Abstract

Aim

Peri-implantitis (PI), inflammation around dental implants, shares characteristics with periodontitis (PD). However, PI is more difficult to control, treat, and detailed pathophysiology is unclear. We aimed to compare PI and PD progression utilizing a murine model.

Materials and Methods

Four-week-old male C57BL/6J mice had their left maxillary molars extracted. Implants were placed in healed extraction sockets and osseointegrated. Ligatures were tied around the implant and second molar. Controls did not receive ligatures. Mice were sacrificed one week, one month, and three months (n≥5/group/time point) post ligature placement. Bone loss analysis was performed. Histology was performed for: hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Tartrate Resistant Acid Phosphatase (TRAP), matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), toluidine blue, and calcein.

Results

PI showed statistically greater bone loss compared to PD at one and three months. At three months, 20% of implants in PI exfoliated; no natural teeth exfoliated in PD. H&E revealed that alveolar bone surrounding implants in PI appeared less dense compared to PD. PI presented with increased osteoclasts, MMP-8, and NF-κB, compared to PD.

Conclusion

PI exhibited greater tissue and bone destruction compared to PD. Future studies will characterize the pathophysiological differences between the two conditions.

Keywords: peri-implantitis, periodontitis, dental implant, murine model, ligature

Introduction

Peri-implantitis (PI) is a bacterial-induced inflammatory condition around dental implants, which leads to progressive crestal bone loss beyond the initial bone remodeling phase and can eventually lead to implant loss (Mombelli and Lang, 1998, No Authors Given, 2013). While dental implants have become the most desirable option to replace missing teeth, 48% of implants are expected to present with some form of complication after 10–16 years, including PI (Simonis et al., 2010). Additionally, 45% of patients present with PI; 14.5% have moderate to severe disease (Derks et al., 2016a). Dental implants are projected to pose a potential financial burden of $1.2 billion, which is equivalent to the cost of 500,000 dental implants placed in the United Stated annually; therefore, the burden to patients and clinicians is expected to increase given that the cumulative number of implants delivered over time is increasing (Sullivan, 2001, Group, 2009).

While many of the pathophysiological events in PI are similar to PD, there are also fundamental differences between the two conditions. The alveolar bone loss observed in PI is usually lost 360° around the implant fixture, while in PD bone loss is usually surface specific (Prathapachandran and Suresh, 2012). When PD is examined histologically, a zone of inflammation-free connective tissue appears to separate the area containing the inflammatory infiltrate from the alveolar bone, and this finding is not observed in PI (Lindhe et al., 1992). Furthermore, disease resolution between the two conditions appears to occur at different rates. In an experimental model of ligature-induced PI and PD performed on dogs, PD lesions tended to stabilize and presented with no further progression once the ligatures were removed from the teeth (Marinello et al., 1995, Lindhe et al., 1992). On the other hand, PI lesions almost invariably progressed and took a longer time to arrest (Marinello et al., 1995).

Several groups have investigated PI in animal models such as dogs, nonhuman primates, and mini-pigs (Schwarz et al., 2015, Zechner et al., 2004, Weber et al., 1994, Berglundh et al., 1992, Ericsson et al., 1992, Lindhe et al., 1992, Marinello et al., 1995, Schou et al., 2002, Becker et al., 2011). While valuable information has been gained through these animal models, they do not offer the advantages of mice to further investigate disease pathogenesis. For example, there are large data repositories available on the mouse genome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome, which allows for the dissection of disease pathogenesis and also comparison of data across multiple scales. Several groups have utilized a murine model to study PI, in addition, Tzach-Nahman et al utilized an oral gavage model and compared PD and PI 6 weeks after the last infection (Pirih et al., 2015a, Nguyen Vo et al., 2017, Tzach-Nahman et al., 2017).

Therefore, given the limited knowledge available concerning PI pathophysiology, the lack of an effective protocol in treating the condition, and the similarities between PD and PI, we sought to begin to characterize differences in PI and PD disease progression (one week, one month and three months) utilizing an established experimental mouse model (Pirih et al., 2015a).

Materials and Methods

Four-week-old C57BL/6J male mice (The Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were used in the study (Animal Research Committee (ARC) protocol number 02-125). The Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee of the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) (Kilkenny et al., 2010) guidelines and protocols were approved and followed. Mice were fed a soft diet ad libitum (Bio Serve; Frenchtown, NJ, USA) for the duration of the study.

Tooth Extraction and Implant Placement

Mice had their maxillary left 1st, 2nd, and 3rd molars extracted. After eight weeks of healing, implant fixtures (1.0mm long and 0.5mm in diameter), one per animal, were placed as previously described (Pirih et al., 2015a, Pirih et al., 2015b). Implant osseointegration was assessed after four weeks as previously published (Pirih et al., 2015b, Pirih et al., 2015a). During the course of tooth extraction, implant placement, and implant osseointegration, mice were given oral antibiotics ad libitum as performed previously.

Induction of Peri-implantitis and Periodontitis

Following four weeks of implant osseointegration, animals were randomly separated into control and experimental (ligature) groups (n≥5/group/time point, n=85 mice total). To induce PI and PD, 6-0 silk ligatures (P.B.N. Medicals, Stenløse, Demark) were tied around the head of the implants and the contralateral right 2nd molars. Control mice did not receive ligatures. PI and PD were evaluated at three time points: one week, one month, and three months. The resulting groups were as follows for each time point: control (no ligature) teeth, ligature teeth, control (no ligature) implants, ligature implants. Ligatures were checked weekly and re-tied if the ligature had gotten loose. Furthermore, if the ligature was not present at the termination of the experiment, the sample was removed from analysis. One week and three days before sacrifice for the one-month time point, animals were injected with calcein (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) at a concentration of 25 mg/Kg. Following sacrifice, the maxillae were collected and imaged using a digital microscope (VHX-1000; Keyence, Osaka, Japan), fixed for 48 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde, and stored in 70% ethanol. Qualitative assessment of soft tissue edema was performed using Aperio Image Scope V11.1.2.752 (Vista, CA). The healthy non-ligated groups (no ligature teeth and no ligature implants) were used as a baseline for healthy murine oral mucosa. Overt signs of tissue swelling and loss or disruption of maxillary gingival rugae were considered when qualitatively assessing tissue quality.

Micro-Computerized Tomography Analysis

Mouse maxillae were scanned as described (Pirih et al., 2015b, Pirih et al., 2015a). In brief, maxillae were scanned utilizing micro-computerized tomography (μCT) (Model 1172; SkyScan, Kontich, Belgium) at 10 micrometers resolution. Linear bone height analysis was performed using DOLPHIN® software (Navantis, Toronto, CA). Implant samples were oriented so that the shaft and the head of the implant were perpendicular to each other in the coronal and sagittal planes. The teeth were oriented such that the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) was parallel to in the coronal plane. The sagittal plane represented the middle of the second molar crown, which was oriented in the axial plane. The linear distance was measured from the junction of the head and shaft of the implant to the alveolar bone crest (ABC) or from the CEJ of the second molar vertically down to the ABC (Figure 2A). If the implant failed during PI development, bone loss was calculated as the distance from the head to the apex of the implant. A single calibrated blinded examiner measured the linear bone levels at four sites - mesial, distal, buccal and palatal – the four sites per specimen were averaged for a mean bone level value for each implant and second molar and then averaged per group.

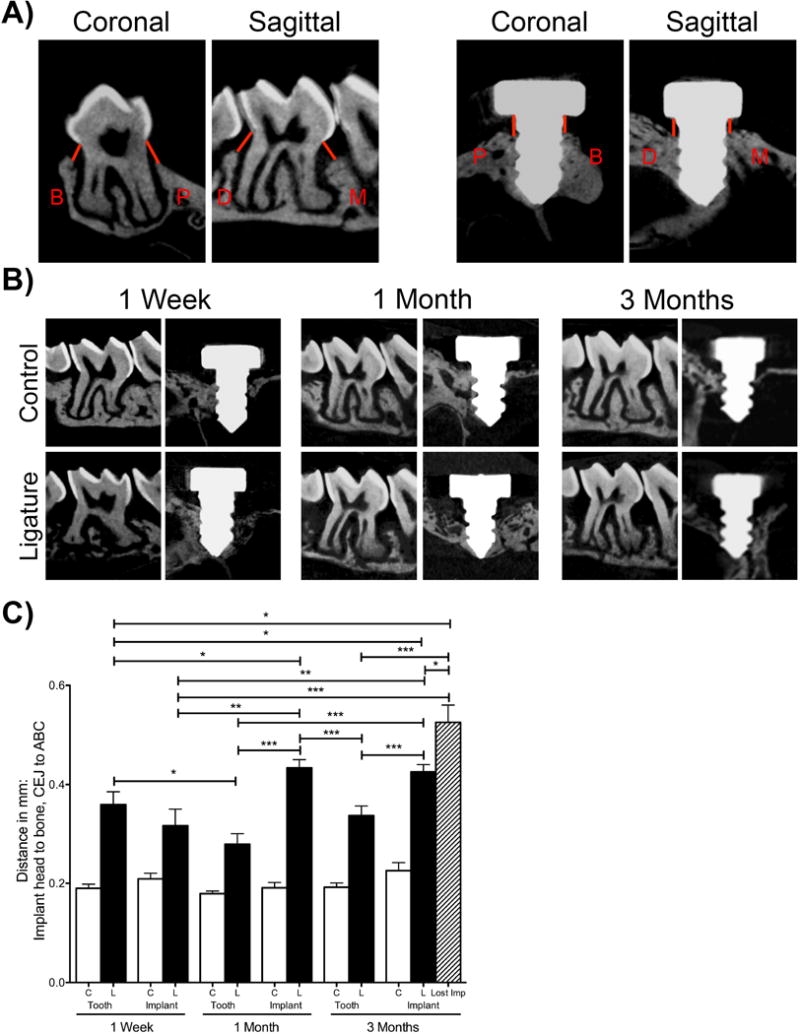

Figure Two. Radiographic evaluation after experimental periodontitis and peri-implantitis development.

(A) Orientation and location of linear bone level measurements. Red lines indicate where mm distances were recorded for M: mesial, D: distal, B: buccal, and P: palatal locations on implants and teeth. (B) Representative sagittal μCT images of control and ligature treated teeth and implants at one week, one month, and three month time points. (C) Graph represents the averaged distance from the CEJ to the ABC in teeth and from the implant head to the alveolar bone one week, one month, and three months after ligature placement. The striped bar represents the bone level of the implant-ligature group that survived in addition to 2 implants that failed. No implants were lost in other groups. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. *p<0.05, *p<0.01, ***p<0.001, # p<0.001 when comparing the ligature group to the respective control group (n≥5 for all groups/time points).

To assess volumetric bone levels, samples were oriented using DataViewer (V.1.5.2 Bruker, Billerica, MA) (Figure 3A). The long axis of the implant head was parallel to the sagittal and coronal axes and perpendicular to the axial axis. The CEJ of the second molar was parallel in the sagaittal plane and coronal planes. For both implants and teeth, circumferential volumetric bone levels were assessed in the axial plane. Using CTAn (V.1.16 Bruker, Billerica, MA), for implants, volumetric measurements were taken starting at the 10th slice below the junction of the implant head and the shaft. This area represented a normal volume of soft tissue (biologic soft tissue seal) where bone would not exist in any of the samples and served as normalization for all specimens. Volumetric measurements were taken down to the alveolar bone crest’s first appearance. For teeth, volumetric measurements started 20 slices below the CEJ going towards to tooth apices, which represented healthy bone level distances. Volumetric measurements were taken until the alveolar bone crest’s first appearance. A single blinded examiner oriented the images and performed volumetric analysis. Data from each group was averaged to determine the amount of circumferential bone loss per group.

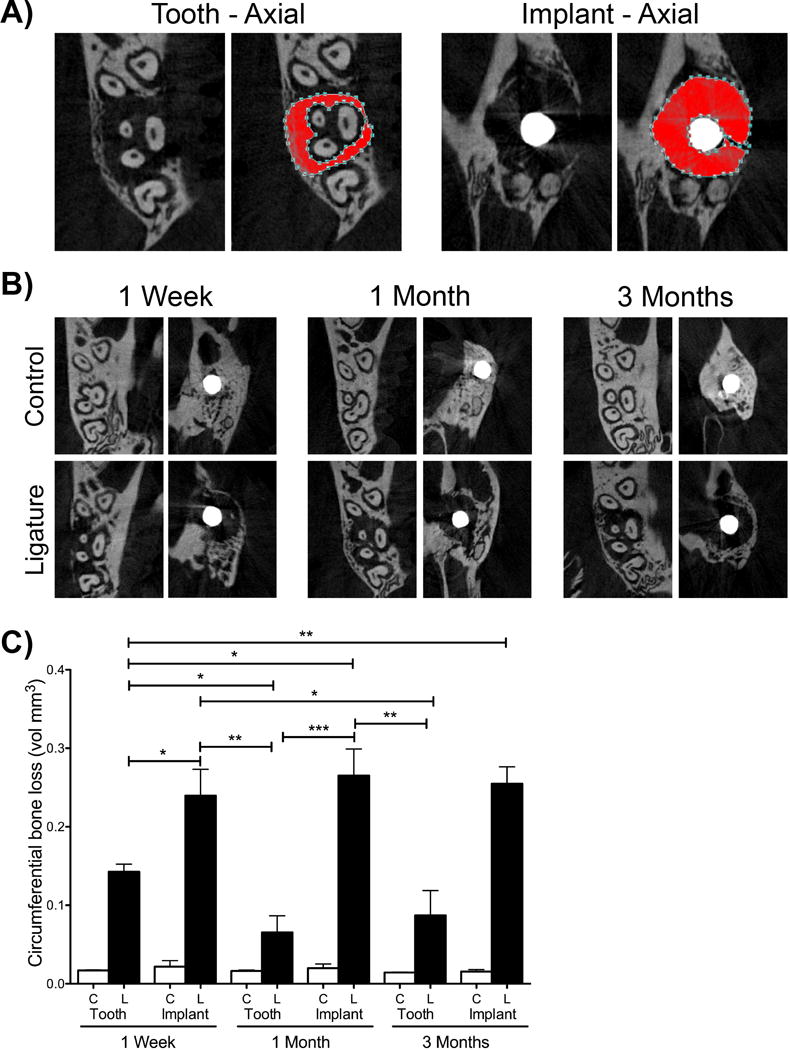

Figure Three. Volumetric evaluation after experimental periodontitis and peri-implantitis development.

(A) Orientation and location of volumetric bone level measurements for implants and teeth. The red area represents the area considered in for volumetric measurements. (B) Representative axial μCT images of control and ligature treated teeth and implants at one week, one month, and three month time points. (C) Graph represents that averaged circumferential volumetric bone loss one week, one month, and three months after ligature placement. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. *p<0.05, *p<0.01, ***p<0.001 and # p<0.001 when comparing the ligature group to the respective control group (n≥5 for all groups/time points).

Histology

Undecalcified Samples

Maxillae from the one-month time point were embedded in methylemethacrylate (Pirih et al., 2015a, Pirih et al., 2015b). Sections were ground coronally to a final thickness of ~20 μm (Scientific Solutions LLC, MN) and stained with toluidine blue (Pirih et al., 2015b, Pirih et al., 2015a). Samples were imaged using an OLYMPUS BX51 microscope using bright field or a FITC filter, respectively (Shinjuku Tokyo, Japan).

Decalcified Samples

For further histological analysis, maxillae were decalcified in 15% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for four weeks. The implants were unscrewed from the specimens in a counter-clockwise fashion. Specimens were paraffin embedded, cut into 5μm-thick slices in the sagittal plane using a microtome (McBain Instruments, Chatsworth, CA), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Pirih et al., 2015b). Additionally, samples from all time points were further stained with Tartrate Resistant Acid Phosphatase (Sigma Aldrich, MO, USA) to assess osteoclast (OC) numbers (n=3 mice/group/time point, one histological section was used per mouse). OCs were counted along the alveolar crest on the mesial and distal areas of the implant and second molar. Cells that presented with two or more nuclei and were in contact with the bone were considered OCs, as previously described (Chaichanasakul et al., 2014). OCs from the crestal mesial and distal bone areas were summed for each sample and averaged per group. Averaged OC numbers were normalized to their respective controls: implant ligature to implant control and tooth ligature to tooth control, to demonstrate fold difference. Samples from the one-week time point were further analyzed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) for matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8) (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) (anti-p65, activated form of NF-κB, 1:250; Rockland, Limerick, PA). Secondary antibody was anti-rabbit (1:200, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX). Slides were digitally imaged using Aperio Image Scope V11.1.2.752 (Vista, CA). MMP-8+ and NF-κB+ cells were semi-quantitated by counting positive cells in the mesial and distal epithelium directly under the keratinized tissue in teeth and implants. The mesial and distal sites were averaged to create a mean cell count per animal (n=3 mice for all implants, n=2 mice for all teeth).

Statistical Analysis

Linear bone height measurements, volumetric bone measurements, normalized OC numbers were averaged for all groups (mean ± standard error of the mean) and compared using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test with a 95% confidence interval. (Prism 5; GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA, USA). Significance levels were as follows: p≤0.05*, p≤0.01**, p≤0.001***

Results

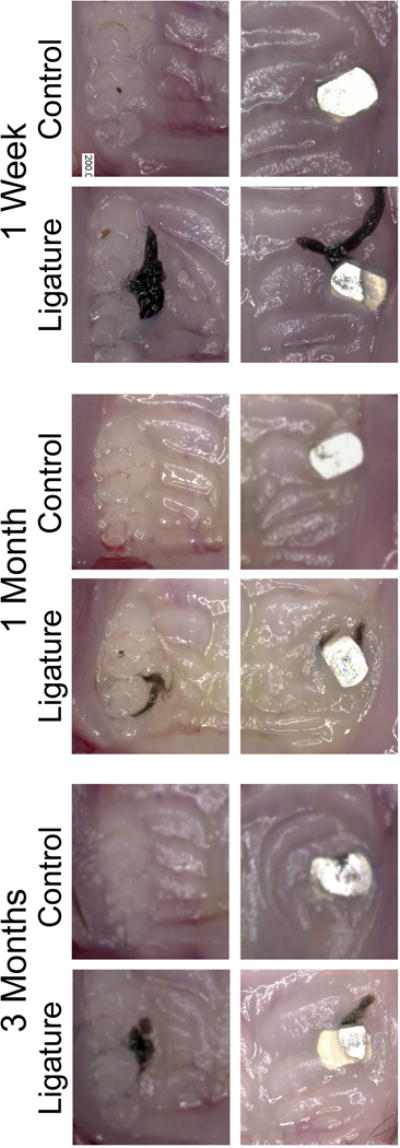

Increased Soft Tissue Edema Around Peri-Implantitis Compared to Periodontitis

Maxillae were visually assessed for soft tissue differences between control and ligature groups for both experimental PI and PD at all time points. Implant and tooth controls from non-ligature treated groups served as a baseline (healthy tissue). In the control groups, the soft tissues showed the typical clinical presentation observed in healthy murine oral mucosa. However, in the ligature-treated groups the tissues appeared edematous (Figure 1). Moreover, soft tissue edema was more prominent in the control implants and ligature-induced PI groups as compared to the ligature-induced PD group (Figure 1).

Figure One. Representative clinical images of control (no ligature) and experimental (ligature) teeth and implants at one week, one month, and three months after ligature placement.

20X magnification. Note the increased soft tissue edema around ligature treated implants compared to natural teeth.

Increased Bone Loss Around Peri-Implantitis Compared to Periodontitis

To analyze and compare the bone levels in the different groups, samples were scanned using μCT and linear bone height and circumferential bone height analysis was performed. All comparisons between control groups to their respective ligature groups showed a high level of significance (p<0.001, not shown on graphs (Figure 2C and Figure 3C)).

One week after ligature placement, there was a significant difference in bone height in the ligature-induced PD group compared to the respective control group. The bone level in the ligature-induced PI group was also significantly decreased as compared to the respective implant control group. There was no statistically significant difference between the ligature-induced PD and the ligature-induced PI groups after one week for linear measurements (Figure 2B and 2C). However, when comparing volumetric bone loss, the ligature-induced PI group showed significantly more bone loss compared to the ligature induced-PD group at the one week time point (Figure 3B and 3C).

At one month, there were significantly higher bone levels (indicating more bone loss) in the ligature groups (PD and PI) compared to their respective controls. Additionally, ligature-induced PI showed significantly higher bone levels (0.433 mm ± 0.016 mm) compared to ligature-induced PD (0.279 mm ± 0.021 mm) (Figure 2B and 2C). Again, volumetrically, the ligature-induced PI group showed significantly higher bone levels compared to the ligature-induced PD group (Figure 3B and 3C).

Results at the three-month time point were similar to the one-month data assessing linear measurements and volumetric measurements. The ligature groups showed increased bone levels when compared to non-ligature controls (Figure 2B and 2C). Furthermore, the ligature-induced PI group presented with significantly higher bone levels (0.425 mm ± 0.014 mm) compared to the ligature-induced PD group (0.337 mm ± 0.019 mm). Additionally, at the three- month time point, two implants that were ligature-treated failed (20% of the implants), while no natural teeth were lost. To account for the bone level of the implants that failed, we added another bar to our graph (striped bar). This bar represents the bone level around the ligature-treated implants that survived in addition to the two implants that failed (Figure 2C, striped bar). In the failed implants, the length of the implant was utilized as the measurement of the bone level. Throughout the duration of the experiment, the bone level remained stable in the control groups (implants and teeth) at all time points.

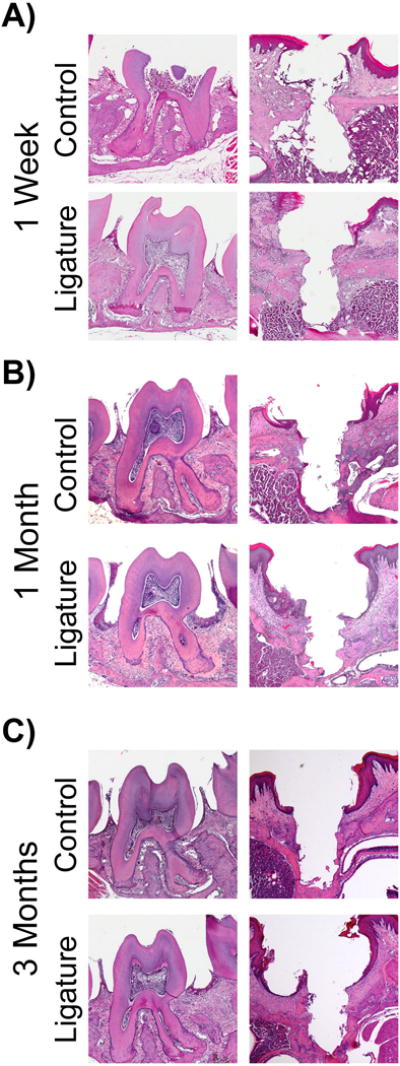

Increased Bone Resorption and Remodeling Around Peri-Implantitis Compared to Periodontitis

To assess cellular changes, histological analysis was performed. At all time points, the thickness of the soft tissues was greater on ligature-induced PI as compared to ligature-induced PD (Figure 4). Ligature-induced PI presented with less dense alveolar bone compared to ligature-induced PD. While there was less bone loss and a widening of the periodontal ligament space in ligature-induced PD, the remaining bone was largely dense (Figure 4).

Figure Four. Histological evaluation after experimental periodontitis and peri-implantitis development.

Representative sagittal H&E images of control and ligature treated teeth and implants. 20X magnification. Note the increased alveolar bone loss in ligature treated implants compared to ligature treated teeth.

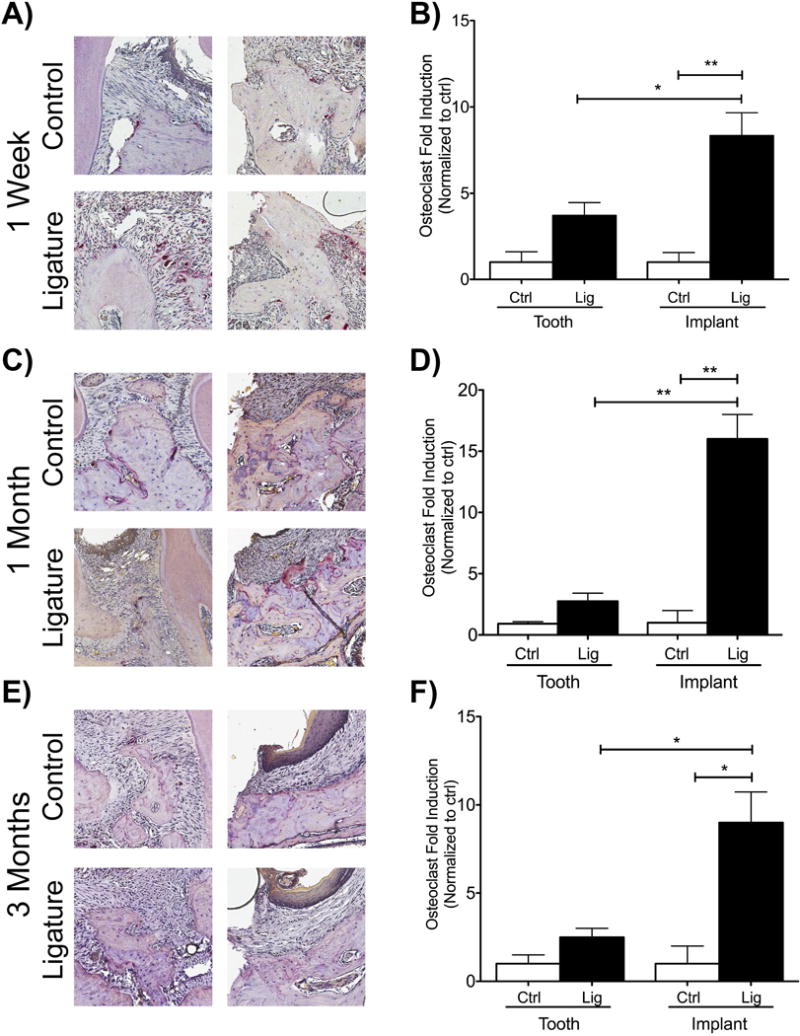

To assess osteoclast fold induction, samples from all time points were further analyzed with TRAP staining. The fold induction of TRAP+ cells in the ligature-induced PI group was significantly higher than the implant control group at all time points (Figure 5). Additionally, when the ligature-induced PI group was compared to the ligature-induced PD group, the fold induction of TRAP+ cells in the ligature-induced PI group was significantly higher than the PD group at all time points (Figure 5).

Figure Five. Osteoclastic activity after experimental periodontitis and peri-implantitis development.

(A, C, E) TRAP staining of samples one week, one month, and three months after ligature placement. (B, D, F) Graphs represent the normalized fold induction compared to controls (control teeth to ligature teeth, control implants to ligature implants) at one week, one month, and three months. Data normalized to each control, respectively. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (n=3 for all groups/time points).

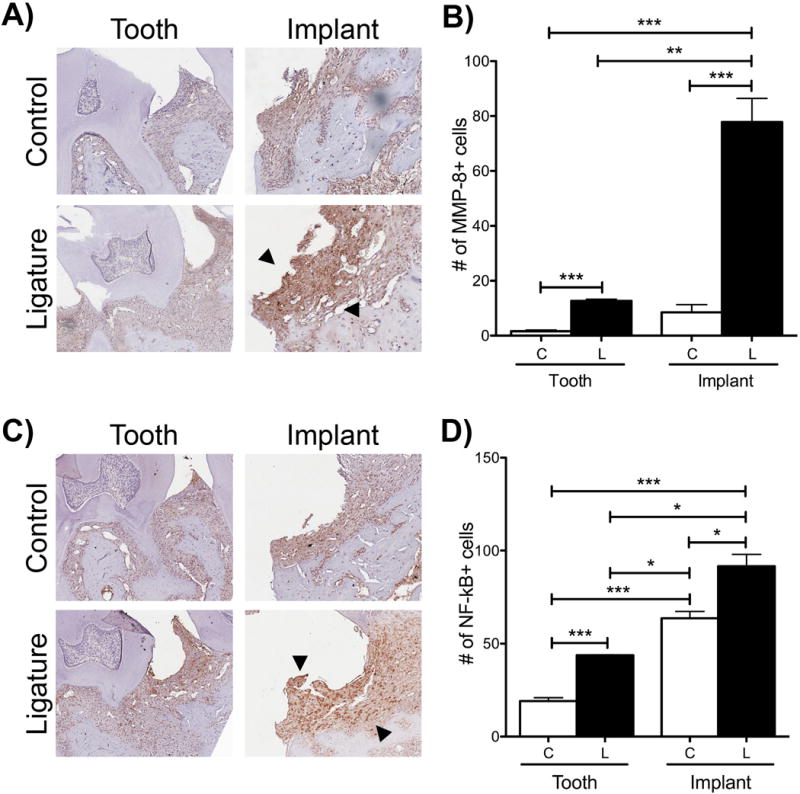

Increased Inflammatory Markers Around Peri-Implantitis Compared to Periodontitis

Degradation of the matrix membrane and transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to occur in PI and PD (Gupta et al., 2015, Arabaci et al., 2010, Thierbach et al., 2016). Therefore, the level of MMP-8 and NF-κB, which are expressed in PD, was assessed. In both groups, teeth and implants, the ligature-treated specimens showed more staining of MMP-8 and NF-κB compared to their respective controls (Figure 6). The comparison between control teeth with control implants revealed that the control implant presented with more basal MMP-8 and NF-κB immunoreactivity (Figure 6B and 6D). A similar pattern was observed in the ligature groups; ligature-induced PI presented with more immunoreactivity of both MMP-8 and NF-κB than ligature-induced PD (Figure 6B and 6D).

Figure Six. MMP-8 and NF-κB immunostaining after experimental periodontitis and peri-implantitis development.

(A) MMP-8 staining one week after ligature placement. Increased staining indicated by black arrows. (B) Graph of semi-quantitative assessment of MMP-8+ cells. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (n=3 for all implants/time points, n=2 for all teeth/time points).

(C) NF-κB staining one week after ligature placement. Increased staining indicated by black arrows. (D) Graph of semi-quantitative assessment of NF-κB+ cells. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (n=3 for all implants/time points, n=2 for all teeth/time points). For all images, magnification is at 10X.

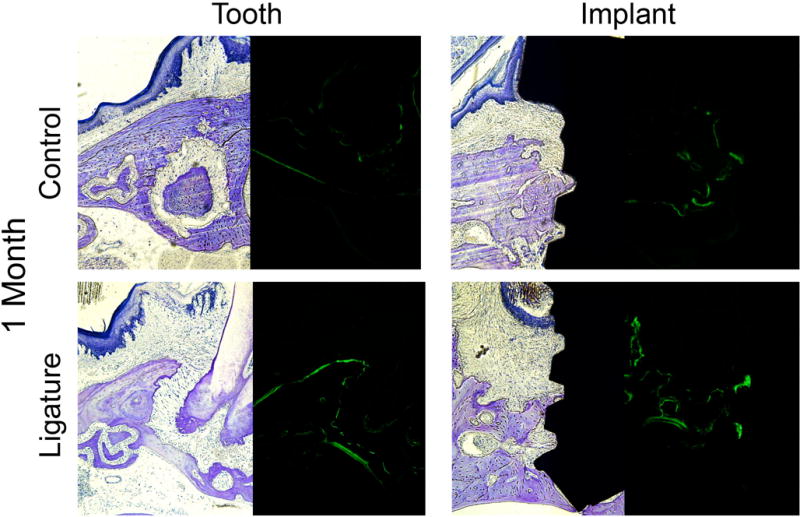

More Bone Apposition Around Peri-Implantitis Compared to Periodontitis

In order to correlate radiographic bone loss changes with histological evaluation, calcein-labeled plastic sections were assessed as a measurement of bone apposition. Examination of natural teeth showed increased fluorescence labeling in the ligature-induced PD group as compared to controls (Figure 7). In the implant group, there was increased fluorescence in ligature-induced PI as compared to controls. When comparing implants and teeth, the implant control group presented with more fluorescence compared to control teeth (Figure 7). Additionally, the bone surface in the ligature-treated implant group had more signs of remodeling, consistent with more active bone resorption compared to ligature-treated teeth.

Figure Seven. Bone apposition after experimental periodontitis and peri-implantitis development.

Toluidine blue staining (bright field) and calcein labeling (FITC) of plastic embedded tissues one month after induction of PI and PD. Note the increased fluorescence (green staining) in the implant ligature group compared to teeth. All magnification is at 10X.

Discussion

Dental implants have been used and adapted since the 1950’s to replace missing teeth and many studies have been conducted in order to design an implant with predictable long-term clinical outcomes. Despite the progress in implantology and osseointegration, complications still develop around implant fixtures and their restorations, including PI (Abraham, 2014). Predictable treatment for PI is currently not a reality, in spite of several studies in humans and animals that have attempted to understand the disease in order to develop effective treatment protocols (Derks et al., 2016b, Derks et al., 2016a).

Human studies have shed light on PI pathophysiology. For instance clinical studies have suggested that PI occurs early (within two to three years of implant placement) and in a non-linear pattern (Derks et al., 2016a, Fransson et al., 2010). Radiographically, implants with PI presented with ≥0.5mm bone loss around the implant fixture (Derks et al., 2016a). Histologically, TNF-α, IL-1α and IL-6 were increased in both PI and chronic PD; however, IL-1α was most prevalent in PI and TNF-α was more prevalent in PD, suggesting differences in pathogenesis between the two conditions (Konttinen et al., 2006). Despite these identifiable differences between PI and PD onset and progression, there are inherent confounding variables in every patient-centered study design such as oral hygiene habits, smoking status, and the presence of other systemic health conditions make data heterogeneous and difficult to analyze. This is further complicated by the fact that human studies often have small sample sizes obtained from specific ethnic cohorts. Moreover, human studies do not give a clear timeline of disease development (Fransson et al., 2010). Therefore, PI animal models play an important role in elucidating the pathophysiology of PI, and considerable information can be gathered by combining both human clinical studies and effective animal models (Abrahamsson et al., 1998, Berglundh et al., 1992, Marinello et al., 1995, Derks et al., 2016a). We elected to utilize a murine model because of the large number of tools available to dissect pathogenic pathways and the ability to genetically manipulate mouse strains to either knockout or over-express specific genes (Flint and Eskin, 2012, Mouse Genome Sequencing et al., 2002, Graves et al., 2008). Furthermore, the mouse genome shares significant similarity to humans (~98%), which allows the translation of data back to clinical studies (Attie et al., 2017). Together, these tools allow for functional interrogation of specific targets such as genes, cytokines, and immune cell populations, which are not achievable in other animal models.

In this study, we employed a mouse model of experimental PI and PD in order to exploit the advantages of a mouse study design discussed above. We observed significant differences in bone loss patterns in PI and PD. Specifically, we observed a time-dependent increase in bone loss in PI, which by three months resulted in 20% implant fixture exfoliation. This pattern was not observed in PD, where bone loss over time arrested itself. Additionally, no natural teeth had exfoliated over the course of ligature-induced disease (Figure 2). The differences in bone loss patterns observed between PI and PD corroborates previous bone loss observations in dog studies (Abrahamsson et al., 1998, Lindhe et al., 1992, Carcuac et al., 2013). In addition to increased bone loss, the PI group presented with increased osteoclasts compared to PD at all time points (Figure 5). The delicate balance between bone formation and bone resorption, through osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity, is critical in the initiation and progression of both PI and PD, and factors leading to differences in the growth and differentiation of these cell types needs to be further investigated. One of the main differences in PI and PD is that the environment in which disease occurs in PD involves the periodontal ligament (PDL) whereas in PI the bone is in direct contact with the titanium surface. The PDL, which is a form of specialized connective tissue, is critical for the strong fibrous connection between the tooth root cementum and the adjacent alveolar bone. Additionally, the PDL provides the necessary biological niche for production of immune cells that combat bacterial infections (Jonsson et al., 2011, Basdra and Komposch, 1997). The absence of the PDL around implant fixtures may have a significant effect on the susceptibility of implants to bacterial infection virtue of the bone being closer to the bacterial insult, which could account for differences in bone loss rates in PI and PD.

Histologically, we assessed soft tissues changes including the destruction of the collagen matrix via MMP-8 and the production of pro-inflammatory mediators via NF-κB (Figure 6). We observed that control and ligature-treated implants showed increased immunoreactivity of MMP-8 as compared to teeth. MMPs are involved in tissue destructive inflammatory processes, resulting in the breakdown of the membrane matrix and MMP-8 is known to play a role in PD (Teronen et al., 1997, Kivela-Rajamaki et al., 2003, Thierbach et al., 2016, Izakovicova Holla et al., 2012). MMP-8 as a biomarker for PI has been investigated and Arakawa et al. showed that increased MMP-8 was detected in PI sites with ongoing bone loss (Arakawa et al., 2012). Considering that MMP-8 is expressed in PI in patients and we observed an increase in MMP-8 in our mouse model of PI highlights the utility and translation of mouse studies back to humans. The increased immunoreactivity of MMP-8 observed in the implant control group, compared to the control tooth group, suggests that implants may present with some natural basal level of inflammation, which may make implants more readily prone to develop an inflammatory reaction compared to natural teeth. In the present study, we observed increased expression of NF-κB in PI compared to PD. NF-κB is responsible for DNA transcription, cytokine production, and cell survival, and most importantly, previous studies have shown that patients with chronic PD have increased expression of NF-κB (Arabaci et al., 2010); this suggests that data generated from mouse studies can be combined with patient studies to support the pathophysiological differences observed between PI and PD (Berglundh et al., 2011).

Three groups, including our own, have developed mouse models to study PI. The main difference in the models is that Pirih et al. placed implants in healed extraction sockets, Nguyen et al. placed implants immediately after tooth extraction, and Tzach-Nahman et al. used an oral infection model Comparing, Pirih et al. and Nguyen et al, the rate of bone loss, measured by μCT, and osteoclast patterns are similar between these two models. While the above groups have provided some characterizations of PI at the clinical, radiographic, cellular and molecular levels (Pirih et al., 2015a, Nguyen Vo et al., 2017, Tzach-Nahman et al., 2017), no studies have questioned both PI and PD simultaneously in mice as we have done herein. While the time of onset of chronic PD is not fully understood, it is believed that severe PD occurs after age 20. In contrast, several studies have reported onset of PI to be within two to three years after receiving a dental implant, suggesting that PI occurs earlier in relative terms to PD (Derks et al., 2016b). The ability to compare PI and PD simultaneously would allow for monitoring disease progression in order to better characterize chronological changes and tissue destruction in both conditions.

In conclusion, our data proposes a mouse model to compare PI and PD simultaneously. Our results share similarities with human studies that have examined the progression of PI and PD and could serve as a valuable tool in further understanding PI pathogenesis, which could lead to effective clinical treatment protocols.

Clinical Relevance.

Scientific Rational for the Study

Limited animal models are available to compare PI to its parallel condition, PD. This study serves as a foundation for further interrogation of PI and PD pathogenesis. Furthermore, murine models allow for future genetic dissection of both conditions.

Principal Findings

Increased bone levels and soft tissue destruction, specifically increased matrix degradation and pro-inflammatory mediators, were observed in PI compared to PD.

Practical Implications

Differences in immune response and pro-inflammatory pathways between PI and PD could be identified utilizing this model in order to design better clinical interventions and treatment modalities.

Acknowledgments

NIH/NIDCR DE023901-01 and a UCLA School of Dentistry Seed Grant supported this work. SH was supported by the NIH/NIDCR T90 DE022734-01. RW was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Institute NIH grant 5TL1TR000121-05. We would like to thank the Translational Pathology Core Laboratory at UCLA for assistance with preparing the decalcified histological sections. We would also like to thank Dr. Renata Pereira from the UCLA Bone Histomorphometric Laboratory and Jason Thorsten from Scientific Solutions, LLC for preparation and processing of the undecalcified sections.

Sources of Funding Statement: Hiyari reports grants from NIH/NIDCR T90 DE022734-01, during the conduct of the study. Wong reports grants from Clinical and Translational Science Institute NIH grant 5TL1TR000121-05, during the conduct of the study.

Yaghsezian has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Naghibi has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Tetradis has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Camargo has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Pirih reports grants from UCLA School of Dentistry, during the conduct of the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- ABRAHAM CM. A brief historical perspective on dental implants, their surface coatings and treatments. Open Dent J. 2014;8:50–5. doi: 10.2174/1874210601408010050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ABRAHAMSSON I, BERGLUNDH T, LINDHE J. Soft tissue response to plaque formation at different implant systems. A comparative study in the dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1998;9:73–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1998.090202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARABACI T, CICEK Y, CANAKCI V, CANAKCI CF, OZGOZ M, ALBAYRAK M, KELES ON. Immunohistochemical and Stereologic Analysis of NF-kappaB Activation in Chronic Periodontitis. Eur J Dent. 2010;4:454–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARAKAWA H, UEHARA J, HARA ES, SONOYAMA W, KIMURA A, KANYAMA M, MATSUKA Y, KUBOKI T. Matrix metalloproteinase-8 is the major potential collagenase in active peri-implantitis. J Prosthodont Res. 2012;56:249–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATTIE AD, CHURCHILL GA, NADEAU JH. How mice are indispensable for understanding obesity and diabetes genetics. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017 doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BASDRA EK, KOMPOSCH G. Osteoblast-like properties of human periodontal ligament cells: an in vitro analysis. Eur J Orthod. 1997;19:615–21. doi: 10.1093/ejo/19.6.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BECKER ST, DORFER C, GRAETZ C, DE BUHR W, WILTFANG J, PODSCHUN R. A pilot study: microbiological conditions of the oral cavity in minipigs for peri-implantitis models. Lab Anim. 2011;45:179–83. doi: 10.1258/la.2011.010174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGLUNDH T, LINDHE J, MARINELLO C, ERICSSON I, LILJENBERG B. Soft tissue reaction to de novo plaque formation on implants and teeth. An experimental study in the dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1992;3:1–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1992.030101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGLUNDH T, ZITZMANN NU, DONATI M. Are peri-implantitis lesions different from periodontitis lesions? J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(Suppl 11):188–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARCUAC O, ABRAHAMSSON I, ALBOUY JP, LINDER E, LARSSON L, BERGLUNDH T. Experimental periodontitis and peri-implantitis in dogs. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2013;24:363–71. doi: 10.1111/clr.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAICHANASAKUL T, KANG B, BEZOUGLAIA O, AGHALOO TL, TETRADIS S. Diverse osteoclastogenesis of bone marrow from mandible versus long bone. J Periodontol. 2014;85:829–36. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DERKS J, SCHALLER D, HAKANSSON J, WENNSTROM JL, TOMASI C, BERGLUNDH T. Effectiveness of Implant Therapy Analyzed in a Swedish Population: Prevalence of Peri-implantitis. J Dent Res. 2016a;95:43–9. doi: 10.1177/0022034515608832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DERKS J, SCHALLER D, HAKANSSON J, WENNSTROM JL, TOMASI C, BERGLUNDH T. Peri-implantitis - onset and pattern of progression. J Clin Periodontol. 2016b;43:383–8. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERICSSON I, BERGLUNDH T, MARINELLO C, LILJENBERG B, LINDHE J. Long-standing plaque and gingivitis at implants and teeth in the dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1992;3:99–103. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1992.030301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLINT J, ESKIN E. Genome-wide association studies in mice. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:807–17. doi: 10.1038/nrg3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANSSON C, TOMASI C, PIKNER SS, GRONDAHL K, WENNSTROM JL, LEYLAND AH, BERGLUNDH T. Severity and pattern of peri-implantitis-associated bone loss. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:442–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAVES DT, FINE D, TENG YT, VAN DYKE TE, HAJISHENGALLIS G. The use of rodent models to investigate host-bacteria interactions related to periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:89–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROUP, M. R. Global Competitor Insights for Dental Implants 2009 2009 [Google Scholar]

- GUPTA N, GUPTA ND, GUPTA A, KHAN S, BANSAL N. Role of salivary matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8) in chronic periodontitis diagnosis. Front Med. 2015;9:72–6. doi: 10.1007/s11684-014-0347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IZAKOVICOVA HOLLA L, HRDLICKOVA B, VOKURKA J, FASSMANN A. Matrix metalloproteinase 8 (MMP8) gene polymorphisms in chronic periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57:188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONSSON D, NEBEL D, BRATTHALL G, NILSSON BO. The human periodontal ligament cell: a fibroblast-like cell acting as an immune cell. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:153–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2010.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KILKENNY C, BROWNE W, CUTHILL IC, EMERSON M, ALTMAN DG, GROUP, N. C. R. R. G. W. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIVELA-RAJAMAKI M, MAISI P, SRINIVAS R, TERVAHARTIALA T, TERONEN O, HUSA V, SALO T, SORSA T. Levels and molecular forms of MMP-7 (matrilysin-1) and MMP-8 (collagenase-2) in diseased human peri-implant sulcular fluid. J Periodontal Res. 2003;38:583–90. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONTTINEN YT, LAPPALAINEN R, LAINE P, KITTI U, SANTAVIRTA S, TERONEN O. Immunohistochemical evaluation of inflammatory mediators in failing implants. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2006;26:135–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDHE J, BERGLUNDH T, ERICSSON I, LILJENBERG B, MARINELLO C. Experimental breakdown of peri-implant and periodontal tissues. A study in the beagle dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1992;3:9–16. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1992.030102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARINELLO CP, BERGLUNDH T, ERICSSON I, KLINGE B, GLANTZ PO, LINDHE J. Resolution of ligature-induced peri-implantitis lesions in the dog. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:475–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOMBELLI A, LANG NP. The diagnosis and treatment of peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000. 1998;17:63–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1998.tb00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOUSE GENOME SEQUENCING, C. WATERSTON RH, LINDBLAD-TOH K, BIRNEY E, ROGERS J, ABRIL JF, AGARWAL P, AGARWALA R, AINSCOUGH R, ALEXANDERSSON M, AN P, ANTONARAKIS SE, ATTWOOD J, BAERTSCH R, BAILEY J, BARLOW K, BECK S, BERRY E, BIRREN B, BLOOM T, BORK P, BOTCHERBY M, BRAY N, BRENT MR, BROWN DG, BROWN SD, BULT C, BURTON J, BUTLER J, CAMPBELL RD, CARNINCI P, CAWLEY S, CHIAROMONTE F, CHINWALLA AT, CHURCH DM, CLAMP M, CLEE C, COLLINS FS, COOK LL, COPLEY RR, COULSON A, COURONNE O, CUFF J, CURWEN V, CUTTS T, DALY M, DAVID R, DAVIES J, DELEHAUNTY KD, DERI J, DERMITZAKIS ET, DEWEY C, DICKENS NJ, DIEKHANS M, DODGE S, DUBCHAK I, DUNN DM, EDDY SR, ELNITSKI L, EMES RD, ESWARA P, EYRAS E, FELSENFELD A, FEWELL GA, FLICEK P, FOLEY K, FRANKEL WN, FULTON LA, FULTON RS, FUREY TS, GAGE D, GIBBS RA, GLUSMAN G, GNERRE S, GOLDMAN N, GOODSTADT L, GRAFHAM D, GRAVES TA, GREEN ED, GREGORY S, GUIGO R, GUYER M, HARDISON RC, HAUSSLER D, HAYASHIZAKI Y, HILLIER LW, HINRICHS A, HLAVINA W, HOLZER T, HSU F, HUA A, HUBBARD T, HUNT A, JACKSON I, JAFFE DB, JOHNSON LS, JONES M, JONES TA, JOY A, KAMAL M, et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420:520–62. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NGUYEN VO TN, HAO J, CHOU J, OSHIMA M, AOKI K, KURODA S, KABOOSAYA B, KASUGAI S. Ligature induced peri-implantitis: tissue destruction and inflammatory progression in a murine model. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28:129–136. doi: 10.1111/clr.12770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: a current understanding of their diagnoses and clinical implications. J Periodontol. 2013;84:436–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.134001. NO AUTHORS GIVEN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIRIH FQ, HIYARI S, BARROSO AD, JORGE AC, PERUSSOLO J, ATTI E, TETRADIS S, CAMARGO PM. Ligature-induced peri-implantitis in mice. J Periodontal Res. 2015a;50:519–24. doi: 10.1111/jre.12234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIRIH FQ, HIYARI S, LEUNG HY, BARROSO AD, JORGE AC, PERUSSOLO J, ATTI E, LIN YL, TETRADIS S, CAMARGO PM. A Murine Model of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Peri-Implant Mucositis and Peri-Implantitis. J Oral Implantol. 2015b;41:e158–64. doi: 10.1563/aaid-joi-D-14-00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRATHAPACHANDRAN J, SURESH N. Management of peri-implantitis. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2012;9:516–21. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.104867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOU S, HOLMSTRUP P, STOLTZE K, HJORTING-HANSEN E, FIEHN NE, SKOVGAARD LT. Probing around implants and teeth with healthy or inflamed peri-implant mucosa/gingiva. A histologic comparison in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) Clin Oral Implants Res. 2002;13:113–26. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2002.130201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWARZ F, SCULEAN A, ENGEBRETSON SP, BECKER J, SAGER M. Animal models for peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000. 2015;68:168–81. doi: 10.1111/prd.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMONIS P, DUFOUR T, TENENBAUM H. Long-term implant survival and success: a 10-16-year follow-up of non-submerged dental implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21:772–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.01912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SULLIVAN RM. Implant dentistry and the concept of osseointegration: a historical perspective. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2001;29:737–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TERONEN O, KONTTINEN YT, LINDQVIST C, SALO T, INGMAN T, LAUHIO A, DING Y, SANTAVIRTA S, SORSA T. Human neutrophil collagenase MMP-8 in peri-implant sulcus fluid and its inhibition by clodronate. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1529–37. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760090401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THIERBACH R, MAIER K, SORSA T, MANTYLA P. Peri-Implant Sulcus Fluid (PISF) Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) -8 Levels in Peri-Implantitis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZC34–8. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/16105.7749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TZACH-NAHMAN R, MIZRAJI G, SHAPIRA L, NUSSBAUM G, WILENSKY A. Oral infection with P. gingivalis induces peri-implantitis in a murine model: evaluation of bone loss and the local inflammatory response. J Clin Periodontol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBER HP, FIORELLINI JP, PAQUETTE DW, HOWELL TH, WILLIAMS RC. Inhibition of peri-implant bone loss with the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug flurbiprofen in beagle dogs. A preliminary study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1994;5:148–53. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1994.050305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZECHNER W, KNEISSEL M, KIM S, ULM C, WATZEK G, PLENK H., JR Histomorphometrical and clinical comparison of submerged and nonsubmerged implants subjected to experimental peri-implantitis in dogs. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2004;15:23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]