Abstract

Guided by emotional security theory, this study tested the hypothesis that children’s emotional insecurity mediates associations between interparental conflict and their social difficulties by undermining their affiliative goals in best friendships. Participants included 235 families with the first of five measurement occasions over a ten-year period occurring when children were in kindergarten (Mean age = 6 years). Findings from the lagged latent difference score analyses indicated that intensification of interparental conflict during the early school years predicted subsequent increases in children’s emotional insecurity five years later in adolescence. In the latter part of the cascade, rises in emotional insecurity predicted decreases in adolescent friendship affiliation which, in turn, were specifically associated with declines in social competence.

Keywords: interparental conflict, child stress reactivity, child social development

Interparental conflict is a risk factor for a wide array of children’s psychological problems (Harold & Leve, 2012; Jouriles, McDonald, & Kouros, 2016). As a key form of vulnerability, research has shown that children exposed to high levels of interparental conflict are particularly susceptible to developing social difficulties characterized by peer relationship problems, interpersonal withdrawal, and poor social competence (e.g., Goodman, Barfoot, Frye, & Belli, 1999; Kouros, Cummings, & Davies, 2010; Lindsey, Caldera, & Tankersley, 2009; Stocker & Youngblade 1999). Underscoring its developmental significance, social difficulties carry long-term, negative repercussions for well-being across multiple domains of functioning, including internalizing symptoms, behavior problems, and poor academic achievement (Bornstein, Hahn, & Haynes, 2010;, Obradovic, Long, & Masten, 2008; Sorlie, Hagen, & Ogden, 2008).

However, in spite of the documented developmental significance of social difficulties, little is known about why children exposed to interparental conflict experience these interpersonal problems (Cummings & Davies, 2011). A small handful of studies have shown that children’s aggressive interaction styles (i.e., externalizing dispositions, aggressive attitudes, anger regulation problems) partially account for the disproportionate risk for social difficulties experienced by children exposed to interparental conflict (e.g., Kinsfogel & Grych, 2004; Kouros, Cummings & Davies, 2010). Although the results of these studies testify to the value of examining intrachild mechanisms as mediators of associations between interparental conflict and children’s social impairments, the focus has been on testing the mediational role of broad forms of child functioning (i.e., externalizing problems, aggressogenic beliefs). By contrast, prevailing conceptual models share the premise that interparental conflict increases children’s long-term mental health problems (including social difficulties) by progressively altering their short-term responses to discord between parents over time (e.g., Davies & Martin, 2013; Grych & Fincham, 1990; Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002). However, questions remain about how children’s specific short-term responses to family conflict may help to further elucidate an understanding of why social difficulties develop from exposure to interparental conflict. To address this significant gap, the current study aims to trace the cascade of intrachild processes that link interparental conflict with children’s subsequent social difficulties. Guided by emotional security and risky family process models (Davies & Martin, 2013; Repetti, Robles, & Reynolds, 2011), we specifically test the hypothesis that children’s social difficulties in the wake of interparental conflict develop gradually over time by setting in motion a cascade whereby children’s distress responses to interparental conflict initiate a chain of processes that serve to undermine their affiliative goals in close friendships.

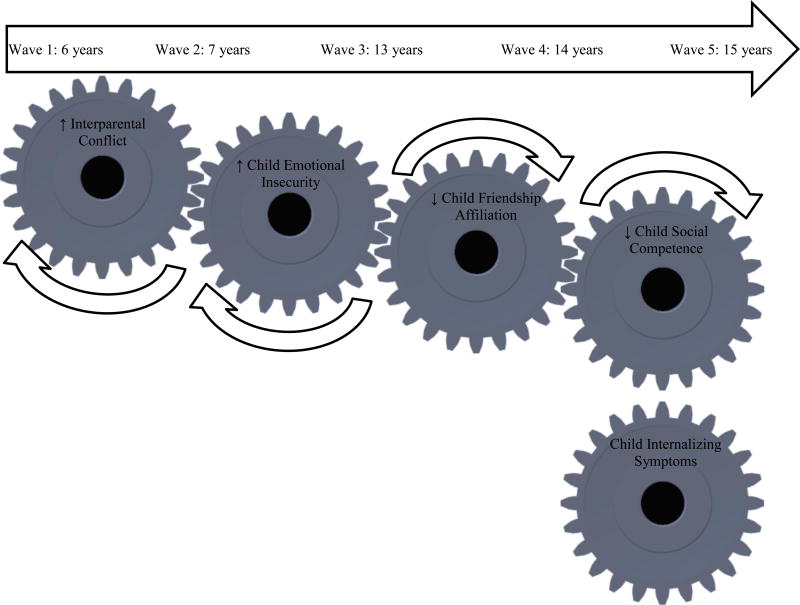

As an organizing framework for our conceptualization, Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized chain of processes linking interparental conflict and children’s social difficulties. Consistent with the risky families model (Repetti et al., 2002; 2011), interparental conflict is conceptualized as a stressful event that sets in motion a chain of processes whereby children’s short-term distress responses to subsequent family conflicts ultimately increase their psychological health problems by expanding to affect their functioning in settings outside the context of the family. Providing further direction in specifying this cascade, emotional security theory specifically postulates that children’s difficulties preserving a sense of security in the interparental relationship reflect a key class of short-term responses to family events mediating the link between interparental conflict and children’s psychological adjustment (EST; Davies & Cummings, 1994). In the first link of the mediational chain, illustrated in Figure 1, interparental conflict is conceptualized as threatening children’s goal of preserving their security in the interparental relationship. Difficulties achieving emotional security (i.e., insecurity) are manifested in three forms of overt reactivity to interparental conflict: (a) emotional reactivity characterized by heightened fearful distress reactions to conflict, (b) intensive avoidance, as children seek to minimize their exposure to the threatening event, and (c) intense involvement in an attempt to actively mediate or distract parents from interparental disputes. Higher levels of insecurity, in turn, are proposed to increase children’s vulnerability to psychological problems (Cummings & Davies, 2011).

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of the dynamic developmental cascade involving interparental conflict, children’s emotional insecurity, and their subsequent social functioning.

Longitudinal studies have consistently supported the mediational role of children’s insecurity in prospective associations between interparental conflict and a wide array of psychological problems characterized by school, internalizing, and externalizing problems (Cummings & Miller-Graff, 2015). Although social difficulties have been repeatedly identified as sequelae of interparental conflict, they have rarely been examined as outcomes in tests of well-articulated theoretical models, such as attachment theory or EST. However, there is at least some initial support for the proposed pathway based on EST. Using data from the middle childhood phase of the longitudinal data set used in this paper, McCoy, Cummings, and Davies (2009) found that children’s insecurity in the interparental relationship mediated the prospective association between destructive interparental conflict and lower levels of children’s prosocial behavior. According to the risky families model, this documentation of mediation provides a basis for more systematically articulating the developmental cascades that lay the foundation for children’s adjustment. As shown by the series of four gears in Figure 1, children’s short-term reactivity to interparental conflict in the form of insecurity is likely to reflect a longer series of processes. Therefore, a main premise, based on EST, is that children’s responses to interparental conflict will increase their social difficulties by progressively altering the way they adapt to contexts outside the interparental or family setting.

Within the EST framework, calls for examining more precise cascades generate the question of how or why insecurity increases children’s risk for social problems. The reformulation of EST is specifically designed to address this question (EST-R; Davies & Martin, 2013). Drawing on evolutionary frameworks (see also attachment theory, Bowlby, 1969), EST-R proposes that the saliency of defending against threat for children who exhibit high levels of insecurity supersedes and undermines behavioral systems organized around approach-oriented goals. The etiology of social problems is specifically proposed to be rooted in the tendency of children’s insecurity to disrupt the operation of the affiliative system. As a motivational-emotional system that evolved to ultimately promote cooperative alliance with others, the affiliation system organizes intrinsic valuation and prioritization of cooperative interpersonal bonds (Depue & Morone-Strupinsky, 2005; Gilbert, 2015; Laursen & Hartl, 2013). Thus, over time, disruptions to the affiliation system in the form of diminished valuation in connecting and sharing with others are theorized to undermine social competence by hampering the processing of social cues and the acquisition of interpersonal skills, cooperation, prosocial behavior, and social standing in the peer group (Barry & Wentzel, 2006; Moore, Fu, & Depue, 2014).

Close (e.g., best) friendships are conceptualized as serving as a primary training ground for the development and refinement of the affiliative system (Furman, 2001; Hartup, 2009). Thus, as shown in Figure 1, EST-R proposes that insecurity in the interparental relationship mediates the association between interparental conflict and children’s social problems by undermining the saliency of affiliative goals in best friendships (Davies, Martin, & Sturge-Apple, 2016). That is, insecurity is proposed to reflect increasing prioritization of safety goals at the expense of children’s valuation of affiliative ties in close friendships. Thus, over time, insecurity may reduce their representations of the importance of affiliation (e.g., comradery, companionship) in best friendships. In turn, representations of affiliative themes in best friendships are theorized to lay the foundation for broader interpersonal difficulties by dampening children’s motivation to capitalize on opportunities to procure and refine social skills and gain standing in more complex and wider peer circles (Gilbert, 2015). Although research has yet to systematically capture the motivational underpinnings of affiliation in best friendships, indirect support for our hypothesis is evident in previous documentation of links between teen reports of greater friendship intimacy and classmate reports of their cooperative, prosocial behavior (Barry & Wentzel, 2006; Buhrmester, 1990). In addition, a primary premise is that the diminished saliency of affiliative themes in best friendships evidences some degree of specificity in its operation as a proximal risk mechanism for undermining competence within social domains of functioning rather than other areas of adjustment (Davies et al., 2016). As a first test of this hypothesis, we examined the specificity or generalizability of the mediating role of friendship affiliation in associations between interparental conflict, child insecurity, and their adjustment across social competence and internalizing domains of functioning. We specifically selected internalizing symptoms as a base of comparison based on evidence indicating that signs of emotional insecurity are particularly potent predictors of children’s emotional problems (Davies et al., 2016; Rhoades, 2008).

Although developmental cascade models offer insights into how to characterize the emergence of psychological problems, questions remain as to how to capture the unfolding series of processes underlying children’s vulnerability in risky family contexts (Brock & Kochanska, 2016; Cox, Mills-Koonce, Propper, & Gariépy, 2010; Fosco & Feinberg, 2015; Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Existing studies predominantly examine whether the static levels of factors assessed at a single time point predict change in the proposed downstream processes in the cascade. For example, the handful of prospective studies using EST as a framework have examined mediational pathways using single static snapshots of interparental conflict and emotional insecurity as predictors of children’s functioning (see review by Davies et al., 2016). These studies run counter to repeated recommendations to delineate the dynamic nature of relationships between fluctuations in interparental conflict and changes in child functioning (e.g., Cui, Conger, & Lorenz, 2005; Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Dukewich, 2001; Fincham, Grych, & Osborne, 1994). In addressing this gap, recent advances in the risky families model offer a novel direction in characterizing change in family processes that have important implications for understanding the precursors and sequelae of children’s insecurity. According to the risky families model, developmental pathways may be represented metaphorically as a successive series of interlocking, shifting gears (Repetti et al., 2011). Therefore, change in children’s functioning is not simply regarded as a product of static levels of upstream factors in the cascade. Rather, as illustrated in Figure 1, alterations in the first metaphorical gear representing interparental conflict are hypothesized to set in motion subsequent shifts in the child insecurity gear. The turning gear of insecurity, in turn, may ultimately give rise to movement in the social competence gear by triggering shifts in the friendship affiliation gear.

In highlighting the potential utility of more dynamic analytic approaches, studies have shown that escalating exposure to interparental conflict over time predicts concurrent increases in children’s negative emotional reactivity to conflict (Goeke-Morey, Papp, & Cummings, 2013) as well as lagged increases in their psychological problems (Cui, Conger, & Lorenz, 2005). However, to our knowledge, no studies of family risk have tested the lagged gear conceptualization within a mediational chain. Thus, our aim was to test the hypothesized insecurity cascade within the risky families conceptualization of change. We specifically examined whether increases in interparental conflict are associated with subsequent increases in children’s emotional insecurity. In the latter part of the cascade, we further tested whether decreases in friendship affiliation following from increases in insecurity predict subsequent decreases in children’s social competence.

To test the mediational pathways, we examined whether increases in children’s exposure to interparental conflict during the early school years predicted a subsequent pathogenic cascade of insecurity, dampened friendship affiliation, and social difficulties through the early adolescence period. Underscoring the salience of interparental conflict during the early school years, evolutionary models highlight the juvenile period (i.e., middle childhood) as a potential sensitive period or “switch point” for the translation of stress experiences into specific strategies for regulating stress and coping with threat and conflict (Del Giuidice, Angeleri, & Manera, 2009; Del Giudice & Belsky, 2011). Likewise, developmental models have further postulated that advances in social perspective taking during the early school years heighten children’s sensitivity to interparental conflict in ways that have long lasting implications for children’s concerns about their safety within the broader family unit (Cicchetti, Cummings, Greenberg, & Marvin, 1990; Davies et al., 2016). Children’s insecurity and friendship processes, in turn, may have particularly pronounced implications for adjustment during adolescence. For example, meta-analytic findings revealed that children’s negative emotional reactivity, avoidance, and involvement more strongly predicted their psychological adjustment in adolescence than in childhood (Rhoades, 2008). Likewise, the valuation of affiliation (reciprocity, disclosure, trust, shared activities) in close, same-sex friendships is theorized to be particularly prominent in early adolescence and play a significant role in teens’ social adjustment (e.g., Bagwell & Schmidt, 2011; Bukowski, Simard, Dubois, & Lopez, 2011).

In summary, our study tests a theoretically driven model of the unfolding sequence of changes in children’s experiences with interparental conflict, emotional insecurity, friendship affiliation, and social difficulties from childhood through middle adolescence. Specifically guided by EST-R (Davies & Martin, 2013), we utilized to multi-method (i.e., observations, interviews, surveys) and multi-informant (i.e., observer, mother, father, teacher, child) approach to examine whether children’s emotional insecurity mediated associations between interparental conflict and their social difficulties through its prediction of attenuations in friendship affiliation. Given empirical documentation of internalizing symptoms as the most common sequelae of emotional insecurity (Davies et al., 2016), we tested the specificity of the cascade by including both social competence and emotional problems as potential sequelae of successive changes in child insecurity and dampened friendship affiliation. In drawing on the shifting gears conceptualization in the risky families model (Repetti et al., 2011), our goal was to examine whether fluctuations in the exogenous or upstream family processes predicted subsequent changes in the downstream indices of child functioning in the cascade (see Figure 1).

Finally, we test whether the hypothesized cascade is robust in the context of several alternative mechanisms and covariates. First, we included family income, parent education, and child gender as covariates in the analyses. We selected these factors based on: (a) empirical identification of socioeconomic factors as correlates of interparental conflict processes and children’s psychological adjustment (e.g., Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010) and (b) some, albeit mixed, evidence that child gender (i.e., girls) is associated with friendship affiliation and interpersonal adjustment (e.g., Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Second, studies have identified insecurity in the parent-child relationship as both a correlate of children’s emotional insecurity in the interparental relationship and a predictor of indices of poor social competence in adolescence (e.g., Allen et al, 2002; Davies et al., 2016; Groh et al., 2014). Thus, the hypothesized role of friendship affiliation as a mediator of links between emotional insecurity and poor social competence may simply be an artifact of insecurity in the parent-child relationship and its more potent role as a risk mechanism. To address this possibility, we specifically delineated the mediational role of friendship affiliation in the broader context of examining parent-child insecurity as an alternative mediator. Third, it is also plausible that the hypothesized cascade to poor social competence is an epiphenomenon of the contemporaneous, static features of interparental conflict, emotional insecurity, or friendship affiliation processes (Roisman & Fraley, 2013). Therefore, we also tested whether the successive linkages among changes in interparental conflict, emotional insecurity, and diminished levels of adolescent friendship affiliation and poor social competence remained after also controlling for static levels of these constructs and stability experiences of interparental conflict and emotional insecurity during adolescence.

Methods

Participants

Participants were drawn from a larger project that originally included 235 parents and children recruited through local school districts and community centers in a moderate-sized metropolitan area in the Northeast and a small city in the Midwest. Interested families were included in the project if they met the following eligibility criteria: (a) the primary caregivers had a child in kindergarten; (b) the kindergarten child and two primary caregivers lived together for at least the preceding 3 years; and (c) the primary caregivers and child were fluent in English. Fifty-five percent of the sample consisted of girls. Median household income of the families was between $40,000 and $54,999 per year. On average, mothers and fathers completed comparable years of education, 14.54 years (SD = 2.33) and 14.68 years (SD = 2.69), respectively. Most parents (i.e., 92%) were married at the outset of the study. The majority of the sample was White (74%), followed by smaller percentages of participants from African American (16%), Latino (4%), multi-racial (3%), and other racial (3%) backgrounds. Children lived with their biological mother in most cases (95%), with the remainder of the sample living with either an adoptive mother (3%) or a stepmother or female guardian (2%). In addition, children lived with their biological father in the majority of cases (87%), with the remainder of the sample living with either an adoptive father (4%) or a stepfather or male guardian (9%). In the first stage of the longitudinal design, families participated in two annual measurement occasions beginning when children were in kindergarten (M age = 6 years). In the second stage, families returned for three more annual waves of data collection beginning when children were in 7th grade (M age = 13 years). Thus, the average ages of the children across the five waves were as follows: Waves 1 (6 years old), 2 (7 years old), 3 (13 years old), 4 (14 years old), and 5 (15 years old). Rates of retention across contiguous waves ranged from 86% to 97%. Families participating across the study were as follows: 235 at Wave 1, 227 at Wave 2, 195 at Wave 3, 190 at Wave 5, and 181 at Wave 6.

Procedures and Measures

Interparental conflict (Waves 1 and 2)

Three measurement batteries collected at Waves 1 and 2 were used as indicators of destructive interparental conflict at each time point based on mother, father, and observer report. For the first two sets of assessments, mothers and fathers independently completed the Verbal Aggression and Stonewalling scales from the Conflict and Problem-Solving Scales (Kerig, 1996) and the O’Leary Porter Scale (OPS; Porter & O’Leary, 1980). Whereas the 16 item CPS Verbal Aggression subscale assesses the frequency of verbal antagonism between parents (e.g., “Raise voice, yell, shout”), the Stonewalling subscale consists of 14 items indexing the extent to which parental conflicts are characterized by unresolved hostility, distress, and disengagement (e.g., “Storm out of the house”). The 10 items of the OPS are designed to assess children’s exposure to interparental hostility (OPS; Porter, & O’Leary, 1980; e.g., “How often do you and/or your partner display verbal hostility [raised voices, etc.] in front of your child?”). Internal consistencies for the mother and father reports on each of the scales ranged from .73 to .90 (Mean α = .82) across the two waves. Evidence for the validity of the scales is well documented (Kerig, 1996). To obtain more parsimonious indicators of destructive interparental conflict for analyses, the three scales were standardized and aggregated together for each informant. The resulting two composites of maternal and paternal reports of interparental conflict each possessed adequate internal consistency at the scale level, with αs of .83 at Wave 1 and .82 at Wave 2 for both mothers and fathers.

For the third composite indicator of interparental conflict, mothers and fathers participated in an interparental interaction task at Waves 1 and 2 in which they attempted to address two common, intense interparental disagreements that they viewed as problematic in their relationship (Cummings et al., 2006). The couples subsequently discussed each topic for ten minutes each while they were alone in the laboratory room. Videotaped records of the interactions were subsequently rated by three trained coders using five-point ordinal scales (1 = Very Low; 5 = High) from the System for Coding Interactions in Dyads (SCID; Malik & Lindahl, 2004). Trained coders coded interparental use of destructive conflict tactics across the twenty minute interaction along six SCID scales: (1) Negativity and Conflict, characterized by parental displays of anger and frustration, (2) Withdrawal, defined by the degree to which parents exhibited emotional disengagement and indifference; (3) Negative Escalation, with high scores reflecting intensification of negativity by the couple over the course of the conflict, (4) Pursuit Withdrawal characterized by one partner persistently responding with avoidance to the consistent demands of the other partner to engage in the conflict; (5) Cohesion, reverse scored so that higher scores indexed a higher degrees of interpersonal disengagement or fragmentation between parents; and (6) Support, reverse scored to reflect that higher values were indicative of a lack of attunement to each other’s needs. Interrater reliability, based on the intraclass correlation coefficients of two coders’ independent ratings on at least 20% of the interactions at each wave, ranged from .66 to .96 across six codes and two measurement occasions (Mean ICC = .86). To create an observational composite as the third indicator of interparental conflict for the primary analyses, the six scale scores were standardized and summed together for Waves 1 (α = .78) and 2 (α = .84), respectively.

Childhood insecurity in the interparental relationship (Waves 2 and 3)

During Wave 2, children completed the Emotional Reactivity, Involvement, and Avoidance Scales from the Young Child Version of the Security and Interparental Scales (SIS-YC; Davies, Sturge-Apple, Bascoe, & Cummings, 2014). The original Security in the Interparental Scale (SIS; Davies et al., 2002) and the SIS-YC are designed to capture comparable indices of insecurity. However, because the original SIS was designed for older children, the SIS-YC was modified in several ways to correspond with the developmental capacities of younger children. First, to increase comprehensibility, the SIS-YC is administered in interview format and response alternatives for items are reduced from five to three (i.e., 0 = No; 1 = Sometimes; 2 = Yes). Second, complexity in wording of the original items was simplified and original items assessing abstract, cognitive items (e.g., “I can’t stop thinking about their problems”) were replaced with more concrete, forms of reactivity (e.g., “Do you feel sick when your parents argue?”). Third, to prevent fatigue, items were designed to assess three of the original seven SIS scales. The resulting ten items on the Emotional Reactivity scale assessed children’s frequent and prolonged negative affective arousal (e.g., “When your parents have an argument, do you get scared?). The Involvement scale contained ten items measuring children’s attempts to mediate the conflict, comfort the parents, help solve the interparental problem, and coercively intervene (e.g., “When your parents argue, do you try to make your dad feel better?” “When your parents have an argument, do you tell your mom she is wrong about the argument?”). Five items comprising the Avoidance scale assessed children’s attempts to reduce their exposure to the interparental conflicts (e.g., “Do you try to get away from your parents when they argue”). Internal consistencies for the scales ranged from .73 to .86. Previous research supports the validity of the SIS-YC and its comparability with the original SIS (e.g., Davies et al., 2014; Davies, Martin, Coe, & Cummings, 2016). For example, according to EST-R, the relational coping properties are proposed to evidence modest to moderate stability in individual differences over time (Davies, Martin, & Sturge-Apple, 2016). Consistent with this hypothesis, insecurity as assessed by the SIS-YC during the early school years was a moderate predictor of the original SIS measure of insecurity five to six years later during early adolescence even after the inclusion of adolescent exposure to interparental conflict, family SES, and child sex as predictors (Davies et al., 2014).

At Wave 3 (i.e., 13 year old assessment), children completed the SIS in a survey format. The SIS, which is tailored to older children and adolescents, is designed to obtain comparable assessments to the SIS-YC. As the first measure of insecurity, the Emotional Reactivity scale assessed multiple, prolonged experiences of fear and distress in response to interparental conflict (e.g., 9 items; “When my parents argue, I feel scared”). As the second measure, the Avoidance scale consists of seven items that capture efforts to reduce their exposure to the conflict (e.g., “I try to get away from them”). As a third measure, we used the revised Involvement scale from the SIS because it provided a more comprehensive assessment of children’s involvement that is more comparable to the SIS-YC Involvement scale. Consistent with the SIS-YC, this revised Involvement scale captures comforting, mediating, and coercive forms of intervention (8 items; e.g., “I tell one of my parents that he or she is wrong”; “I try to comfort one or both of them”) (Shelton & Harold, 2008; Davies, Coe, Martin, Sturge-Apple, & Cummings, 2015). Alpha coefficients for the scales ranged from .74 to .89. The number of items and the response alternatives differed between comparable SIS and SIS-YC scales. Therefore, we standardized the scores on the scales across the two waves so they were on the same metric for our analyses of change.

Adolescent friendship affiliation (Waves 3 and 4)

At Waves 3 and 4, adolescents participated in the Three-Words Interview (3WI; Martin & Davies, 2012), a semi-structured, narrative interview about their best friendship adapted from the Friendship Interview (FI; Furman, 2001). In the 3WI, a trained experimenter first asked the adolescents to name a single best friend. Best friends could be of either sex, but could not be a blood relative or resident in the home. All adolescents were able to select a single best friend. The experimenter then asked the teens to select three words to describe their relationship with their best friend. For each word selected, the experimenter asked them to describe a memory to illustrate how or why their friendship reflected the chosen word. Experimenters continued to offer general probes (e.g., “Can you tell me more about that?” and “What about this memory explains why your friendship is [word chosen]?”) for each description until the teen indicated that they had no further information to share. Interviews were video-recorded and transcribed verbatim for later coding.

The Three-Words Coding System (3WCS; Martin & Davies, 2015) assesses the saliency of the affiliative systems for adolescents’ internal representations of their best friendship. At each wave, three trained raters independently evaluated the content, organization, and coherency of adolescents’ narratives to assess the strength of affiliation themes along a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 (No support for affiliation) to 7 (Strong support for affiliation). High ratings on friendship affiliation were evidenced by coherent descriptions of the friendship as serving to promote and sustain cooperation, reciprocity, and alliance with the friend. Descriptions reflecting a strong affiliative system consisted of episodic examples illustrating expressions of warmth and affection, a sense of shared identity or activity, humor, reciprocal validation, and intimate disclosure. Support for the construct validity of the 3WCS was found in a separate sample of 200 early adolescents and their parents (Martin & Davies, 2015). For example, friendship affiliation on the 3WCS was uniquely correlated with a comparable Affiliation subscale on the Behavioral Systems Questionnaire (Furman & Buhrmester, 2009). Interrater reliability was calculated for the two separate teams of three coders at each wave. Internal consistencies based on coding all the interviews were .70 at Wave 3 and .81 at Wave 4. Accordingly, the ratings of the three coders were averaged together to form a single composite of friendship affiliation at each wave.

Adolescent social competence (Waves 4 and 5)

Adolescents endorsed a current academic teacher who “you’ve spent the most time with and who knows you the best.” At Waves 4 and 5, teachers completed two measures of teen social competence: (1) the Social Competence Scale of the Teacher’s Rating Scale of Child’s Actual Behavior (TRSCAB; Harter, 1988), comprised of two items assessing children’s ability to get along with peers (“This individual does have a lot of friends”) and (2) the Prosocial with Peers Scale (7 items; e.g., “Kind toward peers,” “Cooperative with peers”) from the Child Behavior Scale (CBS; Ladd & Profilet, 1996). Alpha coefficients for the scales across each wave ranged from .74 to .90. The two measures were specified as manifest indicators of a latent construct of social competence at each wave.

Adolescent internalizing symptoms (Waves 4 and 5)

Adolescents completed three well-established assessments of their internalizing symptoms at Waves 4 and 5: (1) the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977; “I felt lonely”), a 20-item measure designed to measure adolescent depressive symptomatology; (2) the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1978; “I worry a lot of the time”), a 28-item scale capturing adolescent anxiety symptoms; and (3) the Emotional Symptoms scale from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, consisting of five items (“I have many fears, I am easily scared,” “I am often unhappy, depressed, or tearful”) assessing anxiety, depressive, and somatic symptoms (SDQ; Goodman, 1999). Reliabilities were acceptable for the three measures at Waves 4 and 5 (α ranged from .74 to .89). The assessments were utilized as indicators of a latent assessment of internalizing symptoms at each wave.

Covariates: Sociodemographic characteristics (Wave 1)

Three covariates were derived from parent reports of demographic characteristics: (1) children’s gender (1 = boys; 2 = girls); (2) Wave 1 parental educational level, calculated as the average of maternal and paternal years of education; and (3) total annual household income based on a 13-point ordinal scale ranging from 1 (less than $6,000) to 9 ($75,000 or more).

Covariate: adolescent-parent security

To assess children’s security in parent-child relationships at Waves 3 and 4, adolescents completed two self-report scales separately for mothers and fathers. As the first survey measure, the Child version of the Parental Attachment Security Scale (PASS; Davies, Harold, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2002) consisted of 15 items that index adolescent use of the target caregiver as a source of protection and support (e.g., “When I’m upset, I go to my mom [dad] for comfort.”). The second instrument consisted of adolescent reports on the Warmth and Affection subscale of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ; Rohner, Saavedra, & Granum, 1991). The Warmth and Affection scale is comprised of 20 items that assess adolescent appraisals of the emotional availability of the target caregiver (e.g., “My mom [dad] makes me feel wanted and needed”). Internal consistencies for the two measures ranged from .93 to .96 for mothers and fathers across the two waves and the validity of the scales is supported by previous research (e.g., Davies et al., 2002; Rohner, 2004). Adolescent reports of their relationships with mothers and fathers were highly correlated for both the PARQ and PASS at each wave (i.e., rs ranging from .57 to .75, all ps < .001). Therefore, adolescent reports of mothers and fathers were averaged together to form parsimonious, single indicators of PASS and PARQ at each wave.

Analysis Plan

Prior to conducting our analyses, we first examined whether rates of missingness in our data set were associated with any of the 31 primary variables and covariates and 10 additional sociodemographic variables (e.g., parent and child race, parent and child age, marital status). Three of the 41 analyses were significant, with higher rates of missingness associated with greater maternal reports of interparental conflict at Waves 1 (r = .14, p = .03), lower child reports of security in parent-child relationships at Wave 3 (r = −.29, p < .001), and lower family income at Wave 1 (r = −.14, p = .03). Full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) methods for estimating data successfully minimize bias in regression and standard error estimates for all types of missing data (i.e., MCAR, MAR, NMAR) when the amount of missing data is between 10% and 20% (Schlomer, Bauman, & Card, 2010). Therefore, given that data in our sample were missing for 18.0% of the values, we used FIML to retain the full sample for primary analyses (Enders, 2001).

To test the cascade of changing processes in the conceptual model in Figure 1, we used latent difference score (LDS) analyses within a structural equation modeling approach with Amos 22 software (McArdle, 2009). To capture individual differences in intraindividual change, we specified latent difference scores for each of the five main constructs: (1) Wave 1 to 2 change in children’s exposure to interparental conflict; (2) Wave 2 to 3 change in children’s insecurity; (3) Wave 3 to 4 changes in best friendship affiliation; and (4) Wave 4 to 5 changes in social competence and internalizing symptoms, respectively. Following conventional procedures, we specifically regressed the later assessment of each target construct onto both the previous assessment of the variable and the latent difference score while constraining both paths to 1 (see Burt & Obradovic, 2013; McArdle, 2009). Using the standard approach to estimating the proportional change components in the LDS analyses, we also specified a structural path between the initial level of the variable and the latent growth parameter for each of the interparental and child functioning constructs (for details, see Hawley, Ho, Zuroff, & Blatt, 2006; Sbarra & Allen, 2009). Factor loadings of the manifest indicators of latent variables indexing interparental conflict, emotional insecurity, social competence, and internalizing symptoms across the two time points were constrained to be equal to maximize measurement equivalence.

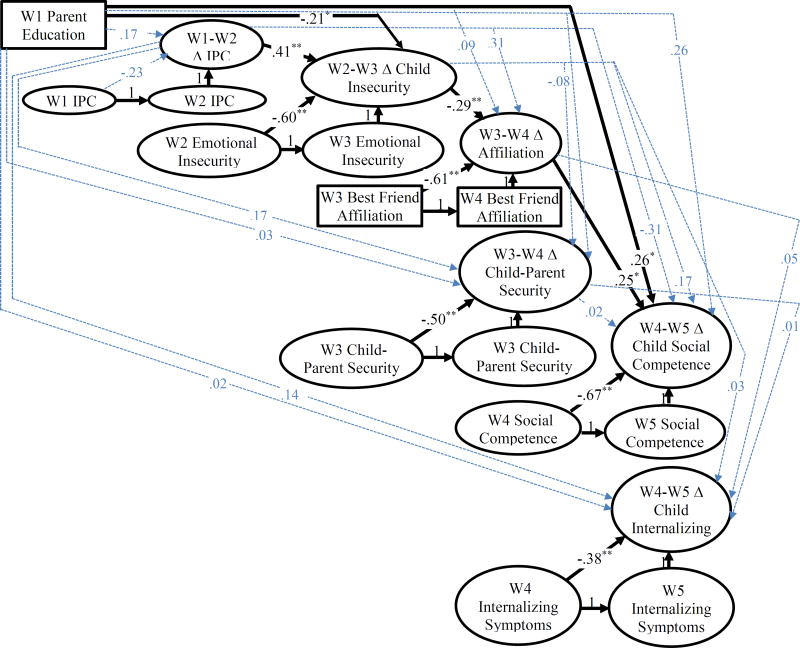

In highlighting its flexibility, the LDS approach allows for specification of LDS change scores as both predictors and endogenous variables (Brody, Yu, Chen, Beach, & Miller, 2016; Davies, Martin, & Cicchetti, 2012; Preacher & Selig, 2009; Toth, Sturge-Apple, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2015). Thus, as illustrated in Figure 2, LDS change in each upstream variable was specified as a predictor of successive change in each downstream variable. To test our set of primary hypotheses, we specifically estimated predictive paths running from LDS change in interparental conflict from Waves 1 to 2 to LDS changes in (a) children’s insecurity from Waves 2 to 3, (b) their best friendship affiliation from Waves 3 to 4, and (c) their social competence and internalizing symptoms from Waves 4 to 5. Fluctuations in children’s insecurity from Waves 2 to 3, in turn, served as a predictor of changes in their best friendship affiliation from Waves 3 to 4 and their changes in social competence and internalizing symptoms from Waves 4 to 5. In the last part of the cascade, we specified pathways running from changes in children’s best friendship affiliation across Waves 3 and 4 to fluctuations in their social competence and internalizing symptoms across Waves 4 and 5.

Figure 2.

Results of a latent difference score model testing whether changes in children’s emotional insecurity mediate the association between interparental conflict and children’s social competence by disrupting their friendship affiliation. For clarity, only structural paths are depicted in the figure. ** p < .01; * p < .05.

Three additional sets of specifications were also included in the model to increase the rigor of the analyses. First, given their potential role as covariates, child gender and Wave 1 family income and parent education were initially included as predictors of LDS change in each of the six downstream constructs. However, family income and gender failed to predict any of the variables or alter the significant findings. Therefore, for the sake of parsimony, only parental education level was included in the final analysis. Second, we examined whether changes in the saliency of affiliation in best friendships continued to mediate the unfolding cascade even after the inclusion of children’s security in the parent-child relationship as an alternative mechanism. Consistent with our treatment of best friendship affiliation, the covariates (i.e., family income, adolescent exposure to interparental conflict, adolescent insecurity) and changes in the upstream constructs (i.e., interparental conflict, children’s emotional security) were specified as predictors of changes in parent-child security from Waves 3 to 4. In turn, we examined whether changes in parent-child security predicted concomitant change in adolescent affiliation and subsequent change in their internalizing symptoms and social competence.

As part of the model specifications, we estimated correlations between (1) the latent constructs at each of their initial time points (i.e., Wave 1 interparental conflict, Wave 2 child insecurity, Wave 3 friendship affiliation, Wave 4 social competence, and Wave 4 academic competence); (2) each of the latent constructs at their initial time points and the covariate (i.e., parent education); and (3) the residuals of the concurrent LDS factors for social competence and internalizing symptoms. Due to the possible operation of method and informant variance for interparental conflict variables at Waves 1 and 2, we also specified correlations between error terms of comparable manifest indicators across those adjacent waves.

Results

Table 1 provides the means, standard deviations, and correlations for the main variables in the primary analyses. As denoted by the bolded coefficients in the table, correlations among the indicators of each of the higher-order, target constructs (i.e., interparental conflict, child insecurity, social competence, internalizing symptoms) were all significant (ps < .001), in the expected direction, and generally moderate in magnitude (M = .52).

Table 1.

Means, Standard deviations, and Correlations for the Primary Variables in the Analyses.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 Interparental Conflict | |||||||||||||||||

| 1. Mother Report | 0.00 | 0.86 | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Father Report | 0.01 | 0.86 | .57* | -- | |||||||||||||

| 3. Observational Rating | 0.00 | 0.69 | .41* | .40* | -- | ||||||||||||

| Wave 2 Interparental Conflict | |||||||||||||||||

| 4. Mother Report | 0.00 | 0.85 | .76* | .48* | .34* | -- | |||||||||||

| 5. Father Report | 0.00 | 0.86 | .55* | .78* | .38* | .58* | -- | ||||||||||

| 6. Observational Rating | 0.00 | 0.75 | .33* | .32* | .72* | .35* | .33* | -- | |||||||||

| Wave 2 Child Emotional Insecurity | |||||||||||||||||

| 7. Emotional Reactivity | 0.00 | 1.00 | .16* | .04 | .03 | .14* | .12 | −.03 | -- | ||||||||

| 8. Involvement | 0.00 | 1.00 | .06 | .00 | −.06 | .00 | .02 | −.03 | .46* | -- | |||||||

| 9. Avoidance | 0.00 | 1.00 | .14* | .08 | .07 | .12 | .14* | .01 | .68* | .37* | -- | ||||||

| Wave 3 Child Emotional Insecurity | |||||||||||||||||

| 10. Emotional Reactivity | 0.00 | 1.00 | .00 | −.01 | −.02 | .09 | .10 | .06 | .26* | .23* | .21* | -- | |||||

| 11. Involvement | 0.00 | 1.00 | .18* | .21* | .04 | .18* | .21* | .11 | .20* | .23* | .14 | .42* | -- | ||||

| 12. Avoidance | 0.00 | 1.00 | .03 | −.03 | −.01 | .05 | .08 | .10 | .12 | .15* | .15 | .65* | .31* | -- | |||

| Wave 3 Teen Friendship Affiliation | |||||||||||||||||

| 13. Composite | 3.62 | 1.05 | −.03 | −.07 | −.13 | .07 | −.05 | −.04 | −.07 | −.04 | −.14 | .04 | −.18* | .01 | -- | ||

| Wave 4 Teen Friendship Affiliation | |||||||||||||||||

| 14. Composite | 3.24 | 1.03 | .01 | .02 | −.19* | .06 | .07 | −.07 | .09 | .07 | .01 | −.19* | −.15 | −.26* | .25* | -- | |

| Wave 3 Security in Parent-Child Relationship | |||||||||||||||||

| 15. Child PARQ | 82.51 | 13.45 | −.16* | −.14* | .01 | −.08 | −.13 | −.10 | .07 | .04 | .02 | −.09 | .04 | −.17* | .14 | .10 | -- |

| 16. Child PASS | 51.78 | 8.07 | −.19* | −.20* | −.13 | −.08 | −.14 | −.14 | .09 | .02 | −.02 | −.10 | −.02 | −.15* | .05 | .11 | .84* |

| Wave 4 Security in Parent-Child Relationship | |||||||||||||||||

| 17. Child PARQ | 82.97 | 12.31 | −.08 | −.19* | −.10 | −.02 | −.17* | −.08 | .07 | .13 | .04 | −.03 | .02 | −.03 | −.02 | .11 | .60* |

| 18. Child PASS | 50.72 | 7.94 | −.19* | −.32* | −.16* | −.07 | −.25* | −.00 | .10 | .09 | .01 | .03 | .03 | .05 | .01 | .05 | .48* |

| Wave 4 Teen Social Competence | |||||||||||||||||

| 19. TRSCAB Competence | 6.15 | 1.66 | −.03 | −.05 | −.07 | −.05 | −.01 | .01 | −.14 | −.08 | −.26* | −.05 | −.01 | −.02 | .18* | .12 | .17* |

| 20. CBS Prosocial | 10.43 | 3.46 | −.04 | −.04 | −.11 | −.08 | −.02 | −.13 | −.11 | −.10 | −.23* | −.08 | −.08 | .04 | .25* | .17 | .21* |

| Wave 5 Teen Social Competence | |||||||||||||||||

| 21. TRSCAB Competence | 6.06 | 1.56 | .03 | .06 | .12 | .08 | .00 | .22* | −.14 | −.09 | −.16* | −.04 | −.00 | −.09 | .00 | .13 | .17* |

| 22. CBS Prosocial | 10.30 | 3.23 | −.06 | .01 | .03 | −.13 | −.11 | .00 | −.29* | −.11 | −.24* | −.24* | −.11 | −.20* | .06 | .14 | .01 |

| Wave 4 Child Internalizing Symptoms | |||||||||||||||||

| 23. RCMAS | 8.37 | 5.92 | .00 | .07 | −.04 | −.03 | .00 | −.12 | .10 | .15* | .12 | .31* | .17* | .28* | −.04 | −.04 | −.25* |

| 24. CES-D | 30.66 | 8.41 | −.03 | −.01 | −.04 | .00 | −.05 | .00 | .15 | .13 | .19* | .34* | .32* | .25* | −.02 | .03 | −.27* |

| 25. SDQ | 2.12 | 2.14 | .02 | .02 | −.10 | .05 | −.02 | −.08 | .07 | .06 | .11 | .27* | .16* | .28* | .03 | .02 | −.28* |

| Wave 5 Teen Internalizing Symptoms | |||||||||||||||||

| 26. RCMAS | 8.54 | 5.47 | .01 | .02 | −.05 | .04 | .03 | −.11 | .11 | .11 | .08 | .23* | .16* | .20* | .00 | −.01 | −.28* |

| 27. CES-D | 31.04 | 8.90 | .00 | −.05 | −.06 | .02 | −.05 | −.07 | .14 | .11 | .14 | .29* | .19* | .20* | −.09 | −.15 * | −.28 |

| 28. SDQ | 2.34 | 2.18 | −.03 | −.05 | −.17* | −.02 | −.07 | −.15* | .07 | .08 | .03 | .18* | .05 | .23* | .01 | .08 * | −.26 |

| Covariates | |||||||||||||||||

| 29. W1 Parent Education | 14.51 | 2.19 | −.02 | −.12 | −.28* | .03 | −.05 | −.14* | −.17* | −.11 | −.12 | −.14 | −.24* | −.10 | .15* | .10 | .06 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 4 Security in Parent-Child Relationship | |||||||||||||

| 17. Child PARQ | .55* | -- | |||||||||||

| 18. Child PASS | .51* | .78* | − | ||||||||||

| Wave 4 Teen Social Competence | |||||||||||||

| 19. TRSCAB Competence | .14 | .18* | .06 | -- | |||||||||

| 20. CBS Prosocial | .27* | .14 | .19* | .60* | -- | ||||||||

| Wave 5 Teen Social Competence | |||||||||||||

| 21. TRSCAB Competence | .11 | .08 | −.09 | .46* | .14 | -- | |||||||

| 22. CBS Prosocial | −.02 | .08 | −.01 | .34* | .32* | .42* | -- | ||||||

| Wave 4 Child Internalizing Symptoms | |||||||||||||

| 23. RCMAS | −.27* | −.24* | −.25* | −.22* | −.17* | −.08 | .00 | -- | |||||

| 24. CES-D | −.26* | −.32* | −.24* | −.17* | −.14 | −.14 | −.15 | .62* | -- | ||||

| 25. SDQ | −.35* | −.19* | −.18* | −.23* | −.16 | −11 | −.04 | .72* | .58* | -- | |||

| Wave 5 Teen Internalizing Symptoms | |||||||||||||

| 26. RCMAS | −.31* | −.27* | −.18* | −.14 | −.01 | −.22* | −.06 | .63 | .49* | .55* | -- | ||

| 27. CES-D | −.31* | −.33* | −.22* | −.18* | −.15 | −.22* | −.16* | .45* | .61* | .43* | .61* | -- | |

| 28. SDQ | −.31* | −.12 | −.09 | −.14 | −.06 | −.27* | −.03 | .57* | .46* | .61* | .63* | .60* | -- |

| Covariates | |||||||||||||

| 29. W1 Parent Education | .09 | .13 | .05 | .15 | .19* | .16* | .29* | −.17* | −.22* | −.17* | −.13 | −.16* | −.08 |

Note. p ≤ .05

Primary Results of the LDS Cascade Analyses

The model described in the analysis plan provided a good representation of the data, χ2(338, N = 235) = 513.84, p < .001, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .93, and χ2/df ratio = 1.52. For ease of presentation, the standardized loadings of the manifest indicators onto their latent constructs are presented in Table 2. In support of the measurement model, the loadings were all significant (p < .001) and generally moderate to high in magnitude (mean absolute value for loadings = .75). Figure 2, in turn, depicts the results of all the estimated structural paths for the primary analyses. Although the covariances specified among the constructs are not depicted in the Figure for clarity, a comprehensive supplementary table of all the covariances estimated in the model can be found in the Electronic Appendix.

Table 2.

Standardized loadings for the latent constructs in the analyses depicted in Figure 2.

| Latent Construct | Manifest Indicator | Loadings |

|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 Interparental Conflict | ||

| Maternal Report Composite | .75 | |

| Paternal Report Composite | .76 | |

| Observational Composite | .54 | |

| Wave 2 Interparental Conflict | ||

| Maternal Report Composite | .74 | |

| Paternal Report Composite | .76 | |

| Observational Composite | .48 | |

| Wave 2 Child Emotional Insecurity | ||

| SIS-YC Emotional Reactivity | .91 | |

| SIS-YC Avoidance | .74 | |

| SIS-YC Involvement | .50 | |

| Wave 3 Child Emotional Insecurity | ||

| SIS Emotional Reactivity | .91 | |

| SIS Avoidance | .72 | |

| SIS Involvement | .48 | |

| Wave 3 Parent-Child Insecurity | ||

| PASS | .91 | |

| PARQ | .92 | |

| Wave 4 Parent-Child Insecurity | ||

| PASS | .84 | |

| PARQ | .93 | |

| Wave 4 Child Internalizing Symptoms | ||

| RCMAS | .85 | |

| CES-D | .75 | |

| SDQ | .83 | |

| Wave 5 Child Internalizing Symptoms | ||

| RCMAS | .83 | |

| CES-D | .71 | |

| SDQ | .79 | |

| Wave 4 Social Competence | ||

| TRSCAB Social Competence | .86 | |

| CBS Prosocial with Peers | .70 | |

| Wave 5 Social Competence | ||

| TRSCAB Social Competence | .69 | |

| CBS Prosocial with Peers | .60 |

In examining structural paths of the covariates, parent education at Wave 1 was a significant predictor of higher levels of interparental conflict during adolescence, decreases in security in the parent-child relationship from Waves 3 to 4, and increases in social competence from Waves 4 to 5. Interparental conflict during adolescence failed to predict change in any of the friendship affiliation, parent-child security, social competence, or internalizing symptoms. Examination the structural path involving teen emotional insecurity and these same constructs revealed one significant pathway: teen insecurity at Wave 4 and 5 was a significant predictor of their increases in internalizing symptoms from Waves 4 to 5. As a potential alternative mechanism, changes in security in the parent-child relationship from Waves 3 to 4 were unrelated to earlier fluctuations in interparental conflict or children’s emotional insecurity. In addition, parent-child security failed to predict subsequent Wave 4 to 5 changes in social competence or internalizing symptoms.

Even with the inclusion of the alternative pathways involving the covariates and insecurity in the parent-child relationship, the results of the remaining structural paths were consistent with hypotheses. More specifically, LDS increases in interparental conflict from Waves 1 (6 years old) to 2 (7 years old) significantly predicted increases in children’s emotional insecurity from Waves 2 (7 years old) to 3 (13 years old), β = .41, p = .001. The resulting LDS increase in children’s insecurity from 7 to 13 years old, in turn, was a significant predictor of decreases in best friendship affiliation from Waves 3 (13 years old) to 4 (14 years old), β = −.29, p = .003. In the final part of the hypothesized cascade, decreases in children’s best friendship affiliation from Waves 3 (13 years old) to 4 (14 years old) predicted subsequent decreases in their social competence from Waves 4 (14 years old) to 5 (15 years old), β = .25, p = .03. In contrast, the comparable path running from change in friendship affiliation to subsequent fluctuations in adolescent internalizing symptoms was not significant, β = .05, p = .70.

Tests of Indirect Paths in the LDS Cascade

Our findings on the multi-chain cascade of processes involving emotional insecurity can be further dichotomized into two interlocking indirect pathways. In the first part of the cascade, increases in Wave 2 to Wave 3 child insecurity is hypothesized to mediate the prospective association between increases in interparental conflict from Waves 1 to 2 and decreases in best friendship affiliation from Waves 3 to 4. In support of this mediational hypothesis, bootstrapping tests of the indirect path involving changes in interparental conflict, children’s insecurity, and their friendship affiliation was significantly different from zero, with the unstandardized coefficient for the indirect path = −.55, 95% CI [−.138, −1.110] (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007). In the second part of the cascade, we also tested the hypothesis that decreases in best friendship affiliation from Waves 3 to 4 mediated the prospective association between rises in child insecurity from Waves 2 to 3 and decreases in their social competence from Waves 4 to 5. Supporting this proposed pathway, the results of the bootstrapping tests indicated that the mediational link involving children’s insecurity, their best friendship affiliation, and their social competence was also significantly different from 0, with the unstandardized path coefficient for the indirect path = −.06, 95% CI [−.005, −.161]. In highlighting the possible specificity in this final part of the cascade, bootstrapping tests of the comparable indirect path involving children’s insecurity, best friendship affiliation, and internalizing symptoms was not significantly different from zero, with the unstandardized path coefficient for the indirect path = .03, 95% CI [−.136, .217].

Alternative Tests of Static Levels of Constructs in the Cascade

Although the analyses provide support for the value of examining emotional security pathways within more dynamic approaches to quantifying change, it is possible that the results indexing links between changes in interparental conflict, security, and social processes may be an artifact of the static levels of each construct. To control for this possibility, we re-ran the model in Figure 2 with the inclusion of structural paths running from static levels of: (1) interparental conflict at Wave 2 to changes in emotional insecurity from Waves 2 to 3; (2) emotional insecurity at Wave 3 to changes in friendship affiliation from Waves 3 to 4; and (3) friendship affiliation at Wave 4 to changes in adolescent social competence and internalizing symptoms from Waves 4 to 5. The results did not support this alternative possibility as none of the links necessary to support mediation were significant. First, static levels of interparental conflict at Wave 2 failed to predict subsequent changes in emotional insecurity from Waves 2 to 3, β = .03, p = .72. Likewise, Wave 3 emotional insecurity was unrelated to changes in friendship affiliation from Waves 3 to 4, β = −.20, p = .09. In turn, static levels of friendship affiliation at Wave 4 failed to predict adolescent social competence at Wave 4, β = .04, p = .80. In addition, the proposed cascade of changing processes remained significant after controlling for the static levels of the predictors. Thus, increases in interparental conflict form Waves 1 to 2 continued to predict subsequent rises in emotional insecurity from Waves 2 to 3, β = .44, p = .001. These increases in emotional insecurity, in turn, were associated with subsequent decreases in friendship affiliation from Waves 3 to 4, β = −.25, p = .02. Finally, the resulting reductions in friendship affiliation significantly predicted lagged decreases in social competence from Waves 4 to 5, β = .27, p < .05. Consistent with the original analyses, bootstrapping tests of the two indirect paths in the cascade were significantly different from 0, including paths involving changes in: (1) interparental conflict, children’s insecurity, and their friendship affiliation, −.52, 95% CI [−1.139, −.076]; and (2) children’s insecurity, friendship affiliation, and social competence, −.06, 95% CI [−.156, −.001]. Thus, the findings indicate that our identification of linkages involving cascading changes in interparental conflict, emotional insecurity, diminished affiliation, and impairments in social competence is not simply a byproduct of static levels of the variables as predictors of downstream variables in the model.

Discussion

Although interparental conflict is a risk factor for the development of children’s social difficulties, there is limited understanding of the intermediary mechanisms that underlie this association. In addressing this gap, EST-R proposes that children’s heightened emotional insecurity in the face of interparental conflict increases children’s social problems by undermining their affiliation in close friendships (Davies & Martin, 2013). Consistent with this hypothesis, our longitudinal results indicated that the mediational role of children’s insecurity in associations between interparental conflict and their social problems was further mediated by the devaluation of affiliation in best friendships. Moreover, as conceptualized in the risky families model (Repetti et al., 2011), the results of our lagged latent difference score analyses further supported the notion that the unfolding insecurity cascade resembles a series of interlocking, shifting gears. Upward shifts in interparental conflict during the early school years predicted subsequent increases in children’s emotional insecurity into early adolescence. Dynamic change in emotional insecurity, in turn, predicted decreases in adolescents’ representations of friendship affiliation over time. In the final part of the cascade, downward shifts in friendship affiliation predicted subsequent increases in adolescent social problems. Finally, the specificity of this cascade of changing processes in predicting social problems was supported by the robustness of the findings after inclusion of change in secure parent-child relationships as an alternative mediating mechanism, increases in internalizing symptoms as an alternative outcome, and static levels of each of these constructs.

In regards to the first hypothesized link in the cascade, our results are broadly consistent with the sensitization hypothesis and its derivative prediction that experiential histories of interparental conflict progressively intensify children’s emotional and behavioral distress in the face of subsequent interparental conflicts (e.g., David & Murphy, 2004 Goeke-Morey et al., 2013; Grych, 1998). However, theory and research on sensitization has yet to authoritatively identify how this developmental process unfolds over time. A tacit assumption in the literature is that exposure to destructive conflict within any static time window may incrementally increase children’s distress responses to conflict. However, questions can be raised about the plausibility of this premise. If sensitization operated in a uniform, incremental way with exposure to each interparental conflict across temporal spans of family risk exposure, then children from chronically discordant homes would eventually respond in exceedingly distressing and dysregulating ways to the even slightest forms of adversity. Thus, it may not be that each exposure to interparental conflict is carrying the significant weight as a risk factor. Rather, it is plausible that change in the form of intensification of interparental conflict over time predicts subsequent increases in insecurity. In beginning to address this unresolved issue, our findings underscore that change (i.e., intensification) in children’s exposure to interparental conflict during the early school years was a robust predictor of subsequent increases in their emotional insecurity from childhood into adolescence even after taking into account static levels of conflict between parents. Our results are consistent with a recent study indicating that increases in interparental conflict were associated concomitant rises in distress reactions to interparental conflict (Goeke-Morey et al., 2013). Moreover, the lagged analyses in the present study suggest that the concomitant relationship between interparental conflict and children’s distress reactions to conflict reflect, in part, a temporal relationship whereby changes in interparental conflict predict subsequent changes in children’s emotional insecurity. Thus, in illustrating developmental plasticity and resilience, our findings support the notion that parental efforts to reduce destructive conflicts during childhood may confer long-term benefits for children in the form reductions in their insecure responses to conflicts over the course of childhood and adolescence.

In support of the remaining parts of the hypothesized cascade, increases in children’s insecurity over a six-year period from middle childhood to early adolescence predicted subsequent decreases in the valuation of their affiliation in best friendships over the course of a year even after taking into account static levels of emotional insecurity during adolescence. Decreasing valuation of affiliation in best friendships, in turn, was associated with later reductions in social competence during middle adolescence (Davies & Martin, 2013). The bases for this developmental cascade are rooted in the concept of behavioral systems. Within evolutionary frameworks, behavioral systems are designed to emotionally incentivize individuals toward specific behavioral goals that promoted fitness in our evolutionary past (West-Eberhardt, 2003). According to EST-R, children’s insecure responses (i.e., emotional reactivity, avoidance, involvement) to interparental conflict are manifestations of a highly salient social defense system and its evolved function of defusing and defending against interpersonal threats. The defensive, inhibitory nature of the system, in turn, is further proposed to indirectly shape trajectories of social competence by interfering with the development of the approach-driven affiliative system. With its function of garnering access to survival materials and social standing through the formation and maintenance of cooperative alliances, the affiliative system is specifically designed to promote and sustain social interactions (Irons & Gilbert, 2005; Markiewicz, Doyle, & Brendgen, 2001).

Under supportive environmental conditions, best friendships during early adolescence are theorized to serve as relatively comfortable, manageable, and safe contexts for the development and refinement of skills that support social competent behaviors (e.g., disclosure, trust, shared affect and activities, prosocial behavior). However, attenuated motivational investment in affiliative goals in best friendships is theorized to increase peer and social difficulties by undermining the development and refinement of social skills, trust, motivation to develop cooperative relationships, and expectancies of reciprocation in broader social interpersonal circles (Davies & Martin, 2013; Lindsey et al., 2009). For example, diminished affiliative motivations may result in adolescents increasingly distancing themselves from peers, further increasing their social difficulties (Martin, Davies, & Cummings, in press). Thus, within EST-R, the disruptive role of insecurity on this affiliative process is proposed to proliferate into poorer social competence within broader peer contexts.

Because the achievement of social standing is the ultimate goal of the motivational processes comprising the affiliative system, EST-R specifically hypothesizes that reductions in its salience in close friendships should specifically lay the foundation for subsequent declines in social functioning even in the context of other operative processes and sequelae (Davies & Martin, 2013). Consistent with this thesis, reductions in friendship affiliation rather than security in the parent-child relationship was the significant intermediary mechanism in the link between earlier increases in emotional insecurity and later declines in social competence. Likewise, although emotional insecurity has been repeatedly linked with internalizing symptoms, this indirect cascading process specifically accounted for individual differences in changes in social functioning rather than emotional problems. Thus, these findings highlight that the mediational pathways involving disruptions in friendship affiliation are not simply part of a broad, intrinsically negative set of characteristics that are associated with a wide array of undesirable or detrimental outcomes (Ellis et al., 2012; Frankenhuis & Del Giudice, 2012). Rather, the pathway is distinctive in explaining how and why children with histories of interparental conflict and insecurity specifically develop social problems.

Several limitations and future directions also merit discussion for a balanced interpretation of our findings. First, although there was some diversity in racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds of the families in our study, our community sample was largely White and generally from middle class upbringings. Therefore, our findings may not necessarily generalize to families from higher risk or more diverse backgrounds. Second, our findings do not address the possibility of bidirectional associations among interparental conflict, children’s reactivity to interparental conflict, and their broader indices of functioning (e.g., Cui, Donnelan, & Conger, 2007; Schermerhorn, Cummings, DeCarlo, & Davies, 2007). Third, differences in the developmental levels of children across the two waves of insecurity assessments required the use of different versions of the emotional security scales. Thus, questions may be raised about measurement equivalence across the two developmental periods. However, these concerns may be allayed by prior evidence of the developmental comparability of the two versions of security scales and our findings indicating that change in the indices were lawfully related to prior exposure to interparental conflict and subsequent decreases in friendship affiliation and (Davies et al., 2014). Fourth, due to the timing and spacing of the available assessments in our study, we had no other option than to assess change in children’s emotional insecurity over a much longer span (i.e., six years) than the smaller one-year gaps in the assessments of change in the other constructs. Although the timing of the assessments were guided by developmental models and our findings were robust even after inclusion of covariates, alternative mechanisms, and static levels of the target constructs as predictors in the analyses, the wide temporal span increases the possibility that other processes may be accounting for part of the cascade. Given the complexity and timing of our change analyses, replication is necessary for drawing more definitive conclusions about the dynamic processes of insecurity.

Finally, although our identification of a developmental cascade linking interparental conflict and social difficulties supports emotional security theory, tracing other explanatory pathways is an important direction for future research. At one level, the modest to moderate magnitude of the pathways in the emotional security cascade underscores the need to expand beyond insecurity and friendship affiliation in searching for mediating mechanisms. For example, researchers have identified multiple additional explanatory processes that may underlie links between interparental conflict and social difficulties, including poor emotion understanding in family interactions (Parke et al., 2001), negative cognitive appraisals of relationships (Kinsfogel & Grych, 2004), and social learning mechanisms such as vicarious modeling (Jouriles, McDonald, & Kouros, 2016; Goodman et al., 1999). Likewise, the strength of the documented pathways also highlights the importance of identifying potential protective factors (e.g., supportive sibling relationships, parent-child relationship quality) that may buffer children from the experiencing the unfolding pathogenic precursors of their social difficulties. At another level, the cascading mechanisms of insecurity and friendship affiliation may also serve as explanatory mechanisms in the linkages between children’s exposure to other forms of interpersonal threat (e.g., child maltreatment, parent-child conflict, and peer rejection) and their social difficulties. Consistent with this possibility, EST-R proposes that children’s emotional insecurity is organized by a behavioral system that is exquisitely designed to neutralize threat in social relationships and, as a result, is more broadly applicable to threat in multiple social contexts (Davies et al., 2016).

In summary, although social difficulties have been identified as sequelae of children’s experiences with interparental conflict and insecurity, there is limited understanding of the distinctive mechanisms that specifically account for their vulnerability to social problems. Guided by EST-R, this study tested the hypothesis that the dampened salience of affiliation goals in best friendships was a key explanatory process in the mediational pathways (Davies & Martin, 2013). Consistent with the theory, our results supported the hypothesis that children’s emotional insecurity mediates prospective associations between interparental conflict and their social problems by specifically undermining their affiliation goals in best friendships. At a broader level, our identification of sequential linkages of change in interparental conflict, children’s insecurity, dampened friendship affiliation, and social competence underscore the value of conceptualizing and analyzing family risk cascades as a series of unfolding, dynamic processes. Drawing on the gear metaphor of risky families model (Repetti et al., 2011), our findings specifically suggest that the pathways linking family processes and child functioning may best be conceptualized as resembling a series of interlocking, shifting gears. As a potentially hopeful implication, this dynamic conceptualization not only elucidates how increases in interparental conflict and insecurity may give rise to child problems, but it also suggests that the “shifting gears” are reversible. That is, downward shifts in exposure to interparental conflict over time also set the stage for ensuing reductions in children’s emotional insecurity and, in turn, upward swings in friendship affiliation and social competence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health awarded to Patrick T. Davies and E. Mark Cummings (R01 MH57318 & 2R01 MH57318). We are grateful to the children, parents, teachers, and school administrators who participated in this project. Our gratitude is expressed to the staff on the project and the graduate and undergraduate students at the Universities of Rochester and Notre Dame.

Contributor Information

Patrick T. Davies, Department of Clinical and Social Sciences in Psychology, University of Rochester

Meredith J. Martin, Department of Clinical and Social Sciences in Psychology, University of Rochester

E. Mark Cummings, Department of Psychology, University of Notre Dame.

References

- Achenbach TM. Child behavior checklist/4–18. University of Vermont, psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Schmidt ME. Friendships in childhood and adolescence. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barry CM, Wentzel KR. Friend influence on prosocial behavior: The role of motivational factors and friendship characteristics. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:153–163. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn CS, Haynes OM. Social competence, externalizing, and internalizing behavioral adjustment from early childhood through early adolescence: Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:717–735. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock RL, Kochanska G. Interparental conflict, children’s security with parents, and long-term risk of internalizing problems: A longitudinal study from ages 2 to 10. Development and Psychopathology. 2016;28:45–54. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Yu T, Chen E, Beach SRH, Miller GE. Family-centered prevention ameliorates the longitudinal association between risky family processes and epigenetic aging. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2016;57:566–574. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D. Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development. 1990;61:1101–1111. doi: 10.2307/1130878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Simard M, Dubois M, Lopez L. Representations, process, and development: A new look at friendship in early adolescence. In: Amsel E, Smetana J, editors. Adolescent vulnerabilities and opportunities: Developmental and constructivist perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011. pp. 59–181. [Google Scholar]

- Burt KB, Obradović J, Long JD, Masten AS. The interplay of social competence and psychopathology over 20 years: Testing transactional and cascade models. Child Development. 2008;79:359–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, Greenberg MT, Marvin RS. An organizational perspective on attachment beyond infancy: Implications for theory, measurement, and research. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research and intervention. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Mills-Koonce R, Propper C, Gariépy JL. Systems theory and cascades in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:497–506. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribbie RA, Jamieson J. Structural equation models and the regression bias for measuring correlates of change. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2000;60:893–907. doi: 10.1177/00131640021970970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Conger RD, Lorenz FO. Predicting change in adolescent adjustment from change in marital problems. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:812–823. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Donnellan MB, Conger RD. Reciprocal influences between parents’ marital problems and adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1544–1552. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Miller-Graff LE. Emotional security theory: An emerging theoretical model for youths’ psychological and physiological responses across multiple developmental contexts. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2015;24:208–213. doi: 10.1177/0963721414561510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Dukewich TL. The study of relations between marital conflict and child adjustment: Challenges and new directions for methodology. In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Child development and interparental conflict. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Schermerhorn AC, Davies PT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings JS. Interparental discord and child adjustment: Prospective investigations of emotional security as an explanatory mechanism. Child Development. 2006;77:132–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David KM, Murphy BC. Interparental conflict and late adolescents’ sensitization to conflict: The moderating effects of emotional functioning and gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Coe JL, Martin MJ, Sturge-Apple ML, Cummings EM. The developmental costs and benefits of children’s involvement in interparental conflict. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51:1026–1047. doi: 10.1037/dev0000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Harold GT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM, Shelton K, Rasi JA, Jenkins JM. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67 i-127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Martin MJ. The reformulation of emotional security theory: The role of children’s social defense in developmental psychopathology. Development & Psychopathology. 2013;25:1435–1454. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Martin MJ, Cicchetti D. Delineating the sequelae of destructive and constructive interparental conflict for children within an evolutionary framework. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48:939–955. doi: 10.1037/a0025899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Martin MJ, Coe JL, Cummings EM. Transactional cascades of destructive interparental conflict, children’s emotional insecurity, and psychological problems across childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. doi: 10.1017/S0954579416000237. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, *Martin MJ, Sturge-Apple ML. Emotional security theory and developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Developmental Psychopathology: Vol. 1. Theory and Methods. 3. New York: Wiley; 2016. pp. 199–264. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Bascoe SM, Cummings EM. The legacy of early insecurity histories in shaping adolescent adaptation to interparental conflict. Child Development. 2014;85:338–354. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]