Abstract

Background:

Topical corticosteroids (TC) are one of the most widely used agents in dermatology practice. Misuse of these agents may lead to a wide range of adverse effects.

Aim:

This study was conducted to assess the magnitude of abuse of topical corticosteroids (TC) and clinical patterns of cutaneous adverse effects amongst patients attending dermatology department of a teaching hospital at South Rajasthan.

Materials and Methods:

All patients who reported with adverse effects of topical steroids during one year from September 2015 to August 2016 were evaluated. Patients fulfilling the study criteria were registered for further workup.

Results:

Out of the 85280 new patients, 370 (0.43%) presented with adverse effects of TC. Males (232/370;62.70%) outnumbered females (138/370;37.30). Age group 11-30 years was most commonly (74.05%) affected. The main reason for using TC was fungal infection (52.43%). Tinea incognito (49.46%) and acne (30.27%) were the most common adverse effects recorded.

Conclusions:

Abuse of TC, particularly the superpotent and potent is rampant amongst general population. Topical corticosteroids are frequently used for indications where they should be avoided.

Keywords: Corticosteroid abuse, tinea incognito, topical corticosteroids, topical steroid-dependent facies

What was known?

Topical corticosteroids (TC) are commonly used agents in dermatology practice. They are generally thought to be panacea for all skin ailments by non-dermatologists and lay public alike and are frequently abused as fairness creams and can lead to plethora of cutaneous as well as systemic adverse effects.

Introduction

Topical corticosteroids (TCs) are one of the most widely used agents in dermatologic practice. Sulzberger and Witten in 1952 published the first report of the utility of Compound F (hydrocortisone) in dermatology.[1] Subsequently, a large number of the molecules have been introduced after modifications of the original Compound F. Based on their vasoconstrictive properties, they have been variously classified.[2,3] The clinical effects of TCs are mediated by their anti-inflammatory, vasoconstrictive, antiproliferative, and immunosuppressive properties.[4,5] Apart from the well-known indications such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and vitiligo, they are used for many other dermatoses and sometimes even undiagnosed skin rash by dermatologists and general physicians.[6]

Poor health infrastructure, lack of adequate specialist services, practice of self-medication, affordability, and easy access over the counter (OTC) has resulted in widespread abuse of TC. The problem of side effects has, however, become a huge concern due to rampant and widespread misuse of TC, particularly by nondermatologists.[7] There have only been a few studies[8,9,10] on abuse of TC from Indian subcontinent and Rajasthan. This study was conducted to assess the magnitude abuse of TC, its reasons, and the common sequelae resulting from it.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional observational study was carried out to assess all the cases, with cutaneous adverse effects of TC attending the dermatology outpatient department of a teaching hospital of South Rajasthan between September 2015 and August 2016.

The patients who applied TC for various conditions and overused TC beyond the time limit prescribed by a physician or applied superpotent or potent steroid on the face, genitalia, axilla, or groin and presented with one or more side effects of these agents as the chief complaint were included. Patients who had cutaneous adverse effects suggestive of TC without details of agents were excluded.

Patients fulfilling the study criteria were registered for further workup as per the pro forma. The type, potency, frequency of application, duration of therapy, reason, and source of information for its use were recorded. Photographic documentation of the patients was done.

Results

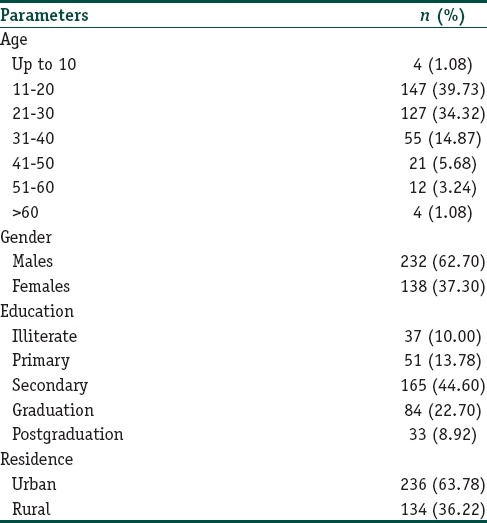

Of 85,280 patients, 370 (0.43%) patients were recorded with adverse effects of TC. The age of patients ranged between 2 years and 78 years; mean age was 28 years. Most common (274/370; 74.05%) age group affected was 11–30 years. There were 232 (62.70%) males and 132 (37.30%) females; male:female ratio was 1.68:1. Ninety percent patients were literate; majority (165/370; 44.60%) of patients had secondary school education. Urban patients (236/370; 63.78%) outnumbered rural (134/370; 36.22%) patients [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic details of patients presenting with adverse effects of topical corticosteroids (n=370)

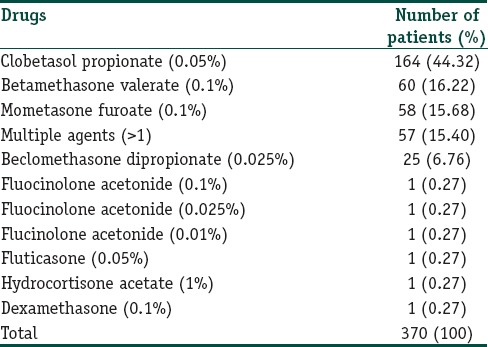

More than 80 brands [Figure 1a–c] of TC were misused by patients; majority (190/370; 51.35%) of these were superpotent and potent. Clobetasol propionate 0.05% was the most common (164; 44.33%) TC misused followed by betamethasone valerate 0.1% (60; 16.22%) and mometasone furoate 0.1% (58; 15.68%). Multiple TC was abused by 57 (15.40%) patients [Table 2].

Figure 1.

(a-c) Various topical corticosteroids abused by the patients

Table 2.

Topical steroid formulations misused

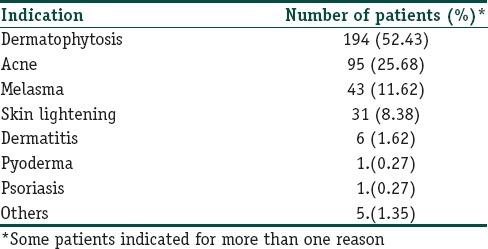

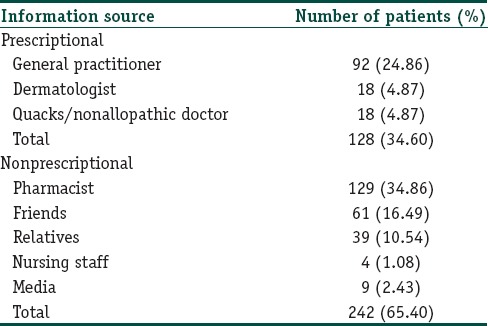

More than half of the patients used TC for treatment of fungal infection (194/370; 52.43%) followed by acne (95/370; 25.68%), melasma (43/370; 11.62%), and skin lightening (31/370; 8.38%) [Table 3]. A large number of patients (242/370; 65.40%) obtained TC without prescription while only 128 (34.60%) patients purchased TC on prescription. Only 4.87% patients were prescribed TC by a dermatologist [Table 4]. Majority of patients applied TC for 1 week to 1 month (181/370; 48.91%) duration. This was followed by 1 month − 3 months (78/370; 21.08%), <1 week (55/370; 14.86%), 3–6 months (25/370; 6.75%), and 6 months–1 year (20/370; 5.40%) duration. Ninety-five percent patients (353) applied TC twice or more per day, and majority (364; 98.37%) of patients were unaware of adverse effects of topical steroids.

Table 3.

Indications for using the topical corticosteroid formulation by the patients

Table 4.

Source of information for topical corticosteroids use

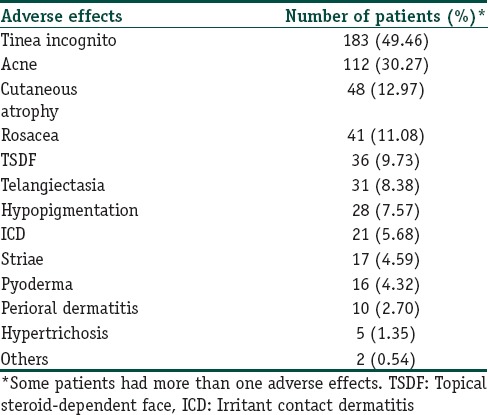

Tinea incognito was the most common adverse effect (183/370; 49.46%) recorded in the study. This was followed by acne (112/370; 30.27%), cutaneous atrophy (48/370; 12.97%), rosacea (41/370; 11.08%), topical steroid-dependent facies (TSDFs) (36/370; 9.73%), telangiectasia (31/370; 8.38%), hypopigmentation (28/370; 7.57%), irritant contact dermatitis (21/370; 5.68%), striae (17/370; 4.59%), pyoderma (16/370; 4.32%), perioral dermatitis (10/370; 2.70%), and hypertrichosis (5/370; 1.35%) [Table 5 and Figures 2–12].

Table 5.

Dermatological adverse effects of topical corticosteroids abuse

Figure 2.

(a and b) Tinea pseudoimbricata. (c and d) Tinea incognito with striae rubra

Figure 12.

Irritant contact dermatitis

Figure 3.

(a) Monomorphic acne over face. (b) Monomorphic acne over chest. (c) Nodulocystic acne

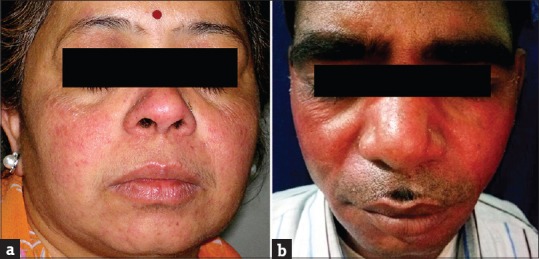

Figure 4.

(a and b) Rosacea

Figure 5.

(a and b) Topical steroid-dependent facies

Figure 6.

(a and b) Telangiectasia

Figure 7.

(a and b) Perioral dermatitis

Figure 8.

Cutaneous atrophy

Figure 9.

(a and b) Hypopigmentation

Figure 10.

Hypertrichosis

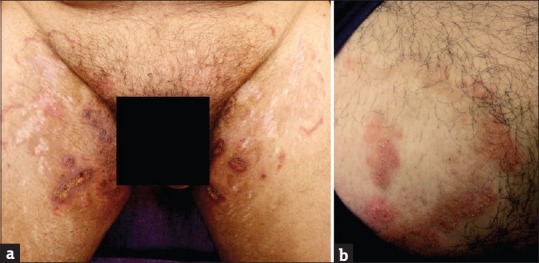

Figure 11.

(a and b) Pyoderma with modified tinea

Discussion

This questionnaire-based observational study on the abuse of TC recorded a total of 370 patients with adverse effects. The hospital-based incidence of patients having adverse effects was 0.43% which is relatively low compared to other studies[8,9,10] and could possibly be because our study excluded patients who had features suggestive of steroid abuse but were not able to furnish the details of the product they had used. The data may not truly represent the real magnitude of the problem as many people who use TC may not seek consultation from a dermatologist or ignore seeking consultation for adverse effects. Males (232/370; 62.70%) outnumbered females (138/370; 37.30%), in contrast to some studies[8,9,10] in which female preponderance was seen. The most common age group affected was 11–30 years as in some other studies.[8,9,10] This is quite expected as this age group is very conscious of their looks and also more likely to resort to self-medication.

Majority (313/370; 84.60%) used single agent, while 15.40% (57/370) patients used more than one agent. Clobetasol propionate 0.05% was the most commonly (164/370; 44.32) abused TC This observation is similar to a study done by Al-Dhalimi and Aljawahiry[8] but in contrast to some other studies,[9,10] in which betamethasone valerate 0.1% was the main TC abused. TCs are frequently misused as fairness creams due to their potent bleaching action and as an anti-inflammatory agent in different dermatoses.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14] However, in our study, the main reason for using TC was fungal infection in 194 (52.43%) patients. The other reasons were acne 95 (25.68%), melasma 43 (11.62%), achieving fairness in 31 (8.38%) patients. Despite being Schedule H drugs, TC is readily available OTC product. In this study, majority of patients used TC on the advice of pharmacist (129; 34.83%). Only a few patients were TC advised by dermatologists (18/370; 4.87%). Similar observation has been made in other studies too.[8,9,10] This probably calls for a strict regulation regarding the sale of these products with prescription from qualified persons only. Furthermore, nondermatologist need to be educated about adverse effects of TCs as they are unaware of havoc caused by misuse of steroids used topically.

A total of 550 adverse effects were noted in 370 patients. Tinea incognito was found to be the most common adverse effect (183/370; 49.46%). In another study by Al-Dhalimi and Aljawahiry,[8] only (4/140; 2.9%) patients presented with tinea incognito while Dey[9] reported 56 (14.77%) patients with it. TCs by suppressing the normal cutaneous immune response enhance fungal infections.[15] The clinical manifestation can masquerade a number of other dermatoses. “Tinea pseudoimbricata” is a peculiar type of tinea incognito which has been recently described and was seen in 23 (12.56%) of our patients.[16]

TCs induce comedone formation by rendering follicular epithelium more responsive to comedogenesis.[17,18] Acneiform eruption was seen in 112 (30.27%) patients. These results were similar to other studies by Al-Dhalimi and Aljawahiry,[8] Dey,[9] and Rathod et al.,[10] who reported acneiform eruption in 36.4%, 37.99%, and 45.8% patients, respectively. Most common site was face 108 (96.43%), followed by trunk 3 (2.68%) and arm 1 (0.89%).

Rosacea was seen in 41 (11.08%) patients. In other studies by Hameed,[12] Jha et al.,[13] and Saraswat et al.,[14] rosacea was seen in 86.3%, 6.8%, and 7% patients, respectively. Most of these patients were females (35/41; 85.37%). All patients had erythema while telangiectasia was seen in 31 (75.61%). Twenty-seven (65.83%) patients used TC mixed with agents such as hydroquinone, tretinoin, salicylic acid, and antifungals, while 14 (34.15%) patients used TC alone. TSDF or red face syndrome is a recently described entity characterized by plethora of symptoms caused by unsupervised misuse /abuse/overuse of TC of any potency on the face over an unspecified and/or prolonged period.[19] It was seen in 36 (9.73%) patients. Most patients were females (28/36; 77.78%%). Fifteen (41.67%) patients abused TC for more 3 months. They presented with diffuse erythema, burning, scaling, and xerosis of the face that got worsened on attempting to stop the application of TC. In other studies by Hameed,[12] Jha et al.,[13] and Saraswat et al.,[14] TSDF was seen in 92.7%, 10.9%, and 8.2% patients, respectively. Perioral dermatitis was seen in 10 (2.70%) patients which is relatively less compared to other studies,[13,14] reporting it in 5.1% and 8.4% cases, respectively. The low prevalence of TSDF and perioral dermatitis could probably be due to the fact that the index study recorded the adverse effects of TC in general and was not confined to steroid abuse on face only, as in studies carried out by Hameed,[12] Jha et al.,[13] and Saraswat et al .[14]

Twenty-one (5.68%) patients had suspected irritant contact dermatitis, in accordance with some previous studies[20,21,22,23,24,25] that estimated the prevalence to be in the range of 0.2%–6%. Patients of contact dermatitis presented with acute onset itching, burning, redness, and cauterized appearance of facial skin. Out of 21 patients, 14 (66.67%) used combination product containing tretinoin, hydroquinone, and steroid. Two (9.52%) patients had used combination of salicylic acid with steroid and 5 (23.80%) patients had used steroid alone. Forty-eight (12.97%) patients had cutaneous atrophy; 21 (43.75%) of them used super/high potency TC. In a study by Dey,[9] 10.02% patients had atrophy while Al-Dhalimi and Aljawahiry[8] reported cutaneous atrophy in 17.1% patients. Pigmentary alteration, particularly hypopigmentation with steroid, is frequently reported in many studies.[8,9,10] Hypopigmentation was seen in 7.57% (28/370) patients in our study. Most common site for hypopigmentation was face in 21 (75%), groin in 5 (17.86%), and limb in 2 (7.14%) patients. Sixteen (57.14%) patients used super/high-potency TC. TC-induced hypopigmentation is hypothesized to result from impaired melanocyte function.[26]

Conclusion

The study showed that the abuse of TC, particularly the superpotent and potent, is rampant among general population, irrespective of the literacy status. People use TC for various wrong indications such as infection, infestation, acne, and also as fairness creams.

Continuous education of clinicians about potentially harmful effects of TC and reporting these adverse effects to regulatory health agencies, along with ensuring strict regulation of TCs sale OTC, mass awareness, and warning people not to fall prey to tall and spurious claims by advertising agencies are some of the important strategies to overcome the epidemic of steroid abuse.

An initiative by Indian Association of Dermatologists, Venereologists and Leprologists - Indian Task Force Against Topical Steroid Abuse is one such attempt to spread awareness on this important subject and curb this ever growing menace. Dermatologists have a huge role to play toward this challenge.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

The TC abuse is not uncommon even in males and literate masses. The tendency to use TC in dermatophytic infection is rampant leading to modification in clinical picture and therefore posing difficulty in its successful treatment. Enhanced and concerted efforts on the part of patients, prescribers, and regulatory health agencies are needed to overcome the challenge of steroid abuse.

References

- 1.Sulzberger MB, Witten VH. The effect of topically applied compound F in selected dermatoses. J Invest Dermatol. 1952;19:101–2. doi: 10.1038/jid.1952.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.69th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Pr; March 2015-September; 2015. British Medical Association, Pharmaceutical Press, Joint Formulary Committee, BMJ Group. British National Formulary. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: A quick reference guide including patch test substance and crossreactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes J, Rustin M. Corticosteroids. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:715–21. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(97)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valencia IC, Kerdel FA. Topical glucocorticoids. In: Fitzpatrick T, editor. Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. pp. 2713–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ference JD, Last AR. Choosing topical corticosteroids. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hengge UR, Ruzicka T, Schwartz RA, Cork MJ. Adverse effects of topical glucocorticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Dhalimi MA, Aljawahiry N. Misuse of topical corticosteroids: A clinical study in an Iraqi hospital. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12:847–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dey VK. Misuse of topical corticosteroids: A clinical study of adverse effects. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:436–40. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.142486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathod PR, Shankar R, Sawant A. Clinical study of topical corticosteroids misuse. Int J Recent Trends Sci Technol. 2015;15:322–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rathi S. Abuse of topical steroid as cosmetic cream: A social background of steroid dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2006;51:154–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hameed AF. Topical steroid misuse on the face: A medical and social problem in Iraq. Iraqi Postgrad Med J. 2014;13:346–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jha AK, Sinha R, Prasad S. Misuse of topical corticosteroids on the face: A cross-sectional study among dermatology outpatients. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:259–63. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.185492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saraswat A, Lahiri K, Chatterjee M, Barua S, Coondoo A, Mittal A, et al. Topical corticosteroid abuse on the face: A prospective, multicenter study of dermatology outpatients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:160–6. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.77455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verma S, Madhu R. The Great Indian epidemic of superficial dermatophytosis: An appraisal. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:227–36. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_206_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma SB. Sales, status, prescriptions and regulatory problems with topical steroids in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:201–3. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.132246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuflik JH, Schwartz RA. Acneiform eruptions. Cutis. 2000;66:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Momin S, Peterson A, Del Rosso JQ. Drug-induced acneform eruptions: Definitions and causes. Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;22:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lahiri K, Coondoo A. Topical steroid damaged/dependent face (TSDF): An entity of cutaneous pharmacodependence. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:265–72. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.182417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheuer E, Warshaw E. Allergy to corticosteroids: Update and review of epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and structural cross-reactivity. Am J Contact Dermat. 2003;14:179–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dooms-Goossens A, Morren M. Results of routine patch testing with corticosteroid series in 2073 patients. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;26:182–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1992.tb00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bircher AJ, Thürlimann W, Hunziker T, Pasche-Koo F, Hunziker N, Perrenoud D, et al. Contact hypersensitivity to corticosteroids in routine patch test patients. A multi-centre study of the Swiss Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Dermatology. 1995;191:109–14. doi: 10.1159/000246526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lutz ME, el-Azhary RA. Allergic contact dermatitis due to topical application of corticosteroids: Review and clinical implications. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:1141–4. doi: 10.4065/72.12.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Isaksson M, Andersen KE, Brandão FM, Bruynzeel DP, Bruze M, Camarasa JG, et al. Patch testing with corticosteroid mixes in Europe. A multicentre study of the EECDRG. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:27–35. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2000.042001027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomson KF, Wilkinson SM, Powell S, Beck MH. The prevalence of corticosteroid allergy in two U.K. centres: Prescribing implications. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:863–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coondoo A, Phiske M, Verma S, Lahiri K. Side-effects of topical steroids: A long overdue revisit. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:416–25. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.142483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]