Abstract

Background:

The larval stages of Gasterophilus are obligate parasites in the gastrointestinal tract of equine accountable for pathologic ulcers in the Persian onager gastrointestinal. The aim of the current report was to study the histopathological change with G. pecorum larvae in the esophagus of a Persian onager.

Methods:

This study was performed in Iranian Zebra propagation and breeding site in Khartouran National Park, southeast of Shahrud City, Semnan Province, Iran in 2014. Following a necropsy with specific refer to esophagus of one adult female Persian onager were transmitted to the laboratory. After autopsy, parasites collected from the esophagus were transmitted into 70% alcohol. For histopathological investigation, tissue samples were collected from the esophagus. The tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and conformity routine processing, there were stained with Hematoxylin and eosin.

Results:

After clarity by lactophenol parasites were identified as G. pecorum. Microscopic recognition contained hyperemia, inflammatory cell infiltration, epithelial destruction, esophageal gland hyperplasia.

Conclusion:

This is the first survey of G. pecorum and histopathological study in the Persian onager esophagus in the world.

Keywords: Persian onager, Gasterophilus pecorum, Epithelial destruction

Introduction

The Persian onager (Equus hemionus onager), a wild donkey endemic to Iran, is classified as critically endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List. The Asian wild donkeys were confined in successive periods but ecology of the two residual crowds, determined in preserved region in Touran National Park and Bahram-e-Goor Reserve (1).

The genus Gasterophilus (Diptera: Oestridae) contains nine species. Equids are hosts to the larvae of the Gasterophilus type causing gastrointestinal myiasis. Gasterophilus is specified by dysphasia, gastrointestinal ulcer ations, intestinal obstruction or volvulus, rectal prolapses, anemia, diarrhea and digestive disturbances.

The adult flies are not parasitic and are large, 11–15mm in length. Adult Gasterophilus spp. flies lay their eggs to host hairs. G. pecorum is an exception as females lay their eggs in brown-haired person, leaves, and stalks of plants (2, 3).

After hatching, the larvae tunnels into the tissue of the host, larvae at the first stage attain the oral cavity of equine passively (G. intestinalis, G. pecorum) or actively, the first stage larvae hatch and moult to L2, which can be available in various regions of the gastrointestinal tract, and in L3 remains dependent to the mucosa for 8–10 months (4, 5).

Gasterophilus pecorum, G. inermis, and G. haemorrhoidalis are just reported in finite regions of Europe and Eastern Countries (6).

The damage the bot fly reasons happens after the larvae arrive the animal’s mouth and gastrointestinal tract. When the first instar larvae tunnel into the mouth, the horse may experience intense inflammation, as well as the expansion of pus pockets and loosened teeth. Loss of appetite may develop due to the larva’s resident. As the second and third instar larvae reside the gastrointestinal tract and bind to the stomach and intestine, variable complications can occur. Severe infestation of these larvae can cause anemia, esophageal paralysis, ulcerated stomach, chronic gastritis, stomach rupture and squamous cell tumors (7).

Esophageal disorders, exception obstruction is not common to observe in equine. Little is known about the parasite spectrum of this species. Accordingly, there was severity of the infection in this area of robot flies.

The aim of the current report was to study the histopathological change with G. pecorum larvae in the esophagus of a Persian onager.

Materials and Methods

This study was performed in Iranian Zebra propagation and breeding site in Khartouran National Park, southeast of Shahrud City, Semnan Province, Iran (latitude 36.736536, longitude 55.700684) in 2014, with a temperate climate. A cervical vertebral fracture after collision with a fence was diagnosed as cause of death of the 20-yr-old female Persian onager. Probably it escaped from something and did not see a fence and subsequently broken neck lead to death.

Following a field, necropsy gastrointestinal system was attentively removed and transferred directly to the Laboratory of Veterinary Diagnostic Medicine of the Islamic Azad University-Babol Branch for histopathologic and parasitological examination.

The esophagus was assayed for parasite infections. The large changes were recorded, and myiasis was collected and transferred into 70% alcohol (Jahan Alcohol Teb Co., Arak 454546, Iran). The parasites were detected as G. pecorum by light microscope with referral to key Zumpt keys (8) using stereo microscopes with 10X to 40X magnification. Tissue samples and myiasis were used for histopathological examinations fix the tissue immediately in 10% buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded and sections were cut using a rotary microtome (Leitz, 1512, Germany) at 5μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E).

The study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Babol Branch, Babol, Iran.

Results

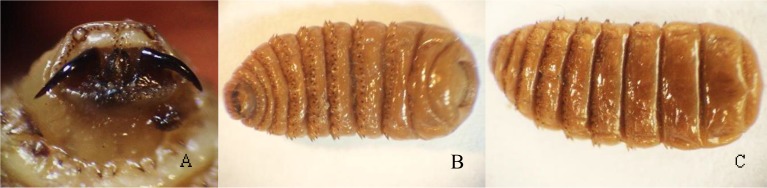

Esophageal necropsy revealed that the onager was infected to myiasis. Totally, 87 third larval stage of G. pecorum were removed from esophageal tissue of the animal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Third larval stage of Gasrophilus pecorum A. Ventral view of pseudocephalon B. ventral view C. dorsal view

The third larval stage of G. pecorum was the arrangement of denticles on the pseudocephalon into 3 groups, 2 lying laterally and a third centrally in front of the mouth hooks (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Gasterphilus larvae on the esophageal mucosal membrane of an onager

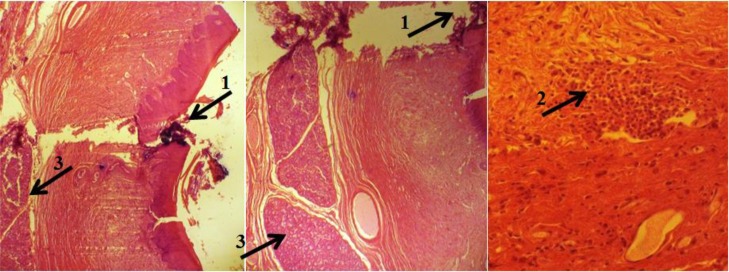

We found gastric myiasis caused by G. pecorum (365 larvae). The histopathological study revealed different part of myiasis (Fig. 3). Microscopic examination showed epithelial destruction, esophageal gland hyperplasia, hyperemia, lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration in mucosa and submucosa of esophagus of the Equus hemionus infected by Gasterophilus (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Cross-sections Gasterphilus larvae (10×), H and E

Fig. 4.

Cross sections of intraluminal myiasis, Inflammatory cell infiltration (1), epithelial destruction (2), Esophageal gland hyperplasia (3). H and E. ×40

Discussion

Botfly infestation has been reported in different countries can cause economic losses in domestic animals. The presence of Gasterophilus species has been much studied in Asia extensively as the most pathogenic Gasterophilus species on horses.

Accomplished investigations in different parts of the world, incidence ranged from 11% to 100% including 11.1% in Israel (9), 12.3% in Sweden (10), 43% in Ireland (11), 34% in France (12), 53% in England and Wales (13), 58% in Belgium (14), 82.2% in Italy (6), 65% in Switzerland (15), 98.7% in Kentucky, USA (16) and 100% in Morocco (17, 18).

Bots in the alimentary tract were identified as third stage larvae associated with ulcers include G. pecorum, G. nigricornis and G. nasalis (19). Gasterophilus pecorum has been studied in Asia where it is regarded as the most pathogenic Gasterophilus species on horses (8).

A study in China was done on the diagnosis of the larval Gasterophilus species in 90 equines, from 2008 to 2013 revealed the all-90 (100%) equines were infested via larval Gasterophilus, and 3723 secondary instar larvae (L2) as well as 63778 third instar larvae (L3). Six types of Gasterophilus were recognized include G. pecorum 88.94%, G. nigricornis 4.94%, G. nasalis 3.93%, G. haemorrhoidalis 1.91%, G. intestinalis 0.19%, and G. inermis 0.087% (20). In Iran, the onager was infected by myiasis (G. pecorum) and nematode (Habronema muscae) (21).

According to our results, G. pecorum is more adaptable to the local environment in Khartouran National Park. The association with this unique comportment and the desert steppe ecosystem can help describe the situation.

Water availability limits the activity area of wild animals in a region such as Khartouran National Park, which has high evaporation, limited surface runoff, and low precipitation. A study in Kalamaili showed that the oviposition sites of G. pecorum were often near a water source (3). Frequent drinking at water sources may increase the risk of G. pecorum infection. Thus, the equids in arid desert grasslands have a higher intensity of Gasterophilus spp.

Conclusion

This is the first report of this parasite and histopathological study in the Persian onager esophagus in the world.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely want to thank the people contributed for the completion of this research project, especially thanks to Ms Eslami, because of her helps in laboratory experiments. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Tatin L, Darreh-Shoori BF, Tourenq C, Tatin D, Azmayesh B. (2003) The last populations of the Critically Endangered onager Equus hemionus onager in Iran: urgent requirements for protection and study. Oryx. 37( 4): 488– 491. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gökçen A, Sevgili M, Altaş MG, Camkerten İ. (2008) Presence of Gasterophilus species in Arabian horses in Sanliurfa region. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 32: 337– 339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu SH, Hu DF, Li K. (2015) Oviposition site selection by Gasterophilus pecorum (Diptera: Gasterophilidae) in its habitat in Kalamaili Nature Reserve, Xinjiang, China. Parasite. 22: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Studzińska MB, Wojcieszak K. (2009) Gasterophilus sp. botfly larvae in horses from the south-eastern part of Poland. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 53: 651– 655. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ganjali M, Keighobadi M. (2016) A Rare Case of Gastric Myiasis in a Lion Caused by Gasterophilus intestinalis (Diptera: Gasterophilidae)-Case Report. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 10( 3): 421– 3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Otranto D, Milillo P, Capelli G, Colwell DD. (2005) Species composition of Gasterophilus spp. (Diptera, Oestridae) causing equine gastric myiasis in southern Italy: parasite biodiversity and risks for extinction. Vet Parasitol. 133( 1): 111– 118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mashayekhi M, Ashtari B. (2013) Study of Gasterophillus role in equine gastric ulcer syndrome in Tabriz area. Bull Env Pharmacol Life Sci. 2( 12): 169– 172. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zumpt F. (1965) Myiasis in man and animals in the Old World. A textbook for physicians, veterinarians and zoologists, Butterworths, London. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sharir B, Pipano E, Markovics A, Danieli Y. (1987) Field studies on gastrointestinal infestation in Israeli Horses. Isr J Vet Med. 43: 223– 227. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoglund J, Ljungstrom BL, Nilsson O, Lundguist H, Osterman E, Uggla A. (1997) Occurrence of Gasterophilus intestinalis and some parasitic nematodes of horses in Sweden. Acta Vet Scand. 38: 157– 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sweeney HJ. (1990) The prevalence and pathogenicity of Gasterophilus intestinalis larvae in horses in Ireland. Irish Vet J. 43: 67– 73. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bernard N, Collobert C, Tariel G, Lamidey C. (1994) Epidemiological survey of bot infection in horses at necropsy in Normandy from April 1990 to March 1992. Rec Med Vet. 170: 231– 235. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Edwards GT. (1982) The prevalence of Gasterophilus intestinalis in horses in northern England and Wales. Vet Parasitol, 11: 215– 222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Agneessens J, Engelen S, Debever P, Vercruysse J. (1998) Gasterophilus intestinalis infections in horses in Belgium. Vet Parasitol. 77: 199– 204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brocard P, Pfister K. (1991) The epidemiology of gasterophilosis of horses in Switzerland. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 133: 409– 416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Drudge JH, Lyons ET, Wyant ZN, Tolliver SC. (1975) Occurrence of second and third instars of Gasterophilus intestinalis and Gasterophilus nasalis in stomachs of horses in Kentucky. Am J Vet Res. 36: 1585– 1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pandey VS, Ouhelli H, Elkhalfane A. (1980) Observations on the epizootiology of Gasterophilus intestinalis and G. nasalis in horse in Morocco. Vet Parasitol. 7: 347– 356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tavassoli M, Bakht M. (2012) Gastrophilus spp. myiasis in Iranian equine. Sci Parasitol. 13( 2): 83– 86. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu SH, Hu DF. (2016b) Parasites observed in the proximal alimentary tract of a Przewalski's horse in China. Equine Vet Educ. 30: 20– 23. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu SH, Li K, Hu DF. (2016b) The incidence and species composition of Gasterophilus (Diptera, Gasterophilidae) causing equine myiasis in northern Xinjiang, China. Vet Parasitol. 217: 36– 38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zaheri BA, Ronaghi H, Youssefi MR, Hoseini SM, Omidzahir S, Dozouri R, Eshkevari SR, Mousapour A. (2015) Gasterophilus pecorum and Habronema muscae in Persian onager (Equus hemionus onager), histopathology and parasitology survey. Comp Clin Path. 24( 5): 1009– 1013. [Google Scholar]