To the Editor:

Rare genetic variation in genes related to telomere biology has been implicated in 10–20% of familial interstitial pneumonia (FIP), the inherited form of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (1). Recently, heterozygous rare variants (RVs) in the gene encoding polyadenylation-specific RNase deadenylation nuclease (PARN) were reported in six unrelated families with pulmonary fibrosis (2), consistent with reports of biallelic PARN RVs in children with dyskeratosis congenita (3–5). Subsequently, heterozygous PARN RVs were identified in five patients with sporadic idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) among 262 patients who underwent whole-exome sequencing (6).

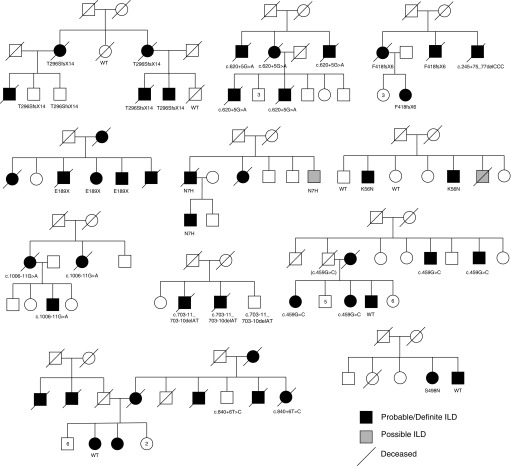

We queried whole-exome sequencing data from genomic DNA obtained from 188 unrelated FIP kindreds (7) for RVs in PARN, identified variants with a minor allele frequency <0.001 among Caucasian patients in the Exome Aggregation Consortium database, and confirmed these RVs by Sanger sequencing. Using this approach, we found 13 unique PARN RVs in 12/188 (6.4%) unrelated families (Figure 1); seven families (3.7%) had variants predicted to be protein-altering (frameshift, nonsense, splicing, missense; Table 1). In five of these families (2.6% of the cohort), PARN RVs identified as likely to be damaging fully cosegregated with disease in individual family members. These PARN RVs included one nonsense, one frameshift, one splicing, and two missense variants. The two missense variants, Asn7His and Lys56Ans, are conserved and predicted to affect protein function. For the c.620+5G>A splicing variant, we generated immortalized lymphocytes and performed complementary DNA sequencing; this confirmed that this variant results in alternative splicing, which is likely to affect PARN structure and function.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of familial interstitial pneumonia kindreds with polyadenylation-specific RNase deadenylation nuclease (PARN) variants. Variant information is denoted below individuals who had DNA available for sequencing. Numbers inside pedigree symbols indicate the number of other siblings of the same sex and affected status. ILD = interstitial lung disease; WT = wild type.

Table 1.

PARN Rare Variants Identified by Whole-Exome Sequencing

| Variant Type | Variant (Protein) | Variant (DNA) | Splicing Effect | ExAC DB Frequency | PP2 | Affected Carrier Telomere % | Segregates with Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of function variants | |||||||

| Frameshift | p.Thr296SerfsX14 | c.887_888delCA | NA | None | NA | 2%, 3% | Yes |

| Splice | NA | c.620+5G>A | Yes | None | NA | 1% | Yes |

| Nonsense | Glu189Stop | c.565G>T | NA | None | NA | 1%, 1%, 12% | Yes |

| Frameshift | p.Phe418PhefsX6 | c.1251delT | NA | None | NA | 15% | No* |

| Variants of uncertain significance | |||||||

| Missense | Asn7His | c.19A>C | Unknown | None | 1 | 3% | Yes |

| Missense | Lys56Asn | c.168G>C | NA | G=1/C=66,604 | 0.667 | 5%, 5% | Yes |

| Intron | NA | c.178-3C>T | No | None | NA | 7%, 9% | Yes |

| Intron | NA | c.703-11_703-10delAT | Unknown | None | NA | 1%, 2% | Yes |

| Intron | NA | c.245+75_245+77delCCC | Unknown | NA | NA | 15% | No* |

| Synonymous | Ala153Ala | c.459G>C | Unknown | None | NA | 21%, 22% | No† |

| Intron | NA | c.840+6T>C | Unknown | G=33/A=66,636 | NA | 1% | No‡ |

| Intron | NA | c.1006-11G>A | Unknown | G=3/A=65,604 | NA | 1%, 2% | Yes¶ |

| Missense | Ser498Asn | c.1493G>A | NA | G=20/A=60,728 | 0.996 | 1% | No |

Definition of abbreviations: ExAC DB = Exome Aggregation Consortium database; NA = not applicable; PARN = polyadenylation-specific RNase deadenylation nuclease; PP2 = PolyPhen2; TERT = telomerase reverse transcriptase.

p.Phe418PhefsX6 was not detected in one affected participant; however, this subject carried an intronic variant of uncertain significance, c.245+75_245+77delCCC.

One subject did not carry c.459G but had a family history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in both parental lines.

Two subjects did not carry c.840+6T>C; however, they had a family history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in both parental lineages.

This family also has a novel segregating TERT variant Thr839Lys.

Surprisingly, in three families, intronic PARN variants that did not appear to affect mRNA splicing cosegregated with disease. Complementary DNA sequencing demonstrated that c.178−3C>T does not affect splicing, indicating this is likely benign. Another intronic variant, c.703-11_703-10delAT, is located in an intron near a splice site but is not predicted to alter the canonical splice site or create a cryptic splice site. A third intronic PARN variant c.1006−11G>A cosegregated with disease in one family but is not predicted to alter splicing. In this family, however, affected subjects share a novel cosegregating RV in the gene telomerase reverse transcriptase (Thr839Lys). Although available evidence suggests these intronic RVs are benign, their cosegregation with disease and association with otherwise unexplained short telomeres in affected individuals raises the possibility that these intronic variants have effects on PARN expression or other regulatory mechanisms.

In the remaining four families, PARN RVs did not fully segregate with disease. In two of these families, there was a family history of IPF through both parental lineages, making it possible that affected individuals inherited a different genetic risk factor through each parental line. In one family, an intronic PARN RV that could affect splicing (c.245+75_245+77delCCC) was identified in a patient with IPF, whereas the other affected individuals shared a frameshift variant (Phe418PhefsX6). In a different family, an affected individual with short peripheral blood mononuclear cell telomeres carried a missense RV (Ser498Asn) that is predicted to be deleterious (PolyPhen2 0.996) (8), but the RV was not identified in the other family member with disease.

We measured peripheral blood mononuclear cell telomere length in all affected individuals from these families from whom sufficient DNA was available and found that all had telomere shortening adjusted for age (Table 1). Thirteen of the 18 subjects tested (72%) had telomere length below the 10th percentile, whereas the others ranged from the 12th to the 22nd percentile. All these families were of Caucasian ancestry, and 62% of affected subjects were men. The median age at diagnosis was 60 years (range, 42–82 years), slightly younger than the median age of onset in our entire cohort of patients with FIP (66 years) (7). Forty-three percent of affected subjects had a history of cigarette smoking. Baseline FVC was 68.5% (±17.7%, SD) predicted, and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide was 66.5% (±24.0%). Among individuals for whom high-resolution computed tomography was available for review, all had possible or definite usual interstitial pneumonia based on American Thoracic Society guidelines (9).

Recent work has indicated that PARN polyadenylates the 3′ end of telomerase RNA component (known as TERC or hTR), which serves as the template for telomerase reverse transcriptase–mediated telomere replication. Presumably, PARN mutations destabilize hTR levels (10) and lead to reduced telomerase activity through a haploinsufficiency mechanism similar to dyskerin (DKC1) mutations (11); further investigation will be needed to determine whether PARN plays other roles in telomere biology. Exciting recent work suggests inhibiting RNA-decay mechanisms may reverse these cellular phenotypes, suggesting a possible novel approach to personalizing therapy in pulmonary fibrosis (12, 13).

Our data provide independent confirmation of genetic variation in PARN as an important influence on FIP risk. In addition, these findings underscore the genetic complexity and heterogeneity of FIP. Given this complexity and the difficulty in assigning causality to variants of uncertain significance in affected individuals, our current practice is, after genetic counseling, to perform clinical genetic testing for PARN or other telomere pathway genes along with telomere length measurement, which provides some evidence regarding the functional importance of telomerase pathway genetic variants (1). However, as illustrated by the families reported here, even with the combination of telomere length measurement and genetic testing, assignment of disease risk to individual RVs may be difficult. As the spectrum of genetic risk for familial and sporadic IPF is expanded, we anticipate that enhanced understanding of the complex genetic influences underlying this disease will improve our ability to use genetic information in the care of these patients.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health, NHLBI grants K08HL130595 (J.A.K.), P01HL92870 (T.S.B.), R01HL085317 (T.S.B.), and HL0097163 (D.A.S.); Vanderbilt University Clinical and Translational Science award UL1 RR024975 (J.D.C.); Department of Veterans Affairs (T.S.B. and D.A.S.); Francis Family Foundation (J.A.K.); and the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (J.A.K.).

Author Contributions: J.A.K. designed the study, performed experiments, collected data, analyzed data, interpreted data, and wrote and revised the manuscript; S.R. performed experiments and analyzed and interpreted data; C.M. collected and analyzed data; K.K.B. collected data, analyzed data, interpreted data, and revised the manuscript; D.A.S. collected data, analyzed data, interpreted data, and revised the manuscript; M.I.S. collected data and revised the manuscript; J.E.L. designed the study, collected data, analyzed data, interpreted data, and revised the manuscript; J.A.P designed the study, collected data, analyzed data, interpreted data, and revised the manuscript; T.S.B. designed the study, collected data, analyzed data, interpreted data, and wrote and revised the manuscript; and J.D.C. designed the study, performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote and revised the manuscript.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0635LE on April 17, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Kropski JA, Young LR, Cogan JD, Mitchell DB, Lancaster LH, Worrell JA, Markin C, Liu N, Mason WR, Fingerlin TE, et al. Genetic evaluation and testing of patients and families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1423–1428. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201609-1820PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuart BD, Choi J, Zaidi S, Xing C, Holohan B, Chen R, Choi M, Dharwadkar P, Torres F, Girod CE, et al. Exome sequencing links mutations in PARN and RTEL1 with familial pulmonary fibrosis and telomere shortening. Nat Genet. 2015;47:512–517. doi: 10.1038/ng.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burris AM, Ballew BJ, Kentosh JB, Turner CE, Norton SA, Giri N, Alter BP, Nellan A, Gamper C, Hartman KR, et al. NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory; NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group. Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome due to PARN mutations: fourteen years of follow-up. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;56:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhanraj S, Gunja SM, Deveau AP, Nissbeck M, Boonyawat B, Coombs AJ, Renieri A, Mucciolo M, Marozza A, Buoni S, et al. Bone marrow failure and developmental delay caused by mutations in poly(A)-specific ribonuclease (PARN) J Med Genet. 2015;52:738–748. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tummala H, Walne A, Collopy L, Cardoso S, de la Fuente J, Lawson S, Powell J, Cooper N, Foster A, Mohammed S, et al. Poly(A)-specific ribonuclease deficiency impacts telomere biology and causes dyskeratosis congenita. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2151–2160. doi: 10.1172/JCI78963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrovski S, Todd JL, Durheim MT, Wang Q, Chien JW, Kelly FL, Frankel C, Mebane CM, Ren Z, Bridgers J, et al. An exome sequencing study to assess the role of rare genetic variation in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:82–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201610-2088OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cogan JD, Kropski JA, Zhao M, Mitchell DB, Rives L, Markin C, Garnett ET, Montgomery KH, Mason WR, McKean DF, et al. Rare variants in RTEL1 are associated with familial interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:646–655. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1510OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, Colby TV, Cordier JF, Flaherty KR, Lasky JA, et al. ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moon DH, Segal M, Boyraz B, Guinan E, Hofmann I, Cahan P, Tai AK, Agarwal S. Poly(A)-specific ribonuclease (PARN) mediates 3′-end maturation of the telomerase RNA component. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1482–1488. doi: 10.1038/ng.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kropski JA, Mitchell DB, Markin C, Polosukhin VV, Choi L, Johnson JE, Lawson WE, Phillips JA, III, Cogan JD, Blackwell TS, et al. A novel dyskerin (DKC1) mutation is associated with familial interstitial pneumonia. Chest. 2014;146:e1–e7. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyraz B, Moon DH, Segal M, Muosieyiri MZ, Aykanat A, Tai AK, Cahan P, Agarwal S. Posttranscriptional manipulation of TERC reverses molecular hallmarks of telomere disease. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:3377–3382. doi: 10.1172/JCI87547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shukla S, Schmidt JC, Goldfarb KC, Cech TR, Parker R. Inhibition of telomerase RNA decay rescues telomerase deficiency caused by dyskerin or PARN defects. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:286–292. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]