ABSTRACT

Sinorhizobium meliloti is a soil-dwelling alphaproteobacterium that engages in a nitrogen-fixing root nodule symbiosis with leguminous plants. Cell surface polysaccharides are important both for adapting to stresses in the soil and for the development of an effective symbiotic interaction. Among the polysaccharides characterized to date, the acidic exopolysaccharides I (EPS-I; succinoglycan) and II (EPS-II; galactoglucan) are particularly important for protection from abiotic stresses, biofilm formation, root colonization, and infection of plant roots. Previous genetic screens discovered mutants with impaired EPS production, allowing the delineation of EPS biosynthetic pathways. Here we report on a genetic screen to isolate mutants with mucoid colonial morphologies that suggest EPS overproduction. Screening with Tn5-110, which allows the recovery of both null and upregulation mutants, yielded 47 mucoid mutants, most of which overproduce EPS-I; among the 30 unique genes and intergenic regions identified, 14 have not been associated with EPS production previously. We identified a new protein-coding gene, emmD, which may be involved in the regulation of EPS-I production as part of the EmmABC three-component regulatory circuit. We also identified a mutant defective in EPS-I production, motility, and symbiosis, where Tn5-110 was not responsible for the mutant phenotypes; these phenotypes result from a missense mutation in rpoA corresponding to the domain of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit known to interact with transcription regulators.

IMPORTANCE The alphaproteobacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti converts dinitrogen to ammonium while inhabiting specialized plant organs termed root nodules. The transformation of S. meliloti from a free-living soil bacterium to a nitrogen-fixing plant symbiont is a complex developmental process requiring close interaction between the two partners. As the interface between the bacterium and its environment, the S. meliloti cell surface plays a critical role in adaptation to varied soil environments and in interaction with plant hosts. We isolated and characterized S. meliloti mutants with increased production of exopolysaccharides, key cell surface components. Our diverse set of mutants suggests roles for exopolysaccharide production in growth, metabolism, cell division, envelope homeostasis, biofilm formation, stress response, motility, and symbiosis.

KEYWORDS: Rhizobium, Sinorhizobium, cell envelope, exopolysaccharide, host-microbe, stress response, symbiosis

INTRODUCTION

Members of the alpha- and betaproteobacteria that engage in root and stem nodule symbioses with leguminous plants carry out about half of Earth's total biological nitrogen fixation, via conversion of dinitrogen to ammonia by nitrogenase (1). The soil alphaproteobacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti forms nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots of plants belonging to the genera Medicago, Melilotus, and Trigonella. Nodule formation is a complex process: the earliest steps involve signal exchange between the microbe and the plant and physically close interaction during bacterial colonization (2). In the initial signal exchange, bacteria respond to plant-secreted compounds by inducing expression of their nod genes, whose protein products synthesize Nod factor, which, in turn, triggers plant responses necessary for nodule formation (2). Bacteria invade through an inward-growing tube of the plant cell wall termed the infection thread (IT), while the plant initiates nodule morphogenesis. When an elongated IT reaches an infection-competent nodule cell, the bacteria are released into its cytoplasm via endocytosis. Here they differentiate into nitrogen-fixing bacteroids, supplying ammonium to the plant in exchange for carbon in the form of dicarboxylates (3). Bacteroid differentiation is regulated by low plant [O2] and by plant-synthesized, nodule-specific cysteine-rich (NCR) peptides (4).

The tripartite S. meliloti genome encodes functions that enable S. meliloti to cope with various soil conditions and with life within its host plant. As the interface between the bacterium and its environment, the S. meliloti cell envelope plays an important role. Like those of other Gram-negative bacteria, the S. meliloti envelope consists of inner and outer membranes, with a peptidoglycan layer in the periplasmic space between the two membranes. In addition to lipids and proteins, the S. meliloti cell envelope includes five symbiotically important cell surface polysaccharides: lipopolysaccharide, capsular polysaccharide, cyclic β-(1,2)-d-glucan, and acidic exopolysaccharides I and II (EPS-I and EPS-II) (2).

The best-studied S. meliloti cell surface polysaccharides are the acidic exopolysaccharides: EPS-I, also known as succinoglycan, and EPS-II (galactoglucan). EPS-I and EPS-II are synthesized by-products of the exo and wgx (formerly exp) genes, respectively (5). Genetic and functional studies indicate that EPS may help S. meliloti tolerate detergents, salt, acidic pH, heat, antimicrobial peptides, and reactive oxygen species (6–13); thus, EPS likely protects the bacteria from a variety of abiotic stresses in soil and the rhizosphere as well as stresses encountered during symbiosis, such as acidic pH and reactive oxygen species in early infection and perhaps NCR peptides in later stages of nodule development (4, 11, 14). EPS also appears to suppress host plant defense responses (15), and has been hypothesized to stimulate IT formation by mechanical stimulation—or by binding calcium ions and thereby altering free-calcium levels (16). EPSs, especially EPS-II, are important for S. meliloti biofilm formation (17, 18); an inverse correlation between EPS production and motility functions has been observed (19–22).

In addition to passive protective roles, EPS-I may be involved in plant signaling: in the Mesorhizobium loti-Lotus japonicus model symbiosis system, a Lotus EPS receptor has been identified, and Medicago truncatula encodes an orthologous protein (23). S. meliloti mutants lacking EPS are defective in IT initiation and elongation; hence, they elicit empty nodules (24). Because EPS-II can substitute for EPS-I only for S. meliloti infection of alfalfa, EPS-I is considered the more symbiotically important EPS (25). S. meliloti strain Rm1021 depends on EPS-I for alfalfa infection because it carries a native insertion element in expR and thus cannot activate the expression of EPS-II biosynthetic genes (see below) (25).

The regulation of EPS production is complex. In addition to responding to abiotic stresses and symbiotic inputs, EPS synthesis is regulated in response to levels of nutrients, for example, nitrogen and phosphate (26–28). Abundant evidence suggests that the RSI circuit (ExoR periplasmic regulator; membrane-localized ExoS histidine kinase; cytoplasmic ChvI response regulator) is the primary regulatory circuit controlling exo gene expression (18, 22, 29–36). ExoS activates its two-component partner ChvI by phosphorylation; ExoS activity is negatively modulated by interaction with ExoR (18, 31–33, 37). Other regulators, such as SyrA and SyrM, interact with the RSI circuit: SyrA regulates EPS-I abundance, and SyrA expression depends on the transcription regulator SyrM, which also activates nod gene expression via its activation of nodD3 expression (30, 38). Since the discovery of the RSI circuit, its roles have expanded to include motility, symbiosis, detergent and acid pH tolerance, cell membrane lipopolysaccharide composition, carbon metabolism, poly-3-hydroxybutrate (PHB) accumulation, growth, and regulation of EPS-II production (18, 22, 31, 33, 36, 39). The MucR transcription regulator positively affects exo gene expression but represses wgx gene expression (34, 40, 41). MucR also increases Nod factor production and decreases the expression of genes involved in nitrogen fixation and motility, suggesting that MucR controls multiple bacterial behaviors to enhance root nodule formation while repressing genes that are not required until later during symbiosis (40, 41). ExoX has been proposed to negatively affect EPS-I production by interacting with ExoY, which performs the first committed step in EPS-I biosynthesis, suggesting that EPS-I production can be regulated posttranslationally (42).

EPS-II is important for S. meliloti population behaviors such as biofilm formation, root colonization, and the movement of a cell population across a surface (17, 40, 43); quorum sensing plays a major role in regulating EPS-II production but only a minor role in EPS-I production (17). ExpR is required for S. meliloti quorum sensing and regulates the expression of many other genes, activating those for EPS-I and EPS-II biosynthesis and downregulating those involved in pilus synthesis and flagellar motility (19, 39, 40, 44–46).

We became interested in EPS regulatory circuits after finding that EPS-I production was coordinately regulated with nod gene expression via SyrM (30, 38) and that exo expression and the expression of motility genes were inversely correlated (21, 47). Previous screens identified genes involved in the regulation of EPS production (29, 42); we decided to take a genetic approach to identify additional mutants that overproduced EPS and then to assay their motility, cell envelope integrity, and symbiotic capability. Here we report the characterization of several dozen mucoid mutants, in which a diverse set of genes, about half of which have not been related to EPS production previously, are affected. Our study also points to previously unknown regulatory inputs for EPS-I production and demonstrates that motility gene expression does not always decrease when EPS-I production is enhanced.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A diverse group of Tn5-110 mucoid mutants.

We and others previously noted an inverse correlation between S. meliloti exopolysaccharide (EPS) production and motility (18, 20–22). To identify genes involved in coordinate control of EPS production and motility, we screened for S. meliloti Rm1021 mutants with decreased expression of motility genes on complex versus minimal media, conditions under which EPS-I production and motility gene expression differ (21) (see the text in the supplemental material). Because we could not detect any activity of motility gene uidA (encoding β-glucuronidase [GUS]) fusions on TY medium X-Gluc (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronic acid) indicator plates, we rescreened for mutants with increased uidA activity on M9 sucrose minimal medium (see the text in the supplemental material). This screen yielded three mutants: two with insertions in SMc02434, a conserved hypothetical gene, and one with an insertion between the flagellar biogenesis genes, rem and flgE. Due to technical difficulties associated with the first screen, we approached the same question by screening for mucoid mutants and subsequently assaying motility. Rm1021 lacks a functional ExpR regulator and cannot produce EPS-II under standard conditions; we took advantage of its relatively dry nature to screen for mucoid mutants (25). We mutagenized MB669 and MB671 (strain Rm1021 carrying uidA fusions to motility genes flaC and mcpU [PflaC::uidA and PmcpU::uidA], respectively) with Tn5-110. This mini-Tn5 carries constitutively active, outward-reading promoters of the trp leader peptide (Ptrp) on one end and neomycin phosphotransferase (Pnpt) on the other end (48). These outwardly directed promoters may minimize polar effects on downstream genes, and, when inserted upstream of a gene, may allow the isolation of mutants with upregulated gene expression. We screened approximately 34,000 mutants on four different media, one minimal and three complex media: M9 sucrose, TY, LB, or LB supplemented with cobalamin (vitamin B12) (see Materials and Methods). While wild-type (WT) S. meliloti can synthesize cobalamin, in the latter screen we used supplementation to isolate a specific class of mutants, those with deficiencies in cobalamin synthesis that would fail to grow on media without cobalamin supplementation. An S. meliloti bluB mutant, defective in cobalamin biosynthesis, has been shown previously to form mucoid colonies (49). We obtained 47 mutants that were mucoid upon retesting (∼0.14% of total colonies screened) and an additional 4 mutants with nonmucoid, pale colonies, distinct from the milky color of WT colonies (see Data Set S1 and Table S1 in the supplemental material). We used arbitrary PCR and DNA sequencing to determine the genomic location of each insertion (see Materials and Methods). The 51 mutants represent 30 unique genes and intergenic regions (IGRs).

We selected 34 mutants for further characterization (Table 1; also Data Set S1 in the supplemental material) and confirmed the genetic linkage of the mucoid phenotype to Tn5 by transducing Tn5 into S. meliloti Rm1021 (wild type) and MB669 (PflaC::uidA). The sole exception was the original mutant strain with Tn5-110 insertion 40 (designated OM40 below), in which Tn5 was not genetically linked to the mucoid phenotype. We named the mutants either according to the scheme MB8xx (for those derived from Rm1021) or MB9xx (for those derived from MB669), by their unique Tn5-110 insertion numbers (e.g., insertion 5), or, when applicable, by the name of the gene into which the insertion occurred and the number of the insertion (e.g., the emmA-5 mutant).

TABLE 1.

Summary of mutants isolated in plate screens for mucoid coloniesa

| Tn5 insertion or mutant genotypeb | Tn5 locationc (gene or IGR) | Description of gene product or IGR | Plate screend | Mucoid phenotypee | Calcofluor white phenotypef | Swim motilityg | flaC::uidA expressiong | DOC sensitivityh | Alfalfa symbiosisi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SMb20947 | ExoX, negative regulator of EPS production | LB | LB, M9 | Bright | + | + | WT | WT |

| 2 | SMc00166 | BluB, cob(II)yrinic acid a,c-diamide reductase | LB | LB, M9 | Bright | + | +/− | WT | Fix− |

| 5 | SMb21521 | EmmA, conserved protein | LB | LB, M9 | Bright | − | − | WT | WT |

| 7 | SMc04304 | CobW, cobalamin biosynthesis protein | LB | LB, M9 | Bright | + | + | WT | Fix− |

| 10 | SMc00716 | FtsX, cell division protein | LB | LB, M9 | Bright | +/− | +/− | High | Fix+/− |

| 12 | SMb21174 | PhoT, phosphate uptake, ABC transporter permease | LB | LB | Bright | + | + | WT | Fix− |

| 14 | SMc03782 | M23 peptidase family protein | LB | LB, M9 | Bright | +/− | − | High | Fix+, Nod+/− |

| 15 | SMc02584 | ActR, response regulator | LB | Not mucoid | WT | + | + | Moderate | WT |

| 17 | SMa0848 | Hypothetical protein, between nodD3 and syrM | M9 | LB, M9 | Bright | − | − | WT | WT |

| 18 | SMc02704 | CmdB, conserved protein | M9 | M9 | Bright | +/− | +/− | High | WT |

| 19 | SMa1660–1662 IGR | Intergenic region, 29 bp upstream of SMa1660 | M9 | LB, M9 | Bright | + | + | WT | WT |

| 20 | SMc02818 | Lysophospholipase-like protein | M9 | LB, M9 | Bright | − | +/− | High | WT |

| 21 | SMc01769 | LdtP, peptidoglycan-binding domain protein | M9 | M9 | WT | + | + | WT | WT |

| 22 | SMc03935 | Sel1-like tetratricopeptide repeat family protein | M9 | M9 | Bright | − | +/− | Moderate | WT |

| 27 | SMb20055–20056 IGR | Intergenic region, emmD expressed from Tn5 promoter | M9 | LB, M9 | Bright | + | + | WT | WT |

| 28 | SMc03900 | NdvA, β-1,2-glucan export ATP-binding protein | M9 | M9 | WT | − | +/− | WT | Fix−, Nod+/− |

| 29 | SMb20055–20056 IGR | Intergenic region, emmD expressed from Tn5 promoter | M9 | LB, M9 | Bright | + | + | WT | WT |

| 33 | SMb21519 | EmmB, histidine kinase | M9 | M9 | Bright | + | +/− | WT | WT |

| 38 | SMc00722 | Conserved transmembrane protein | M9 | LB, M9 | Bright | +/− | +/− | High | WT |

| 40 | SMc02867 (transductant, WT background) | SmeB, RND family efflux transporter (WT rpoA) | TY | Not mucoid | WT | + | + | High | WT |

| 40 | N/A; multiple mutations | smeB::Tn5 insertion 40; rpoA (L289R); htpG (L456I); SMb21268 (R150fs); flaC::uidA | TY | LB, M9 | Bright | − | − | High | Fix− |

| 41 | SMb20055–20056 IGR | Intergenic region, emmD expressed from Tn5 promoter | TY | LB, M9 | Bright | + | +/− | WT | WT |

| 42 | SMc00644 | Conserved hypothetical protein | LB | M9 | Bright | + | − | High | WT |

| 43 | SMb21519 | EmmB, histidine kinase | M9 | LB, M9 | Bright | +/− | − | WT | WT |

| 44 | SMc02705 | CmdC, conserved transmembrane protein | M9 | M9 | Bright | +/− | +/− | Moderate | WT |

| 45 | SMb21519 | EmmB, histidine kinase | TY | LB, M9 | Bright | +/− | − | WT | WT |

| 46 | SMb20946–20947 IGR | Intergenic region, exoY-exoX, 3 bp upstream of exoY | TY | LB, M9 | Bright | + | + | WT | Fix− |

| 47 | SMc00231 | GlmS, glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase | TY | LB, M9 | Bright | + | − | WT | WT |

| 48 | SMa0742–0744 IGR | Intergenic region, SMa0742-groESL2, 107 bp upstream of SMa0742 | TY | M9 | WT | − | − | WT | WT |

| 49 | SMa0846 | Transposase fragment, between nodD3 and syrM | TY | LB, M9 | Bright | +/− | +/− | WT | WT |

| 50 | SMb21177 | PhoC, phosphate uptake, ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | TY | LB | Bright | + | + | WT | Fix− |

| 51 | SMc02585 | ActS, histidine kinase | TY | Not mucoid | WT | + | + | Moderate | WT |

| 59 | SMb21316–21317 IGR | Intergenic region, wgdA-wggR, 56 bp upstream of wgdA | LB + B12 | LB, M9 | WT | + | + | WT | WT |

| 62 | SMc04303 | CobN, subunit of cobaltochelatase | LB + B12 | LB + B12, M9 | Bright | − | + | WT | Fix− |

| 63 | SMc04309 | CobQ, cobyric acid synthase | LB + B12 | LB + B12, M9 | Bright | − | + | WT | Fix−, Nod+/− |

| N/A | SMc01285 (transductant, rpoA T866G) | rpoA T866G strain without background mutations of OM40 | N/A | LB, M9 | Bright | − | − | Slight | Fix− |

| exoR95 | SMc02078 (control) | ExoR, negative regulator of EPS-I production | N/A | LB | Bright | − | − | WT | Fix−, Nod+/− |

| exoS96 | SMc04446 (control) | ExoS, histidine kinase | N/A | LB, M9 | Bright | − | − | WT | WT |

Additional information about these mutants is provided in Data Set S1 in the supplemental material. N/A, not applicable.

Each Tn5 insertion whose location was determined by sequencing has a unique number.

IGR, intergenic region.

Medium used for screening on agar plates.

Medium on which the strain appeared mucoid. Nonmucoid strains listed here were chosen for further characterization due to their pale colonial appearance. Strains with insertions in cobN or cobQ required supplementation with 2 μM cobalamin (B12).

WT, fluorescence similar to that of the WT; bright, fluorescence brighter than that of the WT.

+, ≥75% of the WT phenotype; +/−, 50 to 74% of the WT phenotype; −, <50% of the WT phenotype.

Sensitivity to 0.1% deoxycholate (DOC). High, >1,000-fold more sensitive than the WT; moderate, 10- to 1,000-fold more sensitive than the WT; slight, >2-fold and <10-fold more sensitive than the WT.

WT, nodules and shoots were indistinguishable from those on plants inoculated with WT Rm1021. Nod+/−, the number of nodules formed was <25% of the number formed by the WT. Fix+, the strain elicited pink nodules, indistinguishable from WT Rm1021 nodules, and plants had green, healthy shoots. Fix+/−, the strain elicited both pink and white nodules; plants with only white nodules had small, chlorotic shoots. Fix−, the strain elicited only white nodules, and plants had small, chlorotic shoots.

Phenotypic assays.

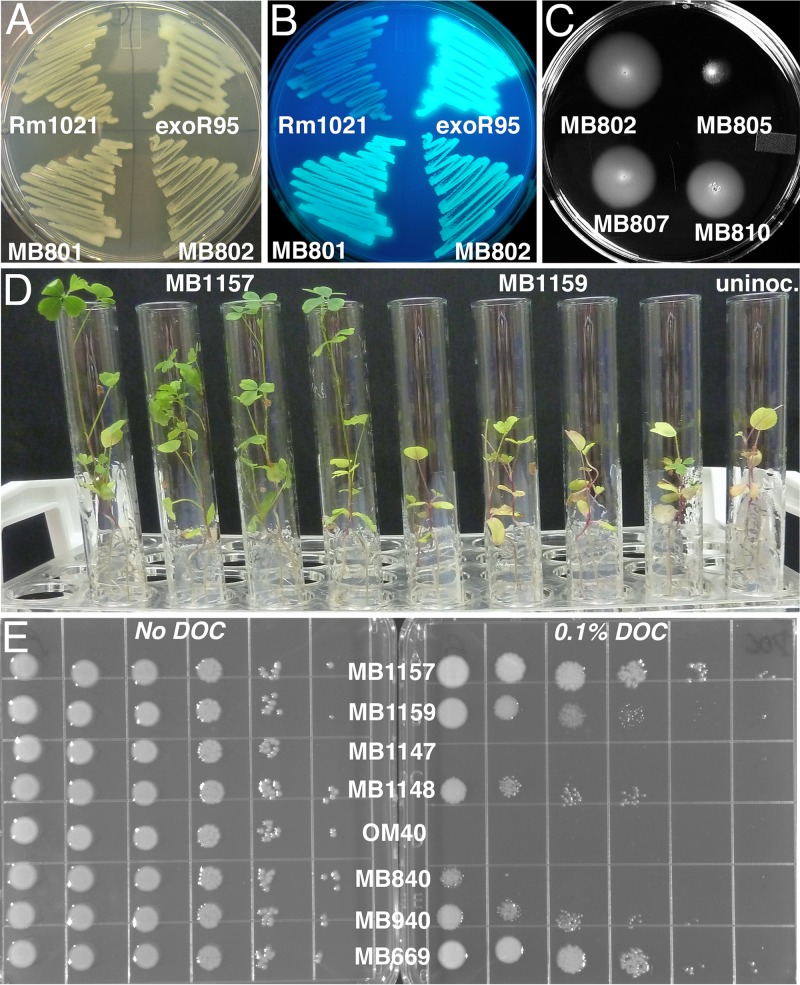

We subjected our mutants to a battery of phenotypic tests (Fig. 1): qualitative growth, mucoid phenotype on complex versus minimal medium, EPS-I abundance, determined by use of the fluorescent indicator calcofluor white, swimming motility, expression of the motility gene flaC, symbiosis, and deoxycholate (DOC) sensitivity (see Materials and Methods). We used the WT strain Rm1021 and the exoR95 and exoS96 strains as control strains. The exoR95 and exoS96 strains overproduce EPS-I, are nonmotile, and show decreased motility gene expression (18, 22, 29). Additionally, exoR95 mutants are symbiotically defective and fail to grow on minimal media (18, 29).

FIG 1.

Examples of results from phenotypic assays, described in Materials and Methods. (A) Mucoid phenotype on LB agar plates. (B) EPS-I fluorescence assay on LB agar plates with 0.02% calcofluor white. For panels A and B, exoX (MB801) and bluB (MB802) mutants were compared to WT strain Rm1021 and an EPS-I-overproducing exoR95::Tn5 control strain (29). Strains that fluoresce more brightly under UV light produce more EPS-I. (C) Swimming motility assays in TY soft agar for four different mucoid mutants: the exoX (MB802), emmA (MB805), cobW (MB807), and ftsX (MB810) mutants. (D) Medicago sativa nodulation assays. Each tube contains two plants, shown 5 weeks after inoculation. Four tubes inoculated with MB1157, a strain with WT rpoA, are shown on the left, followed by four tubes inoculated with MB1159, a strain carrying the rpoA T866G mutation. A single tube of uninoculated plants is shown on the far right. (E) Deoxycholate sensitivity assays. This example shows results obtained with various strains carrying WT rpoA or rpoA T866G. Diluted (10−1 to 10−6 [left to right]) strains were spotted onto LB agar without (left plate) or with (right plate) 0.1% DOC. Strain genotypes are as follows: MB1157, ΩpMB927; MB1159, ΩpMB927 rpoA; MB1147, ΩpMB927 rpoA htpG SMb21268 smeB PflaC::uidA; MB1148, ΩpMB927 htpG SMb21268 smeB PflaC::uidA; OM40, rpoA htpG SMb21268 smeB PflaC::uidA; MB840, smeB; MB940, smeB PflaC::uidA; MB669, WT control. (ΩpMB927 is a neutral marker for transducing the rpoA allele.)

The most common cause of mucoid colonial morphology in S. meliloti is overproduction of EPS-I (Fig. 1A) or EPS-II. Calcofluor white in LB can distinguish between EPS-I (which calcofluor white binds specifically, leading to UV-excited fluorescence [Fig. 1B]), and EPS-II. The product of the exoY gene is responsible for the first committed step of EPS-I biosynthesis; it thus serves as a control to ensure that the mucoid phenotype is due to increased EPS-I production. We introduced exoY210::Tn5-233 in order to test if EPS-I overproduction was responsible for the mucoid phenotype of those mutants that were mucoid on M9 sucrose medium but not on LB. All mucoid strains tested this way (except MB859 [see below]) became dry upon introduction of exoY210::Tn5, suggesting that their mucoid phenotypes result from EPS-I production (Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). It is not clear why the EPS-I production of some mutants is enhanced only on minimal plates; this could be due to various factors, such as nutrient availability (see the introduction) (50).

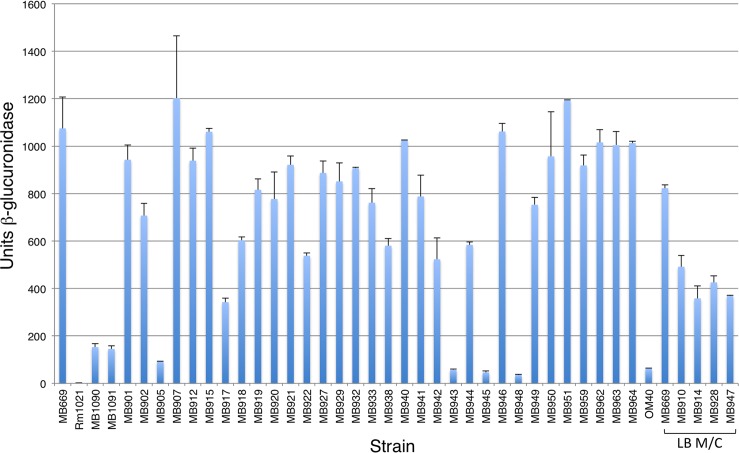

Since decreased motility often coincides with increased EPS production (18, 20–22), we tested our mucoid mutants for flagellum-mediated swimming by use of soft agar plates (Fig. 1C) and for motility gene expression by use of a genomic uidA fusion to the flaC promoter (Fig. 2; see Materials and Methods). flaC encodes FlaC flagellin, one of three secondary flagellins that make up the S. meliloti flagellar filament (51); it is coregulated with other members of the S. meliloti motility and chemotaxis regulon (21). Our mutants with decreased expression of the PflaC::uidA gene fusion usually showed a corresponding decrease in swim motility (Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, 0.64), linking flaC gene expression to function. Because an inverse correlation between EPS production and motility was observed under some conditions previously, we expected that most of our mucoid mutant strains would show reduced motility. Much to our surprise, ∼60% of our mucoid mutants were motile (swim diameter, ≥75% that of the WT). Only four mutants showed both swim diameters and PflaC::uidA expression levels equivalent to <50% those of control strains (Table 1; also Data Set S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 2.

Expression of PflaC::uidA in mutant strains relative to that in a WT control (MB669). β-Glucuronidase activity was assayed for Tn5-110-containing strains MB901 to MB964 and OM40, as well as for the nonmotile exoR95::Tn5 (MB1090) and exoS96::Tn5 (MB1091) control strains. Strains were usually grown in TY medium; those that grew poorly in TY medium were grown in LB supplemented with 2.5 mM MgSO4 and 2.5 mM CaCl2 (LB M/C). Assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods, with all strains tested in duplicate at the same time. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Nitrogen-fixing nodules are pink, due to the presence of plant-synthesized, oxygen-sequestering leghemoglobin (3). Several S. meliloti EPS-I-overproducing mutants were previously reported to have symbiotic defects (29, 49, 52); we therefore tested our mutants on alfalfa, assaying for nodule and plant appearance and for the number of nodules (see Materials and Methods). Bacterial strains inhabiting stunted, chlorotic plants with white nodules were judged to be ineffective (i.e., non-nitrogen fixing) (Fig. 1D). Overall, 11 mutants showed symbiotic defects (Table 1; also Data Set S1 in the supplemental material).

Because several previously characterized S. meliloti EPS-I-overproducing mutants had envelope defects (8, 52, 53), we assayed the envelope integrity of our mucoid mutants by testing their sensitivities to 0.1% and 0.2% DOC (Fig. 1E; see also Materials and Methods), a bile salt that disrupts membranes, denatures proteins, and causes disulfide stress. DOC is commonly used to screen for cell envelope defects in S. meliloti (8, 52, 54). As a control, we assayed an lpsB mutant that is defective in the synthesis of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) core oligosaccharide and highly sensitive to membrane-disrupting agents such as DOC (55). Eleven mutants were ≥10 times more sensitive to 0.1% DOC than the WT (Table 1; also Data Set S1 in the supplemental material).

Mutants in which biosynthesis or the export of cell surface polysaccharides is affected.

We obtained four mutants whose phenotype we infer is due to a Tn5-110 insertion causing ectopic expression of EPS biosynthesis proteins or their regulators, as well as another mutant in which the elimination of cyclic β-(1,2)-glucan (CbG) export stimulates EPS-I production (Table 1).

Mutant 59, with an insertion in the IGR between wgdAB and wggR (MB859), remained mucoid even when EPS-I biosynthesis was abolished due to mutation of exoY. We propose that increased transcription from Tn5-110 outward-reading promoters stimulates EPS-II production by increasing levels of WggR, a transcription activator of EPS-II biosynthesis genes, and of WgdA and WgdB, proteins required for EPS-II production (56).

IGR mutants that increase EPS-I production included two (mutants 17 and 49) with insertions between divergently transcribed genes for SyrM and NodD3, transcription activators known to enhance EPS-I production by stimulating syrA expression, which, in turn, increases the activity of the RSI circuit (30, 38).

Another IGR mutant, the exoY-exoX-IGR-46 mutant, produced abundant amounts of EPS-I yet failed to establish an effective nitrogen-fixing symbiosis with alfalfa. The Tn5-110 insertion in mutant 46 is located 3 bp upstream of the exoY translation start codon and downstream of the putative exoY operon promoters (34, 57): transcription of key EPS-I biosynthesis genes presumably occurs from Pnpt of Tn5. Misregulation of exoY in mutant 46 is likely deleterious to symbiosis because of decreased in planta exoY transcription from Pnpt.

Lastly, one mutant presumably defective in CbG production, the ndvA-28 mutant, overproduced EPS-I, failed to grow in liquid TY medium and showed poor motility on TY, but not LB, soft agar plates. CbG is critical for adaptation to hypo-osmotic conditions and invasion of plant roots; mutants lacking CbG form “empty” nodules, devoid of bacteria (58). Mucoid colonies and increased EPS abundance have been reported previously for some ndvA mutants (59). The mechanism behind these EPS phenotypes is unclear but may be related to their inability to export CbG and the osmolarity of the growth medium.

Mutants with compromised cell envelope function.

Mutants 10, 14, 18, 20, 38, 40, and 42 were extremely sensitive to DOC, and mutants 15, 22, 44, and 51 were moderately sensitive to DOC, indicating possible cell envelope defects (Table 1). The DOC sensitivity of our SMc00644-42 mutant is consistent with previous results (54); the earlier mutant also showed a slight sensitivity to polymyxin B, minor alterations in its smooth LPS profile, less-competitive nodulation on alfalfa, and reduced nitrogen fixation on M. truncatula (54). While the function of SMc00644 is unknown, PSort (60) predicts its cytoplasmic location, and database searches do not find it beyond the Rhizobiales.

Mutant SMc00722-38 has its insertion in mhrA. A recent study also showed DOC sensitivity when mhrA was mutated; furthermore, those mutants overproduced EPS-I, made more biofilm than the wild type, and were defective in maintaining intracellular Mg2+ levels, suggesting that MhrA plays a role in magnesium homeostasis (61).

The SMc02818-20 mutant grew more slowly than the WT, especially on LB and TY agar plates. SMc02818 is predicted to be cytoplasmic and shows similarity to lipases and esterases. A predicted cytoplasmic membrane protein of unknown function (SMc02817) is encoded downstream of SMc02818: Tn5-110 insertion 20 may also affect its transcription.

Mutants with insertions in the cmdABCD operon (cmdB-18 and cmdC-44) showed DOC sensitivity similar to that seen in Rhizobium leguminosarum cmd mutants (62); our S. meliloti mutants differ from those in R. leguminosarum in that our mutants grew normally on complex media. The functions of the conserved Cmd proteins are not known, but the DOC sensitivity and the pleiotropic phenotypes of the R. leguminosarum mutants suggest a role in cell envelope physiology. Overproduction of EPS was not reported for the R. leguminosarum mutants; perhaps EPS-I overproduction by our S. meliloti cmd mutants compensates for the loss of CmdB or CmdC function, allowing their better growth. ChvI/ChvG (ExoS) appears to regulate cmdABCD expression in R. leguminosarum (62). S. meliloti cmdABCD was not identified previously as a direct ChvI target (32, 63), but we observed enhanced expression of cmd genes in two strains with apparently increased activity of the ChvI circuit (18, 30).

While the SMc03935-22 mutant shows reduced motility, it shows no obvious growth defects otherwise. The SMc03935 protein contains six tetratricopeptide repeats, suggesting that it likely interacts with other proteins.

Mutant OM40, which has Tn5 inserted in smeB, as well as several spontaneous mutations, was also quite sensitive to DOC. Genetic dissection showed that the smeB insertion (Tn5-110 insertion 40) was primarily responsible for its DOC sensitivity (Fig. 1E) but not for any of its other tested phenotypes (Fig. 1; see below). smeB encodes the resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) inner membrane transporter component of the SmeAB multidrug efflux pump (64); an smeAB deletion mutant (ΔSMc02868–SMc02867) was sensitive to antibiotics, detergents, dyes, and plant compounds; it also competed poorly with the WT for nodulation (64).

We characterized our nonmucoid actR-15 and actS-51 mutants because they had a pale colonial phenotype. Their DOC sensitivity suggests that the S. meliloti two-component ActR (response regulator)/ActS (histidine kinase) system influences cell envelope function. Characterized in S. meliloti and the closely related species Sinorhizobium medicae, ActRS is postulated to play roles in acid tolerance, oxidative stress response, regulation of microaerobic respiration, nitrate assimilation, CO2 fixation, and hydantoin utilization (65, 66).

Peptidoglycan synthesis and remodeling.

The peptidoglycan layer of Gram-negative bacteria is the primary cell shape determinant that allows cells to withstand turgor pressure and maintain envelope integrity; it is remodeled during cell growth and division. Peptidoglycan metabolism in Rhizobiales is of interest because this group is unique among the alphaproteobacteria in growing primarily from one cell pole and because peptidoglycan may be an important determinant in the interactions of rhizobia with their eukaryotic hosts (67). We isolated four mutants with insertions (insertions 10, 14, 21, and 47) in genes whose predicted functions suggest roles in peptidoglycan synthesis and remodeling.

Insertion 47 is in glmS, whose product catalyzes the formation of glucosamine-6-phosphate from fructose-6-phosphate and glutamine. Glucosamine-6-phosphate is an important enzyme in the pathway leading to the peptidoglycan precursor UDP-N-acetyl-α-d-glucosamine and is also a precursor in Nod factor synthesis. S. meliloti also encodes a GlmS paralog, NodM. The amino acid sequences of GlmS and NodM are 99.7% identical, but they show differential expression: glmS is expressed under a wide range of growth conditions, while nodM is induced by root-secreted flavonoids and NodD (68). The glmS-47 mutant grew more poorly than the WT in complex media and required supplementation with glucosamine (200 μg ml−1) for growth on M9 sucrose medium unless 3 μM luteolin was added to the M9 medium to induce nodM expression. In S. meliloti strain Rm41, nodM mutants showed delayed nodulation kinetics on alfalfa (68); in a closely related species, Rhizobium leguminosarum, glmS was required for nitrogen fixation, suggesting that nodM cannot substitute for glmS in planta (69). We tested single and double nodM and glmS mutants on alfalfa: the double mutant (MB706) failed to form nodules (Nod− phenotype), whereas the single mutants (MB704, MB711, and MB847) formed nitrogen-fixing nodules normally on alfalfa. Thus, nodM expression in S. meliloti nodules is sufficient to support nitrogen fixation.

EPS-I overproduction was the only obvious mutant phenotype seen in our ldtP-21 mutant. ldtP encodes a conserved hypothetical protein with similarity to l,d-transpeptidases that cross-link peptidoglycan. An ldtP mutant was previously shown to be sensitive to osmotic stress and to have a shortened cell phenotype; a mucoid phenotype was not reported (70).

The SMc03782-14 and ftsX-10 strains were the most severely compromised mutants isolated in our screen. Both were extremely mucoid, grew poorly, and did not survive long-term storage as glycerol-containing freezer stocks (at −80°C). SMc03782 protein has a predicted signal peptide and carboxy-terminal LytM hydrolase-like domain. However, not all LytM domain proteins have hydrolase activity: Escherichia coli EnvC facilitates cell division by activating amidases that, in turn, hydrolyze peptidoglycan (71). SMc03782 is likely cotranscribed with the downstream gene ctpA (encoding a putative carboxy-terminal protease). The growth phenotype of our SMc03782 mutant agrees with previous data showing impaired growth for an SMc03782 mutant under all conditions tested (72). While the downstream gene ctpA may be expressed from Ptrp of the upstream Tn5, we cannot rule out the possibility that the growth defects of the SMc03782-14 mutant are due to polar effects of the insertion on the downstream gene ctpA. R. leguminosarum ctpA mutants have growth and cell envelope defects (73).

S. meliloti ftsX is downstream of, and likely cotranscribed with, ftsE; Tn5 in the ftsX-10 mutant is inserted after nucleotide (nt) 801 of the ftsX open reading frame (ORF). We tried to make another ftsX mutant by inserting a nonreplicative plasmid (pMJ6) into ftsX at nt 565. Conjugations with this plasmid yielded extremely tiny colonies, which failed to grow upon restreaking. Constitutive expression of ftsX from a broad-host-range plasmid allowed the creation of a plasmid insertion mutant (MB702/pMJ10) and also complemented the mucoid and poor-growth phenotypes of the mutant with insertion 10 (in ftsX), from which we conclude that mutant 10 may have partial FtsX function. In E. coli, FtsE and FtsX form a complex essential for cell division under conditions of low osmolarity (74); this complex participates in recruiting divisome proteins to the Z-ring, facilitates midcell constriction by hydrolyzing ATP, and regulates cell wall hydrolysis at the division site by regulating EnvC-mediated activation of peptidoglycan amidases (74). Given that the SMc03782-14 and ftsX-10 mutants share similar phenotypes, it is tempting to speculate that the SMc03782 and FtsX proteins are involved in the same pathway, perhaps even regulating cell division in a manner analogous to that of E. coli EnvC and FtsX. However, it is also possible that the SMc03782 and ftsX mutations independently create similar problems that cause EPS-I overproduction and poor growth.

We postulate that increased production of EPS-I in these mutants is part of a peptidoglycan stress response. Such a response has not been characterized in rhizobia previously, but in response to peptidoglycan-targeting antibiotics, E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa increase production of the exopolysaccharides colanic acid and alginate, respectively (75, 76). If peptidoglycan stress triggers EPS-I production in S. meliloti, it could explain the EPS-I phenotypes of the cbrA and podJ cell division mutants (53, 77).

Cobalamin biosynthesis mutants.

Four mutants with insertions in cobalamin (vitamin B12) biosynthesis genes overproduced EPS-I and failed to form effective symbioses with alfalfa (Table 1). The cobN-62 and cobQ-63 mutants failed to grow on complex or minimal media unless supplemented with vitamin B12, whereas the cobW-7 and bluB-2 mutants grew in complex but not liquid minimal media. cobN and cobW encode an aerobic cobalt chelatase and a cobalt biosynthesis protein of unknown function, respectively, and are likely cotranscribed as members of the cobPWNO operon, whose expression is regulated by a B12 riboswitch. cobQ encodes cobyric acid synthase, which catalyzes a later step in the pathway than CobN and BluB. bluB encodes the enzyme that synthesizes the lower ligand of B12 and is also regulated by a B12 riboswitch (49, 78). BluB is required for effective symbiosis, because S. meliloti ribonucleotide reductase (NrdJ), which performs a rate-limiting step in DNA replication, and methionine synthase (MetH) are cobalamin-dependent enzymes essential for symbiosis (79). While other cobalamin biosynthesis mutants, such as our cobN, cobQ, and cobW mutants, were not specifically tested, we assume that they are affected similarly to the previously characterized bluB mutants (49, 79). How defects in cobalamin biosynthesis result in EPS-I overproduction remains unknown (49).

Phosphate transport mutants overproduce both EPS-I and EPS-II.

Mutants that were mucoid on LB medium were also mucoid on M9 sucrose minimal medium, with two exceptions: the phoT-12 (MB812) and phoC-50 (MB850) mutants were mucoid only on LB. phoT and phoC encode permease and ATP-binding subunits, respectively, of a phosphate and phosphonate ABC transporter (80). PhoCDET is one of three phosphate transport systems in S. meliloti. In a previous study, phoCDET mutants were mucoid on glutamate-yeast extract-mannitol (GYM) agar plates (81). Because S. meliloti Rm1021 contains a mutation in pstC (encoding a subunit of the high-affinity, high-velocity phosphate transporter PstSCAB) (82), and because the low-affinity OrfA-Pit phosphate transporter is repressed in phoCDET mutants (83), phoCDET mutants grown on GYM plates (0.5 mM Pi) may be limited for phosphate and therefore overproduce EPS-II (81). Like previous phoCDET mutants, our phoT-12 and phoC-50 mutants were mucoid on GYM agar plates unless supplemented with the utilizable phosphorous source aminoethylphosphonate at 2 mM (81). M9 sucrose minimal medium has more phosphate than LB medium (63 mM versus ∼5 mM), perhaps explaining why the phoT-12 and phoC-50 mutants are not mucoid on M9 medium. Oddly, our mutants were bright on LB plates with calcofluor white, suggesting that they may also overproduce EPS-I. To further explore this finding, we introduced the phoT-12 and phoC-50 Tn5 insertions into a pstC-repaired derivative of Rm1021; this abolished the GYM mucoid phenotype. On LB plates with calcofluor white, these strains were brighter than Rm1021 and similar in brightness to their pstC+ parent, suggesting that while EPS-I production appears to be increased in phoC and phoT mutants, baseline EPS-I production is lower in Rm1021 because of the defective pstC allele. We confirmed that EPS-I is responsible for the calcofluor bright phenotype of the phoT-12 and phoC-50 mutants by introducing an exoY::Tn5-233 mutation into each; this eliminated calcofluor white fluorescence. Why EPS-I production increases in Rm1021 pho strains is unknown; perhaps phosphate limitation stimulates ChvI or PhoB to activate the transcription of EPS-I (exo) biosynthesis genes (27, 28, 32, 34, 82). phoC and phoT are not required for nitrogen fixation in an otherwise WT strain (82): our phoT-12 and phoC-50 mutants likely show a Fix− phenotype because the Rm1021 genome encodes a defective PstC protein.

Most of the defects of OM40 are caused by a missense mutation in rpoA.

As mentioned above, the Tn5-110 insertion in smeB in our OM40 mutant was not transductionally linked to the mucoid phenotype. OM40 was especially interesting to us due to its severe motility and symbiotic defects, despite its normal growth in culture; we therefore performed whole-genome sequencing to identify potential spontaneous mutations responsible for these phenotypes (see Materials and Methods). In addition to the known Tn5-110 insertion in smeB and the PflaC-uidA plasmid insertion, we identified three single nucleotide variants not in the Rm1021 parent strain: (i) in SMb21268, deletion of nt 441 of the ORF (Arg150 frameshift), (ii) in htpG (SMb21183), a C→A substitution (Leu456Ile) at nt 1366, and (iii) in rpoA (SMc01285), a T→G substitution (Leu289Arg) at nt 866. SMb21268 encodes an ABC transporter protein; htpG encodes an Hsp90 family heat shock protein; and rpoA encodes the alpha subunits of RNA polymerase (RNAP). We determined which variants were responsible for the phenotypes by introducing a Hy resistance marker near each variant location and then using transduction to swap variants with their WT alleles and vice versa (see Materials and Methods). For most phenotypes, the results were clear: strains carrying the rpoA Leu289Arg variant overproduced EPS-I on LB and M9 sucrose, had severe motility defects, similar in degree to those of the exoR95::Tn5 and exoS96::Tn5 mutants, and failed to establish effective symbiosis with alfalfa, generating small, white nodules and chlorotic, nitrogen-deprived plants (Fig. 1D and 2; Table 1; also Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). In contrast, none of these phenotypes correlated with the presence of the SMb21268 and htpG variants. The DOC phenotype was more complicated; our assays showed that the rpoA Leu289Arg variant may confer slight sensitivity to DOC (Fig. 1E, compare MB1157 to MB1159), while the Tn5-110 insertion in smeB confers high sensitivity (Fig. 1E, compare MB1157 to MB840). The presence of the PflaC::uidA fusion appeared to improve the growth of strains carrying the smeB-40 insertion, but only if rpoA was WT (Fig. 1E, compare MB840 to MB1148 and MB940). We have no explanation for this unexpected DOC result.

How does a Leu289Arg change in the C-terminal domain of each alpha subunit (αCTD) of RNAP confer specific EPS-I, motility, and symbiosis phenotypes? S. meliloti RpoA shares 51% identity with the well-studied E. coli RpoA and can substitute for E. coli RpoA both in vivo and in vitro (84). The alpha-subunit N-terminal domains (αNTDs) bind the β and β′ subunits of RNAP (which together form the cleft of the active site); the αCTDs interact with UP element promoter motifs (85). UP elements lie just upstream of the conserved −35 to −10 promoter motif recognized by the σ factor of RNAP (85). Transcription initiation from promoters with suboptimal motifs often necessitates the binding of transcription activators to upstream sequences; these activators interact with the αCTDs to recruit RNAP to the promoter (85). Alternatively, a regulator may interact with the αCTDs of RNAP before the binding of the activator-RNAP complex to DNA (85) or may repress specific transcription in an αCTD-dependent manner by occluding an UP element (85). Missense mutations in the αCTD that affect interactions with myriad transcription regulators have been identified (85). The S. meliloti RpoA Leu289 residue corresponds to E. coli RpoA Leu290, the site where mutation to His affected regulator-RNAP interactions (86). Our S. meliloti RpoA mutation substitutes the bulkier, basic Arg for the neutral Leu, in agreement with the idea that mutation results in an altered interaction with one or more as yet unidentified transcription regulators. Experiments such as global transcription comparing the WT with the rpoA T866→G mutant may provide hints as to which regulator interactions are affected, as was recently shown for Bacillus subtilis, where use of a truncated αCTD mutant identified candidate αCTD-interacting regulators on a global scale (87).

emmA and emmB mutants overproduce EPS-I and have motility defects.

Our genetic screen yielded the emmA-5 mutant, which formed calcofluor bright, mucoid colonies and exhibited severe motility defects, as well as mutants with insertions 33, 43, and 45 in the nearby emmB gene. Morris and González (8) have published a comprehensive study of the emmABC genes, including emm Tn5 mutants isolated in a similar type of genetic screen; here we focus on our novel findings.

emmA encodes a 15-kDa basic protein not found beyond the symbiotic Rhizobiales. Its predicted signal sequence looks more eukaryotic than those of Gram-negative bacteria, which may explain its predicted cytoplasmic location (60). EmmA has a 46-amino-acid glycine-rich (70%) central region but lacks conserved domains suggestive of function. Oriented divergently from emmA are emmB and emmC, encoding a two-component sensor histidine kinase and a response regulator, respectively. Expression data suggest that EmmBC activate emmA transcription (8). If EmmA is indeed exported to the periplasm, it may act to regulate EmmB activity (8), similarly to ExoR regulation of the histidine kinase ExoS (37).

Earlier studies on emmABC were performed in a S. meliloti strain WT for ExpR, which produces both EPS-I and EPS-II (8). Our mutants, derived from expR strain Rm1021, also produced abundant EPS-I, had motility defects, and formed nitrogen-fixing nodules on alfalfa (Table 1). Our emm mutant phenotypes differed by degree; the emmA-5 mutant exhibited the most severe phenotypes (Table 1; also Data Set S1 in the supplemental material).

The results of DOC sensitivity assays of our emm mutants differed substantially from those reported in previous work: our emmA-5 and emmB-33, -43, and -45 mutants behaved like the WT on 0.1% DOC and were only slightly more sensitive (<10 times) than the WT on 0.2% DOC (Table 1; also Data Set S1 in the supplemental material), whereas emmA and emmC mutants in an earlier study showed a 107-fold increase in sensitivity over the WT (8). This difference may be due to the different strains used: our Rm1021-derived strains cannot produce EPS-II on LB medium (25), while the strains used in the previous study have functional ExpR and produce abundant EPS-II (8). Previous work showed that the presence of ExpR correlated with salt sensitivity (7) and decreased fitness under laboratory conditions (88). We investigated whether ExpR was deleterious to the survival of our emm mutants on DOC by transducing the emmA-5 and emmB-45 insertions into the same ExpR+ strain used in the previous study (Rm8530) and assaying the strains on DOC plates. Compared to Rm8530, our emmA-5 ExpR+ and emmB-45 ExpR+ strains showed ∼104- and ∼102-fold increases in sensitivity to DOC, respectively, suggesting that ExpR is deleterious to emm mutants.

Transcripts of unknown function were increased, and motility transcripts were decreased, in the emmA::Tn5 mutant global transcriptome.

The pronounced EPS-I and motility phenotypes of the emmA-5 mutant are reminiscent of strains with increased activity of the ExoR-ExoS-ChvI (RSI) circuit, such as the exoR95::Tn5 and exoS96::Tn5 mutants, and strains overexpressing syrA (18, 22, 30). To understand the emmA-5 mutant in the context of other strains with increased EPS-I production and decreased motility, we defined the emmA-5 transcriptome during growth in LB using custom Affymetrix GeneChips (see Materials and Methods). We compared the emmA-5 Tn5-110 insertion strain MB805 to a strain carrying a putative “neutral” Tn5-110 insertion in SMb21477, encoding a reverse transcriptase-like protein. The latter strain, R4A2A, was like WT Rm1021 in growth, mucoid phenotype, calcofluor brightness, motility, and symbiosis. Expression of the corresponding SMb21477 gene was generally undetectable in Affymetrix GeneChip experiments, in agreement with our presumption that it is a neutral site. Thus, we used R4A2A as a Tn5-110-carrying control for our transcriptome analyses; however, the resulting data for R4A2A suggested that it behaves differently from the WT strain Rm1021 (see below).

Our initial analysis of the emmA-5 mutant using a ≥2-fold cutoff revealed increased expression of 95 gene and IGR probe sets and decreased expression of 81 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). We were surprised by the lack of increased exo gene expression in the emmA-5 mutant, because the EPS-I production of this mutant depends on exoY, and because exoY conferred 3.3-fold-increased expression in a different emmA mutant (8). Comparing Affymetrix GeneChip data from the R4A2A control strain with those from LB-grown Rm1021, collected earlier, we discovered that R4A2A showed increased exo gene expression (unpublished data). This means that our detection of increased exo gene expression in the emmA-5 mutant versus R4A2A was compromised. To examine changes in the genes and IGRs most directly related to the emmA-5 mutant phenotypes, we therefore used a 4-fold change cutoff for our comparisons (Table 2). None of these genes showed changed expression when R4A2A was compared to our legacy Rm1021 data, suggesting that they represent genuine changes in the emmA-5 mutant. emmA expression was increased ∼7-fold in the emmA-5 mutant; this may indicate that a positive-feedback loop upregulates emmA expression when functional EmmA is low; alternatively, it could represent transcription readthrough from the Tn5-110 Pnpt promoter (the 13 Affymetrix emmA ORF oligonucleotide probes are located almost evenly with respect to either side of the Tn5-110 insertion). Most of the 11 gene probe sets whose expression increased ≥4-fold in the emm-5 mutant encode hypothetical or conserved hypothetical proteins; the expression of 8 of the 11 (SMa0210, SMa0211, SMa1657, SMb21517, SMb21518, SMc00254, SMc01186, SMc01789) was significantly increased in a previous study of S. meliloti osmotic stress (89), a statistically significant overlap (P value for hypergeometric probability, 4 × 10−7). The increased expression of osmotic stress response genes in the emmA-5 mutant correlates well with data showing poor growth of emm mutants when osmotically stressed by 0.3 M NaCl (8).

TABLE 2.

Affymetrix GeneChip analysis of emmA::Tn5 insertion 5 (MB805) and SMb21477::Tn5 (R4A2A) strains

| Gene or IGR | Description of product | Fold changea |

|---|---|---|

| Expression increased in the emmA::Tn5 mutant over that in R4A2A | ||

| SMa0210 | Hypothetical protein, similar to SMc04866 | 70.0 |

| SMa0211 | Hypothetical protein | 51.6 |

| SMa1657 | Hypothetical protein | 14.6 |

| SMb20055i–SMb20056f2b | Intergenic region | 35.3 |

| SMb20055i–SMb20056f3b | Intergenic region | 27.5 |

| SMb20055i–SMb20056f4b | Intergenic region | 19.8 |

| SMb20055i–SMb20056f3_RCc | Intergenic region | 14.2 |

| SMb20671 | ABC transporter, periplasmic solute-binding protein | 4.0 |

| SMb21517 | Phosphodiesterase | 62.2 |

| SMb21518 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 82.6 |

| SMb21521 | EmmA, conserved hypothetical protein | 6.7 |

| SMc00254 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 10.1 |

| SMc01186 | Hypothetical protein | 8.3 |

| SMc01789 | Hypothetical protein | 97.5 |

| SMc03121 | ABC transporter, periplasmic solute-binding protein | 4.0 |

| Expression decreased in the emmA::Tn5 mutant from that in R4A2A | ||

| SMb21167 | Reverse transcriptase/maturase | −27.7 |

| SMb21477 | Reverse transcriptase/maturase | −20.7 |

| SMc00986 | Conserved hypothetical protein, DUF1217 family | −4.4 |

| SMc01163 | Dehydrogenase, scyllo-inositol utilization | −5.1 |

| SMc01165 | IolC, 2-deoxy-5-keto-d-gluconic acid kinase | −5.5 |

| SMc01166 | IolD, trihydroxycyclohexane-1,2-dione hydrolase | −4.0 |

| SMc02061 | BioS, biotin-regulated protein | −5.1 |

| SMc03005 | Conserved hypothetical protein | −4.9 |

| SMc03006 | CheY1, chemotaxis regulator protein | −5.3 |

| SMc03010 | CheB, chemotaxis-specific methylesterase | −6.4 |

| SMc03014 | FliF, flagellar M-ring transmembrane protein | −26.6 |

| SMc03019 | FliG, flagellar motor switch protein | −8.1 |

| SMc03020 | FliN, flagellar motor switch protein | −13.2 |

| SMc03021 | FliM, flagellar motor switch transmembrane protein | −13.6 |

| SMc03022 | MotA, flagellar motor protein | −36.3 |

| SMc03023 | Conserved hypothetical protein, DUF1217 family | −16.7 |

| SMc03024 | FlgF, flagellar basal body rod protein | −12.6 |

| SMc03025 | FliI, flagellum-specific ATP synthase | −13.5 |

| SMc03026 | Hypothetical protein | −5.5 |

| SMc03027 | FlgB, flagellar basal-body rod protein | −41.4 |

| SMc03028 | FlgC, flagellar basal-body rod protein | −21.5 |

| SMc03029 | FliE, flagellar hook-basal body protein | −33.9 |

| SMc03030 | FlgG, flagellar basal-body rod protein | −17.3 |

| SMc03031 | FlgA, flagellar basal body P-ring biosynthesis protein | −15.6 |

| SMc03032 | FlgI, flagellar P-ring precursor transmembrane protein | −6.9 |

| SMc03033 | MotE, chaperone specific for MotC folding/stability | −13.6 |

| SMc03034 | FlgH, flagellar L-ring protein precursor | −7.8 |

| SMc03035 | FliL, flagellar transmembrane protein | −6.7 |

| SMc03039 | FlaD, flagellin D | −6.0 |

| SMc03040 | FlaC, flagellin C | −7.6 |

| SMc03041 | Conserved hypothetical protein | −7.3 |

| SMc03044 | FliK, hook length control protein | −7.1 |

| SMc03046 | Rem, transcription regulator | −35.3 |

| SMc03047 | FlgE, flagellar hook protein | −16.6 |

| SMc03048 | FlgK, flagellar hook-associated protein | −12.4 |

| SMc03049 | FlgL, flagellar hook-associated protein | −19.0 |

| SMc03050 | FlaF, flagellar biosynthesis regulatory protein | −12.4 |

| SMc03051 | FlbT, flagellar biosynthesis repressor | −7.6 |

| SMc03052 | FlgD, basal-body rod modification protein | −9.6 |

| SMc03057 | Conserved hypothetical transmembrane protein | −4.6 |

| SMc03071 | Conserved hypothetical protein | −4.2 |

| SMc03072 | Conserved hypothetical protein | −4.2 |

The fold change, converted from the Affymetrix signal log ratio, is the average of all nine pairwise comparisons for probe sets whose transcript abundances differed by ≥4-fold. IGRs associated with genes (i.e., those likely corresponding to 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions) are not listed.

Intergenic region located between SMb20055 and SMb20056 genes (see Fig. 3A). SMb20056 encodes CbtJ, the periplasmic-binding component of a cobalt ABC transporter (91).

IGR probe set for the DNA strand complementary (_RC) to the SMb20055i–SMb20056f3 probe set.

Members of the putative SMb21518 and SMb21517 operon, divergently transcribed from emmBC, showed dramatically increased expression in the emmA-5 mutant (83-fold and 62-fold, respectively [Table 2]). SMb21518 has a predicted signal peptide sequence but no other conserved features; as with EmmA, orthologs are not found beyond the Rhizobiales. SMb21517 encodes a putative phosphodiesterase that degrades the second messenger 3′,5′-cyclic di-GMP (cDG). An SMb21517 insertion mutant of the closely related S. meliloti Rm2011 strain was like the WT for EPS production, biofilm formation, motility, and symbiosis with alfalfa, but overexpression of SMb21517 resulted in decreased motility, decreased biofilm formation, and 33-fold-increased intracellular cDG levels (90). Thus, high expression of SMb21517 in the emmA-5 mutant could explain its severe motility defect but does not explain its increased EPS-I production. Additional experiments would be needed to clarify whether polar effects of the emmA-5 insertion are responsible for the observed elevated expression of SMb21518 and SMb21517.

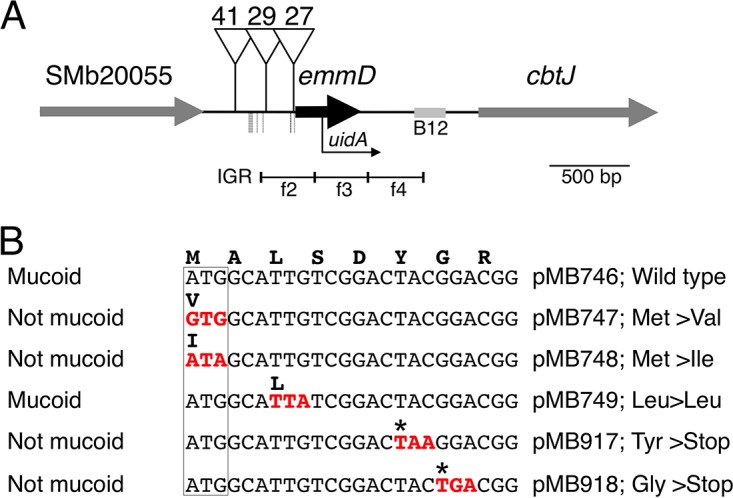

Perhaps the most interesting result from the emmA mutant transcriptome was increased expression of IGR probe sets located in the SMb20055–SMb20056 (cbtJ) IGR (Table 2; Fig. 3A). These were the only IGR probe sets with increased expression that did not correspond to 5′ or 3′ untranslated regions of genes with altered expression in the emmA-5 mutant transcriptome (Table S2 in the supplemental material). The significance of this result is presented in the following section.

FIG 3.

(A) Map of the emmD region. The emmD ORF is indicated by a black arrow, located on the positive strand of the S. meliloti pSymB replicon at nt 65537 to 65935. Triangles show the locations of Tn5 insertions 41, 29, and 27, which allow constitutive expression of emmD from Ptrp. The bent arrow indicates the insertion point of a transcriptional emmD fusion. IGRs corresponding to the SMb20055-to-SMB20056 (cbtJ) IGR probe sets and listed in Table 2 are designated by their unique suffixes: f2 stands for SMb20055i to SMb20056f2 and encompasses nt 65316 to 65647; f3 encompasses nt 65648 to 65979; f4 encompasses nt 65980 to 66311. The B12 riboswitch, regulating cbtJKL expression (91), is shaded. Nine potential transcription start sites identified in reference 57 are indicated by dotted lines below the main map line. (B) Site-directed mutagenesis of emmD. Ptrp expression plasmids carrying WT (pMB746) and mutant alleles of emmD were tested for a mucoid phenotype in S. meliloti Rm1021. The DNA sequence alignment shows the first eight codons of the emmD ORF for the WT and five mutants. Single-letter codes for each of the corresponding amino acids are shown in boldface above the DNA sequence; the specific change is given on the right. Putative start codons are boxed; mutated codons are shown in red with the amino acid change above. Asterisks indicate stop codons.

Of the genes whose expression decreased in the emmA-5 mutant, almost all seem to be coordinately downregulated in other situations where motility is decreased, as described above, and this is consistent with our results showing decreased swim motility on soft agar plates and decreased PflaC::uidA expression in the emmA-5 mutant (Fig. 1 and 2; Table 1; also Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). The nucleotide sequences of two of the genes whose expression is not coordinately regulated with motility and chemotaxis genes, SMb21477 and SMb21167, are almost identical; their respective probe sets are likely to cross-recognize the SMb21477 transcript, which may be increased in the R4A2A mutant due to readthrough from a Tn5-110 promoter. Expression of the SMc01163-to-SMc01166 genes, encoding enzymes involved in inositol utilization, is increased in other situations where motility is decreased; we previously showed that the expression of these genes is dependent on ChvI and thus is increased under conditions where RSI circuit activity is increased and motility is decreased (18, 30, 32). In agreement with the latter result, and aside from increased exo gene and decreased motility gene expression, the emmA-5 mutant and RSI circuit transcriptomes do not appear to overlap, supporting the earlier hypothesis that EmmABC and the RSI circuit “may act in parallel but separate fashions” to regulate EPS production and motility (8).

Transcripts detected in the SMb20055-cbtJ intergenic region belong to a previously unidentified gene encoding a small protein.

We discovered that there was increased (14- to 28-fold) expression of three contiguous probe sets located in the SMb20055-to-SMb20056 (cbtJ) IGR (Table 2; Fig. 3A), the only probe sets that did not correspond to 5′ or 3′ untranslated regions of genes with altered expression in the emmA-5 mutant transcriptome (Table S2 in the supplemental material). SMb20055 encodes a transcriptional regulator, while SMb20056 encodes CbtJ, the periplasmic-binding component of a cobalt transport system (Fig. 3A) (91).

In addition to being upregulated in the emmA-5 mutant, this region is located downstream of three Tn5-110 insertions identified in our screen: insertions 27, 29, and 41 (Table 1; Fig. 3A). Each mutant overproduced EPS-I and was similar to the WT in growth, motility, DOC sensitivity, and symbiosis (Table 1; also Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). The Tn5-110 in mutants with insertions 27, 29, and 41 is oriented such that Ptrp may drive expression toward cbtJ (Fig. 3A). Examination of the region downstream of these insertions allowed us to identify an ORF encoding an 11-kDa protein, which we named EmmD because of its apparent connection to the EmmABC regulatory circuit (Fig. 3A) We previously identified nine putative transcription start sites upstream of emmD (Fig. 3A) (57). To test if this region was responsible for the mucoid phenotype of our three mutants, we cloned DNA carrying the emmD ORF into the broad-host-range Ptrp expression vector pRF771, creating pMB746. When conjugated into the WT strain Rm1021, pMB746 conferred a mucoid phenotype (Fig. 3B), and cells were motile—the same phenotypes as those of the mutants with insertions 27, 29, and 41. We tested whether the phenotypes conferred by pMB746 were due to the putative emmD ORF by making plasmids carrying emmD ORFs with single nucleotide changes (Fig. 3B; see also Table S3 in the supplemental material). Three of these plasmids contained mutations in potential start codons: pMB747 or pMB748 changed the initial ATG (Met) codon to GTG (Val) or ATA (Ile), respectively; pMB749 changed the third TTG (Leu) codon to TTA (Leu), which cannot act as a translational start codon. Only the last plasmid (pMB749) conferred a mucoid phenotype, indicating that ATG is the likely start codon for emmD (Fig. 3B). Since GTG can often substitute for ATG for translation initiation, but emmD with a GTG start was not mucoid, we made two additional plasmids with mutations that introduced a stop codon early in the emmD ORF: pMB917 changed the TAC (Tyr) codon to TAA (stop), and pMB918 changed the GGA (Gly) codon to a TGA (stop) (Fig. 3B). Early chain termination of the emmD ORF failed to confer a mucoid phenotype when conjugated into Rm1021, confirming that EmmD overexpression confers the mucoid phenotype.

We transduced a reporter fusion (emmD::uidA) (MB693) into the emmA-5, emmB-33, emmB-43, and emmB-45 mutants to verify transcriptomic results and to define interaction with other genes. Table 3 shows that the GUS activity of the resulting strains increased significantly. We also transduced the same reporter into the SMb20055-20056-29 mutant to generate MB694 and used it to obtain additional evidence that the Ptrp of Tn5-110 mutant 29 likely drives emmD expression. As predicted, MB694 showed much higher GUS activity than MB693 (6,122 versus 54 U, respectively).

TABLE 3.

β-Glucuronidase activity of an emmD-uidA fusion in emmA::Tn5 and emmB::Tn5 mutant strains

| Strain | Description | β-Glucuronidase activity (U)a |

|---|---|---|

| MB693 | emmD-uidA | 0 ± 0 |

| MB724 | emmA::Tn5 insertion 5; emmD-uidA | 3,073 ± 41 |

| MB725 | emmB::Tn5 insertion 33; emmD-uidA | 50 ± 9 |

| MB729 | emmB::Tn5 insertion 43; emmD-uidA | 6,945 ± 11 |

| MB726 | emmB::Tn5 insertion 45; emmD-uidA | 8,049 ± 284 |

Data are results of one representative experiment and are averages ± standard deviations for two independent exponential-phase cultures (OD600 range, 0.3 to 0.6). The GUS activity of the emmD-uidA fusion differed between assays but was usually <100 U.

Our emmA-5 transcriptome and emmD::uidA fusion results led us to ask if the mucoid phenotypes of the emmA and emmB mutants were due to increased levels of EmmD. We constructed a marked (Hy) complete deletion of emmD (MB738), transduced it into the emmA and emmB mutants (Table S1 in the supplemental material), and assayed for calcofluor white and mucoid phenotypes: mutants with insertions 5, 43, and 45 that also had emmD deleted were more calcofluor bright and mucoid than WT, but less so than their parent emm mutant strains (unpublished data). These results show that emmD may contribute to, but is not solely responsible for, the mucoid phenotype of the emmA and emmB mutants. We inoculated alfalfa with the ΔemmD and emmA-5 ΔemmD mutants and found that both mutants elicited normal, nitrogen-fixing nodules.

How EmmD overexpression causes EPS-I overproduction is unknown. EmmD is not found beyond the genus Sinorhizobium and contains no sequence or structural domains conserved in other proteins. Because emmD is located just upstream of the cbtJKL genes for cobalt transport, which are regulated by cobalamin levels (91), we wondered if cobalt or cobalamin supplementation might abrogate the increased EPS-I abundance of emmD-overexpressing strains. Supplementing such strains with 50 ng/ml CoCl2·6H2O, 2 μM cobalamin, or CoCl2 plus cobalamin had no visible effect on their mucoid phenotype; this argues that the increase in EPS-I seen upon emmD overexpression is not likely due to cobalt or cobalamin limitation. It thus seems unlikely that EmmD plays a major role in cobalt or cobalamin metabolism; instead, EmmD may be involved in fine-tuning the EmmABC regulatory circuit.

Other mutants with intergenic region insertions.

The SMa1660–1662-IGR-19 mutant had mucoid colonial morphology as its only significant tested phenotype. Its Tn5 insertion may alter the transcription of SMa1660, encoding a protein 50% identical to the putative NrgA acetyltranferase of Bradyrhizobium japonicum (92). The nitrogen metabolism regulators NifA and RpoN (σ54) control nrgA expression, but nrgA mutants nodulate host plants normally (92). We identified a transcription start site upstream of SMa1660, but no σ54 (−24 to −12) promoter motif, suggesting that its regulation differs from that in B. japonicum (57).

We considered discounting the SMa0742–groESL2-IGR-48 mutant as a false positive, because its mucoid phenotype was slight, before discovering that it showed greatly reduced PflaC::uidA expression. This insertion lies 107 bp upstream of SMa0742 and is oriented such that Ptrp could drive its expression. However, the putative ORF SMa0742 is classified as hypothetical: it is not conserved even among other S. meliloti strains, and expression evidence from global transcriptome studies is lacking (21, 57); thus, SMa0742 may not represent a genuine protein-encoding gene.

Concluding remarks.

Here we report the isolation of insertion mutants representing 30 unique genes and IGRs, 14 of which have not been described previously in S. meliloti, demonstrating the continued utility of genetic screens for specific phenotypes as an important discovery tool. Most of our mutants were affected in the production of EPS-I, rather than EPS-II, since S. meliloti Rm1021 lacks ExpR, which is required for the expression of EPS-II biosynthesis genes (25). Our set of varied mutants is consistent with diverse roles for EPS in growth, metabolism, cell division, envelope homeostasis, biofilm formation, stress response, motility, and symbiosis (6–9, 18, 20, 24, 31, 32, 40, 41, 47, 53, 61, 79, 90). The importance of EPS is reflected in the complexity of its regulation and the ongoing discovery of new regulators (93–96).

Our isolation of many motile mutants with significantly increased EPS-I production has forced a reexamination of our earlier observation that increased EPS-I production is obligatorily paired with decreased swim motility (21). We now understand that previous studies suggesting such a strong correlation were biased toward participants in the regulation of the RSI circuit (18, 21, 30) and the cell cycle (47, 53, 77). Details as to how the motility of S. meliloti Rm1021 is coordinately downregulated while EPS-I production is increased remain unknown. The expression of genes for motility and chemotaxis functions is decreased with increased activity of the RSI circuit (18, 22, 30, 32), but the expression of those genes does not increase when RSI circuit activity is attenuated (32); evidence for direct effects on their expression mediated by the RSI circuit is lacking.

MucR is an attractive candidate for inverse regulation of motility with EPS-I production, because while MucR represses the expression of genes for motility and EPS-II biosynthesis, it positively affects the expression of exo genes for EPS-I biosynthesis (40, 41). Recently, MucR was postulated to regulate the transcription of genes necessary for the S-to-G1 transition, suggesting a means of coordinating EPS production and motility with the cell cycle (97). Mucoid mutants identified in this and other studies will be useful tools for analyzing ChvI and MucR circuitry and may help delineate specific roles in regulating EPS production. The CtrA master cell cycle regulator appears to regulate, directly and indirectly, subsets of genes in the motility and chemotaxis regulon, indicating that control of motility is complex, likely responding to multiple, varied inputs (98). Recent studies on cDG and the regulation of its synthesis in S. meliloti provide new insights into how motility and cell surface polysaccharide genes (including exo) may be coordinately regulated (90, 94, 95).

In summary, our study of S. meliloti mucoid mutants suggests new roles for EPS in cell function, identifies novel genes related to its production, and provides a set of mutants for continued exploration of EPS regulatory circuits and S. meliloti biology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

Table S1 in the supplemental material shows the strains and plasmids used in this study. S. meliloti strains were grown in M9 sucrose medium (supplemented with 500 ng/ml biotin), LB medium (5 g/liter NaCl), or TY medium at 30°C, as described previously (30). GYM agar plates were prepared as described previously (81). E. coli strains were grown in LB medium at 37°C. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin (Ap), 50 to 100 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol (Cm), 50 μg ml−1; gentamicin (Gm), 5 μg ml−1 for E. coli and 25 to 50 μg ml−1 for S. meliloti; hygromycin (Hy), 50 μg ml−1; kanamycin (Km), 25 to 50 μg ml−1 for E. coli; neomycin (Nm), 50 to 100 μg ml−1 for S. meliloti; spectinomycin (Sp), 50 μg ml−1 for E. coli and 50 to 100 μg ml−1 for S. meliloti; streptomycin (Sm), 500 μg ml−1 for S. meliloti; and tetracycline (Tc), 10 μg ml−1. Triparental conjugations were used as described previously (30) to transfer both replicative and nonreplicative plasmids to S. meliloti. Marked insertions and deletions were transferred between S. meliloti strains using N3 phage transduction as described previously (30). The oligonucleotide primers used in this study are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material. We used standard techniques for cloning and PCR amplification. E. coli strains DH5α and NEB5α (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) were used as plasmid hosts. The Hy-marked emmD deletion strain was constructed using sucrose counterselection as described previously (30). Site-directed mutagenesis of the emmD ORF was performed by amplifying Rm1021 genomic DNA with oligonucleotide primers containing the desired mutation and NsiI and BamHI restriction sites that allowed cloning into the Ptrp vector pRF771.

Tn5 mutagenesis and screening.

pJG110 carrying mini-Tn5-110 (48) was introduced into S. meliloti strains carrying genomic transcriptional uidA (encoding GUS) fusions to either the flaC (MB669) or the mcpU (MB671) promoter. The corresponding WT flaC and mcpU genes are retained in each of these strains. Transconjugants were plated on agar plates (1.5% agar) with M9 sucrose, TY, LB, or LB supplemented with 2 μM cobalamin (vitamin B12). Mucoid colonies, and those with other unusual morphologies, were restreaked on the same medium to check colony phenotype. The location of each Tn5 insertion was determined by arbitrary PCR amplification (Table S3 in the supplemental material). All Tn5 insertions of interest were transduced from the original mutant strains into either Rm1021 (WT; resulting in strains MB801 to MB864) or MB669 (PflaC::uidA; resulting in strains MB901 to MB964) for further tests.

Phenotypic assays.

Examples of the results of the phenotypic assays used in this study are shown in Fig. 1. Detailed results are presented in Table 1 and in Data Set S1 in the supplemental material. Mucoid colonial morphology was evaluated by streaking colonies onto plates with 1.5% Bacto agar. EPS-I production was assayed on LB agar plates containing 0.02% calcofluor white (also known as Fluorescent Brightener 28; catalog no. F3543; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and was visualized by excitation with 366-nm UV light. Each strain was tested at least twice. Deoxycholate (DOC) sensitivity was assayed by spotting serial dilutions of cultures (at an optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of ∼0.7) onto LB agar plates containing 500 μg ml−1 Sm, with or without the addition of 0.1% or 0.2% sodium deoxycholate (catalog no. D6750; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) after autoclaving of the medium. Rm1021 was used as a WT control, and lpsB mutant R5D6 was used as a DOC-sensitive control. Each strain was tested at least twice.

Swimming motility was assayed by inoculating cells into TY-0.22% agar plates supplemented with 500 μg ml−1 Sm. The diameter of each colony was measured at 3 or 4 days after inoculation. Two replicates were averaged for each mutant, and the average for the mutant was compared to the average for the Rm1021 WT control assayed at the same time. The swimming motility of strains that grew poorly on TY was also measured on LB agar plates supplemented with 2.5 mM calcium chloride and 500 μg ml−1 Sm.

GUS activity was assayed as described previously (30). Strains were cultured in tubes, except for the PflaC::uidA assays for which results are shown in Fig. 2, where cells were grown in 300 μl TY or LB medium (strains MB669, MB910, MB914, MB928, MB947) in 2.0-ml DeepWell 96-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark), with shaking at 1,500 rpm on a Mix-EVR Invitro shaker (Taitec, Koshigaya, Japan) at 30°C. Strains MB907, MB962, and MB963 were supplemented with 3 μM vitamin B12. Because Nm decreased swim motility and the expression of a PflaC::uidA gene fusion (unpublished data), the PflaC::uidA strains were first grown from single colonies under full antibiotic selection, then back-diluted into media containing only Sp and Sm, and finally grown for 7 h.

Nodulation assays on Medicago sativa cv. AS13 (alfalfa) were performed as described previously (30) except that alfalfa seedlings were grown in culture tubes. Twelve to 14 plants were assayed for each strain. Seedlings were inoculated 1 day after planting in tubes by adding 0.5 ml of bacteria (washed and resuspended in 10 mM MgSO4 to an OD600 of 0.05). Plant appearance, nodule number, and nodule color were monitored for 4 weeks and were compared to those for WT and uninoculated controls.

Affymetrix GeneChip analysis.

For microarray transcriptome analysis of S. meliloti, we used a custom dual-genome Affymetrix Symbiosis Chip with probe sets corresponding to S. meliloti genes and intergenic regions (IGRs) (21). Cultures for RNA purification were inoculated from single colonies into 20 ml LB with 500 μg ml−1 Sm in 250-ml baffled flasks and were grown with shaking (250 rpm) at 30°C. Three biological replicates each were analyzed for strains MB805 (emmA::Tn5) and R4A2A (SMb21477::Tn5; control strain). Cells were harvested in exponential phase (OD600, 0.61 to 0.69) and were processed as described previously (21), except that Affymetrix GeneChip Operating System software was used instead of the MicroArray Suite for comparison analysis. For the results shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material, we deemed an increase or decrease in the average signal log ratio of ≥1 (2-fold) to be significant if at least 8 of the 9 pairwise comparisons of the 3 experimental and 3 control replicates were evaluated by the software as showing a significant change (P ≤ 0.05). Table 2 shows the same data for ≥4-fold changes and does not include some IGR probe sets.

Whole-genome sequencing and correlation of genome sequence variants with phenotypes.

Genomic DNA from S. meliloti OM40 and an Rm1021 control was purified using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The resulting DNA was sequenced using MiSeq technology (Illumina, Hayward, CA) by the Stanford Protein and Nucleic Acid Facility. Read assembly and variant analysis were performed using the following CLC Bio Genomics Workbench (version 6; Qiagen, Aarhus, Denmark) software tools: quality-based variant detection (35% cutoff for variant frequency), structural variant detection (P value, ≤0.0001), and large-gap mapping tool. Aligned reads were examined for all potential variants identified by the software, and positive results were confirmed by PCR amplification and sequencing. To determine which sequence variant was responsible for the phenotypes of strain OM40, we constructed derivatives of WT Rm1021, each with a Hy marker located in a putative neutral region near the gene variant to be tested: the SMc01380 IGR for the rpoA variant (spaced ∼14 kb apart), the SMb21275 IGR for the SMb21268 variant (∼8 kb apart), and the SMb21203 IGR for the htpG variant (∼26 kb apart). We introduced the Hy marker via homologous recombination using a nonreplicating, resistant pDW33-derived plasmid carrying DNA from the putative neutral region, and we then transferred that variant into Rm1021 by transduction, selecting for Hy resistance (see above). We also created Rm1021 strains with the same Hy-resistant insertions, which enabled us to use transduction to replace a given single nucleotide variant with the WT allele.

Accession number(s).

The Affymetrix GeneChip data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession no. GSE100707. Data for the EmmD ORF are available under GenBank accession number BK010202.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS