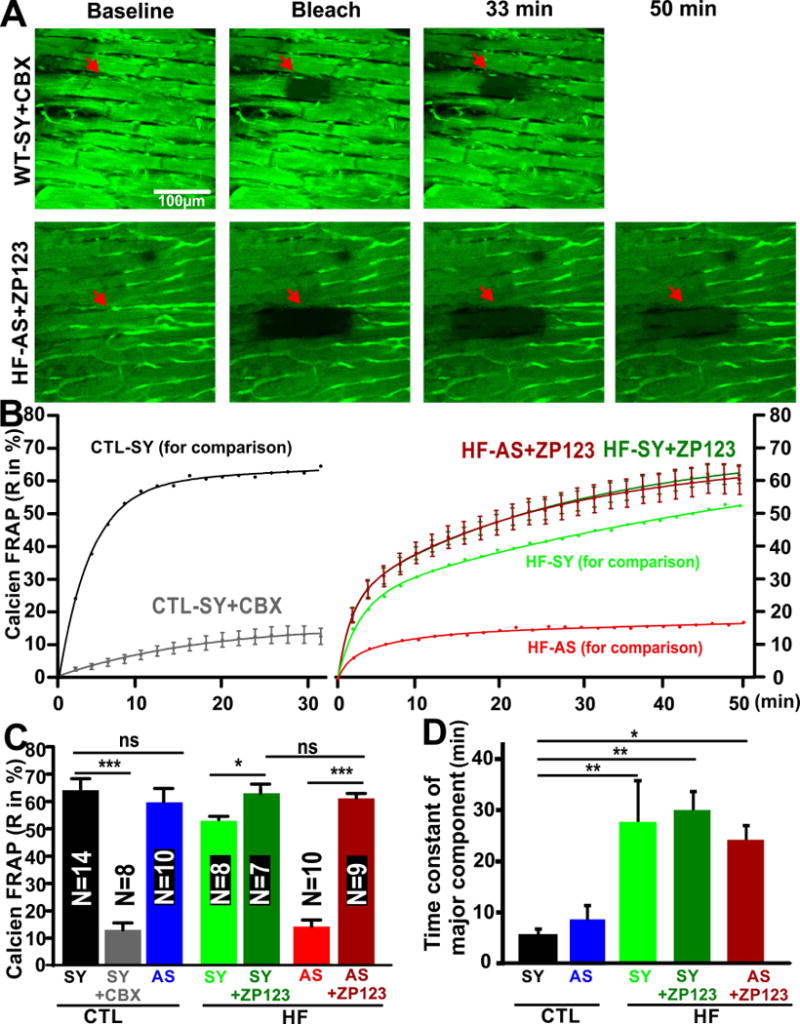

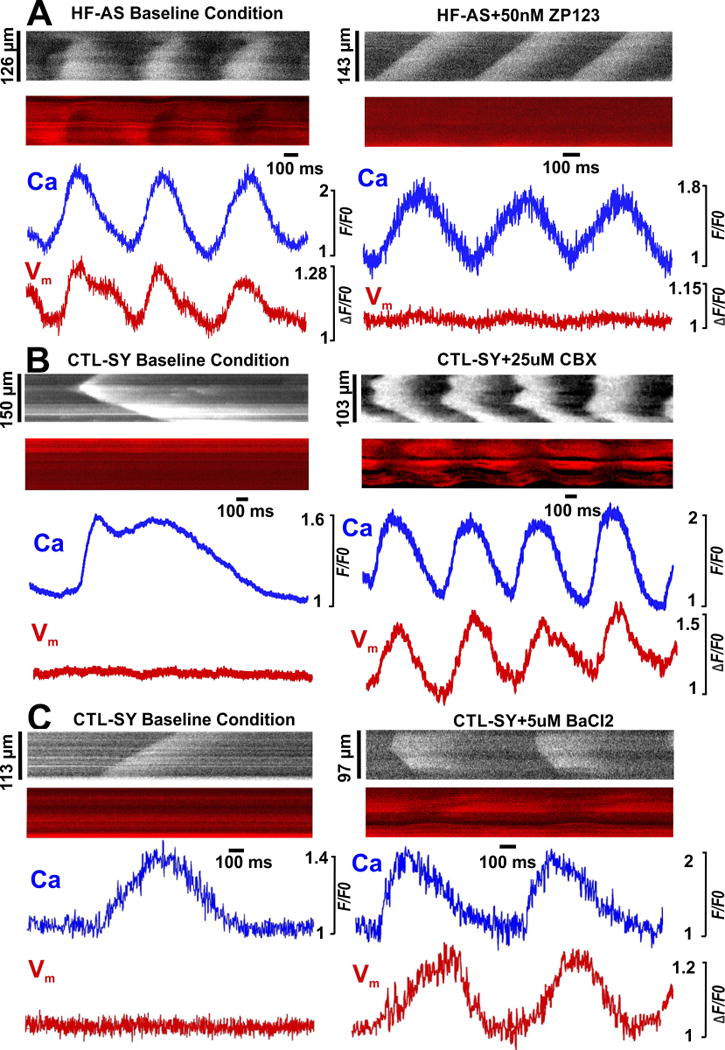

Ca-dependent depolarization is modulated by gap junction coupling and IK1.

We further tested whether the Ca wave-induced depolarizations in HF-AS myocytes (Figure 2) are sensitive to gap junction modifiers, analogous to calcein diffusion (Figure 3–4). Figure 5A shows a HF-AS myocyte that exhibited repetitive Ca waves and depolarizations, independent of surrounding myocytes. ZP123 (50 nM) did not suppress the Ca waves, but nearly abolished the associated depolarizations. Thus, restoring cell-cell coupling through gap junctions attenuated the ability of Ca waves to induce depolarization. Conversely, in a CTL myocyte exhibiting Ca waves that do not produce detectable depolarization (Figure 5B, left), partial gap junction block with 25 μM CBX allowed the Ca waves to trigger local depolarization (right). This, together with the results above indicate that reduced cell-cell coupling is a prerequisite for local Ca waves to induce significant depolarization, by limiting the current sink ordinarily created by well-coupled myocardium.

Figure 5. CBX, ZP123, and BaCl2 modulated the incidence of Ca wave induced depolarizations.

A). Representative HF-AS myocyte images showing that 50 nM ZP123 (right panel, 7/7 cells) severely diminished Ca wave-induced Vm depolarization in its absence (left panel). B). In CTL hearts, 25 μM CBX (right, 12/17 cells) induced Ca wave dependent Vm depolarization normally not seen (left). C). BaCl2 (5 μM) also promoted Ca wave dependent Vm depolarization in CTL-SY myocytes (10/12 cells) (not seen at baseline, left).

The inward rectifier potassium channel that carries IK1 is critical in stabilizing the resting membrane potential, and is likely a major contributor to the current sink effect of myocytes around a cell that exhibits a Ca wave and inward INCX. If that is the case, inhibiting IK1 should also enhance depolarizations in myocytes exhibiting Ca waves. Figure 5C shows that partial block of IK1 with 5 μM BaCl2 promoted the ability of Ca waves in CTL hearts to produce depolarization, consistent with this hypothesis.

Ca wave-induced depolarization influences adjacent asynchronous myocytes

In a few cases, we observed adjacent HF-AS myocytes in a single image. Ca waves in the two myocytes in Figure 6 seemed independent (left), but they still may interact, like in Figure 2D. We speculate that the two closely coupled beats in Cell1 may have depolarized Cell2 (which can enhance Ca loading) and facilitate the second Ca wave in Cell2. When this area was paced at 1 Hz (right panel), Cell1 followed the pacing, but the Ca transients were not spatially synchronized as in other myocytes, but rather propagated as Ca waves. This suggests that Cell 1 did not have normal AP-induced synchronized Ca transients (but Vm was not measured in this heart). Cell2 was similar, except that the slow [Ca]i decline at the first beat may have been responsible for the very limited Ca transients at the second beat. So these myocytes seem only weakly coupled to their surrounding myocardium.

Figure 6. Synchronized initiation of Ca waves under pacing in HF-AS myocytes.

Line scan images and integrated signals show Ca wave initiation in two adjacent asynchronous myocytes in an intact HF heart. At baseline, random Ca waves were observed from both myocytes, while under pacing, the Ca waves initiated synchronously from the two adjacent myocytes, as indicated by the dashed lines.

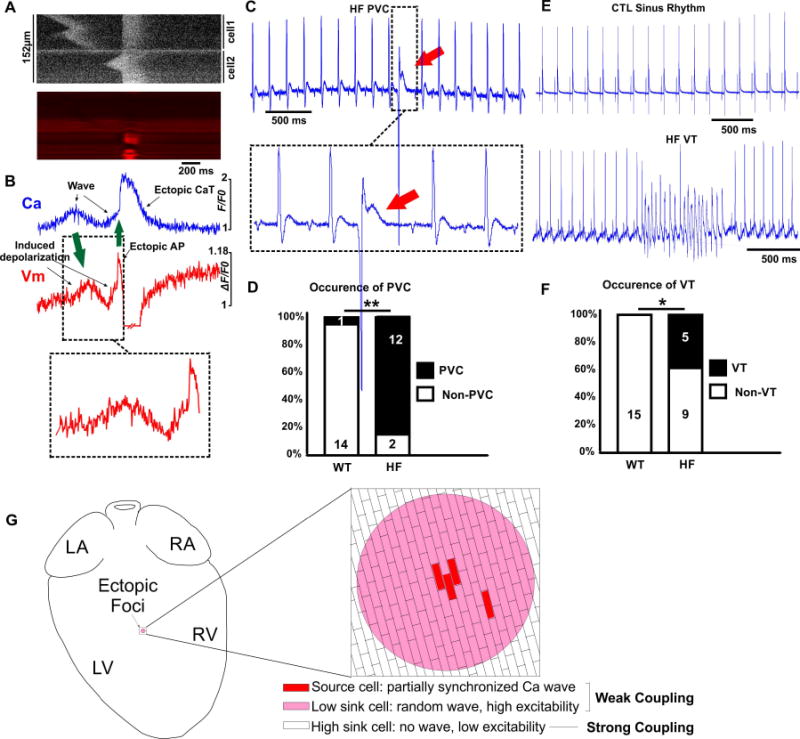

Premature ventricular contraction (PVC) initiated from Ca waves in HF hearts

A pair of adjacent HF-AS myocytes in Figure 7A showed Ca waves, where the second wave (in lower cell) triggers an AP that causes synchronous SR Ca release throughout both in that myocyte and the adjacent myocyte. This is more like what happens with robust Ca release in isolated myocytes, where the current sink that is present in the intact heart is not present (Online Figure IV right panel). The Vm trace (Figure 7B bottom part) has a motion artifact, right after the AP peak, at the Ca transient peak (likely due to insufficiently blocked contraction). Vm traces are more prone to these artifacts vs. [Ca2+]i because RH237 is restricted to the membranes. Vm depolarization can still be appreciated from the top part of cell which was less affected by contraction.

Figure 7. Ca wave-dependent extrasystoles, PVCs and ventricular tachycardia in HF hearts.

A). Line scan of a Ca wave induced extrasystole in two adjacent HF-AS myoyctes in an intact HF heart ([Ca]i top, Vm bottom). Spontaneous Ca wave in top myocyte induced deoplarization which was not sufficient to reach AP threshold, whereas the Ca wave in the bottom myoycte depolarized Vm to AP threshold, resulting in an extrasystole. B). Integrated signals from Ca and Vm channels in A). First green arrow indicates Ca wave and its subsequent depolarization. Second green arrow indicates an extrasystole with full AP induced after the second depolarizing Ca wave. At the time of the AP, a artifactual increase of the RH237 fluorescence (downward Vm deflection) due to contraction. C). Representive PVC detected in the ECG from a HF heart. D). PVC, with incidence in CTL (rare) and HF hearts (most hearts). E). Representive example of a run of VT detected in the ECG from a HF heart. F). VT was never seen in CTL hearts but evident in several HF hearts (HF). G). Mechanism schematic for ectopic foci vulneralbe island resulted from HF-AS mycoytes in HF hearts. A few AS cells with simultaneous Ca waves provide a current source sufficient to depolarize surrounding cells, which are also susceptible to asynchronous Ca activities. These surrounding cells would be somewhat depolarized and also more excitable, because lower gap junctional conductance, creating a larger arrhythmogenic current source. Reduced conductance also lowers the effective current sink that protects the normal heart from such focal arrhythmias.

If these events at the local level of 10–20 myocytes can impact overall cardiac rhythm, we might expect more arrhythmic events in HF hearts. Electrical noise prevented simultaneous ECGs during dual confocal imaging, so we could not directly test whether events we happen to capture in small fields of ~20 myocyte (Figure 7A–B) directly caused PVCs. However, we did see increased incidence of PVCs in HF vs. CTL hearts in ECG recordings before switching on confocal recording (12/14 HF hearts vs. 1/15 CTL hearts; p<0.01; Figure 7C and D). Runs of ventricular tachycardia (VT) were also detected in HF hearts, but not in the CTL hearts (Figure 7E and F). Thus, these HF hearts have greater vulnerability to PVCs and VT.

Computational modeling

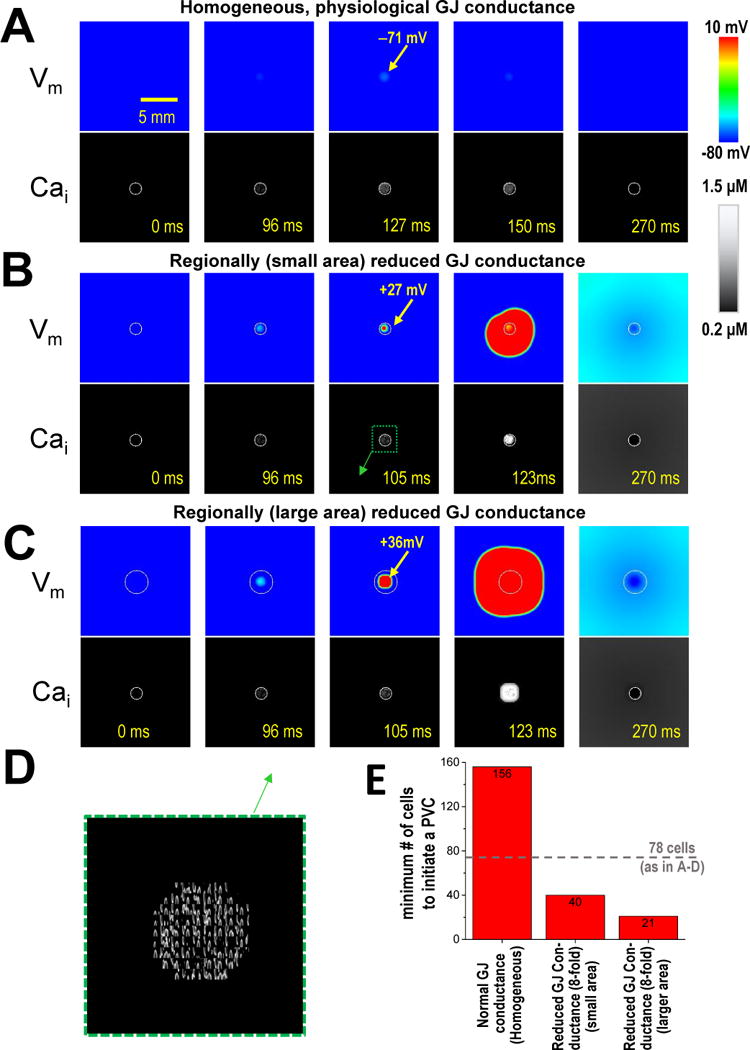

A working mechanistic hypothesis that emerges from these novel results is depicted in Figure 7G. In HF, there is a relatively high proportion of AS or rogue myocytes (10.8%) that can produce a local SR Ca release-dependent depolarization that can spread locally via reduced (but viable) cell-cell coupling. Furthermore, these local regions (pink) may be poorly coupled to the whole heart, and that could allow these foci to generate sufficient magnitude of current source to overcome the myocardial current sink that would prevent this type of triggered activity in well-coupled normal hearts. To test whether a mechanism like this is plausible, we used computational simulations that are founded in detailed cellular and tissue properties.41–43

Figure 8A shows 2-dimensional [Ca]i-Vm simulations of 10,000 physiologically coupled myocytes, where 78 myocytes at the center are Ca-loaded, with intra-SR [Ca] sufficiently high to drive spontaneous Ca waves (due to the stochastic properties of 20,000 independent release channel clusters; white circle in [Ca]i images). At 127 ms overlapping Ca waves cause a small local depolarization from –80 to –71 mV, but this transient depolarization does not propagate. When we now reduce gap junctional coupling in this small group of myocytes by 8-fold (based on the ~6-fold reduction in FRAP kinetics in HF-SY, and much more dramatic FRAP reduction in HF-AS [Figure 3–4]) a full-blown propagating AP occurs (Figure 8B). The local depolarization is larger and occurs earlier (see 96 ms) and by 105 ms a propagating AP (Vm=+27 mV) is induced. If we broaden the region of reduced conductance (white circle in Vm images in Figure 8C), while keeping the same 78 Ca-loaded myocytes as above, the AP starts sooner (see 105 ms). Notably, the number of myocytes needed to initiate a tissue PVC is smallest (21) for panel C (Figure 8E), and only half as many as in panel B. While additional in-depth simulations could further clarify conditions most conducive, these demonstrate the plausibility of this local triggering mechanism.

Figure 8. Mathematical modeling of PVCs due to regionally low GJ conductance.

A). Homogeneously normal GJ conductance (top Vm, bottom [Ca]i). The 78 myocytes within the circle in [Ca]i image (1.5 mm diameter) are Ca-loaded (and therefore spontaneously active). B). GJ conductance within this white circle is 8-fold lower than normal. C). Area of low GJ conductance is extended beyond the 78 rogue myocytes to twice that area. D). Zoomed region from pane B, showing oscillatory Ca waves. E). The minimum number of myocyte required to initiate a PVC under each condition. Number of spontaneous myocytes used in A-C (78) is indcated by dashed line.

DISCUSSION

Extrasystoles, DADs, triggered activity, and PVCs are important causes of fatal ventricular arrhythmias, including in HF patients.3,44–46 However, many aspects of the underlying mechanisms are not well understood in quantitative mechanistic detail.

Poorly coupled and asynchronous myocytes in CTL and HF hearts

We show here that in normal hearts a tiny fraction of ventricular myocytes (1.4%) are Ca-asynchronous (AS), but that this is much higher in HF (to 10.8%). Since our confocal view includes 10–20 myocytes, many CTL fields showed no AS myocytes, but HF fields typically showed one or more AS myocytes. Confocal microscopy allowed detection at this spatial scale, which is not possible with the usual whole-heart optical mapping approach.

This novel observation has several functional consequences. First, it disturbs local propagation pathways (both intracellular and extracellular) for the normally propagating AP depolarization and repolarization wavefronts. Second, the higher density of such myocytes in HF increases the probability of functional islands involving numerous cells (and consequent tortuosity) that could further perturb conduction in HF, independent of gap junction coupling or interstitial fibrosis in synchronous regions. Third, the incomplete nature of the uncoupling (as shown here) means that the poorly coupled AS myocytes can (and do) interact with the well-coupled tissue in their region. As current sinks, these regions could further slow conduction around them. Conversely, these islands could provide sufficient current source strength to cause PVCs, in a manner analogous to the normal pacemaker situation in the sino-atrial node (Figures 7G and 8). That is, a group of partially uncoupled asynchronous myocytes could be sufficiently isolated to create sufficient source current (as a triggering island) to overcome the source-sink mismatch that normally prevents single myocytes from triggering a propagating depolarization.1 Thus, the observed Ca waves in these AS regions may have a small but finite potential to drive PVCs, especially in HF where more myocytes have the gross phenotype and may also be surrounded by relatively weak coupling. Fourth, the penetrance of local Ca wave-induced depolarizations to initiate PVCs would be aided by relative synchronization among these partially isolated islands, for which we find evidence (Figures 2D and 6).

Isolated myocytes vs. whole heart

In isolated myocytes, Ca-waves and more controlled SR Ca release events produce a robust inward current that is carried almost exclusively by INCX, and which can bring Vm to threshold to trigger a full-blown AP.11,12,15,47 In HF, Na+/Ca2+ exchange is increased and IK1 is reduced, such that a smaller Ca release is sufficient to trigger an AP (more inward current and less stabilizing outward IK1).11,18,23 Indeed, the quantitative connection between myocyte SR Ca release, DADs and triggered APs is well understood. However, SR Ca release in a single well-coupled myocyte in the heart is not expected to cause appreciable depolarization because of the huge current sink provided by all of the myocytes to which it is electrically well-coupled via gap junctions. Theoretical calculations support this notion and allowed inference of the number of local myocytes that would be required to have synchronous SR Ca release events to cause a PVC.1

In support of this idea, in CTL-AS myocytes we did not detect depolarization during the Ca wave, which agrees with prior confocal whole heart Vm imaging.30 So in normal hearts, coupling is sufficiently robust to essentially voltage-clamp a single cell exhibiting a Ca wave, thus protecting the heart from this PVC mechanism. However, a key and remarkable finding here was that most HF-AS Ca waves caused measurable depolarization in the actual myocyte exhibiting the Ca wave, and further, that this local depolarization could even depolarize nearby neighboring myocytes appreciably (e.g. Figure 2). The higher INCX and lower IK1 in HF would enhance the intrinsic depolarizing strength of a given Ca wave.11 In addition, our calcein FRAP studies also show that cell-cell coupling is reduced in HF hearts (even HF-SY), consistent with the reduced Cx43 expression, lateralization and altered phosphorylation reported in HF.19–22,48 The reduced coupling is especially profound where HF-AS sites are observed (Figure 3–4). But importantly, these HF-AS myocytes are not totally uncoupled (such that they would do no active harm). In fact, ZP123 can acutely restore coupling in those regions (Figure 4) and suppress local depolarization (Figure 5A), suggesting that function (vs. expression) of gap junctions may be critical. This scenario, where combined increase of INCX, reduction of IK1 and regional reduction of gap junction conductance, promote Ca-dependent triggered activity in HF hearts agrees with both theoretical predictions1 (and Figure 8) and experimental observations.24,25 Moreover, the INCX increase would increase the current source, while reduced IK1 and gap junction conductance would limit the current sink to promote arrhythmic activity. The extent and location of reduced coupling might also enhance the source strength by functionally enlarging the volume of cells that contribute to the source. Our data here may help to further constrain theoretical models to strengthen the depth of our understanding of these events.

Synchronization of spontaneous Ca waves among myocytes also helps to achieve sufficient source current in vulnerable islands. There are likely two intrinsic factors that promote such local synchrony. First, synchrony is aided by electrotonic coupling, where the electrical coupling seen in Figure 2D can also enhance synchrony of Ca waves.49,50 Second, there is a characteristic RyR restitution time in myocytes and hearts that synchronizes Ca wave timing after a prior beat.33,51,52 The increased RyR sensitivity and leakiness in HF8 may also increase the likelihood and amplitude of the Ca waves in HF-AS myocytes. These factors enhance the arrhythmogenic strength of areas around HF-AS myocytes.

Consequences and range of varied cell-cell coupling

The FRAP time constants among synchronous regions were 7.5 times longer in HF-SY vs. CTL-SY (Figure 4D). This suggests a large reduction in gap junction conductance with maintained local synchronization, and is consistent with a large gap junction safety margin for normal propagation. Even asynchronous myocytes in CTL hearts (CTL-AS) which were rare, were well-coupled, such that no depolarization was apparent in those cells. So, Ca waves in control hearts are unlikely to be consequential. In contrast, most HF-AS myocytes were very poorly coupled, even compared to HF-SY (Figure 3C) such that an even slower time constant for more complete FRAP was unresolved. However, these HF-AS cells are electrically coupled locally (Figure 2 and 6) and the regional severity of uncoupling may be the basis of the arrhythmogenic vulnerable islands discussed above and exemplified in Figure 7G and 8). Thus, the extent of local uncoupling required to create these dangerous loci may be extreme vs. that in CTL hearts or even in most of the HF heart. And many of these potential foci may occur around the heart, based on how common these are in random regions of 15–20 epicardial myocytes sampled by our method.

The severity of uncoupling in HF-AS myocytes might eventually transition into complete uncoupling, and lose influence on neighboring cells. But as we showed, ZP123 can improve the coupling of the HF-AS cells (Figure 4) and allow them to be once again voltage-clamped by neighboring cells (Figure 5A). This also suggests that the gap junctions are recoverable, and that the cells are still physically able and have enough Cx43 available to couple better. We cannot determine from these experiments whether this involves altered post-translational modifications or subcellular localization of Cx43.

Conceivably, eventual shut down of these low-conductance junctions involves the steep Vm-dependence of gap junctional conductance (reduced at high ΔVm between cells),53 activation of ATP-sensitive K+ current (IK(ATP)) and elevated [Ca2+]i.54 That is, the higher resistance of the junction may favor a larger transcellular ΔVm gradient, which would further reduce conductance. And if the [ATP]/[ADP] ratio falls sufficiently to open IK(ATP) channels these HF-AS cells could be clamped near EK, thereby further increasing transcellular ΔVm gradient and junctional resistance. Elevated [Ca2+]i can decrease the gap junctional conductance in ventricular myocytes.55 This regulation takes time, so Ca waves per se might not cause this, but Ca loading (in the sick cell context) could hasten electrical isolation as well.

In conclusion, in HF we find a much higher density of Ca asynchronous myocytes that are poorly coupled electrically to the surrounding myocardium. These HF-AS myocytes may contribute to small islands that could initiate triggered beats, overcoming the normal source-sink current mismatch that provides a safety margin in normal hearts.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Triggered arrhythmias in disease are associated with intercellular uncoupling and myocyte sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ mishandling.

Spontaneous SR Ca2+ release can trigger depolarization and action potentials in isolated myocytes, but strong electrical coupling limits this in intact hearts.

How spontaneous SR Ca2+ release facilitates triggered activity in diseased intact hearts is not well understood.

What New Information Does this Article Contribute?

Using confocal imaging of subcellular [Ca2+]i and voltage, we observed ~1% of myocytes in intact heart exhibit spontaneous SR Ca release and fail to synchronize with the bulk ventricle.

In heart failure (HF), these asynchronous rogue myocytes are ~10-fold more prevalent and Ca2+ waves cause local depolarizations in intact hearts, implying poor electrical coupling.

Direct measurements of gap junction coupling by fluorescence recovery after photobleach (FRAP of calcein) demonstrated very poor coupling of these rogue HF myocytes (vs. those in normal hearts).

In HF these poorly coupled myocytes allow local Ca2+ release-induced depolarization to depolarize neighboring myocytes.

The combination of spontaneous Ca2+ releases and reduced local coupling may form local island of cells (a current source) which can propagate to produce focal activity (driving the sink) to promote arrhythmias.

A novel mechanism is introduced (validated by computational modeling), by which a modest number of rogue myocytes in local poorly-coupled ventricular regions may overcome the traditional source-sink mismatch that protects healthy hearts.

In HF, triggered ventricular arrhythmias are often associated with Ca2+ mishandling and gap junction uncoupling. In normal hearts, individual myocytes are extremely well-coupled to their neighbors. Thus, a spontaneous diastolic SR Ca2+ release that can depolarize an isolated single myocyte (even causing an action potential) is prevented via effective voltage clamp by the rest of the heart. This coupling protects the normal heart from this delayed afterdepolarization triggered arrhythmia mechanism. In contrast, in HF we show that spontaneous SR Ca2+ release in single rogue myocytes can depolarize themselves (indicating that they are poorly coupled to their neighbors). But they also depolarize their neighbors, despite that weak coupling. The latter implies that the neighbors are also poorly coupled to the rest of the heart, creating a potential perfect storm for triggered arrhythmias. That is, a small region can generate sufficient source current (not dissipated because of relative isolation from the whole heart) that it can drive a triggered event that can escape and propagate to the whole heart (as a premature ventricular contraction). This pathological situation is analogous to how spontaneous pacemaking cells in the sinoatrial node (a small, poorly coupled region) can activate the entire heart during the normal heartbeat.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (NIH) P01-HL080101 R01-HL105242 and R01-HL30077 (DM Bers), R01-HL111600 (CM Ripplinger) and R00-HL111334 (D. Sato).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- HF

heart failure

- CTL

control

- AP

action potential

- CaT

calcium transient

- CBX

carbenoxolone

- PVC

premature ventricular contraction

- Vm

membrane potential

- TAC

transverse aortic constriction

- NCX

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger

- FRAP

fluorescence recovery after photo-bleaching

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

References

- 1.Xie Y, Sato D, Garfinkel A, Qu Z, Weiss JN. So little source, so much sink: Requirements for afterdepolarizations to propagate in tissue. Biophys J. 2010;99:1408–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilmour RF, Jr, Moise NS. Triggered activity as a mechanism for inherited ventricular arrhythmias in german shepherd dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1526–1533. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang D, Holzem K, Kang C, Xiao M, Hwang HJ, Ewald GA, Yamada KA, Efimov IR. Arrhythmogenic remodeling of beta2 versus beta1 adrenergic signaling in the human failing heart. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:409–419. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wehrens XH, Lehnart SE, Marks AR. Intracellular calcium release and cardiac disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:69–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.114521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pogwizd SM, Bers DM. Cellular basis of triggered arrhythmias in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez AM, Valdivia HH, Cheng H, Lederer MR, Santana LF, Cannell MB, McCune SA, Altschuld RA, Lederer WJ. Defective excitation-contraction coupling in experimental cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Science. 1997;276:800–806. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gwathmey JK, Copelas L, MacKinnon R, Schoen FJ, Feldman MD, Grossman W, Morgan JP. Abnormal intracellular calcium handling in myocardium from patients with end-stage heart failure. Circ Res. 1987;61:70–76. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ai X, Curran JW, Shannon TR, Bers DM, Pogwizd SM. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ Res. 2005;97:1314–1322. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000194329.41863.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berlin JR, Cannell MB, Lederer WJ. Cellular origins of the transient inward current in cardiac myocytes. Role of fluctuations and waves of elevated intracellular calcium. Circ Res. 1989;65:115–126. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyden PA, Pu J, Pinto J, Keurs HE. Ca2+ transients and Ca2+ waves in purkinje cells : Role in action potential initiation. Circ Res. 2000;86:448–455. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.4.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: Roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res. 2001;88:1159–1167. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ter Keurs HE, Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:457–506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng H, Lederer MR, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks and [Ca2+]i waves in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C148–159. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.1.C148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curran J, Brown KH, Santiago DJ, Pogwizd S, Bers DM, Shannon TR. Spontaneous ca waves in ventricular myocytes from failing hearts depend on Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlotthauer K, Bers DM. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release causes myocyte depolarization. Underlying mechanism and threshold for triggered action potentials. Circ Res. 2000;87:774–780. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagy ZA, Virag L, Toth A, Biliczki P, Acsai K, Banyasz T, Nanasi P, Papp JG, Varro A. Selective inhibition of sodium-calcium exchanger by SEA-0400 decreases early and delayed after depolarization in canine heart. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:827–831. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armoundas AA, Hobai IA, Tomaselli GF, Winslow RL, O’Rourke B. Role of sodium-calcium exchanger in modulating the action potential of ventricular myocytes from normal and failing hearts. Circ Res. 2003;93:46–53. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000080932.98903.D8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beuckelmann DJ, Nabauer M, Erdmann E. Alterations of K+ currents in isolated human ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. Circ Res. 1993;73:379–385. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupont E, Matsushita T, Kaba RA, Vozzi C, Coppen SR, Khan N, Kaprielian R, Yacoub MH, Severs NJ. Altered connexin expression in human congestive heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:359–371. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glukhov AV, Fedorov VV, Kalish PW, Ravikumar VK, Lou Q, Janks D, Schuessler RB, Moazami N, Efimov IR. Conduction remodeling in human end-stage nonischemic left ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2012;125:1835–1847. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jongsma HJ, Wilders R. Gap junctions in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2000;86:1193–1197. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.12.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kostin S, Rieger M, Dammer S, Hein S, Richter M, Klovekorn WP, Bauer EP, Schaper J. Gap junction remodeling and altered connexin43 expression in the failing human heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;242:135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pogwizd SM, Qi M, Yuan W, Samarel AM, Bers DM. Upregulation of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger expression and function in an arrhythmogenic rabbit model of heart failure. Circ Res. 1999;85:1009–1019. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.11.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myles RC, Wang L, Bers DM, Ripplinger CM. Decreased inward rectifying K+ current and increased ryanodine receptor sensitivity synergistically contribute to sustained focal arrhythmia in the intact rabbit heart. J Physiol. 2015;593:1479–1493. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.279638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myles RC, Wang L, Kang C, Bers DM, Ripplinger CM. Local beta-adrenergic stimulation overcomes source-sink mismatch to generate focal arrhythmia. Circ Res. 2012;110:1454–1464. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.262345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang D, Glukhov AV, Efimova T, Efimov IR. Role of Pyk2 in cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H975–983. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00241.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang D, Petrov V, Lou Q, Osipov G, Efimov IR. Spatiotemporal control of heart rate in a rabbit heart. J Electrocardiol. 2011;44:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lang D, Sulkin M, Lou Q, Efimov IR. Optical mapping of action potentials and calcium transients in the mouse heart. J Vis Exp. 2011 doi: 10.3791/3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aistrup GL, Kelly JE, Kapur S, Kowalczyk M, Sysman-Wolpin I, Kadish AH, Wasserstrom JA. Pacing-induced heterogeneities in intracellular Ca2+ signaling, cardiac alternans, and ventricular arrhythmias in intact rat heart. Circ Res. 2006;99:e65–73. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000244087.36230.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujiwara K, Tanaka H, Mani H, Nakagami T, Takamatsu T. Burst emergence of intracellular Ca2+ waves evokes arrhythmogenic oscillatory depolarization via the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger: Simultaneous confocal recording of membrane potential and intracellular Ca2+ in the heart. Circ Res. 2008;103:509–518. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen B, Guo A, Gao Z, Wei S, Xie YP, Chen SR, Anderson ME, Song LS. In situ confocal imaging in intact heart reveals stress-induced Ca2+ release variability in a murine catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia model of type 2 ryanodine receptor(r4496c+/-) mutation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:841–849. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.969733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammer KP, Ljubojevic S, Ripplinger CM, Pieske BM, Bers DM. Cardiac myocyte alternans in intact heart: Influence of cell-cell coupling and beta-adrenergic stimulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;84:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wasserstrom JA, Shiferaw Y, Chen W, Ramakrishna S, Patel H, Kelly JE, O’Toole MJ, Pappas A, Chirayil N, Bassi N, Akintilo L, Wu M, Arora R, Aistrup GL. Variability in timing of spontaneous calcium release in the intact rat heart is determined by the time course of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium load. Circ Res. 2010;107:1117–1126. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.229294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang T, Maier LS, Dalton ND, Miyamoto S, Ross J, Jr, Bers DM, Brown JH. The deltac isoform of CaMKII is activated in cardiac hypertrophy and induces dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Circ Res. 2003;92:912–919. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069686.31472.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neijssen J, Herberts C, Drijfhout JW, Reits E, Janssen L, Neefjes J. Cross-presentation by intercellular peptide transfer through gap junctions. Nature. 2005;434:83–88. doi: 10.1038/nature03290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abbaci M, Barberi-Heyob M, Stines JR, Blondel W, Dumas D, Guillemin F, Didelon J. Gap junctional intercellular communication capacity by gap-frap technique: A comparative study. Biotechnol J. 2007;2:50–61. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bers DM, Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K. Upregulated Na/Ca exchange is involved in both contractile dysfunction and arrhythmogenesis in heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol. 2002;97(Suppl 1):I36–42. doi: 10.1007/s003950200027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xing D, Kjolbye AL, Nielsen MS, Petersen JS, Harlow KW, Holstein-Rathlou NH, Martins JB. Zp123 increases gap junctional conductance and prevents reentrant ventricular tachycardia during myocardial ischemia in open chest dogs. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:510–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hennan JK, Swillo RE, Morgan GA, Keith JC, Jr, Schaub RG, Smith RP, Feldman HS, Haugan K, Kantrowitz J, Wang PJ, Abu-Qare A, Butera J, Larsen BD, Crandall DL. Rotigaptide (zp123) prevents spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias and reduces infarct size during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in open-chest dogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:236–243. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.096933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pereira L, Cheng H, Lao DH, Na L, van Oort RJ, Brown JH, Wehrens XH, Chen J, Bers DM. Epac2 mediates cardiac beta1-adrenergic-dependent sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak and arrhythmia. Circulation. 2013;127:913–922. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.12.148619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shannon TR, Wang F, Puglisi J, Weber C, Bers DM. A mathematical treatment of integrated ca dynamics within the ventricular myocyte. Biophys J. 2004;87:3351–3371. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahajan A, Sato D, Shiferaw Y, Baher A, Xie LH, Peralta R, Olcese R, Garfinkel A, Qu Z, Weiss JN. Modifying l-type calcium current kinetics: Consequences for cardiac excitation and arrhythmia dynamics. Biophys J. 2008;94:411–423. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.98590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sato D, Bers DM. How does stochastic ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca leak fail to initiate a Ca spark? Biophys J. 2011;101:2370–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pogwizd SM. Nonreentrant mechanisms underlying spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias in a model of nonischemic heart failure in rabbits. Circulation. 1995;92:1034–1048. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.London B, Baker LC, Lee JS, Shusterman V, Choi BR, Kubota T, McTiernan CF, Feldman AM, Salama G. Calcium-dependent arrhythmias in transgenic mice with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H431–441. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00431.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKenna WJ, England D, Doi YL, Deanfield JE, Oakley C, Goodwin JF. Arrhythmia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. I: Influence on prognosis. Br Heart J. 1981;46:168–172. doi: 10.1136/hrt.46.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stern MD, Capogrossi MC, Lakatta EG. Spontaneous calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in myocardial cells: Mechanisms and consequences. Cell Calcium. 1988;9:247–256. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(88)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ai X, Zhao W, Pogwizd SM. Connexin43 knockdown or overexpression modulates cell coupling in control and failing rabbit left ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:751–762. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sato D, Bartos DC, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. Depolarization of cardiac membrane potential synchronizes calcium sparks and waves in tissue. Biophys J. 2014;107:1313–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sato D, Xie LH, Sovari AA, Tran DX, Morita N, Xie F, Karagueuzian H, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN, Qu Z. Synchronization of chaotic early afterdepolarizations in the genesis of cardiac arrhythmias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2983–2988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809148106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L, Myles RC, De Jesus NM, Ohlendorf AK, Bers DM, Ripplinger CM. Optical mapping of sarcoplasmic reticulum ca2+ in the intact heart: Ryanodine receptor refractoriness during alternans and fibrillation. Circ Res. 2014;114:1410–1421. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Satoh H, Blatter LA, Bers DM. Effects of [Ca2+]i, SR Ca2+ load, and rest on Ca2+ spark frequency in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H657–668. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Revilla A, Bennett MV, Barrio LC. Molecular determinants of membrane potential dependence in vertebrate gap junction channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14760–14765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Obaid AL, Socolar SJ, Rose B. Cell-to-cell channels with two independently regulated gates in series: Analysis of junctional conductance modulation by membrane potential, calcium, and ph. J Membr Biol. 1983;73:69–89. doi: 10.1007/BF01870342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toyama J, Sugiura H, Kamiya K, Kodama I, Terasawa M, Hidaka H. Ca2+-calmodulin mediated modulation of the electrical coupling of ventricular myocytes isolated from guinea pig heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1994;26:1007–1015. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1994.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.