Abstract

Background

With published evidence-based Standards for Psychosocial Care for Children with Cancer and their Families, it is important to know the current status of their implementation. This paper presents data on delivery of psychosocial care related to the Standards in the United States (U.S.).

Procedure

Pediatric oncologists, psychosocial leaders, and administrators in pediatric oncology from 144 programs completed an online survey. Participants reported on the extent to which psychosocial care consistent with the Standards was implemented and was comprehensive and state of the art. They also reported on specific practices and services for each Standard and the extent to which psychosocial care was integrated into broader medical care.

Results

Participants indicated that psychosocial care consistent with the Standards was usually or always provided at their center for most of the Standards. However, only half of the oncologists (55.6%) and psychosocial leaders (45.6%) agreed or strongly agreed that their psychosocial care was comprehensive and state of the art. Types of psychosocial care provided included evidence based and less established approaches but were most often provided when problems were identified, rather than proactively. The perception of state of the art care was associated with practices indicative of integrated psychosocial care and the extent to which the Standards are currently implemented.

Conclusion

Many oncologists and psychosocial leaders perceive that the delivery of psychosocial care at their center is consistent with the Standards. However, care is quite variable, with evidence for the value of more integrated models of psychosocial services.

Keywords: pediatric oncology, psychosocial, standards of care

Introduction

Providing comprehensive pediatric cancer care necessitates psychosocial support and services for children and families from the time of diagnosis, throughout treatment and into survivorship or bereavement1, 2, 3. The multidisciplinary Psychosocial Standards of Care Project for Childhood Cancer (PSCPCC), consisting of more than 80 oncology professionals and parent advocates, and supported by the Mattie Miracle Foundation (www.mattiemiracle.com), developed a set of 15 evidence-based Standards for Psychosocial Care for Children with Cancer and Their Families4 that are endorsed by key professional organizations. The first fourteena cover the following aspects of clinical care: Assessment of psychosocial healthcare needs (PSS1)5; Monitoring of neuropsychological deficits (PSS2)6; Screening in long-term survivorship (PSS3)7; Psychosocial support and interventions (PSS4)8; Assessment of financial need (PSS5)9; Parental mental health (PSS6)10; Psychoeducation, information and anticipatory guidance (PSS7)11; Preparatory information for procedures (PSS8)12; Opportunities for social interaction (PSS9)13; Sibling support (PSS10)14; School support (PSS11)15; Facilitating Adherence to Treatment (PSS12)16; Palliative care/end of life care (PSS13)17; and Bereavement Care (PSS14)18. The full set of Standards is included as Supplementary Material S1.

Each Standard is supported by a rigorous systematic literature review, evaluating the study rigor and including an independent appraisal of the body of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system4. Collectively, the Standards are a strong body of evidence for a broad array of psychosocial care. The question of how the Standards are being implemented is currently unknown.

To advance the implementation of the Standards, it is important to know the extent to which specialized psychosocial staff members are available at pediatric cancer programs. Scialla et al.19 provide data showing that in the U.S., while over 90% of programs have social workers and child life specialists, fewer have psychologists (60%), neuropsychologists (31%) or psychiatrists (19%). Not surprisingly, larger programs have larger psychosocial teams, a finding that is consistent with an earlier survey of Children’s Oncology Group (COG) sites.20

However, size is only one potential marker of quality. Selove et al20 reported variability in the delivery of psychosocial care and noted that “most sites do not use validated assessment tools or evidence-based psychosocial interventions.”20(p.435) As described in Scialla, et al19, psychosocial care practices (e.g. the timing of initiation of care) and psychosocial service delivery practices (e.g. attending and participating in medical rounds, meeting as a psychosocial team) did not vary by program size. Although not previously investigated, psychosocial service delivery models that promote the integration of psychosocial staff within the broader pediatric oncology program may facilitate high quality care consistent with the Standards.

This paper describes how pediatric oncology treatment programs in the United States are providing psychosocial care consistent with the Standards, and details the approaches utilized. Additionally, this paper explores factors contributing to team leadership perceptions of the quality of psychosocial care provided at their center.

Method

Study Design, Sample and Recruitment

A national survey open to all pediatric oncology treatment programs in the United States (n = 200) - Preparing to Implement Psychosocial Standards: Current Services and Staffing (PIPS-CSS) - was conducted from June to December 2016. Details of the study methodology are available in Scialla et al19. Independent assessments from up to three specific oncology professionals (one per discipline) with leadership roles at each program – a pediatric oncologist (Medical Director/Clinical Director), a psychosocial leader (Director of Psychosocial Services/staff member with most seniority), and an administrator (Administrative Director/Business Administrator/Director of Operations) were included.

Survey Instrument

The survey (available as Supplementary Material S2) was written by the Principal Investigator (AEK) and reviewed by the Leadership Team of the PSCPCC, three pediatric oncologists and two parent advocates. The survey was refined based on review by faculty with expertise in survey research methods, psychosocial care, and/or pediatric oncology, as well an experienced nurse site coordinator. The study team further refined the survey, and subsequent revisions to the questionnaire were reviewed by a psychologist, social workers, an oncology administrator, child psychiatrist and child life specialist. The survey was pilot tested for usability, technical functionality, clarity of items and length.

Measures

Size

The number of new patients in 2015 was obtained on the survey from administrators. In some cases (n = 47), these data were provided by an oncologist or psychosocial staff member. The size of the psychosocial team was provided by the psychosocial leader and calculated by summing the number of full time equivalent social workers, child life specialists, psychologists, neuropsychologists and psychiatrists at each site.

Implementation of the Standards

Both psychosocial providers and oncologists (one of each per site) answered a question for each Standard that asked about the extent to which the Standard was met on a five-point scale, from Never (1) to Always (5). For each participant, a total sum Implementation score (14–70) was calculated representing the extent to which the 14 Standards are implemented.

Overall quality of care

Both psychosocial providers and oncologists responded to an item about the overall quality of psychosocial care (“The psychosocial care that pediatric cancer patients/families receive in our program is comprehensive and “state of the art.”) on a five-point scale from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5).

Approaches used and timing of care

Psychosocial staff indicated specific approaches that were used to meet each standard. They could check all responses that applied (e.g., structured interview, questionnaire). For most of the Standards they also indicated when the services were provided (e.g. at diagnosis, within the first week). These follow-up questions were presented to all psychosocial leaders, and were not dependent on responses to previous survey items.

Psychosocial Service Delivery/Integration of Psychosocial Care

This section included eight questions related to practices of the psychosocial staff and the extent of their integration into the broader oncology team: regular attendance at medical rounds and patient care conferences, documentation in the electronic health or medical record, attendance at oncology journal clubs and tumor boards, providing consultation and training to other team members, meeting regularly as a psychosocial team, and holding psychosocial rounds for all staff focused on psychosocial concerns. Both psychosocial providers and oncologists answered these questions. For each, a total sum Integration score (0–8) was calculated indicating extent of integration into broader oncology care.

Data Analysis

Survey responses were collected and maintained in REDCap21 and imported into SPSS (version 24; IBM SPSS Statistics). Data for items describing the frequency of care provided consistent with the Standards were first analyzed descriptively. Differences in these outcomes based on discipline of the respondent (oncologists and psychosocial leaders) were tested using Mann-Whitney U. Multiple regression was conducted to examine factors that were associated with quality of care. The outcome variable was perceptions of “comprehensive and state of the art” psychosocial care. Predictors were the Integration and Implementation scores, number of new patients in 2015 and size of the psychosocial team.

Results

Participants

Participants were oncologists (n = 99) psychosocial leaders (n = 132) and administrators (n=58) representing 144 pediatric oncology treatment programs from 44 states and the District of Columbia, with an institutional response rate of 72%. Each participating program could contribute only one participant per discipline. Most participants identified as White (non-Hispanic) (84.1%) and female (70.9%). A detailed table of participant information is available in Scialla, et al19. Eighty-three (59.3%) programs returned data from both an oncologist and a psychosocial leader.

Implementation: Providing care consistent with each Standard

Psychosocial leaders and oncologists rated the frequency with which care consistent with each Standard was provided. The mean frequencies across the Standards ranged from 3.17 to 4.74 on a 1 (never) to 5 (always) scale (Table 1). The Standards that participants indicated were usually or always met were PSS1 (assessment of psychosocial healthcare needs), PSS4 (psychosocial support), PSS5 (assessment of factors related to access to care), psychoeducation and education (PSS7), and developmentally appropriate end of life care (PSS13). Those rated as occurring relatively less frequently were PSS13 (integration of palliative care) and PSS10 (provision of sibling support).

TABLE 1.

Mean frequency of care/service provision

| Standard | Mean (1 – 5 scale) | |

|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial leaders (n=132) |

Oncologists (n=99) |

|

| PSS1: Assessment of psychosocial healthcare needs | 4.66 | 4.58 |

| PSS2: Monitoring of neurocognitive problems | 4.15 | 4.15 |

| PSS3: Screening in long-term survivorship | 3.98 | 4.05 |

| PSS4: Psychosocial support and intervention | 4.59 | 4.46 |

| PSS5: Assessment of financial need (at diagnosis) | 4.50 | 4.43 |

| PSS5: Assessment of financial need (ongoing)1 | 4.18 | 3.91 |

| PSS5: Assessment factors ‥ access to care (initial) | 4.74 | 4.60 |

| PSS5: Assessment factors ‥ access to care (ongoing)2 | 4.46 | 4.11 |

| PSS6: Parental mental health | 4.33 | 4.11 |

| PSS7: Psychoeducation, information, anticipatory guidance3 | 4.58 | 4.11 |

| PSS8: Preparatory information about invasive procedures | 4.19 | 4.09 |

| PSS8: Psychosocial interventions for invasive procedures | 3.88 | 3.88 |

| PSS9: Opportunities for social interaction4 | 3.82 | 4.12 |

| PSS10: Psychosocial support and interventions for siblings | 3.61 | 3.69 |

| PSS11: Support for school re-entry | 4.25 | 4.34 |

| PSS12: Adherence to treatment is assessed and monitored | 4.39 | 4.49 |

| PSS13: Palliative care concepts throughout disease process | 3.17 | 3.21 |

| PSS13: Developmentally appropriate end of life care | 4.61 | 4.51 |

| PSS14: Psychosocial care after a child’s death | 3.79 | 4.00 |

Note: Reported p values for the Mann-Whitney U test comparison of means

p = .041

p = .002

p = .000

p = .006

Oncologists and psychosocial leaders were quite similar in their ratings and both indicated that psychosocial care consistent with the Standards was provided at their center either usually or always. However, psychosocial leaders indicated that ongoing assessment of financial need and access to care (PSS5) occurs more frequently than the oncologists reported (p’s = .05, .002, respectively) and that psychoeducation, information and anticipatory guidance (PSS7) is provided more frequently than the oncologists indicated (p <.001). However, oncologists indicated that opportunities for social interaction (PSS9) are provided more often than psychosocial leaders (p = .006).

Specific care provided for each Standard

Seven of the Standards were grouped into three clinically logical sets (Tables 2 – 4). The other seven are discussed individually in the text.

TABLE 2.

| Standard | Care Delivery (%) 4 | When is care provided (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSS1: Youth with cancer and their family members should routinely receive systematic assessments of their psychosocial health care needs | Informal Discussion | 81.3 | When a problem is identified | 93.2 |

| Structured Interview | 66.1 | At diagnosis | 71.2 | |

| Psychosocial Assessment Tool | 28.8 | First week after diagnosis | 62.7 | |

| Distress Thermometer | 13.6 | Within the first month after diagnosis | 54.2 | |

| Also mentioned were institution specific tools used by social workers and standardized measures of child and family functioning, not specific to cancer. | At every inpatient admission | 57.6 | ||

| At every clinic visit | 24.6 | |||

| At end of treatment | 42.4 | |||

| At survivorship visits | 54.2 | |||

|

| ||||

| PSS4: Youth with cancer and their family members should have access to psychosocial support and interventions throughout the cancer trajectory and access to psychiatry as needed | Informal discussion | 98.3 | When a problem was identified | 97.4 |

| Supportive psychotherapy | 83.6 | At diagnosis | 72.4 | |

| Support Groups | 43.1 | First week of treatment | 72.4 | |

| Family therapy | 49 | First month after diagnosis | 62.9 | |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | 69 | Every admission | 60.3 | |

| Problem Solving Skills Training | 43.1 | Every clinic visit | 36.2 | |

| Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program | 7.8 | At end of treatment | 47.4 | |

| Psychotropic medication | 58.6 | Survivorship visits | 54.3 | |

|

| ||||

| PSS6: Parents and caregivers of children with cancer should have early and ongoing assessment of their mental health needs | Informal Discussion | 98.2 | When a problem is identified | 96.5 |

| Referral to therapist in the community | 93.9 | At diagnosis | 74.6 | |

| Referral to psychiatrist in the community | 74.6 | First week after diagnosis | 69.3 | |

| Supportive psychotherapy | 70.2 | Within the first month after diagnosis | 64.9 | |

| Every inpatient admission | 50.9 | |||

| Survivorship visits | 40.4 | |||

| At end of treatment | 39.5 | |||

| Every clinic visit | 32.5 | |||

Based on respondents answering each question. n’s ranged from 113–118.

Responses allowed for multiple answers (“check all that apply”)

TABLE 4.

| Standard | Care Delivery | % |

|---|---|---|

| PSS2: Patients with brain tumors and others at high risk for neuropsychological deficits … should be monitored for neuropsychological deficits during and after treatment | Referral to a Neuropsychologist | 84.5 |

| Informal Discussion | 77.6 | |

| Brief Neurocognitive Screen | 30.2 | |

| When is this care delivered? | ||

| When a problem was identified | 87.9 | |

| At survivorship visits | 53.4 | |

| At the end of treatment | 50.0 | |

|

| ||

| PSS12: Adherence should be assessed routinely and monitored throughout treatment | Ask the patient | 96.4 |

| Ask family members | 69.0 | |

| Self-report measures/patients | 80.5 | |

| Self-report measures/parents | 79.6 | |

| Self-report measures/staff | 72.6 | |

| Blood test | 40.7 | |

| Monitoring Systems (MEMS) or similar | 4.4 | |

Based on respondents answering each question. n’s ranged from 113–118.

Responses allowed for multiple answers (“check all that apply”)

Core psychosocial services at diagnosis and during treatment

Table 2 presents three Standards (PSS 1, 4, 6) focused on the delivery of care to families during diagnosis and treatment phases - psychosocial assessment, interventions for patients, and parental mental health assessments. Informal discussion was endorsed as the most frequently used approach (81.3–98.3%) for each of these Standards. Evidence-based approaches were also used, including validated screeners such as the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT22) in 28.8%, the Distress Thermometer23, 24 in 13.6%; Problem Solving Skills Training25 for 43.1% of centers, Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program (SCCIP26; SCCIP-ND27) for 7.8% as well as other standardized measures and approaches.. Referrals for further treatment for parents/caregivers was the general treatment approach in 93.9% of sites for the Standard related to parental mental health (PSS6).

In terms of when care was provided, the most frequently endorsed option was “when a problem is identified” (93.2–96.5%). More care is provided consistent with these Standards at diagnosis and during the first week and month of treatment, with less frequent delivery of services consistent during ongoing treatment and into survivorship.

Financial assessments at diagnosis and over time (PSS5) were most often performed by social workers (88.0%). Financial advocates and counselors were used in a small number of sites (3.4%), as well as other hospital staffs.

Child-centered psychosocial care

A second set of Standards (PSS 7, 8, 9, 11) were related to the delivery of care directly to patients to prepare them for treatments and to encourage ongoing social and educational experiences and are presented in Table 3, including care of siblings. The most frequent way that care was provided for these child-centered standards was using written information (69–93%), online resources (48.7–86%), or videos (52.2%). When interventions were provided (n=113), distraction (96.5%), relaxation (96.5%) and cognitive behavioral therapy 67.3%) were used, consistent with evidence-based practice in this field8. For siblings, in addition to materials provided to parents (85%) and informal discussion with parents (90%), referral to community providers, agencies and programs (54–81%) were used.

TABLE 3.

| Standard | Care Delivery | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PSS7:‥psychoeducation, information, and anticipatory guidance related to disease, treatment, acute and long-term effects, hospitalization, procedures, and psychosocial adaptation | Written materials | 93.0 |

| Online resources | 86.0 | |

| Informational videos | 40.4 | |

|

| ||

| PSS8:‥developmentally appropriate preparatory information about invasive medical procedures and psychological interventions for these procedures. | Written materials | 69.0 |

| Online resources | 48.7 | |

| Informational videos | 52.2 | |

| Interventions included: | ||

| Distraction | 96.5 | |

| Relaxation | 96.5 | |

| Hypnosis | 16.8 | |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | 67.3 | |

|

| ||

| PSS9: …opportunities for social interaction ‥ | Facilitated activities and programs | 84.1 |

| Camps | 85.0 | |

| Support groups | 38.9 | |

| Online groups/chat rooms | 22.1 | |

| Informal discussion (usually w/parents) | 90.3 | |

| Materials provide to parents | 85.0 | |

| Referral to community agencies | 81.4 | |

|

| ||

| PSS10: Siblings of children with cancer should be provided with appropriate supportive services. | Supportive psychotherapy | 54.0 |

| Support groups | 21.2 | |

| Programs | 54.9 | |

|

| ||

| PSS11:‥school-age youth … should receive school reentry support ‥ coordinate communication between the patient/family, school, and the health care team | School program within the hospital | 65.5 |

| Coordinating staff member | 87.5 | |

Based on respondents answering each question. n’s ranged from 113–118.

Responses allowed for multiple answers (“check all that apply”)

Neuropsychological monitoring and adherence to treatment

A third set of Standards (PSS 2, 12) are closely related to the ongoing course of medical care, neuropsychological screening and monitoring and adherence to treatment (Table 4). The most common approach to neuropsychological monitoring is referral to a neuropsychologist (84.5%), along with Informal Discussion (77.6%) and neurocognitive screens (30.2%). These services are generally provided when a problem is identified although somewhat more frequently at the end of treatment and during survivorship visits. Adherence to treatment was generally assessed by asking the patient (96.4%) or family members (69%) and/or using self report measures with the patient (80.5%) or parents (79.6%).

Long-term survivors

The Standard related to psychosocial screening for long-term survivors was met primarily by informal discussion (84.0%), educational and vocational screening (44.8%), screening for social and relationship issues (48.3%) and screening for distress (50.9%). A variety of standardized and institution-specific approaches were noted.

Palliative care and bereavement

No detailed information was obtained about how palliative care is delivered because it usually involves referral to a palliative care team and is not a primary psychosocial team responsibility. In terms of bereavement, the majority (69%) of centers send a card or letter, and (50.4%) reported making a phone call to assess psychosocial status after a child’s death. Most have a hospital memorial service (59.3%) and some prepare legacy items (36.0%). In person meetings (7.1%), psychotherapy (2.7%) or support groups (13.3%) were less commonly offered.

Overall quality of psychosocial care in general

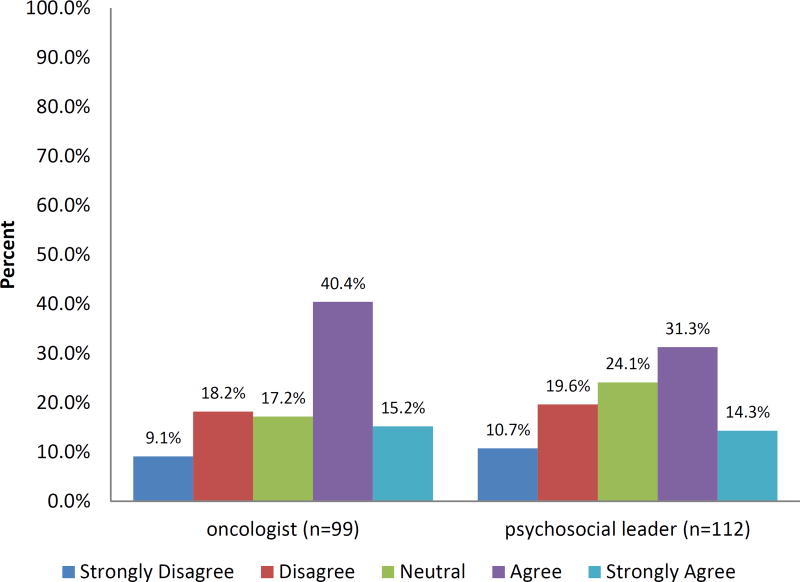

There was a range of responses to the item asking whether psychosocial care at the participants’ institutions was “state of the art” (Fig 1). The distributions of responses for oncologists and psychosocial leaders are quite consistent. Many oncologists (55.6%) and psychosocial leaders (45.6%) indicated that they “agree” or “strongly agree” with this statement. However, more than a quarter of oncologists (27.3%) and psychosocial leaders (30.3%) indicated that they “disagree” or “strongly disagree.” The multiple regression analysis indicated that integration of psychosocial care and implementation of the standards explained a significant amount of variance in perceived psychosocial care (F(4, 144) = 33.6, p < .001, R2 = .48). The extent of Integration significantly predicted perceived psychosocial care, β = .22, t = 3.2, p < .002, as did degree of Implementation, β = .51, t = 7.51, p < .001, indicating that more integration and implementation were associated with perceived better psychosocial care. The size of the psychosocial team did not predict the perceived psychosocial care, β = .08, t = .9, ns, neither did the size of the institution, β = .133, t = 1.349, ns.

Figure 1.

Endorsement of “comprehensive and state of the art” care by oncologists and psychosocial leaders

Discussion

Delivering care consistent with the Pediatric Cancer Psychosocial Standards of Care is an important mandate for multidisciplinary pediatric oncology programs. Although the importance of psychosocial care in pediatric oncology is widely endorsed as a concept, few details are available in terms of what care is provided across treatment centers. Models of care have been described28 and evidence for the important contributions of psychosocial research and care documented29. The data presented in this paper are unique and provide information that can inform clinical care and related research to advance the integration of psychosocial care for children and families.

The data reflect the complexity of understanding psychosocial care in pediatric cancer. There was a broad range of responses with respect to whether oncologists and psychosocial leaders think that the psychosocial care they provide is comprehensive and state of the art – about half of the centers indicated that they agreed or strongly agreed that their care was strong in this area. However, a sizeable minority of oncologists and psychosocial leaders were much less positive about the quality of psychosocial care at their institutions. It is important to learn more about why care was viewed as less comprehensive and state of the art at some centers, and to also understand the current services offered that inform these perceptions. Furthermore, there is no available guidance at present for recommended ways to meet the Standards, thus allowing for subjectivity and variability in appraisals.

Psychosocial practices that are indicative of integrated care were predictors of comprehensive state of the art care. Integrated care is characterized by partnerships among members of the treatment team, working in proximity to other healthcare providers, and often reporting to the same divisional or program leaders. Practices consistent with integrated care include regularly attending medical rounds and tumor boards, meeting as a psychosocial team, and co-training and consultation activities. Integrated care is also enhanced by interprofessional education and competencies for collaborative practices30. Integrated care activities are less likely to occur in “refer out” models or in situations where providers from another team or service provide singular patient-oriented consultations. It is also reassuring that perceptions of comprehensive care were associated with meeting the Standards. This suggests that the Standards are a viable means by which care can be organized and evaluated. However, it is also important to evaluate the quality of care and how quality care can be delivered in a measurable and consistent manner.

The size of the institution and the size of the psychosocial team were not significantly associated with the perception of state of the art psychosocial care. In some ways this is surprising as larger centers may have more resources and larger multidisciplinary teams may be able to provide a broader array of care. However, the data suggest that integration of this care is equally important in influencing the perception of quality care. Establishing and promoting clinical partnerships with the medical team, psychosocial team, nursing and other disciplines creates a framework for integrated care and collaboration. Integration can be achieved regardless of size and may not require substantial resources. For example, activities such as co-located psychosocial team members, an identified cohesive psychosocial team that meets and coordinates care, and participation of psychosocial team members in training for all disciplines are ways in which integration can be fostered regardless of program size.

Oncologists and psychosocial providers indicated that care consistent with each Standard was frequently provided. Those standards endorsed as being most frequently delivered are core services of assessment of psychosocial risk at diagnosis, determination of financial needs, and the delivery of psychosocial support. How and when this care is delivered is important and again shows the complexity of understanding psychosocial services. “Informal discussion” was reported in nearly all cases across these Standards. This is likely because informal discussion is a key component of rapport building and in connecting with patients and families and as a first-step in determining what services may be helpful to the family. However, there is also likely variability in how extensively informal discussion is used. If used in isolation or as the sole service provided, it is likely not sufficient in terms of meeting the Standards. Evidence based approaches (PAT18, DT23, PSST25, SCCIP26,27) are typically being used in less than half of the responding centers, indicating the need for further information on barriers to implementation of these approaches. Data also indicate that psychosocial care is most often delivered in response to an identified problem, which is inconsistent with the preventative approach of the Standards. Although a more universal model of psychosocial care may be challenging to implement, particularly for centers with fewer staff and resources, this approach is likely to be beneficial for patients, family, and staff over time.

Child-centered psychosocial care (psychoeducation, educational information, support during procedures, preparatory information, social interactions and school re-entry support) were frequently used approaches. Interventions used were generally evidence based (distraction, relaxation, cognitive behavioral therapy)8. In many cases, written materials and online resources were also used. Some evidence based approaches such as camps31 and sibling support groups14 were utilized but not as extensively. In some cases, specialized staff may not be readily available to implement Standards. For example, less than one third of centers have a neuropsychologist16, necessitating external referral to monitor neuropsychological deficits. In adherence to treatment, centers relied on asking the patient or family members, with limited use of standardized self-report measures.

Overall the data speak to the broad array of services that are provided across centers in the United States. Although the overall response rate was strong at 72%, centers with fewer resources or those without psychosocial staff may not have participated. There is subjectivity in the appraisals and there may also be a response or social desirability bias in the data. The Standards are intentionally broad, enabling programs to implement the Standards utilizing strategies and methods that best meet the needs of their patients and families. It is important to further understand the different ways in which the Standards may be met. There are ways in which this work can progress immediately. One is to explicitly describe approaches that may be used to meet each Standard competently and to evaluate their implementation. Use of evidence-based approaches will facilitate broader acceptance of psychosocial care and is consistent with current reimbursement models, helping to address barriers related to funding for psychosocial services16. Providing care consistent with the Standards can also be evaluated as part of Quality Improvement projects. In this way, psychosocial care can be defined and measured and tracked, with an eye to identifying strategies that work as well as needs for improvement.

A focus on dissemination and implementation science, where evidence-based approaches are shared and evaluated systematically, is also an exciting future direction. For example, current trials of problem-solving skills training are focused on increasing accessibility to this evidenced-based intervention by training additional interventionists and creating an online delivery modality.32 Future research will also be enriched by understanding the readiness of centers worldwide to implement psychosocial care consistent with the Standards.

Conclusion

The data point to the value of using the Standards to organize the delivery of psychosocial care. They also highlight the importance of instituting clinical activities that promote integrated psychosocial care by involving psychosocial staff in rounding, patient care discussions and in the training of other healthcare providers. Integrated care is also fostered by the identification of a psychosocial team and steps to assure a cohesive unit within the pediatric cancer unit to deliver care in a coordinated manner in partnership with the broader team. In addition, currently delivered services are often delivered primarily when a problem is identified. While providing interventions for an identified problem is very important, the absence of evidence for proactive and preventative psychosocial care is concerning.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material S1. Standards for the Psychosocial Care of Children with Cancer and Their Families

Supplementary Material S2. Preparing to Implement Psychosocial Standards: Current Staffing and Services (PIPS-CSS) Survey

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Nemours Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders and the Nemours Center for Healthcare Delivery Science. This work is supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. The authors thank the many healthcare providers who participated in the study for their timely and thoughtful responses to the survey and Scott Bradfield, M.D. for assistance in identifying participants. Members of the leadership team of the Psychosocial Standards of Care Project for Childhood Cancer (PSCPCC) – Peter Brown, M.B.A., Mary Jo Kupst, Ph.D., Robert Noll, Ph.D., Andrea Patenaude, Ph.D., and Vicki Sardi-Brown, Ph.D. provided input on the survey design. Faculty from the Wake Forest NCORP Research Base provided consultation on the design of the survey. The authors thank the Mattie Miracle Cancer Foundation for their support for the Psychosocial Standards for Care Project for Childhood Cancer (PSCPCC), and their continued commitment to ongoing projects related to the Standards.

Glossary

- COG

Children’s Oncology Group

- PIPS-CSS

Preparing to Implement Psychosocial Standards: Current Services and Staffing

- PSCPCC

Psychosocial Standards of Care Project for Childhood Cancer

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

- Standards

the Standards for Psychosocial Care for Children with Cancer and Their Families

- PSS1

Standard 1 Assessment of psychosocial healthcare needs

- PSS2

Standard 2 Monitoring of neuropsychological deficits

- PSS3

Standard 3 Screening in long-term survivorship

- PSS4

Standard 4 Psychosocial support and interventions

- PSS5

Standard 5 Assessment of financial need

- PSS6

Standard 6 Parental mental health

- PSS7

Standard 7 Psychoeducation, information and anticipatory guidance

- PSS8

Standard 8 Preparatory information for procedures

- PSS9

Standard 9 Opportunities for social interaction

- PSS10

Standard 10 Siblings

- PSS11

Standard 11 School support

- PSS12

Standard 12 Adherence

- PSS13

Standard 13 Palliative care/end of life care

- PSS14

Standard 14 Bereavement care

- U.S.

United States

Footnotes

The fifteenth standard is not discussed in this paper as it pertains to training, credentialing, supervision and other aspects of professional practice.

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Noll RB, Patel SK, Kardy KK, Pelletier W, Annett RD, Patenaude A COG Behavioral Sciences Committee. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 Blueprint for Research: Behavioral Science. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2013;60(6):1048–1054. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Comprehensive cancer care for children and their families: Summary of a joint workshop by the Institute of Medicine and the American Cancer Society. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiener L, Kazak AE, Noll RB, Patenaude AF, Kupst MJ. Standards for the Psychosocial Care of Children With Cancer and Their Families: An Introduction to the Special Issue. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015 Dec;62(Suppl 5):S419–24. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazak AE, Abrams AN, Banks J, Christofferson J, DiDonato S, Grootenhuis MA, Kabour M, Madan-Swain A, Patel SK, Zadeh S, Kupst MJ. Psychosocial assessment as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):426–459. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Annett R, Patel SK, Phipps S. Monitoring and assessment of neuropsychological outcomes as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):460–513. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lown EA, Phillips F, Schwartz LA, Rosenberg AR, Jones B. Psychosocial follow-up in survivorship as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):514–584. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steele AC, Mullins LL, Mullins AJ, Muriel AC. Psychosocial interventions and therapeutic support as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):585–618. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelletier W, Bona K. Assessment of financial burden as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):619–631. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kearney JA, Salley CG, Muriel AC. Psychosocial support for parents of children with cancer as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):632–683. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson AL, Young-Saleme T. Anticipatory guidance and psychoeducation as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):805–817. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flowers SR, Birnie KA. Procedural preparation as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):694–723. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christiansen HL, Bingen K, Hoag JA, Karst JS, Velázquez-Martin B, Barakat LP. Providing children and adolescents opportunities for social interaction as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):724–749. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerhardt CA, Lehmann V, Long KA, Alderfer MA. Supporting siblings as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):750–804. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson AL, Kelly KP, Christiansen HL, Elam M, Hoag J, Irwin MK, Pao M, Voll M, Noll RB. Academic continuity and school reentry support as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):805–817. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pai ALH, McGrady ME. Assessing treatment adherence as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):818–828. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver MS, Heinze KE, Kelly KP, Wiener L, Casey RL, Bell CJ, Wolfe J, Garee AM, Watson A, Hinds PS. Palliative care as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):829–833. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lichtenthal WG, Sweeney C, Roberts K, Corner G, Donovan L, Prigerson HG, Wiener L. Bereavement follow-up after the death of a child as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):834–869. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scialla MA, Canter KS, Chen FF, et al. Implementing the psychosocial standards in pediatric cancer: Current staffing and services available. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;00:e26634. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26634. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selove R, Kroll T, Coppes M, Cheng Y. Psychosocial services in the first 30 days after diagnosis: Results of a web-based survey of Children’s Oncology Group (COG) member institutions. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(3):435–40. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazak AE, Schneider S, Didonato S, Pai AL. Family psychosocial risk screening guided by the Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model (PPPHM) using the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):574–80. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.995774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel SK, Mullins W, Turk A, Dekel N, Kinjo C, Sato JK. Distress screening, rater agreement,and services in pediatric oncology. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20(12):1324–1333. doi: 10.1002/pon.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiener L, Battles H, Zadeh S, Widemann B, Pao M. Validity, Specificity, Feasibility and Acceptability of a Brief Pediatric Distress Thermometer in Outpatient Clinics. Psycho-Oncology. 2017;26(4):461–468. doi: 10.1002/pon.4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahler OJ, Fairclough DL, Phipps S, Mulhern RK, Dolgin MJ, Noll RB, Katz ER, Varni JW, Copeland DR, Butler RW. Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: report of a multisite randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(2):272–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazak AE, Simms S, Barakat L, Hobbie W, Foley B, Golomb V, Best M. Surviving cancer competently intervention program (SCCIP): a cognitive-behavioral and family therapy intervention for adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families. Fam Process. 1999;38(2):175–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1999.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kazak AE, Simms S, Alderfer MA, Rourke MT, Crump T, McClure K, Jones P, Rodriguez A, Boeving A, Hwang WT, Reilly A. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes from a pilot study of a brief psychological intervention for families of children newly diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(8):644–55. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kazak AE, Rourke MT, Alderfer MA, Pai A, Reilly AF, Meadows AT. Evidence-based assessment, intervention and psychosocial care in pediatric oncology: a blueprint for comprehensive services across treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(9):1099–110. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kazak A, Noll R. The integration of psychology in pediatric oncology research and practice: Collaboration to improve care and outcomes. Am Psychol. 2015 Feb-Mar;70(2):146–58. doi: 10.1037/a0035695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, D.C.: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu YP, McPhail J, Mooney R, Martiniuk A, Amylon MD. A multisite evaluation of summer camps for children with cancer and their siblings. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2016 Nov-Dec;34(6):449–459. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2016.1217963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noll RB, Sahler OJ. Problem-solving skills training: Implementation and dissemination of an evidence-based intervention. Workshop presented at: 41st Annual Association of Pediatric Oncology Social Workers Conference; April, 2017; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material S1. Standards for the Psychosocial Care of Children with Cancer and Their Families

Supplementary Material S2. Preparing to Implement Psychosocial Standards: Current Staffing and Services (PIPS-CSS) Survey