Abstract

The transforming growth factor β regulator 4 (TBRG4) gene, located on the 7p14-p13 chromosomal region, is implicated in numerous types of cancer. However, the contribution(s) of TBRG4 in human lung cancer remains unknown. In the present study, the expression of TBRG4 mRNA was investigated in the H1299 lung cancer cell line using the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) following the knockdown of TBRG4 by a lentivirus-mediated small interfering RNA (siRNA). Results identified that the expression of TBRG4 within H1299 cells was significantly suppressed (P<0.01) by RNA interference, and 586 genes were differentially expressed following TBRG4 silencing. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) revealed that these genes were often associated with infectious diseases, organismal injury, abnormalities and cancer functional networks. Further IPA of these networks revealed that TBRG4 knockdown in H1299 cells deregulated the expression of 21 downstream genes, including the upregulation of DNA damage-inducible transcript 3 (DDIT3), also termed CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein, and downregulation of caveolin 1 (CAV1) and ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit M2 (RRM2). Results were validated using qPCR and western blotting. Furthermore, immunohistochemical staining of TBRG4 protein identified that expression was markedly increased in carcinoma compared with in normal tissue. In conclusion, TBRG4 serves a role in the tumorigenesis of lung cancer via deregulation of DDIT3, CAV1 and RRM2. The results of the present study may be important in contributing to our understanding of TBRG4 as a target for lung cancer treatment.

Keywords: expression profiling, immunohistochemistry, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, lung carcinoma, microarray, transforming proliferation factor β regulator 4

Introduction

Lung cancer is the primary cause of cancer-associated mortality worldwide, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounting for ~85% of all lung cancer cases in 2014 (1). The majority of patients present with advanced disease with a 5-year survival rate of <15% in 2014 (2,3). Although surgery remains the front-line choice of treatment for localized NSCLC, those with advanced forms may require chemotherapy (4). Targeted therapy constitutes a promising treatment strategy for prolonging the survival of a subset of patients with NSCLC (5). However, drug resistance conferred by complex recurrent genetic and epigenetic changes remains a crucial obstacle for targeted therapies (6–10). Consequently, there is urgent requirement to understand the molecular mechanism(s) underlying the development of NSCLC, and develop new therapies for treating NSCLC.

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) regulator 4 (TBRG4), also termed cell cycle progression restoration protein 2 or Fas-activated serine-threonine kinase domain-containing protein 4, encodes a regulator for TGFb (11–14). TBRG4 (GenBank no. AAH14918.1) is located on chromosome 7p12.3–13, and is duplicated in patients with Sézary syndrome (15). TBRG4 has previously been demonstrated to stabilize the expression level of transcription of cyclin 1 and 2 (12). In 293 and Jurkat human cell lines, TBRG4 physically interacts with the virus protein U encoded by the human immunodeficiency virus (16). Furthermore, TBRG4 also interacts with pleiotrophin protein, and TBRG4 silencing affects the stability of certain mitochondrial mRNAs (17,18). However, the contribution of TBRG4 in the tumorigenesis of NSCLC remains unclear.

In the present study, the effect of TBRG4 silencing on genome-wide gene expression patterns within human H1299 lung cancer cells was investigated. The expression of TBRG4 in tumor and adjacent normal tissues was also evaluated.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human H1299 lung cancer cells were purchased from the Shanghai Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Corning Life Sciences, Shanghai, China) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

siRNA transduction

The sequence of siRNA (5′-GTTCTTCAGCCTGGTACAT-3′) was designed by GeneChem Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for targeting the TBRG4 sequence (GenBank no. NM_004749). The TBRG4 hairpin oligonucleotide was inserted into the pGV115-GFP lentiviral vector (GeneChem Co., Ltd.) to construct a pGV115-GFP-short hairpin TBRG4 (shTBRG4) TBRG4-knockdown vector. The negative control (shCtrl) sequence was previously reported (19,20), and when incorporated into the lentiviral vector was referred to as pGV115-GFP-shCtrl. The lentiviral particles were prepared as previously described (21). For cellular transduction of shTBRG4 lentiviral or shCtrl lentivirus, 1×105 cells/well were seeded into 6-well plates. The following day, cells were transduced with validated shTBRG4 lentivirus (5×105 TU/ml, 2 µl) or shCtrl lentivirus (8×105 TU/ml, 1.25 µl) using 4 µl Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. After evaluating infection efficiency using light and fluorescent microscopy at 72 h after infection. Cells were harvested and used for subsequent experiments.

RNA isolation and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the aforementioned transduced cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and then 2 µg total RNA was reverse-transcribed using a QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen China Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), according to the manufacturer's protocol. A 1 µg amount of cDNA was used as a template for qPCR using a SYBR® Green PCR Master mix (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The primer sequences used were as follows: TBRG4 forward, 5′-CAGCTCACCTGGTAAAGCGAT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGGAGTAGATGCTCGTTCCTTC-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-TGACTTCAACAGCGACACCCA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAA-3′. Results were normalized to GAPDH data as described previously (22). Data were analyzed using the method of Pfaffl (23). PCR primers used for validating the microarray data are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Primer sequences used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

| Gene | Primer sequence 5′-3′ |

|---|---|

| GAPDH FP | TGACTTCAACAGCGACACCCA |

| GAPDH RP | CACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAA |

| IGF2 FP | CCTCCAGTTCGTCTGTGGG |

| IGF2 RP | CACGTCCCTCTCGGACTTG |

| MYBL2 FP | AGAATAGCACCAGTCTGTCCTT |

| MYBL2 RP | CCAATGTGTCCTGTTTGTTCCA |

| AURKA FP | GCCCTGTCTTACTGTCATTCG |

| AURKA RP | AGGTCTCTTGGTATGTGTTTGC |

| CAV1 FP | CTGAGCGAGAAGCAAGTG |

| CAV1 RP | AGAGAGAATGGCGAAGTAAATG |

| RAP1A FP | CGTGAGTACAAGCTAGTGGTCC |

| RAP1A RP | CCAGGATTTCGAGCATACACTG |

| SERPINE1 FP | GCACCACAGACGCGATCTT |

| SERPINE1 RP | ACCTCTGAAAAGTCCACTTGC |

| SCD FP | TACTTGGAAGACGACATTCGC |

| SCD RP | GGTGTAGAACTTGCAGGTAGGA |

| DDIT3 FP | CTTCTCTGGCTTGGCTGACTGA |

| DDIT3 RP | TGACTGGAATCTGGAGAGTGAGG |

| SESN2 FP | TCTTACCTGGTAGGCTCCCAC |

| SESN2 RP | AGCAACTTGTTGATCTCGCTG |

| RRM2 FP | AAGAAACGAGGACTGATGC |

| RRM2 RP | CTGTCTGCCACAAACTCAA |

| CDC20 FP | CTTCGGCTCAGTGGAAAA |

| CDC20 RP | GTCTGGCAGGGAAGGAAT |

| FOXM1 FP | GCAGCGACAGGTTAAGGTTGAG |

| FOXM1 RP | GTTGTGGCGGATGGAGTTCTTC |

| IDI1 FP | TCCATTAAGCAATCCAGCCGA |

| IDI1 RP | CCCAGATACCATCAGACTGAGC |

| PGK1 FP | TGGACGTTAAAGGGAAGCGG |

| PGK1 RP | GCTCATAAGGACTACCGACTTGG |

FP, forward primer; RP, reverse primer.

Gene microarray

The genome-wide effect of TBRG4 knockdown was studied using a GeneChip® PrimeView™ Human Gene Expression Array (Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) consisting of 20,000 genes. Three biological replicates of H1299 cells transduced with shTBRG4 or shCtrl lentiviruses (for 72 h) were microarrayed. RNA was initially isolated using TRIzol reagent, and quality was determined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA) and Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Individual microarrays were used for gene expression profiling of each sample. Briefly, 500 ng total RNA was reverse-transcribed and labeled with biotin using the GeneChip® 3′ IVT labeling kit, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Labeled cDNA was then hybridized onto the GeneChip® PrimeView™ Human Gene Expression Array at 60°C overnight. Arrays were performed with GeneChip® Hybridization Wash and Stain kit using GeneChip® Fluidics Station 450. All GeneChip® products were obtained from Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., and all were used according to the manufacturer's protocol. The chip array was scanned directly post-hybridization using a GeneChip® Scanner 3000. Microarray data were analyzed with GeneSpring software (version 11; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Data were normalized using the GeneSpring normalization algorithm. Finally, genes which were differentially expressed >1.5-fold, and had a differential score P≤0.05 among test samples, were identified from normalized data sets.

Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA)

Datasets representing differentially expressed genes derived from microarray analyses were imported into the IPA tool (http://www.ingenuity.com; Ingenuity® Systems, Redwood City, CA, USA). The ‘core analysis’ function of the IPA software in the present study was used to interpret the differentially expressed data, which included ‘Disease and Functions’, and ‘Molecular Network’. Differentially expressed genes were mapped onto genetic networks available in the Ingenuity database and then ranked on the basis of the overlap P-value to measure enrichment of network-regulated genes in the present dataset and the activation z-score algorithms computed by IPA software (24). Analyses performed within the IPA program include the identification of biological networks of a particular interesting dataset according to the purpose of the present study, and its global functions, functional signaling pathways and downstream target genes.

Patients and tissue samples

A total of 75 patients diagnosed with lung cancer and who received surgery at The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College (Anhui, China) between December 2011 and June 2015 were randomly enrolled into the present study. All samples were obtained following provision of written informed consent and used with approval from the Review Board of The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College. The age range of diagnosed patients was between 35 and 77 years, with a median age of 60 years. Tissue samples were classified as tumor or adjacent carcinomatous tissue. Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients included age at time of diagnosis, tissue type, histological grade, distant metastasis and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage (Table II). All patients were clinically staged according to the criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system (25). Histological grades of primary tumors were based on the World Health Organization recommendations (26).

Table II.

Association of TBRG4 expression and clinicopathological characteristics.

| TBRG4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | Low | High | P-value |

| Sex | 0.808 | |||

| Male | 39 | 31 | 8 | |

| Female | 35 | 27 | 8 | |

| Age, years | 0.348 | |||

| ≤60 | 34 | 28 | 6 | |

| >60 | 41 | 30 | 11 | |

| Tumor size, cm | 0.698 | |||

| ≤4 | 50 | 38 | 12 | |

| >4 | 25 | 20 | 5 | |

| Distant metastasis | 0.269 | |||

| M0 | 71 | 54 | 17 | |

| M1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| TNM stage | 0.014a | |||

| TNM1 | 37 | 24 | 13 | |

| TNM2 | 18 | 16 | 2 | |

| TNM3 | 16 | 14 | 2 | |

| TNM4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| I/II | 53 | 40 | 13 | 0.553 |

| III | 22 | 18 | 4 | |

P-value for the TNM stage was corrected for multiple comparison by the Bonferroni correction method. P=0.014 was not considered to indicate a statistically significant difference according to the principle of multiple testing of Bonferroni correction. TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in 4% neutral-buffered formalin at room temperature overnight and then embedded in paraffin. Sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections (5 µm thick) were dehydrated and deparaffinized in xylene 2–3 times at room temperature and rehydrated with a gradient alcohol series. Antigen retrieval was performed using 0.1 mol/l citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 30 min. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched for 10 min with 3% (v/v) H2O2 at room temperature. Slides were then washed three times with PBS and blocked for 30 min with 10% (w/v) normal goat serum (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) in 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.) in PBS. Slides were incubated with a 1:1,000 dilution of anti-TBRG4 monoclonal antibody (cat. no. D154006; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.) at 37°C for 30 min. Following incubation for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin secondary antibody (dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. D111054; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.), the development reaction was detected by exposure to 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.) for 5 min at room temperature. Immunostained slides were digitized using the ScanScope XT (Aperio, Cista, CA, USA) and scored independently by two pathologists according to the Allred scoring system (27). The scoring was based on staining intensity: Negative, 0; weak, 1; intermediate, 2; and strong, 3. A proportionate score was assigned to represent the estimated percentage of positively stained cells (0, <1%; 1, 1–25%; 2, 26–50%; 3, 51–75%; 4, ≥76%). The multiplication of the two parameters was performed to obtain a total score ranging from negative (0–1) to positive (>2).

Statistical analysis

Numerical data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and analyzed using Student's t-test. All categorical data were expressed as a frequency. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze the clinicopathological and TBRG4 gene expression data. Analysis was performed with SPSS (version 16.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Lentivirus-mediated TBRG4 knockdown

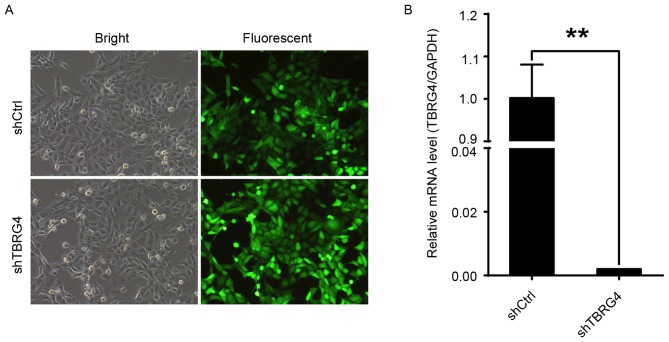

Efficacy of TBRG4-specific siRNA in downregulating the expression of TBRG4 in H1299 lung cancer cells was evaluated with RNA expression data generated by qPCR. The proportions of infected H1299 cells transduced with either shCtrl or shTBRG4 lentiviruses were >70% at 72 h post-infection (Fig. 1A). The level of TBRG4 mRNA expression in cells transduced with shTBRG4 was significantly decreased at 72 h post infection compared with those transduced with a shCtrl lentivirus (P<0.01; Fig. 1B). Thus, shTBRG4 lentivirus was specific and effective in knocking down TBRG4.

Figure 1.

TBRG4 knockdown in H1299 cells infected with shTBRG4 lentivirus. H1299 cells were infected with the shTBRG4 or shCtrl lentivirus. (A) Infection efficiency evaluated using light and fluorescent microscopy at 72 h post infection. Representative images of the cultures are presented (magnification, ×100). (B) Results represent the fold change in TBRG4 mRNA levels, normalized to GAPDH expression. **P<0.01, compared with the shCtrl group. sh, short hairpin; Ctrl, control; TBRG4, transforming growth factor β regulator 4.

Genome-wide effects of TBRG4 knockdown

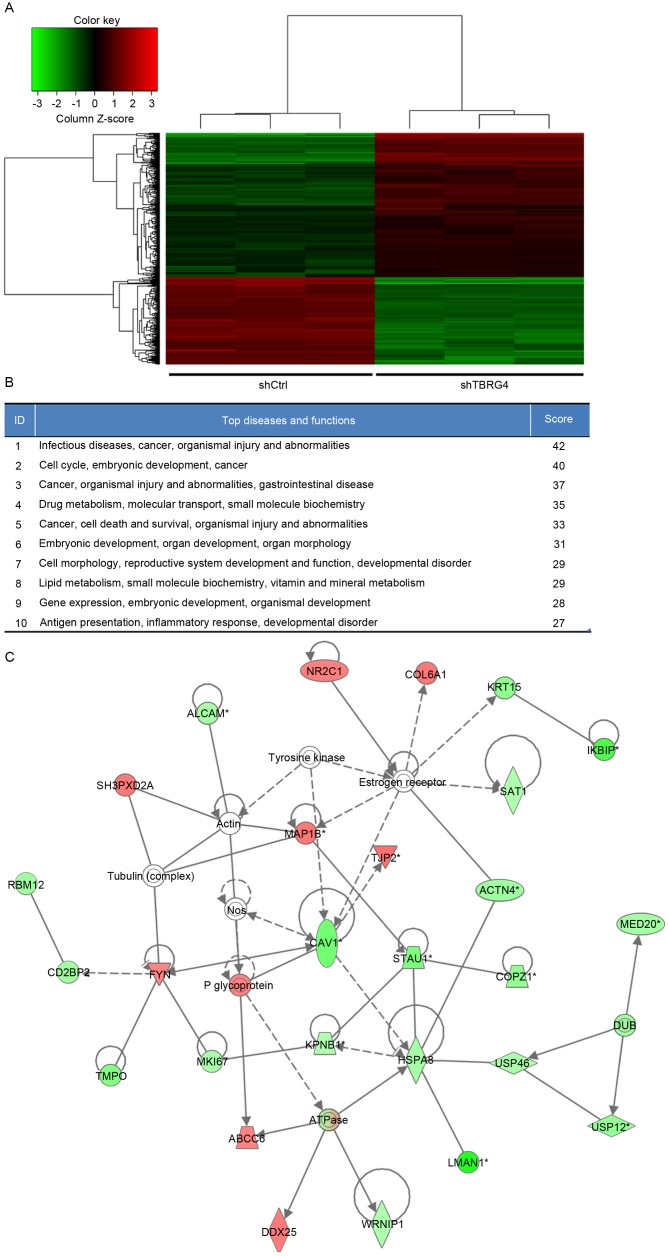

In total, 20,000 genes were microarrayed to determine the influence that TBRG4 knockdown has on downstream gene expression. The gene expression profiles of H1299 cells transduced with shTBRG4 or shCtrl-payload lentiviruses were determined using a GeneChip® PrimeView™ Human Gene Expression Array using three biological replicates. A total of 586 differentially expressed genes were identified, of which 357 were downregulated and 229 were upregulated (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

IPA summary of differentially expressed genes derived from a microarray of 20,000 genes. (A) Heat map of differentially expressed genes derived from microarray. (B) Top 10 networks with their respective scores obtained using IPA. (C) The highest rated networks (infectious diseases, cancer, organismal injury and abnormalities) in IPA. Upregulated genes are depicted in red, whereas downregulated genes are depicted in green. IPA, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis; sh, short hairpin; Ctrl, control; TBRG4, transforming growth factor β regulator 4.

Elucidation of pathways and interactions among differentially expressed genes

Biological interactions were identified in the 586 differently regulated genes using the IPA program. This output highlighted 25 significant networks (data not shown), of which IPA identified a list of the top 10 networks (Fig. 2B). Of these networks, those associated with infectious diseases, cancer, organismal injury and abnormalities were the highest ranked networks, with 27 focus molecules and a significance score of 42 (Fig. 2C). In particular, Fig. 2C presents that TBRG4 is located upstream of all focus genes.

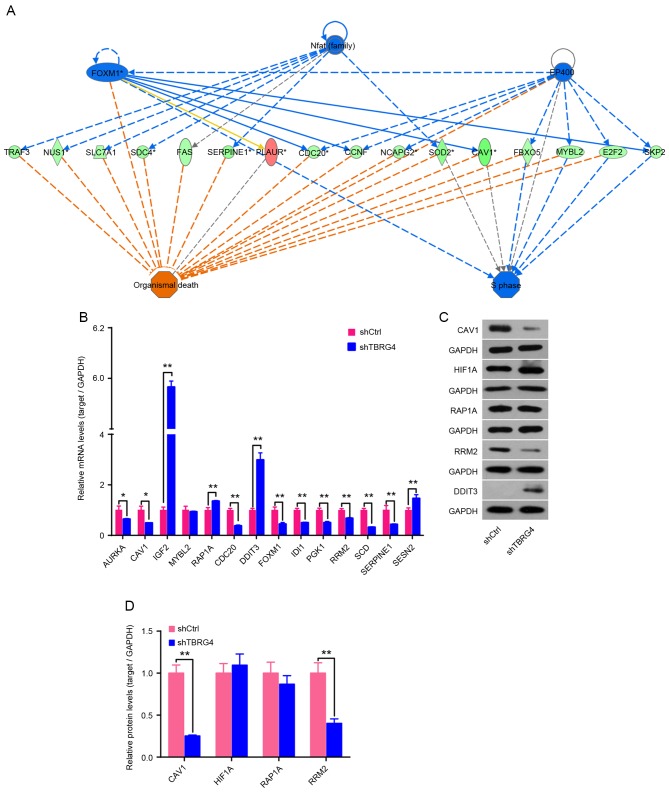

TBRG4 knockdown markedly upregulates DDIT3 and downregulates CAV1 and RRM2

Expression of mRNA for 14 downstream genes of TBRG4 identified using IPA was analyzed using qPCR, including AURKA, CAV1, IGF2, MYBL2, RAP1A, CDC20, DDIT3, FOXM1, IDI1, PGK1, RRM3, SCD, SERPINE1 and SESN2 (Fig. 3A). Results demonstrated that IGF2, RAP1A, DDIT3 and SESN2 were upregulated following TBRG4 knockdown, whereas the remaining 10 genes were downregulated (Fig. 3B). Western blotting also demonstrated that knockdown of TBRG4 increased the level of DDIT3 expression and decreased the levels of CAV1 and RRM2 (Fig. 3C and D).

Figure 3.

Effect of TBRG4 knockdown on downstream genes. (A) Analysis of downstream genes of TBRG4 using IPA. (B) qPCR was used to determine the changes in expression level of downstream genes of TBRG4 in H1299 cells 72 h after transfection of TBRG4-specific siRNA. Samples were normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression. The qPCR data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (C) Western blotting was performed to analyze the change in expression of TBRG4 downstream proteins in H1299 cells infected with shTBRG4 lentivirus. (D) Densitometric analysis of target proteins in (C). GAPDH protein was used as a loading control for densitometric analysis. **P<0.05 vs. shCtrl-transfected cells. IPA, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; siRNA, small interfering RNA; sh, short hairpin; Ctrl, control; TBRG4, transforming growth factor β regulator 4.

Association of TBRG4 expression in lung cancer tissues and clinicopathological characteristics

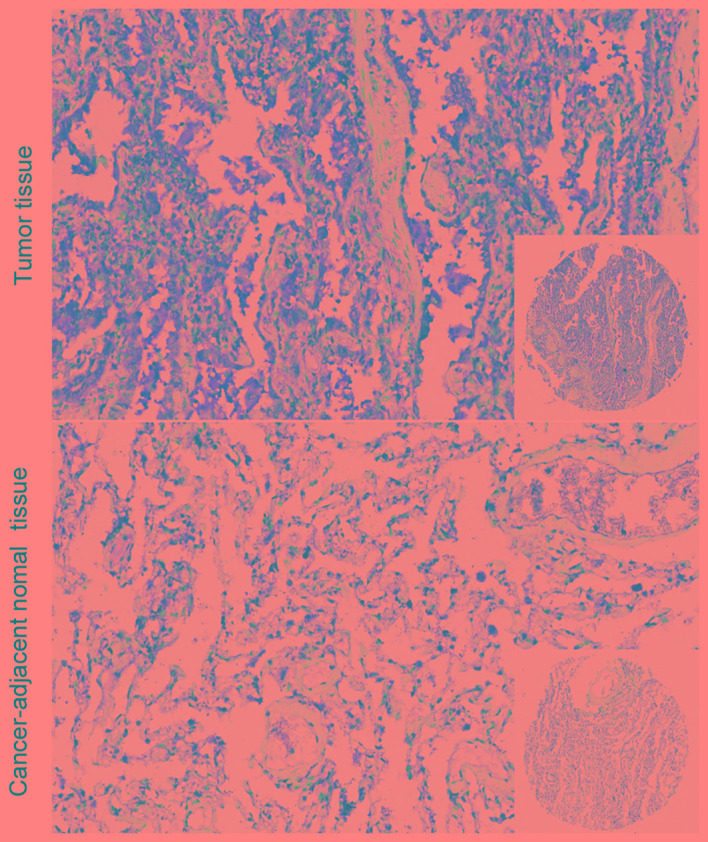

The present study immunostained the TBRG4 protein expressed within lung cancer and adjacent normal tissues. The immunohistochemical data revealed that the expression of TBRG4 was markedly increased within lung cancer tissues compared with normal tissues retrieved from the adjacent epithelium (Fig. 4). There was no significant difference identified in TBRG4 expression between the sexes, neither was it significantly associated with age, tumor size, distant metastasis, TNM stage or tumor grade (P>0.05; Table II).

Figure 4.

Representative images of TBRG4 protein expression in lung tumor and cancer-adjacent normal tissue by immunohistochemisty. Magnification, ×200 (insets, ×40).

Discussion

TBRG4 is implicated in a number of human malignancies; however, its contribution to lung cancer has not yet been evaluated. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the expression of TBRG4 within lung carcinomas. The results of the present study demonstrate that there is a markedly increased expression of TBRG4 in lung cancer in vitro and ex vivo. As previously identified, TBRG4 is a regulator of TGFb located on chromosome 7p12.7–13 (15). Chromosomal abnormity, including breakpoint and duplication at the 7p13 locus, has previously been reported in a range of hematological malignancies (28). Previously, it was reported that this region where TBRG4 is located is disrupted in patients with Sézary syndrome, a leukemic form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, with chromosomal abnormalities and mutations in certain genes that are relevant to this disease (14,29). The region is also amplified in 30% of cell lines derived from patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (30). Furthermore, recent research has demonstrated that TBRG4 exhibits significant changes in extramedullary relapse of multiple myelomas (14). This evidence suggests that TBRG4 serves an important role in several types of human cancer.

In order to assess the contribution of TBRG4 to lung cancer, a shTBRG4 lentiviral vector was initially constructed, which specifically silenced the expression of TBRG4 in H1299 lung cancer cells. The shTBRG4-infected cells demonstrated a decrease in expression of TBRG4 compared with those transduced with a shCtrl control lentivirus. In order to obtain an understanding of the downstream biological alterations, the transcriptome of H1299 cells transduced with either shTBRG4 or shCtrl lentiviruses was investigated with an Affymetrix microarray of 20,000 genes. Gene expression profiling and network analysis revealed a set of 586 differentially expressed genes, a number of which were categorized into infectious diseases, cancer, organismal injury and abnormalities. A key observation in the present study was the identification of the set of genes, which were altered downstream due to the knockdown of TBRG4. Results of the present study demonstrated a significant increase in the level of DDIT3, and a decrease in the levels of CAV1 and RRM2 genes at the transcriptional (qPCR) and translational (western blotting) levels. DDIT3 is a transcription factor which is considered as a marker of commitment of endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis via induction of B-cell lymphoma 2 downregulation and death receptor 5 activation (31,32). Caveolin-1 is a multifunctional molecule typically expressed in membranous structures. The wild-type form acts as a tumor suppressor protein through contact inhibition of signaling molecules; however, its loss in cancer cells promotes tumor growth, motility, vascularization and metastasis, and decreases survival outcomes (33–36). The ribonucleotide reductase subunit M2 (RRM2) is reported to regulate several oncogenes that control malignant potential, and therefore may serve a major role in tumor progression (37,38). RRM2 serves as a prognostic biomarker for several types of cancer (39–41), and knockdown is reported to lead to apoptosis in NSCLC (38). Immunohistochemistry results validated the increased levels of TBRG4 in tumor tissue; therefore, TBRG4 knockdown complicated the tumorigenesis of H1299 cells by upregulating DDIT3 and downregulating CAV1 and RRM2. Further study is currently ongoing in order to validate the precise role of TBRG4 knockdown.

In conclusion, the results of the present study highlighted the tumorigenic roles of TBRG4 by silencing its expression in human H1299 lung cancer cells. This present study has provided evidence to further the understanding of the precise role of TBRG4 in the tumorigenesis of human lung cancer. However, the exact underlying molecular mechanisms by which TBRG4 influences the biological behaviors of lung cancer cells are yet to be determined.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reungwetwattana T, Dy GK. Targeted therapies in development for non-small cell lung cancer. J Carcinog. 2013;12:22. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.123972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumarakulasinghe NB, van Zanwijk N, Soo RA. Molecular targeted therapy in the treatment of advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Respirology. 2015;20:370–378. doi: 10.1111/resp.12490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang JW, Wei NC, Su HJ, Huang JL, Chen TC, Wu YC, Yu CT, Hou MM, Hsieh CH, Hsieh JJ, et al. Comparison of genomic signatures of non-small cell lung cancer recurrence between two microarray platforms. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:1259–1265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gridelli C, Felip E. Targeted therapies development in the treatment of advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:415641. doi: 10.1155/2011/415641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergethon K, Shaw AT, Ou SH, Katayama R, Lovly CM, McDonald NT, Massion PP, Siwak-Tapp C, Gonzalez A, Fang R, et al. ROS1 rearrangements define a unique molecular class of lung cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:863–870. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammerman PS, Sos ML, Ramos AH, Xu C, Dutt A, Zhou W, Brace LE, Woods BA, Lin W, Zhang J, et al. Mutations in the DDR2 kinase gene identify a novel therapeutic target in squamous cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:78–89. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-11-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Greulich H, Muzny DM, Morgan MB, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peifer M, Fernandez-Cuesta L, Sos ML, George J, Seidel D, Kasper LH, Plenker D, Leenders F, Sun R, Zander T, et al. Integrative genome analyses identify key somatic driver mutations of small-cell lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1104–1110. doi: 10.1038/ng.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wangari-Talbot J, Hopper-Borge E. Drug resistance mechanisms in non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Can Res Updates. 2013;2:265–282. doi: 10.6000/1929-2279.2013.02.04.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, Derge JG, Klausner RD, Collins FS, Wagner L, Shenmen CM, Schuler GD, Altschul SF, et al. Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2002; pp. 16899–16903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards MC, Liegeois N, Horecka J, DePinho RA, Sprague GF, Jr, Tyers M, Elledge SJ. Human CPR (cell cycle progression restoration) genes impart a Far-phenotype on yeast cells. Genetics. 1997;147:1063–1076. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.3.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simarro M, Gimenez-Cassina A, Kedersha N, Lazaro JB, Adelmant GO, Marto JA, Rhee K, Tisdale S, Danial N, Benarafa C, et al. Fast kinase domain-containing protein 3 is a mitochondrial protein essential for cellular respiration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;401:440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sevcikova S, Paszekova H, Besse L, Sedlarikova L, Kubaczkova V, Almasi M, Pour L, Hajek R. Extramedullary relapse of multiple myeloma defined as the highest risk group based on deregulated gene expression data. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2015;159:288–293. doi: 10.5507/bp.2015.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prasad A, Rabionet R, Espinet B, Zapata L, Puiggros A, Melero C, Puig A, Sarria-Trujillo Y, Ossowski S, Garcia-Muret MP, et al. Identification of gene mutations and fusion genes in patients with sezary syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:1490–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jager S, Cimermancic P, Gulbahce N, Johnson JR, McGovern KE, Clarke SC, Shales M, Mercenne G, Pache L, Li K, et al. Global landscape of HIV-human protein complexes. Nature. 2012;481:365–370. doi: 10.1038/nature10719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rolland T, Tasan M, Charloteaux B, Pevzner SJ, Zhong Q, Sahni N, Yi S, Lemmens I, Fontanillo C, Mosca R, et al. A proteome-scale map of the human interactome network. Cell. 2014;159:1212–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf AR, Mootha VK. Functional genomic analysis of human mitochondrial RNA processing. Cell Rep. 2014;7:918–931. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu H, Liang S, Yang X, Ji Z, Zhao W, Ye X, Rui J. RNAi-mediated RPL34 knockdown suppresses the growth of human gastric cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:2267–2272. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li LH, He J, Hua D, Guo ZJ, Gao Q. Lentivirus-mediated inhibition of Med19 suppresses growth of breast cancer cells in vitro. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68:207–215. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lois C, Hong EJ, Pease S, Brown EJ, Baltimore D. Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science. 2002;295:868–872. doi: 10.1126/science.1067081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dubey R, Chhabra R, Saini N. Small interfering RNA against transcription factor STAT6 leads to increased cholesterol synthesis in lung cancer cell lines. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: The 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho KR, Shih IeM. Ovarian cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:287–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harvey JM, Clark GM, Osborne CK, Allred DC. Estrogen receptor status by immunohistochemistry is superior to the ligand-binding assay for predicting response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1474–1481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dyer MJ, Nacheva E, Fischer P, Heward JM, Labastide W, Karpas A. A new human T-cell lymphoma cell line (Karpas 384) of the T-cell receptor gamma/delta lineage with translocation t(7:14) (p13;q11.2) Leukemia. 1993;7:1047–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H, Krizek J, Bretscher A. Construction of a GAL1-regulated yeast cDNA expression library and its application to the identification of genes whose overexpression causes lethality in yeast. Genetics. 1992;132:665–673. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carey TE, Van Dyke DL, Worsham MJ. Nonrandom chromosome aberrations and clonal populations in head and neck cancer. Anticancer Res. 1993;13:2561–2567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han J, Murthy R, Wood B, Song B, Wang S, Sun B, Malhi H, Kaufman RJ. ER stress signalling through eIF2α and CHOP, but not IRE1α, attenuates adipogenesis in mice. Diabetologia. 2013;56:911–924. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2809-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flocke LS, Trondl R, Jakupec MA, Keppler BK. Molecular mode of action of NKP-1339-a clinically investigated ruthenium-based drug-involves ER- and ROS-related effects in colon carcinoma cell lines. Invest New Drugs. 2016;34:261–268. doi: 10.1007/s10637-016-0337-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engelman JA, Chu C, Lin A, Jo H, Ikezu T, Okamoto T, Kohtz DS, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-mediated regulation of signaling along the p42/44 MAP kinase cascade in vivo. A role for the caveolin-scaffolding domain. FEBS Lett. 1998;428:205–211. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Podar K, Tai YT, Cole CE, Hideshima T, Sattler M, Hamblin A, Mitsiades N, Schlossman RL, Davies FE, Morgan GJ, et al. Essential role of caveolae in interleukin-6- and insulin-like growth factor I-triggered Akt-1-mediated survival of multiple myeloma cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5794–5801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quest AF, Gutierrez-Pajares JL, Torres VA. Caveolin-1: An ambiguous partner in cell signalling and cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:1130–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li M, Chen H, Diao L, Zhang Y, Xia C, Yang F. Caveolin-1 and VEGF-C promote lymph node metastasis in the absence of intratumoral lymphangiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer. Tumori. 2010;96:734–743. doi: 10.1177/030089161009600516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan H, Villegas C, Wright JA. Ribonucleotide reductase R2 component is a novel malignancy determinant that cooperates with activated oncogenes to determine transformation and malignant potential; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 1996; pp. 14036–14040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahman MA, Amin AR, Wang D, Koenig L, Nannapaneni S, Chen Z, Wang Z, Sica G, Deng X, Chen ZG, Shin DM. RRM2 regulates Bcl-2 in head and neck and lung cancers: A potential target for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3416–3428. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mah V, Alavi M, Márquez-Garbán DC, Maresh EL, Kim SR, Horvath S, Bagryanova L, Huerta-Yepez S, Chia D, Pietras R, Goodglick L. Ribonucleotide reductase subunit M2 predicts survival in subgroups of patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma: Effects of gender and smoking status. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H, Liu X, Warden CD, Huang Y, Loera S, Xue L, Zhang S, Chu P, Zheng S, Yen Y. Prognostic and therapeutic significance of ribonucleotide reductase small subunit M2 in estrogen-negative breast cancers. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:664. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Zhang H, Lai L, Wang X, Loera S, Xue L, He H, Zhang K, Hu S, Huang Y, et al. Ribonucleotide reductase small subunit M2 serves as a prognostic biomarker and predicts poor survival of colorectal cancers. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013;124:567–578. doi: 10.1042/CS20120240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]