Abstract

The presence of psychological comorbidities, specifically anxiety and depression, is well documented in IBD. The drivers of these conditions typically reflect four areas of concern: disease impact, treatment concerns, intimacy, and stigma. Various demographic and disease characteristics increase risk for psychological distress. However, the risk for anxiety and depression is consistent throughout IBD course and is independent of disease activity. Early intervention before psychological distress becomes uncontrolled is ideal, but mental health often left unaddressed during patient visits. Understanding available psychological treatments and establishing referral resources is an important part of the evolution of IBD patient care.

Keywords: Inflammatory Bowel Disease, psychology, mental health, psychotherapy, behavioral interventions

Introduction

Psychosocial challenges for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients are critical considerations when managing care. These constructs have garnered much needed attention in recent years. However, psychological research only represents approximately 2% of all published IBD-related inquiry (74 of 4,470 articles indexed on PubMed in 2016) and translation of research findings to clinical practice is challenging. Considerable evidence shows IBD impacts health related quality of life1, causes psychological distress2, and psychological and behavioral interventions can mitigate some negative impacts to patient outcomes3, 4.

Anxiety and depression are the most commonly researched psychological comorbidities in IBD. A 2016 systematic review reports the prevalence of clinical anxiety disorders is 21% in IBD patients while the prevalence of anxiety symptoms (e.g. sub-clinical scores on standardized anxiety measures) is 35%; rates of depression are somewhat lower, with 15% having a depressive disorder and 22% reporting depressive symptoms2. Detailed reviews of anxiety and depression in IBD are conducted elsewhere. Rather, we aim to review potential psychosocial challenges for IBD patients within these two overarching, often-used terms and provide recommendations for appropriate interventions to mitigate negative impacts on patient care and outcomes.

Psychological Considerations in IBD

We know approximately one third of IBD patients experience anxiety and depression, but what is driving these symptoms? Drossman’s 1991 study outlines four main areas of patient concerns: disease impact, treatment, intimacy, and stigma5. Subsequent research on IBD psychosocial issues generally tracks these domains, with additional nuance emerging as investigation in this area evolves6. Evidence based psychological treatments exist for most IBD mental health concerns. Of available psychotherapies, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), originally developed to treat depression7, shows consistent efficacy when applied to a wide range of psychiatric and medical conditions, including IBD, and may be effective in mitigating several of the psychological issues outlined in this review.

What is CBT?

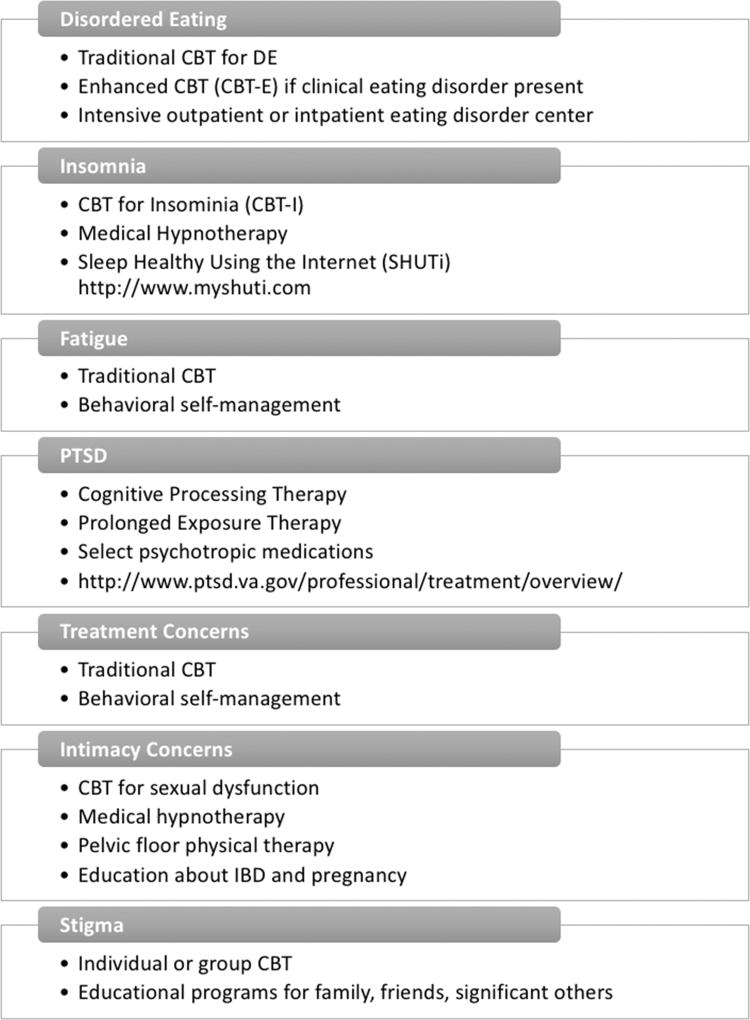

In CBT, patients are taught to understand the relationship between situations, thoughts, behaviors, physical reactions, and emotions. Patients learn to change thoughts (through cognitive reframing), behaviors (through scheduled or prescribed changes in activity or responses), and levels of physiologic arousal (through relaxation exercises) in order to reduce emotional distress. In behavioral medicine settings, the CBT model is used to help patients cope with distress related specifically to a medical condition. In IBD, CBT has not been shown to consistently alter disease outcomes, but is effective in improving quality of life, coping skills, medical adherence, and underlying symptoms of anxiety or depression8. As such, as we outline psychological distress in IBD patients, potential CBT-based interventions are proposed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Evidence Based Behavioral Interventions for IBD Mental Health Concerns

IBD Impact

Disordered Eating

Food is a fundamentally important aspect of life that can pose particular challenges for IBD patients. A majority of patients hold strong beliefs about how food impacts their illness, but many do not receive adequate help9, 10. Many IBD patients determine what foods are “safe” versus “unsafe” based on subjective experience11, 12. Some turn to one of many popular exclusion diets. Following long-term dietary regimens can produce maladaptive attitudes, including anxiety, toward food13. While clinical eating disorder pathology (i.e., anorexia nervosa) is possible, the more common risk in IBD is development of disordered eating (DE), or dysfunctional eating behaviors such as skipping meals, binge eating, restricting, and fasting14. We recommend The Food Related Quality of Life Questionnaire to assess IBD patient eating concerns.

People with GI illness, including IBD, are at higher risk for developing DE which associated with increased psychological distress and symptom severity15, and is independent of remission status16. Patients may limit social interactions to mitigate food anxiety, which in turn increases psychological distress, creating a vicious cycle16,17. Depending on how restrictive the diet is, nutritional deficiencies may develop from DE, further complicating treatment. Over-nutrition is also a growing problem in IBD with rates of overweight and obesity similar to the general population18, 19, especially in patients with mild disease or in remission. IBD patients are susceptible to DE habits which may increase caloric intake including binges or emotional eating associated with anxiety or depression.

Insomnia and Fatigue

Sleep is important in IBD management as insomnia is known to impact both physical and psychological well-being. A large body of research demonstrates sleep problems are associated with poorer outcomes in anxiety and depression20 and insomnia predicts future mental health problems in individuals without current psychological distress21. Fatigue is one of the most burdensome IBD symptoms22 and is highly prevalent, with 44–86% of patients with active disease and 22–41% with inactive disease reporting clinically significant levels of fatigue22–24. Being female, psychological distress, disease-related worry, low quality of life, disability, and poor sleep quality are all associated with greater fatigue. Two measures of IBD fatigue include the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Fatigue Scale and the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

To date, no study evaluates post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in IBD. However, based on the nature of IBD it is plausible PTSD may be present in a subset of patients. PTSD symptoms may increase over time or be intermittent throughout the course of illness and include intrusive thoughts, nightmares, or flashbacks25 avoidance of thoughts or feelings related to the trauma, social withdrawal, and emotional numbing25. There are multiple risk factors for PTSD including heightened psychological distress following diagnosis, female sex26, lower socioeconomic status27, more severe disease28, uncontrolled pain, younger age at diagnosis28, 29, type of surgery, subjective intensity of symptoms30, and at least one disease recurrence.

Compared to trauma associated with combat or natural disasters, the PTSD-stressor in IBD comes from an internal event (i.e. the disease), as such the IBD patient cannot flee the actual threat. Avoidance behaviors may manifest in treatment non-adherence31–33 or missed follow-up care34 as these may be triggers of intrusive symptoms. Conversely, PTSD may drive health-related anxiety resulting in excessive healthcare utilization and costs35 due to somatic symptoms or pain perception36 not associated with IBD disease activity. PTSD is also associated with enhanced cellular immune response37 and alterations to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis38, thereby complicating its relationship with IBD disease course. Rapid assessment tools exist to screen IBD patients for PTSD, including the Primary Care PTSD Screen and PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version.

IBD Treatment Concerns

A recent paradigm shift in IBD treatment outlines top-down (i.e. biologic medication first) versus traditional bottom-up approaches39; 24% of IBD patients were current or past users of biologic medications in 201440 with increasing trends of use41. Starting a biologic medication may cause distress in some patients. Escalation in therapy may serve as a sign of worsening disease42. Some patients may be afraid of potential side effects of biologic therapies while others may be more tolerable of risk than their physician43. Injection anxiety is an underdeveloped area of research in IBD but is associated with lower medication adherence in other illness groups44, 45. If anxiety poses a barrier to initiating or adhering to a biologic, or other IBD medications, traditional CBT or behavioral self-management (outlined below) are effective treatments.

Intimacy Concerns

Body image

Up to two thirds of patients with IBD report some body image dissatisfaction46, 47, with higher rates in women (75% versus 50% of men). Dissatisfaction is related to weight loss, hair loss, weight gain from corticosteroids, extra-intestinal dermatologic manifestations, increased disease activity, high symptom burden, longer duration of steroid use, other extra-intestinal symptoms including fistulas, and surgical history47, 48. Negative body image is logically associated with decreased quality of life and increased psychological distress46, 49, however it is infrequently discussed during routine medical visits. The 9-item Body Image Scale is recommended for assessment.

Sexuality

Up to 31% of men and 80% of women with IBD report low or no interest in sex50, 51. Depressed mood is the strongest predictor of sexual dysfunction across genders. Patients with prior surgical resection report lower libido and less frequent sexual activity compared to non-operated patients52. Permanent ostomy also impairs sexual functioning in both men and women, with an increased rate of anorgasmia in female ostomy patients. Longer disease duration is associated with fewer sexual problems, possibly due to increased coping skills over time50. Twenty-five percent of females report pain during intercourse, which is not associated with disease type or activity, use of steroids, or presence of perianal disease and may be related to pelvic floor dysfunction. Unfortunately, many providers do not inquire about sexual functioning during regular visits53. In a survey of 64 women with IBD, only 12 (18.8%) had discussed sexuality/sexual functioning with their gastroenterologist, and of those who did, 100% were patient-generated conversations. Several validated assessment tools exist including the Sexual Functions Questionnaire, International Index of Erectile Function, and Female Sexual Function Index.

Childbearing Concerns

Many women with IBD report a higher rate of voluntary childlessness54, 55: 18% in CD and 14% in UC compared to 6.2% in the general population. Primary motivators include worry about IBD heritability, risk of congenital abnormalities, and medication teratogenicity. Common pregnancy concerns, which are associated with poor understanding of actual risks of pregnancy with IBD56, include infertility, effects of medications on the fetus, vaginal delivery versus cesarean section, and breastfeeding57. However, only 28% of women with IBD demonstrate “good” to “very good” knowledge in these areas58.

Stigma

While stigmatization is widely studied in HIV/AIDS and mental illness, research into IBD-related stigma is relatively new. A 2016 comprehensive review of IBD stigma finds IBD patients perceive that others hold stigmatizing views toward them and the disease, some patients internalize these negative beliefs while others resist them, and stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors exist among those without IBD59, 60. Like stigma toward other diseases, IBD stigma is associated with poorer outcomes61 and may cause or exacerbate feelings of depression or anxiety. Clinicians should be mindful of potential stigma being experienced by their patients and inquire about its impacts on social experiences and interpersonal relationships.

Integrating Mental Health into IBD Patient Care

This review, as several others, demonstrates IBD patients have mental health needs that, if unchecked, can have direct and indirect impacts on patient outcomes. Yet, integration of behavioral medicine services into gastroenterology practice is limited, mostly to tertiary, university-based centers in major metropolitan areas. How, then, can the vast majority of gastroenterologists ensure effective management of the mental health issues of their patients?

Psychological distress over the disease course of IBD is consistent and can be independent from disease activity62, so merely treating IBD symptoms is insufficient in its alleviation. Newly diagnosed patients have the greatest need for psychotherapy63 and early intervention, before the patient is significantly distressed, leads to better outcomes64. Unfortunately, several barriers exist including social stigma, financial burdens, and a lack of mental health professionals trained in working with IBD patients65, preventing timely referral to a mental health specialist; only 15% of IBD patients report referral for mental health treatment while half would desire such referral65.

Two 2017 studies find most patients and providers do not discuss how IBD may affect quality of life, emotional functioning, and overall mental health during routine visits65, both in the U.S. and Europe42; seventy-five percent of patients would like their providers to address these impacts. Gastroenterologists may feel compelled to try to treat mental health themselves, feel unsure of how to broach the topic of mental health, not detect psychological distress66, or prioritize other disease management issues due to appointment time constraints67.

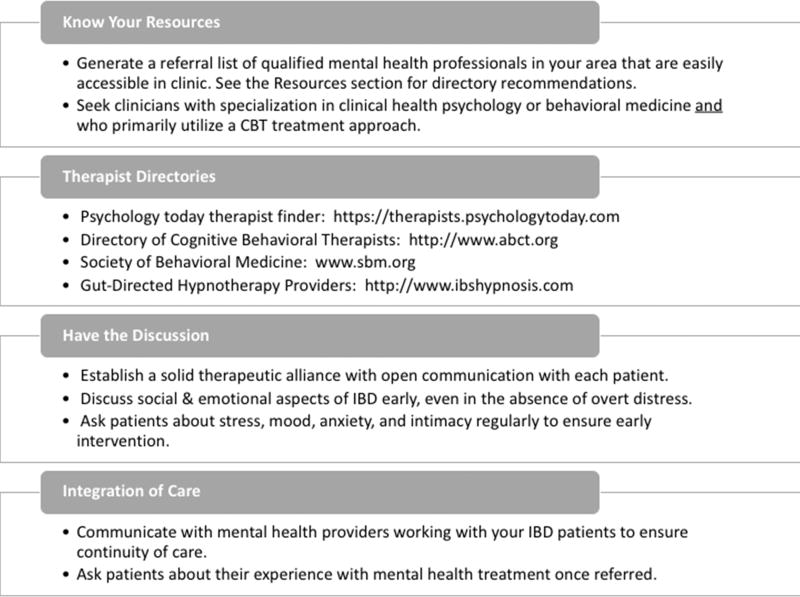

In the era of the rapid medical encounter, it is vital for the practicing gastroenterologist to efficiently recognize potential psychosocial issues that may impact patient outcomes and establish a referral process for reliable and reputable mental health treatments. Figure 2 provides recommendations for streamlining referrals to mental health services. In addition to CBT approaches previously described, additional psychological interventions are available and may be efficacious for some IBD patients.

Figure 2.

Integrating Mental Health Services into IBD Patient Care

Behavioral Self-Management

For patients who do not exhibit psychological distress and/or who are not interested in traditional psychotherapy, Behavioral or Self-Management Therapy may be effective68, 69. In this treatment, the goal is to target negative health behaviors (e.g. poor medication compliance, dietary non-adherence) to improve overall physical health. This therapy is informed by the CBT model but does not incorporate the cognitive component of traditional CBT, which evaluates negative or distressing thought patterns.

Medical Hypnotherapy

Medical hypnotherapy is an effective intervention for many diseases and disorders. Gut-directed hypnotherapy is a variation of medical hypnotherapy that focuses hypnotic suggestions on the health of the gastrointestinal tract4, 70, 71. This treatment typically involves 7–12 weekly sessions where patients learn to achieve a deep hypnotic state and are then led through a series of scripted, gut-focused imageries with suggestions. Patients practice these exercises at home using audio recordings. Recent pediatric research suggests self-directed hypnotherapy is as effective in treating functional abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome as treatment with a clinician72, which would make this treatment more accessible.

In IBD, a handful of studies (limited by small sample sizes) evaluate the efficacy of gut-directed hypnotherapy. Findings show reduced rectal mucosal inflammatory responses (IL-6, IL-13, TNF-α, substance P, histamine) in patients after one session73, prolonged clinical remission by approximately 2.5 months in patients with quiescent UC compared to controls after 7 sessions of hypnotherapy74, and maintained remission in one quarter of patients with active IBD at 5 year follow up after 12 sessions75.

Telemental Health

Telemental health interventions are a promising alternative for IBD patients needing behavioral intervention. Four studies on web-based interventions exist for IBD76. The existing literature is promising, suggesting improved outcomes in IBD with use of these interventions77, 78. Web-based psychological interventions are effective in treating depression and anxiety79–81, insomnia82, and irritable bowel syndrome83, 84. These strategies may bridge the treatment gap that currently exists for integrated behavioral medicine practice in gastroenterology.

Conclusions

Psychological considerations are vital for proper IBD management as IBD patients experience a complex interplay between their physical and emotional health. While there is a dearth of GI psychologists at present, identifying mental health clinicians with chronic illness experience trained in evidenced-based interventions such as CBT should be a priority. Patients express desires for, at a minimum, conversations about IBD’s impact on quality of life and emotional well-being yet these needs remain unmet in most. While these topics may be difficult or potentially time consuming, left unchecked psychological distress can hamper disease and symptom management. As IBD treatment continues to evolve, giving appropriate credence to the psychology of the IBD patient will lead to improved patient satisfaction and care.

Key Points.

Psychological health is an important yet neglected aspect of IBD patient care, with challenges in identifying proper treatments and mental health resources.

Psychological distress typically occurs due to disease impact, treatment concerns, intimacy concerns, and stigma. Left untreated, psychological distress has direct negative impacts on patient outcomes.

Several evidence-based treatments are available for most causes of psychological distress in IBD patients, the most widely accepted being rooted in cognitive behavioral theory.

Patients want their gastroenterologist to discuss psychological issues during routine visits, and many are open to or desire referral to qualified mental health providers for concurrent treatment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Tiffany Taft has an ongoing speaker relationship with Janssen pharmaceuticals for patient education programs. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Sainsbury A, Heatley RV. Review article: psychosocial factors in the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:499–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuendorf R, Harding A, Stello N, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2016;87:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiest KM, Bernstein CN, Walker JR, et al. Systematic review of interventions for depression and anxiety in persons with inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:404. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2204-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters SL, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Review article: gut-directed hypnotherapy in the management of irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1104–15. doi: 10.1111/apt.13202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li ZM, et al. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med. 1991;53:701–12. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199111000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casati J, Toner BB, de Rooy EC, et al. Concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a review of emerging themes. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:26–31. doi: 10.1023/a:1005492806777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck AT. The past and future of cognitive therapy. J Psychother Pract Res. 1997;6:276–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knowles SR, Monshat K, Castle DJ. The efficacy and methodological challenges of psychotherapy for adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2704–15. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318296ae5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prince A, Whelan K, Moosa A, et al. Nutritional problems in inflammatory bowel disease: the patient perspective. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:443–50. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinsley A, Ehrlich OG, Hwang C, et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Regarding the Role of Nutrition in IBD Among Patients and Providers. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2474–81. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Triggs CM, Munday K, Hu R, et al. Dietary factors in chronic inflammation: food tolerances and intolerances of a New Zealand Caucasian Crohn's disease population. Mutat Res. 2010;690:123–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Limdi JK, Aggarwal D, McLaughlin JT. Dietary Practices and Beliefs in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:164–70. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quick VM, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Neumark-Sztainer D. Chronic illness and disordered eating: a discussion of the literature. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:277–86. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grilo C. Eating and weight disorders. New York: Psychology Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satherley R, Howard R, Higgs S. Disordered eating practices in gastrointestinal disorders. Appetite. 2015;84:240–50. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes L, Lindsay JO, Lomer MC, et al. Psychosocial Impact of Food and Nutrition in people with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: a Qualitative Study. Gut. 2013;62 doi: 10.1111/jhn.12668. N/A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daniel JM. Young adults' perceptions of living with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2002;25:83–94. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nic Suibhne T, Raftery TC, McMahon O, et al. High prevalence of overweight and obesity in adults with Crohn's disease: associations with disease and lifestyle factors. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steed H, Walsh S, Reynolds N. A brief report of the epidemiology of obesity in the inflammatory bowel disease population of Tayside, Scotland. Obes Facts. 2009;2:370–2. doi: 10.1159/000262276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranjbaran Z, Keefer L, Farhadi A, et al. Impact of sleep disturbances in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1748–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson EO, Roth T, Breslau N. The association of insomnia with anxiety disorders and depression: exploration of the direction of risk. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:700–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graff LA, Vincent N, Walker JR, et al. A population-based study of fatigue and sleep difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1882–9. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, et al. Chronic fatigue is associated with increased disease-related worries and concerns in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:445–52. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i5.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gracie DJ, Ford AC. Letter: causes of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease remain uncertain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:762–763. doi: 10.1111/apt.13922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tedstone JE, Tarrier N. Posttraumatic stress disorder following medical illness and treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:409–48. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hilerio CM, Martinez J, Zorrilla CD, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and adherence among women living with HIV. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:S5-47-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cordova MJ, Andrykowski MA, Kenady DE, et al. Frequency and correlates of posttraumatic-stress-disorder-like symptoms after treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:981–6. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epping-Jordan JE, Compas BE, Osowiecki DM, et al. Psychological adjustment in breast cancer: processes of emotional distress. Health Psychol. 1999;18:315–26. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennett P, Conway M, Clatworthy J, et al. Predicting post-traumatic symptoms in cardiac patients. Heart Lung. 2001;30:458–65. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.118296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruggimann L, Annoni JM, Staub F, et al. Chronic posttraumatic stress symptoms after nonsevere stroke. Neurology. 2006;66:513–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194210.98757.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, et al. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:253–61. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shemesh E, Rudnick A, Kaluski E, et al. A prospective study of posttraumatic stress symptoms and nonadherence in survivors of a myocardial infarction (MI) Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:215–22. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kronish IM, Edmondson D, Goldfinger JZ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and adherence to medications in survivors of strokes and transient ischemic attacks. Stroke. 2012;43:2192–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.655209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alonzo AA. Acute myocardial infarction and posttraumatic stress disorder: the consequences of cumulative adversity. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 1999;13:33–45. doi: 10.1097/00005082-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marciniak MD, Lage MJ, Dunayevich E, et al. The cost of treating anxiety: the medical and demographic correlates that impact total medical costs. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:178–84. doi: 10.1002/da.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherman JJ, Turk DC, Okifuji A. Prevalence and impact of posttraumatic stress disorder-like symptoms on patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Clin J Pain. 2000;16:127–34. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200006000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altemus M, Dhabhar FS, Yang R. Immune function in PTSD. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:167–83. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Kloet CS, Vermetten E, Geuze E, et al. Assessment of HPA-axis function in posttraumatic stress disorder: pharmacological and non-pharmacological challenge tests, a review. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:550–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devlin SM, Panaccione R. Evolving inflammatory bowel disease treatment paradigms: top-down versus step-up. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vester-Andersen MK, Prosberg MV, Jess T, et al. Disease course and surgery rates in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based, 7-year follow-up study in the era of immunomodulating therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:705–14. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duricova D. What Can We Learn from Epidemiological Studies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease? Dig Dis. 2017;35:69–73. doi: 10.1159/000449086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubin DT, Dubinsky MC, Martino S, et al. Communication Between Physicians and Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: Reflections and Insights from a Qualitative Study of In-Office Patient-Physician Visits. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:494–501. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson FR, Hauber B, Ozdemir S, et al. Are gastroenterologists less tolerant of treatment risks than patients? Benefit-risk preferences in Crohn's disease management. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16:616–28. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.8.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turner AP, Williams RM, Sloan AP, et al. Injection anxiety remains a long-term barrier to medication adherence in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54:116–21. doi: 10.1037/a0014460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mann DM, Ponieman D, Leventhal H, et al. Predictors of adherence to diabetes medications: the role of disease and medication beliefs. J Behav Med. 2009;32:278–84. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDermott E, Mullen G, Moloney J, et al. Body image dissatisfaction: clinical features, and psychosocial disability in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:353–60. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muller KR, Prosser R, Bampton P, et al. Female gender and surgery impair relationships, body image, and sexuality in inflammatory bowel disease: patient perceptions. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:657–63. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trindade IA, Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J. The effects of body image impairment on the quality of life of non-operated Portuguese female IBD patients. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:429–436. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunker MS, Stiggelbout AM, van Hogezand RA, et al. Cosmesis and body image after laparoscopic-assisted and open ileocolic resection for Crohn's disease. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1334–40. doi: 10.1007/s004649900851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Timmer A, Bauer A, Kemptner D, et al. Determinants of male sexual function in inflammatory bowel disease: a survey-based cross-sectional analysis in 280 men. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1236–43. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Timmer A, Kemptner D, Bauer A, et al. Determinants of female sexual function in inflammatory bowel disease: a survey based cross-sectional analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bel LG, Vollebregt AM, Van der Meulen-de Jong AE, et al. Sexual Dysfunctions in Men and Women with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Influence of IBD-Related Clinical Factors and Depression on Sexual Function. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1557–67. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borum ML, Igiehon E, Shafa S. Physicians may inadequately address sexuality in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:181. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mountifield R, Bampton P, Prosser R, et al. Fear and fertility in inflammatory bowel disease: a mismatch of perception and reality affects family planning decisions. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:720–5. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marri SR, Ahn C, Buchman AL. Voluntary childlessness is increased in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:591–9. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Selinger CP, Eaden J, Selby W, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and pregnancy: lack of knowledge is associated with negative views. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nguyen GC, Seow CH, Maxwell C, et al. The Toronto Consensus Statements for the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:734–757. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Selinger CP, Eaden J, Selby W, et al. Patients' knowledge of pregnancy-related issues in inflammatory bowel disease and validation of a novel assessment tool ('CCPKnow') Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taft TH, Keefer L. A systematic review of disease-related stigmatization in patients living with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:49–58. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S83533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taft TH, Bedell A, Naftaly J, et al. Stigmatization toward irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease in an online cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29 doi: 10.1111/nmo.12921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taft TH, Keefer L, Leonhard C, et al. Impact of perceived stigma on inflammatory bowel disease patient outcomes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1224–32. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lix LM, Graff LA, Walker JR, et al. Longitudinal study of quality of life and psychological functioning for active, fluctuating, and inactive disease patterns in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1575–84. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miehsler W, Weichselberger M, Offerlbauer-Ernst A, et al. Which patients with IBD need psychological interventions? A controlled study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1273–80. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Evers AW, Kraaimaat FW, van Riel PL, et al. Tailored cognitive-behavioral therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis for patients at risk: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2002;100:141–53. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quinton S, Bedell A, Craven M, et al. Disparities in the Integration of Mental Health Treatment in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Patient Care. Gastroenterology. 2017 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keefer L, Sayuk G, Bratten J, et al. Multicenter study of gastroenterologists' ability to identify anxiety and depression in a new patient encounter and its impact on diagnosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:667–71. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815e84ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spiegel BM, Gralnek IM, Bolus R, et al. Clinical determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1773–80. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keefer L, Doerfler B, Artz C. Optimizing management of Crohn's disease within a project management framework: results of a pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:254–60. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keefer L, Kiebles JL, Kwiatek MA, et al. The potential role of a self-management intervention for ulcerative colitis: a brief report from the ulcerative colitis hypnotherapy trial. Biol Res Nurs. 2012;14:71–7. doi: 10.1177/1099800410397629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Riehl ME, Keefer L. Hypnotherapy for Esophageal Disorders. Am J Clin Hypn. 2015;58:22–33. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2015.1025355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whorwell PJ. Review article: The history of hypnotherapy and its role in the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:1061–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rutten JM, Vlieger AM, Frankenhuis C, et al. Home-Based Hypnotherapy Self-exercises vs Individual Hypnotherapy With a Therapist for Treatment of Pediatric Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Functional Abdominal Pain, or Functional Abdominal Pain Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2017 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mawdsley JE, Jenkins DG, Macey MG, et al. The effect of hypnosis on systemic and rectal mucosal measures of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1460–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Keefer L, Taft TH, Kiebles JL, et al. Gut-directed hypnotherapy significantly augments clinical remission in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:761–71. doi: 10.1111/apt.12449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Miller V, Whorwell PJ. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a role for hypnotherapy? Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2008;56:306–17. doi: 10.1080/00207140802041884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stiles-Shields C, Keefer L. Web-based interventions for ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: systematic review and future directions. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:149–57. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S56069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cross RK, Cheevers N, Rustgi A, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of home telemanagement in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC HAT) Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1018–25. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cross RK, Finkelstein J. Feasibility and acceptance of a home telemanagement system in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 6-month pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:357–64. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9523-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Godleski L, Darkins A, Peters J. Outcomes of 98,609 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs patients enrolled in telemental health services, 2006–2010. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:383–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Backhaus A, Agha Z, Maglione ML, et al. Videoconferencing psychotherapy: a systematic review. Psychol Serv. 2012;9:111–31. doi: 10.1037/a0027924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Steel K, Cox D, Garry H. Therapeutic videoconferencing interventions for the treatment of long-term conditions. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17:109–17. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.100318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van der Zweerde T, Lancee J, Slottje P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of i-Sleep, a guided online CBT intervention, for patients with insomnia in general practice: protocol of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:85. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0783-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ljotsson B, Falk L, Vesterlund AW, et al. Internet-delivered exposure and mindfulness based therapy for irritable bowel syndrome--a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:531–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ljotsson B, Hedman E, Andersson E, et al. Internet-delivered exposure-based treatment vs. stress management for irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1481–91. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]