Abstract

Background:

Health Links are a new model of providing care coordination for high-cost, high-needs patients in Ontario. We evaluated use of hospital-related health care services among Health Links patients in the Central Local Health Integration Network (LHIN) of Ontario in the year before versus after program enrolment and compared rates of use with those among similar patients with complex needs not enrolled in the program (comparator group).

Methods:

We identified all patients who received a Health Links coordinated care plan before Jan. 1, 2015, using linked registry and health administrative data. We used propensity scores to match (1:1) enrollees (registry) with comparator patients (administrative data). Using a difference-in-differences approach with generalized estimating equations, we evaluated 5 measures of Health Link performance: rates of hospital admission, emergency department visits, days in acute care, 30-day readmissions and 7-day postdischarge primary care follow-up.

Results:

Of the 344 enrollees in the registry, we matched 313 [91.0%] to comparator patients. All measured sociodemographic, comorbidity and health care use characteristics were balanced between the 2 groups (all standardized differences < 0.10). For enrollees, the rate of days in acute care per person-year increased by 35% (incidence rate ratio 1.35 [confidence interval 1.11-1.65]) after versus before the index date, but differences were nonsignificant for all other measures. Difference-in-differences analyses revealed greater reductions in hospital admissions, emergency department visits and acute care days after the index date in the comparator group than among enrollees.

Interpretation:

Initial implementation of the Health Link program in the Central LHIN did not reduce selected indicators of Health Link performance among enrollees. As the Health Link program evolves and standardization is implemented, future research may reveal effects from the initiative in other outcomes or with longer follow-up.

Multiple studies have shown that use of health care resources is highly concentrated among a small number of patients.1-6 Data from Canada suggest that high-cost users (the top 5% of the population) account for two-thirds of annual health care spending,1 including 29% of payments for physician services2 and 61% of hospital and home care costs.3 Similar findings have been reported in the United States.4-6 With limited health care resources available, transforming the delivery of health care services to better meet the needs of patients with the most complex needs is required for sustainability of the health care system.

In response, Ontario's Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care launched Health Links, an ambitious strategy aimed to better provide coordinated, community-based health care for patients with complex health and social needs.7 The program started with 26 early-adopter Health Links in December 2012, and 82 sites were in operation throughout the province by the end of 2015.8 Each Health Link is voluntary and operates under a low-rules approach,9,10 having the flexibility to determine how coordinated care will be delivered within the regional context. Patients are typically referred into Health Links during a presentation to the health care system, based on (any of) being at high risk for inpatient admission or readmission, having multiple inpatient and/or emergency visits in the previous year, or having multiple coexisting chronic conditions11 or socioeconomic challenges (such as low income or lack of social support). Once enrolled, patients are provided with intensive care coordination, including multidisciplinary care, and a patient-centred coordinated care plan is completed that outlines the patient's needs, goals, providers, treatments and appointments. These processes aim to engage patients and their care providers to ensure that the plan is being followed, that patients are taking the right medications and that patients have a care provider who knows them whom they can call,7 all with the aims of improving access to care, reducing wait times and preventing unnecessary hospital and emergency visits.12

We carried out a quasi-experimental propensity-matched cohort difference-in-differences analysis of patients enrolled in 3 Health Links from 1 health region to determine 1) whether enrolment in Health Links is associated with differences in use of health care services among enrollees after (v. before) enrolment and 2) how these differences in use patterns among enrolled patients compare to trends among patients with similarly complex needs who were not enrolled.

Methods

Setting

Residents of Ontario have publicly funded universal health insurance that covers the costs of medically necessary care. Patient encounters with the health care system are recorded in health administrative data sets. The administration and coordination of local health care in the province is divided into 14 geographically defined health regions (Local Health Integration Networks [LHINs]). We studied the Central health region (Central LHIN) because it had 3 Health Links operating before 2015 and a single complete patient registry with 1 data custodian (Central Community Care Access Centre), who could provide permission for linkage to health administrative data. The Central LHIN comprises sections of Toronto, Etobicoke, York Region and South Simcoe and is home to 1.8 million residents.

Data sources

We obtained a registry of Health Links candidates from the Central Community Care Access Centre. The registry included information for eligible patients collected from August 2013 through May 2016 and recorded in the Client Health and Related Information System. This Web-based platform is used by front-line care providers to access information about patients and their care plan. Coverage of the number of care plans completed in the registry for the Central LHIN is comparable to that reported elsewhere.13 The registry was transferred to the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and linked deterministically to population-based health administrative data at the individual level with the use of unique, encoded identifiers (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/4/E753/suppl/DC1). We limited our evaluation to Health Link enrolment up to Dec. 31, 2014 to facilitate 1-year pre-post analysis with complete administrative data, thereby assessing the early stages of the Health Links program.

Population

From the registry, we identified all adult patients (enrollees) with a care plan completed (index date) on or before Dec. 31, 2014. This signified the start of Health Link care. We excluded enrollees who had missing demographic information, were enrolled in a Health Link outside the Central LHIN or declined to participate in the Health Links program. For enrollees with multiple entries in the registry, we selected the earliest record. Among eligible enrollees, index dates ranged from May 2013 to December 2014.

To create a comparator population pool (patients who did not receive Health Links care), all Ontarians in the Registered Persons Database were randomly assigned an index date based on the distribution of index dates among eligible enrollees. We included residents in the full comparator pool if they had complete sociodemographic information, were alive at the index date, were eligible for health care coverage, were within the age range of selected enrollees, were affiliated with 1 of the Central LHIN's Health Link catchment areas and were not among patients identified in the registry. We then included only patients with complex needs,11 defined as having an active diagnosis (within 1 year of index) of 4 or more conditions (of a list of 55 conditions defined by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care to define the Health Links target population) (Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/4/E753/suppl/DC1).

Baseline covariates

For eligible enrollees and the full comparator population pool, we identified baseline covariates (at the index date) including age, sex, rurality (using the Rurality Index of Ontario),14 neighbourhood-level income quintile and primary care model affiliation (Family Health Team, Family Health Group, Family Health Organization, other model or no model).15,16 We measured comorbidity using the Collapsed Adjusted Clinical Groups (Johns Hopkins ACG Software, version 10) with 1-year retrospective data. Use of health care services in the year before the index date included the number of oncology, dialysis, primary care and specialist visits, home care services and mental health inpatient episodes. We identified the number of emergency department and acute care admissions within each quarter before the index date (i.e., 1-3, 4-6, 7-9 and 10-12 mo before).

Propensity-matched cohort

We established a propensity score for the probability of enrolment into Health Links for the study population (enrollees and comparator population pool). The final logistic regression model included all identified baseline covariates. We transformed continuous variables related to use of health care services using a square-root term and included 2-way interactions between all variables pertaining to use of health care services.

We created a propensity-matched cohort by using the nearest-neighbour greedy algorithm to match enrollees with comparator patients (1:1, without replacement). We matched enrollees and comparator patients on the logit of their propensity score (within 0.10 standard deviations) and index date (within 90 d). We assessed covariate balance between selected enrollees and comparator patients using standardized differences (SDiffs). An SDiff of 0.10 or greater indicates imbalance.17 To assess potential selection biases, we assessed SDiffs between matched enrollees and comparator patients in several additional baseline measures not included in the propensity model, including receipt of palliative care (outpatient or inpatient setting) before the index date and the number of oncology, dialysis, primary care and specialist visits, home care services and mental health inpatient episodes within each quarter before the index date. We also compared mortality in the 1-year period after the index date and assessed selection bias by comparing SDiffs in baseline covariates between enrollees matched versus not matched for study inclusion.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures included rates of acute hospital admissions, emergency department visits, days in acute care, 30-day hospital readmissions and primary care follow-up within 7 days of discharge. Full definitions are provided in Appendix 3 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/4/E753/suppl/DC1). We selected these measures a priori to reflect key performance markers for Health Links that are measurable with available administrative data.8,18 Each indicator was measured 1 year before the index date and 1 year after the index date (or to death).

Statistical analysis

We performed comparative effectiveness evaluation on each measure using the difference-in-differences approach with generalized estimating equations and robust error variances on individual-level data. We modelled acute hospital admissions, emergency department visits and days in acute care with a negative binomial distribution and log link, including a log of person-years offset term to account for differences in the follow-up period due to deaths. For the readmissions and primary care follow-up measures, we modelled the number of events (readmitted or received follow-up) specifying a Poisson distribution with the total number of hospital admissions (per person, before and after the index date) as an offset term in the model. Each regression model included binary variables for enrolment status (enrollee or comparator patient), time period (before or after the index date) and a 2-way interaction term between these variables, the difference-in-differences estimator. As such, we obtained pre-post differences among enrollees (objective 1) and difference-in-differences (objective 2) from the same regression model. All models used an unstructured correlation structure to control for repeated measurements within patients.

Ethics approval

The Research Ethics Board of the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre approved the study.

Results

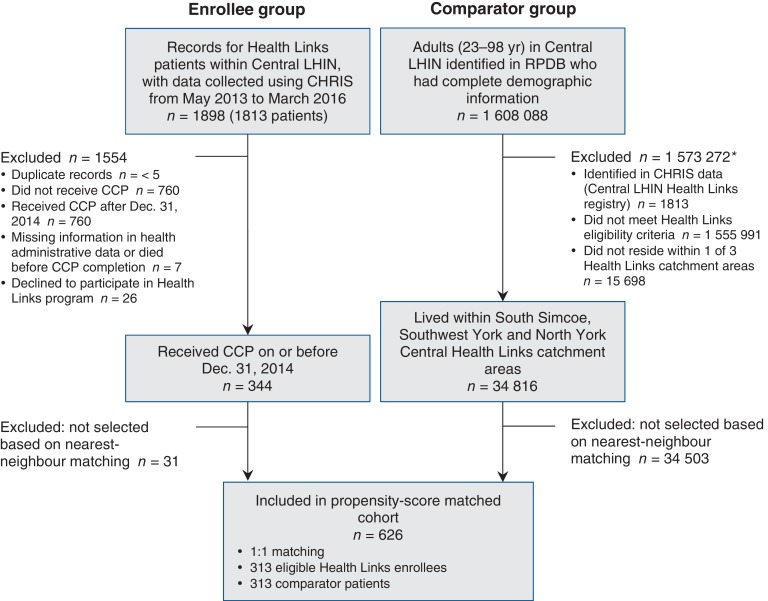

A total of 344 enrollees and 34 816 comparator patients were candidates for propensity matching (Figure 1). From the full comparator pool, a match was found for 313 Health Links enrollees (91.0% of eligible candidates) for analyses. Table 1 shows the SDiffs in baseline characteristics of enrollees and comparator patients, before and after matching. After matching, all covariates included in the propensity model were balanced between groups (SDiffs < 0.10). The mean age of the enrollees was 75.6 (range 23-98) years, 126 (40.3%) were men, and the mean Rurality Index of Ontario score was 6.4, which indicated predominantly urban residence. More than 95% of enrollees (and matched comparator patients) had acute minor, acute major and chronic medical unstable diagnoses. Enrollees were frequent users of the health care system, particularly in the home care sector.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram showing patient selection. *Exclusions not mutually exclusive. Note: CHRIS = Client Health and Related Information System, CCP = coordinated care plan, LHIN = Local Health Integration Network, RPDB = Registered Persons Database.

Table 1: Comparison of characteristics of Health Links enrollees and comparator patients, before and after matching*.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of patients† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before matching | After matching | |||||

| Enrollees n = 344 |

Full comparator pool n = 34 820 |

SDiff | Enrollees n = 313 |

Comparator patients n = 313 |

SDiff | |

| Age at index date, mean ± SD, yr | 75.5 ± 14.3 | 69.9 ± 15.5 | 0.376 | 75.6 ± 13.9 | 75.5 ± 15.0 | 0.010 |

| Male sex | 136 (39.5) | 15 470 (44.4) | 0.099 | 126 (40.3) | 125 (39.9) | 0.007 |

| Area-based income quintile | ||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 66 (19.2) | 4708 (13.5) | 0.154 | 58 (18.5) | 64 (20.4) | 0.048 |

| 2 | 65 (18.9) | 5548 (15.9) | 0.078 | 58 (18.5) | 59 (18.8) | 0.008 |

| 3 | 65 (18.9) | 7526 (21.6) | 0.068 | 61 (19.5) | 65 (20.8) | 0.032 |

| 4 | 82 (23.8) | 9676 (27.8) | 0.090 | 76 (24.3) | 69 (22.0) | 0.053 |

| 5 (highest) | 66 (19.2) | 7362 (21.1) | 0.049 | 60 (19.2) | 56 (17.9) | 0.033 |

| Rurality Index of Ontario score, mean ± SD | 6.7 ± 9.1 | 5.1 ± 6.8 | 0.207 | 6.4 ± 8.9 | 6.8 ± 8.6 | 0.045 |

| Health Link | ||||||

| South Simcoe | 168 (48.8) | 8846 (25.4) | 0.500 | 152 (48.6) | 155 (49.5) | 0.019 |

| Southwest York | 12 (3.5) | 13 895 (39.9) | 0.985 | 12 (3.8) | 16 (5.1) | 0.062 |

| North York Central | 164 (47.7) | 12 079 (34.7) | 0.266 | 149 (47.6) | 142 (45.4) | 0.045 |

| Primary care model affiliation | ||||||

| Family Health Team | 56 (16.3) | 2928 (8.4) | 0.241 | 52 (16.6) | 53 (16.9) | 0.009 |

| Family Health Group | 123 (35.8) | 15 711 (45.1) | 0.192 | 115 (36.7) | 105 (33.5) | 0.067 |

| Family Health Organization | 110 (32.0) | 9006 (25.9) | 0.135 | 97 (31.0) | 105 (33.5) | 0.055 |

| Other | 9 (2.6) | 1302 (3.7) | 0.064 | 7 (2.2) | 9 (2.9) | 0.040 |

| Not rostered in a model | 46 (13.4) | 5873 (16.9) | 0.098 | 42 (13.4) | 41 (13.1) | 0.009 |

| Comorbidity (CADGs 1-12) | ||||||

| Acute minor | 332 (96.5) | 29 315 (84.2) | 0.427 | 301 (96.2) | 304 (97.1) | 0.053 |

| Acute major | 332 (96.5) | 31 134 (89.4) | 0.280 | 301 (96.2) | 304 (97.1) | 0.053 |

| Likely to recur | 286 (83.1) | 25 326 (72.7) | 0.253 | 257 (82.1) | 254 (81.2) | 0.025 |

| Asthma | 52 (15.1) | 4131 (11.9) | 0.095 | 45 (14.4) | 39 (12.5) | 0.056 |

| Chronic medical unstable | 330 (95.9) | 27 667 (79.4) | 0.518 | 299 (95.5) | 302 (96.5) | 0.049 |

| Chronic medical stable | 315 (91.6) | 30 039 (86.3) | 0.169 | 285 (91.0) | 283 (90.4) | 0.022 |

| Chronic specialty stable | 34 (9.9) | 3150 (9.0) | 0.029 | 33 (10.5) | 35 (11.2) | 0.021 |

| Eye/dental | 55 (16.0) | 4569 (13.1) | 0.081 | 53 (16.9) | 51 (16.3) | 0.017 |

| Chronic specialty unstable | 80 (23.2) | 7008 (20.1) | 0.076 | 68 (21.7) | 74 (23.6) | 0.046 |

| Psychosocial | 238 (69.2) | 20 928 (60.1) | 0.191 | 213 (68.0) | 204 (65.2) | 0.061 |

| Preventive/administrative | 221 (64.2) | 10 477 (30.1) | 0.728 | 197 (62.9) | 191 (61.0) | 0.039 |

| Pregnancy | Suppr. | 308 (0.9) | 0.078 | Suppr. | Suppr. | 0.000 |

| Use in prior year, mean ± SD | ||||||

| Dialysis visits | 1.2 ± 12.4 | 1.1 ± 12.6 | 0.008 | 0.9 ± 10.5 | 1.5 ± 14.6 | 0.052 |

| Oncology visits | 0.5 ± 3.5 | 0.6 ± 3.7 | 0.032 | 0.4 ± 3.2 | 0.4 ± 2.8 | 0.018 |

| Primary care visits | 26.4 ± 22.0 | 16.4 ± 14.2 | 0.539 | 24.7 ± 20.5 | 24.7 ± 17.5 | 0.001 |

| Specialist visits | 66.4 ± 47.7 | 25.8 ± 29.2 | 1.026 | 62.9 ± 46.7 | 64.5 ± 52.2 | 0.031 |

| Home care services | 121.5 ± 176.3 | 22.7 ± 79.2 | 0.722 | 114.2 ± 171.6 | 126.4 ± 187.3 | 0.068 |

| Mental hospital admissions | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.122 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.057 |

| Emergency department visits in previous year, mean ± SD | ||||||

| First quarter | 2.4 ± 2.7 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.985 | 2.2 ± 2.3 | 2.3 ± 2.9 | 0.044 |

| Second quarter | 1.5 ± 2.6 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.584 | 1.4 ± 2.1 | 1.3 ± 2.0 | 0.042 |

| Third quarter | 1.2 ± 1.9 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.569 | 1.1 ± 1.7 | 1.1 ± 1.9 | 0.000 |

| Fourth quarter | 1.2 ± 2.2 | 0.3 ± 0.9 | 0.498 | 1.0 ± 1.8 | 1.0 ± 2.2 | 0.011 |

| Hospital admissions in previous year, mean ± SD | ||||||

| First quarter | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 1.316 | 1.1 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 0.024 |

| Second quarter | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.680 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.064 |

| Third quarter | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.571 | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.055 |

| Fourth quarter | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.414 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.090 |

Note: CADGs = Johns Hopkins Collapsed Adjusted Clinical Groups, SD = standard deviation, SDiff = standardized difference, Suppr. = cell suppressed owing to small number (n < 5).

*Only mean values and SDs are reported for continuous variables. Median values were also balanced between groups after matching.

†Except where noted otherwise.

As robustness checks, the matched enrollee and comparator groups were balanced before the index date in palliative care use (enrollees 10.2%, comparator patients 11.5%, SDiff = 0.041) and in nearly all continuous indicators in the year before the index date with the exception of mean mental health admissions 7-9 months before the index date (SDiff = 0.102). After the index date, 1-year mortality was comparable between the 2 groups (enrollees 26.5%, comparator patients 24.9%, SDiff = 0.037). The differences between matched and unmatched (n = 31) enrollees are shown in Appendix 4 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/4/E753/suppl/DC1). Comorbidity and use of health care services in the year before the index date across all sectors were higher among unmatched than matched enrollees (SDiff > 0.10).

Table 2 shows results from the regression models. Among Health Links enrollees, there were no statistically significant reductions in any of the indicators after versus before the index date. For example, the rate of acute hospital admissions per person-year decreased, from 2.26 to 2.07 per person-year, but not to a statistically significant degree (incidence rate ratio [IRR] 0.91 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.79-1.05]). In contrast, days in acute care per person-year increased, from 18.4 to 24.9 (IRR 1.35 [CI 1.11-1.65]).

Table 2: Results from difference-in-differences analysis for selected indicators.

| Measure; group | Rate or mean (95% CI) | Pre-post difference, IRR (95% CI) | Difference-in-differences (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before index date* | After index date | |||

| Hospital admissions† | ||||

| Health Links enrollees | 2.26 (2.06-2.49) | 2.07 (1.81-2.36) | 0.91 (0.79-1.05) | 1.74 (1.40-2.17) |

| Comparator group | 2.06 (1.89-2.26) | 1.08 (0.91-1.29) | 0.53 (0.44-0.63) | |

| Emergency department visits† | ||||

| Health Links enrollees | 3.02 (2.42-3.78) | 3.10 (2.09-4.59) | 1.02 (0.80-1.31) | 1.61 (1.18-2.20) |

| Comparator group | 3.52 (2.97-4.18) | 2.24 (1.72-2.9) | 0.64 (0.52-0.77) | |

| Days in acute care† | ||||

| Health Links enrollees | 18.4 (16.3-20.8) | 24.9 (20.7-30.0) | 1.35 (1.11-1.65) | 1.51 (1.06-2.15) |

| Comparator group | 19.9 (17.3-23.1) | 17.9 (13.5-23.8) | 0.90 (0.66-1.21) | |

| 30-day readmissions, %‡ | ||||

| Health Links enrollees | 30.4 (26.1-35.4) | 36.2 (31.2-41.9) | 1.19 (0.95-1.49) | 1.43 (0.96-2.13) |

| Comparator group | 25.6 (22.2-29.5) | 21.2 (16.2-27.8) | 0.83 (0.61-1.14) | |

| 7-day primary care follow-up, %‡ | ||||

| Health Links enrollees | 36.5 (32.6-41.9) | 37.5 (32.7-43.1) | 1.03 (0.88-1.20) | 1.01 (0.76-1.33) |

| Comparator group | 34.9 (31.0-39.3) | 35.7 (29.0-44.0) | 1.02 (0.82-1.28) | |

Note: CI = confidence interval, IRR = incidence rate ratio.

*All comparisons (enrollees v. comparator patients) were nonsignificant.

†Rate per person-year.

‡Per index hospital admission.

Difference-in-differences estimators were significant for acute hospital admissions (IRR 1.74 [CI 1.40-2.17]), emergency department visits (IRR 1.61 [CI 1.18-2.20]) and days in acute care (IRR 1.51 [CI 1.06-2.15]), indicating greater reductions in these outcomes after the index date for the comparator population relative to the difference for enrollees. No statistically significant difference-in-differences were detected for readmissions or postdischarge primary care follow-up. Visual inspection of longitudinal plots confirmed parallel trends (Appendix 5, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/4/E753/suppl/DC1), which validated the difference-in-differences estimations.

Interpretation

We found that patterns of use of hospital-related care were comparable after (v. before) enrolment for the initial patients enrolled in the Central LHIN's 3 early-adopter Health Links, except for average days in acute care, which increased. Rates of inpatient stays, emergency department visits and acute care days among high-user comparator patients from the same jurisdiction (selected from health administrative data and matched on sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities and use of health care services) after the index date were lower than those for enrollees.

The Health Link program was implemented in late 2012 with the use of a low-rules, bottom-up approach. A possible explanation for the nonsignificant pre-post differences among enrollees that we observed is that the delivery of coordinated care by Health Links may have been poorly defined within local contexts at program onset. Optimal practices in the provision of coordinated care, improving access to primary care services and improving patient engagement have since been recognized and encouraged throughout operating Health Links.8 At onset, the Central LHIN Health Links care providers were referring only their most complex cases for the intervention (Jennifer Bowman, North York General Hospital, North York, Ont.: personal communication, 2016); patients with complex needs whose condition was medically stable were ruled out. This is reflected in the enrollees' patterns of use of health care services in our data and their high 1-year mortality relative to previous reports of Ontario's high-cost patient population.19 Moreover, the observed rates of acute care days among enrollees may have been driven in part by this high mortality, because hospital use increases sharply at the end of life.20 For enrollees, one immediate benchmark is timely postdischarge follow-up, as our data show that less than 40% had a primary care physician visit within 7 days after discharge. In contrast, the differential patterns observed among comparator patients may be due to other, unmeasured factors, such as availability of home support networks, social determinants of health beyond income or unmet health care needs. As such, residual confounding is probable, which would have contributed to the significant difference-in-differences estimation. However, the "regression to the mean" observed in the comparator group is somewhat expected because only one-third of high-cost users remain high-cost in subsequent years.19,21 Similar trends have been observed in studies evaluating interventions among high-use patients with chronic conditions.22,23

Improved care coordination and integration take many forms24 and are targeted toward varying patient populations, which limits comparability across studies. Our findings are consistent with a recent quasi-experimental study from the United Kingdom that showed modest increases in hospital admissions and readmissions among at-risk patients who received multidisciplinary team case management.25 A randomized controlled trial of guided care teams for multimorbid older adults in the United States showed no reductions in hospital or emergency department use during the 20 months after initial care.26 In the province of Quebec, use of health care services was comparable between older frail adults assigned to the Program of Research to Integrate Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy community-based care model relative to comparator patients 1 year after intervention; rates of emergency department visits were lower in the experimental group only after 4 years of follow-up.27 Evaluation of the preliminary stages of the Health Links initiative within other jurisdictions and province-wide are forthcoming. It is important to note that the results presented here are from 1 region of Ontario where each active Health Link was led by an acute care hospital. Provincially, Health Links are led by various organizations including hospitals, Family Health Teams, Community Care Access Centres, Community Health Centres and community support agencies, in single- or co-leadership models,10,28 and have adopted different strategies in terms of governance structure, leadership and approach to integration.29 The method that Health Links use to identify their target population varies and has evolved over time to a more standardized approach following further guidance from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.8 The effectiveness of varying models of Health Links has yet to be explored and will require a provincial patient registry and further data collection from Health Link organizations.

Limitations

Several important limitations of this work are notable. Our analysis was limited to hospital-related outcomes identified with available administrative data. Other measures specific to coordinated care, such as patient experience and system access, are important but could not be measured. Likewise, we were unable to quantify changes in total health care costs before versus after the index date owing to data availability. Our analysis was limited to 313 enrollees receiving care within 1 (of 14) LHIN with 3 Health Links in operation. This limits generalizability of our findings, particularly given the flexible nature of the intervention across provincial jurisdictions. Selection bias cannot be ruled out, as 31 Health Links enrollees (9.0%) who had higher use of health care services before enrolment and greater chronic morbidity went unmatched. Our models therefore underestimate the enrollee means in measured outcomes before the index date and potentially also underestimate the full effect of Health Links on the highest-risk group of patients (i.e., more modest reductions may not be detected). Last, residual confounding in the selection of matched comparator patients is possible, despite several robustness checks.

Conclusion

Patterns of use of hospital-related care did not decrease among the first enrollees to Health Links in Ontario's Central LHIN. However, this analysis was restricted to enrolment before January 2015, and, as the Health Links program has evolved, it is possible that improvements to health outcomes may become evident. Additional research is therefore needed to confirm these findings in other Ontario jurisdictions with additional follow-up data as well as to quantify additional measures of patient experience.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/5/4/E753/suppl/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Funding: Walter Wodchis was supported by the Health System Performance Research Network from grant 06034 awarded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Disclaimer: This research was supported by grants from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) and the Ontario SPOR Support Unit to the Health System Performance Research Network and by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is also funded by an annual grant from the MOHLTC. The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by the ICES or the MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. Parts of this material are also based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the CIHI. No benefits have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

- 1.Wodchis WP. The concentration of health care spending: little ado (yet) about much (money). Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research conference. Montréal. 2012. May 30. [accessed 2017 July 4]. Available www.longwoods.com/blog/the-concentration-of-health-care-spending-little-ado-yet-about-much-money/

- 2.Reid R, Evans R, Barer M, et al. Conspicuous consumption: characterizing high users of physician services in one Canadian province. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8:215–24. doi: 10.1258/135581903322403281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rais S, Nazerian A, Ardal S, et al. High-cost users of Ontario's healthcare services. Healthc Policy. 2013;9:44–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen S. The concentration of health care expenditures and related expenses for costly medical conditions, 2009. Statistical brief no. 359. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2012. pp. 1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joynt KE, Gawande AA, Orav EJ, et al. Contribution of preventable acute care spending to total spending for high-cost Medicare patients. JAMA. 2013;309:2572–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Udow-Phillips M, Kofke-Egger H, Ehrlich E. Health care cost drivers: chronic disease, comorbidity, and health risk factors in the U.S. and Michigan. Ann Arbor (MI): Center for Healthcare Research & Transformation. 2010. [accessed 2017 July 4]. Available www.chrt.org/publication/health-care-cost-drivers-chronic-disease-comorbidity-health-risk-factors-u-s-michigan/

- 7.Transforming Ontario's health care system: community Health Links provide coordinated, efficient and effective care to patients with complex needs. Toronto: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. [accessed 2017 July 4]. Available www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/transformation/community.aspx.

- 8.Guide to the advanced Health Links model. Toronto: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. [accessed 2017 July 4]. Available www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/transformation/docs/Guide-to-the-Advanced-Health-Links-Model.pdf.

- 9.Evans JM, Grudniewicz A, Wodchis WP, et al. Leading the implementation of Health Links in Ontario. Healthc Pap. 2014;14:21–5. 58–60. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2015.24104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angus H, Greenberg A. Can better care for complex patients transform the health system? Healthc Pap. 2014;14:9–19. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2015.24103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robertson M, Bains N, Hillmer M, et al. Health Links: meeting the needs of Ontario's high needs users [lecture]. Canadian Institute for Health Information webinar. 2016. Jan. 27. [accessed 2017 July 4]. Available www.cihiconferences.ca/highusers/downloads/Michael_Robertson_EN.pdf.

- 12.Improving care for high-needs patients [news release]. Toronto: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. 2012 Dec. 6. [accessed 2017 July 4]. Available https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2012/12/improving-care-for-high-needs-patients.html.

- 13.Health Links: excerpts from the Q3 report. Toronto: Health Quality Ontario. 2016. [accessed 2017 July 4]. Available www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/qi/health-links/health-links-q3-2015-report-en.pptx.

- 14.Kralj B.Measuring rurality - RIO2008_BASIC: methodology and results. Toronto: Economics Department, Ontario Medical Association 2009. Availablehttps://www.oma.org/wp-content/uploads/2008rio-fulltechnicalpaper.pdfaccessed 2017 July 4

- 15.Glazier RH, Kopp A, Schultz SE, et al. All the right intentions but few of the desired results: lessons on access to primary care from Ontario's patient enrolment models. Healthc Q. 2012;15:17–21. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2013.23041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glazier RH, Zagorski BM, Rayner J. Comparison of primary care models in Ontario by demographics, case mix and emergency department use, 2008/09 to 2009/10: ICES investigative report. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. 2012. [accessed 2017 July 4]. Available www.ices.on.ca/~/media/Files/Atlases-Reports/2012/Comparison-of-primary-care-models-in-Ontario/Full%20report.ashx.

- 17.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kromm S, Mondor L, Wodchis WP. Assessing value in Ontario Health Links. Part 3: measures of system performance in Ontario's Health Links. vol. 4.3 of Applied health research question series. Toronto: Health System Performance Research Network. 2015. [accessed 2017 Aug. 22]. Available http://hsprn.ca/uploads/files/HSPRN%20AHRQ%20Health%20Links%20Part%203%20Measures.pdf.

- 19.Wodchis WP, Austin PC, Henry DA. A 3-year study of high-cost users of health care. CMAJ. 2016;188:182–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menec V, Lix L, Steinbach C, et al. Patterns of health care use and cost at the end of life. Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. 2004. [accessed 2017 July 4]. Available https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/055c/674bba6e0253a611d7bee8bbf9acd26987f5.pdf.

- 21.Ronksley PE, McKay JA, Kobewka DM, et al. Patterns of health care use in a high-cost inpatient population in Ottawa, Ontario: a retrospective observational study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3:E111–8. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20140049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Billot L, Corcoran K, McDonald A, et al. Impact evaluation of a system-wide chronic disease management program on health service utilisation: a propensity-matched cohort study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steventon A, Bardsley M, Billings J, et al. An evaluation of the impact of community-based interventions on hospital use. London (UK): Nuffieldtrust. 2011. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armitage GD, Suter E, Oelke ND, et al. Health systems integration: state of the evidence. Int J Integr Care. 2009;9:e82. doi: 10.5334/ijic.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stokes J, Kristensen SR, Checkland K, et al. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary team case management: difference-in-differences analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010468. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boult C, Reider L, Leff B, et al. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:460–6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hébert R, Raîche M, Dubois MF, et al. Impact of PRISMA, a coordination-type integrated service delivery system for frail older people in Quebec (Canada): a quasi-experimental study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B:107–18. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mondor L, Song K, Wodchis WP. Assessing value in Ontario Health Links. Part 5: health system performance trends in Health Links populations: 2012-2014. Toronto: Health System Performance Research Network. 2016. [accessed 2017 Aug. 22]. Available www.hsprn.ca/uploads/files/HealthLinksPart5_HealthSystemPerformanceTrends.pdf.

- 29.Mery G, Wodchis WP. Assessing value in Ontario Health Links. Part 2: a perspective from early adopter Health Links. Vol. 4.2 of Applied health research question series. Toronto: Health System Performance Research Network. 2015. [accessed 2017 Aug. 22]. Available http://hsprn.ca/uploads/files/HSPRN%20AHRQ%20Health%20Links%20Part%202%20Value%20in%20HL.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.