Abstract

Introduction

Every year around 150,000 pilgrims from Bangladesh perform Umrah and Hajj. Emergence and continuous reporting of MERS-CoV infection in Saudi Arabia emphasize the need for surveillance of MERS-CoV in returning pilgrims or travelers from the Middle East and capacity building of health care providers for disease containment. The Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control & Research (IEDCR) under the Bangladesh Ministry of Health and Family welfare (MoHFW), is responsible for MERS-CoV screening of pilgrims/ travelers returning from the Middle East with respiratory illness as part of its outbreak investigation and surveillance activities.

Methods

Bangladeshi travelers/pilgrims who returned from the Middle East and presented with fever and respiratory symptoms were studied over the period from October 2013 to June 2016. Patients with respiratory symptoms that fulfilled the WHO MERS-CoV case algorithm were tested for MERS-CoV and other respiratory tract viruses. Beside surveillance, case recognition training was conducted at multiple levels of health care facilities across the country in support of early detection and containment of the disease.

Results

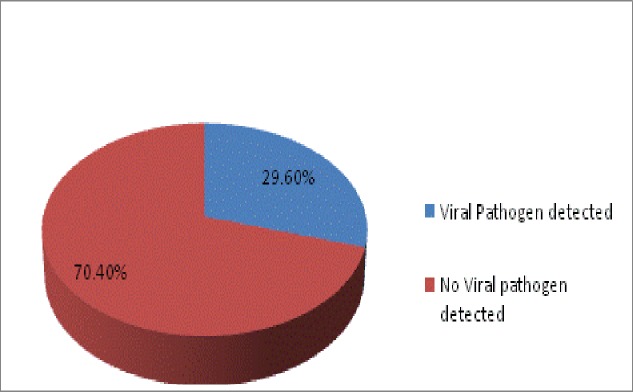

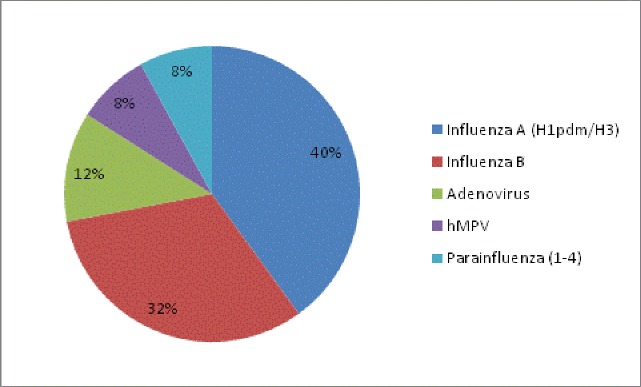

Eighty one suspected cases tested by real time PCR resulted in zero detection of MERS-CoV infection. Viral etiology detected in 29.6% of the cases was predominantly influenza A (H1N1 and H3N2), and influenza B infection (22%). Peak testing occurred mostly following the annual Hajj season.

Conclusions

Respiratory tract infections in travelers/pilgrims returning to Bangladesh from the Middle East are mainly due to influenza A and influenza B. Though MERS-CoV was not detected in the 81 patients tested, continuous screening and surveillance are essential for early detection of MERS-CoV infection and other respiratory pathogens to prevent transmissions in hospital settings and within communities. Awareness building among healthcare providers will help identify suspected cases.

Introduction

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), a newly emerged novel corona virus, is associated with severe acute respiratory infection with high mortality rates [1]. MERS-CoV is an enveloped, single stranded positive sense RNA virus belonging to lineage C betacoronavirus. It was first isolated in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) from a patient with acute pneumonia who subsequently died of renal failure in September 2012 [2,3]. Although MERS-CoV was suspected primarily as zoonotic in origin butanimal to human transmission is not fully understood yet [4]. Human-to-human transmission has been documented in several clusters among health-care providers and contacts [5–8]. Since 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 1841 laboratory-confirmed MERS-CoV cases including 652 deaths from 28 countries[9]. All reported cases had an epidemiological link either directly or indirectly and around 80% of the cases were reported from KSA [10,11].The crude case fatality rate was 35% and males more than 60 years of age having underlying co-morbid condition are at higher risk of developing life threatening severe disease following MERS-CoV infection[9,12].

Millions of pilgrims from more than 180 countries across the globe unite in the holiest sites of KSA during the Hajj pilgrimage [13]. Elderly pilgrims with different underlying medical conditions and socioeconomic backgrounds from different parts of the world come in close contact during religious rituals in a closely defined area, most likely increasing susceptibility to respiratory tract infection[12,14,15]. More than 30% of pilgrims from Bangladesh are over 60 years of age [16]. Movement of these huge numbers of returning pilgrims might pose a potential risk of transmitting MERS-CoV in Bangladesh and other countries across the world. Taking all these into account, the International Health Regulations (IHR) Emergency Committee advised strengthening MERS-CoV surveillance capacities to ensure timely reporting of any identified cases in countries with returning pilgrims [17]. The Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control & Research (IEDCR) under the Bangladesh Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) is mandated to lead outbreak investigations, surveillance and disease containment in the country, hence responsible for MERS-CoV screening in pilgrims/ travelers returning from the Middle East with respiratory illness (S1 Text).

A study conducted in the United Kingdom reported that respiratory infections among returning pilgrims were mainly caused by influenza and other respiratory viruses, such as Adeno virus, Respiratory syncytial virus, Human metapneumovirus and Para influenza viruses other than MERS-CoV [18]. To determine if this is the case for Bangladesh, this study was conducted to detect the viral pathogens responsible for respiratory infections among returning Bangladeshi pilgrims and other travelers from the Middle East.

Materials and methods

Patients

From October 2013 to June 2016 pilgrims and people returning from the Middle East presented with respiratory symptoms and having an epidemiological link were enrolled through active screening at the point of entry. After risk assessment by the medical team, suspected patients were admitted to the Kurmitola General Hospital isolation unit. In addition, travelers arriving with no clinical presentation received a health card mentioning the sign and symptoms of MERS-CoV infection. Self reported cases who developed symptoms within 14 days of arrival were included in sample collection along with admitted patients. The health care providers were instructed to use WHO standard Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) including N95 masks during handling of the patients.

Samples

Upper respiratory tract (URT) nasal and throat swabs and lower respiratory tract (LRT) sputum were collected from 81suspected cases. Samples from self reported cases were collected in the sample collection room of IEDCR. Samples from hospitalized patients, samples were transported to the IEDCR Virology laboratory, using category A shipping regulations, in accordance with the WHO guidance on the Regulation for the transport of infectious agents 2013–14 [19].

Respiratory virus screening

Nucleic acid was extracted and purified from samples according to manufacturer’s instruction (Viral RNA/DNA mini kit, PureLink, life technologies, CA, USA). Real time qRT-PCR assays for detection of MERS-CoV RNA was performed by using TaqMan technology. Primers and probes for upstream of the envelope (UpE) and non-structural protein 2 (N2) gene were used, provided by Centers for Disease Control (CDC), USA (CDC, catalog # KT0136). The sensitivity and specificity of the RT-PCR assay kit is 100% [20]. In addition RT-PCR was done for detection of nucleic acid of other respiratory viruses such asinfluenza A with subtype, influenza B, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza virus types 1–4, human metapneumovirus, and adenoviruses [18]. Primers and probes for theserespiratory viruses were also supplied by CDC, Atlanta, USA. Ribonucleoprotein (RP) was used as internal control.

Ethical statement

The samples were collected from the patients for laboratory investigation includingdetection of MERS-CoV, who had respiratory illness and epidemiological link as an emergency response where ethical clearance is exempted. Informed written consent was taken from all patients or patient’s guardian in case of minor prior to sample collection for MERS-CoV testing.

Results

Patients

Depending upon the clinical manifestations and epidemiological link, 81 cases were included in the study (S1 Data). Of them 45 were male and 36 were female, with age ranging from 14 months to 81 years (mean age: 49 ± 14 years) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of 81 patients tested, October 2013 to June 2016.

| 0–16 years | 17–65 years | >65 years | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 0 | 41 | 4 | 45 (55.6%) |

| Female | 1 | 33 | 2 | 36 (44.4%) |

| Total | 1 (1.2%) | 74 (91.4%) | 6 (7.4%) | 81 (100%) |

Respiratory virus detection

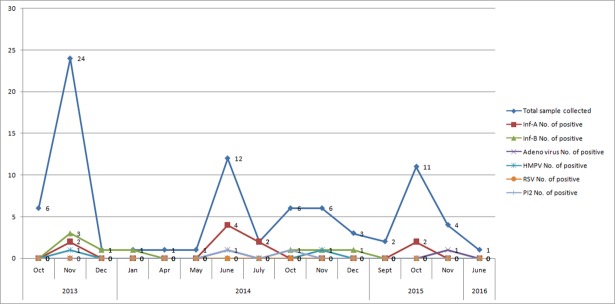

Of all the samples obtained from the 81 patients tested, none was positive for MERS-CoV. However, a viral etiology for clinical illness was found in 29.6% of cases (Fig 1). Among these positive samples, almost equal number of patients were found positive for influenza A (n = 10; either H1N1 or H3N2) and influenza B (n = 8). Additional respiratory pathogens detected were Adenovirus (2, 8%), human metapneumovirus (2, 8%) and parainfluenza 1–3 (2, 8%) (Fig 2).The highest number of samples were tested in October 2013 post-Hajj period (n = 24). During 2014 and 2015 the number of samples in the same time period was about half compared to 2013, 12 and 11 respectively. Up to June’2016 only one suspected case was tested and found negative for viral respiratory pathogens (Fig 3).

Fig 1. Total number of patients with a viral pathogen.

Fig 2. Respiratory viral pathogens detected in pilgrims and returning travelers.

Fig 3. Testing of respiratory viral pathogens in 2013 to 2016 by month.

Discussion

The emergence of various respiratory pathogens at different time points for instance, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona virus (SARS-CoV) in 2003 in China, H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009, and the emergence of another novel corona virus, MERS-CoV in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) in 2012, has engendered potential public health threats across the world [3,21,22].

The laboratory findings of this study of returning pilgrims from KSA and other travellers with symptoms of respiratory illness were found negative for MERS-CoV infection, but around 22% of them were infected by either influenza A or influenza B virus. Similar findings were observed among pilgrims from France in 2013[23]. The data from National Influenza Surveillance Bangladesh (NISB) revealed that, in the last five years the overall prevalence of influenza virus infection is 11%. Data also shows that the influenza season in Bangladesh starts in April and ends in September with peak in June-July [24]. However, the seasonality of influenza infection in KSA is different, beginning in September and peaking in November-December[25]. During this study period the Hajj was in the month of September and October. In the last four years pilgrims from Bangladesh received influenza vaccine recommended for Southern Hemisphere, as Northern Hemisphere vaccine is not available during that time. It is documented that influenza infection among vaccinated pilgrims is very common and may be due to mismatch strains[26]. This hypothesis, thus supports the higher prevalence of influenza infection among vaccinated Bangladeshi pilgrims in this study.

There was no evidence of MERS-CoV carriage among pilgrims from Bangladesh, suggesting no events of acquisition of MERS-CoV infection during the Hajj with other pilgrims and/ or contact with local people. Despite the small sample size compared to the overall Hajj pilgrim population (>1.9 million), lack of nasal carriage of MERS-CoV is evident, indicates that chance of viral transmission is low [27].

The challenges for laboratory diagnosis of MERS-CoV largely depend on the quality and type of respiratory tract specimens received[28]. Moreover, MERS-CoV causes a wide spectrum of clinical presentations in disease severity (mild to severe) which is associated with underlying co-morbid conditions [29]. Mild MERS-CoV infection may be missed among returning pilgrims if they recover spontaneously without attending any healthcare facilities. Thus, additional serological tests are required to determine the sero-conversion status to establish evidence of infection[30].

In order to detect and investigate any possible cases of MERS-CoV infection among returning pilgrims and travelers with epidemiological links, many countries, including Bangladesh, have established enhanced surveillance systems. Fortunately, none of the returning pilgrims were detected for MERS-CoV and few sporadic travel-associated MERS-CoV cases have been reported outside the Arabian Peninsula, mainly in Europe, North Africa, and Asia [18,31–33]. However few or no secondary cases were identified, with an exception in the Republic of Korea where the disease was spread to 185 cases from a single index case who had visited several countries in the Middle East[34].

To conclude, despite the lack of nasal carriage and lower transmission rate of this virus; higher incidence of morbidity and mortality and recent outbreak in South Korea with devastating outcome demands continuous monitoring and further investigations to ensure public health security.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(SAV)

Acknowledgments

All the suspected cases who provided the specimens.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Arabi Y, Balkhy H, Hajeer AH, Bouchama A, Hayden FG, et al. (2015) Feasibility, safety, clinical, and laboratory effects of convalescent plasma therapy for patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection: a study protocol. Springerplus 4: 709 doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1490-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Boheemen S, de Graaf M, Lauber C, Bestebroer TM, Raj VS, et al. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. MBio 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaki AM, Van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 367: 1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO (2015) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV).

- 5.Assiri A, McGeer A, Perl TM, Price CS, Al Rabeeah AA, et al. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med 369: 407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memish ZA, Zumla AI, Al-Hakeem RF, Al-Rabeeah AA, Stephens GM Family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N Engl J Med 368: 2487–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puzelli S, Azzi A, Santini MG, Di Martino A, Facchini M, et al. Investigation of an imported case of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in Florence, Italy, May to June 2013. Euro Surveill 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO (2015) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Summary of Current Situation, Literature Update and Risk Assessment.

- 9.WHO (December, 2016) WHO MERS-CoV Global Summary and risk assessment. WHO/MERS/RA/16.1 WHO/MERS/RA/16.1.

- 10.(MMWR) MaMWR (2014) First Confirmed Cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Infection in the United States, Updated Information on the Epidemiology of MERS-CoV Infection, and Guidance for the Public, Clinicians, and Public Health Authorities—May 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.WHO (2016) WHO MERS-CoV Global Summary and risk assessment.

- 12.Who Mers-Cov Research G (2013) State of Knowledge and Data Gaps of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Humans. PLoS Curr 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Memish ZA, Al-Rabeeah AA Public health management of mass gatherings: the Saudi Arabian experience with MERS-CoV. Bull World Health Organ 91: 899–899A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.132266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gautret P, Parola P, Brouqui P Relative risk for influenza like illness in French Hajj pilgrims compared to non-Hajj attending controls during the 2009 influenza pandemic. Travel Med Infect Dis 11: 95–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alzeer AH (2009) Respiratory tract infection during Hajj. Ann Thorac Med 4: 50–53. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.49412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bangladesh Hajj management portal MoRA (2013) satastics on Bangladeshi Pilgrim 2013.

- 17.WHO (2013) WHO Statement on the third meeting of the IHR Emergency committee concerning Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Wkly Epidemiol Rec 88: 435–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atabani SF, Wilson S, Overton-Lewis C, Workman J, Kidd IM, et al. (2016) Active screening and surveillance in the United Kingdom for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in returning travellers and pilgrims from the Middle East: a prospective descriptive study for the period 2013–2015. Int J Infect Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO (2012) Guidance on regulations for the Transport of Infectious Substances, 2013–2014

- 20.Lu X, Whitaker B, Sakthivel SKK, Kamili S, Rose LE, et al. (2014) Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR Assay Panel for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 52: 67–75. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02533-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, Chan P, Cameron P, et al. (2003) A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med 348: 1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser C, Donnelly CA, Cauchemez S, Hanage WP, Van Kerkhove MD, et al. (2009) Pandemic potential of a strain of influenza A (H1N1): early findings. Science 324: 1557–1561. doi: 10.1126/science.1176062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gautret P, Charrel R, Benkouiten S, Belhouchat K, Nougairede A, et al. Lack of MERS coronavirus but prevalence of influenza virus in French pilgrims after 2013 Hajj. Emerg Infect Dis 20: 728–730. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute of Epidemiology DCRI (2017) National Influenza Surveillance, Bangladesh.

- 25.Al-Hajjar S, Akhter J, Al Jumaah S, Qadri SH (1998) Respiratory viruses in children attending a major referral centre in Saudi Arabia. Annals of tropical paediatrics 18: 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashem AM (2016) Influenza immunization and surveillance in Saudi Arabia. Annals of thoracic medicine 11: 161 doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.180022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Memish ZA, Assiri A, Almasri M, Alhakeem RF, Turkestani A, et al. Prevalence of MERS-CoV Nasal Carriage and Compliance With the Saudi Health Recommendations Among Pilgrims Attending the 2013 Hajj. J Infect Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackay IM, Arden KE (2015) MERS coronavirus: diagnostics, epidemiology and transmission. Virol J 12: 222 doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0439-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Tawfiq JA, Assiri A, Memish ZA (2013) Middle East respiratory syndrome novel corona MERS-CoV infection. Epidemiology and outcome update. Saudi Med J 34: 991–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.CDC (2014) CDC Laboratory Testing for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV).

- 31.Gautret P, Benkouiten S, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA (2016) The spectrum of respiratory pathogens among returning Hajj pilgrims: myths and reality. Int J Infect Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pavli A, Tsiodras S, Maltezou HC (2014) Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): prevention in travelers. Travel Med Infect Dis 12: 602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sridhar S, Brouqui P, Parola P, Gautret P (2015) Imported cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome: an update. Travel Med Infect Dis 13: 106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prevention KCfDCa (2016) Corrigendum to "Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Outbreak in the Republic of Korea, 2015" [Volume 6, Issue 4, August 2015, 269–278]. Osong Public Health Res Perspect 7: 138 doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(SAV)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.