Abstract

Purpose

Trichloroethylene (TCE) is an industrial solvent associated with liver cancer, kidney cancer, and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). It is unclear whether an excess of TCE-associated cancers have occurred surrounding the Middlefield–Ellis–Whisman Superfund site in Mountain View, California. We conducted a population- based cancer cluster investigation comparing the incidence of NHL, liver, and kidney cancers in the neighborhood of interest to the incidence among residents in the surrounding four-county region.

Methods

Case counts and address information were obtained using routinely collected data from the Greater Bay Area Cancer Registry, part of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program. Population denominators were obtained from the 1990, 2000, and 2010 US censuses. Standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) with two- sided 99 % confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for time intervals surrounding the US Censuses.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences between the neighborhood of interest and the larger region for cancers of the liver or kidney. A statistically significant elevation was observed for NHL during one of the three time periods evaluated (1996–2005: SIR = 1.8, 99 % CI 1.1–2.8). No statistically significant NHL elevation existed in the earlier 1988–1995 (SIR = 1.3, 99 % CI 0.5–2.6) or later 2006–2011 (SIR = 1.3, 99 % CI 0.6–2.4) periods.

Conclusion

There is no evidence of an increased incidence of liver or kidney cancer, and there is a lack of evidence of a consistent, sustained, or more recent elevation in NHL occurrence in this neighborhood. This evaluation included existing cancer registry data, which cannot speak to specific exposures incurred by past or current residents of this neighborhood.

Keywords: Cancer cluster, Superfund, Trichloroethylene, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Kidney, Liver

Purpose

The association between trichloroethylene (TCE) and cancer risk has recently received increased attention [1–5], in part due to 2011 results from the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) that provided evidence for associations between TCE exposure and kidney, liver, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) cancers [6, 7]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer subsequently re-classified TCE as “carcinogenic to humans” [8]. TCE is a manufactured chlorinated solvent used until the 1990s as an industrial solvent within manufacturing and industrial facilities for a variety of purposes [4, 9]. US EPA Superfund sites have been defined as areas where large volumes of TCE have been released [10]. The Middlefield–Ellis–Whisman (MEW) Superfund Study Area (or MEW Site) in Mountain View, California, has been the subject of environmental investigation and remediation since the 1980s, due to contamination related to industrial, manufacturing, and military operations of responsible parties described in detail elsewhere. (Note: the MEW Site is comprised of several Superfund sites: Fair- child Semiconductor Corp.—Mountain View Superfund site, Raytheon Company Superfund site, Intel Corp.— Mountain View Superfund site, several other facilities, and portions of the former Naval Air Station Moffett Field Superfund site) [11].

The Greater Bay Area Cancer Registry (GBACR)—a population-based cancer registry comprising the nine county region around the San Francisco Bay Area—received a call from a media representative regarding a possible increase in cancer incidence due to TCE exposure in the residential area of Mountain View closest to the MEW site’s vapor intrusion pathways. Population-based cancer registries in the USA do not collect data on exposures or environmental risk factors. However, cancer registries routinely collect information on residential address at the time of diagnosis for cancer patients, which enables cancer registries to perform residential cancer cluster investigations. In California, cancer concern investigations are handled at the regional level with oversight provided by the California Cancer Registry (CCR), a program of the California Department of Public Health and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program [12]. Population-based cancer reporting in the Greater Bay Area began in 1973 as a part of the SEER program. In 1988, cancer reporting became mandatory throughout California, and the CCR was established. In follow-up to the inquiry from a representative of the local media, we conducted a cancer cluster investigation that followed registry guidelines [13]. Our investigation focused on cancer sites suggested in the literature to be associated with TCE exposure: NHL, and invasive cancers of the liver and kidney [6–8].

Methods

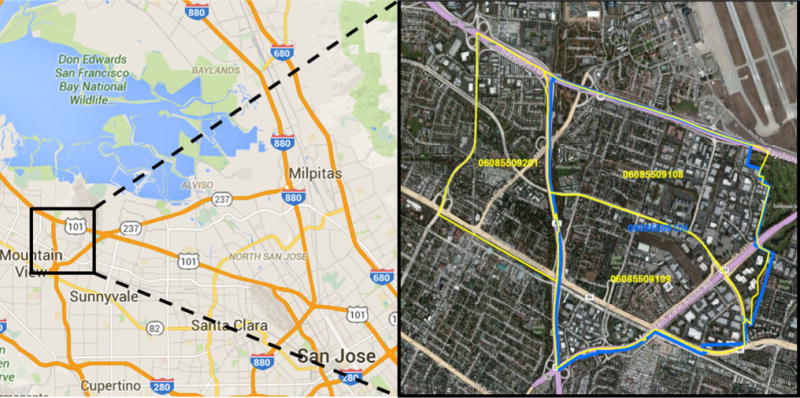

Routinely collected cancer registry data—including address at diagnosis—were used to determine the number of cases diagnosed among residents in the GBACR catchment area (Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Monterey, San Benito, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Santa Cruz). Coding definitions for cases and populations are provided in Table 1. The area of concern was identified as the residential neighborhood in the MEW study area near Moffett Naval Air Station, an area bordered by Whisman Road, Middlefield Road, Ellis Street, and Highway 101 (Fig. 1). As understanding of cancer occurrence requires accurate counts of both the number of cancer cases (e.g., numerators) and the numbers of persons living in a region (e.g., denominators), our ability to assess cancer occurrence in areas smaller than counties depends on the availability of accurate population counts defined by census tracts. These detailed population counts are only collected as part of the US Census every 10 years. The present report uses small area-level population data from the 1990, 2000, and 2010 US censuses. We examined cancer occurrence during three time intervals: 1988–1995 (8 years around 1990 US Census); 1996–2005 (10 years around 2000 US Census); and 2006–2011 (6 years around 2010 US Census).

Table 1.

Case and neighborhood definitions, ICD-O-3 and US census tract codes

| Cancer | ICD-O-3 site codes | ICD-O-3 morphology codes | US census tract codesa

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2000, 2010 | |||

| NHL | All | 9590–9597, 9670–9671, 9673, 9675, 9678–9680, 9684, 9687–9691, 9695, 9698–9702, 9705, 9708–9709, 9712, 9714–9719, 9724–9729, 9735, 9737–9738, 9811–9818, 9823, 9827, 9837 | ||

| Liver | C22.0, C22.1, C23.9, C24.0–24.9 | All, excluding 9050–9055 and 9590–9992 | 5,091.04, 5,092.01 | 5,091.08, 5,091.09, 5,092.01 |

| Kidney | C64.9, C65.9 | All, excluding 9050–9055 and 9590–9992 | ||

For expected case counts we: [A] used the peri-censal years and the corresponding census population for the referent region of interest to obtain expected 5-year cancer counts for the period around the 1990 and 2000 US Censuses and expected 4-year cancer counts for the period around the 2010 US Census, as 2012 were not yet available (e.g., 1988–1992, 1990 Census population; 1998–2002, 2000 Census population; 2008–2011, 2010 Census population); [B] divided by the number of peri-censal years to get an expected annual rate for the referent region (e.g., divided by 5, divided by 5, divided by 4); and [C] multiplied this expected annual rate for the referent region by the number of years to which these rates were applied (e.g., multiplied by 5, multiplied by 10, multiplied by 6)

Fig. 1.

Residential neighborhood of interest, bounded by yellow and blue. US Census County 0608. 2000 and 2010 US Census Tracts 5,091.08, 5,091.09, and 5,092.01; and 1990 US Census Tracts 5,091.04 and 5,092.01. Images adapted from google.com/maps

To determine whether cancer occurrence has been unusual, we compared the number of observed cancer cases that occurred among residents of the neighborhood to the number that would be expected to occur if residents had the same pattern of cancer occurrence as the entire four-county Santa Clara Region. These average annual age-, sex-, and race-specific incidence rates were applied to the number of residents in the neighborhood of interest according to the census population estimates to generate expected case counts. The observed and expected numbers were compared directly using the standardized incidence ratio (SIR). Due to statistical limitations of using small area-level data, a two-sided 99 % confidence interval (CI) was used to minimize the false positive error. If the 99 % CI for the SIR included 1.0, then any difference between observed and expected numbers were not considered to be statistically significant and may have been due to chance sampling fluctuation at the small area level.

Results

The population within the neighborhood of interest increased by about 13 % from 1990 to 2010. Census data indicated that residents in the neighborhood of interest had an older age distribution in 2010 compared to 1990. Table 2 shows the estimate of NHL, liver cancer, and kidney cancer cases observed and expected. The observed versus expected occurrence of cancers of the liver and kidney were not significantly higher in the neighborhood for any time period examined. Further analysis revealed no significant elevations in liver and kidney cancer among children under age 15 years living in the neighborhood of interest (data not shown). From 1996 to 2005, 31 cases of NHL were observed and 17.1 were expected, a statistically significant elevation in incidence (SIR = 1.8, 99 % CI 1.1–2.8). From 2006 to 2011, 17 cases of NHL were observed and 12.8 were expected, a nonsignificant elevation in incidence (SIR = 1.3, 99 % CI 0.6–2.4) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence of cancer in Mountain View CA neighborhooda, 1988–1995, 1996–2005, and 2006–2011

| 1988–1995

|

1996–2005

|

2006–2011b

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expectedc | SIRd | 99 % CIe | Observed | Expectedc | SIRd | 99 % CIe | Observed | Expecteda | SIRc | 99 % CIe | |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 12 | 9.3 | 1.3 | (0.5–2.6) | 31 | 17.1 | 1.8 | (1.1–2.8) | 17 | 12.8 | 1.3 | (0.6–2.4) |

| Kidney cancerf | 5 | 4.2 | 1.2 | (0.3–3.4) | 10 | 7.7 | 1.3 | (0.5–2.8) | 8 | 8.7 | 0.9 | (0.3–2.1) |

| Liver cancerf | <5 | <5 | 0.8 | (0.1–2.8) | 8 | 8.8 | 0.9 | (0.3–2.1) | 5 | 8.6 | 0.6 | (0.1–1.6) |

1988–1995: Census Tracts 5,092.01 and 5,091.04 (1990 US Census); 1996–2005 Census Tracts: 5,092.01, 5,091.08 and 5,091.09 (2000 US Census); 2006–2011 Census Tracts: 5,092.01, 5,091.08 and 5,091.09 (2010 US Census)

Data for 2011 diagnoses are approximately 98 % complete, with about 3 % of cases not yet geocoded to a residential census tract

Expected rates were obtained from the Santa Clara region (Monterey, San Benito, Santa Clara and Santa Cruz counties)

SIR = standardized incidence ratio = observed number of cases/expected number of cases. The exact value of the number of expected cases is used in computing the SIR

If the 99 % confidence interval (CI) for the SIR contains 1, then any difference between the observed and expected number is not statistically significant

Kidney cancer includes cancers of the kidney and renal pelvis; liver cancer includes cancers of the liver, gallbladder, intrahepatic, and extrahepatic bile ducts

Further analysis revealed that 60 cases of NHL were diagnosed in the neighborhood of interest from 1988 to 2011, but case counts fluctuated from year to year and seemed to be clustered around selected years, 1998–2001 and 2008–2009, while case counts were relatively lower in the other years. Caution should be taken when comparing the crude case counts over time, since: (1) Generally, we expect the numbers of cases to increase over time simply due to growth in the population in these tracts; (2) 1990, 2000, and 2010 census population estimates indicate that this neighborhood is an aging population, and increased age increases the expected rate of NHL. Of the 60 cases, 22 of these occurred from 1998 to 2002; thus, the numbers of cases in the years prior to 1998 and following 2002 suggested that numbers were lower than the 1998–2002 period. No cases of NHL were diagnosed in the neighborhood of interest for the calendar years 1989, 1995, 1997, and 2007. The increased rate of NHL was not driven by one of the census tracts. There were no significant elevations in NHL among children under age 15 years living in the neighborhood of interest. Case counts were comparable across sexes (n = 31 male; n = 29 female).

Discussion

Cancer cluster investigations in the USA are controversial [14–18]. They garner public attention and involve an investment of public funds. Cancer cluster investigations are primarily geared toward educating the community and/or representatives of the media about risk factors for cancer, statistical limitations of studying a small population of individuals using cancer registry data, and mitigating perceived risks from potential exposures to toxic chemicals in communities [14, 16, 18]. Research investigating media records of suspected cancer cluster reports demonstrates the environmental complexities associated with cancer cluster epidemiology as well as the breadth of popular concern regarding a variety of issues including exposure types, pollution sites, and specific environmental chemicals [16]. It remains unclear whether efforts to identify community cancer clusters have been successful. In a recent systematic review of 428 cancer cluster investigations evaluating 567 cancers of concern over the past two decades, Goodman et al. [14] identified an increase in incidence for 72 (13 %) cancer categories; only three were linked to hypothesized exposures.

The present cancer cluster investigation was performed using the population-based GBACR in follow up to a media representative’s inquiry regarding TCE exposure in a residential neighborhood nearby the MEW site in Mountain View, California. These data are obtained from physicians, hospitals, and other cancer treatment facilities, as mandated by state law for the reporting of all cancer cases to the registry [19]. Our assessment compared observed rates of liver, kidney, and NHL cancers—cancer sites associated with TCE exposure [6, 7]—in a residential neighborhood defined by US census tracts closest to the vapor intrusion pathways around the MEW site (12), to expected rates in the surrounding Santa Clara Region. We did not find an increased occurrence of liver or kidney cancers. A statistically significant increase in NHL was detected during one time period assessed, 1996–2005, but not before (1988–1995) or after (2006–2011). Thus, there is a lack of evidence of a consistent, sustained, or current elevation in NHL occurrence in this neighborhood.

To date, research investigating TCE exposure and cancer risk has focused primarily on occupational exposures [1, 4, 20–35]. To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study to investigate a potential association between residence near a source of TCE exposure and cancer risk. There is substantial toxicological evidence that exposure to TCE is associated with adverse health effects [7]. The modes of action of TCE in the carcinogenic process have been difficult to determine and controversial, in part due to complexities involving uncertainty related to TCE metabolites and pathways, exploring what effect co-exposures may play in modifying TCE toxicity, and setting appropriate risk thresholds [3, 5, 10, 36, 37]. To mitigate the potential adverse health effects among residents nearby the MEW site due to TCE contamination, the US EPA has continued to oversee site cleanup and monitoring [11]. Additionally, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Superfund Research Program (SRP) has a 25-year history in developing and providing scientific solutions to health problems associated with Superfund sites [38].

Limitations

There are several limitations related to using cancer registry data for carrying out residential cancer cluster investigations. Cancer registries do not collect data on exposures. Additionally, registry data are limited to address at the time of diagnosis and do not contain information on residential history or duration of residence. Since the development of cancer is a multi-step process often with a long time between the initiation of the carcinogenic process and a clinically diagnosable cancer [39], some former MEW neighborhood residents will have been diagnosed with cancer after moving out of the area, and some residents will have been diagnosed shortly after moving into the area. Because the timeframe between exposure to a carcinogen and onset of disease can be years, even decades, it is not possible to link the elevated incidence rate in a given time period to a specific cause or putative exposure with these data. Further, since we are only able to define neighborhoods using census tract definitions, it is possible that boundaries of the three selected census tracts do not accurately capture the intended neighborhood, or exposure. However, if there were a major increase in cancer among residents who have lived in the MEW neighborhood for a long period of time, it may be seen in this type of investigation.

Another limitation of cancer registry data is that risk factor data are not routinely collected. Hence, it is not possible to adjust for environmental, occupational, and lifestyle factors that may independently impact cancer risk or may act as potential confounders for residents within the neighborhood of interest. Any observed patterns may therefore be due to demographic and/or risk factor contributions other than environmental contaminants [40].

Another potential limitation in our study was our inability to carry out detailed analyses of cancer subtypes due to statistical power considerations related to small numbers. NHL includes a wide range of related blood cancers that vary with respect to pathological, clinical, and epidemiological features, with differing characteristics and etiology [41, 42]. Further research may be necessary to determine whether TCE exposure may be differentially associated with risk of specific NHL subtypes.

It is also important to note that although the SIR for NHL was significantly increased for one of the three time periods examined, it was based on small numbers and any difference may be due to random fluctuations rather than a true excess of NHL. Rates of these relatively rare cancers are generally unstable in such a small population and the number of cancer cases in an area, like any other event, may be high simply by chance. For example, there are 7,000 census tracts in California; even using a 99 % confidence level, at any given time 30 census tracts would have an apparent statistically significant increase in a particular type of cancer, even without any differences in the cancer risk [13].

Summary

Using existing population-based cancer registry data, the GBACR conducted an investigation of cancer incidence in a residential area possibly exposed to TCE from a nearby Superfund site. An excess occurrence of NHL was observed during one time period examined. However, there was a lack of evidence for an excess of liver or kidney cancer occurrence for any of the time periods examined, and a lack of evidence for an excess of NHL during the most recent or distant time periods. The present report cannot speak to specific exposures incurred by residents of this neighborhood, nor the effectiveness of ongoing cleanup efforts occurring in and around the neighborhood of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daphne Lichtensztajn for support with data analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California (CPIC). The collection of cancer incidence data was supported by the California Department of Health Services as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the NCI SEER program under contracts HHSN261201000140C awarded to CPIC, HHSN261201000035C to the University of Southern California, and HHSN261201000034C to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement 1U58 DP000807-01 awarded to the Public Health Institute.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Hansen J, Sallmén M, Seldén AI, Anttila A, Pukkala E, Andersson K, Bryngelsson I-L, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Olsen JH, McLaughlin JK. Risk of cancer among workers exposed to trichloroethylene: analysis of three nordic cohort studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(12):869–877. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purdue MP. TCE exposure linked to increase risk of some cancers trichloroethylene and cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(12):1. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt160.10.1093/jnci/djt131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guha N, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Lauby-Secretan B, Ghissassi FE, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Baan R, Mattock H, Straif K. Carcinogenicity of trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene, some other chlorinated solvents, and their metabolites. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(12):1192–1193. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karami S, Lan Q, Rothman N, Stewart PA, Lee K-M, Vermeulen R, Moore LE. Occupational trichloroethylene exposure and kidney cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69(12):858–867. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-100932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wartenberg D, Gilbert KM. Trichloroethylene and cancer. In: Gilbert KM, Blossom S, editors. Trichloroethylene: toxicity and health risks. Springer; London: 2014. pp. 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott CS, Jinot J. Trichloroethylene and cancer: systematic and quantitative review of epidemiologic evidence for identifying hazards. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(11):4238–4271. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8114238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) Toxicological review of tricholoroethylene chapter 6 (CAS No. 79-01-06) In support of Summary Information on the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) 2011 EPA/635/R-09/011F, September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans: trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene, and some chlorinated compounds. Vol. 106. World Health Organization; Lyon: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakke B, Stewart PA, Waters MA. Uses of and exposure to trichloroethylene in U.S. industry: a systematic literature review. J Occup Environ Hygiene. 2007;4(5):375–390. doi: 10.1080/15459620701301763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiu WA, Caldwell JC, Keshava N, Scott CS. Key scientific issues in the health risk assessment of trichloroethylene. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(9):1445–1449. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United States Environmental Protection Agency. Middlefield-Ellis-Whisman (MEW) Study area. http://yosemite.epa.gov/r9/sfund/r9sfdocw.nsf/ce6c60ee7382a473882571af007af70d/e4b75798264cff7988257007005e946e!OpenDocument#descr. Accessed 15 Sept 2013.

- 12.California Cancer Registry. Community cancer concerns. 2009 http://www.ccrcal.org/Public_Patient_Info/Public_Patient_Info.shtml#neighborhooddignosedwithcancer. Accessed 12 Aug 2014.

- 13.California Cancer Registry. Guidelines to address citizen concerns about cancers in their communities 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman M, Naiman J, Goodman D, LaKind J. Cancer clusters in the USA: what do the last twenty years of state and federal investigations tell us? Crit Rev Toxicol. 2012;42(6):474–490. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2012.675315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Condon S, Sullivan J, Netreba B. Cancer clusters in the USA: what do the last twenty years of state and federal investigations tell us? Crit Rev Toxicol. 2013;43(1):73–74. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2012.743504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kingsley BS, Schmeichel KL, Rubin CH. An update on cancer cluster activities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(1):165–171. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodman M, Naiman J, Goodman D, LaKind J. Response to Condon et al. comments on “Cancer clusters in the USA: What do the last twenty years of state and federal investigations tell us?”. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2013;43(1):75–76. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2012.743505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novak K. IBM accused of ignoring employee ‘cancer cluster’. Nat Med. 2003;9(12):1443. doi: 10.1038/nm1203-1443a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLaughlin RH, Clarke CA, Crawley LM, Glaser SL. Are cancer registries unconstitutional? Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(9):1295– 1300. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander DD, Kelsh MA, Mink PJ, Mandel JH, Basu R, Weingart M. A meta-analysis of occupational trichloroethylene exposure and liver cancer. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2007;81(2):127–143. doi: 10.1007/s00420-007-0201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anttila A, Pukkala E, Sallmen M, Hernberg S, Hemminki K. Cancer incidence among Finnish workers exposed to halogenated hydrocarbons. J Occup Environ Hygiene. 1995;37(7):797–806. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bahr D, Aldrich T, Seidu D, Brion G, Tollerud D, Muldoon S, Reinhart N, Youseefagha A, McKinney P, Hughes T, Chan C, Rice C, Brewer D, Freyberg R, Mohlenkamp A, Hahn K, Hornung R, Ho M, Dastidar A, Freitas S, Saman D, Ravdal H, Scutchfield D. Occupational exposure to trichloroethylene and cancer risk for workers at the Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2011;24(1):67–77. doi: 10.2478/s13382-011-0007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blair A, Hartge P, Stewart PA, McAdams M, Lubin J. Mortality and cancer incidence of aircraft maintenance workers exposed to trichloroethylene and other organic solvents and chemicals: extended follow up. Occup Environ Med. 1998;55(3):161–171. doi: 10.1136/oem.55.3.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boice JD, Jr, Marano DE, Cohen SS, Mumma MT, Blot WJ, Brill AB, Fryzek JP, Henderson BE, McLaughlin JK. Mortality among Rocketdyne workers who tested rocket engines, 1948–1999. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48(10):1070–1092. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000240661.33413.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cocco P, t’Mannetje A, Fadda D, Melis M, Becker N, de Sanjose S, Foretova L, Mareckova J, Staines A, Kleefeld S, Maynadie M, Nieters A, Brennan P, Boffetta P. Occupational exposure to solvents and risk of lymphoma subtypes: results from the Epilymph case–control study. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(5):341–347. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.046839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelsh MA, Alexander DD, Mink PJ, Mandel JH. Occupational trichloroethylene exposure and kidney cancer: a meta- analysis. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):95–102. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipworth L, Sonderman JS, Mumma MT, Tarone RE, Marano DE, Boice JD, Jr, McLaughlin JK. Cancer mortality among aircraft manufacturing workers: an extended follow-up. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(9):992–1007. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31822e0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandel JH, Kelsh MA, Mink PJ, Alexander DD, Kalmes RM, Weingart M, Yost L, Goodman M. Occupational trichloroethylene exposure and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a meta- analysis and review. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(9):597–607. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.022418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purdue MP, Bakke B, Stewart P, De Roos AJ, Schenk M, Lynch CF, Bernstein L, Morton LM, Cerhan JR, Severson RK, Cozen W, Davis S, Rothman N, Hartge P, Colt JS. A case–control study of occupational exposure to trichloroethylene and non- Hodgkin lymphoma. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(2):232–238. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raaschou-Nielsen O, Hansen J, McLaughlin JK, Kolstad H, Christensen JM, Tarone RE, Olsen JH. cancer risk among workers at Danish companies using trichloroethylene: a cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(12):1182–1192. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radican L, Blair A, Stewart P, Wartenberg D. Mortality of aircraft maintenance workers exposed to trichloroethylene and other hydrocarbons and chemicals: extended follow-up. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(11):1306–1319. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181845f7f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang R, Zhang Y, Lan Q, Holford TR, Leaderer B, Hoar Zahm S, Boyle P, Dosemeci M, Rothman N, Zhu Y, Qin Q, Zheng T. Occupational exposure to solvents and risk of non- Hodgkin lymphoma in Connecticut women. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(2):176–185. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao Y, Krishnadasan A, Kennedy N, Morgenstern H, Ritz B. Estimated effects of solvents and mineral oils on cancer incidence and mortality in a cohort of aerospace workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(4):249–258. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang Y-M, Tai C-F, Yang S-C, Chen C-J, Shih T-S, Lin RS, Liou S-H. A cohort mortality study of workers exposed to chlorinated organic solvents in Taiwan. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9):652–660. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan RW, Kelsh MA, Zhao K, Heringer S. Mortality of aerospace workers exposed to trichloroethylene [Erratum appears in Epidemiology 2000 May;11(3):360] Epidemiology. 1998;9(4):424–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caldwell JC, Keshava N, Evans MV. Difficulty of mode of action determination for trichloroethylene: an example of complex interactions of metabolites and other chemical exposures. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2008;49(2):142–154. doi: 10.1002/em.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewandowski TA, Rhomberg LR. A proposed methodology for selecting a trichloroethylene inhalation unit risk value for use in risk assessment. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;41(1):39–54. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landrigan PJ, Wright RO, Cordero JF, Eaton DL, Goldstein BD, Hennig B, Maier RM, Ozonoff DM, Smith MT, Tukey RH. The NIEHS superfund research program: twenty-five years of translational research for public health. Environ Health Perspect. 2015 doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farber E. The multistep nature of cancer development. Cancer Res. 1984;44(10):4217–4223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prehn A, West D. Evaluating local differences in breast cancer incidence rates: a census-based methodology (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9(5):511–517. doi: 10.1023/A:1008809819218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clarke CA, Undurraga DM, Harasty PJ, Glaser SL, Morton LM, Holly EA. Changes in cancer registry coding for lymphoma subtypes: reliability over time and relevance for surveillance and study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15(4):630–638. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-05-0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morton LM, Turner JJ, Cerhan JR, Linet MS, Treseler PA, Clarke CA, Jack A, Cozen W, Maynadié M, Spinelli JJ, Costantini AS, Rüdiger T, Scarpa A, Zheng T, Weisenburger DD. Proposed classification of lymphoid neoplasms for epidemiologic research from the Pathology Working Group of the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph) Blood. 2007 doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-051672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]