Summary

Patients who have suffered severe traumatic or non-traumatic brain injuries can show a progressive recovery, transitioning through a range of clinical conditions. They may progress from coma to a vegetative state (VS) and/or a minimally conscious state (MCS). A longer duration of the VS is known to be related to a lower probability of emergence from it; furthermore, the literature seems to lack evidence of late improvements in these patients.

This real-practice prospective cohort study was conducted in inpatients in a VS following a severe brain injury, consecutively admitted to a vegetative state unit (VSU). The aim of the study was to assess their recovery in order to identify variables that might increase the probability of a VS patient transitioning to MCS.

Rehabilitation treatment included passive joint mobilisation and helping/placing patients into an upright sitting position on a tilt table. All the patients underwent a specific assessment protocol every month to identify any emergence, however late, from the VS.

Over a 4-year period, 194 patients suffering sequelae of a severe brain injury, consecutively seen, had an initial Glasgow Coma Scale score ≤ 8. Of these, 63 (32.5%) were in a VS, 84 (43.3%) in a MCS, and 47 (24.2%) in a coma; of the 63 patients admitted in a VS, 49 (57.1% males and 42.9% females, mean age 25.34 ± 19.12 years) were transferred to a specialist VSU and put on a slow-to-recover brain injury programme. Ten of these 49 patients were still in a VS after 36 months; of these 10, 3 recovered consciousness, transitioning to a MCS, 2 died, and 5 remained in a VS during the last 12 months of the observation.

Univariate analysis identified male sex, youth, a shorter time from onset of the VS, diffuse brain injury, and the presence of status epilepticus as variables increasing the likelihood of transition to a MCS.

Long-term monitoring of patients with chronic disorders of consciousness should be adequately implemented in order to optimise their access to rehabilitation services.

Keywords: brain injury, minimally conscious state, rehabilitation, vegetative state

Introduction

Patients who have suffered severe traumatic or non-traumatic brain injuries can show a progressive recovery, transitioning through a range of clinical conditions. While there may be some overlap between these conditions, their severity can vary (The Multi-Society Task Force on the Persistent Vegetative State, 1994). These different clinical stages are often described using standardised tools for the evaluation of cognitive state (Hagen et al., 1979; Giacino et al., 2004) or purely descriptive neurological criteria (Alexander et al., 1982; Povlishock and Katz, 2005).

Patients may progress from coma to a vegetative state (VS) and/or a minimally conscious state (MCS) (Bernat, 2009). While these may be temporary clinical conditions (de Jong, 2012), in some cases they are the stabilised outcome of the acute cerebral event and the patient never recovers full consciousness (Bernat, 2010).

The VS, recently termed “unresponsive wakefulness syndrome” (Laureys et al. 2010), involves a disconnection between the thalamus and cerebral cortex (Thibaut et al., 2012; Rosanova et al., 2012), secondary to a variety of acute events with different causes, but commonly resulting in diffuse axonal damage caused by traumatic brain injuries (TBI) involving shearing forces (Vuilleumier et al., 1995), hypoxic-ischaemic neuronal damage (Khot and Tirschwell, 2006), or cerebral haemorrhage (Cesarini et al., 1999) causing injury to the cortex and thalamus.

MCS differs from the VS in the presence of behaviours demonstrating conscious awareness (Giacino et al., 2002). Although these behaviours may appear inconsistently, they are repeatable and maintained for a sufficient time to enable them to be differentiated from reflexive behaviours (Giacino et al., 1997).

A growing interest in the clinical evolution of patients with consciousness disorders following severe brain injuries has probably modified epidemiological data concerning emergence from VS. It is well known that a longer duration of the VS is related to a lower probability of emergence from that state; furthermore, the literature seems to lack evidence of late improvements in these patients (Estraneo et al., 2010).

The aim of this real practice, prospective cohort study was to assess the percentage of recovery from a VS to a MCS among inpatients with severe traumatic brain injury referred to a vegetative state unit. Moreover we aimed to identify the variables that might increase the probability of transition to a MCS.

Materials and methods

Participants

We recruited inpatients in a VS after a severe brain injury consecutively admitted to the Neurorehabilitation and Vegetative State Unit (VSU) of Cuneo (Italy). All participants had a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of ≤ 8 at admission.

Outcomes

A detailed medical history was collected for all patients. During the stay in the VSU, the patients underwent a clinical examination and routine blood tests every week and, where necessary, radiological and neuroradiological investigations were carried out every month. In addition, all the patients underwent a specific assessment protocol every month to detect any emergence, however late, from the VS. At baseline we administered the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R) (Giacino et al., 2004), whose purpose is to support differential diagnosis, prognostic assessment and treatment planning in patients with consciousness disorders. It consists of 23 items divided into 6 subscales addressing auditory, visual, motor, oromotor, communication and arousal functions. The subscales consist of hierarchically-arranged items associated with brainstem, cortical and subcortical processes. The CRS-R seems to be a suitable instrument for revealing emergence from the VS and its prognostic utility has been confirmed in many studies, suggesting that is also suitable for assessing levels of consciousness and monitoring recovery of neurobehavioural function (Giacino et al., 2007; Giacino et al., 2009; American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, Brain Injury-Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group, Disorders of Consciousness Task Force, 2010).

In our cohort we recorded: 1) sex, 2) age at onset of coma, 3) time since onset of VS, 4) aetiology of coma (categorised as traumatic brain injury, anoxic encephalopathy, haemorrhagic encephalopathy), 5) CRS-R score on admission to the VSU, 6) CRS-R score 48 months after admission to the VSU, 7) duration of coma, 8) injuries revealed on neurological scanning (presence of focal injuries, cortical atrophy and/or subcortical atrophy), and 9) late onset of epileptic seizures.

The assessments were performed on admission to the VSU (T0) and, following discharge from VSU, at 12 months (T1), 24 months (T2), 36 months (T3), and 48 months (T4) from the time of admission.

Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for the univariate analysis, with F distribution for the continuous variables, while Pearson’s chi-squared test with Yates’ correction for continuity was used for categorical variables, making the test conservative, as with Fisher’s exact test. As the caseload was substantially reduced by the deaths of numerous patients, these patients were excluded from the analysis. Given these limits, the multivariate analysis was carried out only for comparison of MCS and VS.

Results

Over a 4-year period, 194 patients suffering the sequelae of a severe brain injury (initial GCS score ≤ 8) were consecutively evaluated. Of these, 63 (32.5%) were in a VS, 84 (43.3%) in a MCS, and 47 (24.2%) in a coma; of the 63 patients in a VS, 49 were then put on a specialist programme for slow-to-recover brain injury.

Of the 49 patients initially admitted to the VSU — 28 males (57.1%) and 21 females (42.9%), mean age 25.34 ± 19.12 years —, 24 had post-anoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy (49.0%), 12 a traumatic head injury (24.5%), 6 ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke (12.2%), and 5 aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (10.2%); the remaining 2 had other acute neurological conditions (4.1%).

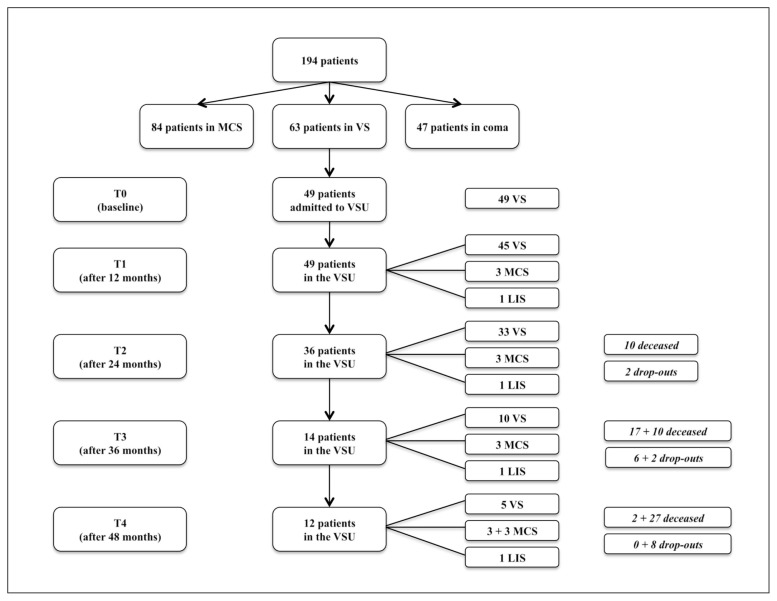

The observation period, both in the VSU and in community facilities, lasted four years. In that time, of the 49 participants, 6 transitioned to a MCS, 1 showed a locked-in syndrome, 29 died (16 from infectious diseases, 5 from neurological diseases, 3 from heart disease, and 4 from unknown causes), and there were 8 dropouts. The flow-chart of the study population (Fig. 1) provides more details. The clinical data also refer to the subsequent period in community facilities.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population.

MCS: minimally conscious state; VS: vegetative state; VSU: vegetative state unit; LIS: locked-in syndrome

Of the 10 patients in a VS at T3, 3 recovered consciousness, transitioning to a MCS, and 2 died during the last 12 months of observation, while 5 remained unconscious in a VS. The patients were in a VS for a mean of 564 days (min: 275; max: 1189).

Univariate analysis identified male sex, youth, a shorter time since onset of VS, diffuse brain injury and the presence of status epilepticus (SE) as the variables increasing the likelihood of transition to a MCS. These descriptive observations were reflected in the multivariate model. The probability of transition was around three times higher (OR 0.33) when fewer than 56 days had elapsed since the onset of VS. The global incidence of epileptic seizures was 24.49% (12 out of 49 patients); patients suffering seizures were roughly twice as likely as those without seizures to progress to a MCS, although this was not statistically significant.

Discussion

In this prospective study, 14.29% of the patients showed a recovery, transitioning from VS to MCS. Moreover, male sex, youth, a shorter time from onset of VS, diffuse brain injury and the presence of SE seemed to be the variables increasing the likelihood of this outcome. In our study, however, some of the variables potentially capable of influencing emergence (including late emergence) from VS did not differ significantly between patients who recovered and those who did not recover responsiveness.

The duration of VS at the time of admission to the VSU, the cause of the brain injury, the time between the acute event and start of neurorehabilitation, and the CRS-R score on admission to the VSU were all found to have no effect. Patients suffering seizures were roughly twice as likely to progress to a MCS as those without seizures, although this was not statistically significant.

Patients with severe brain injuries, whether traumatic or non-traumatic in origin, often progress from an initial coma towards a VS and subsequently towards a MCS. However, they do not always reach full consciousness or self-awareness. Various studies in the literature analyse the probability of emergence from VS, even after more than one month’s duration (DeFina et al., 2010; Katz et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2000; Gillies and Seshia 1980). Less information is available on the evolution of MCS persisting beyond one month’s duration (Machado et al. 2010; Nakase-Richardson et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2007). The Multi-Society Task Force on the Persistent Vegetative State has formulated several principles (The Multi-Society Task Force on the Persistent Vegetative State, 1994). The prognosis for regaining awareness from a non-traumatic VS is worse than for an equivalent state following a TBI, and the longer patients remain in a VS, the less likely they are to eventually regain awareness. The Task Force’s final conclusion is that late recovery of consciousness in these patients — late meaning after 12 months from onset in TBI and after 3 months from onset in non-traumatic injuries — is very unlikely.

However, the currently available data on this aspect, due to sporadic follow-up reports, incomplete epidemiological data and imprecise diagnoses, are neither adequate nor sufficient to allow reliable estimates of the incidence of late improvement. Late recovery from VS (albeit with persistent severe cognitive impairment) may therefore be more common than thought, and in fact recent articles on patients with acute or post-acute VS report a more favourable long-term prognosis for VS and MCS than in the past (Eilander et al., 2005; Faran et al., 2006; Fins et al., 2007; Sarà et al., 2007; Whyte et al., 2009).

Avesani et al. stress the importance of constant followup of patients with consciousness disorders, to allow adequate monitoring of any changes in their clinical picture, especially when their baseline condition is particularly severe (Avesani et al., 2006).

They described 2 people diagnosed with VS who, at respectively 6 and 12 months after their original trauma, had achieved a moderate level of functional independence following a significant motor and cognitive recovery. Similarly, Estraneo et al. described 6 VS patients who recovered a level of consciousness considerably better than that identified in the Multisociety Task Force prognostic guidelines. This recovery was more evident in younger subjects who had suffered severe TBI (Estraneo et al., 2010).

Luauté et al. studied the prognosis of VS and MCS over a 5-year observation period. They found no instances of improved awareness in any of the 12 VS patients, all of whom either died or remained in a VS. By contrast, MCS patients improved more than one year after the onset of coma (Luauté et al., 2010).

A VS lasting more than one year after TBI or six months after anoxic/vascular disease used to be considered “permanent”, a label implying irreversibility or extreme improbability of an even minimal further improvement. However, according to studies on late recovery of consciousness — beyond 12 months after onset in TBI or 3 months after onset in non-TBI — some patients may have potential for noteworthy additional recovery (Higashi et al., 1981; Levin et al., 1991). In any case, emergence to a state of more consistent consciousness can take months, or even years in rare cases, and is always associated with severe to extremely severe functional disability and a poor functional outcome.

Rates of late emergence from VS, reported in the literature, vary greatly, from 1.6 to 14% (Faran et al., 2006; Andrews, 1993; Childs and Merger, 1996).

Data on emergence from MCS are marred by the poor reliability of the prognostic indicators and probably by the various terminology used in recent years to define emergence from VS. As with VS, the longer MCS persists, the lower the probability of recovery. In a group of acute TBI patients initially in a MCS, 40% will regain full consciousness within 12 weeks of injury, and up to 50% will regain independent function at one year (Giacino et al., 2004).

Lammi et al. found that the recovery of patients after a prolonged MCS varied greatly. The duration of the MCS did not seem to influence the psychosocial outcome, nor did it preclude significant functional recovery (Lammi et al., 2005). Katz et al. demonstrated that patients in VS whose transition to MCS occurred within eight weeks of onset are likely to continue recovering to higher functional levels, with a substantial proportion regaining home independence and resuming productive pursuits. Patients with TBI were more likely than those with a non-TBI aetiology to improve, although significant improvements in the non-TBI group were still possible (Katz et al., 2009).

No neurological interpretation of late recovery from VS has been advanced and early predictors might not apply (McMillan and Herbert, 2004; Voss et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2008), although slow axonal regrowth in brain-damaged patients could be an intriguing hypothesis as a biological mechanism of late recovery (Voss et al., 2006). Taken as a whole, these data confirm that an accurate early diagnosis of patients with consciousness disorders following brain injury is critical for predicting outcome. Diagnostic errors are likely to result in patients being given a worse prognosis, which may restrict their access to services, especially rehabilitation services — this, in particular, is a major concern for these most disabled of patients (Baricich et al., 2017; Taricco et al., 2006) —, and prevent them from receiving the best medical, pharmacological and physiotherapeutic approaches.

Moreover, there is as yet no consensus on the interpretation of seizures in VS patients who subsequently regain consciousness. Electroencephalography does not seem to identify any specific patterns in VS or MCS, nor have any particular value in predicting the prognosis: in some cases essentially normal tracings have been reported (Bernat, 2009). The alpha rhythm is associated with emergence from VS, while there is a lack of systematic EEG data on MCS (Giacino et al., 2005). However, some investigators have described non-tonic-clonic SE in patients with altered consciousness (Lowenstein et al., 1992; Privitera et al., 1994) while Towne et al. stress that coma patients can present nonconvulsive status epilepticus, even without clear clinical epileptiform signs, and this may be an unrecognised cause of alterations of consciousness (Towne et al., 1998). Although, on the basis of our caseload, it is not possible to link anticonvulsant therapy with recovery of consciousness, EEG monitoring should be considered an essential part of the evaluation of VS and MCS patients to avoid both under-diagnosis and under-treatment, resulting in suboptimal management and outcome (Towne et al., 2000). Moreover, other imaging techniques such as PET/CT scanning could play a key role in defining the prognosis of patients affected by severe brain injuries (Picelli et al., 2015; Lupi et al., 2014).

The definition of diagnosis and prognosis of severe acquired brain injuries (sABI) was an important topic discussed during the Italian Consensus Conference held in Salsomaggiore (Parma, Italy) in 2010. De Tanti et al. affirmed that further clinical studies were needed to clarify the basic mechanisms of sABI and to refine diagnosis in order to improve rehabilitation programmes for these patients in the intensive care phase (De Tanti et al., 2015).

Furthermore, as also shown by a recent multicentre study, it is mandatory to develop early rehabilitation programmes in patients with severe brain injuries in order to reduce their hospital stay (Bartolo et al., 2016.).

In conclusion, our data suggest that several variables may increase the likelihood of transition to MCS, namely male sex, youth, a shorter time from onset of VS, diffuse brain injury and the presence of SE.

In addition, at a 4-year follow-up, we observed a transition from VS to MCS in some patients with severe brain injury.

These data highlight the potential importance of long-term monitoring of patients with chronic disorders of consciousness after severe brain injuries; therefore, we should consider implementing adequate follow-up of these patients in order to optimise their access to rehabilitation services.

References

- Alexander E, Jr, Kushner J, Six EG. Brainstem hemorrhages and increased intracranial pressure: from Duret to computed tomography. Surg Neuro. 1982;17:107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(82)80031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, Brain Injury-Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group, Disorders of Consciousness Task Force. Assessment scales for disorders of consciousness: evidence-based recommendations for clinical practice and research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1795–1813. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.07.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews K. Recovery of patients after four months or more in the persistent vegetative state. 1993;306:1597–1600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6892.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avesani R, Gambini MG, Albertini G. The vegetative state: A report of two cases with a long-term follow-up. Brain Injury. 2006;20:333–338. doi: 10.1080/02699050500487605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baricich A, Amico AP, Zampolini M, Gimigliano F, Cisari C, Fiore P. People with Spinal Cord Injury in Italy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:S80–S82. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolo M, Bargellesi S, Castioni CA, Bonaiuti D Intensive Care and Neurorehabilitation Italian Study Group. Early rehabilitation for severe acquired brain injury in intensive care unit: multicenter observational study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;52:90–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat JL. Chronic consciousness disorders. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:381–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.060107.091250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat JL. The natural history of chronic disorders of consciousness. Neurology. 2010;75:206–207. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesarini KG, Hårdemark HG, Persson L. Improved survival after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: review of case management during a 12-year period. J Neurosur. 1999;90:664–672. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.4.0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs NL, Merger WN. Brief report: late improvement in consciousness after posttraumatic vegetative state. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:24–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601043340105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFina PA, Fellus J, Thompson JW, Eller M, Moser RS, Frisina PG, et al. Improving outcomes of severe disorders of consciousness. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2010;28:769–780. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2010-0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong BM. Complete Motor Locked-in and Consequences for the Concept of Minimally Conscious State. J Head Trauma Rehabil Feb. 2012;11 doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31823c9eaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Tanti A, Zampolini M, Pregno S CC3 Group. Recommendations for clinical practice and research in severe brain injury in intensive rehabilitation: the Italian Consensus Conference. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51:89–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilander HJ, Wijnen VJM, Scheirs JGM, De Kort PLM, Prevo AJH. Children and young adults in a prolonged un-conscious state due to severe brain injury: outcome after an early intensive neurorehabilitation programme. Brain Inj. 2005;19:425–436. doi: 10.1080/02699050400025299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estraneo A, Moretta P, Loreto V, Lanzillo B, Santoro L, Trojano L. Late recovery after traumatic, anoxic, or hemorrhagic long-lasting vegetative state. Neurology. 2010;75:239–245. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e8cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faran S, Vatine JJ, Lazary A, Ohry A, Birbaumer N, Kotchoubey B. Late recovery from permanent traumatic vegetative state heralded by event-related potentials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;277:998–1000. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.076554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fins JJ, Schiff ND, Foley KM. Late recovery from the minimally conscious state: ethical and policy implications. Neurology. 2007;68:304–307. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252376.43779.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacino JT, Ashwal S, Childs N, Cranford R, Jennett B, Katz DI, Kelly JP, Rosenberg JH, Whyte J, Zafonte RD, Zasler ND. The minimally conscious state: definition and diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 2002;58:349–353. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacino JT, Kalmar K, Whyte J. The JFK Coma Recovery Scale-Revised: measurement characteristics and diagnostic utility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:2020–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacino JT, Schnakers C, Rodriguez-Moreno D, Kalmar K, Schiff N, Hirsch J. Behavioral assessment in patients with disorders of consciousness: gold standard or fool’s gold? Prog Brain Res. 2009;177:33–48. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17704-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacino JT, Smart CM. Recent advances in behavioral assessment of individuals with disorders of consciousness. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20:614–619. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282f189ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacino JT, Whyte J. The vegetative and minimally conscious states: current knowledge and remaining questions. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20:30–50. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacino JT, Zasler ND, Katz DI, Kelly JP, Rosenberg JH, Filley CM. Development of practice guidelines for assessment and management of the vegetative and minimally conscious states. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1997;12:79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gillies JD, Seshia SS. Vegetative state following coma in childhood: evolution and outcome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1980;122:642–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1980.tb04378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen C, Malkmus D, Durham P. Rehabilitation of the head injured adult. Comprehensive physical management. Professional Staff Association of Rancho Los Amigos Hospital, Inc; Downey: 1979. Levels of Cognitive Functioning. [Google Scholar]

- Higashi K, Hatano M, Abiko TS. Five-year followup study of patients with persistent vegetative state. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981;44:552–554. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.6.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DI, Polyak M, Coughlan D, Nichols M, Roche A. Natural history of recovery from brain injury after prolonged disorders of consciousness: outcome of patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation with 1–4 year follow-up. Prog Brain Res. 2009;177:73–88. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17707-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khot S, Tirschwell DL. Long-term neurological complications after hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Semin Neurol. 2006;26:422–431. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-948323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammi M, Smith V, Tate R, Taylor C. The Minimally Consciuos State and recovery potential: a follow-up study 2 to 5 years after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:746–54. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laureys S, Celesia GG, Cohadon F, Lavrijsen J, León-Carrión J, Sannita WG, et al. European Task Force on Disorders of Consciousness. Unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: a new name for the vegetative state or apallic syndrome. BMC Med. 2010;8:68–73. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luauté J, Maucort-Boulch D, Tell L, Quelard F, Sarraf T, Iwaz J. Long-term outcomes of chronic minimally conscious and vegetative states. Neurology. 2010;75:246–252. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e8df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin HS, Saydjari C, Eisenberg HM. Vegetative state after closed-head injury: a Traumatic Coma Data Bank report. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:580–585. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530180032013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein DH, Aminoff MJ. Clinical and EEG features of status epilepticus in comatose patients. Neurology. 1992;42:100–104. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupi A, Bertagnoni G, Borghero A, Picelli A, Cuccurullo V, Zanco P. 18FDG-PET/CT in traumatic brain injury patients: the relative hypermetabolism of vermis cerebelli as a medium and long term predictor of outcome. Curr Radiopharm. 2014;7:57–62. doi: 10.2174/1874471007666140411103819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado C, Perez-Nellar J, Rodríguez R, Scherle C, Korein J. Emergence from minimally conscious state: insights from evaluation of posttraumatic confusion. 2010;74:1156–1157. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d5df0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan TM, Herbert CM. Further recovery in a potential treatment withdrawal case 10 years after brain injury. Brain Injury. 2004;18:935–940. doi: 10.1080/02699050410001675915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase-Richardson R, Yablon SA, Sherer M, Nick TG, Evans CC. Emergence from minimally conscious state: insights from evaluation of posttraumatic confusion. Neurology. 2009;73:1120–1126. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bacf34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picelli A, Borghero A, Lupi A, Bertagnoni G. PET/CT scan in traumatic brain injury: a new frontier for the prognosis from cerebellum activity? Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51:849–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povlishock JT, Katz DI. Update of neuropathology and neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20:76–94. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privitera M, Hoffman M, Moore JL, Jester D. EEG detection of nontonic-clonic status epilepticus in patients with altered consciousness. Epilepsy Res. 1994;18:155–166. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosanova M, Gosseries O, Casarotto S, Boly M, Casali AG, Bruno MA. Recovery of cortical effective connectivity and recovery of consciousness in vegetative patients. Brain. 2012;135:1308–1320. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarà M, Sacco S, Cipolla F, Onorati P, Scoppetta C, Albertini G, Carolei A. An unexpected recovery from permanent vegetative state. Brain Inj. 2007;21:101–103. doi: 10.1080/02699050601151761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, McDonald C, Dawson K, Lewis S, Pringle AM, Smith S. Zolpidem in a minimally conscious state. Brain Inj. 2008;22:103–106. doi: 10.1080/02699050701829704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taricco M, De Tanti A, Boldrini P, Gatta G. National Consensus Conference. The rehabilitation management of traumatic brain injury patients during the acute phase: criteria for referral and transfer from intensive care units to rehabilitative facilities. Eura Medicophys. 2006;42:73–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CM, Aird VH, Tate RL, Lammi MH. Sequence of recovery during the course of emergence from the minimally conscious state. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:521–525. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Multi-Society Task Force on the Persistent Vegetative State. Statement on medical aspects of the persistent vegetative state. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1499–1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405263302107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut A, Bruno MA, Chatelle C, Gosseries O, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Demertzi A. Metabolic activity in external and internal awareness networks in severely brain-damaged patients. J Rehabil Med Mar. 2012;19 doi: 10.2340/16501977-0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towne AR, Waterhouse EJ, Boggs JG, Garnett LK, Brown AJ, Smith JR. Prevalence of nonconvulsive status epilepticus in comatose patients. Neurology. 2000;54:340–345. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towne AR, Waterhouse EJ, Morton LD, Kopec Garnett L, Brown AJ, DeLorenzo RJ. Unrecognized nonconvulsive status epilepticus in comatose patients. Epilepsia. 1998;39(suppl 6):3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Voss HU, Ulug AM, Dyke JP, Watts R, Kobylarz EJ, Mc-Candliss BD. Possible axonal regrowth in late recovery from the minimally conscious state. Journal of Clinical Investigations. 2006;116:2005–2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI27021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P, Assal G. Lesions of the corpus callosum and syndromes of interhemispheric disconnection of traumatic origin. Neurochirurgie. 1995;41:98–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte J, Gosseries O, Chervoneva I. Predictors of short-term outcome in brain-injured patients with disorders of consciousness. Prog Brain Res. 2009;177:63–72. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17706-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SL, Gill-Thwaites H. Early indication of emergence from vegetative state derived from assessments with the SMART - a preliminary report. Brain Inj. 2000;14:319–331. doi: 10.1080/026990500120619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]