Abstract

The present study aimed to identify potentially critical differentially methylated genes associated with the progression of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). Methylation profiling data of GSE62336 deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database were used to identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and differentially methylated CpG islands (DMIs). Concurrently, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using a meta-analysis of three gene expression datasets (GSE53819, GSE13597 and GSE12452). Subsequently, methylated DEGs were identified by comparing DMRs and DEGs. Furthermore, functional associations of these methylated DEGs were analyzed via constructing a functional network using GeneMANIA prediction server. In total, 1,676 hypermethylated genes, 28 hypomethylated genes, 17 DMIs and 2,983 DEGs (1,655 upregulated and 1,328 downregulated) were identified. Among these DEGs, 135 downregulated genes were hypermethylated; of these, dual specificity phosphatase 6 (DUSP6) and tenascin XB (TNXB) contained DMIs. In the functional network, 154 genes and 1,651 association pairs were included. DUSP6 was predicted to exhibit genetic interactions with other hypermethylated DEGs such as malic enzyme 3 and ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 5; TNXB was predicted to be co-expressed with a set of hypermethylated DEGs, including EPH receptor B6, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member L1 and glutathione peroxidase 3. The hypermethylated DEGs may be involved in the progression of NPC, and they may become novel therapeutic targets for NPC.

Keywords: nasopharyngeal carcinoma, methylation, differentially expressed gene, functional network

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), a malignant tumor arising from the epithelium of the nasopharynx, is the most prevalent in southern China (1). In Hong Kong, the incidence of NPC is as high as 0.02–0.03% in males and 0.01–0.02% in females (2). Although the classic treatment of high-dose radiotherapy plus adjunctive chemotherapy is able to achieve a 5-year survival rate of 80%, recurrence and metastasis may occur, which are the primary causes of mortality (3). Therefore, it is necessary to identify molecular biomarkers for NPC prognosis and targeted therapy.

Aberrant DNA methylation usually leads to the occurrence of tumors. CpG island promoter hypermethylation and global DNA hypomethylation are the characteristics of the cancer epigenome (4,5). In NPC, aberrant methylation has been considered as the most frequent event for gene silencing: For example, a previous study identified that abnormal methylation on chromosome 6p occurs in 76.9% of patients with early-stage NPC, based on the comparative methylome analysis (6). Furthermore, tumor-suppressor genes such as protocadherin 8 (PCDH8), FEZ family zinc finger 2 (FEZF2) and argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS1) have been previously demonstrated to be frequently methylated in NPC, which promotes NPC cell migration, and are associated with poorer clinical outcomes (7–9).

With the exception of DNA methylation, the differential expression of genes is also frequently detected in NPC: A previous study demonstrated that the overexpression of branched-chain-amino-acid aminotransferase cytosolic (BCAT1) protein in NPC at different pathological stages and BCAT1 deficiency reduced tumor cell proliferation and decreased cell migration and invasion abilities (10). Recently, upregulation of Kelch domain containing 4 (KLHDC4) was demonstrated to result in poor overall and metastasis-free survival rates, and the deletion of KLHDC4 significantly induced the spontaneous apoptosis of NPC cells (11). However, the molecular mechanisms of NPC remain incompletely understood. There have been no studies that have comprehensively analyzed differentially expressed methylated genes using array data from multiple platforms.

In the present study, methylation profiling data in the dataset GSE62336 (6), sourced from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, were used to identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and differentially methylated CpG islands (DMIs). Concurrently, compared with differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that were identified using a meta-analysis of three gene expression datasets (GSE53819, GSE13597 and GSE12452) (12–14), differentially methylated genes were identified. Additionally, a functional network consisting of the differentially methylated genes was constructed to reveal the potential functional associations of those genes. These results may provide novel information for the study of molecular mechanisms underlying NPC and provide potential therapeutic targets for NPC.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition

Methylation profiling data from the dataset GSE62336 (6) were downloaded from GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (15). A total of 25 primary NPC tumors and non-tumor counterparts were included in this dataset, and the data were produced on the platform of Illumina HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (GPL13534, HumanMethylation450_15017482) (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Three gene expression profiling datasets (GSE53819, GSE13597 and GSE12452) were obtained from GEO. In the GSE53819 dataset (13), 18 primary NPC tumors and 18 non-cancerous nasopharyngeal tissues were included; the median ages were 46 years (range, 19–77 years) for patients with NPC, and 45 years (range, 18–78 years) for the non-cancerous cohort; almost one third of patients were females; all samples were collected prior to any anticancer treatment. Data in the GSE53819 dataset were produced on the platform of Agilent-014850 Whole Human Genome Microarray 4×44 K G4112F (Probe Name version; GPL6480; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara CA, USA). The GSE13597 dataset (14) contained data of 25 histologically confirmed undifferentiated NPC tissues and 3 non-malignant nasopharyngeal controls, which were produced on the platform of [HG-U133A] Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array (GPL96) (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Additionally, the GSE12452 dataset (12) contained 31 NPC tumor samples and 10 normal healthy nasopharyngeal tissues, data of which were produced on the platform of [HG-U133_Plus_2] Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (GPL570) (Affymetrix, Inc.).

Data preprocessing

The downloaded raw data were preprocessed. For the methylation data in GSE62336, documents of normalized average β-value were downloaded. The β-mixture quantile normalization method (BMIQ) (16) was utilized to preprocess β-values.

Due to different platforms being used for the three gene expression profiling datasets, two different methods were utilized for data preprocessing. For the gene expression data in the GSE13597 and GSE12452 datasets, raw gene expression data were preprocessed using the method of robust microarray analysis in Affy package (version 1.46.1; https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/3.1/bioc/html/affy.html) in R (17). The preprocessing steps included background correction, quantile normalization and calculation of expression. By contrast, Limma (version 3.24.15; https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/3.1/bioc/html/limma.html) package (18) in R was applied to preprocess raw data in the GSE53819 dataset. The preprocessing steps included background correction, normalization between arrays and concentration of microarray data. Following this, an annotation file of the platform corresponding to each dataset was used for the transformation of probe identities into gene symbols. If one probe corresponded to multiple genes, the expression value of this probe would be removed. However, if multiple probes corresponded to a certain gene, the mean expression value was defined as the final expression value of the gene.

Prediction of DMRs and DMIs

DMRs between NPC and normal samples were predicted using COHCAP package (version 1.6.0; http://www.bioconductor.org/pacages/3.1/bioc/html/COHCAP.html) (19) in R. Briefly, based on the β-value file of CpG site probes, Δβ, P-value and adjusted P-value of NPC and normal samples were calculated by COHCAP. Only regions with |Δβ|>0.1 and adjusted P<0.05 were identified as DMRs.

Furthermore, the COHCAP package was also utilized to predict DMIs. CpG island statistics were calculated by averaging β-values among samples per site and comparing the average β-values across groups. If the number of DMRs in the CpG island was >4, this CpG island was identified as a DMI.

Identification of DEGs using meta-analysis

MetaDE package (version 1.1.6; http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/2.11/bioc/html/metahdep.html) (20) in R was applied to integrate DEGs in the three gene expression profiling datasets. Briefly, a heterogeneity test for each gene under different platforms was firstly performed to evaluate whether each gene was homogeneous and unbiased. If the parameter tau2=0 and Qpval>0.05 (tau2 is used to estimate amount of heterogeneity; Qpval represents P-value of Qval test statistics; and Q is a statistical magnitude in statistics), the gene was homogeneous and unbiased. Then, the differential expression of the genes was analyzed. Only genes with P<0.05 were considered significant. Finally, the relative fold-change (FC) in expression of each gene between the NPC tissues samples and normal control samples was calculated. Collectively, genes with P<0.05 were identified as DEGs.

Gene Ontology (GO) functional and pathway enrichment analyses

The gene functional analysis tool Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) (21) was used to perform GO [including biological process (BP), cell component (CC) and molecular function (MF)] and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses of DEGs. Only the GO and pathway terms with gene count ≥2 and P<0.05 were considered significant.

Selection of DEGs with DMRs

Based on the gene symbols corresponding to the DMRs and identified DEGs, the overlapped genes between genes with hypermethylated DMRs and downregulated DEGs, and the genes with hypomethylated DMRs and upregulated DEGs were selected.

Functional association analysis of the DEGs with DMRs

The GeneMANIA prediction server (22,23) (http://apps.cytoscape.org/download/stats/genemania/), a plugin in Cytoscape software (version 3.2.1; National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Seattle, WA, USA), was utilized to analyze the correlations among the identified DEGs that had DMRs, based on a large set of functional association data, including protein and genetic interactions, co-expression, co-localization pathways, and protein domain similarity.

Results

Statistics of DMRs, DMIs and DEGs

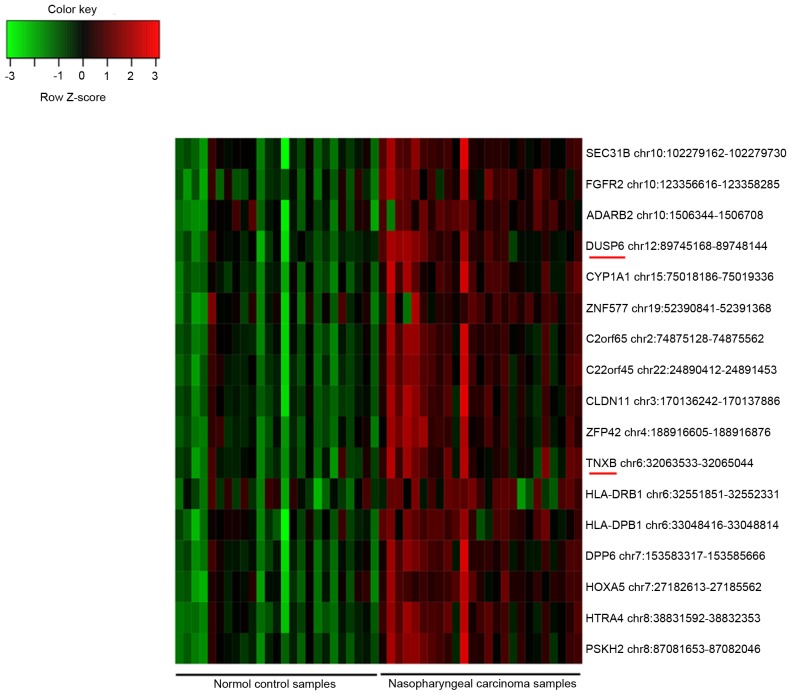

In total, 2,262 probes of DMRs were obtained, including 2,234 hypermethylated CpG site probes corresponding to 1,676 gene symbols and 28 hypomethylated CpG site probes corresponding to 28 gene symbols. Furthermore, 2,983 DEGs were identified, including 1,655 upregulated and 1,328 downregulated genes. Additionally, 17 DMIs were identified, and all of them were hypermethylated in the NPC samples compared with their methylation status in the controls (Fig. 1). Among them, dual specificity phosphatase 6 (DUSP6) and tenascin XB (TNXB) were also identified as DEGs.

Figure 1.

Heatmap of the 17 DMIs. Each row represents a gene that contains DMI, and each column represents a tissue sample. Green indicates hypomethylated, while red indicates hypermethylated. DMIs, differentially methylated CpG islands.

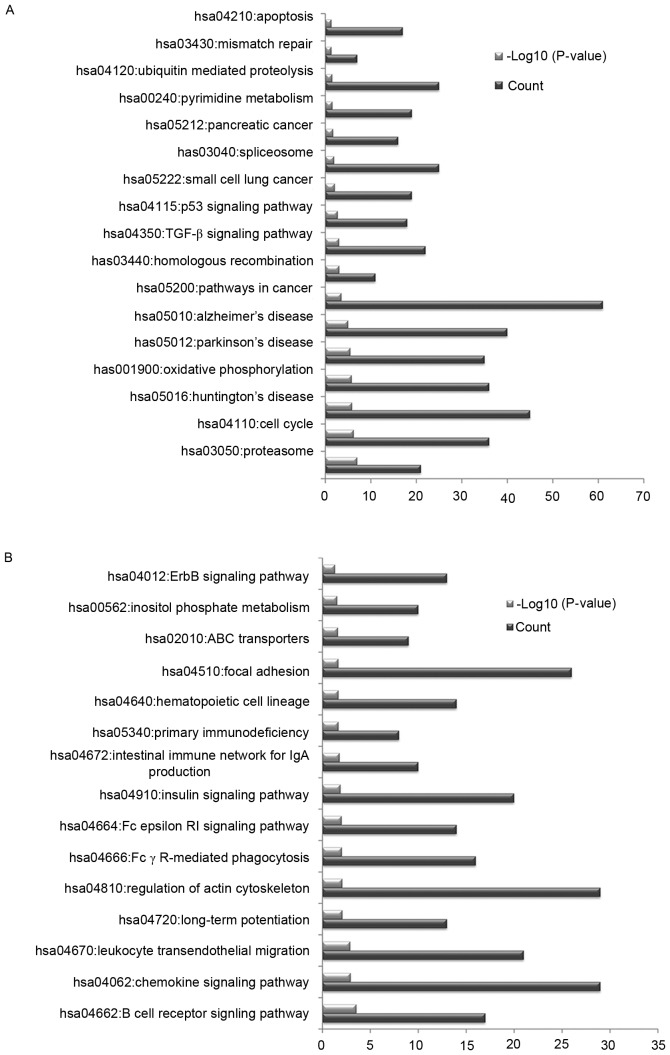

Significant pathways enriched by DEGs

In order to investigate the potential pathways associated with the identified DEGs, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was conducted. The upregulated DEGs were primarily associated with pathways in cancer, oxidative phosphorylation and the cell cycle (Fig. 2A). The downregulated DEGs were primarily associated with the regulation of actin cytoskeleton, chemokine signaling pathway and focal adhesion (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway terms that were significantly enriched by differentially expressed genes. Pathway terms enriched by (A) upregulated and (B) downregulated genes. hsa, Homo sapiens.

Overlapped genes between genes with DMRs and DEGs

In order to reveal whether the genes with DMRs were DEGs, genes with DMRs were compared with DEGs. It was identified that 135 genes with hypermethylated DMRs were downregulated in the NPC samples compared with their expression levels in the normal controls, including prostaglandin D2 synthase, elongation factor for RNA polymerase II 3, ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 3 and claudin 3 (Table I).

Table I.

Information regarding the downregulated genes containing hypermethylated regions.

| Site ID | Chr | Loc | Gene | Island | Mean log2FCa | Mean β-value in NPC samples | Mean β-value in normal samples | Δβ (NPC vs. normal) | FDR (NPC vs. normal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg20450318 | 11 | 65415260 | SIPA1 | chr11:65413778-65415203 | −0.72 | 6.57×10−1 | 4.65×10−1 | 1.92×10−1 | 1.30×10−4 |

| cg17953300 | 11 | 65418265 | chr11:65419853-65420527 | 5.91×10−1 | 4.57×10−1 | 1.34×10−1 | 2.33×10−3 | ||

| cg16915828 | 11 | 73371940 | PLEKHB1 | chr11:73371800-73372632 | −0.59 | 6.19×10−1 | 4.31×10−1 | 1.88×10−1 | 2.93×10−5 |

| cg07223180 | 13 | 20989142 | CRYL1 | chr13:20989007-20989836 | −0.62 | 5.98×10−1 | 4.63×10−1 | 1.35×10−1 | 5.69×10−5 |

| cg21177426 | 15 | 37386586 | MEIS2 | chr15:37387386-37387614 | −0.82 | 6.28×10−1 | 4.68×10−1 | 1.60×10−1 | 1.70×10−5 |

| cg24361265 | 15 | 44068668 | ELL3 | chr15:44068586-44069792 | −1.24 | 6.36×10−1 | 4.32×10−1 | 2.04×10−1 | 2.51×10−5 |

| cg06786050 | 16 | 84401247 | ATP2C2 | chr16:84401957-84402497 | −0.82 | 5.58×10−1 | 4.36×10−1 | 1.22×10−1 | 1.21×10−4 |

| cg26824780 | 16 | 89004908 | CBFA2T3 | chr16:89006334-89008600 | −0.87 | 5.95×10−1 | 4.73×10−1 | 1.23×10−1 | 6.23×10−6 |

| cg09013975 | 17 | 3847872 | ATP2A3 | chr17:3847999-3848570 | −1.06 | 6.68×10−1 | 4.90×10−1 | 1.78×10−1 | 4.51×10−5 |

| cg05247914 | 19 | 35629701 | FXYD1 | chr19:35632356-35632572 | −0.62 | 6.76×10−1 | 4.83×10−1 | 1.93×10−1 | 3.71×10−5 |

| cg03078169 | 19 | 35629791 | chr19:35632356-35632572 | 6.31×10−1 | 4.79×10−1 | 1.52×10−1 | 4.40×10−5 | ||

| cg27461196 | 19 | 35630106 | chr19:35632356-35632572 | 5.59×10−1 | 4.51×10−1 | 1.08×10−1 | 1.81×10−4 | ||

| cg16334795 | 21 | 42538894 | BACE2 | chr21:42539367-42540872 | −0.86 | 6.06×10−1 | 4.51×10−1 | 1.55×10−1 | 1.58×10−5 |

| cg08481491 | 3 | 125900108 | ALDH1L1 | chr3:125898662-125899568 | −0.80 | 5.85×10−1 | 4.46×10−1 | 1.38×10−1 | 1.04×10−4 |

| cg04161526 | 6 | 31696519 | DDAH2 | chr6:31695894-31698245 | −0.63 | 5.65×10−1 | 4.33×10−1 | 1.32×10−1 | 2.25×10−5 |

| cg21286967 | 6 | 31696710 | chr6:31695894-31698245 | 6.01×10−1 | 4.71×10−1 | 1.30×10−1 | 3.27×10−5 | ||

| cg25526039 | 6 | 107813291 | SOBP | chr6:107810066-107812733 | −0.81 | 5.53×10−1 | 4.36×10−1 | 1.17×10−1 | 4.45×10−4 |

| cg24419391 | 7 | 73183516 | CLDN3 | chr7:73183379-73185115 | −1.02 | 5.89×10−1 | 4.67×10−1 | 1.21×10−1 | 1.64×10−3 |

| cg08580268 | 7 | 150038502 | RARRES2 | chr7:150037459-150039031 | −0.94 | 5.66×10−1 | 3.95×10−1 | 1.71×10−1 | 9.63×10−5 |

| cg27494647 | 7 | 150038898 | chr7:150037459-150039031 | 6.14×10−1 | 4.15×10−1 | 1.99×10−1 | 7.82×10−5 | ||

| cg11714502 | 9 | 130640212 | AK1 | chr9:130639738-130640143 | −0.61 | 5.71×10−1 | 4.47×10−1 | 1.24×10−1 | 5.00×10−4 |

| cg02156769 | 9 | 139872246 | PTGDS | chr9:139872237-139873143 | −1.81 | 5.58×10−1 | 4.56×10−1 | 1.01×10−1 | 1.95×10−5 |

| cg07390373 | X | 43741933 | MAOB | chrX:43741299-43741827 | −0.78 | 5.96×10−1 | 4.88×10−1 | 1.08×10−1 | 3.94×10−5 |

| cg05605944 | X | 43741945 | chrX:43741299-43741827 | 5.84×10−1 | 4.62×10−1 | 1.22×10−1 | 1.72×10−5 |

This table lists the genes with |log2 FC|>0.58. Site ID, probe identity of CpG site; Chr, chromosome where probe is located; Loc, location of probe; FC, fold-change; NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma; FDR, false discovery rate.

However, the 28 genes with hypomethylated DMRs were not differentially expressed between the two group samples.

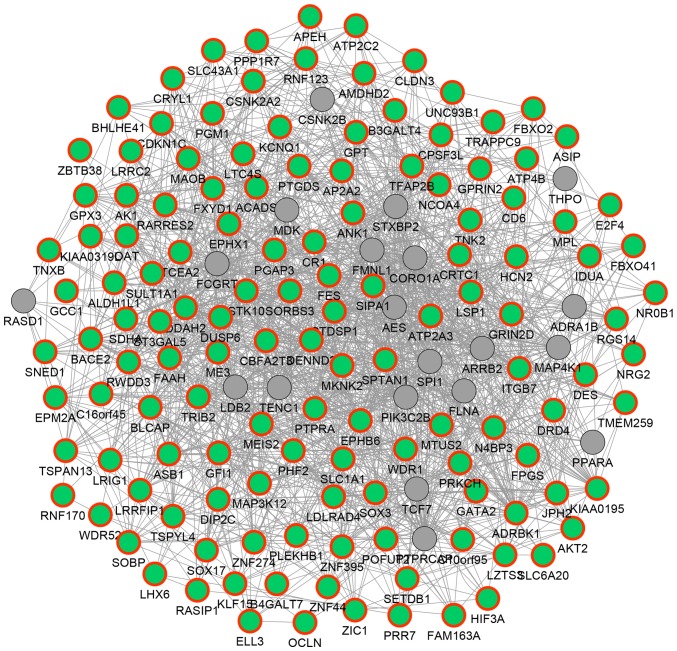

Functional associations of the DEGs with DMRs

In order to reveal the potential functional associations among the above 135 hypermethylated DEGs, a functional network was constructed (Fig. 3). In the network, 154 genes and 1,651 association pairs were included. The association pairs included 1,155 co-expression associations, 24 physical interactions, 351 genetic interactions, 83 co-localization associations and 38 associations between shared protein domains. For example, DUSP6 was predicted to exhibit genetic interactions with other hypermethylated DEGs such as malic enzyme 3 (ME3) and ST3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialytansferase 5 (ST3GAL5); TNXB was predicted to be co-expressed with genes such as EPH receptor B6 (EPHB6), aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member L1 (ALDH1L1) and glutathione peroxidase 3 (GPX3).

Figure 3.

Functional network displaying functional associations of the 135 differentially hypermethylated genes. Green nodes with red outer ring represent the downregulated genes containing hypermethylated regions, while grey nodes represent the non-differentially expressed genes.

According to the enrichment analysis, the 135 hypermethylated DEGs were significantly associated with the GO functions of protein amino acid phosphorylation and phosphate metabolic process, and the tight junction pathway (Table II).

Table II.

Results of GO and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analyses of the 135 downregulated genes containing hypermethylated regions.

| Category | Term | P-value | Gene count | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | GO:0006468~protein amino acid phosphorylation | 0.0021 | 14 | STK10, DRD4, PTPRA, MKNK2, PRKCH, ADRBK1, FES, TRIB2, CSNK2A2, EPHB6, TNK2, CD6, MAP3K12, AKT2 |

| GO:0006796~phosphate metabolic process | 0.0087 | 16 | STK10, DRD4, EPM2A, PTPRA, MKNK2, PRKCH, ADRBK1, FES, TRIB2, CSNK2A2, EPHB6, TNK2, CD6, MAP3K12, AKT2, DUSP6 | |

| GO:0006793~phosphorus metabolic process | 0.0087 | 16 | STK10, DRD4, EPM2A, PTPRA, MKNK2, PRKCH, ADRBK1, FES, TRIB2, CSNK2A2, EPHB6, TNK2, CD6, MAP3K12, AKT2, DUSP6 | |

| GO:0016310~phosphorylation | 0.0096 | 14 | STK10, DRD4, PTPRA, MKNK2, PRKCH, ADRBK1, FES, TRIB2, CSNK2A2, EPHB6, TNK2, CD6, MAP3K12, AKT2 | |

| GO:0006357~regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 0.0113 | 13 | CDKN1C, GATA2, SORBS3, MEIS2, E2F4, CRTC1, TFAP2B, GFI1, TCEA2, LRRFIP1, ELL3, NtnxbR0B1, ZBTB38 | |

| CC | GO:0044459~plasma membrane part | 0.0118 | 27 | FXYD1, OCLN, CLDN3, SLC6A20, DRD4, ADRBK1, PRR7, SORBS3, EPHB6, ANK1, ST3GAL5, ITGB7, GRIN2D, CD6, SLC43A1, KCNQ1, SLC1A1, HCN2, CR1, PTPRA, MAOB, TSPAN13, ACTN3, LSP1, AP2A2, MPL, SPTAN1 |

| GO:0005887~integral to plasma membrane | 0.0166 | 17 | FXYD1, HCN2, CR1, CLDN3, SLC6A20, DRD4, PTPRA, TSPAN13, EPHB6, ST3GAL5, GRIN2D, ITGB7, MPL, CD6, KCNQ1, SLC1A1, SLC43A1 | |

| GO:0031226~intrinsic to plasma membrane | 0.0201 | 17 | FXYD1, HCN2, CR1, CLDN3, SLC6A20, DRD4, PTPRA, TSPAN13, EPHB6, ST3GAL5, GRIN2D, ITGB7, MPL, CD6, KCNQ1, SLC1A1, SLC43A1 | |

| GO:0005626~insoluble fraction | 0.0247 | 13 | DES, JPH2, BACE2, GRIN2D, EPHX1, TSPAN13, ADRBK1, LTC4S, NR0B1, SLC1A1, MAP3K12, SPTAN1, AKT2 | |

| GO:0000267~cell fraction | 0.0336 | 15 | JPH2, TSPAN13, EPHX1, ADRBK1, LTC4S, NR0B1, DES, BACE2, GRIN2D, GPX3, SLC1A1, MAP3K12, AKT2, SPTAN1, DUSP6 | |

| MF | GO:0008134~transcription factor binding | 0.0009 | 13 | ZNF274, E2F4, CRTC1, NR0B1, GATA2, SORBS3, MEIS2, DIP2C, NCOA4, GPX3, TFAP2B, SOX17, DDAH2 |

| GO:0048037~cofactor binding | 0.0156 | 7 | SDHA, CRYL1, ME3, ALDH1L1, ACADS, GPT, OAT | |

| GO:0005200~structural constituent of cytoskeleton | 0.0220 | 4 | SORBS3, ANK1, DES, SPTAN1 | |

| GO:0004672~protein kinase activity | 0.0247 | 11 | CSNK2A2, EPHB6, STK10, MKNK2, PRKCH, ADRBK1, TNK2, FES, MAP3K12, TRIB2, AKT2 | |

| Pathway | hsa04530: Tight junction | 0.0036 | 7 | CSNK2A2, OCLN, CLDN3, PRKCH, ACTN3, SPTAN1, AKT2 |

BP, biological process; CC, cell component; MF, molecular function; GO, Gene Ontology; hsa, Homo sapiens.

Discussion

In the present study, 2,234 hypermethylated CpG site probes corresponding to 1,676 gene symbols, 28 hypomethylated CpG site probes corresponding to 28 gene symbols and 17 DMIs were identified based on analysis of the methylation profiling dataset. Furthermore, 2,983 DEGs (1,655 upregulated and 1,328 downregulated) were identified based on the three gene expression profiling datasets. Among these DEGs, 135 downregulated genes were hypermethylated, including DUSP6 and TNXB, which were also among the 17 DMIs identified.

DUSP6 encodes dual specificity phosphatase 6, also termed mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 3, which belongs to the dual specificity protein phosphatase subfamily (24). Phosphatases in this family inactivate their target kinases, such as members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase superfamily, which are involved in cellular proliferation and differentiation (25). In the present study, DUSP6 was identified to be hypermethylated and downregulated in NPC samples compared with its methylation status in the normal controls, which was consistent with other studies (14,26). DUSP6 has been identified as a tumor suppressor, and it is able to inhibit epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cell invasion by negatively modulating the activity of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase in NPC (26). In the present study, DUSP6 was predicted to exhibit genetic interactions with other hypermethylated DEGs such as ME3 and ST3GAL5. ME3 is a mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate(+) -dependent enzyme (27), and it serves a unique role in tumor mitochondria (28). The protein encoded by ST3GAL5 is a sialyltransferase, a type II membrane protein that catalyzes the formation of α-2,3-sialyltransferase (GM3), a protein participating in cell differentiation and cell adhesion (29). There is no other evidence to indicate the associations of ME3 and ST3GAL5 with NPC at present. Therefore, ME3 and ST3GAL5 may be potential novel biomarker molecules in the progression of NPC.

TNXB was also identified to be hypermethylated and downregulated in NPC samples compared with its methylation status in the normal controls, which was consistent with previous studies (6,12). In Epstein-Barr virus-positive gastric cancer and pancreatic cancer, TNXB was also hypermethylated (30,31). TNXB encodes a tenascin, which exhibits an anti-adhesive effect (32). It is able to promote EMT by activating latent transforming growth factor-β (33). In malignancy, TNXB is usually suppressed, and it has been identified as a marker for malignant mesothelioma (34). Furthermore, in the present study, TNXB was predicted to be co-expressed with a set of other hypermethylated DEGs, including EPHB6, ALDH1L1 and GPX3. EPH receptor B6 (EPHB6) encodes a transmembrane protein, which may affect cell adhesion and migration. In tumor progression, EPHB6 is usually downregulated due to promoter DNA hypermethylation (35,36). It has been suggested that EPHB6 alters invasiveness, and is associated with the prognosis and/or diagnosis of breast carcinoma (35,37). ALDH1L1 and GPX3 have been previously identified to be silenced by methylation, which is associated with tumorigenesis (38,39). Although there is no experimental evidence to confirm the involvement of EPHB6, ALDH1L1 and GPX3 in NPC, the present study hypothesizes that these molecules may also serve a significant role in the progression of NPC, along with TNXB.

Additionally, there are several limitations in the present study. The expression levels and methylation status of the aforementioned genes are required to be validated using experiments. Functional associations of these genes also need to be confirmed. These validations will be performed and presented separately. Despite the absence of experiments, several genes such as ME3, ST3GAL5, EPHB6, ALDH1L1 and GPX3 were primarily identified to be potentially associated with NPC, and they may become novel therapeutic targets for NPC, once validated.

In conclusion, based on the comprehensive analysis of methylation profiling and gene expression profiling, 135 downregulated genes were identified to be hypermethylated in NPC compared with its methylation status in the controls in the present study. Among them, DUSP6 and TNXB contained DMIs. Hypermethylated DEGs that exhibited genetic interactions with DUSP6, including ME3 and ST3GAL5, and genes that co-expressed with TNXB, including EPHB6, ALDH1L1 and GPX3, may be potential novel molecules involved in the progression of NPC, and they may become novel therapeutic targets for NPC.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by a grant from the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province of China (grant no. 201202287).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- NPC

nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- DMRs

differentially methylated regions

- DMIs

differentially methylated CpG islands

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- PCDH8

protocadherin 8

- FEZF2

FEZ family zinc finger 2

- ASS1

argininosuccinate synthetase

- KLHDC4

Kelch domain containing 4

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- BMIQ

β-mixture quantile normalization method

- FC

fold-change

- BP

biological process

- CC

cell component

- MF

molecular function

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- MAP

mitogen-activated protein

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- ME3

malic enzyme 3

- GM3

α-2,3-sialyltransferase

- EPHB6

EPH Receptor B6

- ALDH1L1

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member L1

- GPX3

glutathione peroxidase 3

References

- 1.Hildesheim A, Wang CP. Genetic predisposition factors and nasopharyngeal carcinoma risk: A review of epidemiological association studies, 2000–2011: Rosetta Stone for NPC: Genetics, viral infection, and other environmental factors. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei WI, Sham JS. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2005;365:2041–2054. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang TJ, Riaz N, Cheng SK, Lu JJ, Lee NY. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A review. J Radiat Oncol. 2012;1:129–146. doi: 10.1007/s13566-012-0020-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Wernig M, Hanna J, Sivachenko A, Zhang X, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Jaffe DB, et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irizarry RA, Ladd-Acosta C, Wen B, Wu Z, Montano C, Onyango P, Cui H, Gabo K, Rongione M, Webster M, et al. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue-specific CpG island shores. Nat Genet. 2009;41:178–186. doi: 10.1038/ng.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai W, Cheung AK, Ko JM, Cheng Y, Zheng H, Ngan RK, Ng WT, Lee AW, Yau CC, Lee VH, Lung ML. Comparative methylome analysis in solid tumors reveals aberrant methylation at chromosome 6p in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1079–1090. doi: 10.1002/cam4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He D, Zeng Q, Ren G, Xiang T, Qian Y, Hu Q, Zhu J, Hong S, Hu G. Protocadherin8 is a functional tumor suppressor frequently inactivated by promoter methylation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21:569–575. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328350b097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shu XS, Li L, Ji M, Cheng Y, Ying J, Fan Y, Zhong L, Liu X, Tsao SW, Chan AT, Tao Q. FEZF2, a novel 3p14 tumor suppressor gene, represses oncogene EZH2 and MDM2 expression and is frequently methylated in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:1984–1993. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lan J, Tai HC, Lee SW, Chen TJ, Huang HY, Li CF. Deficiency in expression and epigenetic DNA Methylation of ASS1 gene in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Negative prognostic impact and therapeutic relevance. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou W, Feng X, Ren C, Jiang X, Liu W, Huang W, Liu Z, Li Z, Zeng L, Wang L, et al. Over-expression of BCAT1, a c-Myc target gene, induces cell proliferation, migration and invasion in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:53. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lian YF, Yuan J, Cui Q, Feng QS, Xu M, Bei JX, Zeng YX, Feng L. Upregulation of KLHDC4 predicts a poor prognosis in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sengupta S, den Boon JA, Chen IH, Newton MA, Dahl DB, Chen M, Cheng YJ, Westra WH, Chen CJ, Hildesheim A, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling reveals EBV-associated inhibition of MHC class I expression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7999–8006. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao YN, Cao X, Luo DH, Sun R, Peng LX, Wang L, Yan YP, Zheng LS, Xie P, Cao Y, et al. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor signaling is critical in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell growth and metastasis. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1958–1969. doi: 10.4161/cc.28921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bose S, Yap LF, Fung M, Starzcynski J, Saleh A, Morgan S, Dawson C, Chukwuma MB, Maina E, Buettner M, et al. The ATM tumour suppressor gene is down-regulated in EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Pathol. 2009;217:345–352. doi: 10.1002/path.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norfo R, Zini R, Pennucci V, Bianchi E, Salati S, Guglielmelli P, Bogani C, Fanelli T, Mannarelli C, Rosti V, et al. miRNA-mRNA integrative analysis in primary myelofibrosis CD34+ cells: Role of miR-155/JARID2 axis in abnormal megakaryopoiesis. Blood. 2014;124:e21–e32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-544197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teschendorff AE, Marabita F, Lechner M, Bartlett T, Tegner J, Gomez-Cabrero D, Beck S. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:189–196. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gautier L, Cope L, Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA. Affy-analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:307–315. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smyth GK. Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions using R and Bioconductor. Springer; New York, NY: 2005. Limma: Linear models for microarray data; pp. 397–420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warden CD, Lee H, Tompkins JD, Li X, Wang C, Riggs AD, Yu H, Jove R, Yuan YC. COHCAP: An integrative genomic pipeline for single-nucleotide resolution DNA methylation analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e117. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qi C, Hong L, Cheng Z, Yin Q. Identification of metastasis-associated genes in colorectal cancer using metaDE and survival analysis. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:568–574. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warde-Farley D, Donaldson SL, Comes O, Zuberi K, Badrawi R, Chao P, Franz M, Grouios C, Kazi F, Lopes CT, et al. The GeneMANIA prediction server: Biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W214–W220. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuberi K, Franz M, Rodriguez H, Montojo J, Lopes CT, Bader GD, Morris Q. GeneMANIA prediction server 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W115–W122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith A, Price C, Cullen M, Muda M, King A, Ozanne B, Arkinstall S, Ashworth A. Chromosomal localization of three human dual specificity phosphatase genes (DUSP4, DUSP6 and DUSP7) Genomics. 1997;42:524–527. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jurek A, Amagasaki K, Gembarska A, Heldin CH, Lennartsson J. Negative and positive regulation of MAPK phosphatase 3 controls platelet-derived growth factor-induced Erk activation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4626–4634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong VC, Chen H, Ko JM, Chan KW, Chan YP, Law S, Chua D, Kwong DL, Lung HL, Srivastava G, et al. Tumor suppressor dual-specificity phosphatase 6 (DUSP6) impairs cell invasion and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-associated phenotype. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:83–95. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loeber G, Maurer-Fogy I, Schwendenwein R. Purification, cDNA cloning and heterologous expression of the human mitochondrial NADP(+)-dependent malic enzyme. Biochem J. 1994;304:687–692. doi: 10.1042/bj3040687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wise DR, Thompson CB. Glutamine addiction: A new therapeutic target in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishii A, Ohta M, Watanabe Y, Matsuda K, Ishiyama K, Sakoe K, Nakamura M, Inokuchi J, Sanai Y, Saito M. Expression cloning and functional characterization of human cDNA for ganglioside GM3 synthase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31652–31655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao J, Liang Q, Cheung KF, Kang W, Lung RW, Tong JH, To KF, Sung JJ, Yu J. Genome-wide identification of Epstein-Barr virus-driven promoter methylation profiles of human genes in gastric cancer cells. Cancer. 2013;119:304–312. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimizu H, Horii A, Sunamura M, Motoi F, Egawa S, Unno M, Fukushige S. Identification of epigenetically silenced genes in human pancreatic cancer by a novel method ‘microarray coupled with methyl-CpG targeted transcriptional activation’ (MeTA-array) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;411:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiovaro F, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Chiquet M. Transcriptional regulation of tenascin genes. Cell Adh Migr. 2015;9:34–47. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2015.1008333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alcaraz LB, Exposito JY, Chuvin N, Pommier RM, Cluzel C, Martel S, Sentis S, Bartholin L, Lethias C, Valcourt U. Tenascin-X promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by activating latent TGF-β. J Cell Biol. 2014;205:409–428. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201308031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan Y, Nymoen DA, Stavnes HT, Rosnes AK, Bjørang O, Wu C, Nesland JM, Davidson B. Tenascin-X is a novel diagnostic marker of malignant mesothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1673–1682. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181b6bde3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox BP, Kandpal RP. DNA-based assay for EPHB6 expression in breast carcinoma cells as a potential diagnostic test for detecting tumor cells in circulation. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2010;7:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu J, Bulk E, Ji P, Hascher A, Tang M, Metzger R, Marra A, Serve H, Berdel WE, Wiewroth R, et al. The EPHB6 receptor tyrosine kinase is a metastasis suppressor that is frequently silenced by promoter DNA hypermethylation in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2275–2283. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox BP, Kandpal RP. EphB6 receptor significantly alters invasiveness and other phenotypic characteristics of human breast carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:1706–1713. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He Y, Wang Y, Li P, Zhu S, Wang J, Zhang S. Identification of GPX3 epigenetically silenced by CpG methylation in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:681–688. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oleinik NV, Krupenko NI, Krupenko SA. Epigenetic silencing of ALDH1L1, a metabolic regulator of cellular proliferation, in cancers. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:130–139. doi: 10.1177/1947601911405841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]