Abstract

G-protein coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) are serine/threonine kinases that regulate a large and diverse class of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). Through GRK phosphorylation and β-arrestin recruitment GPCRs are desensitized and their signal terminated. Recent work on these kinases has expanded their role from canonical GPCR regulation to include non-canonical regulation of non-GPCR and non-receptor substrates through phosphorylation as well as via scaffolding functions. Due to these and other regulatory roles, GRKs have been shown to play a critical role in the outcome of a variety of physiological and pathophysiological processes including chemotaxis, signaling, migration, inflammatory gene expression, etc. This diverse set of functions for these proteins makes them popular targets for therapeutics. Role for these kinases in inflammation and inflammatory disease is an evolving area of research currently pursued in many laboratories. In this review, we describe the current state of knowledge on various GRKs pertaining to their role in inflammation and inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Inflammation, G-protein coupled receptor kinases, GRK, G-protein coupled receptor, beta-adrenergic receptor kinase

Introduction

Cells have remarkable ability to adapt and respond to changes in their environment through recognition of extracellular signals from both the host as well as invading pathogens. These signals come in a variety of forms, not only from the host environment (eg. hormones, cytokines, and chemokines) but also from microbial substances such as lipopolysaccharides and the breakdown of products from diet. Cells have developed sophisticated mechanisms for detecting and responding to these signals, largely through development of both extracellular and intracellular receptors. Despite the abundance of various receptor classes, G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent one of the largest proportion of receptors. This family of receptors is encoded by approximately 950 genes and transmits responses to a wide variety of stimuli including odorants, hormones, neurotransmitters, light, extracellular calcium, and many other stimuli regulating a wide variety of biological processes (Takeda, Kadowaki, Haga, Takaesu, & Mitaku, 2002). These receptors are characterized by their seven transmembrane domains that, when active, undergo a conformational change allowing them to activate nearby heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins (G-proteins). These G-proteins bind to nucleotides guanosine triphosphate (GTP) or guanosine diphosphate (GDP) and form a complex composed of α-subunits (Gα encoded by 16 genes) and βγ dimers (Gβ encoded by 5 genes and Gγ encoded by 12 genes). When active, GPCRs can serve as guanyl nucleotide exchange factors for these G-proteins, catalyzing the release of the bound GDP and exchanging it for GTP, which in turn causes the dissociation of the heterotrimeric G protein subunits Gα and Gβγ (Cabrera-Vera et al., 2003). These dissociated G-proteins then interact with other effector proteins and secondary messengers to facilitate a large variety of biological outcomes. This activity is terminated when the intrinsic GTPase activity of the Gα subunit causes GTP hydrolysis and the formation Gα-GDP, leading to its re-association with Gβγ and the re-formation of the heterotrimeric G-protein complex. For a comprehensive review of G-protein activation and regulation please see other excellent reviews (Hewavitharana & Wedegaertner, 2012; Oldham & Hamm, 2008; Preininger & Hamm, 2004; Ritter & Hall, 2009).

Aside from the intrinsic GTPase activity, G-protein mediated signaling is most often terminated by a conserved two-step mechanism: receptor phosphorylation by G-protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) followed by arrestin recruitment and binding to the activated receptor, ultimately leading to internalization and termination of the GPCR signal. Four genes encode arrestins; arrestin-1 and arrestin-4 that are restricted to the retina, whereas arrestin-2 (β-arrestin-1) and arrestin-3 (β-arrestin-2) are ubiquitously expressed throughout the body (Lefkowitz & Shenoy, 2005). This process of receptor desensitization is responsible for decreasing the magnitude of stimulation that GPCRs exhibit in response to prolonged exposure to agonist binding. This process is initiated by various GRKs that phosphorylate the intracellular loops and/or the C-terminal domain of activated GPCRs. This phosphorylation directly leads to the recruitment of multifunctional adaptor proteins, arrestins. Interestingly, some receptors are regulated by a single GRK whereas other receptors can be regulated by multiple GRKs with varying affinities. Recently it has been suggested that there are distinct phosphorylation patterns termed “barcodes” that determine β-arrestin functionality and contribute to the diverse responses witnessed in GPCR activity after phosphorylation (Nobles et al., 2011). This phosphorylation and subsequent binding of arrestins prevent further activation of G-proteins resulting in the cessation of G-protein signaling despite continued presence of the agonist. Furthermore, GRK-arrestin interaction leads to internalization of the activated GPCR from the cellular surface through formation of clathrin-coated pits. During this internalization, signaling can still occur through the binding of additional signaling proteins to the still attached arrestin proteins where they may serve as scaffolding proteins. This converts the GPCR activation from heterotrimeric G-protein signaling pathway to G-protein-independent pathway (Lefkowitz, 2013). Recently, it was shown that the interaction between β-arrestins and GPCRs form distinct conformational complexes and that these complexes are specialized to carry out different cellular functions depending on the relationship of their binding (Cahill et al., 2017). Moreover, it has been shown that G-protein signaling can be sustained within the endosome through the formation of “megaplexes” indicating a possible new signaling role for these receptors during internalization (Thomsen et al., 2016). These alternative G-protein-independent pathways are addressed in other reviews (V. V Gurevich & Gurevich, 2004; Lefkowitz & Shenoy, 2005; Luttrell, 2005). Because of the wide array of biological stimuli and functionality, regulation and control of these receptors and their subsequent signaling is a potential target for pharmaceutical intervention. In fact, the GPCR family of receptors represent the largest family of drug targets for a wide variety of conditions including cardiovascular, metabolic, neurodegenerative, infectious, and oncologic diseases (Howard et al., 2001; Thompson, Burnham, & Cole, 2005).

As studies on the regulation of GPCRs continues to unfold, new roles for GRKs have been emerging in addition to the part they play in GPCR phosphorylation. It is now apparent that GRKs (and arrestins) regulate GPCR-independent functions in cell signaling and biology. This non-canonical role for GRKs has been shown to have critical regulatory roles in the context of inflammation and inflammatory diseases. In this review, we will discuss these known and emerging roles of GRKs in both GPCR-dependent and independent functions in the context of inflammatory processes and pathologies.

GRK Structure and Families

The association between G proteins and receptor-mediated signal transduction developed through a progression of breakthroughs. Initially, it was discovered that GTP was necessary for signal transduction upon receptor activation. When the proteins were characterized for their interaction with GTP to initiate the signaling cascade they were termed “G-proteins” (Rodbell, Krans, Pohl, & Birnbaumer, 1971; Ross & Gilman, 1977). Our understanding of the regulation of GPCRs then progressed through the identification of rhodopsin phosphorylation and that this phosphorylation contributed to the rapid desensitization of rhodopsin signaling. This desensitization was attributed to the “opsin kinase” now known as GRK1 (Bownds, Dawes, Miller, & Stahlman, 1972). It was later in the mid-1980’s through the cloning of the β-adrenergic receptor kinase (now named GRK2) that it was demonstrated that GRK1 was, in fact, a member of a family of related kinases that have a common mechanism that can recognize and regulate the active state of a variety of GPCRs (Benovic, Deblasi, Stone, Caron, & Lefkowitz, 1989). During this period, another protein was discovered to have a regulatory impact and could dampen G-protein mediated retinal signaling by also associating with rhodopsin. This protein (termed S antigen because of its role in allergic uveitis) was then renamed “arrestin” because of its ‘arresting’ function in retinal signaling (Wacker, Donoso, Kalsow, Yankeelov, & Organisciak, 1977; Wilden, Hall, & Kühn, 1986; Zuckerman & Cheasty, 1986). It was through further characterization of the relationship between GRKs and arrestins that the canonical two-step inactivation process of desensitization of GPCRs was established. As studies progressed, the family of GRKs expanded to include seven serine/threonine kinases including GRK3 (Benovic et al., 1991), GRK4 (Ambrose et al., 1992), GRK5 (Kunapuli & Benovic, 1993; R T Premont et al., 1996), GRK6 (Benovic & Gomez, 1993) and GRK7 (Hisatomi et al., 1998; Weiss et al., 1998). These kinases are now grouped based on their sequence similarities and are broken down into three subfamilies: GRK1, composed of GRK1 (rhodopsin kinase) and GRK7 (cone opsin kinase); GRK2, including GRK2 and GRK3; and GRK4, made up of GRK4, GRK5, and GRK6.

Evolutionarily, GRKs are present in most vertebrate and invertebrate species as well as identified in non-metazoan species, with the kinase domain being the most evolutionarily conserved among the different GRKs (Mushegian, Gurevich, & Gurevich, 2012). All seven GRK members are ~500–700 amino acids long, multi-domain proteins containing a family specific N-terminal domain, followed by a regulator of G protein signaling homology domain (RH domain), an AGC protein kinase domain and a C-terminal domain (Siderovski, Hessel, Chung, Mak, & Tyers, 1996). The C-terminal is variable (both in length and structure) among the different subfamilies and contains structural elements that are partly responsible for the diversity of GRK function, regulation, and interaction. Specifically, members of the GRK1 family have C-terminal prenylation sites while GRK2 subfamily members have a pleckstrin homology domain in their C-termini, that can interact with Gβγ subunits (Touhara, Inglese, Pitcher, Shaw, & Lefkowitz, 1994). The GRK4 family members have palmitoylation sites with the exception of GRK5 that contains a positively charged lipid-binding amphipathic helix in its C-terminus (Richard T Premont et al., 1999). GRK5 is also slightly different than its family members due to the presence of a nuclear localization signal that allows it to accumulate in the nucleus where it can act as a histone deacetylase kinase (although it is predominantly cytoplasmic) (Martini et al., 2008). Structurally, GRK1 and GRK7 genes (in humans) contain 4 exons, GRK2 and GRK3 contain 21 exons, and members of GRK4 subfamily have 16 exons. Tissue localization of these kinases varies significantly between subfamilies. GRK1 and GRK7 are termed the “visual kinases” and are localized in the eyes, whereas the non-visual kinases are distributed nearly ubiquitously throughout the body albeit at different expression levels. This distribution holds true for all non-visual GRKs with the exception of GRK4 that is restricted to the testis, the proximal tubule of the kidney, and the cerebellum (Inglese, Freedman, Koch, & Lefkowitz, 1993). Although it was originally believed that all GRKs can phosphorylate GPCRs equally, recent studies have shown that the GRK2/3 and the GRK5/6 subfamilies differ in their ability to phosphorylate inactive GPCRs; GRK5/6 can phosphorylate GPCRs in both the active and inactive conformations (L. Li et al., 2015). Since GPCR superfamily represents the largest class of receptors and there are only four GRKs ubiquitously expressed throughout the body, each GRK must be able to phosphorylate and regulate a wide variety of receptors, thus increasing the importance as well as the complexity of their role in signal transduction.

GRK Regulation

GRKs play a vital role in the regulation and behavior of many biological processes through a variety of regulatory mechanisms. It is perhaps due to this variety of functions and interactions that they are so heavily conserved evolutionarily. One of the first proteins that were shown to interact with and activate these GRKs was the Gβγ-subunits (DebBurman, Ptasienski, Benovic, & Hosey, 1996). In addition to G-protein activation of GRKs, lipids also have the ability to regulate GRKs. Furthermore, other protein such as calmodulin, caveolin-1, ERK and actin can also modulate GRK activity through direct binding (Christopher V Carman, Lisanti, & Benovic, 1999; Chuang, Paolucci, & De Blasi, 1996). Interestingly, these methods of regulation are not conserved among the various subfamilies of GRKs. For example, GRK2 family members are activated by phospholipids (phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate) through its interaction with the PH domain in the C-terminus, whereas GRK4-like members are activated by phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate through its binding to the N-terminal polybasic region (Pitcher et al., 1996).

Phosphorylation has differing regulatory effects (either activation or deactivation) on GRKs depending on exactly which kinase interacts with a given GRK or whether GRK undergoes autophosphorylation. To illustrate this contrasting regulation in the case of the visual GRKs, phosphorylation by protein kinase-A or for GRK5 by protein kinase-C causes a decrease in kinase activity (Horner, Osawa, Schaller, & Weiss, 2005; Pronin & Benovic, 1997). In contrast, phosphorylation of GRK2 by protein kinase-C enhances its activity (Chuang, LeVine, & De Blasi, 1995). Interestingly, where GRK2 and GRK5 can be phosphorylated by multiple kinases, there is very little evidence of phosphorylation of GRK3, GRK4 or GRK6. In addition to phosphorylation, other post-translational modifications such as S-nitrosylation of GRK2 by nitric oxide synthase, has been shown to inhibit its activity (Whalen et al., 2007). These contrasting effects highlight that there are GRK specific regulation and suggests that there are multiple pathways involved in fine tuning each GRK’s response and ability to regulate GPCRs, non-GPCRs, and non-receptor biological functions. GRKs similar to other protein families that interact with GPCRs engage an inter-helical cavity that opens on the cytoplasmic side of the GPCR after activation (Farrens, Altenbach, Yang, Hubbell, & Khorana, 1996) and it is probable that GRKs interact in a similar fashion to discern active versus inactive receptors (Homan & Tesmer, 2014). In recent studies, the crystal structures for various GRKs including GRK1, GRK2 and GRK6 have been characterized and it was observed that the conserved 18–20 amino acids on the N-terminal become helical and form an α-helix stabilizing the closed (active) conformation, allowing it to interact with both lobes of the kinase domain (Boguth, Singh, Huang, & Tesmer, 2010). This suggests then, that GPCR binding helps to promote GRK activity by helping to align catalytic residues of the kinase domain indicating that GPCRs can serve as both the substrate and the allosteric activators (C. Y. Chen, Dion, Kim, & Benovic, 1993; Palczewski, Buczyłko, Kaplan, Polans, & Crabb, 1991). Furthermore, the mutation of this N-terminus α-helix abolishes GPCR phosphorylation suggesting that this helix formation is indeed the primary step in the activation of GRKs by GPCRs (Pao, Barker, & Benovic, 2009). This mechanism sets apart GRKs from other kinases that phosphorylate accessible residues (Ser, Thr, Tyr) that are in a specific sequence-context. Instead, GRK phosphorylation of Ser and Thr residues are not strongly sequence-context-specific and this context-independence may help to explain the versatility and flexibility of seven GRKs to regulate hundreds of different GPCRs (Vishnivetskiy et al., 1999). The allosteric binding of GRKs to GPCRs essentially ensures that GRKs, when bound, will phosphorylate nearby proteins with accessible loops, i.e. the intracellular loops and tails of the receptor molecules that they are currently bound to.

In the early years of their discovery, this phosphorylation of GPCRs was believed to be the only function of GRKs. With the identification of non-receptor substrates, however, it has been shown that these non-receptor substrates can be phosphorylated more efficiently than peptides derived from cognate GPCRs (E. V Gurevich, Tesmer, Mushegian, & Gurevich, 2012). This suggests that there must be alternative mechanisms of activation other than binding to GPCRs but these mechanisms remain to be identified. One hypothesis on non-GPCR activation of GRKs stems from the idea that any physiochemical environment that resembles the binding pocket found on GPCRs could favor GRK activation.

Animal Models of GRK Deficiency

Studies using knockout and transgenic mice as well as using viral-mediated overexpression models have enabled researchers to identify various pathophysiological roles for GRKs. However, mice lacking these GRKs oftentimes appear to function normally without the addition of a stressor. As indicated before, GRKs also have dual functionality in various tissues by both suppressing G-protein signaling as well as promoting signaling independent of G-proteins. Because of this loss of regulation by any given GRK, knockouts can have differing effects that can either a) allow enhanced or unregulated receptor signaling because of loss of desensitization or b) alter the signaling cascade by preventing the switch from G protein signaling to non-G protein pathways or c) alter the functionality of biological processes in a receptor-independent fashion (Richard T Premont & Gainetdinov, 2007). It is also possible that certain phenotypes are not exhibited due to compensation and overlapping roles of other GRKs present in the animal. For animals that do have abnormal functionality, the most notable phenotype was in the GRK2 homozygous knockout animal that was embryonic lethal because of defective cardiac development (Jaber et al., 1996). Interestingly, recent work has shown that this lethality, in fact, stems from a role of GRK2 in embryogenesis rather than a specific role in cardiac development; mice with cardiac myocyte-specific GRK2 ablation develop normally (Matkovich et al., 2006). Intrigued by the extreme phenotype, GRK2 heterozygous mice were heavily studied and GRK2 was shown to be important for heart development, lymphocyte chemotaxis, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, sepsis, atherosclerosis and others, making GRK2 one of the most widely researched of all the GRKs. Studies focusing on the other GRK knockout and over-expression animals have shown an important role in several distinct phenotypes including GRK3 in olfaction (Peppel et al., 1997); GRK5 in cholinergic responses and inflammation; GRK6 in chemotaxis, behavioral responses, locomotor-stimulating effect of cocaine and others (Raul R Gainetdinov et al., 2003). Interestingly, recent studies crossing heterozygous GRK5 and heterozygous GRK6 knockout mice in order to generate GRK5/GRK6 double knockout mice was found to be embryonic lethal, though the mechanism is unknown (Burkhalter, Fralish, Premont, Caron, & Philipp, 2013). A detailed summary of all the phenotypes is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

| GRK | Genotype | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRK1 | GRK1 KO | Photon responses are increased and longer-lasting, loss of phosphorylation of rhodopsin. | (C. K. Chen et al., 1999) |

| GRK1 Overexpression | Increased damage to photoreceptors after intense light | (Whitcomb et al., 2010) | |

| GRK2 | Homozygous KO (whole body) | Homozygous KO is embryonic lethal | (Jaber et al., 1996) |

| Heterozygous KO (whole body) | Susceptible to β-Arrestin stimulation; altered progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis through increased infiltration of CNS by lymphocytes and macrophages; increase in lymphocyte chemotaxis toward CCL4 | (Matkovich et al., 2006; Vroon et al., 2005; Vroon, Heijnen, Lombardi, et al., 2004) | |

| Cardiac Specific KO | Enhanced ionotropic sensitivity to isoproterenol; lusitropic, tachyphylaxis | (Matkovich et al., 2006) | |

| Cardiac Specific OE | Decreased β-arrestin signaling; attenuated ventricular contractility | (Koch et al., 1995) | |

| Cardiac Specific β-ARKct | Enhanced contractility | (Koch et al., 1995) | |

| Cardiac Specific β-ARKnt | Cardiac hypertrophy, enhanced β-AR density and signaling | (Keys et al., 2003) | |

| GRK2-C340S | Loss of nitrosylation-mediated cardioprotection from postischemic injury | (Huang et al., 2013) | |

| Myeloid Specific KO | Increased Inflammation in endotoxemia and polymicrobial sepsis; decreased atherosclerotic lesions in LDL-myeloid dual KO mice | (Otten et al., 2013; Parvataneni et al., 2011; Patial, Saini, et al., 2011a) | |

| Vascular Smooth Muscle OE | βAR signal attenuation; attenuation of isoproterenol induced vasodilation; elevation of resting mean blood pressure; hypertrophy | (Eckhart et al., 2002) | |

| Adrenal-specific KO | Attenuates heart failure progression and improves function postmyocardial infarction | (Lymperopoulos et al., 2010) | |

| GRK3 | GRK3 KO | Enhanced sensitivity to olfactory stimuli; altered M2 muscarinic airway regulation; loss of neuropathic pain induced opioid tolerance | (Lodowski et al., 2003; Peppel et al., 1997; Walker et al., 1999) |

| Cardiac Specific OE | Normal β-AR signaling and hemodynamic function; decreased MAPK activity to thrombin | (Iaccarino, Rockman, Shotwell, Tomhave, & Koch, 1998) | |

| Cardiac Specific GRK3ct | Hypertension; α-1 receptor hypersensitivity | (Vinge et al., 2008) | |

| GRK4 | GRK4 KO | No differences detected in fertility or sperm function | (Virlon et al., 1998) |

| GRK4-γA142V | Hypertension, altered dopamine signaling | (Felder et al., 2002; Z. Wang et al., 2007) | |

| GRK5 | GRK5 KO | Muscarinic M2 supersensitivity and impaired desensitization; decreased LPS-induced neutrophil infiltration in lung; decreased cytokine chemokine levels; enhanced hypothermia, hypoactivity, tremor and salivation by oxotremorine; decreased NFκB activation in thioglycollate-induced peritoneal macrophages and cardiomyocytes; increased NFκB in endothelial cells; increased apoptotic response to genotoxic damage; decreased thymocyte apoptosis during sepsis | (X. Chen et al., 2010; R R Gainetdinov et al., 1999; Islam et al., 2013; Nandakumar Packiriswamy et al., 2013; Patial, Saini, et al., 2011a; Rockman et al., 1996; Daniela Sorriento et al., 2008) |

| Cardiac Specific OE | Increased β-adrenergic receptor desensitization attenuating contractility and heart rate | (Rockman et al., 1996) | |

| Cardiac Specific KO | Cardioprotection posttransaortic constrtiction | (R R Gainetdinov et al., 1999; Gold, Gao, Shang, Premont, & Koch, 2012) | |

| Vascular smooth muscle OE | VSM-specific OE of GRK5 increases blood pressure through β1AR and Ang II receptors | (Keys et al., 2003) | |

| GRK6 | GRK6 KO | Altered desensitization of D2-like dopamine receptors and supersensitivity to psychostimulants; deficient lymphocyte chemotaxis; increased acute inflammation and neutrophil chemotaxis | (Fong et al., 2002; Raul R Gainetdinov et al., 2003; Kavelaars et al., 2003; Vroon, Heijnen, Raatgever, et al., 2004) |

| GRK5/6 | Double KO | Embryonic Lethal | (Burkhalter et al., 2013) |

Research on the various GRKs ranging from the biochemical and molecular machinations and functionality to the whole body knockout phenotypes demonstrates a unique and essential role for this family of proteins in physiology. However, the role that these GRKs play in specific inflammatory responses is only beginning to be revealed. This review will focus mainly on our recent understanding of the roles that GRKs play in the immune system, specifically their influence on inflammatory signaling pathways and in inflammatory diseases.

GRKs in Inflammatory Signaling and Disease

GRK1 Subfamily

Biochemistry

The GRK1 subfamily is comprised of the retinal GRKs, GRK1 (rhodopsin kinase) and GRK7 (cone opsin kinase). These kinases are expressed in the retina of vertebrates but the expression pattern within the retinal cells is species dependent, where both GRKs are not always present. Highlighting these differences is the fact that all rod cells in vertebrates express GRK1 but cone cells express either GRK1, GRK7 or both, depending on the species (Osawa & Weiss, 2012). GRK1 and GRK7 share their major domains and sequence homology but much of the current work on this family has been done on GRK1; first, because GRK1 was discovered decades before GRK7 and second, because of the demonstration of the X-ray structure of GRK1. Functionally, after activation of rhodopsin by light, GRK1 facilitates desensitization by phosphorylating rhodopsin on Ser/Thr residues in the C-terminal domain, which facilitates arrestin recruitment and binding. In order to accomplish this, GRK1 and GRK7 must be properly localized to the membrane, and these GRKs are post-translationally modified to ensure their proper localization within the cell. GRK1 differs from GRK7 in this regard in that GRK1 is post-translationally modified via farnesylation and blocking this markedly limits its ability to phosphorylate active rhodopsin (Inglese, Koch, Caron, & Lefkowitz, 1992). In contrast, GRK7 is predicted to have a geranylgeranyl modification site on its C-terminus rather than the N-terminus like GRK1. These modifications are believed to serve as hydrophobic anchors that secure GRK1 and GRK7 to the cellular membranes (Inglese et al., 1992) and allow for these kinases to “probe” for activated receptors in a two-dimensional rather than three-dimensional search which is essential for rapid signal termination.

Role of GRK1 and GRK7 in Inflammation

Due to the limited tissue expression of GRK1 and GRK7, little is known about the role they play in inflammatory conditions of the retina. They do play a critical role in photoreceptors cells and GRK1 null-mice show shorter outer segments and undergo apoptosis if exposed to constant dim light (C. K. Chen et al., 1999). Over-activation of these GRKs can be detrimental to photoreceptor health as well and hyper-phosphorylation of rhodopsin caused by GRK1 mutations can cause a retinal degenerative disease known as retinal pigmentosa (Shi et al., 2005). GRK1 levels are regulated in rat diabetic models in Brown Norway and Sprague-Dawley after 12 weeks but were unaffected in the Long Evans models (Y. H. Kim et al., 2005). What these altered levels mean in terms of GRK function and if they play a role in diseases such as diabetic retinopathy or other inflammatory conditions remain unknown. Despite their limited role in inflammation it is important to think of how other therapeutics can influence these GRKs as a side effect of other treatments. For example, HSP90 inhibitors are being developed for oncology, retinal pigmentosa, inherited retinal degeneration and other neurodegenerative diseases. But HSP90 is critical for the sustained production of GRK1. Treatments that include inhibition of HSP90 for sustained periods of time run this risk of adversely affecting visual function similar to Oguchi’s Disease (stationary night blindness), a disease that results from genetic mutations and low expression of GRK1 (C. K. Chen et al., 1999).

GRK2 Subfamily

Biochemistry

The GRK2 subfamily is comprised of two GRKs, GRK2 and GRK3. These proteins are found ubiquitously throughout the body but show some variability in their localization and expression in different tissues and cell types. One of the fundamental differences that are unique to this subfamily is that their ability to phosphorylate GPCRs is restricted to GPCRs that are actively bound to a ligand (L. Li et al., 2015). Furthermore, the RGS homology domain (RH) in the N-terminus region of GRK2 family members are able to bind to Gαq and Gα11, inhibiting their downstream signaling capabilities (C V Carman et al., 1999). Interestingly neither GRK2 nor GRK3 is able to interact with Gαs, Gαi, Gαo, or Gα12/13, indicating that this functional interaction is specific to those two G-proteins (C V Carman et al., 1999; Day, Carman, Sterne-Marr, Benovic, & Wedegaertner, 2003; Sallese, Mariggiò, D’Urbano, Iacovelli, & De Blasi, 2000). Their RH domain consists of nine α-helices that are analogous to other RGS domains and two additional α-helices derived from a region between the kinase and PH domain. This allows for the RH domain to interact with the PH domain indicating a possible role for regulation of the kinase activity of this subfamily. In addition to the unique binding capabilities of this subfamilies’ RH domain, GRK2, and GRK3 contain a pleckstrin homology domain (PH domain) in the C-terminus region that is unique to only these two GRKs. The PH domain consists of seven β-strands and one C-terminal α-helix. This PH domain has the functional capability to bind to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) as well as the Gβγ subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein. This binding to the Gβγ subunit is particularly important for cytoplasmic localization of this subfamily and the subsequent phosphorylation of activated GPCRs. It is believed that through the binding of GRK2 and GRK3 to Gβγ these GRKs can be shuttled to the activated GPCRs and is a potential mechanism for how GRK2 and GRK3 recognize active receptors (Benovic et al., 1989). Another consequence of interaction of Gβγ to GRK2 and GRK3 is that this high-affinity binding can sequester and interfere with downstream targets of Gβγ in a similar manner to Gαq. With the discovery of GRK2’s crystal structure in complex with Gβγ, we have been able to gain new insights into the regulation of GRK2 (and potentially GRK3). This structure places the three distinct domains at the vertices of a triangle and gives insight on how these proteins with multiple modular domains can act as an integrated signaling molecule (Lodowski, Pitcher, Capel, Lefkowitz, & Tesmer, 2003). Interestingly, GRK2 and GRK3 are the only isoforms that interact with the free Gβγ subunit and translocate to the membrane in this fashion. Lastly, presence of the PH domain in combination with the cytoplasmic localization of these GRKs may provide a mechanism for this subfamily to influence a large number of non-receptor substrates both in the presence and absence of GPCR ligand activity.

Role of GRK2 in Inflammation

GRK2 is ubiquitously expressed and primarily located in the cytosol. While most studies have looked at GRK2’s ability to phosphorylate β-adrenergic and angiotensin II type 1 receptors, GRK2 has the capability to interact with a variety of GPCRs (C V Carman et al., 1999). GRK2 has also been shown to phosphorylate other non-GPCR receptors including the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β, epithelial Na+ channel, and the downstream regulatory element antagonist modulator (DREAM) (E. V Gurevich et al., 2012). It has also been suggested that GRK2 and GRK3 are more efficient at clathrin-mediated endocytosis than GRK5 and GRK6 (Ren et al., 2005). Outside of its role in phosphorylating and regulating GPCR functions, GRK2 has the ability to phosphorylate and/or interact with a large variety of cellular proteins in both tissue– and context-specific fashion. Because of its ability to regulate cellular processes in both canonical and non-canonical fashions, GRK2 has significant influence on a multitude of vital physiological functions including its role in inflammation and inflammatory diseases (N Packiriswamy & Parameswaran, 2015).

Among the inflammatory pathways, research from our lab and others have shown that GRKs are important regulators of NFκB signaling pathway. NFκB is a critical player in the regulation of expression of many inflammatory genes and therefore is a target for therapeutic manipulation in several inflammatory diseases. Under un-stimulated conditions, NFκB transcription factors (p65 (RelA), p50, RelB, cRel and p52) are sequestered in the cytoplasm by members of the IκB family of proteins (IκBα, IκBβ, IκBε, p105 (NFκB1) and p100 (NFκB2)). Upon stimulation, IκB is phosphorylated by the IκB kinase complex (IKK) and undergoes ubiquitination and degradation. This releases the sequestered NFκB transcription factors which then translocate to the nucleus and modulate gene transcription (reviewed in (Jobin & Sartor, 2000)). GRK2 and GRK5 most notably regulate this signaling pathway to influence the outcome of inflammation in immune and non-immune cell types. GRK2 has been shown to directly interact with proteins involved in this signaling pathway, IκBα, and p105. GRK2 is able to phosphorylate IκBα albeit at very low stoichiometry and able to modulate this pathway in response to TNFα in a macrophage cell line and in HEK293 cells (Patial, Luo, Porter, Benovic, & Parameswaran, 2009). This relationship between GRK2 and NFκB signaling was recently shown in neonatal rat cardiac fibroblasts in response to arginine vasopressin (AVP). AVP increased mRNA and protein levels of IL6 in these cells and pharmacological inhibition of GRK2 ablated this increase and NFκB activation, linking GRK2 and inflammation in cardiac stress (F. Xu et al., 2017). This biochemical regulation was also recently demonstrated in colon cancer epithelial cell line and this effect of GRK2 on IκBα was linked to its role in positively inducing some inflammatory genes in these cells (manuscript in revision). Interestingly, GRK2 has also been shown to interact with p105 and modulate ERK pathway downstream of p105 in primary macrophages. In this case, GRK2 was shown to be a negative regulator of this pathway and downstream inflammatory genes (Patial, Saini, et al., 2011a). Interestingly, Toll-like receptor ligands induce GRK2 expression in primary macrophages and neutrophils (J C Alves-Filho et al., 2009; Loniewski, Shi, Pestka, & Parameswaran, 2008). Additionally, GRK2 has also been shown to localize in the mitochondria after LPS stimulation and regulate the production of reactive oxygen species (D. Sorriento et al., 2013). Furthermore, immune cells from septic patients exhibit increased levels of GRK2 indicating a possible clinical link between GRK2 levels and the associated signaling pathways and inflammatory diseases (Arraes et al., 2006). This was shown to be the case at least in an animal model of sepsis where IL-33-mediated decrease in GRK2 expression was beneficial for neutrophil migration and therefore better clearance of bacteria and improvement in sepsis. Thus, GRK2 has been suggested as a possible target in sepsis pathogenesis (Jose C Alves-Filho et al., 2010).

Another common set of pathways activated in response to inflammatory stimuli are the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways (MAPKs). These kinases are a family of serine/threonine protein kinases that respond and react to extracellular signals. These reactions typically mediate a variety of fundamental biological processes ending in the translocation of transcription factors from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, in order to alter gene expression. These MAPK signaling cascades are generally broken down into three major groups: extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2 (ERK 1/2), p38 MAPK and Jun-N terminus kinase (JNK). These individual kinases are activated upstream by additional MAPKs, specifically: ERK is activated by MAPK kinase 1 (MKK1) and MKK2; p38 MAPK by MKK3, MKK4, and MKK6; and JNK by MKK4 and MKK7.

Like the NFκB pathway, GRK2 most notably regulates this family of signaling proteins in response to both GPCR ligands (i.e. CXCL8) and non-GPCR ligands (eg. TNFα). Because of the plethora of studies looking at the role of GRK2 in MAPK signaling in response to various GPCR ligands (Evron, Daigle, & Caron, 2012; Penela, Ribas, Aymerich, & Mayor, 2009) here, we focus primarily on the role of GRK2 in MAPK signaling in the context of inflammation. When these ligands activate the ERK1/2 pathway they can induce a wide variety of inflammatory mediators such as TNFα, interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-8, and prostaglandin E2. The effect of GRK2 on this pathway has been studied in a variety of contexts beginning with its role in macrophages where GRK2 was shown to negatively regulate LPS-induced ERK signaling(Patial, Saini, et al., 2011b). GRK2 has also been shown to bind to Raf1 and RhoA that can serve as a scaffolding protein for the ERK pathway enhancing its activation in response to EGF(Robinson & Pitcher, 2013). In a similar study GRK2 inhibition in cardiomyocytes increased ERK activity through interaction with the RAF MAPK axis (Fu, Koller, Abd Alla, & Quitterer, 2013). Another study focusing on the connection between the scaffolding ability of β-arrestin2 and GRKs found that in HEK cells overexpression of GRK2 completely mitigated the β-arrestin2 mediated increase in ERK1/2 activation (J. Kim et al., 2005). These effects held true with a variety of receptors including the β2-adrenergic receptor, cannabinoid receptor-2 (Franklin & Carrasco, 2013), angiotensin 1A receptor (Daniela Sorriento et al., 2008) and the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (Zheng et al., 2012). GRK2 also has the ability to regulate ERK signaling through direct association with MEK (MKK1) and increased levels of GRK2 inhibit ERK activation following chemokine induction (Jimenez-Sainz et al., 2006). Consistent with that, our lab also has recent data in colon epithelial cells that ERK1/2 activity is enhanced in GRK2 knockdown cells not through MKK1 regulation but rather through altering the levels of ROS produced in those cells (Manuscript in revision). Interestingly, GRK2 is able to regulate ERK in a variety of fashions; but ERK can also directly interact with and phosphorylate GRK2. Agonist-induced GRK2 phosphorylation by ERK1/2 reduces GRK2’s activation by Gβγ and its ability to phosphorylate receptors and marks it for degradation (Elorza, Sarnago, & Mayor, 2000; Pitcher et al., 1999).

The p38 MAPK pathway shares many similarities with the other MAPK signaling responses including inflammation, cell growth, differentiation, and death. Similar to ERK, the p38 MAPK pathway is stimulated by a wide array of stimuli including LPS and other TLR activators such as enterotoxin B and herpes simplex virus (Nick, Avdi, Gerwins, Johnson, & Worthen, 1996; Zachos, Clements, & Conner, 1999). In the context of inflammation and the inflammatory response, p38 plays a critical role in the production of inflammatory mediators to initiate leukocyte recruitment and activation. It accomplishes this task through the regulation of inflammatory genes including TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) and collagenase 1 and 3 (Lee et al., 1994) all of which are diminished in monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils and T lymphocytes in the presence of p38 inhibitor SB203580 (Marriott, Clarke, & Dalgleish, 2001). Previous studies have shown that GRK2 and p38 appear to oppose each other where GRK2 can inhibit p38 function by directly phosphorylating it whereas p38 inhibits GRK2-mediated GPCR desensitization (X. Liu et al., 2012; Peregrin et al., 2006). It regulates GRK2 by directly phosphorylating GRK2 at Ser670 inhibiting its ability to translocate to the outer membrane and interact with activated GPCRs for desensitization. This specifically has been observed in response to MCP-1 and the prevention of the CC chemokine receptor2 (CCR2) (Z. Liu et al., 2013). GRK2 is able to phosphorylate p38 at its Thr123 residue, which interferes with the ability of p38 to bind to MKK6, therefore, preventing its activation (Peregrin et al., 2006). Furthermore, altering the levels of GRK2 influences the activation of p38 and its functionality including differentiation and cytokine production. This alteration holds true in murine GRK2+/− macrophages and microglial cells; both of these cells exhibit increased p38 activation and TNFα production in response to LPS (Nijboer et al., 2010). In contrast to this, complete GRK2 silencing in mast cells decreases cytokine production (IL-6 and IL-13) in a p38 dependent manner during antigen-induced degranulation (Subramanian, Gupta, Parameswaran, & Ali, 2014). Lastly, GRK2 through its regulation of p38 has been linked to cytokine-induced pain by reducing the neuronal responsiveness to cytokines such as IL-1β and TNFα and thereby reducing cytokine-induced hyperalgesia (Eijkelkamp et al., 2012; Willemen et al., 2010).

Similar to ERK and p38 pathways, Jun-N terminus kinase (JNK) can also be activated by mitogens as well as a large variety of stimuli. The role of GRKs in JNK signaling in the immune system and inflammation is not very well characterized. GRK2 has a large and diverse regulatory capacity in the context of NFκB and MAPK signaling pathways that is dependent on expression level, cell type, stimulus, and many other factors. As we continue to study this role both in vitro and in vivo and our understanding of this regulation increases, it remains a likely possibility that novel therapeutic targets and treatments for inflammatory diseases can develop from these interactions.

GRK2 Regulation of Immune Processes

An important component of an effective immune system is the ability for the immune cells to arrive at the site of inflammation. This is achieved through a process called chemotaxis, where cells at the site of inflammation or disease produce chemokines that act on the chemokine receptors (mostly GPCRs) on immune cells to initiate a chemotactic response. The amplitude of that response is dependent on the amount of chemokines produced and their gradient as well as the expression levels of the receptors that are responding to them. This process is also dependent on a series of different steps in the chemotactic process including receptor sensing, cell polarization, membrane protrusion, and adhesion/de-adhesion cycles all of which can be cell type and stimulus-specific (Insall, 2013). Given that most of the chemokine receptors are GPCRs, these receptors undergo desensitization with constant stimulus and it is not surprising that the GRKs regulating that process play a critical role in chemotaxis and in the immune response. Interestingly, GRK2, GRK3, GRK5 and GRK6 are all expressed at high levels in the immune cells suggesting that alteration or regulation of their expression levels or functionality will drastically influence immune cell chemotaxis and the pathological progression of disease.

GRK2 has been heavily studied in its role in chemotaxis; but looking at the regulation of cellular migration by this kinase is complex. Studies have shown that this regulation is both cell type and stimulus dependent, with GRK2 acting most often in a canonical manner negatively regulating GPCR signaling (Arnon et al., 2011; Z. Liu et al., 2013; Zachos et al., 1999). Overexpression of GRK2 by transfection in cell lines increases phosphorylation and/or desensitization of different chemokine receptors such as CCR2b (Aragay et al., 1998), CCR5 (Olbrich, Proudfoot, & Oppermann, 1999), and CXCR1 (Raghuwanshi et al., 2012). Increased circulating neutrophils as well as increased macrophage localization to inflammatory sites have been observed in mice that are deficient for GRK2 in the myeloid cells or in bone marrow cells of low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout chimeric mice in an atherosclerosis model (Otten et al., 2013). Consistently, both T lymphocytes and splenocytes isolated from GRK2 heterozygous mice had increased migration due to increased activation of ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways in response to CCL5 and CXCL12 compared to WT controls (Vroon, Heijnen, Lombardi, et al., 2004). This, however, was not the case in the sepsis model in the myeloid-specific GRK2 knockout suggesting disease specific regulation (Parvataneni et al., 2011). Interestingly, a recent study has shown that acute mental stress significantly increased GRK2 levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) at both 30 and 60 minutes and had a positive correlation with levels of epinephrine that also increased after the stressor. This study suggests a link between stress and intracellular inflammatory signaling and chemotaxis (Blake Crabb et al., 2016). GRK2 levels are also reduced in cultured human T lymphocytes when exposed to oxidative stress or when co-cultured with activated neutrophils (Lombardi et al., 2002). Additionally, GRK2 has been examined in the context of various human diseases and neutrophils from patients with different disease conditions including malaria (Leoratti et al., 2012) and sepsis (Arraes et al., 2006) express increased GRK2 levels that is associated with decreased CXCR2 expression and reduced response to IL-8. When this phenomenon was studied in mice, exposure to IL-33 reversed this overexpression of GRK2 and restored CXCR2 expression leading to increased chemotaxis as well as increased bacterial clearance and survival (Jose C Alves-Filho et al., 2010).

In contrast to the above studies, GRK2 can also positively regulate chemotaxis in certain cell types. It’s hypothesized that this bimodal role for GRK2 may depend on the cell type as well as the polarization state of the cells. In polarized cells, such as epithelial cells, GRK2 has been shown to positively regulate cellular migration independently of its catalytic activity thus supporting protein-protein interaction as a potential mechanism (Penela et al., 2008). Further supporting this idea, membrane-targeted kinase mutants strongly enhance cell motility through interactions between GRK2 and GIT1 (GRK2-interacting factor) at the leading edge of polarized/migrating cells in wound healing assays (Penela et al., 2008). This association between GRK2 and GIT1 is critical for proper ERK1/2 activation and efficient cellular migration. Recent work in our lab has shown in colon epithelial cells GRK2 knockdown enhances epithelial migration in wound healing assays by critically regulating the activation of ERK1/2 in response to TNFα (manuscript in revision). These studies highlight the importance of ERK1/2 activation in polarized/migrating epithelial cells and the ability for GRK2 to influence migration and chemotaxis in a variety of manner. GRK2 has also been shown to directly phosphorylate histone deacetylase 6, a cytoplasmic histone deacetylase responsible for the deacetylation of tubulin and other substrates critical for cellular migration (Lafarga, Mayor, & Penela, 2012). Additionally, GRK2 can interact with and phosphorylate ERM proteins ezrin and radixin, both of which contribute to F-actin polymerization-dependent motility (Cant & Pitcher, 2005; Kahsai, Zhu, & Fenteany, 2010). These novel interactions and non-receptor substrates for GRK2 contribute to our understanding of GRK2s role in non-canonical regulation of GRK2 in cell motility.

GRK2 in Disease

In vitro experiments can give valuable insights into the mechanisms of GRK2 behavior but understanding the role of GRK2 in the context of human disease oftentimes is beyond the scope of an isolated cell line in culture. In mouse and human studies, GRK2 has been implicated in a variety of pathogenesis in multiple tissues and organ systems. GRK2 is a major player in several neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Suo & Li, 2010), multiple sclerosis (MS) (Vroon et al., 2005) and Parkinson’s disease (Bychkov, Gurevich, Joyce, Benovic, & Gurevich, 2008). In AD, GRK2 was shown to serve as a biomarker for early hypoperfusion-induced brain damage, which is associated with mitochondrial damage seen in patients with AD (Obrenovich, Palacios, Gasimov, Leszek, & Aliev, 2009). GRK2 levels are also increased during the early stages of damage in aged human and in AD patients (observed postmortem) (Obrenovich et al., 2009). This increased expression may lead to more interactions with α and β-synucleins both of which are substrates for GRK2 and have been linked to both Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases (Surguchov, 2008). Furthermore, GRK2 was shown to regulate metabotropic glutamate receptor function and expression, whose role has been implicated in AD and MS pathogenesis (Degos et al., 2013; Sorensen & Conn, 2003). Also, studies have shown that down-regulation of GRK2 following chronic inflammation sensitizes human and rodent neurons to excitotoxic neurodegeneration via over-action of group I mGluRs (Degos et al., 2013).

GRK2 has also been shown to play a prominent role in inflammatory hyperalgesia. GRK2 heterozygous mice suffer from chronic hyperalgesia due to continued microglial activation via p38-dependent TNFα production (Eijkelkamp, Heijnen, et al., 2010; Willemen et al., 2010) and prolonged activation of prostaglandin E2-mediated pathway. This prolonged activation is mediated through interactions with EPAC1 (exchange protein directly activated cAMP) and activation of protein kinase Cε- and ERK-dependent pathways (Eijkelkamp, Wang, et al., 2010; H. Wang et al., 2013). Through this same regulation of p38, GRK2 exacerbates brain damage in hypoxic-ischemic injury (Nijboer et al., 2010). The importance of GRK2 in this system is highlighted in that even a transient decrease in GRK2 levels (by intrathecal injection of GRK2 antisense oligodeoxynucleotides) is sufficient to produce long-lasting neuroplastic changes in nociceptor function that can lead to chronic pain (Ferrari et al., 2012).

Due to the cardiac developmental defects in the GRK2 homozygous knock out mice, GRK2 has been heavily studied in the context of cardiovascular diseases. GPCR signaling via the β-adrenergic receptor predominates during heart failure in an attempt to improve myocardial contractility and cardiac output. However, increased levels of GRK2 during heart failure causes an increase in β-adrenergic receptor desensitization reducing myocardial contractility and cardiac output worsening heart failure (Iaccarino et al., 2005). This reduced contractility triggers an influx of catecholamines, which leads to a cycle of activation and persistent desensitization of β-adrenergic receptors. Overexpression of GRK2 in vivo mimics this regulation and decreases myocardial contractility and cardiac output in response to adrenergic stimulation. These effects suggest impaired adrenergic receptor signaling (Brinks et al., 2010; E. P. Chen, Bittner, Akhter, Koch, & Davis, 2001). Conversely, inhibition of GRK2 results in increased contractility and enhanced survival in heart failure models (Raake et al., 2008; Vinge et al., 2008). Furthermore, competitive inhibition through βARKct (C-terminal peptide of GRK2) prevented cardiomyopathy and improved heart failure (Harding, Jones, Lefkowitz, Koch, & Rockman, 2001; Rengo et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2001; Daniela Sorriento et al., 2010). These benefits seen in the cardiovascular diseases have inspired researchers to try and develop GRK2 inhibitors as a therapeutic option in heart failure and has been met with success at least in preclinical models (Daniela Sorriento, Ciccarelli, Cipolletta, Trimarco, & Iaccarino, 2016).

Changes in GRK2 expression has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of other diseases. Overexpression of GRK2 in vascular smooth muscle cells has been shown to lead to the development of hypertension (Eckhart, Ozaki, Tevaearai, Rockman, & Koch, 2002; Keys, Zhou, Harris, Druckman, & Eckhart, 2005) and this increase in GRK2 expression is also found in human patients with hypertension (Gros et al., 1999). Also, GRK2 has been implicated in the development of atherosclerosis. Low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice with partial GRK2 deficiency in hematopoietic cells developed fewer atherosclerotic plaques (Otten et al., 2013). This partial GRK2 deficiency led to increased infiltration of macrophages to inflammatory sites resulting in plaques with smaller necrotic cores. Finally, GRK2 has a significant role in the pathogenesis of human and animal models of sepsis (Jose C Alves-Filho et al., 2010; Arraes et al., 2006; Nandakumar Packiriswamy et al., 2013; Nandakumar Packiriswamy, Parvataneni, & Parameswaran, 2012; Parvataneni et al., 2011), polymicrobial sepsis (Jose C Alves-Filho et al., 2010; Nandakumar Packiriswamy et al., 2013; Parvataneni et al., 2011), endotoxemia (Nandakumar Packiriswamy et al., 2012; Patial, Saini, et al., 2011a) and in the regulation of septic shock. Sepsis and a systemic inflammatory response syndrome are leading causes of mortality in intensive care units (Melamed & Sorvillo, 2009) and GPCRs play a major role in the pathophysiological events through regulation of the cardiovascular, immune and coagulatory responses. Given the role of GRK2 in the pathogenesis of sepsis, inhibition of GRK2 expression and/or activity may be a useful strategy for targeting human sepsis (Jose C Alves-Filho et al., 2010; Parvataneni et al., 2011). However, given that GRK2 is ubiquitously expressed and its role varies in different tissues and cell types, inhibition of GRK2 may be beneficial in some diseases whereas it may be deleterious in others. Thus, while GRK2 inhibitors are being developed, it is important to keep in perspective the various roles of GRK2 in different cell signaling pathways, the multitude of substrates/interacting partners and their potential involvement in the various diseases (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

GRK2 and its potential role in various disease processes. Some interacting partners/substrates are shown. Please see text for details.

GRK3

Biochemistry

GRK3, like GRK2, is ubiquitously expressed throughout the body but its expression levels are considered to be lower than those of GRK2 in all areas except for the central nervous system and the brain (Erdtmann-Vourliotis, Mayer, Ammon, Riechert, & Höllt, 2001). Despite these similarities in tissue expression, GRK3 has an independent role from GRK2 highlighted by its regulation in olfaction and neuronal functions. In the central nervous system, GRK3 is primarily located within the dorsal root ganglions and the olfaction neurons regulating the desensitization of odorant receptors and α2-adrenergic receptors (Walker, Peppel, Lefkowitz, Caron, & Fisher, 1999).

GRK3 in Inflammation

Role of GRK3 in inflammatory signaling has been less established than some of the other GRKs. However, GRK3 has been shown to play a role in ERK1/2 signaling where overexpression of GRK3 abolished β-arrestin 2 mediated activation of ERK1/2. This was seen in response to activation of a variety receptors including the β2-adrenergic receptor, cannabinoid receptor-2 (Franklin & Carrasco, 2013), angiotensin 1A receptor (Daniela Sorriento et al., 2008) and the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (Zheng et al., 2012). In support of this, bone marrow-derived leukocytes from GRK3 knockout mice exhibit enhanced ERK1/2 expression in response to CXCL12 (Tarrant et al., 2013). GRK3 can also interact with and modulate these pathways and so further study in this area is necessary to fully understand the regulatory capabilities of this GRK on these pathways.

GRK3 Regulation of Immune Processes

As indicated before, GRK2, GRK3, GRK5 and GRK6 are all expressed at high levels in the immune cells suggesting that alteration or regulation of their expression levels or functionality could influence immune cell chemotaxis and therefore progression of disease. Compared to the other GRKs relatively little work has been done on the role of GRK3 in these cells; however, recent work has shown that GRK3 is able to critically regulate immune behavior. GRK3 was identified as a negative regulator of CXCL12 (CXC chemokine ligand 12)/CXCR4 signaling (a defective pathway in human WHIM syndrome) and deficiency of GRK3 results in impaired CXCL12-mediated desensitization, enhanced response to CXCR signaling through ERK1/2 activation, altered granulocyte chemotaxis and mild myelokathexis (a form of chronic leukopenia) (Tarrant et al., 2013). Work done on human skin cells and leukocytes indicate that over-expression of GRK3 is able to restore CXCL12-induced internalization and desensitization of CXCR4 and normalize chemotaxis (Balabanian et al., 2008). GRK3 is also important in other granulocyte-dependent disease models by mediating the retention of cells in the bone marrow resulting in fewer circulating granulocytes in the blood as well as in the joints during inflammatory arthritis. In conjunction with regulation of CXCR4, GRK3 has also been reported to play an important role in oncology and influence the tumorigenicity, molecular subtype and metastatic potential of triple negative breast cancer, glioblastoma, ovarian tumors, medulloblastoma and malignant granulosa cells via dysregulation of GPCR signaling (Billard et al., 2016; King et al., 2003; Woerner et al., 2012). In a cultured leukemia cell line, GRK3-mediated receptor phosphorylation of the chemokine receptor CC3A and association with β-arrestins were essential for expression of the chemokine CCL2 (DeFea, 2013). GRK3 has also been shown to play a critical role in opioid receptor signaling in that Mu-opioid receptor and kappa-opioid desensitization is significantly slower in the GRK3 knock out mice (Stacey, Lin, Gordon, & McKnight, 2000).

GRK3 in Disease

Unlike GRK2, homozygous knockout mice of GRK3 are viable thus demonstrating different physiological roles for the members of the GRK2 family. GRK2 and GRK5 are well known for their role in cardiovascular diseases but the effect of GRK3 in this tissue is less understood. Transgenic mice expressing cardiac-specific GRK3 inhibitor exhibited enhanced ERK1/2 activation in response to α1-adrenergic receptor stimulation. Additionally, these transgenic mice showed elevated systolic blood pressure and hypertension due to hyperkinetic myocardium and hyper-responsiveness to α1-adrenergic receptor stimulation (Vinge et al., 2008). GRK3 has also been shown to be overexpressed in human prostate cancer and found to promote tumor growth and metastasis by enhancing angiogenesis (W. Li et al., 2014). Finally, based on its chromosomal location and sequence, GRK3 is believed to be a potential biomarker for bipolar disorder susceptibility through potential alterations in dopamine receptor desensitization (Niculescu et al., 2000). In mice, GRK3 deficiency plays no role in basal locomotor activity but interestingly, knocking out GRK3 significantly reduces locomotor and climbing responses to either cocaine or apomorphine (Raul R Gainetdinov, Premont, Bohn, Lefkowitz, & Caron, 2004) potentially through the desensitization of D3 dopamine autoreceptors (K.-M. Kim, Gainetdinov, Laporte, Caron, & Barak, 2005).

GRK4 Subfamily

The GRK4 subfamily is comprised of GRK4, GRK5, and GRK6 and is located ubiquitously throughout the body with the exception of GRK4, which is located primarily in the testes, kidney and cerebellum (Inglese et al., 1993). Structurally all members share the AGC kinase domain and a common N-terminus domain that expresses a PIP2 binding site that is similar to the GRK2 subfamily. The C-terminal domain aids in membrane localization and is regulated through palmitoylation sites on GRK4 and GRK6, but GRK5 is regulated through positively charged lipid-binding amphipathic helices (Cabrera-Vera et al., 2003). This regulation establishes an equilibrium between these GRKs and the membrane allowing for phosphorylation of both activated and inactivated GPCRs (Virlon et al., 1998). Interestingly, GRK4 has low sequence conservation with GRK5 and GRK6 in the C-terminal region and forms a different crystal structure. These differences between GRK4 and the rest of the subfamily have been shown to influence its ability to translocate to the plasma membrane (H. Xu, Jiang, Shen, Fischer, & Wedegaertner, 2014). It has been hypothesized that these changes in structure and membrane targeting capabilities may be a result of the tissue-specific expression of GRK4 and may account for some of the functional variability amongst this subfamily.

GRK4

Biochemistry, role in inflammation and disease

GRK4 can be regulated and alternatively spliced into four different splice variants that are all capable of independent functions including GCPR regulation. As indicated before, GRK4 has not been examined in detail in immune cells and its role in inflammatory disease is largely unknown. It is known that GRK4α constitutively phosphorylates the dopamine receptor in the proximal tubule reducing its responsiveness hinting at an essential role in the regulation of hypertension. In fact, constitutive phosphorylation of the dopamine receptor is problematic in people with hypertension and polymorphisms in GRK4 can cause dysregulation of dopamine-stimulated salt and fluid excretion in the kidneys (Felder et al., 2002). Similarly, GRK4γ is able to phosphorylate the dopamine receptor as well but only upon agonist activation. These differences between splice variants indicate areas of similarities but also variability amongst the splice variants leading to questions about the regulation of GRK4 translation that have yet to be answered (Villar et al., 2009). Role of GRK4 in the other tissues where it is expressed is less clear and requires further study.

Expression of GRK4 in the cerebellum seems to be limited to the Purkinje cells and may be involved in the regulation of metabotropic glutamate 1 receptors. The regulation of these receptors suggests a role for GRK4 in motor coordination as well as in learning but further work remains to be done in this area (Iacovelli et al., 2003). In a recent study, it was shown that GRK4 levels are upregulated in Fmr1-null mice, suggesting that RNA-binding protein (FMRP) negatively regulates the expression of GRK4. Fragile X syndrome is caused by the silencing of the Fmr1 gene and lack of FMRP. Since FMRP negatively regulates GRK4 it is hypothesized that this silencing results in increased GRK4 levels in Fragile-X syndrome. Increased GRK4 could contribute to cerebellum-dependent phenotypes due to deregulated desensitization of GABA-B receptors (Maurin et al., 2015). Finally, due to its localization in the cerebellum and testes studies in GRK4 knockout mice were done investigating its role in these tissues. Interestingly, GRK4 knockout animals showed no differences in basal levels or in response to cocaine for locomotor activity or motor coordination (Raul R Gainetdinov et al., 2004). Furthermore, despite the high levels of GRK4 in the testes, there were no apparent changes in fertility or sperm function and no obvious phenotypes were detected in these animals (Virlon et al., 1998). Thus, the role of GRK4 in these tissues remains to be elucidated and more work needs to be done to fully understand the role of this kinase in inflammatory processes.

GRK5

Biochemistry

GRK5 is unique among its family members due to the presence of positively charged lipid-binding amphipathic helices on its C-terminus. There is also evidence supporting an interaction with the membrane through this C-terminus involving a region of the RH domain (H. Xu et al., 2014). These motifs, in combination with the polybasic N-terminus regions predominantly localize GRK5 to the plasma membrane. This presence at the membrane allows for significant activation independent phosphorylation of several GPCRs (L. Li et al., 2015). GRK5 has recently been crystalized in two unique structures both of which crystalize GRK5 as a monomer with its C-termini forming consistent structures that pack closely to the RH domain. Disrupting this interface between the C-terminus and the RH domain significantly decreased the catalytic activity on GPCRs in vitro as well as in cells. This same study concluded that individual GRK5 subunits were insufficient for persistent membrane association (H. Xu et al., 2014). Additionally, GRK5 also has a nuclear localization motif and can accumulate in the nucleus where it can interact with proteins including class II histone deacetylase and mediate gene transcription (Martini et al., 2008). This localization is in competition with membrane localization sequences on the C and N-termini. These termini are in fact key regulatory sites. For example, phosphorylation by PKC on the C-terminus is inhibitory to its function. Calmodulin (CaM) is inhibitory to most GRKs but is especially preferential to the GRK4 subfamily. Ca2+•CaM can bind to both the N- and C-termini phospholipid binding motifs and disrupt membrane association of GRK5. This then allows the nuclear localization motif to direct GRK5 to the nucleus (Gold et al., 2013). As mentioned, GRK5 is ubiquitously expressed but is especially expressed at high levels in the heart, lungs, placenta, and kidney with lower expression in the brain (except for the limbic system). Interestingly, expression levels of GRK5 have been shown to increase two-fold during neuronal differentiation (Inglese et al., 1993).

GRK5-Role in Inflammation

Similar to GRK2, GRK5 plays a major role in NFκB signaling and is able to directly interact with and phosphorylate NFκB p105 (one of the IκB members). This was shown to inhibit Toll-like receptor-4-induced IκB kinase β-mediated phosphorylation of p105, thus negatively regulating lipopolysaccharide-induced ERK activation in macrophages (Parameswaran et al., 2006). Furthermore, GRK5 was subsequently discovered to interact with an additional member of the IκB family, IκBα, to facilitate the nuclear accumulation of IκBα by masking its nuclear export signal. This nuclear accumulation of IκBα led to decreased NFκB activation in endothelial cells (Daniela Sorriento et al., 2008). Both of these interactions were shown to be dependent on the RH domain of GRK5 and independent of its kinase domain. Further research has also shown non-canonical regulation of NFκB by GRK5. GRK5 was demonstrated to phosphorylate Ser32/36 – the same sites phosphorylated by IκB kinase α and β. This was further supported by decreased levels of cytokines and chemokines in GRK5 knockout mice compared to wild-type in endotoxemia model (Patial, Shahi, et al., 2011; Patial et al., 2009). Further evidence showed that IκBα phosphorylation and p65 nuclear translocation were significantly reduced in LPS-treated GRK5 deficient peritoneal macrophages. As these studies progressed, there have been contrasting results in different models of the GRK5 knockout mouse. Wherein mice generated by the Lefkowitz group (Wu et al., 2012) found that endothelial GRK5 stabilized IκBα similar to earlier studies by Sorriento et al (Daniela Sorriento et al., 2008), studies done in macrophages using a different GRK5 knock out mice did not show any role for GRK5 in IκBα phosphorylation or p65 translocation. More recent studies using mice from the Lefkowitz group, however, have shown that GRK5 positively regulates the NFκB pathway in cardiomyocytes (Islam, Bae, Gao, & Koch, 2013). It is unclear the exact reasoning behind these discrepancies in GRK5 behavior but it has also been shown that GRK5 itself can be regulated by the NFκB pathway, generating a potential positive feedback loop between GRK5 and NFκB (Islam & Koch, 2012). However, in primary peritoneal macrophages, GRK5 was downregulated after TLR4 activation suggesting that both regulation of GRK5 expression and its influence on the NFκB pathway are distinct in different cell types and conditions. Interestingly, however, GRK5 was shown to be an evolutionarily conserved kinase in NFκB regulation in human cell lines as well as different species including Drosophila and zebrafish (Valanne et al., 2010) thus demonstrating an important role for this kinase in this pathway.

There are some studies examining the relationship between GRK5 and MAPK signaling pathways. GRK5 has been shown to play a role in support of β-arrestin2-mediated ERK activation following stimulation of V2 vasopressin and angiotensin II receptors despite its minor role in desensitization (J. Kim et al., 2005; Ren et al., 2005). This was later determined to independent of G-protein coupling (Shenoy et al., 2006). Conversely, in macrophages, through its regulation of p105, GRK5 negatively regulates LPS-stimulated ERK activation (Parameswaran et al., 2006).

JNK can be activated by mitogens as well as a large variety of stimuli including: environmental stresses (heat shock, ionizing radiation and oxidants), genotoxins (topoisomerase inhibitors and alkylating agents), ischemic-reperfusion injury, mechanical shear stress, vasoactive peptides, proinflammatory cytokines and pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules/danger-associated molecular patterns (Dabrowski, Grady, Logsdon, & Williams, 1996; Gómez del Arco, Martínez-Martínez, Calvo, Armesilla, & Redondo, 1996; Knight & Buxton, 1996; Komuro et al., 1996; Y. Liu, Gorospe, Yang, & Holbrook, 1995). JNK activation induces the translocation of transcription factors AP-1, c-Jun, ATF-2 and ELK-1 to the nucleus to regulate inflammatory gene transcription (Y. Liu et al., 1995). JNK activation of AP-1 also plays a critical role in the synthesis of TNFα and for the proliferation and differentiation of lymphocytes, giving it a vital role in the regulation of the immune system (Gómez del Arco et al., 1996; Jung et al., 1995). In mice over-expressing GRK5 in cardiac myocytes, constitutively active mutants of α1BAR exhibited attenuation of JNK activation in comparison to the controls. GRK5 also had an influence of α1BAR signaling but the complexity of this interaction and regulation remains to be fully elucidated (Eckhart et al., 2000). Finally, there is little known about the relationship between GRK5 and p38, highlighting an area of study that still requires further work to understand the role for this kinase in the MAPK processes.

It is clear that GRK5 plays a critical role in the regulation of NFκB and MAPK signaling in inflammation and immune signaling. With further understanding of this regulation, it may become apparent if these signaling pathways are targetable regulatory sites for therapeutics in inflammatory diseases (Fig 2).

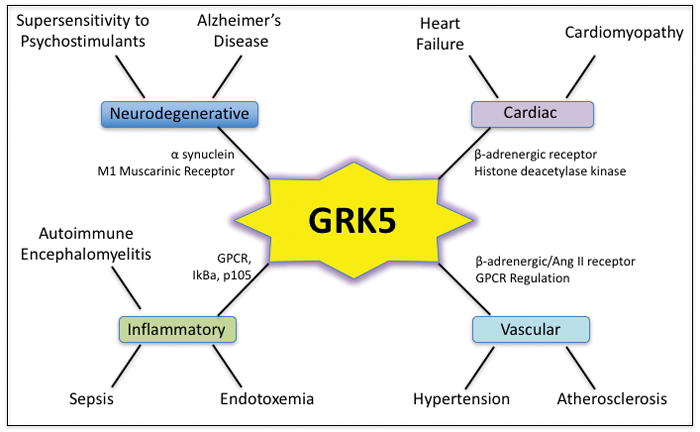

Fig 2.

GRK5 and its potential role in various disease processes. Some interacting partners/substrates are shown. Please see text for details.

GRK5 Regulation of Immune Processes

GRK5 can regulate GPCRs necessary for chemotaxis in both canonical and non-canonical fashion. Unlike GRK2, GRK5 has been shown to regulate these processes in much fewer cell types, primarily in monocytes. GRK5 modulates chemotaxis in these cells by regulating CCR2, a GPCR for monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (Wu et al., 2012). GRK5 can also influence these cells in a non-canonical fashion through regulation of colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor, a receptor tyrosine kinase (Wu et al., 2012). By regulating CCR2 desensitization and inhibition of monocyte migration, GRK5 has been shown to attenuate atherosclerosis (Wu et al., 2012). Additionally, GRK5 can regulate CXCR4 desensitization via phosphorylation of HIP (HSP70-interacting protein) in an in vitro model (Barker & Benovic, 2011). Work in our lab, however, has shown that GRK5 has little to no role in immune chemotaxis in a polymicrobial septic peritonitis model (Nandakumar Packiriswamy et al., 2013) and similar findings were reported in an arthritic model (Tarrant et al., 2008). This however, was again model specific since GRK5 did regulate neutrophil infiltration in E. coli pneumonia model (Nandakumar Packiriswamy, Steury, McCabe, Fitzgerald, & Parameswaran, 2016). GRK5 has also been shown to influence migration and invasion of cancer cells. In prostate cancer, GRK5 has been shown to regulate cell migration and invasion through interactions with moesin (ERM (ezrin-radixin-moesin)) proteins. It accomplishes this primarily through phosphorylation of moesin on Thr-66 residue regulating its cellular distribution (Chakraborty et al., 2014). Additionally, GRK5 may be involved in neutrophil granulocyte exocytosis. Signal transduction pathways regulating this function are poorly defined although several proteins, including Src, are known to participate in this response. Proteomic studies first identified a potential Src tyrosine kinase motif on GRK5 and phosphorylation of GRK5 by Src was then confirmed in an in vitro kinase assay. Furthermore, immunoprecipitation of phosphorylated GRK5 with Src in intact cells was decreased in the presence of a Src inhibitor, possibly implicating it in the regulation of granulocyte exocytosis (Luerman et al., 2011).

GRK5 in Disease

GRK5 also plays a prominent role in a multitude of pathologies (Fig 2). GRK5 canonically regulates muscarinic receptors but shows a preference for M2 and M4 receptors (J. Liu et al., 2009). These receptors are present in the presynaptic cells and negatively regulate acetylcholine release in hippocampal memory circuits. Abnormal increases in presynaptic cholinergic activity causes a decrease in acetylcholine release, therefore, decreasing postsynaptic muscarinic M1 activity. M1 signaling has been shown to inhibit β-amyloidogenic APP processing and decreased β-amyloid accumulation (Sadot et al., 1996). This connection might be the reason that an Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-like pathology is observed in GRK5-deficient mice. Further connecting GRK5 to AD is its ability to phosphorylate α-synuclein and tubulin possibly influencing their polymerization and neuronal functions as seen in AD (Christopher V Carman, Som, Kim, & Benovic, 1998).

GRK5 has many similarities to GRK2 in its role in cardiovascular diseases. Expression and activity of GRK5 is increased during heart failure inducing β-adrenergic receptor desensitization, reducing myocardial contractility and worsening heart failure (E. P. Chen et al., 2001). Overexpression of GRK5 in these cells decreases myocardial contraction and cardiac output in response to adrenergic stimulation (Brinks et al., 2010; E. P. Chen et al., 2001). Conversely its inhibition results in increased cardiac contractility and enhanced survival in heart failure patients (Raake et al., 2008; Vinge et al., 2008). Inhibition of GRK5 with adGRK5-NT (N-terminal peptide of GRK5) prevented cardiomyopathy and improved heart failure (Harding et al., 2001; Rengo et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2001; Daniela Sorriento et al., 2010). Again similar to GRK2, overexpression of GRK5 in the vascular smooth muscle cells led to the development of hypertension through regulation of β1-adrenergic receptor and Angiotensin II receptors (Eckhart et al., 2002; Keys et al., 2005). In addition to these canonical GPCR dependent roles, GRK5, through its nuclear localization signal, has been shown to accumulate in the nucleus of cardiomyocytes and function as a histone deacetylase kinase and promote cardiac hypertrophy (Martini et al., 2008). GRK5 has also been implicated in the development of atherosclerosis and its deficiency in apolipoprotein E knockout mice leads to development of more aortic atherosclerosis than their wild-type controls (Wu et al., 2012). Investigating the role of GRK5 in endotoxemia and polymicrobial sepsis models, our lab has shown that GRK5 deficiency leads to diminished cytokine levels (Nandakumar Packiriswamy et al., 2013, 2012; Patial, Shahi, et al., 2011) likely through decreased NFκB activation in tissues and macrophages (as outlined above). In addition to these reduced cytokine levels, GRK5-deficient mice also showed decreased thymocyte apoptosis and immune suppression (Nandakumar Packiriswamy et al., 2013). This immune suppression was attributed to reduced plasma corticosterone levels in these mice suggesting regulation of the pituitary-adrenal axis by GRK5. With its diverse role in inflammatory signaling as well as its role in multiple diseases, furthering our understanding of this kinase is critical for our ability to effectively design therapeutics and treatments targeting GRK5 in these various pathologies (Fig 2).

GRK6

Biochemistry

GRK6 is present ubiquitously throughout the body but is one of the most prominent GRKs in the striatum and other dopaminergic brain areas, particularly in the GABAergic and cholinergic areas. In these tissues, GRK6 localizes primarily in the plasma membrane. GRK6α, one of the four splice variants, however can translocate to the nucleus; although its function there is unclear (Richard T Premont & Gainetdinov, 2007). Subcellular localization of GRK6 is regulated through both its C-terminus which can be palmitoylated and can help anchor this GRK to the plasma membrane (Loudon & Benovic, 1997). Interestingly, in the brain GRK6 is primarily localized to synaptic membranes (Ahmed, Bychkov, Gurevich, Benovic, & Gurevich, 2008), suggesting that there must be neuronal specific mechanisms for altering the localization of GRK6; however, the specific protein partners that govern this remain unknown. For its role in GPCR regulation and desensitization GRK6 has been shown to phosphorylate GPCRs in both activated and inactivated state with some notable exceptions such as the D1 dopamine receptor (L. Li et al., 2015). Structurally, GRK6 is currently the only member of the family that has been successfully crystallized in a conformation that is expected to be an active conformation and is one of the only two structures that were able to detect the N-terminal region (along with GRK1). It was shown in these structures that the extreme N-terminal amino acids become helical and are able to interact with both lobes of the kinase domain, helping to align the various catalytic residues contributed by each lobe (Boguth et al., 2010). Mutational studies examining the role of these helical N-terminal motifs supported the model where the exposed hydrophobic residues at the apex of the helix are critical for GPCR phosphorylation (Boguth et al., 2010).

GRK6 in Inflammation