Abstract

Background

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) has been increasingly recognized as a significant public health concern. Identifying early and modifiable risk factors is necessary for advancing screening and intervention efforts, particularly early detection of at-risk individuals. As a step toward addressing this need, we aimed to examine childhood maltreatment, including its specific subtypes, in relation to NSSI.

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of childhood maltreatment (overall, sexual abuse, physical abuse and neglect, and emotional abuse and neglect) in association with NSSI. We also provided a qualitative review of mediators and moderators of this association. Relevant articles published from inception to September 25, 2017, were identified through a systematic search of Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO.

Outcomes

We identified 71 publications meeting eligibility criteria. Overall childhood maltreatment was associated with NSSI (odds ratio [OR] 3·42, 95% CI 2·74–4·26), and effect sizes for maltreatment subtypes ranged from OR 1·84 (95% CI 1·45–2·34) for childhood emotional neglect to OR 3·03 (95% CI 2·56–3·54) for childhood emotional abuse. Except in the case of childhood emotional neglect, there was no evidence of publication bias. Across multiple maltreatment subtypes, stronger associations with NSSI were found in non-clinical samples.

Interpretation

With the exception of childhood emotional neglect, childhood maltreatment and its subtypes are associated with NSSI. Screening of childhood maltreatment history in NSSI risk assessments may hold particular value in community settings, and increased attention to childhood emotional abuse is warranted.

Keywords: child abuse, child neglect, meta-analysis, non-suicidal self-injury, self-harm

Introduction

The clinical importance of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), defined as direct and deliberate destruction of one's own bodily tissue in the absence of suicidal intent,1 has been increasing acknowledged in recent years. Based on recent estimates, the lifetime prevalence of this behavior ranges from 5.5% in adults to 17.2% in adolescents.2 Although most individuals who engage in repeated NSSI cease this behavior within a few years, it often follows a more chronic course, persisting for more than five years in approximately 20% of these individuals.3 NSSI is a stronger predictor of suicide attempts than is a past history of suicidal behavior.4–6 Clarifying potential factors underlying the etiology of this phenomenon is important insofar as it may inform the development of future prevention and intervention strategies, a pressing need given the paucity of empirically supported treatments for this behavior.7,8

Within this context, childhood maltreatment has received considerable empirical attention, particularly in the case of childhood sexual abuse9,10 (for maltreatment subtype definitions, see11). Moreover, childhood sexual abuse, and to a lesser degree childhood physical abuse and neglect, feature prominently in several theoretical conceptualizations of NSSI.9,12 Underlying the greater empirical and theoretical interest in these forms of childhood maltreatment is the tacit assumption that they have a more central role, relative to other maltreatment subtypes, in the etiology of NSSI. In the absence of empirical evaluation, however, such a possibility cannot be assumed. Furthermore, with the exception of an influential early meta-analysis of sexual abuse and NSSI,12 the association between childhood maltreatment and NSSI has yet to be systematically and quantitatively reviewed.

The current review was intended to address several goals. First, it aimed to provide a systematic meta-analysis of childhood maltreatment and its subtypes in relation to NSSI. Second, it evaluated the strength of associations between maltreatment subtypes and NSSI after accounting for the presence of all available covariates. Third, it quantified the association between each form of childhood maltreatment and NSSI severity among individuals who engage in this behavior. Finally, a qualitative review was provided of studies on mediators and moderators of this association. Through addressing these objectives, and through including a comprehensive evaluation of all forms of childhood maltreatment, the current review builds upon the earlier meta-analysis of childhood sexual abuse and NSSI.12

Method

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

A systematic search of the literature was conducted in Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO to identify studies relevant to the current review. The following search string was applied: (self-injur* OR parasuicid* OR "self-harm" OR "self-mutilation") AND ("emotional abuse" OR "emotionally abused" OR "emotional victimization" OR "emotionally victimized" OR "verbal abuse" OR "verbally abused" OR "psychological abuse" OR "psychologically abused" OR "physical abuse" OR "physically abused" OR "sexual abuse" OR "sexually abused" OR "sex abuse" OR maltreat* OR "childhood neglect" OR "child neglect" OR "childhood abuse" OR "child abuse"). The search results were limited to: (i) English-language publications and (ii) peer-reviewed journals. This was supplemented by a search of the references of the prior meta-analysis of childhood sexual abuse and NSSI.12 This search strategy yielded a total of 1,492 articles, of which 938 were unique reports. In cases where the eligibility could not be ruled out based on the title and abstract, the full text was also examined. Each search result was reviewed by two independent raters for eligibility, with discrepancies resolved by the first author.

The study inclusion criteria were: (i) any form of childhood maltreatment was assessed, distinct from other constructs (e.g., other adverse childhood experiences); (ii) assessments of childhood maltreatment observed its distinction from abuse experienced in adulthood (i.e., before versus starting at age 18); (iii) NSSI was assessed separately from other constructs (i.e., suicidality and other risky behaviors); (iv) childhood maltreatment and NSSI were assessed systematically; (v) quantitative data were presented on the association between childhood maltreatment and NSSI; and (vi) studies that only assessed childhood maltreatment subtypes in relation to NSSI distinguished between maltreatment subtypes.

Data extraction

Several studies presented data for NSSI and/or childhood maltreatment as both continuous and categorical variables. In these cases, the continuous data were selected for use in our analyses. This decision was guided by statistical concerns regarding dichotomous relative to continuous variables.13–16 Of note, in cases where both continuous and categorical data were available in a given study, the effects produced by categorical data tended to be larger, indicating that our preference for continuous data produced more conservative estimates of the association between childhood maltreatment and NSSI.

To assess potential moderators in meta-analyses, data on 10 study characteristics were extracted. These included four sample characteristics: (i) sample age group (adolescent, defined as under age 18, or adult); (ii) mean age of sample; (iii) sample type (community, clinical/at-risk, or mixed); and (iv) percentage of female participants in the sample. Data for six study design characteristics were extracted: (i) form(s) of childhood maltreatment assessed; (ii) method of measuring maltreatment (interview versus self-report); (iii) method of measuring NSSI (interview versus self-report); (iv) time-frame of maltreatment measure; (v) time-frame of NSSI measure; and (vi) cross-sectional versus longitudinal analysis.

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3·3·070.17 For all analyses, random-effects models were generated, accounting for the high expected heterogeneity across studies resulting from differences in samples, measures, and design. Heterogeneity across the studies was evaluated using the I2 statistic, which indicates the percentage of the variance in an effect estimate that is a product of heterogeneity across studies rather than sampling error (i.e., chance). Low heterogeneity is indicated by I2 values of around 25%, and moderate heterogeneity by I2 values of 50%. Substantial heterogeneity across studies is indicated by an I2 value of 75%.18 Whenever possible, participants with a suicide attempt history were excluded, within individual studies, from analyses so as to assess cleanly the unique association between NSSI and childhood maltreatment (e.g., in studies presenting maltreatment data separately for participants with no self-harm, NSSI only, and both NSSI and suicide attempt history, only data for the former two groups were included).

High heterogeneity indicates the need for moderator analyses to account for potential sources of this heterogeneity. Each potential moderator was first assessed separately, with an estimate of the effect size at each level of the moderator calculated. When multiple moderators were significant, a multivariate meta-regression with a random-effects model and unrestricted maximum likelihood was conducted simultaneously evaluating all significant moderators in univariate analyses.

To evaluate for publication bias inflating estimates of pooled effect size, the following indices were calculated: Orwin’s fail-safe N,19 Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill analysis,20 and Egger’s regression intercept.21 Orwin’s fail-safe N is an index of the robustness of an overall effect size, calculating the number of studies with an effect size of 0 required to reduce the overall effect size in a meta-analysis to non-significance. Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill analysis yields an estimate of the number of missing studies based on asymmetry in a funnel plot of the standard error of each study in a meta-analysis against its effect size, and an effect size estimate and confidence interval, adjusting for these missing studies. It assumes homogeneity of effect sizes. Consequently, its results need to be interpreted with caution when significant heterogeneity is present. Egger’s regression intercept estimates potential publication bias using a linear regression approach assessing study effect sizes relative to their standard error.

Role of the funding source

The funding source had no role in the design or conduct of this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

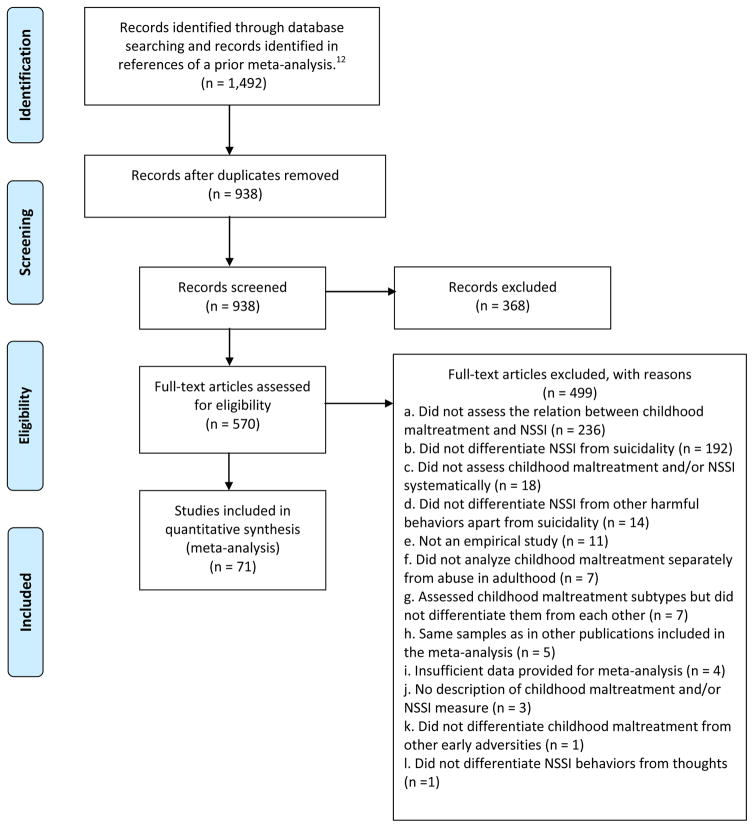

Of the 938 unique records identified, 368 reports were excluded based on their titles and abstracts. Following this initial screen, an additional 499 articles were excluded based on a detailed full-text review, leaving a set of 71 publications4,22–91 satisfying the eligibility criteria (Figure 1 and Table 1). Fifteen studies featured overlapping samples. Whenever it remained unclear after inspection of the full text whether two studies reported on overlapping samples, the study authors were contacted to seek clarity on this issue. In cases where two or more studies used overlapping samples but reported on different forms of maltreatment, both studies were retained for relevant analyses. In cases where multiple studies assessed the same maltreatment subtype in relation to NSSI in overlapping samples, preference was given to studies, in descending order, based on: (i) shortest time-frame used for the NSSI measure, (ii) largest sample size for relevant analyses, (iii) more common measure of maltreatment used in relevant analyses, and (iv) largest number of covariates in relevant multivariate analyses. Three studies28,34,41 did not report data required for meta-analysis, but was retained after the necessary data were obtained from the study authors. With all but one study74 assessing lifetime childhood maltreatment, time-frame of maltreatment measure was excluded from all moderator analyses. For only sexual abuse was there a sufficient number of studies (i.e. k≥ 3) for a meta-analysis of prospective NSSI. Given the considerable heterogeneity among the three relevant studies of sexual abuse55,67,87 in follow-up assessment of NSSI (i.e., two months to 10 years), a meta-analysis of this longitudinal association was not conducted.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of literature search

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Study Author(s) (year) | Na | % Femalea | Mean Agea | Sample | Childhood Maltreatment

|

Non-Suicidal Self-Injury

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure(s) | Format | Form(s) | Measure | Format | Time Frame | |||||

| Akyuz et al. (2005) | 628 | 100 | 34.8 | Community | CANQ | Q | CEA, CPA, CSA | SSM | Q | Lifetime |

| Arens et al. (2012) | 407 | 65.0 | 20.3 | Community | CATS | Q | Overall | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Arens et al. (2014) | 600 | 73.0 | 19.7 | Community | CATS | Q | Overall, CPA, CPN, CSA | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Asarnow et al. (2011) | 250 | 65.2 | 15.8 | Clinical | K-SADS | I | CPN, CSA | K-SADS | I | Lifetime |

| Auerbach et al. (2014) | 194 | 74.2 | 15.5 | Clinical | CTQ | Q | Overall, CPA, CSA | SITBI | I | 1 month |

| Baiden et al. (2017) | 2,038 | 38.9 | 12.5 | Clinical | ChYMH | I | CEA, CPA, CSA | ChYMH | I | Lifetime |

| Bernegger et al. (2015)b | 255 | 56.9 | – | Clinical | CTQ | Q | Overall, CEA, CEN, CPA, CPN, CSA | VI-SURIAS | Q | Lifetime |

| Bresin et al. (2013) | 446 | 30.4 | 30.3 | At-risk | CTQ | Q | CEA, CEN, CPA, CPN, CSA | LHA | I | Lifetime |

| Briere & Gil (1998) Study 1 | 927 | 50.0 | 46.0 | Community | TES | Q | CSA | TSI | Q | 6 months |

| Briere & Gil (1998) Study 2 | 390 | 77.9 | 36.0 | Clinical | CMIS | I | CSA | TSI | Q | 6 months |

| Brown et al. (1999) | 117 | 98.3 | 24.7 | Clinical | SLEI | Q | CPA, CSA | SSM | Q | Lifetime |

| Buckholdt et al. (2009) | 117 | 76.3 | 21.0 | Community | EAC | Q | CEN | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Burke et al. (2017) | 520 | 76.0 | 20.6 | At-risk | CTQ | Q | CEA, CEN, CPA, CPN, CSA | FAFSI | Q | Lifetime |

| Buser & Hackney (2012) | 390 | 66.0 | 20.3 | Community | EASE-PI | Q | CEA | FASM | Q | 1 year |

| Buser et al. (2015) | 648 | 74.0 | 20.5 | Community | EASE-PI | Q | CEA | FASM | Q | 1 year |

| Cater et al. (2014)b | 2,500 | 52.6 | 22.2 | Community | JVQ | Q | CEA, CPA, CPN, CSA | SSM | Q | Lifetime |

| Cerutti et al. (2011) | 234 | 50.4 | 16.5 | Community | LSC-R | Q | CEA, CPA, CPN, CSA | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Chapman et al. (2014) | 104 | 100 | 31.9 | At-risk | CTQ | Q | CEN, CPN, CSA | LPC-2 | I | Lifetime |

| Claes & Vandereycken (2007) | 65 | 100 | 21.7 | Clinical | TEQ | Q | CPA, CSA | SIQ | Q | 1 year |

| Croyle & Waltz (2007) | 216 | 55.0 | 20.1 | Community | TES | Q | CEA, CSA | SHIF | Q | 3 years |

| Darke & Torok (2013) | 300 | 33.0 | 37.1 | Clinical | CTA | I | CPA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Di Pierro et al. (2012) | 267 | 70.4 | 17.0 | Community | BCI | I | CPA, CPN, CSA | SIQ | Q | Lifetime |

| Evren & Evren (2005) | 136 | 0.0 | 36.4 | Clinical | CANQ | Q | CEA, CPA, CSA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Evren et al. (2006) | 112 | 0.0 | 33.8 | Clinical | CANQ | Q | CEA, CPA, CSA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Evren et al. (2008) | 176 | 0.0 | 43.1 | Clinical | SSM | Q | Overall | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Evren et al. (2012) | 200 | 0.0 | – | Clinical | CTQ | Q | CEA, CEN, CPA, CPN, CSA | SMBQ | I | Lifetime |

| Gladstone et al. (2004) | 125 | 100 | 36.9 | Clinical | SSM | I | CSA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Glassman et al. (2007)1 | 86 | 77.9 | 17.0 | Mixed | CTQ | Q | CEA, CEN, CPA, CPN | SITBI | I | 1 year |

| Gorodetsky et al. (2016) | 614 | 0.0 | 40.3 | At-risk | CTQ | Q | Overall | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Gratz (2006) | 200 | 100 | 23.3 | Community | API, PBI | Q | Overall, CEN, CPA, CSA | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Gratz and Chapman (2007) | 97 | 0.0 | 22.7 | Community | API, PBI | Q | CEN, CPA | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Gratz et al. (2002)b | 133 | 66.9 | 22.7 | Community | API, DAS, PBI | Q | CEN, CPA, CPN, CSA | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Isohookana et al. (2013)b | 508 | 59.1 | 15.4 | Clinical | K-SADS | I | CPA, CSA | K-SADS | I | Lifetime |

| Jaquier et al. (2013) | 212 | 100 | 36.6 | At-risk | CTQ | Q | CEA, CPA, CSA | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Kaess et al. (2013) | 125 | 50.4 | 17.1 | Clinical | CECA.Q | Q | Overall, CEN, CPA, CPN, CSA | FASM | Q | 1 year |

| Kaplan et al. (2016) | 48 | 100 | 17.2 | Clinical | CTQ | Q | CSA | SITBI | I | 1 and 12 months |

| Kara et al. (2015) | 295 | 24.4 | 14.3 | At-risk | SSM | I | CSA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Karagöz & Da (2015) | 79 | 0.0 | 41.9 | Clinical | CTQ | Q | CPA, CSA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Lipschitz et al. (1999) | 71 | 52.2 | 14.7 | Clinical | CTQ | Q | CPN | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Lüdtke et al. (2016) | 72 | 100 | 16.1 | Clinical | CECA.Q | Q | CEN, CPA, CPN, CSA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Maloney et al. (2010) | 697 | 44.8 | 35.9 | Clinical | CTA | I | Overall, CEA, CEN, CPA, CSA | COGA SSAGA-II |

I | Lifetime |

| Martin et al. (2011) | 1,170 | 74.0 | 19.3 | Community | PBI, PRP, SSM | Q | CEN, CSA | OSI | Q | 6 months |

| Martin et al. (2016) | 957 | 78.1 | 20.1 | Community | CCMS | Q | Overall | OSI | Q | Lifetime |

| Muehlenkamp et al. (2010) | 1,855 | 66.0 | 19.7 | Community | AMQ | Q | CPA, CSA | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Nijman et al. (1999) | 47 | 48.0 | 37.5 | Clinical | CTQ | Q | Overall, CEA, CEN, CPA, CPN, CSA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Parker et al. (2005) Study 1 | 112 | 60.7 | 36.4 | Clinical | MOPS, PBI | Q | CPA, CSA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Parker et al. (2005) Study 2 | 98 | 83.7 | 33.7 | Clinical | MOPS, PBI | Q | CPA, CSA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Parker et al. (2005) Study 3 | 76 | 80.6 | 33.4 | Clinical | MOPS, PBI | Q | Overall, CPA, CSA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Peh et al. (2017) | 108 | 59.3 | 17.0 | Clinical | CTQ | Q | Overall | FASM | Q | 1 year |

| Rabinovitch et al. (2015) | 140 | 100 | 15.3 | At-risk | CPS records | – | CPA, CSA | C-SSRS | I | Lifetime |

| Reddy et al. (2013) | 71 | 56.0 | 14.7 | At-risk | CTQ | Q | CSA | FASM | Q | 1 year |

| Reichl et al. (2016) | 52 | 92.3 | 16.3 | Mixed | CECA | I | Overall, CEA, CEN, CPA, CPN, CSA | SITBI | I | Lifetime |

| Roe-Sepowitz (2007) | 256 | 100 | 35.5 | At-risk | CMIS | Q | CEA, CPA, CSA | TSI | Q | Lifetime |

| Stewart et al. (2014) | 2,013 | 45.5 | 17.7 | Clinical | ChYMH | I | CEA, CPA, CSA | ChYMH | I | 1 year |

| Swannell et al. (2012)b | 10,719 | 61.7 | 52.1 | Community | SSM | I | CPA, CPN, CSA, | SSM | I | 1 year |

| Taliaferro et al. (2012)b | 59,276 | 46.6 | – | Community | SSM | Q | CPA, CSA | SSM | Q | 1 year |

| Tatnell et al. (2016)c | 2,550 | 68.0 | 13.9 | Community | ALES | Q | CPA, CSA | SHBQ | Q | Lifetime |

| Thomassin et al. (2016) | 95 | 58.0 | 14.2 | Clinical | CTQ | Q | CEA, CPA, CSA | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Tresno et al. (2012) | 215 | 76 | 19.8 | Community | CATS | Q | CPN | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Tresno et al. (2013) | 313 | 50 | 19.0 | Community | CATS | Q | CPN | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Tsai et al. (2011) | 742 | 23.8 | 17.0 | Community | SSM | Q | CSA | SSM | Q | Lifetime |

| Turell & Armsworth (2000) | 84 | 100 | 32.5 | At-risk | SSM | Q | CEA, CPA, CSA | SSM | Q | Lifetime |

| Tyler et al. (2003) | 417 | 56.3 | 17.4 | At-risk | PC-CTS, SSM | Q | CSA | FASM | Q | Lifetime |

| Wachter et al. (2009) | 58 | 72.4 | 37.1 | Clinical | CTQ | Q | CEA, CEN, CPA, CPN, CSA | DSHI | Q | Lifetime |

| Wan et al. (2015)b | 14,211 | 52.8 | 15.1 | Community | ACE Tool PC-CTS |

Q | Overall, CEA, CPA, CSA | SSM | Q | 1 year |

| Weierich & Nock (2008)1 | 44 | 84.1 | 17.2 | Mixed | CTQ | Q | CSA | SITBI | I | 1 month |

| Weismoore & Esposito-Smythers (2010) | 183 | 71.4 | – | Clinical | K-SADS | I | CPA, CSA | K-SADS | I | 1 year |

| Yates et al. (2008)b | 155 | 51.6 | 26.0 | At-risk | Multiple sources | Mixed | CPA, CPN, CSA | SSM | I | Lifetime |

| Zanarini et al. (2002)2 | 290 | 80.3 | 26.9 | Clinical | CEQ-R | I | CSA | LSDS | I | Lifetime |

| Zanarini et al. (2011)2 | 290 | 80.3 | 26.9 | Clinical | CEQ-R | I | CEN | LSDS | I | 10 years |

| Zetterqvist et al. (2014) | 816 | – | – | Community | LYLES | Q | CEA, CPA, CSA | FASM | Q | 1 year |

| Zlotnick et al. (1996) | 148 | 100 | 33.0 | Clinical | SAQ | Q | CSA | SII | Q | 3 months |

| Zoroglu et al. (2003) | 818 | 61.1 | 15.9 | Community | CANQ | Q | Overall, CEA, CPA, CSA | SSM | Q | Lifetime |

| Zweig-Frank et al. (1994) | 150 | 100 | 29.0 | Clinical | SSMd | I | CSA | DIB-R | I | 2 years |

Note: ACE Tool = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Short Adverse Childhood Experiences Tool; ALES =Adolescent Life Events Scale; AMQ = About Me Questionnaire; API = Abuse and Perpetration Inventory; BCI = Boricua Child Interview; CANQ = Childhood Abuse and Neglect Questionnaire; CATS = Child Abuse and Trauma Scale; CCMS = Comprehensive Childhood Maltreatment Scale; CECA = Childhood Experiences of Care and Abuse Interview; CECA.Q = Childhood Experiences of Care and Abuse Questionnaire; CEQ-R= Revised Childhood Experiences Questionnaire; ChYMH = Child and Your Mental Health Instrument; CMIS = Childhood Maltreatment Interview Schedule; COGA SSAGA-II= Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism II; CPS = child protective services; C-SSRS = Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale; CTA= Christchurch Trauma Assessment; CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; DAS=Disruptions in Attachment Survey; DIB-R= Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines – Revised; DSHI= Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory; EAC=Emotions as a Child Scales; EASE-PI= Exposure To Abusive and Supportive Environments Parenting Inventory; FAFSI= Form and Function of Self Injury Scale; FASM = Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation; JVQ=Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire; K-SADS = Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; LHA= Lifetime History of Aggression; LPC-2= Lifetime Parasuicide Count-2; LSC-R= Life Stressor Checklist-Revised; LSDS= Lifetime Self-Destructiveness Scale; LYLES = Linköping Youth Life Experience Scale; MOPS = Measure of Parental Style; OSI= Ottawa Self-Injury Inventory; PBI= Parental Bonding Instrument; PC-CTS= Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale; PRP= Personal and Relationships Profile; SAQ = Sexual Assault Questionnaire; SHBQ= Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire; SHIF= Self-Harm Information Form; SII = Self-Injury Inventory; SIQ= Self-Injury Questionnaire; SITBI = Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview; SLEI = Sexual Life Events Inventory; SMBQ= Self-mutilative Behavior Questionnaire; SSM = study-specific measure; TEQ= Traumatic Experiences Questionnaire; TES = Traumatic Events Survey; TSI = Trauma Symptom Inventory; VI-SURIAS = Viennese Suicide Risk Assessment Scale

I = Interview; Q = Questionnaire

CEA = childhood emotional abuse; CEN = childhood emotional neglect; CPA = childhood physical abuse; CPN = childhood physical neglect; CSA = childhood sexual abuse

Studies with identical superscripts were drawn from same or overlapping samples but presented unique data included in this review.

The sample size, mean age, and percentage female for participants included in relevant analyses, rather than of the entire study sample, are presented and were incorporated in moderator analyses whenever available. For ease of presentation, whenever the sample size varied across multiple relevant analyses within a study, the largest cumulative sample size across these analyses is presented here, and the sample size used in each analysis was retained in the relevant meta-analysis for purposes of obtaining weighted effect sizes.

Separate effects were reported by sex. The proportion of the overall sample that was female is presented here.

Although childhood abuse was assessed prospectively, its cross-sectional relation with NSSI was reported at each time-point. The analysis of this relation at baseline provided the largest sample size and was thus included in the current review.

The PBI was also used to assess childhood maltreatment. This study did not include it, however, in quantitative analyses.

Univariate associations between overall childhood maltreatment and NSSI

Overall maltreatment was positively associated with NSSI (Table 2). Heterogeneity was high, indicating the appropriateness of moderator analyses (Table 3). Age as a categorical variable significantly moderated the strength of the relation between overall maltreatment and NSSI, with this association stronger among adolescent samples than adult samples. The time-frame of NSSI measurement was also a significant moderator, with studies of past-12-month NSSI yielding larger effects than studies of lifetime NSSI. In a multivariate meta-regression model, neither moderator remained significant.

Table 2.

Univariate associations between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury.

| Effect Size Analyses

|

Heterogeneity Analyses |

Publication Bias Analyses

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | NTotal | Mean Age (Adolescents) |

Mean Age (Adults) |

OR | 95% CI | p | I2 | p | Orwin’s fail-safe N |

Egger’s regression test p |

Trim-and-fill

|

||

| OR | 95% CI | ||||||||||||

| Overall Childhood Maltreatment | 18 | 19,537 | 15.17 | 28.00 | 3·42 | 2·74 – 4·26 | <·0001 | 82·82% | <·0001 | 215 | ·76 | 3·12 | 2·51 – 3·87 |

| Childhood Sexual Abuse | 63 | 48,246 | 15.15 | 39.73 | 2·65 | 2·33 – 3·03 | <·0001 | 68·80% | <·0001 | 583 | ·83 | 2·34 | 2·04 – 2·68 |

| Childhood Physical Abuse | 51 | 37,821 | 15.05 | 39.80 | 2·31 | 1·97 – 2·69 | <·0001 | 78·22% | <·0001 | 397 | ·05 | 2·31 | 1·97 – 2·69 |

| Childhood Physical Neglect | 26 | 17,141 | 16.51 | 42.68 | 2·22 | 1·75 – 2·80 | <·0001 | 73·72% | <·0001 | 192 | ·97 | 2·16 | 1·71 – 2·73 |

| Childhood Emotional Abuse | 29 | 27,768 | 15.16 | 26.52 | 3·03 | 2·59 – 3·54 | <·0001 | 79·18% | <·0001 | 309 | ·37 | 2·77 | 2·38 – 3·23 |

| Childhood Emotional Neglect | 19 | 3,468 | 16.51 | 28.26 | 1·84 | 1·45 – 2·34 | <·0001 | 72·68% | <·0001 | 103 | <·01 | 1·63 | 1·29 – 2·05 |

Note: k = number of unique effects; OR = pooled odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

An outlier was excluded from analyses for childhood physical abuse and sexual abuse, respectively.

Participants < age 18 are classified here as adolescents, and those ≥18 are classified as adults.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate moderator analyses.

| Univariate Moderator Analyses

|

Multivariate | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect Size Analyses

|

Heterogeneity Analyses

|

Meta-Regression Analyses

|

|||||||||

| k | N | b | OR | 95% CI | p | I2 | p | b | p | R2 | |

| Overall Childhood Maltreatment | ·67 | ||||||||||

| Age (Categorical) | 17 | 19,412 | <·01 | ||||||||

| Adolescent | 6 | 4·44 | 4·07–4·84 | <·0001 | 1·71% | ·41 | ·43 | ·13 | |||

| Adultc | 11 | 2·86 | 2·16–3·78 | <·0001 | 67·76% | <·01 | |||||

| Age (Continuous) | 16 | 19,282 | <·01 | ·53 | |||||||

| Percentage Female | 18 | 19,537 | <·01 | ·62 | |||||||

| Sample Type | 17 | 19,485 | ·15 | ||||||||

| Childhood Maltreatment Measurea | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

| NSSI Measure | 18 | 19,537 | ·11 | ||||||||

| NSSI Timeframe | 17 | 19,343 | <·01 | ||||||||

| 12-Month | 4 | 4·50 | 4·12–4·90 | <·0001 | 0% | ·46 | ·15 | ·62 | |||

| Lifetimec | 13 | 3·06 | 2·34–3·99 | <·0001 | 70·10% | <·0001 | |||||

| Childhood Sexual Abuse | |||||||||||

| Age (Categorical) | 62 | 48,121 | ·44 | ||||||||

| Age (Continuous) | 58 | 46,792 | <·01 | ·54 | |||||||

| Percentage Female | 62 | 48,246 | <·01 | ·49 | |||||||

| Sample Type | 61 | 48,150 | ·09 | ||||||||

| Childhood Maltreatment Measure | 61 | 48,091 | ·66 | ||||||||

| NSSI Measure | 63 | 48,246 | ·10 | ||||||||

| NSSI Timeframe | 62 | 48,094 | <·01 | ||||||||

| 12-Month | 15 | 3·52 | 2·84–4·37 | <·0001 | 67·10% | <·01 | |||||

| Lifetime | 47 | 2·38 | 2·05–2·76 | <·0001 | 60·48% | <·0001 | |||||

| Childhood Physical Abuse | |||||||||||

| Age (Categorical) | 50 | 37,696 | ·26 | ||||||||

| Age (Continuous) | 46 | 36,367 | ·02 | ·07 | |||||||

| Percentage Female | 50 | 37,821 | <·01 | ·29 | |||||||

| Sample Type | 49 | 37,683 | <·0001 | ||||||||

| Clinical | 32 | 1·78 | 1·56–2·04 | <·0001 | 34·30% | ·03 | |||||

| Community | 17 | 3·29 | 2·64–4·11 | <·0001 | 78·80% | <·0001 | |||||

| Childhood Maltreatment Measure | 48 | 37,526 | ·52 | ||||||||

| NSSI Measure | 51 | 37,821 | ·13 | ||||||||

| NSSI Timeframe | 50 | 37,627 | ·14 | ||||||||

| Childhood Physical Neglect | ·68 | ||||||||||

| Age (Categorical) | 25 | 17,016 | ·81 | ||||||||

| Age (Continuous) | 23 | 16,686 | ·02 | ·09 | |||||||

| Percentage Female | 26 | 17,141 | <·01 | ·28 | |||||||

| Sample Type | 24 | 17,003 | <·01 | ||||||||

| Clinicalc | 13 | 1·60 | 1·19–2·15 | <·01 | 55·76% | <·01 | |||||

| Community | 11 | 2·87 | 2·22–3·71 | <·0001 | 60·77% | <·01 | ·50 | <·01 | |||

| Childhood Maltreatment Measure | 24 | 16,986 | ·26 | ||||||||

| NSSI Measure | 26 | 17,141 | ·66 | ||||||||

| NSSI Timeframe | 26 | 17,141 | <·01 | ||||||||

| 12-Month | 4 | 3·87 | 2·59–5·77 | <·0001 | 39·45% | ·18 | ·61 | ·02 | |||

| Lifetimec | 22 | 2·01 | 1·58–2·54 | <·0001 | 67·61% | <·0001 | |||||

| Childhood Emotional Abuse | ·77 | ||||||||||

| Age (Categorical) | 29 | 27,768 | ·83 | ||||||||

| Age (Continuous) | 25 | 26,497 | <·01 | ·59 | |||||||

| Percentage Female | 28 | 27,768 | <·01 | ·10 | |||||||

| Sample Type | 27 | 27,630 | ·03 | ||||||||

| Clinicalc | 16 | 2·69 | 2·08–3·47 | <·0001 | 75·28% | <·0001 | |||||

| Community | 11 | 3·66 | 3·31–4·04 | <·0001 | 29·43% | ·17 | <·01 | ·77 | |||

| Childhood Maltreatment Measure | 29 | 27,768 | <·0001 | ||||||||

| Interviewc | 4 | 1·85 | 1·55–2·21 | <·0001 | 19·88% | ·29 | |||||

| Questionnaire | 25 | 3·32 | 2·91–3·79 | <·0001 | 60·67% | <·0001 | ·16 | ·44 | |||

| NSSI Measure | 29 | 27,768 | <·01 | ||||||||

| Interviewc | 10 | 2·19 | 1·64–2·92 | <·0001 | 71·92% | <·01 | |||||

| Questionnaire | 19 | 3·74 | 3·50–3·99 | <·0001 | 0% | ·61 | ·56 | <·01 | |||

| NSSI Timeframe | 29 | 27,768 | ·51 | ||||||||

| Childhood Emotional Neglect | |||||||||||

| Age (Categorical) | 18 | 3,343 | ·24 | ||||||||

| Age (Continuous) | 16 | 3,013 | <·01 | ·09 | |||||||

| Percentage Female | 19 | 3,468 | <·01 | ·59 | |||||||

| Sample Type | 17 | 3,330 | ·02 | ||||||||

| Clinical | 12 | 1·53 | 1·19–1·97 | <·01 | 67.98% | <·01 | |||||

| Community | 5 | 2·45 | 1·78–3·36 | <·0001 | 0% | .90 | |||||

| Childhood Maltreatment Measure | 19 | 3,468 | ·68 | ||||||||

| NSSI Measure | 19 | 3,468 | ·82 | ||||||||

| NSSI Timeframeb | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

Note: k = number of unique effects; OR = pooled odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

In analyses of sample type, at-risk and clinical samples were combined and compared to community samples.

Not enough observations from studies employing interview measures of childhood maltreatment (k = 2) were available for moderator analysis.

All but two studies analyzed lifetime history of NSSI in relation to childhood maltreatment, and thus moderator analysis was not conducted.

The category with the smallest effect size in univariate moderator analysis served as the reference group in the corresponding meta-regression analysis.

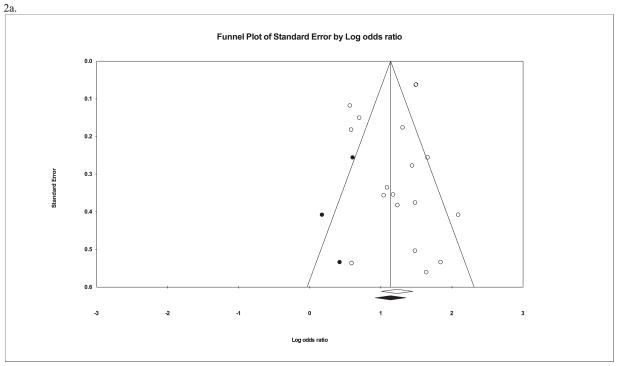

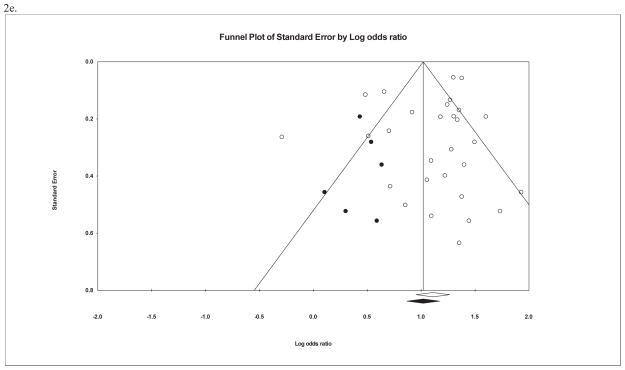

In terms of potential publication bias (Table 2), Orwin’s fail-safe-N indicated that 215 unpublished studies with an OR of 1·0 would be required to reduce the pooled effect size for the relation between overall maltreatment and NSSI to 1.1 (an a priori trivial effect size), suggesting that the observed weighted effect size is robust. Egger’s regression test indicated that there was no significant publication bias. Additionally, the funnel plot of effect sizes was not notably asymmetrical (Figure 2a). The adjusted OR produced with the trim-and-fill method was reduced but remained medium-to-large.

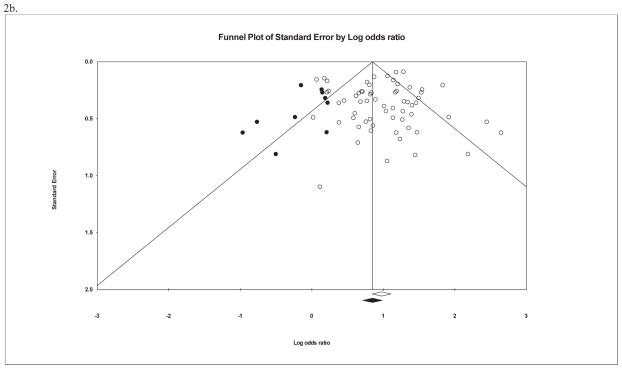

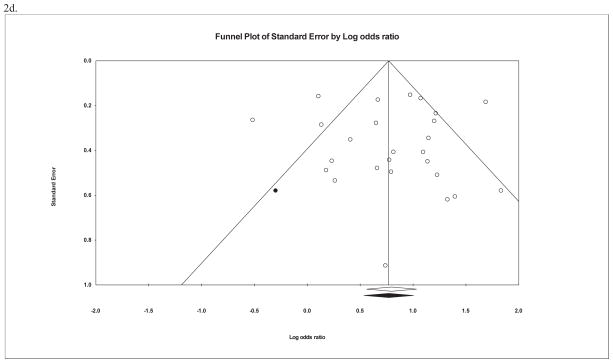

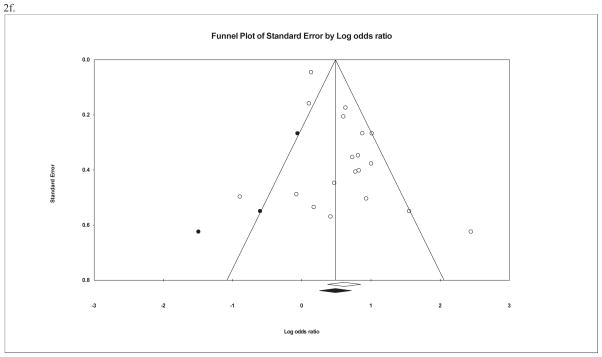

Figure 2.

Funnel plot for effect sizes in the meta-analyses. The vertical line indicates the weighted mean effect. Open circles indicate observed effects for actual studies, and closed circles indicate imputed effects for studies believed to be missing due to publication bias. The clear diamond reflects the unadjusted weighted mean effect size, whereas the black diamond reflects the weighted mean effect size after adjusting for publication bias.

2a. Overall childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury

2b. Childhood sexual abuse and non-suicidal self-injury

2c. Childhood physical abuse and non-suicidal self-injury

2d. Childhood physical neglect and non-suicidal self-injury

2e. Childhood emotional abuse and non-suicidal self-injury

2f. Childhood emotional neglect and non-suicidal self-injury

Univariate associations between childhood maltreatment subtypes and NSSI

When specific forms of childhood maltreatment were examined, all five subtypes were positively associated with NSSI. Pooled OR’s ranged from small-to-medium for emotional neglect to medium-to-large for emotional abuse. When sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the effect of including individuals with a suicide attempt history in the NSSI groups (i.e., with NSSI-only groups replaced by groups with NSSI, regardless of suicide attempt history), the results were largely unchanged (Appendix 1). Heterogeneity proved significant for all maltreatment subtypes. A summary of these results is presented in Table 2.

In moderator analyses (Table 3), sample type emerged most frequently as a significant moderator, with the association with NSSI stronger in community than clinical/at-risk samples for physical abuse and neglect as well as emotional abuse and neglect. However, a consistent pattern was not observed in terms of heterogeneity; heterogeneity appeared higher for community samples in the case of physical abuse, but lower in the case of emotional abuse and neglect, and relatively comparable to heterogeneity for clinical samples in the case of physical neglect (Appendix 2). Time-frame of NSSI measure was also a significant moderator for sexual abuse and physical neglect, in both cases the association being stronger for NSSI with the past year than over the lifetime. For emotional abuse, stronger associations were observed for self-report measures of maltreatment and NSSI than interview-based measures. In multivariate meta-regression analyses, both sample type and time-frame of NSSI measure remained significant moderators of the association between physical neglect and NSSI. For emotional abuse, only method of measuring NSSI remained a significant moderator. The meta-regression models accounted for a large proportion of the variance in the effect sizes for physical neglect (R2 = ·68) and emotional abuse (R2 = ·77), respectively.

Regarding potential publication bias for studies of maltreatment subtypes, fail-safe N’s ranged from 103 to 583. Egger’s regression test indicated significant publication bias only in the case of emotional neglect. Similarly, with the exception of emotional neglect, funnel plots of the effect sizes for maltreatment subtypes were not asymmetrical, suggesting no presence of publication bias (Figures 2b to 2f). Although the trim-and-fill method produced a reduction in estimated effect sizes, significant effects remained for all maltreatment subtypes. These results are presented in Table 2.

Multivariate associations between childhood maltreatment and NSSI

Overall maltreatment remained significantly associated with NSSI in analyses that included all available covariates (OR = 2·79 [95% CI = 2·15–3·63], p < ·001). Similarly, all maltreatment subtypes remained significantly associated with NSSI in analyses that adjusted for covariates (ORChildhood Sexual Abuse = 1·62 [95% CI = 1·38–1·90], p < ·0001; ORChildhood Physical Abuse = 1·73 [95% CI = 1·38–2·17], p < ·0001; OR Childhood Physical Neglect = 1·24 [95% CI = 1·00–1·52], p < ·05; ORChildhood Emotional Abuse = 1·86 [95% CI = 1·42–2·44], p < ·0001; ORChildhood Emotional Neglect = 1·17 [95% CI = 1·02–1·35], p = ·03). Note that in the case of physical abuse, an outlier was excluded from analysis, and the lower end of the confidence interval for physical neglect was rounded down but exceeded 1.00. To account for the high rates with which different forms of maltreatment co-occur,92–94 these analyses were repeated and restricted to ones that covaried at least one maltreatment subtype (Appendix 3). With the exception of the association with emotional neglect becoming non-significant, the results remained largely unchanged.

Childhood maltreatment and severity of NSSI

In analyses restricted to individuals who engaged in NSSI (Appendix 4), overall maltreatment and three subtypes (sexual abuse, and physical abuse and neglect) were associated with the severity of this behavior. Emotional neglect was not associated with NSSI severity, and not enough studies investigated the association between emotional abuse and NSSI severity for meta-analysis (k = 2).

Qualitative review of mediators and moderators

Thirteen studies, all cross-sectional, evaluated candidate mediators of the association between childhood maltreatment subtypes and NSSI. Five found support for psychiatric morbidity as mediators, including general psychiatric comorbidity for overall maltreatment,25 PTSD and dissociation for sexual abuse,83,85 and personality dysfunction for emotional maltreatment and physical abuse,46 and dissociation for physical abuse.46,72 Four studies focusing on self-concepts reported that academic self-efficacy, self-criticism, and pessimism were mediators for emotional abuse,33,34,47 and self-blame for physical abuse.72 Another three found emotion dysregulation to be a mediator for overall maltreatment66 and neglect,31 and emotional expressivity a mediator for emotional but not physical or sexual abuse.75 Three studies of impulsivity found negative urgency, but not other forms of trait or behavioral impulsivity, to be a mediator for overall maltreatment.23–25

Three studies examined potential moderators. One observed the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism to be a moderator for emotional maltreatment.28 Another found an interaction between emotional expressivity, negative affect intensity, and overall maltreatment.49 A third noted that overall maltreatment was not moderated by negative urgency.23

Discussion

The current review provides the most comprehensive synthesis to date of the empirical literature on childhood maltreatment and NSSI. Collectively, these findings provide support for childhood maltreatment, and its specific subtypes, being associated with NSSI, although the current evidence is modest in the case of emotional neglect. Despite this commonality among maltreatment subtypes in being linked with NSSI, subtypes of childhood maltreatment should not be considered as a unitary construct. They might be associated with NSSI through different mediational pathways (i.e., equifinality95), as with other mental health outcomes,96,97 and treating them as one construct risks obscuring these important differences and their clinical implications.

Our findings differ from that of the earlier meta-analysis of sexual abuse and NSSI.12 Whereas the prior review reported a modest effect size and evidence of publication bias, we found a medium effect size and no publication bias. Furthermore, whereas the earlier review found this association was non-significant after accounting for covariates in qualitative analyses, we found a modest but significant meta-analytic association. These differences may be partly due to the inclusion of 43 new studies of sexual abuse in the present meta-analysis, lending weight to the current findings.

The results of our review are congruent with the view that screening for childhood maltreatment history may be important in assessing risk for NSSI. Moreover, the finding across multiple maltreatment subtypes that the association with NSSI is stronger in non-clinical samples, with medium to large effects, suggests that screening for history of childhood maltreatment may be of most benefit in community settings. Childhood maltreatment is associated with multiple other clinical outcomes (e.g., depression and bipolar disorder11,98,99), and may therefore be less of a distinguishing factor for NSSI in clinical populations where such disorders are more prevalent. Age was a significant moderator only for overall maltreatment, with a stronger effect in adolescence. This suggests that although NSSI is more common in adolescence,2 it is not due to a stronger association with maltreatment at this age, and that maltreatment may thus confer long-term risk for NSSI that extends into adulthood. This possibility is consistent with findings of significant long-term deleterious effects of childhood maltreatment on mental health.99–101 Thus, preventing maltreatment and early intervention with maltreatment victims are very important. Although NSSI is more prevalent among females,102 our moderator analyses indicated that this is unlikely to be due to potential sex differences in susceptibility to the detrimental effects of childhood maltreatment.103 Rather, sex differences in the prevalence of NSSI may be better accounted for by greater exposure in females to maltreatment experiences, at least in the case of sexual abuse.104,105 Given that childhood maltreatment seems to be no less deleterious in males than females with regards to NSSI as a clinical outcome, the current findings suggest that it should be accorded comparable weight in risk stratification for both sexes. Emotional abuse has received considerably less attention than childhood sexual and physical abuse in relation to NSSI. This may, in part, be due to the long-held view by clinicians and researchers alike that it is the least damaging form of abuse.106–108 Contrasting with this perception, the finding in our analyses of the largest effect for this maltreatment subtype adds to the accumulating evidence that its pathogenic impact is comparable to, if not larger than, that of other abuse subtypes in relation to several mental health outcomes (e.g., depression99,101,109 and bipolar disorder110). The relative neglect of emotional abuse is all the more consequential given that it is the most prevalent form of abuse.111 Greater emphasis on this abuse subtype in NSSI risk assessment and research is therefore warranted.

Delineating moderators and mediational pathways through which childhood maltreatment may be associated with NSSI is of value for its potential to advance risk stratification strategies and to identify promising candidates for targeted intervention. Existing evidence is modest, with preliminary support currently strongest for negative cognitive tendencies as mediators for emotional abuse, and negative urgency for overall maltreatment. All studies in this area were cross-sectional, and should thus be interpreted with caution.112,113 Future research, particularly on cognitive and biological mechanisms, is needed for the development of novel treatment approaches for individuals with maltreatment histories.

Finally, the current findings must be interpreted within the context of several important limitations. First is the paucity of primary studies employing longitudinal analyses. Establishing the temporal relation between maltreatment and NSSI is a necessary first step toward determining the potential causal role of maltreatment in this clinical outcome.114 Second, with few exceptions,74,85,115 most studies used retrospective recall of maltreatment. Although retrospective recall of adverse childhood experiences appears to be reasonably accurate,116,117 prospective assessment of maltreatment allows for more precise estimations of its association with NSSI. Third, only one study26 focused on early adolescence (ages 12–13). Future research on the transition from childhood to adolescence is important, given NSSI onset typically occurs during this period of development.118,119 Fourth, only seven studies4,26,37,48,60,73,76 allowed for analyses of “pure” NSSI (i.e., unconfounded by its naturally high co-occurrence with suicide attempt history5,120) in relation to childhood maltreatment. As suicidal behavior is also associated with childhood maltreatment,121 future research cleanly separating it from NSSI is required accurately to assess the latter in relation to childhood maltreatment. Finally, substantial heterogeneity often remained among studies after moderator analysis. One potential contributor to heterogeneity is the NSSI measure used. Although NSSI measurement medium was generally not a significant moderator, other aspects of NSSI measurement influence prevalence estimates (i.e., single-item versus multi-item measures of NSSI methods)2 and might influence heterogeneity here. Comprehensive and standardized assessment of NSSI methods across studies would therefore be important for accurately characterizing NSSI in relation to its risk factors.

In conclusion, there was consistent evidence that childhood maltreatment in its different manifestations, with the exception of emotional neglect, was associated with engagement in NSSI. The current review also highlights the need for greater consideration of emotional abuse in evaluations of risk for NSSI, particularly in community settings. Future longitudinal research investigating moderators and mediating mechanisms has potential to guide efforts to minimize risk for NSSI in individuals with a maltreatment history.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

We searched Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO for articles in English and published from inception to September 25, 2017, that assessed the association between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), using the search terms: (self-injur* OR parasuicid* OR " self-harm" OR "self-mutilation") AND ("emotional abuse" OR "emotionally abused" OR "emotional victimization" OR "emotionally victimized" OR "verbal abuse" OR "verbally abused" OR "psychological abuse" OR "psychologically abused" OR "physical abuse" OR "physically abused" OR "sexual abuse" OR "sexually abused" OR "sex abuse" OR maltreat* OR "childhood neglect" OR "child neglect" OR "childhood abuse" OR "child abuse"). This was supplemented by a search of the references of a prior meta-analysis of childhood sexual abuse and NSSI. After excluding duplicates and ineligible publications, we identified 71 relevant studies that evaluated the association between childhood maltreatment with NSSI.

Added value of this study

We conducted the most comprehensive review to date of the association between childhood maltreatment and NSSI, this being the first such review to expand beyond childhood sexual abuse. With 43 new studies of childhood sexual abuse in the current meta-analysis, it provides a significant update to a prior meta-analysis of childhood sexual abuse. Additionally, we quantitatively evaluated childhood maltreatment in relation to NSSI after accounting for covariates and supplemented our analyses with a systematic qualitative review of studies examining mediators and moderators of this association. With the exception of childhood emotional neglect, childhood maltreatment and its subtypes were consistently associated with NSSI, and these findings were not artifacts of publication bias or shared correlates. Across multiple maltreatment subtypes, stronger associations with NSSI were found in community samples.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings suggest that: (i) screening for childhood maltreatment history may be important in assessing risk for NSSI; (ii) such screening may be particularly valuable in community settings; (iii) a history of childhood maltreatment should be accorded comparable weight in risk stratification for both sexes rather than a greater emphasis be given with females; and (iv) countering the prevailing view in research and practice that childhood emotional abuse is less associated with NSSI than are childhood sexual and physical abuse, it may be comparably, if not more, relevant to this outcome, warranting greater attention to this maltreatment subtype, especially with it being the most prevalent form of childhood abuse. The current review also highlights the need for longitudinal research more precisely delineating the temporal nature of the relation between childhood maltreatment, NSSI, and potential mediating mechanisms underlying this association for the potential of work in this area to yield promising candidates for targeted intervention.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The National Institute of Mental Health under Award Numbers R01MH101138 and R21MH112055.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

None.

Author Contributions

RTL designed the study, extracted the data, and conducted the analyses. All authors contributed to the literature search, data collection, and preparation of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nock MK. Self-injury. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:339–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2014;44:273–303. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitlock J, Eckenrode J, Silverman D. Self-injurious behaviors in a college population. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1939–48. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asarnow JR, Porta G, Spirito A, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, et al. Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents: Findings from the TORDIA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:772–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP, et al. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2016;46:225–36. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Dubicka B, Goodyer I. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT) Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:495–501. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calati R, Courtet P. Is psychotherapy effective for reducing suicide attempt and non-suicidal self-injury rates? Meta-analysis and meta-regression of literature data. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;79:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, Asarnow JR. Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:97–107. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gratz KL. Risk factors for and functions of deliberate self-harm: An empirical and conceptual review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10:192–205. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yates TM. The developmental psychopathology of self-injurious behavior: Compensatory regulation in posttraumatic adaptation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:35–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teicher MH, Samson JA. Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology: A case for ecophenotypic variants as clinically and neurobiologically distinct subtypes. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1114–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12070957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klonsky ED, Moyer A. Childhood sexual abuse and non-suicidal self-injury: Meta analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:166–70. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J. The cost of dichotomization. Appl Psychol Meas. 1983;7:249–53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:19–40. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maxwell SE, Delaney HD. Bivariate median splits and spurious statistical significance. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:181–90. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruscio AM, Ruscio J. The latent structure of analogue depression: Should the Beck Depression Inventory be used to classify groups? Psychol Assess. 2002;14:135–45. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biostat. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3. Englewood, NJ: Biostat; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orwin RG. A Fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. J Educ Stat. 1983;8:157–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akyuz G, Sar V, Kugu N, Doǧan O. Reported childhood trauma, attempted suicide and self-mutilative behavior among women in the general population. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arens AM, Gaher RM, Simons JS. Child maltreatment and deliberate self-harm among college students: Testing mediation and moderation models for impulsivity. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82:328–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arens AM, Gaher RM, Simons JS, Dvorak RD. Child maltreatment and deliberate self-harm. Child Maltreat. 2014;19:168–77. doi: 10.1177/1077559514548315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auerbach RP, Kim JC, Chango JM, Spiro WJ, Cha C, Gold J, et al. Adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: examining the role of child abuse, comorbidity, and disinhibition. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220:579–84. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baiden P, Stewart SL, Fallon B. The role of adverse childhood experiences as determinants of non-suicidal self-injury among children and adolescents referred to community and inpatient mental health settings. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;69:163–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernegger A, Kienesberger K, Carlberg L, Swoboda P, Ludwig B, Koller R, et al. Influence of sex on suicidal phenotypes in affective disorder patients with traumatic childhood experiences. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bresin K, Sima Finy M, Verona E. Childhood emotional environment and self-injurious behaviors: The moderating role of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Briere J, Gil E. Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: prevalence, correlates, and functions. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:609–20. doi: 10.1037/h0080369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown L, Russell J, Thornton C, Dunn S. Dissociation, abuse and the eating disorders: evidence from an Australian population. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1999;33:521–8. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buckholdt KE, Parra GR, Jobe-Shields L. Emotion regulation as a mediator of the relation between emotion socialization and deliberate self-harm. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:482–90. doi: 10.1037/a0016735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burke TA, Ammerman BA, Knorr AC, Alloy LB, McCloskey MS. Measuring acquired capability for suicide within an ideation-to-action framework. Psychol Violence. 2017 doi: 10.1037/vio0000090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buser T, Hackney H. Explanatory style as a mediator between childhood emotional abuse and nonsuicidal self-injury. J Ment Heal Couns. 2012;34:154–69. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buser TJ, Peterson CH, Kearney A. Self-efficacy pathways between relational aggression and nonsuicidal self-injury. J Coll Couns. 2015;18:195–208. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cater ÅK, Andershed A-K, Andershed H. Youth victimization in Sweden: Prevalence, characteristics and relation to mental health and behavioral problems in young adulthood. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:1290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cerutti R, Manca M, Presaghi F, Gratz KL. Prevalence and clinical correlates of deliberate self-harm among a community sample of Italian adolescents. J Adolesc. 2011;34:337–47. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Turner BJ. Risk-related and protective correlates of nonsuicidal self-injury and co-occurring suicide attempts among incarcerated women. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2014;44:139–54. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Claes L, Vandereycken W. Is there a link between traumatic experiences and self-injurious behaviors in eating-disordered patients? Eat Disord. 2007;15:305–15. doi: 10.1080/10640260701454329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Croyle KL, Waltz J. Subclinical self-harm: Range of behaviors, extent, and associated characteristics. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:332–42. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darke S, Torok M. Childhood physical abuse, non-suicidal self-harm and attempted suicide amongst regular injecting drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:420–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Pierro R, Sarno I, Perego S, Gallucci M, Madeddu F. Adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: The effects of personality traits, family relationships and maltreatment on the presence and severity of behaviours. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21:511–20. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evren C, Evren B. Self-mutilation in substance-dependent patients and relationship with childhood abuse and neglect, alexithymia and temperament and character dimensions of personality. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evren C, Kural S, Cakmak D. Clinical correlates of self-mutilation in Turkish male substance-dependent inpatients. Psychopathology. 2006;39:248–54. doi: 10.1159/000094722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evren C, Sar V, Evren B, Dalbudak E. Self-mutilation among male patients with alcohol dependency: the role of dissociation. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:489–95. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evren C, Cinar O, Evren B, Celik S. Relationship of self-mutilative behaviours with severity of borderline personality, childhood trauma and impulsivity in male substance-dependent inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gladstone GL, Parker GB, Mitchell PB, Malhi GS, Wilhelm K, Austin M-P. Implications of childhood trauma for depressed women: An analysis of pathways from childhood sexual abuse to deliberate self-harm and revictimization. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1417–25. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glassman LH, Weierich MR, Hooley JM, Deliberto TL, Nock MK. Child maltreatment, non-suicidal self-injury, and the mediating role of self-criticism. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:2483–90. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gorodetsky E, Carli V, Sarchiapone M, Roy A, Goldman D, Enoch MA. Predictors for self-directed aggression in Italian prisoners include externalizing behaviors, childhood trauma and the serotonin transporter gene polymorphism 5-HTTLPR. Genes, Brain Behav. 2016;15:465–73. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gratz KL. Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among female college students: The role and interaction of childhood maltreatment, emotional inexpressivity, and affect intensity/reactivity. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:238–50. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gratz KL, Chapman AL. The role of emotional responding and childhood maltreatment in the development and maintenance of deliberate self-harm among male undergraduates. Psychol Men Masc. 2007;8:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gratz KL, Conrad SD, Roemer L. Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among college students. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72:128–40. doi: 10.1037//0002-9432.72.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Isohookana R, Riala K, Hakko H, Räsänen P. Adverse childhood experiences and suicidal behavior of adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jaquier V, Hellmuth JC, Sullivan TP. Posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms as correlates of deliberate self-harm among community women experiencing intimate partnerviolence. Psychiatry Res. 2013;206:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaess M, Parzer P, Mattern M, Plener PL, Bifulco A, Resch F, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and their impact on frequency, severity, and the individual function of nonsuicidal self-injury in youth. Psychiatry Res. 2013;206:265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaplan C, Tarlow N, Stewart JG, Aguirre B, Galen G, Auerbach RP. Borderline personality disorder in youth: The prospective impact of child abuse on non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;71:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kara K, Ozsoy S, Teke H, Congologlu MA, Turker T, Renklidag T, et al. Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior in forensic child and adolescent populations: Clinical features and relationship with depression. Neurosciences. 2015;20:31–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karagöz B, Dağ İ. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and emotional dysregulation in self mutilation: An investigation among substance dependent patients. Arch Neuropsychiatry. 2015;52:8–14. doi: 10.5152/npa.2015.6769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lipschitz DS, Winegar RK, Nicolaou AL, Hartnick E, Wolfson M, Southwick SM. Perceived abuse and neglect as risk factors for suicidal behavior in adolescent inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:32–9. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199901000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lüdtke J, In-Albon T, Michel C, Schmid M. Predictors for DSM-5 nonsuicidal self-injury in female adolescent inpatients: The role of childhood maltreatment, alexithymia, and dissociation. Psychiatry Res. 2016;239:346–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maloney E, Degenhardt L, Darke S, Nelson EC. Investigating the co-occurrence of self-mutilation and suicide attempts among opioid-dependent individuals. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2010;40:50–62. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martin J, Bureau JF, Cloutier P, Lafontaine MF. A comparison of invalidating family environment characteristics between university students engaging in self-injurious thoughts & actions and non-self-injuring university students. J Youth Adolesc. 2011;40:1477–88. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin J, Bureau JF, Yurkowski K, Fournier TR, Lafontaine MF, Cloutier P. Family-based risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury: Considering influences of maltreatment, adverse family-life experiences, and parent-child relational risk. J Adolesc. 2016;49:170–80. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Muehlenkamp JJ, Kerr PL, Bradley AR, Adams Larsen M, Larsen MA. Abuse subtypes and nonsuicidal self-injury: Preliminary evidence of complex emotion regulation patterns. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:258–63. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181d612ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nijman HLI, Dautzenberg M, Merckelbach HLGJ, Jung P, Wessel I, Campo J. Self-mutilating behaviour of psychiatric inpatients. Eur Psychiatry. 1999;14:4–10. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(99)80709-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parker G, Malhi G, Mitchell P, Kotze B, Wilhelm K, Parker K. Self-harming in depressed patients: Pattern analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:899–906. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peh CX, Shahwan S, Fauziana R, Mahesh MV, Sambasivam R, Zhang YJ, et al. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking child maltreatment exposure and self-harm behaviors in adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;67:383–90. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rabinovitch SM, Kerr DCR, Leve LD, Chamberlain P. Suicidal behavior outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: Longitudinal study of adjudicated girls. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2015;45:431–47. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reddy SD, Negi LT, Dodson-Lavelle B, Ozawa-de Silva B, Pace TWW, Cole SP, et al. Cognitive-based compassion training: A promising prevention strategy for at-risk adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2013;22:219–30. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reichl C, Heyer A, Brunner R, Parzer P, Völker JM, Resch F, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, childhood adversity and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;74:203–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roe-Sepowitz D. Characteristics and predictors of self-mutilation: A study of incarcerated women. Crim Behav Ment Heal. 2007;17:312–21. doi: 10.1002/cbm.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stewart SL, Baiden P, Theall-Honey L. Examining non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents with mental health needs, in Ontario, Canada. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18:392–409. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.824838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Swannell S, Martin G, Page A, Hasking P, Hazell P, Taylor A, et al. Child maltreatment, subsequent non-suicidal self-injury and the mediating roles of dissociation, alexithymia and self-blame. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36:572–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ, Borowsky IW, McMorris BJ, Kugler KC. Factors distinguishing youth who report self-injurious behavior: a population-based sample. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12:205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tatnell R, Hasking P, Newman L, Taffe J, Martin G. Attachment, emotion regulation, childhood abuse and assault: Examining predictors of NSSI among adolescents. Arch Suicide Res. 2016;0:1–11. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2016.1246267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomassin K, Shaffer A, Madden A, Londino DL. Specificity of childhood maltreatment and emotion deficit in nonsuicidal self-injury in an inpatient sample of youth. Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:103–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tresno F, Ito Y, Mearns J. Self-injurious behavior and suicide attempts among Indonesian college students. Death Stud. 2012;36:627–39. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2011.604464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tresno F, Ito Y, Mearns J. Risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury in Japanese college students : The moderating role of mood regulation expectancies. Int J Psychol. 2013;48:1009–17. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.733399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsai MH, Chen YH, Chen CD, Hsiao CY, Chien CH. Deliberate self-harm by Taiwanese adolescents. Acta Pædiatrica. 2011;100:223–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Turell SC, Armsworth MW. Differentiating incest survivors who self-mutilate. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24:237–49. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tyler KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Johnson KD. Self-mutilation and homeless youth: The role of family abuse, street experiences, and mental disorders. J Res Adolesc. 2003;13:457–74. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wachter T, Murphy S, Kennerley H, Wachter S. A preliminary study examining relationships between childhood maltreatment, dissociation, and self-injury in psychiatric outpatients. J Trauma Dissociation. 2009;10:261–75. doi: 10.1080/15299730902956770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wan Y, Chen J, Sun Y, Tao F. Impact of childhood abuse on the risk of non-suicidal self-injury in mainland Chinese adolescents. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weierich MR, Nock MK. Posttraumatic stress symptoms mediate the relation between childhood sexual abuse and nonsuicidal self-injury. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:39–44. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weismoore JT, Esposito-Smythers C. The role of cognitive distortion in the relationship between abuse, assault, and non-suicidal self-injury. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:281–90. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9452-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yates TM, Carlson EA, Egeland B. A prospective study of child maltreatment and self-injurious behavior in a community sample. Dev Psychopathol [Internet] Brown University Library. 2008;20:651–71. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000321. Available from: http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0954579408000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zanarini MC, Yong L, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Marino MF, et al. Severity of reported childhood sexual abuse and its relationship to severity of borderline psychopathology and psychosocial impairment among borderline inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:381–7. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zanarini MC, Laudate CS, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G. Predictors of self-mutilation in patients with borderline personality disorder: A 10-year follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:823–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zetterqvist M, Lundh L-G, Svedin C. A cross-sectional study of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: support for a specific distress-function relationship. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2014;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zlotnick C, Shea MT, Pearlstein T, Simpson E, Costello E, Begin A. The relationship between dissociative symptoms, alexithymia, impulsivity, sexual abuse, and self-mutilation. Compr Psychiatry. 1996;37:12–6. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zoroglu SS, Tuzun U, Sar V, Tutkun H, Savaş HA, Ozturk M, et al. Suicide attempt and self-mutilation among Turkish high school students in relation with abuse, neglect and dissociation. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57:119–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zweig-Frank H, Paris J, Guzder J. Psychological risk factors for dissociation and self-mutilation in female patients with borderline personality disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 1994;39:259–64. doi: 10.1177/070674379403900504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Higgins DJ, McCabe MP. Multi-type maltreatment and the long-term adjustment of adults. Child Abus Rev. 2000;9:6–18. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Teicher MH, Samson JA, Polcari A, McGreenery CE. Sticks, stones, and hurtful words: Relative effects of various forms of childhood maltreatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:993–1000. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 1996;8:597–600. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rose DT, Abramson LY. Developmental predictors of depressive cognitive style: Research and theory. In: Cicchetti D, Toth S, editors. Rochester Symposium of Developmental Psychopathology. Vol. 4. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1992. pp. 323–49. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gibb BE. Childhood maltreatment and negative cognitive styles: A quantitative and qualitative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22:223–46. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Agnew-Blais J, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment and unfavourable clinical outcomes in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:342–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00544-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu RT. Childhood adversities and depression in adulthood: Current findings and future directions. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2017;24:140–53. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nanni V, Uher R, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: A meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;169:141–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nelson J, Klumparendt A, Doebler P, Ehring T. Childhood maltreatment and characteristics of adult depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;201:96–104. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.180752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bresin K, Schoenleber M. Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;38:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Weiss EL, Longhurst JG, Mazure CM. Childhood sexual abuse as a risk factor for depression in women: Psychosocial and neurobiological correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:816–28. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pereda N, Guilera G, Forns M, Gómez-Benito J. The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:328–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stoltenborgh M, van IJzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat. 2011;16:79–101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Egeland B. Taking stock: Childhood emotional maltreatment and developmental psychopathology. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:22–6. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kaplan SJ, Pelcovitz D, Labruna V. Child and adolescent abuse and neglect research: a review of the past 10 years. Part I: Physical and emotional abuse and neglect. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1214–22. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Trickett PK, Mennen FE, Kim K, Sang J. Emotional abuse in a sample of multiply maltreated, urban young adolescents: Issues of definition and identification. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Med. 2012;9:e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Etain B, Mathieu F, Henry C, Raust A, Roy I, Germain A, et al. Preferential association between childhood emotional abuse and bipolar disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23:376–83. doi: 10.1002/jts.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LRA, van IJzendoorn MH. The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: Review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abus Rev. 2015;24:37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol Methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Winer ES, Cervone D, Bryant J, McKinney C, Liu RT, Nadorff MR. Distinguishing mediational models and analyses in clinical psychology: Atemporal associations do not imply causation. J Clin Psychol. 2016;72:947–55. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:337–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]