Abstract

Geographic atrophy is a blinding form of age-related macular degeneration characterized by death of the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE). In this disease, the RPE displays evidence of DICER1 deficiency, resultant accumulation of endogenous Alu retroelement RNA, and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. How the inflammasome is activated in this untreatable disease is largely unknown. Here we demonstrate that RPE degeneration in human cell culture and in mouse models is driven by a non-canonical inflammasome pathway that results in activation of caspase-4 (caspase-11 in mice) and caspase-1, and requires cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-dependent interferon-β (IFN-β) production and gasdermin D-dependent interleukin-18 (IL-18) secretion. Reduction of DICER1 levelsor accumulation of Alu RNA triggers cytosolic escape of mitochondrial DNA, which engages cGAS. Moreover, caspase-4, gasdermin D, IFN-β, and cGAS levels are elevated in the RPE of human eyes with geographic atrophy. Collectively, these data highlight an unexpected role for cGAS in responding to mobile element transcripts, reveal cGAS-driven interferon signaling as a conduit for mitochondrial damage-induced inflammasome activation, expand the immune sensing repertoire of cGAS and caspase-4 to non-infectious human disease, and identify new potential targets for treatment of a major cause of blindness.

Age-related macular degeneration affects over 180 million people1, and is the leading cause of blindness among the elderly across the world. Degeneration of the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE), a monolayer of cells that provide trophic support to photoreceptors2,3, is the hallmark of geographic atrophy. the RNase DICER1 are reduced in the RPE of human eyes with geographic atrophy, leading to accumulation of toxic mobile element Alu RNA transcripts4; these Alu transcripts induce RPE cell death by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome5. Although NLRP3 inflammasome activation has been widely implicated in macular degeneration6–8, the mechanisms regulating the inflammasome in this disease remain elusive. Here we demonstrate that DICER1 deficit/Alu RNA-driven RPE degeneration in mouse models of macular degeneration is mediated by caspase-4- and gasdermin D-dependent inflammasome activation. Surprisingly this non-canonical inflammasome is dependent on the activation of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-driven type I interferon signaling (IFN) by cytosolic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA).

RESULTS

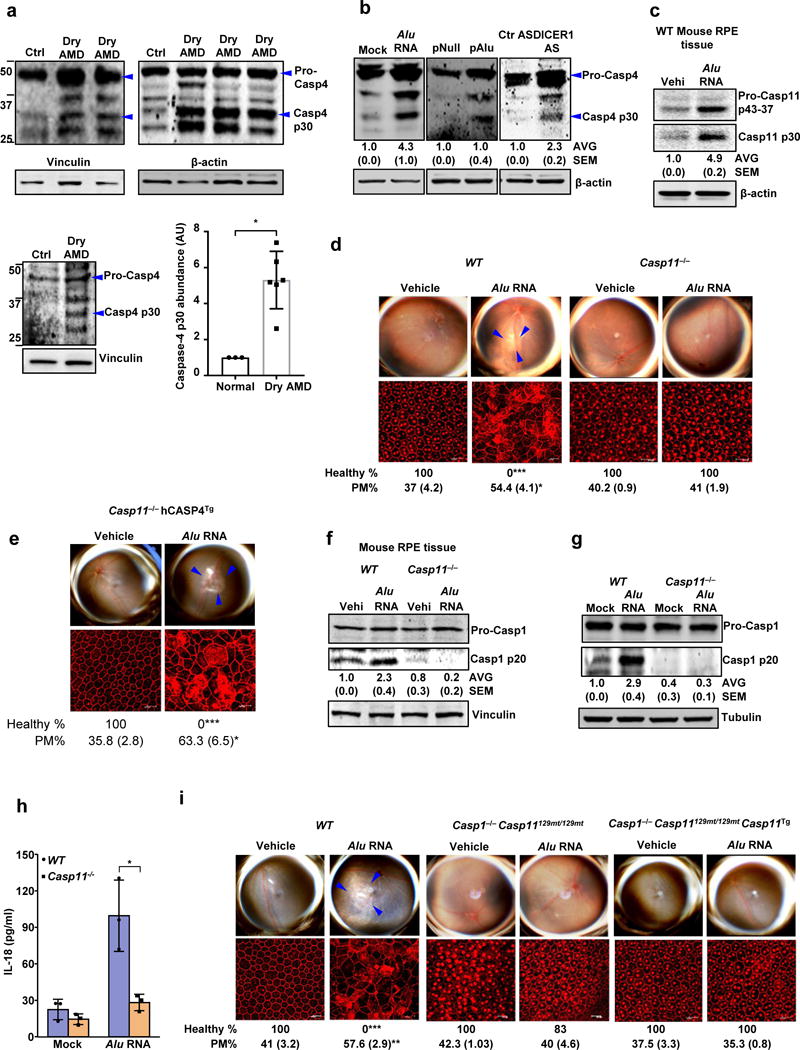

Caspase-4 is activated in AMD

Caspase-4 (caspase-11 is the corresponding mouse protein), which governs non-canonical inflammasome activation, was recently implicated in the immune response to exogenous pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as intracellular LPS9,10 and endogenously produced oxidized phospholipids (oxPAPC)11. Caspase-4 abundance in the RPE and choroid of human eyes with geographic atrophy was significantly increased compared to normal human eyes from aged subjects, as monitored by western blotting (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Introduction of in vitro transcribed Alu RNA or plasmid-mediated enforced expression of Alu RNA (pAlu) induced and activated caspase-4 in primary human RPE cells, as evident by increased abundance of the p30 cleavage fragments (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). Anti-sense oligonucleotide-mediated knockdown of DICER1 similarly induced caspase-4 activation in human RPE cells (Fig. 1b), which was blocked by concomitant anti-sense mediated inhibition of Alu RNA (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Caspase-11 activation was induced by subretinal injection of Alu RNA in wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 1c), and by Alu RNA transfection in primary RPE cells isolated from WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Collectively, these data identify caspase-4 as preferentially activated in human AMD, and indicate that dysregulation of DICER1 and Alu RNA lead to caspase-4 activation in this condition.

Figure 1. Caspase-4/11 in geographic atrophy and RPE degeneration.

(a) Left and top quadrants, immunoblots for pro-caspase-4 (pro-Casp4) and the p30 cleavage product of caspase-4 (Casp4 p30) in the RPE of human eyes with geographic atrophy (dry AMD) as compared to unaffected controls (Ctr). Specific bands of interest are indicated by arrowheads. Lower right quadrant, densitometry of the bands corresponding to caspase-4 p30 normalized to loading control. The molecular weight markers are indicated on the left side of the blot (Data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3 control eyes; n = 6 dry AMD eyes; *P = 0.002, two-tailed t test). (b) Immunoblots for pro-Casp4 and Casp4 p30 in human RPE cells mock transfected (just transfection mixture) or transfected with Alu RNA; Alu expression plasmid (pAlu) or empty vector (pNull); or DICER1 or control (Ctr) anti-sense oligonucleotides (AS). Specific bands of interest are indicated by arrowheads. (c) Immunoblot for pro-caspase-11 (Pro-Casp11) and the p30 cleavage product of caspase-11 (Casp11 p30) in RPE tissue of WT mice injected subretinally with Alu RNA or vehicle (Vehi). n = 3 mice per group. (d,e) Top, fundus photographs of the retinas of WT (n = 8 eyes) and Casp11−/− (n = 10 eyes) mice, (d) and Casp11−/− (n = 8 eyes) mice expressing a human caspase-4 transgene (Casp11−/− hCasp4Tg) (e) injected with vehicle or Alu RNA. The degenerated retinal area is outlined by blue arrowheads. Bottom, immunostaining with zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) antibody to visualize RPE cellular boundaries; loss of regular hexagonal cellular boundaries is indicative of degenerated RPE. (f) Immunoblots of pro-caspase-1 (pro-Casp1) and the p20 cleavage product of caspase-1 (Casp1 p20) in RPE tissue of WT and Casp11−/− mice injected subretinally with vehicle (Vehi) or Alu RNA. n = 3 mice per group. (g) Immunoblots of pro-caspase-1 and the p20 cleavage product of caspase-1 in WT and Casp11−/− mouse RPE cells treated with Alu RNA. (h) IL-18 secretion by WT and Casp11−/− mouse RPE cells mock transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. n = 3 independent experiments. Data presented are mean ± SD; *P = 0.014, two-tailed t test. (i) Top, fundus photographs of the retinas of WT (n = 8 eyes), caspase-1 and caspase-11 deficient (n = 7 eyes) mice (Casp1−/− Casp11129mt/129mt) as well as Casp1−/− Casp11129mt/129mt (n = 8 eyes) mice expressing functional mouse caspase-11 from a bacterial artificial chromosome transgene (Casp1−/− Casp11129mt/129mt Casp11Tg) subretinally injected with vehicle or Alu RNA. For all immunoblots, cropped gel image of bands of interest of representative immunoblots of three independent experiments and densitometric analysis (mean (SEM)) are shown. Tubulin or β-actin or Vinculin was as a loading control as indicated in each blot. In d, e and i, binary (Healthy %) and morphometric quantification (PM, polymegethism (mean (SEM))) of RPE degeneration are shown (Fisher’s exact test for binary; two-tailed t test for morphometry; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). The degenerated retinal area is outlined by blue arrowheads in the fundus images. Loss of regular hexagonal cellular boundaries in ZO-1 stained flat mounts is indicative of degenerated RPE.

Caspase-4 is required for Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration and inflammasome activation

We sought to determine whether caspase-4 is required for Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration, which was quantified both by binary grading and semi-automated cellular morphometry (Online Methods and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Exogenous delivery or endogenous over-expression of Alu RNA induced RPE degeneration in WT mice (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1f). In contrast, subretinal injection of neither Alu RNA nor pAlu induced RPE degeneration in Casp11−/− mice (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1f). 129S6 mice, which lack functional caspase-11 due to a passenger mutation12, also were resistant to RPE degeneration induced by Alu RNA or pAlu (Supplementary Fig. 1g). Subretinal delivery of a cell-permeable, non-immunogenic 17+2-nt cholesterol-conjugated siRNA13,14 targeting Dicer1 induced RPE degeneration in WT but not 129S6 mice (Supplementary Fig. 1h). Transgenic expression of human caspase-4 in caspase-11 deficient mice (Casp11−/− hCASP4TG)15 restored susceptibility to Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration (Fig. 1e), demonstrating that human caspase-4 can compensate for mouse caspase-11 in this system. Collectively, these data demonstrate the critical role of caspase-4 (or mouse caspase-11) in responding to pathological accumulation of endogenous Alu mobile element transcripts.

Previously we reported that Alu RNA does not induce RPE degeneration in caspase-1 deficient mice5. However, this Casp1−/− strain was subsequently reported to also lack functional caspase-11 as a result of a passenger mutation in the 129S6 genetic background of this strain12; thus, the genotype of these mice is properly referred to as Casp1−/− Casp11129mt/129mt. We sought to clarify the molecular hierarchy of caspases-1 and 11 in response to Alu RNA. Whereas Alu RNA treatment induced caspase-1 activation in WT mice or RPE cells, Alu RNA failed to stimulate caspase-1 activation in Casp11−/− mice (Fig. 1f), or in primary RPE cells isolated from Casp11−/− mice (Fig. 1g). Reconstitution of caspase-11 into Casp11−/− mouse RPE cells restored caspase-1 activation by Alu RNA (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Moreover, Alu RNA failed to induce IL-18 secretion in Casp11−/− mouse RPE cells (Fig. 1h). In contrast, caspase-11 was dispensable for IL-18 secretion induced by the canonical inflammasome agonist monosodium urate (MSU) crystals (Supplementary Fig. 10d). These data suggest that caspase-11 is required for caspase-1 activation and IL-18 secretion induced by Alu RNA.

Alu RNA did not induce RPE degeneration in Casp1−/− Casp11129mt/129mt Casp11Tg mice12, in which mouse caspase-11 was functionally reconstituted by a bacterial artificial chromosome transgene (Fig. 1i and Supplementary Fig. 2c. Additionally, as previously observed5, Casp1−/− Casp11129mt/129mt mice were not susceptible to Alu-induced RPE degeneration (Fig. 1i and Supplementary Fig. 2c), suggesting that both caspase-4/11 and caspase-1 are required for Alu toxicity.

Given that we previously demonstrated that PYCARD, an adaptor protein involved in inflammasome activation, and the purinoceptor P2X7 (encoded by P2rx7) are required for Alu toxicity5,16,17, we next assessed whether PYCARD and P2X7 are also required for Alu RNA-induced caspase-11 activation. Alu RNA-induced activation of caspase-11 was reduced in P2rx7−/− but not Pycard−/− mouse RPE cells, suggesting that caspase-11 is mechanistically positioned between these signaling molecules (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e). Collectively these findings support a model of non-canonical inflammasome activation by Alu RNA wherein caspase-4/11 lies upstream of caspase-1 activation.

Recent studies have implicated an endogenous lipid molecule, oxidized phospholipid oxPAPC (oxidized 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), in caspase-11-mediated non-canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation11. To test whether Alu RNA promotes accumulation of this type of endogenous ligand, we extracted lipids from Alu RNA-treated human RPE cells and used liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to quantify the following products of 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-3-phosphatidylcholine (PAPC): 1-palmitoyl-2-glutaryl-3-phosphatidylcholine (PGPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-oxovaleryl)-3-phosphatidylcholine (POVPC), and 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-3-phosphatidylcholine (LysoPC) (Supplementary Fig. 4a-c). Compared to control cells, Alu RNA-treated human RPE cells exhibited a two-fold increase in oxPAPC- PGPC and LysoPC levels (Supplementary Fig. 4d), concomitantly with a trend towards a reduction in precursor PAPC levels (Supplementary Fig. 4d). These results suggest an indirect mechanism of Alu-driven caspase-11 engagement, possibly via oxidized phospholipid-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs).

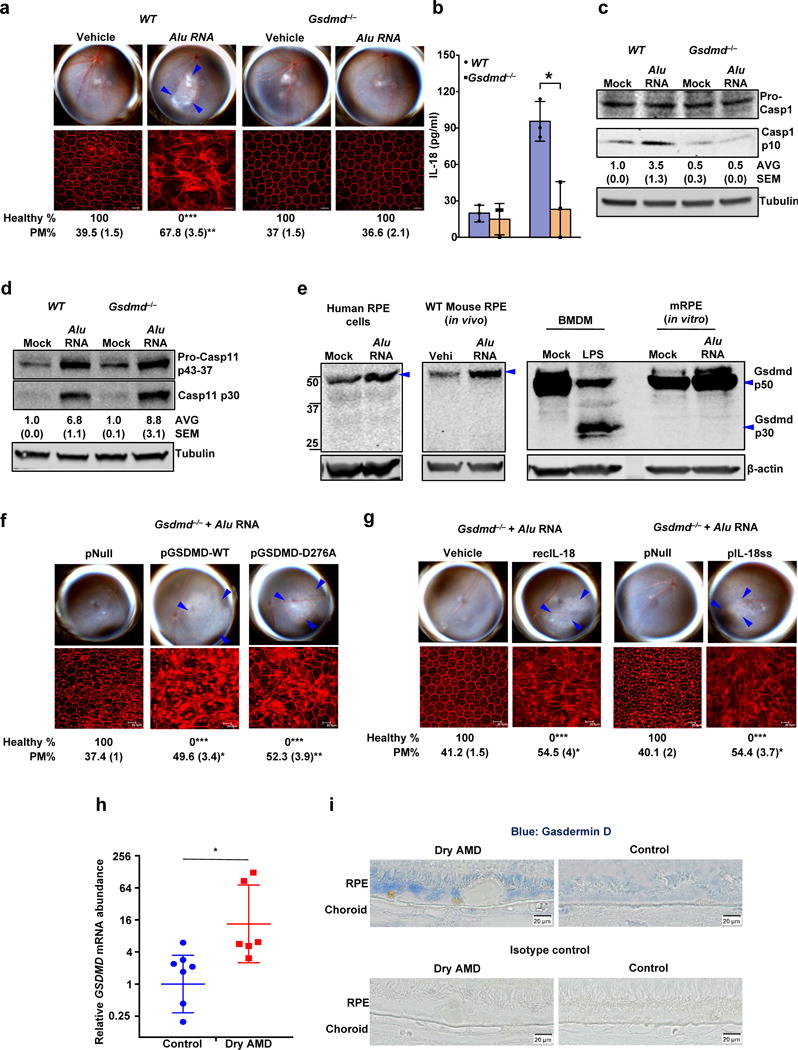

Gasdermin D is required for Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration and inflammasome activation

Caspase-11-and caspase-1-dependent pyroptotic cell death can be executed by a pore-forming protein, gasdermin D (encoded by Gsdmd)18–20. We found that Gsdmd−/− mice were resistant to Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). Consistent with the role of gasdermin D in non-canonical inflammasome activation by intracellular LPS19, Alu RNA-induced caspase-1 activation and IL-18 secretion were reduced in Gsdmd−/− mouse RPE cells (Fig. 2b, c). However, caspase-11 activation in Gsdmd−/− mice was not impaired (Fig. 2d), suggesting that loss of caspase-1 activation in Gsdmd−/− mouse RPE cells is not due to an indirect effect of gasdermin D on caspase-11, and that, mechanistically, caspase-11 lies upstream of gasdermin D.

Figure 2. Gasdermin D in geographic atrophy and RPE degeneration.

(a) Top, fundus photographs of eyes of WT (n = 6 eyes), and Gsdmd−/− (n = 10 eyes) mice subretinally injected with vehicle or Alu RNA. Bottom, immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts of the same eyes showing RPE cell boundaries. (b) IL-18 secretion by WT and Gsdmd−/− mouse RPE cells mock transfected or transfected with Alu RNA (n = 3 independent experiments; Data presented are mean ± SD, *P = 0.01, two-tailed t test) (c) Immunoblots of pro-caspase-1 (pro-Casp1) and the p10 cleavage product of caspase-1 (Casp1 p10) in WT and Gsdmd−/− mouse RPE cells mock transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. (d) Immunoblots of pro-caspase-11 (pro-Casp11) and the p30 cleavage product of caspase-11 (Casp11 p30) in WT and Gsdmd−/− mouse RPE cells mock transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. (e) Immunoblots of Gasdermin D and cleavage product of Gasdermin D (Gsdmd p30) in mock transfected or Alu RNA transfected human primary RPE cells, WT mouse primary RPE cells, and WT BMDM as well as in RPE tissue from WT mice subretinally injected with vehicle or Alu RNA. (f, g) Fundus photographs and immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts, (f) Gsdmd−/− mice reconstituted via in vivo subretinal transfection of empty vector plasmid (pNull; n = 4 eyes), plasmids expressing wild type gasdermin D (pGSDMD-WT; n = 4 eyes) or mutant gasdermin D incapable of undergoing p30 cleavage (pGSDMD-D276A; n = 5 eyes) subretinally injected with Alu RNA. (g) Gsdmd−/− mice subretinally administered vehicle control (Vehicle; n = 4 eyes), recombinant mature IL-18 (recIL-18; n = 4 eyes), mature IL-18 expression plasmid (pIL-18ss; n = 5 eyes) or empty vector control (pNull; n = 4 eyes) were subretinally injected with Alu RNA. (h) RT-qPCR examination of GSDMD mRNA abundance in the RPE tissue of human AMD eyes (n = 7 eyes) and in healthy age-matched control eyes (n = 6 eyes). *P = 0.045, two-tailed t test; error bars denote geometric means with 95% confidence intervals. (i) Immunolocalization of gasdermin D in the RPE of human geographic atrophy eyes and age-matched healthy controls. For all immunoblots, cropped gel image of bands of interest of representative immunoblots of three independent experiments and densitometric analysis (mean (SEM)) are shown. In a, f and g, binary (Healthy %) and morphometric (PM, polymegethism (mean (SEM)) quantification of RPE degeneration are shown (Fisher’s exact test for binary; two-tailed t test for morphometry; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). Loss of regular hexagonal cellular boundaries in ZO-1 stained flat mounts is indicative of degenerated RPE. The degenerated retinal area is outlined by blue arrowheads in the fundus images.

Execution of pyroptosis by gasdermin D requires its cleavage into a pore-forming p30 fragment21. Interestingly, although gasdermin D was required for Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration and IL-18 secretion, we did not observe its cleavage into a p30 fragment in Alu RNA-treated RPE cells in cell culture or in RPE cells in vivo (Fig. 2e); however, as reported19 previously19, intracellular LPS induced p30 cleavage in mouse bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) (Fig. 2e).

Next, we directly tested whether gasdermin D p30 cleavage is dispensable for the toxicity of Alu RNA by reconstituting Gsdmd−/− mice with WT gasdermin D (pGSDMD-WT) or mutant gasdermin D (pGSDMD-D276A); pGSDMD-D276A is unable to undergo cleavage into the pyroptotic p30 fragment19. Notably, expression of either WT or mutant gasdermin D in Gsdmd−/− mice restored susceptibility to Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration (Fig. 2f), suggesting a non-pyroptotic function for gasdermin D in this system.

Previously we demonstrated that Alu RNA induces activation of caspase-3 (refs. 4,22), as well as activation of caspase-8, Fas, and FasL22, and that this well-characterized pathway of apoptotic induction is critical for the RPE toxicity of Alu RNA. In addition, we and others have provided molecular evidence consistent with apoptosis in the RPE in human eyes with geographic atrophy4,23. To further clarify the role of apoptosis in Alu RNA-induced cell death, we performed live-cell imaging of annexin-V and propidium iodide (PI) staining in primary human RPE cells. Cells treated with Alu RNA developed plasma membrane blebs and displayed an annexin-V+ PI− staining pattern, findings that are consistent with early apoptosis. After several hours of annexin-V positivity, cells frequently swelled and became PI–positive, consistent with late apoptosis or secondary necrosis24 (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). In vivo studies recapitulated these cell culture findings: RPE flat mounts from Alu RNA-exposed WT mice displayed predominantly annexin-V+ PI− cell death (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Alu RNA treatment of RPE cells induced cleavage of caspase-3 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) (Supplementary Fig. 7b), further supporting induction of an apoptotic cell death pathway. These findings, coupled with our earlier demonstration that neither necrostatin-1, an inhibitor of primary necrosis, nor glycine, an inhibitor of pyroptosis25, blocks lu RNA-induced RPE degeneration5,22, suggest that Alu RNA promotes cell death primarily via apoptosis rather than pyroptosis or necrosis in RPE cells.

Next, we explored the roles of IL-18 and gasdermin D in Alu RNA-induced cell death. The resistance of Gsdmd−/− mice to Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration was overcome by recombinant mature IL-18 or subretinal injection of a plasmid expressing mature IL-18, suggesting that this resistance is due to loss of IL-18 secretion (Fig. 2g). Supportive of this concept, Alu RNA failed to induce secretion of IL-18 in Gsdmd−/− mouse RPE cells, and this effect was rescued by reconstitution of the cells with either pGSDMD-WT or the p30 cleavage-incompetent pGSDMD-D276A (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Additionally, whereas annexin-V+ cells were not visible in RPE flat mounts of Alu RNA-treated Gsdmd−/− mice, administration of recombinant mature IL-18 led to the appearance of numerous annexin-V+ PI− cells (Supplementary Fig. 8). Taken together with our previous demonstration that IL-18 neutralization or IL-18 receptor deficiency in mice blocks Alu RNA toxicity in vivo5, these findings suggest that gasdermin D is required for Alu RNA-induced inflammasome activation, and for RPE toxicity driven via IL-18-dependent apoptosis.

Gasdermin D mRNA abundance was elevated in the RPE of human eyes with geographic atrophy, as compared to eyes from unaffected age-matched controls (Fig. 2h). In contrast, we observed similar levels of MIP-1α, IL-8, and IL-6 mRNA in geographic atrophy and normal specimens (Supplementary Fig. 5d), suggesting that global elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines does not occur in GA, but rather a more specific increase in the expression of inflammasome pathway genes. We also observed increased gasdermin D protein expression in the RPE of human eyes with geographic atrophy, as compared to eyes from unaffected age-matched controls (Fig. 2i).

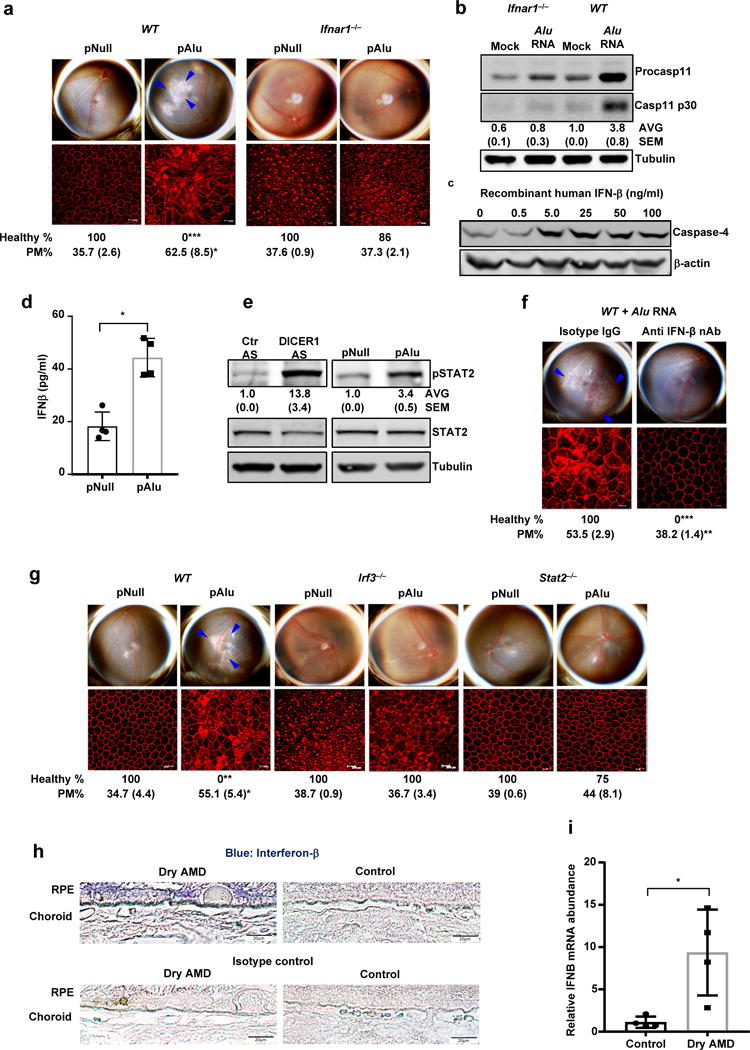

Alu RNA-induced non-canonical inflammasome activation is driven by Type I interferon (IFN) signaling

To interrogate the upstream regulation of caspase-4, we focused on interferon signaling, which is involved in activation of the caspase-11 driven non-canonical inflammasome10. Alu RNA did not induce RPE degeneration or caspase-11 activation in Ifnar1−/− mice or Ifnar1−/− mouse RPE cells (Fig. 3a, b), which are deficient in the type I interferon-α/β receptor (IFNAR). Treatment with recombinant interferon-β increased caspase-4 abundance in human RPE cells (Fig. 3c). Alu RNA induced secretion of interferon-β (Fig. 3d) and phosphorylation of IRF3 (Supplementary Fig. 9a), a transcription factor that induces production of interferon-β. Alu RNA also induced phosphorylation of STAT2 (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 9a, b), a signaling molecule activated by type-I interferons downstream of IFNAR. Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration was blocked by administration of an IFN-β neutralizing antibody (Fig. 3f). Moreover, Alu RNA did not induce RPE degeneration in Irf3−/− or Stat2−/− mice (Fig. 3g, and Supplementary Fig. 9c, d), and induction of caspase-11 activation by Alu RNA was reduced in Stat2−/− mouse RPE cells (Supplementary Fig. 9e). Human eyes with geographic atrophy displayed pronounced IFN-β expression in the RPE, as compared to eyes from unaffected age-matched controls (Fig. 3h, i). Taken together, these data suggest that Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration is dependent on regulation of the non-canonical inflammasome by type I interferon signaling.

Figure 3. Non-canonical inflammasome activation and RPE degeneration induced by Alu RNA is mediated by interferon signaling.

(a) Top, fundus photographs of eyes of WT (n = 7 eyes) and Ifnar−/− (n = 14 eyes) mice subretinally injected with Alu expression plasmid (pAlu) or empty vector (pNull). Bottom, immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts of the above eyes showing RPE cell boundaries. (b) Immunoblot of pro-caspase-11 (pro-Casp1) and the p30 cleavage product of caspase-11 (Casp11 p30) in WT and Ifnar−/− mouse RPE cells mock transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. (c) Immunoblot of pro-caspase-4 in IFN-β-treated human RPE cells. (d) IFN-β secretion by human RPE cells transfected with Alu expression plasmid (pAlu) or empty vector (pNull). Data presented are mean ± SD; n = 3 independent experiments; *P = 0.0012, two-tailed t test. (e) Immunoblot of phosphorylated STAT2 (pSTAT2) and total STAT2 in human RPE cells transfected with Alu expression plasmid (pAlu) or empty vector (pNull) or DICER1 or control (Ctr) anti-sense oligonucleotides (AS). (f) Fundus photographs and immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts of WT mice subject to Alu RNA co-administration with IFN-β neutralizing antibody (n = 6 eyes) or Isotype IgG (n = 4 eyes). (g) Fundus photographs and immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts of WT (n = 6 eyes) or Irf3−/− (n = 6 eyes) or Stat2−/− (n = 7 eyes) mice subretinally injected with Alu expression plasmid (pAlu) or empty vector (pNull). (h) Immunolocalization of IFN-β in the RPE of human geographic atrophy eyes and age-matched unaffected controls. Representative image from control and Dry AMD eyes are presented, n = 4 eyes. (i) Abundance of IFN-β mRNA in the RPE of the human geographic atrophy eyes compared to age-matched healthy controls, (Data presented are mean ± SEM; n = 4 eyes; *P = 0.018, two-tailed t test). For all immunoblots, cropped gel image of bands of interest of representative immunoblots of three independent experiments and densitometric analysis (mean (SEM)) are shown. In a, f and g, binary (Healthy %) and morphometric (PM, polymegethism (mean (SEM)) quantification of RPE degeneration are shown (Fisher’s exact test for binary; two-tailed t test for morphometry; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). Loss of regular hexagonal cellular boundaries in ZO-1 stained flat mounts is indicative of degenerated RPE. The degenerated retinal area is outlined by blue arrowheads in the fundus images.

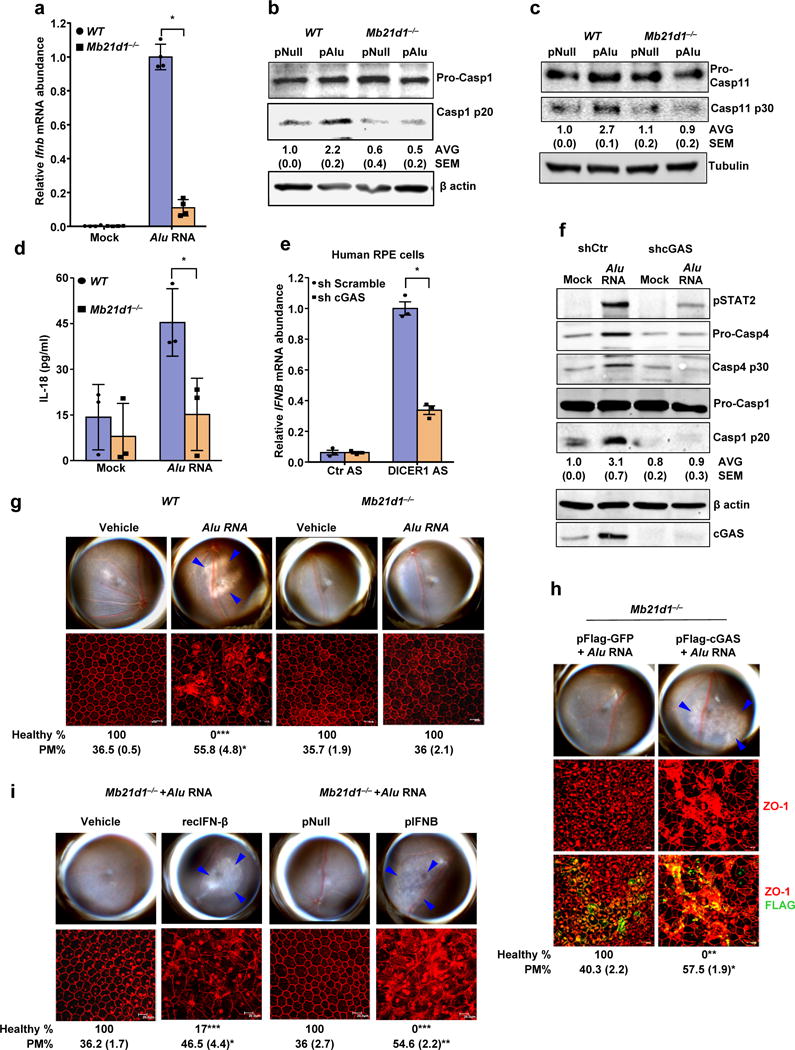

cGAS-driven IFN signaling licenses non-canonical NLRP3 inflammasome

We sought to identify the upstream activator of IRF3-driven interferon signaling induced by Alu RNA. We previously showed that Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration is independent of several IRF3-activating signaling molecules, including various RNA sensors: TLR3, TLR4, TLR9, RIG-I, MDA5, MAVS, and TRIF5. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS, encoded by Mb21d1) has emerged as an innate immune sensor that can activate type I interferon signaling26. Additionally, a role for cGAS in broadly inhibiting several RNA viruses has also been reported27.

We found that Alu RNA upregulated cGAS mRNA and protein in human RPE cells (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). In contrast to WT mouse RPE cells, Alu RNA did not induce interferon-β (Fig. 4a), activate caspase-1 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 10c) or caspase-11 (Fig. 4c), or induce IL-18 secretion (Fig. 4d) in Mb21d1−/− mouse RPE cells. In contrast, inflammasome activation by MSU crystals was unimpaired in Mb21d1−/− mouse RPE cells (Supplementary Fig. 10d). In human RPE cells, DICER1 knockdown-induced induction of interferon-β, STAT2 phosphorylation, and activation of caspase-4 and caspase-1, were all inhibited by knockdown of cGAS (Fig. 4e, f and Supplementary Fig. 10e, f). Corroborating these data, Alu RNA did not induce RPE degeneration in Mb21d1−/− mice (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 10g, h). Additionally, reconstitution of mouse cGAS restored IFN-β induction in Mb21d1−/− mouse RPE cells and RPE degeneration in Mb21d1−/− mice (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Fig. 10i, and Supplementary Fig. 11a). Moreover, the resistance of Mb21d1−/− mice to Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration was overcome by recombinant IFN-β administration or IFN-β expression via subretinal plasmid transfection (Fig. 4i), suggesting that this resistance is indeed due to lack of IFN signaling.

Figure 4. cGAS driven signaling licenses non-canonical inflammasome and RPE degeneration.

(a) Relative abundance of Ifnb mRNA in WT and Mb21d1−/− mouse RPE cells mock-transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. Data presented are mean ± SEM; n = 4 cell culture replicates; *P = 0.0001, two-tailed t test. (b) Immunoblots of pro-caspase-1 (pro-Casp1) and the p20 cleavage product of caspase-1 (Casp1 p20) in WT and Mb21d1−/− mouse RPE cells transfected with Alu expression plasmid (pAlu) or empty vector control (pNull). (c) Immunoblots of pro-caspase-11 (pro-Casp1) and the p30 cleavage product of caspase-1 (Casp11 p30) in WT and Mb21d1−/− mouse RPE cells transfected with Alu expression plasmid (pAlu) or empty vector control (pNull). (d) IL-18 secretion by WT and Mb21d1−/− mouse RPE cells mock transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. Data presented are mean ± SD; n = 3 independent experiments; *P = 0.032, two-tailed t test. (e) Relative abundance of IFNB mRNA in control (sh Scramble) or cGAS shRNA knockdown human RPE cells transfected with or DICER1 or control (Ctr) anti-sense oligonucleotides (AS). Data presented are mean ± SEM; n = 3 cell culture replicates; *P = 0.0002, two-tailed t test. (f) Immunoblot of phosphorylated STAT2 (pSTAT2); pro-caspase-4 and casp4 p30; pro-caspase-1 and p20 cleavage casp1 p20 in control (sh Scramble) or cGAS shRNA knockdown human RPE cells mock-transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. Knockdown efficiency of cGAS is shown by cGAS immunoblot and tubulin was used as a loading control. (g) Fundus photographs and immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts of WT (n = 6 eyes) and Mb21d1−/− (n = 8 eyes) mice subretinally injected with vehicle or Alu RNA. (h) Fundus photographs and immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts of Mb21d1−/− (n = 7 eyes) mice reconstituted by in vivo transfection of cGAS expression plasmid (pFlag-cGAS) or control GFP expression plasmid (pFlag-GFP), subretinally injected with Alu RNA. (i) Fundus photographs and immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts of Mb21d1−/− mice subretinally co-administered Alu RNA with recombinant IFN-β (n = 6 eyes), vehicle control (n = 6 eyes), IFN-β expression plasmid (pIFNB; n = 5 eyes) or empty vector control (pNull; n = 5 eyes). For all immunoblots, cropped gel image of bands of interest of representative immunoblots of three independent experiments and densitometric analysis (mean (SEM)) are shown. In g, h and i, binary (Healthy %) and morphometric (PM, polymegethism (mean (SEM)) quantification of RPE degeneration are shown (Fisher’s exact test for binary; two-tailed t test for morphometry; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). Loss of regular hexagonal cellular boundaries in ZO-1 stained flat mounts is indicative of degenerated RPE. The degenerated retinal area is outlined by blue arrowheads in the fundus images.

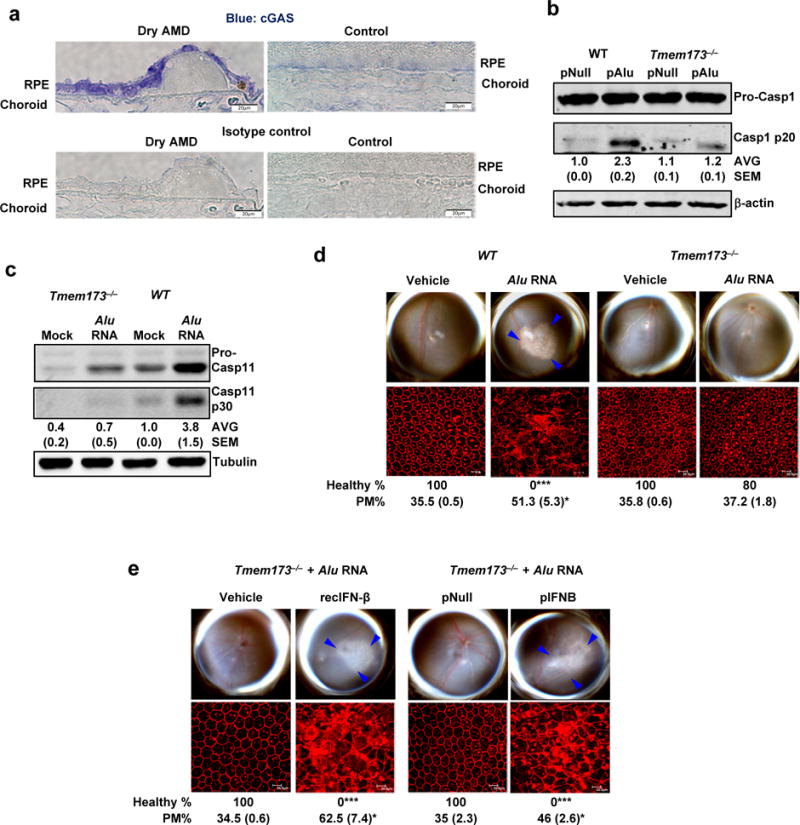

cGAS protein was more abundant in the RPE of human eyes with geographic atrophy as compared to eyes from unaffected age-matched controls (Fig. 5a). cGAS-driven interferon signaling can be transduced by the adaptor protein STING (encoded by Tmem173)26. Alu RNA did not induce IRF3 phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 11b, c) or activation of caspase-1 (Fig. 5b) or caspase-11 (Fig. 5c) in Tmem173−/− mouse RPE cells, and did not induce RPE degeneration in Tmem173−/− mice (Fig. 5d), pointing to the involvement of the cGAS-STING signaling axis in this system. As in the case of Mb21d1−/− mice, the resistance of Tmem173−/− mice to Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration was overcome by recombinant IFN-β administration or IFN-β expression via subretinal plasmid transfection (Fig. 5e), which again points to the requirement for IFN signaling in Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration.

Figure 5. cGAS in geographic atrophy and RPE degeneration.

(a) Immunolocalization of cGAS in the RPE of human geographic atrophy eyes and age-matched unaffected controls. Representative image from control and Dry AMD eyes are presented, n = 4 eyes. (b) Immunoblots of pro-caspase-1 and p20 cleavage product of caspase-1 (Casp1 p20) in WT and Tmem173−/− mouse RPE cells transfected with Alu expression plasmid (pAlu) or empty vector control plasmid (pNull). (c) Immunoblots of pro-caspase-11 and p30 cleavage product of caspase-11 (Casp11 p30) in WT and Tmem173−/− mouse RPE cells mock transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. (d) Fundus photographs and immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts of WT (n = 6 eyes) and Tmem173−/− (n = 10 eyes) mice subretinally injected with vehicle or Alu RNA. (e) Fundus photographs and immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts of Tmem173−/− mice subretinally co-administered Alu RNA with recombinant IFN-β (n = 4 eyes) or vehicle control (n = 4 eyes); or IFN-β expression plasmid (pIFNB; n = 4 eyes) or empty vector control (pNull; n = 4 eyes). For all immunoblots, cropped gel image of bands of interest of representative immunoblots of three independent experiments and densitometric analysis (mean (SEM)) are shown. In d and e, binary (Healthy %) and morphometric (PM, polymegethism (mean (SEM)) quantification of RPE degeneration are shown (Fisher’s exact test for binary; two-tailed t test for morphometry; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). Loss of regular hexagonal cellular boundaries in ZO-1 stained flat mounts is indicative of degenerated RPE. The degenerated retinal area is outlined by blue arrowheads in the fundus images.

Alu-driven cGAS activation is triggered by engagement with mtDNA

cGAS is activated by cytosolic DNA but not by poly(I:C), a synthetic double stranded RNA analog26. Consistent with the notion that cGAS does not recognize RNA directly, Alu RNA did not bind cGAS in an RNA immunoprecipitation assay (data not shown). Previous studies have implicated mitochondrial dysfunction in macular degeneration, including mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and downregulation of proteins involved in mitochondrial energy production and trafficking5,28,29. Cytosolic escape of mitochondrial components, such as DNA and formyl peptides, have been shown to activate innate immune pathways, including cGAS (refs. 30).

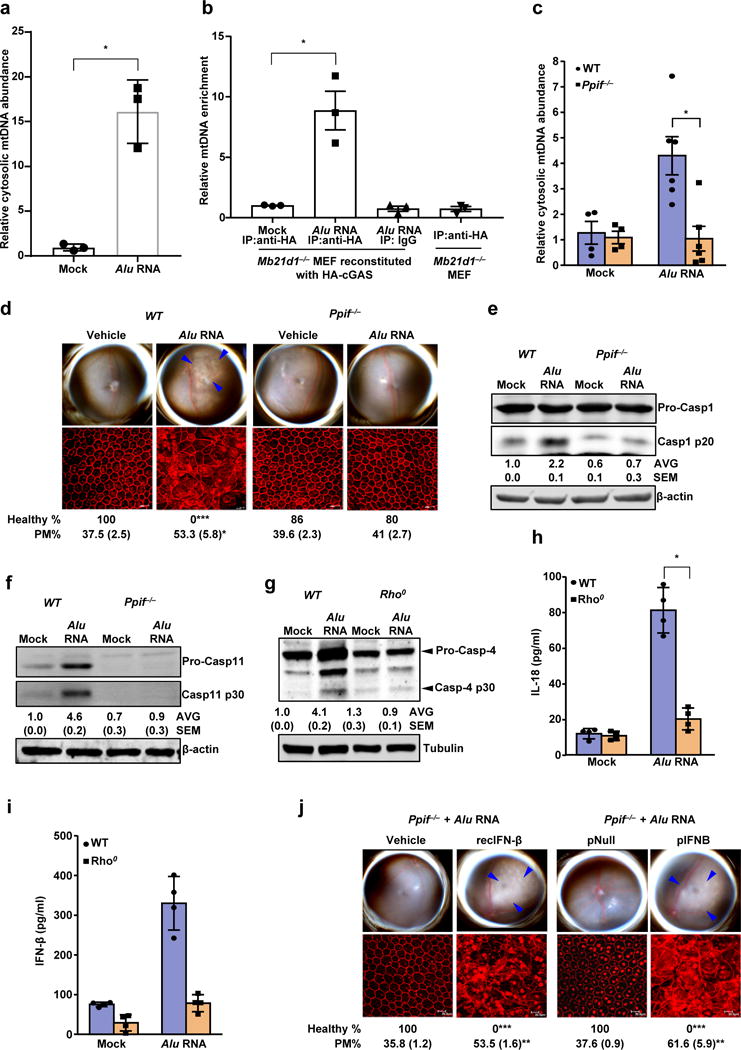

Both Alu RNA stimulation and DICER1 knockdown in human RPE cells resulted in an increased cytosolic abundance of mtDNA (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). To examine whether Alu RNA triggers engagement of mtDNA by cGAS, we performed a DNA-protein interaction pull down assay in Mb21d1−/− immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblasts reconstituted with HA-tagged cGAS (ref. 30). As these cells express HA-cGAS from a genomically integrated DNA sequence, they would be expected to express HA-cGAS at levels similar to those of endogenous cGAS expression. We observed enrichment of mtDNA in cGAS immunoprecipitates of Alu RNA-stimulated but not mock- or poly(I:C)-stimulated cells (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 12c), suggesting that mtDNA in the cytosol engages cGAS. As a positive control, transfected plasmid DNA in this assay was also enriched in the cGAS immunoprecipitate (Supplementary Fig. 12d). Additionally, subretinal delivery of mtDNA induced RPE degeneration in WT but not in Mb21d1−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 12e). Similarly, in cell culture studies, mtDNA-induced Ifnb mRNA levels were reduced in Mb21d1−/− compared to WT mouse RPE cells (Supplementary Fig. 12f). These data indicate that Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration is mediated via release of mtDNA into the cytosol, where it interacts with cGAS and induces interferon-β expression.

Figure 6. mtDNA in non-canonical inflammasome activation and RPE degeneration.

(a) Relative abundance of cytosolic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in human RPE cells mock-transfected or transfected with Alu RNA (Data presented are mean ± SEM; n = 3 independent experiments; *P = 0.0018, two-tailed t test). (b) Relative enrichment of mtDNA in cGAS immunoprecipitate in ChIP like pull-down assay. Mock or Alu RNA transfected, indicated mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) were analyzed upon HA-cGAS immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody or isotype conrol. Data presented are mean ± SEM; n = 3; *P = 0.008, two-tailed t test. (c) Relative abundance of cytosolic mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in WT and Ppif−/− mouse RPE cells mock transfected (n = 4 cell culture replicates) or transfected with Alu RNA (Data presented are mean ± SEM; n = 6 cell culture replicates; *P = 0.004, two-tailed t test). (d) Fundus photographs and immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts of WT (n = 6 eyes) and Ppif−/− (n = 12 eyes) mice subretinally injected with vehicle or Alu RNA. (e) Immunoblot for procaspase-1 (procasp-1) and p20 cleavage product of caspase-1 in WT and Ppif−/− mouse RPE cells mock transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. (f) Immunoblot for procaspase-11 (procasp-11) and p30 cleavage product of caspase-11 (Casp11 p30) in WT and Ppif−/− mouse RPE cells mock transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. (g) Immunoblot for procaspase-4 (procasp-4) and p30 cleavage product of caspase-4 (Casp4 p30) in WT and mitochondrial DNA deficient Rho0 ARPE19 human RPE cells mock-transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. (h, i) WT and mitochondrial DNA deficient Rho0 ARPE19 human RPE cells mock-transfected or transfected with Alu RNA. (h) IL-18 secretion; data presented are mean ± SD; n = 4 independent experiments; *P = 0.0001, two-tailed t test. (i) IFN- β secretion; data presented are mean ± SD; n = 4 independent experiments; *P = 0.004, two-tailed t test. (j) Fundus photographs and immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts of the Ppif−/− mice subretinally co-administered Alu RNA with recombinant IFN-β (n = 5 eyes) or vehicle control (n = 5 eyes); or IFN-β expression plasmid (pIFNB; n = 6 eyes) or empty vector control (pNull; n = 5 eyes). For all immunoblots, cropped gel image of bands of interest of representative immunoblots of three independent experiments and densitometric analysis (mean (SEM)) are shown. In d and j, binary (Healthy %) and morphometric (PM, polymegethism (mean (SEM)) quantification of RPE degeneration are shown (Fisher’s exact test for binary; two-tailed t test for morphometry; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). Loss of regular hexagonal cellular boundaries in ZO-1 stained flat mounts is indicative of degenerated RPE. The degenerated retinal area is outlined by blue arrowheads in the fundus images.

The mitochondrial permeability transition pore is required for Alu-driven mtDNA release

During conditions of cellular stress, opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) leads to mitochondrial swelling, rupture, and release of mitochondrial contents into the cytosol31. In cells lacking mitochondrial peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase F (PPIF, also known as cyclophilin D), a key enzyme involved in mPTP opening, mitochondria are resistant to swelling and the permeability transition32. Using the JC-1 and cobalt-calcein assays, we found that Alu RNA induced a reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), indicative of mPTP opening, in wild-type but not Ppif−/− mouse RPE cells, as determined using the potential-sensitive fluorochrome JC-1, and by quenching of the calcein signal (Supplementary Fig. 12g, h). In addition, cyclosporine A, which inhibits mPTP opening via binding to PPIF, blocked Alu RNA-induced mPTP opening in wild-type cells, but did not alter ΔΨm or calcein signal intensity in Ppif−/− cells (Supplementary Fig. 12g, h). Collectively, these findings suggest that Alu RNA induces Ppif-dependent mPTP opening in RPE cells.

Consistent with an effect of Alu RNA on mPTP opening, Alu RNA triggered mtDNA release into the cytosol in WT but not Ppif−/− mouse RPE cells (Fig. 6c). Ppif−/− mice were protected against Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration (Fig. 6d), confirming the in vivo importance of mPTP in Alu toxicity, and Alu RNA-induced activation of caspase-1 and caspase-11 were reduced in Ppif−/− mouse RPE cells (Fig. 6e, f). In human RPE cells lacking mitochondrial DNA (Rho0 ARPE19 cells), Alu RNA no longer activated caspase-4 (Fig. 6g) or induced secretion of IL-18 (Fig. 6h) or IFN-β (Fig. 6i). Furthermore, the resistance of Ppif−/− mice to Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration was overcome by recombinant IFN-β administration or IFN-β expression via subretinal plasmid transfection (Fig. 6j). Collectively these data support a model wherein mPTP-driven mitochondrial permeability mediates cytosolic release of mtDNA, which in turn promotes non-canonical inflammasome activation, via engagement of the cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS and its induction of IFN signaling.

Alu driven RPE toxicity does not require macrophages or microglia

We focused on the RPE as the cellular locus of inflammasome activation because we previously demonstrated that the various molecular abnormalities associated with geographic atrophy—DICER1 deficiency, Alu RNA accumulation, and increased abundance of NLRP3, PYCARD, cleaved caspase-1, and phosphorylated IRAK1/4—are localized to the RPE layer of human eyes with geographic atrophy4,5. Our current observations that elevated levels of cGAS, gasdermin D, cleaved caspase-4, and IFN-β are similarly localized to the RPE layer in diseased eyes buttresses the notion that this cell layer is the locus of molecular perturbations in the non-canonical inflammasome pathway.

However, recent reports that macrophages and microglia can be observed in the vicinity of pathology in human eyes with geographic atrophy33 raise the question of the functional involvement of these immune cells. Previously we demonstrated that RPE cell-specific ablation of Myd88, the adaptor critical for IL-18-induced RPE cell death in this system, is sufficient to prevent Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration in mice5. We also demonstrated using mouse chimeras that ablation of Myd88 in circulating bone marrow derived cells does not prevent Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration5. Nevertheless, given that macrophages and microglia are capable of inflammasome signaling, we studied their involvement more directly. We depleted macrophages using clodronate liposomes34 and depleted microglia by administering tamoxifen to Cx3cr1CreER ROSA-DTA mice35. Although these manipulations successfully depleted macrophages and microglia, respectively, neither type of depletion blocked Alu RNA- induced RPE degeneration in vivo, providing direct evidence that these two cell populations are dispensable for RPE toxicity in this system (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Although these two cell types are apparently not required by Alu RNA to elicit RPE degeneration in mice, they might have more subtle effects on disease pathology. Consistent with this possibility, we found that Alu RNA activated the non-canonical inflammasome in mouse BMDMs (Supplementary Fig. 14). Similarly to RPE cells, the ability of Alu RNA to induce caspase-1 activation was impaired in Casp11−/−, Mb21d1−/−, and Gsdmd−/− BMDMs, as compared to WT BMDMs (Supplementary Fig. 14). Collectively these findings suggest that cGAS-driven licensing of the non-canonical inflammasome by Alu RNA is not restricted to RPE cells.

DISCUSSION

Our data identify an unexpected role for the DNA sensor cGAS, the non-canonical caspase-4 inflammasome, and gasdermin D in mediating Alu RNA-induced RPE cell death, both in mice in vivo and in human cell culture. Coupled with observations that cGAS, interferon-β, caspase-4, and gasdermin D are at increased abundance in the RPE of human eyes with geographic atrophy as compared to control unaffected eyes, our findings point to the involvement of these proteins in the pathogenesis of this form of age-related macular degeneration.

cGAS was originally recognized as a sensor of exogenous and endogenous cytosolic DNA that mediates IRF3-driven interferon signaling, and previous studies demonstrated that the enzymatic activity of cGAS could not be activated by an RNA stimulus26. Nonetheless, cGAS has been reported to be critical for the antiviral response to multiple RNA viruses27; although the mechanistic underpinnings of this effect are not fully understood. In this context, our work provides a new view of how which endogenous RNAs can activate cGAS, and raise the possibility that cGAS-driven antiviral immunity involves Alu RNA, whose levels can be stimulated by viral infections36, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction.

Mitochondria have been increasingly implicated as gatekeepers of cell fate, with decisive roles in diverse cellular responses including apoptosis, autophagy, and innate immunity37. Mitochondria can facilitate the innate immune response to infection and injury via release of mitochondrial components that are recognized as DAMPs by the cell’s innate immune components. Of note, mtDNA can activate multiple arms of innate immunity, including the NLRP3 inflammasome, TLR9, and cGAS/STING-driven IFN signaling38,39. In particular, mtDNA can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome by directly interacting with NLRP3 (ref. 40) or by amplifying the response to an initial trigger, such as ATP or ROS41; and mtDNA can activate TLR9 on neutrophils, triggering systemic lung and liver inflammation42. In addition to engaging TLR9 and NLRP3 signaling, mtDNA has also recently been reported to be involved in the activation of cGAS signaling via cytosolic escape of mtDNA as a consequence of mitochondrial stress30. We previously demonstrated that TLR9 signaling is dispensable for Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration5, and that NLRP3 inflammasome priming is unaffected in mouse RPE cells lacking TLR9 (ref. 17). Instead, our findings show that Alu RNA-driven cytosolic mtDNA release leads to activation of both inflammasome and cGAS signaling pathways, highlighting the role of mitochondria as a signaling platform that integrates various cellular stress cues into an innate immune signaling response in autoimmune and chronic inflammatory diseases.

In addition to its role in responding to infections, cGAS has been implicated in mouse models of autoimmune diseases and mouse tumor models. Our findings expand the functional repertoire of this innate immune sensor to chronic degenerative diseases. Caspase-4/11-mediated activation of the non-canonical NLRP3 inflammasome has been implicated in gram-negative bacterial infection, sepsis, and antimicrobial defense at the mucosal surface10,12. To our knowledge, our report is the first example of caspase-4-driven non-canonical inflammasome activation in a non-infectious human disease. The involvement of caspase-4 and cGAS in other conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus and diabetes mellitus, wherein Alu RNA accumulation has been observed43,44, bears future investigation. Activation of caspase-4 has been observed in conditions of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress45. Given that several human diseases including Alzheimer’s disease and obesity driven-type 2 diabetes, both of which are driven by a hyperactive inflammasome, are associated with ER stress46,47, it would also be worth exploring whether DICER1 deficiency and/or Alu RNA-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cGAS- and caspase-4 dependent-inflammasome activation are linked to ER stress.

Gasdermin D has not, to our knowledge, been shown previously to be involved in a non-infectious human disease. Mechanistically, we found that gasdermin D lies downstream of caspase-11 activation and is required for Alu toxicity. The role of gasdermin D in this system appears not to be induction of pyroptosis, as it is in response to exogenous triggers such as intracellular LPS. Instead, gasdermin D supports Alu RNA-induced RPE cell apoptosis by promoting IL-18 secretion; notably, we did not observe cleavage of gasdermin into its p30 fragment, a cleavage which is required for its pyroptotic effect. Additional studies are required to dissect the mechanisms that disengage the pore-forming function of gasdermin D from the inflammasome-activating function, i.e., caspase-1 activation and IL-18 secretion. The effects of non-canonical inflammasome-dependent gasdermin D activation might be dictated by the activating trigger (e.g. exogenous versus host) or the cell type. For instance, the only other endogenous molecule known to activate caspase-11, oxPAPC, also does not induce pyroptosis, but instead triggers IL-1β release from dendritic cells11.

The mechanisms underlying regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by caspase-11/4 have been elusive. Previously we demonstrated that Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration and NLRP3 inflammasome activation depend on NF-κB and P2X7 (refs. 16,17). In our current work, we found that Alu RNA-induced caspase-11 activation was subdued in P2rx7−/− mouse RPE cells, suggesting that P2X7 is required for both caspase-1 and caspase-11 activation.48 Taken together, our observations suggest that Alu RNA-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activation requires both caspase-11/4 and P2X7 We also observed that Alu RNA induces oxPAPC synthesis, suggesting that Alu RNA might recruit other DAMPs to activate the non-canonical inflammasome and cause RPE cell toxicity. Earlier reports have implicated oxidized phospholipids in the pathophysiology of age-related macular degeneration49,50; future studies to unravel the underlying molecular mechanisms should be performed.

In recent years, numerous groups employing a variety of cell culture systems, animal models, and human donor eyes have reported an important role for the inflammasome in AMD5–8,51–54. Collectively these studies suggest that NLRP3 pathway is an important responder to a panoply of AMD-related molecular stressors and toxins in RPE cells, and there is great interest in inflammasome inhibition as a therapeutic for AMD16. Our identification of cGAS, interferon-β, caspase-4, and gasdermin D as critical mediators in inflammasome-driven RPE degeneration expands the array of therapeutic targets for AMD.

Although there is consensus that NLRP3 inflammasome activation is detrimental to RPE cell health and survival6–8, akin to the effects of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in other cell types55,56, there is controversy about the role of this pathway in neovascular AMD. It has been reported that IL-18, a cytokine produced by NLRP3 inflammasome activation, inhibits angiogenesis and that IL-18 neutralization augments angiogenesis in a laser injury model of choroidal neovascularization54. However, we and others were unable to replicate this anti-angiogenic effect of IL-18, and it was also demonstrated that the promotion of angiogenesis by an IL-18 antibody is due to an excipient in its preparation57. These conflicting data in neovascular AMD models do not, however, bear on the conclusion from our current data and work by others that inflammasome activation promotes RPE degeneration, a concept that provides a mechanistic rationale for testing inflammasome inhibition in geographic atrophy57,4,58,59,3,60

In summary, this study has uncovered a contribution of endogenous retroelement transcripts to disease via its induction of mitochondrial dysfunction and cGAS signaling, which drives interferon signaling and gasdermin D and NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Supplementary Fig. 15). Targeting of this pathway provides a new potential therapeutic approach for preserving RPE health in age-related macular degeneration and for treatment of a host of other inflammasome-driven diseases.

Methods

Mice

All animal experiments were approved by University of Kentucky’s or University of Virginia’s institutional review committees and were performed in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Visual Research. Both male and female mice between 6–10 weeks of age were used in the study. Wild-type C57BL/6J, Ppif−/−, P2rx7−/− and Stat2−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Gsdmd−/−, Pycard−/−, Casp11−/−, Casp1−/− Casp11129mt/129mt and Casp1−/− Casp11129mt/129mt Casp11Tg mice, described elsewhere12,19,61,62, were a generous gift from V.M Dixit (Genentech). Caspase-11 deficient mouse transgenically expressing human caspase-4 (Casp11−/− hCasp4Tg) were described earlier15. Wild type 129S6 mice (that carry an inactivating passenger mutation in caspase-11) were purchased from Taconic Biosciences. Ifnar1−/− mice were described earlier63 and were a generous gift from M. Aguet. Irf3−/− mice were a generous gift from T. Taniguchi via M. David64. Mb21d1−/− mice were generated by K.A. Fitzgerald (University of Massachusetts Medical School) on a C57BL/6 background using cryopreserved embryos obtained from the European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program (EUCOMM)65. Tmem173−/− mice were described earlier66. For all procedures, anesthesia was achieved by intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride (Ft. Dodge Animal Health) and 10 mg/kg xylazine (Phoenix Scientific), and pupils were dilated with topical 1% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine (Alcon Laboratories).

Fundus Photography

A TRC-50 IX camera (Topcon) linked to a digital imaging system (Sony) was used for fundus photographs of dilated mouse eyes.

Subretinal Injection

Subretinal injections (1 μl) in mice were performed using a Pico-Injector (PLI-100, Harvard Apparatus) or using a 35-gauge needle (Ito Co. Fuji, Japan). In vivo transfection of plasmids expressing Alu sequences (pAlu)67,68, empty control vector (pNull), Flag-cGAS (pFlag-cGAS), Flag-GFP, mouse mature IL-18 (pIL-18ss)57,69, wildtype mouse gasdermin D (pGSDMD-WT), the p30 cleavage incompetent mutant mouse gasdermin D ((pGSMDD-D276A)19, IFN-β (Origene Cat# MR226101), or mtDNA (10 ng) was achieved using 10% Neuroporter (Genlantis) as previously described4,5. In vitro transcribed Alu RNA (0.15–0.3 μg/μl), IFN-β neutralizing antibody (10 ng; Abcam Cat# ab24324), control isotype IgG, recombinant IL-18 (100 ng/μl, MBL Cat#B002-5), or IFN-β (500 mUnit/μl, PBL Cat#12410-1) were administered via subretinal injection4,5. Similarly, to knock down Dicer1, 1 μl of cholesterol conjugated siRNA (1 μg/μl) targeting mouse Dicer1 or scrambled control siRNAs were injected (Dicer1 siRNA sense- CUCUGUGAGAGUUGUCCdTdT; Control siRNA sense- UAAGGCUAUGAAGAGAUdTdT). The eye used for active versus control injection was chosen randomly.

Assessment of RPE Degeneration

Alu-mediated RPE degeneration was induced by exposing mice to Alu RNA, as previously described4,5,16,17,22. Seven days later, RPE health was assessed by fundus photography and immunofluorescence staining of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) on RPE flat mounts (whole mount of posterior eye cup containing RPE and choroid layers). Mouse RPE and choroid flat mounts were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde or 100% methanol, stained with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against mouse ZO-1 (1:100, Invitrogen) and visualized with Alexa-594 (Invitrogen). All images were obtained by microscopy (model SP-5, Leica; or Axio Observer Z1, Zeiss). Imaging was performed by an operator masked to the group assignments.

Quantification of RPE Degeneration

Binary Assignment

Healthy RPE cells form a polygonal tessellation with a principally hexagonal “honeycomb” formation. RPE degeneration was assessed as a disruption of this uniformity of this polygonal sheet. Thus, RPE health was assessed as the presence or absence of morphological disruption in RPE flat mounts by two independent raters who were masked to the group assignments. Both raters deemed 100% of images as gradeable. Inter-rater reliability was measured by agreement on assignments, Pearson coefficient of determination, and Fleiss κ. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine statistical significance between the fraction of healthy RPE sheets across groups.

Cellular Morphometry

Quantification of cellular morphometry for hexagonally packed cells was performed in semi-automated fashion by three masked graders by adapting our previous analysis of corneal endothelial cell density70. As RPE cells when viewed en face typically exhibit a principally hexagonal morphology similar to the corneal endothelium, they readily lend themselves to a similar analysis strategy. We obtained measures of cell size, polymegethism (coefficient of variation of cell size), and cell density. For this analysis, microscopy images of the RPE were captured and transmitted in deidentified fashion to the Doheny Image Reading & Research Lab (DIRRL). Images in which no cell borders could be seen were excluded from further analysis (1.8%). All images were rescaled to 304 × 446 pixels to permit importation into the Konan CellCheck software (Ver. 4.0.1), a commercial U.S. FDA-cleared software that has been used for registration clinical trials. RPE cell metrics were generated by three certified reading center graders in an independent, masked fashion. Inter-grader agreement was assessed for all three metrics by computing the multiple adjusted coefficient of determination. The previously published center method was utilized which entails the user selecting the center of each identifiable cell in the image71–74. Once the cell centers were defined, the software automatically generated the mean cell area, cell density, and polymegethism values. By default, the Konan software assumes a scaling factor of 124 pixels per 100 μm. Based on the dimensions of the original RPE image (1,024 × 1,024 pixels, 0.21 μm/pixel), the Konan provided values were converted to the actual physical values in μm.

RPE degeneration was quantified based on zonula occludens (ZO)-1-stained flat mount images using two strategies:

Binary assignment (healthy versus unhealthy)16,17,22 by two masked raters (inter-rater agreement = 98.6%; Pearson r2 = 0.95, P < 0.0001; Fleiss κ = 0.97, P < 0.0001).

Semi-automated cellular morphometry analysis by three masked raters adapting our prior analysis of the planar architecture of the corneal endothelium70, which resembles the RPE in its polygonal tessellation. Inter-rater agreement was high for all three metrics (multiple adjusted r2 = 0.99 (cell size), 0.72 (polymegethism, i.e., coefficient of variation of cell size), 0.99 (cell density)).

For eyes treated with Alu RNA, pAlu, and their respective controls, inter-rater agreement on binary assignment was 100%, and the fraction of eyes classified as healthy was 100% for both control groups versus 0% for Alu RNA or pAlu treatments (P < 0.0001, for both comparisons, Fisher exact test). All three morphometric features were significantly different between control treatments versus Alu RNA or pAlu treatments (P < 0.0001, t test; Supplementary Fig. 3). Given the similarity among all three features in differentiating healthy versus degenerated RPE cells, for all remaining groups, we quantified polymegethism, a prominent geometric feature of RPE cells in human geographic atrophy4,75–77.

Human Tissue

All studies on human tissue followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study of deidentified tissue from deceased individuals obtained from various eye banks in the United States was exempted from IRB review by the University of Virginia Institutional Review Board for Health Sciences Research in accordance with U.S. Health & Human Services human subjects regulations. Donor eyes from patients with geographic atrophy, an advanced form of AMD or age-matched patients without AMD were obtained from various eye banks. These diagnoses were confirmed by dilated ophthalmic examination prior to acquisition of the tissues or eyes or upon examination of the eye globes post mortem. Enucleated donor eyes isolated within six hours post mortem were immediately preserved in RNALater (ThermoFisher). The neural retina was removed and tissue comprising both macular RPE and choroidal tissue were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. For eyes with GA, RPE and choroidal tissue comprising both atrophic and marginal areas were collected.

Immunohistochemistry

Human eyes fixed in 2–4% paraformaldehyde were prepared for immunohistochemistry and stained as described earlier4,5. Briefly, immunohistochemical staining of fixed human eyes was performed with rabbit antibody against cGAS (0.1 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# HPA031700) or interferon β (0.2 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-20107) and mouse antibody against gasdermin D (1.5 μg/ml, Abcam, Cat# ab57785). Rabbit or mouse IgG controls were used to ascertain the specificity of the staining. Biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies, followed by incubation with VECTASTAIN® ABC reagent and development using Vector Blue (Vector Laboratories), were utilized to detect the bound primary antibody. Slides were washed in PBS, and then mounted in Vectamount (Vector Laboratories). All images were obtained using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA purified from cell using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s recommendations was DNase treated and reverse transcribed using the QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription kit (QIAGEN). The RT products (cDNA) were amplified by real-time quantitative PCR (Applied Biosystems 7900 HT Fast Real-Time PCR system) with Power SYBR green Master Mix. Relative gene expression was determined by the 2−ΔΔCt method using 18S rRNA or GAPDH as an internal control. The primers used were as follows: human IFNB1 (forward 5′-GCGACACTGTTCGTGTTGTC-3′ and reverse 5′-GCCTCCCATTCAATTGCCAC-3′), human CASP4 (forward 5′-TCTGAGGCTCTTTCCAACGC-3′ and reverse 5′-TTTGCCCAGGGATTCCAACA-3′), human DICER (forward 5′ AGAGGGAAAGAAAGACAACTGCT-3′ and reverse 5′-CATGCTGAGGGGTTGCAAAG-3′), human cGAS (forward 5′-ACGTGCTGTGAAAACAAAGAAG-3′ and reverse 5′-GTCCCACTGACTGTCTTGAGG-3′), human 18s rRNA (forward 5′-CGCAGCTAGGAATAATGGAATAGG-3′and reverse 5′-GCCTCAGTTCCGAAAACCAA-3′), human mitochondrial DNA (forward 5′-AGCCCACTGTAAAGCTAA-3′ and reverse 5′-TGGGTGATGAGGAATAGTGTA-3′), human GAPDH (forward 5′-TGGAAATCCCATCACCATCT-3′ and reverse 5′GTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGAT-3′), human GSDMD (forward 5′-GCTCCATGAGAGGCACCTG-3′ and reverse 5′-TTCTGTGTCTGCAGCACCTC-3′) mouse Ifnb1 (forward 5′-CGTGGGAGATGTCCTCAACT-3′ and reverse 5′-CCTGAAGATCTCTGCTCGGAC-3′), mouse Gapdh (forward 5′-CGACTTCAACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTCC-3′ and reverse: 5′- TGGGTGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTACTCCTT-3′), mouse 18s rRNA (forward 5′- TTCGTATTGCGCCGCTAGA-3′ and reverse 5′- CTTTCGCTCTGGTCCGTCTT-3′), mouse mitochondrial DNA (forward 5′-TTCGGAGCCTGAGCGGGAAT-3′ and reverse 5′-ATGCCTGCGGCTAGCACTGG-3′). human MIP1α (forward 5′-CATCACTTGCTGCTGACACG-3′ and reverse 5′-TGTGGAATCTGCCGGGAG-3′), human IL6 (forward 5′-GTAGCCGCCCCACACAGA-3′ and reverse 5′-CATGTCTCCTTTCTCAGGGCTG-3′), human IL8 (forward 5′-CACCGGAAGGAACCATCTCA-3′ and reverse 5′-AGAGCCACGGCCAGCTT-3′).

Mitochondrial DNA Preparation

Total DNA extracted from ARPE19 cells was used to PCR-amplify mtDNA segments as described earlier78. The purified mtDNA PCR products were subretinally delivered using 10% Neuroporter (Genlantis) as described above.

Western Blotting

Cell and tissue lysates prepared in RIPA buffer where homogenized by sonication. Protein concentration was determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Equal quantities of protein (10–50 μg) prepared in Laemmli buffer were resolved by SDS-PAGE on Novex® Tris-Glycine Gels (Invitrogen) and transferred onto Immobilon-FL PVDF membranes (Millipore). The transferred membranes were blocked in Odyssey® Blocking Buffer (PBS) or 5% nonfat dry skim milk for 1 h at RT and then incubated with primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. The immunoreactive bands were visualized using species specific secondary antibodies conjugated with IRDye® or HRP. Blot images were either captured using an Odyssey® imaging system or autoradiography film. The antibodies used were as follows; rabbit polyclonal anti-human and mouse caspase-1 antibodies (1:500, Biovision Cat# 3019-100; 1:1000, Invitrogen Cat#AHZ0082; 1:200 Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat#sc-514), rabbit anti-caspase-1 mAb (1:1000, Abcam Cat# ab108362), anti-human caspase-4 (1:200, Santa Cruz Cat#1229), anti-mouse caspase-11 (1:200, Novus Rat mAb 17D9 Cat#NB120-10454, or 1: 1000 Abcam Rabbit mAb Cat# ab180673 1:500), anti-STAT2 (1:500, Cell Signaling, Cat #72604), anti-pSTAT2 (1:250, Millipore Cat# 07-224), anti-human cGAS (1:1000, Cell Signaling Cat# 15102), anti-VDAC-1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Cat# #4661), anti-mouse IRF3 (1:500, Novus Biologicals, Cat#NBP1-78769), anti-phospho-IRF3 (1:500, Cell Signaling Cat# 4947S, Cat# 29047), anti-HA-tag (1:1000; Cell Signaling Cat# 2367), anti-α-tubulin mouse mAb (1:50000, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-β-actin mouse mAb (1:50000, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-vinculin (1:2000, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:500, Cell Signaling Cat#9661), anti-PARP (1:1000, Cell Signaling Cat#9542), anti-human GSDMD gasdermin D (1:500, Abcam Cat#ab57785) and anti-mouse gasdermin D mAb (1 μg/mL; a generous gift from V.M Dixit (Genentech). Immunoblotting for activated Caspase 1 in the supernatant was performed as described earlier19. Briefly, supernatants were collected and were briefly spun down to remove floating cells. Proteins from the cell-free supernatant were precipitated by adding sodium deoxycholate (0.15% final) followed by adding TCA (7.2% final) and incubating on ice for 30 min to overnight. Samples were spun down at 13000g for 30 mins and pellets were washed 2 times with ice-cold acetone. Precipitated proteins solubilized in 4X LDS Buffer with 2-mercaptoethanol were used for immunoblotting.

Cell Culture

Primary mouse and human RPE cells were isolated as previously described79. All cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 environment. Mouse RPE cells were cultured in Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 20% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin antibiotics at standard concentrations; primary human RPE cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. The human RPE cell line ARPE19 and ARPE19 cells lacking mitochondrial DNA (Rho0 ARPE19) were cultured as described earlier80. Rho0 ARPE19 cells were maintained at 37 °C in 24 mM Na2HCO3, 10% FBS, 50 μg/ml uridine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate in DMEM-F12 (Gibco, Cat#11320-033) containing pen/strep, Fungizone, and gentamicin. ARPE19 cells were maintained in DMEM-F12 containing pen/strep, Fungizone, and gentamicin. Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 20% L929 supernatants. Mb21d1−/− and HA-cGAS reconstituted Mb21d1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and antibiotics30.

Synthesis of in vitro transcribed Alu RNA

T7 promoter containing Alu expression plasmid was linearized and used for generating in vitro transcribed Alu RNA using AmpliScribe T7-Flash Transcription Kit (Epicenter) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting Alu RNA was DNase treated and purified using MEGAclear (Ambion), and its integrity was monitored by gel electrophoresis4,5.

Transfection

Alu expression plasmid (pAlu), empty vector control (pNull) in vitro transcribed Alu RNA were transfected into human and mouse RPE cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. mtDNA prepared as described below was transfected into mouse RPE cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

LPS transfection into BMDM

Approximately 2×106 BMDM cells were cultured overnight at 37 °C in a 60-mm dish. After 4–6 h of priming with 1 μg/ml Pam3CSK4 (Invivogen, Cat# tlrl-pms), the cells were transfected with LPS (5 μg/ml final concentration, Invivogen, Cat# tlrl-3pelps, ultrapure) with FugeneHD (Promega, Cat# E2311) using a standard transfection protocol. 16 h post-transfection, cell lysates were collected and analyzed.

Extraction of mitochondria-free cytosolic fractions

Human and mouse RPE cells were either mock treated or stimulated with Alu RNA. 24 h post Alu RNA transfection or 48 h post scrambled or DICER1 AS oligonucleotide transfection, the cells were harvested by trypsinization. 2×106 cells were used for collecting mitochondria-free cytosolic fractions using the Mitochondrial Isolation kit (Thermo Scientific Cat#89874). Briefly, cells were resuspended in 800 μl of Reagent A and were placed on ice for 2 min; the suspension was then dounce homogenized (10 strokes) to lyse the cells and to release nuclei, and then the suspension was incubated for 5 min on ice after addition of 10 μL Reagent B, with vortexing every minute. To this suspension 800 μl Mitochondria Isolation Reagent C was added and the resulting suspension was centrifuged at 700 g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet the nuclei. The supernatant containing the cytoplasmic fraction was centrifuged at 700 g for 10 min at 4 °C for a total of five times to completely remove nuclei or any unlysed cells. The resulting nuclei-free cytoplasmic fraction was centrifuged at 13,000g for 15 min at 4 °C to pellet the mitochondria. The resulting supernatant was further centrifuged at 13,000g for 15 min at 4 °C for an additional six times to remove all the mitochondria. The supernatant was then tested for an absence of mitochondria by immunoblotting for the mitochondrial marker protein VDAC and the cytosolic marker protein tubulin.

Reconstitution experiment

Mb21d1−/− mouse RPE cells were transfected with 2 μg cGAS expression plasmid26 or empty vector in a 60 mm dish at 70–80% confluency. 24 h post transfection, cells were plated on 6-well dishes. 24 h post plating, cells were transfected with Alu RNA (50 pmol) or were mock transfected using Lipofectamine 2000. 18 h post Alu RNA transfection, cells were collected for RNA extraction to examine induction of IFN-β mRNA. For Caspase-11 reconstitution. Casp11−/− mouse RPE cells were transduced with control or caspase-11 expressing lentiviral particles. The transduced cells were allowed to rest for three days and the cells were then plated in a 60 mm dish at 70–80% confluency. Control or Caspase-11 reconstituted Casp11−/− cells were mock treated or stimulated with Alu RNA as described above and activation of caspase-1 was assessed by western blotting. For the caspase-1 activity assay, Casp11−/− mouse RPE cells transfected with caspase-11 expression plasmid (pCasp11) or empty vector (pNull) were exposed to Alu RNA as described above and caspase-1 activity was assessed using the CaspaLux®1-E1D2 kit (OncoImmunin Cat # CPL1R1E-5). Quantification of the CaspaLux signal was performed by a blinded operator measuring the integrated density of fluorescent micrographs using Image J software (NIH) and normalizing to the number of cells.

Lentiviral transduction

Lentivirus particles were produced either by the University of Kentucky Viral Production Core facilities or in house. Lentivirus vector plasmids expressing scrambled sequences or shRNA sequences targeting human caspase-4 (Sigma Aldrich, #TRCN0000003511) and cGAS (Sigma Aldrich# TRCN0000150010) were purchased (MISSION®shRNA, Sigma-Aldrich) to produce lentiviral particles. Human RPE cells at passage 3 were incubated with lentiviral particles at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 overnight in regular growth media containing polybrene (4 μg/ml). On day 2, cells were washed, incubated in regular growth media and allowed to rest for 24 h. Lentivirus transduced cells were then cultured under puromycin (5 μg/ml) selection pressure for 5 days. Knock-down of the target proteins was determined by immunoblotting.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Secreted human and mouse interferon-β and IL-18 in the media were detected using ELISA kits (mouse IFN-β, R&D Systems Cat# 42400-1; mouse IL-18, R&D Systems Cat# 7625; human IFN-β, R&D Systems Cat# 41410; human IL-18, R&D systems Cat# DY318-05) according to the manufacturer′s instructions. Primary mouse cells were cultured as above. WT, Gsdmd−/−, Casp11−/−, or Mb21d1−/− mouse RPE cells were seeded at a density of 250,000 cells/well in a 12-well plate. When confluency reached 60–70%, cells were transfected with 20 pmol of in vitro transcribed Alu RNA or mock using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Media was collected to detect secreted cytokine content at 8 to 24 h post-transfection. For examination of the induction of IL-18 secretion by monosodium urate (MSU) crystals (Invivogen Cat# tlrl-msu), mouse RPE cells were primed with LPS (500 ng/ml) for 6 h and exposed to MSU (250 μg/ml) for 16 h, and media was collected to detect secreted cytokine.

cGAS-mtDNA interaction Immunoprecipitation assay

Immortalized cGAS−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) reconstituted with HA-tagged mouse cGAS (HA-cGAS) were described earlier30. The interaction between mtDNA and cGAS was monitored using Express Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit (Active Motif, ChIP-IT® Express, cat# 53008). Briefly mock, Alu RNA, poly I:C or plasmid DNA (pUC19) transfected HA-cGAS reconstituted cGAS−/− MEFs were fixed with 1% formaldehyde per the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were then lysed by sonication in the shearing buffer and centrifuged for 10 min at 18,000g in a 4 °C microfuge. The supernatant containing the cell lysate was collected and cGAS was immunoprecipitated from each sample using anti-HA tag antibody (Abcam, cat# ab9110). DNA in the IP was eluted, reverse crosslinked and purified using the Chromatin IP DNA Purification Kit (Active Motif, cat# 58002). Purified DNA was analyzed by qPCR using mouse mtDNA specific primer pairs. The fold enrichment of mtDNA in HA-cGAS immunoprcipitates in cells exposed to Alu RNA compared to mock transfected cells was calculated.

Quantification of PAPC and oxPAPC by LC-MS

Human RPE cells, mock-stimulated or stimulated with Alu RNA, were washed with cold PBS and trypsinized at 24 h post-stimulation. The cells were washed with cold PBS and 2×106 cells were used for lipid extraction by a modified Bligh-Dyer extraction method81. Briefly, the cell pellet was manually homogenized and then mixed in a glass tube with 700 μL HPLC-grade chloroform and 300 μL HPLC-grade Methanol (Sigma) supplemented with 0.01% butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT from Sigma) and 189 nmol of the internal standard, di-nonanoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DNPC from Avanti). 1 mL of HPLC-grade water was added and the mixture was vigorously vortexed for 60 sec. Next, the mixture was centrifuged (1,000 rpm for 10 min) to separate the fractions and the organic layer (bottom) was removed and placed into a fresh glass tube. 1 mL of chloroform was added to the aqueous fraction and the extraction was performed once more. The organic layer of the second extraction was combined with the first, and then dried down under nitrogen. Upon complete evaporation of the organic solvent, the lipids were suspended in 300 μL of Solvent A (69% water; 31% methanol; 10 mM ammonium acetate) and stored at −80 °C. The determination and quantification of oxidized phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine species was performed by liquid chromatography-linked ESI mass spectrometry, using an ABI Sciex 4000 QTrap. Separation of the phospholipids was achieved by loading samples onto a C8 column (Kinetex 5 μm, 150×4.6mm from Phenomenex). Elution of the phospholipids was achieved using a binary gradient with Solvent A (69% water; 31% methanol; 10 mM ammonium acetate) and Solvent B (50% methanol; 50% isopropanol; 10 mM ammonium acetate) as the mobile phases. Detection for phosphatidylcholine (PC) was conducted using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) in positive mode by identification of two transition states for each analyte. Quantification of each analyte was performed based on the peak area of the 184 m/z fragment ion for PC.

Determination of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening

Mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening in WT and Ppif−/− mouse RPE cells was monitored by the calcein-Co2+ technique82 using the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore Assay Kit (Biovision Inc Cat# K239-100). Mitochondrial membrane potential was evaluated with the JC-1 fluorochrome-based MITO-ID® Membrane Potential Cytotoxicity Kit (Enzo Cat# ENZ-51019-KP002)83. mPTP opening was inhibited by performing the above assays using cyclosporine A (10 μM)-containing media. The assay was performed in a 96-well microtiter plate according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Live Cell Imaging

2×104 human RPE cells were plated on each well of an 8-well chambered slide (Thermo Scientific Cat#155411). 18–24 h after plating, cells were transfected with 11.5 pmol in vitro transcribed Alu RNA (using Lipofectamine 2000) in culture medium supplemented with 2.5 mM CaCl2 and annexin-V 488 (1:200, Invitrogen V13241) and propidium iodide (1:1500, Invitrogen Cat#P3566). Immediately following transfection, annexin V, propidium iodide, and DIC signals were acquired using a Nikon A1R confocal microscope equipped with an automated stage. Images were captured at 3 min intervals for a total duration of 50 h. Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for the duration of the imaging study via a stage top incubator.

RPE flat mount annexin V/PI-staining

Mouse RPE/choroid flat mounts prepared in DMEM with 10% FBS were washed with binding buffer once and then incubated with Alexa Fluor™ 647 conjugated Annexin V (Invitrogen) for 15 min. The annexin V stained mouse RPE/choroid flat mounts were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, stained with propidium iodide (PI) containing RNase (Invitrogen) for 30 min and mounted using ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Microglia depletion

Microglia were depleted by administering tamoxifen to CX3CR1CreER; DTAflox mice which express Cre-ER under control of microglia specific CX3CR1 promoter and also contain flox-STOP-flox diphtheria toxin subunit α (DTA) gene cassette in the ROSA26 locus (DTAflox). Cx3cr1CreER; DTAflox mice were generated by breeding heterozygous Cx3cr1CreER mice with DTAflox mice (both mouse strains were generous gifts from Wai T. Wong and Lian Zhao, NIH). To deplete microglia, tamoxifen was administered to Cx3cr1CreER; DTAflox mice as described earlier35. Briefly, adult 2- to 3-month-old TG mice were administered with tamoxifen (TAM) dissolved in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich; 500 mg/kg dose of a 20 mg/ml solution) via oral gavage (Schedule: days −2, 0, 5, 10, and 15). On day 11, Alu RNA was delivered via subretinal injection. Alu RNA-induced RPE degeneration was assessed as described above. Microglial depletion was confirmed by staining retinal flat mounts for F4/80. Briefly retinal flat mounts were prepared and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 1 h, and stained with RPE conjugated F4/80 (Bio-Rad, Cat# MCA497PET) and fluorescein labeled Griffonia Simplicifolia Lectin isolectin B4 (IB4, Vector Laboratories, Cat# FL-1201). All images were obtained using Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope.

Macrophage depletion

Depletion of macrophages was achieved via administering clodronate liposomes, which eliminates macrophages, in wild-type mice34. Briefly, animals received 200 μl clodronate liposomes (Liposoma Cat# LIP-01) through the tail vein on days −2 and day 0. Alu RNA or vehicle control were subretinally injected immediately after the day 0 tail vein injection.

Statistical Analyses

Real-time qPCR and ELISA data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) were analyzed using Student t test. The binary readouts of RPE degeneration (i.e., presence or absence of RPE degeneration on fundus and ZO-1-stained flat mount images) were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Cell morphometry data were assessed using Student t test. P values < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. Sample sizes were selected based on power analysis α=5%; 1–β = 80%, such that we could detect a minimum of 50% change assuming a sample SD based on Bayesian inference. Outliers were assessed by Grubbs’ test. Based on this analysis no outliers were detected and no data were excluded. Fewer than 5% of subretinal injection recipient tissues were excluded based on predetermined exclusion criteria (hemorrhage and animal death due to anesthesia complications, etc.) relating to the technical challenges of this delicate procedure.

Supplementary Material

Editorial summary.

Degeneration of the retinal pigment epithelium is a hallmark of geographic atrophy, a type of age-related macular degeneration. Kerur et al. show that this degeneration results from a multi-step pathway in which mitochondrial dysfunction in RPE cells, triggered by accumulation of Alu RNA, leads to activation of the non-canonical inflammasome via a cGAS-STING-IRF3 signaling axis.

Acknowledgments