Abstract

Objectives

Women from the Philippines form one of the largest immigrant groups to North America. Their newborns experience higher rates of preterm birth (PTB), and separately, small-for-gestational age (SGA) birth weight, compared with other East Asians. It is not known if Filipino women are at elevated risk of concomitant PTB and severe SGA (PTB–SGA), a pathological state likely reflective of placental dysfunction and neonatal morbidity.

Methods

We conducted a population-based study of all singleton or twin live births in Ontario, from 2002 to 2011, among immigrant mothers from the Philippines (n=27 946), Vietnam (n=15 297), Hong Kong (n=5618), South Korea (n=5148) and China (n=42 517). We used modified Poisson regression to generate relative risks (RR) of PTB-SGA, defined as a birth <37 weeks’ gestation and a birth weight <5th percentile. RRs were adjusted for maternal age, parity, marital status, income quintile, infant sex and twin births.

Results

Relative to mothers from China (2.3 per 1000), the rate of PTB–SGA was significantly higher among infants of mothers from the Philippines (6.5 per 1000; RR 2.91, 95% CI 2.27 to 3.73), and those from Vietnam (3.7 per 1000; RR 1.68, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.34). The RR of PTB–SGA was not higher for infants of mothers from Hong Kong or South Korea.

Interpretation

Among infants born to immigrant women from five East Asian birthplaces, the risk of PTB–SGA was highest among those from the Philippines. These women and their fetuses may require additional monitoring and interventions.

Keywords: preterm birth, small for gestational age birthweight, ethnicity, race, immigrant, East Asia, Philippines, Filipina, Vietnam

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We conducted a population-based study of all live births in Ontario, capturing the entire population of immigrants to Ontario who gave birth between 2002 and 2011.

We accounted for some risk factors for preterm birth (PTB) and small-for-gestational age (SGA) birth weight, such as maternal age, infant sex, parity, income level and marital status.

We lacked data on skill set and level of education at immigration, immigration class and duration of residence at the time of the index birth.

We also did not possess information on parental height or weight—which may influence newborn weight.

We excluded stillbirths, who are potentially the most pathological group of fetuses and who are at risk of PTB–SGA.

Background

A pregnancy resulting in a preterm birth (PTB) and concomitant small for gestational age birth weight (SGA)—‘PTB–SGA’—is thought to be most pathological, in terms of both being due to placental dysfunction1 2 and their adverse sequelae for the newborn infant.3 4 Relative to infants born either PTB alone or SGA alone, those affected by PTB–SGA are 15 times more likely to die in the first month of life.3

PTB5 and SGA6 are each more frequent in women from the Philippines. Chronic hypertension7 and preterm onset of preeclampsia8 are each risk factors for provider-initiated (‘iatrogenic’) PTB and SGA, and they are significantly more likely to present in Filipino women than Caucasian or other East Asian women. What remains unknown is whether the risk of PTB–SGA is higher among Filipino women than their counterparts from other East Asian regions.

Herein, we performed a study in Ontario, Canada, where foreign-born individuals comprise 20% of the population and nearly 35% of all births, the highest proportion of G8 countries.9 We compared the risk of PTB–SGA among five East Asian groups, using a <5th percentile cut-off to define severe SGA, which is more predictive of adverse perinatal outcomes than a <10th percentile cut-off.10

Methods

Study sample

This population-based study comprised all live singletons and twin births in Ontario between 2002 and 2011. Data were retrieved from live birth records provided by Vital Statistics. We excluded stillbirths, as information on parental place of birth is missing for 12% of records.11 As all records were deidentified, a given woman may have contributed more than one birth during the study period, but we adjusted for parity, as described below. All pregnancy and newborn care is universally covered under Ontario’s Health Insurance Plan. Approximately 95% of Ontarian women undergo prenatal ultrasonography before 20 weeks gestation, enhancing accuracy of gestational age determined at birth.12

Exposures and outcomes

The main exposure was maternal place of birth, which was self-reported on the infant’s birth record. Each newborn was then assigned to one of five maternal East Asian birthplaces: (1) China (the referent), (2) Hong Kong, (3) South Korea, (4) Vietnam and (5) the Philippines. Women from China were chosen as the reference group as they are the largest East Asian immigrant group in Ontario9 and have relatively lower rates of PTB and SGA.5 6 The main study outcome was PTB–SGA, defined as PTB <37 weeks and severe SGA <5th percentile.10 The birth weight percentile curves used herein were those for all live births in Ontario, and were not otherwise customised by maternal ethnicity or other factors (6,11). Reasons for the latter were that we restricted our cohort solely to births of East Asian mothers, and that defining severe SGA at <5th percentile is a cut-off that reflects pathological intrauterine growth restriction (10). Secondary outcomes were PTB without severe SGA, and severe SGA without PTB.

Data analysis

We used modified Poisson regression models to estimate relative risks (RR) and 95% CI for each study outcome in association with maternal place of birth. RR were adjusted for maternal age (<20, 20–34, ≥35 years), parity (0, 1, 2, 3, ≥4), marital status (married/common law, unmarried, unknown), residential income quintile (Q1 (lowest) to Q5 (highest), unknown),13 infant sex and twin births. The ‘unknown ‘categories of marital status and residential income quintile were included in the multivariable models. However, for maternal age and parity, we excluded those pregnancies with ‘unknown’ status, given the rarity of this situation and the need to allow model convergence, accordingly.

For the main outcome of PTB–SGA, we additionally performed stratified analyses to examine potential effect measure modification by parity (nulliparous vs parous) and by maternal age (<35 years vs ≥35 years).

As the study focus was to compare immigrants from different East Asian birthplaces, Canadian-born mothers were not included in main regression models. However, for comparative purposes, we described the characteristics of Canadian-born mothers and their infants, and ran an additional analysis of the main model of PTB–SGA with Canadian-born mothers as the referent.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute). Ethics approval was provided by the Research Ethics Board of St Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario.

Results

Between 2002 and 2011, there were 956 994 live-born singleton or twin births in Ontario to mothers born in Canada, China, Hong Kong, South Korea, Vietnam or the Philippines. We excluded 893 infants (0.09%) whose gestational age was <24 or>42 weeks and 487 infants (0.05%) whose gestational age at birth was unknown. We further excluded infants whose birth weight was unknown (n=31) or <500 g (n=55), whose sex was unknown (n=1) or in which maternal age (n=108) or parity (n=239) were unknown.

The final cohort comprised 42 517 births to mothers from China, 5618 from Hong Kong, 5148 from South Korea, 15 297 from Vietnam and 27 946 from the Philippines. The remainder were newborns of mothers from Canada (table 1). In general, mothers from East Asia tended to be older than Canadian-born women but of similar parity. Filipina-born mothers were similar in age, marital status and income to Chinese-born mothers (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of live singleton and twin births and their mothers, who delivered at 24 to 42 weeks’ gestation in Ontario, 2002 to 2011

| East Asian maternal place of birth | ||||||

| Characteristic | China (n=42 517) |

Hong Kong (n=5618) |

South Korea (n=5148) |

Vietnam (n=15 297) |

Philippines (n=27 946) |

Canadian maternal country of birth (n=858 654) |

| Of the mother | ||||||

| Mean (SD) age, years | 32.3 (4.7) | 33.5 (4.3) | 32.1 (3.9) | 31.4 (4.8) | 32.6 (5.4) | 29.5 (5.5) |

| Age category, years | ||||||

| <20 | 81 (0.2) | 17 (0.3) | 7 (0.1) | 68 (0.4) | 353 (1.3) | 38 920 (4.5) |

| 20–34 | 28 163 (66.2) | 3346 (59.6) | 3801 (73.8) | 11 178 (73.1) | 17 042 (61.0) | 662 500 (77.2) |

| ≥35 | 14 273 (33.6) | 2255 (40.1) | 1340 (26.0) | 4051 (26.5) | 10 551 (37.8) | 157 234 (18.3) |

| Parity | 1 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) |

| 0 | 21 160 (49.8) | 3104 (55.3) | 2552 (49.6) | 6809 (44.5) | 12 698 (45.4) | 389 635 (45.4) |

| 1 | 17 836 (42.0) | 2023 (36.0) | 1990 (38.7) | 5984 (39.1) | 9905 (35.4) | 304 847 (35.5) |

| 2 | 3012 (7.1) | 413 (7.4) | 505 (9.8) | 1896 (12.4) | 3921 (14.0) | 111 814 (13.0) |

| 3 | 410 (1.0) | 59 (1.1) | 78 (1.5) | 470 (3.1) | 1047 (3.7) | 33 591 (3.9) |

| ≥4 | 99 (0.2) | 19 (0.3) | 23 (0.4) | 138 (0.9) | 375 (1.3) | 18 767 (2.2) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/common law | 36 668 (86.2) | 5205 (92.6) | 4829 (93.8) | 10 899 (71.2) | 22 304 (79.8) | 578 402 (67.4) |

| Unmarried | 3764 (8.9) | 236 (4.2) | 107 (2.1) | 2388 (15.6) | 3125 (11.2) | 132 698 (15.5) |

| Unknown | 2085 (4.9) | 177 (3.2) | 212 (4.1) | 2010 (13.1) | 2517 (9.0) | 147 554 (17.2) |

| Residential income quintile (Q) | ||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 12 391 (29.1) | 512 (9.1) | 1183 (23.0) | 4091 (26.7) | 8992 (32.2) | 150 194 (17.5) |

| Q2 | 11 092 (26.1) | 1119 (19.9) | 976 (19.0) | 3454 (22.6) | 6770 (24.2) | 159 370 (18.6) |

| Q3 | 7328 (17.2) | 1193 (21.2) | 1021 (19.8) | 3336 (21.8) | 5445 (19.5) | 177 349 (20.7) |

| Q4 | 6236 (14.7) | 1487 (26.5) | 1021 (19.8) | 2526 (16.5) | 4183 (15.0) | 192 726 (22.4) |

| Q5 (highest) | 3971 (9.3) | 1148 (20.4) | 852 (16.6) | 1387 (9.1) | 2342 (8.4) | 166 173 (19.4) |

| Unknown | 1499 (3.5) | 159 (2.8) | 95 (1.8) | 503 (3.3) | 214 (0.8) | 12 842 (1.5) |

| Of the newborn infant | ||||||

| Female sex | 20 519 (48.3) | 2703 (48.1) | 2444 (47.5) | 7381 (48.3) | 13 491 (48.3) | 418 726 (48.8) |

| Twin births | 901 (2.1) | 156 (2.8) | 105 (2.0) | 286 (1.9) | 554 (2.0) | 29 075 (3.4) |

All data are presented as a number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

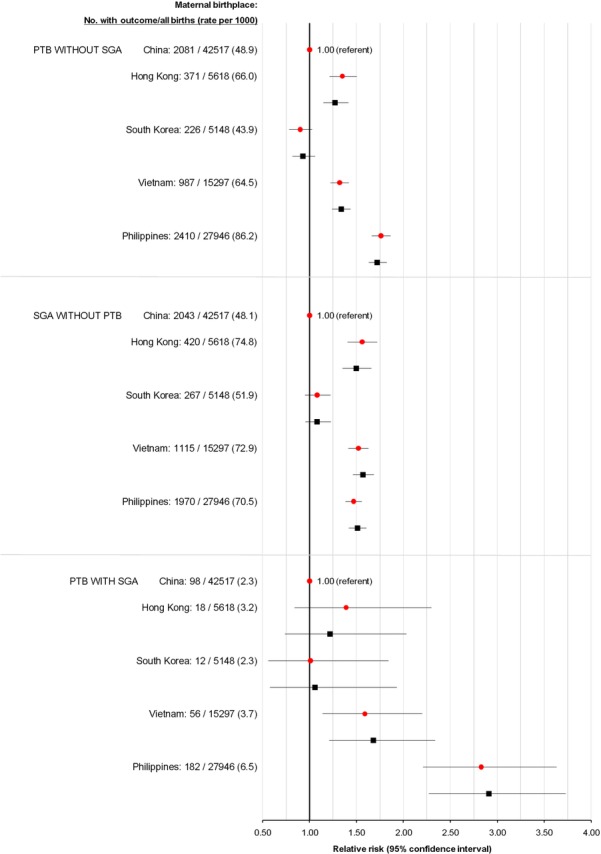

Compared with mothers from China, the outcomes of PTB without severe SGA and severe SGA without PTB were significantly more prevalent among newborns of mothers from Hong Kong, Vietnam and the Philippines but not South Korea (figure 1). The more severe outcome of PTB–SGA was significantly more common among newborns of mothers from Vietnam (3.7 per 1000; adjusted RR (aRR) 1.68, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.34), compared with those of mothers from China (2.3 per 1000) (figure 1). For newborns of Filipino women, the rate (6.5 per 1000) and aRR (2.91, 95% CI 2.27 to 3.73) were even higher (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rate and crude (red circles) and adjusted (black squares) relative risk of PTB without severe SGA (upper), SGA without PTB (middle) and PTB with SGA (PTB–SGA (lower)) for live-born infants of East Asian-born mothers. Relative risks were adjusted for maternal age (<20, 20–34, ≥35 years), parity (0, 1, 2, 3, ≥4), marital status (married/common law, unmarried, unknown), residential income quintile (Q1 (lowest) to Q5 (highest), unknown), infant sex and twin birth. PTB, preterm birth; SGA, small for gestational age.

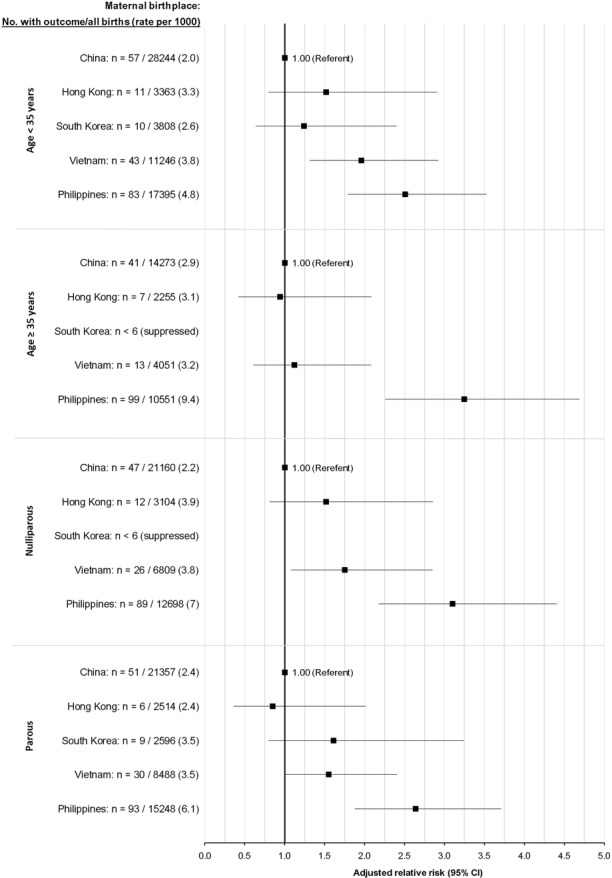

In our stratified analyses, the risk of PTB–SGA was somewhat more pronounced among Filipino women aged ≥35 years or older (figure 2, upper) and those who were nulliparous (figure 2, lower).

Figure 2.

Rate and adjusted relative risk of PTB with severe SGA—PTB–SGA—for live-born infants of East Asian-born mothers, stratified by age (upper two plots) and parity (lower two plots). Relative risks were adjusted for maternal age (<20, 20–34, ≥35 years), parity (0, 1, 2, 3, ≥4), marital status (married/common law, unmarried, unknown), residential income quintile (Q1 (lowest) to Q5 (highest), unknown), infant sex and twin birth. PTB, preterm birth; SGA, small for gestational age.

Limiting the dataset to singleton births did not appreciably change the RR of PTB–SGA, even heightening the RR among Filipino women (see online supplementary file 1).

bmjopen-2016-015386supp001.pdf (134KB, pdf)

Rerunning the main model of PTB–SGA, with Canadian-born mothers as the referent, showed that only the offspring of Filipino mothers were at higher risk of PTB–SGA (see online supplementary file 2).

bmjopen-2016-015386supp002.pdf (126.1KB, pdf)

Discussion

Newborns of mothers from the Philippines were most vulnerable to PTB–SGA, especially among women ≥35 years who comprised 37% of all Filipino mothers and in whom the rate of PTB–SGA was nearly 1%.

Strengths and weaknesses

We evaluated nearly 100 000 live births among women born in five East Asian regions, which are major sources of immigrants to Ontario, in a setting of universal healthcare. Infants of Chinese-born women provided an ideal reference group, as China is the largest source of immigrants from East Asia to Ontario, and they have a low incidence of adverse neonatal and maternal outcomes.5 14 The <5th percentile cut-off used to define severe SGA reflects a degree of smallness that is more likely to be pathological rather than constitutional.10 Still, the outcome of PTB–SGA was not rare—occurring in 6.5 per 1000 infants of Filipino mothers. Through our analysis, we were able to account for some previously noted risk factors for PTB or SGA, such as maternal age, infant sex, parity, income level and marital status.

A limitation of this study was the exclusion of stillbirths, who are potentially the most pathological group of fetuses and who are at risk of PTB–SGA.15 16 We lacked data on factors associated with the so-called ‘healthy immigrant effect’,17 such as skill set and level of education at immigration, immigration class and duration of residence at the time of the index birth. We also did not possess information on parental height or weight—which may influence newborn weight—or conditions such as maternal chronic hypertension and diabetes mellitus or maternal behavioural risk factors (eg, smoking, drug or substance use). However, Filipino women of reproductive age living in Canada have a rate of smoking under 6.0%, comparable to that of their East Asian counterparts,7 and the corresponding rate in pregnancy would be expected to be even lower. The body mass index (BMI) of Filipino women of reproductive age tends to be higher than that of other East Asians.7 It is unlikely that access to prenatal care explains the current findings, as 88% of Filipino women and 85% of other East Asian women in Canada have a regular medical doctor.7 Finally, we could not identify the specific causes of PTB–SGA from the dataset used herein, which is certainly worthy of a study focused on differentiating spontaneous versus provider-initiated PTB. Thus, while our findings represent a large cohort of immigrants to Canada, they may not be generalisable to other countries with a large number of first-generation or second-generation East Asian immigrants.

Meaning of the study for clinicians and policy-makers

In 2011, 13.1% of all newcomers to Canada were from the Philippines.9 Women from the Philippines were at exceptionally high risk of PTB–SGA, peaking at nearly 1% among those aged 35 years and older, and who represent one-third of all Filipino women giving birth in Ontario. From a public health perspective, there is value in reducing the incidence of PTB–SGA, and such a strategy might start with Filipino women. For healthcare providers—including family doctors, obstetricians or midwives—the priority would be to address risk factors in these women. This can be done at several time points—before becoming pregnant, during pregnancy and at the time of delivery. Before pregnancy, providers can counsel Filipino women, especially those women older than 35 years of age, on the possibility of adverse perinatal outcomes. During the pregnancy, risk factors can be identified and managed. Chronic hypertension is one important risk factor for both PTB18 and SGA,19 20 and also for pre-eclampsia,21 which can give rise to PTB–SGA.22 Chronic hypertension is highly prevalent among Filipino women in Ontario7; therefore, efforts to regulate blood pressure and prevent pre-eclampsia may help reduce the risk of PTB–SGA among Filipino women and also those from Vietnam. Such interventions include aspirin23–25 and early pregnancy blood pressure assessments.26 By the third trimester of pregnancy, periodical sonographic assessment of fetal growth and well-being should be considered, as there is evidence that this helps the clinician identify SGA infants and balance the risks of prematurity against a worsening intrauterine environment.27 28

Unanswered questions and future research

What differentiates a Filipino woman from another East Asian woman is her heightened risk of having a live born affected by PTB–SGA, a severe pathological state. For immigrant Filipino women, appropriate cautionary measures should be taken to ensure that mother and baby remain healthy throughout the pregnancy and delivery. Future research should aim to identify specific and ideally modifiable traits of Filipino women that increase the risk of PTB–SGA during pregnancy. Specifically, it would be worthwhile to evaluate whether the rates of smoking, high BMI or other socioeconomic indicators differ between pregnant Filipino women and those women from other East Asian birth places.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EB and JR contributed to the study concept, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of manuscript, manuscript revision and approval of final version. AP contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of manuscript, manuscript revision and approval of final version. JJ contributed to the interpretation of the data and approval of final version.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). JGR holds a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Chair in Reproductive and Child Health Services and Policy Research, cofunded by the SickKids Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was granted by the Research Ethics Board of St Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are not available for public access.

References

- 1. Salafia CM, Minior VK, Pezzullo JC, et al. . Intrauterine growth restriction in infants of less than thirty-two weeks' gestation: associated placental pathologic features. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;173:1049–57. 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91325-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM. Ischemic placental disease: epidemiology and risk factors. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;159:77–82. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Katz J, Lee AC, Kozuki N, et al. . Mortality risk in preterm and small-for-gestational-age infants in low-income and middle-income countries: a pooled country analysis. Lancet 2013;382:417–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60993-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1500–7. 10.1056/NEJM200005183422007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Park AL, Urquia ML, Ray JG. Risk of preterm birth according to maternal and paternal country of birth: a population-based study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37:1053–62. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)30070-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Souza LR, Urquia ML, Sgro M, et al. . One size does not fit all: differences in newborn weight among mothers of Philippine and other East Asian origin. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012;34:1026–37. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35432-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fuller-Thomson E, Rotermann M, Ray JG. Elevated risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes among Filipina-Canadian women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010;32:113–9. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34424-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ray JG, Wanigaratne S, Park AL, et al. . Preterm preeclampsia in relation to country of birth. J Perinatol 2016;36:718–22. 10.1038/jp.2016.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Immigration and Ethnoculutural Diversity in Canada: Statistics Canada. 2013. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.cfm (accessed 3 Aug 2016).

- 10. Zhang J, Mikolajczyk R, Grewal J, et al. . Prenatal application of the individualized fetal growth reference. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:539–43. 10.1093/aje/kwq411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bartsch E, Park AL, Pulver AJ, et al. . Maternal and paternal birthplace and risk of stillbirth. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37:314–23. 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30281-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Schull MJ, et al. . Results of the Recent Immigrant Pregnancy and Perinatal Long-term Evaluation Study (RIPPLES). CMAJ 2007;176:1419–26. 10.1503/cmaj.061680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilkins R, Peters PA. Postal code conversion file, PCCF+ version 5K Health Analysis Division: Statistics Canada. 2012. http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/olc-cel/olc.action?ObjId=92-154-X&ObjType=2&lang=en&limit=0.

- 14. Mukerji G, Chiu M, Shah BR. Gestational diabetes mellitus and pregnancy outcomes among Chinese and South Asian women in Canada. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;26:279–84. 10.3109/14767058.2012.735996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, et al. . Major risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011;377:1331–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62233-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mullan Z, Horton R. Bringing stillbirths out of the shadows. Lancet 2011;377:1291–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60098-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Insights into the 'healthy immigrant effect': health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1613–27. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tucker CM, Berrien K, Menard MK, et al. . Predicting Preterm Birth Among Women Screened by North Carolina's Pregnancy Medical Home Program. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:2438–52. 10.1007/s10995-015-1763-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Catov JM, Nohr EA, Olsen J, et al. . Chronic hypertension related to risk for preterm and term small for gestational age births. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:290–6. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817f589b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zetterström K, Lindeberg SN, Haglund B, et al. . Chronic hypertension as a risk factor for offspring to be born small for gestational age. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2006;85:1046–50. 10.1080/00016340500442654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bartsch E, Medcalf KE, Park AL, et al. . Clinical risk factors for pre-eclampsia determined in early pregnancy: systematic review and meta-analysis of large cohort studies. BMJ 2016;353:i1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2005;365:785–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71003-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lausman A, Kingdom J. Maternal fetal medicine committee. Intrauterine growth restriction: screening, diagnosis, and management. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35:741–8. 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30865-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O'Conner E, et al. . Low-Dose aspirin for the Prevention of Morbidity and Mortality from Preeclampsia: a Systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville(MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health (UK). Hypertension in Pregnancy: The Management of Hypertensive Disorders During Pregnancy National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. London: RCOG Press, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuc S, Koster MP, Franx A, et al. . Maternal characteristics, mean arterial pressure and serum markers in early prediction of preeclampsia. PLoS One 2013;8:e63546 10.1371/journal.pone.0063546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hecher K, Bilardo CM, Stigter RH, et al. . Monitoring of fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction: a longitudinal study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2001;18:564–70. 10.1046/j.0960-7692.2001.00590.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nguyen PH, Addo OY, Young M, et al. . Patterns of fetal growth based on ultrasound measurement and its relationship with small for gestational age at birth in rural Vietnam. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2016;30:256–66. 10.1111/ppe.12276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015386supp001.pdf (134KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015386supp002.pdf (126.1KB, pdf)