Abstract

We demonstrate molecular similarity to be a surprisingly effective metric for proposing and ranking one-step retrosynthetic disconnections based on analogy to precedent reactions. The developed approach mimics the retrosynthetic strategy defined implicitly by a corpus of known reactions without the need to encode any chemical knowledge. Using 40 000 reactions from the patent literature as a knowledge base, the recorded reactants are among the top 10 proposed precursors in 74.1% of 5000 test reactions, providing strong quantitative support for our methodology. Extension of the one-step strategy to multistep pathway planning is demonstrated and discussed for two exemplary drug products.

Short abstract

We demonstrate molecular similarity to be a surprisingly effective metric for proposing and ranking one-step retrosynthetic disconnections based on analogy to precedent reactions. The developed approach mimics the retrosynthetic strategy defined implicitly by a corpus of known reactions without the need to encode any chemical knowledge. Using 40 000 reactions from the patent literature as a knowledge base, the recorded reactants are among the top 10 proposed precursors in 74.1% of 5000 test reactions, providing strong quantitative support for our methodology. Extension of the one-step strategy to multistep pathway planning is demonstrated and discussed for two exemplary drug products.

Introduction

In order to synthesize a target chemical compound, it is necessary to identify a series of suitable reaction steps beginning from available starting materials. This analysis—starting from the target compound and working backward—dates as far back as Robert Robinson’s seminal 1917 work on the synthesis of tropinone.1 It was later formalized as retrosynthesis by E. J. Corey, ultimately leading to his receiving the 1990 Nobel Prize.2 This formalization prompted the development of computer assistance with the intent of allowing chemists to focus on what to make, rather than how to make it; much of the field’s development in the following years was led by J. Gasteiger.3 Computer assisted synthesis planning has been well-reviewed over the years.4−7

From the very first attempt at computer-assistance in retrosynthesis planning,8 the vast majority of automated retrosynthesis programs have relied on encoding reaction templates, or generalized subgraph matching rules. These template-based approaches require a decision to be made about the extent of generalization and abstraction, whether extracted algorithmically from reaction databases9−17 or encoded by hand.16,18−20 Various techniques have been developed to extract the likely meaningful context around the reaction center, including through the consideration of nonstructural reactivity descriptors, but the trade-off of specificity and coverage is inevitable. Moreover, application of templates is computationally expensive due to the cost of solving the subgraph isomorphism problem, and so these approaches do not scale well for large template sets.14,21 Similar considerations apply to the task of forward prediction,22 which has been the subject of several recent studies.14,16,23,24

Liu et al.21 report a neural model based on the seq2seq architecture, inspired by a similar study examining the goal of forward synthesis.25 The problem of one-step retrosynthesis is treated as a translation task, converting one sequence of characters (i.e., a product SMILES26 string without atom mapping) to another sequence of characters (i.e., a reactant(s) SMILES string). They report comparable performance to a baseline model that applies a library of algorithmically extracted reaction templates and ranks candidate precursors in order of decreasing template popularity.

Cadeddu et al.27 treat retrosynthesis in terms of chemical linguistics, where the rarest bonds are proposed as the sites of disconnections. This is similar to other techniques where an attempt is made to reduce molecular complexity as rapidly as possible.28 However, identifying the reaction site is only sufficient to propose synthons,29 or nonphysical fragments of precursors. Given one or more synthons resulting from a proposed retrosynthetic step, it is still necessary to propose specific functionalities to create synthetic equivalents (i.e., specify leaving groups). Hereafter we use the term “leaving group” to mean any functionality added to a synthon to yield its synthetic equivalent.

Despite their limitations, reaction templates still provide a very useful way of encoding transformations, particularly in their ability to fully specify chemical precursors. For example, cleaving a single bond between two aromatic carbons is associated with 57 different leaving group pairs (not all of which are unique, due to symmetry) in our ca. 40 000 reaction training data set, described later; the most common are depicted in Figure 1. The reaction site, consisting of the atom–bond–atom subgraph pattern, can be encoded in a SMARTS30 string representation as [cH0]–[cH0]. The abundance of distinct leaving groups for equivalent reaction sites has been described as a limitation of template-based approaches, as it necessitates a proliferation of distinct templates corresponding to each set of leaving groups.21

Figure 1.

Six most-frequent precursors for the disconnection of a single bond between two aromatic carbons. Once a strategic disconnection is identified (SMARTS: [cH0]–[cH0]), there may still be dozens of locally plausible precursors to accomplish the transformation, including different combinations of halides and boronic acid/esters. (1) Bromide and acid; (2) bromide and ester; (3) chloride and acid; (4) iodide and acid; (5) chloride and ester; (6) iodide and ester.

Herein, we propose and validate a similarity-based approach whereby strategic disconnections are performed based solely on analogy to known reaction precedents. Reaction templates are used only at the most rudimentary level to generate chemically valid precursor molecules, circumventing the need to specify precise levels of generalization. This is a purely data-driven approach to retrosynthesis, where model suggestions can be thought of as an interpolation of known reactions to novel substrates, rather than an extrapolation to novel chemistries. In other words, this approach is intended to mimic the “average retrosynthetic strategy” implicit in a reaction corpus. It is purely deterministic, acting directly on the available data, and does not require tuning or training of any model parameters.

Approach

Overview

Our approach is motivated by the first question a chemist might ask when tasked with developing a synthesis plan to a target molecule: how have similar molecules been synthesized? If a route to the molecule has been previously published, it may be appropriate to use that route without modification. If it is a novel compound, then one might look at routes to other compounds with similar structural motifs and determine whether that synthetic strategy is applicable. This analysis is formalized into an automated workflow in the following paragraphs. A more detailed description of its implementation can be found in the Supporting Information.

First, reaction precedents are retrieved from the knowledge base based on product similarity, sprod, scored between 0 and 1. Molecular similarity is described in the following section. In our previous work,14 we saw quantitative evidence that similar products tend to be produced by similar reactions. This is not that surprising, as often the first approach in a manual retrosynthesis is examining how molecules with similar functionalities are produced (e.g., by searching Reaxys31 or SciFinder32). We restrict the number of precedent reactions to be 100 to limit the computational time required in subsequent steps.

Second, a highly local transform containing fully specified leaving groups is extracted from each precedent reaction and applied to the target compound. In contrast to traditional template extraction approaches that attempt to include neighboring atoms as necessary context,12−15 these templates contain only the atoms that are immediately involved in the reaction (specified by atomic identity, aromaticity, number of hydrogen atoms, and chirality if applicable). Using the example of Figure 1, the template for a Suzuki reaction would consist only of the two aromatic carbons that are bridged in the product and the unmapped halogen and boronic acid/ester leaving groups. This template is applied to the target compound, which may yield several candidate precursors or yield none. Importantly, because templates are only applied when the precedent’s product is similar to the target compound, it is not as important to heuristically determine the important context around the reaction center or manually encode reactivity conflicts (as done by Szymkuc et al.20 among others); that is implicitly handled by the previous and upcoming similarity calculations.

Third, candidate precursors are further scored by their similarity to that precedent’s reactants, sreac, between 0 and 1. Precursors are analyzed as if they were a single molecule, so that it is possible to use intramolecular reactions as the basis for intermolecular suggestions (and vice versa). Comparing reactant similarity ensures that not only are the product molecules similar, but the precursors themselves are as well. The resulting candidates are ranked by the overall similarity score as calculated by multiplying product similarity and reactants similarity, s = sprod·sreac. This overall score measures the extent of the match between the proposed reaction and the information upon which the suggestion is based; a score of 1.0 would indicate an exact match to a known disconnection in the database.

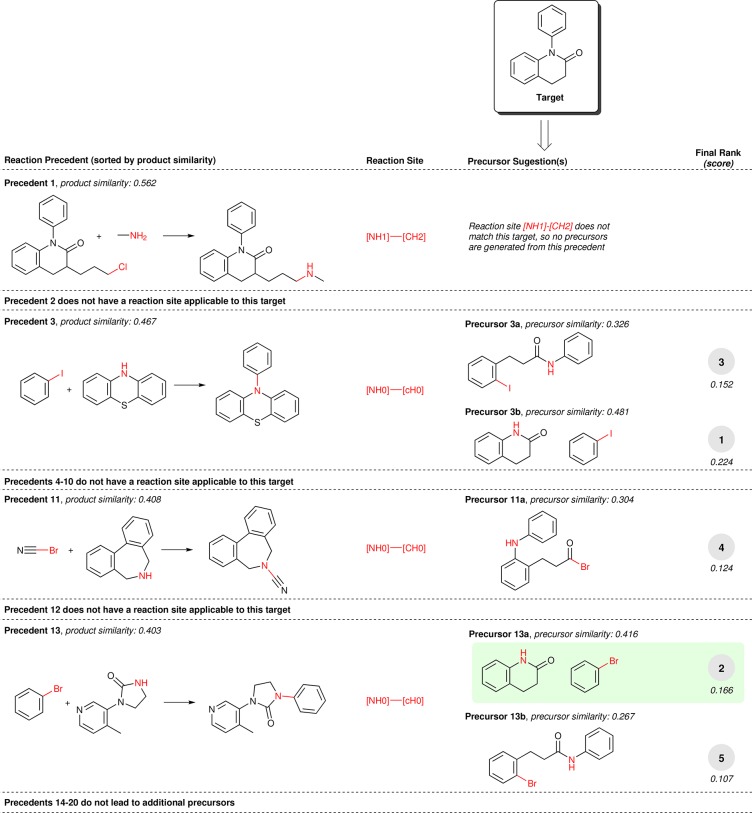

An example prediction of a retrosynthetic heteroatom alkylation/arylation reaction is displayed in Figure 2. The recorded precursors (highlighted in green) are recovered and predicted with rank 2; however, all of the top five precursor suggestions are chemically reasonable. Of particular note is reaction precedent 11, which is recalled from the knowledge base due to a high product similarity but is disfavored when considering the precursor similarity, as the precedent’s bromonitrile is highly dissimilar to the proposed acid bromide. Precedent reactions 3 and 13 both lead to multiple precursor suggestions, which are then differentiated by their disparate reactant similarity scores.

Figure 2.

Example prediction of retrosynthetic heteroatom alkylation/arylation reactions for 1-phenyl-3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-one. After recalling up to 20 reaction precedents in order of decreasing product similarity, the precedent reaction site (highlighted in red and displayed as a SMARTS string) is extracted and matched against the target compound. Of the precedent reactions with the most similar products, not all involve a reaction site that matches the target compound and thus not all produce candidate precursors. Aside from the first reaction, precedents with inapplicable reaction sites are not shown for brevity. The recorded reactants for this target compound (highlighted inside a green box) are recovered and predicted with rank 2; however, all of the top five precursor suggestions are chemically reasonable. Similarity scores are shown using Morgan2noFeat and Tanimoto (see the section on Similarity Calculation).

Similarity Calculation

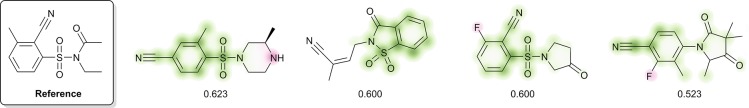

An example of quantitative similarity scores is shown in Figure 3. The reference compound appears in the test data set, and the four other compounds appear as products in the training data set. Scores can range from 1.0 (exact match) to 0.0 (absolutely no commonality) and reflect the extent to which a pair of molecules contains overlapping substructures of various sizes. The benzenesulfonamide motif in the first three compounds results in a high degree of similarity, while the similarity of the fourth compound is primarily due to benzonitrile. The presence of the second piperazine nitrogen in the first compound and the fluorine in the third and fourth compounds decreases their corresponding similarity scores, as these functionalities are not found in the reference molecule.

Figure 3.

Example similarity score calculation using Morgan2Feat fingerprints and the Tanimoto metric. Colors indicate atom-level contributions to the overall similarity (green: increases similarity score, red: decreases similarity score, uncolored: has no effect).

Molecular similarity plays a key role in the selection of reaction precedents and ranking of candidate precursors. Beyond its use for information retrieval, molecular similarity also provides an indication of the presence or absence of functional groups in the target compound as compared to a precedent reaction product. The presence of functional groups that do not appear in the precedent may lead to a competing reaction channel—this will lead to a measurable decrease in molecular similarity. The absence of functional groups that do appear in the precedent may indicate that some enabling context or activation is absent—this also leads to a decrease in similarity. We recognize that the implicit detection of functional group conflicts using this similarity approach is not as robust as other reaction prediction methods,14 but is very attractive due to its speed and simplicity.

Quantifying molecular similarity on the basis of two-dimensional (2D) structure generally requires a fingerprinting technique (to represent a molecule as a vector) and a similarity metric (to compare the two vectors of two molecules).33 There are a number of studies examining different approaches to fingerprinting,34−38 including learned fingerprints using graph neural networks,39−42 and to calculating molecular similarity.43−50 This study was not intended to exhaustively explore these different metrics, but rather demonstrate the proof of concept using a few common implementations.

We focus our evaluation on Morgan circular fingerprints36 as implemented in RDKit.51 A circular fingerprint is molecular representation obtained through an enumeration of submolecular neighborhoods. Initially, atoms are encoded by an integer identifier (a hashed encoding of simple structural properties like atomic number). Neighborhoods of larger sizes are iteratively assigned their own numerical identifiers based on their constituent atoms and bonds. The “radius” of a circular fingerprint refers to the size of the largest neighborhood surrounding each atom that is considered during enumeration. The combination of all unique identifiers comprises the fingerprint, which is often folded into a binary vector of fixed length by converting integer identifiers into indeces of the vector. We refer the reader to Rogers and Hahn36 for a thorough explanation of extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs), which the RDKit implementation of Morgan fingerprints aims to replicate. Four similar fingerprinting techniques were attempted:

Morgan2noFeat, Morgan fingerprints of radius 2 without features,

Morgan3noFeat, Morgan fingerprints of radius 3 without features,

Morgan2Feat, Morgan fingerprints of radius 2 with features, and

Morgan3Feat, Morgan fingerprints of radius 3 with features.

Fingerprinting “with features” refers to the inclusion of information in the initial atom encoding beyond atomic identity to, for example, take into consideration the similarity between different halogens; these are documented in RDKit and are based on the work of Gobbi and Poppinger.52 Similarity scores were calculated without explicitly folding the fingerprint down to a fixed length.

We also evaluate several similarity metrics. The Dice similarity,53 shown in eq 1, quantifies the similarity between two fingerprint vectors x and y by calculating the ratio between the prevalence of overlapping substructures (as measured by nonzero values of xiyi for each vector index i) and the number of distinct substructures observed in each (as measured by the summation over xi2 and yi for each fingerprint separately). The Tanimoto metric,54 shown in eq 2, instead normalizes the prevalence of overlapping substructures (in x and y) by the total number of unique substructures (in x or y). The Tversky similarity55 (eq 3) is a generalization of the Tanimoto similarity that is parametrized by α and β to enable an asymmetrically weighted normalization.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

We choose to test four similarity metrics:

Dice, the Dice similarity,

Tanimoto, the Tanimoto similarity,

TverskyA, the Tversky similarity with α = 1.5 and β = 1.0,

TverskyB, the Tversky similarity with α = 1.0 and β = 1.5.

Qualitatively, within the context of our approach, α and β in the Tversky similarity metric can be thought of as punishing potential reactivity conflicts (groups present in x but not y) and punishing missing molecular context (groups present in y but not x), respectively.

Evaluation Procedure

There is rarely a single correct answer in retrosynthesis, but rather disconnections that are considered productive, yielding precursors that are more synthetically accessible, and those that are unproductive. Proposed reactions should have a high likelihood of success in the forward direction14 and fit into a broader synthesis plan connecting back to buyable reactants with an acceptably high overall yield. There have been many attempts to quantify synthetic accessibility, primarily involving heuristic scoring functions trained on subjective expert ratings.56 Here, we use a success criterion that enables a more objective evaluation: that when given the products of reactions in the United States patent literature, the program recovers and ranks highly the recorded reactants without having seen that reaction previously.

We use the open source ca. 50k reaction data set previously used by Liu et al.21 for the same task of one-step retrosynthesis prediction. This data set was derived from a larger collection from the U.S. patent literature;57 the reactions of this particular subset have been classified by Schneider et al.58 into 10 reaction classes. These are described in Table 1. We follow the same data cleaning procedure as Liu et al., whereby examples with multiple products are split into multiple distinct examples. Products with a SMILES length less than five characters (e.g., byproduct salts) are discarded. Also following Liu et al., we use an 80%/10%/10% training/validation/testing split; the ca. 40 000 training reactions comprise our knowledge base. The full data set with the fixed split is available in the Supporting Information; limitations of this data set are discussed later.

Table 1. Descriptions of Each of the 10 Classes and the Fraction of the ca. 50k Reactions They Represent, Adapted from Schneider et al.58a.

| class | description | fraction of data set (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | heteroatom alkylation and arylation | 30.3 |

| 2 | acylation and related processes | 23.8 |

| 3 | C–C bond formation | 11.3 |

| 4 | heterocycle formation | 1.8 |

| 5 | protections | 1.3 |

| 6 | deprotections | 16.5 |

| 7 | reductions | 9.2 |

| 8 | oxidations | 1.6 |

| 9 | functional group interconversion (FGI) | 3.7 |

| 10 | functional group addition (FGA) | 0.5 |

These were randomly sampled from the patent literature and should approximate the true distribution of reaction types reported in the full USPTO literature.

In Liu et al.’s study, evaluation was performed within each class as if the reaction class of the intended transformation was known a priori. This is useful for cases when a chemist knows what type of reaction step they would like to perform. However, for general retrosynthesis planning, a proposed step can come from any reaction class. We evaluate our approach using both the former approach—to enable comparison—and the latter—as a more realistic formulation of the prediction task. Unfortunately, no direct comparison can be made to the proposed method of Segler and Waller16 due to their lack of open-source code and use of commercial data sets. Performance is quantified using the top-n accuracy for n = {1, 3, 5, 10, 20, 50}, defined as the fraction of examples where the recorded precursors are suggested by the program with rank ≤ n. Atom-mapping is excluded from this comparison, but we do require the chirality of proposed precursors to exactly match that of recorded precursors.

All scripts were written in Python 2.7 using the open source RDKit.51 We have written an additional package to improve handling of stereochemistry when simulating reactions. Details are available in the Supporting Information.

Results

One-Step Evaluation

Each combination of similarity metric and fingerprint was tested on the validation set using the training set as the knowledge base. The aggregated accuracies across all classes are shown in Figure S1 for the case of known reaction class; the accuracies when the reaction class is excluded from consideration are shown in Figure S2. We find that model performance is relatively insensitive to the choice of fingerprint and similarity metric, demonstrating that our approach is robust to changes in how similarity is quantified. From the result of this validation study, we select the Morgan2Feat fingerprint and Tanimoto similarity for evaluation on the test set.

Quantitative model performance is shown in Table 2 when the reaction class is known in advance; details of the top-n accuracy within each class are reported in Table S1. Model performance aggregated across all classes is shown in Table 3 in addition to a second evaluation when the reaction class is not provided to the model. When making predictions within a specific reaction class, the top recommendation by the program exactly matches the reactants used in the recorded reaction 52.9% of the time. The recorded reactants are found within the top 3, top 5, and top 10 suggestions 73.8%, 81.2%, and 88.1% of the time, respectively. Without prior knowledge of the reaction class, recorded reactants are found in the top 10 suggestions for 74.1% of test cases.

Table 2. Model Top-10 Accuracy within Each Class When the Reaction Class Is Known a Priori.

Table 3. Model Performance Aggregated Across All Classes.

| top-n accuracy (%), n = |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| model | 1 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 50 |

| Liu et al. baseline21 | 35.4 | 52.3 | 59.1 | 65.1 | 68.6 | 69.5 |

| Liu et al. seq2seq(21) | 37.4 | 52.4 | 57.0 | 61.7 | 65.9 | 70.7 |

| similarity (this work) | 52.9 | 73.8 | 81.2 | 88.1 | 91.8 | 92.9 |

| similarity (this work)a | 37.3 | 54.7 | 63.3 | 74.1 | 82.0 | 85.3 |

Denotes that reaction class information was not provided to the model, which represents a much harder prediction task.

The similarity-based model outperforms the baseline and seq2seq models of Liu et al. by a large margin in every class. In particular, we see a tremendous improvement in classes 5 and 6 over the baseline approach (retro protections and retro deprotections); this is a result of our fully specifying leaving groups when extracting and applying templates from precedent reactions. Naively generalizing an ester deprotection reaction might result in a forward synthetic template allowing any alkyl side chain (SMARTS: [C]), which effectively prevents the retrosynthetic template from suggesting any ester other than the methyl ester. Our focused template application strategy suggests specific protecting groups by preserving the full leaving group functionalities found in precedent reactants. Using a proper template extraction strategy overcomes the “maximum possible test accuracy” of 69.5% cited by Liu et al. for the template-based baseline model.

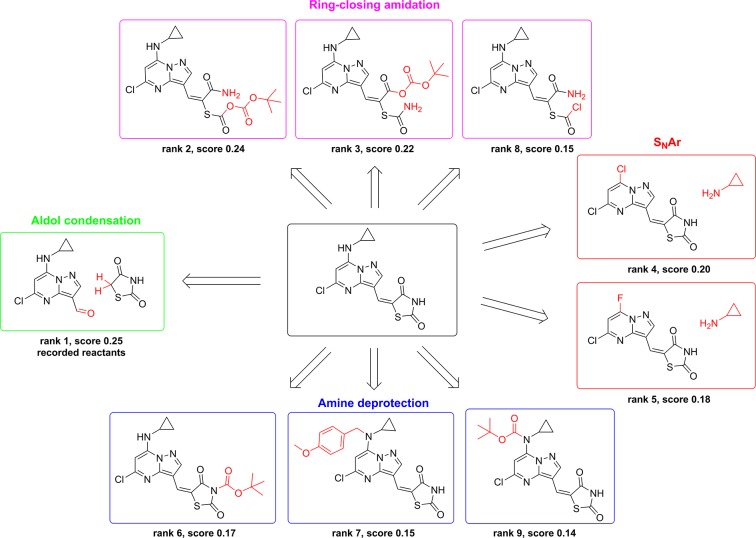

The top nine retrosynthetic predictions for an exemplary compound found in the test set is shown in Figure 4. The highest ranked suggestion from the model is an aldol condensation to bring together the pyrazolopyrimidine and the thiazolidinedione ring systems, which exactly matches what is recorded for this product. The other recommendations are (1) to form the thiazolidinedione through various ring-closing amidation reactions, (2) to install the cyclopropylamino functionality using an SNAr reaction with either the chloro or fluoro substrate, and (3) to deprotect either of the two amines that appear as secondary amines in the target compound. The diversity of these recommendations highlights the power of using the collective knowledge contained in a reaction database to identify strategic retrosynthetic steps that might otherwise be overlooked, particularly by a less experienced chemist. Several additional example predictions are shown in Figures S3 to S18.

Figure 4.

Example retrosynthetic predictions when pooling all reaction classes. The model successfully proposes the recorded reactants with rank 1, corresponding to an aldol condensation. Other suggestions among the top nine include three ring-closing amidations to build the five-membered ring, two SNAr reactions to install cyclopropamine, and three amine deprotections.

Application to Multi-Step Planning

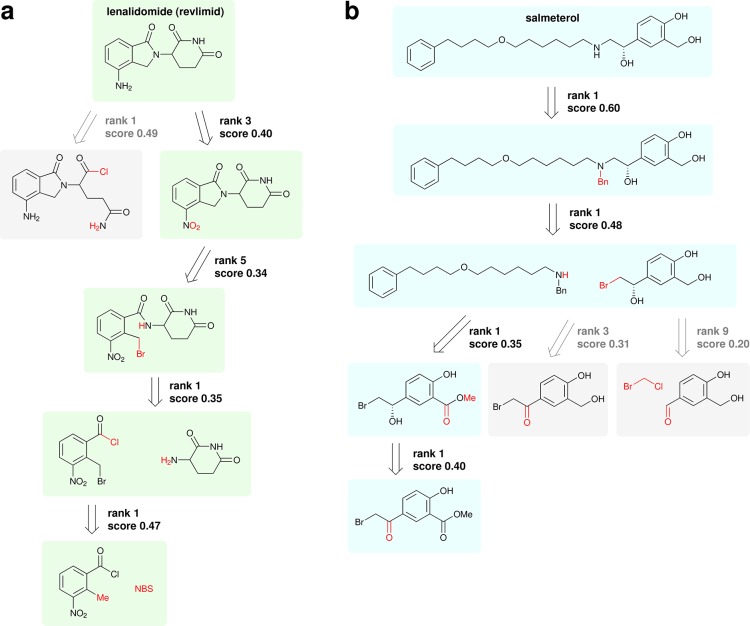

This one-step strategy is easily extended to full pathway design by recursive suggestion of retrosynthetic disconnections. Lenalidomide and salmeterol serve as two model compounds of significant medicinal importance59 that can be synthesized using common chemistries we would expect to exist in our small knowledge base of 40k reactions. Example pathways for each are shown in Figure 5. Note that none of these compounds appears as a product in the knowledge base from which suggestions are made.

Figure 5.

Multistep synthesis plans. Routes are constructed by recursively applying the one-step retrosynthetic methodology to (a) lenalidomide and (b) salmeterol. The suggested disconnections are consistent with published pathways, highlighted with green and blue backgrounds for lendalidomide and salmeterol, respectively.60−62 Slight differences are described in the main text.

The first suggestion for lenalidomide (Figure 5a) is a retro amidation ring opening. Following closely at rank 3 is a nitro reduction, consistent with published literature pathways.60,61 The subsequent retro alkylation to open the five-membered ring is the next step in both literature pathways, although one begins from the nitrophthalic anhydride,60 and the other uses the methyl ester, rather than the acid chloride.61 The latter reference begins with the bromination by N-bromosuccinimide (NBS), precisely as suggested.

The retrosynthesis for salmeterol (Figure 5b) is perhaps more interesting due to the presence of a chiral center. Following only the rank 1 suggestions, the similarity-based approach suggests a benzyl deprotection, preceded by an alkylation, preceded by a reduction of a methyl ester to an alcohol, preceded by an asymmetric ketone reduction. This exactly matches the published synthesis62 except for the order of the alkylation and reduction steps and the choice of amine protecting group. A notable alternate albeit low-ranked suggestion from our approach is to introduce the chirality by means of an enantioselective organometallic addition of bromochloromethane to the benzaldehyde, although this would likely present a lack of selectivity in practice.

The success of the approach in finding viable synthetic pathways is particularly impressive when considering that we have not defined any explicit retrosynthetic strategy. Computer-assisted retrosynthesis typically involves some high-level strategy to help guide the search toward simpler, buyable chemicals (e.g., favoring smaller precursors), just as chemists manually identify disconnections to simplify compounds.5 In this program, the goal is to mimic the implicit strategy contained within the reactions in a knowledge base. In other words, the tendency of the program to lead to smaller, simpler precursors is solely due to that same tendency being present in the data. Forgoing an explicit search heuristic allows the program to rely solely on analogy to precedent reactions and—in the case of salmeterol—recover a known pathway following the top suggestions at each step. With a guiding heuristic explicitly favoring smaller molecules, the first proposed step would have been a retro alkylation without the retro deprotection first, which would have led to nonselective overalkylation.

Discussion

Limitations of the Approach

By design, the similarity-based approach is meant to apply existing reaction knowledge to novel substrates. This strategy inherently disfavors making creative disconnections. Retrosynthetic suggestions do not offer major insights beyond what could be achieved by a trained synthetic chemist familiar with the types of reactions found in the knowledge base. We emphasize that this is an intentional result of using an empirical, data-driven approach to automated retrosynthesis. The suggestions made by a model extrapolating outside of its training data carry a significant amount of uncertainty; as described, the model is effectively restricted to operate within the scope of known chemistry.

While the goal of this study was to recover the true precursors used in reactions from the patent literature, this method can be trivially adapted to encourage pathway diversity. Rather than retrieving precedents and ranking candidate precursors deterministically, one might intentionally add a random value to the calculated similarity scores to introduce stochasticity and sample more dissimilar precedents. The absolute score values used to determine the rankings of suggestions are included with the various examples in Figures S3–S18. A small score perturbation would lead to more creative disconnections but—as alluded to earlier—introduces more uncertainty into the quality of recommendations.

There are obviously many additional considerations in synthetic route planning, not limited to cost, process complexity, reaction yield, workup difficulty, safety, and toxicity of intermediates. Because this information is either incomplete or unavailable in public databases, we focus on the disconnections themselves, which makes this methodology more suitable for research-scale discovery applications. We expect that additional considerations could be incorporated by weighting the scores assigned to precedent reactions by an additional “process suitability” function to balance the similarity metric with these other considerations. This method could also be restricted to use a particular subset of available reaction data to provide domain-specific suggestions, e.g., only from process chemistry journals.

Limitations of the Data set

While this methodology is easily applied to other data sources (e.g., Reaxys31 or an electronic lab notebook), use of unpublishable data would prevent future performance comparisons; for this reason, we have made use of open source data originating from the patent literature. This data set is well-suited for quantitative performance comparisons but does present quality concerns, as patented syntheses may not have been validated experimentally or may have had a very low yield. This concern, however, does not negate the fact that these examples reflect an implicit retrosynthetic strategy (with regard both to the types of reactions commonly employed and to when certain disconnections are applied on the basis of present or absent structural motifs) contained within the patent literature.

Quality of Suggestions

There are certain patterns that chemists follow when performing a retrosynthetic analysis, including consideration of reaction classes, viable synthons, and hierarchies of functional group reactivities. On the basis of the quantitative performance on the USPTO data set, it is clear that the model is successful in proposing retrosynthetic disconnections that match actual patented syntheses without the need for any explicit chemical knowledge. When making suggestions within a specific reaction class, the model makes a perfect recommendation 52.9% of the time; even without specifying the reaction class, perfect recommendations are made 37.3% of the time. When 10 disconnections are proposed, the success rates increase to 88.1% and 74.1%, respectively. The approach is successful even when extended to pathway planning for high-value, medicinally relevant drug compounds.

However, some suggestions, particularly lower-ranked or lower-scored ones, may not be synthetically viable when attempted experimentally. The use of similarity for prioritizing suggestions partially mitigates this issue of “false positive” recommendations while still generating potential synthetic routes rapidly; to generate more conservative recommendations with a more guaranteed rate of success, slower methods can be applied for forward reaction prediction.14

Conclusion

We have demonstrated an approach for automated retrosynthesis based on analogy to known reactions. Molecular similarity, both between products and between reactants, is a sufficient metric for determining relevant precedents and applying the corresponding highly local retrosynthetic transform. Because a relatively small number of templates are applied when they are thought to be relevant, it is not necessary to define heuristics for their extraction, nor is the speed limited by the computational bottleneck of full template library application. Calculating a target molecule’s similarity to a set of known products is an “embarrassingly parallel”, computationally inexpensive problem and there exist numerous means of doing so. By design, suggested precursors are necessarily linked to specific precedents as supporting evidence. And although this data set does not contain contextual information, using one that does would further enrich suggestions by including information about reagents, catalysts, solvents, and temperatures of precedent reactions to assist in experimental validation.

We describe our workflow in full detail and open source our code to enable use of other data sets as knowledge bases, for example, in-house electronic lab notebook data.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the DARPA Make-It program under Contract ARO W911NF-16-2-0023. C.W.C. received additional funding from the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. 1122374.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00355.

Recapitulation of approach, validation set performance, and link to github repository with code and data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

All code used to produce the reported results can be found online at https://github.com/connorcoley/retrosim. All data used are freely available and can be found via the same URL.

Supplementary Material

References

- Robinson R. LXIII – A synthesis of tropinone. J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 1917, 111, 762–768. 10.1039/CT9171100762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corey E. J. The logic of chemical synthesis: multistep synthesis of complex carbogenic molecules (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 455–465. 10.1002/anie.199104553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger J.; Ihlenfeldt W.. Software Development in Chemistry 4; Springer, 1990; pp 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ott M. A.; Noordik J. H. Computer tools for reaction retrieval and synthesis planning in organic chemistry. A brief review of their history, methods, and programs. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1992, 111, 239–246. 10.1002/recl.19921110601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Todd M. H. Computer-aided organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 247–266. 10.1039/b104620a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A.; Johnson A. P.; Law J.; Mirzazadeh M.; Ravitz O.; Simon A. Computer-aided synthesis design: 40 years on. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 79–107. 10.1002/wcms.61. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warr W. A. A. Short Review of Chemical Reaction Database Systems, Computer-Aided Synthesis Design, Reaction Prediction and Synthetic Feasibility. Mol. Inf. 2014, 33, 469–476. 10.1002/minf.201400052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey E. J.; Long A. K.; Rubenstein S. D. Computer-assisted analysis in organic synthesis. Science 1985, 228, 408–419. 10.1126/science.3838594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelernter H.; Rose J. R.; Chen C. Building and refining a knowledge base for synthetic organic chemistry via the methodology of inductive and deductive machine learning. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 1990, 30, 492–504. 10.1021/ci00068a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh H.; Funatsu K. SOPHIA, a knowledge base-guided reaction prediction system-utilization of a knowledge base derived from a reaction database. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 1995, 35, 34–44. 10.1021/ci00023a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh K.; Funatsu K. A novel approach to retrosynthetic analysis using knowledge bases derived from reaction databases. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1999, 39, 316–325. 10.1021/ci980147y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Law J.; Zsoldos Z.; Simon A.; Reid D.; Liu Y.; Khew S. Y.; Johnson A. P.; Major S.; Wade R. A.; Ando H. Y. Route Designer: A Retrosynthetic Analysis Tool Utilizing Automated Retrosynthetic Rule Generation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 593–602. 10.1021/ci800228y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogevig A.; Federsel H.-J.; Huerta F.; Hutchings M. G.; Kraut H.; Langer T.; Low P.; Oppawsky C.; Rein T.; Saller H. Route Design in the 21st Century: The ICSYNTH Software Tool as an Idea Generator for Synthesis Prediction. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 357–368. 10.1021/op500373e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coley C. W.; Barzilay R.; Jaakkola T. S.; Green W. H.; Jensen K. F. Prediction of Organic Reaction Outcomes Using Machine Learning. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 434–443. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ C. D.; Zentgraf M.; Kriegl J. M. Mining Electronic Laboratory Notebooks: Analysis, Retrosynthesis, and Reaction Based Enumeration. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 1745–1756. 10.1021/ci300116p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segler M. H. S.; Waller M. P. Neural-Symbolic Machine Learning for Retrosynthesis and Reaction Prediction. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 5966–5971. 10.1002/chem.201605499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segler M.; Preuß M.; Waller M. P.. Towards “AlphaChem”: Chemical Synthesis Planning with Tree Search and Deep Neural Network Policies. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.00020, 2017.

- Fick R.; Ihlenfeldt W.-D.; Gasteiger J. Computer-assisted design of syntheses for heterocyclic compounds. Heterocycles 1995, 40, 993–1007. 10.3987/COM-94-S100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger J.; Ihlenfeldt W.; Röse P. A collection of computer methods for synthesis design and reaction prediction. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1992, 111, 270–290. 10.1002/recl.19921110605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szymkuc S.; Gajewska E. P.; Klucznik T.; Molga K.; Dittwald P.; Startek M.; Bajczyk M.; Grzybowski B. A. Computer-Assisted Synthetic Planning: The End of the Beginning. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 5904–5937. 10.1002/anie.201506101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Ramsundar B.; Kawthekar P.; Shi J.; Gomes J.; Luu Nguyen Q.; Ho S.; Sloane J.; Wender P.; Pande V. Retrosynthetic Reaction Prediction Using Neural Sequence-to-Sequence Models. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 1103–1113. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L.; Laird E. R.; Gushurst A. J.; Fleischer J. M.; Gothe S. A.; Helson H. E.; Paderes G. D.; Sinclair S. CAMEO: a program for the logical prediction of the products of organic reactions. Pure Appl. Chem. 1990, 62, 1921–1932. 10.1351/pac199062101921. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J. N.; Duvenaud D.; Aspuru-Guzik A. Neural networks for the prediction of organic chemistry reactions. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 725–732. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segler M. H.; Waller M. P. Modelling chemical reasoning to predict and invent reactions. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 6118–6128. 10.1002/chem.201604556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam J.; Kim J.. Linking the Neural Machine Translation and the Prediction of Organic Chemistry Reactions. arXiv:1612.09529 [cs] 2016, arXiv: 1612.09529. [Google Scholar]

- Weininger D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 1988, 28, 31–36. 10.1021/ci00057a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cadeddu A.; Wylie E. K.; Jurczak J.; Wampler-Doty M.; Grzybowski B. A. Organic Chemistry as a Language and the Implications of Chemical Linguistics for Structural and Retrosynthetic Analyses. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 8108–8112. 10.1002/anie.201403708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot J. R. Molecular Complexity and Retrosynthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 6968–6971. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b00714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey E. J. General methods for the construction of complex molecules. Pure Appl. Chem. 1967, 14, 19–38. 10.1016/B978-0-08-020741-4.50004-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sayle R.1st-class SMARTS patterns. EuroMUG 97, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson A. J.; Swienty-Busch J.; Géoui T.; Evans D. The Future of the History of Chemical Information. ACS Symp. Ser. 2014, 1164, 127–148. 10.1021/bk-2014-1164.ch008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley D. D.Information Retrieval: SciFinder and SciFinder Scholar; John Wiley & Sons, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Willett P.Chemoinformatics and Computational Chemical Biology; Springer, 2010; pp 133–158. [Google Scholar]

- Baldi P.; Benz R. W.; Hirschberg D. S.; Swamidass S. J. Lossless Compression of Chemical Fingerprints Using Integer Entropy Codes Improves Storage and Retrieval. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 2098–2109. 10.1021/ci700200n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J.; Dixon S. L.; Lowrie J. F.; Sherman W. Analysis and comparison of 2D fingerprints: Insights into database screening performance using eight fingerprint methods. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2010, 29, 157–170. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers D.; Hahn M. Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 742–754. 10.1021/ci100050t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riniker S.; Landrum G. A. Open-source platform to benchmark fingerprints for ligand-based virtual screening. J. Cheminf. 2013, 5, 26. 10.1186/1758-2946-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereto-Massague A.; Ojeda M. J.; Valls C.; Mulero M.; Garcia-Vallve S.; Pujadas G. Molecular fingerprint similarity search in virtual screening. Methods 2015, 71, 58–63. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer J.; Schoenholz S. S.; Riley P. F.; Vinyals O.; Dahl G. E.. Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.01212 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Duvenaud D. K.; Maclaurin D.; Iparraguirre J.; Bombarell R.; Hirzel T.; Aspuru-Guzik A.; Adams R. P. Convolutional networks on graphs for learning molecular fingerprints. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2015, 2224–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Kearnes S.; McCloskey K.; Berndl M.; Pande V.; Riley P. Molecular graph convolutions: moving beyond fingerprints. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2016, 30, 595–608. 10.1007/s10822-016-9938-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley C. W.; Barzilay R.; Green W. H.; Jaakkola T. S.; Jensen K. F. Convolutional Embedding of Attributed Molecular Graphs for Physical Property Prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 1757–1772. 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. A.; Maggiora G. M.. Concepts and Applications of Molecular Similarity; Wiley, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger J.; Ihlenfeldt W. D.; Fick R.; Rose J. R. Similarity concepts for the planning of organic reactions and syntheses. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 1992, 32, 700–712. 10.1021/ci00010a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rarey M.; Dixon J. S. Feature trees: A new molecular similarity measure based on tree matching. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 1998, 12, 471–490. 10.1023/A:1008068904628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butina D. Unsupervised Data Base Clustering Based on Daylight’s Fingerprint and Tanimoto Similarity: A Fast and Automated Way To Cluster Small and Large Data Sets. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1999, 39, 747–750. 10.1021/ci9803381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nalewajski R. F.; Parr R. G. Information theory, atoms in molecules, and molecular similarity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97, 8879–8882. 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A.; Glen R. C. Molecular similarity: a key technique in molecular informatics. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 3204–3218. 10.1039/b409813g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi P.; Nasr R. When is chemical similarity significant? The statistical distribution of chemical similarity scores and its extreme values. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1205–1222. 10.1021/ci100010v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajusz D.; Racz A.; Heberger K. Why is Tanimoto index an appropriate choice for fingerprint-based similarity calculations?. J. Cheminf. 2015, 7, 20. 10.1186/s13321-015-0069-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrum G.RDKit: Open-source cheminformatics. http://www.rdkit.org, Accessed on 2016-11-20.

- Gobbi A.; Poppinger D. Genetic optimization of combinatorial libraries. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1998, 61, 47–54. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dice L. R. Measures of the Amount of Ecologic Association Between Species. Ecology 1945, 26, 297–302. 10.2307/1932409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto T. T.An Elementary Mathematical Theory of Classification and Prediction; International Business Machines Corporation, 1958; Google-Books-ID: yp34HAAACAAJ. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A. Features of similarity. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 327–352. 10.1037/0033-295X.84.4.327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan R. P.; Zorn N.; Sherer E. C.; Campeau L.-C.; Chang C.; Cumming J.; Maddess M. L.; Nantermet P. G.; Sinz C. J.; O'Shea P. D. Modeling a crowdsourced definition of molecular complexity. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 1604–1616. 10.1021/ci5001778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe D. M.Extraction of chemical structures and reactions from the literature. Thesis, University of Cambridge, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider N.; Stiefl N.; Landrum G. A. Whatś What: The (Nearly) Definitive Guide to Reaction Role Assignment. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016, 56, 2336–2346. 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Top Drugs by Sales Revenue in 2015: Who Sold The Biggest Blockbuster Drugs? https://www.pharmacompass.com/radio-compass-blog/top-drugs-by-sales-revenue-in-2015-who-sold-the-biggest-blockbuster-drugs, Accessed on 2017-07-26.

- Muller G. W.; Chen R.; Huang S.-Y.; Corral L. G.; Wong L. M.; Patterson R. T.; Chen Y.; Kaplan G.; Stirling D. I. Amino-substituted thalidomide analogs: Potent inhibitors of TNF-α production. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 1625–1630. 10.1016/S0960-894X(99)00250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponomaryov Y.; Krasikova V.; Lebedev A.; Chernyak D.; Varacheva L.; Chernobroviy A. Scalable and green process for the synthesis of anticancer drug lenalidomide. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2015, 51, 133–138. 10.1007/s10593-015-1670-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hett R.; Stare R.; Helquist P. Enantioselective synthesis of salmeterol via asymmetric borane reduction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 9375–9378. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)78546-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.