Abstract

During the past two decades, mindfulness meditation has gone from being a fringe topic of scientific investigation to being an occasional replacement for psychotherapy, tool of corporate well-being, widely implemented educational practice, and “key to building more resilient soldiers”. Yet the mindfulness movement and empirical evidence supporting it have not gone without criticism. Misinformation and poor methodology associated with past studies of mindfulness may lead public consumers to be harmed, misled, and disappointed. Addressing such concerns, the present article discusses the difficulties of defining mindfulness, delineates the proper scope of research into mindfulness practices, and explicates crucial methodological issues for interpreting results from investigations of mindfulness. For doing so, the authors draw upon their diverse areas of expertise to review the present state of mindfulness research, comprehensively summarizing what we do and do not know, while providing a prescriptive agenda for Contemplative Science, with a particular focus on assessment, mindfulness training, possible adverse effects, and intersection with brain imaging. Our goals are to inform interested scientists, the news media, and the public, in order to minimize harm, curb poor research practices, and staunch the flow of misinformation about the benefits, costs, and future prospects of mindfulness meditation.

Keywords and Phrases: mindfulness, meditation, psychotherapy, neuroimaging, contemplative science, adverse effects, media hype, misinformation

I. Introduction

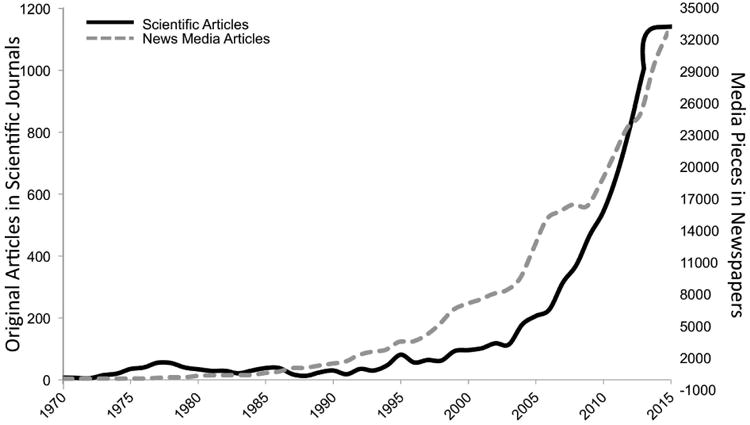

Mindfulness is an umbrella term used to characterize a large number of practices, processes, and characteristics, largely defined in relation to the capacities of attention, awareness, memory/retention, and acceptance/discernment. While the term has its historical footing in Buddhism (cf. Bodhi, 2011; Dunne, 2011; Dreyfus, 2011; Gethin, 2011; Kabat-Zinn, 2011), it has achieved wide-ranging popularity in psychology, psychiatry, medicine, neuroscience, and beyond, initially through its central role in Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR: Kabat-Zinn, 1990) -- an intervention/training ‘package’ introduced in the late 1970s as a complementary therapy for medically ailing individuals (Kabat-Zinn, 2011). The term mindfulness began to gain traction among scientists, clinicians, and scholars as the Mind and Life Institute emerged in 1987 and facilitated formal regular dialogues between the Dalai Lama and prominent scientists and clinicians, as well as regular summer research meetings, the latter starting in 2004 (Kabat-Zinn & Davidson, 2011). In the early 2000s, mindfulness saw an exponential growth trajectory that continues to this day (see Figure 1). The term mindfulness has a plethora of meanings; a reflection of its incredible popularity alongside considerable misinformation and misunderstanding, as well as preliminary support among a general lack of methodologically rigorous research.

Figure 1.

Scientific and news media articles on mindfulness and/or meditation by year from 1970 – 2015. Empirical scientific articles (black line) with the term “mindfulness” or “meditation” in the abstract, title, or keywords, published between 1970 and 2015 were searched using Scopus. Media pieces (dashed gray line) with the terms “mindfulness” or “meditation”, published in newspapers, using a similarity filter to minimize double-counting, published between 1970 and 2015 were searched using LexisNexis.

Mindfulness has become an extremely influential practice for a sizeable subset of the general public, constituting part of Google's business practices (Schaufenbuel, 2015), available as a standard psychotherapy via the National Health Service in the United Kingdom (see Coyne, 2015b), and most recently, part of standard education for approximately 6,000 school children in London (Rhodes, 2015). Additionally, it has become a major area of study across subdisciplines of psychological science, including Social/Personality (Brown & Ryan, 2003), Industrial/Organizational (Dane, 2011), Experimental (Jensen et al. 2012), Clinical (Dimidjian & Segal, 2015), Cognitive (Tang, et al. 2015), Health (Jain et al. 2007), Educational (Britton et al. 2014), and many others. As such, it is critical that we take the term (along with any ambiguities) and the methodological rigor (or lack thereof) with which it has been studied very seriously.

Over the past two decades, writings on mindfulness and meditation practices have saturated the public news media and scientific literature (see Figure 1). While not an isolated case, much popular media fails to accurately represent scientific examination of mindfulness (see e.g., Goyal et al., 2014), making rather exaggerated claims about the potential benefits of mindfulness practices (Gibbs, 2016; Gunderson, 2016). There have even been some portrayals of mindfulness as an essentially universal panacea for various types of human deficiencies and ailments (see e.g., Gunderson, 2016; Huffington, 2013).

As mindfulness has increasingly pervaded every aspect of contemporary society, so have misunderstandings about what it is, whom it helps, and how it affects the mind and brain. At a practical level, the misinformation and propagation of poor research methodology has potential led to people being harmed, cheated, disappointed, and/or disaffected. At a philosophical level, misunderstandings of the work and its implications could limit the potential utility of a method that proposes unique links between first-person data and third-person observations (cf. Lutz & Thompson, 2003). Further, research into a potentially promising arena may be halted for no reason other than that people have become tired of hearing about it (and therefore disinclined to pursue and/or fund it). While there have been many review articles written on mindfulness (e.g., Davidson & Kazniak, 2015; Dimidjian & Segal, 2015; Farb, 2014; Tang, Hölzel, & Posner, 2015), they cannot, by virtue of their limited scope (often focused on specific conditions or topics) and authorship (often limited to a short list of investigators, sometimes with clear conflicts of interest; see e.g., Coyne, 2015b), offer a balanced, consensus perspective. Going beyond prior reviews, the present work provides exposition of the varying definitions of mindfulness, reviews the status of empirical assessment of mindfulness, reviews potential adverse events, considers implications for contemporary clinical practice, discusses specific issues that arise when doing neuroimaging with meditating samples, and elaborates on potential neural differences associated with meditation practices of varying durations.

Two main topics are considered herein: (1) the problem of defining mindfulness and thus delineating the appropriate scope of research on mindfulness practices; and (2) methodological issues in mindfulness research. We provide (a) an overview of the current state in scientific knowledge; (b) a summary of consensus about what the currently available empirical findings do or do not conclusively show; and (c) a proposed prescriptive research agenda for making future scientific progress in understanding the consequences of mindfulness practices.

Our rationale for this expository approach stems from multiple major a priori considerations. We believe that much public confusion and media hype have stemmed from an undifferentiated use of the terms mindfulness and meditation. Each of these terms may refer to an ambiguously broad array of mental states and practices that are associated with a wide variety of secular and religious contexts (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015; Goleman, 1988). Valid interpretation of empirical results from scientific research on such states and practices must take proper account of exactly what types of ‘mindfulness’ and ‘meditation’ are involved (see Section II.C). With current use of umbrella terms, a 5 minute meditation exercise from a popular phone application might be treated the same as a 3-month meditation retreat (both labeled as meditation) and a self-report questionnaire might be equated with the characteristics of someone who has spent decades practicing a particular type of meditation (both labeled as mindfulness).

Furthermore, there is a general failure among the public to recognize that scientific consensus is a complex process requiring considerable time, effort, debate, and (most importantly) data. Throughout the scientific process, the predominant view among scholars can vacillate between being in support of, being agnostic to, and being against, a given idea or theory (Shwed & Bearman, 2010). Eager journalists, academic press offices, and news media outlets – sometimes aided and abetted by researchers – have often over-interpreted initial tentative empirical results as if they were established facts. Moreover, statistically ‘significant’ differences have repeatedly been equated with clinical and/or practical significance (cf. Rosnow & Rosenthal, 1989). These critical considerations need to be incorporated constructively in the future development of best practices for conducting mindfulness research, and for promoting accurate scientific communication with the general public (Britton, 2016).

II. The Problematic Meaning of “Mindfulness”

Despite how it is often portrayed by the media (e.g., Huffington, 2013) and some researchers (Brown & Ryan, 2003), there is neither one universally accepted technical definition of “mindfulness” nor any broad agreement about detailed aspects of the underlying concept to which it refers (Bodhi, 2011; Dreyfus, 2011; Dunne, 2011; Gethin, 2011). Frequently, “mindfulness” simply denotes a mental faculty for being consciously aware and taking account of currently prevailing situations (Kabat-Zinn, 1990; Langer, 1989). At other times, “mindfulness” may refer to formal practice of sitting on a cushion in a specific posture and attending (more or less successfully) to the breath or some other focal object. Considerable disagreement about definitions is not uncommon in the study of complex constructs (for discussion of intelligence, see e.g., Neisser et al., 1996; for discussion of wisdom, see e.g., Walsh, 2015) and mindfulness is no exception. Mindfulness is typically considered to be a mental faculty relating to attention, awareness, retention/memory, and/or discernment (cf. Davidson & Kazniak, 2015), however, these multiple faculties are rarely represented in research practice (Goldberg et al. 2015; Manuel, Somohano, & Bohen, 2016). One of the most thoughtful and frequently invoked definitions, states that mindfulness is moment-to-moment awareness, cultivated by paying attention in a specific way, in the present moment, as non-reactively, non-judgmentally, and open-heartedly as possible (Kabat-Zinn, 1990; Kabat-Zinn, 2011). However, this definition has been described as one of convenience regarding those constructs most readily comprehensible to Western audiences (Kabat-Zinn, 2011).

Alternative semantic interpretations of ‘mindfulness’

Although concerted efforts have been made to provide consensus descriptions of mindfulness (Analayo, 2003; Bishop et al., 2004; Bodhi, 2011; Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007; Grabovac, Lau, & Willett, 2011; Gunaratana, 2002; Hölzel et al., 2011; Malinowski, 2013; Shapiro et al., 2006; Vago & Silbersweig, 2012), there continue to be considerable variations regarding the meaning of ‘mindfulness’. The resulting debates within and across complementary scholarly disciplines that encompass the investigation and practice of mindfulness and meditation more generally are diverse and complex (cf. Contemporary Buddhism, 2011, Vol. 12, Issue 1; Psychological Inquiry, 2007, Vol. 18, Issue 4). Given such considerations, one should not be especially surprised that some people have refrained from accepting Kabat-Zinn's (1990) definition of “mindfulness,” or else have interpreted it in different, sometimes conflicting, ways. Kabat-Zinn (2011) himself has acknowledged that the term represents (to him) a much broader scope of concepts and practices than what his earlier (1990) definition might suggest.

Scientific implications of semantic ambiguity in the meaning of ‘mindfulness’

The ramifications of considerable semantic ambiguity in the meaning of mindfulness are multifarious. Any study that uses the term “mindfulness” must be scrutinized carefully, ascertaining exactly what type of “mindfulness” was involved, and what sorts of explicit instruction were actually given to participants for directing practice, if there was any practice involved. If the definition of mindfulness is based on self-report measures, one should be aware of the nuances of the various measures, how they relate to each other and/or conceptualizations of mindfulness (see Table 1; Sauer et al. 2013; Bergomi, Tschacher, & Kupper, 2013), as well as how different individuals might interpret the items on these measures (cf. Grossman & Van Dam, 2011). It should be further noted that self-reported mindfulness may not relate to the actual practice of mindfulness meditation (cf. Manuel, Somohano, & Bohen, 2016). When formal meditation was used in a study, one ought to consider whether a specifically defined type of mindfulness or other meditation (cf. Lutz et al. 2008) was the target practice (see e.g., Braun, 2013; McMahan, 2008). Additionally, while there is no single definition of mindfulness, it is important to examine whether the authors' specified definition is consistent with their study design (see Section II.C).

Table 1. Mindfulness measures.

| Publication Date | Name | Context | Citation Count1 | Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) | Buddhist Theory | 565 | 1 - General |

|

| ||||

| 2003 | Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MASS) | Self-Determination Theory | 5054 | 1 - Attentiveness & Awareness |

|

| ||||

| 2004 | Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIMS) | Dialectical Behavior Therapy | 1449 | 1 – Observing |

| 2 – Describing | ||||

| 3 –Awareness | ||||

| 4 - Acceptance | ||||

|

| ||||

| 2006 | Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) | CAMS-R, KIMS, FMI, SMQ, MAAS | 2660 | 1 – Nonreactivity |

| 2 – Observing | ||||

| 3 – Awareness | ||||

| 4 – Describing | ||||

| 5 - Nonjudging | ||||

|

| ||||

| 2006 | Toronto Mindfulness Scale (TMS) | Bishop et al. 2004 | 648 | 1 – Curiousity |

| 2 – De-centering | ||||

|

| ||||

| 2007 | Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale, Revised (CAMS-R) | Buddhist Theory & Kabat-Zinn 1990 | 530 | 1 – Attention |

| 2 – Present Focus | ||||

| 3 – Acceptance | ||||

| 4 - Acceptance | ||||

|

| ||||

| 2008 | Philadelpha Mindfulness Scale (PHLMS) | Bishop et al. 2004 | 411 | 1 – Acceptance |

| 2 - Awareness | ||||

|

| ||||

| 2008 | Southhamptom Mindfulness Questionnaire (SMQ) | Kabat-Zinn 1990 and Cognitive Theory | 297 | 1 - General |

|

| ||||

| 2013 | State Mindfulness Scale (SMS) | Buddhist Theory | 35 | 1 – Body Mindfulness |

| 2 – Mind Mindfulness | ||||

Google Scholar, October 20th, 2016

II.A. Consequences of Semantic Ambiguity for Empirical Studies of ‘Mindfulness’

Although most mindfulness training has been derived from the original MBSR model (Kabat-Zinn, 1990), the intensity (hours per day) and duration (total time commitment) of participants' formal practice have varied considerably across different versions of training (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015; Tang et al. 2007; Zeidan et al. 2011). The particular methods for teaching and practicing ‘mindful’ states have varied too. However, published journal abstracts and media reports about obtained results often gloss over such crucial variations, leading to inappropriate comparisons between what might be fundamentally different states, experiences, skills, and practices.

Different definitions of skilled expertise

The definitions of “novice” and “expert” or “adept” (with respect to those with meditation experience) have varied considerably from study to study. Some investigators have considered novices to be individuals with some but not extensive prior formal meditation experience (e.g., up to a few hundred hours of practice; Kozasa et al., 2012; Lutz, Dunne & Davidson, 2007). Others have applied a much stricter criterion, deeming novices only to be individuals with absolutely no prior meditation experience (e.g., Brewer et al., 2011). Further increasing this confusion, some approaches to investigating ‘mindfulness’ (e.g., Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999; Linehan, 1993) do not require any systematic training to become ‘skilled’ in the practice, nor do they require participants to sustain a given experiential state (e.g., present-moment focus, or compassionate engagement) any longer than necessary to achieve a putative beneficial effect.

II.B. Consequences of Semantic Ambiguity for Theoretical Models of ‘Mindfulness’

According to proposed theoretical models of mindfulness, there are clear mental processes and brain mechanisms that might facilitate insight and adaptive personal change, such as psychological distancing/re-perceiving (Shapiro et al., 2006), decentering and inhibitory control (Vago & Silbersweig, 2012), non-conceptual discriminatory awareness (Brown et al., 2007), acceptance and reintegration (Hayes et al., 1999; Linehan, 1993), or focused attention, decentering, and meta-awareness (Lutz, Jha, Dunne, & Saron, 2015; Meyer, 2009). Some of these processes and/or outcomes may be evident on a continuum, suggesting gradual growth with practice over time, whereas others may emerge significantly only in experienced practitioners (i.e., individuals who have engaged in formal sitting meditation or other contemplative practices such as Hatha Yoga, over a lengthy period of time; e.g., van Vugt & Slagter, 2014). Potential changes to various cognitive capacities as a result of mindfulness practice is not specific to clinical contexts; it also informs the limits, capacities, and nature of various cognitive functions and how those functions might be modified. However, the aforementioned complexity, confounding, and confusion that surrounds empirical research on ‘mindfulness’ limits the potential of the method to inform broad questions and inform specific theories. The extent to which a specific model is supported or disconfirmed by particular sets of empirical data or systematic observations depends on the meaning of ‘mindfulness’ that inspired data acquisition. For example, it is nearly impossible to test whether de-centering has occurred if one has not obtained a measure of it. Support for a model will also depend on compliance with experimenter/clinician instructions (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015). No one theoretical model (e.g., Garland, Farb, Goldin, & Fredrickson, 2015; Grabovac et al. 2011; Hölzel et al. 2011; Shapiro et al 2006; Vago & Silbersweig, 2012) can possibly describe, explain, and predict all of the phenomena stemming from the panoply of facets that ‘mindfulness,’ broadly construed, can have. Thus, it will be critical, going forward, to generate new integrative models and to track which data support which models.

II.C. Integrative Assessment

Consensus about the semantic ambiguity of ‘mindfulness’

‘Mindfulness’ does not constitute a unitary construct, though it frequently includes aspects of paying attention in a specific, sustained, non-judgmental way (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). Buddhist scholars suggest it often entails attention, awareness, memory/retention and discernment (cf. Bodhi, 2011; Dreyfus, 2011; Dunne, 2011; Gethin, 2011). Self-report measures often highlight attention, awareness, and acceptance or nonjudgment (rather than discernment; see Table 1). The field, broadly defined, seems to agree that mindfulness entails attention and awareness with some important qualifiers about the nature of those faculties. It is also evident that mindfulness is part of some broader collection of goals and attitudes (Gethin, 2011; Kabat-Zinn, 2011). From a historical perspective, the attitudes qualifying attention and awareness are those accompanying some higher pursuit (e.g., enlightenment), including recognition/awareness, tranquility, concentration, equanimity, energy, joy, and discrimination (Gethin, 2011). Ultimately, degree of fidelity to historical definitions may not necessarily matter to definitions of mindfulness applied in modern practice (Dreyfus, 2011; Gethin, 2011), though historical definitions can provide important context and insight into the nature of mindfulness practice and its potential mechanisms (cf. Kabat-Zinn, 2011). Finally, the type of mindfulness putatively measured by contemporary cross-sectional research is not necessarily the same as what contemporary mindfulness training/meditation seeks to cultivate (see Manuel et al. 2016), which itself can differ from the mindfulness practiced by long-term meditators in various contemplative traditions relative to one another (Grossman & Van Dam, 2011).

Prescriptive research agenda: Transcending the prevalent ambiguity

Given current confusion surrounding “mindfulness,” we urge scientists, practitioners, instructors, and the public news media to move away from relying on the broad, umbrella rubric of “mindfulness” and toward more explicit, differentiated, denotations of exactly what mental states, processes, and functions are being taught, practiced, and investigated. Towards this end, we have provided a non-exhaustive list of defining features for characterization of contemplative and meditation practices (see Table 2). We have divided these features into primary (i.e., critical to most practices) and secondary (i.e., only critical to some practices). While this list is non-exhaustive, common use of this list of descriptors (or a comparable list) would permit the field to move beyond the many ambiguities of definition it is currently facing. Other examples of fundamental feature lists can be found in both scientific (e.g., Lutz et al. 2015) and contemplative (e.g., Analayo, 2003) literatures. For those studies using self-report measures, we encourage users to list the exact measure and to discuss the aspects of ‘mindfulness’ that the utilized measure characterizes (see e.g., Table 1). These suggestions only address terminology and do not necessarily provide ways to overcome the variation in the panoply of contextual factors surrounding mindfulness and/or meditation practice (e.g., type and training of instructor, regularity of meetings, group vs. individual practice, home practice type and amount, etc.). To resolve issues surrounding the implementation of mindfulness and/or other meditation-based training/intervention, we recommend development of something similar to a CONSORT checklist (Moher, Schulz, Altman, 2001) that could be implemented across studies (see Table 3).

Table 2. Non-exhaustive list of defining features for characterization of meditation practice.

| Feature | Definition | Variation in Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Features | ||

| Arousal | Extent of alertness, awakeness, etc. | Low, medium, high |

| Orientation (of Attention) | Where attention is directed | Inward vs. Outward vs. No Orientation |

| Spatial ‘dynamic’ (of Attention) | The quality of attention in space | Fixed (e.g., on an object or location) vs. Moving (e.g., as inthe Body Scan) |

| Temporal ‘dynamic’ (of Attention) | The quality of attention in time | Constant/Stable vs. Rhythmic/Sporadic |

| Object (of Attention) | Attention can be fixed on none, one, two, or many objects | Specific (i.e., defined object(s)) vs. Aspecific (i.e., no well-defined object(s)) vs. None (i.e., no object of attention) |

| Aperture (of Attention) | How ‘sharply’ the spotlight of attention is focused | Narrow vs. Intermediate vs. Diffuse |

| Effort | The extent to which one exerts energy to achieve other features | Low, medium, high |

|

| ||

| Secondary Features | ||

| Complementary Activity | Physical activity to facilitate desired feature(s) | Walking, Mantra recitation, Dancing, Rhythmic movement, etc. |

| Affective Valence | Emotional tone of practice | Positive vs. Neutral vs. Negative |

| Emotional Intention | A desired emotional state (to be cultivated) | Loving-kindness, compassion, forgiveness, generosity, etc. |

| Motivation/Goal | The rationale/reason for the practice | Wellness, mitigation of illness, self-improvement, enlightenment |

| Proficiency Required | Level of skill or expertise necessary | Low, medium, high |

| Posture | Physical orientation of body during practice | Horizontal (e.g., lying down) vs. Intermediate (e.g., sitting) vs. Vertical (e.g., standing) |

Table 3. Non-exhaustive list of study design features for a mindfulness-based intervention.

| Teacher Information |

|

| Practice Information |

|

| General Information |

|

| Participant Info |

|

| Conflicts of Interest |

|

III. Methodological Issues in Mindfulness Meditation Research

Complementing our commentary about the problematic meanings of ‘mindfulness,’ several major methodological issues in mindfulness meditation research should be considered as well. Such consideration is essential to achieve the present goals of providing a more balanced perspective on the pros and cons of practicing mindfulness, and on the weaknesses of currently available empirical findings about its efficacy. Specifically, we are concerned about four distinct but related types of issue: (1) insufficient construct validity in measures of mindfulness; (2) challenges to (clinical) intervention methodology; (3) potential adverse effects from practicing mindfulness; and (4) questionable interpretations of data from Contemplative Neuroscience concerning the mental processes and brain mechanisms underlying mindfulness.

Relation to the ‘Replication Crisis’ in Psychological Science

Worries over scientific integrity and reproducibility of empirical findings have recently come to the fore of both Psychological Science and wider swaths of other basic and applied sciences, receiving considerable attention in both the scientific literature (Button et al., 2013; Ioannidis, 2005, 2012; Miguel et al., 2014; Open Science Collaboration, 2012; Pashler & Wagenmakers, 2012) and public news media (Freedman, 2010; Johnson, 2014a, 2014b; Lehrer, 2010; Nyham, 2014). As part of these developments, debates regarding the efficacy and safety of treatment interventions have also embroiled the behavioral and neuropsychiatric sciences (Baker, McFall, & Shoham, 2008; Fanelli, 2010; Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2011; Button et al., 2013; Ioannidis, 2005; Munafò, Stothart, & Flint, 2009; Yarkoni, Poldrack, Van Essen, & Wager, 2010). Although our present focus is on methodological issues to which mindfulness research is especially vulnerable, it is important to take account of this broader self-examination currently underway in the scientific community. Contemplative Science (i.e., the scientific study of contemplative practices including, but not limited to, mindfulness meditation), is particularly vulnerable to “hype” of various sorts (i.e., tendencies to tout exaggerated positive and negative claims).

III.A. Insufficient Construct Validity in Measuring Mindfulness

One of the disclaimers on offer here concerns construct validity in measuring mindfulness. For obvious reasons, this concern is crucial to our present objectives. Lacking reasonably validated mindfulness measures, one can neither properly determine how this mental faculty changes through instructions and guided practice, nor can one assess how increased mindfulness affects the cognitive capacities and/or symptoms of various mental and physical dysfunctions.

Difficulties in operationalizing and measuring mindfulness

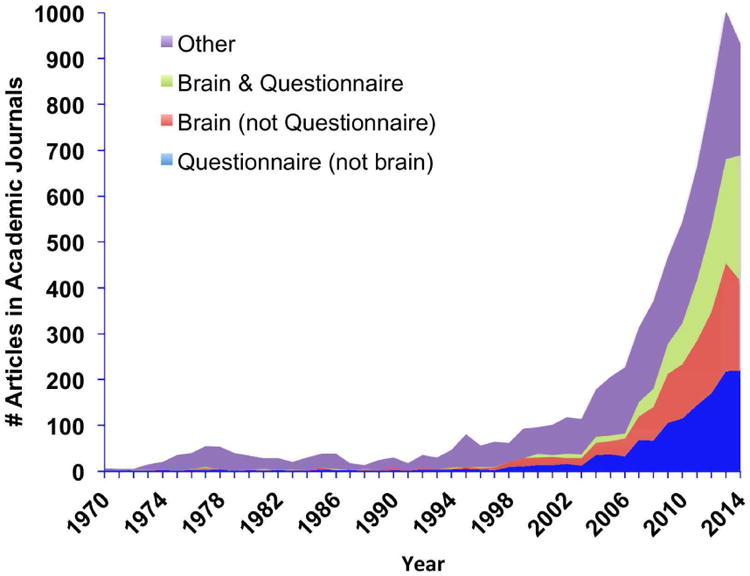

Given the aforementioned absence of consensus regarding definitions of ‘mindfulness,’ the operationalization and measurement of mindfulness are challenging endeavors. These difficulties have propagated to affect both (1) mindfulness practice, and (2) assessments of mindfulness as a mental state or personality trait. Different researchers have implemented varying mindfulness training approaches across studies (e.g., Davidson, 2010), creating challenges for identifying common effects. We are especially concerned about attempts to measure mindfulness via self-report (see e.g., Grossman & Van Dam, 2011) because, as Figure 2 indicates, a large fraction of recent research studies has used questionnaires for their primary assessment of mindfulness (consistent with a broader trend towards measuring psychological constructs via self-report; e.g., Baumeister, Vohs, & Funder, 2007).

Figure 2.

Articles in academic journals by content type. Scopus search limited to articles in academic journals only, published between 1970 and 2014, keywords “mindfulness” or “meditation” for overall search. Brain NOT Questionnaire and Questionnaire NOT Brain as additional key terms.

Problematic aspects of self-report questionnaires

A major challenge to construct validity in psychological assessment is due to reluctance of the field to move beyond logical positivism, a philosophical position that suggests theories are direct derivations of that which can be empirically observed (Green, 1992). Fueled by the prominence of behaviorism, which continues to play a prominent role in contemporary psychology (see e.g., Plaud, 2001), the logical positivistic approach posits that a given measure is equivalent to the construct it purports to measure. In contrast, an alternative, nonjustificationist view suggests that a given measure is merely an approximation of a construct (Embretson, 1983; Strauss & Smith, 2009). Importantly, philosophical views on construct validity can influence the ways that measures are designed and validated. One contemporary extension of logical positivism (which itself would reject the very idea of a construct) seems to be that nomothetic span (e.g., the extent to which a measure converges or diverges from other measures that are related or unrelated, respectively) is all that is needed for construct validity. In contrast to the positivistic view, construct representation (e.g., the psychological processes that give rise to responses on measures that purport to measure the construct) is critical to construct validity (Embretson, 1983; Strauss & Smith, 2009).

Questionnaire-based scales that purport to measure mindfulness offer, at best, modest evidence of nomothetic span. Mindfulness does reliably correlate with other constructs such as emotional intelligence, self-compassion, psychological symptoms, thought suppression, emotion regulation, alexithymia, dissociation, and absent-mindedness (e.g., Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006). However, these findings may actually be suggestive of a lack of differentiation from broad features of personality and temperament; meta-analysis of mindfulness measures suggests a strong negative relationship to neuroticism and negative affect (Giluk, 2009). Alternatively, it may suggest that at least some measures of mindfulness relate to general vulnerabilities or skills that are developed across interventions. In other words, these vulnerabilities and/or skills may not be specifically related to mindfulness; an idea supported by increases in mindfulness across both MBSR and an active control condition (Goldberg et al. 2015).

Additional psychometric concerns, largely relating to construct representation, about self-report mindfulness also exist. Notably, several of these scales exhibit different factor structures and response properties between meditators and non-meditators (e.g., Christopher, Charoensuk, Gilbert, Neary, & Pearce, 2009; Van Dam, Earleywine, & Danoff-Burg, 2009), as well as before and after mindfulness training (e.g., Gu, Strauss, Crane, Barnhofer, Karl, Cavanaugh, & Kuyken, 2016). These findings suggest lack of equivalence on a common underlying latent variable, as well as change in how the items are interpreted. One possible reason for this has to do with demand characteristics; one who has practiced mindfulness meditation may understand and value items differently than someone who has not practiced (though see Baer, Samuel, & Lykins, 2011) – a potential conflation of desire to be ‘mindful’ with actually being ‘mindful’ (cf. Grossman, 2011). Of additional concern, mindfulness measures have not always favored the group one might expect to be more mindful; in one case, experienced meditators were less ‘mindful’ than binge-drinkers (Leigh, Bowen, & Marlatt, 2005). Moreover, mindfulness questionnaires do not always correlate with mindfulness meditation practice (Manuel et al. 2016) and the underlying latent variable influencing item response on certain scales may be reflective of some general feature such as inattentiveness (Van Dam et al. 2010).

Self-report based measures of mindfulness may be particularly vulnerable to limitations of introspection because participants may not know exactly which aspects of mental states should be taken into account when making personal assessments. Moreover, making ‘on-line’ judgments about degrees of mindfulness requires a special kind of multi-tasking (Meyer, 2009). In addition, social-desirability biases may be especially pronounced in self-reports about ‘mindfulness’. This is because participants/patients often learn to expect/value improved attention, equanimity, and so forth, while experimenters often fail to hide their hopes that participants will grow in their adeptness at these mental faculties (cf. Jensen, Vangkilde, Frokjaer, & Hasselbalch, 2012).

Consensus about construct validity in measuring ‘mindfulness’

Some promise exists towards more accurate mindfulness measures via subjective report of behavioral indicators (e.g., breath counting; Frewen, Evans, Maraj, Dozois, & Patridge, 2007; Frewen, Lundberg, MacKinley, & Wrath, 2011; Levinson, Stoll, Kindy, Merry, & Davidson, 2014). Yet potential pitfalls exist even in these new measures (Ring, Brener, Knapp, & Mailloux, 2015). Although some self-report questionnaire measures of mindfulness seem to be effective in revealing particular mental and physical changes associated with practicing mindfulness (e.g., Baer, 2011), how closely these measures track exactly what is taught during practice remains unclear. While some investigators have suggested that increased mindfulness improves the quality of participants' introspections (Lutz et al., 2007; Mrazek, Smallwood, & Schooler, 2012; Zanesco, King, MacLean, & Saron, 2013), this claim has not been well established (cf. Fox et al., 2012; Levinson et al., 2014; Sze, Gyurak, Yuan, & Levenson, 2010; Whitmarsh, Barendregt, Schoffelen, & Jensen, 2014). Nor is it entirely obvious how one could veridically establish such a claim, for doing so would require accurate ‘third-person’ evidence about the subjective contents of an introspector's ‘first-person’ consciousness (cf. Lutz, Lachaux, Martinerie, & Varela, 2002). Ironically, were it shown that mindfulness practice improves the quality of participants' introspections, this might deepen other problems in mindfulness research. For example, if mindfulness-based enhancements of introspective accuracy are real, such enhancements could increase honest responding, thereby exacerbating between group confounds.

Perhaps because of such pitfalls in introspection, many studies have focused instead on neurobehavioral performance, attempting to assess mindfulness indirectly (e.g., Brewer et al. 2011; Ferrarelli et al. 2013; Jha et al. 2007; Lao et al. 2016; Lutz et al. 2009; Sahdra et al. 2011). However, these studies have inconsistent and sometimes contradictory empirical findings about the effects of mindfulness training on various basic cognitive and behavioral capacities (e.g., Lao et al. 2016; Jha et al. 2007). Several studies that involved different types of mindfulness training have found modest improvements in the efficiency of attention, orienting, and executive cognitive control after varying types of practice (Jha, Krompinger, & Baime, 2007; Sahdra et al., 2011; Slagter et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2007; van den Hurk, Giommi, Gielen, Speckens, & Barendregt, 2010). Even when statistically significant, the magnitudes of observed cognitive effects stemming from mindfulness practices have been rather small (Chiesa, Calati, & Serretti, 2011; Sedlmeier et al., 2012).

Prescriptive research agenda: Measuring aspects of mindfulness

Given the cultural history and multitude of contextual variations in the term ‘mindfulness,’ scientific research on the aggregate of mental states labeled by it would benefit from redirecting attempts to directly measure mindfulness towards measuring supporting mental faculties. The situation is similar to the psychological study of ‘intelligence’. Because of complexities, historical efforts to obtain a single unitary measure of general intelligence evolved to studying particular cognitive capacities, that, in combination, may make people functionally more or less intelligent (cf. Neisser et al. 1996).

Paralleling such evolution, we recommend that future research on mindfulness aim to produce a body of work for describing and explaining what biological, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and social, as well as other such mental and physical functions change with mindfulness training. There are two broadly useful contexts in which to approach this problem. The first is to use a multimodal approach wherein first- and third-person (i.e., neurobiological and/or behavioral) assessments are used to mutually inform and identify one another (cf. Lutz et al. 2002; Lutz et al. 2015). This comprises a more theory-driven approach to the problem of understanding mindfulness. A data-driven alternative might be comparable to how individuals in affective neuroscience have used advanced algorithms to integrate physiological and neurobiological signals towards understanding emotional states (cf. Kragel & LaBar, 2014). A second context is to focus on the indirect impact of mindfulness practice, such as how meditation practice might lead to more effective therapists via assessing patient outcome (cf. Grepmair et al., 2007) or how mindfulness might improve caregiver efficacy via assessment of significant others (cf. Singh et al., 2004). Another approach within this domain might be to examine how mindfulness practice can lead to changes in observable behaviors such as eating patterns or interpersonal exchanges (Papies, Pronk, Keesman, & Barsalou, 2015), the latter especially as reported by friends or partners of those undergoing mindfulness and/or meditation training (e.g., Birnie, Garland, & Carlson, 2010). In addition, researchers should situate future process models of mindfulness within extant rigorous theoretical frameworks for cognition and emotion whereby empirical predictions and falsifiable conceptual hypotheses can be tested (e.g., Meyer, 2009; van Vugt, Taatgen, Bastian, & Sackur, 2015; Vago & Silbersweig, 2012). Frameworks based on computational modeling may be especially helpful for such purposes (e.g., Anderson et al., 2004; Meyer & Kieras, 1999).

III.B. Challenges for Clinical Intervention Methodology

Numerous intervention studies have been conducted to assess whether, and by how much, practicing mindfulness may help alleviate various undesirable mental and physical conditions, including pain, stress, anxiety, depression, obesity, addiction, and others. Dimidjian and Segal (2015) estimate, using the NIH stage model for Clinical Science (Onken, Carroll, Shoham, Cuthbert, & Riddle, 2014), that only 30% of research using mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) has moved beyond Stage 1 (Intervention Generation/Refinement). The majority (20%) of research beyond Stage 1 has been conducted at Stage 2a (Efficacy in research clinic: compared to wait-list control or treatment as usual) with a mere 9% (of the total) at Stage 2b (Efficacy in research clinic: compared to active control). Moreover, only 1% of all research has been conducted outside research contexts, a woefully inadequate research base to inform whether MBIs are ready for use in regular clinical practice, as is the case in the UK (Coyne, 2015b; 2016). As a result, some have blatantly stated that, “widespread use is premature” (Greenberg & Harris, 2012).

Haphazard variability across MBIs

Given the lack of consensus about what ‘mindfulness’ means and how it should be operationalized, MBIs have varied greatly in the diverse types of practice, methods of participant training, and duration of instructional courses associated with them. The ‘gold-standard model’ of a MBI has been the eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 1990) course, involving 20-26 hours of formal meditation training during 8 weekly group classes (1.5-2.5 hrs/class), one all-day (6 hr) class, and home practice (∼45 min/day, 6 days/week). Throughout the eight weeks, formal MBSR training has included an eclectic set of specific mindfulness practices – focused attention (FA) on the breath, open monitoring (OM) of awareness in ‘body-scanning’ (cf. Lutz, Slagter, Dunne, & Davidson, 2008), prosocial meditation (e.g., loving-kindness and compassion), and gentle Hatha Yoga.

‘Spin-off’ MBIs vary in content and form depending on the participant populations for which they were adapted and the accompanying idiosyncratic objectives of individual investigators (cf. Shonin, Van Gordin, & Griffiths, 2013). For example, interventions such as Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT; Segal et al., 2002) have incorporated aspects of cognitive behavioral therapy (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, widely considered the most researched and empirically-based psychotherapy, focuses on the relationship between thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, most commonly with a focus on changing thought and behavioral patterns; Tolin, 2010). Notably, there are also a number of psychotherapies that draw on ‘mindful’ principles, but are more commonly associated with traditional cognitive behavioral therapy (cf. Hofmann & Asmundson, 2008); these include Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al. 1999) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; Linehan et al. 1993). We focus our discussions of MBIs on those interventions that utilize formal meditation techniques (namely, derivatives of MBSR), as they arguably differ in origin from those interventions more closely tied to cognitive and/or behavioral therapy (cf. Dimidjian & Segal, 2015; Hayes, 2002; Kabat-Zinn, 2011; Robins, 2002). Moreover, interventions that formally employ meditation practices differ in therapeutic delivery from those that do not formally employ such practices, though this distinction has become muddied as mindfulness and meditation have enjoyed greater mainstream popularity.

The duration of MBIs have been altered dramatically to conform with brief training regimens that may involve as few as four 20-min sessions (e.g., Papies, Barsalou, & Custers, 2012; Zeidan, Emerson, Farris, Ray, Jung, McHaffie, & Coghill, 2015). Some newer MBIs have even implemented web-based or mobile applications for treatment delivery (Cavanaugh et al., 2013; Dimidjian et al., 2014; Lim, Condon, & DeSteno, 2015). Given the variety of practices that fall under the umbrella of MBI, the adoption of mindfulness as a prescriptive clinical treatment has not entailed a consistent type of intervention. While there is considerable variability in other practices of psychotherapy as well, specific classes of intervention (e.g., CBT) at least tend to have sufficient consistency with one another (in terms of content and format) to provide a basis for broad evaluation of their efficacy (cf. Tolin, 2010). In contrast, the varieties of interventions labeled as “mindful”, are as varied as the definitions of the construct (differing in content, meeting type/frequency, instructions, homework, readings, instructor/therapist training and accessibility, etc.). Extreme caution must be exercised when considering mainstream implementation of minimally-tested adaptations of more traditional MBIs (Dimidjian & Segal, 2015).

Misperceptions of therapeutic efficacy

Despite the preceding list of concerns, there is a common misperception in public and government domains that compelling clinical evidence exists for the broad and strong efficacy of mindfulness as a therapeutic intervention (e.g., Freeman, D. & Freeman, J, 2015; Coyne, 2016). Results from some clinical studies conducted over the past ten years have indicated that MBCT may be modestly helpful for some individuals with residual symptoms of depression (Eisendrath et al., 2008; Geschwind, Peeters, Huibers, van Os, & Wichers, 2012; van Aalderen et al., 2012). As a consequence of select results, published in high profile journals, MBCT is now officially endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association for preventing relapse in remitted patients who have had three or more previous episodes of depression. Moreover, the United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence now even recommends MBCT over other more conventional treatments (e.g., SSRIs) for preventing depressive relapse (Crane & Kuyken, 2012). Mitigating such endorsements, a recent meta-analysis found that MBSR did not generally benefit patients susceptible to relapses of depression (Strauss, Cavanagh, Oliver, & Pettman, 2014). Other meta-analysis have suggested general efficacy of MBIs for depressive and anxious symptoms (Hofmann et al. 2010), though head-to-head comparisons of MBIs to other evidence-based practices have resulted in mixed findings, some suggesting comparable outcomes, others suggesting MBIs might be superior in certain conditions, and others suggesting CBT is superior in certain conditions (e.g., Arch et al., 2013; Goldin et al. 2016; Manicavascar et al. 2011). There is also mixed evidence comparing MBIs to interventions such as progressive muscle relaxation (e.g., Agee et al. 2009; Jain et al. 2007). Direct comparisons of MBIs to empirically established treatments are limited.

In a recent review and meta-analysis commissioned by the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), MBIs (compared to active controls) were found to have a mixture of only moderate, low, or no efficacy, depending on the disorder being treated. Specifically, the efficacy of mindfulness was only moderate in reducing symptoms of anxiety, depression, and pain. Also, efficacy was low in reducing stress and improving quality of life. There was no effect or insufficient evidence for attention, positive mood, substance abuse, eating habits, sleep, and weight control (Goyal et al., 2014). These and other limitations echoed those from a report issued just seven years earlier (Ospina et al., 2007). The lack of improvement over these seven years in the rigor of the methods used to validate MBIs is concerning; indeed if research does not extend beyond Stage 2A (comparison of MBI to wait-list control), it will be difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain whether MBIs are effective in the real world (cf. Dimidjian & Segal, 2015). On balance, much more research will be needed before we know for what mental and physical disorders, in which individuals, MBIs are definitively helpful.

Consensus about clinical intervention methodology

MBIs are sometimes misleadingly described as “comparable” to antidepressant medications (ADMs)(Goyal et al., 2014). Such comparability has been tentatively supported by results from studies examining MBIs vs. ADMs for depressive relapse in recurrent depression (Segal et al., 2010; Kuyken et al., 2015). Notably, there are large individual differences in efficacy: MBIs may be beneficial for some people, but instead may be ineffective or contraindicated for others (Dobkin, Irving, & Amar, 2011). Special care is therefore needed when interpreting results from clinical studies employing MBIs, many of which have lacked ‘active’ control conditions. Given the absence of scientific rigor in much clinical mindfulness research (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015; Goyal et al., 2014), evidence for use of MBIs in clinical contexts should be considered preliminary.

The official standards of practice for MBSR exclude suicidality and the presence of any psychiatric disorder (Santorelli, 2014). Case-by-case exceptions are permissible by these standards if, and only if, an individual participant is willing and able to simultaneously maintain adequate medical treatment for the exclusionary condition or if an instructor has sufficient clinical training to manage the case at hand (Santorelli, 2014). The American Psychiatric Association (Shapiro, 1982), US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (NCCAM/NIH, 2014), and leading researchers in the field (Dobkin et al., 2011; Greenberg & Harris, 2012; Lustyk et al., 2009) have expressed concerns that meditation may be contraindicated under several circumstances. Numerous authors have recommended that Schizophrenia spectrum disorders, Bipolar disorder, Post-traumatic stress disorder, Depression, and risk-factors for psychosis (e.g., Schizoid personality disorder) are contraindications to participation in an MBI that is not specifically tailored to one of these conditions (Didonna & Gonzalez, 2009; Dobkin et al. 2012; Germer, 2005; Kuijpers et al. 2007; Lustyk et al. 2009; Manocha, 2000; Walsh & Roche, 1979; Yorston, 2001). The rationale for these contraindications is that without sufficient clinical monitoring, an intervention not designed to address these issues could lead to deterioration or worse. Such contraindications should be considered exclusionary criteria for regular clinical practice until substantially more evidence about the efficacy of various MBIs becomes available.

Prescriptive research agenda: Strengthening clinical intervention methods

Replication of earlier studies with appropriately randomized designs and proper active control groups will be absolutely crucial. In conducting this work, we recommend that researchers provide explicit detail of mindfulness measures (e.g., see Table 1), primary outcome measures, mindfulness/meditation practices (see Table 2), and intervention protocol (see Table 3). While active control groups for MBIs can be difficult to implement for a variety of reasons (Davidson & Kazniak, 2015), the problem is not insurmountable (see e.g., MacCoon et al. 2012) and has been resolved by those conducting more traditional psychotherapy research (e.g., Arch et al., 2013; Agee et al. 2009; Goldin et al. 2016; Jain et al. 2007; Manicavascar et al. 2011). Additionally, researchers must be explicit about the exact hypothesis they are testing (non-inferiority to an established treatment, superiority to an established treatment, etc.) and consider the various limitations that might accompany treatment designs (see e.g., Coyne, 2015a).

Because of potential confirmation biases (Rosnow, 2002) and allegiance effects (Martin, Garske, & Davis, 2000), clinical research ideally would involve multidisciplinary teams of investigators. These teams should consist not only of clinicians, but also basic research scientists, scholars from within classical mindfulness traditions, and scientists/scholars skeptical about mindfulness's efficacy. An especially compelling research strategy could involve adversarial collaboration (see e.g., Matzke et al., 2015). Moreover, future clinical studies should not rely merely on self-report and assessments by clinicians, but also incorporate biological and behavioral efficacy measures.

III.C. Harm, Adverse Effects, and Fallout of Meditation Practices

Much of the public news media has touted mindfulness as a universal panacea for what ails human kind (e.g., Chan, 2013; Firestone, 2013), overlooking the very real potential for several different types of harm. According to Directors of the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine (NCCIH) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the biggest potentials for harm of complementary treatments (e.g., meditation) are “unjustified claims of benefit, possible adverse effects…and the possibility that vulnerable patients with serious diseases may be misled” (Briggs, & Killen, 2013). Identifying “harm”, “side effects”, or “adverse effects” is complicated by issues related to definitions and measurement, which will be addressed in turn.

Coming to terms with meditation-related adverse effects

An adverse effect or event (AE) is any unwanted, harmful effect that results from, but is not the stated goal of a given treatment. A side effect is any unexpected effect that is secondary to the intended effect of the treatment (Linden, 2013). An event can also be categorized a “side effect” if it is not described in the “product labeling”, “package insert”, “marketing or advertising” (NIA, 2011; OHRP, 2007) – descriptions that are often lacking for meditation practices (and behavioral interventions more generally, despite a comparable incidence of AEs to pharmacological treatments; Crawford et al., 2016; Linden, 2013; Mohr, 1995; Moos, 2005, 2012). Whether the result of correct or incorrect treatment, a treatment-emergent reaction may include the appearance of novel symptoms that did not exist before treatment, or the exacerbation or re-emergence of a pre-existing condition. Treatment non-response or deterioration of (target) illness may or may not be caused by the treatment (Linden, 2013) but requires both reporting and action.

Meditation-related experiences that were serious or distressing enough to warrant additional treatment or medical attention have been reported in more than 20 published case reports or observational studies. These reports document instances of meditation-related or “meditation-induced” (i.e., occurring in close temporal proximity to meditation and causally attributed to meditation by the practitioner, instructor, or both) psychosis, mania, depersonalization, anxiety, panic, traumatic-memory re-experiencing, and other forms of clinical deterioration (Boorstein, 1996; Carrington, 1977; Castillo, 1990; Chan-Ob, & Boonyanaruthee, 1999; Disayavanish, & Disayavanish, 1984; Epstein, & Lieff, 1981; Heide, & Borkovec, 1983; Kerr et al., 2011; Kornfield, 1979; Kuijpers et al., 2007; Kutz et al., 1985; Lomas et al., 2014; Miller, 1993; Nakaya, & Ohmori, 2010; Sethi, 2003; Shapiro, 1992; Shonin et al., 2014; Shonin et al, 2014; Van Nuys, 1973; VanderKooi, 1997; Walsh, & Roche, 1979; Yorston, 2001). Many of the aforementioned were case studies, case series, or observational studies, often without a control group. Only two were prospective (Shapiro, 1992; Shonin et al 2014). Detailed clinical histories were available for some of the subjects, but not all, which makes the question of pre-existing conditions difficult to evaluate. While qualitative reports and case studies are an appropriate and necessary first step in identifying potential AEs (Dimidjian, & Hollon, 2010), the need for AE assessments within more rigorous designs such as randomized controlled trials would provide more conclusive information.

Issues in the measurement of adverse effects

Since safety reporting is required for federally funded clinical trials, one might expect that the many National Institute of Health (NIH) funded mindfulness or meditation trials would be a rich source of information about potential adverse effects with causality assessment inherent in randomized controlled trial (RCT) design. However, most current methods for assessing AEs in meditation-related research are insufficient to produce an accurate estimate. Despite CONSORT requirements (Moher et al., 2001), and compared to 100% of pharmacology trials (Vaughan et al., 2014), less than 25% of meditation trials actively assess AEs (Goyal et al., 2014; Jonsson et al., 2014), relying instead on spontaneous reporting, which may underestimate AE frequency by more than 20-fold (Bent et al., 2006), and results in widely varying AE rates, even for similar trials (Kuyken et al., 2015; Kuyken et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2014). Different AE assessment methods (Vaughan et al., 2014) or specifically the lack of systematic AE assessment in meditation trials, has led not only to the hasty erroneous conclusion that meditation is free of AEs (Turner et al., 2011), but also that meditation interventions can act as a replacement to medication for mental illnesses such as depression and bipolar disorder (Annels et al., 2016; Strawn et al., 2016; Walton, 2014) with slogans such as, “meditate not medicate” (Annels et al., 2016). Furthermore, meditation-related AEs are discussed in many traditional (largely Buddhist) meditation guides (Buddhaghosa, 1991; Sayadaw, 1965; Wallace, 2011). Despite the assumption of “wide acceptance of minimal, if any, adverse events associated with meditation” (Turner et al., 2011), this assumption is largely based on a lack of research rather than substantive evidence.

Other potential risks of mindfulness meditation

The benefits and the safety of meditation are likely exaggerated beyond available evidence in a manner that increases “the possibility that vulnerable patients with serious diseases may be misled” (Briggs, & Killen, 2013). In the face of such exaggerated claims, patients may be diverted from pursuing other, more traditional activities (e.g., regular aerobic exercising) that typically yield physical and mental benefits (Cotman, Berchtold, & Christie, 2007; Penedo & Dahn, 2005) or standard treatments (e.g., psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy) that are better suited to dealing with particular psychiatric conditions. For example, in a recent meta-analysis of MBIs Strauss et al (2014) concluded, “…given the paucity of evidence in their favour, we would caution against offering MBIs as a first line intervention for people experiencing a primary anxiety disorder… findings from the current meta-analysis would suggest great caution if offering MBIs to this population as a first line intervention instead of a well-established therapy” (Strauss et al., 2014). In economics, as well as recent discussions of psychotherapy, this effect has been labeled an “opportunity cost” (i.e., time and money invested in a treatment approach that has little to no therapeutic benefit relative to the potential time/money that could have been invested in a treatment more likely to yield improvement; cf. Lilienfeld, Lynn, & Lohr, 2003). Given that relief from anxiety is probably one of most widely promoted benefits of mindfulness (see e.g., Hofmann et al. 2010), opportunity cost may be a widespread “side effect” of MBI hype.

Consensus about harm, adverse effects, and contraindications

To date, “official” clinical guidelines about the state of meditation-related risks are in their infancy and only a handful of organizations and regulatory agencies have issued any statements. The American Psychiatric Association first showed concern about meditation-related adverse effects in 1977, and commissioned a report on the topic with treatment guidelines (Shapiro, 1982). The APA also included descriptions of meditation-induced depersonalization and other clinically relevant problems in both the 4th and 5th editions of their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; APA, 1994, 2013). The NIH states that “meditation could cause or worsen certain psychiatric problems” but does not provide any practice guidelines beyond a boilerplate disclaimer to “check with your doctor” before trying meditation (NCCIH, 2016).

Since neither meditation-writ-large nor meditation-based interventions are overseen by any regulatory agencies, most of the clinical guidelines and recommendations regarding risk and safety have been issued by the “Centers for Mindfulness”, creators of interventions, as well as various experts in the field. Many meditation researchers and clinicians have offered reviews of meditation-related risks, adverse effects or contraindications with recommendations for clinical guidelines (Dobkin et al., 2012; Fenwick, 1983; Greenberg, & Harris, 2012; Hanley et al., 2016; Lustyk et al., 2009; Shapiro, 1982; Shonin et al., 2014). The MBCT Implementation Resources (Kuyken et al 2012) is one of the first documents to list potential “risks to participants”, including increased likelihood of suicidality, depression, negative emotions, and flashbacks during meditation for individuals with trauma histories. At present, management strategies for potential risks have been largely limited to exclusion and informed consent. Both the University of Massachusetts Center for Mindfulness and the Oxford Mindfulness Centre have published recommended exclusion criteria for standard MBSR and MBCT, both excluding current suicidality and/or any current psychiatric disorder (Kuyken et al., 2012; Santorelli, 2014). In addition, many centers attempt to make clear that mindfulness is not intended to replace standard psychiatric care.

Prescriptive research agenda: Transcending adverse effects

The current guidelines, while preliminary, represent substantial progress in assessing and promoting safety of meditation-based interventions. On the measurement front, there have been signs of progress. A few MBI researchers have started to actively monitor AEs either through questionnaires or through clinician interviews (Kuyken et al., 2015; Kuyken et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2014). While these are typically limited to serious AEs (life-threatening or fatal events) or “deterioration” on pre-existing clinical outcomes that require clinical attention, such as increased depression or suicidality, this is a considerable improvement from passive monitoring.

In addition, a recent qualitative study of 60 Buddhist meditators and meditation teachers entitled “The Varieties of Contemplative Experience” (c.f. Rocha, 2014) also sought to improve knowledge of meditation-related experiences that are underreported, unexpected, “adverse”, or associated with significant levels of distress and functional impairment. While qualitative and retrospective, this study applied 11 of the 13 causality criteria (as outlined by the World Health Organization, Federal Drug Administration, and NIH; Agbabiaka et al., 2008; NIH, 2016; WHO, 2016), including interviews with meditation teachers (expert judgment). The study produced 60 categories of meditation-related experiences and 26 categories of “influencing factors” that may impact the duration, associated distress, and impairment of the experience. While the first study of its kind, it sets a foundation for testable hypotheses in future research. In addition, the 60 categories of meditation-related experiences are being converted into a measurement tool that can be used for systematic assessment across multiple studies and conditions. The codebook was inserted as an interview-based assessment into a recently-completed clinical dismantling trial of MBCT (NCT# 01831362) which can assess whether similar experiences occur in MBIs, as well as address the question of biological gradient (i.e., whether more exposure results in greater effects; Hill, 1965).

The large and growing body of empirical data on the psychological and neurobiological effects of meditation and related practices also represent a step forward to identifying potential mechanisms by which meditation-related effects, as well as AEs might occur. Knowledge of mechanism may help identify who is at risk. For example, there is some evidence that hyper-connectivity of the prefrontal cortex and limbic regions may result in affective and autonomic blunting which is characteristic of dissociation (Ketay et al., 2014; Sierra et al., 2002). Similarly, increased activity in the inferior parietal cortex, a common outcome of mindfulness training (Brefczynski-Lewis et al., 2007; Farb et al., 2007; Goldin, & Gross, 2010; Hasenkamp et al., 2012), might relate to depersonalization (disembodiment, loss of agency and self-other/self-world boundaries; Bunning, & Blanke, 2005). Others have created neurobiological models for specific meditation-related experiences, such as visual hallucinations, (Lindahl et al., 2014), sleep-related changes (insomnia; Britton et al., 2014), changes in sense of self (Dor-Ziderman et al., 2013) and altered perceptions of space and time (Berkovich-Ohana et al., 2013).

Research on adverse effects of treatments that share mechanisms with meditation should also be considered. For example, treatments that restrict environmental stimulation or narrative processing through internal sensory focus, such as Qigong (APA, 2000; Shan, 2000), autogenic training (Linden, 1990), and relaxation (Edinger, & Jacobsen, 1982), can precipitate similar AEs, such as autonomic hyperarousal, perceptual disturbances (Lindahl et al., 2014), traumatic memory re-experiencing (Brewin, 2015; Brewin et al., 2010; Miller, 1993), and psychosis (APA, 2000; Shan, 2000). Relaxation-induced panic or anxiety (RIP/RIA) is perhaps one of the most well documented phenomena with clear relevance to meditation (Adler et al., 1987; Cohen et al., 1985; Heide, & Borkovec, 1983).

III.D. Challenges for Investigating Mindfulness through Contemplative Neuroscience

As part of the burgeoning trend in research on mindfulness and meditation more generally (Figure 1), investigators have increasingly used methods from Cognitive Neuroscience (cf. Gazanniga & Mangun, 2014), especially functional magnetic-resonance imaging (fMRI). These methods yield visual depictions of participants' relative, regionally localized, brain activation during various types of cognitive task performance as well as the integrated functional neural networks of mental processing (including the default mode network; cf. Power et al. 2011). The investigation of mindfulness through such methods has also come to be known as Contemplative Neuroscience (e.g., Davidson & Lutz, 2008).

Limitations in depictions of brain activity based on neuroimaging

Representative pictures from fMRI and other neuroimaging methods do not clearly convey the complex – often fraught – chain of biological and computational steps that lead to inferences about changes in brain structure and function. They also neglect to highlight the fact that such inferences are frequently derived from averages obtained across groups of participants. Thus, when also accompanied by numerous other difficult experimental, statistical, and inferential challenges prevalent in psychological research, Contemplative Neuroscience has often led to overly simplistic interpretations of nuanced neurocognitive and affective phenomena. For example, psychologist Rick Hanson, in what is presumably an effort to explain how meditation has been shown to influence emotion regulation, correlated with alterations in amygdala activity (e.g., Goldin & Gross, 2010), has stated, “ In terms of amydgala activity, people seem to belong to one of three groups…the ones with a joyful amydgala – are more focused on promoting the good than on preventing the bad.” (Hanson, 2013, pp. 43-44). As a result of such oversimplifications, meditative benefits may be exaggerated and undue societal urgency to undertake mindfulness practices may be encouraged (e.g., Farias & Wikholm, 2015).

Problematic aspects of group-level neuroimaging analyses

Furthermore, results from neuroimaging during mindfulness practices and other types of meditation may be subject to unique confounds. Despite variability in different types of practice and meditative experiences, it is not uncommon for neuroimaging data obtained from diverse practitioners to be pooled in aggregated analyses (e.g., Luders et al., 2012; Luders, Kurth, Toga, Narr, & Gaser, 2013; Ferrarelli et al. 2013; Sperduti, Martinelli, & Piolino, 2012). Also complicating theoretical interpretation of their results and further adding to confounds associated with systematic individual differences, many neuroimaging studies have used cross-sectional designs, precluding possible inferences about underlying cause-and-effect relationships (cf. Tang et al., 2015).

Ancillary physical artifacts in neuroimaging data

Certain methodological confounds that plague neuroimaging studies in general, are of particular concern in studies of individuals who meditate. Physical artifacts involving head movements and cardio-respiratory effects are especially notable (Holmes, Solomon, Cappo, & Greenberg, 1983; Lutz, Greischar, Perlman, & Davidson, 2009; Reuter et al., 2015; Van Dijk, Sabuncu, & Buckner, 2012; Wallace, 1970; Wallace, Benson, & Wilson, 1971; cf. Lazar et al. 2000; Zeidan et al. 2011). If non-meditators are more restless or breathe more rapidly than experienced meditators during MRI sessions, there could be spurious group differences in some neuroimaging measurements (e.g., with respect to meditators, seemingly more brain gray-matter and brain activation in particular neuroanatomical regions; cf. Greene, Black, & Schlaggar, 2016). Systematic individual differences in cardio-respiratory activity between non-meditators and meditators are especially worrisome because of the so-called ‘vein-drain problem’ (Turner, 2002). It prevails especially in typical regions of differential brain activation. Enlarged blood vessels may lead to measurement artifacts (e.g., Boubela et al., 2015), which can be particularly pronounced in brain regions commonly identified as important for cognition and emotion (e.g., insular and anterior cingulate cortices).

Partially mitigating these concerns, meta-analyses of both structural and functional neuroimaging data have revealed differences in brain regions that tend to be consistent with the specific meditation practices under study (e.g., changes in brain regions associated with bodily awareness of mindfulness practitioners – for example, the insula and somatosensory cortices --and widespread recruitment of brain regions associated with vision during meditative visualization). Such findings, when supported by results from meta-analyses of multiple studies, are less likely to have stemmed merely from artifacts (Fox et al., 2014; Fox et al., 2016).

Practical vs. statistical significance of neuroimaging data

Statistical and theoretical approaches to calculating and interpreting effect sizes and associated confidence intervals have been well developed in behavioral and psychological research (Cumming, 2014). Yet calculating valid estimates of effect sizes in neuroimaging data is extremely difficult (Fox et al., 2014; Fox et al., 2016; Friston, 2012; Hupé, 2015). Consequently, the practical significance and clinical importance (e.g., diagnostic and/or therapeutic utility) of observed changes in brain structure and neural activity associated with practicing mindfulness is still elusive (cf. Castellanos, Di Martino, Craddock, Mehta, & Milham, 2013). Moreover, despite some agreement among investigators that mindfulness and other types of meditation affect the brain, we still do not know how their effects compare to other cognitive training methods in terms of practical significance.

Consensus about findings from Contemplative Neuroscience

Despite the many serious limitations mentioned previously, studies in Contemplative Neuroscience do allow some preliminary conclusions. Meta-analyses of neuroimaging data suggest modest changes in brain structure due to practicing mindfulness (Fox et al., 2014). Some concomitant modest changes also have been observed in neural function (e.g., Sperduti et al., 2012; Tomasino, Fregona, Skrap, & Fabbro, 2013; Fox et al., 2016; for a broad review, see Tang et al, 2015). Caution must exerted in interpreting these findings; similar changes have been observed following other forms of mental and physical skill acquisition, such as learning to play musical instruments and learning to reason, suggesting that they may not be unique to mindfulness or other popular types of meditation practice (cf. Draganski & May, 2008; Hyde et al., 2009; Mackey, Singley, & Bunge, 2013; Münte, Altenmüller, & Jäncke, 2002).

Prescriptive research agenda: Truth in advertising by Contemplative Neuroscience

Rather than contributing to further media hype, researchers in Contemplative Neuroscience must endeavor to communicate more accurately with other scientists, journalists, and the public about not only the potential benefits of mindfulness practices for mental processes and brain mechanisms, but also about the serious limitations of neuroimaging methods and data collected through them. We encourage contemplative neuroscientists to follow best practices in neuroimaging methods generally (cf. Nichols et al. 2017), but also to consider and accommodate unique issues that may arise while collecting brain data from meditating populations. These unique issues (e.g., different respiration rates, different cardiac activity, dramatically different demographic and life-style characteristics) may warrant unique data collection methods (e.g., cardiac-gated image acquisition) and/or analytic methods (e.g., removal of activity due to respiratory artifact), as well as very detailed demographic information. Particular attention should be paid to methodologically and/or statistically controlling potential contributions from a panoply of confounded variables (e.g., participant motivation, placebo effects, cardio-respiratory factors, head motion, history of psychopathology) that may underlie apparent group differences. This will be especially necessary where mindfulness studies compare results from long-term practitioners versus meditation-naïve participants. In contexts of comparing meditation experience, either between-groups, or within, some common metric should be used (cf. Hasenkamp & Barsalou, 2012). Researchers should stress specifically that individuals who already have meditated over many years, or who – though not yet experts – are personally attracted to meditation, may have characteristics that differentiate them from the general population even before experimentation (Mascaro, Rilling, Negi, & Raison, 2013). Prominent mention about the limitations and fraught nuances of statistical neuroimaging analyses should not be entirely neglected either. No amount of sophisticated statistical prowess can correct results from faulty or confounded methods: a fact to which researchers, scientists, and the public should regularly be reminded.

And, ultimately, the popular news media – inspired by honest, forthright, thorough cooperation with contemplative neuroscientists – must persuade the general public together with government funding agencies that multiple large, longitudinal, randomized-control trials (RCTs) that consider participant preferences concerning mindfulness practices are required, and should be funded. We need such trials in order to definitively determine the full benefits and costs of practicing mindfulness. Without future RCTs, prevalent widespread uncertainties surrounding past results from haphazard studies of mindfulness involving relatively small sample sizes (e.g., Button et al., 2013) and considerable variation in how neuroimaging methodologies have been implemented (Simmons et al., 2011) make it difficult to know the neural effects of mindfulness.

IV. Conclusion

Contemplative psychological scientists and neuroscientists, along with other researchers who study mental processes and brain mechanisms underlying the practice of mindfulness and related types of meditation, have a considerable amount of work to make meaningful progress. Much work should go toward improving the rigor of methods used, along with the accuracy of news-media publicity and eliminating public misunderstandings caused by past undue ‘Mindfulness Hype’. These efforts have to take place on several related fronts.

First, as mentioned before, the various possible meanings of ‘mindfulness’ have to be clarified. To deal with prevailing inherent semantic ambiguities, researchers should adopt more nuanced, precisely focused, terminology for referring to the various distinct mental and physical states as well as overt behaviors often associated with mentions of ‘mindfulness’ (see Table 2). In so far as future research involves self-report questionnaires about mindfulness, new ones that incorporate specific terminology (see e.g., Table 2) ought to be developed. Theoretical models formulated to account for data need also consider these new key terms.

Second, future studies of mindfulness should conform to lessons being learned from the ongoing ‘replication crisis’ in Psychological Science and other related scientific disciplines. For example, Pre-registered experiments and Open-Science replications of mindfulness are desirable. Additional discipline is especially needed in light of recent growing troublesome meta-analytic evidence that -- like some other ‘glitzy’ popular topics of psychological and neural investigations -- past mindfulness research has succumbed to these questionable practices (Coronado-Montoya et al., 2016).

Third, future clinical applications involving mindfulness-based interventions must seek to attain more uniformity and better control (see Table 3), especially where definitive answers have yet to be found. It is critical that those who conduct clinical research provide warnings regarding the extent to which their research findings generalize to clinical practice. Also, researchers and clinicians have to be put on guard, educated about, and encouraged to address the potential adverse effects stemming from mindfulness practices. Research on the nature and scope of potential adverse effects should receive considerable further attention and government funding, due to the public's rapidly increasing involvement in practicing mindfulness.

Fourth, as they continue to emerge through technological advances in neuroimaging methods, new findings from Contemplative Neuroscience about the mental processes and brain mechanisms of mindfulness practices must be reported with all due modesty. Their importation into protocols for future clinical practice must await proper vetting of the potential practical significance that may accompany them. This vetting process will have to deal diligently with the many aforementioned challenges that still remain to be surmounted by the Contemplative Neuroscience community.

Only with such diligent multi-pronged future endeavors may we hope to surmount the prior misunderstandings and past harms caused by pervasive Mindfulness Hype that has accompanied the Contemplative Science movement.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this article to our dear friend and colleague, Cathy Kerr, who passed away unexpectedly during revision of this work. Cathy was among the key driving forces that led to this particular group forming and to our formal meeting in Amherst, MA in July, 2014. Cathy touched so many lives and had a profound influence on the variety of ways that many of us approach mindfulness and meditation research. She will be profoundly missed.