Abstract

Background

Nitric oxide signaling plays a key role in regulation of vascular tone and platelet activation. Here, we seek to understand the impact of a genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling on risk for cardiovascular diseases, thus informing the potential utility of pharmacologic stimulation of the nitric oxide pathway as a therapeutic strategy.

Methods

We analyzed the association of common and rare genetic variants in two genes that mediate nitric oxide signaling [Nitric Oxide Synthase 3 (NOS3) and Guanylate Cyclase 1, Soluble, Alpha 3 (GUCY1A3)] with a range of human phenotypes. We selected two common variants (rs3918226 in NOS3 and rs7692387 in GUCY1A3) known to associate with increased NOS3 and GUCY1A3 expression and reduced mean arterial pressure, combined them into a genetic score, and standardized this exposure to a 5 mm Hg reduction in mean arterial pressure. Using individual-level data from 335,464 participants in the UK Biobank and summary association results from seven large-scale genome wide association studies, we examined the effect of this nitric oxide signaling score on cardiometabolic and other diseases. We also examined whether rare loss-of-function mutations in NOS3 and GUCY1A3 were associated with coronary heart disease using gene sequencing data from the Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium (n=27,815).

Results

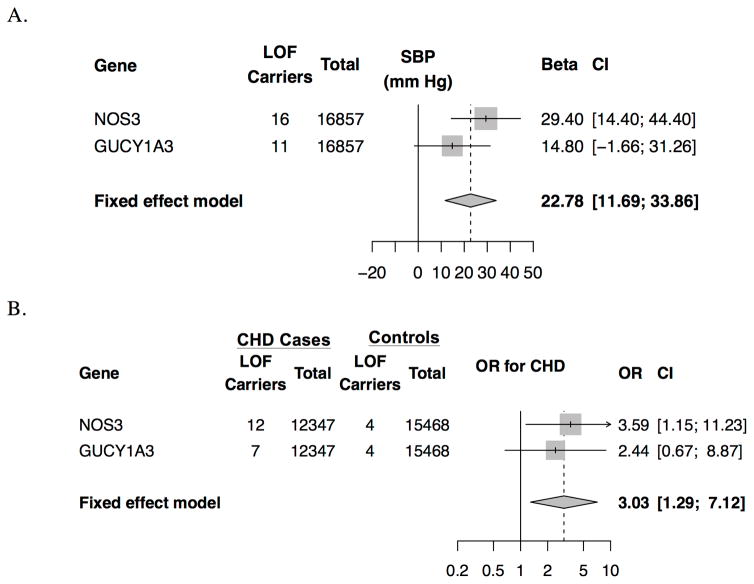

A genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling was associated with reduced risks of coronary heart disease [OR 0.37 95% CI 0.31, 0.45; p=5.5*10−26], peripheral arterial disease (OR 0.42 CI 0.26, 0.68; p=0.0005) and stroke (OR 0.53 CI 0.37, 0.76; p=0.0006). In a mediation analysis, the effect of the genetic score on decreased coronary heart disease risk extended beyond its effect on blood pressure. Conversely, rare variants that inactivate the NOS3 or GUCY1A3 genes were associated with a 23 mm Hg higher systolic blood pressure (CI 12, 34 mm Hg; p=5.6*10−5) and a three-fold higher risk of coronary heart disease (OR 3.03 CI 1.29, 7.12, p=0.01).

Conclusions

A genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling is associated with reduced risks of coronary heart disease, peripheral arterial disease and stroke. Pharmacologic stimulation of nitric oxide signaling may prove useful in the prevention or treatment of cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Genetics, nitric oxide, cardiovascular disease, nitric oxide synthase

Introduction

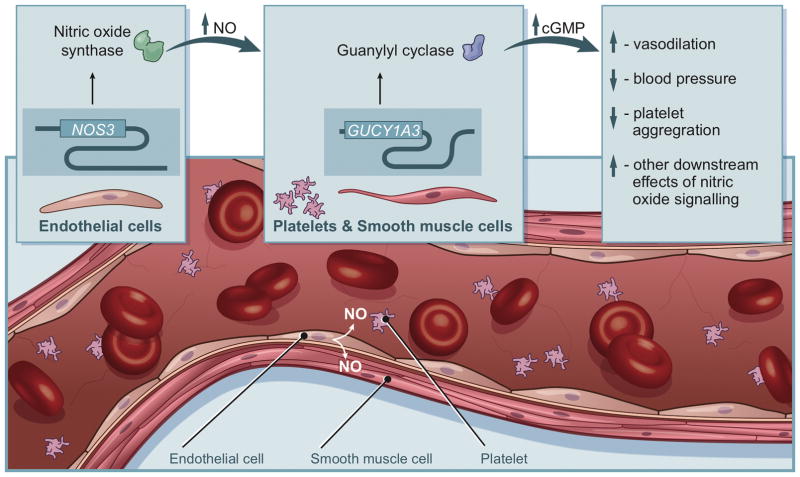

Nitric oxide signaling is a key regulator of vascular tone, blood pressure and platelet aggregation.1,2 Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), encoded by the gene NOS3, generates nitric oxide in the vascular endothelium (Figure 1).3 Nitric oxide acts as a signaling molecule to activate soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), a heterodimeric protein with one subunit encoded by the gene GUCY1A3.3,4 Cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) produced by sGC then activates downstream signaling molecules, leading to vasodilation, blood pressure lowering, inhibition of platelet aggregation and other cardiometabolic effects.5,6 NOS3 and GUCY1A3 are thus key mediators of nitric oxide signaling and its downstream effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Role of NOS3 and GUCY1A3 in nitric oxide signaling.

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase, encoded by the gene NOS3, generates nitric oxide in the vascular endothelium. Nitric oxide acts as a signaling molecule to activate soluble guanylyl cyclase, a heterodimeric protein with one subunit encoded by the gene GUCY1A3. Cyclic guanosine monophosphate produced by soluble guanylyl cyclase then activates downstream signaling molecules, leading to vasodilation, blood pressure lowering, inhibition of platelet aggregation and other cardiometabolic effects.

Previous studies have noted increased blood pressure and atherosclerotic burden in eNOS−/− knockout mice,7,8 while loss of sGC promotes thrombus formation.9 Common noncoding variants in the NOS3 and GUCY1A3 loci associate with blood pressure and coronary heart disease (CHD) in genome wide association studies, consistent with a role of nitric oxide signaling in regulation of arterial blood pressure.10–12 Furthermore, a rare coding variant in GUCY1A3 was identified as associating with early-onset myocardial infarction in a German family.9 These findings in mice and humans suggest that stimulation of nitric oxide signaling may be a useful therapeutic strategy for prevention of cardiovascular diseases.

DNA sequence variants in therapeutic target genes represent naturally-occurring, lifelong variation of the gene (i.e., experiments of nature). Consequently, if a genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling associates with reduced risk of cardiovascular and other diseases, these results would support the therapeutic hypothesis that pharmacologic stimulation of nitric oxide signaling (e.g., through soluble guanylyl cyclase stimulation13) will prevent and/or treat cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, if the association of nitric oxide signaling with coronary heart disease (CHD) risk is partially mediated through blood pressure-independent pathways, stimulation of nitric oxide signaling may represent an approach for CHD prevention independent of current blood pressure lowering therapies.

We therefore sought to use common and rare DNA sequence variants in NOS3 and GUCY1A3 to: (1) determine the effects of a genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling on a range of cardiometabolic and other diseases; (2) assess whether the effect of nitric oxide signaling on CHD is primarily mediated through blood pressure; and (3) determine if rare inactivating variants in NOS3 and GUCY1A3 that are predicted to reduce nitric oxide signaling associate with higher risk for CHD.

Methods

The data, analytic methods, and study materials is available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure, with access maintained by UK Biobank.14

Study design, data sources and study participants

Study design is shown in Supp. Figure 1. We used individual-level data from 335,464 individuals of European ancestry from the UK Biobank, a large population-based cohort (Supplemental Methods A). Characteristics of individuals in UK Biobank are provided (Supplemental Table 1). We supplemented this individual-level data with seven genome-wide association study (GWAS) consortia examining blood lipids, anthropometric traits, glycaemic traits, diabetes, CHD, migraine and renal dysfunction, all predominantly containing individuals of European descent (Supplemental Methods B and Supp. Table 2). Finally, we used gene sequence data from 27,815 participants from the Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium and 16,857 participants from the T2D GENES study15 to examine whether rare variants in the NOS3-GUCY1A3 pathway associate with blood pressure and CHD (Supplemental Methods C).

In our primary analysis, we examined the effect of a genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling on nine different cardiometabolic diseases: CHD, stroke, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, aortic stenosis, peripheral vascular disease, venous thromboembolism, diabetes and chronic kidney disease (Supplemental Table 3). We additionally examined the effect of a genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling on 16 quantitative traits (Supplemental Methods A and B): systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, waist-to-hip ratio adjusted for body mass index16, body mass index, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, two-hour glucose, hemoglobin A1C, serum creatinine-estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR), cystatin-C-estimated GFR, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC). All traits were standardized (that is, reported in standard deviation (SD) units) to facilitate comparisons among traits (Supplemental Methods B). Using the UK Biobank cohort, we conducted a phenome-wide association study for 26 additional diseases, including endocrine, renal, urological, gastrointestinal, neurological, musculoskeletal, respiratory and neoplastic disorders (Supplemental Table 3).

Analysis of the UK Biobank data was approved by the Partners Health Care institutional review board (protocol 2013P001840; application 7089). Informed consent was obtained from all participants by the UK Biobank.

Common variants in NOS3 and GUCY1A3

We leveraged common variants in the NOS3 and GUCY1A3 loci to characterize the effects of a genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling. Two common variants were selected as instruments for a genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling: a promoter variant of NOS3 (rs3918226; minor allele frequency 8%) and an intronic variant of GUCY1A3 (rs7692387; minor allele frequency 19%; Supp. Table 4). These variants were selected because: (1) they have been robustly associated with blood pressure (a downstream effect of nitric oxide signaling) and (2) they are located within the endothelial nitrate synthase-soluble guanylyl cyclase nitric oxide signaling pathway.17,18 Furthermore, the minor allele of rs7692387 has also recently been characterized to reduce GUCY1A3 expression via disruption of a ZEB1 transcription factor site.19 We examined the effect of these variants on NOS3 and GUCY1A3 expression levels in aortic and lung tissue in the Genotype-Tissue Expression project database20 (Supplemental Methods D) and the effect of these variants on mean arterial pressure in UK Biobank.

To examine the effects of increased nitric oxide signaling on cardiometabolic and other traits, we pooled rs3918226 and rs7692387 into an additive genetic score (individuals had 0 to 4 risk alleles). We derived this score by multiplying the number of risk alleles by the association of each allele with mean arterial pressure in UK Biobank (0.68 mm Hg for rs3918226 and 0.32 mm Hg for rs7692387). For example, if an individual had two risk alleles for rs3918226 and one risk allele for rs7692387, the genetic score was calculated as 2*0.68 mm Hg + 0.32 mm Hg = 1.68 mm Hg. Individuals missing one variant [either rs3918226 or rs7692387, n= 6036 (1.8%)] were imputed at the mean allele frequency for the variant prior to calculation of the genetic score. We standardized the nitric oxide signaling genetic score to a 5 mm Hg reduction in mean arterial pressure, corresponding to the effect of 1.5 mg of riociguat (a pharmacologic stimulator of soluble guanylate cyclase) on mean arterial pressure in a recent randomized controlled trial.13 The standardization was performed by dividing the genetic nitric oxide score by 5 mm Hg (e.g. 1.68 mm Hg/5 mm Hg = 0.34). We also report estimates standardized to a 2.5 mm Hg and 10 mm Hg lower mean arterial pressure to clarify the expected reduction in risk of cardiometabolic outcomes with different levels of nitric oxide signaling.

Rare predicted loss-of-function variants in NOS3 and GUCY1A3

Common non-coding variants may influence the expression of several nearby genes.21 Therefore, to provide complementary evidence that the NOS3-GUCY1A3 pathway influences blood pressure and CHD risk, we examined whether rare (minor allele frequency<1%) predicted loss-of-function variants in NOS3 and GUCY1A3 are associated with systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and CHD (Supplemental Methods C). Predicted loss-of-function variants were defined as: (1) insertions or deletions of DNA that modify the reading frame of protein translation (frameshift); (2) point mutations at conserved splice site regions which alter the splicing process (splice-site); or (3) point mutations that change an amino acid codon to a stop codon, leading to truncation of a protein (nonsense).

For blood pressure, we tested whether presence of a predicted loss-of-function variant in NOS3 and GUCY1A3 was associated systolic blood pressure or diastolic blood pressure in the Type 2 Diabetes Genetics Exome Sequencing study (n=16,857). We examined whether predicted loss-of-function variants were associated with systolic and diastolic blood pressure using the Genetic Association Interactive Tool on the Type 2 Diabetes Knowledge Portal.15 We used linear regression, adjusted for age, sex and five principal components of ancestry.

For CHD, we tested whether presence of a predicted loss-of-function variant was associated with CHD in the Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium (n = 27,815) study using logistic regression, adjusted for sex, five principal components of ancestry and a dummy variable for each cohort. To examine whether variants in the NOS3-GUCY1A3 pathway associate with CHD risk, we pooled the effect of predicted loss-of-function variants in NOS3 and GUCY1A3 on CHD using inverse variance weighted fixed effects meta-analysis.

Statistical analysis

For UK Biobank, we estimated the association of the nitric oxide signaling genetic score (standardized to a 5 mm Hg decrease in mean arterial pressure) with each outcome using a logistic regression model adjusting for age, sex, ten principal components of ancestry and a dummy variable for array type. For the summary-level data, this approach is equivalent to an inverse variance weighted fixed effects meta-analysis of the effect of each variant on traits or outcome of interest per 5 mm Hg lower mean arterial pressure. Tests for interaction between UK Biobank and summary-level estimates were calculated as the difference in log-transformed relative risks, as previously described.22

For our primary outcomes (nine cardiometabolic diseases), we set a Bonferroni adjusted level of significance of p=0.05/9=0.0056. For our secondary analyses of 16 cardiometabolic and pulmonary traits and our phenome wide association study of 26 phenotypes, we set a level of significance of p=0.05/42=0.001.

To examine whether an observed reduction in risk of CHD was caused by reduced blood pressure, a mediation analysis was conducted. An estimate of the causal effect of systolic blood pressure on CHD risk was derived from a recent genome wide association study (OR 1.21 CI 1.17, 1.24 per 5 mm Hg higher systolic blood pressure; Supplemental Methods E).11 This effect was then multiplied by the decrease in systolic blood pressure due to nitric oxide signaling to estimate the decrease in CHD risk mediated by systolic blood pressure. We then subtracted this estimate from the overall estimate of the nitric oxide genetic score with CHD to derive the remaining proportion of CHD risk unaccounted for by a decrease in systolic blood pressure. For example, if the OR for CHD for the genetic score was 0.5, but the OR for CHD from the systolic blood pressure decrease was 0.75, the OR for CHD independent of systolic blood pressure was calculated as exp(log(0.5) – log(0.75))=0.67.

All analyses were performed using R version 3.2.3 software (The R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

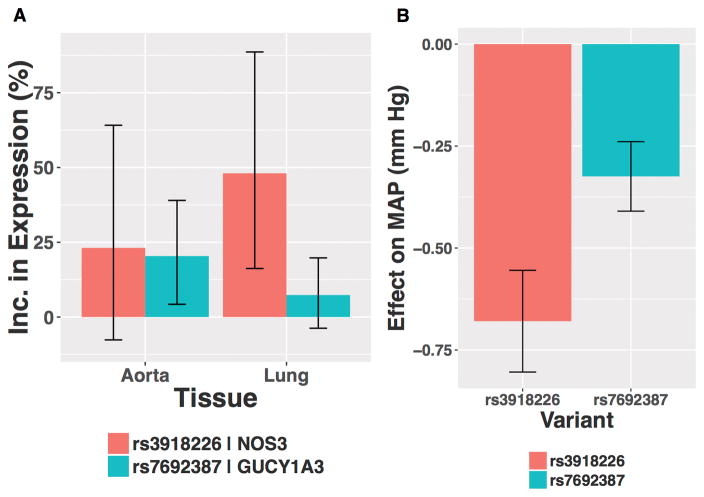

In the Genome Tissue Expression project database20, the C allele of rs3918226 was associated with increased NOS3 expression in lung tissue (48% higher expression, p=0.002) but was not significantly associated with NOS3 expression in aortic tissue (23% higher expression, p=0.21, Figure 2). The A allele of rs7692387 was associated with increased GUCY1A3 expression in aortic tissue (20% higher expression, p=0.012) but was not significantly associated with GUCY1A3 expression in lungs (7% higher expression, p=0.20). As expected for variants that enhance nitric oxide signaling, both rs3918226 and rs7692387 were associated with lower mean arterial pressure among UK Biobank participants [(0.68 mm Hg lower mean arterial pressure (p=1.3*10−26) and 0.32 mm Hg lower mean arterial pressure (p=8.3*10−14), respectively) (Figure 2)], replicating previously reported associations of these variants with blood pressure at genome wide significance.17,18

Figure 2. Association of rs3918226 and rs7692387 with (A) NOS3 or GUCY1A3 expression levels in aortic and lung tissue and (B) mean arterial pressure among UK Biobank participants.

Effect of variants on expression levels were obtained from the Genotype-Tissue Expression project. Effect of variants on mean arterial pressure were derived in UK Biobank using linear regression adjusted for age, sex, ten principal components of ancestry and array type (least-squares means estimates). rs3918226 was associated with significantly elevated NOS3 expression in lung. rs7692387 was associated with significantly elevated GUCY1A3 expression in aorta. MAP, mean arterial pressure.

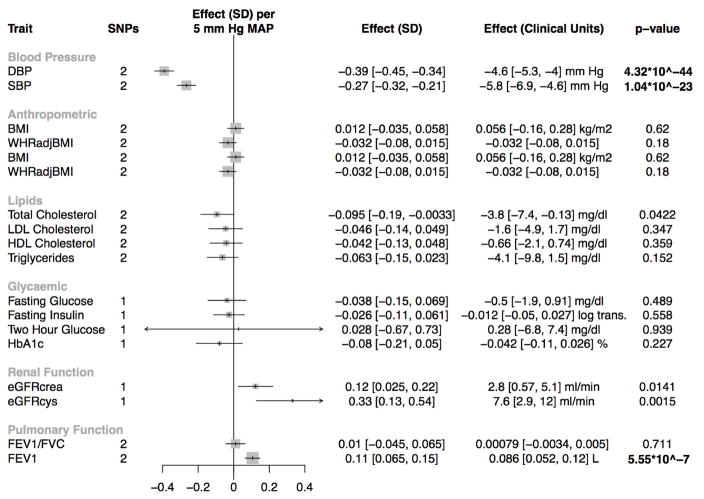

When combined into a nitric oxide signaling genetic score, and standardized to a 5 mm Hg reduction in mean arterial pressure, a genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling was nominally associated with improved renal function, as assessed by both cystatin-C-estimated GFR (7.6 ml/in; CI 2.9, 12 ml/min; p=0.0015) and creatinine-estimated GFR (2.8 ml/min; CI 0.57, 5.1 ml/min; p=0.014; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Association of the nitric oxide signaling genetic score with cardiometabolic traits (secondary outcomes).

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; eGFRcrea, serum creatinine-estimated glomerular filtration rate; eGFRcys, cystatin-C-estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; WHRadjBMI, waist-to-hip ratio adjusted for body mass index; LDL cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity. P-values that reach Bonferroni-adjusted level of statistical significance (p<0.001) are bolded.

Enhanced nitric oxide signaling was significantly associated with higher forced expiratory volume in 1 second (0.09 L; CI 0.05, 0.12 L; p = 5.6*10−7). We examined whether the association of a genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling with pulmonary function differed by baseline pulmonary function. No evidence of a trend by baseline pulmonary function for FEV1 was observed (p=0.34, respectively, Supplemental Figure 2). Enhanced nitric oxide signaling was not significantly associated with any other cardiometabolic traits, including glycaemic traits or blood lipids (Figure 3).

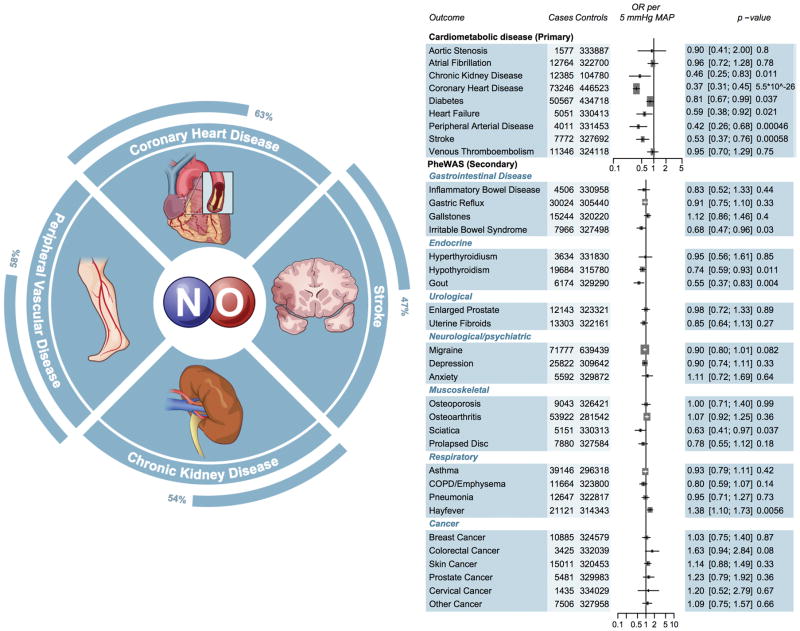

The genetic nitric oxide signaling score was significantly associated with three of the nine primary cardiometabolic outcomes. A genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling was associated with reduced risk of CHD (OR 0.36 CI 0.29, 0.46; p= 7.0*10−17; Supplemental Figure 3) in the CARDIoGRAMPlusC4D Consortium data. We replicated this association in UK Biobank participants (OR 0.39 CI 0.29, 0.52; p=1.1*10−10), with an overall pooled 63% reduction in CHD risk (OR 0.37 CI 0.31, 0.45; p=5.5*10−26; Figure 4).

Figure 4. Association of the nitric oxide signaling genetic score with cardiometabolic (primary) and other diseases (secondary).

Estimates were derived in UK Biobank using logistic regression, adjusted for age, sex, ten principal components and array type, with the exception of chronic kidney disease, which was derived using summary statistics from CKDGen. Estimates for coronary heart disease, diabetes and migraine additionally included summary estimates from CARDIOGRAM, DIAGRAM and IHGC, and were pooled using inverse variance weighted fixed effects meta-analysis. OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. CARDIOGRAM, Coronary ARtery DIsease Genome wide Replication and Meta-analysis; DIAGRAM, DIAbetes Genetics Replication And Meta-analysis; PheWAS, Phenome Wide Association Study. Significant p-values are bolded.

Beyond CHD, the nitric oxide signaling genetic score was associated with a reduced risk of peripheral arterial disease (OR 0.42 CI 0.26, 0.68; p=0.0005). This association persisted in a sensitivity analysis that excluded individuals with concomitant CHD (OR 0.41 CI 0.23, 0.74, p=0.003). The genetic score was also associated with a reduced risk of stroke (OR 0.53 CI 0.37, 0.76; p=0.0006) and a nominally (p<0.05) reduced risk of chronic kidney disease (OR 0.46 CI 0.25, 0.83; p =0.011), heart failure (OR 0.59 CI 0.38, 0.92; p=0.02) and diabetes (OR 0.81 CI 0.67, 0.99; p=0.037). In a phenome wide association study of 26 different diseases, enhanced nitric oxide signaling was not significantly associated with any other disease, including a variety of gastrointestinal diseases, musculoskeletal diseases and cancers (Figure 4). In sensitivity analyses, when standardized to a 2.5 mm Hg or 10 mm Hg lower mean arterial reduction, the nitric oxide signaling genetic score, was associated with a 39% (OR 0.61 CI 0.56, 0.67) and 86% lower risk of CHD (OR 0.14 CI 0.10, 0.20), respectively (Supplemental Figure 4).

When an interaction term between the NOS3 and GUCY1A3 genetic loci was included, no evidence of an interaction in the association of nitric oxide signaling with systolic blood pressure (p interaction = 0.76) or diastolic blood pressure (p interaction = 0.49) was observed. Similarly, no evidence of an interaction between the NOS3 and GUCY1A3 loci was observed for CHD (p interaction = 0.53).

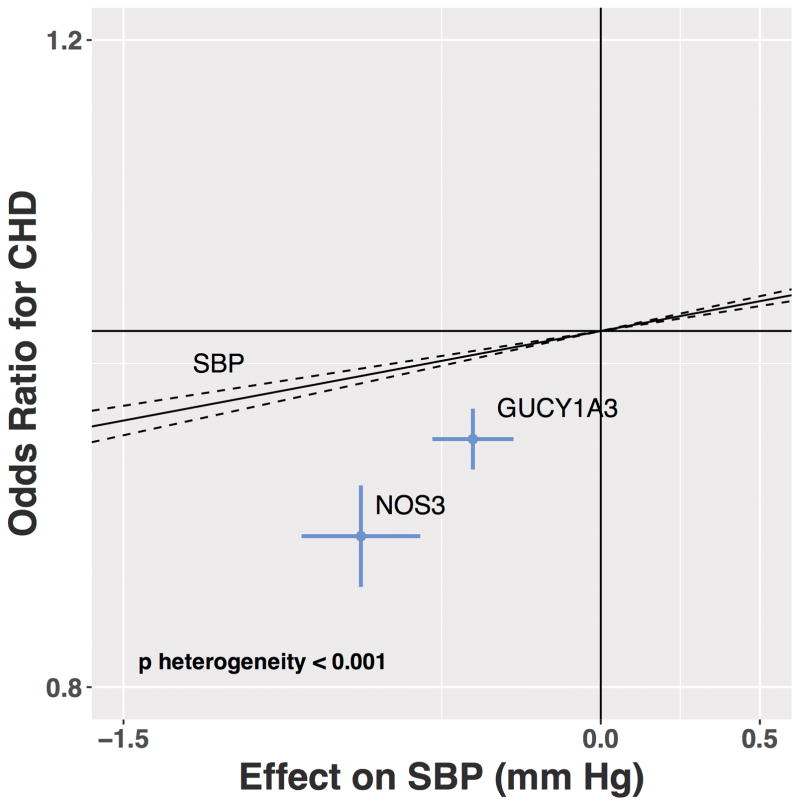

We performed mediation analysis to determine whether the degree to which the change in blood pressure associated with the nitric oxide signaling score explained the protective effect on CHD. Adjustment for the effect on systolic blood pressure led only to a modest attenuation of the association of the nitric oxide signaling genetic score with CHD (OR 0.37 CI 0.31, 0.45 prior to adjustment, OR 0.46 CI 0.38, 0.55 after adjustment; Supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that much of the decrease in CHD risk through increased nitric oxide signaling seems to be through pathways other than blood pressure. Indeed, the effect size of rs3918226 (NOS3) and rs7692387 (GUCY1A3) on CHD deviated substantially from an estimate based on just the systolic blood pressure effects of these variants (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Association of common variants in the NOS3 (rs3918226) and GUCY1A3 (rs7692387) loci with systolic blood pressure and coronary heart disease.

Solid line represents the estimated effect of systolic blood pressure on coronary heart disease from 54 distinct blood pressure loci from GWAS. A test for heterogeneity comparing the association for the genetic nitric oxide score to other blood pressure loci was significant (p<0.001). Estimates for systolic blood pressure was derived from UK Biobank with adjustment for age, sex and ten principal components. Estimates for coronary heart disease were derived from inverse variance fixed effects meta-analysis of CARDIOGRAM and UK Biobank. Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

In contrast to common variants that promote increased nitric oxide signaling, we sought to test the hypothesis that rare inactivating variants in NOS3 or GUCY1A3 would be associated with increased blood pressure and risk of CHD. 27 participants with predicted loss-of-function variants in NOS3 or GUCY1A3 were identified in the T2D GENES study (Supplemental Table 5). Presence of a predicted loss-of-function variant in NOS3 or GUCY1A3 was associated with increased systolic blood pressure (22.8 mm Hg CI 11.7, 33.9, p = 5.6*10−5, respectively; Figure 6) and diastolic pressure (9.7 mm Hg; CI 3.5, 15.9 mm Hg, p= 0.002, Supplemental Figure 6). 27 individuals with predicted loss-of-function variants were identified in Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium studies (Supp. Table 6). Prediced loss-of-function variants in the NOS3-GUCY1A3 pathway were associated with a three-fold higher risk of CHD (OR 3.03 CI 1.29, 7.12; p=0.01; Figure 6).

Figure 6. Association of rare, predicted loss-of-function variants in the NOS3-GUCY1A3 nitric oxide signaling pathway with systolic blood pressure and coronary heart disease.

(A) Estimates for systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure from T2D GENES study were derived using linear regression with adjustment for five principal components of ancestry. (B) Estimates for CHD from the Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium were derived using logistic regression, with adjustment for sex, cohort and five principal components of ancestry. Abbreviations: LOF, Loss-of-function; OR, odds ratio; CHD, coronary heart disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure

Discussion

A genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling was associated with reduced blood pressure, improved renal and pulmonary function, and significantly reduced risks of CHD (OR 0.37 CI 0.31, 0.45), peripheral arterial disease (OR 0.42 CI 0.26, 0.68) and stroke (OR 0.53 CI 0.37, 0.76). Mediation analysis suggested that this protective effect is mediated only in part by blood-pressure related pathways. In contrast, mutations predicted to truncate NOS3 or GUCY1A3 associated with higher blood pressure and an approximately three-fold higher risk of CHD.

These results permit several conclusions. First, stimulation of nitric oxide signaling may prevent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. The use of an oral soluble guanylyl cyclase stimulator has proven effective in the treatment of pulmonary hypertension13, reinforcing the potential to target this pathway using a small molecule approach. The 63% and 58% reductions in CHD and peripheral arterial disease observed in this study are likely to be of greater magnitude than what would be observed in a randomized trial of a nitric oxide signaling stimulator, as genetic estimates represent the effect of increased nitric oxide signaling over a lifetime rather than an intervention later in life and for a more limited duration.23 However, the significant and large risk reductions in cardiovascular disease observed in this study lend support to efforts to target nitric oxide signaling in the prevention or treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.1,24,25

Second, stimulation of nitric oxide signaling may represent a pathway for CHD prevention that is independent of current approaches. A genetic predisposition to nitric oxide signaling was not associated with lipid, glycemic, or anthropometric traits. Furthermore, the majority of the reduction in risk of CHD with increased nitric oxide signaling appeared to be independent of the variant’s impact on blood pressure. Consistent with these findings, a recent functional characterization of the lead GUCY1A3 variant rs7692387 observed carriers of the risk allele of this variant to have elevated levels of platelet aggregation and increased vascular smooth muscle cell migration upon stimulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase.19

Third, these results suggest that stimulation of nitric oxide signaling may improve renal and pulmonary function. A genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling was associated with higher glomerular filtration rate as determined by either cystatin C or creatinine, a finding that awaits further confirmation in larger studies. Increased nitric oxide signaling was also associated with improved pulmonary function. Although medications to stimulate of nitric oxide signaling is effective and approved for treatment of pulmonary hypertension1,13, these results suggest that stimulation of nitric oxide signaling may prove useful for other populations with reduced pulmonary function.

Our study has several limitations. First, we used common variants in the GUCY1A3 and NOS3 loci to estimate the phenotypic effects of increased nitric oxide signaling. It is possible that these variants may be in linkage disequilibrium with other variants that have phenotypic effects independent of nitric oxide signaling pathways. However, the common variants were associated with direct measurement of GUCY1A3 and NOS3 expression in vascular and pulmonary tissues, and we observed consistent effects of rare, predicted loss-of-function variants in GUCY1A3 and NOS3 on blood pressure and CHD, suggesting that the common variants mediated their effects through the NOS3-GUCY1A3 nitric oxide signaling pathway. Second, the phenome wide association study to determine the full spectrum of associations in the UK Biobank may have been underpowered to detect associations for some diseases. Third, our rare variant analysis was restricted to variants predicted to lead to loss of NOS3 or GUCY1A3 function; the prevalence of missense mutations that impair the NOS3-GUCY1A3 pathway may be much larger than the prevalence of rare, predicted loss-of-function variants observed in this study. Finally, the majority of participants in this study were of European ancestry and as such, these observations need validation in ancestries outside of Europe as ethnic differences in nitric oxide mediated responses have been previously reported.26

In conclusion, a genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling was associated with reduced risks of CHD and peripheral arterial disease and improved renal and pulmonary function. Stimulation of nitric oxide signaling may prove useful for the prevention and treatment of a range of diseases.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is new?

A genetic predisposition to enhanced nitric oxide signaling, as mediated by common variants in the NOS3 and GUCY1A3 genes, was associated with lower blood pressure and a reduced risk of coronary heart disease, peripheral arterial disease and stroke.

Rare variants that inactivate either the NOS3 or the GUCY1A3 gene were associated with increased blood pressure and higher risk of coronary heart disease.

What are the clinical implications?

The results suggest that pharmacologic stimulation of nitric oxide signaling may be an effective therapy for prevention or treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL127564 to SK) which had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. This project was conducted using the UK Biobank resource (project ID 7089). This project was also conducted using the Type 2 Diabetes Knowledge Portal resource which is funded by the Accelerating Medicines Partnership. REGICOR study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Innovation through the Carlos III Health Institute (Red Investigación Cardiovascular RD12/0042, PI09/90506), European Funds for Development (ERDF-FEDER), and by the Catalan Research and Technology Innovation Interdepartmental Commission (2014SGR240). Samples for the Leicester cohort were collected as part of projects funded by the British Heart Foundation (British Heart Foundation Family Heart Study, RG2000010; UK Aneurysm Growth Study, CS/14/2/30841) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR Leicester Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit Biomedical Research Informatics Centre for Cardiovascular Science, IS_BRU_0211_20033). NJS is supported by the British Heart Foundation and is a NIHR Senior Investigator. The Munich MI Study is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the context of the e:Med program (e:AtheroSysMed) and the FP7 European Union project CVgenes@target (261123). Additional grants were received from the Fondation Leducq (CADgenomics: Understanding Coronary Artery Disease Genes, 12CVD02).This study was also supported through the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft cluster of excellence “Inflammation at Interfaces” and SFB 1123. The Italian Atherosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology (ATVB) Study was supported by a grant from RFPS-2007-3-644382 and Programma di ricerca Regione-Università 2010–2012 Area 1–Strategic Programmes–Regione Emilia-Romagna. Funding for the exome-sequencing project (ESP) was provided by RC2 HL103010 (HeartGO), RC2 HL102923 (LungGO), and RC2 HL102924 (WHISP). Exome sequencing was performed through RC2 HL102925 (BroadGO) and RC2 HL102926 (SeattleGO). The JHS is supported by contracts HHSN268201300046C, HHSN268201300047C, HHSN268201300048C, HHSN268201300049C, HHSN268201300050C from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Dr. Wilson is supported by U54GM115428 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Exome sequencing in ATVB, PROCARDIS, Ottawa, PROMIS, Southern German Myocardial Infarction Study, and the Jackson Heart Study was supported by 5U54HG003067 (to Dr. Gabriel).

Footnotes

Disclosures

AVK is supported by a John S. LaDue Memorial Fellowship at Harvard Medical School, and a KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award from Harvard Catalyst funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (TR001100) and has received consulting fees from Merck and Amarin. PN reports funding from the John S. LaDue Memorial Fellowship at Harvard Medical School and has received consulting fees from Amarin. NOS reports funding from K08HL114642 and R01HL131961, has received a research grant from AstraZeneca and consulting fees from Regeneron. DJR has received consulting fees from Aegerion Pharmaceuticals, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Novartis; is an inventor on a patent related to lomitapide that is owned by the University of Pennsylvania and licensed to Aegerion Pharmaceuticals; and is a cofounder of Vascular Strategies and Staten Biotechnology. SK is supported by a research scholar award from Massachusetts General Hospital, the Donovan Family Foundation, and R01 HL127564; he has received grants from Bayer Healthcare, Aegerion Pharmaceuticals, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; and consulting fees from Merck, Novartis, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Leerink Partners, Noble Insights, Quest Diagnostics, Genomics PLC, and Eli Lilly and Company; and holds equity in San Therapeutics and Catabasis Pharmaceuticals. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1.Lundberg JO, Gladwin MT, Weitzberg E. Strategies to increase nitric oxide signalling in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:623–641. doi: 10.1038/nrd4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinhorn BS, Loscalzo J, Michel T. Nitroglycerin and Nitric Oxide--A Rondo of Themes in Cardiovascular Therapeutics. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:277–280. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1503311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Förstermann U, Closs EI, Pollock JS, Nakane M, Schwarz P, Gath I, Kleinert H. Nitric oxide synthase isozymes. Characterization, purification, molecular cloning, and functions. Hypertension. 1994;23:1121–1131. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mergia E, Friebe A, Dangel O, Russwurm M, Koesling D. Spare guanylyl cyclase NO receptors ensure high NO sensitivity in the vascular system. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1731–1737. doi: 10.1172/JCI27657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denninger JW, Marletta MA. Guanylate cyclase and the .NO/cGMP signaling pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1411:334–350. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nong Z, Hoylaerts M, Van Pelt N, Collen D, Janssens S. Nitric oxide inhalation inhibits platelet aggregation and platelet-mediated pulmonary thrombosis in rats. Circ Res. 1997;81:865–869. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knowles JW, Reddick RL, Jennette JC, Shesely EG, Smithies O, Maeda N. Enhanced atherosclerosis and kidney dysfunction in eNOS(−/−)Apoe(−/−) mice are ameliorated by enalapril treatment. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:451–458. doi: 10.1172/JCI8376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhlencordt PJ, Gyurko R, Han F, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Aretz TH, Hajjar R, Picard MH, Huang PL. Accelerated atherosclerosis, aortic aneurysm formation, and ischemic heart disease in apolipoprotein E/endothelial nitric oxide synthase double-knockout mice. Circulation. 2001;104:448–454. doi: 10.1161/hc2901.091399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erdmann J, Stark K, Esslinger UB, Rumpf PM, Koesling D, de Wit C, Kaiser FJ, Braunholz D, Medack A, Fischer M, Zimmermann ME, Tennstedt S, Graf E, Eck S, Aherrahrou Z, Nahrstaedt J, Willenborg C, Bruse P, Brænne I, Nöthen MM, Hofmann P, Braund PS, Mergia E, Reinhard W, Burgdorf C, Schreiber S, Balmforth AJ, Hall AS, Bertram L, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, Li S-C, März W, Reilly M, Kathiresan S, McPherson R, Walter U, Ott J, Samani NJ, Strom TM, Meitinger T, Hengstenberg C, Schunkert H CARDIOGRAM. Dysfunctional nitric oxide signalling increases risk of myocardial infarction. Nature. 2013;504:432–436. doi: 10.1038/nature12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvi E, Kutalik Z, Glorioso N, Benaglio P, Frau F, Kuznetsova T, Arima H, Hoggart C, Tichet J, Nikitin YP, Conti C, Seidlerova J, Tikhonoff V, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Johnson T, Devos N, Zagato L, Guarrera S, Zaninello R, Calabria A, Stancanelli B, Troffa C, Thijs L, Rizzi F, Simonova G, Lupoli S, Argiolas G, Braga D, D’Alessio MC, Ortu MF, Ricceri F, Mercurio M, Descombes P, Marconi M, Chalmers J, Harrap S, Filipovsky J, Bochud M, Iacoviello L, Ellis J, Stanton AV, Laan M, Padmanabhan S, Dominiczak AF, Samani NJ, Melander O, Jeunemaitre X, Manunta P, Shabo A, Vineis P, Cappuccio FP, Caulfield MJ, Matullo G, Rivolta C, Munroe PB, Barlassina C, Staessen JA, Beckmann JS, Cusi D. Genomewide association study using a high-density single nucleotide polymorphism array and case-control design identifies a novel essential hypertension susceptibility locus in the promoter region of endothelial NO synthase. Hypertension. 2012;59:248–255. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.181990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehret GB, Ferreira T, Chasman DI, Jackson AU, Schmidt EM, Johnson T, Thorleifsson G, Luan J, Donnelly LA, Kanoni S, Petersen A-K, Pihur V, Strawbridge RJ, Shungin D, Hughes MF, Meirelles O, Kaakinen M, Bouatia-Naji N, Kristiansson K, Shah S, Kleber ME, Guo X, Lyytikäinen L-P, Fava C, Eriksson N, Nolte IM, Magnusson PK, Salfati EL, Rallidis LS, Theusch E, Smith AJP, Folkersen L, Witkowska K, Pers TH, Joehanes R, Kim SK, Lataniotis L, Jansen R, Johnson AD, Warren H, Kim YJ, Zhao W, Wu Y, Tayo BO, Bochud M, Absher D, Adair LS, Amin N, Arking DE, Axelsson T, Baldassarre D, Balkau B, Bandinelli S, Barnes MR, Barroso I, Bevan S, Bis JC, Bjornsdottir G, Boehnke M, Boerwinkle E, Bonnycastle LL, Boomsma DI, Bornstein SR, Brown MJ, Burnier M, Cabrera CP, Chambers JC, Chang I-S, Cheng C-Y, Chines PS, Chung R-H, Collins FS, Connell JM, Döring A, Dallongeville J, Danesh J, de Faire U, Delgado G, Dominiczak AF, Doney ASF, Drenos F, Edkins S, Eicher JD, Elosua R, Enroth S, Erdmann J, Eriksson P, Esko T, Evangelou E, Evans A, Fall T, Farrall M, Felix JF, Ferrières J, Ferrucci L CHARGE-EchoGen Consortium, CHARGE-HF consortium, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, International Consortium for Blood Pressure. The genetics of blood pressure regulation and its target organs from association studies in 342,415 individuals. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1171–1184. doi: 10.1038/ng.3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CARDIoGRAMplusC4D Consortium. A comprehensive 1000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1121–1130. doi: 10.1038/ng.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghofrani H-A, Galiè N, Grimminger F, Grünig E, Humbert M, Jing Z-C, Keogh AM, Langleben D, Kilama MO, Fritsch A, Neuser D, Rubin LJ PATENT-1 Study Group. Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:330–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, Downey P, Elliott P, Green J, Landray M, Liu B, Matthews P, Ong G, Pell J, Silman A, Young A, Sprosen T, Peakman T, Collins R. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS medicine. 2015;12:e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchsberger C, Flannick J, Teslovich TM, Mahajan A, Agarwala V, Gaulton KJ, Ma C, Fontanillas P, Moutsianas L, McCarthy DJ, Rivas MA, Perry JRB, Sim X, Blackwell TW, Robertson NR, Rayner NW, Cingolani P, Locke AE, Fernandez Tajes J, Highland HM, Dupuis J, Chines PS, Lindgren CM, Hartl C, Jackson AU, Chen H, Huyghe JR, van de Bunt M, Pearson RD, Kumar A, Müller-Nurasyid M, Grarup N, Stringham HM, Gamazon ER, Lee J, Chen Y, Scott RA, Below JE, Chen P, Huang J, Go MJ, Stitzel ML, Pasko D, Parker SCJ, Varga TV, Green T, Beer NL, Day-Williams AG, Ferreira T, Fingerlin T, Horikoshi M, Hu C, Huh I, Ikram MK, Kim B-J, Kim Y, Kim YJ, Kwon M-S, Lee J, Lee S, Lin K-H, Maxwell TJ, Nagai Y, Wang X, Welch RP, Yoon J, Zhang W, Barzilai N, Voight BF, Han B-G, Jenkinson CP, Kuulasmaa T, Kuusisto J, Manning A, Ng MCY, Palmer ND, Balkau B, Stančáková A, Abboud HE, Boeing H, Giedraitis V, Prabhakaran D, Gottesman O, Scott J, Carey J, Kwan P, Grant G, Smith JD, Neale BM, Purcell S, Butterworth AS, Howson JMM, Lee HM, Lu Y, Kwak SH, Zhao W, Danesh J, Lam VKL T2D-Genes Consortium. The genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2016;536:41–47. doi: 10.1038/nature18642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emdin C, Khera AV, Natarajan P, Klarin D, Zekavat SM, Hsiao AJ, Kathiresan S. Genetic Association of Waist-to-Hip Ratio With Cardiometabolic Traits, Type 2 Diabetes, and Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA. 2017;317:626–634. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.21042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson T, Gaunt TR, Newhouse SJ, Padmanabhan S, Tomaszewski M, Kumari M, Morris RW, Tzoulaki I, O’Brien ET, Poulter NR, Sever P, Shields DC, Thom S, Wannamethee SG, Whincup PH, Brown MJ, Connell JM, Dobson RJ, Howard PJ, Mein CA, Onipinla A, Shaw-Hawkins S, Zhang Y, Davey Smith G, Day INM, Lawlor DA, Goodall AH, Fowkes FG, Abecasis GR, Elliott P, Gateva V, Braund PS, Burton PR, Nelson CP, Tobin MD, van der Harst P, Glorioso N, Neuvrith H, Salvi E, Staessen JA, Stucchi A, Devos N, Jeunemaitre X, Plouin P-F, Tichet J, Juhanson P, Org E, Putku M, Sõber S, Veldre G, Viigimaa M, Levinsson A, Rosengren A, Thelle DS, Hastie CE, Hedner T, Lee WK, Melander O, Wahlstrand B, Hardy R, Wong A, Cooper JA, Palmen J, Chen L, Stewart AFR, Wells GA, Westra H-J, Wolfs MGM, Clarke R, Franzosi MG, Goel A, Hamsten A, Lathrop M, Peden JF, Seedorf U, Watkins H, Ouwehand WH, Sambrook J, Stephens J, Casas JP, Drenos F, Holmes MV, Kivimäki M, Shah S, Shah T, Talmud PJ, Whittaker J, Wallace C, Delles C, Laan M, Kuh D, Humphries SE, Nyberg F, Cusi D, Roberts R, Newton-Cheh C Global-BPGen Consortium, Cardiogenics Consortium, Global BPgen Consortium. Blood pressure loci identified with a gene-centric array. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:688–700. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surendran P, Drenos F, Young R, Warren H, Cook JP, Manning AK, Grarup N, Sim X, Barnes DR, Witkowska K, Staley JR, Tragante V, Tukiainen T, Yaghootkar H, Masca N, Freitag DF, Ferreira T, Giannakopoulou O, Tinker A, Harakalova M, Mihailov E, Liu C, Kraja AT, Nielsen SF, Rasheed A, Samuel M, Zhao W, Bonnycastle LL, Jackson AU, Narisu N, Swift AJ, Southam L, Marten J, Huyghe JR, Stančáková A, Fava C, Ohlsson T, Matchan A, Stirrups KE, Bork-Jensen J, Gjesing AP, Kontto J, Perola M, Shaw-Hawkins S, Havulinna AS, Zhang H, Donnelly LA, Groves CJ, Rayner NW, Neville MJ, Robertson NR, Yiorkas AM, Herzig K-H, Kajantie E, Zhang W, Willems SM, Lannfelt L, Malerba G, Soranzo N, Trabetti E, Verweij N, Evangelou E, Moayyeri A, Vergnaud A-C, Nelson CP, Poveda A, Varga TV, Caslake M, de Craen AJM, Trompet S, Luan J, Scott RA, Harris SE, Liewald DCM, Marioni R, Menni C, Farmaki A-E, Hallmans G, Renstrom F, Huffman JE, Hassinen M, Burgess S, Vasan RS, Felix JF, Uria-Nickelsen M, Mälarstig A, Reilly DF, Hoek M, Vogt TF, Lin H, Lieb W, Traylor M, Markus HS, Highland HM, Justice AE METASTROKE Consortium, EchoGen consortium, CHARGE-Heart Failure Consortium, ExomeBP Consortium. Trans-ancestry meta-analyses identify rare and common variants associated with blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1151–1161. doi: 10.1038/ng.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessler T, Wobst J, Wolf B, Eckhold J, Vilne B, Hollstein R, Ameln von S, Dang TA, Sager HB, Rumpf PM, Aherrahrou R, Kastrati A, Bjoerkegren JLM, Erdmann J, Lusis AJ, Civelek M, Kaiser FJ, Schunkert H. Functional Characterization of the GUCY1A3 Coronary Artery Disease Risk Locus. Circulation. 2017;136:476–489. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.GTEx Consortium. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smemo S, Tena JJ, Kim K-H, Gamazon ER, Sakabe NJ, Gómez-Marín C, Aneas I, Credidio FL, Sobreira DR, Wasserman NF, Lee JH, Puviindran V, Tam D, Shen M, Son JE, Vakili NA, Sung H-K, Naranjo S, Acemel RD, Manzanares M, Nagy A, Cox NJ, Hui C-C, Gomez-Skarmeta JL, Nóbrega MA. Obesity-associated variants within FTO form long-range functional connections with IRX3. Nature. 2014;507:371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature13138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ. 2003;326:219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith GD, Ebrahim S. “Mendelian randomization”: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:1–22. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wobst J, Kessler T, Dang TA, Erdmann J, Schunkert H. Role of sGC-dependent NO signalling and myocardial infarction risk. J Mol Med. 2015;93:383–394. doi: 10.1007/s00109-015-1265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wobst J, Ameln von S, Wolf B, Wierer M, Dang TA, Sager HB, Tennstedt S, Hengstenberg C, Koesling D, Friebe A, Braun SL, Erdmann J, Schunkert H, Kessler T. Stimulators of the soluble guanylyl cyclase: promising functional insights from rare coding atherosclerosis-related GUCY1A3 variants. Basic Res Cardiol. 2016;111:51. doi: 10.1007/s00395-016-0570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cardillo C, Kilcoyne CM, Cannon RO, Panza JA. Attenuation of cyclic nucleotide-mediated smooth muscle relaxation in blacks as a cause of racial differences in vasodilator function. Circulation. 1999;99:90–95. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.