Abstract

Introduction

Pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) including urinary incontinence, faecal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse are common debilitating conditions among women in high-income countries. However, PFDs in women in low/middle-income countries (LMICs) have not been studied extensively. We aim to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available literature to determine the prevalence of, and/or risk factors for, PFDs in women in LMIC.

Methods and analysis

We will search electronic databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Maternity & Infant Care and Google Scholar for eligible studies. Inclusion criteria will be observational studies of healthy women, which have collected data using validated or non-validated tools, are published in English and were conducted in community women in LMICs, defined by the World Bank. A standardised data extraction form will be developed and piloted, based on the template of the Cochrane good practice data extraction form. All included studies will be assessed based on a risk-of-bias tool specifically developed for prevalence studies. Pooled prevalence estimates of PFDs will be generated using RevMan V.5.2.1 software. Forest plots will be generated to display the overall random-effects pooled estimates with CIs. A metaregression will be conducted to identify sources of between-study heterogeneity in the pooled prevalence estimates. We will quantify heterogeneity using the I2 measure and its CI. We will use funnel plots to detect potential reporting biases and small-study effects. We will also conduct a sensitivity analysis to verify the robustness of the study conclusions, assessing the impact of methodological quality, study design, sample size and the effect of missing data.

Ethics and dissemination

Our review is entirely based on published data. Thus, an ethics committee approval or written informed consent will not be required for this study as primary data will not be collected. The results will be disseminated by publication of the manuscript in a peer-reviewed journal and/or will be presented at relevant conferences.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42016043881.

Keywords: epidemiology, gynaecology, urogynaecology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strengths of our systematic review are that it will provide a comprehensive, objective and systematic assessment of the prevalence of, and risk factors for, pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) in low/middle-income countries (LMICs).

The results of this systematic review will help clinicians make decisions about treatment, and also provide evidence for researchers and policy-makers for early intervention for prevention of PFDs in LMICs based on identified risk factors.

The small sample sizes may affect the estimation of the prevalence of PFDs.

These quantitative analyses undertaken will not be able to identify the structural, organisational and political factors that give rise to the high prevalence of PFDS and their risk factors in LMICs.

Background

Pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) including urinary incontinence (UI), faecal incontinence (FI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), are common debilitating conditions among women across the world. In developed countries, one in every four women experience at least one or more PFDs.1 2 Evidence from these countries have established that advancing age, parity, obesity and vaginal birth are the risk factors of PFDs.2 However, little is known about PFDs among women in low/middle-income countries (LMICs).3 Furthermore, there are a paucity of studies that have comprehensively investigated all the conditions that comprise PFDs in LMICs. It is anticipated that PFDs may be more prevalent among women living in LMICs than high-income countries due to increasing life expectancy (since increasing age is a risk factor for PFDs), high parity with early marriage and childbearing, more vaginal deliveries and frequent heavy weightlifting.3–8 These factors are interrelated and are underpinned by poor nutrition and mechanical stresses. These stresses include excessive stretching from first delivery at a young age and multiple births, the need to do manual work and heavy lifting (often during and immediately after pregnancy), larger baby sizes (related to gestational diabetes mellitus) and chronic cough.3 The socioeconomic, mental and physical consequences of PFDs for women in LMICs are arguably more severe than that of women in developed countries.3 9 An earlier systematic review indicated that PFDs are among one of the significant causes of morbidity in LMICs.3 Importantly, this systematic review found substantial variation in the reported prevalences of PFDs, although the authors did not describe the reasons for the variation of prevalence reporting in detail. It was further limited by a narrow database search and data analysis. Thus, we will conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis which will aim to systematically analyse all available published articles that have documented the prevalence of, and/or risk factors for, PFDs among community-dwelling women in LMIC, and consider potential explanations for the variations in the findings.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

Two investigators (RMI and LR) will search the electronic databases of Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL and Maternity & Infant Care. Additional searches will be conducted in Google Scholar and in grey literature sources such as conference and government websites. Hand searching and retrospective searching of relevant published literature will also be undertaken. We will retrieve all English language studies that contain information on the prevalence of, and risk factors for, PFDs in community-dwelling women in LMIC, defined by the World Bank.10 The search strategy will be tested and revised as necessary across the different databases before being finalised. A database record will be maintained at each stage of the review process detailing how the search was undertaken including results of the search strategy. A senior medical librarian (LR) will assist in the final draft of the search strategy.

The search strategy will include a combination of subject terms and free text terms. These terms will be combined with ‘OR’ and ‘AND’ operators. The medical subject headings (MeSH) terms will include pelvic floor disorders, pelvic organ prolapse, genital prolapse, uterine prolapse, urinary incontinence, stress/urge/mixed urinary incontinence, faecal incontinence anal incontinence, prevalence, developing countries, resource-limit or resource-poor or low-income or lower middle-income or middle upper-income countries. All MeSH terms will be exploded where necessary. The search strategy for Medline is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy used in Ovid Medline database from 1946 to March 2017

| Number | Search terms |

| 1 | Pelvic Floor Disorders/ or Pelvic Floor/ or exp Pelvic Organ Prolapse/ |

| 2 | (pelvic floor or pelvic organ).mp. |

| 3 | ((uterine or uterus or vagina* or cervix or pelvic) adj3 prolaps*).mp. |

| 4 | ((urogenital or vault or bladder or rectal or anus) adj3 prolaps*).mp. |

| 5 | Urinary Incontinence, Urge/ or Fecal Incontinence/ or Urinary Incontinence, Stress/ or Urinary Incontinence/ |

| 6 | incontinence.mp. |

| 7 | or/1–6 |

| 8 | Developing Countries/ or exp africa/ or exp caribbean region/ or exp central america/ or latin america/ or exp south america/ or asia/ or exp asia, central/ or exp asia, southeastern/ or exp asia, western/ or exp indian ocean islands/ or pacific islands/ or exp melanesia/ or exp micronesia/ or exp west indies/ |

| 9 | (Afghanistan* or Albania* or Algeria* or Angola* or Argentina* or Armenia* or Azerbaijan* or Bangladesh* or Belarus* or Beliz* or Benin* or Bhutan* or Bolivia* or Bosnia* or Herzegovin* or Botswan* or Brazil* or Bulgaria* or Burkina* or Burundi* or Cabo Verde* or Cape Verde* or Cambodia* or Cameroon* or Central African or Chad* or China or Chinese or Colombia* or Comor* or Congo* or Costa Rica* or Cote d'Ivoir* or Ivory Coast or Cuba* or Djibouti* or Dominica* or Ecuador* or Egypt* or El Salvador* or Eritrea* or Ethiopia* or Fiji* or Gabon* or Gambia* or Georgia* or Ghana* or Grenad* or Guatemala* or Guinea* or Guyan* or Haiti* or Hondura* or Hungar* or India* or Indonesia* or Iran* or Iraq* or Jamaica* or Jordan* or Kazakhstan* or Kenya* or Kiribati* or Korea* or Kosov* or Kyrgyz Republic or Lao* or Leban* or Lesotho* or Liberia* or Libya* or Macedonia* or Madagascar* or Malawi* or Malaysia* or Maldiv* or Mali* or Marshall Island* or Mauritania* or Mauriti* or Mexic* or Micronesia* or Moldova* or Mongolia* or Montenegr* or Morocc* or Mozambi* or Myanma* or Burmese or Namibia* or Nepal* or Nicaragua* or Niger* or Nigeria* or Pakistan* or Palau* or Panama* or Papua New Guinea* or Paraguay* or Peru* or Philippines or Filipino or Romania* or Rwanda* or Samoa* or Sao Tome* or Senegal* or Serbia* or Seychell* or Sierra Leon* or Solomon Island* or Somalia* or South Africa* or Sudan* or Sri Lanka* or St Lucia* or St Vincent or Grenadines or Surinam* or Swazi* or Syria* or Tajikistan* or Tanzania* or Thai* or Timor* or Togo* or Tonga* or Tunisia* or Turk* or Turkmenistan* or Tuvalu* or Uganda* or Ukrain* or Uzbekistan* or Vanuatu* or Venezuela* or Vietnam* or West Bank or Gaza or Yemen* or Zambia* or Zimbabwe*).mp Bangladesh* or Belarus* or Beliz* or Benin* or Bhutan* or Bolivia* or Bosnia* or Herzegovin* or Botswan* or Brazil* or Bulgaria* or Burkina* or Burundi* or Cabo Verde* or Cape Verde* or Cambodia* or Cameroon* or Central African or Chad* or China or Chinese or Colombia* or Comor* or Congo* or Costa Rica* or Cote d'Ivoir* or Ivory Coast or Cuba* or Djibouti* or Dominica* or Ecuador* or Egypt* or El Salvador* or Eritrea* or Ethiopia* or Fiji* or Gabon* or Gambia* or Georgia* or Ghana* or Grenad* or Guatemala* or Guinea* or Guyan* or Haiti* or Hondura* or Hungar* or India* or Indonesia* or Iran* or Iraq* or Jamaica* or Jordan* or Kazakhstan* or Kenya* or Kiribati* or Korea* or Kosov* or Kyrgyz Republic or Lao* or Leban* or Lesotho* or Liberia* or Libya* or Macedonia* or Madagascar* or Malawi* or Malaysia* or Maldiv* or Mali* or Marshall Island* or Mauritania* or Mauriti* or Mexic* or Micronesia* or Moldova* or Mongolia* or Montenegr* or Morocc* or Mozambi* or Myanma* or Burmese or Namibia* or Nepal* or Nicaragua* or Niger* or Nigeria* or Pakistan* or Palau* or Panama* or Papua New Guinea* or Paraguay* or Peru* or Philippines or Filipino or Romania* or Rwanda* or Samoa* or Sao Tome* or Senegal* or Serbia* or Seychell* or Sierra Leon* or Solomon Island* or Somalia* or South Africa* or Sudan* or Sri Lanka* or St Lucia* or St Vincent or Grenadines or Surinam* or Swazi* or Syria* or Tajikistan* or Tanzania* or Thai* or Timor* or Togo* or Tonga* or Tunisia* or Turk* or Turkmenistan* or Tuvalu* or Uganda* or Ukrain* or Uzbekistan* or Vanuatu* or Venezuela* or Vietnam* or West Bank or Gaza or Yemen* or Zambia* or Zimbabwe*).mp. |

| 10 | (africa* or asia* or caribbean or central america* or latin america* or south america* or melanesia* or micronesia* or polynesia*).mp. |

| 11 | (resource-limit* or resource-poor or low-resource* or limited-resource* or resource-constrain* or constrain*-resource* or under-resource* or poor*-resource* or resource-scarce* or scarce*-resource* or low-income or middle-income or lowincome or middleincome or LMIC*).mp. |

| 12 | ((developing or underdeveloped or under-developed or emerging or less-developed or least-developed or less-economically developed or least-economically developed or less-affluent or least-affluent) adj (country or countries or nation or nations or region or regions or economy or economies)).mp. |

| 13 | ((developing or underdeveloped or under-developed or less-developed or least-developed) adj world).mp. |

| 14 | (third-world* or thirdworld* or 3rd-world*).mp. |

| 15 | or/8–14 |

| 16 | (et or ep).fs. |

| 17 | exp Probability/ |

| 18 | (epidemiolog* or etiolog* or prevalence or incidence or risk or factors or probabilit* or determinant* or predict*).mp. |

| 19 | 16 or 17 or 18 |

| 20 | Cross-Sectional Studies/ |

| 21 | (cross section* or disease frequency).mp. |

| 22 | 20 or 21 |

| 23 | 7 and 15 and 19 and 22 |

| 24 | exp case-control studies/ or exp cohort studies/ |

| 25 | (case-control or cohort stud*).mp. |

| 26 | 24 or 25 |

| 27 | 7 and 15 and 19 and 26 |

| 28 | 23 or 27 |

| 29 | limit 28 to english language |

This search strategy will be suitable for other electronic databases.

Inclusion criteria

Observational studies, including cross-sectional, cohort or case-control studies, studies of women with PFDs who were otherwise healthy, studies using validated or non-validated tools, published in English language and conducted in community settings, will be included. If any study compared the prevalence of PFDs in a country from LMICs with a high-income country, information only for an LMIC country will be included. Where multiple papers were generated from the same data with same outcome, only the most relevant paper will be included. However, if multiple papers were generated from the same data with different outcomes including UI, FI and POP, all papers will be included.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that evaluated treatments for PFDs, studies of women with comorbidities such as lower urinary tract symptoms, fistula, breast cancer, studies conducted to assess quality of life of women with any PFDs which did not assess the prevalence of PFDs and risk factors, will be excluded. Studies in employed women only, conducted in hospital/clinical settings, or including LMICs migrant women living in high-income countries will also be excluded. The reasons for exclusion of these studies are: the studies in hospital/clinical settings are likely to be highly selected (ie, selection bias) resulting in inaccurate estimations of the true prevalence of PFDs, professional women, especially working in the formal sector are well educated, use healthcare services and do not represent the community-dwelling women, and the prevalence of PFDs in women who migrate from LMICs to developed countries is likely to reflect the prevalence in the host country, not their country of origin. This is due to exposure to better health systems available in the host country.11–13 Editorials, letters, opinion articles, narrative or systematic reviews, brief communications, and conference abstract and posters will also be excluded. However, a full-length article will be included if any are found in conference websites.

Screening strategy

Titles and/or abstracts of studies identified using the search strategy and those from additional sources will be distributed among two review authors (RMI, JO). These team members will independently assess the eligibility of the full-text articles. Two other review authors (MNK, DMEH) will reassess all studies. Any disagreement between reviewers will be resolved through discussion with a third review author (SMH) on the study team.

Data extraction

A standardised data extraction form will be developed and piloted, based on the template of the Cochrane good practice data extraction form,14 to extract data from the selected studies. Extracted information will include study design and methods, country, study setting, participant characteristics, study outcomes, risk factors, results, conclusions and study funding sources. If essential data are missing, we will contact the authors for further information. The manuscript will be structured using the Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines.15 The data extraction form is shown in online Supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2016-015626supp001.pdf (194.8KB, pdf)

Data management

Literature search results will be stored in Endnote, and completed data extraction forms will be uploaded to Monash University faculty-allocated network storage, which will be password protected and only accessible to the reviewers. This shared network drive will facilitate the data extraction and data entry and keep a record of all review-related documents.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

To assess external and internal validity, a risk-of-bias tool will be used and developed explicitly for the systematic review of prevalence studies.16 Two review authors (MNK and DMEH) will extract data independently; inconsistencies will be identified and resolved through discussion including a third author (RMI) where necessary. The tool has 10 items: (1) national representativeness, (2) target population representativeness, (3) random selection or census undertaken, (4) minimal non-response bias, (5) data collected from subjects, (6) acceptable case definition used, (7) valid and reliable study instrument used, (8) same mode of data collection for all subjects, (9) length of the shortest prevalence period and (10) appropriateness of numerator(s) and denominator(s) for the parameter. Items 1 to 4 assess the external validity (selection and non-response bias) and items 5 to 10 assess the internal validity of the study (measurement and analysis bias). All of these items are rated high or low. Item 11, the summary assessment, evaluates the overall risk of study bias and is based on the author’s subjective judgement given responses to the preceding 10 items rated as low, moderate or high risk.

Statistical analysis

Data synthesis

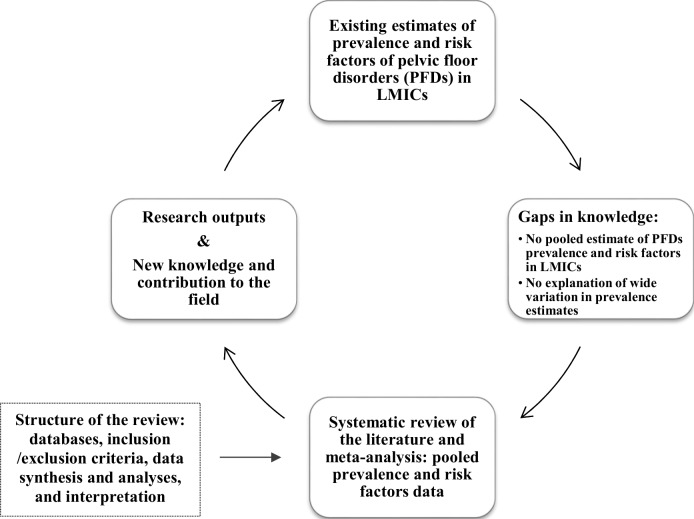

A detailed process of conducting this systematic review and data synthesis of the included studies will be undertaken, for which we have developed a conceptual framework, shown in figure 1. Pooled prevalence of PFDs will be estimated from the reported prevalence of eligible studies using RevMan V.5.2.1 software. Forest plots will be generated displaying prevalence with the corresponding 95% CIs (asymptotic Wald) for each study. The overall random-effects pooled estimate with its CI will be reported. A metaregression will be conducted to identify sources of between-study heterogeneity in the pooled prevalence (or incidence) estimates.14 17 A multivariable metaregression model will be built by adding each variable sequentially starting with the variable that shows the strongest association with PFDs prevalence in a univariate analysis. A variable will remain in the multivariable model if it will be independently associated with PFD prevalence at p≤0.10.18 Risk factors of PFDs from all included studies will be synthesised descriptively to understand the key risk factors for PFDs in LMICs. Then, metaregression of the ORs of the key risk factors will be conducted to identify the individual effects of each risk factor for PFD.19

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework. LMICs, low/middle-income countries.

Assessment of heterogeneity

To examine the magnitude of the variation between studies, we will quantify the heterogeneity by using the I2 measure and its CI.17 To assess the degree of heterogeneity, the following I2 cut-offs for low, moderate and high heterogeneity will be used: (1) between 0% to 40%: might not be important; (2) 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; (3) 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; (4) 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.20 The significance will be determined by a χ2 for Q, so a p value <0.05 will be considered significant.

Assessment of reporting biases

We will use funnel plots to detect potential reporting biases and small-study effects. The Egger method19 will be used to assess asymmetry if more than 10 studies are included in the meta-analysis.

Subgroup analysis

Stratified prevalence will be generated by the economic levels of the country (low income, lower middle income and upper middle income), by sampling methods (random and convenience) and by type of questionnaires used (validated and non-validated).

Sensitivity analysis

We will conduct a sensitivity analysis to verify the robustness of the study conclusions, assessing the impact of methodological quality, study design, sample size and the effect of missing data as well as the analysis methods on the result of this review. We will also use sensitivity analyses to investigate suspected funnel plot asymmetry due to publication bias if any.

Dealing with missing data

We will attempt to collect additional information by contacting authors of included studies with missing data. If we fail to obtain sufficient data, the study with missing data will be omitted from the data synthesis.

Discussion and conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis will provide pooled prevalence estimates of PFDs among women in LMICs. This study will also provide evidence of reasons for the substantial variation of prevalence reporting of PFDs in this context. The comprehensive and rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis technique used in this study will ensure a robust knowledge synthesis of available data. By understanding the risk factors of PFDs, this study will provide empirical evidence necessary for clinicians, researchers, policy-makers and public health stakeholders to understand the perspective, future research need, as well as policy and programming priorities for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of PFDs in LMICs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: RMI, JO, MNK, SMH, DMEH and JF contributed to the generation of ideas for systematic review. RMI, JO and LR contributed to the development of the study protocol and search strategy for the review. All the authors will contribute to the review, revision and finalisation of the search strategy. RMI prepared the first draft of the protocol. JO, MNK, SMH, DMEH, LR and JF reviewed and provided subsequent feedback on the revision of the protocol and its finalisation. All the authors critically revised the first draft for content and contributed to the final draft.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Correction notice: This paper has been amended since it was published Online First. Owing to a scripting error, some of the publisher names in the references were replaced with 'BMJ Publishing Group'. This only affected the full text version, not the PDF. We have since corrected these errors and the correct publishers have been inserted into the references.

References

- 1. Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA 2008;300:1311–6. 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, et al. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:141 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Walker GJ, Gunasekera P. Pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence in developing countries: review of prevalence and risk factors. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22:127–35. 10.1007/s00192-010-1215-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Islam RM, Bell RJ, Billah B, et al. The prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in women in Bangladesh. Climacteric 2016;19:558–64. 10.1080/13697137.2016.1240771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bodner-Adler B, Shrivastava C, Bodner K. Risk factors for uterine prolapse in Nepal. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2007;18:1343–6. 10.1007/s00192-007-0331-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gunasekera P, Sazaki J, Walker G. Pelvic organ prolapse: don't forget developing countries. Lancet 2007;369:1789–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60814-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lien YS, Chen GD, Ng SC, S-c N. Prevalence of and risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse and lower urinary tract symptoms among women in rural Nepal. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;119:185–8. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Akter F, Gartoulla P, Oldroyd J, et al. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional survey study. Int Urogynecol J 2016;27:1753–9. 10.1007/s00192-016-3038-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shrestha B, Onta S, Choulagai B, et al. Women's experiences and health care-seeking practices in relation to uterine prolapse in a hill district of Nepal. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:20 10.1186/1472-6874-14-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bank W. World Bank Country classification. 2015. Retrieved on http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups (29 Jun 2015).

- 11. Ullmann SH, Goldman N, Massey DS. Healthier before they migrate, less healthy when they return? the health of returned migrants in Mexico. Soc Sci Med 2011;73:421–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yağmur Y, Ulukoca N. Urinary incontinence in hospital-based nurses working in Turkey. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2010;108:224–7. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zarina B, Juwita S, Mn GR. Prevalence and factors associated with urinary incontinence in adult women attending Family Medicine Clinic. International Medical Journal 2005;12:303–10. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:934–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katz MH. Multivariable analysis: a primer for readers of medical research. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:644–50. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Deeks JJ, Higgins J, Altman DG. Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analyses. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Cochrane book series 2008:243–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015626supp001.pdf (194.8KB, pdf)