Abstract

The Emotional Interrupt Task (EIT) has been used to probe emotion processing in healthy and clinical samples; however, research exploring the stability and reliability of behavioral measures and event-related potentials (ERPs) elicited from this task is limited. Establishing the psychometric properties of the EIT is critical, particularly as phenotypes and biological indicators may represent trait-like characteristics that underlie psychiatric illness. To address this gap, test-retest stability and internal consistency of behavioral indices and ERPs resulting from the EIT in healthy, female youth (n = 28) were examined. At baseline, participants were administered the EIT while high-density 128-channel electroencephalography data were recorded to probe the late positive potential (LPP). One month later, participants were re-administered the EIT. Four principal findings emerged. First, there is evidence of an interference effect at baseline, as participants showed a slower reaction time for unpleasant and pleasant images relative to neutral images, and test-retest of behavioral measures was relatively stable over time. Second, participants showed a potentiated LPP to unpleasant and pleasant images compared to neutral images, and these effects were stable over time. Moreover, in a test of the difference waves (unpleasant-neutral versus pleasant-neutral), there was sustained positivity for unpleasant images. Third, behavioral measures and LPP demonstrated excellent internal consistency (odd/even correlations) across conditions. Fourth, highlighting important age-related differences in LPP activity, younger age was associated with larger LPP amplitudes across conditions. Overall, these findings suggest that the LPP following emotional images is a stable and reliable marker of emotion processing in healthy youth.

Introduction

Emotions are complex psychological and physiological processes that shape perception and understanding of the environment (Dolan, 2002; Hajcak, Weinberg, MacNamara, & Foti, 2012; Lang, 1984). As electroencephalography (EEG) provides excellent temporal resolution in the milliseconds range, it is an excellent tool to probe the time course of neural responses to emotional stimuli. An improved understanding of emotion processing is essential, as this may provide insight into deficits that characterize psychiatric disorders.

Recent research exploring electrophysiological correlates of emotion processing has focused on the late positive potential (LPP). The LPP is a slow-wave event-related potential (ERP) sensitive to emotional arousal that reflects elaborated attention toward affective stimuli (Auerbach, Stanton, Proudfit, & Pizzagalli, 2015; Auerbach et al., 2016; Hajcak, Weinberg, MacNamara, & Foti, 2012). The LPP is larger following unpleasant and pleasant stimuli compared to neutral stimuli (Cuthbert, Schupp, Bradley, Birbaumer, & Lang, 2000; Schupp et al., 2000 Foti & Hajcak, 2008; Foti, Hajcak, & Dien, 2009). Generally, the LPP emerges as early as 300 milliseconds (ms) poststimulus (Cuthbert et al., 2000) and spans several hundred ms to seconds (Foti & Hajcak, 2008). The LPP is initially maximal over parietal sites (Schupp et al., 2000), and later in its time course, often propagates to frontocentral regions (Auerbach et al., 2015; Foti & Hajcak, 2008). The LPP also appears to be a variant of the P300, a component that is maximal in parietal regions and emerges between 300–500 ms poststimulus (Olofsson, Nordin, Sequeria, & Polich, 2008; Sutton, Braren, Zubin, & John, 1965). The P300, or P3, indexes increased attention toward salient stimuli, and similar to the LPP, prior research investigating the P300 has shown increased amplitudes for emotional relative to neutral stimuli (Hajcak, MacNamara, & Olvet, 2010; Polich & Kok, 1995). Taken together, whereas the P300 reflects processes underlying preferential attention to target stimuli, the longer time course of the LPP indexes processes related to sustained attention and encoding of emotional information (Dolcos & Cabeza, 2002).

Evidence from studies using emotional images shows greater LPP amplitude during passive viewing of unpleasant and pleasant images compared to neutral images (Hajcak & Olvet, 2008; Foti et al., 2009; Weinberg & Hajcak, 2010). Although some studies have shown a larger LPP following unpleasant relative to pleasant images (Hajcak & Olvet, 2008; Kujawa, Klein, & Hajcak, 2013), this may reflect differences in the arousal ratings of the images (see Weinberg & Hajcak, 2010). Collectively, these findings suggest that the LPP reflects increased attention toward emotional stimuli (e.g., words, images), and in some instances, is modulated by valence (Auerbach et al., 2015; Auerbach et al., 2016; Speed, Nelson, Auerbach, Klein, & Hajcak, 2016).

To improve our understanding of pathophysiological processes underlying emotion processing, research has probed the LPP using the Emotional Interrupt Task (EIT; Mitchell et al., 2006). During the EIT, participants identify a target stimulus that is preceded and followed by task-irrelevant neutral, unpleasant, and pleasant images selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 2008). Using the EIT, we can examine: (a) behavioral measures of interference and task engagement and (b) LPP as a function of stimulus valence. In an undergraduate sample, Weinberg and Hajcak (2011a) found a larger LPP following unpleasant and pleasant images compared to neutral images; however, no differences emerged in activity elicited by pleasant and unpleasant images. Interestingly, the LPP following emotional images was associated with slower reaction times when identifying target stimuli. Similarly, among 8- to 13-year-old children, increased LPP following pleasant and unpleasant images was related to faster reaction times to targets (Kujawa et al., 2012). In a study of at-risk youth (i.e., parental history of depression), Nelson and colleagues (2015) showed that parental depression history was associated with attenuated LPP to neutral and emotional stimuli. Further, among healthy youth, Speed and colleagues (2015) demonstrated that higher extraversion was associated with increased LPP to both pleasant and unpleasant images. Together, these findings suggest that emotional stimuli result in increased LPP activity, which, at times, may interfere with task performance.

In line with the Precision Medicine Initiative (Insel, Amara, & Baschke, 2015), identifying biological indicators that predict treatment response is critical. Prior to testing predictors, research must first examine core psychometric properties, including test-retest stability (i.e., invariance over time) and internal consistency (i.e., odd/even reliability) (see Auerbach et al., 2016; Cassidy, Robertson, & O’Connell, 2012; Hess et al., 2017; Olvet & Hajcak, 2009; Tenke et al., 2017; Weinberg & Hajcak, 2011b). In research testing the EIT, Kujawa and colleagues (2013) showed 2-year stability of LPP amplitude in children 8 to 13 years old (Kujawa et al., 2013). At both the baseline and follow-up assessments, there was a greater LPP following pleasant and unpleasant images compared to neutral images, and unpleasant images elicited a greater LPP relative to pleasant images. Age-related differences also emerged, as the LPP was maximal at occipital sites at the first assessment, when participants were younger, whereas the effects were maximal in parietal electrodes two years later.

Together, these findings provide initial evidence for stability of the LPP in a limited range of children and early adolescents. Further research, however, is needed to explore psychometric properties across broader developmental periods. To build on prior research, the current study examined the stability and reliability of behavioral indices and the LPP. Healthy, female youth aged 13 to 22 years completed a baseline and 1-month follow-up assessment. The following a priori hypotheses were tested. First, consistent with prior EIT research (Kujawa et al., 2013; Weinberg & Hajcak, 2011a), we expected that healthy youth would: (a) show greater accuracy and faster reaction times for neutral relative to pleasant and unpleasant images and (b) exhibit greater LPP amplitudes to pleasant and unpleasant compared to neutral images. Second, we hypothesized that behavioral and ERP effects would demonstrate stability (i.e., strong test-retest correlations) at the one-month follow-up assessment. Last, we expected age-related differences in LPP activity. Given prior work demonstrating greater LPP in younger compared to older youth (MacNamara et al., 2016), we expected that younger participants would demonstrate enhanced LPPs in parietal regions compared to older participants.

Method

Procedure

The Institutional Review Board provided approval for the study. Assent was obtained from youth aged 13 to 17 years, and participants 18 years and older and legal guardians provided written consent. Participants were recruited from the greater Boston area through flyers, online advertisements, and direct mailing. Eligibility criteria included English fluency, right-handedness, and female sex. Exclusion criteria were any history of psychiatric illness, psychotropic medication use, organic brain syndrome, neurologic disorders, or seizures. At baseline, participants were administered a clinical interview assessing lifetime mental illness and a depressive symptom self-report measure. Within one to two weeks, participants completed the EIT while EEG data were recorded. The mean length of time between the clinical and EEG assessment was 5.32 ± 5.11 days. For the one-month follow-up assessment, participants returned to the lab and were re-administered the self-report measure and EIT (while EEG data were recorded). The length of time between the clinical and EEG follow-up assessment was brief, 0.54 ± 1.57 days. Participants were remunerated $100.

Participants

The sample included healthy, female youth aged 13 to 22 years with no lifetime psychopathology. Only female participants were included to reduce heterogeneity. Thirty-three participants were enrolled in the study; however, five youth were excluded from analyses given poor EEG data quality (n = 1) and lack of follow-up EEG data (n = 4). Excluded participants (n = 5) and the final sample (n = 28) did not differ in age, t(31) = 0.91, p = 0.52, d = 0.38, race, χ2(4) = 7.54, p = 0.11, φ = 0.48, or family income, χ2(4) = 4.20, p = 0.38, φ = 0.37. The final sample (Mage = 17.61, SDage = 2.95) reported the following racial distribution: 21.4% Asian, 3.6% Black or African American, 64.3% White, and 10.7% more than one race. The family income distribution included: 14.3% less than $10,000, 7.1% $25,000 to $50,000, 14.3% $50,000 to $75,000, 3.6% $75,000 to $100,000, 50% more than $100,000, and 10.7% not reported.

Instruments

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Child and Adolescents (MINI-KID)

Participants were administered the MINI-KID (Sheehan et al., 2010), a structured diagnostic interview used to assess Axis I psychopathology in children and adolescents. The MINI-KID has shown good reliability and validity (Sheehan et al., 2010). Post-baccalaureate research assistants, graduate students, and postdoctoral fellows administered the interviews after receiving approximately 50 hours of training, which included didactics, listening to past interviews, role play, mock interviews, and direct supervision.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)

The BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a 21-item self-report questionnaire assessing depressive symptom severity over the past two weeks. Items range from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater depression severity. The Cronbach’s alpha for the BDI-II in the current study was 0.74 at the baseline assessment and 0.88 at the follow-up assessment, suggesting good internal consistency.

Experimental Task

The Emotional Interrupt Task (EIT; Mitchell et al., 2006) included 60 images selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang et al., 2008): 20 neutral, 20 unpleasant, and 20 pleasant1. According to IAPS normative adult ratings (9-point rating scale; Lang et al., 2008), pleasant images used were rated as more positive in valence (M = 7.51, SD = 0.51) than neutral images (M = 5.27, SD = 0.35), which were rated as more positive than unpleasant images (M = 3.09, SD = 0.76). Additionally, both pleasant (M = 5.03, SD = 0.77) and unpleasant images (M = 6.12, SD = 0.57) were rated as more arousing than neutral images (M = 2.99, SD = 0.68), though unpleasant images were rated as more arousing than pleasant images. Images were presented twice over three blocks for a total of 120 trials. Each trial began with a fixation cross presented for 800 ms. Then, an image was displayed for 1000 ms, followed by a target (< or >) that was presented for 150 ms. Finally, the same image appeared on screen for an additional 400 ms. Participants indicated whether the target arrow was pointing to the right or left by pressing the corresponding button on a response box. The inter-trial interval was jittered between 1500 and 2000 ms.

EIT behavioral outcomes included reaction time (RT) indexes for correct trials and overall accuracy for each stimulus type (pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral). Previous research indicates that RT distributions are not Gaussian (normal) distributions; instead, ex-Gaussian distributions—a combination of Gaussian and exponential distributions that rises rapidly on the left side of the distribution and has a long tail to the right—fit RT distributions optimally (e.g., Balota & Spieler, 1999). The main drawback of a central tendency approach (i.e., computing mean reaction time assuming a normal distribution), especially when untransformed RT data are analyzed, is reduced power. Further, although using cutoffs (e.g., removing RTs longer than a certain absolute value; Mitchell et al., 2006) may improve power in some cases, when the true effect is actually in the long tail of the distribution, cutoff methods produce Type II errors (see Whelan, 2008, for a discussion).

Consequently, prior to analyzing the RT data, we fit an ex-Gaussian distribution to each participant’s data using the R package “retimes” (Massidda, 2013). These distributions have three parameters: the mean (mu) and standard deviation (sigma) of the Gaussian portion of the distribution, and the mean of the exponential portion of the distribution (tau). Briefly, these 3 parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood (ML) and implementing the Simplex method to establish the minimum of the objective function. We used a bootstrapping approach (5000 samples with replacement) given our sample was relatively small. First, mu and sigma were obtained with a Gaussian kernel estimator (see Van Zandt, 2000), then tau was chosen within the bootstrapped values based on ML criterion.

Classically, mu and tau were proposed to reflect distinct processes where the former is influenced by individual differences in perception and response execution, whereas the latter is more likely to reflect central decision-making processes (Hohle, 1965). Critically, individual differences in attention selection tasks involving choices based on earlier level visual codes (e.g., direction of target) like the EIT typically involve shifts in the entire distribution and may primarily affect mu (e.g., Spieler, Balota, & Faust, 1996). Among other factors, tau is influenced by lapses of attention that produce more frequent longer RT trials, thus creating changes in the left tail of the ex-Gaussian distribution (e.g., Hervey et al., 2006). Given evidence that ex-Gaussian parameters capture separable attentional and cognitive processes, we analyzed mu and tau independently in primary RT analyses.2

To analyze accuracy for each stimulus type (pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral), we first computed a count of errors made in each condition. To test the effects of stimulus type and time on number of errors, we fit a within-subjects Poisson regression model using Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE). In the model, we used an auto-regression correlation structure (AR1) and robust standard errors to control for overdispersion in our data, which is in line with current recommendations (e.g., Cameron & Trivedi, 2009). For all correlational analyses involving accuracy (e.g., test-retest estimates), we fit Poisson regression models with robust standard errors and report betas and standard errors to capture associations.3

EEG Recording, Data Reduction, and Analysis

The EEG was recorded using a 128-channel HydroCel GSN Electrical Geodesics, Inc. (Eugene, OR) net. Continuous EEG data, referenced to Cz, were sampled at 250 Hz. Electrode impedances were kept below 65 kΩ and offline analyses were performed using BrainVision Analyzer 2.1 software (Brain Products, Germany). EEG data were re-referenced to the average reference, and low- and high-pass filters were applied: 0.1 and 30 Hz. An independent component analysis (ICA) transform was implemented to identify and remove eye movement artifacts and eye blinks using the following criteria: whole data, Classic PCA sphering, Infomax ICA, Energy ordering, and 512 convergence steps. For each trial, EEG data were segmented 200 ms before the initial image onset and continued for 1200 ms. A semiautomated procedure to reject intervals for individual channels used the following criteria: (1) a voltage step > 50 µV between sample rates, (2) a voltage difference > 300 µV within a trial, and (3) a maximum voltage difference of < 0.50 µV within a 100-ms interval. All trials were also visually inspected and further artifacts were rejected manually. After completing the data reduction steps, we then examined the average number of trials retained per condition (i.e., 40 trials/condition) across assessments: (a) neutral trials: 35.55 ± 4.07, (b) unpleasant trials: 35.96 ± 3.91, (c) pleasant trials: 35.75 ± 4.23.

ERPs were computed time-locked to pre-target neutral, unpleasant, and pleasant images, and the average amplitude 200 ms before the pre-target stimulus onset was used as the baseline. Only trials with a correct response between 150–1500 ms after target onset were included in ERP averages. The LPP component was calculated as the mean activity at electrode site Pz where the component was maximal across participants for the 400–1000 ms poststimulus time window4. Difference waves also were computed to examine discrepancies between activity during emotional and neutral conditions (difference waves: unpleasant minus neutral versus pleasant minus neutral). In addition to probing subtraction-based difference scores, we computed standardized residuals (i.e., regressed neutral on unpleasant and pleasant images) to extract the unique variance in the emotional images after accounting for the neutral images, an alternative to computing difference scores (see Levinson, Speed, Infantolino, & Hajcak, 2017; Meyer, Lerner, De Los Reyes, Laird, & Hajcak, 2017). All analyses were conducted with SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). A repeated measures analysis of variance (RMANOVA) tested main effects of Time (Baseline, Follow-Up) and Condition (Neutral, Unpleasant, Pleasant) as well as a Time x Condition interaction using a Greenhouse-Geisser correction. We expected a significant main effect of Condition. To demonstrate stability of a given effect over time, we anticipated that the main effect of Time and the Time x Condition interaction would be non-significant. To test whether age moderated LPP stability, we conducted an Age (continuous measure) x Time x Condition RMANOVA, and additionally, to determine whether young participants show greater activity in occipital versus parietal regions (e.g., Hajcak & Dennis, 2009; Kujawa et al., 2013), we conducted Age (continuous measure) x Condition x Electrode (Pz, Oz) RMANOVAs at each time point.

We computed effect sizes (ηp2) for all analyses, where: 0.02–0.12 = small, 0.13–0.25 = medium, and ≥ 0.26 = large. Test-retest stability for behavioral and ERP measures was assessed using Pearson product-moment correlations with the following criteria: 0.10- 0.29 = small, 0.30–0.49 = moderate, ≥ 0.50 = large (Cohen, 1988). The internal consistency of behavioral measures and the LPP were evaluated through testing the correlation of the odd and even trials. The Spearman-Brown Prophecy Formula (Nunnally, Bernstein, & Berge, 1967) was used to correct these correlations because the total number of items included in the averages is split in half (reliability = 2 * rodd/even / 1 + rodd/even). Spearman-Brown coefficients were evaluated where: > 0.80 = good/excellent, 0.70 – 0.79 = acceptable, and < 0.60 = poor.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Depressive symptoms were assessed at the baseline and follow-up assessment (test-retest r = 0.82, p < 0.001) to ensure the non-clinical status across assessments. As expected, depressive symptom scores were low (Baseline: 0.86 ± 1.99; Follow-Up: 1.21 ± 2.87) and did not differ over time, t(27) = −1.12, p = 0.27, d = −0.24.

Behavioral Data

Behavioral data from the EIT are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Behavioral Data from the Emotional Interrupt Task

| Baseline (n = 28) | Follow-Up (n = 28) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Accuracy | ||||

| Pleasant | 0.96 | 0.06 | 0.96 | 0.04 |

| Unpleasant | 0.96 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.03 |

| Neutral | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.03 |

| Reaction Time – mu (ms) | ||||

| Pleasant | 390.50 | 128.93 | 395.69 | 166.25 |

| Unpleasant | 383.09 | 136.41 | 397.02 | 171.85 |

| Neutral | 362.84 | 133.36 | 388.26 | 174.03 |

| Reaction Time – tau (ms) | ||||

| Pleasant | 44.21 | 23.42 | 60.31 | 43.38 |

| Unpleasant | 53.77 | 28.10 | 60.94 | 43.33 |

| Neutral | 65.55 | 43.90 | 61.64 | 38.72 |

Note. Reaction time measures are given for correct trials only.

Number of Errors

In our omnibus GEE analysis, the effect of Condition was not significant for number of errors, b = −0.02, SE = 0.44, χ2(1, N = 168) = 0.003, p = 0.96, OR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.41, 2.32], which may reflect high rates of accuracy across conditions. Additionally, neither the main effect of Time, b = −0.18, SE = 0.53, χ2(1, N = 168) = 0.12, p = 0.73, OR = 0.83, 95% CI [0.30, 2.33], nor the Time x Condition interaction, b = 0.05, SE = 0.25, χ2(1, N = 168) = 0.05, p = 0.83, OR = 1.05, 95% CI [0.65, 1.72], was significant. Test-retest analyses using a series of Poisson regression models revealed an association over time for neutral images, b = 0.14, SE = 0.05, χ2(1, N = 28) = 6.71, p = 0.01, OR = 1.15, 95% CI [1.03, 1.27], but not for pleasant, b = 0.03, SE = 0.08, χ2(1, N = 28) = 0.18, p = 0.68, OR = 1.03, 95% CI [0.89, 1.20], or unpleasant, b = 0.07, SE = 0.10, χ2(1, N = 28) = 0.56, p = 0.45, OR = 1.08, 95% CI [0.89, 1.30], images. There also was strong internal consistency in accuracy at the baseline (Spearman-Brown odd/even corrected reliability = 0.85) and follow-up (Spearman-Brown odd/even corrected reliability = 0.78) assessments.

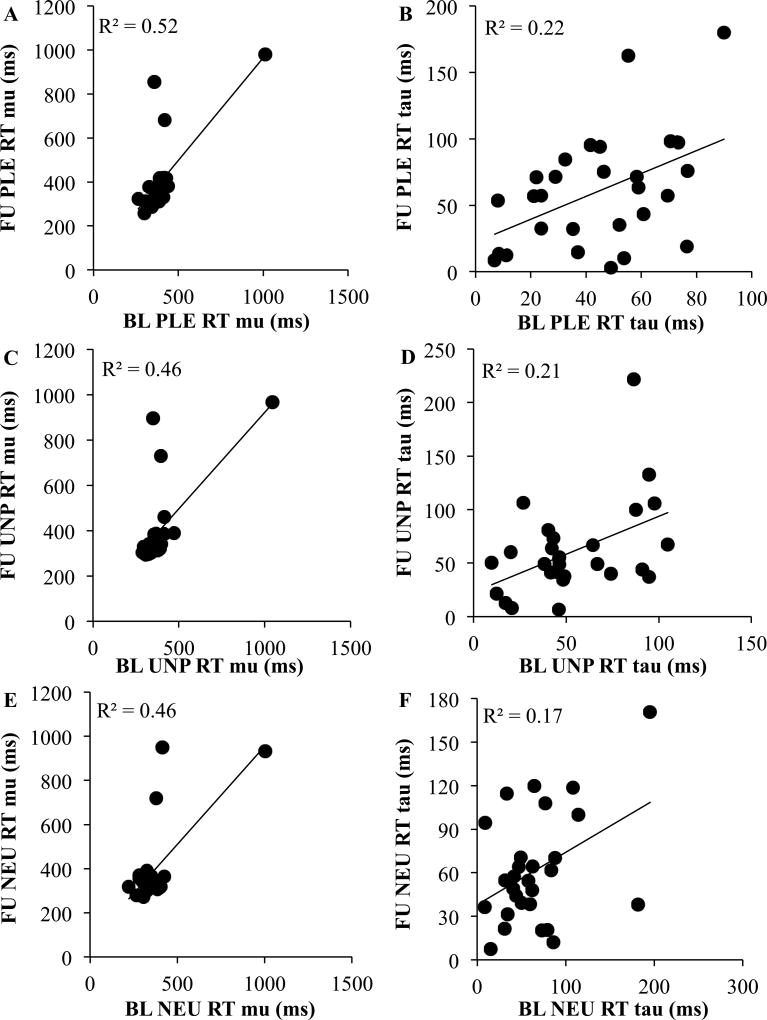

Reaction Time—Mu

In the RMANOVA model for mu, we found a main effect of Condition, F(2, 54) = 7.21, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.21, and unexpectedly, this main effect was qualified by a significant Time x Condition interaction, F(2, 54) = 3.56, p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.12. As hypothesized, the main effect of Time was non-significant, F(1, 27) = 0.42, p = 0.52, ηp2 = 0.02. To decompose the interaction, we conducted follow-up simple effects analyses. In the baseline simple effects model, the effect of Condition was significant, F(2, 54) = 10.22, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.27, such that participants had slower RTs for both pleasant (M = 362.84, SE = 24.37) and unpleasant (M = 383.09, SE = 25.78) stimuli compared to neutral (M = 362.84, SE = 25.20) stimuli, ps < 0.02, ds > 0.49. In contrast, RTs for pleasant and unpleasant trials did not significantly differ, p = 0.11, d = 0.33. However, in the simple effects model for the follow-up assessment, the effect of Condition was non-significant, F(2, 54) = 1.19, p = 0.31, ηp2 = 0.04. Further, for mu, there were significant associations over time for pleasant (r = 0.76, p < 0.001), unpleasant (r = 0.72, p < 0.001), and neutral (r = 0.68, p < 0.001) images (see Figures 1A, 1C, 1E)5. When examining raw mean reaction time, the Spearman-Brown corrected odd/even reliability was 0.99 at both the baseline and follow-up assessments, suggesting excellent internal consistency.

Figure 1.

Test-Retest for Reaction Time Measures at the Baseline and Follow-Up Assessments

Note. BL = Baseline; FU = Follow-Up; PLE = Pleasant Images; UNP = Unpleasant Images; NEU = Neutral Images. Correlations depicted include all participants.5

Reaction Time—Tau

In the RMANOVA model for tau, the main effects of Condition, F(2, 54) = 2.00, p = 0.14, ηp2 = 0.07, and Time, F(1, 27) = 1.28, p = 0.27, ηp2 = 0.05, were non-significant, as well as the Time x Condition interaction, F(2, 54) = 2.42, p = 0.10, ηp2 = 0.08. However, for tau, there were significant associations over time for pleasant (r = 0.46, p = 0.01), unpleasant (r = 0.46, p = 0.01), and neutral (r = 0.41, p = 0.03) images (see Figures 1B, 1D, 1F).

Event-Related Potentials

Late Positive Potential

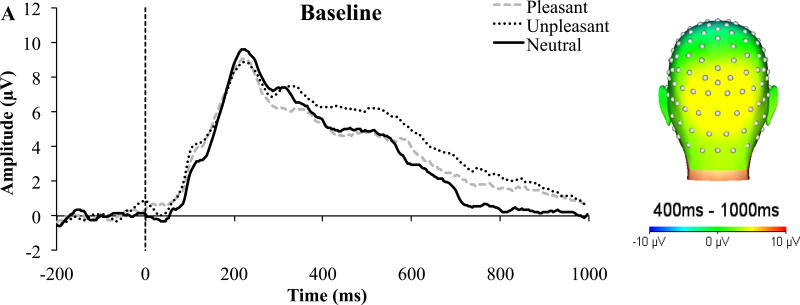

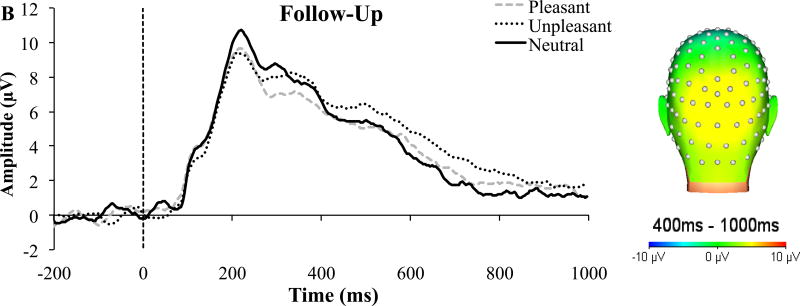

In line with our hypothesis, there was a main effect of Condition, F(2, 54) = 8.78, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.25. Participants had greater sustained positivity to unpleasant and pleasant images compared to neutral images at both time points (Figure 2). As hypothesized, the Time, F(1, 27) = 2.09, p = 0.16, ηp2 = 0.07, and Time x Condition, F(2, 54) = 0.39, p = 0.64, ηp2 = 0.01, effects were non-significant. Additionally, there were significant test-retest associations for neutral (r = 0.54, p = 0.003), unpleasant (r = 0.87, p < 0.001), pleasant (r = 0.73, p < 0.001; Figure 3) images. To demonstrate the internal reliability of the LPP, odd/even trial correlations were evaluated. Spearman-Brown corrected odd/even reliability suggest excellent internal consistency at each assessment (baseline: 0.93; follow-up: 0.92). Internal consistency also was examined as a function of image valence: baseline (neutral: 0.84; unpleasant: 0.89; pleasant: 0.79) and follow-up (neutral: 0.90; unpleasant: 0.82; pleasant: 0.57).

Figure 2.

LPP Activity During the Emotional Interrupt Task

Note. LPP activity at Pz in response to pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral images during the (A) baseline and (B) follow-up assessment. Scalp topographies reflect mean activation across conditions (pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral images) at each assessment between 400–1000 ms poststimulus.

Figure 3.

Test-Retest for LPP during Baseline and Follow-Up Assessments

Note. BL = Baseline; FU = Follow-Up; PLE = Pleasant; UNP = Unpleasant; NEU = Neutral

Difference Waves

The Time x Condition RMANOVA using difference wave scores (unpleasant-neutral and pleasant-neutral) revealed a significant main effect of Condition, F(1, 27) = 6.70, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.20. The unpleasant-neutral difference wave had greater sustained positivity compared to the pleasant-neutral difference. Neither the main effect of Time, F(1, 27) = 0.49, p = 0.49, ηp2 = 0.02, nor the Time x Condition interaction, F(1, 27) = 0.13, p = 0.72, ηp2 = 0.01, was significant. The test-retest correlational analyses did not show significant associations over time for difference scores (ps > 0.35). The internal consistency of the pleasant-neural difference score at baseline was modest (Spearman-Brown corrected odd/even reliability = 0.63), but the unpleasant-neutral difference score was poor (Spearman-Brown corrected odd/even reliability = 0.35). For the follow-up assessment, the internal reliability of the differences scores also was poor (Spearman-Brown corrected odd/even reliability ≤ 0.47).

We also examined difference scores using a residual-based method. Similar to the subtraction-based difference scores, test-retest stability analyses of residual-based scores also were not significant (ps > 0.36). Additionally, at baseline the internal reliability of the unpleasant residuals (Spearman-Brown corrected odd/even reliability = 0.65) and pleasant residuals (Spearman-Brown corrected reliability = 0.64) were modest. The internal consistency was poor at the follow-up assessments (Spearman-Brown corrected reliability ≤ 0.52).

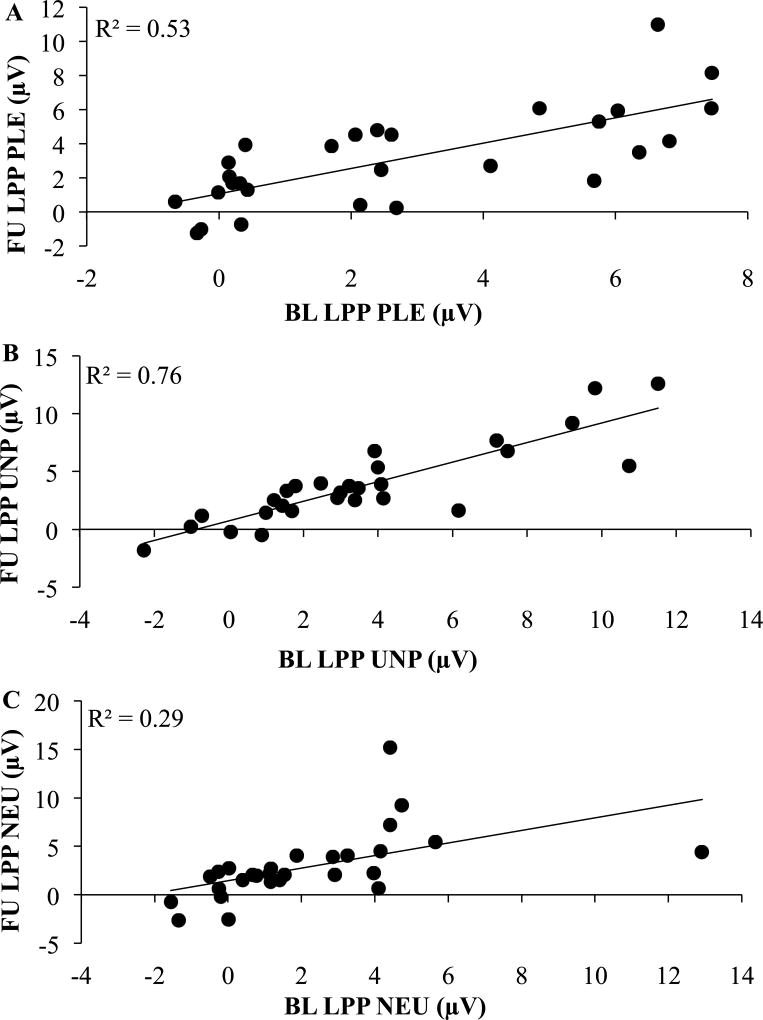

Age-Related Differences

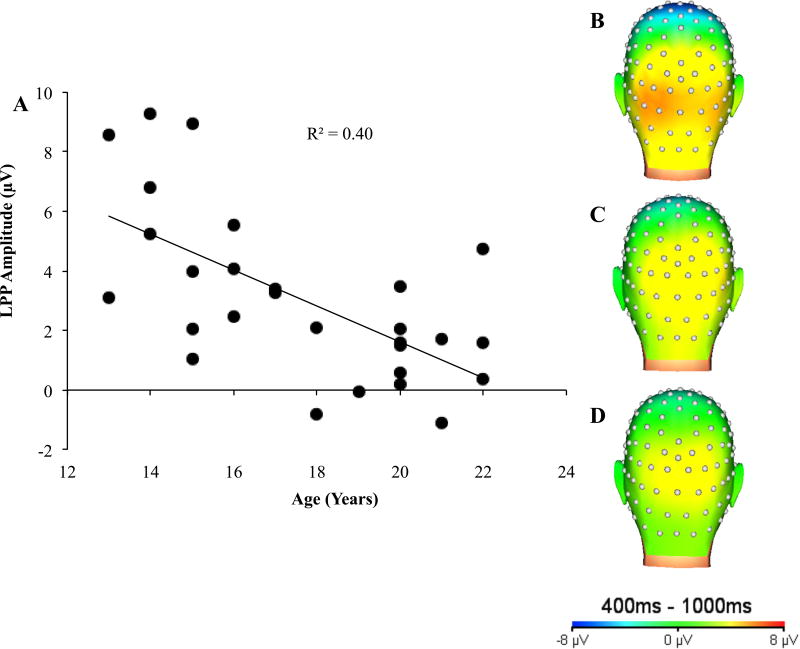

To test whether participant age in years (continuous measure) moderated LPP stability, we conducted an Age x Time x Condition RMANOVA. The Age x Time x Condition interaction was non-significant, F(2, 52) = 0.35, p = 0.67, ηp2 = 0.01, indicating that the LPP over time did not vary as a function of participant age. Additionally, all lower-order 2-way interactions were non-significant (ps > 0.20, ηp2 < 0.06), and the main effects (Time, Condition) as reported above did not change when age was included in the model. Interestingly, a significant main effect of Age emerged, F(1,26) = 17.39, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.40, such that younger participants showed greater positivity compared to older participants. A Pearson’s product-moment correlation indicated that age was inversely correlated with the LPP amplitude across conditions and assessments (r = −0.63, p < 0.001, Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Relationship between LPP and Age

Note. (A) Average LPP amplitude across image valence (unpleasant, pleasant, and neutral) and time (Baseline, Follow-Up); Topographic map of average LPP across image conditions and time for (B) 13–15 year olds (n = 9), (C) 16–18 year olds (n = 7), and (D) 19–22 year olds (n = 12).

As prior work has shown that the LPP tends to be maximal in occipital regions in younger individuals (Hajcak & Dennis, 2009; Kujawa et al., 2013), we conducted additional analyses testing differential activity in parietal and occipital regions. Specifically, Age x Condition x Electrode (Pz, Oz) RMANOVAs were conducted for Time 1 and Time 2. At each time point, the main effects of Condition and Electrode as well as all interactions were not significant (ps > 0.10, ηp2 < 0.10). These null effects also reflect the similar topographical map activity for younger versus older participants (see Figure 4B–D).

Correlational Analyses

Correlational analyses for baseline and follow-up EIT reaction time and ERP indices were conducted (see Table 2). Accuracy measures were not included in these correlation tables because the variables were not linear. At both time points, mu was significantly associated across each condition. Associations among LPP amplitudes were significant across conditions at the baseline and follow-up assessment. There were no significant correlations between reaction time measures and LPP.

Table 2.

Pearson Product-Moment Correlations among Reaction Time Measures and Event-Related Potentials at the Baseline and Follow-Up Assessment

| Baseline | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PLE RT mu | - | ||||||||

| 2. UNP RT mu | 0.99** | - | |||||||

| 3. NEU RT mu | 0.97** | 0.95** | - | ||||||

| 4. PLE RT tau | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.33 | - | |||||

| 5. UNP RT tau | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.49** | - | ||||

| 6. NEU RT tau | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.45* | 0.21 | - | |||

| 7. PLE LPP | −0.09 | −0.10 | −0.07 | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.03 | - | ||

| 8. UNP LPP | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.82** | - | |

| 9. NEU LPP | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.10 | 0.004 | 0.11 | 0.70** | 0.74** | - |

|

| |||||||||

| Follow-Up | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. |

|

| |||||||||

| 1. PLE RT mu | - | ||||||||

| 2. UNP RT mu | 0.98** | - | |||||||

| 3. NEU RT mu | 0.98** | 0.99** | - | ||||||

| 4. PLE RT tau | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.25 | - | |||||

| 5. UNP RT tau | 0.48** | 0.49** | 0.54** | 0.57** | - | ||||

| 6. NEU RT tau | 0.34 | 0.38* | 0.28 | 0.65** | 0.52** | - | |||

| 7. PLE LPP | −0.23 | −0.20 | −0.25 | 0.16 | −0.23 | 0.16 | - | ||

| 8. UNP LPP | −0.09 | −0.09 | −0.14 | −0.09 | −0.29 | 0.09 | 0.82** | - | |

| 9. NEU LPP | −0.27 | −0.26 | −0.27 | 0.03 | −0.29 | 0.01 | 0.76** | 0.70** | - |

Note.

p<0.01;

p<0.05;

PLE = Pleasant Images; UNP = Unpleasant Images; NEU = Neutral Images; RT = Reaction Time; LPP = Late Positive Potential

Discussion

To improve our understanding of emotion processing, the present study tested the one-month stability of the EIT among healthy, female youth. Four principal findings emerged. First, there is evidence of an interference effect at baseline (but not at the follow-up assessment), as participants showed a slower reaction time for unpleasant and pleasant images relative to neutral images. Additionally, test-retest of behavioral measures was relatively stable over time. Second, there was greater LPP for unpleasant and pleasant images relative to neutral images, and the test-retest stability was excellent. Third, behavioral measures and LPP demonstrated strong internal consistency (odd/even reliability) across conditions; however, the internal consistency of the difference waves ranged from modest to poor. Last, younger participants exhibited greater LPP amplitudes compared to older participants across conditions. As a whole, these results support the growing literature assessing stability of the LPP over time during emotion processing.

We found no significant effects of task-irrelevant emotional images on accuracy in the current sample. These findings may be due in part to a ceiling effect, as participants performed well across conditions (average accuracy rates >95%). The lack of accuracy findings may reflect sex-related decreased variability on task performance, though previous studies of female-only early adolescent samples have demonstrated variability in behavioral outcomes (Nelson et al., 2015; Speed et al., 2015). Reaction time was assessed using an ex-Gaussian approach (Spieler, Balota, & Faust, 1996). Mu, which is thought to reflect perception and response execution (Hohle, 1965), was slower for pleasant and unpleasant trials compared to neutral trials at baseline and is consistent with prior research demonstrating slower reaction times for emotional versus neutral images (Mitchell et al., 2006; Weinberg & Hajcak, 2011a). At the same time, this difference was not significant at the follow-up assessment. This null effect may reflect our study design, as (a) test-retest was conducted during a 1-month time span and (b) the second assessment included the third and fourth viewing of the same images (during a relatively brief time window). Unfortunately, this may have unduly influenced the likelihood of instigating an interference effect at the behavioral level; yet, as our findings show, electrocortical differences persisted. Finally, task-irrelevant images did not significantly impact tau, which may not be surprising as tau indexes lapses in attention (e.g., Hervey et al., 2006). Overall, the ex-Gaussian approach to model reaction time demonstrated a preliminary interference effect, and more broadly, the EIT showed promising psychometric properties.

Consistent with prior work (Weinberg & Hajcak, 2011a; Kujawa et al., 2012), participants exhibited greater positivity to unpleasant and pleasant images compared to neutral images across assessments. Further, the unpleasant-neutral difference score was potentiated relative to pleasant-neutral images. This suggests that unpleasant images elicited greater positivity than pleasant images when compared to neutral images, which may be a result of unpleasant images being significantly more arousing than pleasant images. The LPP was remarkably stable across conditions with large effect sizes, which is in line with previous work demonstrating strong test-retest stability of the LPP (Auerbach et al., 2016; Kujawa et al., 2013). Similar stability estimates have been shown for the P1, a component indexing semantic monitoring of emotional information, during a self-referential encoding task (Auerbach et al., 2016). By contrast, alternative approaches to probe emotion processing using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) may be less stable. For example, in a sample of healthy adolescents viewing fearful, happy, and neutral faces, activation in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, two regions implicated in emotion face processing, demonstrated poor-to-modest stability (van den Bulk et al., 2013). Taken together, ERPs may be a more stable and reliable tool to detect pathophysiological mechanisms associated with emotion processing.

Test-retest reliability and internal consistency of the ERPs was assessed using three different approaches. When probing odd/even correlations and internal consistency for each valence separately, results were in the excellent range. However, for difference scores and standardized residuals, neither approach showed significant test-retest reliability. This is consistent with prior research (Kujawa et al., 2013; Levinson et al., 2017), and it is not necessarily surprising as test-retest reliability of the difference and residualized scores is often lower than the reliability of the constituent components (e.g., unpleasant, pleasant, neutral) (e.g., Meyer et al., 2017; but also see Edwards, 2001). Similarly, the internal consistency using difference scores and residualized approaches were not as strong relative to testing each valence separately. These null effects raise important questions, as ERPs tested by using change or residualized scores often rely on neutral stimuli to help interpret the amplitudes of affective stimuli (e.g., unpleasant, pleasant images). Despite this potential reliability problem, these findings (and other similar results) do not necessarily suggest that researchers should avoid difference or residualized scores. Rather, it is important to determine “why” the reliability may be suboptimal and if this may impact reproducibility. With regards to our study, the LPP amplitudes are positively correlated, which may, in part, account for the poor reliability (Edwards, 2001). In other research there may be very clear mandates as to why it would be important to use data reduction techniques. Thus, rather than having a blanket “should” or “should not” statement about the use of difference or residualized scores, we believe it is more important to: (a) be mindful of the EEG/ERP psychometric properties (and account for potential reliability issues), (b) tailor the data analytic approach to the central research question, and (c) determine whether findings can be replicated (even in the absence of strong test-retest reliability of difference or residualized scores).

The study also sought to address important developmental issues, particularly as it related to determining whether age impacts LPP activity. Results indicated that younger age was associated with greater LPP activity in parietal regions across conditions. These findings support prior work testing age-related electrocortical effects following emotion-based images. Specifically, MacNamara and colleagues (2016) tested age effects on the LPP during the presentation of emotional faces among youth aged 7 to 19 years. Relative to younger children, older participants showed decreased positivity following emotional but not neutral stimuli (geometric shapes). Age-related decreases in the LPP also have been demonstrated in other tasks; when asked to attend to either pain or non-pain cues in images, adolescents exhibited a potentiated LPP compared to young adults (Mella et al., 2012). Additionally, age-related differences in the LPP scalp distribution also were explored, and results indicated that LPP activity did not vary as a function of electrode site (parietal versus occipital) for younger versus older youth (see Figure 4B–D). At the same time, this conflicts with prior work in younger individuals that has often shown the LPP is maximal in occipital regions (e.g., Hajcak & Dennis, 2009; Kujawa et al., 2013). Together, these findings underscore the importance of testing whether age influences LPP activity across development, as this may have important implications for interpreting ERP effects.

Our results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, prior research using IAPS stimuli has demonstrated greater electrophysiological reactivity in females relative to males during passive viewing of unpleasant stimuli (Lithani et al., 2010), which underscores the importance of testing sex-specific effects. However, as the current study only included female participants, we cannot determine whether our effects generalize to males. Second, prior research has demonstrated that pubertal status influences electrophysiological responses in youth (e.g., processing of emotional faces, fear-potentiated startle) (Ferri, Bress, Eaton, & Proudfit, 2014; Schmitz, Grillon, Avenevoli, Cui, & Merikangas, 2014). At the same time, the present study did not assess pubertal status, and thus, we cannot determine how pubertal status affects LPP stability. Third, this study examined the stability of ERPs over a 1-month period, and consequently, it is important to confirm these effects over a longer period of time. Fourth, IAPs images were used to standardize the emotional stimuli across participants. However, the current study did not obtain subjective arousal ratings for each image, which may have facilitated an enhanced interpretation of our ERP effects. Additionally, images were presented twice during each administration of the EIT. Notably, we used the same paradigm as other published studies (e.g., Kujawa et al., 2012; Kujawa et al., 2013; Nelson et al., 2015; Speed et al., 2015; Weinberg & Hajcak, 2011a), which then allowed us to compare our behavioral and ERP effects to the extant literature. At the same time, reviewing images multiple times during the trial may have an unmeasured impact on core psychometric properties. Last, a number of factors, including menstrual cycle and circadian rhythm may influence ERP amplitude (Polich & Kok, 1995), and thus, future research should account for these potential effects.

In summary, prior research has shown that the LPP is a stable and reliable marker of processing emotional words (Auerbach et al., 2016) and images (Kujawa et al., 2013). Towards the goal of identifying indicators of emotion processing, the current findings provide further support for the stability and reliability of the LPP over time in healthy youth. Ultimately, an improved understanding of electrophysiological correlates of emotion processing may lead to insight regarding the onset and maintenance of debilitating psychiatric symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Randy P. Auerbach was partially supported through funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) K23MH097786, the Rolfe Fund, and the Tommy Fuss Fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or NIMH.

Footnotes

IAPS Images used. Practice Images: 9421, 7140, 6260, 7460, 2206, 2750, 9584, 7550, 9160, 2384; Pleasant Images: 1463, 1710, 1750, 1811, 2070, 2091, 2092, 2224, 2340, 2345, 2347, 7325, 7330, 7400, 8031, 8200, 8370, 8461, 8496, 8497; Unpleasant Images: 1050, 1052, 1200, 1205, 1300, 1304, 1930, 2458, 2691, 2703, 2800, 2811, 2900, 3022, 6190, 6213, 6231, 6510, 6571, 9600; Neutral Images: 2514, 2580, 5390, 5395, 5500, 5731, 5740, 5900, 7000, 7002, 7009, 7010, 7026, 7038, 7039, 7090, 7100, 7130, 7175, 7190.

Analyses of sigma yielded non-significant results (i.e., no effect of condition, time or their interaction; no evidence of test-retest reliability) and are available from the authors by request.

In preliminary model building, we also fit negative binomial distribution with log link to the number of errors and found these models fit slightly less closely than Poisson models.

Given prior work demonstrating that an occipitally maximal LPP characterizes children and early adolescents (e.g., Kujawa et al., 2013), we explored scalp topography maps comparing younger and older participants. Participants exhibited similar parietal distribution across ages.

Two participants were identified as univariate outliers (i.e., mu values for all 3 conditions were 3 SD above the mean at the follow-up assessment). All reaction time analyses were run with and without these participants. The results from the RMANOVA models did not change appreciably. For test re-test correlations, the correlation between baseline and follow-up mu in the neutral condition was non-significant when the outliers were removed (r = 0.23, p = 0.25). In contrast, the correlations for unpleasant (r = 0.53, p = 0.005), and pleasant (r = 0.44, p = 0.02) stimuli were reduced, but remained statistically significant.

Conflicts of Interest. Dr. Mittal is a consultant for Takeda Pharmaceuticals. No other authors report any conflicts of interest.

References

- Auerbach RP, Stanton CH, Proudfit GH, Pizzagalli DA. Self-referential processing in depressed adolescents: A high-density event-related potential study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2015;124(2):233. doi: 10.1037/abn0000023. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach RP, Bondy E, Stanton CH, Webb CA, Shankman SA, Pizzagalli DA. Self-referential processing in adolescents: Stability of behavioral and ERP markers. Psychophysiology. 2016 doi: 10.1111/psyp.12686. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Balota DA, Spieler DH. Word frequency, repetition, and lexicality effects in word recognition tasks: Beyond measures of central tendency. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1999;128(1):32. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. 2. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics using stata. Vol. 5. College Station, TX: Stata press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy SM, Robertson IH, O’Connell RG. Retest reliability of event-related potentials: Evidence from a variety of paradigms. Psychophysiology. 2012;49(5):659–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01349.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Eribaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, Schupp HT, Bradley MM, Birbaumer N, Lang PJ. Brain potentials in affective picture processing: covariation with autonomic arousal and affective report. Biological Psychology. 2000;52(2):95–111. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(99)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan RJ. Emotion, cognition, and behavior. Science. 2002;298(5596):1191–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1076358. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1076358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcos F, Cabeza R. Event-related potentials of emotional memory: encoding pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral pictures. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2002;2(3):252–263. doi: 10.3758/cabn.2.3.252. https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.2.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JR. Ten difference score myths. Organizational Research Methods. 2001;4(3):265–287. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri J, Bress JN, Eaton NR, Proudfit GH. The impact of puberty and social anxiety on amygdala activation to faces in adolescence. Developmental Neuroscience. 2014;36(3–4):239–249. doi: 10.1159/000363736. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Hajcak G. Deconstructing reappraisal: Descriptions preceding arousing pictures modulate the subsequent neural response. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20(6):977–988. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20066. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2008.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Hajcak G, Dien J. Differentiating neural responses to emotional pictures: evidence from temporal-spatial PCA. Psychophysiology. 2009;46(3):521–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00796.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Dennis TA. Brain potentials during affective picture processing in children. Biological Psychology. 2009;80(3):333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.11.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Olvet DM. The persistence of attention to emotion: brain potentials during and after picture presentation. Emotion. 2008;8(2):250–255. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.250. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, MacNamara A, Olvet DM. Event-related potentials, emotion, and emotion regulation: an integrative review. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2010;35(2):129–155. doi: 10.1080/87565640903526504. https://doi.org/10.1080/87565640903526504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Weinberg A, MacNamara A, Foti D. ERPs and the study of emotion. The Oxford handbook of event-related potential components. 2012:441–474. [Google Scholar]

- Hervey AS, Epstein JN, Curry JF, Tonev S, Eugene Arnold L, Keith Conners C, Hechtman L. Reaction time distribution analysis of neuropsychological performance in an ADHD sample. Child Neuropsychology. 2006;12(2):125–140. doi: 10.1080/09297040500499081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess U, Arslan R, Mauersberger H, Blaison C, Dufner M, Denissen JJ, Ziegler M. Reliability of surface facial electromyography. Psychophysiology. 2017;54(1):12–23. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12676. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohle RH. Inferred components of reaction times as functions of foreperiod duration. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1965;69(4):382. doi: 10.1037/h0021740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel PA, Amara SG, Blaschke TF. Introduction to the Theme “Precision Medicine and Prediction in Pharmacology”. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2015;55:11–14. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-101714-123102. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-101714-123102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Klein DN, Hajcak G. Electrocortical reactivity to emotional images and faces in middle childhood to early adolescence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2012;2(4):458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2012.03.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Klein DN, Proudfit GH. Two-year stability of the late positive potential across middle childhood and adolescence. Biological Psychology. 2013;94(2):290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.07.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ. Cognition in emotion: Concept and action. In: Izard CE, Kagan J, Zajonc RB, editors. Emotions, Cognition, and Behavior. 192–226. CUP Archive; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. Technical Report A-8. University of Florida; Gainesville, FL: 2008. International affective picture system (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson AR, Speed BC, Infantolino ZP, Hajcak G. Reliability of the electrocortical response to gains and losses in the doors task. Psychophysiology. 2017 doi: 10.1111/psyp.12813. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12813. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lithari C, Frantzidis CA, Papadelis C, Vivas AB, Klados MA, Kourtidou-Papadeli C, Bamidis PD. Are females more responsive to emotional stimuli? A neurophysiological study across arousal and valence dimensions. Brain Topography. 2010;23(1):27–40. doi: 10.1007/s10548-009-0130-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-009-0130-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNamara A, Vergés A, Kujawa A, Fitzgerald KD, Monk CS, Phan KL. Age-related changes in emotional face processing across childhood and into young adulthood: Evidence from event-related potentials. Developmental Psychobiology. 2016;58(1):27–38. doi: 10.1002/dev.21341. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massidda D. Retimes: Reaction time analysis. R package version 0.1–2 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Mella N, Studer J, Gilet AL, Labouvie-Vief G. Empathy for pain from adolescence through adulthood: an event-related brain potential study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3:501. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00501. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Lerner MD, De Los Reyes A, Laird RD, Hajcak G. Considering ERP difference scores as individual difference measures: Issues with subtraction and alternative approaches. Psychophysiology. 2017;54(1):114–122. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12664. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DG, Richell RA, Leonard A, Blair RJR. Emotion at the expense of cognition: psychopathic individuals outperform controls on an operant response task. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(3):559–66. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.559. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran TP, Jendrusina AA, Moser JS. The psychometric properties of the late positive potential during emotion processing and regulation. Brain Research. 2013;1516:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.04.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BD, Perlman G, Hajcak G, Klein DN, Kotov R. Familial risk for distress and fear disorders and emotional reactivity in adolescence: An event-related potential investigation. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(12):2545–2556. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000471. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH, Berge JMt. Psychometric theory. 1967;226 JSTOR. [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson JK, Nordin S, Sequeira H, Polich J. Affective picture processing: an integrative review of ERP findings. Biological Psychology. 2008;77(3):247–265. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.11.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvet DM, Hajcak G. Reliability of error-related brain activity. Brain Research. 2009;1284:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich J, Kok A. Cognitive and biological determinants of P300: an integrative review. Biological Psychology. 1995;41(2):103–146. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(95)05130-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-0511(95)05130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp HT, Cuthbert BN, Bradley MM, Cacioppo JT, Ito T, Lang PJ. Affective picture processing: the late positive potential is modulated by motivational relevance. Psychophysiology. 2000;37(2):257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz A, Grillon C, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Merikangas KR. Developmental investigation of fear-potentiated startle across puberty. Biological Psychology. 2014;97:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.12.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, Janavs J, Bannon Y, Rogers JE, Wilkinson B. Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID) The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(3):313–326. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed BC, Nelson BD, Perlman G, Klein DN, Kotov R, Hajcak G. Personality and emotional processing: A relationship between extraversion and the late positive potential in adolescence. Psychophysiology. 2015;52(8):1039–1047. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12436. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed BC, Nelson BD, Auerbach RP, Klein DN, Hajcak G. Depression Risk and Electrocortical Reactivity During Self-Referential Emotional Processing in 8 to 14 Year-Old Girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1037/abn0000173. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Spieler DH, Balota DA, Faust ME. Stroop performance in healthy younger and older adults and in individuals with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1996;22(2):461. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.22.2.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton S, Braren M, Zubin J, John ER. Evoked-potential correlates of stimulus uncertainty. Science. 1965;150(3700):1187–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3700.1187. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.150.3700.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenke CE, Kayser J, Pechtel P, Webb CA, Dillon DG, Goer F, Parsey R. Demonstrating test-retest reliability of electrophysiological measures for healthy adults in a multisite study of biomarkers of antidepressant treatment response. Psychophysiology. 2017;54(1):34–50. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12758. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bulk BG, Koolschijn PCM, Meens PH, van Lang ND, van der Wee NJ, Rombouts SA, Crone EA. How stable is activation in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex in adolescence? A study of emotional face processing across three measurements. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2013;4:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2012.09.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zandt T. How to fit a response time distribution. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2000;7(3):424–465. doi: 10.3758/bf03214357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Hajcak G. Beyond good and evil: the time-course of neural activity elicited by specific picture content. Emotion. 2010;10(6):767–782. doi: 10.1037/a0020242. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Hajcak G. The late positive potential predicts subsequent interference with target processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011a;23(10):2994–3007. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2011.21630. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2011.21630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Hajcak G. Longer term test-retest reliability of error-related brain activity. Psychophysiology. 2011b;48(10):1420–1425. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01206.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan R. Effective analysis of reaction time data. The Psychological Record. 2008;58(3):475. [Google Scholar]