Abstract

Progressive fibrosis of the interstitium is the dominant final pathway in renal destruction in native and transplanted kidneys. Over time, the continuum of molecular events following immunological and non-immunological insults lead to interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) and culminate in kidney failure. We hypothesize that these insults trigger changes in DNA methylation (DNAm) patterns which in turn could exacerbate injury and slow down the regeneration processes, leading to fibrosis development and graft dysfunction. Herein, we analyzed biopsy samples from kidney allografts collected after 24-months post transplantation and used an integrative multi-omics approach to understand the underlying molecular mechanisms. The role of DNAm and microRNAs on the graft gene expression was evaluated. Enrichment analyses of differentially methylated CpG sites were performed using GenomeRunner. CpGs were strongly enriched in regions that were variably methylated among tissues implying high tissue specificity in their regulatory impact. Corresponding to this methylation pattern, gene expression data were related to immune response (activated state) and nephrogenesis (inhibited state). Preimplantation biopsies showed similar DNAm patterns to normal allograft biopsies at 2-years post-transplantation. Our findings demonstrate for the first time a relationship among epigenetic modifications and development of interstitial fibrosis, graft function, and inter-individual variation on long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Interstitial fibrosis, Tubular atrophy, Transplantation, Renal allograft, DNA methylation, Integrative approach, Epigenetics, miRNA, Gene expression

Introduction

Although kidney transplantation (KT) is the preferred treatment for patients with end stage of renal disease (ESRD), the long-term survival rate of the renal allograft remains a challenge (1–10), mainly as consequence of death with a functioning graft and intrinsic chronic renal allograft dysfunction (or CRAD) (1–5,11). CRAD is time-dependent, progressive, irreversible, and currently diagnosed late in its course. Its pathogenesis is multifactorial and comprises both immune and non-immune mechanisms with successive insults to the graft culminating in interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) and progressive loss of graft function. Its pathogenesis has not been fully elucidated and existing therapy is not effective in improving renal transplant function.

Studies aiming at understanding progression to IFTA post-KT have mostly been limited to single dimensional approaches. In order to better understand the injury mechanisms occurring in KT, integration of molecular measurements of large data sets from different experiments and technologies would be required. Evaluation of tissue graft DNA methylation (DNAm) patterns- and its effect on molecular pathways leading to decrease in graft function has not been done yet. Methylation of DNA at cytosine bases of the CpG rich sites prevents downstream gene expression (GE) either by inhibition of binding of transcription factors directly or by recruiting proteins like histone deacetylases (12,13). DNAm patterns in normal tissue development and in disease phenotypes have long been established (14,15). There are also an increasing number of reports showing the impact of DNAm in renal diseases (16–19). Environmental factors influence DNAm patterns which leads to change in GE profiles and cause disease phenotype downstream (20,21). For instance, the role of DNAm in development of regulatory T cells, B cell maturation, B cell activation, and macrophage polarization has been reported (22–24). The inflammatory environment has been found to influence DNAm patterns/epigenome (25,26). Thus, chronic diseases may set the stage for a chain reaction of events where epigenetic modifications and long-lasting organ insults influence each other leading to disease progression. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to study and understand these systemic modifications occurring during disease progression which might not be exclusive to fibrosis development in kidneys but likely of importance for other solid organs as well.

DNAm studies in chronic kidney disease (CKD) show the role of methylation in abnormal wound healing process that results in fibrogenesis (16,27–29). In transplantation, only a few studies were done addressing DNAm changes (25,27,29–31). However, these studies mostly used reductionist systems limited to one or few gene sets and were limited to mouse and cell-based models. Long-term graft deterioration can be considered a variant of CKD (32), sharing common events of decline in kidney function and renal fibrosis. Oxidative stress may be the mechanism responsible for toxic effects and IFTA caused by immunosuppressive drugs (33). Furthermore, oxidative stress is one of the most important components of ischemia/reperfusion process after KT and increases with graft dysfunction. Also, the fundamental mechanism of interstitial fibrosis is the imbalance of extracellular matrix metabolism and abnormal accumulation via interaction of various inflammatory cytokines. A relationship between inflammation and fibrosis progression has been previously described. Herein, we hypothesize that the renal allograft is in an environment where oxidative stress and unresolved inflammatory setting trigger changes in DNAm patterns of the allograft which in turn could exacerbate injury and slow down the recovery and healing processes, eventually leading to fibrosis development and graft dysfunction. However, understanding such complex, multifactorial pathogenetic process requires a multidimensional systems approach. We thereby incorporated integrated analyses of tissue-specific global kidney graft DNAm, downstream GE and miRNA pattern changes in samples with IFTA and declining graft function, stable functioning allografts without fibrosis, and pre-transplant donor kidney biopsies. Using this approach, a critical role of epigenetic modifications impacting molecular pathways leading to progression to IFTA with subsequent graft loss in graft biopsies from KT recipients was identified.

Methods

Enrolled cohort

A total of 99 protocol biopsy samples from 95 kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) of deceased donor grafts were included in the study. Patients were enrolled between May 2004 and November 2010 as part of a prospective multi-center study (UVA 14849, VCU#HM11454). Sample details are given in supplementary methods section and Table-1. Centralized histological evaluation was performed by two blinded pathologists using Banff classification (34–38). Pathologist’s interpretation was determined when critical disagreement in diagnosis was observed, following the algorithm reported by Elmore et al (39).

Study design

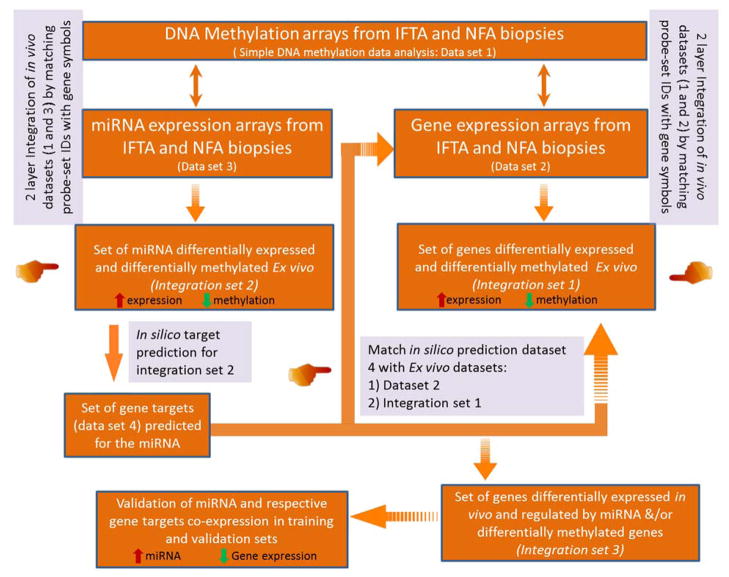

The overview of study and analysis work flow is shown in Fig 1. Two sets of protocol kidney biopsy samples were analyzed, one post-transplant (≥ 24 months Post-KT; n = 59) and one pre-transplant (Pre-KT; n = 40). Each set included one arm of transplants with normal function and non-fibrotic tissue (eGFR slope over time stable and not declining, IFTA ci ≤ 1, ct ≤ 1; NFA samples (n =18, training set; n =11, validation set)) and one arm with declining function and fibrotic tissue (eGFR slope over time negative, IFTA ci ≥ 2, ct ≥ 2; IFTA, (n = 18, training set; n = 12; validation set)). The eGFR slope was calculated from time of transplantation to time of biopsy retrieval using values at time points described in the Table 1. Five sets of paired biopsies (Pre-KT and 24-months post-KT, with 3 progressing to IFTA, 2 keeping normal graft function) were included. The set of Pre-KT samples was classified into 20 IFTA samples and 20 NFA samples according to their histology in biopsies taken >24 months after transplantation and the corresponding eGFR slope calculated over this post-transplant period.

Figure 1. Study design.

A total of 99 biopsy samples from kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) were used for the study. The study design is classified into 3 main sections. Section A: DNA was isolated from 36 KTRs at ≥ 24 months post-KT and 40 pre-transplant biopsy samples were used for running methylation arrays. Differentially methylated (Dme) CpG sites (FDR<0.01, ) were identified between patient groups (NFA (n=18) vs. IFTA (n= 18). Dme CpG sites were mapped and overall analyzed using directionality of methylation for evaluating overall affected genes and associated pathways. DNA methylation from pre-implantation biopsies (including 5 paired samples (3 IFTA and NFA after 24 months post-KT) and NFA and IFTA DNA methylation data were used for unsupervised cluster analysis. Two datasets resulted from this initial step: dataset A and dataset B, respectively. Section B: 21 post-KT samples for which paired GE and miRNA data were available were used for integration analysis. The section A experiments resulted in datasets 1, 2 and 3 from methylation (Human Infinium 450K arrays), GE (GeneChip® HG- U133A v2.0) and miRNA (GeneChip® miRNA v4.0 array) expression arrays respectively, which were further used for integration analysis as shown in Figure 5 of the manuscript. Section C: Following the integration analysis genes from important pathways/miRNA:mRNA interactions were validated using co-expression analysis in an independent set of 23 samples.

Table 1.

Clinical information of enrolled cohort

| Time of Biopsy: | Pre-implant Biopsies | Post-transplant Biopsies (≥ 24 months) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Category: | Progressors to IFTA | Non Progressors to IFTA | pvalue | NFA | IFTA | pvalue | ||

| Number | n = 20 | n = 20 | n = 29 | n = 30 | ||||

| Donor characteristics: | Age | years ± SD | 50.2 ± 10.4 | 52.4 ± 13.3 | 0.63 | 41.3 ±14.3 | 47.0625±10.8a | 0.58 |

| Race | % Caucasian | 65 | 705 | 0.49 | 85 | 87b | 0.51 | |

| % AA | 35 | 30 | 15 | 13 | ||||

| % Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Gender | %Male | 70.0 | 73.7 | 0.12 | 68 | 72c | 0.15 | |

| Donor type | % ECD | 60 | 40 | 0.17 | 27.5 | 33.3c | 0.42 | |

| DGF | % DGF | 60 | 45 | 0.26 | 31 | 30c | 0.58 | |

| Last creatinine | mg/dL ± SD | 1.19 ± 0.53 | 1.20 ± 0.90 | 0.93 | 1.35 ± 0.59 | 1.35 ± 0.65a | 0.83 | |

| Recipient Characteristics: | Age | years ± SD | 55.7 ± 9.8 | 55.3 ± 12.5 | 0.58 | 47.85±13.83 | 49.15±12.86a | 0.60 |

| Race | % Caucasian | 20 | 25 | 0.49 | 65 | 60b | 0.53 | |

| % AA | 80 | 75 | 24 | 29 | ||||

| % Other | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Gender | % Male | 50 | 75 | 0.09 | 72.4 | 66.7c | 0.42 | |

| Cause for ESRD | % HTN | 55 | 63.1 | 0.34 | 50 | 48b | 0.54 | |

| % Diabetes | 20 | 42.1 | 22 | 19 | ||||

| % other | 35 | 15.8 | 38 | 33 | ||||

| Acute rejection | %, first year | 3.4 | 3.8 | 0.78 | 4.2 | 3.8c | 0.67 | |

| eGFR (biopsy time) | mL/min/1.73m2 | NA | NA | NA | 57.9±4.5 | 38.0±8.5a | <0.001 | |

| eGFR at 1mo | 68.8 ± 20.9 | 57.1 ± 39.1 | 0.32 | |||||

| eGFR at 3mo | 63.7 ± 13.4 | 58.5 ± 27.8 | 0.17 | |||||

| eGFR at 6mo | 75.5 ± 10.19 | 55.4 ± 50.1 | <0.01 | |||||

| eGFR at 9mo | 76.9 ± 15.7 | 45.4 ± 34.9 | <0.01 | |||||

| eGFR at 12mo | 75.6 ± 12.8 | 41.2 ± 21.7 | <0.01 | |||||

| eGFR at 15mo | 77.9 ± 13.3 | 55.2 ± 47.7 | <0.01 | |||||

| eGFR at 24 mo | 69.3 ± 16.6 | 28.5 ± 12.7 | <0.001 | |||||

| Last known eGFR | 71.0 ± 21.7 | 18.5 ± 16.2 | <0.001 | |||||

Statistical significance was calculated using t test.

Statistical significance was calculated using chi-square test.

Statistical significance was calculated using Fisher exact test.

(NS: not significant, N/A: not applicable). Abbreviations: AA, African-American; ECD, Extended Criteria Donor; DGF, Delayed Graft Function; ESRD, End Stage Renal Disease; HTN, Hypertension.

DNA/RNA arrays

DNAm arrays were done using Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip array (Illumina, San Diego, CA). MiRNA expression and GE analyses were done using GeneChip® miRNA v4.0 array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), and GeneChip® HG-U133A v2.0 (Affymetrix) (GEO accession number GSE53605) respectively. (See, Supplementary Methods for further description).

Data Analysis and quality control

Bioconductor packages minfi (scanned methylation arrays) and oligo (scanned miRNA and GE) were used for initial procurement of respective data (40–42). The details of the analyses and quality control parameters are furnished in supplementary methods section.

For each of the above three analyses, the groups of interest, IFTA and NFA, were compared using a moderated t-test using the limma (43) Bioconductor package (44). Probe sets were considered significant when the false discovery rate due to Benjamini and Yekutieli (45) was <0.01. For methylation arrays an additional filter for CpG sites having a was used.

Enrichment analysis for methylation data

The enrichment analyses were performed using GenomeRunner (46) to test whether up/downregulated CpG sites, both in the gene and non-gene regions, were enriched in any specific class of (epi)genomic annotations, as compared with randomly selected CpG sites from all 450K CpGs on the Illumina Infinium array.

Integrative analysis

Initially, the GE data (Dataset 2) and the miRNA data (Dataset 3) were separately integrated with DNAm data (Dataset 1) by matching the gene symbol of each significant probeset to the UCSC Reference gene name field in the annotation data.

For DNAm and GE integration, the CpGs were listed together with their directionalities and then the data was sorted according to the direction of expression of each gene and associated CpGs. The data was categorized into 4 subsets depending on the direction of GE and DNAm: (1) genes with associated CpGs with negative trend of correlation, (2) genes with associated CpGs with positive trend of correlation, (3) genes with associated CpGs that were bidirectional, and (4) genes without associated CpG sites. We proceeded with further steps using the subset with negatively correlated CpGs (Suppl. Fig 5) (Integration Dataset 1).

Additionally, to support our analyses we examined the relationship between DNA methylation levels and gene expression using an approach previously described (47) and also based on additional reports (48). First, the differentially expressed genes between CRAD and SFA groups with low versus high differential expression were defined according to negative and positive log fold change values. The total gene list from the integrative dataset 1 were then separately mapped to corresponding probes on HM450K array by genomic coordinates and the density distribution of gene expression and differential DNA methylation between the CRAD and SFA groups was obtained. . Briefly, the log fold change (FDR ≤0.01, FC ≥2) and Δβ (FDR≤ 0.01, Δβ≥ 0.20) values were used for obtaining non-parametric kernel density estimates using density function in R environment for statistical computing with Gaussian smoothing kernel and default bandwidth settings, weighted by the number of observations in each class. Additionally, a correlation test was run using (i) all the differentially expressed genes in Integration Dataset 1 and (ii) the average Δβ values for each of the genes (Integration Dataset 1) mapped differentially expressed CpG.

For miRNA and DNAm, we identified all the differentially methylated (Dme) miRNAs and further filtered to those that were Dme in the TSS. Within this subset of miRNAs, only those that showed negative correlation in terms of expression (Integration Dataset 2) were selected for further validation.

We then used integration Dataset 2 and an in silico prediction list of targeted mRNA (Dataset 4) with a prediction score greater than 75 from databases available online (49, 50) was established. We then compared this dataset 4 with integration dataset 1 and dataset 2 to obtain an integrated set of data where Dme miRNA targeted GE data is obtained. This integration Dataset 3 was used for pathway analysis and validation studies.

Principal component analysis and unsupervised cluster analysis

CpG sites were filtered to remove background noise (details of the parameters used are elaborated in Supplemental methods section) and variance based filter was applied for the remaining 335212 CpG sites. Further all the CpG sites having a variance at or above the 95th percentile were retained (16,761 CpG sites) and were subjected to principal component (PC) analysis and the first and second PCs were plotted against each other. The same 16,761 CpG sites were used when performing average linkage hierarchical clustering, where Pearson’s correlation was used as the distance.

Results

Patients and samples

Characteristics of donors and recipients are shown in Table-1. There were no difference in biopsy collection time between post-KT IFTA and NFA (biopsy collection time= 31.3±6.5 versus 28.3 ± 2.6 months post-KT, p-value = 0.32). No significant differences were observed between groups except for the differences in eGFR values between IFTA and NFA groups. Histological characteristics of samples used are shown in the Table 2. No statistical differences were observed between IFTA samples when sub-classified as training and validation set.

Table 2.

Histopathology of IFTA biopsies used for the study

| Histological findings | IFTA training set (n=18) | IFTA validation set (n=12) |

|---|---|---|

| Interstitial Inflammation (i) | i1: 1 (5.5%) | i1: 2 (12%) |

| i2: 7 (38.9%) | i2:5 (41.7%) | |

| i3: 7 (38.9%) | i3: 4 (33.3%) | |

| Hyaline | ah1: 1 (5.5%) | ah1: 1 (8.3%) |

| ah2: 12 (66.7%) | ah2: 7 (58.3%) | |

| ah3: 1 (5.5%) | ah3:1 (8.3%) | |

| Arteriosclerosis (cv) | cv1: 2 (10.5%) | cv1: 2 (16.7%) |

| cv2: 14 (73.7%) | cv2: 8 (66.7%) | |

| cv3: 3 (15.7%) | cv3: 2 (16.6%) | |

| C4d staining of the peritubular capillaries PTC | ptc1: 0 (0%) | ptc1: 0 (%) |

| ptc2: 1 (5.5%) | ptc:2: 1 (8.3%) | |

| ptc3: 0 (0%) | ptc:3: 0 (0%) | |

| IFTA (ci, ct) | Mild: 0 (0%) | Mild: 0 (0%) |

| Moderate: 11 (61.1%) | Moderate: 8 (66.7%) | |

| Severe: 7 (38.9%) | Severe: 4 (33.3%) | |

| Inflammation associated with IFTA | Minimal: 3 (16.7%) | Minimal: 2 (16.7%) |

| Mild: 5 (27.8%) | Mild: 4 (33.3%) | |

| Moderate: 10 (55.5%) | Moderate: 6(50%) | |

| Severe: 0 (0%) | Severe: 0 (0%) | |

| Tubulitis of intact tubules within/interface | t1: 4 (22.2%) | t1: 3 (25%) |

| t2: 2 (11.1%) | t2: 1 (8.3%) | |

| t3: 2 (11.10%) | t3: 2 (16.6%) | |

| TG (cg) | cg1: 0 (0%) | cg1:0 (0%) |

| cg2: 0 (0%) | cg2:0 (0%) | |

| cg3: 0(0%) | cg3: 0 (0%) | |

| C4d | C4d1: 0 (0%) | C4d1: 1 (8.3%) |

| C4d2: 0 (0%) | C4d2: 0 (0%) | |

| C4d3:0 (0%) | C4d3: 0 (0%) |

All values expressed as n (%). There was no significant difference between the 2 study groups.

Distribution of differentially methylated CpGs across genomic and regulatory features

A total of 17,292 CpG sites corresponding to 5935 genes and spread across CpG islands (10.6%), island shores (24.6%), island shelves (9.8%), and open sea (54.9%) (Supplementary (Suppl.) Fig 1A) were Dme post-KT in kidney biopsies with IFTA (n=18) when compared to NFA samples (n=18).

Around 29.6% of the total annotated CpGs were present in the transcription start sites (TTS) (spread across the CpG islands (7.9%), island shores (39.4%), island shelves (4.9%), and the open sea (47.8 %) (Suppl. Fig 1B)). The numbers of hypo- and hyper-methylated CpGs were similar. A fraction of these genes (14.8 %) were represented by both hypo- and hyper-methylated CpG sites (Suppl. Fig 1C). Dme CpGs in IFTA samples showed that both hyper- and hypo-methylated CpGs were highly enriched in protein coding gene bodies (Fig 2A). Moreover, all the Dme CpGs were strongly enriched in regions that are variably methylated among tissues implying very high tissue specificity in their regulatory impact and interestingly, enrichment analysis to tissue-specific enhancers showed that the hyper-methylated CpG were strongly adult kidney specific while the hypo-methylated CpG were specific to immune cells (Fig 2B). Additionally, the representation of the Dme CpGs across the chromosomes based on general chromosome representation pattern of CpGs on the Illumina bead array, was similar for all the 22 chromosomes Suppl. Fig 2). However, enrichment analysis revealed that hypermethylated CpGs were found to be most significantly enriched in p arm of chromosome 7 (p-value = 1.08E-140) (Fig 2C) (Suppl. Tables 1.1, 1.2).

Figure 2. Enrichment analysis of differentially methylated CpG sites along regulatory features and chromosomes.

Enrichment analysis of the hypo- and hyper-methylated CpG sites was done for (A) genomic regions, (B) tissue-specific enhancers, and (C) chromosome regions. Hyper- and hypo-methylated CpG sites are enriched in the protein coding gene bodies (highlighted in green) (3A); Tissue-specific enhancer enrichment analysis show that the hyper-methylated CpG sites are enriched in the adult kidney specific enhancer regions and the hypo-methylated CpG sites are enriched in the immune cell specific enhancer regions (highlighted in green) (3B); most significantly enriched chromosomal regions by hyper-methylated and hypo-methylated CpG sites were highlighted in green (3C). Significant_CpGs_list_dn represents hypomethylated CpGs; Significant_CpGs_list_up represents hypermethylated CpGs.

Hypo- and hyper-methylated CpGs across genes and associated molecular pathways

In this section, the overall distribution of Dme CpGs across genes was evaluated. As Dme CpG sites were mapped, those genes presenting multiple Dme CpGs (Dataset A, Fig.1), were used to explore the main pathways (IPA (www.ingenuity.org) (51)) that may be affected by the aberrant DNAm patterns identified in the IFTA samples when compared with NFA. The analyses of the hypo-methylated CpGs showed that the top canonical pathways were related to immune system (Fig 3A) including CD28 signaling in T helper cells (p-value = 4.83 E-10; activation Z-score = 5.947; BCL10, ACTR3, CALM1, CD80, CD86, CD3E, ZAP70, VAV1, NFKBIE) and dendritic cell maturation (p-value = 1.52 E-03 Z-score = 6.403; CCR7, CD80, CD86, CD1D, CSF2, HLA-A, HLA-C, HLA-DMA, IL23A, IL1B). The molecular functions of the hypo-methylated genes were related to immune cell trafficking, lymphoid tissue structure and development, cell-cell signaling interaction for activation, migration and homing of leukocytes and the top networks were those involved in cellular function, maintenance, cell-cell signaling and molecular transport (Suppl. Fig 3). Top upstream regulators that were predicted to be activated (activation Z-score ≥8; p-value < 1.11E-13) in IPA analysis included IL2, TNF, IL1B, and NFKB. The hyper-methylated CpG sites on the other hand were mapped to genes that were mostly involved in metabolism especially of those that are important for maintaining stability, structure and function of the kidney. The inhibited pathways included aldosterone pathway in epithelial cells (p-value = 1.11E-02), PDGF signaling (p-value = 1.44E-04), and thrombin signaling (p-value = 1.05E-04) (Fig 3B). Disease/toxicity functions of the genes hyper-methylated included renal hypoplasia and glomerulosclerosis. The upstream regulators predicted to be inhibited included transcription factors like TCF7L2, EBF1, SP1, F2 and HNF1A, all of them with functions associated with tubular epithelial cells and kidney development/repair process.

Fig 3. Biological significance of differentially methylated CpG sites.

IPA analysis was used to identify the top canonical pathways and disease functions associated with hypo-methylated CpG sites (3A) and hyper-methylated CpG sites (3B). The bolded numbers represent the number of genes from the dataset that are present in each pathway (based on current literature)

Genes with dysregulation at two molecular levels: DNAm and gene expression

Paired GE analysis was done (Dataset 2, Fig 1) for the same samples for which methylation studies were done (Dataset 1, Fig 1). 5,472 probe sets corresponding to 3,926 genes were significantly differentially expressed. Of these, 2,366 genes were down regulated and 1,587 genes were upregulated in IFTA. Around 31% of the differentially expressed genes showed Dme patterns at the gene level (Fig 4A). However, within this subset of genes there were genes (38%) for which there were both upregulated and downregulated CpGs. GE data, for which corresponding CpG methylation pattern matched (Integration Dataset 1, Fig 5), were analyzed using a comparison analysis in IPA. The canonical pathways related to immune response (activated state) including TREM1 signaling, actin-base motility by Rho, dendritic cell maturation while those related to nephrogenesis (inhibited state) including STAT3 pathway, PDGF signaling, growth factor signaling were seen to be dysregulated (Fig 4B). The top networks involving these dysregulated genes included developmental disorder, hereditary disorder, metabolic disease (score = 41) and cellular movement, hematological system development and function, immune cell trafficking (score = 32) (Suppl. Fig 4). Additionally, the top disease function were active injury to kidney (Z-score = 2.0, p-value = 1.46E-04) and showed involvement of genes like C3AR1, STAT4, FCGR2A, FABP1 (Fig 4C). Also, the relationship between DNAm levels and GE was evaluated using the R environment for statistical computing (as described in Methods) and a negative correlation (r= −0.76, p-value= 2.2e-16) between datasets was identified (Suppl. Fig 5).

Fig 4. Integration of ex vivo methylation and gene expression data.

Of the total genes that were differentially expressed between IFTA and NFA allografts, a fraction of them were Dme up-stream (4A). IPA comparison analysis of the gene set filtered after integration of methylation and GE data and those genes associated with Dme CpG sites, show canonical pathways related to immune system to be activated* while inhibited* related to organogenesis and metabolism (4B). The genes involved actively participate in disease functions like injury of kidney (4C)The GE legend shows the color key for figures 4B and 4C, while the methylation data legend indicates methylation state for pathways shown in 4B.*orange in heatmap indicates activation of GE and hypermethylation for DNAm; blue in heatmap indicates inhibition for GE and hypomethylation for DNAm.

Fig 5. Data integration work flow.

DNA methylation, miRNA and GE arrays were done from DNA and RNA samples isolated from the same IFTA and NFA renal allograft biopsy samples. Two layer integrations were performed with DNA methylation (Dataset 1) and GE arrays (Dataset 2) and DNA methylation and miRNA arrays (Dataset 3). Each resulted in small data sets that were dysregulated at two molecular layers (Integration Set 1 and 2, respectively).Then, gene targets were predicted in silico for the integrated miRNA data set and this data (Dataset 4) was compared with ex vivo GE array data (Dataset 2) as well as GE array data filtered after integration (Integration Set 1). The overlapped data set (Integration Set 3) is either associated with miRNA expression trend or with both miRNA and DNA methylation trend. The resulting integrated data was then subjected to miRNA-gene target co-expression validation using qPCR in training and validation sets.

Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: integration of DNA methylation, miRNA and gene expression data

DNAm data show that there were Dme CpGs located within the regulatory features of 81 different miRNAs. These results were compared with miRNA array data (Dataset 3, Fig.1) from same samples which showed 86 different miRNAs being differentially regulated between graft biopsy groups (IFTA and NFA). A list of miRNAs that were upregulated in IFTA (miRNA microarray) and were hypo-methylated at the TSS of gene (methylation array) was made. Only 3 miRNAs met the criteria, implying that DNAm is only one of the mechanisms that regulate expression patterns of the miRNAs (Integration Dataset 2, Fig 5). The 3 miRNAs were miR-150, miR-23a and miR- 762. Two of these three miRNAs were previously reported to be expressed in thick ascending limb of rat kidney (52). In silico prediction of the targets for the 3 Dme miRNAs was done as described in Methods. The prediction lists (Dataset 4, Fig 5) were compared with available GE microarray data (Dataset 2, Fig 1) also done on the same IFTA and NFA biopsies. All the differentially expressed mRNAs that were predicted to be targeted for gene regulation by the 3 miRNA and those that match with the directionality of expression (since these miRNA are upregulated and suppress the GE of their targets) resulted in 85 different genes (Integration Dataset 3, Fig 5). 21.2% of these genes were by themselves regulated directly by methylation (affected at the DNAm level and implying that were part of Integration Dataset 1, Fig 5), and 52.9% of these genes despite lacking associated Dme CpGs, could also be targeted and downregulated by these 3 miRNAs (Fig 5). Functional analysis of the genes (Integration Dataset 3, Fig 5) showed kidney tissue specific metabolic functions, especially in the tubular epithelial cells (BHMT2, CLCN5, G6PC, NTRK2, CLCNKB, PPM1H, AHCYL1). Also, among them, inhibitors of TGF beta signaling pathway (PPM1H, TGFB3) were identified to be downregulated corresponding to overall increase in TGFB in the IFTA group. Top disease functions associated with these genes in IPA analysis show dysgenesis, cell death, growth failure and hypoplasia (Z-score ≥2.621) (Fig 6A). It suggests that these genes contribute to renal tubule dysfunction and may be partly responsible for tubular atrophy and tubulo-interstitial fibrosis.

Fig 6. Integration of 3 molecular layers and validations.

The effect of DNA methylation on downstream gene and miRNA expression was studied by assessing sequential data integration at 3 levels: DNA methylation, miRNA and GE. This gene set filtered after integration was seen to be involved in cell death and development disorder especially in growth failure and dysgenesis of organs (A). The 3 miRNA and co-expression of their gene targets were validated using qPCR in training (B) and independent sets (C) of IFTA (n =12) and NFA (n=11)samples. TheΔCt values were plotted using scatter plot. The bar plot represents average datapoint. Student’s T-test was used (* p-value 0.05 – 0.01; ** p-value 0.01 – 0.001; ***p-value ≤0.001).

Validation of results

After integration of DNAm and miRNA, the expressions of the 3 miRNAs that were Dme and differentially expressed from array assays were selected for validation using qPCR. To show co-expression of miRNA-mRNA target pairs (53), the best target pairs for these miRNAs, that (i) were predicted in-silico (49,50) (as described in Methods), (ii) were also present in the GE array data from same samples, and (iii) displayed the highest fold changes, were selected for validation. The miR-150-3p and its target CLDN8, miR-23a-5p and its target PDZRN3, miR-762 and its targets TGFBR3 and G6PC were all validated in both training and independent sets (IFTA=12; NFA=11). The miRNAs were all significantly up-regulated in IFTA samples while their respective mRNA target pairs were significantly down regulated (Fig 6B & 6C). Additionally, genes resulting from the integrative approaches (Integration Dataset 1, Fig 5) that were kidney specific were validated in the independent set using qPCR reactions (Suppl. Fig 6).

Persistent Dme associated with progression of allografts to chronic renal allograft dysfunction

DNAm status of the Pre-KT implant biopsies of both IFTA and NFA was determined also using Infinium Human Methylation 450K bead arrays. The 5% most variable CpG sites were retained (as described in Methods) and used to run unsupervised principal component analysis algorithm between the four groups (Section A; Figure 1): Pre-KT biopsies (n=40) (classified as in Results section 3.1), IFTA at >24 months (n=18) and NFA at >24 months (n=18) (Fig 7). The IFTA samples classified together and independently from all the other samples. Interestingly, the NFA biopsies collected >24-months post-KT appear more similar to the Pre-KT biopsies (Fig 7). Also majority of the Pre- KT biopsies classified as IFTA at 24-months post-KT were closer to the Post-KT IFTA and to the Post-KT NFA samples than those Pre-KT biopsies classified as NFA at 24-months post-KT. Additionally, unsupervised cluster analysis was done and the heatmap with dendograms is provided as Suppl. Fig 7. It can be noted, that DNA modifications observed in IFTA samples occurred post-KT and were not present in paired pre-implantation biopsies. The modifications observed were disease-specific and stronger than the biological patient background (i.e., samples clustered separately (Suppl, Fig 7). Also, it was observed that qualitatively, DNA modifications were lower among NFA samples. However, these detected modifications similarly occurred post-KT and paired pre-KT from NFA samples (i.e., clustered separately but under same main cluster, Suppl. Fig 7).

Fig 7. Principal Component Analysis of differentially methylated CpGs in pre- and post-KT biopsies.

After filtering for all CpG sites with SNP and those that cross reacted and that were unmethylated/methylated in all samples (β < 0.10 and β > 0.90 respectively) 335212 CpGs remained for each of the samples. A variance-based filter was applied to these CpG sites and those having a variance at or above the 95th percentile (16761 CpG sites) were subjected to principal components analysis and the first and second principal components were plotted against each other. Green represents CRAD (post-KT); orange represents NFA (post-KT); blue represents Non-progressors to CRAD (Pre-KT); and red presents Progressors to CRAD (Pre-KT).

Discussion

The progressive decline in kidney graft function with subsequent graft loss is characterized histologically by the development of IFTA, regardless of the initial source of injury. However, the factors which mediate advancement of initial graft injury to end-stage disease remains incompletely understood. Similar to wound repair, fibrosis is a process triggered by injury and characterized by the deposition of extracellular matrix through activated fibroblasts. However, in contrast to wound repair, fibrogenesis can progress even after the initiating insult has disappeared. The mechanisms that contribute to the maintenance of the pro-fibrotic environment have not been well delineated, and may involve epigenetic modification of GE.

Recent reports have demonstrated an association between epigenetic modifications and CKD (28). Most of these studies apply methodology/approach that is too restrictive in scope, or utilizes systemic sampling (peripheral blood) which obscures the epigenetic modifications that are tissue specific. Currently, there is a research gap concerning the role of epigenetic modifications in chronic renal allograft dysfunction, the CKD equivalent in kidney transplantation. Additionally, the relationship between epigenetic changes and GEas cause and effect has not yet been fully explored, and represents a new and complex area of investigation with high relevance in the understanding of complex diseases. In the current pilot study, we evaluated a possible role of epigenetic modifications in molecular graft pathways that contribute to fibrosis development leading to loss of graft function. Using an integrative multi-omic approach, three molecular layers of GE control were evaluated in kidney graft samples with IFTA to further understand the underlying mechanisms of fibrosis development.

DNAm was initially described as an epigenetic gene silencing mark several decades ago; however since the advent of genome-scale technologies this traditional view has been evolving (54). The emerging information suggests that the function of DNAm may vary depending upon the context, with evidence to suggest the position of DNAm relative to the transcriptional unit may affect gene activity in different ways. DNAm at the TSS inhibits the binding of DNA polymerase or transcription factors, and hence gene transcription. The role of DNAm within the gene body is poorly understood, with evidence for both positive and negative correlations with transcription.

Based on these concepts, we followed careful sequential analyses in our study. First, after evaluating DNAm patterns between IFTA and NFA samples, we analyzed the distribution pattern of the Dme CpG sites along the regulatory features and chromosomes. Chromosome enrichment of the CpG sites was observed and the most significant was the association of hyper-methylated sites at Chromosome 7p15 region (Fig 3C). The identified CpGs, represent a cluster of homeobox genes (HOXA10, HOXA2, HOXA3, HOXA4, HOXA5) (www.atlasgeneticsoncology.org) (55) which are DNA binding transcription factors known to function in GE, morphogenesis and differentiation during development. They have been extensively studied in hematopoiesis (56), but their regulatory role in the adult kidney has been also reported in cell culture models for cancer (57). Considering the process of active cell death in the kidney graft with IFTA (58), methylation status of these genes could partly facilitate to the process.

The distribution of the Dme CpG sites was mostly identified in the intergenic regions or the open sea (Suppl. Fig 1) where consistently higher variably methylated CpGs are more often reported (59). These intergenic regions serve as runway for transcription factors to bind to the transcription site (60) and activate GE. Consequently, their valuable role in GE regulation deserves further exploration.

The distribution of CpG sites in the promoter-associated regions was more important in the CpG island shore regions (Suppl. Fig 1B), reported to be dynamic and highly correlated with GE changes (61,62). Further, hypo- and hyper-methylated CpG sites were strongly enriched in intragenic protein coding gene bodies (Fig 2A). There are reports linking these sites to tissue specific enhancers (63,64) while few studies show that these sites are responsible for tissue-specific spatiotemporal regulation of GE during development (60,65). Interestingly, in this study tissue-specific enhancer enrichment analysis showed immune cell specificity for the hypo-methylated CpG sites, while hyper-methylated sites associated with homeostasis and structural maintenance of the adult kidney (Fig 2B) as further discussed below.

At the biological level, the genes annotated to hypo- and hyper-methylated CpG sites are in concordance with enrichment analysis stated above. The hypo-methylated CpGs sites corresponded to T helper cell activation, maturation, proliferation and survival. Other sites corresponded to maturation of antigen presenting cells like macrophages and dendritic cells. Hypo-methylation of genes including LCK, CD80, and CD86 involved in activation of CD8 and CD4 positive T cells and MHC genes (especially Class–II genes, including HLA-DMA, HLA-DMB, HLA-DOB, HLA-DPA1, HLA-DRA1, among others) was observed. Instead, hyper- methylated CpG sites were related to metabolic functions, integrity and structure of kidney: (1) genes associated with ion channels (ie., ENaC, Na+/H+ antiporter), as well as genes in the aldosterone signaling pathway in epithelial cells; (2) genes involved in the PCP pathway, which participate in the maintenance of podocytes, repair of tubules and glomerulus, and preservation of glomerulus filtration barrier (66), including DVL, DAAM1, FZD, WNT, CELSR. Although the described characteristic DNAm patterns have been further corroborated downstream with similar pathways seen differentially expressed in the same samples, our initial observations were done to mainly evaluate the overall distribution of Dme CpGs across genes.

While we recognize that the role of DNAm may extend beyond regulating gene transcription, we were mainly interested in the likely consequences for GE. To that end, direct examination of genome-wide expression was implemented to assess functional relevance. The overall directionality matching GE with methylation was 31.3%, implying the probable extent of DNAm mediated regulation of GE. The hypo-methylated and highly expressed genes were mostly immune cell related and might represent the effect of the continued host immune response to the graft in grafts progressing to CRAD. The cumulative function of these integrated genes is predicted to activate injury in the kidney. This includes genes like CCR1, CD44, ICAM1 and STAT4 involved in recruitment of immune cells and thereby exacerbate kidney injury. The role of complement system in long-term kidney injury was also observed with genes like C3AR1, C5AR1, FCGR2A. Due to the observed hypo-methylation of the complement receptors, they could be constitutively expressed on macrophages and CD4+ T cells and stimulates maturation, cytokine production and costimulatory molecule expression (67). In addition to immune-mediated damage, genes like FABP1 and Proc that have been previously shown to have protective function and recovery in kidney post-ischemic injury (68–70) were hyper-methylated (DNAm array) and downregulated (mRNA array). We acknowledge that the kidney graft samples represent a heterogeneous system, include a mix of structural kidney cells, resident APC from donor kidney and infiltrating cells from the host. This issue will influence every study evaluating kidney graft biopsies, independently of the methodology being applied or the analyses performed. However, the multi-omic approach and integrative analyses including gene enrichment provide a unique opportunity to evaluate the immune response of the host to the graft and the answer of the donor kidney to the injury.

A complex epigenetic network exists whereby even miRNA expression is under epigenetic control (71). To further explore if DNAm could regulate GE indirectly, via regulation of miRNA, we added another step to the integration. We have identified genes that were regulated by hypo-methylated miRNAs (in TSS region). Most of these genes were related to metabolomic processes and were notably downregulated. For instance, PPMIH dephosphorylates SMAD1/5/8 and attenuates BMP signaling. It has been reported that downregulation of this gene results in enhanced BMP-mediated cell signaling and mesenchymal differentiation (72). Similarly, TGFBR3 was reported to inhibit TGF beta signaling pathway which is usually associated with increased ECM production, mesenchymal transition of cells (73). G6PC deficiency is associated with oxidative stress, interstitial fibrosis and nephromegaly (74). Loss of function mutations of few of the genes that were critically downregulated have been linked to renal abnormalities during development implying their role in kidney function. CLCNKB, a voltage gated chloride channel in the distal tubules is an example (75) which was present on chromosome 1p36 region which is highlighted by enrichment analysis of the hyper-methylated CpGs from the present study and interestingly a rare chromosome 1p36 deletion syndrome is associated with developmental defects that includes renal anomalies. NTRK2 is yet another example, SNPs in which have been attributed to heritability of eGFR implying its role in renal function/dysfunction (76). ARHGAP24 mutation is associated with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis as its loss of function results in dysfunction of podocytes (77. In summary the genes that were down regulated by DNAm or by a concerted effort of DNAm and miRNA, have important roles in maintaining functional and structural homeostasis of kidney. Allografts with differential DNAm patterns could affect the wound healing process profoundly and result in progression to IFTA.

The mechanisms elucidated above show DNAm of CpG sites as a possible cause for exacerbated immune mediated damage and decreased metabolism in the kidney graft during continuous graft injury leading to chronic dysfunction. However, despite of the robustness of the identified findings, the exact cause of this differential DNAm and the time when this change is apparent is not clear. Consequently, additional mechanistic studies are needed to validate these interactions.

Furthermore, when the only publicly available DNAm data from kidney (micro-dissected tubules) of diabetic CKD (DKD) biopsies (GSE50874) (27) was comparatively analyzed with our allograft biopsies with IFTA, overlap of gene methylation patterns was observed. Genes like SMAD 6, SMAD 3 which were reported to be critical for TGF beta signaling pathway and DKD development were also Dme in IFTA samples. Similarly, RUNX1 which was reported to be Dme in tubules of DKD patients and Col4A1 one of the collagen genes were also among the common genes that we observed in renal allograft samples from patients with IFTA. Additionally, a number of genes involved in adaptive and innate immune inflammatory pathways (i.e., CD45/PTPRC, CD58, IRF8, BCL2, LCK, LCP2, among others) were also present in the common gene list. This clearly shows overlap of mechanisms of fibrosis development in DKD kidneys and grafts with IFTA, supporting the hypothesis of common pathways associated with fibrogenesis.

The validation of best set of genes and miRNAs in the training and validation sets, and the overlap of gene sets with previous published genes associated with IFTA (58,78) show the reproducibility of our results. This is particularly relevant considering that we focused our integrative validation on those miRNA sequences located close by the TSS, implying likely high impact on GE. Moreover, the validation of the co-expression of miRNAs and their target genes following the expected biological expression direction in training and validation sets imply a consistent upstream regulatory mechanism which could be related to DNAm as shown in this integrative study.

To better understand if the observed DNAm changes in the IFTA group were a consequence of the events occurring post-KT, we further extended the DNAm study to Pre-KT biopsies categorized as IFTA or NFA at > 24 months post-KT. To visualize the similarity of the individual cases in the dataset, all the CpG sites having a variance at or above the 95th percentile were retained and used to run unsupervised principal component analysis algorithm between the four groups (Section A; Figure 1). The IFTA samples classified together and independently from all the other samples. Interestingly, the NFA biopsies collected >24-months post-KT appear more similar to the Pre-KT biopsies (Fig 7). A majority of the Pre- KT biopsies classified as IFTA at 24-months post-KT were closer to the Post-KT IFTA and to the Post-KT NFA samples than those Pre-KT biopsies classified as NFA at 24-months post-KT. Also, a pattern (less drastic in the number of Dme CpG sites) was observed in Pre-KT biopsies classified as IFTA versus NFA at > 24 months post-KT, indicating that DNAm patterns in the donor organ before transplant can already be critical in prediction of long-term outcomes.

Our findings demonstrate for the first time a possible critical relationship among epigenetic modifications and IFTA development, graft function, and inter-individual variation on long-term outcomes. Strengths of our study include the evaluation of tissue-specific kidney graft DNAm patterns, use of integrative approaches using ex vivo data for same samples, independent validation of miRNA:mRNA interactions and main tissue specific affected genes, strict cut-off criteria for identifying statistical and biological differences among groups, and well-selected samples from a large prospective cohort study with detailed phenotypic information. Limitations of the study mainly relate to the complexity associated with further validation of epigenetic modifications on GE and a relatively small sample size. A longitudinal large study is needed to deduce the sequential changes in DNAm pattern and their relationship with graft fibrosis progression. The current study represents the foundation for further evaluation of the role of epigenetic modifications on critical molecular pathways leading graft injury and affecting long-term graft outcomes. Moreover, it might represent the basis for the evaluation of the role of epigenetics modifications in native kidneys progressing to CKD and other solid organs.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Differentially methylated CpGs and their distribution in relation to CpG island

Supplemental Figure 2: Differentially methylated CpG sites per chromosome.

Supplemental Figure 3: Top Networks of the genes associated with Hypomethylated CpG sites.

Supplemetal Figure 4: Top Networks of the genes that are differentially methylated and differentially expressed downstream.

Supplemetal Figure 5: DNA methylation and gene expression correlation in Integrative dataset 1.

Supplemental Figure 6: qPCR of kidney specific genes selected from integration dataset 1 in validation sample set.

Supplemental Figure 7 Unsupervised cluster analysis.

Supplemental Table 1.1: P- values of enrichment analysis of hypo-methylated CpG sites on chromosome locations.

Supplemental Table 1.2: P-values of enrichment analysis of hypermethylated CpG sites on chromosome locations.

Supplemental Table 2: Distribution of differentially methylated gene mapped CpGs

Acknowledgments

The research results included in this report were supported by a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grants, R01DK080074, RO1DK109581, and R21DK100678 and UVAHS internal funding for translational research.

List of Abbreviations

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- Dme

Differentially methylated

- DNAm

DNA methylation

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- GE

Gene expression

- IFTA

Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy

- KT

Kidney transplantation

- KTR

Kidney transplant recipient

- NFA

Stable functioning allograft with no or minimal IFTA

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supporting information (description)

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Matas AJ, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Lamb KE, Gustafson SK, Samana CJ, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2011 Annual Data Report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(Suppl 1):11–46. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yilmaz S, Sar A. Pathogenesis and management of chronic allograft nephropathy. Drugs. 2008;68(Suppl 1):21–31. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lodhi SA, Lamb KE, Meier-Kriesche HU. Improving long-term outcomes for transplant patients: making the case for long-term disease-specific and multidisciplinary research. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2264–2265. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lodhi SA, Lamb KE, Meier-Kriesche HU. Solid organ allograft survival improvement in the United States: the long-term does not mirror the dramatic short-term success. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1226–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meier-Kriesche HU, Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Kaplan B. Lack of improvement in renal allograft survival despite a marked decrease in acute rejection rates over the most recent era. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:378–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langone AJ, Chuang P. The management of the failed renal allograft: an enigma with potential consequences. Semin Dial. 2005;18:185–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao PS, Ojo A. Organ retransplantation in the United States: trends and implications. Clin Transpl. 2008:57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kendrick EA, Davis CL. Managing the failing allograft. Semin Dial. 2005;18:529–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill JS. Managing patients with a failed kidney transplant: how can we do better? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20:616–621. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32834bd792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perl J, Zhang J, Gillespie B, Wikstrom B, Fort J, Hasegawa T, et al. Reduced survival and quality of life following return to dialysis after transplant failure: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:4464–4472. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matas AJ, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Thompson B, Gustafson SK, Schnitzler MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2012 Annual Data Report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(Suppl 1):11–44. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis JD, Meehan RR, Henzel WJ, Maurer-Fogy I, Jeppesen P, Klein F, et al. Purification, sequence, and cellular localization of a novel chromosomal protein that binds to methylated DNA. Cell. 1992;69:905–914. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90610-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eden S, Cedar H. Role of DNA methylation in the regulation of transcription. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:255–259. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robertson KD. DNA methylation and human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith ZD, Meissner A. DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bechtel W, McGoohan S, Zeisberg EM, Muller GA, Kalbacher H, Salant DJ, et al. Methylation determines fibroblast activation and fibrogenesis in the kidney. Nat Med. 2010;16:544–550. doi: 10.1038/nm.2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeisberg EM, Zeisberg M. The role of promoter hypermethylation in fibroblast activation and fibrogenesis. J Pathol. 2013;229:264–273. doi: 10.1002/path.4120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato M, Natarajan R. Diabetic nephropathy--emerging epigenetic mechanisms. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:517–530. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smyth LJ, McKay GJ, Maxwell AP, McKnight AJ. DNA hypermethylation and DNA hypomethylation is present at different loci in chronic kidney disease. Epigenetics. 2014;9:366–376. doi: 10.4161/epi.27161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friso S, Choi SW. Gene-nutrient interactions and DNA methylation. J Nutr. 2002;132(8 Suppl):2382S–2387S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2382S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat Genet. 2003;33(Suppl):245–254. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee PP, Fitzpatrick DR, Beard C, Jessup HK, Lehar S, Makar KW, et al. A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity. 2001;15:763–774. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng Y, Josefowicz S, Chaudhry A, Peng XP, Forbush K, Rudensky AY. Role of conserved non-coding DNA elements in the Foxp3 gene in regulatory T-cell fate. Nature. 2010;463:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature08750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaknovich R, Cerchietti L, Tsikitas L, Kormaksson M, De S, Figueroa ME, et al. DNA methyltransferase 1 and DNA methylation patterning contribute to germinal center B-cell differentiation. Blood. 2011;118:3559–3569. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-357996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pratt JR, Parker MD, Affleck LJ, Corps C, Hostert L, Michalak E, et al. Ischemic epigenetics and the transplanted kidney. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:3344–3346. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hahn MA, Hahn T, Lee DH, Esworthy RS, Kim BW, Riggs AD, et al. Methylation of polycomb target genes in intestinal cancer is mediated by inflammation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10280–10289. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ko YA, Mohtat D, Suzuki M, Park AS, Izquierdo MC, Han SY, et al. Cytosine methylation changes in enhancer regions of core pro-fibrotic genes characterize kidney fibrosis development. Genome Biol. 2013;14(10):R108. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wing MR, Devaney JM, Joffe MM, Xie D, Feldman HI, Dominic EA, et al. DNA methylation profile associated with rapid decline in kidney function: findings from the CRIC study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:864–872. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neary R, Watson CJ, Baugh JA. Epigenetics and the overhealing wound: the role of DNA methylation in fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2015;8:18-015-0035-8. doi: 10.1186/s13069-015-0035-8. eCollection 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehta TK, Hoque MO, Ugarte R, Rahman MH, Kraus E, Montgomery R, et al. Quantitative detection of promoter hypermethylation as a biomarker of acute kidney injury during transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:3420–3426. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker MD, Chambers PA, Lodge JP, Pratt JR. Ischemia- reperfusion injury and its influence on the epigenetic modification of the donor kidney genome. Transplantation. 2008;86:1818–1823. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31818fe8f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jevnikar AM, Mannon RB. Late kidney allograft loss: what we know about it, and what we can do about it. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(Suppl 2):S56–67. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03040707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fonseca I, Reguengo H, Almeida M, Dias L, Martins LS, Pedroso S, et al. Oxidative stress in kidney transplantation: malondialdehyde is an early predictive marker of graft dysfunction. Transplantation. 2014;97:1058–1065. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000438626.91095.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB, Bonsib SM, Castro MC, Cavallo T, et al. The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney Int. 1999;55:713–723. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solez K, Colvin RB, Racusen LC, Haas M, Sis B, Mengel M, et al. Banff 07 classification of renal allograft pathology: updates and future directions. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:753–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sis B, Mengel M, Haas M, Colvin RB, Halloran PF, Racusen LC, et al. Banff ‘09 meeting report: antibody mediated graft deterioration and implementation of Banff working groups. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:464–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haas M, Sis B, Racusen LC, Solez K, Glotz D, Colvin RB, et al. Banff 2013 meeting report: inclusion of c4d-negative antibody-mediated rejection and antibody-associated arterial lesions. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:272–283. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farris AB, Chan S, Climenhaga J, Adam B, Bellamy CO, Seron D, et al. Banff fibrosis study: multicenter visual assessment and computerized analysis of interstitial fibrosis in kidney biopsies. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:897–907. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elmore JG, Tosteson AN, Pepe MS, Longton GM, Nelson HD, Geller B, et al. Evaluation of 12 strategies for obtaining second opinions to improve interpretation of breast histopathology: simulation study. BMJ. 2016;353:i3069. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maksimovic J, Gordon L, Oshlack A. SWAN: Subset-quantile within array normalization for illumina infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChips. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R44-2012--13-6-r44. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du P, Zhang X, Huang CC, Jafari N, Kibbe WA, Hou L, et al. Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:587-2105-2111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carvalho BS, Irizarry RA. A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2363–2367. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5(10):R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. Quantitative trait Loci analysis using the false discovery rate. Genetics. 2005;171:783–790. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dozmorov MG, Cara LR, Giles CB, Wren JD. GenomeRunner: automating genome exploration. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:419–420. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Characteristics of DNA methylation and gene expression in regulatory features on the Infinium 450k Beadchip. Martino D, Saffery R bioRxiv 032862. https://doi.org/10.1101/032862.

- 48.Simcha DM, Younes L, Aryee MJ, Geman D. Identification of direction in gene networks from expression and methylation. BMC Syst Biol. 2013;7:118. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-7-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong N, Wang X. miRDB: an online resource for microRNA target prediction and functional annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D146–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. [date last accessed: 05/26/2016];Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. http://www.ingenuity.com.

- 52.Mladinov D, Liu Y, Mattson DL, Liang M. MicroRNAs contribute to the maintenance of cell-type-specific physiological characteristics: miR-192 targets Na+/K+-ATPase beta1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:1273–1283. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuhn DE, Martin MM, Feldman DS, Terry AV, Jr, Nuovo GJ, Elton TS. Experimental validation of miRNA targets. Methods. 2008;44:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bestor TH, Edwards JR, Boulard M. Notes on the role of dynamic DNA methylation in mammalian development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:6796–6799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415301111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. [date last accessed: 05/26/2016];Atlas of genetics and cytogenetics in oncology and Haematology. http://AtlasGeneticsOncology.org.

- 56.Argiropoulos B, Humphries RK. Hox genes in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Oncogene. 2007;26:6766–6776. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shears L, Plowright L, Harrington K, Pandha HS, Morgan R. Disrupting the interaction between HOX and PBX causes necrotic and apoptotic cell death in the renal cancer lines CaKi-2 and 769-P. J Urol. 2008;180:2196–2201. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scian MJ, Maluf DG, Archer KJ, Suh JL, Massey D, Fassnacht RC, et al. Gene expression changes are associated with loss of kidney graft function and interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy: diagnosis versus prediction. Transplantation. 2011;91:657–665. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182094a5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Illingworth RS, Bird AP. CpG islands--‘a rough guide’. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1713–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Doi A, Park IH, Wen B, Murakami P, Aryee MJ, Irizarry R, et al. Differential methylation of tissue- and cancer-specific CpG island shores distinguishes human induced pluripotent stem cells, embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1350–1353. doi: 10.1038/ng.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Irizarry RA, Ladd-Acosta C, Wen B, Wu Z, Montano C, Onyango P, et al. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shores. Nat Genet. 2009;41:178–186. doi: 10.1038/ng.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rauch TA, Wu X, Zhong X, Riggs AD, Pfeifer GP. A human B cell methylome at 100-base pair resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:671–678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812399106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singer M, Kosti I, Pachter L, Mandel-Gutfreund Y. A diverse epigenetic landscape at human exons with implication for expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:3498–3508. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kleinjan DA, Seawright A, Childs AJ, van Heyningen V. Conserved elements in Pax6 intron 7 involved in (auto)regulation and alternative transcription. Dev Biol. 2004;265:462–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Papakrivopoulou E, Dean CH, Copp AJ, Long DA. Planar cell polarity and the kidney. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:1320–1326. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cravedi P, van der Touw W, Heeger PS. Complement regulation of T-cell alloimmunity. Semin Nephrol. 2013;33:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Portilla D. Energy metabolism and cytotoxicity. Semin Nephrol. 2003 Sep;23(5):432–438. doi: 10.1016/s0270-9295(03)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamamoto T, Noiri E, Ono Y, Doi K, Negishi K, Kamijo A, et al. Renal L-type fatty acid--binding protein in acute ischemic injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2894–2902. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gupta A, Williams MD, Macias WL, Molitoris BA, Grinnell BW. Activated protein C and acute kidney injury: Selective targeting of PAR-1. Curr Drug Targets. 2009;10:1212–1226. doi: 10.2174/138945009789753291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sato F, Tsuchiya S, Meltzer SJ, Shimizu K. MicroRNAs and epigenetics. FEBS J. 2011;278:1598–1609. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shen T, Sun C, Zhang Z, Xu N, Duan X, Feng XH, et al. Specific control of BMP signaling and mesenchymal differentiation by cytoplasmic phosphatase PPM1H. Cell Res. 2014;24:727–741. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eickelberg O, Centrella M, Reiss M, Kashgarian M, Wells RG. Betaglycan inhibits TGF-beta signaling by preventing type I-type II receptor complex formation. Glycosaminoglycan modifications alter betaglycan function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:823–829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Clar J, Gri B, Calderaro J, Birling MC, Herault Y, Smit GP, et al. Targeted deletion of kidney glucose-6 phosphatase leads to nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2014;86:747–756. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Simon DB, Bindra RS, Mansfield TA, Nelson-Williams C, Mendonca E, Stone R, et al. Mutations in the chloride channel gene, CLCNKB, cause Bartter’s syndrome type III. Nat Genet. 1997;17:171–178. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thameem F, Voruganti VS, Blangero J, Comuzzie AG, Abboud HE. Evaluation of neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase 2 (NTRK2) as a positional candidate gene for variation in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in Mexican American participants of San Antonio Family Heart study. J Biomed Sci. 2015;22:23-015-0123-5. doi: 10.1186/s12929-015-0123-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Akilesh S, Suleiman H, Yu H, Stander MC, Lavin P, Gbadegesin R, et al. Arhgap24 inactivates Rac1 in mouse podocytes, and a mutant form is associated with familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2011t;121:4127–4137. doi: 10.1172/JCI46458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Einecke G, Reeve J, Sis B, Mengel M, Hidalgo L, Famulski KS, et al. A molecular classifier for predicting future graft loss in late kidney transplant biopsies. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1862–1872. doi: 10.1172/JCI41789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Differentially methylated CpGs and their distribution in relation to CpG island

Supplemental Figure 2: Differentially methylated CpG sites per chromosome.

Supplemental Figure 3: Top Networks of the genes associated with Hypomethylated CpG sites.

Supplemetal Figure 4: Top Networks of the genes that are differentially methylated and differentially expressed downstream.

Supplemetal Figure 5: DNA methylation and gene expression correlation in Integrative dataset 1.

Supplemental Figure 6: qPCR of kidney specific genes selected from integration dataset 1 in validation sample set.

Supplemental Figure 7 Unsupervised cluster analysis.

Supplemental Table 1.1: P- values of enrichment analysis of hypo-methylated CpG sites on chromosome locations.

Supplemental Table 1.2: P-values of enrichment analysis of hypermethylated CpG sites on chromosome locations.

Supplemental Table 2: Distribution of differentially methylated gene mapped CpGs