Abstract

AIM

To evaluate the relation between 12 polymorphisms and the development of gastric cancer (GC) and colorectal cancer (CRC).

METHODS

In this study, we included 125 individuals with GC diagnosis, 66 individuals with CRC diagnosis and 475 cancer-free individuals. All participants resided in the North region of Brazil and authorized the use of their samples. The 12 polymorphisms (in CASP8, CYP2E1, CYP19A1, IL1A, IL4, MDM2, NFKB1, PAR1, TP53, TYMS, UGT1A1 and XRCC1 genes) were genotyped in a single PCR for each individual, followed by fragment analysis. To avoid misinterpretation due to population substructure, we applied a previously developed set of 61 ancestry-informative markers that can also be genotyped by multiplex PCR. The statistical analyses were performed in Structure v.2.3.4, R environment and SPSS v.20.

RESULTS

After statistical analyses with the control of confounding factors, such as genetic ancestry, three markers (rs79071878 in IL4, rs3730485 in MDM2 and rs28362491 in NFKB1) were positively associated with the development of GC. One of these markers (rs28362491) and the marker in the UGT1A1 gene (rs8175347) were positively associated with the development of CRC. Therefore, we investigated whether the joint presence of the deleterious alleles of each marker could affect the development of cancer and we obtained positive results in all analyses. Carriers of the combination of alleles RP1 + DEL (rs79071878 and rs28361491, respectively) are at 10-times greater risk of developing GC than carriers of other combinations. Similarly, carriers of the combination of DEL + RARE (rs283628 and rs8175347) are at about 12-times greater risk of developing CRC than carriers of other combinations.

CONCLUSION

These findings are important for the comprehension of gastric and CRC development, particularly in highly admixed populations, such as the Brazilian population.

Keywords: Inflammatory processes, Immune response, Genomic and cellular stability, Gastric cancer, Colorectal cancer, Amazon

Core tip: Gastric cancer and colorectal cancer (CRC) are among the most incident and aggressive types of cancer in Brazil, especially in the Amazon region. Alterations in genes involved in pathways of immune responses, inflammatory processes or genomic and cellular stability may generate cellular imbalances and lead to tumorigenesis. Therefore, it is vital to understand the effect of different alleles in the development of gastric and CRC, which could contribute to the early detection of these types of cancer, increasing the survival chances of the patient.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is one of the main causes of death worldwide[1]. In Brazil, it is considered a severe problem of public health, and in the North region of this country gastric cancer (GC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) are among the three most incident and aggressive types of cancer[2].

Carcinogenesis is a multifactorial process. Gastritis and colitis have been related to the development of GC[3,4] and CRC[5,6], respectively, but they are not determinant. Infection by Helicobacter pylori, one of the most common human infectious agents, is also very important for the development of gastritis and GC[7]. However, it should not be considered the only cause for development of this type of cancer[8]. Genetics also play a major role in the carcinogenesis, and there is much to be discovered regarding this subject.

Genes involved in important pathways, such as inflammatory processes, metabolism of carcinogens, cell stability and hormonal pathways, are possible susceptibility factors to cancer[9-14]. Alterations in these genes may generate imbalances in such pathways and trigger tumor development. In this study, we investigated the following 12 polymorphisms of important genes of these pathways: CASP8 (rs3834129), CYP2E1 (96 bp-deletion), CYP19A1 (rs11575899), IL1A (rs3783553), IL4 (rs79071878), MDM2 (rs3730485), NFKB1 (rs28362491), PAR1 (rs11267092), TP53 (rs17878362), TYMS (rs16430), UGT1A1 (rs8175347) and XRCC1 (rs3213239).

These genes and polymorphisms have been studied in association with various types of cancer in different populations, e.g, breast cancer[15-19], bladder cancer[20], endometrial cancer[21], acute lymphoblastic leukemia[22], chronic lymphoblastic leukemia[23], oral carcinoma[24,25], lung cancer[26], nasopharyngeal cancer[27], thyroid cancer[28], hepatocellular carcinoma[29], GC[30-39] and CRC[40-50]. Therefore, these markers were chosen based on the importance of each gene as a potential influencing factor in the susceptibility of tumor development. All are functional polymorphisms that correspond to insertion/deletion (INDEL) of small DNA fragments and can be analyzed in a single multiplex PCR, which makes it a cheap and accessible methodology that could be used in different laboratories worldwide.

Thus, the aim of this work was to investigate the association between 12 polymorphisms in genes related to pathways of immune/inflammatory response (CYP2E1, CYP19A1, IL1A, IL4, NFKB1 and PAR1) and cellular or genomic stability (CASP8, MDM2, TP53, TYMS, UGT1A1 and XRCC1) and the development of GC and CRC in a population in Northern Brazil. In addition, we investigated the influence of genetic ancestry in the development of these types of cancer in the studied population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples

In this study, we included three groups: (1) 125 individuals with GC diagnosis; (2) 66 individuals with CRC diagnosis; and (3) 475 cancer-free individuals that were considered the control group. The cancer-free individuals did not have personal or familial histories of any kind of cancer and they did not show any symptoms or signs of cancer. All participants resided in Belém, which is a city located in the Northern region of Brazil, and signed an informed consent, with approval by the Committee for Research Ethics of Hospital João de Barros Barreto under Protocol No. CAAE 25865714.6.0000.0017.

DNA Extraction and Quantification

Samples of peripheral blood were collected from all individuals of the study and the DNA extraction was performed accordingly[51]. DNA quantification was performed with NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, United States).

Genotyping

Samples were then submitted to multiplex PCR and fragment analysis in an ABI PRISM 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) according to the protocol described[22]. Technical characteristics of the studied markers are presented in Table 1. Due to the high level of genetic admixture in the studied population, we applied a panel of 61 ancestry-informative markers to avoid misinterpretations caused by population substructure, as described[52,53].

Table 1.

Technical characteristics of the studied markers

| Gene | ID | Type | Length, bp | Primers | Amplicon, bp |

| CASP8 | rs3834129 | INDEL | 6 | F-5’CTCTTCAATGCTTCCTTGAGGT3’ | 249-255 |

| R-5’CTGCATGCCAGGAGCTAAGTAT3’ | |||||

| CYP2E1 | - | INDEL | 96 | F-5’TGTCCCAATACAGTCACCTCTTT3’ | 303-399 |

| R-5’GGCTTTTATTTGTTTTGCATCTG3’ | |||||

| CYP19A1 | rs11575899 | INDEL | 3 | F-5’TGCATGAGAAAGGCATCATATT3’ | 122-125 |

| R-5’AAAAGGCACATTCATAGACAAAAA3’ | |||||

| IL1A | rs3783553 | INDEL | 4 | F-5’TGGTCCAAGTTGTGCTTATCC3’ | 230-234 |

| R-5’ACAGTGGTCTCATGGTTGTCA3’ | |||||

| IL4 | rs79071878 | VNTR | 70 | F-5’AGGGTCAGTCTGGCTACTGTGT3’ | 147/217/287 |

| R-5’CAAATCTGTTCACCTCAACTGC3’ | |||||

| MDM2 | rs3730485 | INDEL | 40 | F-5’GGAAGTTTCCTTTCTGGTAGGC3’ | 192-232 |

| R-5’TTTGATGCGGTCTCATAAATTG3’ | |||||

| NFKB1 | rs28362491 | INDEL | 4 | F-5’TATGGACCGCATGACTCTATCA3’ | 366-370 |

| R-5’GGCTCTGGCATCCTAGCAG3’ | |||||

| PAR1 | rs11267092 | INDEL | 13 | F-5’AAAACTGAACTTTGCCGGTGT3’ | 265-277 |

| R-5’GGGCCTAGAAGTCCAAATGAG3’ | |||||

| TP53 | rs17878362 | INDEL | 16 | F-5’GGGACTGACTTTCTGCTCTTGT3’ | 148-164 |

| R-5’GGGACTGTAGATGGGTGAAAAG3’ | |||||

| TYMS | rs16430 | INDEL | 6 | F-5’ATCCAAACCAGAATACAGCACA3’ | 213-219 |

| R-5’CTCAAATCTGAGGGAGCTGAGT3’ | |||||

| UGT1A1 | rs8175347 | VNTR | 2 | F-5’CTCTGAAAGTGAACTCCCTGCT3’ | 133/135/137/139 |

| R-5’AGAGGTTCGCCCTCTCCTAT3’ | |||||

| XRCC1 | rs3213239 | INDEL | 4 | F-5’GAACCAGAATCCAAAAGTGACC3’ | 243-247 |

| R-5’AGGGGAAGAGAGAGAAGGAGAG3’ |

F: Forward; INDEL: Insertion/deletion; R: Reverse; VNTR: Variable number tandem repeat.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with different programs. Ancestry analyses were performed in Structure v.2.3.4[54], and tests concerning the genotyping analyses (Student’s t-test, Pearson’s χ2 test, Mann-Whitney test and logistic regression) were performed in R[55] and in SPSS v.20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

The genotype distribution was assessed as established by Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), with post-test correction by the Bonferroni method for multiple tests. P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

All population distributions were according to HWE (P > 0.004) for the analyzed polymorphisms, with the exception of the IL4 marker in the control group. The observed deviation seems to be due to a significant increase of heterozygotes in this population (P = 0.0003).

We also investigated the possible confounding factors of age, sex and genetic ancestry. Table 2 shows these results. When considered statistically significant in the comparison between groups (GC patients vs cancer-free individuals, and CRC patients vs cancer-free individuals; P ≤ 0.05), such characteristics were controlled in the logistic regression that assessed whether there are significant differences in the following tests: (1) carriers of INS/INS genotype vs carriers of other genotypes (INS/DEL + DEL/DEL); (2) carriers of DEL/DEL genotype vs carriers of other genotypes (INS/DEL + INS/INS); and (3) additive effect of the alleles (joint presence of the significant alleles from tests I and II).

Table 2.

Demographic data for patient and control groups

| Variable | GC | CRC | Control |

P-value |

|

| GC vs Control | CRC vs Control | ||||

| n | 120 | 64 | 475 | - | - |

| Age, yr1 | 57.02 ± 1.29 | 52.84 ± 1.90 | 55.59 ± 0.91 | 0.522 | 0.294 |

| Sex, % of male/female | 55.0/45.0 | 45.3/54.70 | 34.7/65.3 | 0.0003 | 0.098 |

| European ancestry2 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.53 ± 0.02 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 0.0023 | 0.0033 |

| African ancestry2 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.071 | 0.0163 |

| Amerindian ancestry2 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 0.114 | 0.100 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Significance was obtained by Student’s t-test;

Values are expressed as mean ± SD. Significance was obtained by Mann-Whitney test;

Statistically significant. CRC: Colorectal cancer; GC: Gastric cancer.

In the analyses with GC patients, positive associations were observed for the markers rs79071878 (IL4 gene), rs3730485 (MDM2 gene) and rs28362491 (NFKB1 gene) after correction of confounding factors for this group (sex and European ancestry) (Table 3). For rs79071878, carriers of the RP1/RP1 genotype have approximately 3-fold increased chances of developing GC than carriers of other genotypes (RP1/RP1 + RP1/RP2) [P = 0.002; odds ratio (OR) = 2.857; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.490-5.479]. For rs3730485, INS/INS genotype shows a protection effect for the development of GC in comparison with different genotypes (P = 0.021; OR = 0.409; 95%CI: 0.192-0.872). For rs28362491, carriers of the DEL/DEL genotype have more chances of developing GC than carriers of the other genotypes (P = 0.006; OR = 2.918; 95%CI: 1.352-6.298).

Table 3.

Genotypic and allelic distributions of the investigated polymorphisms for patients with gastric cancer in comparison to control group

| Genotype | GC | Control | P value1 | OR (95%CI)1 | Genotype | GC | Control | P value1 | OR (95%CI)1 |

| CASP8 | 120 | 475 | RP2/RP2 | 18 (15.1) | 154 (32.5) | 0.189 | 0.673 (0.372-1.216) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 11 (9.2) | 90 (19.0) | 0.650 | 0.892 (0.545-1.461) | Allele RP1 | 0.54 | 0.41 | ||

| INS/DEL | 70 (58.3) | 230 (48.4) | Allele RP2 | 0.46 | 0.59 | ||||

| INS/INS | 39 (32.5) | 155 (32.6) | 0.080 | 1.936 (0.924-4.058) | NFKB1 | 120 | 473 | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.38 | 0.43 | DEL/DEL | 34 (28.3) | 117 (24.7) | 0.0062 | 2.918 (1.352-6.298) | ||

| Allele INS | 0.62 | 0.57 | INS/DEL | 71 (59.2) | 246 (52.0) | ||||

| MDM2 | 120 | 475 | INS/INS | 15 (12.5) | 110 (23.3) | 0.88 | 0.959 (0.5662-1.610) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 13 (10.8) | 33 (6.9) | 0.199 | 1.365 (0.849-2.192) | Allele DEL | 0.58 | 0.51 | ||

| INS/DEL | 46 (38.3) | 168 (35.4) | Allele INS | 0.42 | 0.49 | ||||

| INS/INS | 61 (50.9) | 274 (57.7) | 0.0212 | 0.409 (0.192-0.872) | PAR1 | 113 | 473 | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.30 | 0.25 | DEL/DEL | 66 (58.4) | 273 (57.7) | 0.068 | 0.482 (0.221-1.054) | ||

| Allele INS | 0.70 | 0.75 | INS/DEL | 36 (31.9) | 169 (35.7) | ||||

| TP53 | 120 | 475 | INS/INS | 11 (9.7) | 31 (6.6) | 0.949 | 0.984 (0.601-1.610) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 91 (75.8) | 350 (73.7) | 0.999 | 138214253.0 (0.000) | Allele DEL | 0.74 | 0.76 | ||

| INS/DEL | 27 (22.5) | 116 (24.4) | Allele INS | 0.26 | 0.24 | ||||

| INS/INS | 2 (1.7) | 9 (1.9) | 0.247 | 0.708 (0.395-1.270) | CYP2E1 | 116 | 475 | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.87 | 0.86 | DEL/DEL | 94 (81.0) | 398 (83.8) | 0.999 | 276187721.0 (0.000) | ||

| Allele INS | 0.13 | 0.14 | INS/DEL | 21 (18.1) | 73 (15.4) | ||||

| TYMS | 120 | 475 | INS/INS | 1 (0.9) | 4 (0.8) | 0.574 | 1.193 (0.644-2.212) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 16 (13.3) | 65 (13.7) | 0.409 | 1.231 (0.752-2.015) | Allele DEL | 0.90 | 0.91 | ||

| INS/DEL | 53 (44.2) | 224 (47.2) | Allele INS | 0.10 | 0.09 | ||||

| INS/INS | 51 (42.5) | 186 (39.2) | 0.867 | 1.060 (0.536-2.096) | CYP19A1 | 120 | 475 | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.35 | 0.37 | DEL/DEL | 18 (15.0) | 76 (16.0) | 0.654 | 1.127 (0.669-1.897) | ||

| Allele INS | 0.65 | 0.63 | INS/DEL | 67 (55.8) | 248 (52.2) | ||||

| XRCC1 | 119 | 474 | INS/INS | 35 (29.2) | 151 (31.8) | 0.415 | 1.334 (0.667-2.671) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 10 (8.4) | 35 (7.4) | 0.346 | 1.257 (0.781-2.021) | Allele DEL | 0.43 | 0.42 | ||

| INS/DEL | 48 (40.3) | 179 (37.8) | Allele INS | 0.57 | 0.58 | ||||

| INS/INS | 61 (51.3) | 260 (54.8) | 0.396 | 0.697 (0.303-1.604) | UGT1A1 | 120 | 464 | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.29 | 0.26 | *1/*1 | 49 (40.8) | 206 (44.5) | 0.792 | 1.109 (0.515-2.386) | ||

| Allele INS | 0.71 | 0.74 | *1/*28 | 57 (47.5) | 209 (45.0) | ||||

| IL1A | 120 | 475 | *28/*28 | 12 (10.0) | 46 (9.9) | 0.445 | 1.205 (0.746-1.946) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 17 (14.2) | 86 (18.1) | 0.626 | 0.882 (0.522-1.460) | *36/*1 | 2 (1.7) | 3 (0.6) | ||

| INS/DEL | 63 (52.5) | 246 (51.8) | *36/*37 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.585 | 1.941 (0.180-20.973) | ||

| INS/INS | 40 (33.3) | 143 (30.1) | 0.143 | 1.705 (0.835-3.482) | *1/*37 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.40 | 0.44 | Allele *36 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Allele INS | 0.60 | 0.56 | Allele *1 | 0.65 | 0.67 | ||||

| IL4 | 119 | 474 | Allele *28 | 0.34 | 0.32 | ||||

| RP1/RP1 | 28 (23.6) | 69 (14.5) | 0.0022 | 2.857 (1.490-5.479) | Allele *37 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| RP1/RP2 | 73 (61.3) | 251 (53.0) |

Data for GC and Control columns are presented as n or n (%).

Analysis of combined genotypes (INS/INS vs others, or DEL/DEL vs others) with adjusted values for confounding factors (sex and European ancestry) in logistic regression;

Statistically significant. GC: Gastric cancer.

In the analyses with CRC patients, markers rs28362491 (NFKB1 gene) and rs8175347 (UGT1A1 gene) showed positive association after the correction of confounding factors (European and African ancestries) (Table 4). Similar to the result for GC, carriers of the DEL/DEL genotype for rs28362491 should present more chances of developing CRC in comparison to carriers of other genotypes (P = 0.006; OR = 3.732; 95%CI: 1.451-9.599). For rs8175347, which has multiple alleles (*1, *28, *36 and *37), our results show that 8% of the CRC patients and 0.6% of the cancer-free individuals carry at least one of the rare alleles (*36 and *37). Comparing both groups, we observed that such allele presence could lead to almost 13-fold increased chances of developing CRC (P = 0.001; OR = 12.849; 95%CI: 2.906-56.817).

Table 4.

Genotypic and allelic distributions of the investigated polymorphisms for patients with colorectal cancer in comparison to control group

| Genotype | CRC | Control | P value1 | OR (95%CI)a | Genotype | CRC | Control | P-value1 | OR (95%CI)1 |

| CASP8 | 63 | 475 | RP2/RP2 | 16 (25.4) | 154 (32.5) | 0.871 | 1.068 (0.482-2.368) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 13 (20.6) | 90 (19.0) | 0.676 | 0.888 (0.508-1.552) | Allele RP1 | 0.44 | 0.41 | ||

| INS/DEL | 28 (44.4) | 230 (48.4) | Allele RP2 | 0.56 | 0.59 | ||||

| INS/INS | 22 (35.0) | 155 (32.6) | 0.939 | 0.974 (0.503-1.887) | NFKB1 | 63 | 473 | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.43 | 0.43 | DEL/DEL | 16 (25.4) | 117 (24.7) | 0.0062 | 3.732 (1.451-9.599) | ||

| Allele INS | 0.57 | 0.57 | INS/DEL | 42 (66.7) | 246 (52.0) | ||||

| MDM2 | 64 | 475 | INS/INS | 5 (7.9) | 110 (23.3) | 0.829 | 0.935 (0.508-1.723) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 7 (10.9) | 33 (6.9) | 0.412 | 1.166 (0.143-9.487) | Allele DEL | 0.60 | 0.51 | ||

| INS/DEL | 25 (39.1) | 168 (35.4) | Allele INS | 0.40 | 0.49 | ||||

| INS/INS | 32 (50.0) | 274 (57.7) | 0.986 | 0.995 (0.546-1.811) | PAR1 | 63 | 473 | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.30 | 0.25 | DEL/DEL | 37 (58.7) | 273 (57.7) | 0.464 | 0.704 (0.275-1.801) | ||

| Allele INS | 0.70 | 0.75 | INS/DEL | 20 (31.8) | 169 (35.7) | ||||

| TP53 | 64 | 475 | INS/INS | 6 (9.5) | 31 (6.6) | 0.813 | 0.937 (0.546-1.608) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 47 (73.4) | 350 (73.7) | 0.886 | 1.166 (0.143-9.487) | Allele DEL | 0.75 | 0.76 | ||

| INS/DEL | 16 (25.0) | 116 (24.4) | Allele INS | 0.25 | 0.24 | ||||

| INS/INS | 1 (1.6) | 9 (1.9) | 0.986 | 0.995 (0.546-1.811) | CYP2E1 | 62 | 475 | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.86 | 0.86 | DEL/DEL | 56 (90.3) | 398 (83.8) | 0.999 | 189364591.0 (0.000) | ||

| Allele INS | 0.14 | 0.14 | INS/DEL | 6 (9.7) | 73 (15.4) | ||||

| TYMS | 63 | 475 | INS/INS | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.8) | 0.351 | 0.655 (0.269-1.593) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 11 (17.5) | 65 (13.7) | 0.304 | 1.342 (0.765-2.354) | Allele DEL | 0.95 | 0.91 | ||

| INS/DEL | 31 (49.2) | 224 (47.2) | Allele INS | 0.05 | 0.09 | ||||

| INS/INS | 21 (33.3) | 186 (39.2) | 0.429 | 0.751 (0.369-1.526) | CYP19A1 | 64 | 475 | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.42 | 0.37 | DEL/DEL | 7 (10.9) | 76 (16.0) | 0.297 | 0.747 (0.431-1.293) | ||

| Allele INS | 0.58 | 0.63 | INS/DEL | 33 (51.6) | 248 (52.2) | ||||

| XRCC1 | 64 | 474 | INS/INS | 24 (37.5) | 151 (31.8) | 0.313 | 1.532 (0.669-3.508) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 4 (6.2) | 35 (7.4) | 0.771 | 1.082 (0.637-1.838) | Allele DEL | 0.37 | 0.42 | ||

| INS/DEL | 27 (42.2) | 179 (37.8) | Allele INS | 0.63 | 0.58 | ||||

| INS/INS | 33 (51.6) | 260 (54.8) | 0.445 | 1.528 (0.515-4.535) | UGT1A1 | 63 | 464 | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.27 | 0.26 | *1/*1 | 20 (31.7) | 206 (44.5) | 0.098 | 0.541 (0.262-1.120) | ||

| Allele INS | 0.73 | 0.74 | *1/*28 | 32 (50.8) | 209 (45.0) | ||||

| IL1A | 64 | 475 | *28/*28 | 6 (9.5) | 46 (9.9) | 0.370 | 1.282 (0.745-2.205) | ||

| DEL/DEL | 10 (15.6) | 86 (18.1) | 0.657 | 0.880 (0.500-1.548) | *36/*1 | 3 (4.8) | 3 (0.6) | ||

| INS/DEL | 33 (51.6) | 246 (51.8) | *36/*37 | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0012 | 12.849 (2.906-56.817) | ||

| INS/INS | 21 (32.8) | 143 (30.1) | 0.610 | 1.208 (0.584-2.368) | *1/*37 | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Allele DEL | 0.41 | 0.44 | Allele *36 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| Allele INS | 0.59 | 0.56 | Allele *1 | 0.60 | 0.67 | ||||

| IL4 | 63 | 474 | Allele *28 | 0.35 | 0.32 | ||||

| RP1/RP1 | 8 (12.7) | 69 (14.5) | 0.195 | 1.493 (0.814-2.740) | Allele *37 | 0.02 | 0.00 | ||

| RP1/RP2 | 39 (61.9) | 251 (53.0) |

Data for CRC and Control columns are presented as n or n (%).

Analysis of combined genotypes (INS/INS vs others, or DEL/DEL vs others) with adjusted values for confounding factors (European and African ancestries) in logistic regression;

Statistically significant. CRC: Colorectal cancer; INDEL: Insertion/deletion.

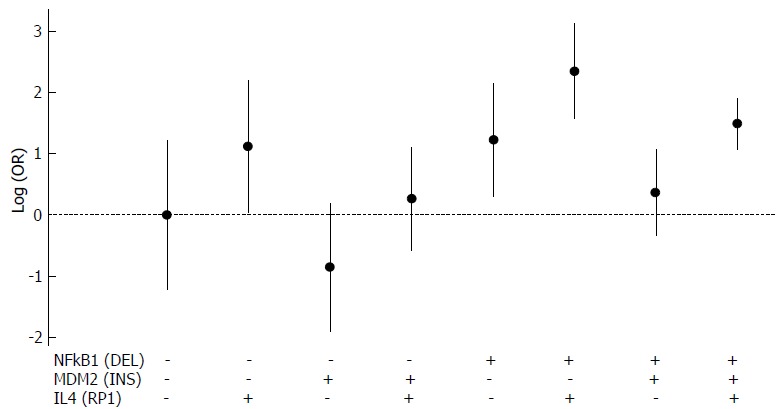

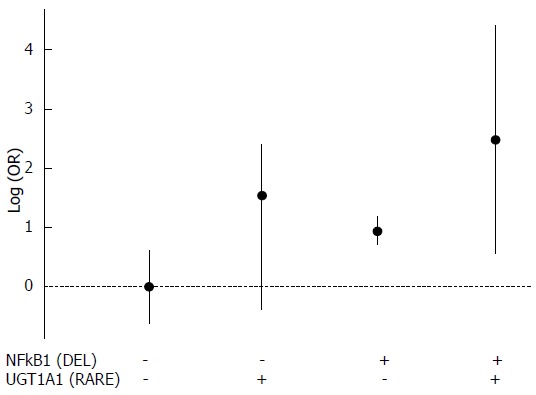

In addition, we analyzed whether the joint presence of the alleles that were statistically significant when in homozygosis (RP1 allele of rs79071878, INS allele of rs3730485, DEL allele of rs28362491 and *36 and *37 alleles in rs8175347) may affect the development of GC and CRC. After controlling for the confounding factors, we obtained statistically significant results for both GC (P = 0.004311) and CRC (P = 3.52 × 10-6) analyses. These findings are shown in Figure 1 for GC and in Figure 2 for CRC.

Figure 1.

Analysis of the joint presence of three alleles regarding gastric cancer development. DEL allele of rs28362491 is represented by NFKB1 (DEL), INS allele of rs3730485 is represented by MDM2 (INS) and RP1 allele of rs79071878 is represented by IL4(RP1). All possible combinations were considered. Allele presence is represented by (+) and allele absence is represented by (-). DEL: Deletion; GC: Gastric cancer; INS: Insertion.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the joint presence of two alleles regarding colorectal cancer development. DEL allele of rs28362491 is represented by NFKB1 (DEL) and *36 and *37 alleles in rs8175347 are represented by UGT1A1 (RARE). All possible combinations were considered. Allele presence is represented by (+) and allele absence is represented by (-). CRC: Colorectal cancer; DEL: Deletion.

We highlight some positive associations of these alleles due to the absence of neutral effect (logOR = 0 or OR = 1) in the 95%CI for GC [IL4(RP1): OR = 3.068, 95%CI: 1.036-9.088; NFKB1(DEL): OR = 3.414, 95%CI: 1.347-8.654; IL4(RP1) + NFKB1(DEL): OR = 10.475, 95%CI: 4.845-22.624); IL4(RP1) + NFKB1(DEL) + MDM2(INS): OR = 4.437, 95%CI: 2.948-6.686] and CRC [NFKB1(DEL): OR = 2.552, 95%CI: 2.014-3.238; NFKB1(DEL) + UGT1A1(RARE): OR = 11.929, 95%CI: 1.732-82.187)].

DISCUSSION

In the HWE analysis for the IL4 marker in the control group, the large amount of heterozygotes could be explained either by selective advantage of the heterozygote or by an intense or continuous process of admixture between populations with different genetic backgrounds. Allele frequencies for this marker vary greatly between the three main populations that contributed to the formation of the Brazilian population; the frequency of the RP2 allele has been described as 0.74 among Europeans, 0.23 among Amerindians and 0.42 among Africans[56]. Due to the recent formation of the Brazilian population, we believe that the admixture process is more fitted to explain the observed disequilibrium.

In the analysis for GC, we observed a positive association between the IL4 marker (rs79071878) and the development of this type of cancer. This polymorphism is a 70-bp variable number tandem repeat located in an intron of IL4, which is an interleukin involved in inflammatory pathways. We did not find other studies relating to this polymorphism and GC, but the increased risk of the development of bladder cancer among the carriers of RP1 allele has been previously described[14,57]. Recently, we reported that the frequency of the RP1 allele of rs79071878 is higher in the North of Brazil (0.414) than in the other regions of the country (mean = 0.233), probably due to the elevated frequency of this marker in Amerindian populations[56]. Data have revealed that the highest incidence of GC in Brazil occurs in the North region. The apparent overlap between the greater incidence of GC and the elevated frequency of RP1 (rs78071878) in the North region of Brazil seems to corroborate the results that indicate that the carriers of homozygous RP1 allele have greater chances of developing GC than the carriers of other genotypes, possibly due to the close relation of this type of cancer with increased inflammation. More studies involving this polymorphism in different admixed populations in this country are recommended.

As for the polymorphism in the MDM2 gene (rs3730485), we observed that the carriers of INS/INS genotype have less chances of developing GC than carriers of the other genotypes of this marker. To the best of our knowledge, there are no other studies reporting the positive association of this polymorphism and GC development, but the DEL allele has been shown to be associated with increased risk of developing various types of cancer, e.g, hepatocellular carcinoma[29], breast cancer[58], prostate cancer[59] and colon cancer[60] in different populations. MDM2 is an oncogene responsible for the regulation of TP53 expression[61]. The INS allele of rs3730485 may reduce the activity of MDM2, possibly increasing the activity of the tumor suppressor TP53 and then reducing the chances of developing cancer.

In the current study, we observed an association of the DEL/DEL genotype of the polymorphism in NFKB1 (rs28362491) with increased chances of developing both GC and CRC. This is an INDEL polymorphism that is located in the promoter region of the gene, which is highly involved in inflammatory pathways. The DEL/DEL genotype has been previously associated with an increased risk of developing GC in a Japanese population[37] and bladder cancer in a Chinese population[62]. In addition, the DEL allele of this polymorphism has been related to the development of ulcerative colitis and H. pylori infection[63,64], which can increase the risk of CRC and GC. Regarding the INS/INS genotype, it has been associated with decreased development risk of ovarian cancer[65] and with increased risk of developing melanoma[66], while the DEL/DEL genotype has also been associated with reduced risk of developing other types of cancer[67]. Previous studies have suggested that the effects of rs28362491 on the risk of carcinogenesis may be ethnic- and cancer type-specific, as described by two meta-analyses involving Asian and Caucasian populations[68,69].

The UGT1A1 gene is involved in hepatic detoxification and metabolization of different substances. The studied marker in this gene (rs8175347) has four possible alleles [*36 (5 repeats), *1 (6 repeats), *28 (7 repeats) and *37 (8 repeats)]. Allele *1 is considered the wild-type and the most common allele, *28 is the second most common allele and *36 and *37 are considered rare alleles. In this study, we observed that the presence of at least one of the rare alleles of this polymorphism appears to increase the chances of developing CRC by 13-times. In the literature, some studies show that alleles *36 and *37 are absent or extremely rare in different populations[70,71], but there are no studies relating the association of these alleles with the development of CRC. Although little is known about *36 and *37 alleles, it is possible that the presence of such alleles could lead to a decreased activity of the UGT1A1 gene, inducing the carcinogenesis process. We understand that the sample size of CRC patients may have influenced the observed result in this study, but we believe that our findings indicate the need to expand the investigation to a great number of patients from other Brazilian admixed populations, considering the important increase rate we observed.

In addition, we investigated the joint presence of the alleles that were statistically significant in homozygosis in the analyses discussed above. This is important because the interaction of alleles in different loci could lead to an increased effect in the carcinogenesis. Recently, this kind of additive effect has been reported for multiple types of cancer in different populations[72,74], but there is a lack of this type of study involving GC and CRC in the Brazilian population. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using this approach for these types of cancer in a Brazilian population.

The analyses of combined effect showed statistical significance for both types of cancer, presenting some interesting results. Among these, it is notable that: (1) individuals carrying both RP1 (IL4 marker) and DEL (NFKB1 marker) alleles have more than 10-fold increased chances of developing GC than carriers of the other alleles; and (2) individuals carrying the DEL allele (NFKB1 marker) and at least one of the rare alleles *36 and *37 (UGT1A1 marker) have almost 12-fold increased chances of developing CRC than carriers of other alleles of these markers. These results reinforce the importance of knowing which markers may play a role in cancer development.

In conclusion, we investigated 12 polymorphisms in genes with functions in inflammatory pathways, immune response or cellular and genomic stability (i.e. CASP8, CYP2E1, CYP19A1, IL1A, IL4, MDM2, NFKB1, PAR1, TP53, TYMS, UGT1A1 and XRCC1) regarding the development of GC and CRC. Our findings indicate that some of these markers may be related to the development of GC and CRC. Moreover, the interaction between such polymorphisms may increase the risk of developing these types of cancer. These results contribute to a greater knowledge of possible risk factors in the development of GC and CRC.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Our research group, located in the North region of Brazil, has been working with population genetics for many years. More recently, we have designed a set of 12 markers that are able to be genotyped in a single multiplex PCR and capillary electrophoresis, which is faster than Sanger sequencing and cheaper than real-time PCR. All markers in this set are in genes related to different pathways (e.g. inflammatory and immune response, and cellular and genomic stability). We have previously investigated not only the association of this set with the development of different diseases (i.e. acute lymphoblastic leukemia and leprosy), but also the distribution of these markers in individuals from the five regions of Brazil (North, Northeast, Midwest, Southeast and South) and in individuals representative of the main parental populations of this country (Europeans, Africans and Native Americans). However, we believe it also is important to investigate the association of this set with the development of other types of cancer, such as gastric cancer (GC) and colorectal cancer (CRC).

Research motivation

GC and CRC are two of the most incident and aggressive types of malignant neoplasms in Brazil. A notable aspect of the Brazilian population is that it is highly admixed and, then, it is important not to extrapolate results from one region to another. For instance, these types of cancer are particularly frequent in the North region of Brazil. In general, most cases of GC and CRC are diagnosed in advanced stages and the death rate related to these types of cancer is high. To help early diagnosis, many research groups worldwide have been working to identify biomarkers able to detect increased risk of developing such types of cancer. Considering the high incidence of GC and CRC in the North region, we believe that it is important to study such neoplasms in this region.

Research objectives

In this study, we analyzed the association of 12 polymorphisms in genes involved in inflammatory pathways, immune response or cellular and genomic stability (namely, CASP8, CYP2E1, CYP19A1, IL1A, IL4, MDM2, NFKB1, PAR1, TP53, TYMS, UGT1A1 and XRCC1) regarding GC and CRC development in a population from the North region of Brazil. Understanding the distribution of these markers in the studied population helps to improve the knowledge of the different factors that lead to cancer development.

Research methods

We collected blood samples from the participants (125 GC patients, 66 CRC patients and 475 cancer-free individuals), from which we extracted the DNA using a phenol-chloroform-based method. The studied 12-polymorphism set can be genotyped through amplification in a single multiplex PCR, followed by capillary electrophoresis. The different statistical analyses were performed in Structure v.2.3.4 and SPSS v.20 programs, and the R language. We analyzed the allelic and genotypic distribution of these markers, as well as the combined effect of the statistically significant alleles. The latter approach is not a common approach for studying GC and CRC. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using this kind of approach for these types of cancer in the Brazilian population. It gave us interesting results.

Research results

After performing the statistical analyses with correction of confounding factors, we observed positive associations between the markers rs79071878 (IL4 gene), rs3730485 (MDM2 gene) and rs28362491 (NFKB1 gene) and GC development, as well as between the markers rs28362491 (NFKB1 gene) and rs8175347 (UGT1A1 gene) and CRC development. When we analyzed the combined effect of the alleles of the statistically significant genotypes of each marker (RP1 allele of rs79071878, INS allele of rs3730485, DEL allele of rs28362491 and *36 and *37 alleles in rs8175347), we obtained statistically significant results for both types of cancer. From these results, we highlight that: (1) individuals carrying both RP1 (IL4 marker) and DEL (NFKB1 marker) alleles have more than 10-fold increased chances of developing GC than carriers of the other alleles; and (2) individuals carrying the DEL allele (NFKB1 marker) and at least one of the rare alleles *36 and *37 (UGT1A1 marker) have almost 12-fold increased chances of developing CRC than carriers of other alleles of these markers. Our results reinforce the importance of knowing the role that different markers play in the development of cancer, which may contribute to the early detection of GC and CRC.

Research conclusions

In this study, we observed that the individual or joint presence of some alleles of the 12 polymorphisms of the set may affect the development of GC (RP1 allele of rs79071878, INS allele of rs3730485 and DEL allele of rs28362491) and/or CRC (DEL allele of rs28362491 and *36 and *37 alleles in rs8175347) in a population from the North region of Brazil. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time it has been reported, and it supports the notion that more attention should be given to these polymorphisms in relation to the development of GC and CRC. Considering the results we obtained, we recommend that the individual and the joint presence of these markers should be further investigated in the other regions of Brazil, due to the high levels of admixture in this country, and in other types of cancer.

Research perspectives

Although there have been many advances in the complex field of oncogenetics, there is still a lot remaining to be discovered. The present study investigated 12 polymorphisms, some of them not frequently studied, and showed statistically significant association between four of these markers and the development of GC and CRC in a population from the North region of Brazil. It shows the importance of studying different polymorphisms in important genes, some of which may be involved not only in the development of GC and CRC but also of other types of malignant neoplasms. In addition, our study reinforces the notion of investigating different types of cancer in genetically admixed populations, such as the Brazilian population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank CNPq, CAPES, FAPESPA and PROPESP/UFPA-FADESP for the grants received. We also thank Pablo Diego do Carmo Pinto for excellent statistical and technical assistance.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação da Universidade Federal do Pará/Fundação Amparo e Desenvolvimento da Pesquisa (PROPESP-UFPA/FADESP).

Institutional review board statement: The study was approved by the Committee for Research Ethics of the Hospital João de Barros Barreto under Protocol No. CAAE 25865714.6.0000.0017.

Informed consent statement: All participants provided their informed consent prior to study inclusion.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interests in this study.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: September 15, 2017

First decision: October 10, 2017

Article in press: November 8, 2017

P- Reviewer: Espinel J, Kimura A, Lee JI S- Editor: Chen K L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

Contributor Information

Giovanna C Cavalcante, Laboratório de Genética Humana e Médica, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66075-970, Brazil; Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Brazil.

Marcos AT Amador, Laboratório de Genética Humana e Médica, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66075-970, Brazil.

André M Ribeiro dos Santos, Laboratório de Genética Humana e Médica, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66075-970, Brazil.

Darlen C Carvalho, Laboratório de Genética Humana e Médica, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66075-970, Brazil; Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Brazil.

Roberta B Andrade, Laboratório de Genética Humana e Médica, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66075-970, Brazil; Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Brazil.

Esdras EB Pereira, Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Brazil.

Marianne R Fernandes, Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Brazil.

Danielle F Costa, Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Brazil.

Ney PC Santos, Laboratório de Genética Humana e Médica, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66075-970, Brazil; Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Brazil.

Paulo P Assumpção, Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Brazil.

Ândrea Ribeiro dos Santos, Laboratório de Genética Humana e Médica, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66075-970, Brazil; Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Brazil.

Sidney Santos, Laboratório de Genética Humana e Médica, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66075-970, Brazil sidneysantos@ufpa.br; Núcleo de Pesquisas em Oncologia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém 66073-005, Brazil.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rio de Janeiro: INCA, 126p; 2015. INCA - Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva Estimativa 2016: Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watari J, Chen N, Amenta PS, Fukui H, Oshima T, Tomita T, Miwa H, Lim KJ, Das KM. Helicobacter pylori associated chronic gastritis, clinical syndromes, precancerous lesions, and pathogenesis of gastric cancer development. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5461–5473. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon SB, Park JM, Lim CH, Cho YK, Choi MG. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous gastric cancer after endoscopic resection of gastric tumors: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2014;19:243–248. doi: 10.1111/hel.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yashiro M. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16389–16397. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herszényi L, Barabás L, Miheller P, Tulassay Z. Colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: the true impact of the risk. Dig Dis. 2015;33:52–57. doi: 10.1159/000368447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang F, Meng W, Wang B, Qiao L. Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;345:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khatoon J, Rai RP, Prasad KN. Role of Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer: Updates. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8:147–158. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vannucci L, Stepankova R, Grobarova V, Kozakova H, Rossmann P, Klimesova K, Benson V, Sima P, Fiserova A, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H. Colorectal carcinoma: Importance of colonic environment for anti-cancer response and systemic immunity. J Immunotoxicol. 2009;6:217–226. doi: 10.3109/15476910903334343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mantovani A. Molecular pathways linking inflammation and cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10:369–373. doi: 10.2174/156652410791316968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Prete A, Allavena P, Santoro G, Fumarulo R, Corsi MM, Mantovani A. Molecular pathways in cancer-related inflammation. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2011;21:264–275. doi: 10.11613/bm.2011.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin CW, Hsieh YS, Hsin CH, Su CW, Lin CH, Wei LH, Yang SF, Chien MH. Effects of NFKB1 and NFKBIA gene polymorphisms on susceptibility to environmental factors and the clinicopathologic development of oral cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janakiram NB, Rao CV. The role of inflammation in colon cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;816:25–52. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-0837-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elingarami S, Liu H, Kalinjuma AV, Hu W, Li S, He N. Polymorphisms in NEIL-2, APE-1, CYP2E1 and MDM2 Genes are Independent Predictors of Gastric Cancer Risk in a Northern Jiangsu Population (China) J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2015;15:4815–4828. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2015.10028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramalhinho AC, Fonseca-Moutinho JA, Breitenfeld Granadeiro LA. Positive association of polymorphisms in estrogen biosynthesis gene, CYP19A1, and metabolism, GST, in breast cancer susceptibility. DNA Cell Biol. 2012;31:1100–1106. doi: 10.1089/dna.2011.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan X, Liu H, Ju J, Li Y, Li P, Wang LE, Brewster AM, Buchholz TA, Arun BK, Wei Q, et al. Genetic variant rs16430 6bp > 0bp at the microRNA-binding site in TYMS and risk of sporadic breast cancer risk in non-Hispanic white women aged ≤ 55 years. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54:281–290. doi: 10.1002/mc.22097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pineda B, García-Pérez MÁ, Cano A, Lluch A, Eroles P. Associations between aromatase CYP19 rs10046 polymorphism and breast cancer risk: from a case-control to a meta-analysis of 20,098 subjects. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashemi M, Omrani M, Eskandari-Nasab E, Hasani SS, Mashhadi MA, Taheri M. A 40-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism of Murine Double Minute2 (MDM2) increased the risk of breast cancer in Zahedan, Southeast Iran. Iran Biomed J. 2014;18:245–249. doi: 10.6091/ibj.13332.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhlmann JD, Bankfalvi A, Schmid KW, Callies R, Kimmig R, Wimberger P, Siffert W, Bachmann HS. Prognostic relevance of caspase 8 -652 6N InsDel and Asp302His polymorphisms for breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:618. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2662-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahirwar D, Kesarwani P, Manchanda PK, Mandhani A, Mittal RD. Anti- and proinflammatory cytokine gene polymorphism and genetic predisposition: association with smoking, tumor stage and grade, and bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy in bladder cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008;184:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson SH, Orlow I, Bayuga S, Sima C, Bandera EV, Pulick K, Faulkner S, Tommasi D, Egan D, Roy P, et al. Variants in hormone biosynthesis genes and risk of endometrial cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:955–963. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9160-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carvalho DC, Wanderley AV, Amador MA, Fernandes MR, Cavalcante GC, Pantoja KB, Mello FA, de Assumpção PP, Khayat AS, Ribeiro-Dos-Santos Â, Santos S, Dos Santos NP. Amerindian genetic ancestry and INDEL polymorphisms associated with susceptibility of childhood B-cell Leukemia in an admixed population from the Brazilian Amazon. Leuk Res. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karakosta M, Kalotychou V, Kostakis A, Pantelias G, Rombos I, Kouraklis G, Manola KN. UGT1A1*28 polymorphism in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the first investigation of the polymorphism in disease susceptibility and its specific cytogenetic abnormalities. Acta Haematol. 2014;132:59–67. doi: 10.1159/000355714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang CM, Chen HC, Hou YY, Lee MC, Liou HH, Huang SJ, Yen LM, Eng DM, Hsieh YD, Ger LP. A high IL-4 production diplotype is associated with an increased risk but better prognosis of oral and pharyngeal carcinomas. Arch Oral Biol. 2014;59:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang YI, Liu Y, Zhao W, Yu T, Yu H. Caspase-8 polymorphisms and risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Exp Ther Med. 2015;10:2267–2276. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ji GH, Li M, Cui Y, Wang JF. The relationship of CASP 8 polymorphism and cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2014;60:20–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang ZH, Dai Q, Zhong L, Zhang X, Guo QX, Li SN. Association of IL-1 polymorphisms and IL-1 serum levels with susceptibility to nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2011;50:208–214. doi: 10.1002/mc.20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santoro AB, Vargens DD, Barros Filho Mde C, Bulzico DA, Kowalski LP, Meirelles RM, Paula DP, Neves RR, Pessoa CN, Struchine CJ, et al. Effect of UGT1A1, UGT1A3, DIO1 and DIO2 polymorphisms on L-thyroxine doses required for TSH suppression in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78:1067–1075. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong D, Gao X, Zhu Z, Yu Q, Bian S, Gao Y. A 40-bp insertion/deletion polymorphism in the constitutive promoter of MDM2 confers risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in a Chinese population. Gene. 2012;497:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lurje G, Husain H, Power DG, Yang D, Groshen S, Pohl A, Zhang W, Ning Y, Manegold PC, El-Khoueiry A, et al. Genetic variations in angiogenesis pathway genes associated with clinical outcome in localized gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:78–86. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malik MA, Sharma K, Goel S, Zargar SA, Mittal B. Association of TP53 intron 3, 16 bp duplication polymorphism with esophageal and gastric cancer susceptibility in Kashmir Valley. Oncol Res. 2011;19:165–169. doi: 10.3727/096504011x12935427587920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan XF, Xie Y, Loh M, Yang SJ, Wen YY, Tian Z, Huang H, Lan H, Chen F, Soong R, et al. Polymorphisms of XRCC1 and ADPRT genes and risk of noncardia gastric cancer in a Chinese population: a case-control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:5637–5642. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.11.5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujimoto D, Hirono Y, Goi T, Katayama K, Matsukawa S, Yamaguchi A. The activation of proteinase-activated receptor-1 (PAR1) promotes gastric cancer cell alteration of cellular morphology related to cell motility and invasion. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:565–573. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiao W, Wang T, Zhang L, Tang Q, Wang D, Sun H. Association study of single nucleotide polymorphisms in XRCC1 gene with the risk of gastric cancer in Chinese population. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9:753–758. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen R, Liu H, Wen J, Liu Z, Wang LE, Wang Q, Tan D, Ajani JA, Wei Q. Genetic polymorphisms in the microRNA binding-sites of the thymidylate synthase gene predict risk and survival in gastric cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54:880–888. doi: 10.1002/mc.22160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeng XF, Li J, Li SB. A functional polymorphism in IL-1A gene is associated with a reduced risk of gastric cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:265–268. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arisawa T, Tahara T, Shiroeda H, Yamada K, Nomura T, Yamada H, Hayashi R, Matsunaga K, Otsuka T, Nakamura M, et al. Functional promoter polymorphisms of NFKB1 influence susceptibility to the diffuse type of gastric cancer. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:3013–3019. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghoshal U, Tripathi S, Kumar S, Mittal B, Chourasia D, Kumari N, Krishnani N, Ghoshal UC. Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP2E1 genes modulate susceptibility to gastric cancer in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:226–234. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hua T, Qinsheng W, Xuxia W, Shuguang Z, Ming Q, Zhenxiong L, Jingjie W. Nuclear factor-kappa B1 is associated with gastric cancer in a Chinese population. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e279. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin G, Morita M, Ohnaka K, Toyomura K, Hamajima N, Mizoue T, Ueki T, Tanaka M, Kakeji Y, Maehara Y, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of XRCC1, alcohol consumption, and the risk of colorectal cancer in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2012;22:64–71. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20110059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian Z, Li YL, Liu JG. XRCC1 Arg399Gln polymorphism contributes to increased risk of colorectal cancer in Chinese population. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40:4147–4151. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le Marchand L, Donlon T, Seifried A, Wilkens LR. Red meat intake, CYP2E1 genetic polymorphisms, and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1019–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morita M, Tabata S, Tajima O, Yin G, Abe H, Kono S. Genetic polymorphisms of CYP2E1 and risk of colorectal adenomas in the Self Defense Forces Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1800–1807. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morita M, Le Marchand L, Kono S, Yin G, Toyomura K, Nagano J, Mizoue T, Mibu R, Tanaka M, Kakeji Y, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of CYP2E1 and risk of colorectal cancer: the Fukuoka Colorectal Cancer Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:235–241. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersen V, Christensen J, Overvad K, Tjønneland A, Vogel U. Polymorphisms in NFkB, PXR, LXR and risk of colorectal cancer in a prospective study of Danes. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:484. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sameer AS, Nissar S, Qadri Q, Alam S, Baba SM, Siddiqi MA. Role of CYP2E1 genotypes in susceptibility to colorectal cancer in the Kashmiri population. Hum Genomics. 2011;5:530–537. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-5-6-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silva TD, Felipe AV, Pimenta CA, Barão K, Forones NM. CYP2E1 RsaI and 96-bp insertion genetic polymorphisms associated with risk for colorectal cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2012;11:3138–3145. doi: 10.4238/2012.September.3.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang O, Zhou R, Wu D, Liu Y, Wu W, Cheng N. CYP2E1 polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk: a HuGE systematic review and meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:1215–1224. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0664-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohd Suzairi MS, Tan SC, Ahmad Aizat AA, Mohd Aminudin M, Siti Nurfatimah MS, Andee ZD, Ankathil R. The functional -94 insertion/deletion ATTG polymorphism in the promoter region of NFKB1 gene increases the risk of sporadic colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:634–638. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kopp TI, Andersen V, Tjonneland A, Vogel U. Polymorphisms in NFKB1 and TLR4 and interaction with dietary and life style factors in relation to colorectal cancer in a Danish prospective case-cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd ed. New York: Cold Springer Harbor; 1989. p. 1626. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santos NP, Ribeiro-Rodrigues EM, Ribeiro-Dos-Santos AK, Pereira R, Gusmão L, Amorim A, Guerreiro JF, Zago MA, Matte C, Hutz MH, et al. Assessing individual interethnic admixture and population substructure using a 48-insertion-deletion (INSEL) ancestry-informative marker (AIM) panel. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:184–190. doi: 10.1002/humu.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramos BR, D’Elia MP, Amador MA, Santos NP, Santos SE, da Cruz Castelli E, Witkin SS, Miot HA, Miot LD, da Silva MG. Neither self-reported ethnicity nor declared family origin are reliable indicators of genomic ancestry. Genetica. 2016;144:259–265. doi: 10.1007/s10709-016-9894-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2008. URL: http://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amador MA, Cavalcante GC, Santos NP, Gusmão L, Guerreiro JF, Ribeiro-dos-Santos Â, Santos S. Distribution of allelic and genotypic frequencies of IL1A, IL4, NFKB1 and PAR1 variants in Native American, African, European and Brazilian populations. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:101. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-1906-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jia Y, Xie X, Shi X, Li S. Associations of common IL-4 gene polymorphisms with cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:1927–1945. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gallegos-Arreola MP, Márquez-Rosales MG, Sánchez-Corona J, Figuera LE, Zúñiga-González G, Puebla-Pérez AM, Delgado-Saucedo JI, Montoya-Fuentes H. Association of the Del1518 Promoter (rs3730485) Polymorphism in the MDM2 Gene with Breast Cancer in a Mexican Population. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2017;47:291–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hashemi M, Amininia S, Ebrahimi M, Simforoosh N, Basiri A, Ziaee SAM, Narouie B, Sotoudeh M, Mollakouchekian MJ, Rezghi Maleki E, et al. Association between polymorphisms in TP53 and MDM2 genes and susceptibility to prostate cancer. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:2483–2489. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gansmo LB, Vatten L, Romundstad P, Hveem K, Ryan BM, Harris CC, Knappskog S, Lønning PE. Associations between the MDM2 promoter P1 polymorphism del1518 (rs3730485) and incidence of cancer of the breast, lung, colon and prostate. Oncotarget. 2016;7:28637–28646. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma Y, Bian J, Cao H. MDM2 SNP309 rs2279744 polymorphism and gastric cancer risk: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li P, Gu J, Yang X, Cai H, Tao J, Yang X, Lu Q, Wang Z, Yin C, Gu M. Functional promoter -94 ins/del ATTG polymorphism in NFKB1 gene is associated with bladder cancer risk in a Chinese population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang X, Li P, Tao J, Qin C, Cao Q, Gu J, Deng X, Wang J, Liu X, Wang Z, et al. Association between NFKB1 -94ins/del ATTG Promoter Polymorphism and Cancer Susceptibility: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Int J Genomics. 2014;2014:612972. doi: 10.1155/2014/612972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karban AS, Okazaki T, Panhuysen CI, Gallegos T, Potter JJ, Bailey-Wilson JE, Silverberg MS, Duerr RH, Cho JH, Gregersen PK, et al. Functional annotation of a novel NFKB1 promoter polymorphism that increases risk for ulcerative colitis. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:35–45. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen LP, Cai PS, Liang HB. Association of the genetic polymorphisms of NFKB1 with susceptibility to ovarian cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:8273–8282. doi: 10.4238/2015.July.27.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Escobar GF, Arraes JA, Bakos L, Ashton-Prolla P, Giugliani R, Callegari-Jacques SM, Santos S, Bakos RM. Polymorphisms in CYP19A1 and NFKB1 genes are associated with cutaneous melanoma risk in southern Brazilian patients. Melanoma Res. 2016;26:348–353. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fu W, Zhuo ZJ, Chen YC, Zhu J, Zhao Z, Jia W, Hu JH, Fu K, Zhu SB, He J, et al. NFKB1 -94insertion/deletion ATTG polymorphism and cancer risk: Evidence from 50 case-control studies. Oncotarget. 2017;8:9806–9822. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Martino M, Haitel A, Schatzl G, Klingler HC, Klatte T. The CASP8 -652 6N insertion/deletion promoter polymorphism is associated with renal cell carcinoma risk and metastasis. J Urol. 2013;190:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu L, Huang S, Chen W, Song Z, Cai S. NFKB1 -94 insertion/deletion polymorphism and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:5181–5187. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1672-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Horsfall LJ, Zeitlyn D, Tarekegn A, Bekele E, Thomas MG, Bradman N, Swallow DM. Prevalence of clinically relevant UGT1A alleles and haplotypes in African populations. Ann Hum Genet. 2011;75:236–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2010.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alkharfy KM, Alghamdi AM, Bagulb KM, Al-Jenoobi FI, Al-Mohizea AM, Al-Muhsen S, Halwani R, Parvez MK, Al-Dosari MS. Distribution of selected gene polymorphisms of UGT1A1 in a Saudi population. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9:731–738. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.37012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jamhiri I, Saadat I, Omidvari S. Genetic polymorphisms of superoxide dismutase-1 A251G and catalase C-262T with the risk of colorectal cancer. Mol Biol Res Commun. 2017;6:85–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sangalli A, Orlandi E, Poli A, Maurichi A, Santinami M, Nicolis M, Ferronato S, Malerba G, Rodolfo M, Gomez Lira M. Sex-specific effect of RNASEL rs486907 and miR-146a rs2910164 polymorphisms’ interaction as a susceptibility factor for melanoma skin cancer. Melanoma Res. 2017;27:309–314. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao MM, Zhang Y, Shen L, Ren YW, Li XL, Yin ZH, Zhou BS. Genetic variations in TERT-CLPTM1L genes and risk of lung cancer in a Chinese population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:2809–2813. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.6.2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]