There is perhaps nothing as simultaneously useful and dreaded as pain. In many ways, pain is the ultimate teacher. It teaches us to avoid fire, poison, sharp objects and many other things that could cause us harm. It alerts the body to injury and disease. But it is also unpleasant and, depending on intensity and duration, can have a drastic impact on quality of life. Another thing about pain: We have always had to deal with it, and we always will.

“Pain is a constant companion for humanity,” said Marcia Meldrum, an associate researcher in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The topic of pain management has been much discussed in medicine of late because of the opioid crisis. For a short period, opioids seemed to be the answer to the long-standing problem of how to relieve pain without putting patients at high risk of addiction. Turns out, that was wishful thinking.

“The thing about opioids is they are very effective in interrupting and shutting off pain signals in the brain,” said Meldrum. “They are very, very effective. But they are also very dangerous.”

The struggle to manage pain in patients effectively and safely has long been an issue in medicine. In her paper “A Capsule History of Pain Management,” published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Meldrum wrote that pain is the oldest medical problem, but has been little understood by physicians throughout history.

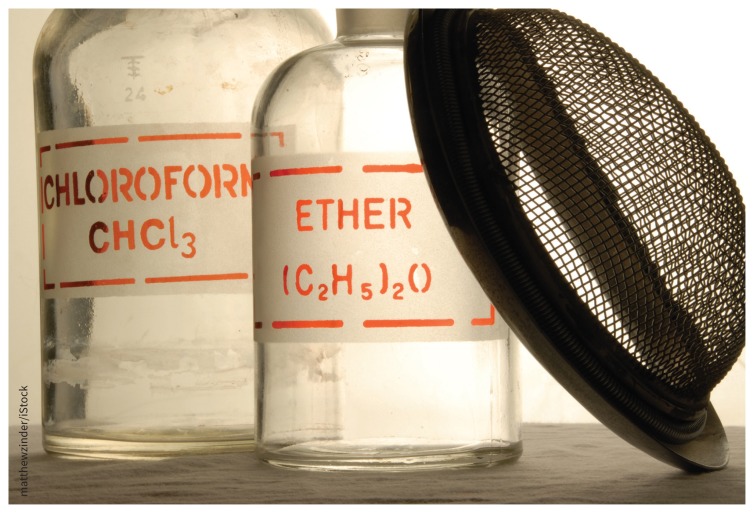

In the 1600s, many European doctors gave their patients opium to relieve pain. By the 1800s, ether and chloroform were introduced as anesthetics for surgery. Some doctors were concerned, however, about the ethics of operating on unconscious patients. Others suggested that relieving pain might hamper the healing process.

“But the surgeons could not long resist their new power to perform longer and more complex procedures, and most patients thought anesthesia a divine blessing,” wrote Meldrum.

By the 1900s, morphine and heroin came into use as pain medications. It was also the start of doctors being torn between wanting to improve the quality of their patients’ lives, while fearing the treatment would make people vulnerable to addictions.

Around this time, the subject of chronic pain without obvious pathology also became of greater interest to physicians. Previously, pain was mostly considered a problem to manage in acute care (related to injury, for example, or surgery) or during a painful death from cancer. Other patients complaining of pain were “often regarded as deluded or were condemned as malingers or drug abusers.” Patients who didn’t want to use drugs, or couldn’t access them, turned to psychotherapy or were referred for neurosurgery.

“Chronic pain is still one of the most difficult conditions to treat,” said Meldrum. “It is extremely difficult to assess the short-term and long-term effects of any particular treatment that you use. Pain is very individual. The only way to tell if someone is in pain is to ask them.”

Another reason chronic pain is so complex to address is that naysayers about the condition are partially correct, noted Meldrum. It is, to a degree, in your head, though not in the pejorative sense. Pain signals travel through the body’s nervous system, but so do emotional and cognitive information. As people develop pain conditions, they become anxious. That anxiety reinforces the pain signals.

Historically, medicine has turned to drugs to eliminate, relieve or reduce pain in patients.

Image courtesy of matthewzinder/iStock

“Essentially, your cognition becomes directed toward pain,” said Meldrum. “The most important thing to learn to do is to not anticipate or dwell on the pain. The more you think about pain, the more pain there will be.”

The formation of pain as a field of medicine began in the 1960s. By the 1970s, the field had a dedicated research journal (Pain) and association (International Association for the Study of Pain). The concept of interdisciplinary pain teams was also introduced and found to be effective, but the problem, which remains to this day, is that these teams are expensive and rarely covered by health plans.

“Insurance is not set up to cover multiple visits at once with several doctors for the same condition,” said Meldrum.

In the 1980s, several prominent pain specialists suggested there was “low incidence of addictive behavior” associated with opioids and pushed for increased use of the drugs to treat long-term, non-cancer pain, Meldrum noted in her paper “The Ongoing Opioid Prescription Epidemic: Historical Context.” Thus began a 20-year campaign, backed by the pharmaceutical industry, that convinced many physicians they could prescribe opioids more freely, and with a clean conscience. It also turned out to be a driver of the current opioid crisis, along with factors such as “the shrewd targeting of a market niche by a pharmaceutical manufacturer, the cost-benefit calculations of insurance carriers, and the creative entrepreneurship of drug traffickers.”

According to Meldrum, the problem of how to deal with pain isn’t going anywhere. And if drugs remain the affordable and effective option, people will continue to turn to them, no matter the risks. We have a “prescription culture,” she suggested, and it is only growing as time goes on.

“We are in this culture now where too many people see drugs as the answer not only to pain, but to improving their lives,” said Meldrum. “Pain can make it impossible to live your life. You lose so much quality of life. So for many people, if the solution also means they may become somewhat dependent on a drug, they probably think, ‘Well, that would be better than this.’”

Footnotes

Posted on cmajnews.com on Dec. 14, 2017.