Abstract

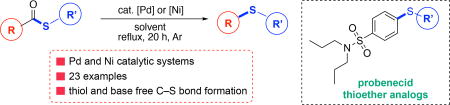

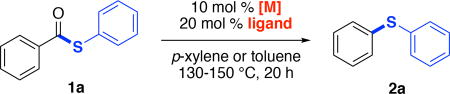

This Letter describes the development of a catalytic decarbonylative C–S coupling reaction that transforms thioesters into thioethers. Both Pd- and Ni-based catalysts are developed and applied to the construction of diaryl, aryl-alkyl, and heterocycle-containing thioethers.

Graphical abstract

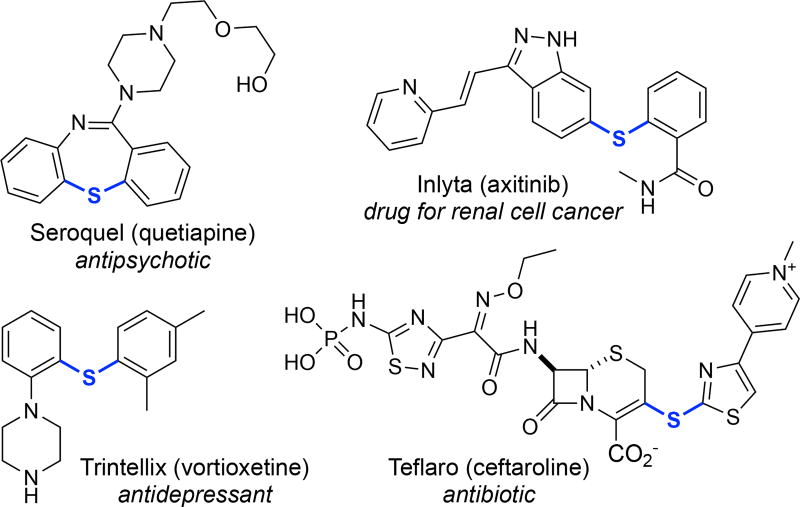

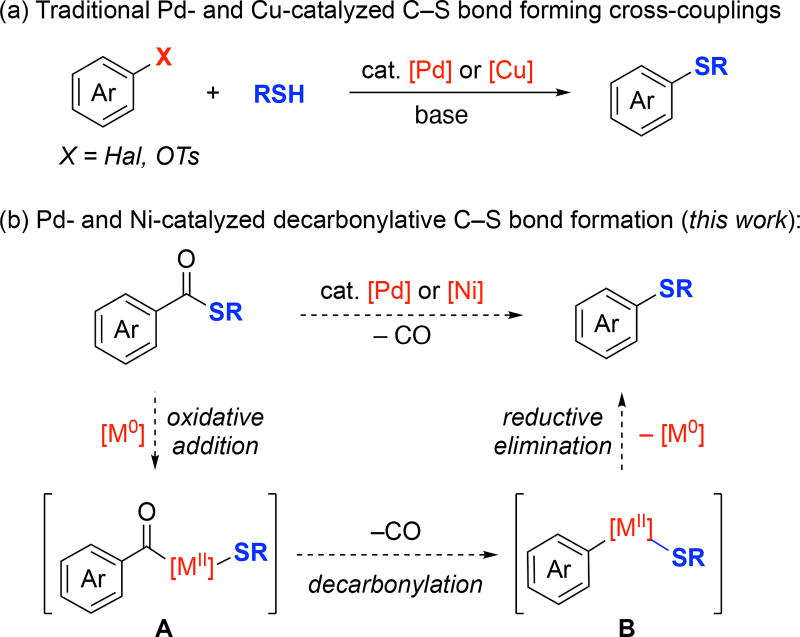

The aryl thioether functional group appears in a variety of pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals.1 For instance, a number of top-selling drugs,2 including Seroquel,3 Trintellix,4 Teflaro,5 and Inlyta,6 contain aryl thioether moieties (Figure 1). Aryl thioethers are most commonly prepared via the coupling of an aryl halide or pseudohalide with a thiol in the presence of base.7–10 With electron deficient aryl halides, these reactions often proceed via an uncatalyzed SNAr pathway,7 while Pd or Cu catalysis8 is commonly employed to forge the C–S bond with electron rich (hetero) aryl halides (Figure 2a).

Figure 1.

Examples of pharmaceuticals containing aryl thioethers.

Figure 2.

Transition metal-catalyzed synthesis of aryl thioethers by (a) traditional cross-coupling reaction, and (b) decarbonylation of thioesters.

In this Letter, we report an alternate approach to aryl thioethers, involving a metal-catalyzed intramolecular decarbonylative coupling of thioesters (Figure 2b). This process offers several advantages over conventional aryl halide/thiol cross-couplings. First, carboxylic acids (the precursors to thioesters) are often more readily available and less expensive than their aryl halide counterparts.11–14 Second, this transformation proceeds under base-free conditions and without the requirement for exogeneous thiol15 nucleophiles.16 Finally, we demonstrate that both Pd and Ni complexes are competent catalysts for this transformation, and further that they exhibit complementary reactivity and selectivity profiles with some substrates.

At the outset of our studies, we noted sporadic literature reports of metal-mediated decarbonylative thioetherification reactions.17–19 However, most prior examples employed stoichiometric quantities of Ni or Rh complexes. Furthermore, the reported reactions were demonstrated with a narrow scope of unfunctionalized substrates. Our work in this area was inspired by recent reports of the Niand/ or Pd-catalyzed intramolecular decarbonylation of aryl esters20 and aroyl chlorides21 to form C(sp2)–O and C(sp2)–Cl bonds, respectively. As shown in Figure 2b, we hypothesized that a similar process involving: (i) oxidative addition of a thioester to form an acyl metal thiolate (A), (ii) decarbonylation to form an aryl thiolate intermediate (B), and finally (iii) C–S bond-forming reductive elimination would enable the catalytic formation of diverse thioether products.

We initiated our studies with S-phenyl benzene thiolate 1a as the substrate. Our previous work on the decarbonylative coupling of aroyl chlorides showed that Pd complexes bearing bulky mono-phosphine ligands (e.g., P(o-tol)3 and BrettPhos) were the most effective catalysts. Thus, we initially explored the use of 10 mol % of Pd[P(o-tol)3]2 as the catalyst. As shown in Table 1, entry 1, these conditions afforded the desired product, diphenylsulfide 2a, in 28% yield in xylene at 150 °C. We next explored the use of Pd[P(o-tol)3]2 in conjunction with various mono- and bisphosphine ligands.22 As shown in Table 1, many of these ligands afforded improvements in yield, and the best result (78% yield) was obtained with the sterically bulky monophosphine PAd2Bn (entry 7).

Table 1.

Evaluation of Ligands for Pd- and Ni-catalyzed Decarbonylative Thioetherificationa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| entry | [M] | ligand (L) | L (mol %) |

2a (% yield)b |

| 1 | Pd[P(o-tol3)]2 | none | 0 | 28 |

| 2 | Brettphos | 10 | 58 | |

| 3 | dppe | 20 | 19 | |

| 4 | dppf | 20 | 61 | |

| 5 | tBuXantphos | 20 | 15 | |

| 6 | PAd2n-Bu | 20 | 67 | |

| 7 | PAd2Bn | 20 | 78 | |

|

| ||||

| 8 | Ni(cod)2 | PAd2Bn | 20 | 85 |

| 9 | P(n-Bu)3 | 20 | 92 | |

| 10 | PCy3 | 20 | >99 | |

Conditions: phenyl thiolate 1a (0.05 mmol), [M] (0.005 mmol, 0.1 equiv), ligand (0.01 mmol, 0.2 equiv). Entries 1–7 were performed in p-xylene (0.2 M), 150 °C, 20 h; entries 8–10 were performed in toluene, 130 °C, 20 h. See the Supporting Information for additional details.

GC yields obtained using neopentylbenzene as an internal standard.

We also pursued an analogous Ni-catalyzed reaction, since Ni-based catalysts have been much more widely used for decarbonylative couplings than their Pd analogues.23 The combination of 10 mol % of Ni(cod)2, and 20 mol % of PAd2Bn (the optimal ligand for the Pd system) in toluene at 130 °C afforded 2a in 85% yield. Furthermore, switching to PCy3 resulted in the formation of 2a in nearly quantitative yield (entry 10).

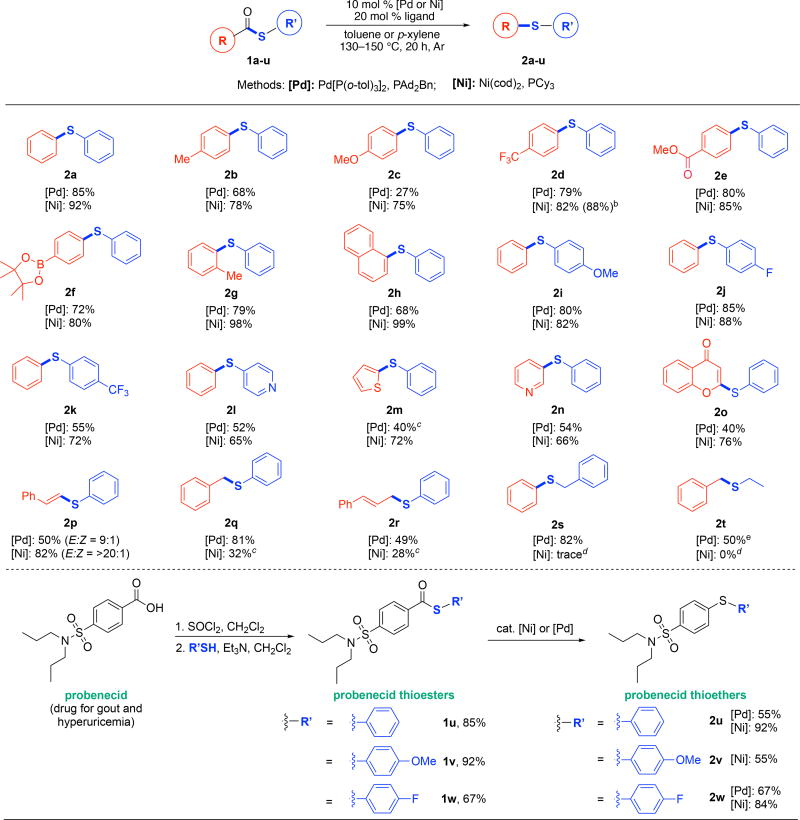

We next examined the scope of these Pd- and Nicatalyzed C–S coupling reactions. As shown in Scheme 1, substrates bearing electron-donating and electron withdrawing substituents on the thiol-derived fragment underwent high yielding decarbonylative thioetherification to afford products 2i-l under both Pd and Ni catalysis. A wide variety of substituents were well-tolerated on the carboxylic acid-derived portion of the substrate. For instance, benzylic C–H bonds (2b), carboxylic acid esters (2e), and boronate esters (2f) were compatible with the reaction conditions. Notably, the low (27%) yield observed with 4-anisoyl phenylthiolate 2c under Pd catalysis is due to the formation of diaryl sulfides as by-products.24 In contrast, under Ni catalysis 2c was obtained in 75% yield. Sterically hindered thioesters also reacted to form the corresponding thioether products (2g,h), and the Ni catalyst provided higher yields with these substrates. Finally, heterocycles including thiophene (2m), pyridine (2n), and chromenone (2o) were well tolerated, particularly with the Ni catalyst.

Scheme 1.

Scope of Pd and Ni-Catalyzed Decarbonylative Thioetherificationa

aConditions: with [Pd]: substrate 1 (0.3 mmol, 1 equiv), Pd[P(o-tol)3]2 (0.03 mmol, 0.1 equiv), PAd2Bn (0.06 mmol, 0.2 equiv) in p-xylene (0.2 M) with 5 Å molecular sieves at 150 °C. With [Ni]: substrate (0.3 mmol, 1 equiv), Ni(cod)2 (0.03 mmol, 0.1 equiv), PCy3 (0.06 mmol, 0.2 equiv) in toluene (0.2 M) at 130 °C. Isolated yields. For experimental details, see the Supporting Information. bIsolated yield from 1.0 mmol scale. cGC yields obtained from 0.05 mmol scale substrate using neopentyl benzene as internal standard. dBased on 1H NMR and GCMS analysis of the crude mixture. eYield based on 1H NMR of the crude mixture, 2t was found inseparable with starting material.

The decarbonylation of S-phenyl (E)-3-phenylprop-2-enethioate proceeded to form 2p under both Pd and Ni catalysis with retention of the olefin geometry. However, the E/Z ratio in the product varied significantly as a function of metal. Under Pd catalysis, 2p was obtained as a 9:1 mixture of the E/Z isomers, while the Ni catalyst afforded the product with an E/Z ratio of >20:1. Benzylic (2q) and allylic (2r) thioethers were formed in moderate to high yields from S-phenyl 2-phenylethanethioate and S-phenyl (E)-4-phenylbut-3-enethioate, respectively. With these two substrates, the Pd catalyst afforded significantly higher yields than the Ni. Alkyl thioesters were also found compatible under the Pd catalysis forming alkyl thioether products 2s and 2t in good yields. However, these reactions did not proceed under Ni catalysis.

We also applied this method to the functionalization of the carboxylic acid-containing drug, probenecid.25 A series of probenecid thioesters (1s-u) were prepared and then subjected to the optimal Ni and Pd catalytic conditions. As summarized in Scheme 1, these transformations afforded thioether derivatives 2s-u in good to excellent yields, highlighting the potential of this transformation for the late stage derivatization of bioactive carboxylic acids.

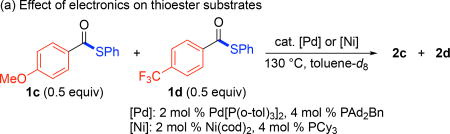

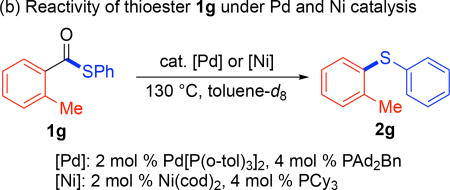

A final set of experiments was conducted to probe the relative reactivity of thioester substrates with the two different catalyst systems. First, a 1:1 mixture of 1c and 1d was heated at 130 °C under Pd or Ni catalysis (Table 2a). The reactions were analyzed by 1H and 19F NMR spectroscopy after 0.5 and 2 h to assay both the yield and ratio of aryl thioether products at each time point. As summarized in Table 2, 1d (bearing an electron withdrawing para-trifluoromethyl substituent) reacted faster than 1c (bearing an electron donating para-methoxy substituent) under both Pd and Ni catalysis. However, the Pd catalyst afforded lower overall yield and higher selectivity for 1d at both time points. We next examined the ortho-methyl-substituted thioester substrate 1g with both catalysts (Table 2b). These studies revealed that this relatively sterically hindered substrate undergoes much faster reaction with the Pd catalyst, affording >99% yield of thioether 2g after just 0.5 h. In contrast, the Ni catalyst afforded 2g in just 40% yield under analogous conditions. These studies provide preliminary insights into the different electronic/steric preferences of the two catalyst systems.

Table 2.

Competition experiments of various thioesters under Pd and Ni methodsa

| (a) Effect of electronics on thioester substrates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

| ||||

| entry | [M]; t (h) |

2c+2d (% yield) (ratio 2c:2d)b |

unreacted 1c (%)b |

unreacted 1d (%)b |

| 1 | [Pd]; 0.5 | 18 (1:99) | >49 | 32 |

| 2c | [Pd]; 2 | 35 (4:96) | 48 | 12 |

| 3 | [Ni]; 0.5 | 31 (6:94) | 48 | 21 |

| 4 | [Ni]; 2 | 49 (9:91) | 46 | 5 |

| (b) Reactivity of thioester 1g under Pd and Ni catalysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

|

| |||

| entry | [M]; t (h) | 2g (% yield)b | unreacted 1g (%)b |

| 1 | [Pd]; 0.5 | >99 | <1 |

| 2c | [Pd]; 2 | >99 | <1 |

| 3 | [Ni]; 0.5 | 40 | 60 |

| 4 | [Ni]; 2 | 70 | 30 |

Conditions: (a) 1c (0.05 mmol), 1d (0.05 mmol), [M] (0.002 mmol), ligand (0.004 mmol), toluene-d8, 130 °C, 0.5 and 2 h. (b) 1g (0.1 mmol), [M] (0.002 mmol), ligand (0.004 mmol), toluene-d8, 130 °C, 0.5 and 2 h.

Ratio and yield analyses were obtained by 1H and 19F NMR.

Unwanted biarylsulfide byproducts (~5%) were observed (ref 24). See the Supporting Information for additional details.

In summary, this Letter describes the development, optimization, and scope of the Pd and Ni-catalyzed intramolecular decarbonylative conversion of thioesters to thioethers. This method provides access to diaryl thioethers, heteroaryl thioethers, and aryl-alkyl thioethers under base- and thiol-free conditions. In general, the Pd and Ni catalysts exhibit similar substrate scopes, but several complementarities are demonstrated with respect to the selectivity, yields, and reaction rates with each of the two catalyst systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support from NIH NIGMS (GM073836) as well as the Danish National Research Foundation (Carbon Dioxide Activation Center; CADIAC). L.W. thanks UM-ICIQ Global Engagement Program for fellowship.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

- Experimental details, characterization, and NMR data for isolated compounds (PDF)

References

- 1.(a) Mellah M, Voituriez A, Schulz E. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:5133. doi: 10.1021/cr068440h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chauhan P, Mahajan S, Enders D. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:8807. doi: 10.1021/cr500235v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ilardi EA, Vitaku E, Njardarson JT. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:2832. doi: 10.1021/jm401375q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Riedel M, Müller N, Strassnig M, Spellmann I, Severus E, Möller H-J. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2007;3:219. doi: 10.2147/nedt.2007.3.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gunasekara NS, Spencer CM. CNS Drugs. 1998;9:325. doi: 10.2165/00023210-199809040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connolly KR, Thase ME. Exp. Opin. Pharma. 2012;17:421. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2016.1133588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding HX, Liu KK–C, Sakya SM, Flick AC, O’Donnell CJ. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:2795. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chekal BP, Guinness SM, Lillie BM, McLaughlin RW, Palmer CW, Post RJ, Sieser JE, Singer RA, Sluggett GW, Vaidyanathan R, Withbroe GJ. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2014;18:266. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Peach ME. In: The Chemistry of the Thiol Group. Patai S, editor. John Wiley & Sons; London: 1974. p. 721. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yin J, Pidgeon C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:5953. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Beletskaya IP, Ananikov VP. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1596. doi: 10.1021/cr100347k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Eichman CC, Stambuli JP. Molecules. 2011;16:590. doi: 10.3390/molecules16010590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bichler P, Love JA. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2010;31:39. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hartwig JF. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1534. doi: 10.1021/ar800098p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kondo T, Mitsudo T. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:3205. doi: 10.1021/cr9902749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For examples of photo-induced C–S bond formation: Uyeda C, Tan Y, Fu GC, Peters JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:9548. doi: 10.1021/ja404050f.Oderinde MS, Frenette M, Robbins DW, Aquila B, Johannes JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:1760. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11244.Jouffroy M, Kelly CB, Molander GA. Org. Lett. 2016;18:876. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00208.

- 10.Organocatalytic or metal-free methods for carbon-sulfur bond construction include ref 1b as well as: Wagner AM, Sanford MS. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:2263. doi: 10.1021/jo402567b.Liu B, Lim C-H, Miyake GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:13616. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b07390.

- 11.For selected recent examples of decarboxylative coupling reactions of carboxylic acids see: Gooßen LJ, Deng G, Levy LM. Science. 2006;313:662. doi: 10.1126/science.1128684.Gooßen LJ, Rodríguez N, Gooßen K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:3100. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704782.Welin ER, Le C, Arias-Rotondo DM, McCusker JK, MacMillan DWC. Science. 2017;355:380. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2490.Johnston CP, Smith RT, Allmendinger S, MacMillan DWC. Nature. 2016;536:322. doi: 10.1038/nature19056.Qin T, Malins LR, Edwards JT, Merchant RR, Novak AJE, Zhong JZ, Mills RB, Yan M, Yuan C, Eastgate MD, Baran PS. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;129:266. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609662.Perry GJP, Quibell JM, Panigrahi A, Larrosa I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:11527. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b05155.

- 12.For examples of decarbonylative coupling reactions of esters, see: Gooßen LJ, Paetzold J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:1237. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020402)41:7<1237::aid-anie1237>3.0.co;2-f.Gooßen LJ, Paetzold J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:1665.Gooßen LJ, Paetzold J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:1095. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352357.Amaike K, Muto K, Yamaguchi J, Itami K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:13573. doi: 10.1021/ja306062c.Correa A, Cornella J, Martin R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:1878. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208843.Muto K, Yamaguchi J, Musaev DG, Itami K. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7508. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8508.LaBerge NA, Love JA. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015:5546.Pu X, Hu J, Zhao Y, Shi Z. ACS Catal. 2016;6:6692.

- 13.For examples of decarbonylative coupling reactions of amides, see: Shi S, Szostak M. Org. Lett. 2017;19:3095. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01199.Meng G, Szostak M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:14518. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507776.Hu J, Zhao Y, Liu J, Zhang Y, Shi Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:8718. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603068.

- 14.For an example of the decarbonylation of thioesters and formation of C–B bonds, see: Ochiai H, Uetake Y, Niwa T, Hosoya T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56:2482. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611974.

- 15.For examples of thiol-free thioetherifications: Reeves JT, Camara K, Han ZS, Xu Y, Lee H, Busacca CA, Senanayake CH. Org. Lett. 2014;16:1196. doi: 10.1021/ol500067f.Li Y, Pu J, Jiang X. Org. Lett. 2014;16:2692. doi: 10.1021/ol5009747.Lin Y-M, Lu G-P, Wang G-X, Yi W-B. J. Org. Chem. 2017;82:382. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02459.

- 16.(a) Fernández-Rodríguez MA, Shen Q, Hartwig JF. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:7782. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fernández-Rodríguez MA, Hartwig JF. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:1663. doi: 10.1021/jo802594d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Hauptmann H, Walter WF, Marino C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958;80:5832. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wenkert E, Chianelli D. J. Chem Soc., Chem. Commun. 1991:627. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kundu S, Brennessel WW, Jones WD. Organometallics. 2011;30:5147. [Google Scholar]

- 18.A few reports have described the Pd-catalyzed decarbonylation of thioesters. However, these were limited to a narrow range of substrates. Osakada K, Yamamoto T, Yamamoto A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:6321.Kato T, Kuniyasu H, Kajiura T, Minami Y, Ohtaka A, Kinomoto M, Terao J, Kurosawa H, Kambe N. Chem. Commun. 2006:868. doi: 10.1039/b515616e.

- 19.In the presence of 5 mol % of Pd(PPh3)4 in toluene at reflux, S-phenyl benzene thiolate was reported to react to form diphenyl sulfide in 40% yield. This was reported in the context of the Pd-catalyzed carbothiolation of alkynes: Sugoh K, Kuniyasu H, Sugae T, Ohtaka A, Takai Y, Tanaka A, Machino C, Kambe N, Kurosawa H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5108. doi: 10.1021/ja010261o.

- 20.Takise R, Isshiki R, Muto K, Itami K, Yamaguchi J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:3340. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malapit CA, Ichiishi N, Sanford MS. Org. Lett. 2017;19:4142. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Other ligands, solvents and reaction temperatures were evaluated; see the Supporting Information for complete details.

- 23.See Ni-catalyzed decarbonylation examples from refs 12–14.

- 24.For examples of aryl C–S bond cleavage and cross-coupling with Pd or Ni: Iwasaki M, Topolovčan N, Hu H, Nishimura Y, Gagnot G, Na nakorn R, Yuvacharaskul R, Nakajima K, Nishihara Y. Org. Lett. 2016;18:1642. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00503.Shimizu D, Takeda N, Tokitoh N. Chem. Commun. 2006:177. doi: 10.1039/b513339d.Wenkert E, Ferreira TW, Michelotti EL. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1979:636.Malapit CA, Visco MD, Reeves JT, Busacca CA, Howell AR, Senanayake CH. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015;357:2199.

- 25.D’Ascenzio M, Carradori S, Secci D, Vullo D, Ceruso M, Akdemir A, Supuran CT. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:3982. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.