Abstract

Purpose

In the paper, we describe and discuss the results of epidemiological studies concerning myopia carried out in Poland.

Materials and Methods

Results from the examination of 5601 Polish school children and students (2688 boys and 2913 girls) aged 6 to 18 years were analyzed. The mean age was 11.9 ± 3.2 years. Every examined student had undergone the following examinations: distance visual acuity testing, cover test, anterior segment evaluation, and cycloplegic retinoscopy after instillation of 1% tropicamide, and a questionnaire was taken.

Results

We have found that (1) intensive near work (writing, reading, and working on a computer) leads to a higher prevalence of myopia, (2) watching television does not influence the prevalence of myopia, and (3) being outdoors decreases the prevalence of myopia.

Conclusions

The results of our study point to insufficiency of accommodation contributing to the pathogenesis of myopia.

1. Introduction

Myopia is a major and still unresolved health problem in the world. It is currently estimated that more than 22% of the world population has myopia. This means that 1.5 billion people have myopia. In East Asian countries, the prevalence of myopia is at 70–80%. In Western countries, 25–40% has myopia. In the United States, the number of myopes has double in the past 30 years [1–3].

Myopia is determined by genetic and environmental factors [4]. Environmental factors include reading, writing, and visual work when using a computer. Some researchers believe that even watching television has an influence on the development of myopia [5–17]. It is currently believed that outdoor activity leads to a lower prevalence of myopia [10, 13, 14, 18–35].

Research into the epidemiology of myopia is ongoing throughout the entire world [1–3, 5–31]. In Poland, the greatest achievements in myopia research belong to the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin [32, 33]. That is why we decided to present our results.

2. Materials and Methods

In this paper, we describe and discuss the results of epidemiological studies concerning myopia carried out in Szczecin, Poland. Special attention was put on the role of reading, writing, and visual work using a computer and outdoor activity.

The studies were carried out from October 2000 till March 2009. Results from the examination of 5601 Polish school children and students (2688 boys and 2913 girls) aged 6 to 18 years were analyzed. The mean age was 11.9 ± 3.2 years. The students examined were Caucasian, and there were no children of mixed ethnicity. Every examined student had undergone the following examinations: distance visual acuity testing, cover test, anterior segment evaluation, and cycloplegic retinoscopy after instillation of 1% tropicamide, and a questionnaire was taken. The methodology of the examination has been described in details in previous works as follows. Participation was voluntary. Before beginning the examinations, the doctors met with the children, their parents, or legal guardians and teachers. It was explained what the examinations were about. The children, parents, or legal guardians and teachers had an opportunity to discuss the study with the experimenters prior to giving consent. Informed consent as well as date of birth was obtained in each case from children, parents, or legal guardians and school principals. The studies were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Pomeranian Medical University. The research protocol adhered to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects.

Every examined person underwent retinoscopy under cycloplegia. Cycloplegia was induced with two drops of 1% tropicamide administered 5 min apart. Thirty minutes after the last drop, pupil dilation and the presence of light reflex was evaluated as later retinoscopy was performed. Retinoscopy was performed in darkened school's consulting rooms.

The refractive error readings were reported as a spherical equivalent (SE) (sphere power plus half-negative cylinder power). Hyperopia was defined to be spherical equivalent higher than +0.5 D and emmetropia to be higher than −0.5 and lower than +0.5 D. Myopia was defined to be with a SE lower than −0.5 D. Astigmatism did not exceed 0.5 DC. The mean SE was calculated after examination of both eyes [32, 33].

3. Results

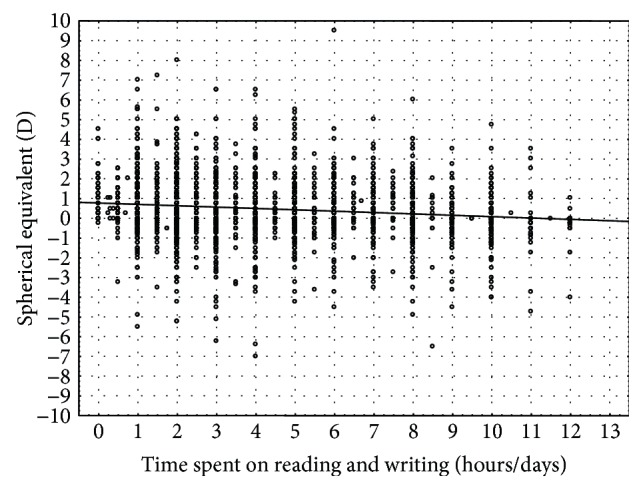

After having examined the 5601 students, it has been shown that reading and writing lead to a higher prevalence of myopia (p < 0.000001) [32] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean spherical equivalent in relation to reading and writing.

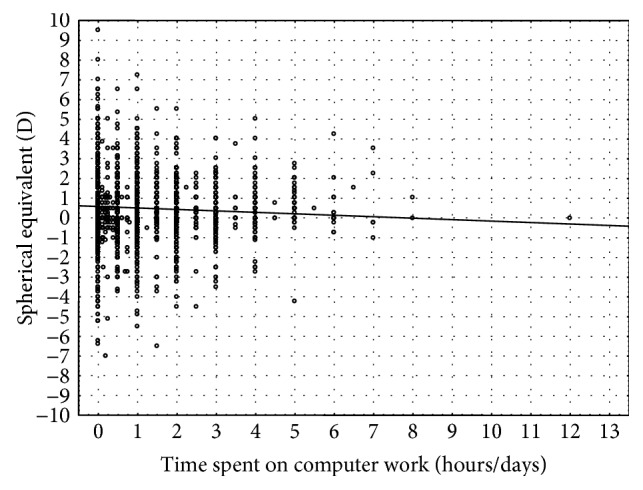

It has also been observed that working on a computer leads to a higher prevalence of myopia (p < 0.000001) [32] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean spherical equivalent in relation to using a computer.

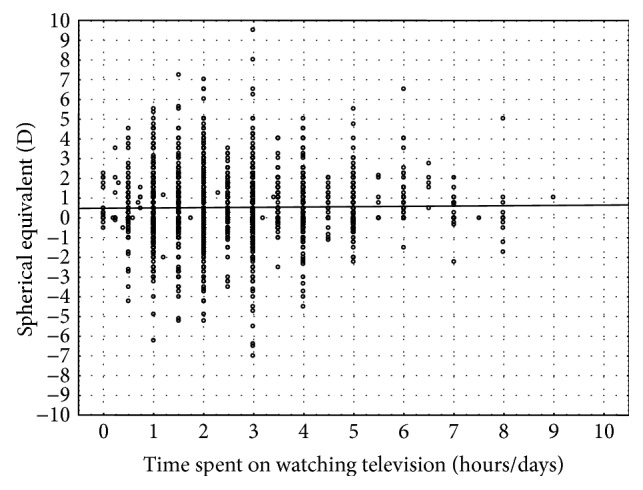

It has been shown that watching television does not have an influence on the prevalence of myopia (p = 0.31) [32] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean spherical equivalent in relation to watching television.

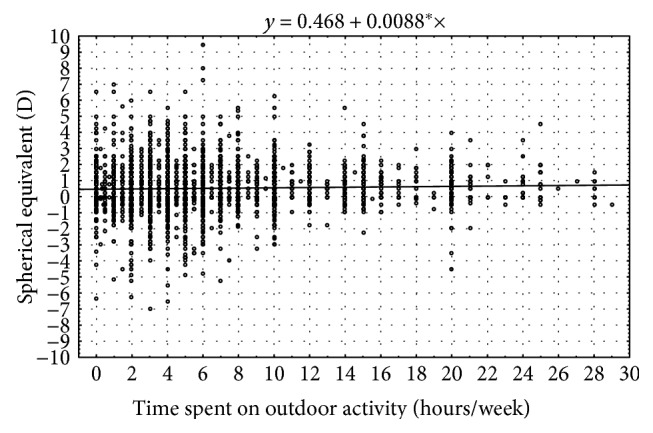

Outdoor activity however leads to a lower prevalence of myopia (p < 0.007) [33] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mean spherical equivalent in relation to outdoor activity.

4. Discussion

Opinions concerning the influence of reading, writing, and visual work when using a computer, watching television, and outdoor activity are varied. Most authors accept that reading, writing, and visual work when using a computer lead to a higher prevalence of myopia. However, some authors debate these relationships. Concerning watching television, most authors believe that it does not have an influence on the development of myopia (Table 1). Outdoor activity however decreases the prevalence of myopia (Table 2) [3, 4, 32, 33].

Table 1.

Dependency between reading, writing, using a computer, or watching TV and myopia.

| Reference | Country | Dependency between reading and writing and myopia | Dependency between using a computer and myopia | Dependency between watching TV and myopia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cole et al. [5] | Australia | + | ||

| Czepita et l. [6] | Poland | + | + | |

| Giloyan et al. [7] | Armenia | + | ||

| Khader et al. [8] | Jordan | + | + | |

| Kinge et al. [9] | Norway | + | ||

| Konstantopoulos et al. [10] | Greece | + | + | |

| Li et al. [11] | China | + | + | |

| Mutti et al. [12] | U.S.A. | + | ||

| Pärssinen et al. [13] | Finland | + | + | |

| Saw et al. [14] | China | + | ||

| Saxena et al. [15] | India | + | + | + |

| Wong et al. [16] | Hong Kong | + | ||

| You et al. [17] | China | + | + | + |

Table 2.

Dependence between outdoor activity and myopia.

| Reference | Country |

|---|---|

| Dirani et al. [18] | Singapore |

| French et al. [19] | Australia |

| Guggenheim et al. [20] | UK |

| Guo et al. [22] | China |

| Guo et al. [23] | China |

| Guo et al. [21] | China |

| Jacobsen et al. [24] | Denmark |

| Jones et al. [25] | U.S.A. |

| Lin et al. [26] | China |

| Mutti et al. [12] | U.S.A. |

| Ngo et al. [27] | Singapore |

| Pärssinen et al. [13] | Finland |

| Rose et al. [28] | Australia |

| Saxena et al. [15] | India |

| Shah et al. [29] | UK |

| You et al. [17] | China |

| Wu et al. [30] | Taiwan |

| Zhou et al. [31] | China |

It is accepted that the higher prevalence of myopia due to reading, writing, and visual work using a computer are attributed to insufficiency of accommodation during visual near work. It has also been observed that spasms of accommodation are considered the factors of myopia [4]. The results of these studies were confirmed by researchers from the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, Poland, by achieving a coefficient of statistical significance p < 0.000001 [32].

During the years of 2005-2006, Buehren et al. [34] and Collins et al. [35] have showed that reading and visual work when using a computer leads to a change in the shape of the cornea, which may lead to the development of myopia. The results obtained by the authors are in agreement with the hypothesis that lid-induced corneal aberrations may play a significant role in the development of myopia.

Most authors believe that watching television does not cause myopia. The argument behind this belief is that watching television usually from a few meters away does not cause insufficiency of accommodation [4]. Research done at the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, Poland, has also proved that watching television does not lead to a higher prevalence of myopia (p = 0.31) [32]. However, it happens that watching television does lead to a quicker development of myopia when the television monitor is placed too close to the eye [4].

Currently, it is accepted that outdoor activity leads to a lower prevalence of myopia. This is probably due to the fact that during distant visual work, there is no spasm of accommodation [3, 4]. This relationship has been also proven by research carried out at the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, Poland, achieving a coefficient of statistical significance of p < 0.007 [33].

It also has to be added that the results of our research are reliable because they have been conducted on a large and homogenous group of people of the Caucasian race. Besides, our research was done after cycloplegia.

5. Conclusions

The results of the examinations show that insufficiency of accommodation has a role in the pathogenesis of myopia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Holden B., Sankaridurg P., Smith E., Aller T., Jong M., He M. Myopia, an underrated global challenge to vision: where the current data takes us on myopia control. Eye. 2014;28(2):142–146. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wojciechowski R. Nature and nurture: the complex genetics of myopia and refractive error. Clinical Genetics. 2011;79(4):301–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zadnik K., Mutti D. O. Incidence and distribution of refractive anomalies. In: Benjamin W. J., editor. Borish’s Clinical Refraction. St Louis, MO: Butterworth Heinemann, Elsevier; 2006. pp. 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goss D. A. Development of ametropias. In: Benjamin W. J., editor. Borish’s Clinical Refraction. St Louis, MO: Butterworth Heinemann, Elsevier; 2006. pp. 56–92. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole B. L., Maddocks J. D., Sharpe K. Effect of VDUs on the eyes: report of a 6-year epidemiological study. Optometry and Vision Science. 1996;73(8):512–528. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199608000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czepita D., Mojsa A., Ustianowska M., Czepita M., Lachowicz E. Reading, writing, working on a computer or watching television, and myopia. Klinika Oczna. 2010;112(10−12):293–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giloyan A., Harutyunyan T., Petrosyan V. Risk factors for developing myopia among schoolchildren in Yerevan and Gegharkunik Province, Armenia. Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 2017;24(2):97–103. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1257028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khader Y. S., Batayha W. Q., Abdul-Aziz S. M. I., Al-Shiekh-Khalil M. I. Prevalence and risk indicators of myopia among schoolchildren in Amman, Jordan. La Revue de Santé de la Méditerranée orientale. 2006;12(3-4):434–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinge B., Midelfart A., Jacobsen G., Rystad J. The influence of near-work on development of myopia among university students. A three-year longitudinal study among engineering students in Norway. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2000;78(1):26–29. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078001026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konstantopoulos A., Yadegarfar G., Elgohary M. Near work, education, family history, and myopia in Greek conscripts. Eye. 2008;22(4):542–546. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S. M., Li S. Y., Kang M. T., et al. Near work related parameters and myopia in Chinese children: the Anyang Childhood Eye Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(8, article e0134514) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutti D. O., Mitchell G. L., Moeschberger M. L., Jones L. A., Zadnik K. Parental myopia, near work, school achievement, and children’s refractive error. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2002;43(12):3633–3640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pärssinen O., Kauppinen M., Viljanen A. The progression of myopia from its onset at age 8–12 to adulthood and the influence of heredity and external factors on myopic progression. A 23-year follow-up study. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2014;92(8):730–739. doi: 10.1111/aos.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saw S. M., Hong R. Z., Zhang M. Z., et al. Near-work activity and myopia in rural and urban schoolchildren in China. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology & Strabismus. 2001;38(3):149–155. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-20010501-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saxena R., Vashist P., Tandon R., et al. Prevalence of myopia and its risk factors in urban school children in Delhi: the North India Myopia Study (NIM Study) PLoS One. 2015;10(2, article e0117349) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong L., Coggon D., Cruddas M., Hwang C. H. Education, reading, and familial tendency as risk factors for myopia in Hong Kong fishermen. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 1993;47(1):50–53. doi: 10.1136/jech.47.1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.You Q. S., Wu L. J., Duan J. L., et al. Factors associated with myopia in school children in China: the Beijing Childhood Eye Study. PLoS One. 2012;7(12, article e52668) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dirani M., Tong L., Gazzard G., et al. Outdoor activity and myopia in Singapore teenage children. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2009;93(8):997–1000. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.150979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.French A. N., Morgan I. G., Mitchell P., Rose K. A. Risk factors for incident myopia in Australian schoolchildren. The Sydney adolescent vascular and eye study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(10):2100–2108. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guggenheim J. A., Northstone K., McMahon G., et al. Time outdoors and physical activity as predictors of incident myopia in childhood: a prospective cohort study. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2012;53(6):2856–2865. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo Y., Liu L. J., Tang P., et al. Outdoor activity and myopia progression in 4-year follow-up of Chinese primary school children: the Beijing Children Eye Study. PLoS One. 2017;12(4, article e0175921) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo Y., Liu L. J., Xu L., et al. Outdoor activity and myopia among primary students in rural and urban regions of Beijing. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(2):277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo Y., Liu L. J., Xu L., et al. Myopic shift and outdoor activity among primary school children: one-year follow-up study in Beijing. PLoS One. 2013;8(9, article e75260) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobsen N., Jensen H., Goldschmidt E. Does the level of physical activity in university students influence development and progression of myopia?–a 2-year prospective cohort study. Investigative of Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2008;49(4):1322–1327. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones L. A., Sinnott L. T., Mutti D. O., Mitchell G. L., Moeschberger M. L., Zadnik K. Parental history of myopia, sports and outdoor activities, and future myopia. Investigative of Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007;48:3524–3532. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Z., Vasudevan B., Jhanji V., et al. Near work, outdoor activity, and their association with refractive error. Optometry and Vision Science. 2014;91(4):376–382. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ngo C. S., Pan C. W., Finkelstein E. A., et al. A cluster randomised controlled trial evaluating an incentive-based outdoor physical activity programme to increase outdoor time and prevent myopia in children. Ophthalmic & Physiological Optics. 2014;34(3):362–368. doi: 10.1111/opo.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rose K. A., Morgan I. G., Ip J., et al. Outdoor activity reduces the prevalence of myopia in children. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1279–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah R. L., Huang Y., Guggenheim J. A., Williams C. Time outdoors at specific ages during early childhood and the risk of incident myopia. Investigative of Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2017;58:1158–1166. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-20894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu P. C., Tsai C. L., Hu C. H., Yang Y. H. Effects of outdoor activities on myopia among rural school children in Taiwan. Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 2010;17(5):338–342. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2010.508347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou Z., Morgan I. G., Chen Q., Jin L., He M., Congdon N. Disordered sleep and myopia risk among Chinese children. PLoS One. 2015;10(3, article e0121796) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czepita M., Kuprjanowicz L., Safranow K., et al. The role of reading, writing, using a computer or watching television in the development of myopia. Ophthalmology Journal. 2016;1(2):53–57. doi: 10.5603/OJ.2016.0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Czepita M., Kuprjanowicz L., Safranow K., et al. The role of outdoor activity in the development of myopia in schoolchildren. Pomeranian Journal of Life Sciences. 2016;62(4):30–32. doi: 10.21164/pomjlifesci.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buehren T., Collins M. J., Carney L. G. Near work induced wavefront aberrations in myopia. Vision Research. 2005;45(10):1297–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collins M. J., Buehren T., Bece A., Voetz S. C. Corneal optics after reading, microscopy and computer work. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2006;84(2):216–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]