Abstract

Premise of the study:

Constructing complete, accurate plant DNA barcode reference libraries can be logistically challenging for large-scale floras. Here we demonstrate the promise and challenges of using herbarium collections for building a DNA barcode reference library for the vascular plant flora of Canada.

Methods:

Our study examined 20,816 specimens representing 5076 of 5190 vascular plant species in Canada (98%). For 98% of the specimens, at least one of the DNA barcode regions was recovered from the plastid loci rbcL and matK and from the nuclear ITS2 region. We used beta regression to quantify the effects of age, type of preservation, and taxonomic affiliation (family) on DNA sequence recovery.

Results:

Specimen age and method of preservation had significant effects on sequence recovery for all markers, but influenced some families more (e.g., Boraginaceae) than others (e.g., Asteraceae).

Discussion:

Our DNA barcode library represents an unparalleled resource for metagenomic and ecological genetic research working on temperate and arctic biomes. An observed decline in sequence recovery with specimen age may be associated with poor primer matches, intragenomic variation (for ITS2), or inhibitory secondary compounds in some taxa.

Keywords: Canadian vascular flora, DNA barcode reference library, herbarium, ITS2, matK, rbcL

There is a need for high-quality DNA barcode reference libraries to facilitate the routine identification of plants and to support rapidly emerging metagenomic studies in the regulation of plant-based foods and food supplements (Ivanova et al., 2016; Prosser and Hebert, 2017), ecological forensics (Kartzinel et al., 2015; Richardson et al., 2015; Erickson et al., 2017), environmental DNA detection (Kraaijeveld et al., 2015; Scriver et al., 2015; Bell et al., 2017), and ancient DNA analysis (Birks and Birks, 2016). The generation of reliable DNA-based identifications requires a comprehensive, accurate reference DNA barcode library based on associated voucher specimens (Hebert et al., 2003). A well-curated local reference DNA barcode library can increase the precision and accuracy of the species assignment for a query sequence (Landi et al., 2014). In some cases, results can be improved when the reference library reflects broad geographical sampling (Bergsten et al., 2012). A unique challenge for plants is that plastid and nuclear DNA barcodes yield lower species resolution compared to the mitochondrial and nuclear barcodes used for animals and fungi (Naciri and Linder, 2015; Hollingsworth et al., 2016). However, building a geographically circumscribed reference library can improve the effectiveness of plant DNA barcoding (Clerc-Blain et al., 2010; Burgess et al., 2011; de Vere et al., 2012; Parmentier et al., 2013; Elliott and Davies, 2014; Erickson et al., 2014). Braukmann et al. (2017a) recently showed that the discriminatory power of the most commonly used plant DNA barcodes (rbcL, matK, and ITS2) for the Canadian vascular plant species varies depending on the method of analysis (BLAST vs. Mothur) and biogeographic region (e.g., Canadian arctic vs. woodland). Considering individual markers, the highest resolution was provided by matK (∼81%), followed by ITS2 (∼72%) and rbcL (∼44%). All three DNA barcodes performed strongly in assigning taxa to the correct genus (91–98%).

Obtaining a geographically representative sample of plant species from a large and diverse area such as Canada is a logistical challenge, but use of the rich collections housed in herbaria, which document plant diversity in time and space, can potentially overcome this barrier. Herbarium vouchers include detailed collection data and identifications that in many cases are annotated by experts. Importantly, voucher specimens are available for re-examination. The use of herbarium collections can significantly reduce costs and project time in comparison to making fresh collections for large-scale floras. Most North American herbaria include relatively few recently collected specimens (Deng, 2015), potentially limiting sequence recovery due to DNA degradation (Staats et al., 2011). Advances in high-throughput sequencing using approaches not based on PCR may reduce this problem, but costs are currently too high to sequence large numbers of specimens (Staats et al., 2013; Coissac et al., 2016; Bakker et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017a). Although several studies have demonstrated the utility of material sourced from herbaria for constructing DNA barcode libraries (de Vere et al., 2012; Kuzmina et al., 2012; Saarela et al., 2013), quantitative analysis of DNA degradation in old herbarium specimens has only been performed using a limited number of specimens and taxa (Staats et al., 2011).

Until recently, the Canadian flora lacked a standardized and comprehensive checklist across both its Nearctic endemics and taxa with Holarctic distributions (Takhtajan, 1986; Thorne, 1993). The latter often possess conflicting taxonomic assignments in North American and Eurasian treatments (Flora of North America Editorial Committee, 1993; Cody, 2000; Aiken et al., 2007; Elven et al., 2011; Klinkenberg, 2013). A further complication is that approximately 22% of the modern Canadian flora comprises species introduced by human activity (Vitousek et al., 1997). The Database of Vascular Plants of Canada (VASCAN) was developed to standardize names for all vascular plant taxa (species, subspecies, and varieties) recorded in Canada, providing an up-to-date checklist of accepted names, synonyms, and distribution status (Brouillet et al., 2010; Desmet and Brouillet, 2013). The checklist is continuously updated based on new findings and recent taxonomic treatments. In addition to using this checklist as a framework for the species included here, we validated taxonomic information associated with all barcoded specimens in collaboration with plant taxonomists.

Here we demonstrate how herbarium material can be exploited as a large-scale resource for creating a reference DNA barcode library for a major vascular plant flora. We supplemented our primarily herbarium-derived DNAs with vouchered field- or garden-collected specimens preserved in silica gel. We assembled a reference library for three plant DNA barcodes: two based on the plastid genes rbcL and matK (CBOL Working Group, 2009), and a third, ITS2, comprising one of the two nuclear internal transcribed ribosomal spacer regions (China Plant BOL Group, 2011). We examined how sequence recovery for these markers depends on specimen age, method of preservation (i.e., herbarium specimens vs. tissue preserved in silica gel), and taxonomic affiliation (i.e., family). These parameters may represent important constraints in employing herbarium specimens in DNA barcoding studies or reference library development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

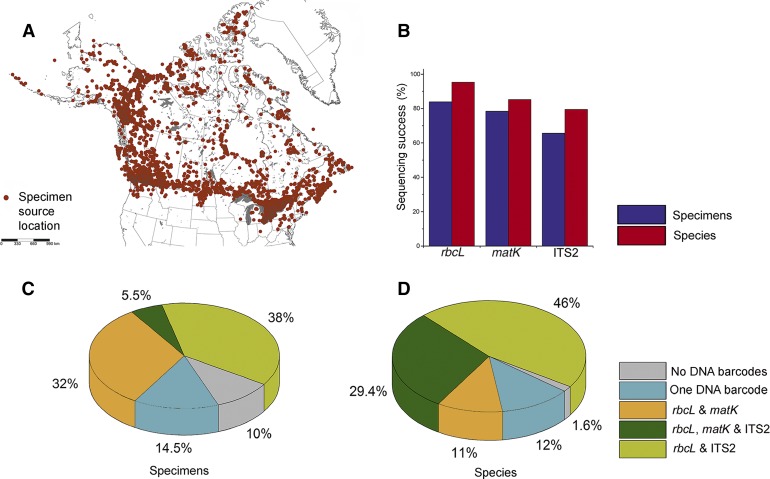

We examined 20,816 specimens from Canada and adjacent regions of the United States (Fig. 1A). This included 13,170 specimens selected from 27 herbaria with priority to the most recently collected representatives for each species (Table 1). The remaining 7660 specimens represent freshly collected material obtained from field trips or botanical gardens in 2006–2013, which were immediately preserved in silica gel. Voucher specimens associated with these silica gel samples were deposited in associated herbaria (Table 1). Taxonomic assignments and geographic information were recorded during field collection or were obtained from herbarium voucher labels. To ensure that the record from each specimen was traceable on Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD), it was associated with the nomenclatural combination provided on the herbarium label (International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories, 2012). This information, along with an image where possible, was uploaded to BOLD (dx.doi.org/10.5883/DS-VASCAN). We redacted geographic data from 252 records representing plant species assessed as endangered or threatened by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), following recommendations made by NatureServe Canada (Amie Enns and Patrick Henry, NatureServe Canada, personal communication).

Fig. 1.

Specimen source location and sequence recovery as proportions of DNA barcodes, specimens, and species analyzed. (A) Specimen source location. (B) DNA barcode recovery for each marker as a percentage of specimens and species analyzed. (C) DNA barcode recovery as a percentage of samples analyzed. (D) DNA barcode recovery as a percentage of total species analyzed.

Table 1.

Herbaria contributing specimens that were analyzed in this study.

| Institution | Index Herbariorum codea | No. of specimens collected from tissue preserved in silica gel | No. of specimens collected from herbarium vouchers | Total no. of specimens |

| Acadia University | ACAD | — | 4 | 4 |

| University of Alaska Museum | ALA | — | 46 | 46 |

| University of Alberta | ALTA | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| B. A. Bennett Herbarium, Yukon Government | BABY | — | 2608 | 2608 |

| Canadian Museum of Nature | CAN | 2057 | 1989 | 4046 |

| University of Colorado, Museum of Natural History | COLO | — | 2 | 2 |

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | DAO | — | 1072 | 1072 |

| Delaware State University | DOV | — | 210 | 210 |

| Aberystwyth University | IBERS | — | 1 | 1 |

| University of Maine | MAINE | — | 5 | 5 |

| University of Michigan | MICH | — | 3 | 3 |

| University of Minnesota | MIN | — | 3 | 3 |

| Minot State University | MISU | 281 | — | 281 |

| The Manitoba Museum | MMMN | — | 74 | 74 |

| Université de Montréal, Herbier Marie-Victorin | MT | 458 | 73 | 531 |

| McGill University, Macdonald Campus | MTMG | 149 | — | 149 |

| University of Guelph | OAC | 3029 | 2508 | 5537 |

| Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre | ONHIC | — | 24 | 24 |

| Université Laval, Herbier Louis-Marie | QFA | — | 8 | 8 |

| Royal Ontario Museum, Green Plant Herbarium | TRT | 192 | 2641 | 2833 |

| University of Toronto at Mississauga | TRTE | — | 14 | 14 |

| University of British Columbia | UBC | 1436 | 1482 | 2918 |

| University of California, Riverside | UCR | — | 1 | 1 |

| University of New Brunswick | UNB | — | 11 | 11 |

| University of Northern British Columbia | UNBC | 33 | — | 33 |

| Smithsonian Institution, United States National Herbarium | US | 18 | — | 18 |

| University of Waterloo | WAT | — | 2 | 2 |

| University of Manitoba | WIN | — | 316 | 316 |

| University of Wisconsin–Madison | WIS | — | 4 | 4 |

| University of Washington | WTU | — | 50 | 50 |

Acronyms for the herbaria are used in accordance with Index Herbariorum (Thiers, 2017).

We used VASCAN (Brouillet et al., 2010; Desmet and Brouillet, 2013) to provide standardized nomenclature, represented as a supplementary field in BOLD (“associated taxonomy”). The complete checklist of 5190 accepted species names of vascular plants reported from Canada includes species categorized as “native” (i.e., that are present as a result of natural processes), “introduced” (taxa established or naturalized as a result of human activity), and “ephemeral” (not established permanently, but recurring in the wild on a near-annual basis). Species of known hybrid origin, defined in literature as nothospecies (McNeill et al., 2012), were not included in the final checklist. The vouchers that were analyzed were associated with 4974 species on the VASCAN checklist. Additionally, our library includes 101 native and alien (including cultivated) species collected from Canada and the adjacent United States not listed in VASCAN (Appendix S1 (13.4KB, xlsx) ). The latter were included in our database following the nomenclature accepted in the Flora of North America for the relevant taxa (Flora of North America Editorial Committee, 1993), or otherwise following accepted names in The Plant List (2013). As a result, we analyzed representatives of 5076 species of vascular plants belonging to 146 of the 416 families and 43 of the 64 orders of angiosperms (Chase et al., 2016), with an additional 23 families and 13 orders of nonflowering land plants also represented (see Smith et al., 2006 for fern classification).

DNA extraction, PCR, and sequencing were performed with semiautomated protocols at the Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding (Ivanova and Grainger, 2006; Ivanova et al., 2008, 2011; Kuzmina and Ivanova, 2011; Fazekas et al., 2012). In brief, 1–5 mg of herbarium or silica gel–dried plant tissue was ground into fine powder using a TissueLyser II (QIAGEN, Germantown, Maryland, USA) at 28 Hz for 60–90 s at room temperature, using the Axygen Mini Tube System (Axygen Scientific, Union City, California, USA) with one 3.17-mm stainless steel bead per tube. Following disruption, cells were lysed with 250–400 µL of 2× cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) buffer incubated at 65°C for 60–90 min. After incubation, 50 µL of lysate from each sample was transferred into 96-well microplates (250 µL, semiskirted; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) using a Liquidator 96 (200 µL; Mettler Toledo, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). DNA was isolated and purified through binding to glass fiber filtration columns (Ivanova et al., 2008) on a Biomek FX Workstation (Beckman Coulter, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). This protocol generated 40-µL long-term storage extracts with DNA concentrations of 20–40 ng/µL, sufficient for PCR amplification of multiple DNA target regions (rbcL, matK, and ITS2) (Kuzmina and Ivanova, 2011; Fazekas et al., 2012). Details on the primers used for PCR and sequencing, as well as PCR conditions, are provided in Appendix S2 (42.8KB, docx) . Initial PCR was performed with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, New Hampshire, USA) using primers matK-xf and matK-MALP, and sequencing was done with the internal forward primer matK-1RKIM-f and matK-MALP. Owing to very low PCR success for species of Boraginaceae, a subset of specimens in this family were subjected to an additional round of DNA purification (Ivanova et al., 2008) with the goal of removing secondary compounds that might inhibit PCR. Amplification of rbcL was attempted on all 20,816 specimens, matK on 9412 specimens, and ITS2 on 13,233 specimens (Appendix S3 (10.5KB, xlsx) ) (differences in sample size reflect fluctuations in funding linked to specific projects, but we made substantial effort to represent all species with at least one sample per marker, where feasible). A subset of 2439 specimens was tested with all three markers. PCR products were diluted in water (Appendix S2 (42.8KB, docx) ) and sequenced on an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) following standard procedures.

Chromatograms were edited with CodonCode Aligner versions 3.7.1–6.0.2 (CodonCode Co., Centerville, Massachusetts, USA). Sequence alignments generated in MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004) were used as a basis for removing primer sequences and to aid the identification of errors in sequence editing (e.g., nucleotide shifts in homopolymer tracts) within rbcL and matK and in the partial sequences for the 5.8S and 26S ribosomal subunit genes that flank ITS2. BLASTN searches (Altschul et al., 1990) were used to identify and remove fungal, algal, and liverwort sequences that were occasionally recovered when the DNA of the target specimen was degraded and/or the match of primers to template DNA was poor. Both rbcL and matK sequences were aligned using the back-translation sequence alignment program, transAlign, to identify sequences with frameshift mutations (Bininda-Emonds, 2005). After filtering out contaminants and correcting editing errors, the sequences were uploaded to BOLD (www.boldsystems.org).

Additional quality control of the DNA barcode data was accomplished by inspecting the correspondence between phylogenies reconstructed with DNA barcodes (rbcL and matK) and the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG) topologies (Kress et al., 2009; Chase et al., 2016). A preliminary neighbor-joining tree for each of these markers was constructed in BOLD (Ratnasingham and Hebert, 2007) to aid the identification of contaminants and errors in sampling, identification, and/or data entry. Cases of potential errors in identification led to reexamination of the specimens, typically in consultation with the curator of the source specimen, before taxonomic information on BOLD was updated. As a noncoding region, ITS2 required a different approach to remove contaminants and paralogous copies prior to data submission; MAFFT was used to generate an initial sequence alignment for all ITS2 sequences (Katoh et al., 2002). A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree for the entire ITS2 data set was constructed in SATé (Liu et al., 2009) using default parameters (aligner: MAFFT; merger: MUSCLE; tree estimator: FASTTREE; model: GTR+G20) to identify and remove erroneous sequences, as described above for matK and rbcL. Our sequence length thresholds for accepting DNA barcodes were 450 bp for rbcL, 500 bp for matK, and 180 bp for ITS2.

The success in recovery of each barcode region was calculated separately (Fig. 1). For this comparison, the effects of uneven sampling were minimized by focusing on data from 25 species-rich families (23 angiosperms, one gymnosperm, one fern) with the most complete sample size for each marker (Appendix S4 (42.8KB, xlsx) ). The three markers (rbcL, matK, and ITS2) for these families are represented by corresponding data sets from 15,173, 7416, and 9404 specimens, respectively. The data sets analyzed for each marker have minor differences in taxonomic composition. The matK data set omits Lamiaceae (small sample size), Pinaceae, and Dryopteridaceae (no amplification), while the ITS2 data set omits Dryopteridaceae (no amplification).

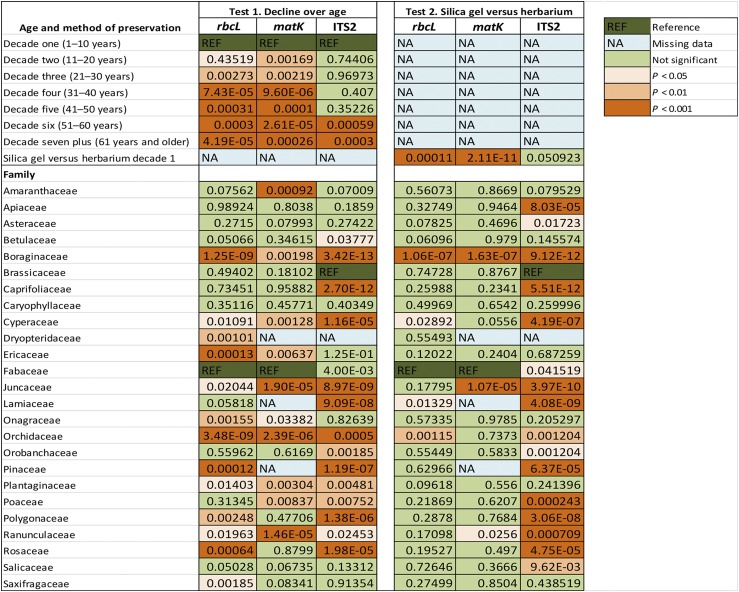

To examine the effects of age and family (taxonomy affiliation) on sequence recovery from herbarium specimens, we used a beta regression analysis for modeling proportions, implemented in R version 3.2.0 (betareg package) (Ferrari and Cribari-Neto, 2004; R Development Core Team, 2008; Cribari-Neto and Zeileis, 2009). A second beta regression compared sequence recovery from specimens preserved in silica gel vs. standard herbarium material. Both tests were performed for each DNA barcode marker separately (Appendix S4 (42.8KB, xlsx) ). Data obtained from herbarium material were sorted by family into seven age groups (decades 1–7, Fig. 2). Sequencing success in specimens from the first (most recent) decade served as a reference to evaluate the decline in sequence recovery with time. For the second test, we compared success from silica gel–preserved material with herbarium specimens of equivalent age (1–10 yr) and performed a beta regression to avoid type I error associated with multiple pairwise tests (25 for each marker). For all tests, a high-performing reference family provided a basis for comparison with other families to identify families with low sequence recovery. The reference families were selected based on consistently high sequence recovery across all age groups and a large sample size (Fabaceae for rbcL and matK; Brassicaceae for ITS2). Families identified as having low or problematic sequence recovery were analyzed for possible primer–template incompatibility by comparing primer sequences to corresponding full-length sequences available on GenBank for each taxon.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of sequence recovery for three DNA barcodes among 25 species-rich families using a beta regression model and reference families (Fabaceae for rbcL and matK, Brassicaceae for ITS2). Test 1: Herbarium specimens in seven different age classes (decade 1: 1–10 yr; decade 2: 11–20 yr; decade 3: 21–30 yr; decade 4: 31–40 yr; decade 5: 41–50 yr; decade 6: 51–60 yr; decade 7 and older: 61 yr and older). Test 2: Silica gel–preserved material vs. herbarium specimens from decade 1. NA = not applicable.

RESULTS

Specimen, species, and family coverage

The sequencing success for each marker was evaluated based on the number of specimens that successfully generated a sequence for a particular marker (Fig. 1B, 1C, and 1D; Appendix S3 (10.5KB, xlsx) ). The values of sequence recovery for rbcL, matK, and ITS2 for all 169 families of vascular plants in Canada are reported in Appendix S5 (2.8MB, pdf) , together with the sample size (number of specimens attempted) for each family.

To identify trends in sequencing success, we grouped families with more than nine specimens into four categories: those with no sequence recovery (0%), low recovery (1–50%), moderate recovery (51–75%), and high recovery (76–100%) (Table 2, Appendix S5 (2.8MB, pdf) ). The proportion of families distributed across the four groups for rbcL was 0.00/0.03/0.20/0.77. For matK and ITS2, these proportions were 0.10/0.08/0.22/0.60 and 0.11/0.21/0.33/0.35, respectively. No family completely failed to generate sequences for rbcL, and low recovery was restricted to two nonangiosperm families (Ophioglossaceae, Selaginellaceae) and three angiosperm families (Boraginaceae, Cistaceae, Pontederiaceae). A complete failure to recover matK was observed in all eight nonangiosperm families (Appendix S5 (2.8MB, pdf) ), and seven angiosperm families (Boraginaceae, Crassulaceae, Droseraceae, Geraniaceae, Haloragaceae, Hypericaceae, Juncaceae) showed low recovery. ITS2 failed for one angiosperm family (Pontederiaceae) and for 11 of 16 nonangiosperm families. The families with low ITS2 recovery were mainly monocots (7), rosids (6), and asterids (6). Among poorly performing families, five were characterized by extensive sampling (>100 specimens): Boraginaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Juncaceae, Lamiaceae, and Polygonaceae (see Appendix S5 (2.8MB, pdf) for details).

Table 2.

Sequence recovery of rbcL, matK, and ITS2 for the families with sample size greater than nine specimens.

| rbcL (115 families) | matK (80 families) | ITS2 (106 families) | ||||

| Sequence recovery (%) | Angiosperms | Nonangiosperms | Angiosperms | Nonangiosperms | Angiosperms | Nonangiosperms |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 11 |

| 1–50 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 20 | 2 |

| 51–75 | 17 | 4 | 17 | 0 | 33 | 2 |

| 76–100 | 78 | 11 | 48 | 0 | 36 | 1 |

| Total no. of families attempted | 98 | 17 | 72 | 8 | 90 | 16 |

Recovery from herbarium specimens over time

Beta regression analysis demonstrated that sequence recovery for rbcL and matK was significantly lower for herbarium specimens ranging from 10–30 yr of age than for those collected in the past decade (Fig. 2, Appendix S4 (42.8KB, xlsx) ). Success was further reduced among older specimens. By contrast, a significant decline in sequence recovery for ITS2 was only noted in specimens older than 50 yr, although the average success for this marker at this age was comparable to that seen for the plastid markers.

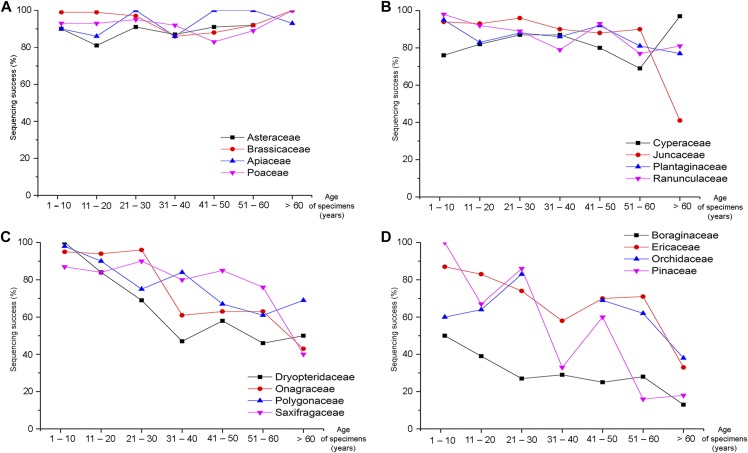

Beta regression identified four groupings with similar patterns in sequence recovery over time among the 25 families analyzed with this method. These groupings were clearest for the rbcL data set because of its comprehensive sampling across families and age groups (Fig. 3). The first group of families (including Apiaceae, Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, Poaceae) had consistently high sequence recovery for all age groups with no difference from the reference family (Fabaceae) (P > 0.05; Fig. 3A). The remaining three groups showed declining sequence recovery with age, but did so differently. The second group of families (Cyperaceae, Juncaceae, Plantaginaceae, Ranunculaceae) had high sequence recovery for herbarium material less than 50 yr old, but a noticeable decline in older specimens (0.01 < P < 0.05; Fig. 3B). The third group (Dryopteridaceae, Onagraceae, Polygonaceae, Saxifragaceae) delivered high sequencing success for material less than 10 yr old followed by a gradual decline with each decade (0.001 < P < 0.01; Fig. 3C). The final group showed a rapid decline in sequence recovery with time (P < 0.001; Fig. 3D). In particular, three families (Ericaceae, Pinaceae, Rosaceae) had initially high success (decade 1: 88–100%) that declined rapidly with age, while two families (Boraginaceae, Orchidaceae) had poor sequence recovery even for the youngest material (<10 yr) that declined further in older specimens (<40%).

Fig. 3.

Recovery of rbcL from herbarium specimens in seven age classes (decades 1–7+) from 16 species-rich families. Changes in sequence recovery over time used a beta regression model to test whether recovery was significantly different than the best-performing family (Fabaceae). (A) No difference from the reference family (P > 0.05). (B) Significant difference compared to the reference family (0.01 < P < 0.05). (C) Significant difference compared to the reference family (0.001 < P < 0.01). (D) Significant difference compared to the reference family (P < 0.001).

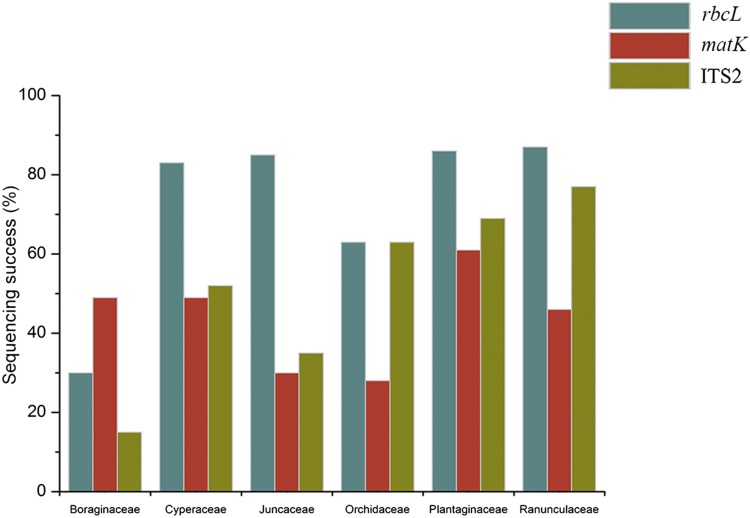

The results of the beta regression analyses for matK and ITS2 sequencing success were consistent with those for rbcL (Fig. 2). For example, sequencing success was high for all specimens and markers for four families (Apiaceae, Asteraceae, Caryophyllaceae, Salicaceae). Five families had high recovery for all material for at least two markers (Amaranthaceae, Betulaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Orobanchaceae, Saxifragaceae). Conversely, six families (Boraginaceae, Cyperaceae, Juncaceae, Orchidaceae, Plantaginaceae, Ranunculaceae) showed a significant decline in recovery with age for all three barcode regions. Among those, Boraginaceae and Orchidaceae showed strikingly low average sequencing success for rbcL (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Average sequence recovery of each DNA barcode from herbarium specimens of six families with the lowest success.

Recovery from silica gel vs. herbarium material

Beta regression analysis demonstrated that the three markers responded differently to preservation method with respect to sequence recovery (Fig. 2, Appendix S4 (42.8KB, xlsx) ). For ITS2, seven of 23 families showed recovery similar to the reference family (Brassicaceae), while 11 families had lower recovery and five had higher recovery for material preserved in silica gel compared to herbarium. For rbcL and matK, preservation method had no effect on sequence recovery for 16 families, while the other eight families showed a significant difference in sequence recovery but with no consistent pattern.

Additional DNA purification of the specimens belonging to Boraginaceae

All specimens of Boraginaceae, regardless of age or preservation method, delivered low average sequence recovery (rbcL 31%, matK 46%, ITS2 17%), and a secondary DNA purification step (Ivanova et al., 2008) failed to improve recovery. The potential for mismatch of the standard rbcL primers with this family was checked using GenBank reference rbcL sequences for Myosotis L. (KJ841424) and Hydrophyllum L. (HQ590137), but neither sequence had mismatches.

Identification with DNA barcodes and new alien species for Canada

Sequence data from the three markers led to the re-identification of 192 herbarium specimens (dx.doi.org/10.5883/DS-VASCAN; the process IDs below indicate the records in this database). These cases of misidentification often involved morphologically similar species (e.g., Ribes americanum Mill. vs. R. nigrum L.) or species that require microscopic examination to evaluate characters (e.g., members of Chenopodiaceae). Some of these updates resulted in corrections to distributional data. For example, R. laxiflorum Pursh was reported from Yukon based on a single record (BBYUK2558-16), but DNA barcode analysis led to the reassignment of this specimen to R. glandulosum Grauer and excluded R. laxiflorum from the flora of Yukon. Conversely, DNA barcodes confirmed the presence of Ranunculus occidentalis Nutt. (BBYUK1525-12) in the Northwest Territories, which was previously reported only from Yukon, British Columbia, and Alberta.

Our DNA barcode database includes representatives of 101 species that were collected in Canada and the adjacent United States, but not listed in VASCAN (Appendix S1 (13.4KB, xlsx) ; dx.doi.org/10.5883/DS-VASCAN). These species, some with medicinal properties, are often cultivated in botanical gardens (e.g., Trigonella foenum-graecum L., Atropa belladonna L., Crataegus viridis L.) or are widely cultivated as ornamentals (e.g., Ginkgo biloba L., Wisteria sinensis (Sims) DC.). Some were previously reported from the United States (Cullina et al., 2011; Glenn, 2013) as native (Coreopsis pubescens Elliott: KSR336-07) or as being introduced (Euphrasia micrantha Rchb.: BBYUK2400-13, VASCA592-15; Verbascum phoeniceum L.: PLWEL091-10). Other species have been reported from Canada (Zika, 2013) but are not included in VASCAN yet (Juncus hesperius (Piper) Lint: VPSBC1118-13; J. laccatus Zika: VPSBC1121-13). Finally, our database provides coverage for 42 native North American species recorded from adjacent regions in the United States (e.g., Claytonia acutifolia Pall. ex Willd.: BBYUK2574-16; Papaver alaskanum Hultén: BBYUK1286-12, BBYUK1287-12) that may occur in Canada.

DISCUSSION

Factors contributing to sequence recovery

The comprehensive nature of our DNA barcode library for the Canadian flora made it possible to examine factors influencing sequence recovery at a large scale. Two-thirds of the material we sampled was derived from herbarium specimens. Given our extensive use of older material (84% >10 yr), we expected that DNA degradation would hinder sequence recovery (de Vere et al., 2012). Our results confirmed that sequence recovery was problematic for the longer plastid barcodes rbcL (552 bp) and matK (∼800 bp) from material older than 10 yr (Fig. 2, Appendix S4 (42.8KB, xlsx) ). This effect was less noticeable for the shorter nuclear marker ITS2 (∼350 bp), as its sequence recovery significantly declined only in material older than 50 yr. This difference in recovery rate between plastid and nuclear markers is likely caused by the different lengths of the target regions, rather than any inherent difference between organellar compartments (Lister et al., 2008), as all three markers are expected to be present in high copy number in each cell.

Species-rich families with consistently high sequence recovery for all material (e.g., Asteraceae; Fig. 2, Test 1; Appendix S4 (42.8KB, xlsx) ) represent three major phylogenetic clades (rosids, caryophyllids, and asterids) that have undergone recent, explosive radiations (e.g., Liu et al., 2006; Valente et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2017b). These groups were the main consideration during design of the standard primer sets because they represent so much plant diversity at the species level. The strong affiliation of the primers to conserved sites flanking the DNA barcode regions in these taxonomic groups allowed consistent recovery, even from older degraded material. By contrast, another group of families (including Cyperaceae, Poaceae, Pinaceae) demonstrated clear evidence of a decline in sequence recovery with specimen age. Using sequence data available in GenBank, we found that many had primer mismatches for at least one of the DNA barcode regions. We hypothesize that the long history of Pinaceae, which has a crown age of 198 Ma (Lu et al., 2014), has allowed the accumulation of substitutions in the primer-binding regions. Although Cyperaceae and Poaceae form much younger crown groups (82 Ma and 65 Ma, respectively; Bouchenak-Khelladi et al., 2014), their elevated rates of substitutions (e.g., Hilu and Liang, 1997) likely created the same effect. Primer mismatches for some groups of monocots may similarly reflect the well-documented acceleration of plastome evolution in the order Poales (grasses, sedges, rushes, and relatives) vs. most other monocots and eudicots (e.g., Saarela and Graham, 2010). Only two cases of primer mismatch were recorded for rbcL (Ophioglossaceae, Selaginellaceae) (Appendix S5 (2.8MB, pdf) ). Such cases were more frequent for matK in three species-rich families (Juncaceae, Plantaginaceae, Ranunculaceae) and in some smaller families (e.g., Crassulaceae, Geraniaceae, Haloragaceae, Hypericaceae). Although partial primer incompatibility may not prevent amplification, it undoubtedly contributes to the reduced sequencing success in older herbarium material owing to DNA degradation and the resulting substantial decline in copy number of nondegraded molecules (Staats et al., 2011, 2013). The lack of universal priming sites as a cause of reduced sequence recovery is well-recognized for matK (Dunning and Savolainen, 2010). This issue is particularly challenging for most ferns, in which the plastid genome has lost the conserved trnK exons that are usually used as flanking conservative sites for amplification of the entire matK gene (Kuo et al., 2011).

The priming sites for ITS2 were previously proposed as mostly “universal” (Chen et al., 2010; China Plant BOL Group, 2011), but our results suggest this is not the case. Primer sites in template sequences are not completely conserved within certain species-rich (Cyperaceae, Juncaceae, Poaceae) and other less diverse families (Araceae, Commelinaceae, Ginkgoaceae, Isoetaceae, Orchidaceae, Pinaceae, Pontederiaceae, Typhaceae) (Appendix S6 (10.1KB, xlsx) ). The limited availability of sequence records for ITS2 for ferns makes it difficult to ascertain if amplification of this DNA region fails for the same reason. We recovered ITS2 data for eight genera (Asplenium L., Azolla Lam., Cyathea Sm., Ceratopteris Brongn., Dryopteris Adans., Equisetum L., Lygodium Sw., and Psilotum Sw.) of monilophytes (ferns sensu lato) in GenBank. Other ITS2 sequences on GenBank, annotated as being from ferns, actually originate from fungal or angiosperm contaminants based on BLAST.

ITS2 can also possess divergent copies within the nuclear genome, which can lead to the amplification of paralogous sequences from multiple templates (e.g., Xu et al., 2017). Song et al. (2012) suggested that intragenomic variation within this DNA region occurs more frequently than previously reported (Chen et al., 2010; China Plant BOL Group, 2011). Our data showed the recovery of ITS2 sequences was <75% in almost half of the species-rich families (e.g., Apiaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Orobanchaceae, Poaceae, Polygonaceae). In most instances, PCR products were obtained, but chromatograms acquired with Sanger sequencing were not interpretable. This result is most easily explained by the presence of multiple paralogous copies of ITS2. Whether as a result of gene duplication, hybridization, or polyploidy, the presence of multiple variants in high proportions negatively affects the successful recovery and application of ITS2 as a DNA barcoding marker in a substantial fraction of taxonomic groups (e.g., Zarrei et al., 2015).

Rapid DNA degradation after sample collection is likely a significant cause of amplification failure in some groups. We observed very low success in the recovery of all three DNA barcode regions, regardless of the method of preservation, in two families (Boraginaceae and Orchidaceae) in which we had little reason to suspect primer incompatibility (Fig. 3, Appendix S4 (42.8KB, xlsx) ). We hypothesize that DNA degradation occurs soon after collection in these families owing to the presence of compounds that degrade DNA or irreversibly bind to it. For example, most genera of Boraginaceae synthesize and store pyrrolizidine alkaloids, compounds that cause rapid and permanent DNA damage (El-Shazly and Wink, 2014). We suggest this type of metabolite may prevent DNA preservation during the early phases of drying, immediately following specimen collection. The polyphenols found in some Orchidaceae species are also well known for their DNA-binding activity, particularly in the presence of polyphenol oxidase, which is liberated during plant tissue damage (Ho, 1999; Mazo et al., 2012). Irreversible DNA damage in specimens from these families may only be prevented by neutralizing enzymatic activity at the earliest stages of plant tissue preservation. To achieve consistent sequence recovery, immediate DNA extraction with modified DNA extraction methods (e.g., Ivanova et al., 2011) after specimen collection may be essential.

Different stages of degradation of the plastid genome in holoparasitic or mycoheterotrophic plants can lead to the pseudogenization or complete loss of plastid-encoded loci (Graham et al., 2017) including rbcL (e.g., Corallorhiza Gagnebin [Barrett and Davis, 2012], mycoheterotrophic Ericaceae [Braukmann et al., 2017b], holoparasitic Orobanchaceae [Wicke et al., 2013], Cuscuta L. [McNeal et al., 2007; Braukmann et al., 2013]) and matK (e.g., Cuscuta [McNeal et al., 2007; Braukmann et al., 2013], Monotropsis Schwein. ex Elliott [Braukmann et al., 2017b]). Therefore, the amplification of plastid loci (especially rbcL) failed for these plants, or in some cases led to the recovery of pseudogenes. Barcoding efforts should focus on the nuclear-encoded loci (i.e., ITS2) given plastome degradation in these plants, or on alternate plastid loci that are commonly retained in nonphotosynthetic plants, such as accD (Lam et al., 2016).

Contrary to initial expectations, we encountered cases where sequence recovery from herbarium material was better than that from material preserved in silica gel. Most families with low recovery from samples stored in silica gel also have low rates of recovery from older herbarium material. It is likely that PCR amplification in these families was strongly affected by extrinsic factors (poor primer matches or presence of DNA-degrading metabolites) that are exacerbated over time, causing a substantial reduction in template copy number for the targeted DNA regions (Staats et al., 2011). The better performance of herbarium specimens vs. material preserved in silica gel may also reflect deviation from proper handling of samples prior to their storage in silica gel. Any delay between collection and storage on silica increases the opportunity for metabolites to damage DNA before the sample is fully dried. Long-term storage of specimens in silica gel requires additional control of humidity and isolation from light. Improper storage conditions may result in greater DNA damage than for herbarium specimens preserved in constantly dark, dry conditions.

The effects of DNA degradation seem to be exacerbated in families where there is mismatch between the standard primers and the priming regions, potential intragenomic variation (paralogy in ITS), and/or presence of certain metabolites that affect DNA integrity. All these factors may affect the quality and completeness of a DNA barcode reference library and thus have a direct influence on the interpretation of results from any applications using it. Further customization of protocols to accommodate different primer sets for phylogenetically diverse clades and to neutralize secondary metabolites will improve overall accuracy and completeness of the sequence data. Our results demonstrate that herbarium specimens are suitable for most plant families as the main source of material and that several large families (e.g., Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Brassicaceae) can be successfully sampled from older herbarium material without significantly affecting the quality of the results.

Taxonomic representation of the Canadian flora in the DNA barcode library

The use of a substantial fraction of herbarium specimens in our study ensured nearly complete representation of the vascular plant species in the flora of Canada. In addition to the names used in the standard checklist, our database retained all primary taxonomic annotations that accompanied the herbarium vouchers, which are mostly also available as digitized images. This information remains critical for applying the most recent and accurate taxonomic updates to a herbarium voucher and the associated record in BOLD (dx.doi.org/10.5883/DS-VASCAN).

The existing VASCAN checklist is subject to periodic revision based on new information from local checklists, nomenclatural changes, species discovery, and inventories of alien species. For example, the British Columbia Conservation Data Centre (2016) reported about 100 taxonomic name changes, 39 taxonomic rank changes, and 53 new taxon records for the vascular plants for British Columbia in 2016. Although the discovery of new vascular plant species in Canada is less common, one was recently described from the Yukon (Draba bruce-bennettii Al-Shehbaz; Al-Shehbaz, 2016). An inventory of nonnative species is particularly challenging because their distribution constantly changes (Cox, 1999; Davis et al., 2011). However, DNA barcode libraries must include these species because of their utility in forensic cases (Ivanova et al., 2016), ecological surveys (Bell et al., 2017), and in the detection of invasive species in local communities (van de Wiel et al., 2009; Ghahramanzadeh et al., 2013). The inclusion of both native and alien species occurring in the adjacent United States complements the genetic diversity of these taxa in our DNA barcode library with their closest counterparts outside Canada and provides more complete information with respect to their phylogeographic status. Future additions to the DNA barcode library of the vascular plants of Canada should focus on the inclusion of such species.

In addition to the advantages for obtaining DNA barcodes (easy accessibility, completeness of documentation, reduced costs and time), herbarium vouchers also provide an opportunity to cross-check voucher annotation with a molecular data set, which improves the quality of both collections. The robust reference library presented here has facilitated the improvement of local floristic checklists and the tracking of alien or invasive species. It also contributes to updates on the distribution of species. As a publicly available, actively managed database, the Vascular Plants of Canada library in BOLD is a comprehensive and effective system that facilitates plant diversity information sharing and creates an unparalleled genetic resource for the study of temperate and arctic biomes.

DATA ACCESSIBILITY

BOLD (dx.doi.org/10.5883/DS-VASCAN); GenBank (accession numbers associated with the process identification numbers in BOLD).

Supplementary Material

LITERATURE CITED

- Aiken S. G., Dallwitz M. J., Consaul L. L., McJannet C. L., Boles R. L., Argus G. W., Gillett J. M., et al. 2007. Flora of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago: Descriptions, illustrations, identification, and information retrieval. NRC Research Press, National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Website http://nature.ca/aaflora/data [accessed 16 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shehbaz I. A. 2016. Draba bruce-bennettii (Brassicaceae), a remarkable new species from Yukon Territory, Canada. Harvard Papers in Botany 21: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology 215: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker F. T., Lei D., Yu J., Mohammadin S., Wei Z., van de Kerke S., Gravendeel B., et al. 2016. Herbarium genomics: Plastome sequence assembly from a range of herbarium specimens using an Iterative Organelle Genome Assembly pipeline. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 117: 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett F., Davis J. I. 2012. The plastid genome of the mycoheterotrophic Corallorhiza striata (Orchidaceae) is in the relatively early stages of degradation. American Journal of Botany 99: 1513–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell K. L., Loeffler V. M., Brosi B. J. 2017. An rbcL reference library to aid in the identification of plant species mixtures by DNA metabarcoding. Applications in Plant Sciences 5: 1600110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten J., Bilton D. T., Fujisawa T., Elliott M., Monaghan M. T., Balke M., Hendrich L., et al. 2012. The effect of geographical scale of sampling on DNA barcoding. Systematic Biology 61: 851–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bininda-Emonds O. R. P. 2005. Software transAlign: Using amino acids to facilitate the multiple alignment of protein-coding DNA sequences. BMC Bioinformatics 6: 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks H. J. B., Birks H. H. 2016. How have studies of ancient DNA from sediments contributed to the reconstruction of Quaternary floras? New Phytologist 209: 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchenak-Khelladi Y., Muasya A. M., Linder H. P. 2014. A revised evolutionary history of Poales: Origins and diversification. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 175: 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Braukmann T., Kuzmina M., Stefanovic S. 2013. Plastid genome evolution across the genus Cuscuta (Convolvulaceae): Two clades within subgenus Grammica exhibit extensive gene loss. Journal of Experimental Botany 64: 977–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braukmann T. W. A., Kuzmina M. L., Sills J., Zakharov E. V., Hebert P. D. N. 2017a. Testing the efficacy of DNA barcodes for identifying the vascular plants of Canada. PLoS One 12: e0169515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braukmann T. W. A., Broe M. B., Stefanovic S., Freudenstein J. V. 2017b. On the brink: The highly reduced plastomes of nonphotosynthetic Ericaceae. New Phytologist 216: 254–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Conservation Data Centre. 2016. BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer. B.C. Ministry of Environment, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. Website http://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ [accessed 27 December 2016].

- Brouillet L., Coursol F., Meades S. J., Favreau M., Anions M., Bélisle P., Desmet P. 2010. onward (continuously updated). VASCAN, the Database of Vascular Plants of Canada. 10.5886/zw3aqw. Website http://data.canadensys.net/vascan/ [accessed 22 October 2017].

- Burgess K. S., Fazekas A. J., Kesanakurti P. R., Graham S. W., Husband B. C., Newmaster S. G., Percy D. M., et al. 2011. Discriminating plant species in a local temperate flora using the rbcL+matK DNA barcode. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2: 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- CBOL Working Group. 2009. A DNA barcode for land plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 106: 12794–12797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase M. W., Christenhusz M. J. M., Fay M. F., Byng J. W., Judd W. S., Soltis D. E., Mabberley D. J., et al. 2016. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 181: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Yao H., Han J., Liu C., Song J., Shi L., Zhu Y., et al. 2010. Validation of the ITS2 region as a novel DNA barcode for identifying medicinal plant species. PLoS One 5: e8613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China Plant BOL Group. 2011. Comparative analysis of a large dataset indicates that internal transcribed spacer (ITS) should be incorporated into the core barcode for seed plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 108: 19641–19646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc-Blain J. L., Starr J. R., Bull R. D., Saarela J. M. 2010. A regional approach to plant DNA barcoding provides high species resolution of sedges (Carex and Kobresia, Cyperaceae) in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Molecular Ecology Resources 10: 69–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody W. J. 2000. Flora of the Yukon Territory, 2nd ed. NRC Research Press, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Coissac E., Hollingsworth P. M., Lavergne S., Taberlet P. 2016. From barcodes to genomes: Extending the concept of DNA barcoding. Molecular Ecology 25: 1423–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox G. W. 1999. Alien species in North America and Hawaii: Impact on natural ecosystems. Island Press, Washington, D.C., USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cribari-Neto F., Zeileis A. 2009. Beta regression in R. ePubWU Institutional Repository. Department of Statistics and Mathematics, WU Wirtschaftsuniversitätien, Vienna, Austria. Website http://statmath.wu.ac.at/ [accessed 12 March 2017].

- Cullina M. D., Connolly B., Sorrie B., Somers P. 2011. The vascular plants of Massachusetts: A county checklist, first revision. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough, Massachusetts, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. A., Chew M. K., Hobbs R. J., Lugo A. E., Ewel J. J., Vermeij G. J., Brown J. H., et al. 2011. Don’t judge species on their origins. Nature 474: 153–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vere N., Rich T. C. G., Ford C. R., Trinder S. A., Long C., Moore C. W., Satterthwaite D., et al. 2012. DNA barcoding the native flowering plants and conifers of Wales. PLoS One 7: e37945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng B. 2015. Plant collections left in the cold by cuts: North America’s herbaria wilt under pressure for space and cash. Nature 523: 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet P., Brouillet L. 2013. Database of Vascular Plants of Canada (VASCAN): A community contributed taxonomic checklist of all vascular plants of Canada, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and Greenland. PhytoKeys 25: 55–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning L. T., Savolainen V. 2010. Broad-scale amplification of mat K for DNA barcoding plants, a technical note. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 164: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. 2004. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 32: 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T., Davies J. 2014. Challenges to barcoding an entire flora. Molecular Ecology Resources 14: 883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Shazly A., Wink M. 2014. Diversity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids in the Boraginaceae structures, distribution, and biological properties. Diversity (Basel) 6: 188–282. [Google Scholar]

- Elven R., Murray D. F., Razzhivin V., Yurtsev B. A. [eds.]. 2011. Annotated checklist of the Panarctic Flora (PAF) vascular plants. Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway. Website http://nhm2.uio.no/paf/ [accessed 30 November 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson D. L., Jones F. A., Swenson N. G., Pei N., Bourg N. A., Chen W., Davies S. J., et al. 2014. Comparative evolutionary diversity and phylogenetic structure across multiple forest dynamics plots: A mega–phylogeny approach. Frontiers in Genetics 5: 358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson D. L., Reed E., Ramachandran P., Bourg N. A., McShea W. J., Ottesen A. 2017. Reconstructing a herbivore’s diet using a novel rbc L DNA mini-barcode for plants. AoB Plants 9: plx015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazekas A. J., Kuzmina M. L., Newmaster S. G., Hollingsworth P. M. 2012. DNA barcoding methods for land plants. In W. J. Kress and D. L. Erickson [eds.], Methods in molecular biology, vol. 858: DNA barcodes: Methods and protocols, 223–252. Springer, New York, New York, USA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S. L. P., Cribari-Neto F. 2004. Beta regression for modelling rates and proportions. Journal of Applied Statistics 31: 799–815. [Google Scholar]

- Flora of North America Editorial Committee [eds.]. 1993. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Oxford University Pres, New York, New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahramanzadeh R., Esselink G., Kodde L. P., Duistermaat H., van Valkenburg J. L., Marashi S. H., Smulders M. J., van de Wiel C. C. 2013. Efficient distinction of invasive aquatic plant species from non-invasive related species using DNA barcoding. Molecular Ecology Resources 13: 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn S. D. 2013. New York Metropolitan Flora database. New York Metropolitan Flora Project, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, New York, New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S. W., Lam V. K. Y., Merckx V. S. F. T. 2017. Plastomes on the edge: The evolutionary breakdown of mycoheterotroph plastid genomes. New Phytologist 214: 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert P. D. N., Cywinska A., Ball S. L., DeWaard J. R. 2003. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Biological Sciences 270: 313–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilu K. W., Liang H. 1997. The mat K gene: Sequence variation and application in plant systematics. American Journal of Botany 84: 830–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K.-K. 1999. Characterization of polyphenol oxidase from aerial roots of an orchid, Aranda ‘Christine 130’. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 37: 841–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth P. M., Li D.-Z., van der Bank M., Twyford A. D. 2016. Telling plant species apart with DNA: From barcodes to genomes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 371: 20150338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories. 2012. Best practices for repositories: Collection, storage, retrieval, and distribution of biological materials for re-search. Biopreservation and Biobanking 10: 79–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova N. V., Grainger C. 2006. CCDB Protocols: Pre-made frozen PCR and sequencing plates. Available at http://ccdb.ca/site/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/CCDB_Sequencing.pdf [accessed 14 November 2017].

- Ivanova N. V., Fazekas A. J., Hebert P. D. N. 2008. Semi-automated, membrane-based protocol for DNA isolation from plants. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 26: 186–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova N., Kuzmina M., Fazekas A. 2011. CCDB Protocols: Manual protocol employing centrifugation: glass fiber plate DNA extraction protocol for plants, fungi, echinoderms and mollusks. Available at http://ccdb.ca/site/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/CCDB_DNA_Extraction-Plants.pdf [accessed 14 November 2017].

- Ivanova N. V., Kuzmina M. L., Braukmann T., Borisenko A., Zakharov E. 2016. Authentication of herbal supplements using next-generation sequencing. PLoS One 11: e0156426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartzinel T. R., Chena P. A., Coverdale T. C., Erickson D. L., Kress W. J., Kuzmina M. L., Rubenstein D. I., et al. 2015. DNA metabarcoding illuminates dietary niche partitioning by African large herbivores. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 112: 8019–8024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Misawa K., Kuma K., Miyata T. 2002. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Research 30: 3059–3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkenberg B. [ed.] 2013. E-Flora BC: Electronic atlas of the flora of British Columbia. Lab for Advanced Spatial Analysis, Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Website http://ibis.geog.ubc.ca/biodiversity/eflora/ [accessed 15 December 2016].

- Kraaijeveld K., De Weger L. A., García M. V., Buermans H., Frank J., Hiemstra P. S., Den Dunnen J. T. 2015. Efficient and sensitive identification and quantification of airborne pollen using next-generation DNA sequencing. Molecular Ecology Resources 15: 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress W. J., Erickson D. L., Jones F. A., Swenson N. G., Perez R., Sanjur O., Bermingham E. 2009. Plant DNA barcodes and a community phylogeny of a tropical forest dynamics plot in Panama. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 106: 18621–18626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo L.-Y., Li F.-W., Chiou W.-L., Wang C.-N. 2011. First insights into fern matK phylogeny. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 59: 556–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmina M., Ivanova N. 2011. CCDB Protocols: PCR amplification for plants and fungi. Available at http://ccdb.ca/site/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/CCDB_Amplification-Plants.pdf [accessed 14 November 2017].

- Kuzmina M. L., Johnson K. L., Barron H. R., Hebert P. D. N. 2012. Identification of the vascular plants of Churchill, Manitoba, using a DNA barcode library. BMC Ecology 12: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam V. K. Y., Merckx V. S. F. T., Graham S. W. 2016. A few-gene plastid phylogenetic framework for mycoheterotrophic monocots. American Journal of Botany 103: 692–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi M., Dimech M., Arculeo M., Biondo G., Martins R., Carneiro M., Carvalho G. R., et al. 2014. DNA barcoding for species assignment: The case of Mediterranean marine fishes. PLoS One 9: e106135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister D. L., Bower M. A., Howe C. J., Jones M. K. 2008. Extraction and amplification of nuclear DNA from herbarium specimens of emmer wheat: A method for assessing DNA preservation by maximum amplicon length recovery. Taxon 57: 254–258. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.-Q., Wang Y.-J., Wang A.-L., Hideaki O., Abbott R. J. 2006. Radiation and diversification within the Ligularia–Cremanthodium–Parasenecio complex (Asteraceae) triggered by uplift of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 38: 31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Raghavan S., Nelesen S., Linder C. R., Warnow T. 2009. Rapid and accurate large scale coestimation of sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees. Science 324: 1561–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Ran J.-H., Guo D.-M., Yang Z.-Y., Wang X.-Q. 2014. Phylogeny and divergence times of gymnosperms inferred from single-copy nuclear genes. PLoS One 9: e107679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazo L., Gomez A., Quintanilla S. R., Valdivieso P. O. 2012. Extraction and amplification of DNA from orchid exsiccates conserved from more than half a century in a herbarium in Bogotá, Colombia. Lankesteriana 12: 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- McNeal J. R., Kuehl J. V., Boore J. L., De Pamphilis C. W. 2007. Complete plastid genome sequences suggest strong selection for retention of photosynthetic genes in the parasitic plant genus Cuscuta. BMC Plant Biology 7: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill J., Turland N. J., Barrie F. R., Buck W. R., Greuter W., Wiersema J. H. 2012. International code of nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants. Koeltz Scientific Books, Konigstein, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Naciri Y., Linder P. H. 2015. Species delimitation and relationships: The dance of the seven veils. Taxon 64: 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier I., Duminil J., Kuzmina M., Philippe M., Thomas D. W., Kenfack D., Chuyong G. B., et al. 2013. How effective are DNA barcodes in the identification of African rainforest trees? PLoS One 8: e54921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser S. W. J., Hebert P. D. N. 2017. Rapid identification of the botanical and entomological sources of honey using DNA metabarcoding. Food Chemistry 214: 183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. 2008. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnasingham S., Hebert P. D. N. 2007. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System (http://www.barcodinglife.org). Molecular Ecology Notes 7: 355–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson R. T., Lin C.-H., Sponsler D. B., Quijia J. O., Goodell K., Johnson R. M. 2015. Application of ITS2 metabarcoding to determine the provenance of pollen collected by honey bees in an agroecosystem. Applications in Plant Sciences 3: 1400066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarela J. M., Graham S. W. 2010. Inference of phylogenetic relationships among the subfamilies of grasses (Poaceae: Poales) using meso-scale exemplar-based sampling of the plastid genome. Botany 88: 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Saarela J. M., Sokoloff P. C., Gillespie L. J., Consaul L. L., Bull R. D. 2013. DNA barcoding the Canadian Arctic flora: Core plastid barcodes (rbcL + matK) for 490 vascular plant species. PLoS One 8: e77982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scriver M., Marinich A., Wilson C., Freeland J. 2015. Development of species-specific environmental DNA (eDNA) markers for invasive aquatic plants. Aquatic Botany 122: 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. R., Pryer K. M., Schuettpelz E., Korall P., Schneider H., Wolf P. G. 2006. A classification for extant ferns. Taxon 55: 705–731. [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Shi L., Li D., Sun Y., Niu Y., Chen Z., Luo H., et al. 2012. Extensive pyrosequencing reveals frequent intra-genomic variations of internal transcribed spacer regions of nuclear ribosomal DNA. PLoS One 7: e43971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staats M., Cuenca A., Richardson J. E., Vrielink-Van Ginkel R., Petersen G., Seberg O., Bakker F. T. 2011. DNA damage in plant herbarium tissue. PLoS One 6: e28448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staats M., Erkens R. H. J., van de Vossenberg B., Wieringa J. J., Kraaijeveld K., Stielow B., Geml J., et al. 2013. Genomic treasure troves: Complete genome sequencing of herbarium and insect museum specimens. PLoS One 8: e69189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takhtajan A. 1986. Floristic regions of the world. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA. [Google Scholar]

- The Plant List. 2013. The Plant List, Version 1.1. Website http://www.theplantlist.org/ [accessed 12 January 2017].

- Thiers B. 2017. (continuously updated). Index Herbariorum: A global directory of public herbaria and associated staff. New York Botanical Garden’s Virtual Herbarium. New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York, USA. Website http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/ [accessed 4 October 2016].

- Thorne R. F. 1993. Phytogeography. In Flora of North America Editorial Committee [eds.], Flora of North America North of Mexico, vol. 1: 132–153. Oxford University Press, New York, New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Valente L. M., Savolainen V., Vargas P. 2010. Unparalleled rates of species diversification in Europe. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Biological Sciences 277: 1489–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wiel C. C. M., van der Schoot J., van Valkenburg J. L., Duistermaat H., Smulders M. J. 2009. DNA barcoding discriminates the noxious invasive plant species, floating pennywort (Hydrocotyle ranunculoides L.f.), from non-invasive relatives. Molecular Ecology Resources 9: 1086–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitousek P. M., D’Antonio C. M., Loope L. L., Rejmanek M., Westbrooks R. 1997. Introduced species: A significant component of human-caused global change. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 21: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wicke S., Muller K. F., De Pamphilis C. W., Quandt D., Wickett N. J., Zhang Y., Renner S. S., Schneeweiss G. M. 2013. Mechanisms of functional and physical genome reduction in photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic parasitic plants of the broomrape family. Plant Cell 25: 3711–3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B., Zeng X.-M., Gao X.-F., Jin D.-P., Zhang L.-B. 2017. ITS non-concerted evolution and rampant hybridization in the legume genus Lespedeza (Fabaceae). Scientific Reports 7: 40057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrei M., Talent M., Kuzmina M., Lee J., Lund J., Shipley P. R., Stefanović S., Dickinson T. A. 2015. DNA barcodes from four loci provide poor resolution of taxonomic groups in the genus Crataegus. AoB Plants 7: plv045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Erickson D. L., Ramachandran P., Ottesen A. R., Timme R. E., Funk V. A., Luo Y., Handy S. M. 2017a. An analysis of Echinacea chloroplast genomes: Implications for future botanical identification. Scientific Reports 7: 216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.-D., Jin J.-J., Chen S.-Y., Chase M. W., Soltis D. E., Li H.-T., Yang J.-B., et al. 2017b. Diversification of Rosaceae since the Late Cretaceous based on plastid phylogenomics. New Phytologist 214: 1355–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zika P. F. 2013. A synopsis of the Juncus hesperius group (Juncaceae, Juncotypus) and their hybrids in western North America. Brittonia 65: 128–141. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

BOLD (dx.doi.org/10.5883/DS-VASCAN); GenBank (accession numbers associated with the process identification numbers in BOLD).