Organic thin-film transistors exhibit an unprecedented level of reliability, bringing them closer to commercialization.

Abstract

Organic thin-film transistors (OTFTs) can be fabricated at moderate temperatures and through cost-effective solution-based processes on a wide range of low-cost flexible and deformable substrates. Although the charge mobility of state-of-the-art OTFTs is superior to that of amorphous silicon and approaches that of amorphous oxide thin-film transistors (TFTs), their operational stability generally remains inferior and a point of concern for their commercial deployment. We report on an exhaustive characterization of OTFTs with an ultrathin bilayer gate dielectric comprising the amorphous fluoropolymer CYTOP and an Al2O3:HfO2 nanolaminate. Threshold voltage shifts measured at room temperature over time periods up to 5.9 × 105 s do not vary monotonically and remain below 0.2 V in microcrystalline OTFTs (μc-OTFTs) with field-effect carrier mobility values up to 1.6 cm2 V−1 s−1. Modeling of these shifts as a function of time with a double stretched-exponential (DSE) function suggests that two compensating aging mechanisms are at play and responsible for this high stability. The measured threshold voltage shifts at temperatures up to 75°C represent at least a one-order-of-magnitude improvement in the operational stability over previous reports, bringing OTFT technologies to a performance level comparable to that reported in the scientific literature for other commercial TFTs technologies.

INTRODUCTION

From smartphones to flat-panel TVs, thin-film transistors (TFTs) are a core technology of modern displays (1–3). TFTs are also becoming an enabling technology for radio frequency identification (4) and a wide range of sensing applications (5–7). The commercial adoption of TFT technologies was enabled by the use of hydrogenated amorphous silicon (a-Si:H) (2). However, a-Si:H TFTs exhibit limited carrier mobility (μ), with values in the range of 0.5 to 1 cm2 V−1 s−1 (2), hindering the development of fast-switching circuits. They also suffer from large threshold voltage (VTH) instabilities that can be mitigated by using circuit-based compensation schemes but at the expense of the simplicity of backplane circuit designs (8, 9). To overcome these limitations, research and development efforts in recent years have focused on TFTs based on other semiconductor materials such as microcrystalline Si (μc-Si) (10), polycrystalline Si (poly-Si) (11), amorphous oxides (a-oxides) (1), and organic semiconductors (12–15).

To date, poly-Si and a-oxide TFTs have found their way into commercial display products because of their large μ values and superior VTH stability when compared to those displayed by a-Si:H TFTs. In contrast, although μ values of state-of-the-art microcrystalline (small molecule) or nearly amorphous (conjugated polymer) organic thin-film transistors (OTFTs) now surpass those found in a-Si:H TFTs and approach those found in some a-oxide TFTs (16–18), their VTH stability remains inferior to that displayed by a-Si:H TFTs and constitutes an important point of concern toward their wide commercial deployment and adoption (12, 19).

The primary mechanism behind VTH instability in OTFTs arises from the trapping of charge carriers or molecular species (such as oxygen or water) at defect sites located at microcrystalline boundaries, nanometer-sized voids (due to porosity), or at the semiconductor-dielectric interface (20, 21). To date, many approaches to reduce or passivate these trap sites include the use of postprocessing thermal annealing (22) and amorphous fluoropolymers (for example, CYTOP) as gate dielectric layers (23). Although the use of CYTOP leads to OTFTs with reduced bias stress effects (24), devices with a single CYTOP dielectric layer typically also operate at high voltages and display shifts of VTH that monotonically vary in time (20). Very recently, the use of molecular additives has been shown to lead to OTFTs with a greatly improved environmental stability and with an operational stability comparable to that displayed by single-crystal organic field-effect transistors (sc-organic FETs) (19). This is significant because, before this recent report, only in the absence of crystalline boundaries and porosity, such as in sc-organic FETs, have OTFTs been able to display VTH stability superior to that of a-Si:H TFTs (14). Although previous studies have shown that μc-OTFTs can display stability comparable or superior to that of “low-temperature” (150° to 350°C) processed a-Si:H and metal-oxide TFTs under moderate-bias conditions (that is, VGS >> VDS) (25), under high-bias conditions (that is, VGS = VDS), the degradation is generally more severe. Hence, under high-bias conditions, even sc-organic FETs and OTFTs using molecular additives have shown to date a VTH stability that is inferior to that reported in the scientific literature for other commercial TFT technologies, in particular, μc-Si, a-oxide, and poly-Si TFTs (the last displaying the most stable performance of all TFT technologies) (26).

In the past, we introduced an approach that enabled low-voltage operation and improved environmental and operational stability of μc-OTFTs (15, 20). This approach consists of using a bilayer gate dielectric (for example, CYTOP/metal oxide) instead of the commonly used single-layer gate dielectric (for example, CYTOP or metal oxide) and has been proven effective in OTFTs with channel layers comprising either small molecules (20, 27), polymers (13), or small-molecule/polymer blends (13, 20). In the bilayer gate dielectric approach, the second dielectric layer appears to compensate for the shift of VTH induced by the trapping of carriers, thereby introducing a second mechanism that produces an opposite VTH shift over time (for example, charge accumulation within the dielectric layer by slowly oriented dipoles). Specifically, we have shown that, when this second gate dielectric layer comprises a single metal oxide (for example, Al2O3) processed by atomic layer deposition (ALD), n- and p-channel μc-OTFTs operate at low-voltage values with good operational stability and excellent environmental stability, remaining functional after being subjected to oxygen plasma for several minutes and being immersed in water for several hours (13). Furthermore, when the second gate dielectric layer comprises a first layer of Al2O3 by ALD, deposited on CYTOP, and a second nanolaminate (NL) layer comprising nanometer-thick alternating layers of Al2O3 and HfO2 by ALD, μc-OTFTs can even sustain immersion in water at 95°C for tens of minutes (12). Here, we build on this approach by showing that μc-OTFTs with an optimized bilayer gate dielectric comprised of a first CYTOP layer and a second Al2O3:HfO2 NL layer grown by ALD display improved environmental stability and unprecedented operational stability, with VTH shifts that are comparable to or smaller than the ones reported in the scientific literature for μc-Si and a-oxide TFTs over time. Furthermore, the small VTH shifts displayed by these μc-OTFTs are weakly dependent on temperature variations at least up to 50°C above room temperature (RT), thus highlighting the robustness of this approach.

RESULTS

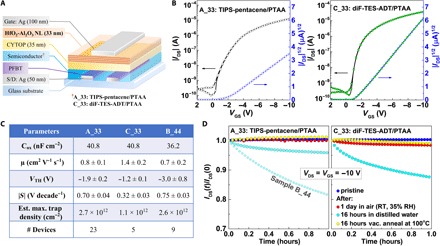

Figure 1A shows the architecture of top-gate bottom-contact μc-OTFTs. The detailed fabrication process is described in Materials and Methods. The devices in this work are named with the letters “A,” “B,” and “C” to indicate specific device geometries and followed by “_#” to indicate the NL layer thickness. In A_# and B_# devices, the semiconductor layer is composed of a 6,13-bis(triisopropylsilylethynyl)–pentacene (TIPS-pentance)/poly[bis(4-phenyl) (2,4,6-trimethylphenyl) amine] (PTAA) blend, and in C_# devices, the semiconductor layer is composed of a 2,8-difluoro-5,11-bis(triethylsilylethynyl) anthradithio-phene (diF-TES-ADT)/PTAA blend. The gate dielectric layer in A_# and C_# devices is composed of CYTOP (35 nm)/ALD Al2O3:HfO2 NL (# nm). The ALD NL layer was synthesized at 110°C by the repeated alternation of five ALD cycles of Al2O3 and five ALD cycles of HfO2. As a reference, we also fabricated TIPS-pentacene/PTAA μc-OTFTs having the gate dielectric geometry that we recently reported (12): CYTOP (35 nm)/ALD Al2O3 (20 nm)/ALD NL (44 nm), herein referred to as B_44 devices. The properties of type A and B μc-OTFTs with different NL thickness values are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Fig. 1. General electrical properties and environmental stability.

(A) The structure of top-gate bottom-contact μc-OTFTs with gate dielectric layers of CYTOP/NL. The semiconductor layers of A_33 and C_33 are TIPS-pentacene/PTAA blend and diF-TES-ADT/PTAA blend, respectively. (B) Transfer characteristics of as-fabricated μc-OTFTs of A_33 (left) and C_33 (right). (C) Electrical parameters of A_33, C_33, and B_44. (D) Environmental stability under continuous dc-bias stress for μc-OTFTs under different ambient conditions.

The pristine transfer characteristics of champion A_33 and C_33 μc-OTFTs measured in a N2-filled glove box are shown in Fig. 1B. All devices exhibited hysteresis-free electrical characteristics. Figure 1C summarizes statistical values of the electrical parameters for pristine μc-OTFTs of all types (W/L = 2550 μm/180 μm). The electrical parameters of A_33 μc-OTFTs are comparable to those measured in B_44 μc-OTFTs (see fig. S1 and table S1) and to those measured in TIPS-pentacene/PTAA–based μc-OTFTs having a CYTOP/ALD-oxide bilayer gate dielectric (12, 20). C_33 devices also display similar performance parameters to previously reported diF-TES-ADT/PTAA–based μc-OTFTs with a CYTOP/ALD Al2O3 bilayer gate dielectric (13).

In the past, we had shown that μc-OTFTs with a CYTOP/Al2O3/NL gate dielectric (that is, B_44 μc-OTFTs) exhibited superior environmental stability (when immersed in near-boiling water) in comparison to those with a CYTOP/Al2O3 gate dielectric (12). Here, first, we conduct a direct comparison of the environmental stability of A_33, C_33, and B_44 μc-OTFTs before and after exposure to two different environmental conditions: (i) air with a relative humidity (RH) of 35% for 1 day and (ii) immersion in distilled water for 16 hours. Figure 1D shows the normalized temporal changes of the source-to-drain current, IDS(t)/IDS(0) ≡ 1 + ΔIDS(t), measured on champion devices in the saturation regime (that is, on-state gate bias stress, VDS = VGS = −10 V) for 1 hour. Air exposure produces |ΔIDS(t)| < 1% on A_33, C_33, and B_44 (shown in fig. S3) μc-OTFTs. In contrast, prolonged immersion in water (16 hours) results in larger |ΔIDS(1 hour)| values, with changes in B_44 devices found to be significantly larger (ca. 20 to 35%) than those observed in A_33 (ca. 4 to 8%) and C_33 (ca. 12%) devices. These changes were not permanent but were reversible after devices were vacuum-annealed at 100°C for 16 hours. These trends are qualitatively consistent with our previous reports where, for instance, μc-OTFTs having a CYTOP/ALD Al2O3 gate dielectric yielded |ΔIDS(10 min)| > 10% after immersion in water for 16 hours (13), significantly larger than |ΔIDS(1 hour)| values in A_33, C_33, and B_44 devices. Hence, whereas it is clear that water absorbed during prolonged exposure leads to degradation of the device operational stability under continuous bias stress, the presence of single ALD Al2O3 layers in the architecture of a μc-OTFT (for example, B_44 μc-OTFTs) also leads to increased device sensitivity due to the presence of water in the environment. Therefore, the device architecture of A_33 and C_33 devices is not only less complex than that of B_44 devices but also leads to superior environmental stability.

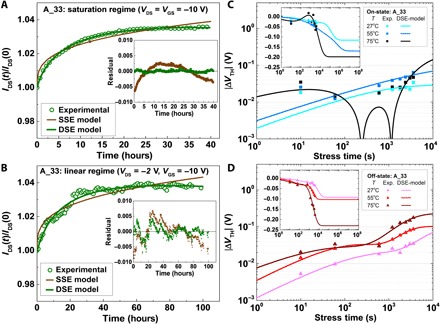

Next, we turn to the long-term operational stability of A_33 μc-OTFTs. Figure 2 (A and B) shows the temporal evolution of IDS(t)/IDS(0) during continuous on-state gate bias stress test in the saturation regime (VDS = VGS = −10 V) for 40 hours and in the linear regime (VDS = −2 V, VGS = −10 V) for 100 hours. In both regimes, A_33 devices exhibit high stability, with |ΔIDS(t)| < 4% after tens of hours of continuous operation. Note that the operational stability is dependent on the bias conditions (that is, VGS and VDS) and channel sheet resistance, as reported by Bisoyi et al. (25). Here, under high-bias conditions (VGS = VDS) and with a channel sheet resistance of 10 megaohms/square, measured IDS changes are below 4% even after stress times in the 105-s range. Furthermore, operational stability tests shown in fig. S9, on devices with a smaller channel length of 85 μm, reveal IDS changes below 1% after similar stress times in the 105-s range. Hence, in contrast to previous studies (25), our devices do not reach the 10% IDS decay lifetime after comparable stress times.

Fig. 2. Operational and temperature stability in N2 during continuous dc-bias stress.

Temporal evolution of the normalized IDS during dc-bias stress (A) at saturation regime (VDS = VGS = −10 V) for 40 hours with fitted curves and (B) at linear regime (VDS = −2 V, VGS = −10 V) for 100 hours with fitted curves. The insets show the fitting residuals of the SSE model (brown) and the DSE model (green). The |ΔVTH| values after dc-bias stress of as-fabricated A_33 devices (C) at on-state (VDS = VGS = −10 V) and (D) at off-state (VDS = 0 V, VGS = 10 V) bias stress tests under different temperatures in the dark, with curves fitted from corresponding ΔVTH values using the DSE model (see insets).

To rationalize the temporal changes of IDS(t) and to extrapolate the long-term stability of these μc-OTFTs, first, it is necessary to validate a model that describes these changes. In contrast to μc-OTFTs with a single gate dielectric layer, we have suggested that μc-OTFTs with a bilayer gate dielectric are subject to two distinct mechanisms that can lead to a change of properties over time (20). The first one, more commonly reported, causes a decrease of IDS(t)/IDS(0) during continuous dc-bias stress due to charge trapping at or around the semiconductor-dielectric interface (9, 14). This contribution is described by assuming that VTH(t) follows a single stretched-exponential (SSE) model (eq. S1). In our devices, we observe a second effect causing IDS(t)/IDS(0) to increase over time (13). The latter effect is observed regardless of channel morphology (that is, small molecules, polymers, or small-molecule/polymer blends) and type of transport in the channel (that is, n- or p-channel) (12, 13) and even in OTFTs having CYTOP/HfO2 bilayer gate dielectrics (see fig. S5). Although the specific physical mechanism remains unclear at this point, the effect appears general. Furthermore, as we show below, it can be controlled by varying the metal oxide layer thickness and modeled by assuming that VTH(t) also follows an SSE functional form (eq. S2) but with opposite sign to the one attributed to the first effect (eq. S1) as the second effect compensates for the effect of trapping. In view of these considerations, we define the following analytical expression for ΔVTH(t), which we refer to as the double stretched-exponential (DSE) model

| (1) |

where τi are the characteristic decay times, βi are the dispersion parameters (0 <βi< 1), and ΔVTH,i∞ = [VTH,i(∞)–VTH(0)] is the threshold voltage change expected as time tends to infinity (i = 1 or 2). Equations S4 and S5 present VTH(t)-related analytical expressions for IDS(t) in the linear and saturation regimes, respectively (9, 28, 29). Figure 2 (A and B) displays a comparison of the best fits to the experimental data and the residuals (insets) using the SSE and DSE models. This comparison reveals that the DSE model better describes IDS(t) under on-state dc-bias stress than the SSE model, particularly in the saturation regime and at a longer time. Figure S6 confirms these observations for a wider range of OTFT geometries. The parameters used to fit the data using both models are presented in tables S2 and S3. We note that, as shown in figs. S4 and S5, the operational stability of IDS depends on the gate dielectric geometry, that is, the thickness of the NL, and consequently can be tailored. Because of practical constraints, values of ΔVTH,i∞ cannot be unequivocally determined using this fitting procedure. Instead, the ratio m = ΔVTH,1∞/ΔVTH,2∞ can be derived. We have found this ratio to be dependent on the NL layer’s thickness, with devices displaying improved stability when m ≈ 1. However, values of τi and βi are less dependent on the NL thickness and are remarkably similar for both contributions to ΔVTH(t), with τi values in the range of 104 s and βi values in the range of ca. 0.4 to 0.6. Figure S8 shows the contributions of the two opposite aging mechanisms, ΔVTH,1(t) and ΔVTH,2(t), of devices with different gate dielectric geometries under on-state bias stress. This similarity in the dynamics of both competing processes is unique if compared to other previous systems reported in the literature (28) and allows the thickness of the NL to be used as a parameter to optimize the long-term stability of these OTFTs.

Next, we focus our attention on VTH changes occurring during positive and negative bias temperature stress tests, critical for assessing the operational stability of a TFT technology (8). Here, to avoid confusion between biasing conditions for n- or p-type TFTs, we refer to these tests as on- and off-state temperature stress tests. Figure 2 (C and D) shows ΔVTH and |ΔVTH| measured in the dark on as-fabricated A_33 devices during on-state (VDS = VGS = −10 V) and off-state (VDS = 0 V, VGS = 10 V) bias-temperature stress tests for 1 hour, respectively. Figure S10 shows the transfer characteristics measured during these tests, which reveal that an increase in temperature more prominently results in increased off-current values that can be attributed to an increased gate dielectric leakage current, as shown in fig. S11. However, smaller changes of VTH can also be observed even after the temperature is increased by ca. 50°C, and |ΔVTH(1 hour)| is less than 0.07 V during on-state temperature stress tests and smaller than 0.2 V during off-state temperature stress tests. Measured ΔVTH(t) values during on- and off-state temperature stress tests were also fitted using the DSE model and extrapolated to a stress time of over 10 years, as shown in the insets of Fig. 2 (C and D). Table S5 displays values of parameters used in these fits. At 27°C, the values of parameters τi and m are slightly smaller than those found on previous IDS bias stress effect studies. We attribute these differences to the different experimental procedures used to measure temporal IDS changes and that used to derive ΔVTH(t) in bias stress tests, in one case by modeling IDS changes during continuous bias stress and in the other one by suspending the bias stress to measure changes in the transfer characteristics by sweeping the gate voltage from the positive to negative and then back to positive voltages. To illustrate the second process, fig. S12 shows the temporal IDS changes, including the interruptions to measure the transfer characteristics. This method produces predominantly negative VTH(t) shifts after measurement of the transfer characteristics and leads to IDS characteristics over time that are qualitatively different from those measured during constant bias stress. Furthermore, it should be pointed out that these small ΔVTH(t) values are also related to a device’s bias-stress history, as shown in fig. S13 for another batch of A_33 devices and for C_33 devices. With this in mind, although it is clear that at this point further systematic studies would be necessary to derive the physical insights that allow rationalizing the thermal dependence of |ΔVTH|, it is also clear that regardless of bias condition or device history, |ΔVTH| in all devices tested remains less than 0.15 V during on-state stress tests for 1 hour. Hence, the |ΔVTH| values during on-state stress tests measured in A_33 and C_33 μc-OTFTs are around the same order of magnitude with the ones displayed by state-of-the-art a-oxide TFTs (for example, |ΔVTH| > 0.01 V during on-state stress tests at 70°C for 1 hour) (30).

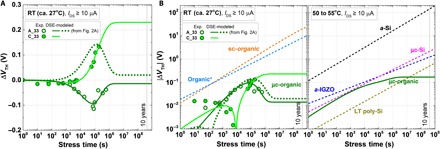

Finally, we carried out independent long-term on-bias stress tests (VDS = VGS = −10 V) at RT (ca. 27°C) on pristine A_33 and C_33 μc-OTFTs. The transfer characteristics measured during these tests are shown in fig. S7 and reveal only very small changes. Table S2 provides a comparison of the electrical parameters (that is, μ, VTH, |S|, and current on/off ratio) derived from these transfer characteristics before and after stress tests. After stress, the values of μ, VTH, and |S| are changed by less than 3%. Figure 3A shows measured ΔVTH values as well as the DSE-modeled values extrapolated to a stress time of over 10 years. The values of the fitting parameters are shown in table S6. In addition, Fig. 3A shows the DSE-modeled ΔVTH values derived from fits to the experimental data in Fig. 2A. These results demonstrate that good consistency is obtained within one order of magnitude between the ΔVTH values measured on different batches of devices, with different organic semiconductor layers and using slightly different experimental methods. The left panel of Fig. 3B shows the experimental |ΔVTH| values of A_33 and C_33 μc-OTFTs in a log-log scale with fitted curves from Fig. 3A and, for comparison, extrapolated SSE-modeled |ΔVTH| derived for organic single-crystal N,N′-bis(n-alkyl)-(1,7 and 1,6)-dicyanoperylene-3,4:9,10-bis(dicarboximide)s (PDIF-CN2) (sc-PDIF-CN2) TFTs (14) and the state-of-the-art OTFTs using indacenodithiophene-co-benzothiadiazole (IDTBT) with tetrafluoro-tetracyanoquinodimethane (F4TCNQ) molecular additives (19). Even considering device-to-device variations, |ΔVTH| values measured in all μc-OTFTs are at least an order of magnitude smaller than those expected from sc-organic FETs or the state-of-the-art OTFTs with molecular additives. Furthermore, the right panel of Fig. 3B shows a comparison of the DSE-modeled |ΔVTH| values derived from fits to the experimental data at 55°C displayed in Fig. 2C for our μc-OTFTs, with SSE-modeled |ΔVTH| values for other commercial TFT technologies at 50°C [IDS ≥ 10 μA; for self-consistency, taken from the study of Arai and Sasaoka (26)]. We recognize that direct benchmarking of our results to conventional inorganic TFT technologies is challenged by the lack of detailed stability reports on widely used commercial products in the scientific literature. Hence, comparison can only be made to previously published results generated in an academic environment, but it may not necessarily constitute a fair direct comparison to the state-of-the-art today for mature commercial technologies.

Fig. 3. Long-term stability comparison in different TFT technologies.

(A) RT measured ΔVTH under on-state bias stress tests of A_33 and C_33 at VDS = VGS = −10 V with fitted curves using a DSE model. (B) Left: RT measured |ΔVTH| under on-state bias stress tests of A_33 and C_33 at VDS = VGS = −10 V with fitted curves from (A). ”*” represents the blue dashed data that are from the state-of-the-art OTFT showing the highest stability by using IDTBT with F4TCNQ molecular additives (19). The orange dashed data are from the sc-organic FET with remarkable stability (14). Right: Comparison between DSE-modeled |ΔVTH| at 55°C for μc-OTFTs and SSE-modeled |ΔVTH| at 50°C for commercial TFT technologies (26).

DISCUSSION

In summary, we have demonstrated an effective approach to realize solution-processed top-gate μc-OTFTs that have an engineered bilayer gate dielectric comprising a CYTOP layer and an NL layer fabricated by ALD. These μc-OTFTs, processed at temperatures below 110°C, display improved environmental stability (particular under aqueous environments) when compared to previously reported μc-OTFTs and an unprecedented level of operational (VTH) stability, superior to values reported in the scientific literature for a-Si TFTs and comparable to other commercial TFT technologies. Although it is clear that further studies will be necessary to improve our understanding of the physical mechanisms giving rise to the temporal and thermal dependence of the ΔVTH observed, we have shown here that the metal oxide layer thickness can be effectively used to tailor these effects and that the temporal dynamics of ΔVTH can be modeled by two competing processes that appear to display similar dynamics and magnitude in bilayers of CYTOP and Al2O3:HfO2 NL. These results suggest that μc-OTFTs can achieve the level of performance of commercial inorganic semiconductor-based TFT technologies. In addition, we believe that using a similar approach could further benefit the operational stability of such TFT technologies. Note that the stability studies reported here were carried out with prolonged continuous bias conditions. In many applications such as backplane technology for displays, the devices operate most of the time in a pulsed mode with bias voltages with alternating polarity. Bias conditions are likely to further influence the overall stability, and therefore, it would be useful to conduct further studies for a given application with specific conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Device fabrication

All the μc-OTFT devices with CYTOP/ALD-oxide bilayer gate dielectrics were fabricated on glass substrates (Corning Eagle XG), which were cleaned by sonication in acetone, deionized water, and isopropanol for 5 min for each step beforehand. Fifty-nanometer-thick source and drain electrodes of Ag were deposited on the substrates through shadow masks, using a Kurt J. Lesker SPECTROS thermal evaporator at a deposition rate of 1 Å s−1 under 5 × 10−7 torr at RT. To form a self-assembled monolayer of pentafluorobenzenthiol (PFBT) on Ag electrodes, we immersed the substrates with sources and drain electrodes into a 10 mM PFBT solution in ethanol for 15 min and then rinsed them in pure ethanol for 1 min followed by annealing at 60°C on a hot plate for 5 min in a N2-filled glove box in devices with a channel length of 180 μm. In the devices with a shorter channel length (85 μm), the electrodes were coated with a 10-nm-thick evaporated MoOx layer to further increase charge injection and reduce contact resistance. To prepare the solution for the organic semiconductor layer, we dissolved a 1:1 weight ratio of PTAA (Sigma-Aldrich) and TIPS-pentacene (Sigma-Aldrich) or diF-TES-ADT (Lumtec) blend in 1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene (anhydrous, 99%) (Tetralin; Sigma-Aldrich) for a concentration of 30 mg ml−1. A 70-nm-thick active semiconducting layer was deposited by spin-coating TIPS-pentacene/PTAA or diF-TES-ADT/PTAA solution (filtered with a 0.2-μm filter) at 500 rpm for 10 s with 500 rpm s−1 acceleration and 2000 rpm for 20 s with 1000 rpm s−1 acceleration, followed by annealing at 100°C on a hot plate for 15 min in a N2-filled glove box. The as-purchased 9 weight % (wt %) CYTOP (Asahi Glass, CTL-890M) was diluted with the solvent CT-SOLV180 (Asahi Glass) in a 1:3.5 volume ratio to have a 2 wt % CYTOP, which was spin-coated on top of the semiconductor layer at 3000 rpm for 60 s with 10,000 rpm s−1 acceleration, followed by annealing at 100°C for 10 min on a hot plate in a N2-filled glove box. The final thickness of CYTOP film was 35 nm. For samples A_33, C_33, A_27, and A_22, after CYTOP deposition, an Al2O3-HfO2 NL was deposited in a Savannah 100 ALD system from Cambridge NanoTech by alternating five cycles of Al2O3 and five cycles of HfO2 for 30 times (A_33 and C_33), 25 times (A_27), and 20 times (A_22) at 110°C, producing films of 33, 27.5, and 22 nm, respectively. For samples B_44, B_22, and B_11, a 20-nm-thick Al2O3 film was deposited as a nucleation layer, followed by depositing an Al2O3-HfO2 NL at 110°C. The NL films were deposited by alternating five cycles of Al2O3 and five cycles of HfO2 for 40 times (B_44), 20 times (B_22), and 10 times (B_11), producing films of 44, 22, and 22 nm, respectively. Finally, 100-nm-thick gate electrodes of Ag were deposited on the substrates through a shadow mask, using a Kurt J. Lesker SPECTROS thermal evaporator at a deposition rate of 1 Å s−1 at a base pressure of <5 × 10−7 torr at RT.

Electrical characterization

All the μc-OTFT devices were characterized using an Agilent E5272A source/monitor unit at RT inside a N2-filled glove box, in which both O2 and H2O values were maintained below 0.1 parts per million to avoid ambient humidity and oxygen. The capacitance densities of gate dielectrics were extracted by measuring and linear-fitting the capacitance values of the capacitors having six different areas using a precision inductance-capacitance-resistance (LCR) meter (Agilent 4284A). The dielectric constant values were 2.0 for CYTOP and 8.9 for Al2O3, which were previously reported (20, 31, 32). The extracted dielectric constant value of Al2O3-HfO2 NL was around 10.5. The capacitance density of the gate dielectric for each sample shown in table S1 was close to the theoretical value estimated from series-connected capacitors of stacked dielectric layers.

Environmental reliability characterization

To investigate the environmental reliability of μc-OTFT devices, A_33, C_33, and B_44 were exposed to different conditions as follows: air with an RH of 35% for 1 day, immersion in distilled water for 16 hours, and vacuum annealing at 100°C for 16 hours. At each interval, each sample was briefly transferred back into a N2-filled glove box, and the dc-bias stress reliability was tested immediately.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported in part by the Center for Organic Photonics and Electronics at the Georgia Institute of Technology, by the Department of the Navy Office of Naval Research award nos. N00014-14-1-0580 and N00014-16-1-2520 through the Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative Center for Advanced Organic Photovoltaics, by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research through award no. FA9550-16-1-0168, and by the National Nuclear Security Administration award no. DE-NA0002576 through the Consortium for Nonproliferation Enabling Technologies. Seminal work on the concept of using a bilayer gate dielectric in OFETs was funded in part by Solvay S.A. and described in part in issued patent no. US 9,368,737 B2. Author contributions: X.J., C.F.-H., C.-Y.W., and B.K. conceived and developed the ideas. X.J. and C.F.-H. designed the experiments. X.J. and Y.P. performed the device fabrication and electrical characterization. X.J. performed stability experiments. C.F.-H. and X.J. refined the DSE model. C.F.-H. and B.K. coordinated and directed the study. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. Competing interests: C.F.-H. and B.K. are inventors on a U.S. patent related to this work (U.S. patent no. 9,368,737, issued 14 June 2016). X.J., C.F.-H., and B.K. are inventors on a provisional patent application filed by Georgia Institute of Technology also related to this work (application no. 62/586,337, filed 15 November 2017). The other authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/1/eaao1705/DC1

section S1. Electrical properties of μc-OTFTs with different thicknesses of NL

section S2. Environmental stability

section S3. One-hour operational stability

section S4. Long-term operational stability

section S5. Analytic models of bias stress effects

section S6. Operational stability of short-channel devices

section S7. Temperature stability

section S8. Bias stress effects with different experimental procedures and device bias stress history

fig. S1. General electrical properties of μc-OTFTs with different configurations of gate dielectric layers.

fig. S2. Current density–electric field (J-E) characteristics of dielectric layers.

fig. S3. Environmental stability of μc-OTFTs with different configurations of gate dielectric layers.

fig. S4. One-hour operational stability of μc-OTFTs.

fig. S5. One-hour operational stability of μc-OTFTs using a CYTOP/HfO2 dielectric.

fig. S6. Long-term operational stability of μc-OTFTs.

fig. S7. Transfer characteristics of μc-OTFTs during long-term operational stability tests.

fig. S8. Simulation of ΔVTH and the corresponding two opposite contributions of ΔVTH,1 and ΔVTH,2 of μc-OTFTs during dc-bias stress using the DSE model.

fig. S9. dc-bias stress test of short-channel μc-OTFTs.

fig. S10. Transfer curves of μc-OTFTs during dc-bias stress at different temperatures.

fig. S11. Current density–electric field (J-E) characteristics of dielectric layers for A_33 at different temperatures.

fig. S12. Temporal dynamic of IDS, including interruptions to measure the transfer characteristics, during 47-hour dc-bias stress at VDS = VGS = −10 V at RT.

fig. S13. VTH shifts of A_33 and C_33 devices that were tested after long-term operational and environmental stability tests.

table S1. Summary of the device properties and pristine electrical performance.

table S2. Summary of the device electrical parameters before and after stress tests.

table S3. Summary of lifetime parameters of TFTs using the SSE model.

table S4. Summary of lifetime parameters of μc-OTFTs using the DSE model.

table S5. Summary of μc-OTFTs lifetime parameters at different temperatures using the DSE model.

table S6. Summary of lifetime parameters of μc-OTFTs extracted from VTH shifts using the DSE model.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Nathan A., Lee S., Jeon S., Robertson J., Amorphous oxide semiconductor TFTs for displays and imaging. J. Disp. Technol. 10, 917–927 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan A., Kumar A., Sakariya K., Servati P., Sambandan S., Striakhilev D., Amorphous silicon thin film transistor circuit integration for organic LED displays on glass and plastic. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 39, 1477–1486 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheraw C. D., Zhou L., Huang J. R., Gundlach D. J., Jackson T. N., Organic thin-film transistor-driven polymer-dispersed liquid crystal displays on flexible polymeric substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 1088–1090 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myny K., Steudel S., Smout S., Vicca P., Furthner F., van der Putten B., Tripathi A. K., Gelinck G. H., Genoe J., Dehaene W., Heremans P., Organic RFID transponder chip with data rate compatible with electronic product coding. Org. Electron. 11, 1176–1179 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yun M., Sharma A., Fuentes-Hernandez C., Hwang D. K., Dindar A., Singh S., Choi S., Kippelen B., Stable organic field-effect transistors for continuous and nondestructive sensing of chemical and biologically relevant molecules in aqueous environment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 1616–1622 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Someya T., Sekitani T., Iba S., Kato Y., Kawaguchi H., Sakurai T., A large-area, flexible pressure sensor matrix with organic field-effect transistors for artificial skin applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9966–9970 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts M. E., Mannsfeld S. C. B., Queraltó N., Reese C., Locklin J., Knoll W., Bao Z., Water-stable organic transistors and their application in chemical and biological sensors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12134–12139 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deane S. C., Wehrspohn R. B., Powell M. J., Unification of the time and temperature dependence of dangling-bond-defect creation and removal in amorphous-silicon thin-film transistors. Phys. Rev. B 58, 12625–12628 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libsch F. R., Kanicki J., Bias-stress-induced stretched-exponential time dependence of charge injection and trapping in amorphous thin-film transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 62, 1286–1288 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi B. G., Kim K.-T., Bae J. H., Lee S., Lee H. K., Kim S. K., Park K.-S., Kim C.-D., Hwang Y. K., Chung I.-J., High performance micro-crystalline silicon TFT using indirect thermal crystallization technique. ECS Trans. 33, 213–216 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 11.S. Xu, Z. Sun, D. Zhang, M. Wang, Reliability of low-temperature polysilicon thin-film transistors for flexible electronics application, in 2016 IEEE International Nanoelectronics Conference (INEC’16) (IEEE, 2016), pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C.-Y., Fuentes-Hernandez C., Yun M., Singh A., Dindar A., Choi S., Graham S., Kippelen B., Organic field-effect transistors with a bilayer gate dielectric comprising an oxide nanolaminate grown by atomic layer deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 29872–29876 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang D. K., Fuentes-Hernandez C., Fenoll M., Yun M., Park J., Shim J. W., Knauer K. A., Dindar A., Kim H., Kim Y., Kim J., Cheun H., Payne M. M., Graham S., Im S., Anthony J. E., Kippelen B., Systematic reliability study of top-gate p- and n-channel organic field-effect transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 3378–3386 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barra M., Di Girolamo F. V., Minder N. A., Gutiérrez Lezama I., Chen Z., Facchetti A., Morpurgo A. F., Cassinese A., Very low bias stress in n-type organic single-crystal transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 133301 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C.-Y., Fuentes-Hernandez C., Chou W.-F., Kippelen B., Top-gate organic field-effect transistors fabricated on paper with high operational stability. Org. Electron. 41, 340–344 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y., Sonar P., Murphy L., Hong W., High mobility diketopyrrolopyrrole (DPP)-based organic semiconductor materials for organic thin film transistors and photovoltaics. Energ. Environ. Sci. 6, 1684–1710 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tseng H.-R., Phan H., Luo C., Wang M., Perez L. A., Patel S. N., Ying L., Kramer E. J., Nguyen T.-Q., Bazan G. C., Heeger A. J., High-mobility field-effect transistors fabricated with macroscopic aligned semiconducting polymers. Adv. Mater. 26, 2993–2998 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yi Z., Wang S., Liu Y., Design of high-mobility diketopyrrolopyrrole-based π-conjugated copolymers for organic thin-film transistors. Adv. Mater. 27, 3589–3606 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikolka M., Nasrallah I., Rose B., Ravva M. K., Broch K., Sadhanala A., Harkin D., Charmet J., Hurhangee M., Brown A., Illig S., Too P., Jongman J., McCulloch I., Bredas J.-L., Sirringhaus H., High operational and environmental stability of high-mobility conjugated polymer field-effect transistors through the use of molecular additives. Nat. Mater. 16, 356–362 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang D. K., Fuentes-Hernandez C., Kim J., Potscavage W. J. Jr, Kim S.-J., Kippelen B., Top-gate organic field-effect transistors with high environmental and operational stability. Adv. Mater. 23, 1293–1298 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee B., Wan A., Mastrogiovanni D., Anthony J. E., Garfunkel E., Podzorov V., Origin of the bias stress instability in single-crystal organic field-effect transistors. Phys. Rev. B 82, 085302 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bae J.-H., Park J., Keum C.-M., Kim W.-H., Kim M.-H., Kim S.-O., Kwon S. K., Lee S.-D., Thermal annealing effect on the crack development and the stability of 6,13-bis(triisopropylsilylethynyl)-pentacene field-effect transistors with a solution-processed polymer insulator. Org. Electron. 11, 784–788 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C.-Y., Fuentes-Hernandez C., Liu J.-C., Dindar A., Choi S., Youngblood J. P., Moon R. J., Kippelen B., Stable low-voltage operation top-gate organic field-effect transistors on cellulose nanocrystal substrates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 4804–4808 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalb W. L., Mathis T., Haas S., Stassen A. F., Batlogg B., Organic small molecule field-effect transistors with Cytop™ gate dielectric: Eliminating gate bias stress effects. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 092104 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bisoyi S., Zschieschang U., Kang M. J., Takimiya K., Klauk H., Tiwari S. P., Bias-stress stability of low-voltage p-channel and n-channel organic thin-film transistors on flexible plastic substrates. Org. Electron. 15, 3173–3182 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arai T., Sasaoka T., 49.1: Invited paper: Emergent oxide TFT technologies for next-generation AM-OLED displays. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 42, 710–713 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hwang D. K., Dasari R. R., Fenoll M., Alain-Rizzo V., Dindar A., Shim J. W., Deb N., Fuentes-Hernandez C., Barlow S., Bucknall D. G., Audebert P., Marder S. R., Kippelen B., Stable solution-processed molecular n-channel organic field-effect transistors. Adv. Mater. 24, 4445–4450 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukuda K., Suzuki T., Kobayashi T., Kumaki D., Tokito S., Suppression of threshold voltage shifts in organic thin-film transistors with bilayer gate dielectrics. Phys. Stat. Sol. (A) 210, 839–844 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathijssen S. G. J., Cölle M., Gomes H., Smits E. C. P., de Boer B., McCulloch I., Bobbert P. A., de Leeuw D. M., Dynamics of threshold voltage shifts in organic and amorphous silicon field-effect transistors. Adv. Mater. 19, 2785–2789 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu E. K.-H., Abe K., Kumomi H., Kanicki J., AC bias-temperature stability of a-InGaZnO thin-film transistors with metal source/drain recessed electrodes. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 61, 806–812 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X.-H., Potscavage W. J. Jr, Choi S., Kippelen B., Low-voltage flexible organic complementary inverters with high noise margin and high dc gain. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 043312 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton R., Smith J., Ogier S., Heeney M., Anthony J. E., McCulloch I., Veres J., Bradley D. D. C., Anthopoulos T. D., High-performance polymer-small molecule blend organic transistors. Adv. Mater. 21, 1166–1171 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDowell M., Hill I. G., McDermott J. E., Bernasek S. L., Schwartz J., Improved organic thin-film transistor performance using novel self-assembled monolayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 073505 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams G., Watts D. C., Dev S. B., North A. M., Further considerations of non symmetrical dielectric relaxation behaviour arising from a simple empirical decay function. Trans. Faraday Soc. 67, 1323–1335 (1971). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/1/eaao1705/DC1

section S1. Electrical properties of μc-OTFTs with different thicknesses of NL

section S2. Environmental stability

section S3. One-hour operational stability

section S4. Long-term operational stability

section S5. Analytic models of bias stress effects

section S6. Operational stability of short-channel devices

section S7. Temperature stability

section S8. Bias stress effects with different experimental procedures and device bias stress history

fig. S1. General electrical properties of μc-OTFTs with different configurations of gate dielectric layers.

fig. S2. Current density–electric field (J-E) characteristics of dielectric layers.

fig. S3. Environmental stability of μc-OTFTs with different configurations of gate dielectric layers.

fig. S4. One-hour operational stability of μc-OTFTs.

fig. S5. One-hour operational stability of μc-OTFTs using a CYTOP/HfO2 dielectric.

fig. S6. Long-term operational stability of μc-OTFTs.

fig. S7. Transfer characteristics of μc-OTFTs during long-term operational stability tests.

fig. S8. Simulation of ΔVTH and the corresponding two opposite contributions of ΔVTH,1 and ΔVTH,2 of μc-OTFTs during dc-bias stress using the DSE model.

fig. S9. dc-bias stress test of short-channel μc-OTFTs.

fig. S10. Transfer curves of μc-OTFTs during dc-bias stress at different temperatures.

fig. S11. Current density–electric field (J-E) characteristics of dielectric layers for A_33 at different temperatures.

fig. S12. Temporal dynamic of IDS, including interruptions to measure the transfer characteristics, during 47-hour dc-bias stress at VDS = VGS = −10 V at RT.

fig. S13. VTH shifts of A_33 and C_33 devices that were tested after long-term operational and environmental stability tests.

table S1. Summary of the device properties and pristine electrical performance.

table S2. Summary of the device electrical parameters before and after stress tests.

table S3. Summary of lifetime parameters of TFTs using the SSE model.

table S4. Summary of lifetime parameters of μc-OTFTs using the DSE model.

table S5. Summary of μc-OTFTs lifetime parameters at different temperatures using the DSE model.

table S6. Summary of lifetime parameters of μc-OTFTs extracted from VTH shifts using the DSE model.