Abstract

Patient: Female, 49

Final Diagnosis: Medication related osteonecrosis of the jaw

Symptoms: Painful bone exposure • pus discharge

Medication: Infliximab

Clinical Procedure: Surgical removal of necrotic bone

Specialty: Surgery

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) is a severe adverse drug reaction, occurring in patients undergoing treatments with antiresorptive or antiangiogenic agents, such as bisphosphonates, denosumab, or bevacizumab, for different oncologic and non-oncologic diseases. The aim of this study was to report a case of MRONJ in a patient taking infliximab, an anti-TNF-α antibody used to treat Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and plaque psoriasis.

Case Report:

A 49-year-old female patient affected by Crohn’s disease, who had been undergoing 250 mg intravenous infliximab every six weeks for 12 years, with no history of antiresorptive or antiangiogenic agent administration, came to our attention for post-surgical MRONJ, associated with a wide cutaneous necrotic area of her anterior mandible. Following antibiotic cycles, the patient underwent surgical treatment with wide bone resection and debridement of necrotic tissues; after prolonged follow-up (16 months), the patient completely healed without signs of recurrence.

Conclusions:

Prevention of MRONJ by dental check-up before and during treatments with antiresorptive treatments (bisphosphonates or denosumab) is a well-established procedure. Although further studies are required to confirm the role of infliximab in MRONJ, based on the results of this study, we propose that patients who are going to be treated with infliximab should also undergo dental check-up before starting therapy, to possibly avoid MRONJ onset.

MeSH Keywords: Bisphosphonate-Associated Osteonecrosis of the Jaw, Bone Density Conservation Agents, Crohn Disease

Background

Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) is a severe adverse drug reaction defined by the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) as “the presence of exposed necrotic bone or bone that can be probed through an intraoral or extra-oral fistula in the maxillofacial region, that has persisted for longer than eight weeks, occurring in patients undergoing treatment with antiresorptive or antiangiogenic agents with no history of radiation therapy or obvious metastatic disease to the jaws” [1].

MRONJ onset depends on different factors including duration of the antiresorptive/antiangiogenic therapy and oral or intravenous drug administration, with far more cases reported after intravenous infusion [2], presence of local risk factors such as tooth extraction, placement of dental implants, periapical surgery, or dental abscesses [3], concomitant treatment with corticosteroids, chemotherapies, and hormone therapy, presence of patient comorbidities such as immunodeficiency, diabetes mellitus, obesity, or hypercholesterolemia [4,5].

MRONJ has been known as bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) for a long time, because it was related to the administration of oral and intravenous bisphosphonates (BPs) for the treatment of osteoporosis, multiple myeloma, and metastatic cancer deposits. In 2014, a special committee of AAOMS recommended a change in nomenclature for MRONJ [1] due to the growing number of osteonecroses associated with other antiresorptive and antiangiogenic drugs [6]. Consequently, denosumab, bevacizumab, rituximab, adalimumab, and sunitinib were considered responsible for MRONJ in several publications [6–13], and it is reasonable to expect additional drugs to join this list over the next few years, with infliximab potentially being among them.

Infliximab is a chimeric human-murine IgG1 monoclonal antibody that acts as a tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitor; it is indicated for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, adult and pediatric Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis.

The aim of this study was to report a case of MRONJ in a patient affected by Crohn’s disease who had been undergoing infliximab administration for several years, but had never been administered with antiresorptive or antiangiogenic therapies.

Case Report

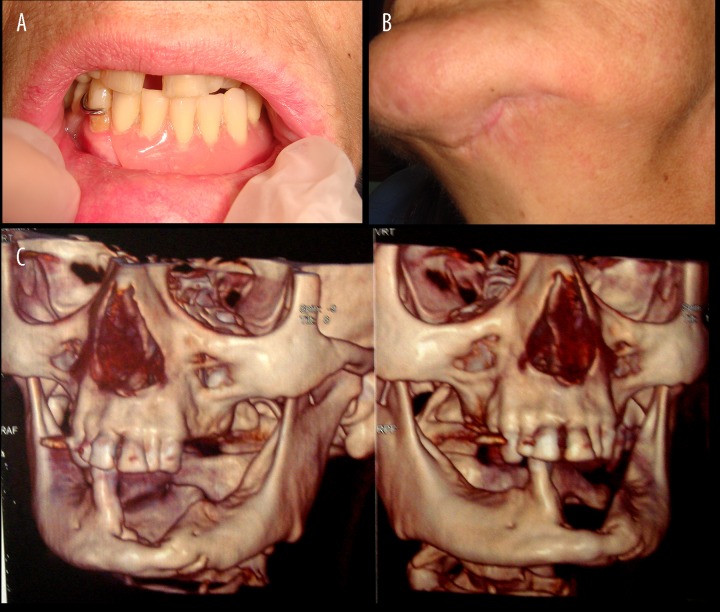

A 49-year-old female patient was referred to the Oral Surgery Unit of the Policlinic of Bari (Italy) on March 2016 for intra- and extra-oral necrotic bone exposures of the anterior mandible (Figure 1A, 1B), associated with submandibular swelling, pus discharge, and pain.

Figure 1.

Patient’s clinical features. Wide cutaneous necrotic area (A) with bone exposure and pus discharge, and (B) intraoral necrotic bone exposure on the anterior mandible in a female patient affected by Crohn’s disease, undergoing infliximab therapy. This shows the area were the teeth extractions was performed. The lesion was classified as stage 3 medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw according to the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons staging system [1].

The patient’s medical history revealed that in 2003 she was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and, therefore, salazopyrin (500 mg orally, three times a day) and mesalazine (800 mg orally, three times a day) were administered. Subsequently, from February 2004, due to poor response to treatments, infliximab (250 mg intravenous every six weeks) was prescribed. The patient had never undergone antiresorptive, antiangiogenic, or steroid therapies, and other comorbidities or risk factors, such as smoking and alcohol abuse, were excluded.

Odontostomatological clinical history revealed the extraction of three teeth (3.2, 3.1 and 4.1) due to periodontal disease on December 2015, without infliximab drop-out. Over the next two months, the patient complained of pain and mandibular swelling. Subsequently, on February 2016, due to worsening of the symptoms and to the onset of skin ulceration with extra-oral necrotic bone exposure of the anterior mandibular area, the patient was referred to our clinic.

Clinical examination highlighted a 3 cm painful bone exposure, from the 3.2 to 4.1 at post-extractive sites, with pus discharge. The use of dental probes and the leaking of saliva from the extra-oral ulcer allowed us to diagnose an intra-extra-oral fistula in the area of bone exposure.

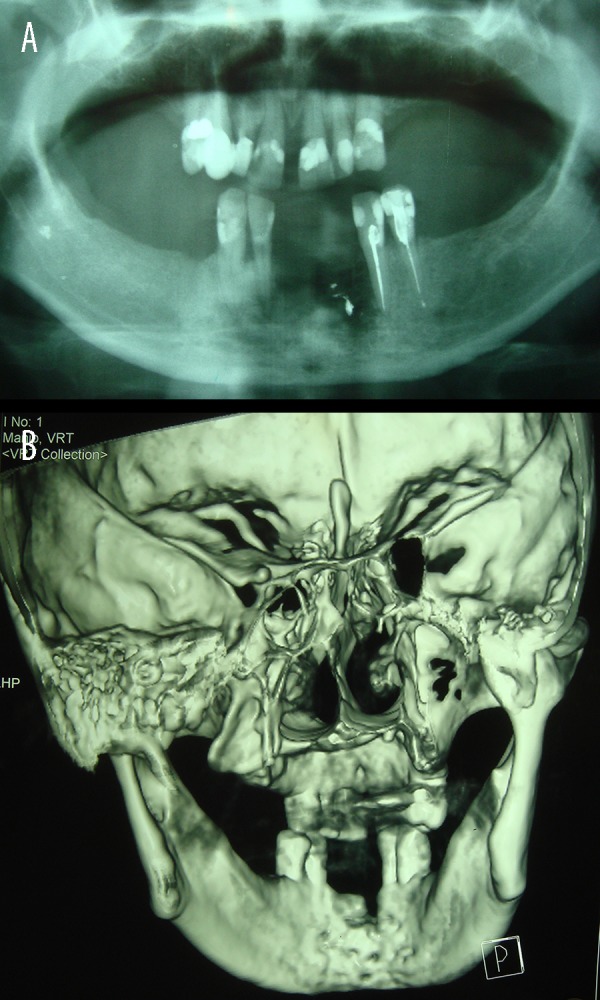

The radiological exam orthopantomography (Rx OPT) (Figure 2A) showed a poorly defined radiolucency in the area of bone exposure (3.2, 3.1 and 4.1 post-extraction sites) was detected, and enhanced multi-slice spiral computed tomography with 3D reconstruction (Figure 2B) showed an area of osteolysis of the alveolar process in the anterior mandible, involving the lingual cortical plate up to the inferior margin, while the facial cortical plate was preserved.

Figure 2.

Radiological exams, orthopantomography (A) and enhanced multi-slice spiral computed tomography (B) showed severe bone loss and resorption of the anterior mandible, in the region of bone exposure.

The severity of the symptoms and the clinical presentation allowed us to exclude the diagnosis of alveolar osteitis, while the presence of pus discharge ruled out the possibility of chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis. Also, based on routine blood tests, leukemia was ruled out, while other malignancies, such as osteosarcoma and lymphoma were considered unlikely in view of the strict correlation between teeth extraction and the onset of the clinical symptoms, the latter frankly pointing at the non-neoplastic origin of the process. Based on clinical examination and radiological imaging, a provisional diagnosis of MRONJ was formulated, and the lesion was classified as stage 3 according to the AAOMS staging system [1].

Based on these findings, infliximab treatment was suspended and the patient underwent three cycles of antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone (1 g/once a day by intramuscular injection) and metronidazole (500 mg/twice a day orally) for eight days, followed by 10 days of suspension.

Subsequently, the patient underwent surgical treatment under general anesthesia, consisting of anterior mandibular partial resection, involving the residual alveolar process (Figure 3A) and the lingual cortical plate up to its inferior margin, with preservation of the facial cortical plate. After resection, the bone surface was treated by a piezoelectric device to remove residual infected and necrotic tissues, to possibly prevent MRONJ recurrence. Finally, a gel compound composed of sodium hyaluronate and amino acids was put into the bone defect to reduce the healing time. Debridement of the cutaneous necrotic area was also performed, and an iodoform gauze was put into the external infected wound (Figure 3B), which was removed three days after the surgical treatment. Also, an additional cycle of antibiotics (as previously indicated) was prescribed.

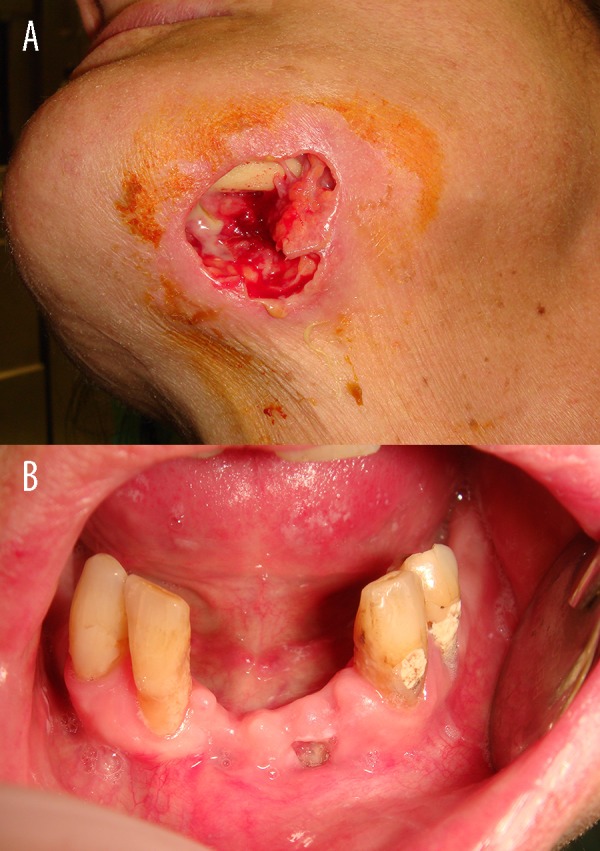

Figure 3.

Surgical treatment. Surgical removal of the necrotic alveolar process (A); a iodoform gauze was put into the external infected wound after debridement of the cutaneous necrotic area (B).

The surgical specimen was fixed in neutral-buffered formalin and sent to the Pathological Anatomy Unit of the Policlinic of Bari, where it was decalcified in formic acid (5% in distilled water) for 24 hours, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4-μm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. The histopathological analysis of the decalcified samples showed areas of bone necrosis with inflammatory cell infiltration and several basophilic bacterial colonies, empty Haversian canals without residual osteocytes/osteoblasts, and reduction of Haversian blood vessels, thus confirming the clinical diagnosis of MRONJ.

Following the surgical treatment, both intra- and extra-oral wounds healed without complications and without recurrence after 16 months of clinical and radiological follow-up (Figure 4A–4C). Rehabilitation with a removable prosthesis was chosen to guarantee functions and aesthetics, with good stabilization of the surgical sites.

Figure 4.

Intra- and extra-oral wound healing. Rehabilitation with a removable prosthesis was chosen to guarantee function and aesthetics (A). Clinical (B) and radiological (C) healing of surgical wound after 12-month follow-up are shown.

This study was performed in accordance to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by our institution ethics committee (Study no. 4599, Prot. 1528/C.E.); the patient released informed consent for the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and the possible use of the biologic samples for research purposes.

Discussion

MRONJ caused by intravenous and oral BPs has been extensively characterized over the last 13 years. To date, inhibitors of RANKL (denosumab) [8,14], of angiogenesis (bevacizumab and rituximab) [7,15,16], of tyrosine kinase receptors (sunitinib) [11], and of TNF (adalimumab) [10] have already been related to MRONJ in distinct case series, thus prompting the change in nomenclature from bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) to MRONJ.

We, hereby, report a case of infliximab-related MRONJ in a patient affected by Crohn’s disease, who had been first treated by salazopirine/mesalazine and subsequently by infliximab (250 mg intravenously every six weeks for 12 years), who had never received antiresorptive/antiangiogenic therapies. A similar case of MRONJ, possibly related to infliximab administration, was reported by Ebker et al. in 2013 in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis; nevertheless, the same patient had been simultaneously treated with BPs [17], thus leading the authors to stress the possible facilitating role of infliximab in the onset of MRONJ in patients taking BPs.

In the current case, MRONJ developed after years of infliximab treatment, in the absence of BPs administration and following teeth extraction. The lesion was staged as stage 3 according to the AAOMS staging system [1], due to its severity, with intra-oral bone exposure and with involvement of the cutaneous surface. Following multiple antibiotic cycles, the patient underwent surgical therapy with wide bone resection and debridement of the cutaneous area. The preservation of the facial cortical plate prevented mandibular fracture and after 16-months of clinical and radiological follow-up, the patient completely healed without recurrence (Figure 4A–4C). The histopathological analysis of the surgical specimen confirmed the diagnosis of MRONJ.

Infliximab is a genetically engineered chimeric human/mouse monoclonal antibody [18], which binds with high affinity to both the soluble and the transmembrane forms of human TNF-α, a key mediator of mucosal inflammation. Activities inhibited by anti-TNF-α antibodies include induction of interleukins, enhancement of leukocyte migration, and expression of adhesion molecules. Increased levels of TNF-α have been reported to be involved in active Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Infliximab has been increasingly used to treat all these inflammatory conditions [19]. In a recent review, Scheinfeld reported the most important side effects related to infliximab were: lymphoma, infectious diseases, congestive heart failure, demyelinating disease, lupus-like syndromes, induction of auto-antibodies, reactions at the injection site, and diabetes mellitus [13]. To date, the potential implications of infliximab treatment in patients receiving oral surgery have not been fully elucidated in the literature [19]. An extended clinical trial showed that anti-TNF biologics are related to better mucosal healing but, at the same time, they may interfere with bone physiology and turnover, and with wound repair [20]. TNF-α plays an important role in systemic bone loss and turnover, due to its ability to promote osteoclasts and osteoblasts activity [14]. Anti-TNF-α biologics possibly are responsible for bone turnover inhibition, probably by reduction of RANKL, thus resulting in osteoclast function inhibition, as already demonstrated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [10]. Such anti-TNF-α-mediated reduction of systemic bone loss may certainly increase the risk of MRONJ [14], similarly to what detected in patients taking BPs or denosumab, the latter also acting as inhibitors of osteoclast functions [21–24]. It is worth noting that anti-TNF-α treatments may facilitate infectious complications due to immunosuppression and, therefore, MRONJ occurrence in patient taking anti-TNF-α drugs may also result from “spreading of ongoing infections” [9].

Conclusions

Further studies are required to confirm the role of infliximab in MRONJ occurrence, but as recommended for patients undergoing treatment with BPs, denosumab, bevacizumab, or adalimumab [25], prevention of MRONJ by dental check-up before and during infliximab therapy is vital to prevent MRONJ occurrence, or to detect lesion at earlier stages, thus requiring less invasive treatments, and possibly manifesting lower recurrence rates.

Furthermore, in consideration of the increasing number of drugs which may facilitate MRONJ onset, the prescription of all biological drugs should require more attentive evaluation of well-known risk factors for MRONJ by all the prescribing specialists. Among the latter, the role of rheumatologists is especially important due to the large number of rheumatologic diseases which require the administration of new biological drugs, thus these patients are potentially at risk for MRONJ.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws – 2014 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72(10):1938–56. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleisher KE, Jolly A, Venkata UD, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw onset times are based on the route of bisphosphonate therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:513–19. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marx RE, Cillo JE, Jr, Ulloa JJ. Oral bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis: risk factors, prediction of risk using serum CTX testing, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:2397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kos M, Kuebler JF, Luczak K, Engelke W. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: A review of 34 cases and evaluation of risk. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2010;38:255–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jadu F, Lee L, Pharoah M, Reece D, Wang L. A retrospective study assessing the incidence, risk factors and comorbidities of pamidronate-related necrosis of the jaws in multiple myeloma patients. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:2015–19. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramírez L, López-Pintor RM, Casañas E, et al. New non-bisphosphonate drugs that produce osteonecrosis of the jaws. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2015;13(5):385–93. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a34055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos-Silva AR, Belizário Rosa GA, et al. Osteonecrosis of the mandible associated with bevacizumab therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115(6):e32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pichardo SE, van Merkesteyn JP. Evaluation of a surgical treatment of denosumab-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(3):272–78. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preidl RHM, Ebker T, Raithel M, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in a Crohn’s disease patient following a course of Bisphosphonate and Adalimumab therapy: A case report. BMC Gastroenterology. 2014;14:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassoni A, Romeo U, Terenzi V, et al. Adalimumab: Another medication related to osteonecrosis of the jaws? Case Rep Dent. 2016;2016:2856926. doi: 10.1155/2016/2856926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleissig Y, Regev E, Lehman H. Sunitinib related osteonecrosis of jaw: A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113(3):e1–e3. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lescaille G, Coudert AE, Baaroun V, et al. Clinical study evaluating the effect of bevacizumab on the severity of zoledronic acid-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients. Bone. 2014;58:103–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheinfeld N. A comprehensive review and evaluation of the side effects of the tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15(5):280–94. doi: 10.1080/09546630410017275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sivolella S, Lumachi F, Stellini E, Favero L. Denosumab and anti-angiogenetic drug-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: An uncommon but potentially severe disease. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(5):1793–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pakosch D, Papadimas D, Munding J, et al. Osteonecrosis of the mandible due to anti-angiogenic agent, bevacizumab. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;17:303–6. doi: 10.1007/s10006-012-0379-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allegra A, Oteri G, Alonci A, et al. Association of osteonecrosis of the jaws and POEMS syndrome in a patient assuming rituximab. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2014;42:279–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebker T, Rech J, von Wilmowsky C, et al. Fulminant course of osteonecrosis of the jaw in a rheumatoid arthritis patient following oral bisphosphonate intake and biologic therapy. Rheumatology. 2013;52(1):218–20. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB. Antitumor necrosis factor therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: A review of agents, pharmacology, clinical results, and safety. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1999;5:119–33. doi: 10.1097/00054725-199905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciantar M, Adlam DM. Treatment with infliximab: Implications in oral surgery? A case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45(6):507–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G, Sandborn WJ, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains mucosal healing in patients with Crohn’s disease: Data from the EXTEND trial. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1102–11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel S, Choyee S, Uyanne J, et al. Non-exposed bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A critical assessment of current definition, staging, and treatment guidelines. Oral Diseases. 2012;18:625–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2012.01911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niibe K, Ouchi T, Iwasaki R, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with dental prostheses being treated with bisphosphonates or denosumab. J Prosthodont Res. 2015;59:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Favia G, Tempesta A, Limongelli L, et al. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: Considerations on a new antiresorptive therapy (Denosumab) and treatment outcome after a 13-year experience. Int J Dent. 2016;2016:1801676. doi: 10.1155/2016/1801676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan AA, Morrison A, Hanley DA, et al. Diagnosis and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw: A systematic review and international consensus. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(1):3–23. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosella D, Papi P, Giardino R, et al. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Clinical and practical guidelines. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6(2):97–104. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.178742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]