Abstract

Objectives

This review investigates the impact of corticosteroids on donation rates and transplant outcomes in light of findings from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and to highlight the sources of uncertainty in this unresolved donor management issue.

Data sources

We searched electronic databases, trial registries and conference proceedings for RCTs evaluating corticosteroid therapy in neurologically deceased donors.

Study selection and data extraction

Independent reviewers assessed eligibility, evaluated risk of bias and abstracted data, including donor haemodynamic data, number of organs recovered and transplant outcomes. Where possible, we pooled results. For each outcome, we assessed the overall quality of evidence using The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology.

Data synthesis

Eleven RCTs with different corticosteroid regimens were included. Most trials assessed a once-daily infusion of methylprednisolone. Aside from one study showing improved liver graft function, no individual study or pooled analysis showed benefit of corticosteroids for any outcome: vasopressor use (three trials; relative risk (RR) 0.96; 95% CI 0.89 to 1.05), multiple organs recovered (two trials; RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.61 to 1.11), acute graft rejection (three trials; RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.60 to 1.39) or graft dysfunction (eight trials; RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.24). Two trials investigated adverse effects and found similar rates between groups. Quality of evidence was moderate or low for all outcomes.

Conclusion

Current clinical trials are limited in numbers and size to identify benefits or harms of corticosteroid therapy for deceased organ donors. In the face of these results, administering or withholding steroids both appear reasonable courses of action.

Keywords: Intensive & critical care, tissus and organ procurement, Transplant medicine, Graft rejection, Methylprednisolone, Brain death

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An exhaustive search strategy and strict adherence to systematic review methodology make this review the most rigorous on the topic.

Our comprehensive GRADE approach improves the transparency regarding the quality of the available evidence on the effect of steroids in potential organ donors.

Available data only allows for limited inference on the effects of steroid on graft outcome due to varied definitions of graft outcomes.

The clinical relevance of our results is limited by the inability to assess for differences in steroid effects associated with variations in dose or timing of administration.

Introduction

For patients with end-stage organ dysfunction, transplantation is a life-saving intervention. Universally, organs available for transplantation are insufficient to meet population needs.1 Optimal medical management of deceased organ donors may help to address this shortage.2 3

In the process that culminates in neurological death, cerebral herniation can induce a catecholamine storm that, when severe, leads to cardiovascular collapse. Haemodynamic instability of any degree threatens the viability of potentially recoverable organs4 and disturbances in the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis can be an important contributor.5 Though the prevalence of adrenal insufficiency among neurologically deceased organ donors is uncertain,6–9 corticosteroid therapy may alleviate haemodynamic collapse during cerebral herniation.

Cerebral herniation also activates a systemic inflammatory response; thus, anti-inflammatory properties of corticosteroid offer another potential mechanism of benefit.10 11 Intuitively, inflammation will jeopardise the suitability of organs for transplantation, but prospective cohort studies have generated conflicting results.12–14

In theory, treatment of potential organ donors with corticosteroids could improve their haemodynamic status, improve organ suitability and attenuate post-transplant organ dysfunction. The Society of Critical Care Medicine, the American College of Chest Physicians and the Association of Organ Procurement Organisations recommend high-dose corticosteroid for organ donation following neurological death.15 One recent systematic review addressing this topic concluded that existing research neither confirms nor refutes the efficacy of corticosteroid therapy for neurologically deceased donors.16 To advance this field, we applied GRADE methodology to further define the quality of current evidence, the specific limitations of previously reported trials and future research needed to clarify the effects of systemic corticosteroid therapy in neurologically deceased donors.17

Methods

This manuscript was drafted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.18

Eligibility criteria

We included published and unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCTs) enrolling of children and adults neurologically deceased potential organ donors and comparing corticosteroids to placebo, to no administration of corticosteroids or to other active treatments. We focused on the following outcomes: (1) vasopressor requirement among donors; (2) organ recovery from donors; (3) recipient graft rejection; (4) recipient graft dysfunction (using individual study definitions); and (5) adverse effects of corticosteroids in donors and recipients.

Search strategy

With the assistance of a medical librarian we searched Medline, Embase and Cochrane Central from their inception to January 2017. The Medline search strategy is found in online supplementary appendix 1. We searched conference proceedings from the International Society of Organ Donation and Procurement, American Transplant Congress, the Canadian Society of Transplantation, the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the Canadian Critical Care Forum over 5 years, as well as clinical trial registries, and we screened the reference lists of all relevant articles.

bmjopen-2016-014436supp001.pdf (43.9KB, pdf)

Eligibility review and data abstraction

Two reviewers independently screened citations and evaluated the full text of potentially eligible studies in duplicate, then abstracted data onto customised, pretested forms. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion or third party adjudication. We abstracted data pertaining to study characteristics and design, population, intervention, comparison and all clinical outcomes. We clarified missing data through email correspondence with the study author.

Assessment of risk of bias (single studies) and quality of evidence (entire body of evidence)

For each study, two reviewers evaluated the risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for RCTs.19 The risk of bias was judged to be at low risk, high risk or unclear risk with the following domains: treatment allocation, sequence generation and concealment, blinding, completeness of follow-up, selective outcome reporting and other potential sources of bias.

For each outcome, using GRADE methodology, we evaluated the quality of the entire body of evidence as high, moderate, low or very low,17 The GRADE system considers each of the following: overall risk of bias,20 imprecision in estimates of effect,21 inconsistency in findings across studies,22 indirectness (the extent to which individual study populations, interventions and outcome measurements deviate from those of interest to this review)23 and publication bias.24

Statistical analyses

We calculated chance-corrected agreement for eligibility decisions using the kappa statistic.19 Dichotomous outcomes are reported as relative risks (RRs) with their respective 95% CI for a two-sided comparison. For pooled analyses, using Revman software V.5.2 (Copenhagen), we chose a fixed effect rather than a random effect model because estimates of between-study variability are necessary for random effects estimates and are uncertain when, as in this context, there are few studies.19 If graft outcomes were measured at more than one interval we used the shortest one, assuming that steroid effects, if any, would manifest early. Heterogeneity was measured using the χ2 test for homogeneity and the Cochrane I.219 I2 greater than 50% was considered significant heterogeneity. The Egger test to address publication bias was not performed as less than 10 studies were identified.

Results

Study selection

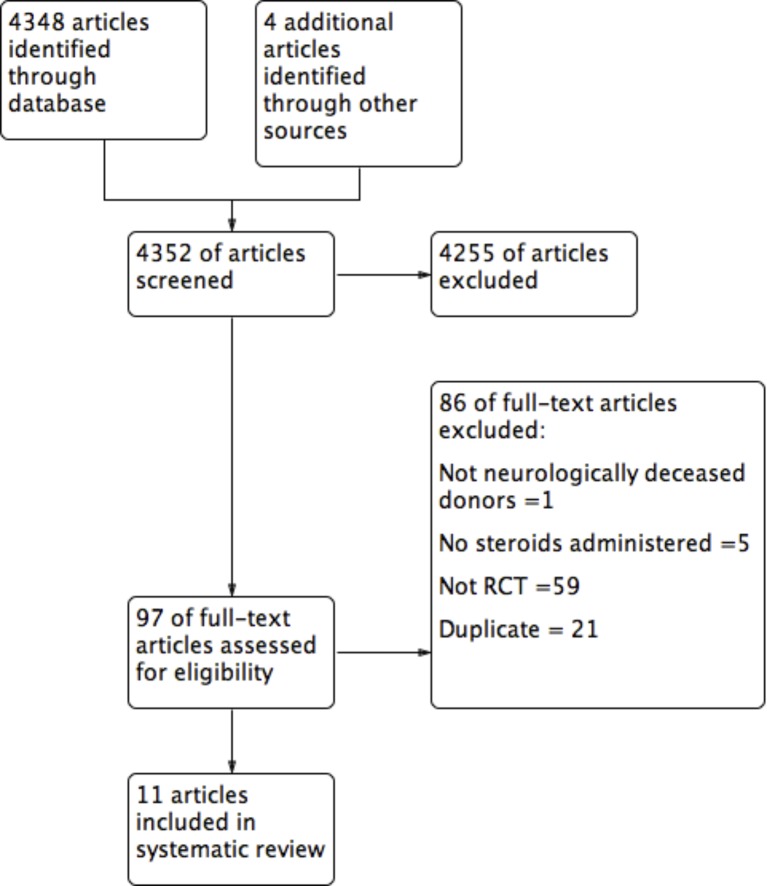

From 4352 citations, 11 were eligible (figure 1).25–35 Between-reviewer agreement at the level of full-text review was perfect (κ=1). Ten studies were published in English25 26 28–35 and one in French.27

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

Study characteristics

Five out of 11 studies explicitly mentioned Ethics Review Board approval, and fewer detailed the approach to research consent.26 28–30 35 Four publications with a focus on recipient outcomes reported separately for different organs from the same donors. Specifically, one trial was reported in two distinct publications addressing outcome related to the kidney26 and to the liver, respectively.30 A second trial of a single donor cohort reported separately on outcomes related to lung36 and heart.28

Four publications did not state the number of donors enrolled, because recipient outcomes were the focus.16 31–34 When reported, the number of donors ranged from 40 to 269, and baseline characteristics were similar between study groups.26 28–30 35 The mean donor age varied from 30 to 40 years. The most common cause for neurological death was vascular injury (eg, stroke, subarachnoid haemorrhage), followed by traumatic brain injury.26 28 35

Participants in these studies also included transplant recipients in the eight trials reporting on transplant outcomes, of whom there were 885 kidney recipients and 183 liver recipients.25 26 29–34 Their baseline characteristics were reported in only three publications.26 29 30 Groups were similar and liver recipients had favourable prognosis at baseline with a mean Model For End-Stage Liver Disease score between 14 and 16.29 30 Two studies measured graft outcome only among patients transplanted in the participating organ donation centre and excluded all recipients transplanted in other facilities.29 31

Table 1 presents the study corticosteroid regimens. A single intravenous dose of methylprednisolone was the most common regimen, ranging in dose from 1 gm to 5 gm. Three trials tested corticosteroid therapy in isolation26 29 30; two others evaluated corticosteroids in a factorial design with liothyronine,28 35 one as part of combined hormonal therapy with liothyronine27 and five placebo-controlled trials administered corticosteroids in combination with cyclophosphamide.25 31–34 The timing of corticosteroid therapy also varied across studies. Corticosteroids were administered 30 to 60 min after death declaration in one study,27 immediately after consent for organ donation in three studies28 29 35 and 3 to 8 hours before surgery in seven studies.25 26 30–34 In most studies, methylprednisolone was dosed every 24 hours.25 26 28 30–35

Table 1.

Prospective randomised trials of steroids administration in neurologically dead donors: summary of the studies

| Author, year | Donors/recipients (n) | Organs recovered | Experimental intervention | Control intervention |

| Parallel design | ||||

| Chatterjee et al 25 | 50/84 | Kidney | MTP 5 g intravenous single dose after brain death confirmation | Usual care |

| Dienst32 | NR/106 | Kidney | MTP 3 g intravenous + Cy 3 g intravenous single doses 5–8 hours before organ recovery | Usual care |

| NR/45 | MTP 5 g intravenous + Cy 3 g intravenous single doses 5–8 hours before organ recovery | Usual care | ||

| NR/29 | MTP 5 g intravenous + Cy 5 g intravenous single doses 5–8 hours. before organ recovery | Placebo | ||

| Jeffery et al 33 | NR/52 | Kidney | MTP 5 g intravenous +Cy 7 g intravenous single doses ≥4 hours before organ recovery | Usual care |

| Soulillou et al 34 | NR/62 | Kidney | MTP 5 g intravenous + Cy 5 g intravenous single doses ≥5 hours before organ recovery | Placebo |

| Corry et al 31 | NR/52 | Kidney | MTP 60 mg/kg intravenous +Cy 80 mg/kg intravenous single doses ≥5 hours before organ recovery | Usual care |

| Mariot et al 27 | 40/NR | Multi-organs | Hydrocortisone 100 mg intravenous +T3 2 μg intravenous after brain death confirmation q.30–60 min until stable CVP and SBP | Placebo |

| Kotsch et al 29 | 100/100 | Liver | MTP 250 mg intravenous+100 mg/hour intravenous after brain death confirmation | Usual care |

| Kainz et al 26 | 269/455 | Kidney | MTP 1 g single dose ≥3 hours before organ recovery | Placebo |

| Amatschek et al 30 | 8390/83 | Liver | MTP 1 g single dose ≥3 hours before organ recovery | Placebo |

| Factorial design | ||||

| Venkateswaran et al 35 | 60/NR | Lung | MTP 1 g intravenous single dose± T3 0.8 μg/kg+0.113 μg/kg/hour intravenous after brain death confirmation |

Placebo |

| Venkateswaran et al 28 | 80/NR | Heart | MTP 1 g intravenous single dose ± T3 0.8 μg/kg+0.113 μg/kg/hour intravenous after brain death confirmation |

Placebo |

CVP, central venous pressure,;Cy, cyclophosphamide; MTP, methylprednisolone; NR, not reported; SBP, systolic blood pressure; T3, liothyronin.

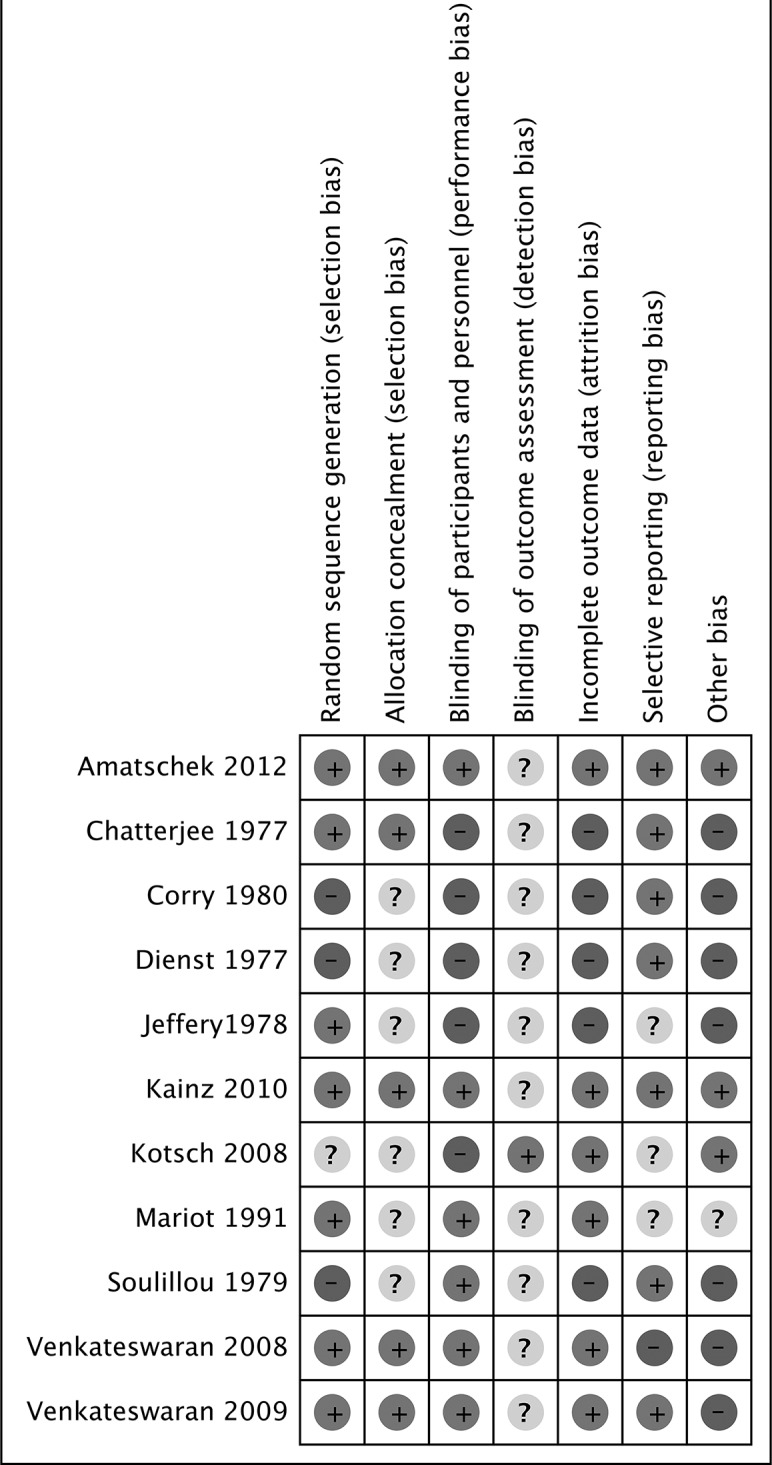

Risk of bias of individual studies

Using the Cochrane tool,19 four RCTs published after 1995 had low risk of bias.26–30 35 Earlier trials reported insufficient information to evaluate risk of bias (figure 2).25 31–34

Figure 2.

Risk of bias across the included studies.

Results of individual studies and pooled results

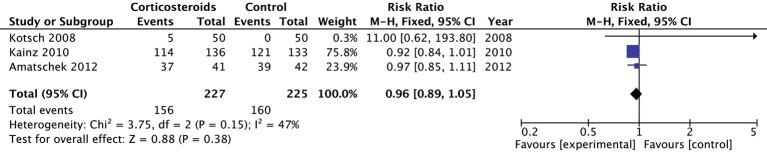

Vasopressor requirement

The three studies (n=452 donors) that reported on vasopressor administration most commonly used norepinephrine.26 29 30 Individually and when pooled, corticosteroid did not influence the rate of vasopressor use in these studies (pooled RR 0.96; 95% CI 0.89 to 1.05; moderate quality) (figure 3). The GRADE quality of evidence was rated down to moderate quality primarily because this outcome was relatively susceptible to lack of blinding (table 2).

Figure 3.

The effect of corticosteroids on vasopressor requirement.

Table 2.

GRADE profile

| Quality assessment | Quality | ||||||

| No of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |

| 3 | RCT | Serious* | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | ⨁⨁⨁ Moderate |

| 2 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious† | None | ⨁⨁⨁ Moderate |

| 3 | RCT | Not serious | Serious‡ | Not serious | Serious† | None | ⨁⨁ Low |

| 8 | RCT | Serious§ | Not serious | Serious¶,**,†† | Not serious | None | ⨁⨁ Low |

*Lack of blinding.

†Wide CI suggesting appreciable harm or benefit.

‡Large variation in effect, I2 large.

§Selection bias.

¶Different definition of the same outcome.

**Surrogate outcomes used to describe graft function.

††Cointervention.

RCT, randomised clinical trial; RR, relative risk.

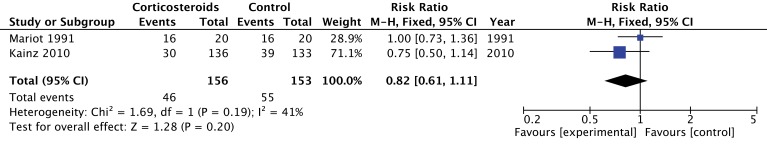

Organ recovery

Four trials evaluated organ recovery rates, but these data were analysed and reported differently across the four trials. None of the individual trials reported results suggesting increased organ recovery with steroids. Two trials (n=309 donors) reported on the number of donors who provided multiple organs,26 27 and the pooled estimate suggested no effect of corticosteroids but with a very wide CI including substantial benefit (RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.61 to 1.11; moderate quality) (figure 4). Similarly, in a factorial RCT, investigators did not demonstrate a significant increase in the number of hearts recovered or suitable for transplantation.28 In a post hoc analysis, Venkateswaran observed a decrease in the extravascular lung water index with the administration of corticosteroids; this could potentially increase the number of lungs suitable for transplantation if taken into consideration during donor care.35 For this group of outcomes, we rated down the quality of evidence to moderate because of imprecision (wide CIs) (table 2).

Figure 4.

The effect of corticosteroids on successful donation of more than one organ.

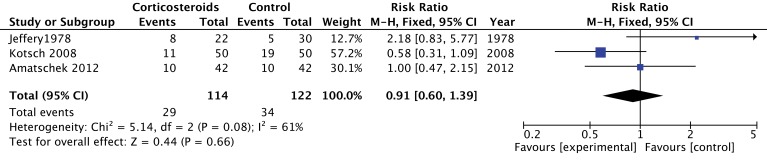

Transplant outcomes (acute graft rejection and graft function)

Three trials (n=235 recipients) studied acute graft rejection.29 30 33 Trials on acute liver rejection reported conflicting results.29 30 Amatschek et al reported similar risks of acute rejection as measured from routine biopsy specimens at 3 months.30 However, Kotsch et al obtained a lower rate of acute rejection, in the corticosteroid group, on routine biopsies within the first 6 months.29 Jeffery et al did not find a reduction in the number of acute kidney rejection with corticosteroids within the first year.33 Episodes of rejection were diagnosed on the basis of an increase in serum creatinine of more than 0.2 mg/100 mL, clinical findings and absence of alternative diagnosis explaining worsening renal function. Pooled estimates do not suggest that corticosteroids reduce the risk of acute graft rejection (RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.60 to 1.39; low confidence) (figure 5). For this group of outcomes, we rated down the overall quality of evidence to low because of inconsistency (large variation in effect between studies) and imprecision (table 2).

Figure 5.

The effect of corticosteroids on acute graft rejection at 3 months.

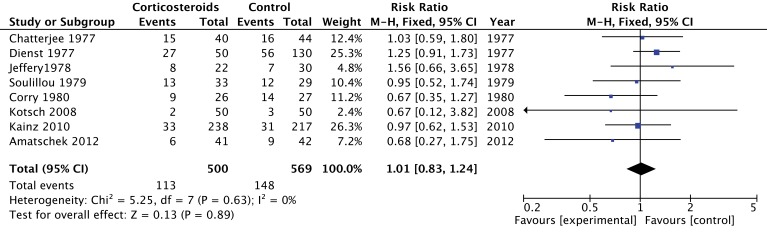

Of the eight RCTs (n=1068 recipients) that evaluated graft outcomes,25 26 29–34 two trials provided conflicting results on liver graft function. Kotsch et al reported a reduction in transaminase levels within 10 days after transplantation among patients receiving corticosteroid therapy.29 In contrast, Amatschek et al obtained similar transaminase levels within 7 days.30 Six studies compared a composite risk of one or more of the following data: creatinine level, creatinine clearance, dialysis, listed for kidney transplantation or death at different time interval.25 26 31–34 Pooled estimates, suggest no effect of corticosteroids on graft function (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.24; low confidence) (figure 6). Individual studies had high risk of bias (lack of blinding and loss to follow-up) and also provided only indirect evidence because they combined steroids with cyclophosphamide in the experimental groups. Therefore, we rated the quality of evidence for this outcome as low (table 2).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of the effect of corticosteroids on graft dysfunction.

Adverse effects

Only two studies evaluated steroid-related adverse events. Investigators reported no effect on infection rates among donors.29 Bile duct complications and hepatitis C virus reinfection following liver transplantation were similar between groups.29 30

Discussion

We systematically reviewed 11 RCTs evaluating the efficacy of corticosteroid therapy in potential organ donors with respect to clinically important outcomes among both donors and recipients. Individual studies applied a variety of dosing strategies and study outcomes, and very few suggested any difference between corticosteroid and control groups. When two or more studies measured the same outcome, pooled results did not support a treatment effect for haemodynamic stability, the number of organs recovered or transplant function. The overall quality of evidence was moderate or low for these outcomes, limiting our confidence in the results.

Strengths of our study include a comprehensive search, independent duplicate assessments of study eligibility, risk of bias and data abstraction and the pooling of results across studies where possible. Most importantly, we applied the GRADE system to rate the quality of evidence for each outcome that was addressed by more than one study. It provides a transparent assessment of our confidence in the estimates of the effect of steroids on key clinical outcomes in potential organ donors. The GRADE assessment is definitely an added value as it will provide knowledge users with evaluations of the quality of evidence underlying the use of steroids in potential organ donors. In doing so, our goal was to support guidelines for clinical care and to highlight areas for improving scientific rigour in this field. A primary limitation of this review was the inability to address differences in effect with different dosing regimens, or between organ types, based on the small number of studies to support such subgroup analyses.

Limitations of our study are largely those of the original studies and and thus the body of evidence they are contributing to is limited in the same way. Applying GRADE methodology, the overall quality of evidence was rated down as a result of the risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, inconsistency and imprecision. While the risk of bias among five studies reported in the past 20 years was relatively low, the risk of bias was uncertain for six earlier studies and may be high.37 Risk of bias was related to lack of blinding and possible selection bias in the unexplained postrandomisation exclusion of specific transplant recipients from some studies.29 31

Another limitation is that studies did not take the clustering of organs within donors (a single donor can contribute up to seven organs) into account in the analysis. To the extent that organs from some donors do systematically better than organs from other donors, the CIs presented in the studies are narrower than would be the case in an analysis that took clustering into account.

Indirectness of evidence was another important reason for rating down the overall quality of evidence. Six studies combining all steroid interventions (but not control interventions) with other hormone therapies,27 34 or with cyclophosphamide,30–33 provide only indirect evidence of the potential treatment effects of corticosteroids alone. Variation in timing of randomisation and subsequent administration of study intervention also have affected treatment effect presuming that later administration (ie, 5–8 hours before organ recovery) may be less effective. Indirectness also comes into play when evaluating studies of varied dosing regimens; it is conceivable that the apparent lack of effect overall is a result of assessing relatively helpful regimens alongside of those that are relatively harmful.

Finally, we also rated down the quality of evidence for two outcomes on the basis of imprecision. The small number of studies, patients within studies and events among patients resulted not only in wide CIs but also precluded subgroup analyses and assessment for publication bias. In summary, because the quality of evidence is low for at least two outcomes, this review cannot support strong recommendations for clinical care.

Inferences from this systematic review are also limited by varied outcomes of graft dysfunction; variable results across outcomes (apparent harm in number of organs recovered and apparent benefit in graft rejection); varied definitions for each specific term; and the inability to apply outcome definitions across organ groups, which is important in this field because one organ donor may donate kidneys, liver, lung, heart and/or pancreas or small bowel. For example, outcomes of renal graft function across studies included graft failure,25 34 graft survival31 32 and delayed graft function.26 Even the measurement of renal ‘graft failure’ was problematic for pooling across studies: Chatterjee et al defined graft failure as a composite outcome of kidney removal after transplantation, return to haemodialysis or death,25 while Soulillou et al defined graft failure as any requirement for haemodialysis or a serum creatinine level (threshold not specified) after transplantation.34 Unified outcome measures for specific organs and potentially generic outcome measures across organ groups would help to advance the science of organ donor management.

Our results are similar to those previously reported.16 38 However, we went beyond prior reviews in conducting meta-analyses and using the GRADE approach for rating the quality of evidence. Unfortunately, the moderate or low quality of evidence does not allow strong inferences about the use of steroids in these populations.15 39

Although observational studies frequently overestimate treatment effects, and these might have been confounded by surgical interventions, organ preservation techniques and transplant recipient characteristics, evidence from the current RCTs is also limited in quality. In a recent European multicentre observational study (n=259), administration of corticosteroids to deceased organ donors with a neurological determination of death was associated with a lower dose of norepinephrine (steroid group (SG)=1.18±0.92 mg/hour vs control group (CG)=1.49±1.29 mg/hour, p=0.03) and shorter duration of vasopressor support (SG=874 min vs CG=1160 min, p<0.0001).40 The incidence of delayed graft function among recipients was similar between the two groups (SG=30.8% vs CG=26.6%, p=0.14). These findings are consistent with expected effects regarding the impact of corticosteroid therapy in potential organ donors.

This systematic review highlights three types of challenges to research addressing the medical management of deceased organ donors: the scarcity of donors; practical challenges of studying therapeutic interventions and subsequent outcomes among very separate study populations, (ie, organ donors and transplant recipients); and the complexity of definitions of graft function. To better guide clinical management of deceased donors will require strong research collaborations among donation and transplantation communities at a national or even international level. Scientifically sound, large clinical trials ideally will enrol consecutive eligible deceased donors, administer a single experimental steroid therapy in a blinded fashion and measure outcomes not only among donors but also transplant recipients in a manner that allows the integration of transplant outcomes across organ groups. To achieve these goals may even require modification of current health services in donation and transplantation.

Conclusion

Current clinical trials do not identify benefits of corticosteroid therapy for deceased organ donors or their transplant recipients. The quality of this evidence is insufficient, however, to rule out the possibility of benefits or harms with respect to donation rates or transplant outcomes for any organ. In light of these results, there is no imperative to modify current recommendations for clinical care, based on observational studies, to consider corticosteroid therapy in the management of organ donors.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: FDA and EB-C: Conception of the design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafted and revised the manuscript, approved the final version to be published. AA, A-JF, FL, GG, SD and MOM: Conception of the design, acquisition and analysis of the data, drafted and revised the manuscript, approved final version to be published.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional data are available.

References

- 1. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Deceased organ donor potential in Canada. 2014. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/OrganDonorReport_ENweb.pdf.

- 2. Rosendale JD, Chabalewski FL, McBride MA, et al. . Increased transplanted organs from the use of a standardized donor management protocol. Am J Transplant 2002;2:761–8. 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20810.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dhanani S, Shemie SD. Advancing the science of organ donor management. Crit Care 2014;18:612 10.1186/s13054-014-0612-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shemie SD. Resuscitation and stabilization of the critically ill child. 1st ed, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cooper DK, Novitzky D, Wicomb WN, et al. . A review of studies relating to thyroid hormone therapy in brain-dead organ donors. Front Biosci 2009;14 70:3750 10.2741/3486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dimopoulou I, Tsagarakis S, Anthi A, et al. . High prevalence of decreased cortisol reserve in brain-dead potential organ donors. Crit Care Med 2003;31:1113–7. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000059644.54819.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gramm HJ, Meinhold H, Bickel U, et al. . Acute endocrine failure after brain death? Transplantation 1992;54:851–7. 10.1097/00007890-199211000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Howlett TA, Keogh AM, Perry L, et al. . Anterior and posterior pituitary function in brain-stem-dead donors. A possible role for hormonal replacement therapy. Transplantation 1989;47:828–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nicolas-Robin A, Barouk JD, Darnal E, et al. . Free cortisol and accuracy of total cortisol measurements in the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency in Brain-dead patients. Anesthesiology 2011;115:568–74. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31822a702f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barklin A. Systemic inflammation in the brain-dead organ donor. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53 35:425–35. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith M. Physiologic changes during brain stem death-lessons for management of the organ donor. J Heart Lung Transplant 2004;23:S217–S22. 10.1016/j.healun.2004.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murugan R, Venkataraman R, Wahed AS, et al. . Preload responsiveness is associated with increased interleukin-6 and lower organ yield from brain-dead donors. Crit Care Med 2009;37:2387–93. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a960d6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Birks EJ, Owen VJ, Burton PB, et al. . Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is expressed in donor heart and predicts right ventricular failure after human heart transplantation. Circulation 2000;102:326–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lopau K, Mark J, Schramm L, et al. . Hormonal changes in brain death and immune activation in the donor. Transpl Int 2000;13 Suppl 1:S282–S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kotloff RM, Blosser S, Fulda GJ, et al. . Management of the potential organ donor in the ICU: society of critical Care Medicine/American College of chest Physicians/Association of Organ Procurement Organizations Consensus Statement. Critical care medicine 2015;43(6):1291–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dupuis S, Amiel JA, Desgroseilliers M, et al. . Corticosteroids in the management of brain-dead potential organ donors: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2014;113:346–59. 10.1093/bja/aeu154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2011. http://handbook.cochrane.org/

- 20. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, et al. . GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence-study limitations (risk of bias). J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:407–15. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. . GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence-imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1283–93. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. . GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence-inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1294–302. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. . GRADE guidelines: 8. Rating the quality of evidence-indirectness. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1303–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Montori V, et al. . GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence—publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1277–82. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chatterjee SN, Terasaki PI, Fine S, et al. . Pretreatment of cadaver donors with methylprednisolone in human renal allografts. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1977;145:729–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kainz A, Wilflingseder J, Mitterbauer C, et al. . Steroid pretreatment of organ donors to prevent postischemic renal allograft failure: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:222–30. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mariot J, Jacob F, Voltz C, et al. . Value of hormonal treatment with triiodothyronine and cortisone in brain dead patients]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 1991;10(4:321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Venkateswaran RV, Steeds RP, Quinn DW, et al. . The haemodynamic effects of adjunctive hormone therapy in potential heart donors: a prospective randomized double-blind factorially designed controlled trial. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1771–80. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kotsch K, Ulrich F, Reutzel-Selke A, et al. . Methylprednisolone therapy in deceased donors reduces inflammation in the donor liver and improves outcome after liver transplantation: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2008;248:1042–50. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318190e70c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Amatschek S, Wilflingseder J, Pones M, et al. . The effect of steroid pretreatment of deceased organ donors on liver allograft function: a blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Hepatol 2012;56:1305–9. 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Corry RJ, Patel NP, West JC, et al. . Pretreatment of cadaver donors with cyclophosphamide and methylprednisolone: effect on renal transplant outcome. Transplant Proc 1980;12:348–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dienst SG. Statewide donor pretreatment study. Transplant Proc 1977;9:1597–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jeffery JR, Downs A, Grahame JW, et al. . A randomized prospective study of cadaver donor pretreatment in renal transplantation. Transplantation 1978;25:287–9. 10.1097/00007890-197806000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Soulillou JP, Baron D, Rouxel A, et al. . Steroid-cyclophosphamide pretreatment of kidney allograft donors. A control study. Nephron 1979;24:193–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Venkateswaran RV, Patchell VB, Wilson IC, et al. . Early donor management increases the retrieval rate of lungs for transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:278–86. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Venkateswaran RV, Dronavalli V, Patchell V, et al. . Measurement of extravascular lung water following human brain death: implications for lung donor assessment and transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;43:1227–32. 10.1093/ejcts/ezs657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Akl EA, Sun X, Busse JW, et al. . Specific instructions for estimating unclearly reported blinding status in randomized trials were reliable and valid. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:262–7. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rech TH, Moraes RB, Crispim D, et al. . Management of the brain-dead organ donor: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation 2013;95:966–74. 10.1097/TP.0b013e318283298e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shemie SD, Ross H, Pagliarello J, et al. . Organ donor management in Canada: recommendations of the forum on medical management to optimize donor organ potential. CMAJ 2006;174 32:S13–S30. 10.1503/cmaj.045131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pinsard M, Ragot S, Mertes PM, et al. . Interest of low-dose hydrocortisone therapy during brain-dead organ donor resuscitation: the CORTICOME study. Crit Care 2014;18:R158 10.1186/cc13997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014436supp001.pdf (43.9KB, pdf)