Abstract

Objective

To study the relation between rainfall and outpatient visits for joint or back pain in a large patient population.

Design

Observational study.

Setting

US Medicare insurance claims data linked to rainfall data from US weather stations.

Participants

1 552 842 adults aged ≥65 years attending a total of 11 673 392 outpatient visits with a general internist during 2008-12.

Main outcome measures

The proportion of outpatient visits for joint or back pain related conditions (rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, spondylosis, intervertebral disc disorders, and other non-traumatic joint disorders) was compared between rainy days and non-rainy days, adjusting for patient characteristics, chronic conditions, and geographic fixed effects (thereby comparing rates of joint or back pain related outpatient visits on rainy days versus non-rainy days within the same area).

Results

Of the 11 673 392 outpatient visits by Medicare beneficiaries, 2 095 761 (18.0%) occurred on rainy days. In unadjusted and adjusted analyses, the difference in the proportion of patients with joint or back pain between rainy days and non-rainy days was significant (unadjusted, 6.23% v 6.42% of visits, P<0.001; adjusted, 6.35% v 6.39%, P=0.05), but the difference was in the opposite anticipated direction and was so small that it is unlikely to be clinically meaningful. No statistically significant relation was found between the proportion of claims for joint or back pain and the number of rainy days in the week of the outpatient visit. No relation was found among a subgroup of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Conclusion

In a large analysis of older Americans insured by Medicare, no relation was found between rainfall and outpatient visits for joint or back pain. A relation may still exist, and therefore larger, more detailed data on disease severity and pain would be useful to support the validity of this commonly held belief.

Introduction

Many people believe that changes in weather conditions—including increases in humidity, rainfall, or barometric pressure—lead to worsening symptoms of joint or back pain, particularly among those with arthritis. Several studies have explored the relation between various weather patterns and joint pain, reaching mixed conclusions,1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 including the possibility that people perceive patterns (eg, an association between rainfall and joint pain) where none exist.11 Although previous studies have explored a variety of weather conditions and used detailed measures of joint pain, they were survey based and included small numbers of patients.

Using data on millions of outpatient visits of older Americans, linked to data on daily rainfall, we analyzed the relation between rainfall and outpatient visits for joint or back pain, or both.

Methods

Data

Our study combined two primary datasets, the first including information on primary care visits for joint or back pain, or both among US Medicare beneficiaries, and the second including detailed information on daily rainfall levels by geographic zip code. To obtain information on outpatient visits related to joint or back pain, we used the 2008-12 US Medicare 20% Carrier Files, a database of all Medicare claims for a 20% simple random sample of Medicare beneficiaries. These data include information on diagnosis codes, place of treatment, and patients’ personal characteristics and chronic conditions. We identified all patients aged 65 years or more who had an outpatient visit with a general internist during 2008-12.

For information on rainfall, we used the Global Historical Climatology Network Daily database at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.12 This database included daily precipitation measurements drawn from 3257 weather stations across the US during 2008-12. To combine the two datasets, we identified the latitude and longitude of the centroid of each Medicare beneficiary’s zip code of residence and matched to the nearest weather station. We excluded zip codes further than 30 miles from a weather station.

Identification of joint and back pain episodes

We identified outpatient visits according to Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System evaluation and management codes 99201-99205 and 99211-99215. Our primary outcome of interest was whether a visit included an ICD-9 (international classification of disease, ninth revision) diagnosis code for a condition reflecting joint or back pain: rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, spondylosis, intervertebral disc disorders, and other non-traumatic joint disorders. We restricted our analysis to visits to general internists (primary care doctors who completed residency in internal medicine), as opposed to other physicians who may treat patients with joint or back pain, such as orthopedic surgeons, family practitioners, and rheumatologists. We focused on general internists because they most frequently treat patients with joint or back pain and may be better able to see patients at short notice compared with specialist physicians.

We hypothesized that if a true relation between rainfall and joint or back pain exists, patients might be more likely to either acutely seek care from their internists for these conditions during rainy periods or mention these symptoms when seeing an internist during a previously scheduled outpatient visit (ie, a visit booked weeks to months in advance) that happens to occur during a rainy period. In this latter case, the internist may include a joint or back pain related diagnosis on the insurance claim. As it may be difficult for patients with acute joint or back pain during a rainfall to schedule an appointment with their internist on the day symptoms begin, our approach considers the possibility that patients mention joint or back pain to their internist during a previously scheduled visit that happens to occur on a rainy day. In addition, we assessed the association between rainfall and joint or back pain at both day level and week level, the latter analysis allowing for the possibility that appointments with internists could be booked within a few days of a rainy day if not on the rainy day itself.

Classification of precipitation

We used two measures for precipitation. Firstly, we generated an indicator variable for whether precipitation exceeded 0.1 inches (2.54 mm) in an individual’s zip code on the day of the outpatient visit—a precipitation threshold used in previous studies.13 We excluded days without available weather recordings from analyses. Secondly, to explore the potential effects of changes in barometric pressure that might precede or follow precipitation and be associated with increased joint or back pain, we identified the week of an outpatient visit and generated indicators for the number of days that week (range 0-7) the assigned weather station recorded any precipitation. If precipitation or changes in barometric pressure around rainy days increases the number of acute joint or back pain episodes, we would expect the proportion of outpatient visits for these conditions to be higher on rainy days (compared with non-rainy days) or in weeks with relatively more days of rain (compared with weeks with fewer days of rain). In addition to these measures we also considered continuous measures of daily or weekly rainfall, measured in millimeters of rainfall.

Statistical analysis

We estimated a visit level multivariable linear probability model of whether an outpatient visit concerned a joint or back pain related condition (binary variable), as a function of precipitation on the day of the visit (defined as a binary variable in one model and as a continuous measurement in another model). We also estimated a visit level multivariable linear probability model of joint or back pain as a function of the number of days with precipitation during the calendar week of the outpatient visit (and in a separate model, millimeters of rainfall in the week). Because logistic models do not converge given the size of data, we estimated linear probability models.

Additional covariates in each model included patient age, sex, race, chronic conditions (12 conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis), and fixed effects for the assigned weather station. Weather station fixed effects account for time invariant geographic factors that may be correlated with rates of outpatient visits for joint or back pain and rainfall levels. The approach allowed us to effectively compare rates of joint or back pain between periods with and without precipitation within the same geographic region, addressing the concern that the pain rates may systematically differ across regions of varying precipitation levels. To account for correlation of rates of joint or back pain visits within geographic regions, we clustered standard errors at the weather station level.

Additional analyses

In prespecified subgroup analyses we stratified patients by rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis (to assess whether the association between rainfall and joint or back pain would be present only among patients with this condition), age group, US census region, and race. We conducted formal tests of interaction for each subgroup analysis.

We conducted two analyses to account for the difficultly in booking an outpatient visit on the day joint or back pain symptoms begin. Firstly, the week level analysis allowed for the possibility that appointments with internists may be difficult to schedule at short notice on the rainy day but could plausibly be scheduled for later in the week. Secondly, we estimated the same week level model with the primary independent variable being millimeters of rainfall in the previous week (to allow for outpatient visits for joint or back pain in the week after rainfall). Finally, because in our visit level analysis patients may have multiple visits in our data, we conducted an analysis restricted to a patient’s first visit only.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for the design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Results

Our sample included 11 673 392 outpatient visits for Medicare beneficiaries during 2008-12, of which 2 095 761 (18.0%) occurred on rainy days. Patient characteristics, including demographics and chronic conditions, were similar between rainy and non-rainy days, with statistically significant differences being small in absolute terms (table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by precipitation on day of outpatient visit. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | No rain (n=9 577 631) | Rain (n=2 095 761) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 77.1 (0.3) | 77.0 (0.3) |

| Women | 5 955 240 (62.2) | 1 300 298 (62.1) |

| White ethnicity | 8 212 089 (85.8) | 1 828 173 (87.3) |

| Presence of chronic illness: | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 5 621 740 (58.7) | 1 221 287 (58.3) |

| Dementia | 1 325 363 (13.8) | 284 613 (13.6) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 008 665 (21.0) | 443 947 (21.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 372 803 (24.8) | 513 276 (24.5) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3 097 885 (32.4) | 672 027 (32.1) |

| Diabetes | 4 043 526 (42.2) | 880 596 (42.0) |

| Congestive heart failure | 3 315 378 (34.6) | 717 980 (34.3) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 8 152 157 (85.1) | 1 784 397 (85.2) |

| Hypertension | 8 506 941 (88.8) | 1 865 444 (89.0) |

| Previous stroke or transient ischemic attack | 1 767 402 (18.5) | 383 537 (18.3) |

| Cancer | 1 695 309 (17.7) | 371 346 (17.7) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 6 026 728 (62.9) | 1 305 563 (62.3) |

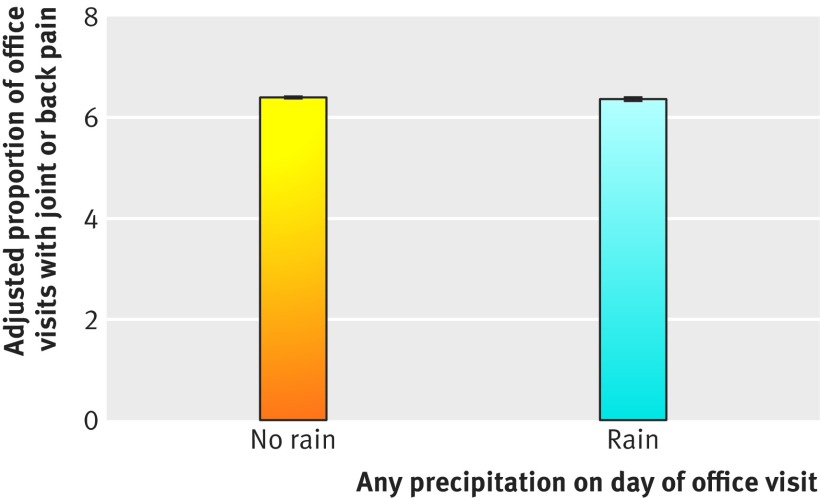

In unadjusted and adjusted analyses, there was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients with diagnoses for joint or back pain between rainy days and non-rainy days (unadjusted: 130 586/2 095 761, or 6.23% (95% confidence interval 6.20% to 6.26%) v 614 786/9 577 631, or 6.42% (6.40% to 6.43%), P<0.001; adjusted: 6.35% (6.32% to 6.39%) v 6.39% (6.38% to 6.40%), P=0.05, adjusted difference 0.04% (95% confidence interval −0.07% to 0.001%)) (fig 1; also see supplementary eTable 2 for full model results). The differences were in the opposite anticipated direction, however, and were so small that they are unlikely to be clinically meaningful. We found no statistically significant relation when daily rainfall was modeled as a continuous measure (a 1 mm increase in rainfall corresponded to a 0.318% (95% confidence interval −1.55% to 1.63%) increase in outpatient visits for joint pain per 1 million patients, P=0.95).

Fig 1.

Adjusted proportion of patients with a diagnosis of joint or back pain between rainy and non-rainy days. Error bars around estimates are 95% confidence intervals

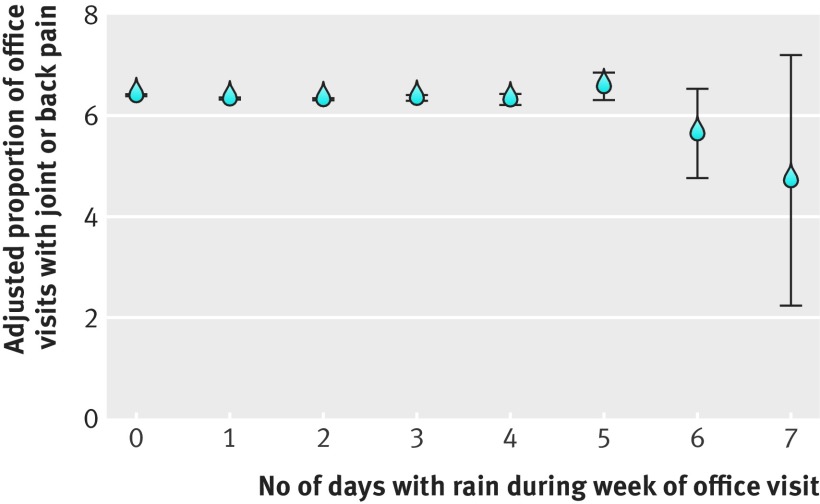

We also found no relation between the proportion of claims for joint or back pain and the number of rainy days in the week of the outpatient visit (fig 2). For example, joint or back pain rates during weeks with seven rainy days were similar to weeks with zero rainy days (P=0.18). There was also no statistically significant relation between the proportion of visits that involved joint or back pain in any given week and weekly rainfall (modeled as a continuous measure) during that week or the preceding week.

Fig 2.

Adjusted proportion of patients with a diagnosis of joint or back pain by number of rainy days during week of outpatient visit. Error bars around estimates are 95% confidence intervals

In subgroup analyses we found no differences between precipitation and joint or back pain and geographic regions, age groups, race, or patients with versus without rheumatoid arthritis (table 2). When analyses were restricted to patients’ first visit only, we found no adjusted differences in the proportion of outpatient visits with joint or back pain between rainy versus non-rainy days (6.14%, (95% confidence interval 6.06% to 6.22%) v 6.15% (6.13% to 6.17%)).

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of joint and back pain according to precipitation on day of outpatient visit

| Subgroups | Adjusted proportion of outpatient visits with a diagnosis of joint or back pain | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No rain (%) | Rain (%) | Difference (95% CI) | |

| Region: | |||

| North east (n=1 884 752) | 6.44 | 6.40 | −0.04 (−0.12 to 0.04) |

| Midwest (n=2 297 189) | 6.16 | 6.16 | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.1) |

| South (n=5 008 055) | 6.32 | 6.32 | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.1) |

| West (n=2 483 396) | 6.72 | 6.47 | −0.2 (−0.4 to −0.1) |

| Age (years): | |||

| 65-74 (n=4 874 112) | 6.39 | 6.34 | −0.04 (0.00 to 0.00) |

| 75-84 (n=4 619 117) | 6.47 | 6.42 | −0.05 (0.00 to 0.00) |

| ≥85 (n=2 180 163) | 6.24 | 6.24 | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) |

| Race: | |||

| White (n=10 042 348) | 6.30 | 6.27 | −0.03 (−0.08 to 0.01) |

| Black (n=891 652) | 6.98 | 6.84 | −0.14 (−0.31 to 0.02) |

| Asian (n=295 834) | 6.85 | 6.86 | 0.01 (−0.39 to 0.41) |

| Hispanic (n=223 806) | 7.30 | 7.34 | 0.03 (−0.32 to 0.38) |

| Other (n=219 752) | 6.51 | 6.56 | 0.05 (−0.25 to 0.36) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis: | |||

| Yes | 8.15 | 8.04 | −0.11 (−0.16 to −0.05) |

| No | 3.42 | 3.50 | 0.08 (0.01 to 0.14) |

Discussion

In an analysis of millions of outpatient visits of older Americans (age ≥65 years) during 2008-12, including those with rheumatoid arthritis, the proportion of joint or back pain related visits was not associated with rainfall on the day of the appointment or with the amount of rainfall during that week or the preceding week.

Previous studies of this association between joint or back pain and rainfall have benefited from detailed measurements of pain severity but have been limited by small sample sizes and, equally important, problems of recall and confirmation bias in surveys.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Indeed, one study suggested that the persistence of this belief may reflect the tendency of people to perceive patterns where none exist.11 Although our findings may be consistent with this interpretation, our “big data” approach lacked the clinical detail to definitively characterize severity of joint or back pain symptoms. Instead, we assumed that if symptoms were substantial they might prompt at least a small (but statistically identifiable) increase in the likelihood that patients would report these symptoms to their physician and that physicians would in turn bill Medicare for having addressed joint or back pain problems.

Limitations of this study

Our study has limitations. Most importantly, we lacked detail on disease severity to definitively exclude higher rates of joint or back pain related to rainfall. Moreover, although we had detailed data on utilization of primary care, we lacked information on use of drugs during periods of pain exacerbation; patients could self manage symptoms by taking over-the-counter analgesics, which would not be detectable in our data. We also relied on administrative data, which is primarily focused on conditions rather than symptoms, which means that patients with joint or back pain related conditions (eg, osteoarthritis) who were seen by their physician for an unrelated symptom (eg, shortness of breath) may have administrative diagnosis codes for both conditions. Our approach, however, assumed that a small but statistically identifiable relative increase in joint or back pain may still occur during rainy versus non-rainy days. Finally, we focused on older patients and studied rainfall specifically, rather than other weather conditions such as humidity, barometric pressure, or temperature.

Conclusion

In a large analysis of older Americans insured by Medicare, we found no relation between rainfall and outpatient visits for joint or back pain related problems. An association may still exist, and larger, more detailed data on disease severity and pain would be useful to support the validity of this commonly held belief.

What is already known on this topic

Many people believe that changes in weather conditions—including increases in humidity, rainfall, or barometric pressure—worsen symptoms of joint or back pain, particularly among those with arthritis

Several studies exploring the relation between weather patterns and joint pain have reached mixed conclusions

Although studies have explored a variety of weather conditions and used detailed measures of joint pain, these have been survey based and included small numbers of patients

What this study adds

Data on millions of outpatient visits of older Americans linked to data on daily rainfall showed no relation between rainfall and outpatient visits for joint or back pain

This was the case both among the older overall population and among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in particular

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: eTables 1 and 2

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design and conduct of the study, data collection and management, analysis interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. ABJ supervised the study and is the guarantor. The research conducted was independent of any involvement from the sponsors of the study. Study sponsors were not involved in study design, data interpretation, writing, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Funding: No funding.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: support provided by grants from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (ABJ, NIH early independence award, grant 1DP5OD017897-01) and National Institute on Aging (NM and DM, grant R01AG053350); no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The guarantor (ABJ) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies are disclosed.

References

- 1. Smedslund G, Mowinckel P, Heiberg T, Kvien TK, Hagen KB. Does the weather really matter? A cohort study of influences of weather and solar conditions on daily variations of joint pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1243-7. 10.1002/art.24729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Timmermans EJ, Schaap LA, Herbolsheimer F, et al. EPOSA Research Group The Influence of Weather Conditions on Joint Pain in Older People with Osteoarthritis: Results from the European Project on OSteoArthritis. J Rheumatol 2015;42:1885-92. 10.3899/jrheum.141594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beilken K, Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Li Q, Steffens D. Acute Low Back Pain? Do Not Blame the Weather-A Case-Crossover Study. Pain Med 2017;18:1139-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Duong V, Maher CG, Steffens D, Li Q, Hancock MJ. Does weather affect daily pain intensity levels in patients with acute low back pain? A prospective cohort study. Rheumatol Int 2016;36:679-84. 10.1007/s00296-015-3419-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steffens D, Maher CG, Li Q, et al. Effect of weather on back pain: results from a case-crossover study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1867-72. 10.1002/acr.22378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dorleijn DM, Luijsterburg PA, Burdorf A, et al. Associations between weather conditions and clinical symptoms in patients with hip osteoarthritis: a 2-year cohort study. Pain 2014;155:808-13. 10.1016/j.pain.2014.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abasolo L, Tobías A, Leon L, et al. Weather conditions may worsen symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis patients: the possible effect of temperature. Reumatol Clin 2013;9:226-8. 10.1016/j.reuma.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smedslund G, Hagen KB. Does rain really cause pain? A systematic review of the associations between weather factors and severity of pain in people with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Pain 2011;15:5-10. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McAlindon T, Formica M, Schmid CH, Fletcher J. Changes in barometric pressure and ambient temperature influence osteoarthritis pain. Am J Med 2007;120:429-34. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Drane D, Berry G, Bieri D, McFarlane AC, Brooks P. The association between external weather conditions and pain and stiffness in women with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1997;24:1309-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Redelmeier DA, Tversky A. On the belief that arthritis pain is related to the weather. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:2895-6. 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Menne MJ, Durre I, Vose RS, Gleason BE, Houston TG. An Overview of the Global Historical Climatology Network-Daily Database. J Atmos Ocean Technol 2012;29:897-910 10.1175/JTECH-D-11-00103.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Madestam A, Shoag D, Veuger S, Yanagizawa-Drott D. Do Political Protests Matter? Evidence from the Tea Party Movement*. Q J Econ 2013;128:1633-85 10.1093/qje/qjt021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: eTables 1 and 2