Abstract

Background: In health care, burnout has been defined as a psychological process whereby human service professionals attempting to positively impact the lives of others become overwhelmed and frustrated by unforeseen job stressors. Burnout among various physician groups who primarily practice in the hospital setting has been extensively studied; however, no evidence exists regarding burnout among hospital clinical pharmacists. Objective: The aim of this study was to characterize the level of and identify factors independently associated with burnout among clinical pharmacists practicing in an inpatient hospital setting within the United States. Methods: We conducted a prospective, cross-sectional pilot study utilizing an online, Qualtrics survey. Univariate analysis related to burnout was conducted, with multivariable logistic regression analysis used to identify factors independently associated with the burnout. Results: A total of 974 responses were analyzed (11.4% response rate). The majority were females who had practiced pharmacy for a median of 8 years. The burnout rate was high (61.2%) and largely driven by high emotional exhaustion. On multivariable analysis, we identified several subjective factors as being predictors of burnout, including inadequate administrative and teaching time, uncertainty of health care reform, too many nonclinical duties, difficult pharmacist colleagues, and feeling that contributions are underappreciated. Conclusions: The burnout rate of hospital clinical pharmacy providers was very high in this pilot survey. However, the overall response rate was low at 11.4%. The negative effects of burnout require further study and intervention to determine the influence of burnout on the lives of clinical pharmacists and on other health care–related outcomes.

Keywords: burnout, pharmacists, hospital

Background

“Burnout” has previously been described as a condition of emotional exhaustion, diminished feeling of accomplishment, and depersonalization, all of which result in reduced effectiveness at work.1,2 Prominent symptoms include fatigue, poor decision-making abilities, cynical attitude, feeling inadequate, and withdrawal from coworkers or patients.3,4 With respect to health care providers, Maslach and Leiter specifically defined burnout as a psychological process whereby human service professionals attempting to positively impact the lives of others become overwhelmed and frustrated by unforeseen job stressors.2 In recent years, burnout among various physician groups who primarily practice in the hospital setting has been extensively studied and shown to influence their job satisfaction,5-7 increase malpractice lawsuits,8 and contribute to early retirement.9-11 More importantly, physician burnout has been linked to diminished patient satisfaction with care12,13 and an increased number of medical errors.1,5-7,12

In today’s hospital environment, the presence of various health care professionals on the multidisciplinary care team may allow other clinicians to aid physicians in diminishing the negative effects of burnout on patient care. However, there are limited data available assessing burnout among other members of the health care team. One group of providers uniquely positioned to aid in negating the effects of physician burnout as it relates to medication errors are hospital clinical pharmacists. According to the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP), the practice of clinical pharmacy embraces the philosophy of pharmaceutical care by combining specialized therapeutic knowledge, experience, and judgment with the aim of optimizing patient outcomes. To achieve these outcomes, clinical pharmacists may accept responsibility for managing medication therapy both as independent providers and in consultation with other health care professionals.13 Current literature has shown that pharmacist evaluation of prescription orders leads to an increased identification and resolution of medication errors, as well as increased optimization of therapy.14-16

Based upon previous literature, the presence of hospital clinical pharmacy practitioners leads to improved patient outcomes. In their daily duties, these pharmacists play a significant role in identifying and managing medication errors that occur. Given that burnout has been linked to increased medication prescribing errors among physicians, it is reasonable to infer that hospital clinical pharmacists may play an increased role in patient care in the setting of physician burnout. However, there are no studies of burnout among this group of providers. The primary aim of this study was to characterize the level of and to identify factors independently associated with burnout among clinical pharmacists who practice in the inpatient hospital setting. Given that there is no previous research related to burnout in this group, we also aimed to determine the feasibility to survey this large group of health care providers.

Methods

An online survey (Qualtrics; Online Appendix 1) was distributed to members of various Practice and Research Networks (PRN) of ACCP. This avenue for disseminating the survey was selected as we felt it would yield the best odds of reaching clinicians who self-identify as clinical pharmacists. The survey remained open for a 21-day period from January 25 to February 14, 2016. Initially, the survey invitation was sent to the chairs of 18 ACCP PRNs whose membership was thought to include those practicing in an inpatient hospital setting. We asked the PRN chairs to send the link to their membership with the hope that receipt of the survey from the PRN chair would elicit a higher response rate. The survey invitation was then sent by 14 PRN chairs to their membership and included a link to the survey, as well an outline of the survey purpose. We requested that all individuals completing the survey be actively engaged in the practice of clinical pharmacy within the hospital setting and not currently enrolled in a pharmacy residency. No personal identifiers were linked to survey results to ensure privacy and data were maintained by one investigator (G.M.J.) on a password-protected computer. The institutional review board approved the project as exempt. The format of the survey, including the order of questions, was based upon a previous survey published in another medical subspecialty area.3 Questions from this survey were evaluated by the authors and if determined to be not applicable were modified by the authors to be more applicable to the practice of hospital clinical pharmacy.

Descriptive summary statistics were utilized to outline the overall cohort of respondents. Select survey responses were combined into categories for the purposes of statistical analysis based upon previous literature and number of responses within the original selections.3 For example, responses to specific questions regarding professional perceptions that were hypothesized to have a large impact on the desired outcome were converted from a Likert-type scale to dichotomous variables. We decided a priori to quantify and identify predictors of burnout.

Burnout was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Mind Garden, Incorporated), a validated 22-item questionnaire considered to be the gold standard tool for assessing burnout.2,17,18 Responses are expressed in terms of the frequency that the respondents have specific feelings (0 = never and 5 = a few times a week). Based upon the responses to all questions, point totals are recorded and scores for each of the 3 domains (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment) are generated. Each domain is assessed on the levels of “high,” “moderate,” and “low” according to accepted threshold values validated in the MBI specific to health care professionals (Table 1).2 In the same manner as previous research among physicians, burnout was defined as having an emotional exhaustion score ≥27 and/or depersonalization score ≥10.1,3

Table 1.

Burnout Assessment of Inpatient Hospital Clinical Pharmacists.

| Burnout indices | Median score | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | 28 | — |

| Low score (≤18) | 231 (23.7) | |

| Moderate score | 228 (23.4) | |

| High score (≥27) | 515 (52.9) | |

| Depersonalization | 6 | — |

| Low score (≤5) | 443 (45.5) | |

| Moderate score | 213 (21.9) | |

| High score (≥10) | 318 (32.6) | |

| Personal accomplishment | 34 | |

| Low score (≤33) | 477 (49.0) | |

| Moderate score | 396 (40.7) | |

| High score (≥40) | 101 (10.3) | |

| Burned out | — | 596 (61.2) |

Note. A respondent was determined to have burnout if his or her scores for emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization were in the “high” categories.

After conducting univariate analyses of burnout, forward multivariable logistic regression was undertaken. Variables with a P < .2 in the univariate analysis were placed into the logistic regression model initially. The model was evaluated for evidence of lack of fit based on the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Model performance was further assessed using the area under receiver operating characteristic curve. Two-tailed statistical tests were utilized, and a P < .05 was determined to represent statistical significance. The level of statistical significance for multiple comparisons was not adjusted. Results were reported as adjusted odds ratio (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All data were analyzed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0, Armonk, New York).

Results

A total of 1256 individuals completed at least a portion of the survey. To determine the most accurate response rate possible, an enrollment query of ACCP membership was conducted and revealed that exactly 8529 unique member email addresses received the survey invitation. While our total response rate was 14.7%, certain individuals who completed the survey were not part of the requested target demographic and were excluded. We excluded 175 respondents who did not complete the MBI portion of the survey due to an inability to assess burnout without this information. A total of 103 individuals stated they currently practiced in ambulatory care, which did not meet our target practice setting for this pilot survey, and were also excluded. The remaining data were reviewed to ensure that all respondents met the targeted demographic of nonresident, practicing clinicians. Based upon individual responses, we excluded 4 additional cases (1 who stated they were a resident and 3 who stated they no longer actively practiced pharmacy) and used the remaining 974 survey responses for the final analysis for an included response rate of 11.4%.

In the full cohort of respondents, the majority were young (median age 35 years) females (69.5%) in a stable relationship (68.1%) who had practiced pharmacy for a median number of 8 years. Most respondents reported working full-time (97.4%) in an academic hospital setting (46.9% primary university hospital and 30.8% community academic hospital) for a median of 48 hours per week. Nearly three-quarters were certified by the Board of Pharmacy Specialties (73.0%), and more than half completed some form of residency training (58.1%). A detailed summary of personal and practice characteristics for all 974 survey participants is provided in Supplemental Table 1.

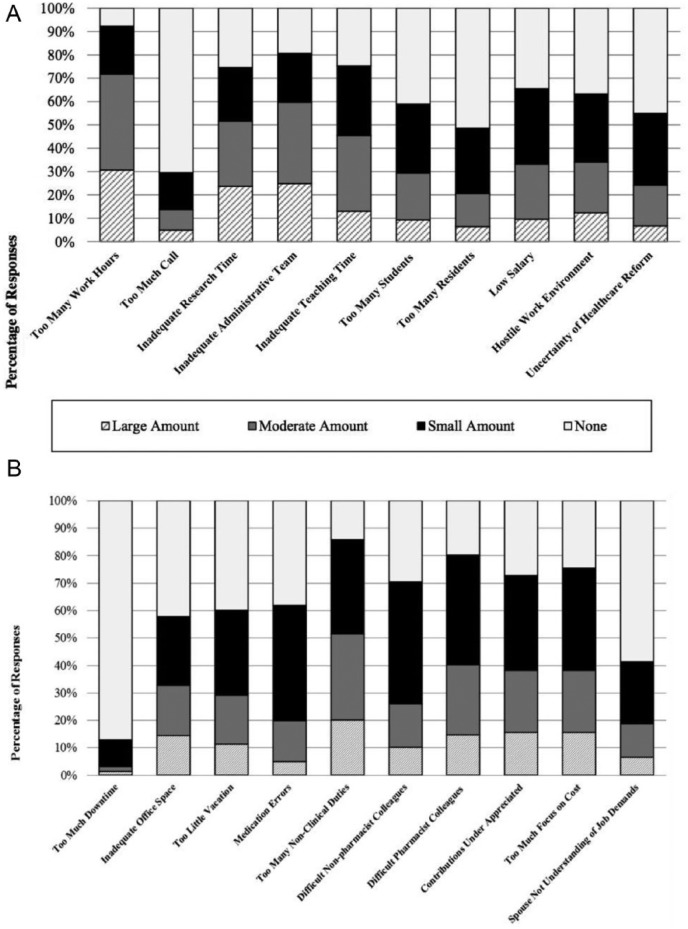

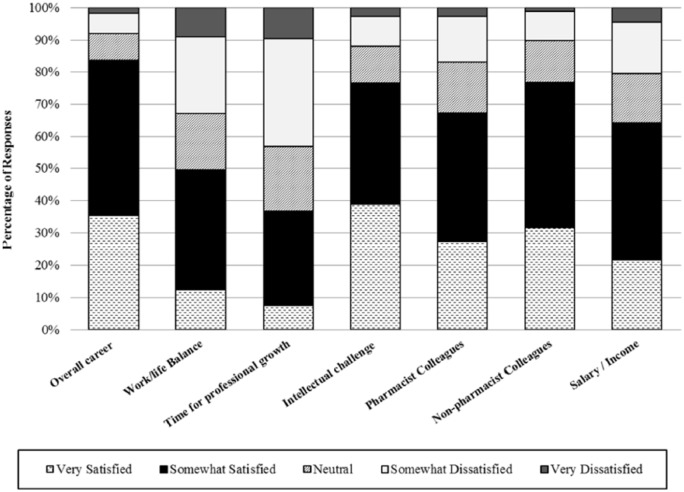

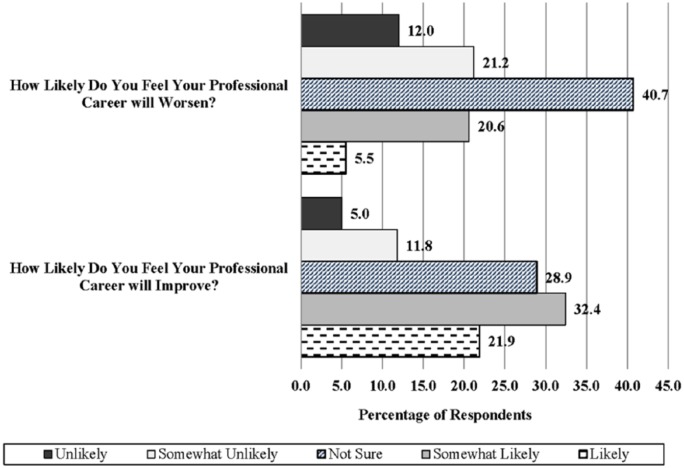

A detailed breakdown of responses for the survey sections related to professional stressors and job satisfaction is shown in Figures 1 and 2. The direction clinical pharmacists believe their careers will take is presented in Figure 3. Overall, 83.7% were somewhat to very satisfied with their careers as clinical pharmacists. A high percentage of respondents reported being satisfied with their pharmacist (67.2%) and nonpharmacist (76.6%) colleagues, their annual salary (64.0%), and the intellectual challenge of their job (76.6%). However, participants were either neutral or dissatisfied with their work/life balance (50.5%) and time allotted for professional growth (63.4%). At least 50% of respondents felt that too many hours worked (71.7%), inadequate research time (51.7%), inadequate administrative time (59.6%), and too many nonclinical duties (51.5%) were professional stressors that had a moderate to large impact on their careers.

Figure 1.

Response to questions for professional stressors (Online Appendix, Section 2).

Figure 2.

Response to questions for professional satisfaction (Online Appendix, Section 3).

Figure 3.

Perceptions among clinical pharmacists on the future direction of their career (Online Appendix, Section 5).

The burnout rate overall was 61.2% (Table 1) and largely driven by high emotional exhaustion (52.9%). High depersonalization was reported in 32.6% of participants. Upon univariate analysis, a smaller percentage of those who were burned out reported being married or in a stable relationship (65.3% vs 72.5%; P = .02). Those who were burned out were less likely to have children (39.1% vs 49.2%; P = .002), work more median hours each week (45 vs 50; P < .001), and were more likely to be certified by the Board of Pharmacy Specialties (68% vs 76.2%; P = .005). There were no differences observed in the burnout analysis related to hospital setting or practice area. Overall, numerous daily duties and professional stressors were found to be different in the burnout analysis and are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Respondents Based Upon Burnout.

| Characteristics | Not burned out (n = 378) | Burned out (n = 596) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 39 ± 10.6 | 36.7 ± 7.9 | <.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 261 (69.0) | 416 (69.8) | .80 |

| Family information, n (%) | |||

| Married/stable partner | 274 (72.5) | 389 (65.3) | .02 |

| Children | 186 (49.2) | 233 (39.1) | .002 |

| Ever divorced | 29 (7.7) | 38 (6.4) | .44 |

| Full-time employee, n (%) | 364 (96.3) | 585 (98.2) | .07 |

| Hospital setting, n (%) | |||

| University hospital | 169 (44.7) | 288 (48.3) | .27 |

| Academic community hospital | 116 (30.7) | 184 (30.9) | .95 |

| Nonacademic community hospital | 75 (19.8) | 99 (16.6) | .20 |

| Government/veterans hospital | 7 (1.9) | 11 (1.8) | .99 |

| Other | 11 (2.9) | 14 (2.3) | .59 |

| Practice duration, y | 8 (4-18) | 8 (5-13) | .30 |

| Completed postgraduate training, n (%) | 209 (55.3) | 357 (59.9) | .16 |

| Duration, y | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | |

| Workload characteristics | |||

| Hours worked per week | 45 (40-50) | 50 (42.3-50) | <.001 |

| Average weekends worked per year | 8 (0-15) | 10 (1-15) | .10 |

| Average days on call per month | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-4) | .003 |

| Payment structure, n (%) | |||

| Salaried employee | 293 (77.5) | 481 (80.7) | .23 |

| Overtime eligible | 93 (24.6) | 143 (24.0) | .83 |

| Certified by the Board of Pharmacy Specialties, n (%) | 257 (68.0) | 454 (76.2) | .005 |

| Multiple certifications, n (%) | 36 (9.5) | 63 (10.6) | .60 |

| Fellowship status, n (%) | 29 (7.7) | 28 (4.7) | .05 |

| Daily duties, n (%) | |||

| Didactic lecturing | 150 (39.7) | 278 (46.6) | .03 |

| Formal pharmacist consultation | 206 (54.5) | 364 (61.1) | .04 |

| Daily rounding | 253 (66.9) | 430 (72.1) | .08 |

| Medical staff committee involvement | 205 (54.2) | 366 (61.4) | .03 |

| Medication reconciliation | 188 (49.7) | 340 (57.0) | .03 |

| Nutrition support consultation | 79 (20.9) | 129 (21.6) | .78 |

| Order verification | 221 (58.5) | 387 (64.9) | .04 |

| Pharmacy committee involvement | 294 (77.8) | 486 (81.5) | .15 |

| Research and publication | 194 (51.3) | 348 (58.4) | .03 |

| Residency director/coordinator | 49 (13.0) | 124 (20.8) | .002 |

| Residency precepting | 272 (72.0) | 477 (80.0) | .004 |

| Student pharmacist precepting | 323 (85.4) | 523 (87.8) | .30 |

| Current area of practice, n (%) | |||

| Administration | 27 (7.1) | 50 (8.4) | .48 |

| Cardiology | 30 (7.9) | 61 (10.2) | .23 |

| Critical care | 108 (28.6) | 162 (27.2) | .64 |

| Emergency medicine | 40 (10.6) | 84 (14.1) | .11 |

| Generalist | 20 (5.3) | 19 (3.2) | .10 |

| Infectious disease | 41 (10.8) | 58 (9.7) | .56 |

| Internal medicine | 34 (9.0) | 59 (9.9) | .64 |

| Oncology | 36 (9.5) | 38 (6.4) | .07 |

| Othera | 78 (20.6) | 94 (15.8) | .06 |

| Pediatrics | 40 (10.6) | 72 (12.1) | .48 |

| Solid organ transplant | 21 (5.6) | 40 (6.7) | .47 |

| Overall satisfied with career | 345 (91.3) | 470 (78.9) | <.001 |

| Professional stressors | |||

| Inadequate research time | 152 (40.2) | 352 (59.1) | <.001 |

| Inadequate administrative time | 159 (42.1) | 422 (70.8) | <.001 |

| Inadequate teaching time | 107 (28.3) | 336 (56.4) | <.001 |

| Too many students | 84 (22.2) | 202 (33.9) | <.001 |

| Too many residents | 47 (12.4) | 153 (25.7) | <.001 |

| Low salary | 93 (24.6) | 231 (38.8) | <.001 |

| Hostile work environment | 67 (17.7) | 265 (44.5) | <.001 |

| Uncertainty of health care reform | 47 (12.4) | 188 (31.5) | <.001 |

| Inadequate office space | 92 (24.3) | 226 (37.9) | <.001 |

| Too little vacation | 61 (16.1) | 222 (37.2) | <.001 |

| Medication errors | 42 (11.1) | 152 (25.5) | <.001 |

| Too many nonclinical duties | 120 (31.7) | 382 (64.1) | <.001 |

| Difficult nonpharmacist colleagues | 57 (15.1) | 196 (32.9) | <.001 |

| Difficult pharmacist colleagues | 86 (22.8) | 304 (51.0) | <.001 |

| Contributions underappreciated | 80 (21.2) | 290 (48.7) | <.001 |

| Too much focus on cost | 98 (25.9) | 274 (46.0) | <.001 |

| Positive work/life balance | 278 (73.5) | 204 (34.2) | <.001 |

| Time for professional growth | 200 (52.9) | 157 (26.3) | <.001 |

| Intellectually challenged at work | 314 (83.1) | 432 (72.5) | <.001 |

| Spouse not understanding of job demands | 2 (0.6) | 10 (2.2) | .07 |

Responses for generalist, nutrition support, informatics, pain/palliative medicine, geriatrics, medication/safety, drug information, surgery, and other were combined due to small number within each category.

Factors Independently Associated With Burnout

The logistic regression model used to generate factors independently associated with burnout demonstrated an acceptable ability to differentiate between all outcomes and showed no evidence of lack of fit based on the nonsignificant Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic. Five factors were found to be independently associated with burnout among hospital clinical pharmacists, the majority of which were subjective variables (Table 3). Age was the only objective factor and was shown to be protective against burnout (OR: 0.96). Too many nonclinical duties (OR: 2.3) was associated with the highest odds of burnout. Other factors such as uncertainty regarding health care reform (OR: 2.0), inadequate time for teaching (OR: 1.8) and administrative activities (OR 1.9), difficult pharmacist colleagues (OR: 2.1), and feeling that one’s contributions were underappreciated by others (OR: 2.2) were also found to independently increase the odds of burnout.

Table 3.

Multivariable Logistic Regression of Burnout.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.96 | 0.95-0.98 |

| Inadequate administrative time | 1.9 | 1.4-2.6 |

| Inadequate teaching time | 1.8 | 1.3-2.5 |

| Uncertainty of health care reform | 2.0 | 1.4-3.1 |

| Difficult pharmacist colleagues | 2.1 | 1.5-2.9 |

| Contributions underappreciated | 2.2 | 1.6-3.1 |

| Too many nonclinical duties | 2.3 | 1.7-3.2 |

Note. All other intangible perception variables with P < .2 from univariate analysis did not predict outcome.

Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit = 0.1; area under the receiver operator characteristic curve (95% confidence interval) = 0.79 (0.76-0.82).

Discussion

Our pilot study used a validated scale to assess burnout among clinical pharmacists who practice in the hospital setting within the United States and aimed to determine the feasibly of surveying this large group of health care professionals. We report a burnout rate of 61.2%, one of the highest reported rates of burnout among any medical specialty in the United States (Table 4). Interestingly, the only groups with higher reported rates of burnout primarily sampled physicians enrolled in residency training programs.18,19 While the overall response rate was low at 11.4%, we noted several key points that warrant further research.

Table 4.

Burnout Rates of US Health Care Professionals.

| Specialty | Burnout rate, % | No. of participants (response rate, %) |

|---|---|---|

| Army health care providers20,a | 69.8 | 53 (33) |

| General surgery resident physicians18 | 69 | 665 (—) |

| PGY1 physicians19 | 68 | 31 (60) |

| Rural physician assistants21 | 64 | 161 (11.3) |

| Hospital clinical pharmacists (current study) | 60.8 | 1077 (14.7) |

| Neurosurgeons3 | 57 | 783 (24) |

| Clinical oncologists22 | 45 | 1490 (50) |

| Infectious diseases physicians23 | 44 | 1840 (46) |

| Pharmacy practice faculty24 | 41.3 | 758 (32.7) |

| General surgeons1 | 40 | 7905 (32) |

| Transplant surgeons25 | 38 | 259 (35) |

| Emergency medicine physician assistants26 | 35.6 | 160 (40.3) |

| Gynecologic oncologists27 | 32 | 369 (34) |

| Emergency medicine physicians28 | 32 | 193 (43) |

| Plastic surgeons29 | 29 | 505 (71) |

| Orthopedic surgeons30 | 28 | 264 (24) |

| Surgical oncologists31 | 28 | 549 (36) |

| Neonatal intensive care unit providers32,b | 26 | 2073 (62.9) |

| Neonatal critical care physicians32 | 15 | 204 (—) |

| Ophthalmologists serving as department chairs33 | 9 | 101 (77) |

Combat medics, physicians, and physician assistants.

Nurses, nurse practitioners, respiratory care providers, and physicians.

Prior to our study, there was scarce evidence regarding the rate of burnout among pharmacists. A 1996 survey of a select group of hospital pharmacists showed that the amount of clinical activities in hospital pharmacist job duties was positively correlated with job satisfaction. In addition, job dissatisfaction increased as distributive functions increased.34 Among a sample of Arizona pharmacists in institutional and ambulatory care settings, job satisfaction was influenced by perceived utilization of skills, staffing, and education level. Practice setting, job title, and age were significantly related to perceived utilization of skills.35 A study of graduates from a specific pharmacy program found that those graduates working primarily in community chain store settings reported greater levels of burnout than those working in the hospital setting. Furthermore, they found that respondents who performed primarily nondistributive duties experienced lower levels of burnout than those involved primarily in drug distribution.36 Among US pharmacy practice faculty, 41.3% of participants reported high emotional exhaustion scores.24 This study demonstrates a large change in burnout from an earlier study of pharmacy faculty that found a burnout rate near 16%.37 It is worth noting that this study utilized the MBI designed for educational professionals and not health care, which employs different threshold values for burnout.24 While assessment of burnout among US pharmacists has been limited, there have been several studies of burnout in other countries. A survey of 50 Iranian clinical pharmacists found that job stress and burnout were strongly correlated, although they did not report an actual burnout rate.38 Australian hospital pharmacists had high levels of burnout based on emotional exhaustion (39%) and personal accomplishment (49%), while the majority of pharmacists felt low levels of burnout based on depersonalization (60%).39 A study of community pharmacists from India reported a burnout rate of 44%, and another of community pharmacists in Turkey found low levels of all 3 MBI domains.40,41 In Japan, a recent study of hospital pharmacists found a burnout rate of 49.2%, although it utilized different methodology to define burnout.42 Finally, a recent French study found a burnout rate of 56.2% of the approximately 1300 community pharmacists surveyed.43 Our study adds to the evidence regarding factors associated with burnout among pharmacists and has several key notable differences. First, we attempted to survey a group of pharmacists who practice primarily in the inpatient hospital setting and to quantify factors that may contribute to burnout in this population. Second, we used a survey design similar to that of many major physicians groups that has been widely validated in recent literature. We formulated our survey similar to that of physicians given the lack of burnout studies among other members of the health care team. Given the high burnout rate in our study, further research is needed to better understand the impact of burnout among inpatient hospital clinical pharmacists on factors such as medication errors, early retirement, or diminished patient satisfaction.

Our study also provides additional insight into factors that may contribute to burnout, which appears to be largely influenced by subjective factors. Many objective factors, such as participation in order verification or directing a pharmacy residency program, were noted as being increased in those who were burned out in the univariate analysis. However, none of these factors were found to independently predict burnout once they were combined into models with subjective factors previously discussed. The strongest predictor of burnout in this analysis was “too many nonclinical duties,” which increased the odds of burnout by 130%. In addition, “inadequate time for teaching,” “inadequate administration time,” “difficult pharmacist colleagues,” and “contributions underappreciated” were all independently associated with burnout. Finally, “uncertainty of health care reform” was also determined to be an independent predictor of burnout. However, our survey did not differentiate between changes to the Affordable Care Act and pharmacy practice model changes specifically. It was also conducted prior to the 2016 Presidential election, which has created further ambiguity regarding health care reform in the United States. Despite the high rate of burnout reported, we observed an overall high rate of career satisfaction (83.7%), which provides further support to the subjective nature of diagnosing burnout and is similar to other studies.3,4,23 The transient nature of burnout may mean that, at the time a respondent completed our survey, they may have suffered from burnout while remaining satisfied with their overall career.

Our study is not without several limitations. While the total number of respondents was one of the highest reported in the medical literature, our overall response rate was low considering the total number of individuals who received an invitation to complete the survey. Unfortunately, we are unable to report a response rate of those who our study was actually applicable to complete, as the query generated by ACCP was only able to tell us the total number of individuals who received the invitation and may have included students, residents, and those who do not practice inpatient clinical pharmacy. We offered no incentive(s) to participate in this survey as other areas have, which may have impacted our response rate. In addition, we relied on survey participants to self-identify as “clinical pharmacists.” The survey link could also have been accessed multiple times by respondents, although a review of all collected data did not yield any concerns that a single respondent completed multiple surveys. Our study may also suffer from selection bias whereby those who completed the survey may be different as a group compared with those who did not complete the survey. For example, those who currently suffer from burnout or career dissatisfaction may be less likely to take the time to complete a voluntary survey, which would underestimate the prevalence of burnout. As the survey title included the word “burnout,” those who completed the survey may have done so because they self-identified as being burnt out. While results of the present study are internally valid, the results may not be completely generalizable to those who did not complete the survey. As with any survey study, some of the questions may not have been clearly understood by all participants and impacted our analysis. In addition, we did not define “clinical” and “nonclinical” duties within the survey and instead relied upon each respondent’s own definition of these variables. We also did not address the impact of professional engagement outside of day-to-day work duties on burnout. Finally, as our survey aimed to determine an initial burnout rate among hospital clinical pharmacists, we did not provide assessment between the rate of burnout and perceived medical errors.

Conclusions

The rate of burnout was high in this pilot survey of US clinical pharmacists practicing in the inpatient hospital setting. However, the overall response rate was low at 11.4%. We hope the results of our study will generate further research regarding the impact of burnout on clinical pharmacists, particularly related to the negative influence of burnout on the lives of clinical pharmacists and on medication errors that occur, and lead to further research that may yield a larger response rate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Daniel Aistrope, PharmD, BCACP (Director of Clinical Practice Advancement at ACCP) for his assistance with determining the exact response rate of the survey.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplementary material is available for this article online.

References

- 1. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250:463-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maslach C, Leiter M. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3. McAbee JH, Ragel BT, McCartney S, et al. Factors associated with career satisfaction and burnout among US neurosurgeons: results of a nationwide survey. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:161-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balch CM, Freischlag JA, Shanafelt TD. Stress and burnout among surgeons: understanding and managing the syndrome and avoiding the adverse consequences. Arch Surg. 2009;144:371-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:358-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006;296:1071-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors’ perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1017-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jones JW, Barge BN, Steffy BD, Fay LM, Kunz LK, Wuebker LJ. Stress and medical malpractice: organizational risk assessment and intervention. J Appl Psychol. 1988;73:727-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kent GG, Johnson AG. Conflicting demands in surgical practice. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1995;77:235-238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campbell DA, Jr, Sonnad SS, Eckhauser FE, Campbell KK, Greenfield LJ. Burnout among American surgeons. Surgery. 2001;130:696-702;discussion 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shanafelt TD, Gradishar WJ, Kosty M, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:678-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams ES, Manwell LB, Konrad TR, Linzer M. The relationship of organizational culture, stress, satisfaction, and burnout with physician-reported error and suboptimal patient care: results from the MEMO study. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32:203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. American College of Clinical Pharmacy. The definition of clinical pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:816-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Langebrake C, Ihbe-Heffinger A, Leichenberg K, et al. Nationwide evaluation of day-to-day clinical pharmacists’ interventions in German hospitals. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35:370-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seden K, Kirkham JJ, Kennedy T, et al. Cross-sectional study of prescribing errors in patients admitted to nine hospitals across North West England. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shulman R, McKenzie CA, Landa J, et al. Pharmacist’s review and outcomes: treatment-enhancing contributions tallied, evaluated, and documented (PROTECTED-UK). J Crit Care. 2015;30:808-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee RT, Ashforth BE. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81:123-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elmore LC, Jeffe DB, Jin L, Awad MM, Turnbull IR. National survey of burnout among US general surgery residents. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223:440-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gunasingam N, Burns K, Edwards J, Dinh M, Walton M. Reducing stress and burnout in junior doctors: the impact of debriefing sessions. Postgrad Med J. 2015;91:182-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Walters TA, Matthews EP, Dailey JI. Burnout in army health care providers. Mil Med. 2014;179:1006-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Benson MA, Peterson T, Salazar L, et al. Burnout in rural physician assistants: an initial study. J Physician Assist Educ. 2016;27:81-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shanafelt TD, Raymond M, Kosty M, et al. Satisfaction with work-life balance and the career and retirement plans of US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1127-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deckard GJ, Hicks LL, Hamory BH. The occurrence and distribution of burnout among infectious diseases physicians. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:224-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. El-Ibiary SY, Yam L, Lee KC. Assessment of burnout and associated risk factors among pharmacy practice faculty in the United States. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bertges Yost W, Eshelman A, Raoufi M, Abouljoud MS. A national study of burnout among American transplant surgeons. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1399-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bell RB, Davison M, Sefcik D. A first survey. Measuring burnout in emergency medicine physician assistants. JAAPA. 2002;15:40-42, 45,-48, 51-52 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rath KS, Huffman LB, Phillips GS, Carpenter KM, Fowler JM. Burnout and associated factors among members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:824.e1-824.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuhn G, Goldberg R, Compton S. Tolerance for uncertainty, burnout, and satisfaction with the career of emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:106-113.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Streu R, Hansen J, Abrahamse P, Alderman AK. Professional burnout among US plastic surgeons: results of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72:346-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sargent MC, Sotile W, Sotile MO, Rubash H, Barrack RL. Quality of life during orthopaedic training and academic practice. Part 1: orthopaedic surgery residents and faculty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2395-2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuerer HM, Eberlein TJ, Pollock RE, et al. Career satisfaction, practice patterns and burnout among surgical oncologists: report on the quality of life of members of the Society of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3043-3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Profit J, Sharek PJ, Amspoker AB, et al. Burnout in the NICU setting and its relation to safety culture. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:806-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cruz OA, Pole CJ, Thomas SM. Burnout in chairs of academic departments of ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:2350-2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Olson DS, Lawson KA. Relationship between hospital pharmacists’ job satisfaction and involvement in clinical activities. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1996;53:281-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cox ER, Fitzpatrick V. Pharmacists’ job satisfaction and perceived utilization of skills. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1733-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barnett CW, Hopkins WA, Jr, Jackson RA. Burnout experienced by recent pharmacy graduates of Mercer University. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1986;43:2780-2784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jackson R, Barnett C, Stajich G, Murphy J. An analysis of burnout among school of pharmacy faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 1993;57:9-17. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eslami A, Kouti L, Javadi M, Assarian M, Eslami K. An investigation of job stress and job burnout in Iranian clinical pharmacist. J Pharm Care. 2015;3:21-25. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Muir P, Bortoletto D. Burnout among Australian hospital pharmacists. J Pharm Pract Res. 2007;37:187-189. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jocic D, Krajnovic D. State anxiety, stress and burnout syndrome among community pharmacists: relation with pharmacists’ attitudes and beliefs. Indian J Pharm Edu Res. 2014;48:9-15. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Calgan Z, Aslan D, Yegenoglu S. Community pharmacists’ burnout levels and related factors: an example from Turkey. Int J Clin Pharm. 2007;33:92-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Higuchi Y, Inagaki M, Koyama T, et al. A cross-sectional study of psychological distress, burnout, and the associated risk factors in hospital pharmacists in Japan. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Balayssac D, Pereira B, Virot J, et al. Burnout, associated comorbidities and coping strategies in French community pharmacies—BOP study: a nationwide cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.