Summary

At each of the brain’s vast number of synapses, the presynaptic nerve terminal, synaptic cleft, and postsynaptic specialization form a trans-cellular unit to enable efficient transmission of information between neurons. While we know much about the molecular machinery within each compartment, we are only beginning to understand how these compartments are structurally registered and functionally integrated with one another. This review will describe the organization of each compartment and then discuss their alignment across pre- and postsynaptic cells at a nanometer scale. We propose that this architecture may allow for precise synaptic information exchange and may be modulated to contribute to the remarkable plasticity of brain function.

Introduction

Synaptic transmission carries activity-encoded information throughout the nervous system, forming the foundation of adaptive behavior and cognition. The diverse roles and regulation of synaptic transmission have driven neuroscientists to pursue a detailed understanding of the underlying functional and molecular elements. This progress is revealing that synapses are in fact comprised of three interdependent molecular assemblies, each precisely crafted to execute steps in the fast and precise information transfer between two cells. At the presynaptic active zone, depolarization opens Ca2+ channels and leads to neurotransmitter release through exocytosis of synaptic vesicles at select sites. Within the small but dense environment of the synaptic cleft, neurotransmitters diffuse from the pre- to the postsynaptic cell where they activate receptors. In the postsynaptic density, receptors are positioned to sense the highest concentration of neurotransmitter to enable fast, strong, and tunable responses. In the brain, most transmission uses glutamate as the neurotransmitter and AMPA receptor (AMPAR) ion channels to mediate postsynaptic excitation. In this review, we focus on new ideas about how these three individually fascinating compartments are integrated to form a structural unit that aligns the functional domains of the two contacting neurons.

How are synapses organized and coordinated across the pre- and postsynaptic cells on a molecular level? Several barriers have made progress difficult in answering this question. Size. From an experimental standpoint, the macromolecular machines at synapses are a rather awkward size. They are too small to be visualized by conventional microscopy, yet in several ways too large for conventional molecular biophysics and biochemistry which excel in detailing single molecules or small complexes. Critical advances in our understanding continue to rely on advancing technology. Variability of structure. Synapses come in many types that endow them with diverse functional properties. Rather than pursuing a simple search for a ‘single architecture’, this variability calls for careful deduction of shared structural properties. Moreover, different neurotransmitters may utilize quite distinct mechanisms, and the structural and molecular details of these types of synapses may vary tremendously. Even among glutamatergic synapses, structure varies widely, though the molecular underpinnings that create these structures are relatively poorly understood. Thus, to narrow the scope here in order to extract what principles we can, we focus as much as possible on the brain synapse type that has been the subject of the most intense physiological, molecular, and structural assessment, the hippocampal excitatory synapse. Plasticity. Developmental and activity-dependent plasticity leads to varied size, structure, and molecular content of even a narrowly defined synapse population. Thus, examination of synapse supra-molecular organization has not yet been able to take full advantage of powerful methods, for example superresolution microscopy or in situ 3D electron tomography, that have started to drive understanding of structures with more consistent repeated elements such as the nuclear pore complex or cytoskeleton. In the following section, we will discuss the functional properties of synapses to motivate the hypothesis that precise alignment of its structural elements is an important aspect of synaptic function.

Is there a need for precise alignment of neurotransmitter release and reception?

Exocytosis of a single vesicle only activates a fraction of receptors

At most synapse types, the magnitude of the postsynaptic response is heavily regulated, being modified over the course of development and as a result of ongoing cell activity. Changing receptor number at the synapse is a key mechanism to accomplish this (Nicoll, 2017), and the number of receptors per synapse thus varies widely, ranging from 0 to several hundred (Nusser et al., 1998; Takumi et al., 1999). CA3-CA1 synapses contain an average of near 100 AMPARs (Matsuzaki et al., 2001; Nusser et al., 1998; Takumi et al., 1999). With 2000 or more molecules of glutamate per vesicle (Burger et al., 1989), it seems that all receptors should be activated with high probability following glutamate release. For most synapses, however, not all AMPARs in a synapse contribute to quantal transmission, sometimes far from it (Lisman and Raghavachari, 2006). Single-channel current from AMPARs during EPSCs is estimated at ∼0.5 to 1 pA (Silver et al., 1996) so a synaptic response generated by activation of 100 receptors at once would likely produce an EPSC of 50 to 100 pA. Yet most miniature synaptic currents are only ∼10 to 20 pA. Indeed, perhaps as few as 10 receptors are activated during generation of an mEPSC in proximal synapses of CA1 neurons (Nimchinsky et al., 2004). Other experimental evidence further indicates that the glutamate released from a vesicle is not sufficient to saturate AMPARs: increasing the glutamate content per vesicle increases mEPSC amplitude at the calyx of Held (Ishikawa et al., 2002), and focal application of exogenous glutamate evokes larger currents than mEPSCs (Liu et al., 1999; McAllister and Stevens, 2000). These observations together suggest that not all receptors at a synapse contribute to each EPSC.

Modeling underscores potential roles of receptor alignment with release sites

If receptor number does not solely determine the strength of transmission, what else constrains the response amplitude to a quantum of glutamate? An important key is the spatiotemporal concentration profile of glutamate in the cleft after release. AMPARs require more than one molecule of glutamate (probably four) to open to their maximal conductance. They close quickly when glutamate dissociates, and like most ligand-gated channels, can enter an array of non-conducting desensitized states even when not saturated with ligand (Traynelis et al., 2010). These characteristics mean that AMPARs only open with high probability before desensitization sets in if glutamate jumps quickly to near-mM concentration. Glutamate is at a high concentration in vesicles, and its rapid escape into the cleft during opening of the exocytic fusion pore sets the stage for such a stimulus. However, the amount per vesicle is limited, and in the cleft, this bolus likely disperses rapidly via diffusion. Receptors thus have only a brief opportunity to interact with glutamate and potentially to open.

To determine how glutamate released from a vesicle leads to opening of receptors during this moment, a number of groups have assembled mathematical models that incorporate known features of glutamate release and diffusion with measured cleft geometry and receptor biophysical parameters (Franks et al., 2002; Freche et al., 2011; Holmes, 1995; Raghavachari and Lisman, 2004; Savtchenko and Rusakov, 2014; Tarusawa et al., 2009; Uteshev and Pennefather, 1996; Wahl et al., 1996; Xie et al., 1997; Xu-Friedman and Regehr, 2004). A consistent prediction across models is that the glutamate concentration profile reaches a very high peak (over 1 mM), but only for a brief time period (∼100 µsec) and over a small distance (∼100 nm). Because of this, AMPARs displaced from the site of release are not activated nearly as efficiently (Freche et al., 2011; Raghavachari and Lisman, 2004; Savtchenko and Rusakov, 2014; Uteshev and Pennefather, 1996). The deduced drop-off depends on a number of factors, but receptors displaced even by just 100 nm are generally predicted to be 30 to 80% less likely to open, and those 200 nm away are only 10 to 40% as likely (Raghavachari and Lisman, 2004; Tarusawa et al., 2009; Uteshev and Pennefather, 1996; Xu-Friedman and Regehr, 2004). Critically, the area containing the maximally activated receptors (<0.01 µm2) is substantially smaller than the area of the majority of postsynaptic densities (PSDs), which in CA1 are on average ∼0.07 µm2 (Harris and Weinberg, 2012). Thus, a variety of models support the expectation from physiological considerations that AMPARs are not maximally activated (Holmes, 1995; Xu-Friedman and Regehr, 2004). The most straightforward conclusion from this consensus is that the response to a quantum of glutamate will be only weakly sensitive to the total number of receptors in the PSD, but in fact strongly sensitive to the density of receptors in the region near the site of release.

Incorporating kinetics of NMDA receptors (NMDARs) to these models provides similar insights to their activation. As for AMPARs, the sharp glutamate transient within the cleft means that only a subset of NMDARs has a chance to bind the two glutamate molecules required for opening (Holmes, 1995; Santucci and Raghavachari, 2008; Savtchenko and Rusakov, 2014; Xie et al., 1997). This is perhaps counterintuitive, because NMDAR affinity is considerably higher and the receptors are well known to be more sensitive to even the low concentrations of glutamate that escape the cleft (“spillover”) to affect neighboring synapses (Kullmann and Asztely, 1998). However, because the period of glutamate exposure is so brief, it is the rate of glutamate binding to the receptor, not its affinity that is most critical. An important consequence of this is that the slow glutamate binding rate of the GluN2B subunit (Erreger et al., 2005) conveys a substantial sensitivity to distance from the release site. While the sensitivity of receptors containing only A-type GluN2 subunits does not change until this distance reaches ∼500 nm, the activation probability of GluN2B-containing NMDARs drops to only 35% when spaced 200 nm from the release site (Santucci and Raghavachari, 2008). Though many receptors in mature hippocampus are likely to be triheteromeric (GluN1/N2A/N2B), their glutamate binding rates have not been detailed (Hansen et al., 2014). This rate is likely dominated by the slower binding of GluN2B, suggesting that triheteromeric receptors may also display significant location sensitivity. Given the broad importance of both action potential-driven and spontaneous activation of NMDARs, this places a high priority on understanding the distribution of their subtypes within the synapse.

Such models also help identify important positional parameters that may contribute to functional variety among synapses, including during activity-dependent plasticity. One very revealing prediction based on modeling is that adding channels at the synapse periphery will make relatively little difference to the response amplitude (Raghavachari and Lisman, 2004; Savtchenko and Rusakov, 2014). Indeed, this prediction was recently tested with an elegant optical dimerization strategy (Sinnen et al., 2017), which showed that experimental delivery of substantial numbers of receptors to engineered bait sites in the PSD increased the response to glutamate uncaged at the synapse--but not to synaptic stimulation. This suggests that to strengthen a synapse, receptors would need to be added in positions coordinated with release sites (Lisman and Raghavachari, 2006). In addition, though glutamate from a single vesicle may not activate all receptors, near-simultaneous release of more than one vesicle following an action potential, which is prominent at some synapses (Foster et al., 2005; Tong and Jahr, 1994) but not others (Christie and Jahr, 2006; Tang et al., 2016), will substantially alter the glutamate concentration transient and likely increase response amplitude (Freche et al., 2011; Raghavachari and Lisman, 2004; Xu-Friedman and Regehr, 2004). This effect may also play a particularly important role during presynaptic facilitation of release probability. Despite these useful insights, it is important to note that synapses of differing function may control response amplitude through different mechanisms. For instance, at two “relay” synapses in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus where plasticity is not prominent in adulthood, modeling suggests that the number of receptors present establishes response amplitude (Tarusawa et al., 2009).

Overall, modeling approaches suggest that the location of vesicular release relative to receptors may be a critical determinant of synaptic strength, and experimental data support this hypothesis. We will now review the structural organization of each synaptic compartment that may make this possible, before we discuss evidence and propose potential mechanisms for alignment among them.

Relevant structures and their patterning in the three synaptic compartments

The molecular and functional organization of neurotransmitter release

Exocytosis of synaptic vesicles does not occur evenly spread over the surface of a nerve terminal, but is restricted to small membrane domains and to a subset of vesicles called readily releasable vesicles (Kaeser and Regehr, 2017). These vesicles fuse at active zones, exocytotic areas that are restricted to the presynaptic membrane opposed to the PSD (Couteaux and Pecot-Dechavassine, 1970; Sudhof, 2012). For the purpose of this review, we use the term active zone to describe the molecular machinery consisting of proteins and lipids that mediates fusion at the membrane opposed to the PSD, and that contains one or multiple sites for exocytosis of synaptic vesicles (Figures 1A and 1B). A long-standing interest in synaptic neuroscience has been to understand the molecular nano-architecture and function of the active zone. First insights came from electron microscopic studies of small central nervous synapses, where upon fixation the presynaptic membrane is decorated with proteinaceous material that forms dense projections in a hexagonal grid (Bloom and Aghajanian, 1966; Pfenninger et al., 1969; but also see Gray, 1975). It was proposed that this matrix provides several distinct sites for vesicle docking and fusion. Detailed and compelling work at the frog neuromuscular junction has built on these studies and found that the presynaptic plasma membrane is connected with docked synaptic vesicles through stereotyped, repetitive elements that extend from the plasma membrane as pegs, ribs and beams (Harlow et al., 2001). Although the same stereotypy has not been described at small central synapses, the fundamental elements - transmembrane proteins, dense proteinaceous bodies that project into the cytoplasm, and filaments and tethers that connect to vesicles - are also present (Fernandez-Busnadiego et al., 2010; Lucic et al., 2005; Nagwaney et al., 2009; Siksou et al., 2007).

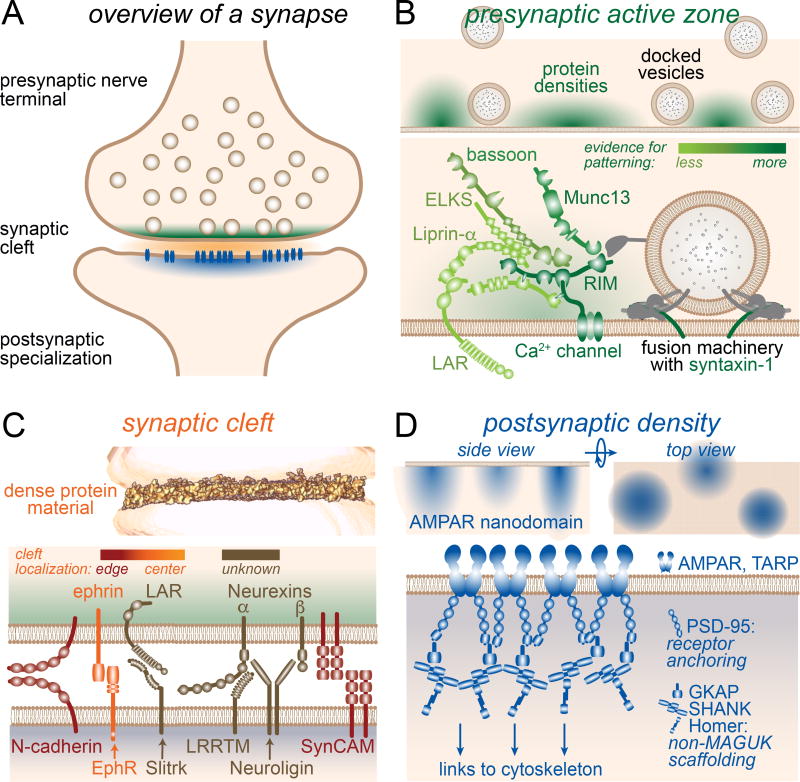

Figure 1. The machines of the synapse.

(A) Overview of an excitatory synapse with the active zone material (green), the synaptic cleft material (orange) and the postsynaptic density (blue) highlighted in a color code that is maintained throughout the manuscript.

(B) Patterning (top) and molecular components (bottom, adapted from Kaeser et al., 2011) of the presynaptic active zone area.

(C) 3D tomogram of the protein complexes in side view (top, adapted from Perez de Arce et al., 2015) and its molecular components (bottom) of the synaptic cleft. Individual cleft proteins are discussed in the text. Notably, proteinaceous material within the cleft is distinctly distributed, with the highest density in the outer ring.

(D) Lateral patterning of the postsynaptic density in side and top view (top) and patterned molecular components of a single cluster (bottom) of the postsynaptic density. The PSD material including receptors is organized in ∼2–3 distinct clusters per synapse and is also layered vertically into functionally relevant zones.

Electron microscopy and high resolution, live-cell imaging have recently allowed for the localization of functional vesicle fusion sites within hippocampal synapses. Analysis of putative fusion events at synapses that are fixed with high pressure freezing within ∼10 ms of optogenetic stimulation and analyzed by electron microscopy have revealed a tendency for release towards the center of the active zone (Watanabe et al., 2013). Superresolution localization of individual exocytotic events either aggregated from separate events in multiple synapses (Park et al., 2012) or many events in single synapses (Maschi and Klyachko, 2017; Tang et al., 2016) have shown that individual fusion events are not confined to a single spot, but may be spread out over a subarea of the active zone, perhaps with differences between action potential-mediated and spontaneous fusion events.

Fusion itself, the merging of the vesicular with the target membrane, is executed by SNARE proteins and triggered by Ca2+ binding to the vesicular protein synaptotagmin (Fig. 2b) (Jahn and Fasshauer, 2012; Sudhof, 2013). However, these proteins do not account for the localization of fusion, because target membrane SNARE proteins are not concentrated at the active zone but widespread across the axonal membrane (Garcia et al., 1995; Pertsinidis et al., 2013; Vardar et al., 2016; Wilhelm et al., 2014). Over the past two decades, six protein families have emerged as key organizers of the active zone (Schoch and Gundelfinger, 2006; Sudhof, 2012). RIM proteins are scaffolds that precisely localize at sites of fusion (Kaeser et al., 2011; Schoch et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 1997). They organize the priming and docking of synaptic vesicles (Calakos et al., 2004; Deng et al., 2011; Han et al., 2015; Kaeser et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016), and together with RIM-BPs, tether presynaptic Ca2+ channels (Acuna et al., 2015; Han et al., 2011; Hibino et al., 2002; Kaeser et al., 2011; Müller et al., 2012). RIMs also anchor and activate Munc13s (Andrews-Zwilling et al., 2006; Betz et al., 2001; Deng et al., 2011), essential proteins for vesicle priming and tight membrane attachment of synaptic vesicles (Augustin et al., 1999; Imig et al., 2014; Varoqueaux et al., 2002). In contrast to RIMs and Munc13s, the other families of active zone proteins are less well understood. ELKS forms molecular scaffolds to enhance Ca2+ influx and to modulate the readily releasable pool (Held et al., 2016; Kaeser et al., 2009; Kawabe et al., 2017; Kittel et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016). Bassoon and Piccolo are highly enriched at the active zone (Dani et al., 2010) and contribute indirectly to Ca2+ channel targeting (Davydova et al., 2014). Liprin-a proteins serve as active zone scaffolds in the fly and C. elegans NMJ (Kaufmann et al., 2002; Zhen and Jin, 1999), but the localization and function of vertebrate Liprin-a proteins are not well understood. In addition, many other proteins, including cytoskeletal elements, transmembrane scaffolds, and ion channels are present (Boyken et al., 2013; Muller et al., 2010), but are not restricted to the active zone area. Together, a consensus arises that these proteins generate an intricately organized machine that targets fusion to specific sites within an active zone. Indeed, recent advances in imaging have provided evidence for a fine substructure within the active zone, for example a specific orientation of bassoon (Dani et al., 2010), and inhomogeneity in their distribution to generate release hot spots (Tang et al., 2016).

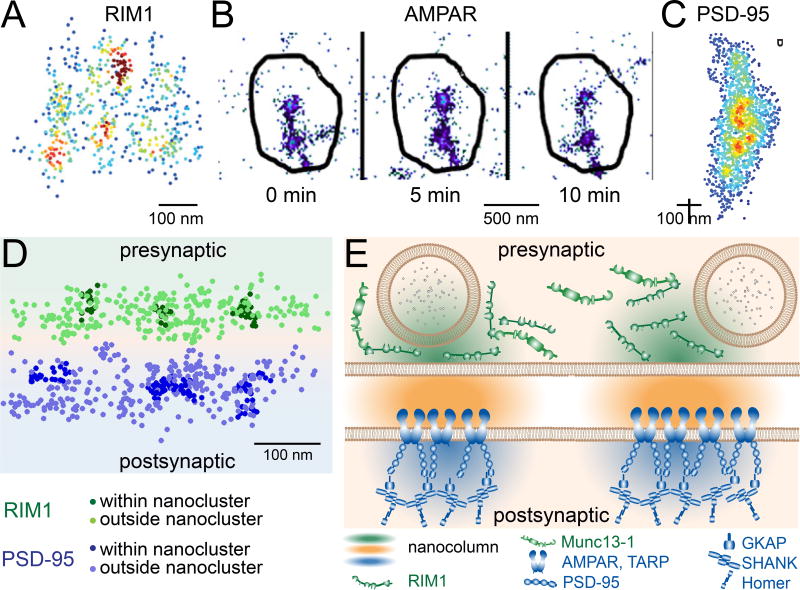

Figure 2. Evidence for alignment.

(A) Clustered distribution of RIM1 within a single active zone, visualized via STORM and rotated to view along the synaptic axis parallel to the presynaptic plasma membrane. Points indicate position of localized molecules, and color encodes the relative number of other nearby molecules with red being the highest and blue the lowest. (Adapted from Tang et al., 2017.)

(B) Clustering of AMPARs visualized by time-lapsed single-molecule mapping. Receptors (points) concentrate in small subdomains of a single PSD (outline). Most receptors are in motion, but the nanoclusters remain stable for long periods. (Adapted from Nair et al., 2013.)

(C) Clustered distribution of PSD-95 within a single PSD, displayed as in A. (Adapted from MacGillavry et al., 2013).

(D) Trans-synaptic alignment of nanoclustered RIM1 and PSD-95 visualized by 3D dSTORM. The synapse has been rotated to view perpendicular to the synaptic cleft.

(E) The “nanocolumn” of protein alignment spanning the two connected neurons. Concentrated RIM helps establish preferential release sites in the active zone which align within 10s of nanometers to clusters of AMPARs. The density of cleft protein (orange) within the nanocolumn has not been measured, but Munc13 co-enriches with RIM in the active zone, and Shank, GKAP, and Homer co-enrich with PSD-95.

None of these active zone proteins has a transmembrane domain. A central, unresolved question for understanding how fusion is targeted to particular membrane sites within a nerve terminal is how the active zone material is attached to the target membrane. The membrane link of the active zone protein complex could be mediated by interactions with transmembrane proteins or with membrane lipids that are specifically targeted to fusion sites. Interactions of Liprin-a with LAR (leukocyte common antigen-related receptor) phosphotyrosine phosphatases (Serra-Pages et al., 1998; Um and Ko, 2013) provide for a candidate mechanism, but the precise localization of vertebrate Liprin-a and LAR proteins remains to be addressed. Although no specific interaction between the active zone and other cell adhesion proteins are known, neurexins and other presynaptic membrane proteins could also provide important links (Südhof, 2008), but it remains to be determined whether these trans-synaptic organizers are localized to the active zone. Presynaptic CaV2 Ca2+ channels are localized within the active zone, and could functionally define sites for exocytosis (Bucurenciu et al., 2008; Eggermann et al., 2011; Holderith et al., 2012; Miki et al., 2016). Because they directly interact with several active zone proteins including RIM-BPs and RIMs (Hibino et al., 2002; Kaeser et al., 2011; Kiyonaka et al., 2007), they may contribute to membrane anchoring of the active zone, roles that are consistent with studies of the neuromuscular junction of Ca2+ channel knockout animals (Chen et al., 2011). Finally, several active zone proteins, for example Munc13, RIM and Bassoon, contain C2 domains and other lipid binding modules that could explain molecular tethering to membranes. In particular, PIP2 has been suggested to be enriched at sites of vesicle fusion (Honigmann et al., 2013; van den Bogaart et al., 2011), and interactions of Munc13 with PIP2 have been shown to modulate release (Shin et al., 2010). Future experiments will need to provide understanding of the membrane attachment of the active zone, which will reveal mechanisms for the spatial organization of fusion sites.

Multiple exocytotic sites reside within an active zone

A long-standing interest in presynaptic research has been to determine whether there are multiple concrete sites at which vesicles fuse within an active zone, and several approaches have been used to address this question. Electron-microscopic studies have provided early insight into the number of presynaptic release sites. Given that fusion is executed within less than a millisecond upon presynaptic depolarization by an action potential (Borst and Sakmann, 1996; Sabatini and Regehr, 1999), rapidly releasable vesicles must be close to their future sites of release. Recent advances in tissue fixation and tissue electron tomography have allowed to precisely determine the number of tightly docked vesicles at hippocampal synapses, and this number is estimated to be 10–15 vesicles per active zone (Imig et al., 2014; Kaeser and Regehr, 2017; Siksou et al., 2009). However, it is possible that not all docked vesicles are releasable, and that some release sites may not be occupied by docked vesicles because docking may be a dynamic, reversible process (Kaeser and Regehr, 2017; Miki et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Zenisek et al., 2000). Hence, counting docked vesicles may not be an accurate measurement of release site numbers.

Electrophysiological measurements have been used to determine the numbers of release sites based on the statistics of synaptic transmission. These measurements have typically provided lower numbers, in the range of 1–3 sites (Miki et al., 2016; Silver et al., 2003; Stevens and Wang, 1995) per active zone, but numbers >5 have also been reported (Oertner et al., 2002). Because these estimates are indirect, they may bias the analysis to sites with a relatively high release probability, for example those closer to Ca2+ channels. Two recent studies have used microscopy to determine the localization of individual vesicle fusion events at hippocampal synapses, with the resolution limited by the size of a synaptic vesicle (Maschi and Klyachko, 2017; Tang et al., 2016). One study subsequently used clustering analysis to determine how many distinct sites were present in a single active zone (Maschi and Klyachko, 2017). It concluded that, if the diameter of a site is limited to 70 nm, an active zone has approximately ten exocytotic sites. The other study has used a different approach: it localized fusion relative to proteins important for secretion, and found a good correlation between fusion site localization and clustering of RIM (Tang et al., 2016). In independent experiments, it was established that RIM forms ∼2 clusters per active zone, each with a diameter of 80 nm. Hence, functional and ultrastructural measurements have provided a relatively wide estimate of release site numbers per active zone, ranging from 1–15 sites.

An intuitive hypothesis is that the localization of Ca2+ channel clusters, which provide Ca2+ to trigger release (Eggermann et al., 2011), marks release sites. If this were true, one could estimate release site numbers by determining the number and localization of Ca2+ channel clusters. Using freeze fracture followed by immunogold labeling, it was found that Ca2+ channels may be non-randomly distributed within active zones of local CA3 pyramidal cell axons (Holderith et al., 2012). At cerebellar parallel fiber to interneuron synapses, a good correlation between the number of Ca2+ channel clusters and electrophysiologically measured release sites (Miki et al., 2017) supported the idea that Ca2+ channel clusters are release sites. However, a large body of literature paints a more complex picture of the relationship of Ca2+ channels and exocytotic sites. Functional measurements, largely relying on measurements of kinetics of Ca2+ buffering, have revealed that different synapses use very different strategies for Ca2+-secretion coupling, with distances between Ca2+ source and sensor that range from 10 nm to >100 nm (Bucurenciu et al., 2008; Eggermann et al., 2011; Keller et al., 2015; Nakamura et al., 2015). Similarly, at Schaffer collateral synapses, a variable arrangement between Ca2+ channels and releasable vesicles may account for release properties, suggesting that direct molecular tethers between Ca2+ channels and vesicles may not be required at all (Scimemi and Diamond, 2012), or at least not for all vesicles. Finally, estimates of the number of channels necessary to trigger a single release event range from 1 to >10 (Borst and Sakmann, 1996; Bucurenciu et al., 2008; Fedchyshyn and Wang, 2005; Sheng et al., 2012; Stanley, 1993; Tarr et al., 2013), and Ca2+ channels appear mobile (Schneider et al., 2015), further complicating the interpretation of Ca2+ channel clusters as a precise assessment of release site number. Thus, similar to the counting of docked vesicles, it is unlikely that assessing Ca2+ channel clusters is directly reporting functional release sites.

A parsimonious interpretation of these diverse estimates for the number of release sites could be that vesicle fusion occurs within tens of nanometers of active zone protein clusters, for example of RIM, which could generate a membrane area permissive for fusion. This fusion area may contain several distinct sites with variable properties, depending on other factors such as the concentration of SNARE proteins, distance to Ca2+ channels, and lipid heterogeneity. This interpretation could account for the tendency towards larger measurements of site numbers when the number of docked vesicles is determined or single vesicle release events are imaged.

Molecular nano-organization of the synaptic cleft

The second structurally organized compartment of synapses is their cleft. Rather than just a gap, the synaptic cleft is a protein-rich environment (Figure 1C) whose components can drive synaptogenesis and modulate synaptic maturation and transmission. The electron dense material in the cleft was already distinguished as “a band of extracellular material” in the earliest EM studies (Gray, 1959). Subsequent work has revealed the existence of bridging fibrils anchored to intramembrane particles as well as fibril-like structures oriented parallel to the synaptic membranes (Ichimura and Hashimoto, 1988). These studies paved the way for more recent analyses that helped to define the cleft of excitatory synapses as a structurally organized compartment. This progress showed that the cleft is comprised of distinct macromolecular complexes that span the pre- and post-synaptic membranes (Burette et al., 2012; Lucic et al., 2005; Zuber et al., 2005). The packing of these complexes results in a protein density in the cleft that is even higher than in the cytoplasm (Zuber et al., 2005). The density within the cleft is not uniformly distributed and is increased in a central layer parallel to the membranes (Burette et al., 2012; Perez de Arce et al., 2015). In addition, the cleft’s edge exhibits increased electron density compared to the inner volume (Burette et al., 2012; Perez de Arce et al., 2015). These patterns of density suggest the existence of unique subdomains of the cleft that could perform distinct functions in organizing synapses.

Macromolecular studies show that the cleft is comprised of trans-synaptic complexes, which are arranged in periodically organized patterns with a laterally connected, net-like structure (Lucic et al., 2005; Zuber et al., 2005). This patterning is very similar at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction (Prokop, 1999; Zhan et al., 2016), indicating evolutionary conservation. Recent electron tomographic studies, using high pressure freezing to better preserve cleft architecture, have distinguished numerous types of macromolecular complexes that are restricted to the cleft (High et al., 2015), providing further support that the synaptic cleft is a highly organized structure.

Insights into the molecular identify of these complexes has come from the analysis of synapse-organizing adhesion molecules. This diverse group of pre- and post-synaptic membrane proteins (Figure 1C) is defined by their localization to synaptic sites and their ability to modulate and even instruct synapse development and maturation (de Wit and Ghosh, 2016; Krueger-Burg et al., 2017; Missler et al., 2012). Early studies focused on synaptogenic activities of these proteins, and determined that several synaptic adhesion molecules are each sufficient to induce functional presynaptic release sites or postsynaptic specializations in cell culture systems. This led to the characterization of the postsynaptic neuroligins (Scheiffele et al., 2000) and the SynCAM immunoglobulin proteins (Synaptic Cell Adhesion Molecules, also known as CADMs and nectin-like proteins) (Biederer et al., 2002) as synapse-organizing adhesion molecules that induce presynaptic sites. Similarly, the presynaptic ligands of neuroligins called neurexins were identified as inducers of postsynaptic assemblies (Graf et al., 2004). However, the loss of all three neuroligins in vivo causes no decrease in excitatory synapse number in multiple brain regions except for small subsets of synapses, and instead affects synaptic function (Varoqueaux et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2015), arguing that neuroligins are not required synaptogenic factors across neuron types. Neuroligins may control synapse number in a competitive manner, though, as cortical and hippocampal neurons with lowered neuroligin-1 expression that are surrounded by wild-type neurons have a reduced potential to form dendritic spines (Chih et al., 2005; Kwon and Sabatini, 2011; Shipman and Nicoll, 2012). Another study of recently developed conditional knock-out mice, however, found no evidence that differential neuroligin levels between neurons alter spine numbers (Chanda et al., 2017). In addition to these synapse- and neuron-type specific effects on synapse number, neuroligins modulate activity-dependent postsynaptic maturation and plasticity (Chubykin et al., 2007; Jedlicka et al., 2015; Shipman and Nicoll, 2012; Soler-Llavina et al., 2011) and neuroligin-1 in addition acts across the cleft to promote presynaptic maturation with effects on active zone stability and synaptic vesicle pool size (Wittenmayer et al., 2009). The analysis of neuroligins therefore supports that their endogenous functions are highly diverse depending on synapse type and include the modulation of synaptic properties as well as of their number.

A similar conclusion also holds true for neurexin on the presynaptic side. Here, loss of neurexins in mice reduces excitatory synapse number at select synapses such as climbing fiber inputs to Purkinje cells (Chen et al., 2017) but not in other brain regions (Dudanova et al., 2007). In terms of physiological maturation, neurexins are critical synaptic organizers as first shown in vivo by the result that α-neurexin loss impairs evoked neurotransmission (Missler et al., 2003). Additional evidence for instructive roles of trans-synaptic organizers in synapse development comes from studies of another class of postsynaptic neurexin ligands called LRRTM proteins (de Wit and Ghosh, 2016), LAR phosphotyrosine phosphatases that signal on the presynaptic side (Takahashi and Craig, 2013), and SynCAM 1, which is preferentially postsynaptic and required and sufficient to control the number of excitatory synapses in vivo (Park et al., 2016; Korber and Stein, 2016; Robbins et al., 2010). The subsynaptic functions of these and other adhesion molecules could include localization or retention of pre- and post-synaptic nanodomains at developing and mature synapses, altering the geometry of the cleft and hence the diffusion of neurotransmitters, or modulating presynaptic Ca channel function (Freche et al., 2011; Glebov et al., 2016; Tong et al., 2017; Wahl et al., 1996). Adhesion molecules also provide candidate mechanisms for the trans-synaptic alignment of nanocolumns, as discussed later.

Nanodomains of receptors within the PSD

Similar to the active zone and synaptic cleft, the PSD is not a homogenous collection of proteins but a machine with a striking architecture patterned in three dimensions (Figure 1D). In the “lateral” dimension parallel to the synaptic membranes, each of the glutamate receptor subtypes has a distinctive subsynaptic distribution. Indeed, receptor activation will be controlled by this positioning (MacGillavry et al., 2011). AMPARs are enriched a few-fold in the PSD overall compared to extrasynaptic membrane, but within synapses, their distribution is typified by subregions of much higher density termed receptor nanoclusters or nanodomains (MacGillavry et al., 2013; Nair et al., 2013; Tarusawa et al., 2009). Generally, hippocampal synapses contain one to three such nanodomains, roughly 80 to 100 nm in diameter (Figure 2). Larger synapses containing more nanodomains, and spines may contain more than twice this when bearing multiple PSDs (MacGillavry et al., 2013; Nair et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2016). Estimates of receptor number per nanodomain in these synapses range up to 25 (out of a typical average of ∼100/synapse), roughly 20 nm center-to-center spacing—whereas synapse in other brain regions may have substantially higher densities (Masugi-Tokita et al., 2007).

Whereas AMPARs and AMPAR nanoclusters are found broadly throughout the PSD, the distribution of NMDARs is weighted towards the center of the PSD (Kharazia and Weinberg, 1997; Perez-Otano et al., 2006; Racca et al., 2000). NMDARs grouped in a nanodomain near the center of the PSD have been observed by EM tomography (Chen et al., 2008), potentially with reduced AMPAR density in this area. Using STORM immunocytochemistry to survey large numbers of synapses efficiently also revealed a clustered distribution of NMDARs within single synapses of olfactory bulb (Dani et al., 2010), though the position of clusters within the synapse was quite variable. AMPAR and scaffold clusters (see below) tend to be more peripheral but can occur anywhere in the synapse (Dani et al., 2010; Tang et al., 2016), suggesting that the synaptic center per se is not endowed with unique molecular properties. At the other extreme, group I metabotropic receptors are strongly enriched at the edge of the PSD (Lujan et al., 1996).

Lateral patterning of cytosolic PSD components

What underlies the clustered distribution of synaptic receptors? The clearest candidates are the Membrane Associated Guanylate Kinase (MAGUK) scaffold proteins typified by PSD-95 in mature synapses. These bind AMPAR auxiliary proteins, of which the Transmembrane AMPA Receptor Regulatory Proteins (TARPs) like stargazin are the best studied, and synaptic retention of AMPARs is disrupted by interference with TARP-MAGUK PDZ interactions (Bats et al., 2007; Sainlos et al., 2011; Schnell et al., 2002). Multiple reports indicate that PSD-95 is clustered in isolated PSDs (DeGiorgis et al., 2008; Swulius et al., 2010), and enriched in synaptic nanodomains in cultured neurons (MacGillavry et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2016), brain slice (Fukata et al., 2013), and in vivo (Broadhead et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2016). The PSD-95 density contrast in compared to out of its nanodomain is not as stark as for receptors (Nair et al., 2013), but there is a similar range of one to three ∼80 nm nanodomains per synapse. Considerable evidence supports that the PSD-95 pattern determines the AMPAR distribution (Chen et al., 2011; Ehrlich et al., 2007; El-Husseini et al., 2000; Elias et al., 2006; Nair et al., 2013; Schluter et al., 2006), including that EM tomography reveals consistent pairing of AMPARs with PSD-95 (Chen et al., 2008), and that receptors co-enrich in the PSD-95 nanodomain visualized with STORM (MacGillavry et al., 2013; Nair et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2016). Nevertheless, AMPARs may bind other proteins that may guide their position or facilitate clustering. Indeed, the AMPAR N-terminus protrudes 13 nm into the synaptic cleft (Greger et al., 2017), exposing it to a broad variety of partners. N-terminal interactions are critical for AMPAR anchoring (Diaz-Alonso et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2017).

Mechanisms producing nanoclustering of MAGUKs are unclear, though may involve their palmitoylation (Fukata et al., 2013) which is required for receptor binding (Jeyifous et al., 2016) and executed by activity-regulated palmitoyl transferases (Fukata et al., 2004; Fukata et al., 2013; Noritake et al., 2009). However, the overall PSD-95 pattern of a synapse likely involves extensive interactions as part of the high degree of PSD organization in the “vertical” dimension perpendicular to the membrane. Through C-terminal domains, PSD-95 links to PSD components such as GKAP and Shank that reside further from the membrane (Dani et al., 2010; Valtschanoff and Weinberg, 2001) creating a laminated structure (Burette et al., 2012; Harris and Weinberg, 2012) with interlinking proteins at each layer. These multiple interactions suggest that the MAGUK distribution may dictate patterning of other proteins aside from glutamate receptors. Indeed, Shank3, GKAP2, and even the “deepest” scaffold tested, Homer 1a, also are enriched within PSD-95 nanodomains. The variety of transmembrane proteins that bind PSD-95, including adhesion molecules and ion channels, suggests that this highly interlinked matrix establishes position of receptors along with many other synaptic elements.

Because NMDARs are thought to be among the first residents of synapses, an attractive possibility is that during synapse formation, an NMDAR bound with MAGUKs in a “supercomplex” (Frank and Grant, 2017) seeds formation of further structures. In EM tomography, NMDARs and AMPARs are segregated to separate zones of the synapse, suggesting functional differentiation of MAGUK nanodomains, and mechanisms that span multiple domains need to be engaged if the NMDA-MAGUK complex provides for a seed. While segregation of AMPA and NMDARs has not been reported using other methods, STORM immunocytochemistry suggests that GluN2B-containing NMDARs enrich more avidly within PSD-95 nanodomains than the overall NMDAR population (MacGillavry et al., 2013), potentially due to direct GluN2B C-terminal PDZ binding. Interestingly, the number of PSD-95 molecules per nanodomain and the number of such nanodomains per synapse each vary considerably among hippocampal cell types and even along the extent of the dendrites (Broadhead et al., 2016). Together, this suggests that scaffold nanodomains may serve as “building blocks” of synapses, but that the blocks are variable in size and molecular content, presumably contributing to functional diversity.

The use of single-particle tracking methods has made clear that AMPARs are typically highly mobile in the extrasynaptic membrane. Even many synaptically localized AMPARs are able to diffuse within the PSD, at least in cell culture and cultured brain slices, and the rate of exchange in and out of the PSD border is potentially critical for mechanisms establishing basal synaptic strength. By allowing escape and replenishment of recently activated receptors and thus desensitized receptors, mobility of synaptic receptors may regulate the time over which a synapse recovers from desensitization following action potential-mediated glutamate release (Choquet and Triller, 2013; Heine et al., 2008). However, many receptors remain nearly immobilized within the PSD for prolonged periods (Adesnik et al., 2005), diverging little from restricted zones (Ehlers et al., 2007; Kerr and Blanpied, 2012). Single-molecule tracking reveals that receptors between nanodomains are mobile, whereas receptors in the nanodomains are nearly immobilized (Nair et al., 2013). This immobilization is presumably due to binding to scaffold molecules in the nanodomain (Opazo et al., 2012), but other mechanisms may contribute as well. The PSD is extremely dense with protein, and modeling suggests that the even higher density within nanodomains likely provides obstacles to mobility of bulky receptors even not bound to scaffolds (Santamaria et al., 2010). Indeed, synaptic diffusion rates of both lipids (Renner et al., 2009) and transmembrane proteins (Li and Blanpied, 2016) are size-dependent, and even proteins without domains that bind PSD-95 diffuse more slowly within portions of the PSD where the scaffold is denser (Li and Blanpied, 2016). This effect, termed macromolecular crowding, may be particularly important in controlling receptor exit rate during episodes of plasticity (Li et al., 2016), and in concert with binding may contribute to the pattern of receptors.

Together, we have presynaptic and postsynaptic machines, functionally differentiated over small spatial dimensions of 80 nm or less, separated by a cleft with similarly striking organizational features (Figures 1, 2A–2C).

Trans-synaptic nanoalignment

Are release sites and receptors aligned in nanocolumns?

The results reviewed above indicate that the structure of each synaptic compartment is sub-organized in domains at the scale of tens of nanometers. Synaptic function is similarly organized in domains in the range of tens of nanometers, with the efficiency of receptor activation dropping with distance from an exocytotic event. Hence, the hypothesis has arisen that these subdomains are aligned with one another (Lisman and Raghavachari, 2006). A recent study found evidence in direct support of trans-synaptic alignment of release machinery with receptors (Tang et al., 2016). The key finding of this study was that newly identified nanoclusters of RIM were aligned with nanoclusters of PSD-95 as measured using 3D-STORM imaging (Figure 2D). The RIM cluster diameter was ∼80 nm, similar to the size of AMPAR nanoclusters, perhaps suggesting that there are mechanisms for matching pre- with postsynaptic cluster size. RIM nanoclusters aligned across the synaptic cleft with AMPAR nanoclusters both in cultured neurons and fixed brain. This physical alignment brings to mind a nanoscale column or “nanocolumn” spanning the two cells (Figure 2E). As discussed below, whether the nanocolumn comprises a discrete molecular structure or represents a transcellular functional organization remains to be determined. The potential relevance of these trans-cellularly aligned scaffolds was assessed by determining whether release of neurotransmitter preferentially occurs within these nanocolumns. Critically, the RIM localization density predicted the location of fusion events evoked by action potentials, consistent with the idea that transmission is biased to occur with highest probability within the nanocolumn.

The physiological and modeling results discussed above suggest this arrangement contributes to basal synaptic strength. Further, increasing or decreasing alignment may alter response amplitude, as could addition or dispersal of individual nanocolumns. This could potentially proceed without posttranslational modifications of receptors or involvement of trafficking to or from the plasma membrane, providing a notable complement to the well-studied forms of long-term potentiation and depression. The apparently wider area of the bouton from which spontaneous release occurs compared to release following action potentials (Tang et al., 2016) has a number of implications. These peripheral sites of release may activate fewer receptors, so it will be important to compare spontaneous and evoked response amplitudes at single, identified synapses. They may also activate functionally distinct subsets of receptors, supporting the notion that spontaneous and evoked neurotransmission may occur via separate domains (Kavalali, 2015; Melom et al., 2013; Sara et al., 2011).

These findings raise several important questions. First, a systematic analysis of presynaptic release machinery will be required to better define the molecular architecture of a fusion site at a nanoscale so that the alignment of these sites with postsynaptic receptors can be understood. This will be challenging, as many proteins are present in the synaptic vesicle fusion machinery (Boyken et al., 2013; Muller et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2014) and there was variability in clustering between RIM, Munc13 and Bassoon (Tang et al., 2016), three central release components. This contrasts with the ease of interpreting clusters of AMPARs, which per se represent the essential machinery for postsynaptic signal transduction. Second, it remains unclear to what extent the numbers of presynaptic release sites are in accordance with trans-synaptic units in the cleft and receptor clusters in the postsynaptic density. As described above, presynaptically, estimates of release site numbers range from 1 to ∼15 depending on the method employed (Imig et al., 2014; Maschi and Klyachko, 2017; Miki et al., 2016; Oertner et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2016). Postsynaptically, the view has emerged that an average hippocampal excitatory synapse contains ∼2–3 AMPAR clusters. This mismatch is not yet clarified, but could be accounted for by a model in which multiple vesicle fusion sites with variable release properties surround a cluster of RIMs, opposed to the postsynaptic AMPARs. Third, validation of trans-synaptic nano-alignment using other methods will be important. Localization microscopy has been central to the recent surge of observations regarding synaptic nanostructure discussed above, since it routinely achieves nominal resolution in the tens of nanometers (Liu et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the statistical methods to analyze molecule clustering are diverse, complex, and not yet standardized (Nicovich et al., 2017). Thus, validation through other methods offering similar or better resolution, such as correlated light and electron microscopy (Shu et al. 2011), will be critical.

Finally, a fourth key question is what mechanisms account for this trans-synaptic nano-assembly. Although our answers are speculative at this point, we will elaborate on several possibilities in the following section.

Candidate mechanisms of trans-synaptic alignment

Trans-synaptic adhesion

Direct trans-synaptic interactions provide a potential physical correlate of the column concept (Figure 3A). Candidate adhesive nanocolumn organizers can be expected to fulfill at least one of three properties: First, they should engage in interactions that bridge pre- and post-synaptic membranes. Second, an organizer of subsynaptic alignment should exhibit a patterned localization within the synaptic cleft resembling the intra-synaptic nanodomains. Third, altering their expression or disrupting their extracellular assembly should affect the column structure. Although no protein family fully fulfills these expectations, work from many laboratories has identified promising candidates.

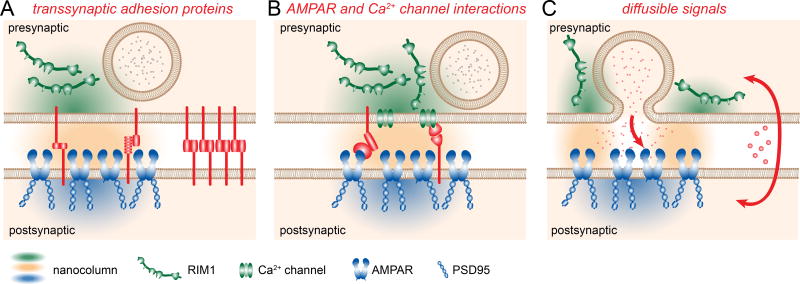

Figure 3. Alternative mechanisms of alignment.

Three possible mechanisms for trans-synaptic alignment into nanocolumns are direct interactions between trans-synaptic adhesion proteins (A), interactions of cleft proteins with presynaptic Ca2+ channels or postsynaptic receptors (B), or diffusible signals for antero- or retrograde signaling (C). Each group of mechanisms is discussed in the text, and they may account on their own or in any combination for the nanocolumn structure.

Of particular relevance for identifying trans-synaptic mechanisms underlying nanocolumn alignment are those adhesion molecules that exhibit a non-homogeneous sub-synaptic distribution. Information on this is limited due in part to the lack of reliable antibodies or other reagents to determine localization, but the first observations are already intriguing. Whereas neuroligin-1 appears distributed rather broadly over the PSD as determined by single particle tracking of exogenously expressed protein, the synaptogenic protein LRRTM2 is localized in compact and stable synaptic clusters (Chamma et al., 2016). The interaction of each of these proteins with presynaptic neurexins and postsynaptic PSD-95 (Mondin et al., 2011) suggests that either could provide a spatially instructive signal for organizing proteins in each cell. Another possibility is EphB2, the postsynaptic receptor of presynaptic membrane-anchored ephrins, which is also present enriched towards the center of the PSD (Perez de Arce et al., 2015). A further candidate molecular linkage from active zone to cleft is provided by Liprin-α, which binds to RIM (Schoch et al., 2002) as well as transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatases of the LAR family (Serra-Pages et al., 1998). LAR proteins interact with a variety of postsynaptic membrane proteins that control excitatory synapse development including NGL/LRRC (Netrin-G ligand/Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein), Slitrks (Slit- and Trk-like proteins), and SALM proteins (synaptic adhesion-like molecules) (Beaubien et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2016; Li et al., 2015; Woo et al., 2009; Yim et al., 2013) and thus may bridge the cleft. Nevertheless, the existence of a LAR-Liprin-RIM complex at the active zone remains tentative, and the subcellular distribution of the Liprin and LAR proteins and postsynaptic LAR partners are incompletely documented.

Because the functional domains within pre- and post-synaptic sites are much larger than individual molecules, assembly of these structures may be facilitated through more complex interactions within the cleft. The assembly of trans-synaptic nanocolumns could include the lateral oligomerization of cleft components (Dean et al., 2003; Fogel et al., 2011; Um et al., 2014), bridging molecules (Singh et al., 2016; Yuzaki, 2017), or be regulated by steric hindrance to block interactions, such as the ones shown for neuroligins (Gangwar et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Elegheert et al., 2017). In addition to these direct interactions, molecular crowding within the tightly packed environment of synaptic specializations needs to be considered as a factor in placing nanocolumns (Li et al., 2016). Further, while it is attractive to search for alignment-promoting components within the nanocolumn, trans-synaptic proteins occupying other zones of the cleft may still help establish alignment. For instance, a protein which marks the postsynaptic edge, such as SynCAM 1 (Perez de Arce et al., 2015) or the classical synaptic adhesion molecule N-cadherin that is initially expressed throughout the cleft but later forms discrete clusters including at the edge (Elste and Benson, 2006; Uchida et al., 1996; Yamagata et al., 1995) may participate in a form of “center-surround inhibition” by reserving some subregions for purposes other than alignment—perhaps even by sequestering factors that detract from alignment. Finally, many proteins in the cleft are targets of extracellular proteases that influence synapse function (Shinoe and Goda, 2015), suggesting a means of activity-dependent regulation over these various mechanisms.

Extracellular interactions with receptors or Ca2+ channels

Could postsynaptic receptors or Ca2+ channels themselves guide cleft or active zone organization (Figure 3B)? Several lines of evidence are consistent with this possibility. The extracellular domains of glutamate receptors can engage in interactions within the cleft, including with known adhesion molecules. Some of these interactions are on the postsynaptic membrane (i.e. in cis, rather than in trans across the cleft). Notably, GluN1 binds in cis to neuroligin-1 (Budreck et al., 2013), and also binds to the EphB2 receptor in an interaction stimulated by ephrinBs (Dalva et al., 2000; Grunwald et al., 2001). Similarly, GluA2 may modulate the synaptic stabilization effects of neuroligin (Ripley et al., 2011). Receptors are also directly involved in trans-synaptic interactions. In cerebellum, the unique postsynaptic receptor GluD2 interacts with presynaptic neurexin via hexamers of the C1q-family member cerebellin (Elegheert et al., 2016). Presynaptic neurexin-3 also modulates the recruitment of postsynaptic AMPARs during LTP (Aoto et al., 2013). This may involve the postsynaptic LRRTM family. Several lines of evidence support that LRRTM proteins recruit or maintain AMPARs at synapses. First, knock-down of LRRTM 1 and 2 decrease synaptic AMPAR currents (de Wit et al., 2009; Soler-Llavina et al., 2011). Second, LRRTMs are found in a physical complex with AMPARs (Schwenk et al., 2012). Third, LRRTM1, 2, and 4 promote the synaptic surface expression of GluA1-containing AMPARs, including after synaptic potentiation (de Wit et al., 2009; Siddiqui et al., 2013; Soler-Llavina et al., 2013). These findings along with its clustered subsynaptic distribution (Chamma et al., 2106) make LRRTMs attractive candidate molecules to organize nanocolumns. Another potentially important trans interaction with the AMPAR N-terminal domain involves the neuronal pentraxins (O’Brien et al., 1999). This small family includes two secreted proteins, but also one transmembrane protein called the neuronal pentraxin receptor (NPR) expressed in the presynaptic membrane. Postsynaptic expression of NPR is synaptogenic, and interestingly the effect is modulated by the competitive AMPAR antagonist NBQX (Lee et al., 2017). It has also been reported that N-cadherin binds GluA2 in both cis and trans (Saglietti et al., 2007), which in turn was hypothesized to modulate retrograde control over presynaptic function (Vitureira et al., 2011). Together, these diverse interactions with AMPARs suggest that the receptors themselves may be spatially instructive for positioning release sites, raising interesting questions about whether broad aspects of subsynaptic organization respond dynamically to receptor mobility and plasticity.

The possibility that presynaptic Ca2+ channels instruct postsynaptic organization is also intriguing, but unlike most receptors, presynaptic Ca2+ channels have only a small extracellular domain and thus are less likely to guide cleft interactions. Nevertheless, the GPI-linked extracellular protein α2δ, which associates with Ca2+ channels, may broaden these interactions. α2δ contributes to the presynaptic abundance and positioning of voltage gated Ca2+ channels (Hoppa et al., 2012) and to the size of Bassoon and RIM clusters (Schneider et al., 2015). This may be mediated by roles of α2δ as a subunit of Ca2+ channels or through its roles in synaptic morphogenesis that are independent of the α1-subunits (Kurshan et al., 2009). Potential trans-synaptic links are suggested by interactions of α2δ with the LRR domain of ELFN1 in the cleft of rod photoreceptor synapses (Wang et al., 2017). A recent study also observed loss of both Ca2+ channels and AMPARs/PSD-95 co-localization upon α2δ loss in auditory ribbon synapses, implicating a role in organizing this synapse (Fell et al., 2016). Intriguingly, the C. elegans α2δ protein participates in retrograde signaling via neurexin-neuroligin interactions (Tong et al., 2017). Overall, diverse protein interactions with glutamate receptors and Ca2+ channels in the synaptic cleft may cooperate to establish subsynaptic functional alignment along with or independent of trans-synaptic adhesion.

Secreted factors

In addition to cell-cell contact signals, secreted factors are candidates to modulate trans-synaptic alignment (Figure 3C). Among the retrograde synaptic signals that are secreted by postsynaptic neurons and that may support alignment are Wnt7a which promotes synaptic vesicle recycling (Ahmad-Annuar et al., 2006) and the growth factor BDNF which acts on presynaptic Trk receptors to potentiate transmission (Li et al., 1998). In addition, endocannabinoids act on the neurexin-neuroligin axis, though their interplay is complex. Here, the loss of β-neurexins in mice enhances tonic endocannabinoid signaling and decreases spontaneous release at excitatory synapses (Anderson et al., 2015) while loss of neuroligin-3 impairs tonic endocannabinoid signaling and increases release at inhibitory synapses (Földy et al., 2013). Interestingly, endocannabinoids also require RIM1α for their presynaptic role in regulating release (Chevaleyre et al., 2007), indicating a link of these secreted factors to the presynaptic RIM components of nanocolumns. A final speculative mechanism includes glutamate itself. AMPAR mobility is regulated by agonist (Borgdorff and Choquet, 2002; Petzoldt et al., 2014), potentially via desensitization-driven disassembly from TARPs (Constals et al., 2015; Tomita et al., 2004). Preferential loss of desensitized receptors could in some fashion enrich synaptic regions prone to higher glutamate concentrations with receptors.

Consideration of synapse development

Investigation of alignment mechanisms in established synapses must consider whether nano-alignment arises during or after synaptogenesis. One possibility is that instructive signals such as those potentially provided by trans-synaptic adhesion during synapse formation simultaneously establish a nanocolumn alignment. Alternatively, pre- and post-synaptic machines created during synaptogenesis may not initially be spatially related, and subsequent remodeling, perhaps by separate trans-synaptic complexes not involved in synapse formation or by secreted factors, could later establish the nanocolumns of a mature synapse. Such remodeling might occur in an activity-dependent manner, or could involve a probing of synaptic status by spontaneous vesicle release, in agreement with the physiological functions of miniature events (Kavalali, 2015).

Understanding the temporal steps of nanocolumn alignment is related to the question of directionality. One side may be spatially instructive, which is supported by the well documented examples of retrograde functional effects (Arons et al., 2012; Cheadle and Biederer, 2012; Futai et al., 2007; Peixoto et al., 2012; Regalado et al., 2006). Yet, like for synaptogenesis, determining the ‘prime mover’ may be difficult. It also needs to be considered that this tripartite machine develops an intrinsic alignment due to reciprocal, cooperative mechanisms between its elements.

Conclusions and Outlook

The observation of cleft-spanning, nanometer-scale alignment of synaptic functional domains has highlighted a design principle that could enable efficient transmission and provide for novel regulatory mechanisms of synaptic strength. It will be exciting to determine when this structure appears at developing synapses, and under what situations its presence matters the most. Is the nanocolumn a unifying feature of all excitatory synapses, or does it define the subset of hippocampal excitatory synapses in which it was first described? Do synapses using other neurotransmitters display a similar alignment? What are the mechanisms and regulation of alignment? Does cleft structure adapt to or instruct alignment of pre- and postsynaptic machines?

Taking a step back, much of what we know and what we have presented here is derived from just a few synapse types that have been heavily studied, often due to ease of experimental access or because they represent informative extremes. Analyses in the future will have to consider more systematically the diversity of synapse types and functions to determine if and how synapse classification can help clarify physiological and mechanistic rules. This will rely on current and future technical development. Current lists of synapse components are long, likely because they accumulate data from an enormously diverse population of synapses, and it may not be helpful to consider all the molecules to be in operation at all synapses at all times. Cell type-specific and proximity labeling strategies should help to determine molecular catalogs of different synapse types and guide the identification and quantification of synapse-specific alignment components. Similarly, the rules that govern synapse architecture are diverse to say the least. The super-resolution imaging methods required to survey defined synapse populations at near-molecular resolution are developing rapidly. Their use to examine subsynaptic alignment of functional domains offers the chance to learn how experience and pathology modify the synaptic nanostructure-function relationship.

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed equally to this manuscript. We thank members of the Kaeser, Biederer, and Blanpied labs, particularly Drs. Aihui Tang and Haiwen Chen, for fruitful discussions and valuable comments on the manuscript. This work has been supported by R01NS083898, R01MH113349, and R01NS103484 (PSK), R01DA018928 (TB), and by R01MH080046 and R01MH111527 (TAB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acuna C, Liu X, Gonzalez A, Südhof TC. RIM-BPs Mediate Tight Coupling of Action Potentials to Ca<sup>2+</sup>-Triggered Neurotransmitter Release. Neuron. 2015;87:1234–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adesnik H, Nicoll RA, England PM. Photoinactivation of Native AMPA Receptors Reveals Their Real-Time Trafficking. Neuron. 2005;48:977–985. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad-Annuar A, Ciani L, Simeonidis I, Herreros J, Fredj NB, Rosso SB, Hall A, Brickley S, Salinas PC. Signaling across the synapse: a role for Wnt and Dishevelled in presynaptic assembly and neurotransmitter release. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:127–139. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GR, Aoto J, Tabuchi K, Foldy C, Covy J, Yee AX, Wu D, Lee SJ, Chen L, Malenka RC, Sudhof TC. beta-Neurexins Control Neural Circuits by Regulating Synaptic Endocannabinoid Signaling. Cell. 2015;162:593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews-Zwilling YS, Kawabe H, Reim K, Varoqueaux F, Brose N. Binding to Rab3A-interacting molecule RIM regulates the presynaptic recruitment of Munc13-1 and ubMunc13-2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:19720–19731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoto J, Martinelli DC, Malenka RC, Tabuchi K, Sudhof TC. Presynaptic neurexin-3 alternative splicing trans-synaptically controls postsynaptic AMPA receptor trafficking. Cell. 2013;154:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arons MH, Thynne CJ, Grabrucker AM, Li D, Schoen M, Cheyne JE, Boeckers TM, Montgomery JM, Garner CC. Autism-associated mutations in ProSAP2/Shank3 impair synaptic transmission and neurexin-neuroligin-mediated transsynaptic signaling. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14966–14978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2215-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin I, Rosenmund C, Sudhof TC, Brose N. Munc13-1 is essential for fusion competence of glutamatergic synaptic vesicles. Nature. 1999;400:457–461. doi: 10.1038/22768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bats C, Groc L, Choquet D. The interaction between Stargazin and PSD-95 regulates AMPA receptor surface trafficking. Neuron. 2007;53:719–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaubien F, Raja R, Kennedy TE, Fournier AE, Cloutier JF. Slitrk1 is localized to excitatory synapses and promotes their development. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27343. doi: 10.1038/srep27343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz A, Thakur P, Junge HJ, Ashery U, Rhee JS, Scheuss V, Rosenmund C, Rettig J, Brose N. Functional interaction of the active zone proteins Munc13-1 and RIM1 in synaptic vesicle priming. Neuron. 2001;30:183–196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederer T, Sara Y, Mozhayeva M, Atasoy D, Liu X, Kavalali ET, Südhof TC. SynCAM, a synaptic adhesion molecule that drives synapse assembly. Science. 2002;297:1525–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1072356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom FE, Aghajanian GK. Cytochemistry of synapses: selective staining for electron microscopy. Science. 1966;154:1575–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3756.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgdorff AJ, Choquet D. Regulation of AMPA receptor lateral movements. Nature. 2002;417:649–653. doi: 10.1038/nature00780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JG, Sakmann B. Calcium influx and transmitter release in a fast CNS synapse. Nature. 1996;383:431–434. doi: 10.1038/383431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyken J, Grønborg M, Riedel D, Urlaub H, Jahn R, Chua JJ. Molecular Profiling of Synaptic Vesicle Docking Sites Reveals Novel Proteins but Few Differences between Glutamatergic and GABAergic Synapses. Neuron. 2013;78:285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead MJ, Horrocks MH, Zhu F, Muresan L, Benavides-Piccione R, DeFelipe J, Fricker D, Kopanitsa MV, Duncan RR, Klenerman D, Komiyama NH, Lee SF, Grant SG. PSD95 nanoclusters are postsynaptic building blocks in hippocampus circuits. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24626. doi: 10.1038/srep24626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucurenciu I, Kulik A, Schwaller B, Frotscher M, Jonas P. Nanodomain coupling between Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ sensors promotes fast and efficient transmitter release at a cortical GABAergic synapse. Neuron. 2008;57:536–545. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budreck EC, Kwon OB, Jung JH, Baudouin S, Thommen A, Kim HS, Fukazawa Y, Harada H, Tabuchi K, Shigemoto R, Scheiffele P, Kim JH. Neuroligin-1 controls synaptic abundance of NMDA-type glutamate receptors through extracellular coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:725–730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214718110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burette AC, Lesperance T, Crum J, Martone M, Volkmann N, Ellisman MH, Weinberg RJ. Electron tomographic analysis of synaptic ultrastructure. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:2697–2711. doi: 10.1002/cne.23067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger PM, Mehl E, Cameron PL, Maycox PR, Baumert M, Lottspeich F, De Camilli P, Jahn R. Synaptic vesicles immunoisolated from rat cerebral cortex contain high levels of glutamate. Neuron. 1989;3:715–720. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calakos N, Schoch S, Sudhof TC, Malenka RC. Multiple roles for the active zone protein RIM1alpha in late stages of neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 2004;42:889–896. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamma I, Letellier M, Butler C, Tessier B, Lim KH, Gauthereau I, Choquet D, Sibarita JB, Park S, Sainlos M, Thoumine O. Mapping the dynamics and nanoscale organization of synaptic adhesion proteins using monomeric streptavidin. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10773. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda S, Hale WD, Zhang B, Wernig M, Sudhof TC. Unique versus Redundant Functions of Neuroligin Genes in Shaping Excitatory and Inhibitory Synapse Properties. J Neurosci. 2017;37:6816–6836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0125-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle L, Biederer T. The novel synaptogenic protein Farp1 links postsynaptic cytoskeletal dynamics and transsynaptic organization. J Cell Biol. 2012;199:985–1001. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201205041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Billings SE, Nishimune H. Calcium channels link the muscle-derived synapse organizer laminin beta2 to Bassoon and CAST/Erc2 to organize presynaptic active zones. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for NeuroScience. 2011;31:512–525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3771-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LY, Jiang M, Zhang B, Gokce O, Sudhof TC. Conditional Deletion of All Neurexins Defines Diversity of Essential Synaptic Organizer Functions for Neurexins. Neuron. 2017;94:611–625. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.011. e614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Nelson CD, Li X, Winters CA, Azzam R, Sousa AA, Leapman RD, Gainer H, Sheng M, Reese TS. PSD-95 Is Required to Sustain the Molecular Organization of the Postsynaptic Density. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6329–6338. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5968-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Winters C, Azzam R, Li X, Galbraith JA, Leapman RD, Reese TS. Organization of the core structure of the postsynaptic density. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4453–4458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800897105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Heifets BD, Kaeser PS, Sudhof TC, Castillo PE. Endocannabinoid-mediated long-term plasticity requires cAMP/PKA signaling and RIM1alpha. Neuron. 2007;54:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chih B, Engelman H, Scheiffele P. Control of excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation by neuroligins. Science. 2005;307:1324–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.1107470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Nam J, Whitcomb DJ, Song YS, Kim D, Jeon S, Um JW, Lee SG, Woo J, Kwon SK, Li Y, Mah W, Kim HM, Ko J, Cho K, Kim E. SALM5 trans-synaptically interacts with LAR-RPTPs in a splicing-dependent manner to regulate synapse development. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26676. doi: 10.1038/srep26676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet D, Triller A. The dynamic synapse. Neuron. 2013;80:691–703. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Jahr CE. Multivesicular release at Schaffer collateral-CA1 hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26:210–216. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4307-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubykin AA, Atasoy D, Etherton MR, Brose N, Kavalali ET, Gibson JR, Südhof TC. Activity-dependent validation of excitatory versus inhibitory synapses by neuroligin-1 versus neuroligin-2. Neuron. 2007;54:919–931. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constals A, Penn AC, Compans B, Toulme E, Phillipat A, Marais S, Retailleau N, Hafner AS, Coussen F, Hosy E, Choquet D. Glutamate-induced AMPA receptor desensitization increases their mobility and modulates short-term plasticity through unbinding from Stargazin. Neuron. 2015;85:787–803. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couteaux R, Pecot-Dechavassine M. [Synaptic vesicles and pouches at the level of “active zones” of the neuromuscular junction] C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci D. 1970;271:2346–2349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalva MB, Takasu MA, Lin MZ, Shamah SM, Hu L, Gale NW, Greenberg ME. EphB receptors interact with NMDA receptors and regulate excitatory synapse formation. Cell. 2000;103:945–956. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani A, Huang B, Bergan J, Dulac C, Zhuang X. Superresolution imaging of chemical synapses in the brain. Neuron. 2010;68:843–856. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydova D, Marini C, King C, Klueva J, Bischof F, Romorini S, Montenegro-Venegas C, Heine M, Schneider R, Schroder MS, Altrock WD, Henneberger C, Rusakov DA, Gundelfinger ED, Fejtova A. Bassoon specifically controls presynaptic P/Q-type Ca(2+) channels via RIM-binding protein. Neuron. 2014;82:181–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit J, Ghosh A. Specification of synaptic connectivity by cell surface interactions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:22–35. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2015.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit J, Sylwestrak E, O’Sullivan ML, Otto S, Tiglio K, Savas JN, Yates JR, 3rd, Comoletti D, Taylor P, Ghosh A. LRRTM2 interacts with Neurexin1 and regulates excitatory synapse formation. Neuron. 2009;64:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean C, Scholl FG, Choih J, DeMaria S, Berger J, Isacoff E, Scheiffele P. Neurexin mediates the assembly of presynaptic terminals. Nature NeuroScience. 2003;6:708–716. doi: 10.1038/nn1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGiorgis J, Galbraith J, Dosemeci A, Chen X, Reese T. Distribution of the scaffolding proteins PSD-95, PSD-93, and SAP97 in isolated PSDs. Brain Cell Biology. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11068-007-9017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Kaeser PS, Xu W, Sudhof TC. RIM Proteins Activate Vesicle Priming by Reversing Autoinhibitory Homodimerization of Munc13. Neuron. 2011;69:317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Alonso J, Sun YJ, Granger AJ, Levy JM, Blankenship SM, Nicoll RA. Subunit-specific role for the amino-terminal domain of AMPA receptors in synaptic targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:7136–7141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707472114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudanova I, Tabuchi K, Rohlmann A, Südhof TC, Missler M. Deletion of alpha-neurexins does not cause a major impairment of axonal pathfinding or synapse formation. J Comp Neurol. 2007;502:261–274. doi: 10.1002/cne.21305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermann E, Bucurenciu I, Goswami SP, Jonas P. Nanodomain coupling between Ca2+ channels and sensors of exocytosis at fast mammalian synapses. Nature Reviews NeuroScience. 2011;13:7–21. doi: 10.1038/nrn3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers MD, Heine M, Groc L, Lee MC, Choquet D. Diffusional trapping of GluR1 AMPA receptors by input-specific synaptic activity. Neuron. 2007;54:447–460. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Klein M, Rumpel S, Malinow R. PSD-95 is required for activity-driven synapse stabilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4176–4181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609307104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Husseini AE, Schnell E, Chetkovich DM, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. PSD-95 involvement in maturation of excitatory synapses. Science. 2000;290:1364–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elegheert J, Cvetkovska V, Clayton AJ, Heroven C, Vennekens KM, Smukowski SN, Regan MC, Jia W, Smith AC, Furukawa H, Savas JN, de Wit J, Begbie J, Craig AM, Aricescu AR. Structural Mechanism for Modulation of Synaptic Neuroligin-Neurexin Signaling by MDGA Proteins. Neuron. 2017;95:896–913. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.040. e810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elegheert J, Kakegawa W, Clay JE, Shanks NF, Behiels E, Matsuda K, Kohda K, Miura E, Rossmann M, Mitakidis N, Motohashi J, Chang VT, Siebold C, Greger IH, Nakagawa T, Yuzaki M, Aricescu AR. Structural basis for integration of GluD receptors within synaptic organizer complexes. Science. 2016;353:295–299. doi: 10.1126/science.aae0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias GM, Funke L, Stein V, Grant SG, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Synapse-specific and developmentally regulated targeting of AMPA receptors by a family of MAGUK scaffolding proteins. Neuron. 2006;52:307–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elste AM, Benson DL. Structural basis for developmentally regulated changes in cadherin function at synapses. J Comp Neurol. 2006;495:324–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.20876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]